DESIGN STUDIO

ERIK G L'HEUREUX ASSISTANT PROFESSOR

ALEX LEHNERER ASSISTANT PROFESSOR

JOERG REKITKKE ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR

DESIGN STUDIO

ERIK G L'HEUREUX ASSISTANT PROFESSOR

ALEX LEHNERER ASSISTANT PROFESSOR

JOERG REKITKKE ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR

AR4102, AY 2012/2013

M.ARCH 1, SEMESTER 2

CLARISSE FU

KIAN TIONG CHUA

LI LING GAN

MIN SUB LEE

PATRICIA CHIA

STEFAN LANDOY

TERENCE TANG

VICTORIA THONG

WEN HU

YIXI CHUA

YINGZI FU

A STUDIO COLLABORATION BETWEEN THE NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE AND THE ETH ZURICH FUTURE CITIES LABORATORY

NUS / ETH Spring Studio 2013

AR 4102

One day in late October 2013, Erik L’Heureux, Joerg Rekittke and I met at the campus Starbucks in order to discuss one important question: is there anything such as Singaporean Architecture? We looked up from our table to the newly erected University Town and the only answer we could immediately give was, “This isn’t it for sure—or if it was, we could not be less interested!”

For minutes, we remained silent and thought it might be a good idea to change the subject to something more joyful. At least the coffee tasted okay.

But then one of us mentioned that he recently passed by the Queenstown Bowling Alley. It is out of use, half derelict and moldy—but still fantastic!

–Oh, and there is the old pink-yellow-blue Bukit Timah Shopping Centre!

–Or People’s Park Complex in Chinatown…

–And yes, have you taken a closer look at the stunning Jurong East Town Hall with its digital clock tower? Amazing!

–Or the bowl of the old National Stadium?

–[Silence.] Sorry, they tore that down before I came here…

–But you’ve been to see Old School before it was closed to the public. You must have… !

–Hmm … missed that one, too.

There was a critical moment in Singapore’s history when the emerging nation’s architects and intellectuals envisioned ambitious approaches for the future of their city. The perception of a tropical city was infused with different cultural and ideological tendencies and led to a formal language that was sought by the architects to account for the people as well as the tropical environment. The ideologies were formulated and the forms of representation were strong and deliberate. The ambitions were bold and full of promise, however, they soon were not able to satisfy the demands of the zeitgeist and later became peculiar misfits in Singapore’s grand modernization program. Today, we find traces of this era scattered throughout the city of Singapore, most of these artifacts are now waiting to be replaced by more potent structures. These traces hold promise for imagining Singapore’s future architectural ambitions.

We will look at this previous era from an architectural point of view by analyzing these early incarnations of the contemporary “Garden City” with the tools of architectural practice – not through the nostalgia of lost memories, rather we will utilize our architectural expertise to extract the very essence of these buildings, transforming and projecting them into a concept of a tropical future.

