SLOW HANDS MAKE QUICK WORK

From tropical coolers and batiks, to the prospect of economic prosperity, the collective image of the tropics has evolved. The tropics have always been extolled through certain tropes . In literary works such as George Orwell’s Burmese Days, the tropics is presented to readers as an extreme environment, with certain remnants of neocolonial stereotypes described through visceral use of language. Words such as hot, stuffy and wild are not uncommon, suggesting a condition of the tropics that warrants its own phenomenology. The spatial geography of the tropics, as described by Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew, spans the region of the tropics extending beyond the equatorial belt with the hot and humid regions.

In recent times, the image of the tropics is one of the green metropole, brimming with seeming productivity - part of the larger network of the market economy. Wherein the tropics was once envisaged as a site of fetish, it now becomes the site of the fiscal

The colonial project is no longer a domain singularly expounded by the West. Through the spread of capital and the promise or chance of prosperity, China has effectively strongarmed nation states in a bid to harness the One Belt One Road agenda. This is usually carried out strategically through a prospective collaboration where the Chinese government would project a country’s success through a series of infrastructure projects that would be funded by them. These projects, often times are based on weak premises or solely serving the New Silk Road agenda and therefore, failing to generate any revenue. Consequently, the borrowing nation state falls into debt trap and becomes subservient to the economic demands of China.

The ubiquity of certain architectural technology has proliferated the built environments of thick and dense cities. This normalcy is even more apparent in large urban areas that are directly complicit to the forces of the market- one might argue that the metropolitan condition is therefore a participant in the market economy. Shiny steel glass skyscrapers are made of these.

Meanwhile, all along, the legacy of building in the tropics has left a robust architectural language that has been deployed effectively over the years. The second rhetoric would be, can and should the language of the tropical project infiltrate the way this new development in Colombo is conceived?

Across the island, almost half of currently commissioned projects are Chinese funded endeavours. The head honcho, Chinese Communications Company, from the beginning of the One Belt One Road Initiative has had a huge stake in these projects both in its construction timeline, and the operations of eventual buildings.

The Sri Lankans, on the other hand have had to catch up with the speed of the development of the city. The rich architectural legacy of Bawa and his colleagues warrant a kind of patience in crafting a building. Elements of buildings are crafted, master builders in constant conversation with the architectmaking the practice of architecture a slow one. In the meantime, developments of the city has left behind this domain of architecture that requires excess capital and time, and hence the rise of urban vernacular shells and buildings designed and built by the state and the everyday bass.

“But the craft of the hand is richer than we commonly imagine[…]All the work of the hand is rooted in thinking.” - Martin

HeideggerCraft had always had a hand in shaping the built environment of Sri Lanka. From very early on craftsmen had a big role in Sri Lankan folklore. During the reign of the Kandyan kingdom, centuries prior to British colonial rule, local artists and craftsmen enjoyed the frequent patronage of the King. Much of the work was related to refurbishing Buddhist temples, producing paintings and objects for the kingdom. The ecosystem of craft was a highly complex one, with a variety of specialisations for blacksmiths, carpenters and silversmiths. As the kingdom was soon captured in 1815, the notion of craft began to take on a different role, one of building the colonial empire. (Jones, 2008)

