Guest critics, lecturers and consultants

Erik L’Heureux

Chang Jiat Hwee

Abel E. Tablada de la Torre

Aloysius Iwan Handono (JTC)

Bij Borja (JTC)

Tang Hsiao Ling (JTC)

Estelle Chan (JTC)

Norliza Difari (JTC)

Lim Ee Man, Joseph

Chan Weng Tat

Adrianne Joergensen

Liew Pheng Heng (M&E)

Yacine Bouzida (Structural)

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank the above individuals in providing valuable advice and guidance throughout our design studio. This publication would not have been possible without their dedication and patience.

Content

Foreword

Acknowledgements

Precedents

IBM Building, Hawaii

by Vladimir OssipoffAmerican Cement Building, Los Angeles by

DMJMWing On Life Building, Singapore

by James Ferrie Architects and Partners

Perpetual Savings Bank, Los Angeles by Edward

Durell StoneKandalama Hotel, Sri Lanka

by Geoffrey BawaAyer Rajah Industrial Estate

Site Photographs

Site Analysis

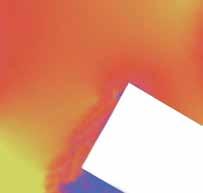

Shadows

Solar Insulation

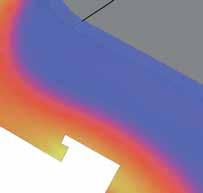

Wind

Acoustics

Traffic

Rain/ Drainage

Programme

Existing Building Drawings

Plot 1 (Bloc k 47 + 51)

Plot 2 (Bloc k 55)

Plot 3 (Bloc k 67)

Plot 4 (Bloc k 71)

Plot 5 (Bloc k 79)

Content

Proposals

Trinity (Plot 1, Block 47 and 51)

by Azizul Izwan, Joel TayConoid Bulding (Plot 1, Block 47 and 51)

by Josef OdvárkaA Timber Shell (Plot 1, Block 47 and 51)

byYeow Bok Guan

Weathered Factory (Plot 2, Block 55)

by Leo Huang and Wong May Ping

Dogmatic Envelopes (Plot 3, Block 67)

by Quentin Sim and Shawn Teo

Dual Exoskeletons (Plot 4, Block 71)

byCour tyard Office (Plot 5, Block 79)

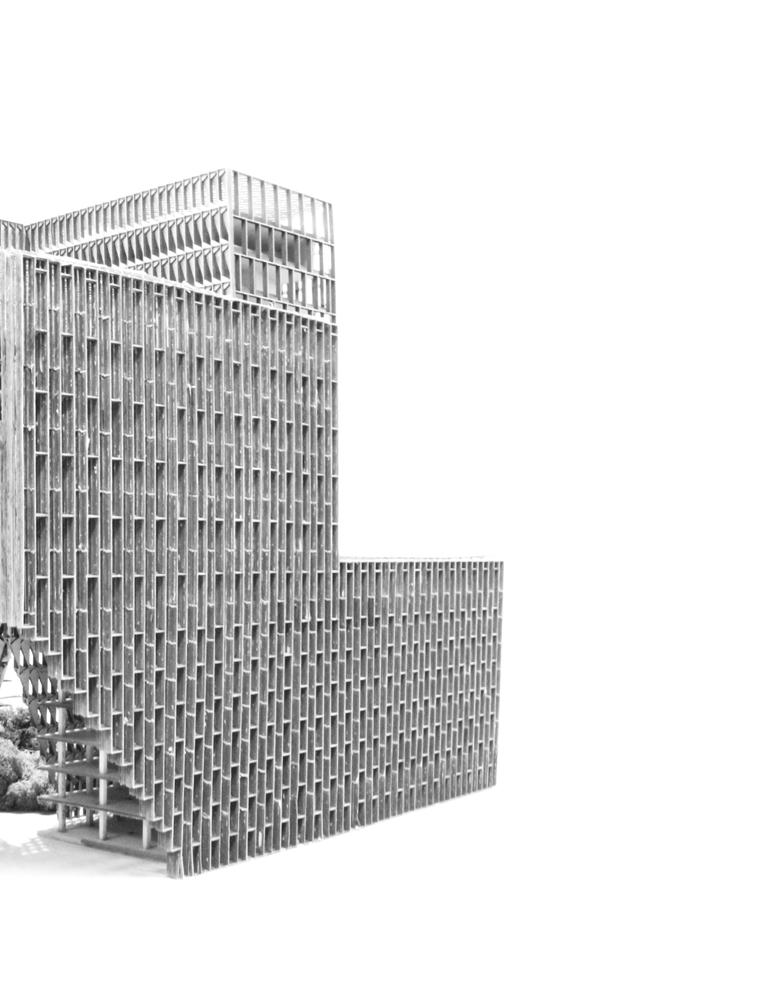

IBM Building, Hawaii, USA (1962)

byVladimirOssipoff

byVladimirOssipoff

Perhaps we might be able to see Vladimir Ossipoff’s architectural underpinnings through theexecution of the IBM Honolulu building. A glass block with regular vertical mullions would formally associate itself with the International Style espoused in America. Realistically, such a climatically controlled environment lives up to the building’s intended program which is not contended upon. Yet, its outer veil edges for a further critique of Hawaiian modernism in terms of its aesthetic quality and climatic response.

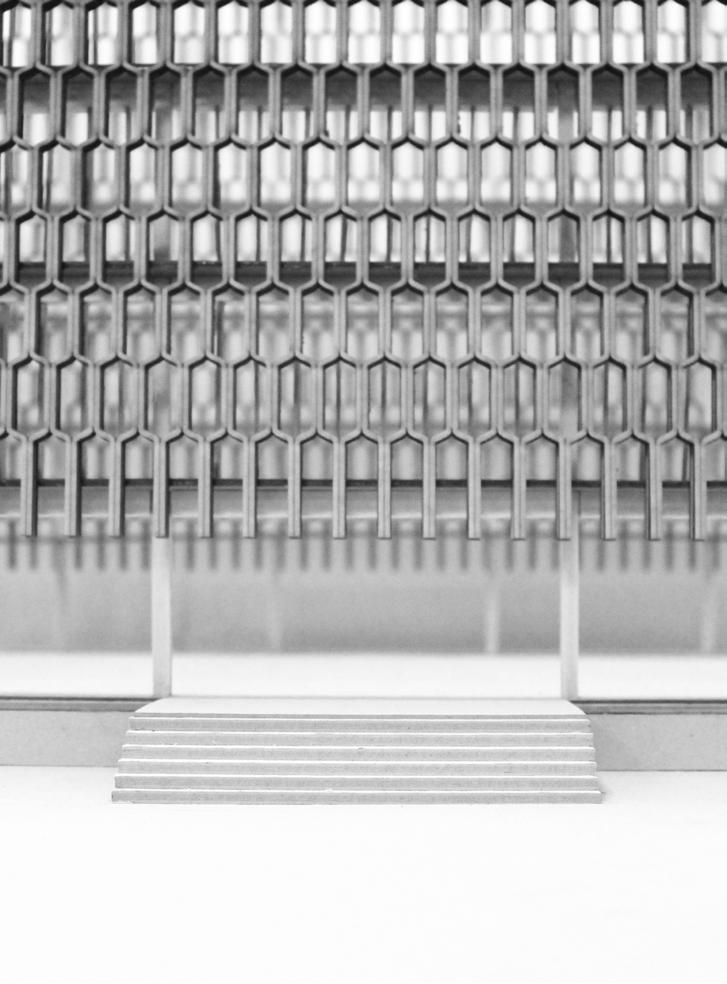

While the project was taken over by Ossipoff from his colleague Fisk, Ossipoff’s design approach was original. We can summarise them into three main points.Firstly, he wanted to mediate the climatic conditions of Hawaii through the use of pre-cast concrete grilles over the Miesian glass façade. This also ties in with his second preoccupation which is to inculcate Hawaiian sensibilities in his architecture. In addition, this determined his iteration of the grille that was designed based on Polynesian decorative patterns alongside IBM computer punch cards. Thirdly, Ossipoff had to project IBM’s growing global stature which culminated in a series of building projects during the 1960s and 70s. IBM needed to improve its image for its controversial commercial involvement with Nazi holocaust documenting operations by its German subsidiary, Dehomag. Furthermore, the building was conceived in anticipation of Hawaii’s recognition for statehood in 1959.