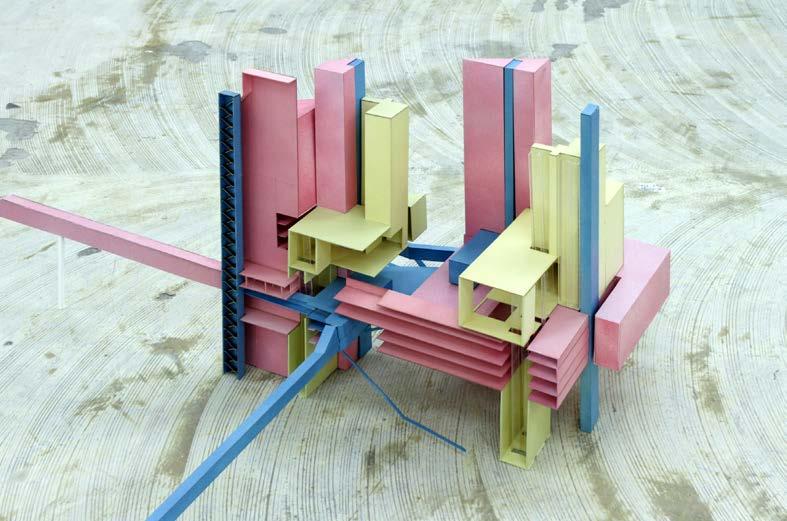

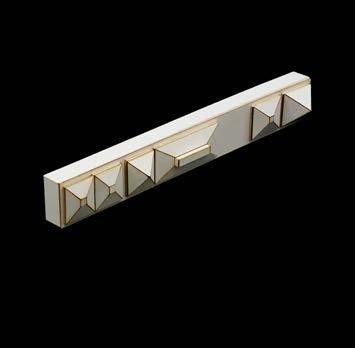

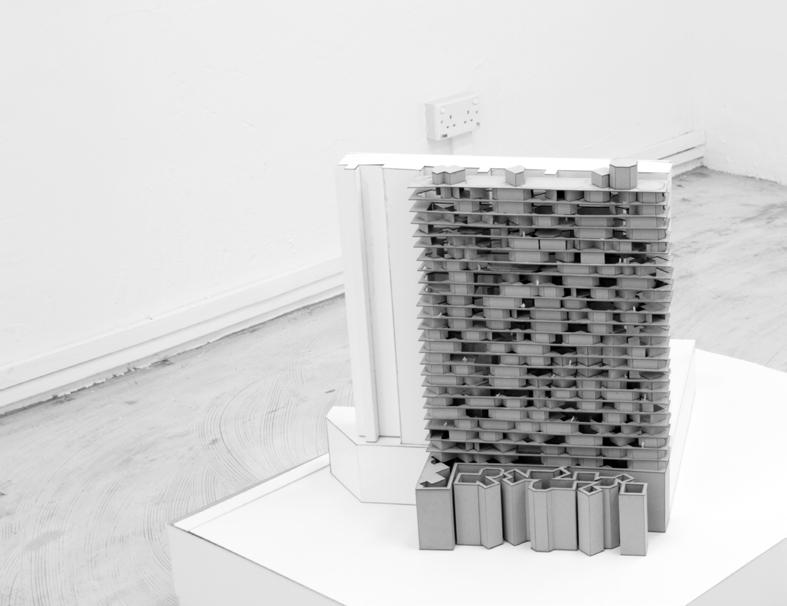

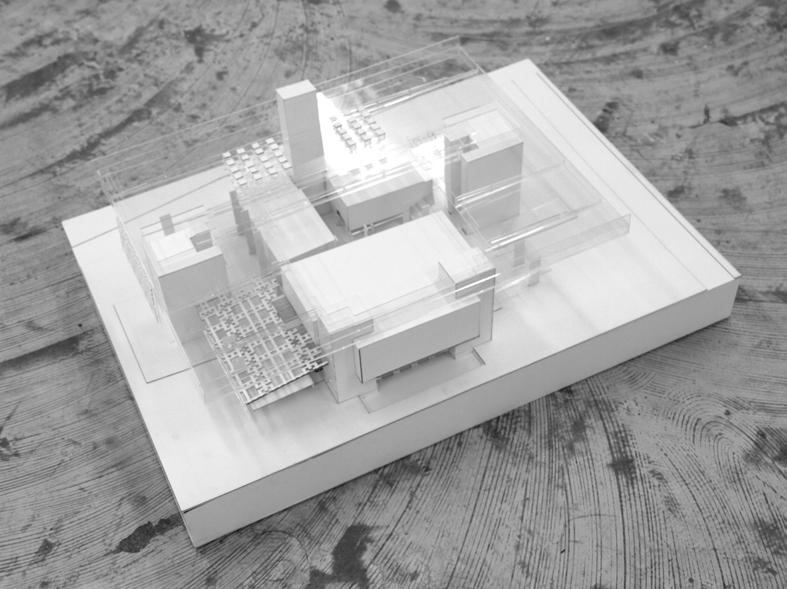

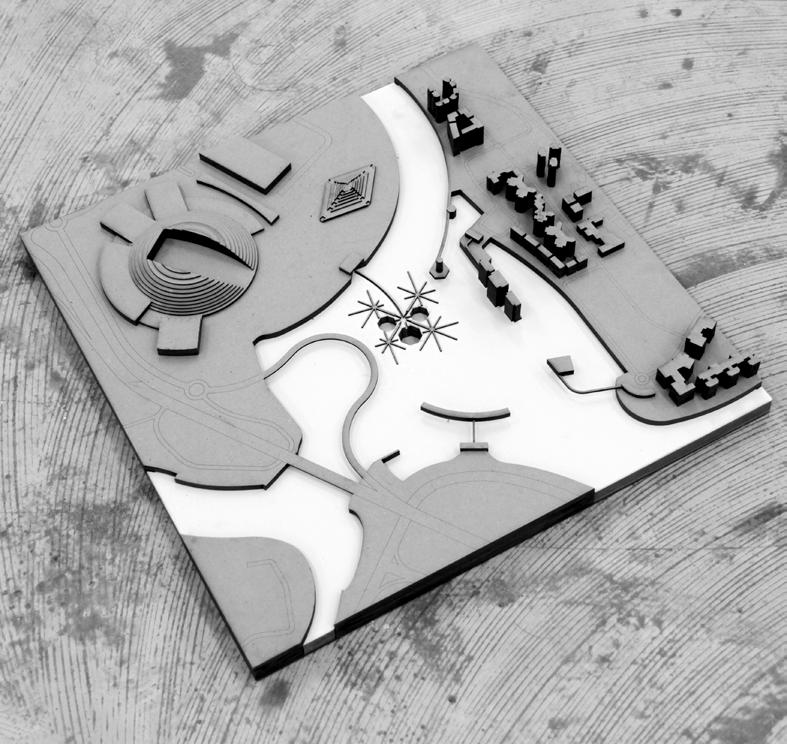

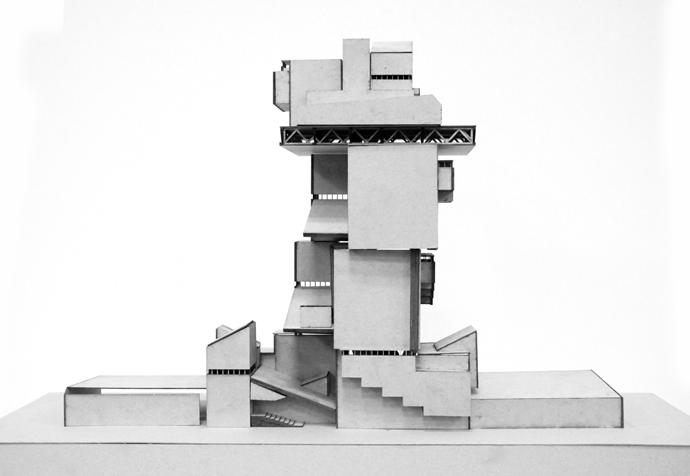

The Singapore Tropicana Studio is a celebration of the tropical city and its inherent atmosphere. Between the hot and the wet, the ambitious and the sensitive, the permeable and the sealed, the cultivated and the wild, each student will be assigned a piece of architecture and infrastucture located in the city that will inform his/her subsequent work. In the first weeks we will conduct multiple tasks to set the foundation for the following individual design work. Preliminary work consists of building specific models based on research of the assigned buildings and finding an appropriate mode of representation for the architecture in the tropics today. Looking at the gestures of the buildings helps us to find answers to the question of how the building as formal object contributes to the urban fabric, the surrounding atmosphere, and cultural milieu. By reconsidering eccentric features of the architectures through models we will discuss detail and identity. Other important properties in architecture such as formal operations of addition and subtraction, inversion and exaggeration, the ideas of concept and context, as well as how architecture impacts the city and urbanity will be introduced and thematized throughout the whole studio.

6 weeks will be focused for the design of a proposal for a new tropical building. In the last weeks the students’ individual work will be consolidated in an urban model for the future city. At the same time students will be curating the preceding output for the final review.

The students applying to the studio have the chance to be the first in a novel collaboration between Professor Erik L’Heureux from the Department of Architecture at NUS and Alexander Lehnerer’s Chair of Architecture and Urban Design at Future Cities Laboratory from ETH Zurich. The studio will also benefit from having two modes of lectures and critiques: Weekly presentation critics held by Erik L’Heureux with additional table critiques held by Lehnerer and his staff will be accompanied by and participated by Joerg Rekittke from the Department of Landscape Architecture at NUS.

The research/design work will be informed by lectures given by architects, artists and photographer on specific topics relating to the tropical city. We will leave the studio spaces regularly to visit practicing architectural offices in Singapore in order to get a glimpse of how other designers in our field conceive of a future for tropical Singapore. At the newly opened model workshop facilities on Create Campus the students will be engaging extensively in model making – one of the most important tools in architectural representation. By the end of the semester there will be a public exhibition of the student’s work at a location that is to be unveiled upon the beginning of the studio.

Suddenly a quote from Dave Hickey came up about what to do if the contemporary seems nothing else than bland and dull: “… if everything sucks, I am going to go back to the moment right before everything started sucking, and try to find a new way out of that.” This was to be our task. We needed to go back to these buildings—these artifacts from a time when unique architectural specificity tried to express itself and the context of the young nation of Singapore.

Could we use Singapore’s recent architectural history projectively? We are architects, maybe genealogists, but not historians. Nevertheless, our amateurish knowledge about Singapore’s past was sufficient enough to realize that searching for an already well-defined historical era, from which all of our favorite buildings originated, was going to be in vain.

So what if we invented a new one and inserted it into Singapore’s actual past? Yes, and we’ll call it Singapore Tropicana. We finished our coffee and didn’t look back. The idea for a joint studio between the NUS Department of Architecture and the ETH Future Cities Laboratory was born.

Later on, Tay Keng Soon inquired about the name Singapore Tropicana. He remembered it as the name of a topless dance club in the 1980s somewhere close to Orchard Road …

Professors: Erik L’Heureux, Alexander Lehnerer, Jörg Rekittke Assistants: Jared Macken, Lorenzo Stieger

Professors: Erik L’Heureux, Alexander Lehnerer, Jörg Rekittke Assistants: Jared Macken, Lorenzo Stieger

Perceptions of a Tropical City

NUS/ETH Design Research Studio Spring 2013 AR 4102

Professors: Erik L’Hereux Alex Lehnerer Joerg Rekitkke

Assistants: Lorenzo Stieger Jared Macken

Fu

Tiong Chua

Li Ling Gan

Min Sub Lee

Patricia Chia

Stefan Landoy

Terence Tang

Victoria Thong

Wen Hu

Yi Xi Chua

Yingzi Fu

Input Lectures:

Jin Quek Photographer, Singapore

Josh Comaroff & Ker-Shing Ong Architects, Singapore

Singapore Tropicana* describes the zeitgeist of the Singaporean nation-state from its full internal selfgovernance in 1959 to 1976, when the SPUR magazine was discontinued. In the context of these critical early years, Singapore Tropicana refers to the actions and attitudes exerted by exclusively local characters, for a collective national agenda, and made manifest in symbols, architecture, events and social behavior during this era.

Singapore Tropicana realizes the deliberate intent of local ambition to reconcile notions of progress and modernism derived from the West and the tropical realities and naiveties of a young nation on the fast track to success. Singapore Tropicana was short-lived, yet it is in architecture that we can identify the most tangible traces of its legacy in the city.

*The term “Tropicana” relates to two magical historical moments. The first one is the opening of the Tropicana Las Vegas hotel and casino in 1957. And the second one is the founding of Tropicana Products in Florida in 1947, a company specialized in the production of orange juice. Each of them helped to squeeze the notion of the “tropical” into a lifestyle product that no longer required the actual tropics as a context. The essence of the tropics becomes transferable and even flourishes at a relative humidity well below 30%.

1958 A school of architecture is established at Singapore Polytechnic

1959 Singapore achieves full internal self-government.

The national flag and anthem of Singapore are officially adopted.

Lee Kuan Yew is appointed Singapore’s first prime minister.

1960 The Housing Development Board (HDB) replaces the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT).

1961 The Economic Development Board (EDB) is established to develop the Jurong industrialisation programme.

1963 Singapore, Malaya, Sabah and Sarawak merge to form the Federation of Malaysia.

First local architecture students graduate from Singapore Polytechnic

“ FOR ME, IT IS A MOMENT OF ANGUISH. ALL MY LIFE, MY WHOLE ADULT LIFE, I BELIEVED IN MERGER AND UNITY OF THE TWO TERRITORIES.”

1964 HDB introduces the “Home Ownership for the People Scheme” to help Singaporeans buy their own flats.

1965 Singapore separates from Malaysia and achieves independence.

The Singapore Planning & Urban Research Group (SPUR) publishes its first magazine.

1967 First phase of Jurong industrial estate completed.

Urban Renewal Department is set up under HDB. URA sales of sites programme is established.

1968 Jurong Town Corporation is formed.

The British announce they are pulling out of Singapore.

First land sale by URA is completed for a site in Kallang.