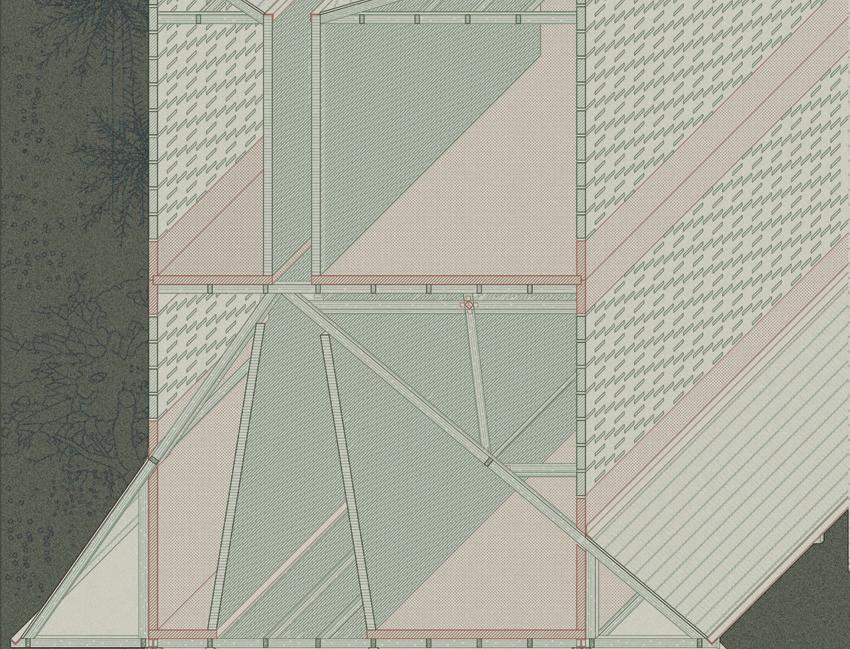

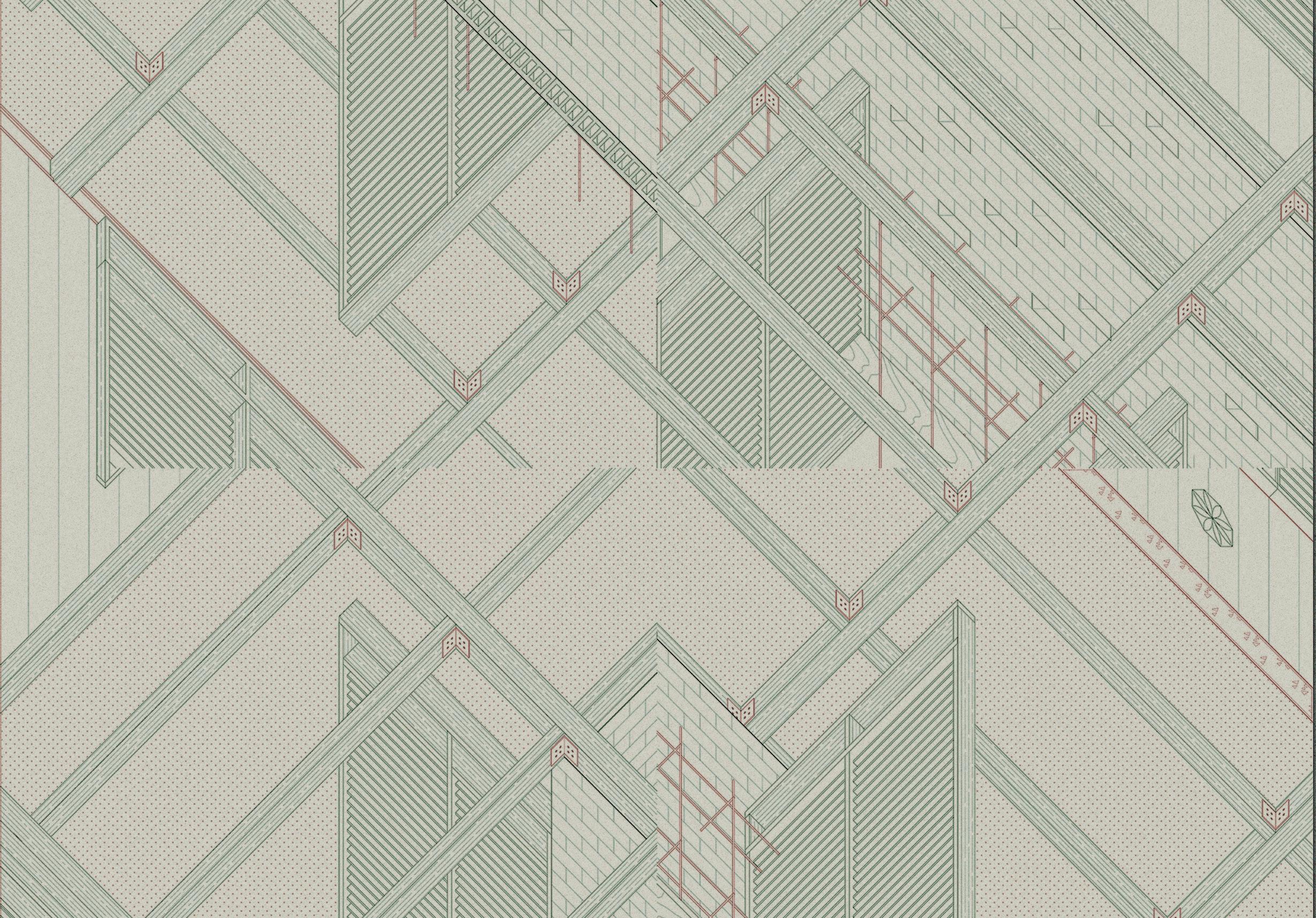

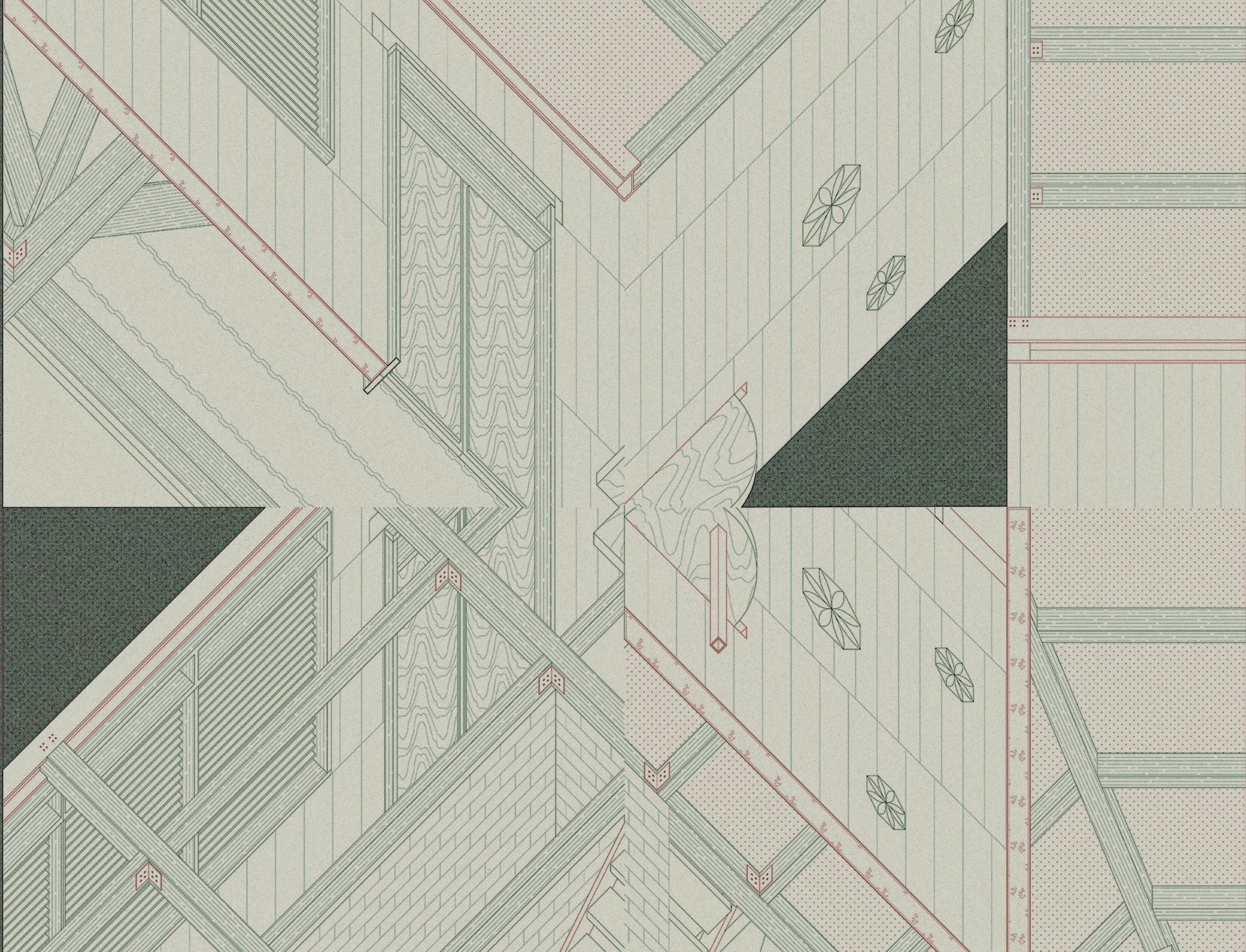

Up until 1950s, the construction industry in then Ceylon operated in a traditional model imported by the British. Contractors handed in tender rates, contingent on the rates on basses or craftsmen, which in today’s model would be the subcontractors. The drawing set was kept fairly basic and graphical, and much of the detail would be resolved on site or in the realm of the workshop with baass unahe, also known as the ‘most honorable craftsmen’. In the 1960s, building materials other than basic steel sections and cement were unavailable and had to be imported. Modern fixtures or fittings that were hard to come by were substituted for handcrafted pieces by basses. Basses were highly skilled labourers and craftsmen that worked with their hands to build. As a result of constraint, the spirit of experimentation and improvisation fuelled by an ecosystem of basses, created a deep interest in the chance of traditional methods of construction and craftsmanship.

The 1970s saw the apotheosis of this method of design, when Geoffrey Bawa took on buildings of a larger scale. A resort could be designed and built with a modest set of

twenty drawings, relying and collaborating closely with local builders and craftsmen to resolve much of the detailed design on site. By the 1980s however, larger public projects such as the new Parliament Buildings at Kotte warranted a much bigger drawing set - that of more than three thousand drawing. This was largely in part due to the fact that it was built by an international contracting firm as opposed to the deployment of local labour.

(Robson & Daswatte, 1998)Today, craft and the labour of craftsmen are relegated to a form of upper class ornamentation, only ever afforded by affluent patrons. This is a stark departure from the way craft was being deployed in the Kandy kingdom, which served public and civic purpose.

How do we define this term we call craft? Well, in its most Teutonic sense, craft represents strength, force, power and virtue. Inherent within the act of craft comes the emphasis on knowledge and skills that are technical and highly specific. This enables one to physically make an object through mastery and technique. Craft is therefore dedicated in the domain of material and technique. (Risatti, 2013) The mantra of craft purports the idea of practice over theory, the act of making before concept and therefore design before research. Herein lies a framework in which architecture can be practiced or operated by.

Curiously, the notion of craft had always been a Western canon. In this context, craft has come to mean many things. William Morris’ definition of craft suggests that there is no division of labour, rather than production without any machinery or tools. (Sarsby, 1997) In the South Asian context, craft is well aligned to Morris’ definition.

In craft we trust. Craft requires a conscious withdrawal on the reliance of intellectual awareness of process to a submission to direct-sense contact, out of which produces

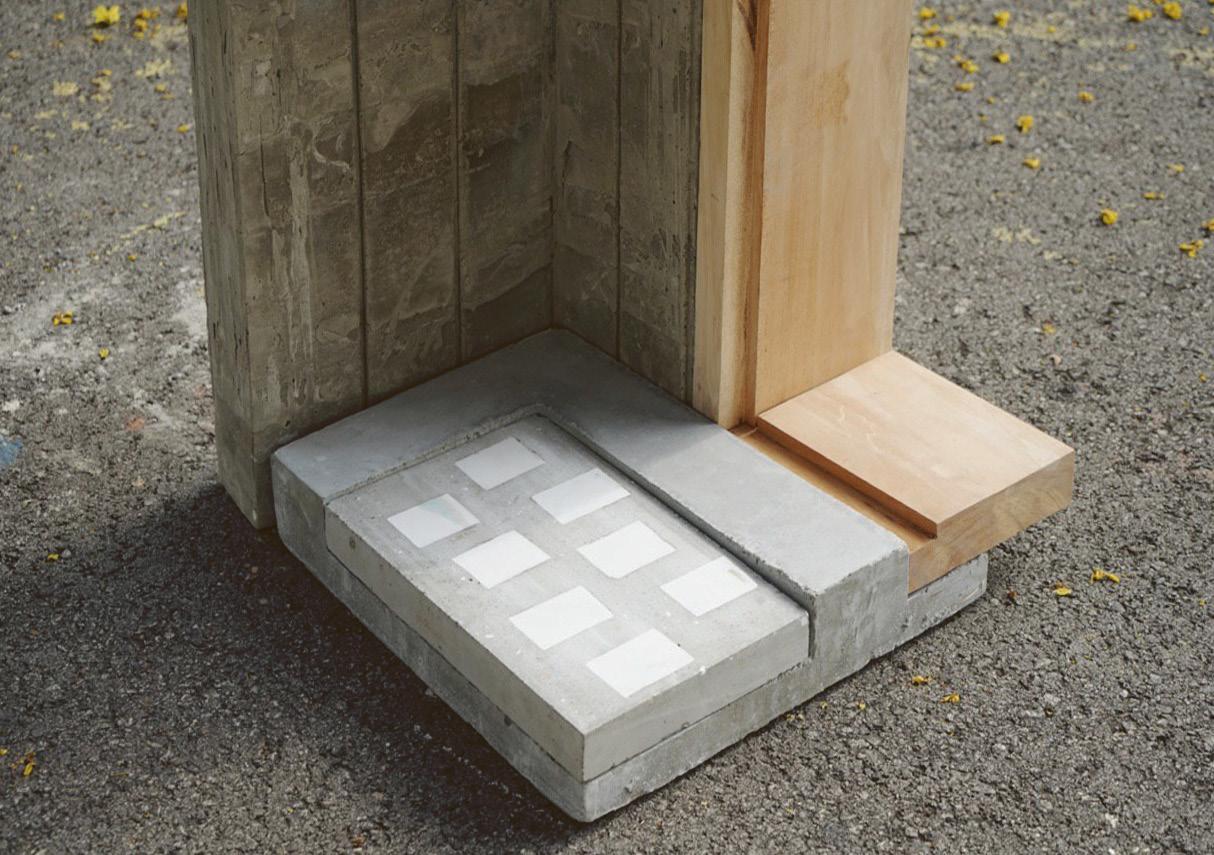

a new understanding of material. Oneness with the material emerges and a reciprocity in postures of the human hand and the gesture of the material results. (Robertson, 1962) In the Studio Dwelling project, Architect Palinda Kannangara works closely with a local master builder and a small team to build the building. The concrete walls were casted with board form concrete through a series of panel modules that repeat every 3 feet. The combination of modalities in the casting technique and the knowledge of the workers in working with a certain kind of concrete, resulted in a finely crafted wall surface that represented the material gestures of the boardform concrete, etching and registration all present within its surface. In this simple act of casting concrete, the builder is a craftsman. He knows his material and its limitations. Therefore, a craftsman must project an attitude of attentive responsiveness. Acceptance and even embrace of the nuances of material, roughness of concrete, imperfection of material curing - is a distinct quality between

craftsman and technician. (Robertson, 1962)

A craftsman is often thought of someone who works with the hands. He or she however, should not be confused for a handy layperson. The ecology of craft warrants a method of working that requires a highly sophisticated and evolved set of tools that enable the craftsman to do his job well. Just as the architect has the pencil to sketch, in an act of putting ideas into paper, the craftsman has his tools to shape, carve, sculpt away or unto material. In Sri Lanka, and even parts of South India such as Rajasthan, families of craftsmen pass down tools and methods of making across generations. The tool is an extension and specialisation of the hand that alters the hand’s natural capacities. The skilled user does not think of the hand and the tool as different and detached entities; the tool has grown to be a part of the hand. (Pallasma, 2015)

Craft is typically ascribed as an outcome of labor over time. Postures and efficiency in one’s gestures are paramount in arriving to an outcome. In craft, a craftsman should accept responsibility for every decision, every move or gesture is a conscious act. The final outcome is a complete solution to a problem, or means to the an end - of which, fully owes to the man’s interaction with material. Herein lies the character of careful and intentional execution - very much like a photographer would shoot on film making every shot count, as oppose to a digital format where the abundance of exposures are much more forgiving.

The practice of architecture had always been inextricably linked to craft. Paradoxically, the discipline of architecture and craft may be sitting at the varying spectrums from each other. At its very foundation, the discipline of architecture had always been concerned with questions of methods of representation. The history of drawing was to represent geometry in the form of instruction for a builder or contractor to execute. The drawing was a quintessential bridge between intent and execution, one that had possibly stifled the chance for craft to fully come through.

It was a method of exacting representation and communication that produced a division of labour and material that consequently removed question of craft. In the advent of technology and software, the hand drawn is quick to be replaced with by Computer Aided outputs, handcrafted architectural elements are substituted for readily available products and proprietary systems. The speed of the capital inception and the hasty project timelines has added pressure unto the architectural ecosystem. All too readily available, the practice of architecture quickly becomes a practice of assemblage, rather than one of the making. But enough with the negativity, I’d like to offer the chance for our discipline to redeem itself!

In The Thinking Hand, Juhani Pallasma notes, today the architect usually works from the distance of the architectural studio through drawings and verbal specifications, much like a lawyer, instead of being directly immersed in the material and physical processes of making. (The working hand, 065) The crux of this dynamic is the notion of circularity, constantly straddling between the idea to sketch, model, full-scale test and back again. (Pallasma, 2015)

The connection with the processes of making continues to be seminal, an architect today searches deep personal friendships with craftsmen, artisans and artists in order to reconnect his/her intellectualised world and thinking with the source of all true knowledge. The real world of materiality and gravity, and the sensory and embodied understanding of these physical phenomena. (Pallasma, 2015)

In putting forth a continued relevance of craft in the industry: Craft implies a collaboration between man and his material. Instead of forcing a preconceived notion of form, the craftsman needs to be aware of the innate characteristics of materials and his gestures. Just as architecture is the act of materialising what was translated from pen to paper, the architect too needs to be concerned with the inherent qualities of construction material and processes.

One rhetoric would be: Can the practice of craft, help to build up a position of resistance but capitalize on the latent potentials of a technological civilization, neo-liberal economy? (Robertson, 1962)

“In craft we trust, in construction, we trust blindly” - Author

In Sri Lanka, a craftsman that is concerned with producing a building is referred to as a baas. The baas is someone who specialises in a specific craft discipline and is often employed by clients, architects or construction companies to do specific architectural features or details.