Heat in sub-tropical Hawaii almost predetermines its Architecture, especially with an annual mean temperature of 21°C. IBM Honolulu is strategically orientated approximately North-South to reduce direct solar heat gain. In developing a Miesian glass box office building, it was crucial that the envelope performs thermally to minimise energy consumption. Brise soleil encourages passive solar heating while reducing reflective glare to the surroundings. Hence Ossipoff designed a distinct 400mm thick concrete grille made up of a relatively high composition of tricalcium-aluminate (C3A) which was proven to be highly strong and durable since 1962. The envelope was made up of a relatively geometrically complex screen consisting of 1360 precast concrete pieces. Also, there is a reasonable buffer of 1 metre from the envelope’s outer edge to glass curtain wall which significantly reduces interior heat gain.

Nonetheless, the office building had to be thermally controlled through mechanical means within the glass block. A centralised HVAC system was designed within the core of the building, assisted by a number of rooftop ventilation exhausts for this 6 storey medium rise. However, we simply cannot ignore how significant this shaftlike envelope is beyond its thermal performance.

Honolulu experiences a monthly average of 113mm of rainfall, close to one third of Singapore’s rainfall.Yet, Ossipoff factored in the maintenance issue for his crucial but elaborate façade. Ossipoff wanted to manage water runoff and potential streaking by incorporating 45° angles at regular intervals throughout the façade. Moreover, there were no ledges or holes to collect dust. It is important to credit the level of craftsmanship and engineering in which no visible signs of wear and sprawl were identified even during its restoration of 2014, thereby attesting to Ossipoff’s initial claim for quality building’s performance. As aforementioned, the building had to be climatically controlled to serve as an office building for IBM thus natural ventilation was not exactly applicable despite Honolulu’s strong North eastern winds (15mph) and low urban typography around the site.

Looking through his oeuvre of work, one readily identifies his maturity in architecture discernment from the large eaves of relatable Hawaiian vernacular to open plans and International style architecture vocabularies with a certain regard for regional identity.

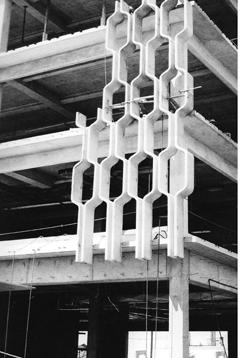

American Cement Building, Los Angeles, USA (1964)

byDaniel,Mann,Johnson&Mendelhall(DMJM)

byDaniel,Mann,Johnson&Mendelhall(DMJM)

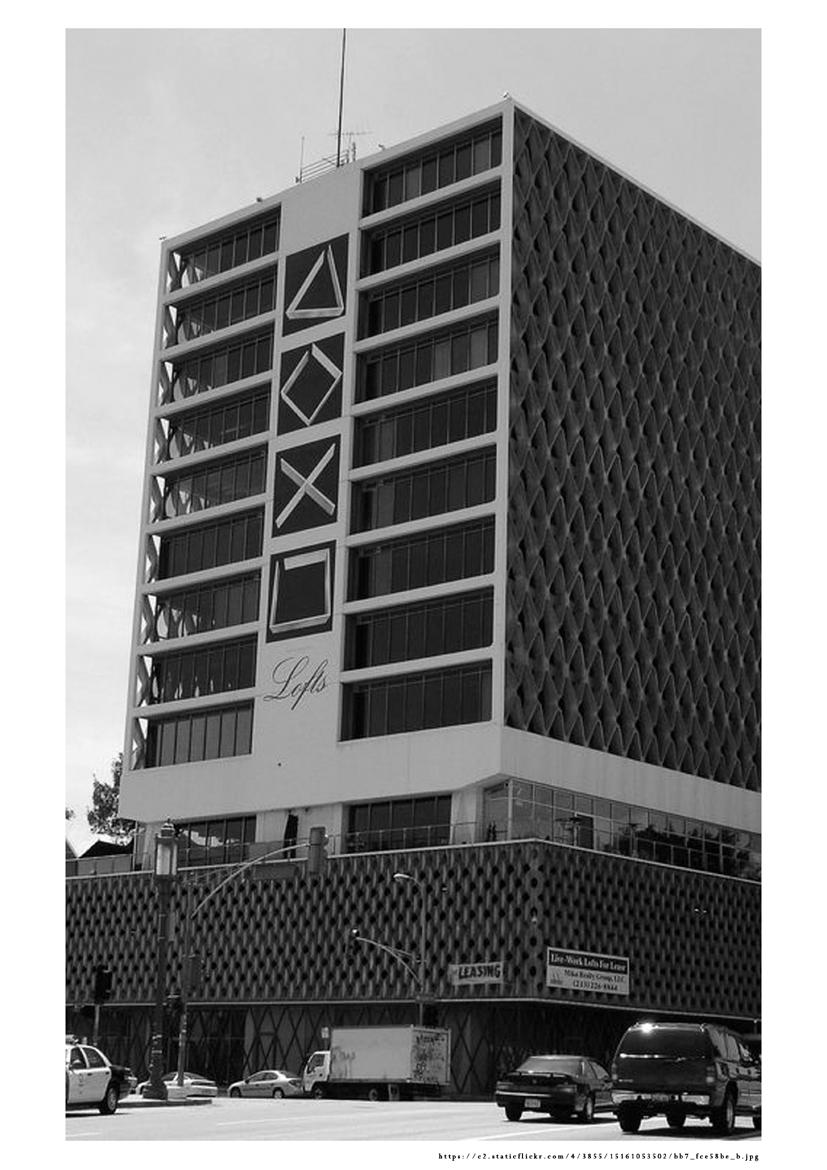

The American Cement Corporation decided to build a new headquarters that promoted reinforced concrete as the “the building material of the future” in dramatic fashion.

Owners Edward Rothschild and Arthur Gilbert bought the site opposite MacArthur Park, just east of downtown. They with DMJM specified the design for column-free office space; met seismic codes with concrete shear walls or diagonal bracing; and was cost competitive with non-concrete structural systems and materials.

Out of eight bidders Kiewit won the construction contract for offering the best cost and efficiency in delivering pre-cast members.