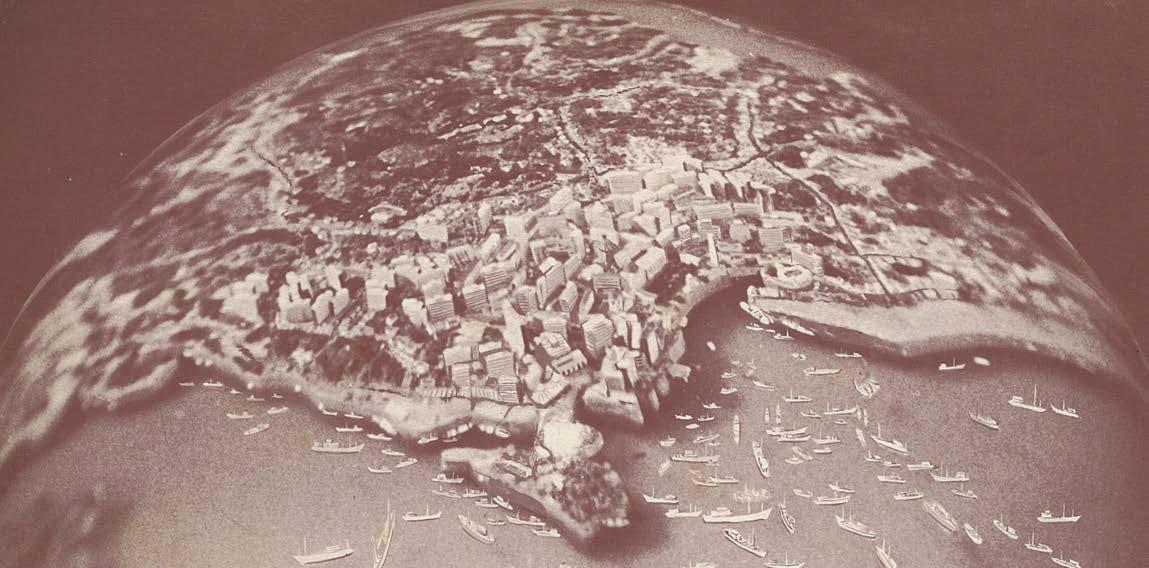

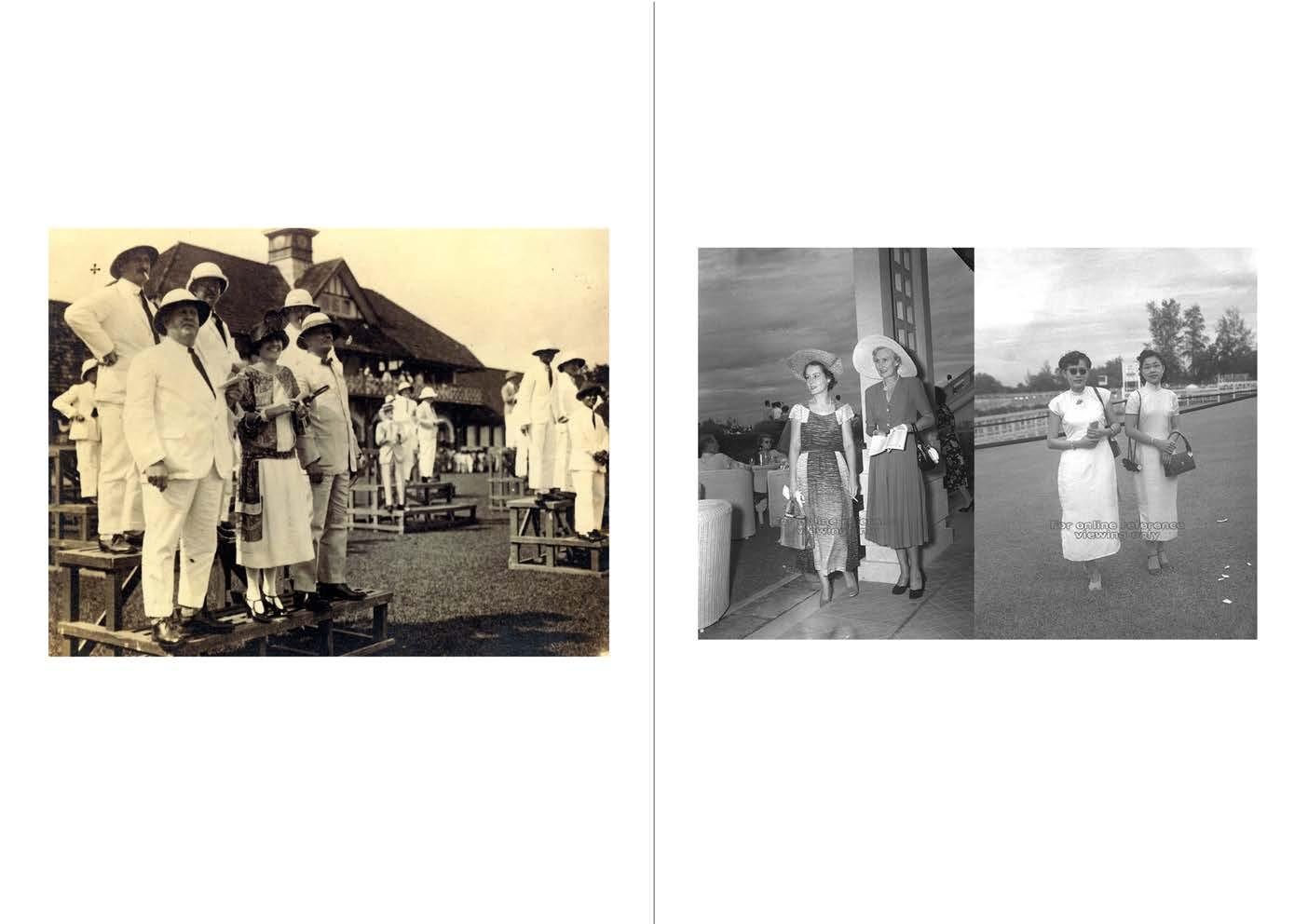

The young nation’s “Selbstbild” and “Weltbild.” Model/Collage vof Singapore, 1960s.

Source: Dick Wilson, East meets West – Singapore, 1971

1971 The British officially pull out of Singapore.

Singapore’s first Concept Plan is derived.

1972 Foreign Minister S. Rajaratnam announces that “Singapore is transforming itself into a new kind of city - a Global City.”

1973 Global oil crisis hits. The government steps up its public housing programme to stimulate private sector development.

1974 Urban Renewal Department is expanded into an independent statutory board under MND and becomes the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA). Housing and Urban Development Company (HUDC) is established to cater to the housing needs of the growing middle-class.

1976 SPUR is disbanded.

“ WE WERE MODERN PEOPLE, WE BELIEVED IN OURSELVES, WE BELIEVED IN THE CONCEPT OF FREE SPEECH, OPEN DISCOURSE. WE BELIEVED IN AN OPEN SOCIETY. OUR NAIVETÉ WAS TO BELIEVE IN AN OPEN SOCIETY WHEN THE SOCIETY WAS NOT OPEN AT ALL. AND SO OF COURSE WE RAN FOUL OF THE POWERS THAT BE AND A LOT OF US GOT HAMMERED FOR IT.” -SPUR

“Asian City of Tomorrow” from the first issue of SPUR, 1965

“ IT WAS CONSIDERED AN EXTRAORDINARY IMBECILITY TO PERMIT THE WEATHER TO HAVE ANY EFFECT ON THE SOCIAL MOVEMENTS OF THE PEOPLE … IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY, THEY PUT UP ONE UMBRELLA OVER ALL THE HEADS.”

-EDWARD BELLAMY, LOOKING BACKWARDS, 1881

Victoria Thong

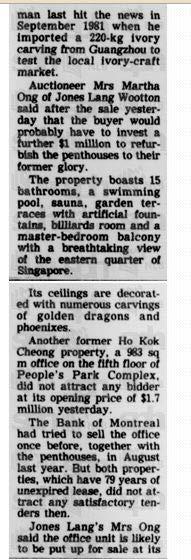

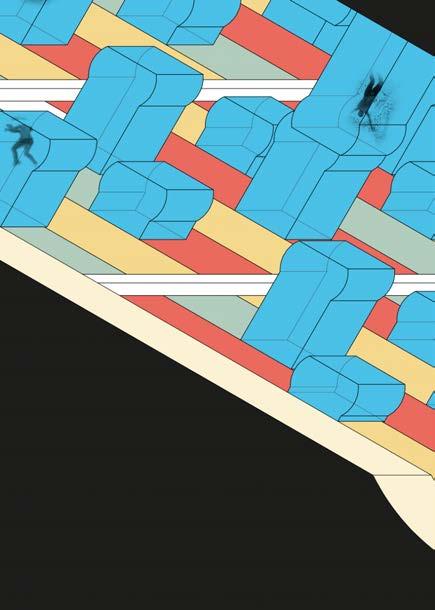

Completed in 1981 by Chee Soon Wah Architects, Bukit Timah Shopping Centre is a 22-storey fully air conditioned complex along Upper Bukit Timah Road. The podium (1978) consists of seven shopping floors, a Chinese emporium supermarket, the Gala Cinema and a seven storey car park while the two towers (1981) accommodate fourteen floors of residential units including a penthouse each on the top floor. Together with Beauty World Centre and Bukit Timah Plaza, Vukit Timah Shopping Centre flanks the main traffic artiery of the Upper Bukit Timah Road towards Johor, theming the area as a popular recreation and retail destination. Currently, the strata-titled management structure consists of small businesses such as maid agencies and construction companies, while the cinema has been converted into an auditorium now owned by a church and rented out as a multipurpose convention centre. The tower now consists of strictly office or commercial spaces, while the church office occupies the penthouse unit. While these programmatic changes occur on a small scale, the structure remains largely unchanged from its conception.