In Sri Lanka today, there are local basses all over the country that support their area’s building industry. In the southern part of Colombo, in a place called Moratuwa, Sudesh, a local craftsman specialising in the carving of timber framed windows are one of the many craftsman that have continually supported the building industry in his hometown by providing carpentry services. He operates from a small workshop not more than 30 square meters in size, with a small group of apprentices that cut and carve under his watchful eye. He passes down the techniques he had learned from his father unto his young apprentices through training and repetition of gestures. Sometimes, he provides for projects in the city of Colombo. These days it seems, the demand for crafted timber window frames for the city has waned, as urban construction techniques that warrant speed and efficiency, have found substitutes in the form of powder coated aluminium modular window frames.

Labour for construction sites, were usually dependent on the scope and scale of the buildings. Villas of a larger scale saw ‘gentlemen contracting firms employed highly skilled basses or craftsman for carpentry work. Rajendran used to be one of these carpenters. A big shift in construction processes that required manual labour of the hand occurred when concrete mixing trucks and hollow concrete blocks were introduced, eradicating the need for informal labour mixing concrete and laying the aggregate. Soon Rajendran’s timber craft will soon have the fate of being

replaced, just as concrete blocks replaced manual casting. (Pieris, 2017)

Current day Sri Lanka, the notion of ‘pure’ craft is under the threat of the speed of urban vernacular developments. The Sri Lankans, have had to catch up with the speed of the development of the city. The rich architectural legacy of Bawa and his colleagues warrant a kind of patience in crafting a building. Elements of buildings are crafted, master builders in constant conversation with the architect - making the practice of architecture a slow one. In the meantime, developments of the city has left behind this domain of architecture that requires excess capital and time, and the hence the rise of urban vernacular shells and buildings designed and built by the state.

In downtown Colombo, a slew of concrete shells are being constructed everyday by a labour force of both skilled and unskilled backgrounds. Some have had proper training under years of experience with construction companies, others under apprenticeship with local builders while a large part of the labour force are first time workers on site. With much of the labour force of Sri Lanka deployed abroad in the Gulf states, the diaspora of this skilled labour has left a gap in the construction industry on the island. As Sri Lanka comes out of militarization of civil war, its capital city quickly developed into one of the fastest growing cities in the world. In 2015, Mastercard Global Destination Index rated Colombo as the fastest growing city in the world. A large part of this development owes to both the boom in tourism industry and the drastic inflow of Chinese capital. (Daily Mirror, 2018) The shortage in skilled labour has perpetuated the dismal quality of buildings in the city.

As a result of the growing metropole, spawns a thriving local industry of building products. From Square Hollow Sections (SHS) to

custom steel extrusions, local workshops have turned to making these building products to supply the construction market of downtown Colombo. Many of these workshops can be found on the fringes of the city. Aside from local material workshops, many building junkyards can also be found in the outskirts of Colombo, near a place called Moratuwa. These are treasure troves of recycled building parts, decorated timber columns, beams, and timber framed windows. Outside of the city, many houses along the coast make use of these recycled building parts in ingenious ways. A dedicated industry of pre cast concrete rafters, balustrades and recycling of doors from colonial buildings, closed the gap of the lack of skilled craftsmen, which today has a massive diaspora in the Middle East.

Albeit the uncanny beauty that is of the urban vernacular, issues of labour, especially that of skilled labour still remain at large; an issue that has been relegated to the backburner of the state. One of the few practitioners that is critically addressing at the current modus operandi of construction in Sri Lanka in an optimistic manner is Milinda Pathiraja.

Founder of Robust Architecture Workshop, Milinda, designed a Post war collective library that resolved issues of skilled labour in construction in a profound yet simple way, the method of construction was staggered and a means to teach skills to the ex army personnel who were the labourers. The building would be built step by step, beginning with simple construction of flushed concrete walls to advanced methods of casting. By teaching the basics, through to complex details, the value and agency of the architectural proposition was that it imparted knowledge and skills, effectively training unskilled individuals to skilled labourers.

Is this direct method of making a building as a means to address contemporary issues such as labour a way Sri Lankan’s can build with the Chinese? Can craft be taught to the Chinese?

Chinese Communications Company and China Harbor Engineering Company are two of the biggest construction bodies that currently have a massive presence on the island. The

Rajendran, a Steel Worker in Moratuwaportfolio of construction projects that have been awarded to the Chinese companies have led to some bitter sentiments by the locals. Of recent times, the Ceylon Institute of Builders, the island’s own consolidated construction body, have resorted to signing a memorandum of understanding with the China International Contractors Association to ‘share’ projects, in the hopes of a increased Sri Lankan stake in the participation in the construction market. (Global Construction Review, 2018)

The irony in the Chinese-centric awarding of tenders is that the projects are often borne out of investments made by the very same companies. These companies would then deploy Chinese labour, construction materials to construct a building that is financed by the Chinese, in the circumstance of debt to Sri Lanka. The capital of construction comes back full circle to the mainland it seems. (Reuters, 2018)

From very early on the notion of cultural strata had been well established in the Sinhalese culture. In the Kandy and Kotte kingdoms, caste systems were inextricably tied to individuals’ roles or profession in society. When colonialism came into the island, a clear stratification between the British and the locals was quickly established.

By the early twentieth century, Michael Roberts noted that Colombo had grown to be a “primate city,” the center of political and financial deals within the island, its principal port, and an arena for display. The groups that predominated in the colonial city were the British residents, the Burghers (descendants of Dutch and Portuguese colonists) and elite families from indigenous ethnic communities. (Colombo

Telegraph, 2014)The western ideals were indeed aspirational. Locals had a deep desire to live the western lifestyle. Bevis Bawa, popular social columnist of the post-independence era and not so coincidentally Geoffrey Bawa’s brother who also practised landscape architecture, reflected sarcastically:

“The last generation were magnificent in their grandeur. They memorized the facades of vast houses they saw all over Europe, returned and built them on acres of land they or their fathers had owned in the city. Houses like Gothic churches, Victorian wedding cakes. There was no question of being nationalistic in those days. Most people were for the ways of the West and some secretly wished they were from it.” (Pieris, 2017)

A small group of cultured Burger gentlemen conceived of an anticolonial Ceylonese identity influencing the westernized Indigenous elites. Nationalism was, paradoxically, nurtured amidst conflicting Western aspirations. These negotiations of identity manifested in private institutions such as the Orient Club which excluded Europeans. The challenges to colonial authority by the local elite were

facilitated by the liberal values learned via education in Britain. (Pieris, 2017)

Capital on the island belonged to the a small group of upper class, commissioning projects such as the Bagatalle House in Cinnamon Gardens and the Lakshmigiri house. These houses were not only big in its footprint, but heavily referenced colonial bungalows back in the United Kingdom. The rest of the island it seems comprised of dwellings in the form of the basic de Soysa Walawwa, a large residence that was made simply, comprising of a courtyard and a verandah. These were simple structures that were inexpensive to build and inhabit. (Pieris, 2017)

Today on the island there seems to be the emergence of various sources of capital when translated into built form, there seems to be four predominant archetypes. Expediency driven, profit driven, state driven and affluence driven types. (Pathiraja, 2018) These four archetypes have been well established since the island state gained independence from its colonial masters.Today, however, we begin to see the emergence of a new archetype, one that is originates from the Chinese. With projects across the island, as far up as Jaffna, suspiciously close to India, the Chinese are coming in a big way.

The relationship between the Chinese and Sri Lankans is not a uniquely new one, but one that has been crafted over the years. Curiously, the relationship between the two date back to early 14th century, through the military figure of Zheng He when he had first interfered with the civil war of that time between the Kingdom of Kotte and Jaffna.

In modern times, through the years, the capital brought forth from the Chinese have come in the form of both grants and loans for a variety of purposes. As of 2012, China was Sri Lanka’s largest bilateral (country to country) creditor,

displacing Japan. Since 1997, the island state has borrowed around USD2.96 billion from China. Interest ballooning however, has led to accrued debt of USD4.9 billion which have to be repaid on average within 12 years from borrowing. More recently, two major projects in the country, the Hambantota Port and the Colombo Port City, has left a deepening debt trap. This major dent in the Sri Lanka’s balance sheet, results in a lop-sided dynamic in Chinese-Sri Lankan relations.

Yet, the plot seems to thicken. Historical materialism, it seems, trumps everything: “there is no power on earth that can stand in the way of intrinsic material forces.” This is indeed the case with our Sri Lankan and Chinese friends. Over the years, the Chinese have gifted Sri Lanka with many things. Public buildings, grants for infrastructure, armament aid for civil conflict just to name a few. The Chinese foreign policy in diplomacy is a long and patient strategy, it could be akin to a Bonsai Tree. In Planting a Bonsai Tree of sorts, the BMICH, a conference hall for the memory of the fourth prime minister of Sri Lanka, was a gift from the Chinese and built in the 1970s with a combined labour force from China and Sri Lanka.

40 years on, the building has served multifaceted role in cultural production between Sri lanka and China - from conferences, shared events, cultural exchanges. The building, in many ways, perfectly captures the dynamic between Sri Lanka and China, a friendship that is bounded by capital through the means of built form, and transplanted sino-modernism that employs the use of Chinese building materials and processes.

This is an outright disclaimer: I am not for the return to pure craft per se, machine production will continue to outshine and ease the burden of labour. In light of the tricky relationship between Sri Lankans and the Chinese, the thesis unpacks the problematics of the two entities coming together, as a latent potential to produce architecture. This preoccupation is specifically concerned with the domain of craft, construction and capital in the island state. The thesis also looks to question the role of architecture in a such a situation; is it just a mere stoic symbol of cultural exchange? Or can it do more, almost like an active agent that warrants involvement from both parties?

