FAILED STATE?

B.A.(Architecture), Hons. National University of Singapore, 2014

Thesis Report submitted to the Department of Architecture, National University of Singapore on May 5, 2014 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture.

Supervisor: Erik G. L’Heureux

Title: Assistant Professor

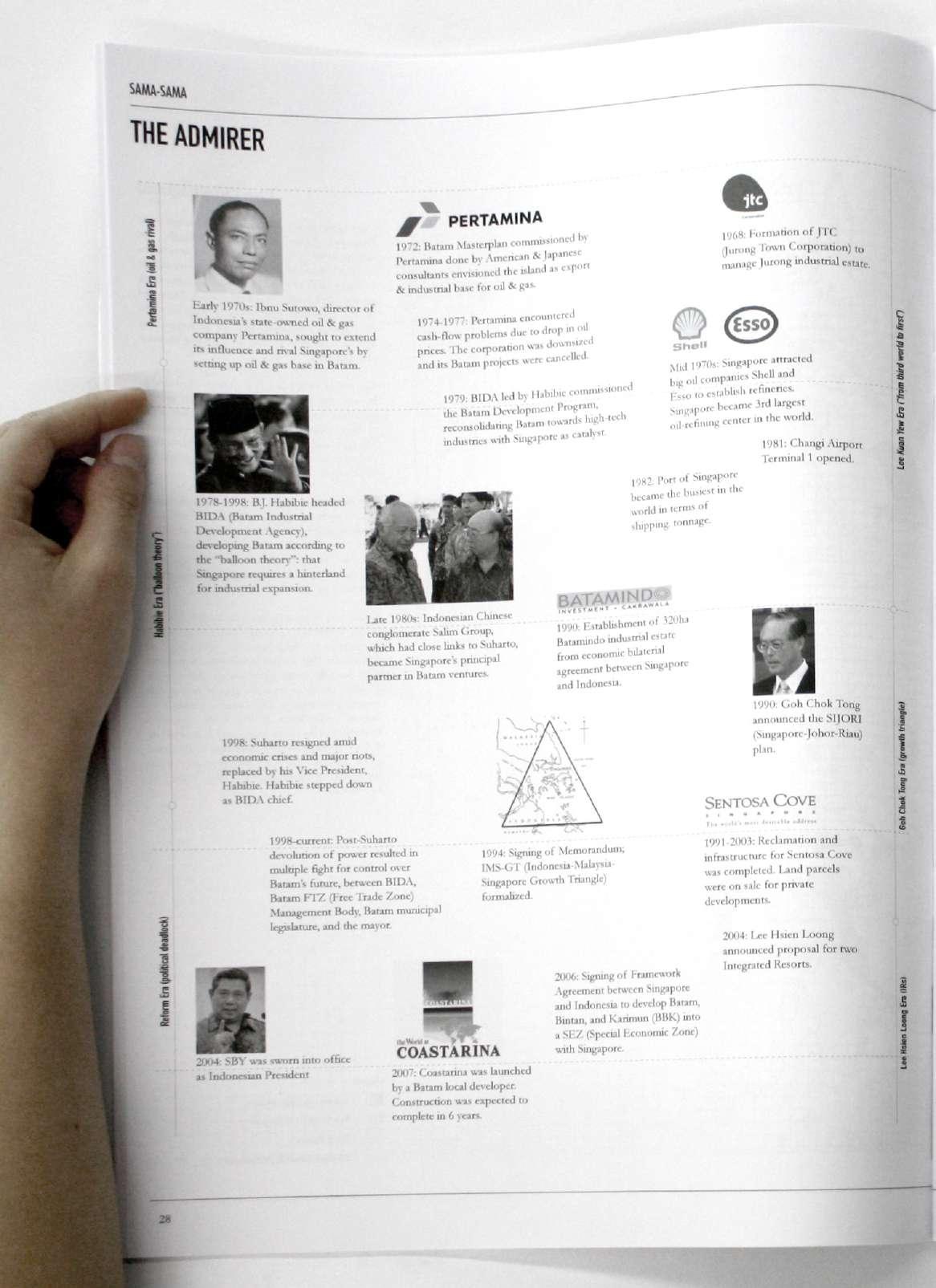

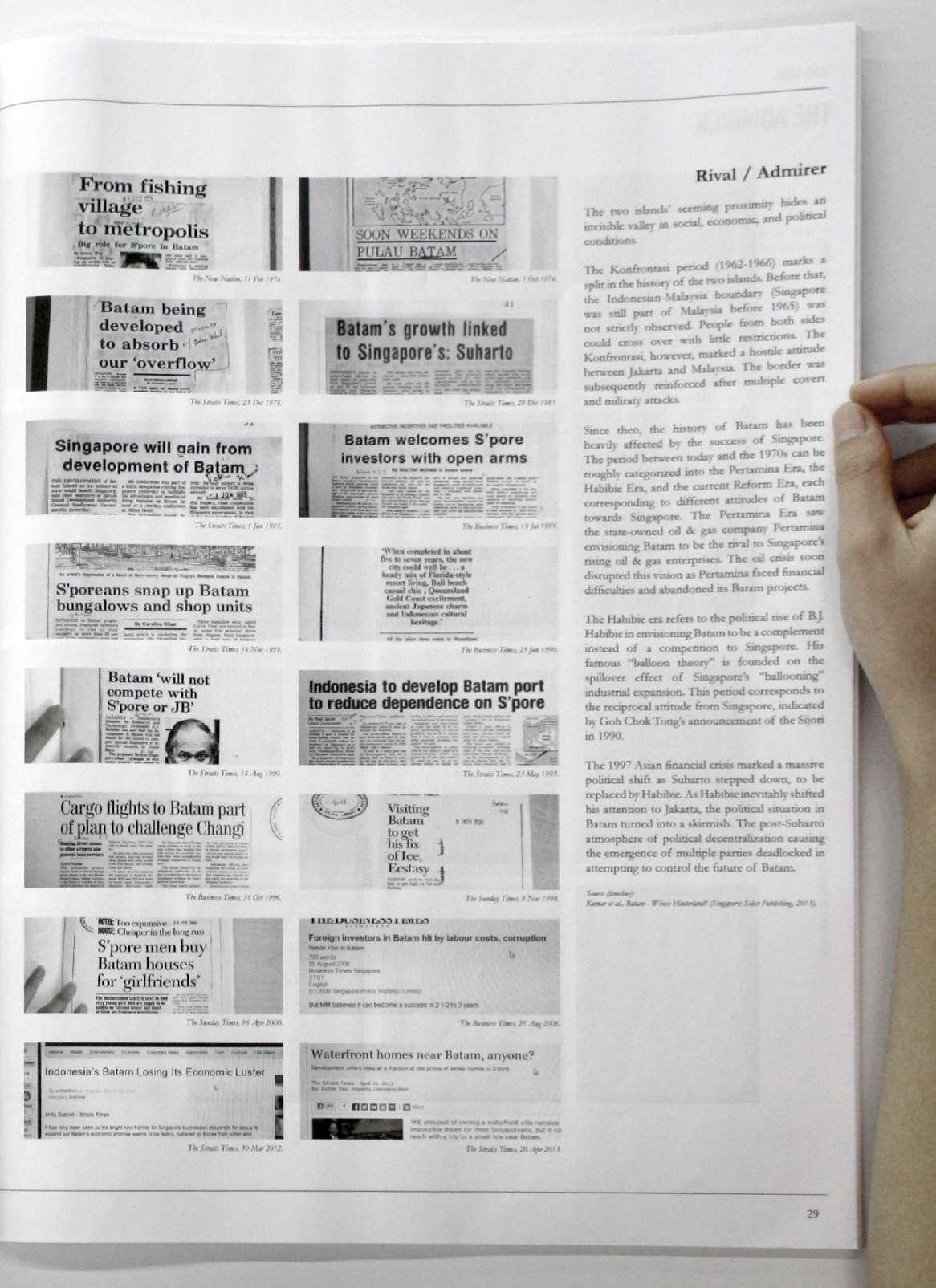

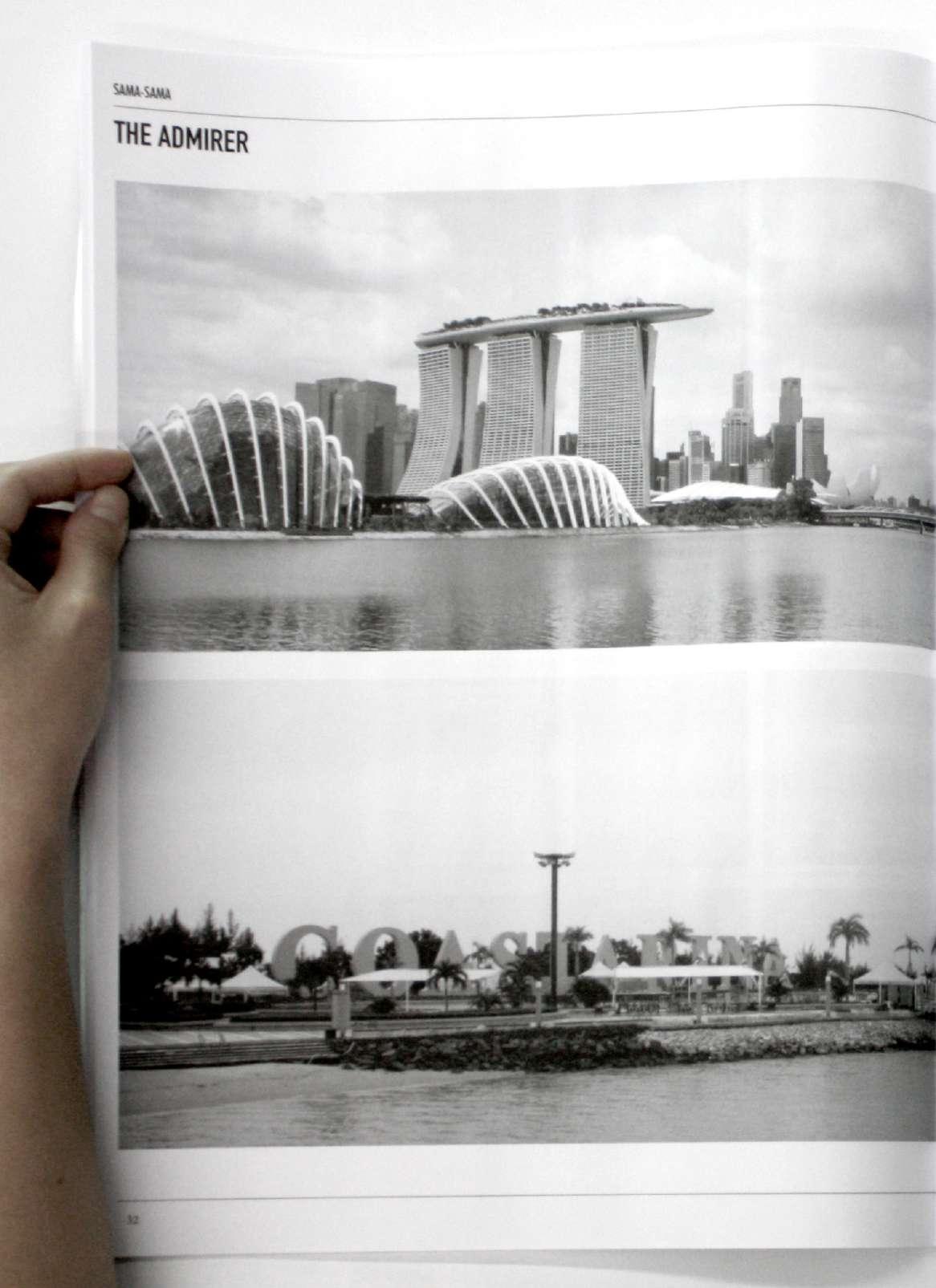

The relationship between Singapore and Batam is a complex mix of admiration and rivalry. Since the 70s, Batam has oscillated between trying to rival Singapore and feeding off Singapore’s success. In its admiration for Singapore, Batam samples many models that Singapore itself samples from around the world. One of these is the terraforming of coasts.