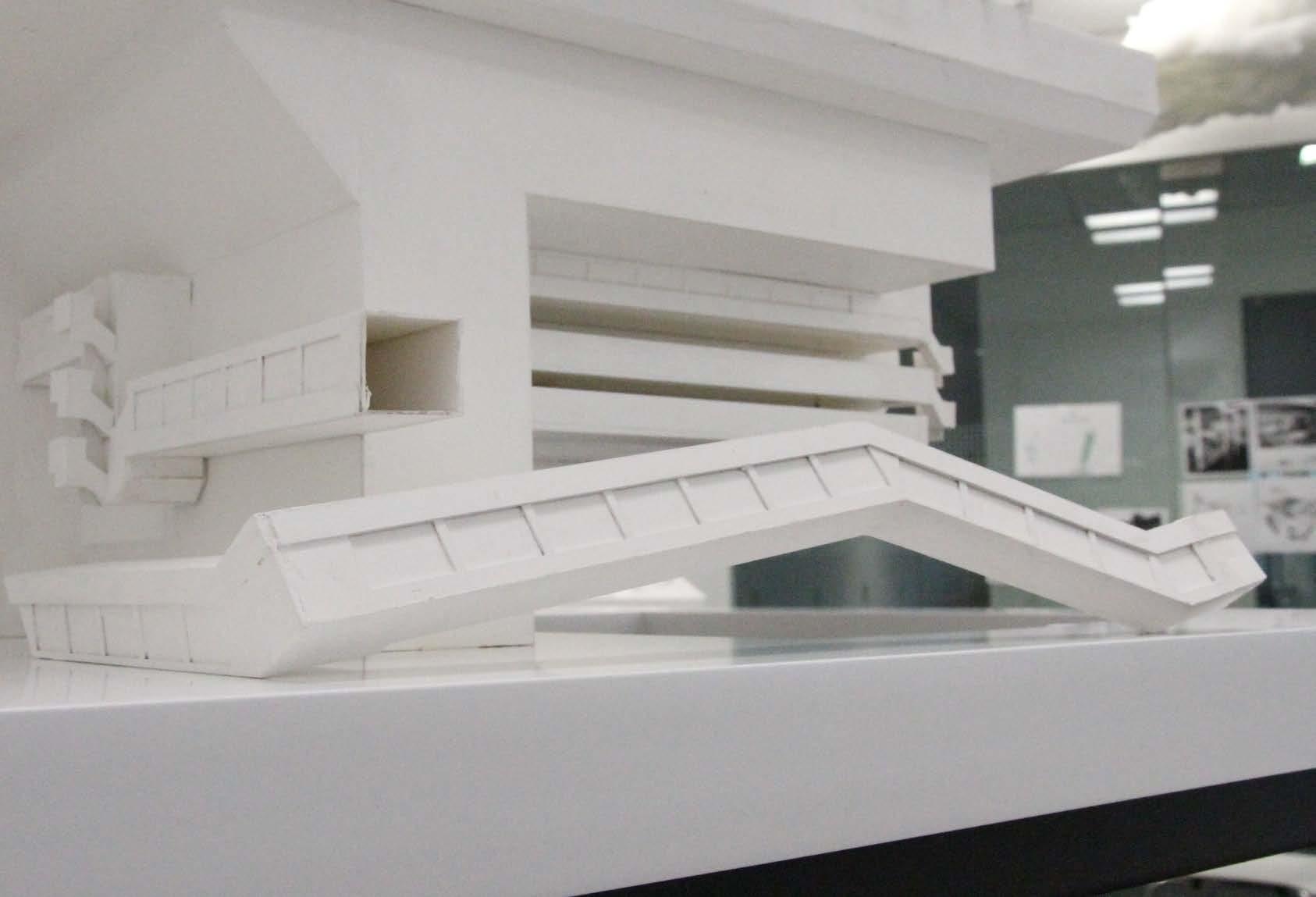

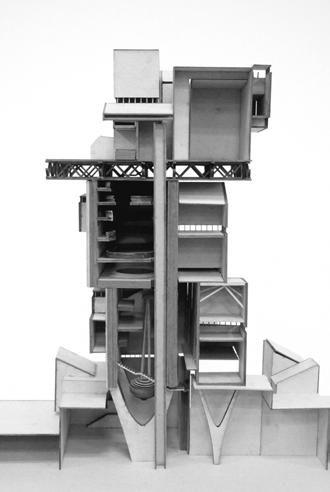

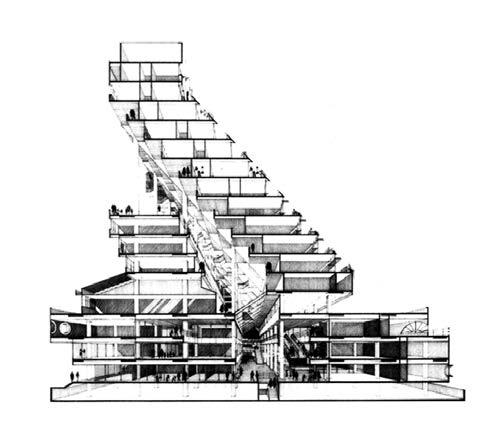

A floating city -- pedestrian walkways as armatures that support the ship-like complex

This project envisions a contemporary remaking of the high-rise, mixed-use megastructure ambition of the experimental typologies of 1970s Singapore Architecture. The proposal celebrates the constant circulation within the megastructure and futhermore, throughout the contemporary metropolis in which citizens are commuters that have come to “expect complete connectivity”. The carefully engineered condition of being perpetually inside extends with the extension of the limit of architecture via a a type of collective infrastructure endorsed as provisions by a patriarchal government.

&

The promise of future public housing

CLOCKWISE FROM ABOVE

PM Lee addressing the crowd at one of then recently built HDBs

Aerial view of the first HDB housing estate, Queenstown

HDB block in Queenstown: curvilinear block as a creative expression, beyond utilitarian rectilinear blocks

PEOPLE’S PARK COMPLEX

Wen Hu

1 Park Road

Architect: Design Partnership built in 1970; in use

“BUT WE THEORISED AND YOU PEOPLE ARE GETTING IT BUILT!”

–FUMIHIKO MAKI, WHO VISITED THE SITE DURING ITS CONSTRUCTION

“ AIR-CONDITIONING, THE MOST IMPORTANT INVENTION OF THE 20TH CENTURY.”

-LEE KUAN YEW

1970-1980

CLOCKWISE FROM OPPOSITE PUB building

Oandan Valley Condominium

Futura Condominum

Pearl Bank Apartments

Min Sub Lee

The Jurong Town Hall Building (1974) by Architects Team 3 resembled a battleship and even had its own periscope; a digital clock tower. Raymond Woo’s Singapore Science Centre (1977) was equally futuristic in its geometry and form. These two works were both located in the newly developed Jurong industrial area, which symbolised technology, progress and the nation’s hopes for the future.

numerous columns looks like sustaining ship on the sea.

Against the backdrop of the modern movement in architecture, we also see the use of modern materials and techniques being adapted to suit the unique tropicality of Singapore … successfully or otherwise. The Singapore Conference Hall featured a large roof that sheltered all its various components. The Jurong Town Hall building had windows set back into the facade and vertical fins serving as brise soleil. In all, the post-independence years of Singapore was the backdrop of an exciting period of time for Singaporean architecture. Local architects were fuelled largely by a sense of duty towards the building of a young nation, producing works of great importance to the people and to the nation.