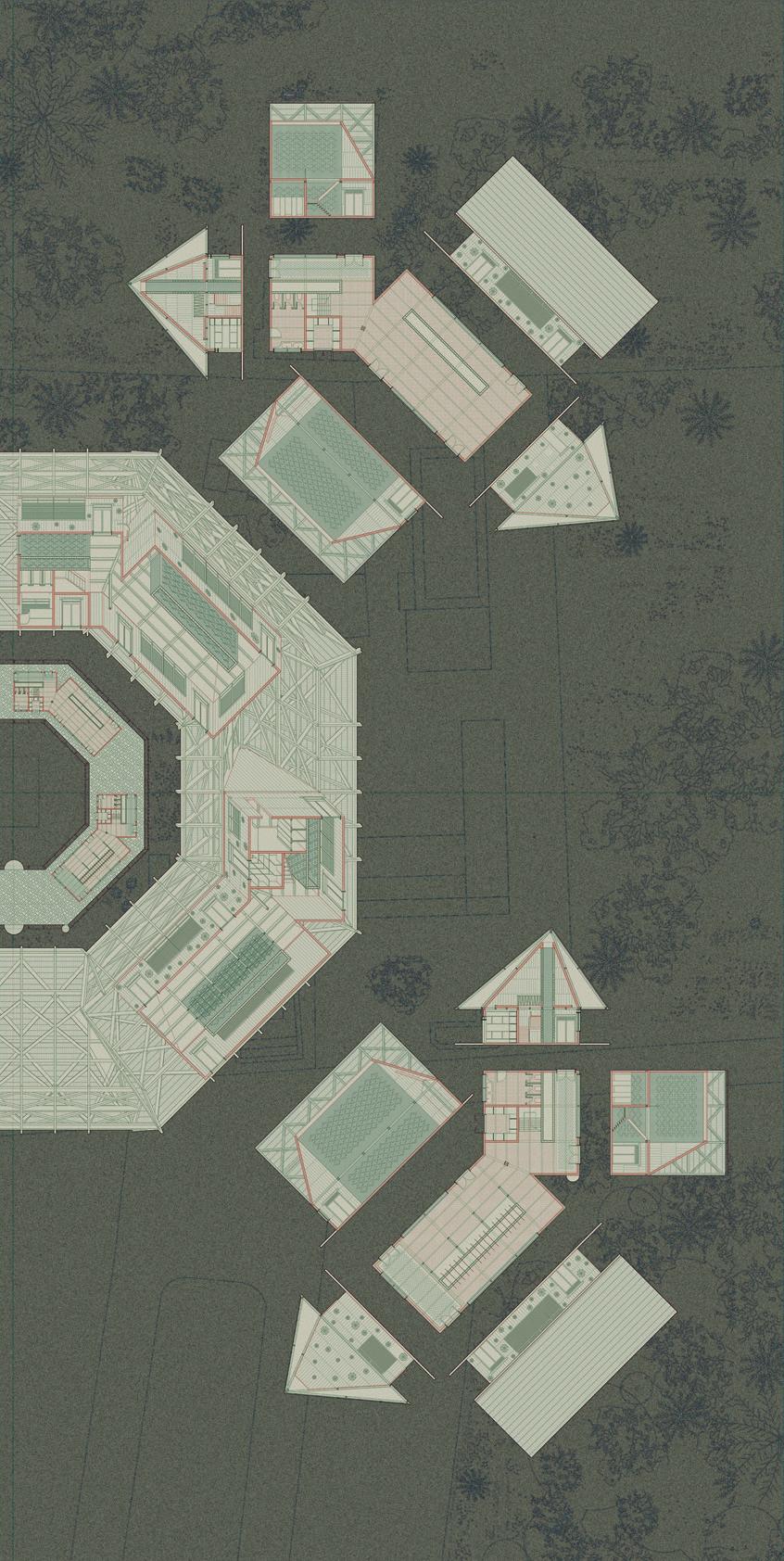

In the act of finding site, the plot of land across the BMICH is chosen as a perfect site of tension to articulate the ambitions of the the thesis. The site of the project is located in Colombo No. 7, along Bauddhaloka Mawatha. This is the main political and institutional strip of the island, where many embassies, schools, national cultural grounds are sprinklered across. The plot of land sits across the conference hall. The plot itself is charged with some very interesting neighbours.