The model has its roots in 1950s Florida, where the suburbs were married with the romance of Venice. The coast is duplicated to increase real-estate values. Fingers of roads and culs-de-sac were tesselated with fingers of water canals. At the turn of the century, the model got a GPS update. Land can now be created according to precise symbolic forms. This culminated in Dubai’s the Palm (2001) and the World (2003).

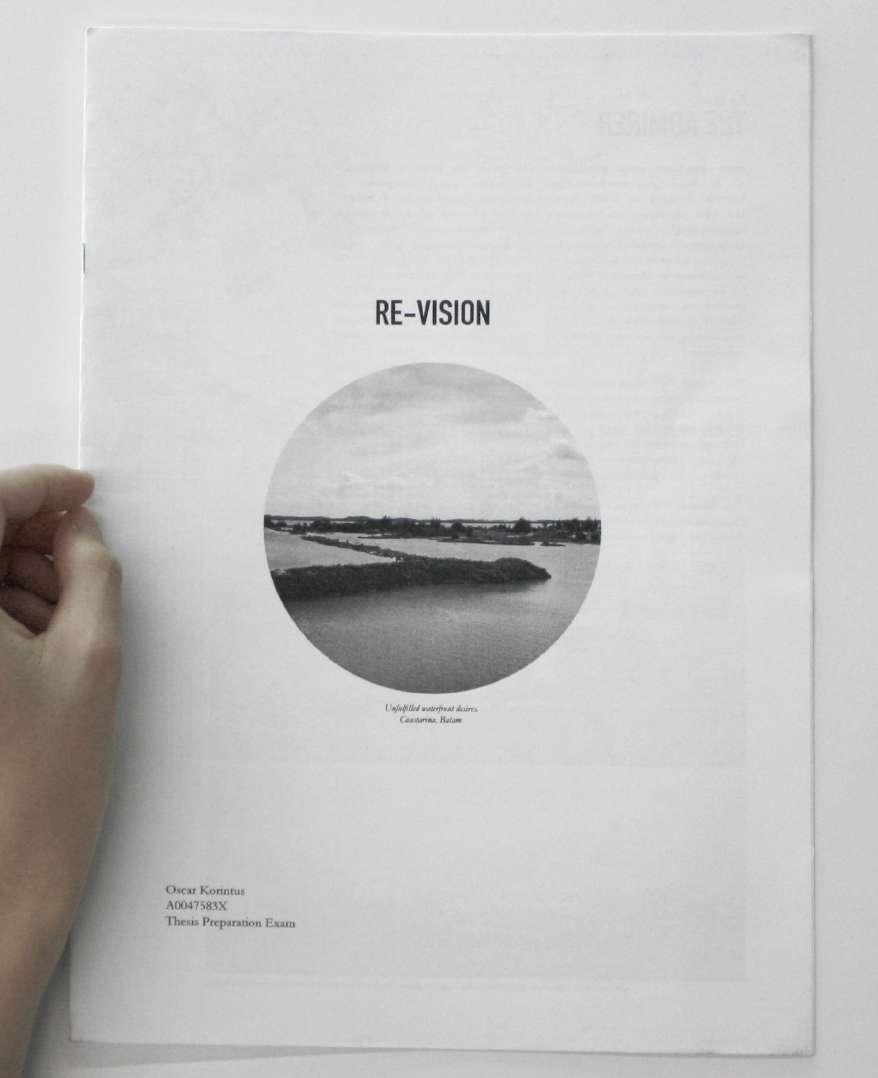

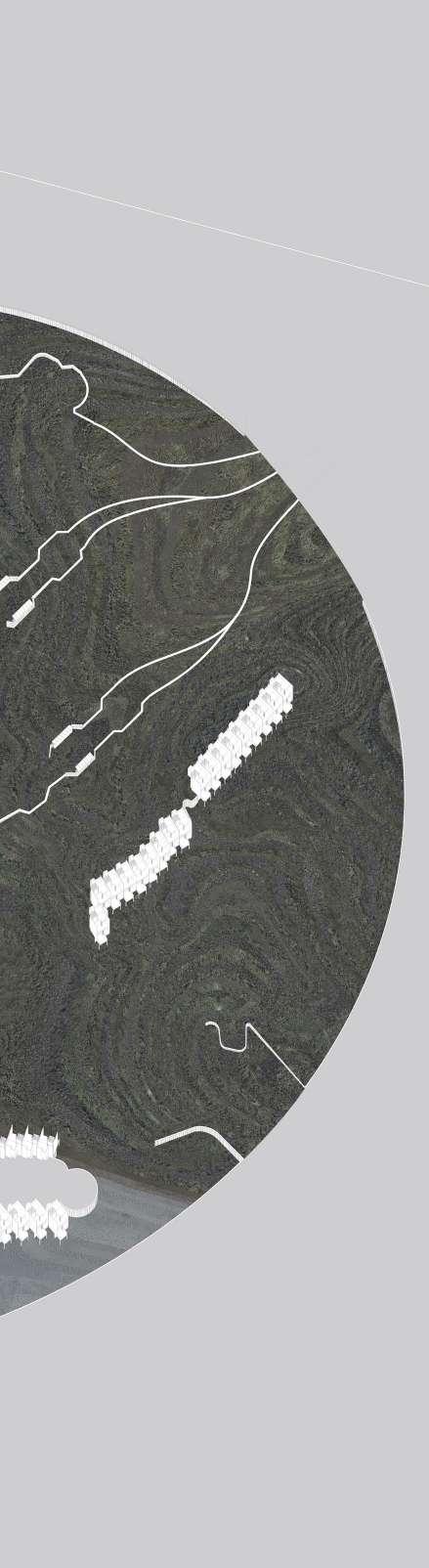

Spurred by the euphoria of such forms, Coastarina in Batam was conceived in 2005. Here, land was excessively created regardless of the vast amount of existing land in the southern region of Batam. Nevertheless, it was consumed by the cycles of speculations and recessions. In the midst of the 2008 financial crisis, reclamation stalled. What remains today is a vision unfulfilled.

Against Architecture’s primary domain of success and development, this thesis aims to question: How can Architecture positively intervene where normative development has failed?

The Ruin, on the other hand, frames and presents decay as a symbol of past glory. Thus when John Soane completed the Bank of England, he imagined it as a Ruin and hung the painting in the atrium. This re-presentation of decay parallels the current discourse of landscape urbanism: the found landscape — the abandoned railway track, the closed landfill — is Architecturalized into a public amenity.

Therefore, to dream of an alternative future, Batam has to realize that its failures are its strengths. Architecture enables it to re-present these found landscapes as an asset: a public amenity born out of its history of ambitions and endeavours.