“ IT IS NECESSARY DURING THE NEXT DECADE WHEN THE PACE OF PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT WILL BE UNPRECEDENTED IN THE WHOLE OF OUR HISTORY THAT WE CONSIDER WITH GREAT CARE, THE FUTURE OF THESE AND OTHER SIGNIFICANT FEATURES. WE ARE AT A CROSS-ROAD BETWEEN THE OLD AND THE NEW SINGAPORE AND THE PLANNING AND ENVIRONMENTAL DECISIONS WHICH WE MAKE TODAY MUST BE WITH VISION AND FORESIGHT, AS FUTURE GENERATIONS WILL JUDGE AS WE JUDGE OUR PRE-DECESSORS.” -SPUR

William S.W. Lim (Architect)

Tay Kheng Soon (Architect)

Chew Weng Kwong (Urban Redevelopment Authority)

Charles Ho (Van Sitteren Architects)

Tan Jake Hooi (Chief Planner of Singapore)

Howard Quan

Ho Pak Toe (Director, Public Works Department)

Wee Chwee Heng

Chan Sau Yan (Architect)

C. J. Shaw (Quantity Surveyor)

Robert Gamer (Political Scientist, Singapore University)

Chu See Teng (executive, Shell operations)

Koh Seow Tee (Economist, Singapore University)

Rudlophe de Koninck (Geographer, Singapore University)

Lau Yu Dong (Engineer)

Tim Manning (Lawyer)

Howard Quan (Town Planner)

George Sicular (Lawyer, Economist)

Nalla Tan (Department of Social Medicine, Singapore University)

Amina Tyabji (Economist, Singapore University)

Koichi Nagashima (Architecture, Singapore University)

George Thompson (Director of Political Studies Centre, brought in to “diffuse political backlash”)

Peter Weldon (Sociologist)

Ian Buchanan

Donald Blake

Lim Leong Geok

Eric Cromby (Quantity Surveyor)

Mrs. Ann Wee

Christopher Hooi

Choy Weng Yan

Tan Cheng Siong (Architect)

Agnes Fung (Literature major)

Donald Moore (Singapore’s first musical impresario and art entrepreneur)

Yueng Yue-Man (Geographer)

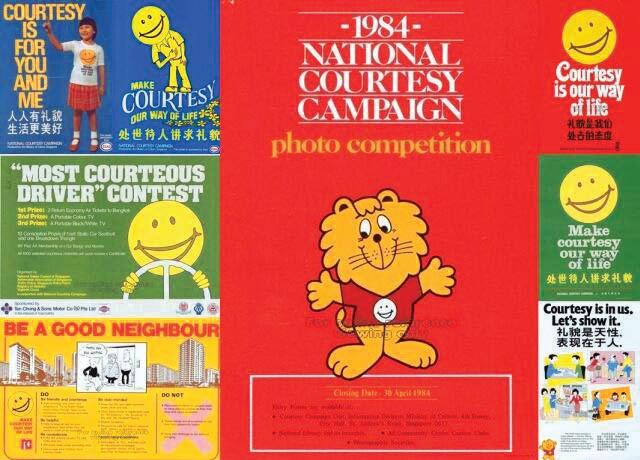

As a newly independent nation, Singapore embarked on a campaign bliitz, launching 200 campaigns from 1970-1990 aimed at carefully curating an appropriate image of Singapore to present to the world; Singapore as a modern, efficient and beautiful city in which to live, work and play. Today, we recognise these campaigns as familiar icons documenting the top-down approach of promoting a new urban vision for a newly independent Singapore.

“National Courtesy Campaign” (1979-2001)

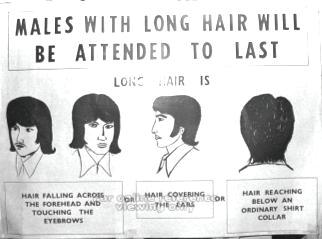

“Campaign Against Long Unkempt Hair Amongst Males”(1972)

“Speak Good English Campaign” (2000)

These were introduced to encourage the people to conform to a homogenously modern and civil society befitting of a global city. The social campaigns of the 70s and 80s were line with the national agenda to market the city-state.

For example, the instrumentalist use of the National Courtesy Campaign, in its first incarnation initiated by the Singapore Tourism Promotion Board in June 1979, was focused on extending graciousness to tourists and foreigners. Front of house hospitality staff, taxi drivers and civil servants were educated through training films and roleplaying scenarious of courtesous and discourteous acts. The idea of instilling civic mindedness were undeniably loaded with economic rationales for the engineering of a harmonious and productive society.

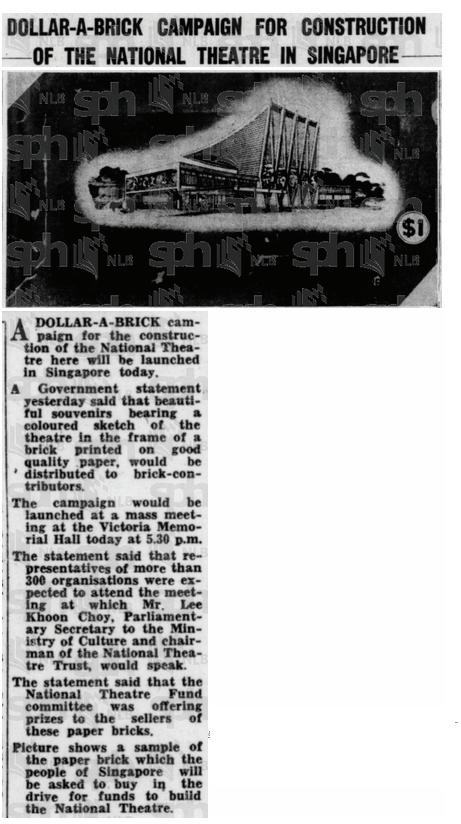

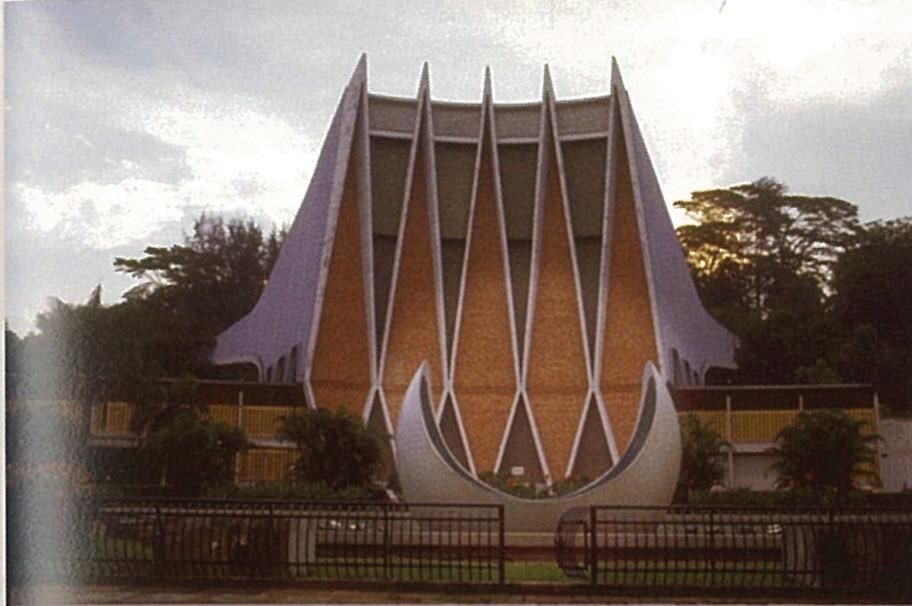

These campaigns also served to compliment the government’s nation-building agenda that was occuring on a larger scalethrough the visible forms of the built city. The National Theatre, designed by local architect Alfred Wong, was built in 1963 with funds donated not only by the government but also by the public through the “a-dollar-a-brick” campaign made on the radio with song dedications. Through these campaigns, the people became invested in the nation building narrative which was now made visible in architectural forms. While the National Theatre was demolished in 1986, we continue to observe traces of these campaigns today in the city.

Li Ling Gan

The Singapore Conference Hall and Trade Union House (SCH) was the first modern building constructed along Shenton Way. Designed by the Malayan Archtects Co-partnership (MAC), this proposal was selected from a nationwide open competition held in 1961. It captured the mood and aspirations of a young nation, transitioning from colonial to modern Singapore.

Completed in 1965, this $4 million building (estimated to be $12.5 million as of 2011) was built to fulfill an electoral promise by the People’s Action Party as a venue to unify trade unions and to host international conferences and exhibitions after self-governance, SCH played a symbolic role in Singapore’s post-independence industralization and globalization and it “represented a moment in history, of the making of a new state.

The assimilation of “tropical architecture” into the aesthetics of the modern movement is an expression of the democratic aspirations of a progressive nation as it is an attempt to differentiate itself from its colonial predecessor. Exemplified in the SCH, the technical aspects of building construction and environmental control were ambitiously showcased via the overhanging eaves of the large butterfly roof and the shaded glazed curtain wall beneath it, large atrium spaces and open terraces.

“ THE THEATRE PROVIDES A GOOD EXAMPLE OF HOW THE SUCCESS OF ANY EFFORT DEPENDS ULTIMATELY ON THE CO-OPERATION AND DEDICATION OF PEOPLE FROM ALL WALKS OF LIFE.”