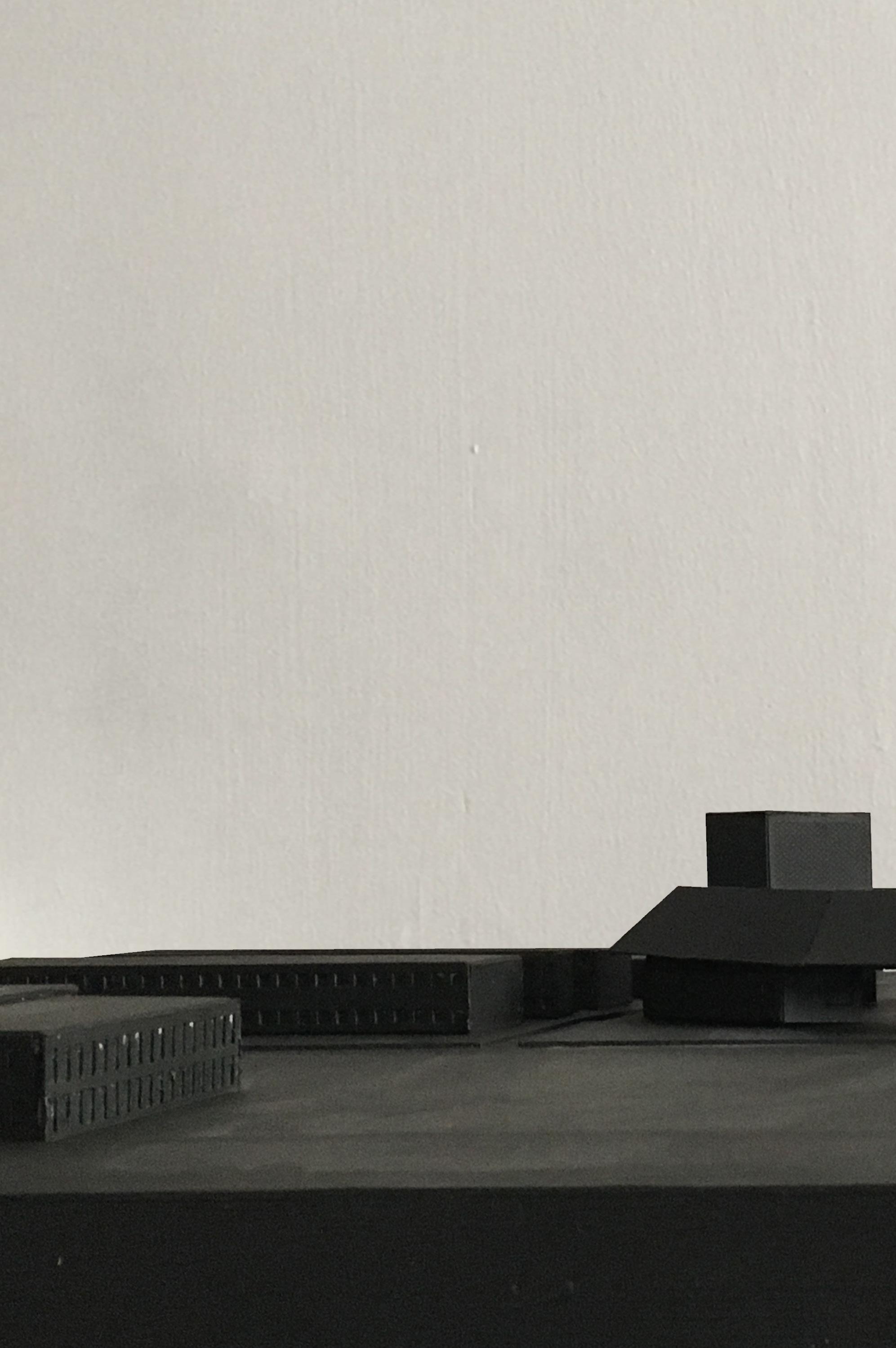

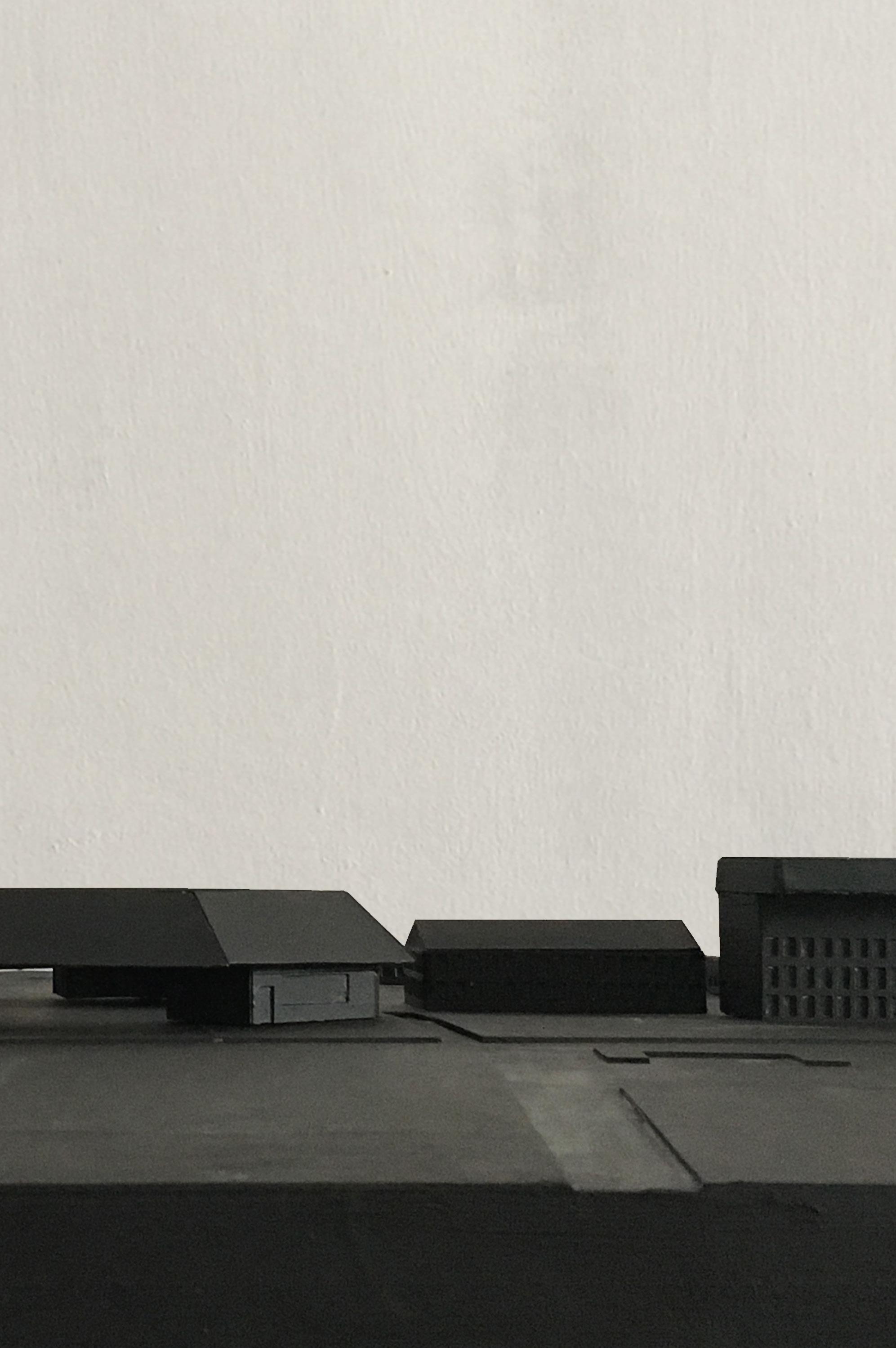

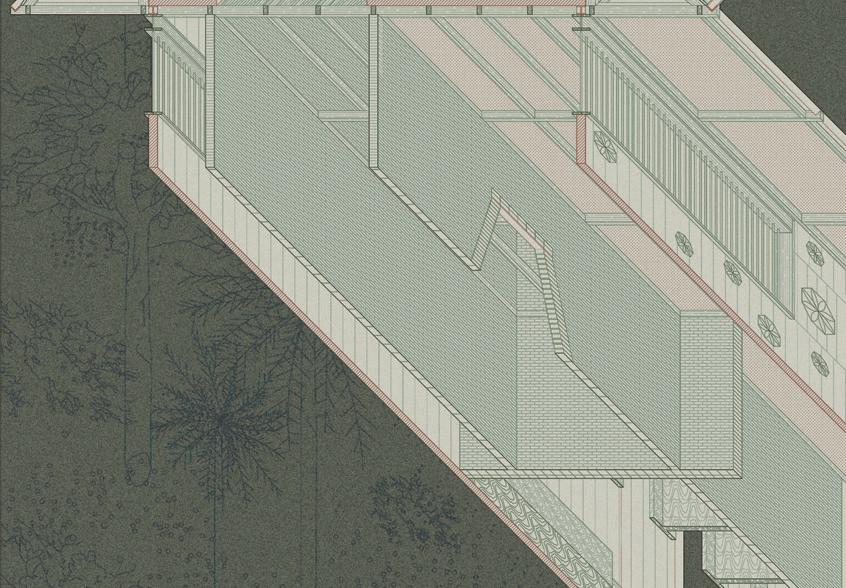

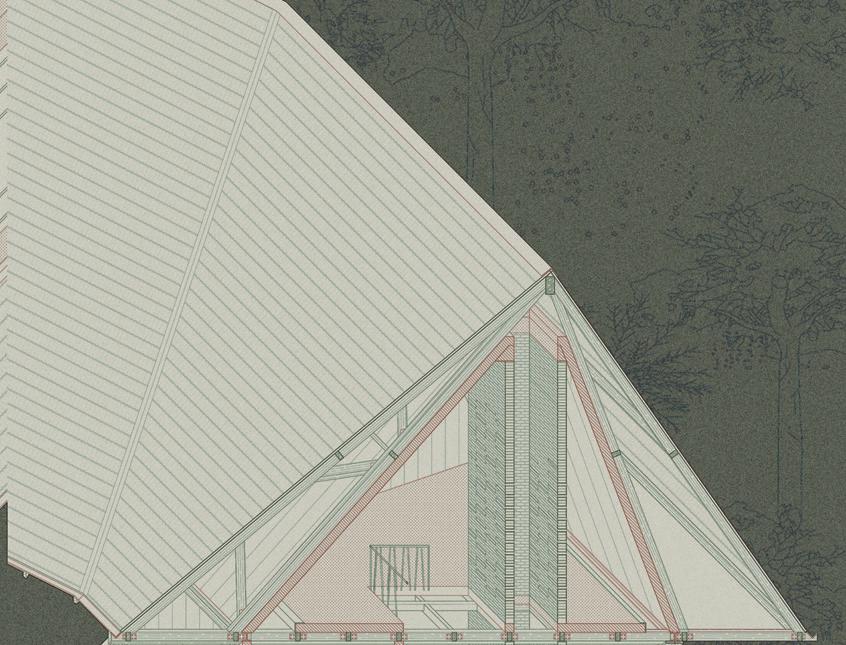

As its neigbour, there is the Chinese Embassy and the replica of the Ramawa statue (another curious gift from the Chinese). The architectural proposition is a Trojan Horse of horse of sorts: A gift from the Sri Lankan government back to the Chinese. A building that houses Sri Lankan craft, urban vernacular building processes and Chinese building technology. The building is a referential figure of the monument that it sits across to, in a fragmented format. The massing hug around a center that is the Sinhala Association. Curiously, it also takes on the plan which protects the navel as a kind of centre, a figure heavily eferenced in South Asia for a long time. A gentle counterpoint to the monumentality of the conference hall.

The metaphor does not stay at the level of the building, but also in the processes of its making. The collaboration begins early, from the time when the Chinese and Sri Lankans build together. They share knowledge and

teach each other of the merit of speed or slowness, construction or craft. The broader architectural project is that is as much

about its built form as it is about the form of building/or the process of building. As Sri Lanka gets ready to kick into overdrive with development, the building comes at a time for much needed reflection on craft and construction practices - a simple symbol

of collaboration between Sri Lankans and Chinese but also an active agent where the two teach and build together in the act making of

architecture in the contemporary context of the modernist metropole within the framework of the market economy. Using Sri Lanka as an appropriate domain to project the design framework unto.

Moving forward, drawing and making is a parallel act. The act of making is crucial in design. Some of these are reenactments of carving, boardform casting techniques, and experiments with material. The making helps to clarify ideas into material form, which is fundamentally important to practice architecture. Through the nuanced understanding of the slowness of craft, perhaps emerges an economy and efficiency in doing things.

Alas, we can finally say, Slow Hands Make Quick Work!

the building.

Ultimately, to project forward the thesis is an earnest attempt in finding praxis. More importantly, it looks to set up and formulate one’s own understanding of means to practise

001: Renovation at Lunugganga Estate by Geoffrey Bawa

001: Renovation at Lunugganga Estate by Geoffrey Bawa

PK: I am very selective in my work.

ZA: Alan Tay, from Formwerkz, was just sharing with us how you choose certain projects.

PK: Yes correct.

ZA: Are there some projects like towers that you’d like to do?

PK: I have not say no to anything, but the projects select me and the people know what I am doing. So they know that I am not doing towers, so they don’t ask me to do towers.

ZA: There has to be understanding that when they come to you, they come for a certain sensibility.

PK: I need to show them some point of reference when they want to get things done. I ask whether they have seen my work or why they like it?

ZA: A mutual understanding?

PK: If they’re just looking for an architect, I can’t work. Because I am not just an architect, all the projects I am doing it for myself. This is just another project for me like that. People ask me how do you design for yourself, and I think that’s the hardest thing to do. You want to try to do everything that you learned, but it was not like that. So this was just another client, the client is me. I knew what I wanted and I just designed in one sketch and that’s it. I didn’t change much, just a few elements, some small details. Otherwise it’s just the same design.

(Palinda leads us to the office)

PK: This is the only room that requires air conditioning. Are all you architects?

ZA: I am Kate’s mom.

PK: Oh I see! And what about both of you fininshed, recently?

ZA: We are both in our final year at NUS.

PK: I was at NUS but that was during the holidays. We had a small barbeque and all that, near your campus. That was the last day of your campus opening.

PK: They were saying that the campus is permanently closed for a couple of months. Is it closed already?

ZA: Not completely, some parts. We are still getting some spaces to work. The studio space is slowly getting smaller.

KL: That’s right.

PK: So basically, we start with physical models. We don’t do like 3D or anything like that. We like to use physical materials, and it helps us in our design. You can pick it up, feel it, turn it around. Some are just massing, some are just study models. This is the extent of the office.

KL: How many people are here?

PK: Its all here, 8 in total. Sometimes I get an intern from some other country, he was here maybe 6 months back. Because of the visa, is not easy to get it here. So most of our staff are from India, and Bangladesh. So far I am open, I am getting some from European countries but so far they run into issues of visa.

PK: So basically, this house is facing the west sun. This is the east. So in Sri Lanka we have to respond the sunpath, otherwise you are getting too much heat and light from the sun. So the facade is thick with only a few perforations to prevent the excessive heat from coming in. The other thing is the traffic and the view, is not favourable so therefore we control it using the facade. So that’s the story behind the project, how I control the light and the combination of these spatial means.

ZA: The perforations are performative?

PK: Yes in a sense. They control the light and

Studio Dwelling by PKAthe allow cross ventilation through, this you will see in the upper levels. Come with me.

(Points to the operable windows near the facade)

PK: These are louvers, so you can open and close them as you wish - as and when you use air conditioning. Here I was trying to keep it open, but humidity is very high in Sri Lanka, so you can’t have this fully open, when the computer is on, they generate a lot of heat, so you can’t fully open in the office. But here in the upper level, you can leave it fully open, and again you cut off the neighbourhood, but you see parts of it.

PK: And to operate these louvers, you have to open it at one go. These are standard louvers that are appropriated to be used in vertical format. I just turned it the other way. There’s so many advantages to this, you can clean it so easily! So I have an issue with the bigger window, every panel I can’t clean. So I’ll have it cleaned maybe once a year. But its ok, there is no dust coming from there. This is basically my private space, sometimes the meeting space extends up here. This is a living space basically. There is another space upstairs, where I mostly take guests - so come!

PK: This space is my bedroom, I have another guest room below, but now I have given it to the dog.

(laughter)

ZA: How long has this building been built?

PK: Its only 3 years. Since 2015, not more than 3 years even. It looks old, but the building is finished like this. I hope it doesnt age any further.

ZA: Is the construction process done through local builders?

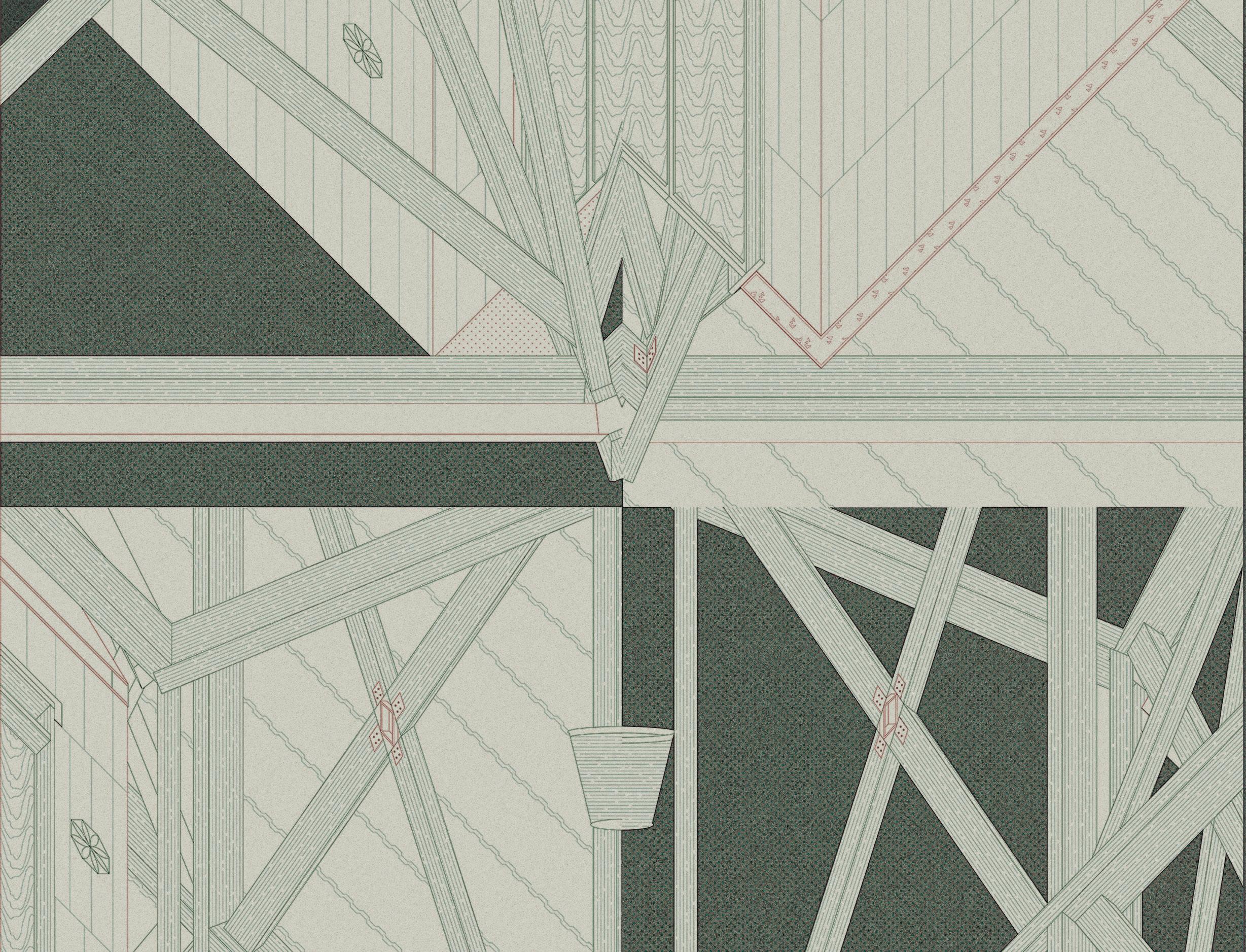

PK: Yes it is usually a local builder. I have this one guy in my few projects, I work with a small team. One guy even, he is not a contractor, he’s a basic worker and another two helpers. Same person did the wall up to this level. From the

ground up till the very top. Concrete is done in timber panel work and its all done with just one panel. You can see the join here. Here is one panel, and here another one. One module repeats for every 3 feet, so it took a little bit of time. Its not fast, where usually its done every 10 feet. I repeat 3 times before moving up to the next level. Its a little bit of time consuming work, in Sri Lanka we have time. Maybe its different from Singapore, where time is of the essence, here we have plenty of time. You start a two year project, it might be three years. For this project, there is definitely no pressure. I just thought of building it. Now you can start to see the sun come in, where this small patches of light fall, you can see how harsh that sun is, and how the wall is protecting against it. Come lets go up!