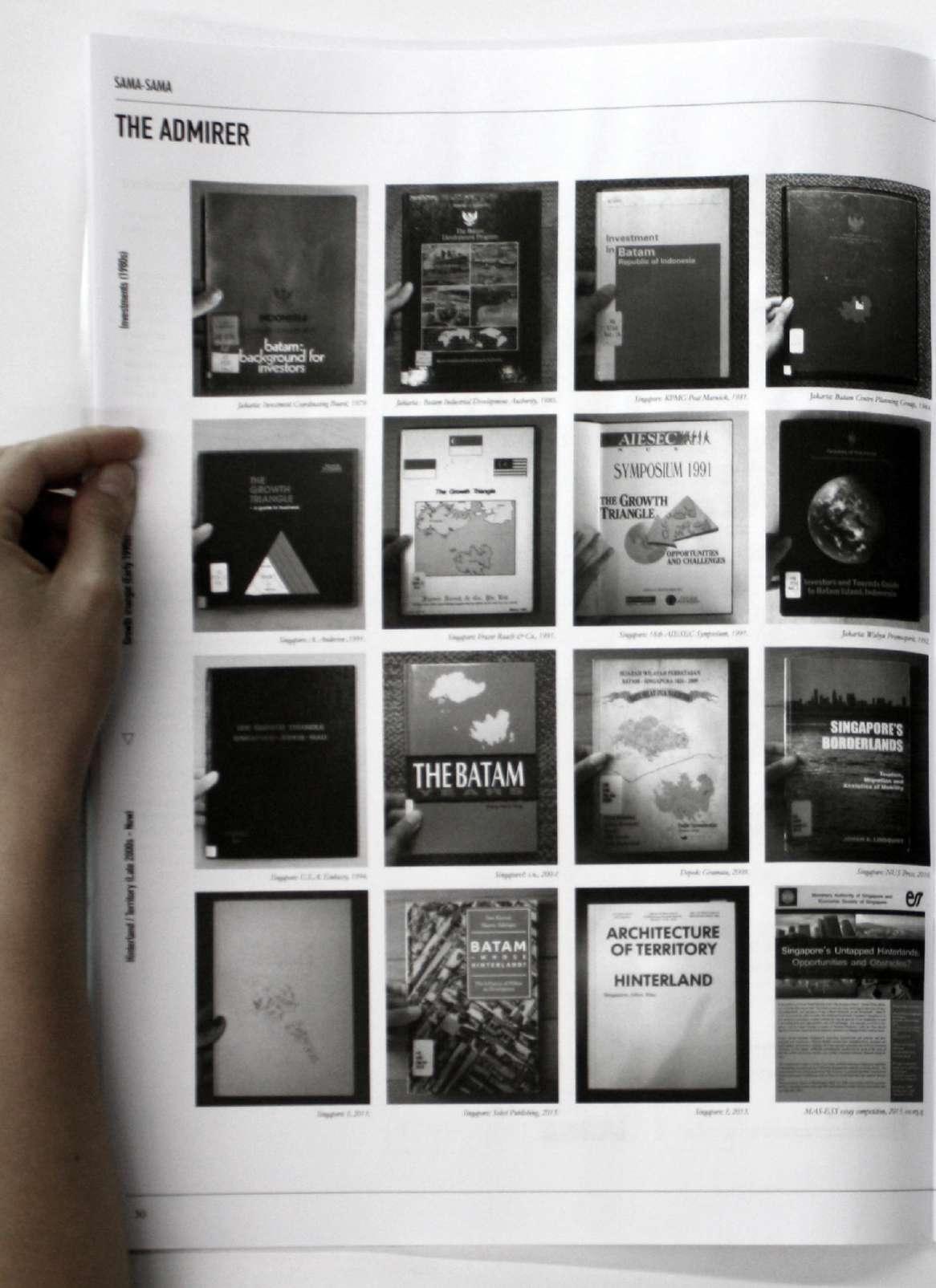

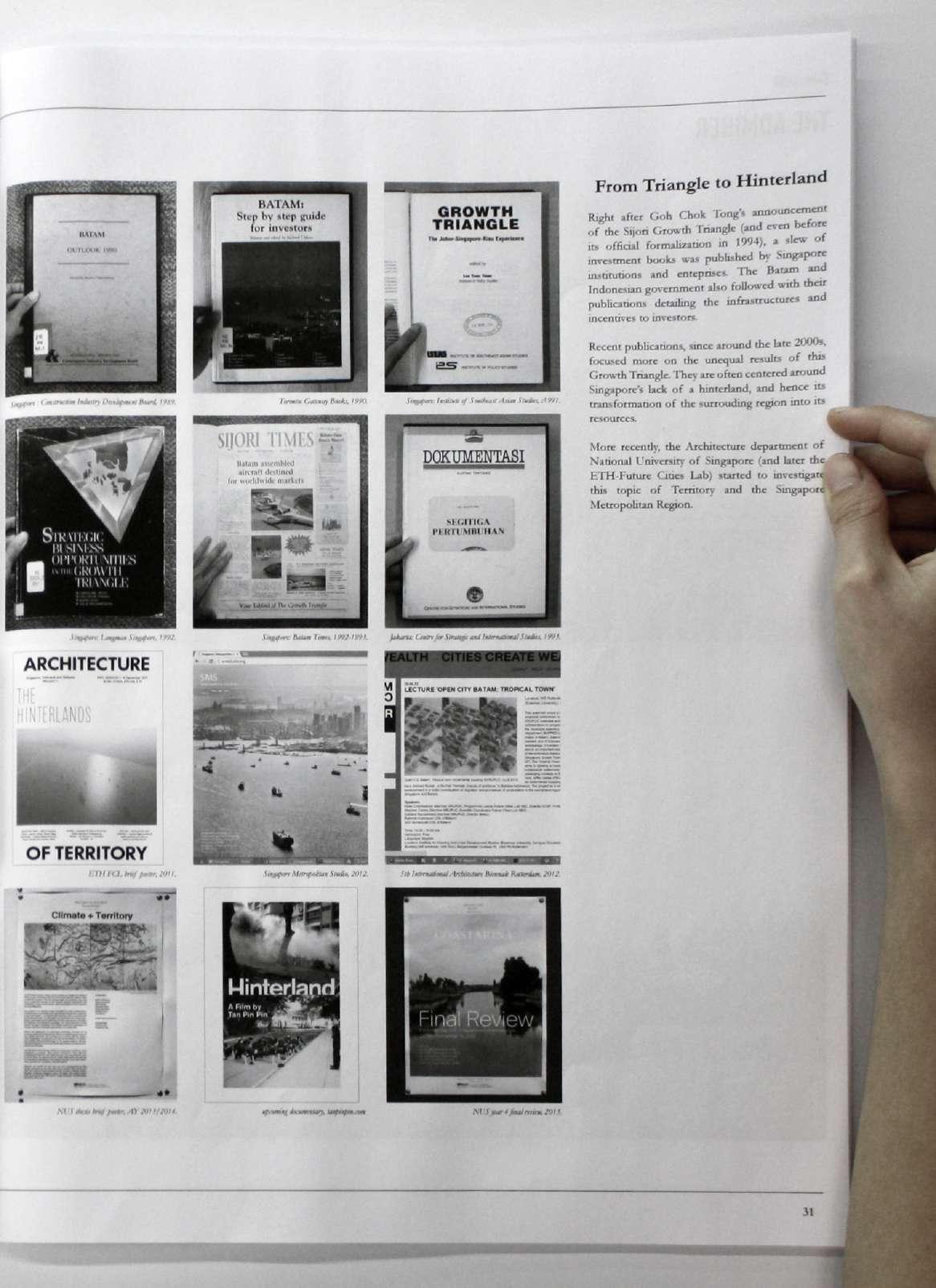

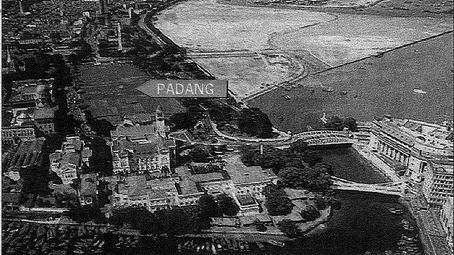

Since Goh Chok Tong’s introduction of the Sijori (Singapore-JohorRiau) Growth Triangle, the development of Batam has been answering the economic demands or receiving spill-over effects of Singapore’s growth. The island has since been reconfigured as a resource to Singapore. Attracted by the economic opportunities, large amount of migrants from other parts of Indonesia has arrived in the area, causing an explosive increase in population.

The vision of a borderless Growth Triangle is however far from reality. The flows of goods, resources, and people do not follow ideal paths of open exchanges between the two countries. The rapid transformation has also caused massive environmental impacts, which have been mostly hidden from Singapore.

The two islands are in fact only approximately 20km away from each other. The most convenient mode of transport between the two islands is ferry. Numerous routes link them from multiple harbours. Between them is, however, the busy Singapore Strait, the shipping route equivalent of a highway.

Batam had been envisioned under B.J. Habibie in the 1990s as Indonesia’s face-to-face proxy competitor to Singapore. The downfall of Suharto in 1998 caused a subsequent political shift towards more autonomous governance, releasing the island from the grip of Indonesia’s central government. The current situation is one of ambivalence: is Batam the industrial hinterland to the urban Singapore? Is it acting as a third-world productive landscape to the first-world city-state? Or is it a fantasy getaway from the rigidity of Singapore? The “free island” to the “fine city”?

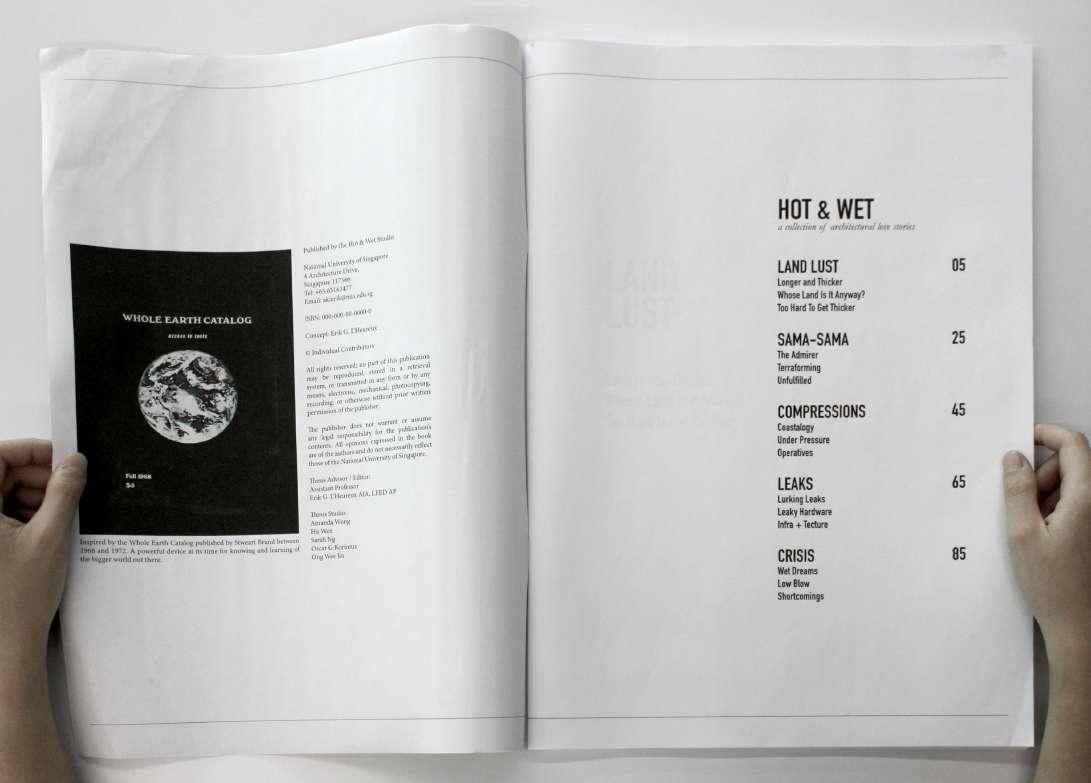

The following are excerpts from a chapter of the publication Hot & Wet: A Collection of Architectural Love Stories.

The publication is a catalogue of research done by the thesis group, guided by the need to look at the big picture. To truly understand Singapore is to look at it as the center of a metropolitan region, which includes Johor, Batam, and the Riau islands. The catalogue consists of five issues told as five stories dealing with the coasts in the Singapore Metropolitan Region, where the climate is hot & wet.

The first chapter is about Singapore’s lust for land, and the hard realities when it can no longer thicken itself. The second chapter is about Batam’s love affair with Singapore, and its unfulfilled waterfront desires. The third chapter tells Johor’s attempt to be Singapore’s extension, as it compresses its coasts into binaries of land and water. The fourth chapter looks at how Singapore leaks, and the infrastructure of these leakages. And the last chapter concludes with the hotter & wetter reality of the climate crisis, specifically Johor’s defensive strategies against flooding.

The five themes are ultimately linked to each other. Keeping with the spirit of looking at the big picture, works by others looking at similar topics are briefly reviewed, interspersed between the chapters.

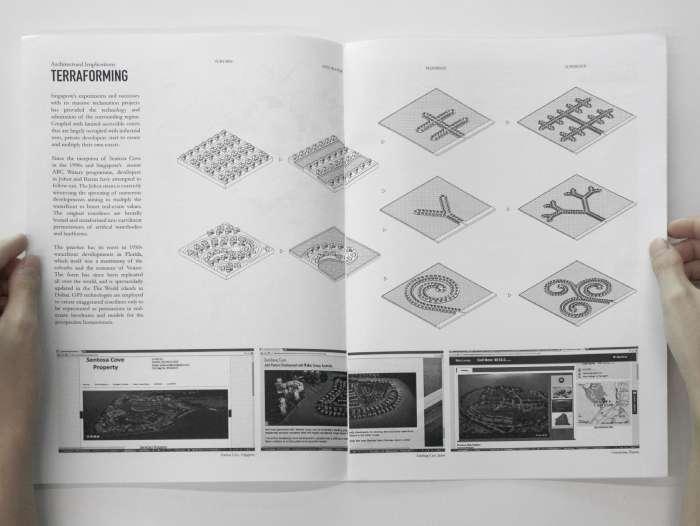

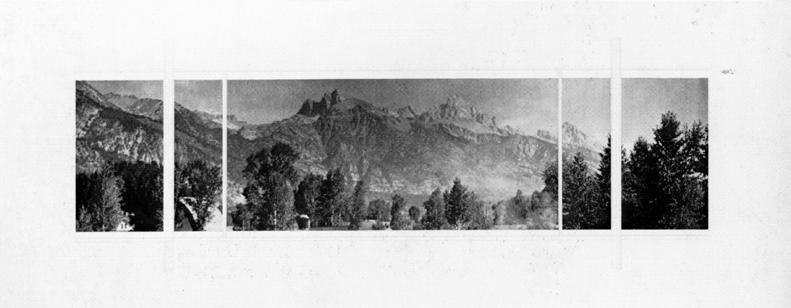

Singapore’s experiments and successes with its massive reclamation projects has provided the technology and admiration of the surrounding region. Coupled with limited accessible coasts that are largely occupied with industrial uses, private developers start to create and multiply their own coasts.