DMJM designed the 13-storey building as a two–unit structure: a 4-storey base for parking, ground floor shops, lobby, and executive offices; and a 9-storey tower, with each floor containing 12,000 sq. feet speculative space. The shear-resisting and load-bearing concrete service core extended through the tower and housed four elevators, stairs and utilities. It was cased using the slipforming technique that saved about 3 months of construction time. The tower grill performed dual decorative and structural roles. It was composed of 225 X-shaped reinforced concrete elements that were prefabricated off site. Together with pre-cast floor beams and central core it formed a more conventional beam-and-column system allowing designers to open the office space. Crews used the cast-in-place floor slabs to tie all those elements together. The grillwork that wrapped the parking area was designed for decorative and ventilation purposes.

Hot

Because the temperature in Los Angeles stays reasonably high, the building does not have a heating system. The pre-cast concrete X-shaped members provide general shading. For the extra shading tenants have installed curtains.

Wet

Los Angeles does not have very high precipitation levels, however any rainwater that gathers, runs down the façade into trays filled with pebbles.

Breezy

The American Cement Building incorporated mechanical and HVAC engineering in project planning and design. The building was cooled using natural gas-powered absorption refrigeration unit that the subcontractor installed on the roof. The absorption unit received a lot of criticism as an inefficient and cumbersome with the life expectancy of fifteen years. This system was replaced into air conditioning system after about ten years.

In the current system, according to the Manager of the building, each unit has their own HVAC system in the building. (Packaged System). In addition to that tenants can open the sliding windows on the north east and south west facades.

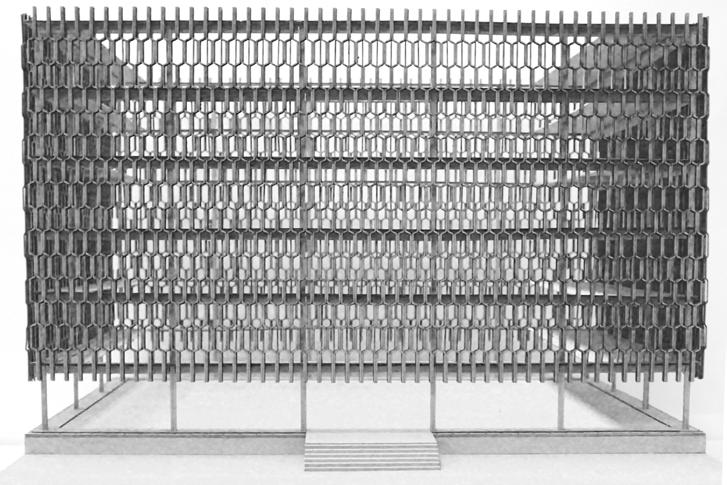

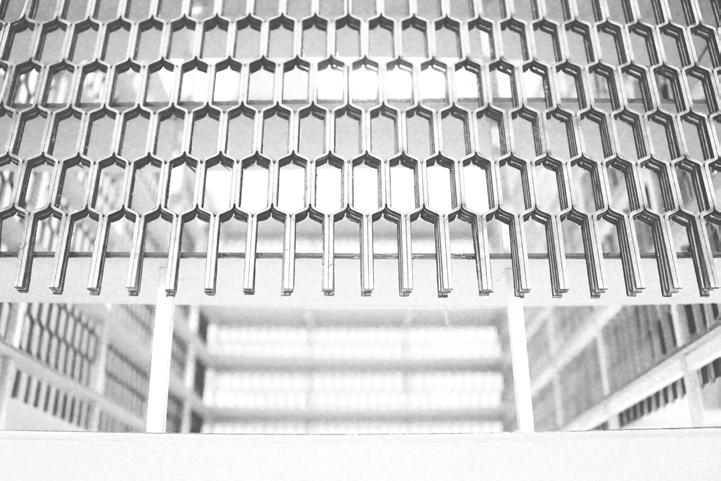

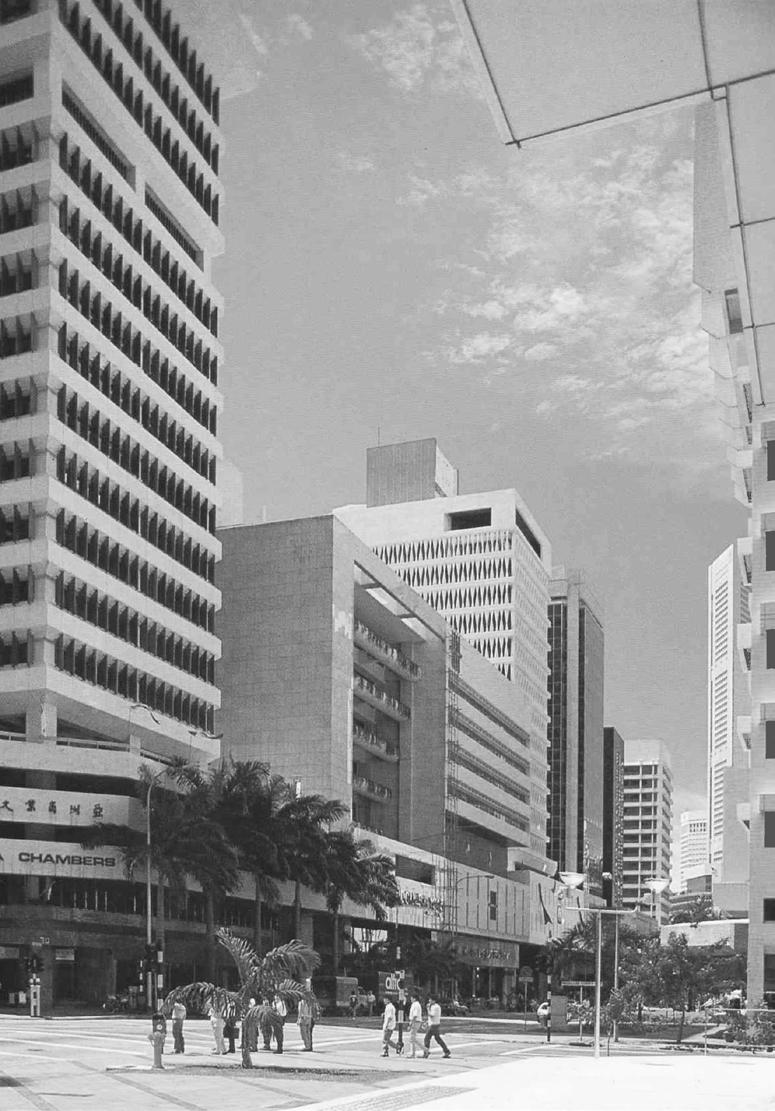

Wing On Life Building, 150 Cecil Street, Singapore (1975)

byJamesFerrieandPartnersLocated along Cecil Street and Stanley Street, the Wing on Life Building, later known as AXA Life Building, was constructed by James Ferrie and Partners architects. The pioneer architect was known for his works such as Van Kleef Aquarium and Odeon Cinema which had shaped the Singapore landscape in the 1970s. The building, on a site coverage of approximately 30 metres by 40 metres, was completed in 1975 at the cost of $25 million to serve as an office tower in the developing financial hub. The 64 metre building comprises a podium block made up of the mezzanine floor and two upper floors and the tower block from the fourth level onwards. The structural core consists of 2 escape staircases, 3 passenger lifts, 1 cargo lifts and 2 AHU rooms.