-S RAJARATNAM, THEN MINISTER FOR CULTURE, 1964

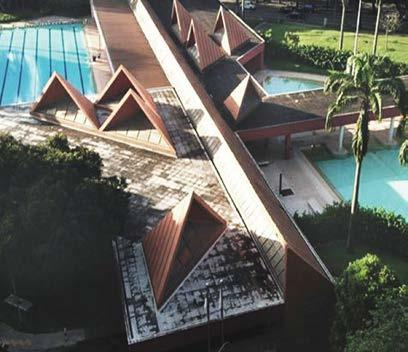

CLOCKWISE FROM ABOVE

Clarke Quay umbrellas

Pitched roof, Church of the Blessed Sacrament

Ang Mo Kio swimming complex, triangular roof skylights

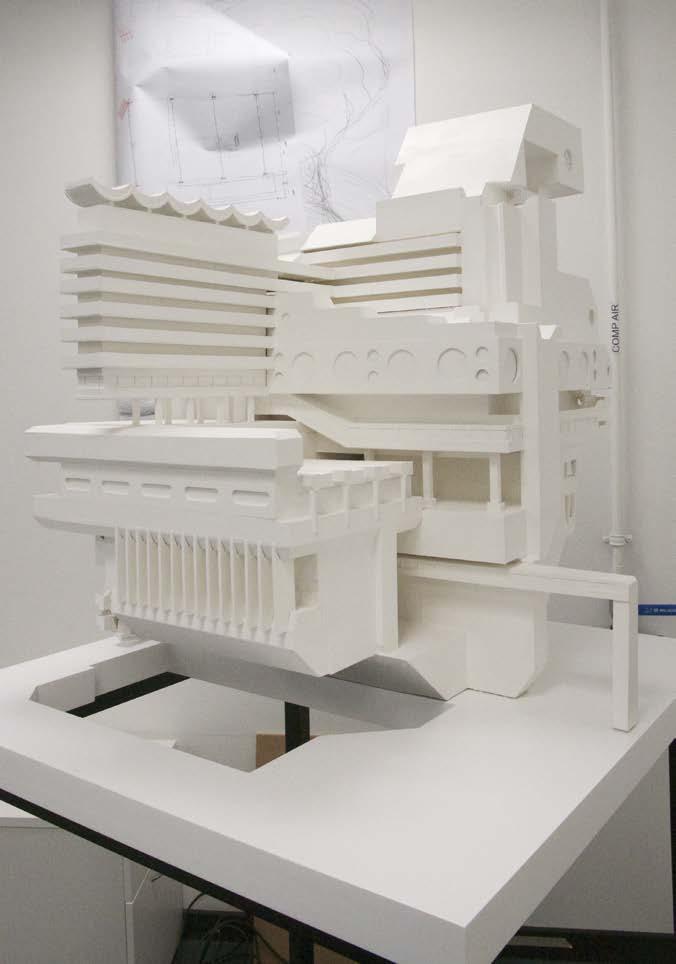

Taking the singapore conference hall as precedent, the use of the large canopy roof the ambition of the architects to create a language for tropical architecture. The emphasis of the project lies in redeveloping the use of the roof by incorporating current technology such as automated roof for extra ventilation and skylight into the central atrium and the creation of roof gardens Claddings were developed so as to allow natural ventilation spaces where airconditioning is not required.

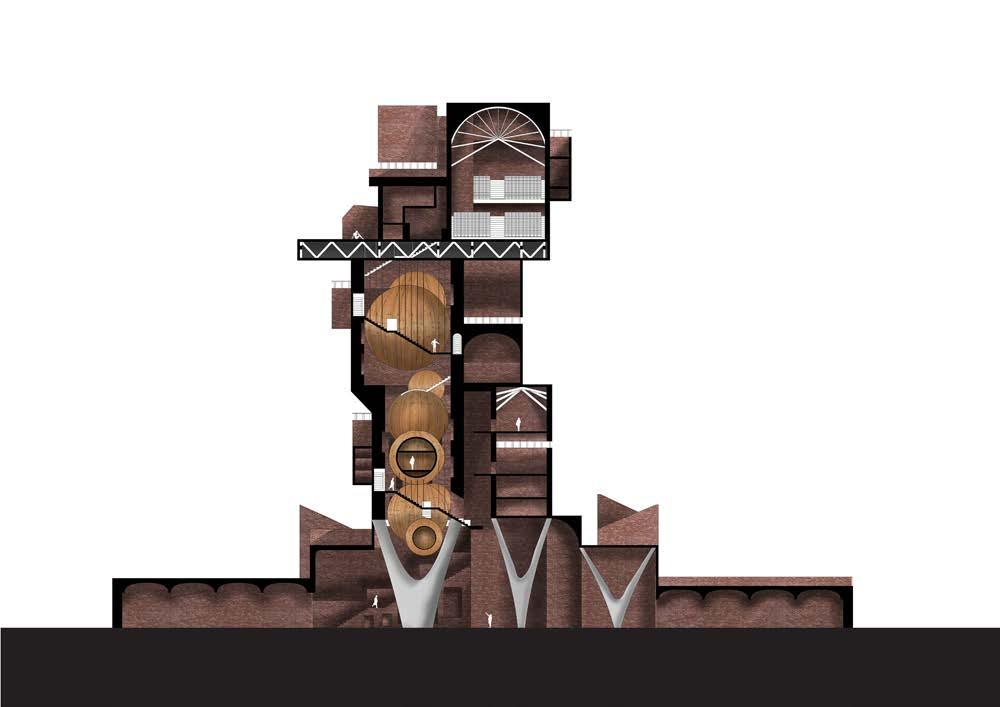

A structure for the people -- honest and functional expression through supporting columns and pilotis

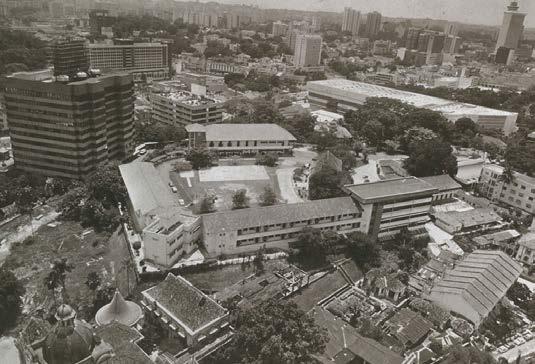

Kian Tiong Chua

(formerly Methodist Girls School, MGS)

Pan Malaysian Group Architects

11 Mount Sophia built in 1928; boarded up

Ascending the school’s one hundred steps every day was a precarious but worthwhile journey for MGS students. From the Old School’s hilltop site, they had grand views of mansions like Eu Villa. Its high elevation isolated it from the fast-growing city, giving it an ethereal presence.

Terence Tang

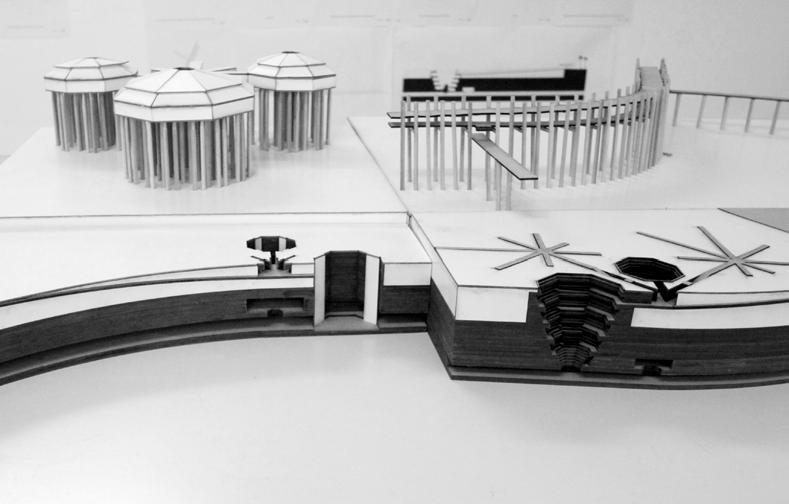

In 2012, the Oasis Building was demolished to make way for a watersports facility as part of the new Singapore Sports Hub, and along with its demise, a slice of Singapore history was lost forever. The Oasis had been an iconic sight on the bank of the Kallang river since it was opened in 1969 as the Oasis Theatre Restaurant, Cabaret and Nightclub. Comprising three octagonal, pod-like structures built upon concrete stilts and extending some 100 metres out into the Kallang Basin, the Oasis was a popular nightspot and icon for recreation for many years. More recently, it housed 3 restaurants and 2 bars which were frequently crowded with regular customers despite their relatively wayward location. Canoeists and other water sports enthusiasts who regularly plied the Kallang basin will also remember the Oasis as a prominent landmark in the area. The Oasis embodies Singapore tropicana for many reasons. Its unique programme made it a symbol of waterfront recreation while its very form reminds us of the “space-age” obsession that characterised many buildings in the 60s and 70s of Singapore tropicana. Alas, with its demolition, the iconic Oasis will now only exist in the memory of the older generation.