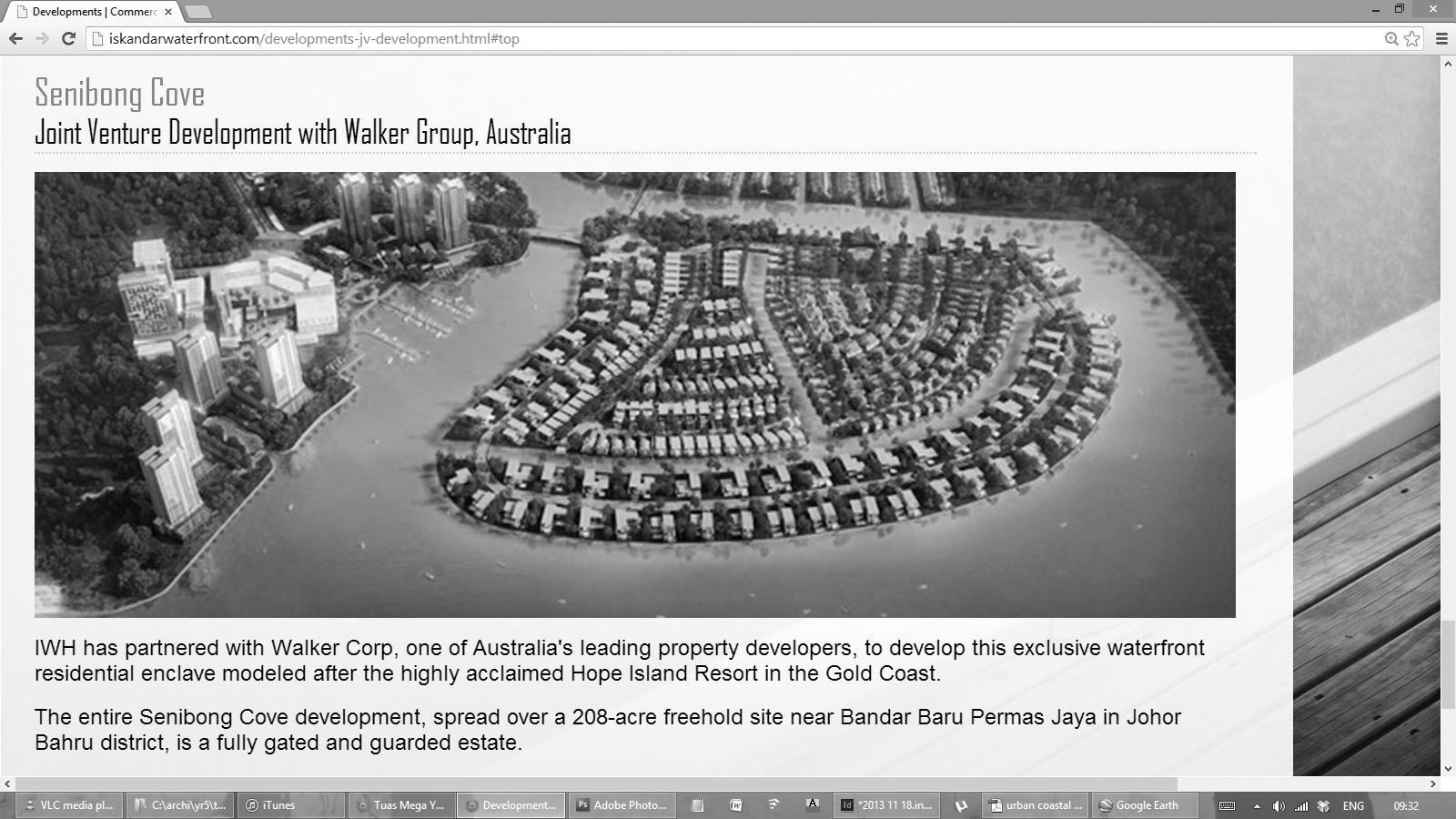

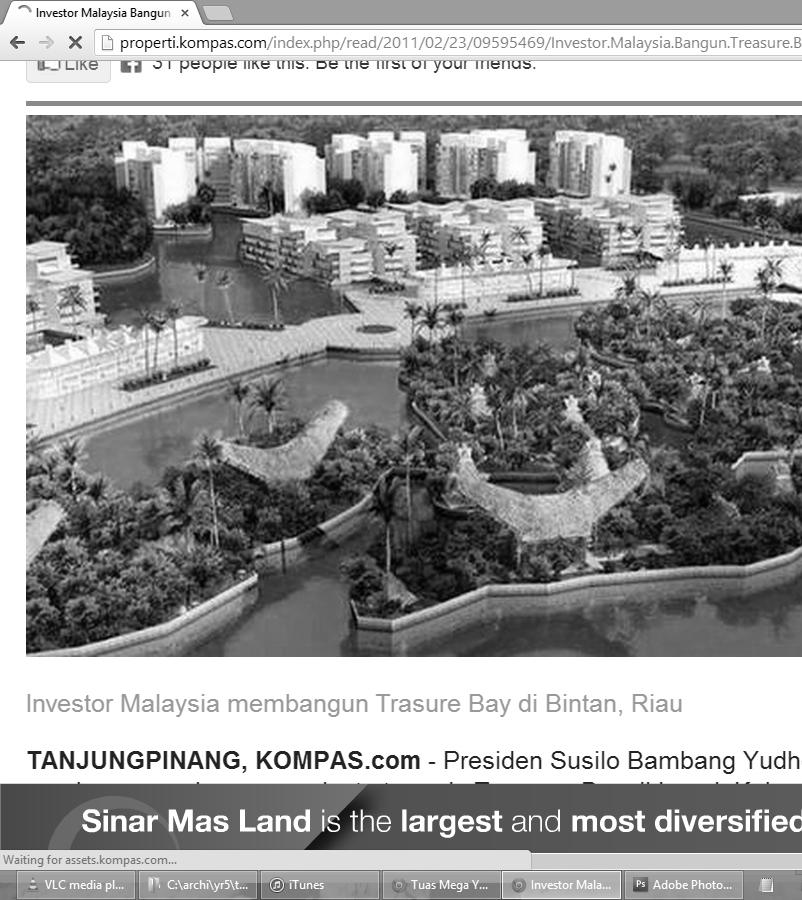

Since the inception of Sentosa Cove in the 1990s, and Singapore’s recent transformations of its concrete canals into picturesque “natural” waterways through the ABC Waters programme, developers in Johor and Batam have attempted to follow suit. The Johor straits is currently witnessing the sprouting of numerous developments aiming to multiply the waterfront to boost real-estate values. The original coastlines are brutally buried and terraformed into curvilinear permutations of artifical waterbodies and landforms.

This terraforming process usually starts with the digging of underwater trenches with barge dredgers, physically drawing the boundaries of the new land. A bund wall is then erected on these trenches by dumping sand with hopper barges and protected with breakwater layers to prevent the wall from being eroded. A temporary lagoon is created within the bund walls.

The thin walls are then thickened by dredging the underwater soil around the area and dumping them into the lagoon. Cutting suction dredgers blend any non-living or living things and suck them up from the surrounding sea beds. The sludge is then pumped and transferred through pipes and hoses, ending in a nozzle that sprays the slurry into the lagoon. After the lagoon has been filled up, the new land takes form.

The practice has its roots in 1950s waterfront developments in Florida, which itself was a matrimony of the suburbs and the romance of Venice. The form has since been replicated all over the world, and is spectacularly updated in the The World islands in Dubai. GPS technologies are employed to create exaggerated coastlines only to be represented as persuasions in real-estate brochures and models for the prospective homeowners.

With the demise of the natural coastlines and the unfortunate emergence of the terraformed coasts, perhaps the question should move away from what is lost to what can be done now?

The architectural from 1950s suburbs waterfront increasing The operation packing waterfront curvilinear, suburbs, out into Pushing multiplication, of the on both alternate the canals.

The tree the “branch” length area. The integrated

The spiral method. upon itself, the form the roads: water and more can organic

Venetian Islands, Florida

Treasure Island, Florida

Since 1990s, of its waterways developers follow the sprouting to multiply values. and terraformed of artifical The practice developments matrimony Venice. over the The World are employed only estate homeowners. With the unfortunate coasts, from

This the digging dredgers, the new A bund dumping with breakwater being within The thin the underwater them blend them sludge pipes the slurry After takes the water In Batam, speculations terraformed take jutting restaurants, Source (reclamation Chia et al. Living Aquatic