Structure

The 20 storey building, including two basement levels for carpark, comprises of the podium block which is supported by 6 structural columns. 12 storeys of uniform office spaces and the penthouse sit on the podium tower. The distinguished architectural feature is the twisting structural concrete mullions (100mm thick) on the periphery of the tower block. These twisted mullions are four times stronger than straight mullions. Additionally, the floor slabs are constructed with pre-stressed concrete. Column-free interior is apt for an open office concept.

Sun

Besides functioning as structural support, the twisted concrete mullions operate as sun-shading devices in the tropical setting from direct sunlight on both the East and the West. These mullions shade approximately 45% of the direct sun rays into the interiors. In addition, the floor slab overhangs at 900mm from the windows to shade the interior from the sun. Tall buildings along the Cecil street shade partial sunlight on the east elevation while the shop houses along the Stanley road allow sunlight to fully hit on the west elevation.

Rain

The annual rainfall count stands at 2450mm in Singapore. Rain are presumed to hit on the overhang and window panels as surface runoff. 300mm high and 150mm thick concrete curbs prevent the rain from entering into the interior. The tapered beam on the foot of the tower block directs the surface runoff into the drains of approximate depth 1 metre on the roof of the podium tower. Water flows through the pipes of 8 inches into the sewage beneath the ground.

Breeze

The prevailing wind in Singapore travels in 2 directions – from the North-north-east during November to April and from the South-south west during May to October. The interior is enclosed with glass panels and operable windows for emergency situation. Designed as a fully air conditioned tower, the building is installed with a centralised air conditioned system which comprises of a cooling tower and chiller to direct chilled water to the AHU units on each level. The AHU then supplies cool air and receives warm air which circulates within the unit. Due to the low speed and position of the core, natural ventilation within the office space is inefficient.

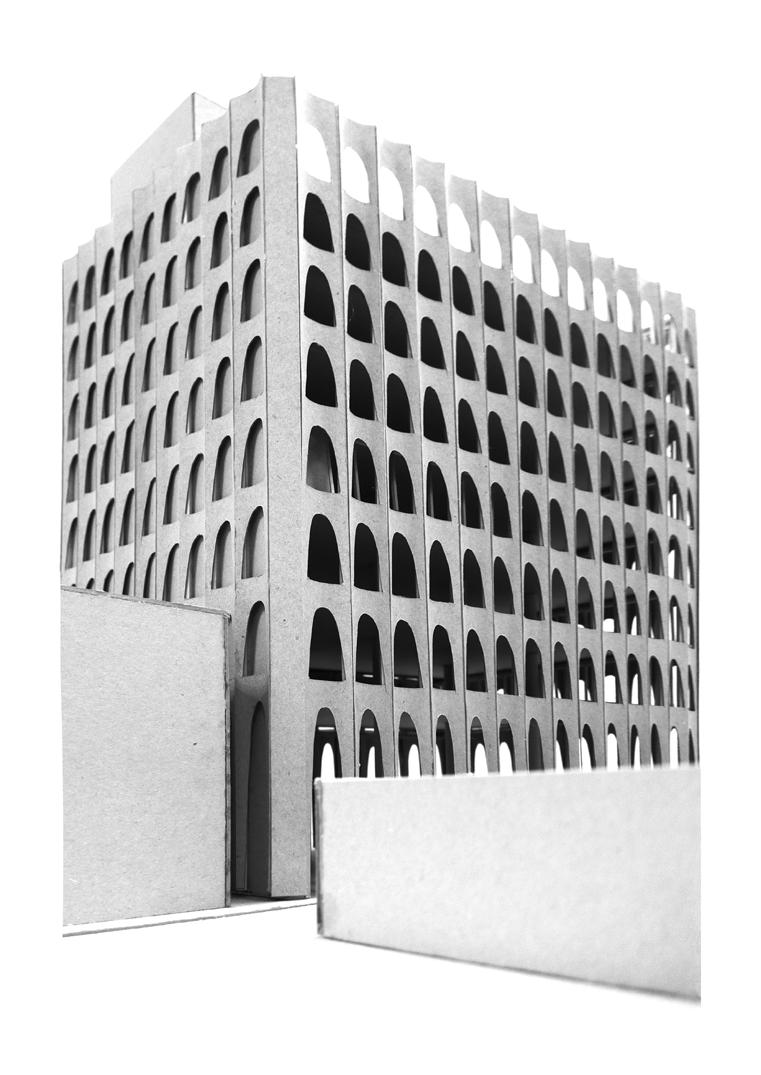

Perpetual Savings and Loan, California, USA (1961)

byEdwardDurrellStoneHot, Wet and Breezy

Situated in Beverly Hills, California, the building’s climatic context is Mediterranean; hot and warm most of the year. Recorded Average High of 29.4 deg. Celsius in August (Summer) and 19.5 during January (Winter). Annual average rainfall of 460mm, with most precipitation during Winter and very occasionally during Summer.

The characteristic envelope could be described as a thermal shell, encasing a glass interior. An undulating scalloped surface coupled with arched openings echoes a deconstruction of the colosseum. Such is the American New Formalism of the 1960s. A neo-classical monumetality that is read visually as an articulated skin, accompanied by a front plaza and a carpark in a similar language.

The interior is separated by a perimeter of window-walls set 2 feet from the scalloped envelope, creating a climatic buffer zone which seems to offer a degree of passive cooling. Planters at every arched opening suggests further shading offered by draping plants or creepers.

The building’s mechanical ventilation systems are situated at the west-end core, with the two elevators and service stairwell.

Structure

The building envelope is structural. Bearing floor loads in order to reduce the number of structural columns within the interior of the building. This is accompanied by the primary structural core on the west-end of the building. This strategy of shifting the structural mass outwards serves to free up and shade the interior space.

Plastic-formed concrete explains the sculptural articulation of the scalloped surface upon caternary arches, while still serving as a structural envelope. Each floor is directly connected to this envelope as a suspended concrete floor slab, in tandem with only 6 circular profile structural columns. Creating three 24-feet bays along the transverse section , spanning a total of 64 feet.

Intent

A redundant (or excessive) continuation of the scalloped envelope to the west-end of the building, encasing the core highlights the intent of a thermal shell. Furthermore, an unexecuted 9th floor roof garden also suggests that the architect had intended for a vegetated shell, embedded into the building’s structure, to serve as a climatic envelope.