PEARL CENTRE

Charisse Fu

Architect: Completed:

include north point if drawing is

OPPOSITE Sentosa’s garden city

ABOVE a series of tree plantings by PM Lee: at Farrer Circus, 1963; at Marina Park, 1976; at Everton Park, 1981

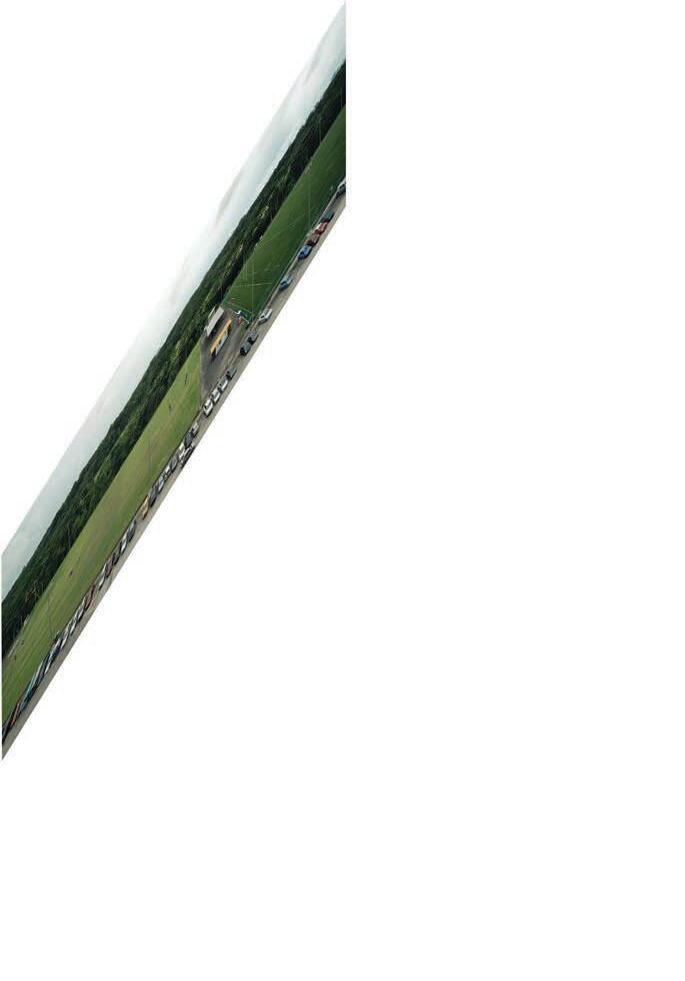

Yingzi Fu

200 Turf Club Road

Swan and Maclaren Architects

built 1981; in use

On race days, the roads around the club were packed with traffic. Thousands of people watched, shouted, cursed and cheered at the horses and their riders jockeying for position. The punters, mostly working-class men, usually went home empty-handed, leaving the betting slips they had clutched littered across the grounds.

The unexpected clearing -- manicured lawn in the tropics

The unexpected clearing -- manicured lawn in the tropics

THE ARTIFICIAL LANDSCAPE

The road to Changi Airport

Supertrees, Gardens by the Bay Indoor garden, Changi Airport

“ A BLIGHTED URBAN JUNGLE DESTROYS THE HUMAN SPIRIT.”

-LEE KUAN YEW, AT THE OPENING OF THE NATIONAL ORCHID GARDEN, 1995

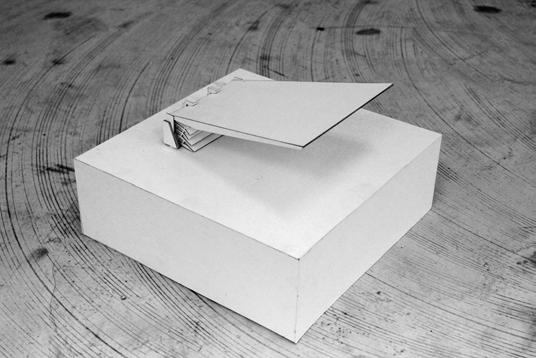

LEFT TO RIGHT The beginning of a nation; national celebration of one year of indepedence in the Padang, 1966

An orderly formation of the parade, a transformation as a result of the governance Chaotic parade along the streets, intimately enthusing the crowd with national pride, 1968

The campaigns for public health shifted from focusing on basic healthcare issues such as personal hygiene and dental care to a new emphasis on sports and recreation to encourage Singaporeans to keep fit and enjoy a higher quality of life. Following the opening of the National Stadium in 1973, the 1976 master plan for sport facilities was intended to insert a collection of new sporting and recreational amenities into the city that would attract Singaporeans in each region of the island. Under this scheme, six indoor multipurpose stadiums, three football fields and seven swimming pools, seventy tennis courts, three athletic stadiums as well as all of HDB’s recreational amenities for the New Towns were built.

“ SPORT, WHEN ADAPTED TO THE SPECIFIC NEEDS AND ABILITIES OF THE INDIVIDUAL, IS A SOURCE OF HEALTH AND BALANCE AGAINST THE SEDENTARY URBAN LIFE.”

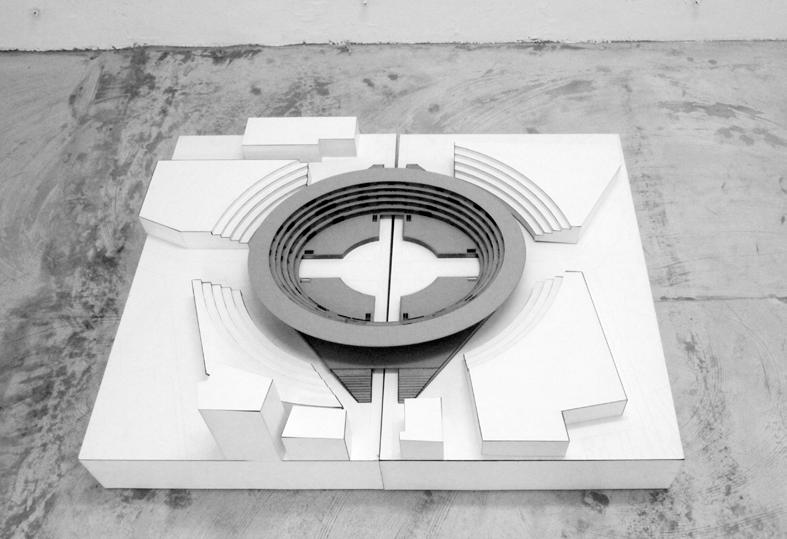

The Singapore National Stadium was the nation’s first full-capacity stadium. Conceived as a new symbol, it was intended to bond the multiracial people through sports and to place the newly independent state on the regional sporting map. Constructed from 1966 to 1973, using 300,000 bags of cement, 3,000,000 bricks and 4,500 tons of steel and timber, it was funded by the newly established Singapore Pools. The stadium holds 60,000 spectators on 58 tiers.

Sited on reclaimed land in Kallang, several other sporting facilities were also constructed at the same time: a netball, squash and tennis centre and a practice track. Eighteen times it was the venue for the annual National Parade, from 1976 to 2006. It was also the home to the national football team, hosting several memorable matches with neighbouring rivals. It was officially closed in 2007, but demolition first began in late 2010, ending in February 2011.

WHAT THE LEADER DOES, WE SHALL FOLLOW …

OPPOSITE Hosing down a street in Tanjong Pajar during the cleaning up of Chinatown, 1959

ABOVE Mopping the floor at Delta Circus Primary School during the ‘Use Your Hands’ campaign, 1976

KEEP SINGAPORE CLEAN, 1968-1990

OPPOSITE To prove that the river was clean, two ministers joined citizens in swimming across the river, 1984

ABOVE Yan Kit Swimming Pool

Patricia Chia

Yan Kit Swimming Complex was the second public swimming pool in Singapore, after Mount Emily Swimming Complex built in the 1930s, and was built pre-Singapore independence and self-governance by the City Council. Originally constructed as a filter tank for the Water Department, it was closed down during the Japanese Occupation and had its plant removed. It was then refitted and reopened in December 1949, named after Mr Look Yan Kit – a Canton-born dentist who came to Singapore in 1877 and was involved in the founding of the Kwong Wai Shiu Free Hospital in 1910.

The complex occupied 14, 859 square metres of land and sat on a former stretch of railway land along Yan Kit Road. It contained three pools, a single-storey clubhouse and three independent structures containing changing rooms and showers. There were diving platforms at one end of the string of pools, and a lifeguard watchtower-cum-slide between two of the pools.