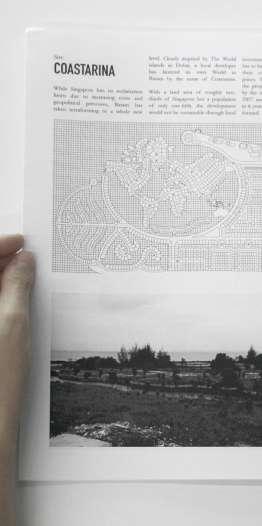

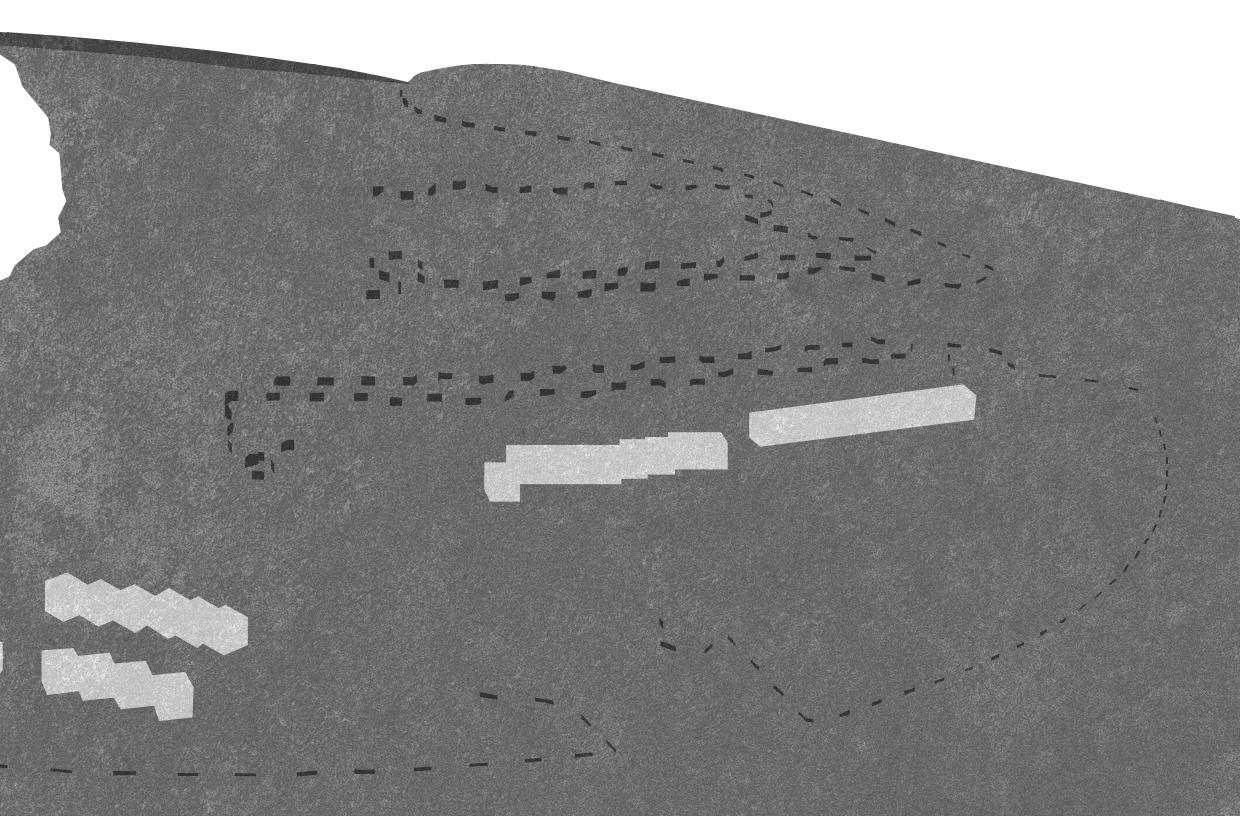

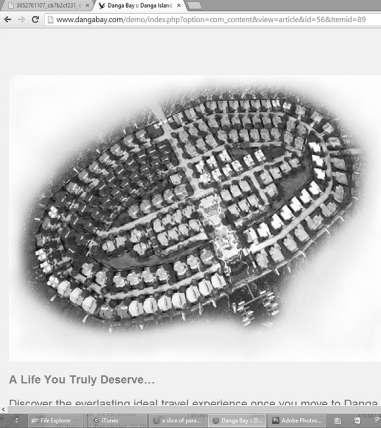

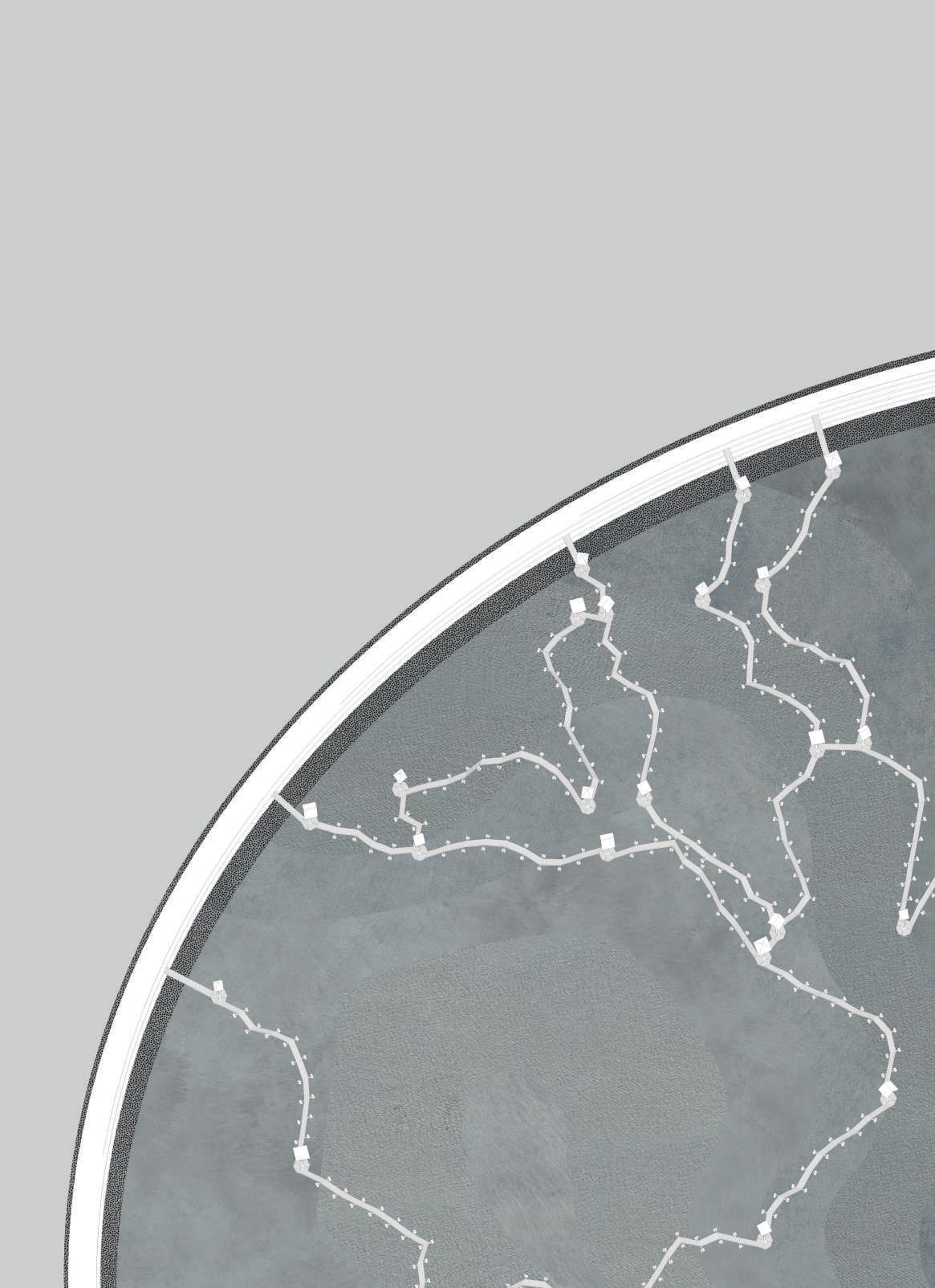

Since its launch in 2007, Coastarina has experienced the usual boom and bust common to Batam developments. As the private developer is initially confident (and would very much like to portray that confidence) in projected demands, the masterplan reveals an almost excessive and vulgar amount of symbolism. The World and Palm Jumeirah from Dubai is unashamedly transplanted with minor changes onto Batam.

Perhaps after a sobering reality check, the Palm is dropped, replaced with a more conventional land-based residential zone. The development then stalled for a few years, pressuring the developers to simplify the World into more efficient forms of waterfront multiplication.

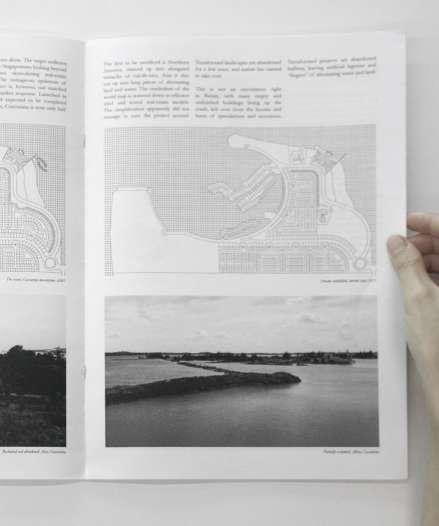

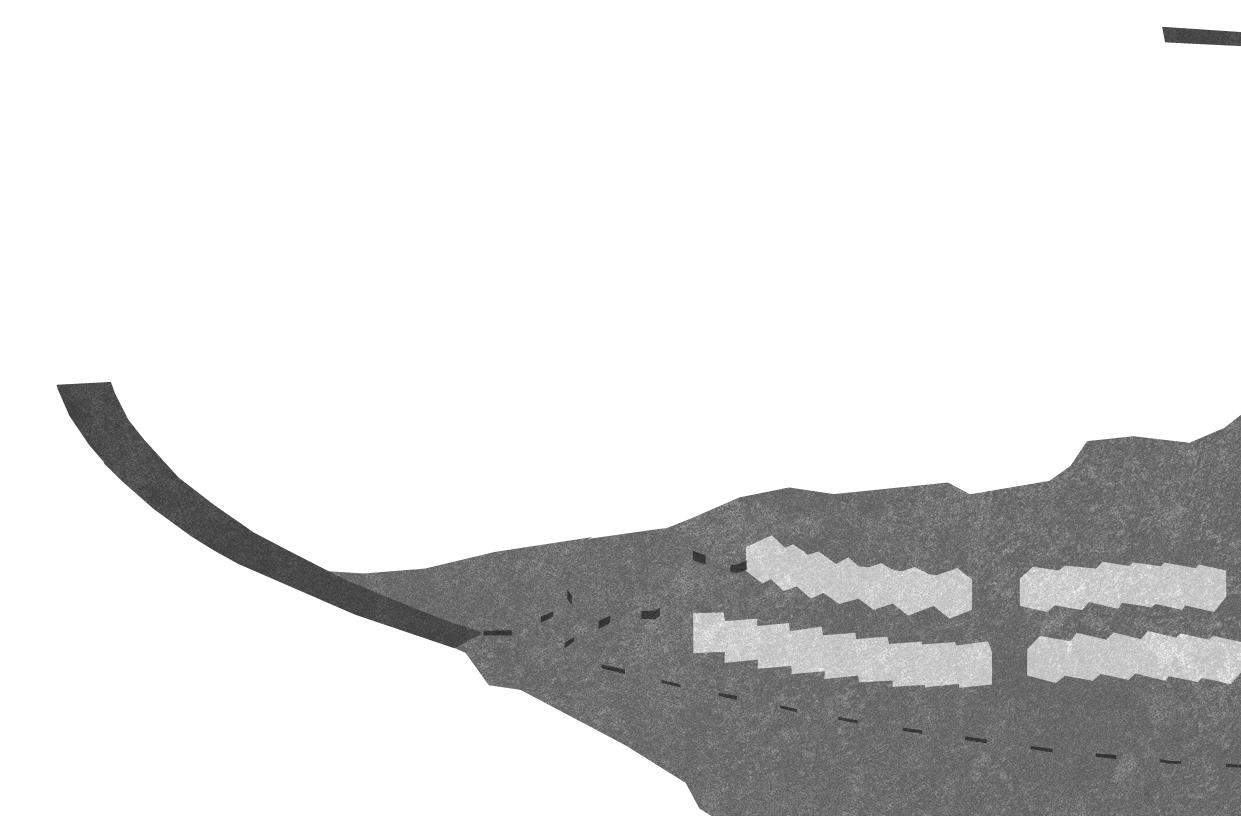

The first to be sacrificed is Northern America, minced up into elongated tentacles of cul-de-sacs. Asia is also cut up into long pieces of alternating land and water. The symbolism of the world map is watered-down to efficient tried and tested real-estate models.The simplification apparently did not manage to turn the project around. Terraformed landscapes are abandoned for a few years, and nature has started to take over.

This is not an uncommon sight in Batam, with many empty and unfinished buildings lining up the roads, left over from the booms and busts of speculations and recessions. Terraformed projects are abandoned halfway, leaving artificial lagoons and “fingers” of alternating water and land.