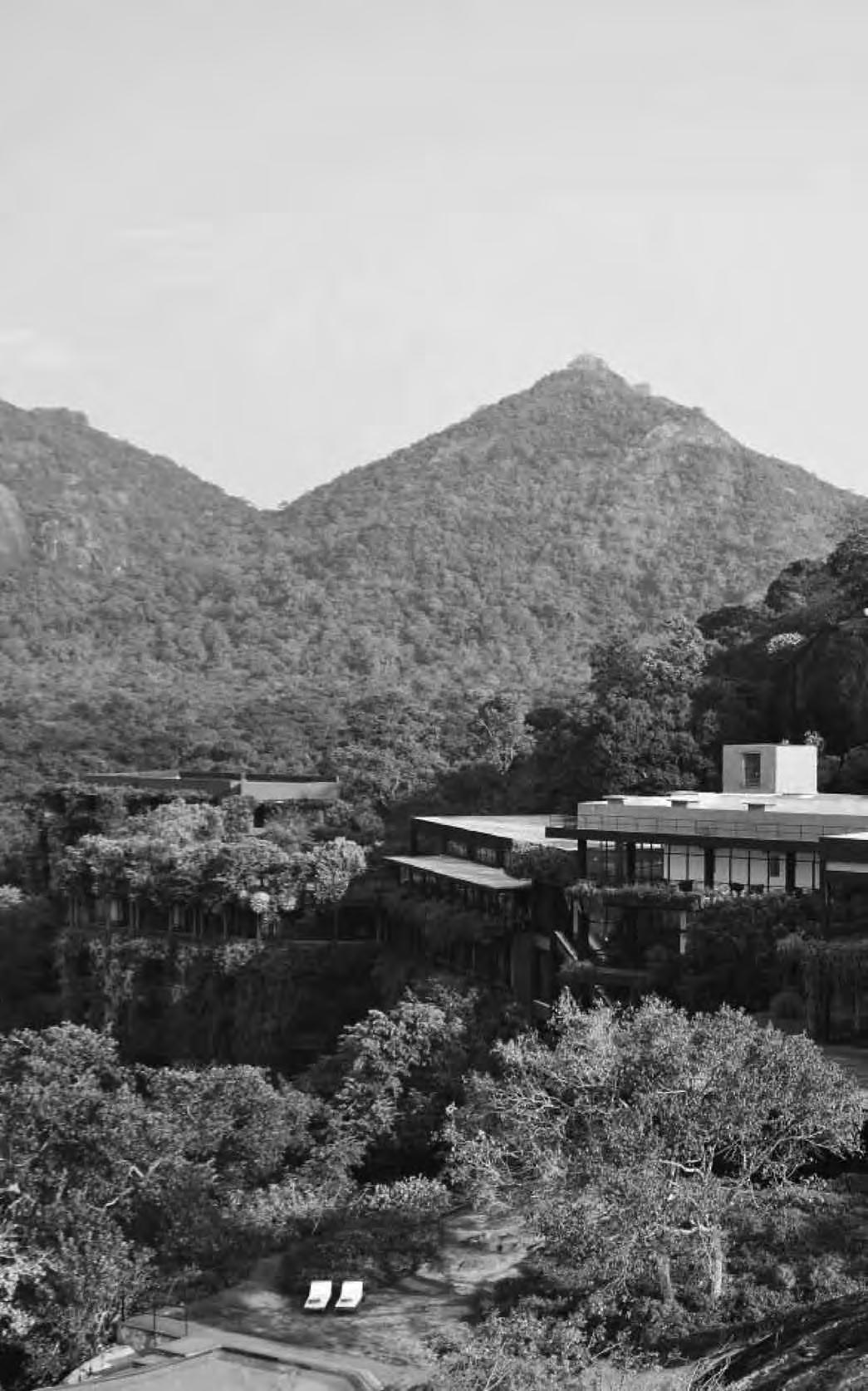

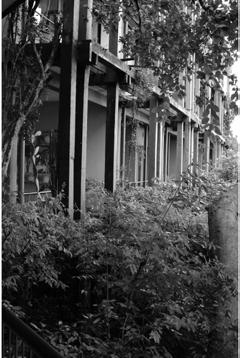

Kandalama Hotel, Dambulla, Sri Lanka (1995)

byGeoffreyBawa

byGeoffreyBawa

The Kandalama Hotel sits in a site of wilderness, against the backdrop of a rock mountain, overlooking the Sigiriya Rock fortress across the Kandalama Lake.

The hotel can be seen as a combination of parts. The hotel rooms are protected from the elements by layers that are loosely wrapped around the core to cater to a climate that is hot, wet, and breezy.

The building sits lightly on the natural landscape atop two rows of columns, allowing an unobstructed flow of rainwater down to the lake and to minimize impact on the landscape.These columns form the under layer which cools the building. Such a strategy keeps disruption to the natural site to the minimal.

On the front elevation, the balcony and planter boxes provide a transition space to the exterior.The balconies are separated from the room by a full-height glass door/ window, washing the interiors of the rooms with plenty of natural daylight. On top of that, is a visually lightweight structure that is built in concrete. Overhanging timber beams, secured to the concrete columns, and the lush vegetation that hang from the concrete structure, forms a natural curtain that mitigates glare and the over-lighting of the interior spaces. Up above, the rooftop garden above the rooms absorbs heat and acts as an insulator.

On the other side of the rooms, a stretch of naturally ventilated verandah is aligned to the entrances to the rooms. The rock mountain behind the building shelters these corridors. As rock has a high thermal mass and specific heat capacity that efficiently stores heat in the daytime and releases it back at night, the rock formation is being used to passively cool the building.

Aside from strategies to keep the building breezy and cool, water purification, collection and run-off were also key motivations of the building. Given that the hotel is situated in a dry climate, flat roofs were material efficient and adequate in receiving rainwater. The roof extended to the edge of the building where planters were located to receive water runoff. Additional water was treated through natural permeable rock and channeled to the lake. Water used to sustain the hotel activities was pumped up from deep tube wells that ensured safer drinking water.

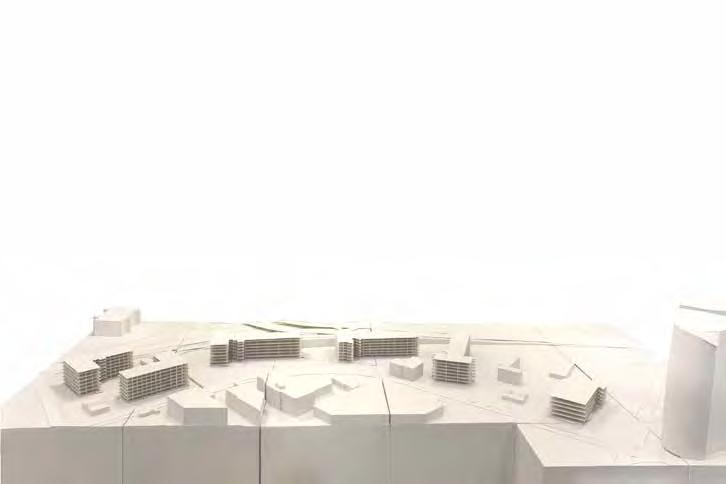

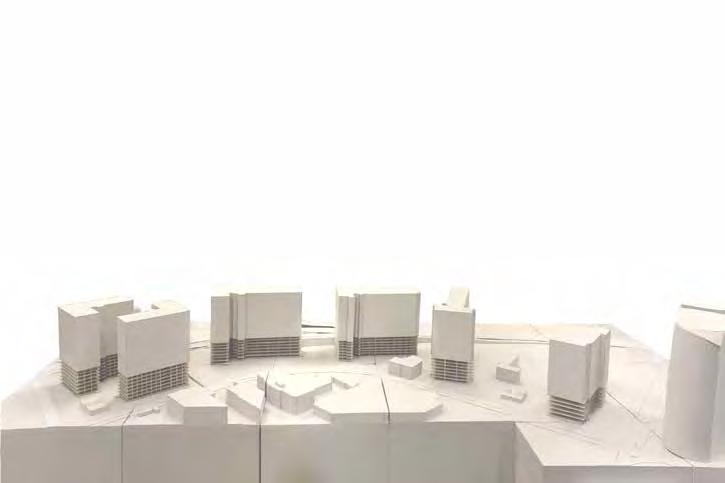

Ayer Rajah Industrial Estate

The architecture of Industrial buildings located in the hot and wet climate of Singapore proposes unique challenges to architecture design at two scales: District and object envelope. These two scales are highly interrelated both as sites of techno centric knowledge related to increased performance (minimizing heat island effects, improving wind channelling interrelationships, improving solar shading between and among buildings) as well as extending a long history of architecture and climatically responsive approaches.