(We head up towards the final floor of Palinda’s residence.)

KL: Interesting furniture!

PK: Do you know what is that? It’s actually old printing press stencils. Letter setting tray, where they would select alphabets from for the printing press. So one would take up their different alphabets for printing newspapers and send them for printing. Its from an antique shop! I thought it made for a very nice facade, very Corbusian no! I thought what a nice coffee table!

ZA: Its very peaceful in this area.

PK: Yes, and it is not very far from Colombo. Where are you staying at the moment?

ZA: At the Fairway Colombo.

PK: Ah okay! That is fort. On a Saturday its easy, on Sunday you would run into abit more traffic. You cant get this kind of natural setting in Colombo, where youre surrounded by birds, bats and all sorts of wildlife.

ZA: I noticed there are some kind of new towers here. What is happening?

PK: Yes, there are all these new developments in the city, Moshe Safdie is here, and there all these other apartments coming in.

ZA: Where is the money coming from?

PK: Actually, these are for investors, like foreigners, or expatriates. Most of them are for rent, people who are living here are very few. And this is not their only house, they have an extra party place. Its just an investment, for example if that house costs 30 million now its like 50 million. After complete, you can sell it. Especially the foreigners, who can buy easily.

ZA: I saw that you had a new project, the book building.

PK: Oh yes, how do you know that?

ZA: I follow you on instagram.

PK: Let me get something for you, some warm water? I can get you a tea. With milk or without milk?

(Palinda rings for his helper to prepare some tea)

PK: Yes the book building is being constructed and is almost done, but it is not open yet. I have not even photgraphed it yet. People have not moved in yet. Without the people, I think the building is not functioning for me.

ZA: So you like to take the pictures of your buildings with people inside?

PK: I do want to have, because its a public project. It has a small auditorium of 250, it has a small library, it has a book store. So basically its called a book stack building, I wanted to see the elevation like a kind of stacking, the

concrete walls have lines.. It looks like that (points to a magazine shelf) the building looks like that! The design is made out of all concrete, its an in situ method, not pre cast. Sometimes I have seen other building, they have made fiberglass panels, which they pour the concrete and fix it against the wall. So everything is done on site. Its not easy to get that finish out of concrete nowadays, you have to be careful when they are removing the corners can break. And they have done a good job.

ZA: Did you use a special aggregate for the building?

PK: No, nothing. Just ordinary plywood, and I offer up a new method. In Sri Lanka, we don’t have a lot of concrete buildings. So its very few projects, I am the only person really doing in concrete. There are other people doing it, but they cover the material. They don’t want to keep concrete as a material. I don’t like fake building, do something and then cover it like timber, or stone or something else. I don’t do that anyway from my start. The material contributes to the design. I want the concrete as an interior finish, as well as a material that doesn’t reflect light. Its like an aperture that you leave fully open, and you let the light in. You can’t get a nice photograph if your shutter speed is too fast. Likewise I am trying to do in this, I am trying to fully absorb all the light that is coming into this room. You know the walls help to reduce the amount of light coming in, otherwise we can’t sit like this. You have some white buildings that have too much glare. Here I dont have too much glare, I can focus straight to the outside. That is the one thing which is good about the concrete. I am also very particular with the colour of the cement, we did the tests with different batches, and bags of cement, and we found the correct concrete colour. The concrete comes in white, green and even beige sometimes. So, which colour you want is something you need to experiment.

ZA: Have you experimented with pigmentation?

PK: I have not done adding colour, I might do that I was thinking. Even both projects, are all natural cement colour. But yeah, its nice to have a pigment, but you need to have

a right project for that. It depends on the context, and everything has to come from the design process. I will never use anything that is superficial. I like rammed earth, but I never want to impose it on the next project. If the project requires rammed earth, I will do it. That’s it. Some people are only doing it in rammed earth, some are only doing in concrete, I never want to have that in my architecture. I do this concrete, next one is maybe timber, next one is maybe totally brick, next one is totally rubber. So, that’s the way you should be. Otherwise it is totally biased with the material you want. It is not for me. I am totally open to other materials in my architecture. There is a guideline and discipline always that controls your architecture, and that is you. It has to be like that, because when somebody sees that they will be able to say oh this is by Corbusier or this is by Louis Kahn, this is by WOHA. Kerry Hill projects, you could probably tell it’s him. And that is beyond material, its because of something behind the design process. My storyboard or design process is always behind

the context. You know in the book building, I want to extend the cantilevered part, its alot of stacked elements. Without concrete, you won’t be able to achieve it, brick won’t work. The whole structure is harnessed from the inside core and the exterior is held by cantilevering fins from this core. It’s a beautiful structure design.

ZA: In the projects, there seems to be a certain consistency in the way the buildings are presented. For example, in this building, you can read the inside and the outside and I feel like that there is a recurring thing in all projects.

PK: Yes, I think it is a consistency, that is coming from me. Connection, landscape, giving respect to the nature and trying to be a part of the nature, that’s what I am trying to do. That is within me, I can’t help, and I can’t change it. I am Sri Lankan, and we learn these things. Sri Lankans we always try to connect with the nature and we always try to be a part of the nature. We can’t reject, we have to accept it. We have a culture coming from Buddhism and its connected. We are by force, to place our building in a very nice environment - so we have to give back. I am not saying that a building with a roof garden is a good enough effort, it has to be beyond that. I know Singapore government is saying that, but those are rules, just to sustain the environment and by law you have to give back. I am thinking the other, we have to be sensible and sensitive to nature, without imposing. Then its very natural and not artificial.

(Palinda receives some tea and snacks)

See you have to eat the Kande leaf, and we eat with the nature as well. Just remove the leaf and eat the filling.

Studio Dwelling by PKA Palinda Kannangara is a registered Sri Lankan Architect and practices under Palinda Kannagara Architects.

The tuktuk pulls up along Bauddhalokamawatha drive, Hirante’s office is in the district of Colombo 07. Upon arriving, a short call to Melissa (Hirante’s intern), leads me to an inconspicuous timber door, well hidden in the shadows of thick foliage on the property’s front elevation. I’m being led through a brief but dark hallway before turning into an office. There, Hirante briefly discusses work with Melissa before our conversation begun proper.

HW: Discuss with him and tell me. See if they can do a different kind of bond. This is roughly what it is. The problem is that the mason says that this might topple. Not against the wall like there, bloody hell.

See the problem with architecture, there is never enough time to do our own work, just designing for other people. And I’m trying to build this garden seat.

ZA: Are you trying to build on a project of your own?

HW: Just a garden seat. I have a lovely garden, which I go if I need to think, I will go to the garden. So it’s a very important seat, where I can meditate and think about work.

ZA: And think about work?

HW: Yes that’s the whole idea, that it becomes a part of you and the work gets better. You’re studying to be an architect? It’s going to take much of your time.

ZA: Yes, it has been.

HW: Because the actual work you do on a machine, is just the labour. The real work is what goes on inside your head, and that usually doesn’t happen when you’re drawing. Like often I work here, and then I go out, and sit in bed or think in the garden with a cup of tea. And then only my mind starts functioning properly in a creative way. When you get into that kind of quiet zone. There’s a very good article on the New Yorker about it; you should read it. Its about this musician he is a prodigy

and he talked exactly about this. But I think it’s the latest New Yorker. I read this yesterday, I will email it to you. He talks about, like when he writes music, he says he locks himself up in the attic and he doesn’t talk to anybody. Because he’s working and at that moment, he is just putting things together in his head, and he needs the silence to be very creative. So, it’s very important to cultivate, and you have to create the conditions for it to happen in your environment. So I’m trying to create it now with the garden. Ok so now, what do you want?

ZA: (laughter) Actually, I really just wanted to have a chat with you.

I came across the Neelung Arts Center, an found it to be a really interesting building. And I realised that there was more to it to be done.

HW: Did you go inside and see the model?

ZA: Yes, we sneaked in and the caretaker was nice enough to let us see the model.

HW: That’s really nice. The problem is that they’re a bit fussy about outsiders. It’s a dance hall. And there are a lot of paedophiles walking in the streets, as you know there are a lot of little girls walking around in their butterfly dresses. And they have had a couple of incidents where people have just walked in and asked odd questions, so the Chairperson is a little cautious to let people into the compounds. And so, the safety of the students is very important, they’re only 5-6 years old. People have come in and said they wanted to make a donation and asked if we could give them some girls for an event. You know, things like that – which all sounds a bit odd. But that’s the problem.

ZA: That building was done 10 years ago now?

HW: Yes, it was and we’re looking to begin the next phase of the building. The next important part is to get the theatre up and

Neelung Arts Centre by HWAstage is in front of the big square where you see this small grass patch. The idea was to have a big door like a huge shutter that is in between the stage and theatre, so sometimes they do rehearsals. I wanted that activity to connect to the street. I feel like people have the knowledge of the arts, when things are going on, we of course engaged with it. We are blessed with that ability. But there are so many people at another level of our society who will never have the opportunity to engage with the arts. So, I wanted people on the street who will, never ever, think of classical music, nor think of dance, I wanted them to hear it, and listen to it and see it. So, when you make contact with that, that will create their curiosity and perhaps it will change their lives in some way. Our notion of the arts came from village culture, traditionally we have never danced in theatres and these kinds of open spaces. So, creating the whole culture of cultural activity that changes you. It must be accessible to more people. Your experience of life becomes different because of that. I am very interested in

getting a second part of the building.

ZA: We were just at Lununganga two days ago and we were walking down the garden, and you could hear the village nearby, they were having a gathering and they were dancing and singing. So that was how they did as I understood from the caretaker over there was mentioning. The pavilion was very near Lunnuganga and you could hear the drums. So, there was this serendipitous public private connection.