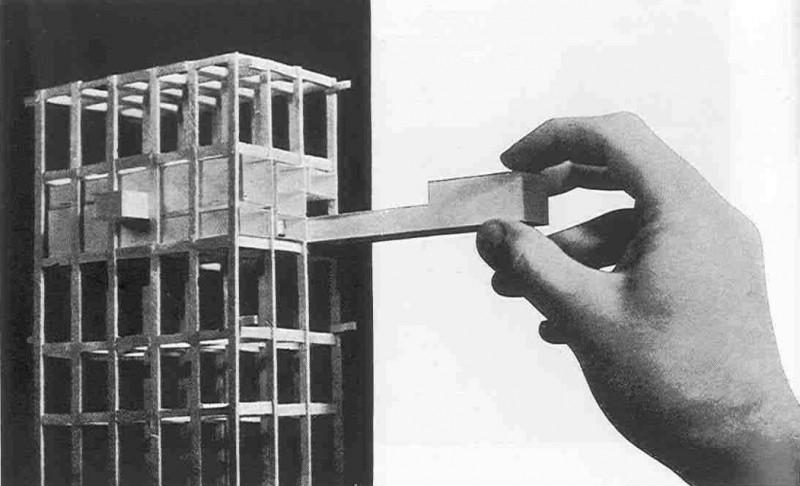

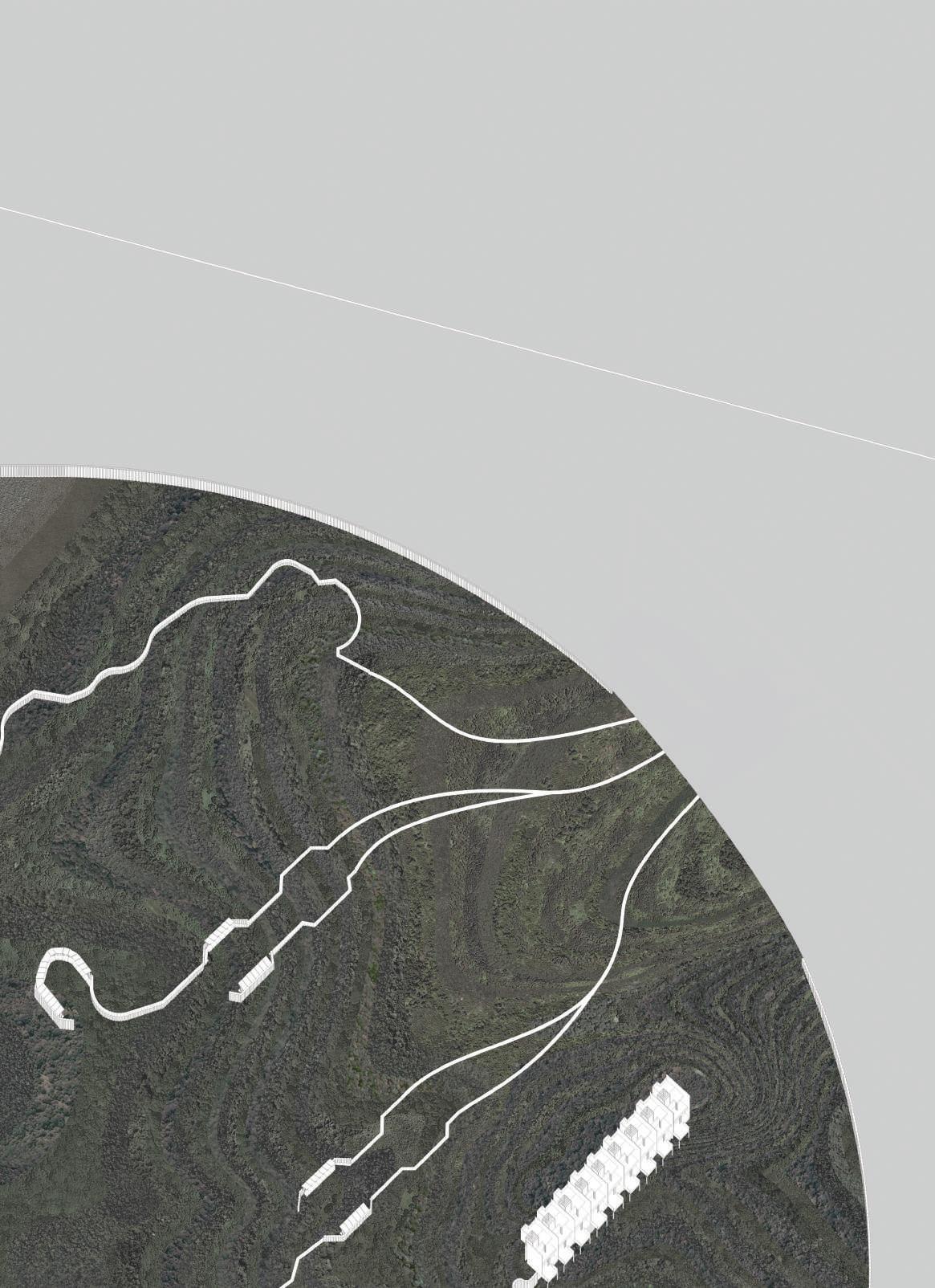

This thesis proposes for the Batam government to acquire Coastarina and convert it from a failed exclusive entity into a public asset. A roadmap for the territory to beautifully decay and grow into a public park. This re-presentation of decay parallels the current discourse of landscape urbanism: the found landscape - the abandoned railway track, the closed landfill - is Architecturalized into a public amenity. However, Architecture in the context of Coastarina has to be minimal, aiming for maximum effect. The main material has to be largely the existing: soil. The normal operations of Architecture has to be transposed to from concrete, glass, and steel to soil, mud, and water. The final result is left to Nature; the Architect can only control so much...