The semester’s research utilizes the site of Ayer Rajah as a case study to research the effects of industrial buildings and their impact on the district and its immediate surroundings. Design prototyping through the design studio will serve as the basis for the research program through three probes.

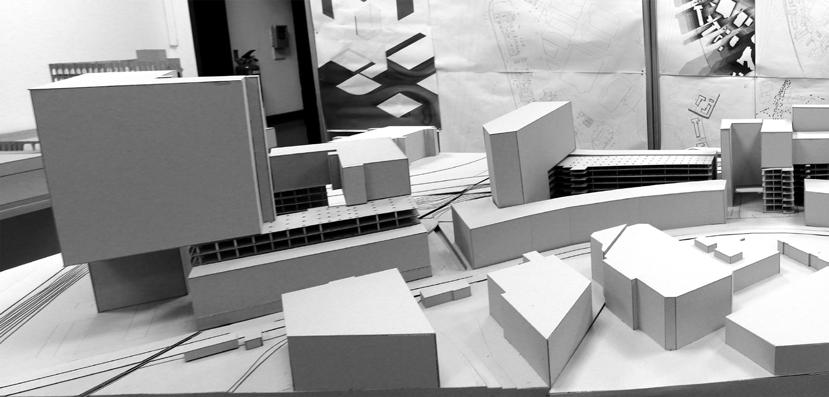

Trinity (Plot 1: Block 47 + 51)

byAzizulIzwan,JoelTayThe idea of the “trinity” could perhaps be best explained by the egg, composed of the shell, the yoke and the egg white. The three are distinct, yet are one “substance, essence or nature”. While the three are to be read as a whole, they can be understood as three individual entities.