HW: The way I read Geoffrey’s work is that it has a kind of feudal character about it. Because he’s from a, probably one or two generations before us and that was the feudal era. And then there was the independence and some search of national identity. But that kind of feudal attitude is very much there when you study his work. Channa Daswatte once told me an interesting story about Lunnuganga where he could sit in the verandah and he sees the pot and from there he also sees the temple. So, from there, he said okay I will get it painted. So, he paid the money to the temple to paint half of the stupah and the other half was left unpainted. And then they had said, Channa and all his students told him you can’t do this. It was a village temple and you couldn’t do it. But I think, he thought that maybe there wasn’t anything wrong with the way he thought because he was very much embedded in that era, and that was how anyone from that generation had thought. I mean my parents were like that, because its very hard for them to change from that. Its like a very structured class and society, and that’s how you looked at life. So, there’s nothing wrong with him saying it, but I think it’s very important part of understanding his work. I mean the parliament for instance, it’s like a medieval palace and built in a democratic era, what a huge contradiction is that.

ZA: So how has this architecture legacy informed your work, has it affected it, do you borrow it?

HW: Oh yes, I think that kind of feel of histories is embedded in the way you work. There was a very strong kind of nationalistic movement before us and them, it kind of became a kind of kitsch architecture, people were using

Neelung Arts Centre by HWAthese kind of wood columns and old verandas, but the actual meaning of it got lost somewhere and it just became fashionable symbols. I kind of reacted to that, I felt that it was in some way trivializing our work. Do you want to have a cup of tea?

ZA: Only if you have it with me. (rings for a cup of tea)

HW: So I think the part of symbols I wanted to avoid, because that had become a kind of kitsch element in our architecture but I mean like if you look at my work, most of them have courtyards, so the kind of plan form is borrowed. But of course, the way that I have incorporate these courtyards are different from a traditional building. Now this is 6m wide and 30m long (points beyond her office to the perimeter of her house). So then you can’t have the typical courtyard of an aristocratic house which they used to build, because then courtyards were 30 ft by 30ft, and you could have these beautiful verandas and what not. So now plots have become so small, so this building is two courtyards, there’s a tall one here and a short one here. (points to her house layout) Kind of a stepped courtyard thing, so I’m using the same thing but in a dif -

ferent way. Because it has to fit in our current lifestyle of our current society. That you need to relate your work to the way people live now. You can’t say “Oh you are Sri Lankan, you must build with an old roof and the old wooden columns. That is why I’m very against these recycled building parts, because that has become a commodity and that has created a huge problem, because a lot of the old buildings are being recycled for parts into buildings in the city. So, the architecture becomes columns and borrowed elements which are not part of the building anymore, because people are selling them as pieces. I think I do relate to history, but I’m very conscious of replicating elements in a kind of meaningless way.

ZA: In an attempt to read your work, at the Neelung Arts Centre there was this interesting moment where you see the collection of the rainwater into the vase and then you see that against the backdrop of this concrete columns or footers that come up and interface with the timber structure. So even though it wasn’t a vernacular use of old wooden columns or these kinds now kitsch elements, it still read in the same ethos in how things came together. It was a contemporary way of interpreting the method as oppose to replication of elements.

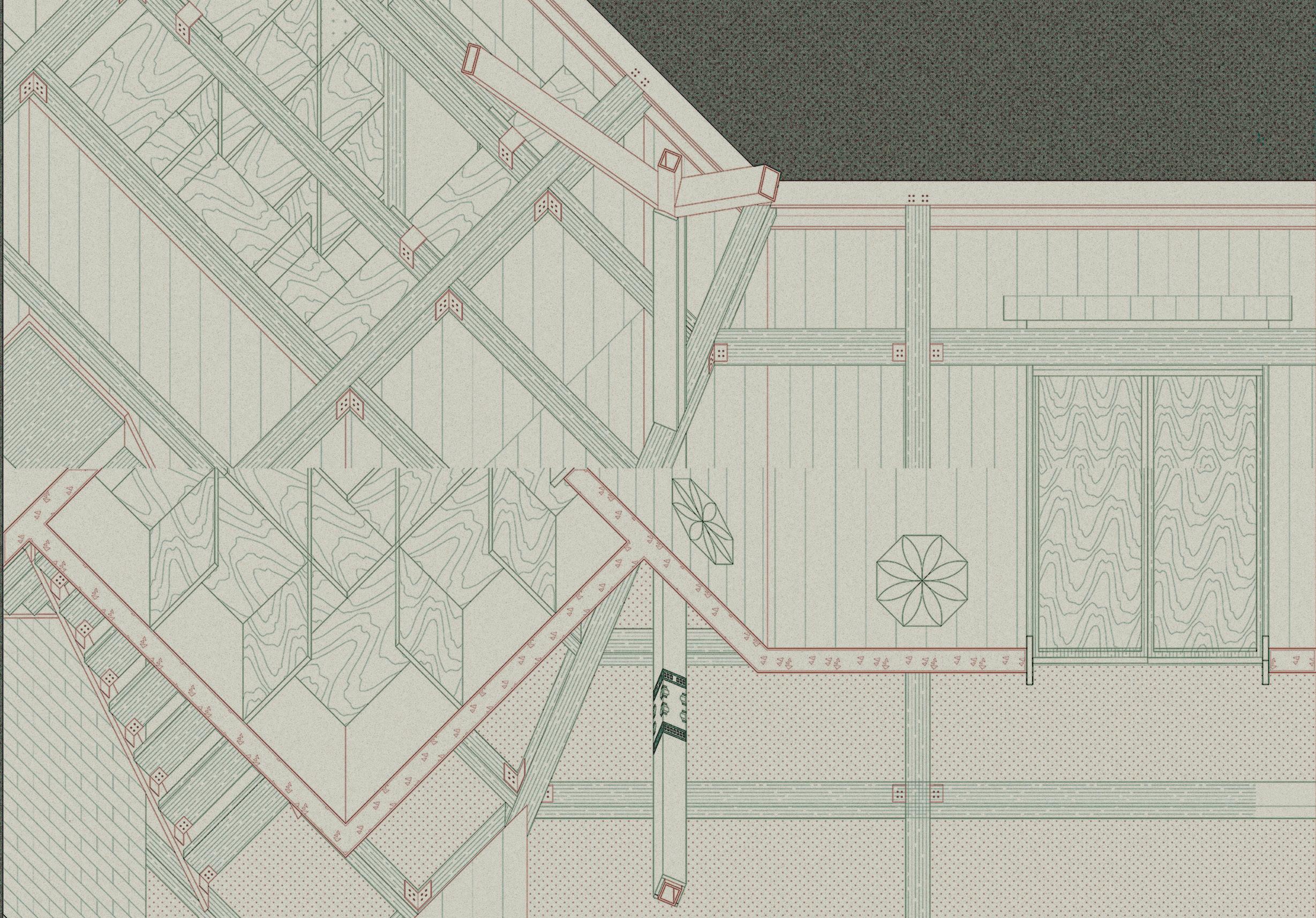

Neelung Arts Centre by HWAHW: That’s really interesting way to look at it. One of the key things was the timber truss structure, because the chairperson of the Neelung Arts Centre trust was very interested in that. So our trusses are actually made out of cheap timber sections, which are called 4 x 2s. And that’s what you do when people do windows. So, by using things which are economical readily available, we were able to use a sustainable material like timber and all the cost of the building. The entire structure was actually designed by the architect and we gave the engineer this drawing. And if there were to be something wrong they would modify it. The interesting part is that they said, no, this works! So I think it’s really important for architects to think of the building as a structure, all those things have to kind of come together, then it forms a really nice relationship.

ZA: Where were you trained?

HW: I was trained by a brilliant architect, Balakrishnan Doshi. So, he was the examiner for me and another colleague of mine for our third-year project. He was the examiner for our third-year project. He had told both of

us to come and work for him at his office, as trainees. Actually, at that time, we were a little vague about the whole design process. I think going to Doshi’s office really helps. There was this huge drawing of one to one of the windows of IIM Bangalore which he was working on at that time, that kind of engagement of detail and spaces, we haven’t seen it anywhere in Sri Lanka. Also living in Ahmedabad, seeing Corbusier’s works, seeing Kahn’s work. We used to cycle every day going into Louis Kahn’s building on the way to work. That one year I was there, really changed the way I looked at architecture. So, we came back completely transformed.

ZA: And after that shortly, you came back to Sri Lanka, and started practicing as your own firm?

HW: No, we still had school, so we finished two more years. So, after five years, I went to do a Masters in Helsinki at the Alvar Aalto university. I’ve been really lucky to study in two great architecture cities. I mean if you think Ahmedabad in India, and Helsinki and being part of the Alvar Aalto university as a

IIT Ahmedabad by Louis Kahnstudent really kind of gives you a different sensibility. The thing is with architecture its like wine which matures over the years you know. Sometimes some small detail which you saw long ago lies somewhere deep inside – its like a seed. Then it slowly grows and suddenly you think about something and you think, “Oh my god, yes, Alvar Aalto, the space and like those things click for you.

ZA: It always seems like perpetual retrospect, where you look back and think “Hey, that’s not bad?”

HW: Yes! For me I feel like it would be very hard for me as a student to produce a really brilliant building. I think that ideas need to be inside you for a long time, and that is why you’re in contact with it, but the real consequence only dawns on you maybe 10 years later. Yes, so I think that Doshi and Helsinki is really important.

ZA: The reason why I came to Sri Lanka, is because I’m doing my final year thesis. It looks at the domain of craft, climate and capital in the architectural production in Sri Lanka. Therefore, I was curious to see how on the one hand there this rich architectural legacy, to put a sweeping statement, say tropical modernism, though I suspect there’s more to that. On the other hand you have the development of the city or the metropole, especially with the Chinese investments coming in with the port city. It would be of interest to see how these two come together in a way, does one react to the other or is it just a superimposition of the generic city unto Sri Lanka. Do you think there is room to wriggle, or resist these kinds of tall curtain wall, steel framed full height glazing towers?

HW: That is a problem. I think its not only here, but all over the world. Because development is carried 75% by the developers and developers are looking at the cheapest option, they’re not looking at the best option. Especially at that time where economy was kind of taking off, if the economy is at a different level, maybe the expenditure may be a little higher, or people will be looking at qualitative things. Right now, in the history of Colombo, people are more obsessed with quantity than quality. But that is a part of capitalism, all over the world. These capitalist economies have shifted

the value system and there is an over emphasis on – when people talk they talk about how much floor area, everything is about quantity. No one will ask about quality. The group of people who want a quality driven approach is very small. The architects are working with this group. The rest of the 75-80% of the work is done by developers, with their own in-house staff. They are doing buildings, but not necessarily architecture.

ZA: During a conversation with Milinda Pathiraja earlier this week, I asked him about the development climate in Sri Lanka. He says that there are 4 major types of buildings – one was the architecture of the public, the government offices, state offices, and on the other hand you have the kind of slum, housing, where most of the population would stay, followed by a third one which are the affluence driven private residences. Within that, do architects choose, or do they try to move across?

HW: We should try to move across, but the opportunity for that is very little. Because government projects, we don’t have enough competitions – and there again they’re only looking at quantity instead of architectural quality. This is highly disappointing because important public buildings are done by the government. If architects can’t engage with that, it’s a problem for the city. I mean we are doing some apartments, that’s a kind of offbeat type of client, who still wants development but also quality. But all the mega projects are not like that, all these projects are from architects from the outside. All these architects are also the ones who are producing, buildings from cookie cutter – they all want to building quantities.