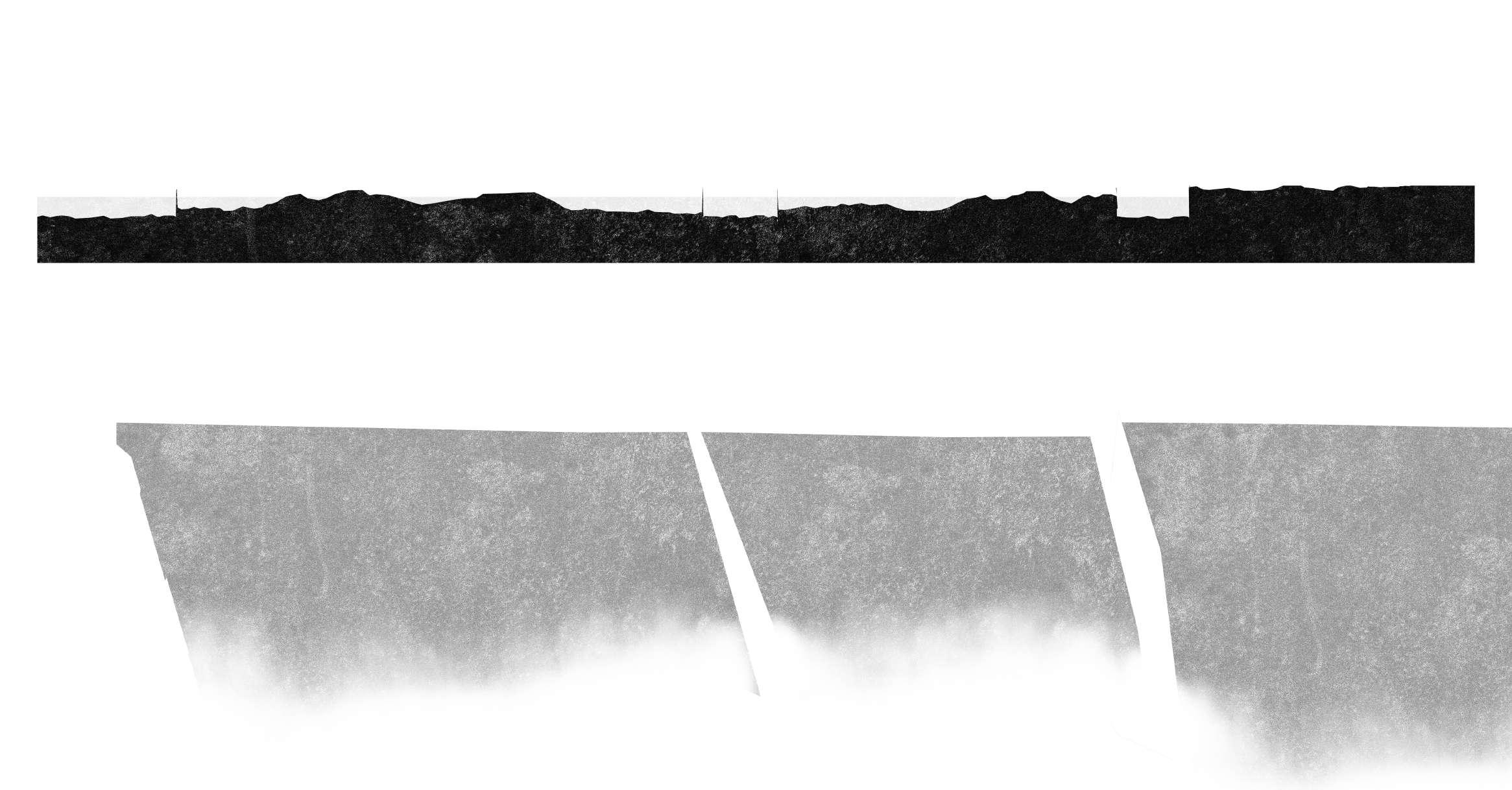

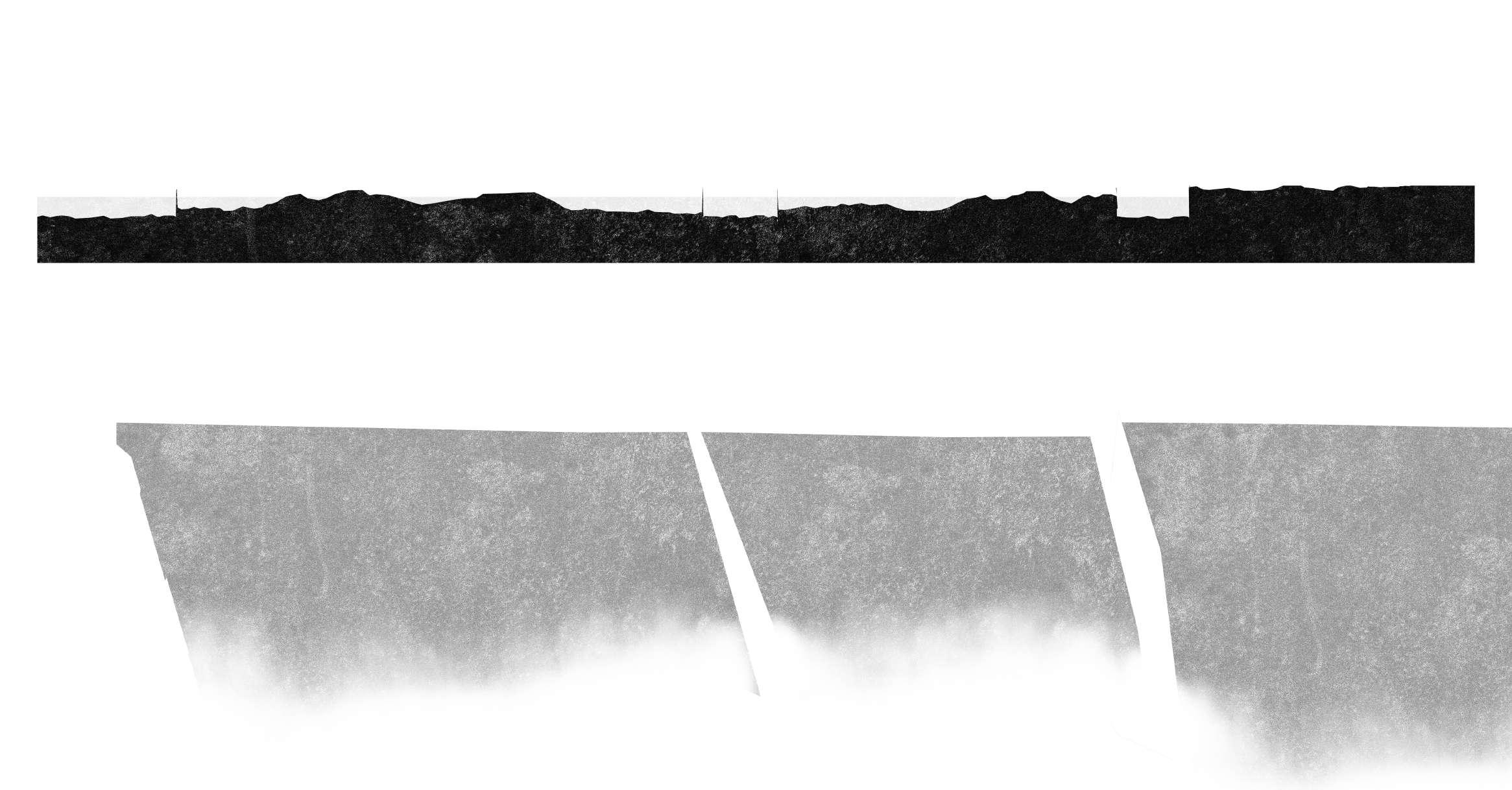

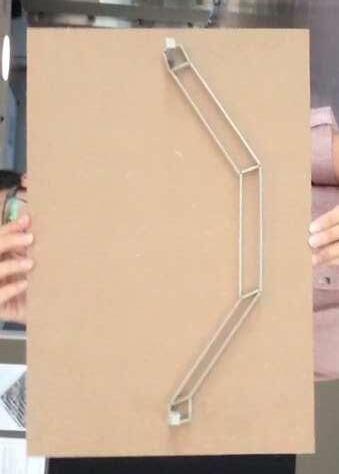

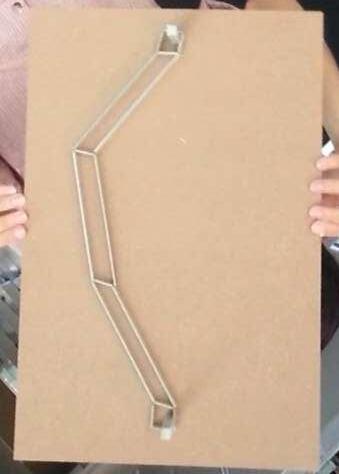

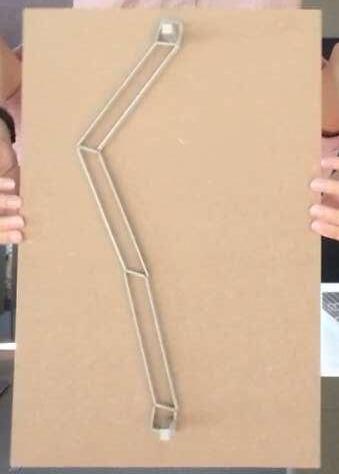

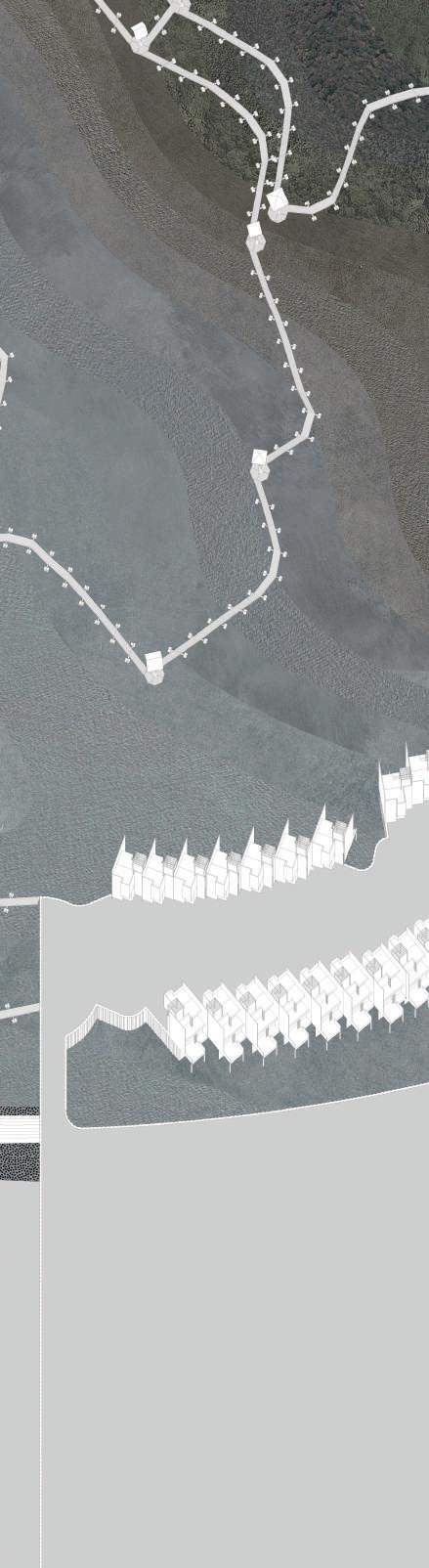

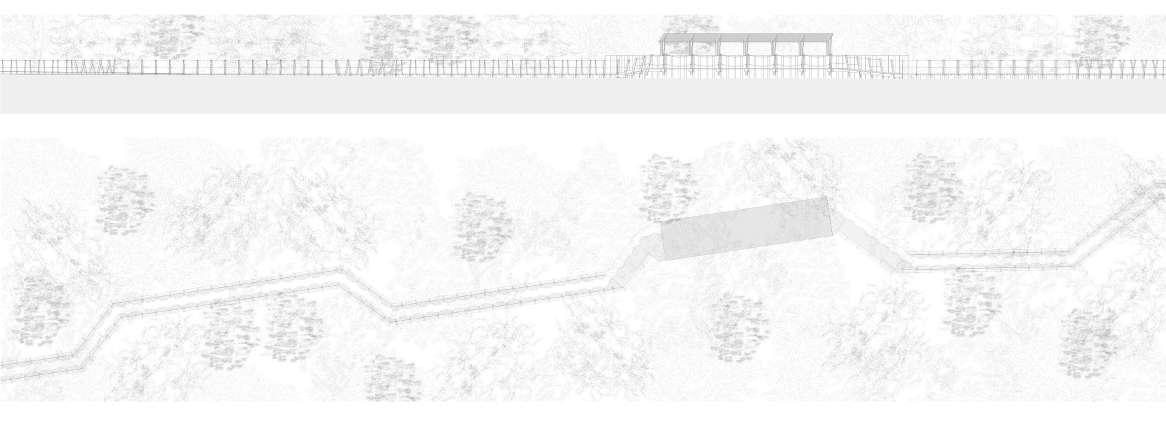

The first phase is largely functional. A breakwater is constructed to replace the current make-shift one. It follows the original gesture of an enclosed ellipse. The breakwater cannot fully block the flow of water to prevent the area within from getting stale, so it is carefully calibrated such that it slopes down to form a low point. It gives way to incoming water during high tide twice daily. Visually, this would form 2 long jetties that slowly touch and separate from each other. On the outer side of the breakwater is a slope of rock armours to break the incoming waves. The inner side is designed to form concrete steps, creating an inward-looking space.