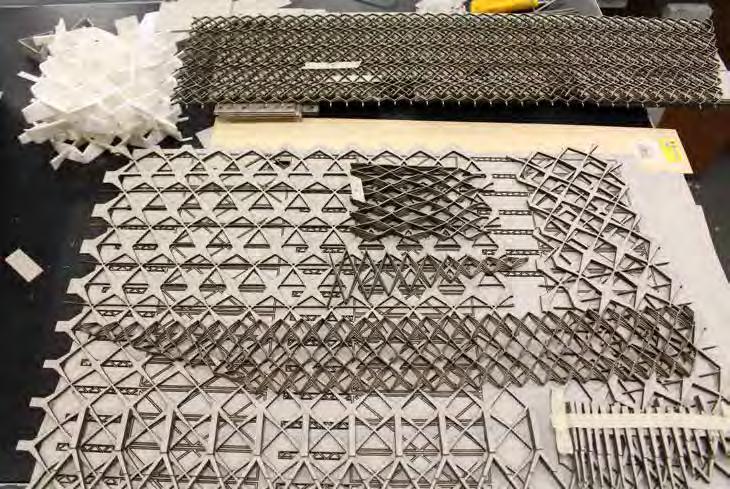

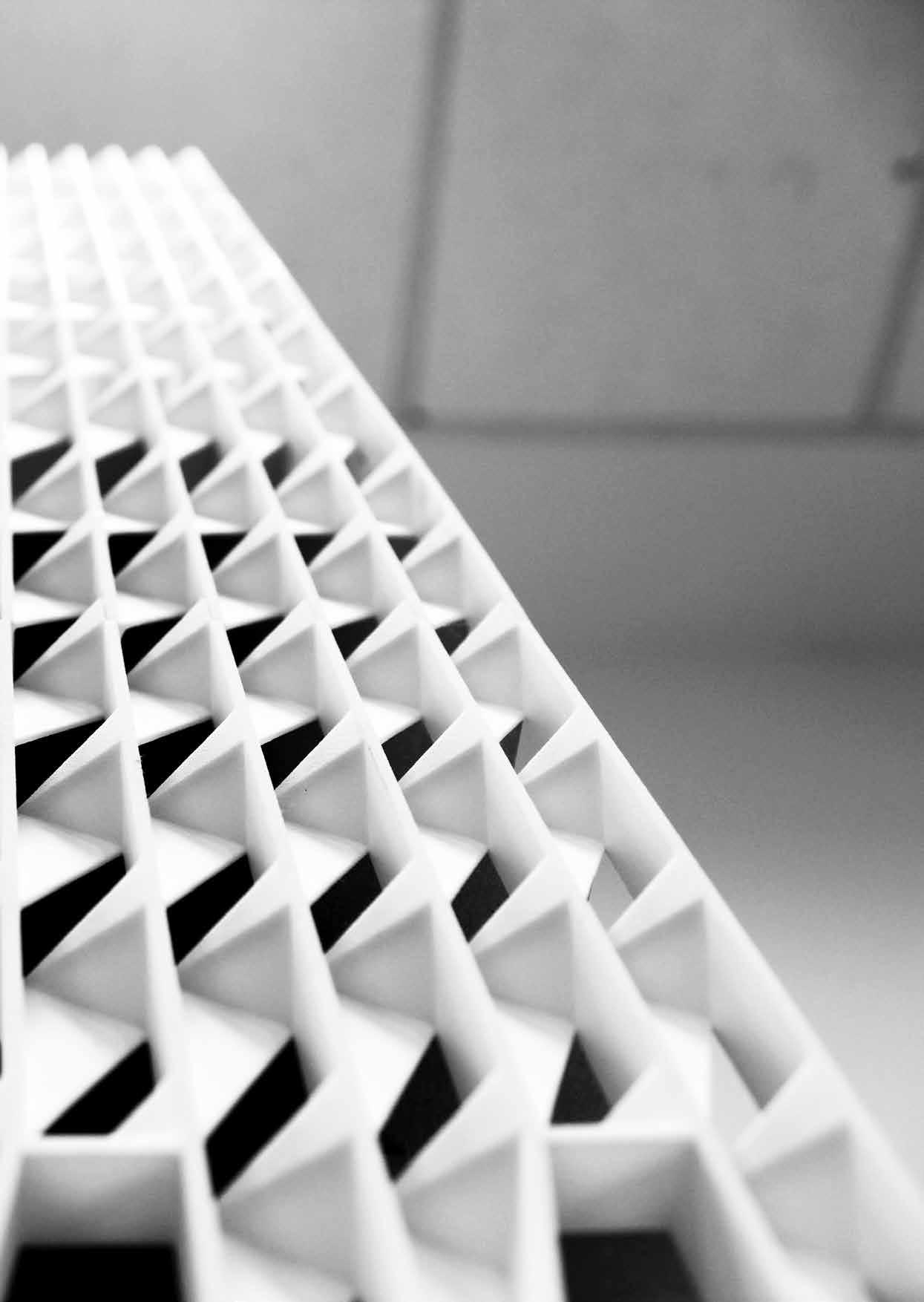

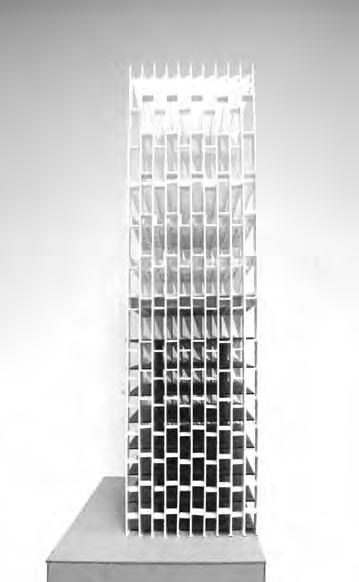

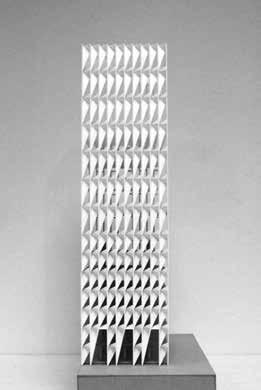

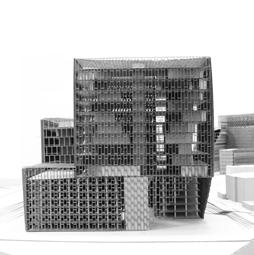

The elevation is composed of three main envelope: the ‘outer’, the ‘inner’ and the ‘non-structural’. The ‘outer’ is made up of alternating rows of light shelves and tables to allow in more diffused light and keep out more direct sunlight. The ‘inner’ is composed of triangular folds that act as sunshades, keeps the rain out and directs the view downwards. The ‘non-structural’ envelopes sport a discontinuous vertical element segmented by rows of light shelves. The depth of each envelope is calibrated by their positions on the inside-outside and east-west direction. Different as they may seem to be, the three elevations are read as a unified whole characterized by their vertical elements, proportions and materiality.

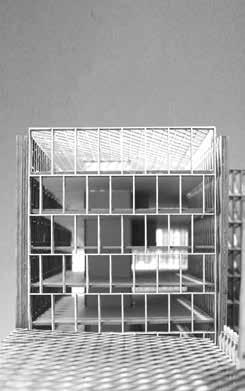

The new masses sitting lightly atop the existing Block 47 and 51 buildings are supported by the Structurally-Insulated-Panel (SIP) elevation that drapes over and hugs tightly around the existing building. The upper floors are supported by “waffle slabs” supported on both ends, like a series of tables stacked perfectly on each other.

On underbelly of the “waffle slabs” are a series of catenary vaults that taper out to a flat surface from the outer to the inner elevation. They act both to provide lateral support and to diffused the light gently into the inner spaces. The incline of the vaults become progressively steep from the highest to the lowest floor in response to the varying angle of incidence of sunlight.

The SIP facade and waffle slab enables the creation of column free upper floor spaces. These floor plates are dissected into three thermal zones, namely the A/C zone; transition zone; and Hybrid Zone (made up of chilled ceiling panels and floor slabs, dehumidifiers and mechanical fans) The AC zones are located on the eastern corners of each block to reduce energy wastage from increased thermal load of the western sun, while the western-most and ‘hottest’ corner of the building lies a 6-storey pyramidal-void behind the ‘outer’ facade to decrease thermal load and allow for the stack effect. The AC zones are separated from the hybrid zones by the transition zones to help deal with condensation. The remaining floor area is thermally controlled by naturally ventilation with the aid of the chilled ceiling panels and floor slabs to absorb heat from machinery and human processes and mechanical fans to aid ventilation.

Images (upper) fromlefttoright: roof space; lighting effect of envelopes on interior spaces.

Images (lower) fromlefttoright:‘inner’ envelope; ‘outer’ envelope; deatiled model showing new additions in white and existing building in grey; ‘non-structural’ envelope.

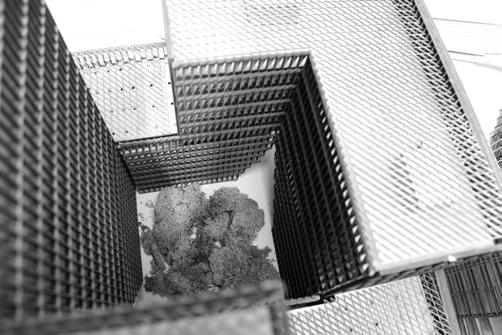

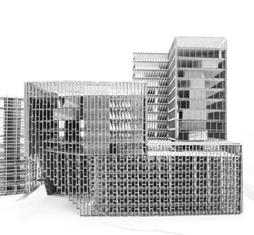

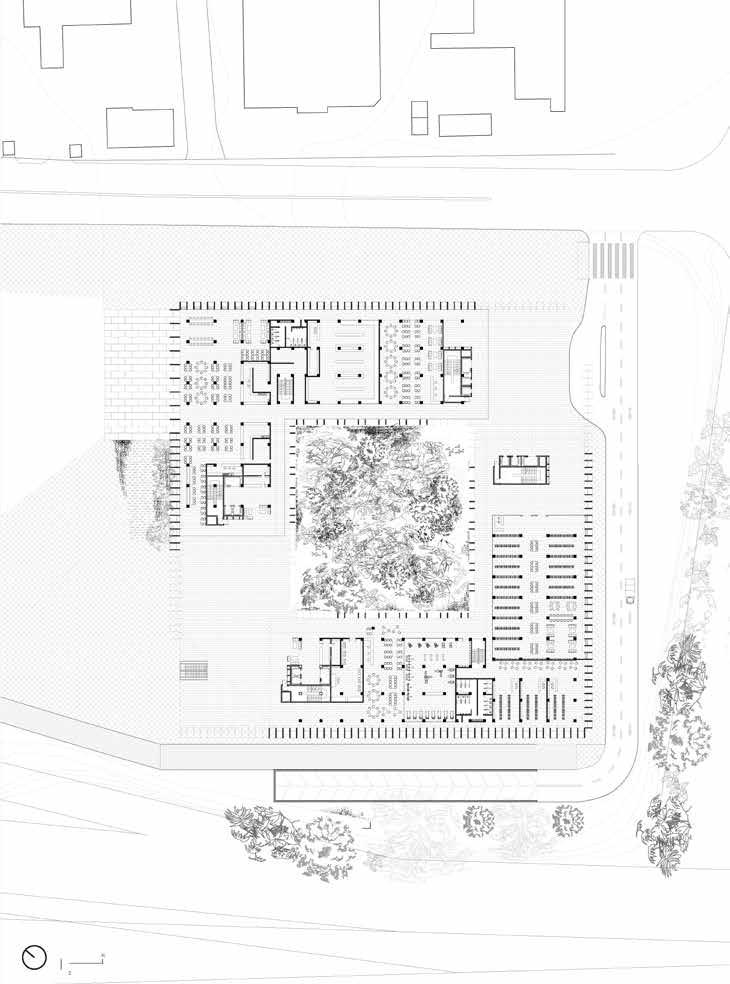

The main massing strategy of the project is to emphasize and enhance the spatial quality of the implied courtyard by completing the loop of the two existing L-shaped buildings. The overall building height is also increased to meet the required GFA whilst increasing the degree of enclosure of the courtyard to create a more intimate space that houses a hidden oasis of jungle amidst the industrial complex. Thus, the addition of two more L-blocks above the existing structures results in the creation of two massive urban gateways on opposite corners of the site oriented in an eastwest direction. This gesture welcome visitors into the jungle within as they enter the complex on either sides.