ZA: Even if in the context of Singapore, an interesting architect from overseas comes in, its not because of quality, but rather the chance for marketing or branding, to increase the value of the building. It is all subservient to the kind of capitalist modes of production.

HW: I think that is a global problem, that is kind of affecting all architects. I mean look at Donald Trump, and the whole business group. Their value system is completely different. People who think that culture is important is a highly marginalised group in every country. I think a good example is the United States now – everything is so crass, politics, business. It’s a global problem of our times. I don’t think

architects can change that, it is too huge of an avalanche – the money ball is rolling. Everyone is profit, profit and profit. What is the maximum you can make out of it? Of course, there are people who try to work with this and operate in a different way. We need somehow to tap in.

ZA: It was really an eye opener to see on the first day the city growing right before your very eyes, you don’t see it in Singapore because the towers are already there and have been for a long time. Colombo seems to be at an interesting moment of spring boarding into development. You see Chinese construction sites placing their posters across the city, Chinese characters or Mandarin starts to sit beside Sinhalese characters.

HW: There are a lot of Chinese people living along this road (refers to the common road outside her house) They have businesses here and are renting these houses out. So, the city is not growing in the right direction, unfortunately the government hasn’t been able to capitalise on it favourably. If they had looked at public spaces and properly guiding development, and the whole question of high-rise buildings, where they should be. I tried to make a case, because the port city is coming up, I was working for the government as a consultant for city development. I suggested in a proposal to conserve Fort and Pettah as an entity like a conserved city and let all the towers happen in the other areas. At this moment, no one is really interested in creating legislation for that.

ZA: At the moment the towers, don’t seem to be concentrated at any given area, but rather you would see one pop out right beside a shophouse. Is there a zoning strategy happening?

HW: We had a zoning plan a long time ago but now it collapsed, because there is a kind of loophole in the regulation where if you are in a certain investment bracket and a plot size, you can renegotiate your terms. Even conservation is a big fight, right now the city is fighting to preserve slave island, but one of the developers one building. The next one is already getting ready to do it. So that is a real problem.

Hirante Welandawe is a registered Sri Lankan Architect and practices under Hirante Welandawe Architects.

We had first scheduled to meet with Milinda the day before, but to our dismay, we had gotten the dates wrong. On the right day of the meeting we had split up, Kate was off to Kandalama to see Laki and Zul went to speak to Milinda.

MP:What’s your program here?

ZA: Kate and I are interested in Sri Lanka as a site of choice for our architectural thesis. We’re both final year students at NUS. She’s looking at different elements in Sri Lankan architecture, looking at the tropical tropes, the column the big roof, as a kind of series of elements. My personal interest is in the modes and the methods of producing architecture, how materials come together, how its being built – examining a very specific way of building in Sri Lanka, as opposed to what we see right now near the port city, these steel and glass skyscrapers. So there are these kinds of opposing forces.

MP: So your study is about the forces and the process, and how things are put together? But how we put things together in a very specific place, and a very specific industry and how to work with the constraints and limitations of that place. I think its an interesting question. I personally feel that every project has its own context and when I say context, in other words – the physical context the landscape and what not, but also there’s the social part, the economic part, there’s a cultural context etc. So ideally each project should be different from each other because there is different situations. I think if you may have realised that Singapore is abit like us sometimes, if you would have to summarise this place into one sentence, I would say that this is a place of extremes.

You have, a beautiful landscape, the plantations and so on, but that is also existing in juxtaposition with the city full of glass and steel elements. So we have a history which runs up to 2500 years, but at the same time the history has always been bloodied by civil wars. If you look at the city there are these private gated residences that are done in certain ways, and you have business operating out of lets say

more informal settings. So when you say Sri Lanka, it is very hard to construct a collective image of what that is. You have many Sri Lanka’s within one Sri Lanka. I think that is typical of us. So I’ve been practicing in Sri Lanka for about 6 years now. In that time, the kind of work that we do, we realised every project is different. I was trained in Melbourne, we had this kind of design process which was linear. More or less, it is one way of making architecture, no there are variations in that, through sketch design, detail design – all these RIBA guidelines. But here, this is not the case since everyone is designing very differently all the time.

So I think for me, since you are asking about the process, it is very hard to define one singular process. Usually as architects we try to define our niche and our way of working, the problem is, once we start to do that, we get confined to a particular way of doing work. There are architects who do some very nice houses, whereas there are others who do very nice high rises. Geoffrey Bawa himself has done some nice projects. The problem is when you go to the other end of society, buildings like housing, schools, police stations – there is very little architecture, because there, we cannot apply that process. We always don’t get the business, because to execute certain architectural intents, you would skilled carpenter or stone mason – so there is a serious issue of labour. So I think the first thing I’d like to tell you, and this is something we have been trying to do for a long time, is can an architect engage with that kind of process, where there is so much diversity in economic-socio and cultural situations. We like to use this term of robustness, as a strategy to have the capacity to adapt and be flexible.

I feel that if an architect wants to travel across the market, and dabble in different types of worlds, your design needs to be able to change and adaptable but also the process. We are building an office building in the city now, and we went through the standard process of submission drawings and tender

Ambepussa Library by RAWprocess and everything that changes has a variation – this is perhaps how its being done in Singapore and even Melbourne. Then at the same time, we are doing this school project, where we didn’t do any drawings, because they can’t read drawings. The building is built by the parents of the school children, and they are essentially farmers. So we just worked on a few very rough sketches, and everything else is verbally communicated. So this shows the two extremes, but in between that there are so many other ways of this happening. But in this process, what we realised is that if you were to choose a position to travel across these different scenarios of operating, then your process needs to malleable.

Your drawings need to change, because the production of drawing – the purpose is to communicate the information to the people who build. So the capacity of the people who build and the capacity of the client to understand your drawing is very different. That is the first thing. It doesn’t mean that every architect has to do that. I think the practice is often a reflection of yourself and what you want to do in life and your positions about society.

So if you want to have a practice that does offices very well, or private house very well, then you could have just one way of practice and there is a market for that. The challenge is when you suddenly want to travel across, how you deal with questions of resources, materials, labour and capital. If in Colombo, I have a client who wants to build an office, I can have a wider palate of materials and can access better skilled workers. If I go to a village, where they are limited in materials, skilled labour and minimal capital. So how we organise the resources there, we have to organise it differently from elsewhere. I like to see this as an opportunity, to do something different.

For example, I’ll use the example of WOHA. If you look at the body of work, they have done different types of project, I have been to the chapel and I have been to the high rise – and they are different programs, different buildings, different clients but perhaps the

process would have been more or less the same, I assume. But here, if you do that for example if you do housing, you have to engage the state builder and so on. If you build a chapel, it’s a different organisation.

ZA: Is this is a primary challenge for many local practitioners here? To take the kind of process which have been well established an taught in architecture school, from what I hear is a more sensitive and careful approach towards making buildings as oppose to operating withing the rigors of the metropole. I was speaking with Palinda about this, and he mentioned that he is always open for making a building within that domain but he will nonetheless be uncompromising in his ways of doing things. To me that was interesting, because that raises questions between approach and scale.

MP: Yes, that is why I would be inclined to change my ways to accommodate a different context. I feel that work should have a broader socio-political project. If I feel like there is an opportunity to have a contribution at a broader level, I would rather try to do that. That is where I feel that our process of design has to be broader, robust and flexible because of that. There is a danger to fall in the trap of being defined, especially in a place like Sri Lanka –there are certain areas that you may not be able to fit into. Perhaps that is a larger problem in architecture in general, because only a small portion of buildings are being designed by architects. You are talking about change in the city, the scale of the metropole – if we don’t get involved, you can’t make a statement. The way we have been taught and practice and the

realities of the city are now world’s apart. I will share with you some of the work that we have done, to show you we have tried to tackle this. At the moment I do a design studio at the EPFL on a part time basis, from September to December.

Milinda Pathiraja is a registered Sri Lankan architect and practices under Robust Architecture Workshop (RAW)1. Scriver, Peter, and Vikramaditya Prakash. Colonial Modernities: Building, Dwelling and Architecture in British India and Ceylon. London: Routledge, 2007.

2. Robertson, Seonaid Mairi. Craft and Contemporary Culture. London: G.G. Harrap, 1962.

3. Risatti, Howard. A Theory of Craft: Function and Aesthetic Expression. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

4. Jain, Bijoy, and Joseph Van Der. Steen. Studio Mumbai: Praxis = Sutajio Munbai: Purakushisu. Tokyo, Japan: TOTO Pub., 2012.

5. Yanagi, Sōetsu, and Bernard Leach. The Unknown Craftsman: A Japanese Insight into Beauty. New York: Kodansha USA, 2013.

6. Pallasmaa, Juhani. The Thinking Hand Existential and Embodied Wisdom in Architecture. Chichester: Wiley, 2015.

7. Piketty, Thomas, and Arthur Goldhammer. Capital in the Twenty-first Century. London: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2017.

8. Jones, Robin. “British Interventions in the Traditional Crafts of Ceylon (Sri Lanka), <I>c</I>. 1850–1930.” The Journal of Modern Craft 1, no. 3 (2008): 383–404. doi:10.2752/174967808X379443.

9. “Lanka Worries about Indian ‘Trojan Horse’.” Daily Mirror - Sri Lanka Latest Breaking News and Headlines. February 10, 2017. Accessed November 26, 2018. http://www.dailymirror.lk/article/Lanka-worries-about-Indian-Trojan-Horse--123627.html.

10. Shantakumar, B. “Is Pakistan Falling into China’s Debt Trap?” CADTM. Accessed November 26, 2018. http://www.cadtm.org/spip.php?page=imprimer&id_article=8294.

11. Dreyer, Edward L. Zheng He China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty, 14051433. New York: Pearson Longman, 2010.

12. David, Kumar. “When The Treasure Fleet Sailed Into Galle.” Colombo Telegraph. November 19, 2013. Accessed November 26, 2018. https://www.colombotelegraph.com/index. php/when-the-treasure-fleet-sailed-into-galle/.

13. Pieris, Anoma. Architecture and Nationalism in Sri Lanka: The Trouser under the Cloth. S.l.: Routledge, 2017.

14. Robson, David, and Channa Daswatte. “Serendib Serendipity: The Architecture of Geoffrey Bawa.” AA Files, no. 35 (1998): 26-41. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29544087.

15. Jacqueline Sarsby” Alfred Powell: Idealism and Realism in the Cotswolds”, Journal of Design History, Vol. 10, No. 4, pp. 375-397

16. “Chinese Firms Involved in 40% Construction Projects in Sri Lanka: Report - Times of India.” The Times of India. July 01, 2018. Accessed November 26, 2018. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/international-business/chinese-firms-involved-in-40-construction-projects-in-sri-lanka-report/articleshow/64817568.cms.

17. “Sri Lankan Builders Worry over Chinese Influx.” News - GCR. Accessed November 26, 2018. http://www.globalconstructionreview.com/news/sri-lankan-builders-worry-over-chinese-influx/.

Slow Hands Quick Work is an Independent Master Thesis Research completed at the National University of Singapore in fulfilment of Master of Architecture