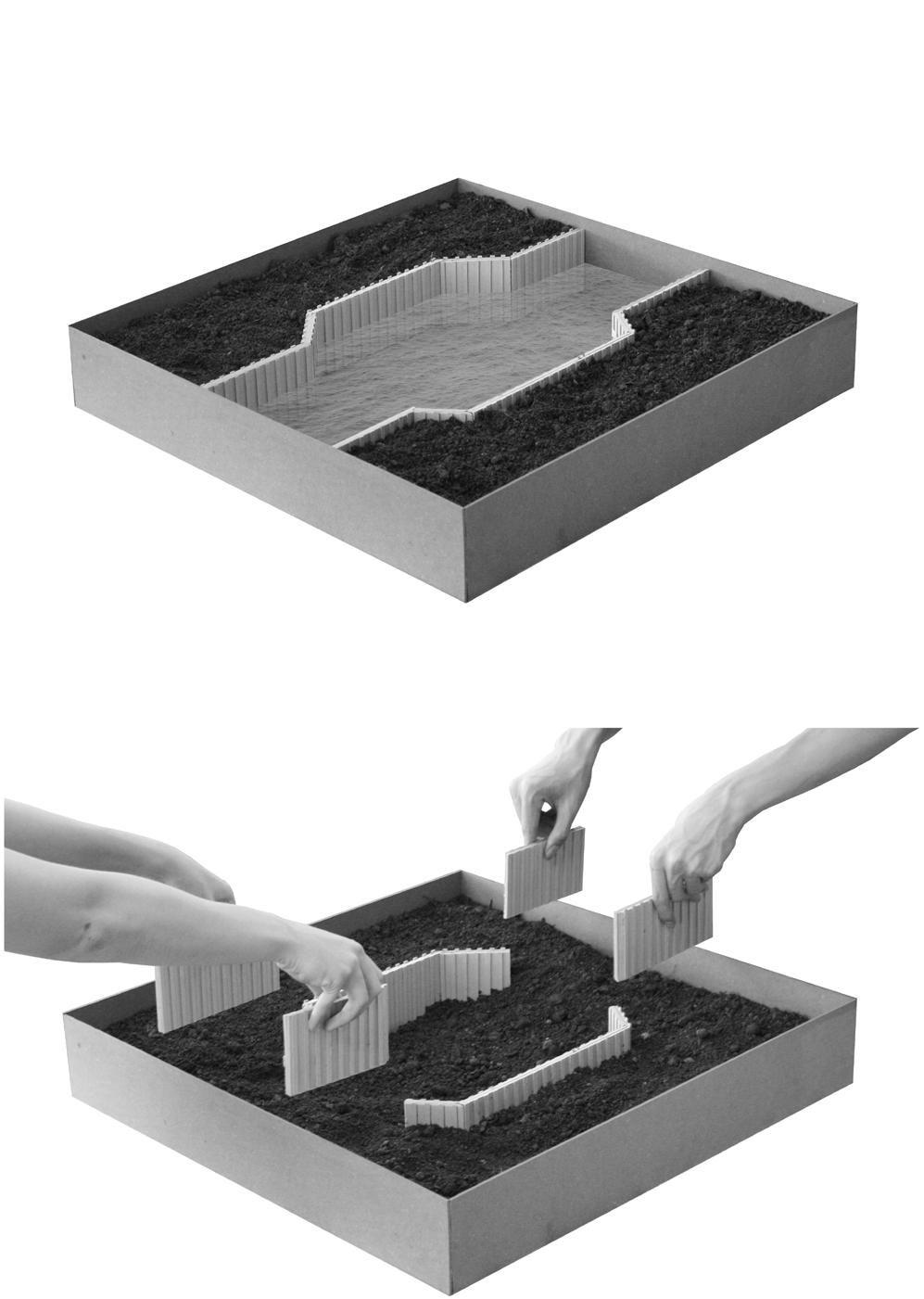

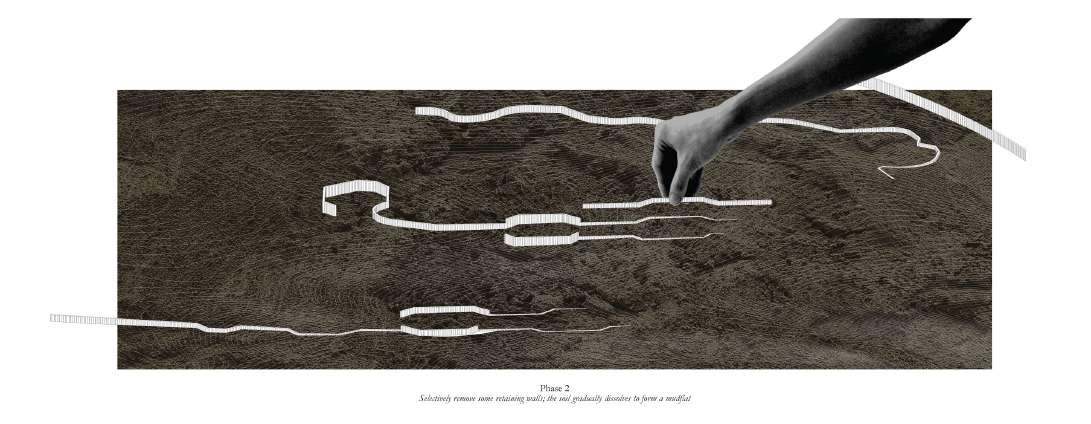

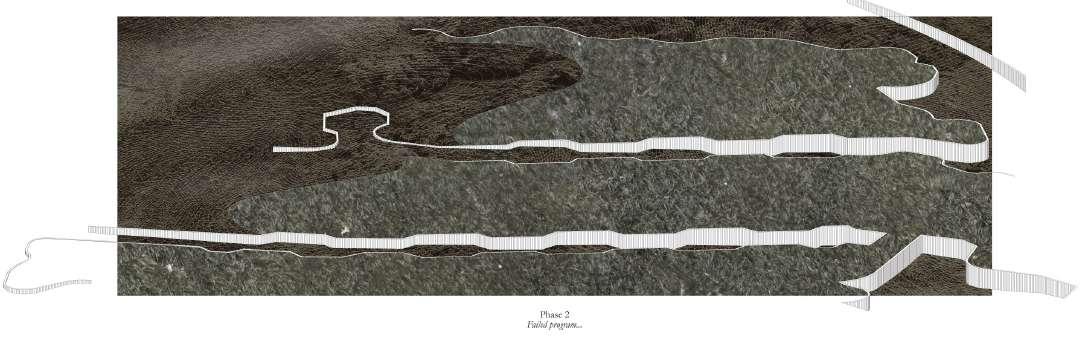

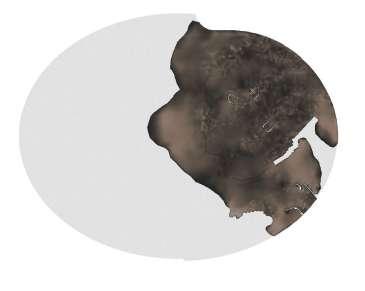

In phase 2, selected portions of the retaining walls in Asia are carefully removed. As the tide floods and ebbs, the soil slowly sinks and stabilizes into a larger area with a very gentle gradient. Computational Fluid Dynamics simulations were employed to approximate how this may happen. This hopefully brings back the intertidal zone that was truncated with the previous land reclamation. Many flora and fauna would start to appear in this rich ecosystem, occupying separate parts of the low and high tide zones. The remaining retaining walls would protrude from the sinking soil. Light horizontal additions can be attached to them to form walkways and observation hides.

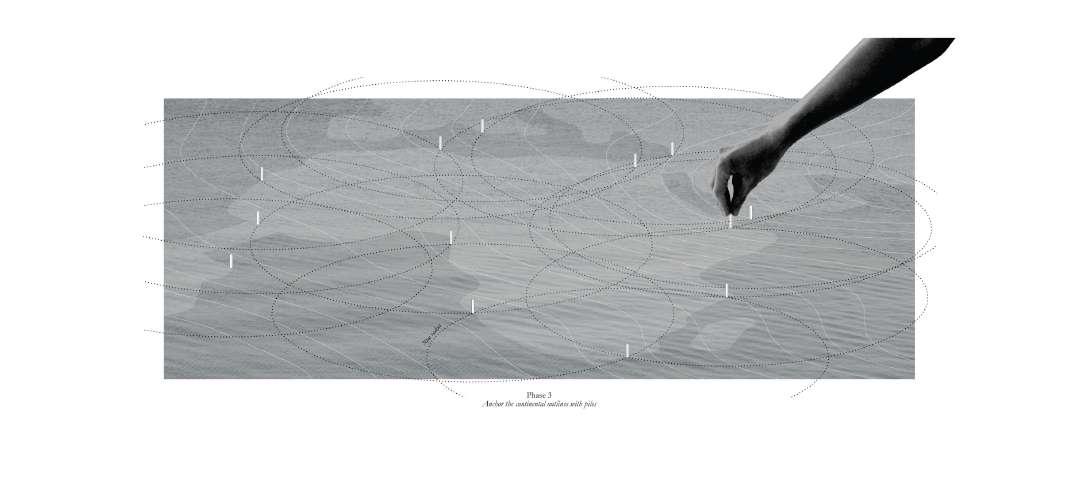

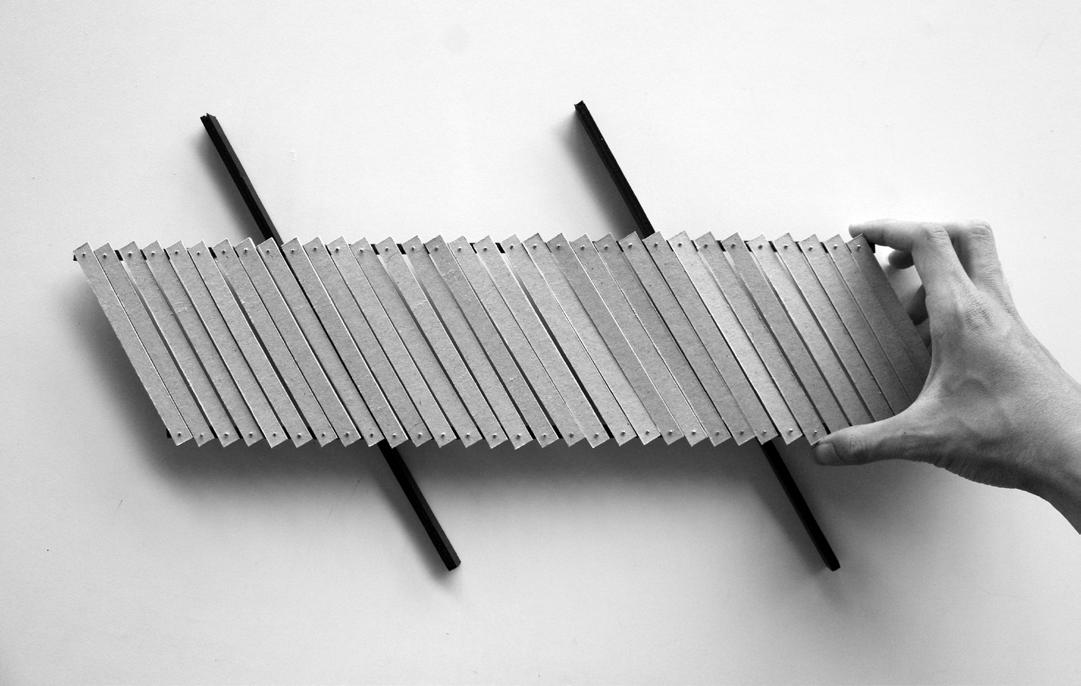

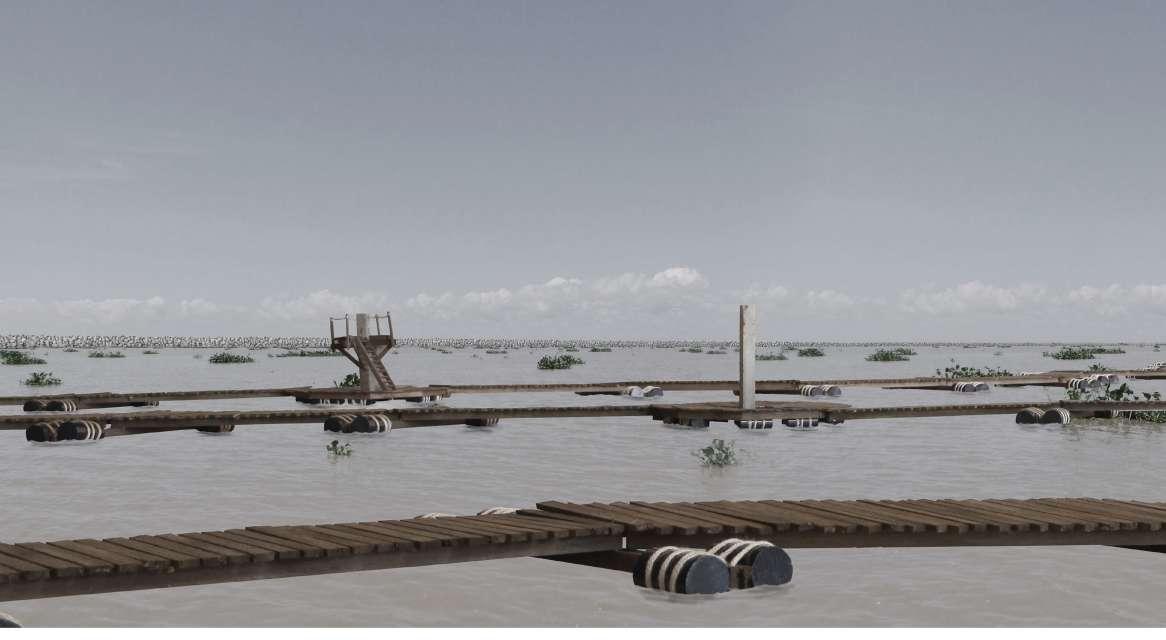

In the final phase, the shape of the World is physically anchored in the easiest way. Concrete piles are inserted every 70m along the imagined continental outlines. The piles can be connected thereafter with floating pontoons. These pontoons do not resist, but flow with the incoming and outgoing tidal currents. They slowly deform, sometimes becoming slightly thinner, sometimes thicker, according to the angle. Light superstructures can be subsequently added to the piles to form different pavilions. These would puncture the meandering pontoon paths in the park.

The normal operations of Architecture has to be transposed from concrete, glass, and steel to soil, mud, and water.

Selectively remove some retaining walls; the soil gradually dissolves to form a mudflat

Anchor the continental outlines with piles

Phase 3

Pontoons gradually link the piles; vague outlines of the continents slowly emerge

The visitor would enter the park from Asia along dirt paths down. And when the soil becomes too muddy to walk, they walk on top of the retaining walls, among the lush vegetation and into observation hides, where they can rest and lookout for some animals. Some of the retaining wall paths lead down to the floating pontoons, first among the middle zone that changes from mudflat to water according to the tides. And finally out into the open horizon of meandering paths punctuated with pavilions to take a rest.

“The house is a machine for living in.”

Le Corbusier’s first love was the ocean liner. He was so infatuated with the sea view that he brought it inland.

In the hands of the capitalist, the view has to be maximized and multiplied. Through the slivers of sea view, Villa Savoye has to be duplicated vertically.

17 reservoirs

32 major rivers 7000km canals & drains

The real-estate machine betrays the land-scarce myth. As Singapore’s coastal edges stretches out, its inner coasts duplicate, in the name of survival and luxury.

27 pilot projects 100 long-term projects

Singapore’s ABC mechanism serves the dual purpose of real estate appreciation and public service. Private developers replicate only the products, stripped of its utilitarian function.