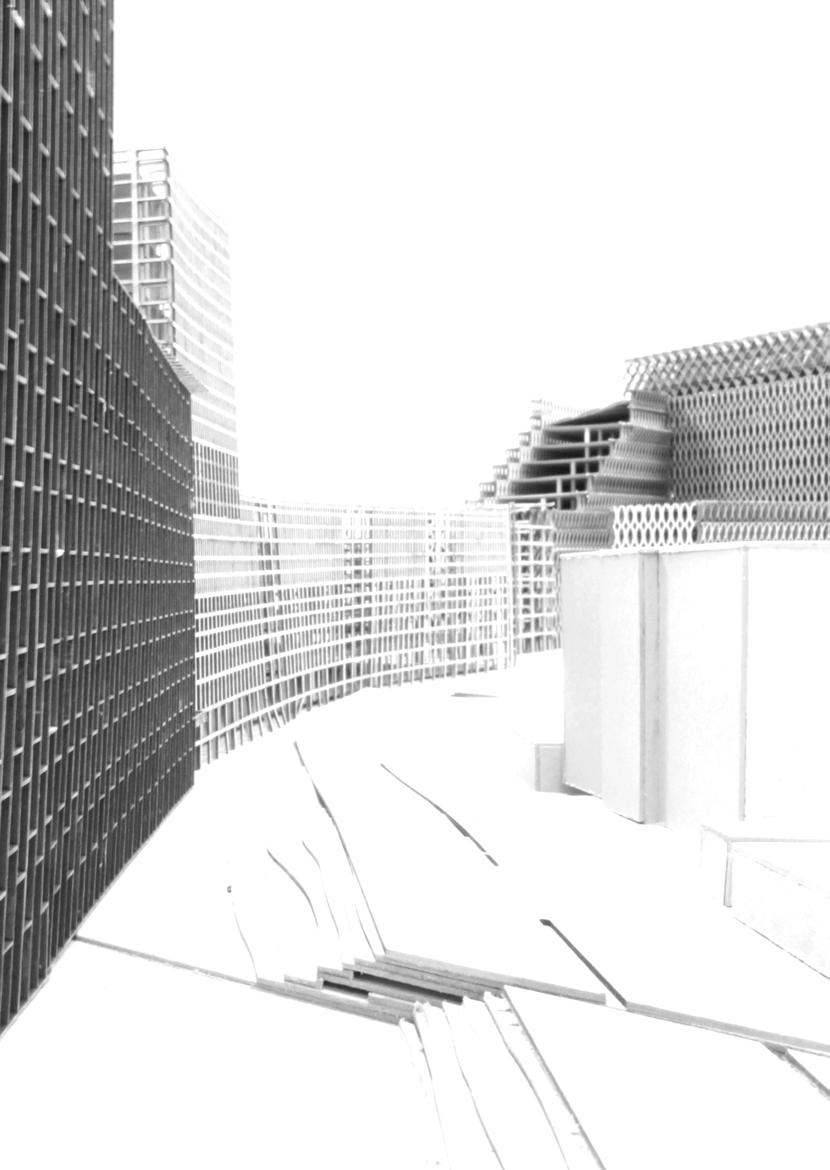

On the western corner, pedestrians approach the site from Kent Ridge MRT via an underpass and escalate to the ground level into an urban vista flanked by the two buildings on each side. The height of the upper western block is made to match that of the adjacent building in plot 2 to create an unbiased and balanced vista. On the opposite corner, the vehicular entrance leads to either the other parts of the industrial estate or to the underground carpark and loading bay underneath. The foyer of the complex sits vertically below the eastern upper block that rises up to 90 meters, acting as the other anchor point of the entire site to match the building height of Fusionopolis. Thus this completes the parabolic profile of the street front that lines the perimeter along Ayer Rajah Crescent.

Several alterations to the facade grid pattern at the ground floor were made in order to support a more permeable ground floor program that flows more seamlessly. At the two urban gateways, additional modules are added in a diagonal manner in order to provide better structural support of the cantilevered span above whilst framing the view of the lush jungle within. The perimeter of the main courtyard space is wrapped around by a 7-storey high volume, bounded by the internal facade. Rhythmic openings are punctured along the ground floor of the internal facades so as to create a loose and more porous boundary between the corridor and the courtyard space. Depending on program, these corridor space may also be a buffer zone where internal retail programs such as cafes can spill out to. Due to its surrounding context (consisting of mostly roads), the external facade is generally less porous except for the northwest facade where instead of touching the ground, it folds up to form a canopy that provides a sheltered connection into the adjacent building at plot 2, as part of the overall masterplan to connect pedestrians from one courtyard to another on the ground floor.

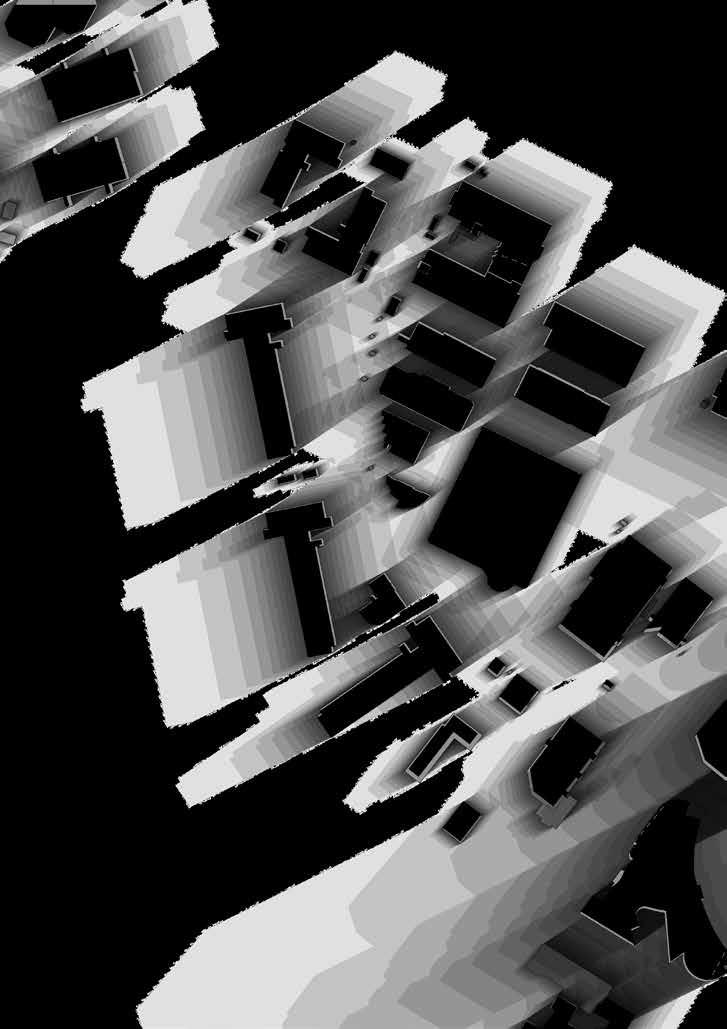

floorlayers;Typical“waffleslab”; Newmassing;Solarinsolation;existingbuildingstructure;sitecontext; Windanalysis)