The pool was extremely popular in its heyday. It was so crowded that there was only standing room and a two-hour limit had to be imposed on swimmers. Single gender and mixed gender bathing sessions were also enforced in the 1950s; on Tuesdays, the pool was opened only to females who were too shy to appear in bathing suits in front of men.

“ AS THE CITY POPULATION GOT REDISTRIBUTED INTO SELFSUFFICIENT SATELLITE NEW TOWNS, AS INCREASING NUMBER OF CONDOMINIUM WITH SPORT FACILITIES GOT DEVELOPED, AND AS SWIMMING LOST ITS INITIAL GLAMOUR AND NATION-BUILDING AGENDA, THE OLDEST PUBLIC POOLS, NOT GIVEN A CHANCE TO REINVENT THEMSELVES, FADED INTO OBSOLESCENCE.”

-KAR LIN, TAN. SINGAPORE ARCHITECT JOURNAL 234, “TROUBLED WATERS”

3. increase the overal height of the building and offset the functions.

increase

Plan of Queenstown Housing Estate, Singapore Improvement Trust, 1955

Source: National Archives of Singapore

Influenced by post-war Britain’s “New Town” movements, the “satellite town” emerged in Singapore in the 1950s as a solution to inadequate housing, and Queenstown was the first to be developed into one.

The satellite town was to be a decentralised node of self-contained amenities for residents to use. After completion, Queenstown featured these amenities and infrastructure:

28,400 dwelling units

police station

maternity and child health centre

first branch of national library

first neighbourhood shopping centre

first sports complex schools emporium

3 cinemas

nightclub-cum-restaurant

Queenstown Centre

Commonwealth Cooked Food Centre

places of worship: Queenstown

Baptist Church, True Way

Presbyterian Church, Faith Methodist Church, Masjid

Jamed Queenstown, Tiong Ghee

ABOVE Plan of Queenstown Housing Estate, Singapore Improvement Trust, 1955.

Source: National Archives of Singapore

fresh food market

bowling alley

Temple, Sri Muneeswaran Temple, Shuang Long Shan Wu Shu

Its success as a self-contained community provided precedent for other subsequent districts such as Toa Payoh and Ang Mo Kio.

OPPOSITE Dragon playground Van Cleef Aquarium

ABOVE publicity for the Singapore zoo: have breakfast with Ah Meng, the orangutan

Stefan Landoy

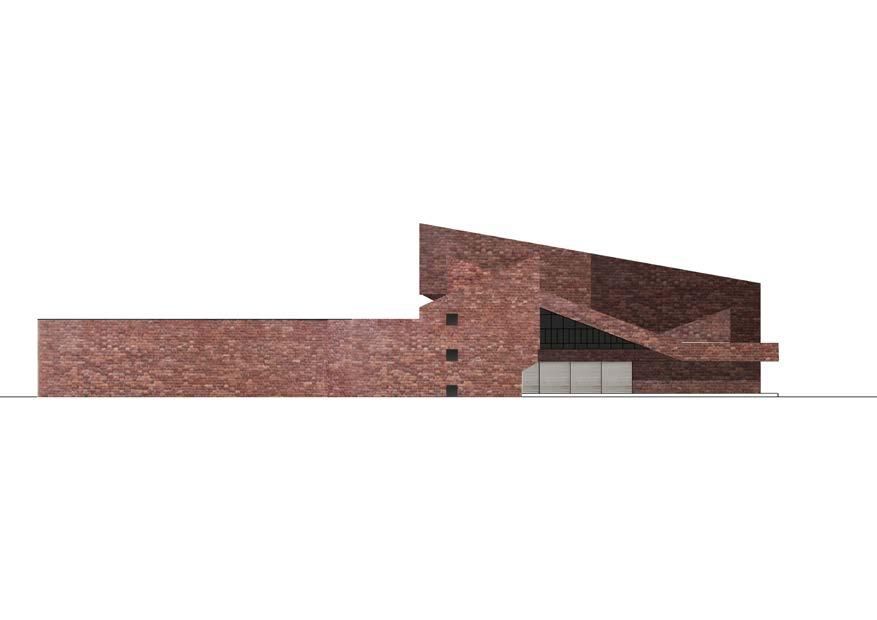

Queensway cinema and bowling was opened in 1976. It was situated in the heart of the Queenstown Estate and contained two cinemas, eighteen bowling lanes, as well as the Palace Cafe and KFC. The architect Chee Soon Wah was inspired by Finnish architect Alvar Aalto. The similarities can be seen in the overall geometry of the building and the facade material that initially consisted of exposed brick. At a later stage the facade was painted in light pastel colors that changed the overall expression. The buildings interior consist of a set of large interior spaces separated by smaller rooms. These rooms can be seen in the external geometry of the building. smaller geometric features are added on to the big volumes. In the end of the 1990s the building was abandoned and it has not been in use for the last twenty years. Queensway Cinema and Bowling was finally demolished in summer 2013.

Golden Mile Complex (1973)

Architects: Gan Eng Oon, William Lim, Tay Kheng Soon Design Partnership

Golden Mile Complex (1973) - 16-storey mixed-use

Architects: Gan Eng Oon, William Lim, Tay Kheng Soon, Design Partnership

Golden Mile Complex (1973)

Photography: DP Architects Pte Ltd

Architects: Gan Eng Oon, William Lim, Tay Kheng Soon, Design Partnership

Perceptions of a Tropical City

People’s Park Complex, 17.04.2013, 1.40pm, 6th floor, Chinatown

Guests:

Tay Kheng Soon (NUS & Architect of People’s Park Complex)

Josh Comaroff (Lekker Design)

Florian Schätz (NUS)

Professors: Erik L’Heureux, Alexander Lehnerer, Jörg Rekittke

Assistants: Jared Macken, Lorenzo Stieger

picture: Erik L’Heureux

There was a critical moment in Singapore’s history when the emerging nation’s architects and intellectuals envisioned ambitious approaches for the future of their city. The perception of a tropical city was infused with different cultural and ideological tendencies and led to a formal language that was sought by the architects to account for the people as well as the tropical environment. The ideologies were formulated and the forms of representation were strong and deliberate. The ambitions were bold and full of promise, however, they soon were not able to satisfy the demands of the zeitgeist and later became peculiar misfits in Singapore’s grand modernization program. Today, we find traces of this era scattered throughout the city of Singapore, most of these artifacts are now waiting to be replaced by more potent structures. These traces hold promise for imagining Singapore’s future architectural ambitions.

We will look at this previous era from an architectural point of view by analyzing these early incarnations of the contemporary “Garden City” with the tools of architectural practice – not through the nostalgia of lost memories, rather we will utilize our architectural expertise to extract the very essence of these buildings, transforming and projecting them into a concept of a tropical future.

Professors:

The Singapore Tropicana Studio is a celebration of the tropical city and its inherent atmosphere. Between the hot and the wet, the ambitious and the sensitive, the permeable and the sealed, the cultivated and the wild, each student will be assigned a piece of architecture and infrastucture located in the city that will inform his/her subsequent work. In the first weeks we will conduct multiple tasks to set the foundation for the following individual design work. Preliminary work consists of building specific models based on research of the assigned buildings and finding an appropriate mode of representation for the architecture in the tropics today. Looking at the gestures of the buildings helps us to find answers to the question of how the building as formal object contributes to the urban fabric, the surrounding atmosphere, and cultural milieu. By reconsidering eccentric features of the architectures through models we will discuss detail and identity. Other important properties in architecture such as formal operations of addition and subtraction, inversion and exaggeration, the ideas of concept and context, as well as how architecture impacts the city and urbanity will be introduced and thematized throughout the whole studio. 6 weeks will be focused for the design of a proposal for a new tropical building. In the last weeks the students’ individual work will be consolidated in an urban model for the future city. At the same time students will be curating the preceding output for the final review.

The students applying to the studio have the chance to be the first in a novel collaboration between Professor Erik L’Heureux from the Department of Architecture at NUS and Alexander Lehnerer’s Chair of Architecture and Urban Design at Future Cities Laboratory from ETH Zurich. The studio will also benefit from having two modes of lectures and critiques: Weekly presentation critics held by Erik L’Heureux with additional table critiques held by Lehnerer and his staff will be accompanied by and participated by Joerg Rekittke from the Department of Landscape Architecture at NUS.

The research/design work will be informed by lectures given by architects, artists and photographer on specific topics relating to the tropical city. We will leave the studio spaces regularly to visit practicing architectural offices in Singapore in order to get a glimpse of how other designers in our field conceive of a future for tropical Singapore. At the newly opened model workshop facilities on Create Campus the students will be engaging extensively in model making – one of the most important tools in architectural representation. By the end of the semester there will be a public exhibition of the student’s work at a location that is to be unveiled upon the beginning of the studio.