The guitar in the Río de la Plata region: its origins and its luthiers Uruguay

• Ariel Ameijenda Argentina

• Alexis Parducci

• Diego Contestí

• Mateo Crespi

N° 23 - Spring 2024

English edition

N°23 orfeo

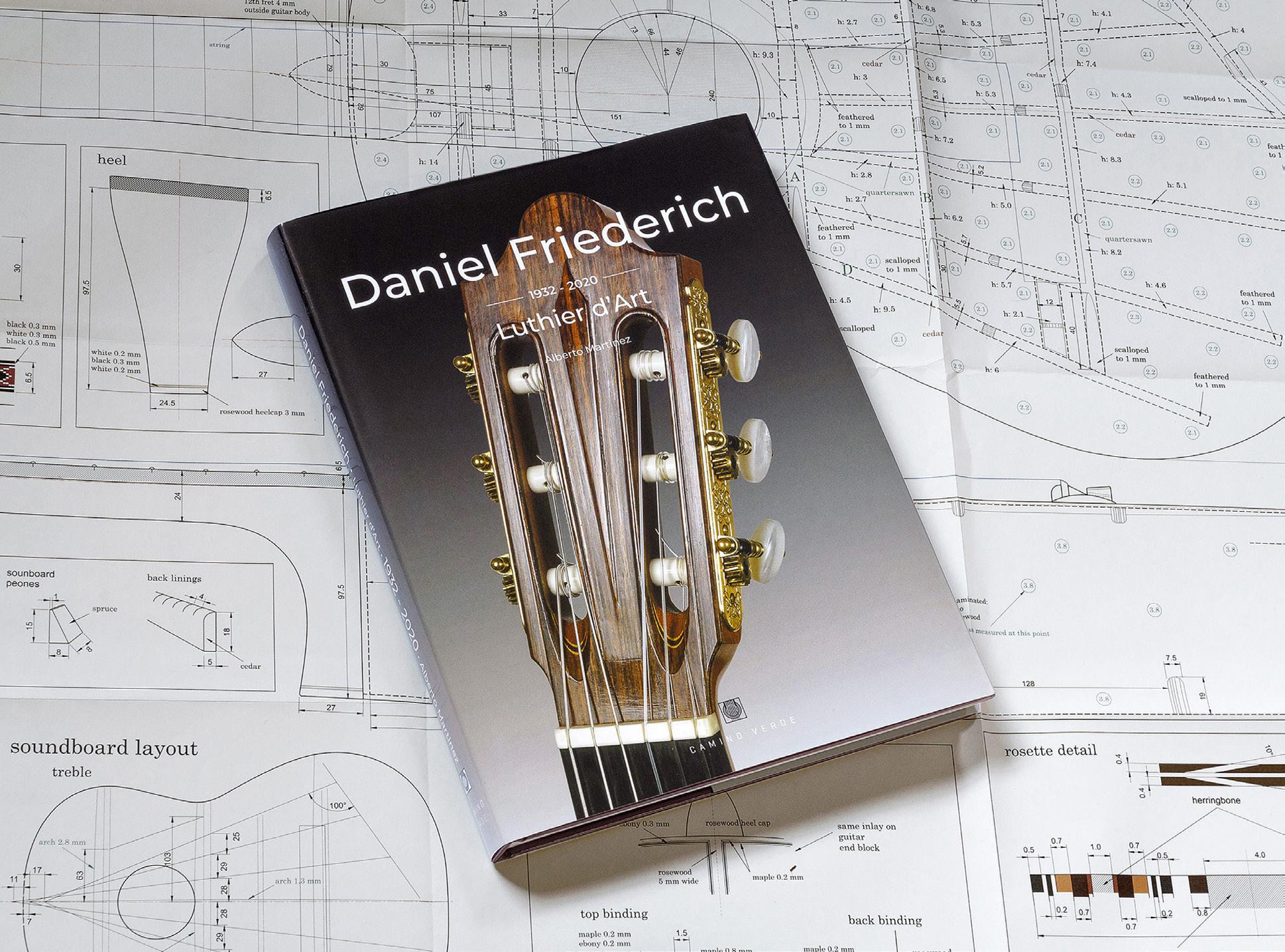

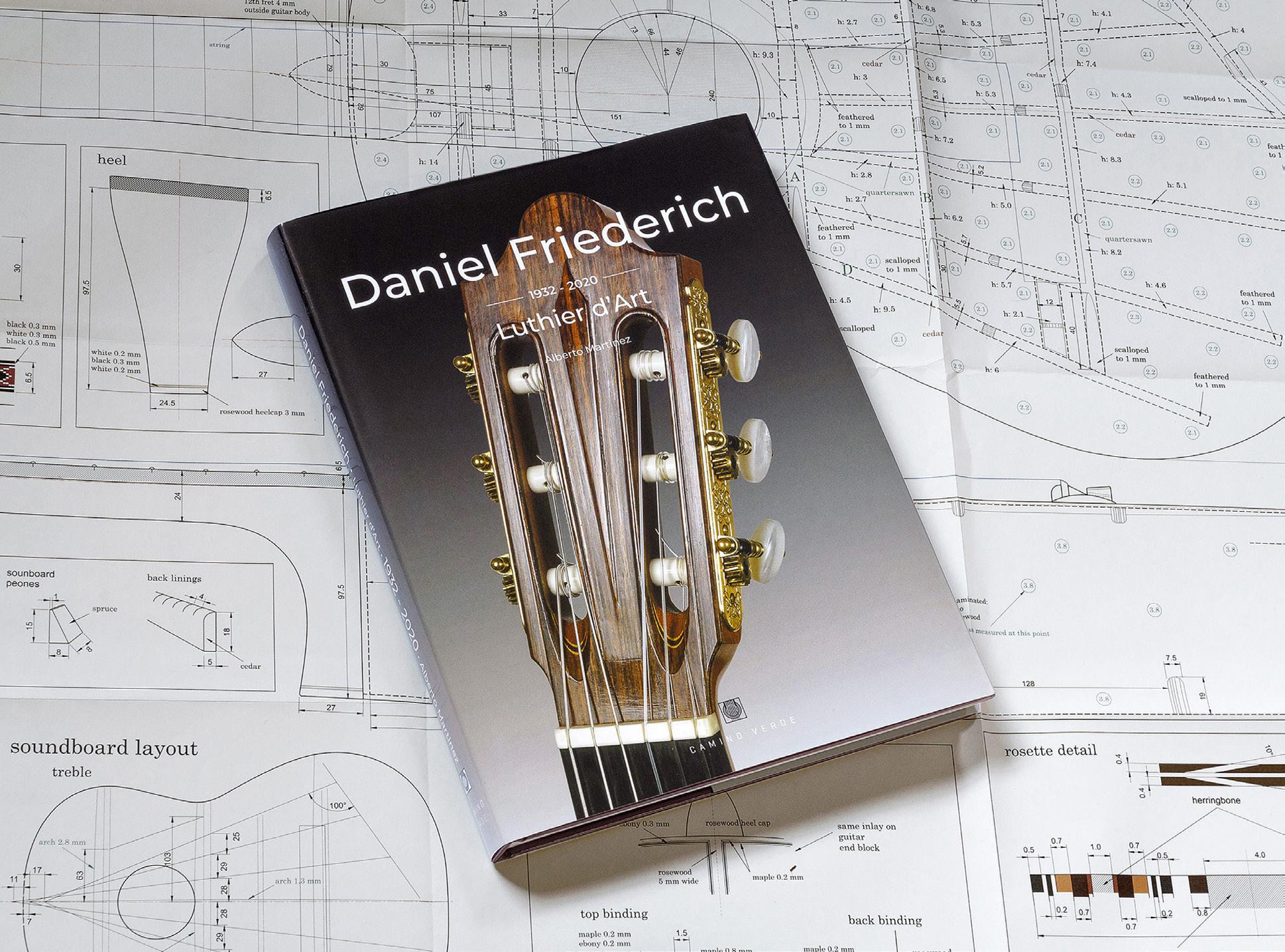

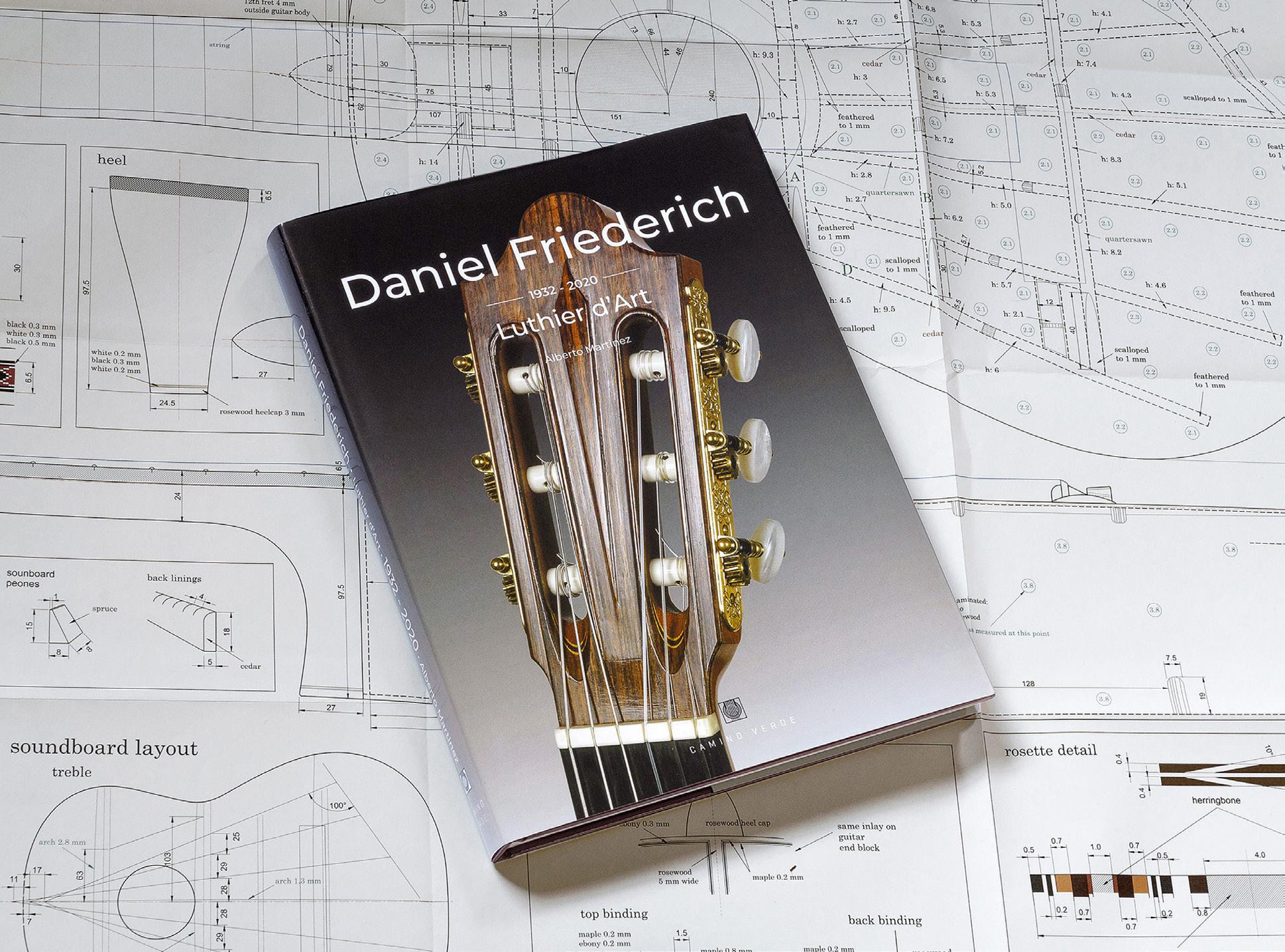

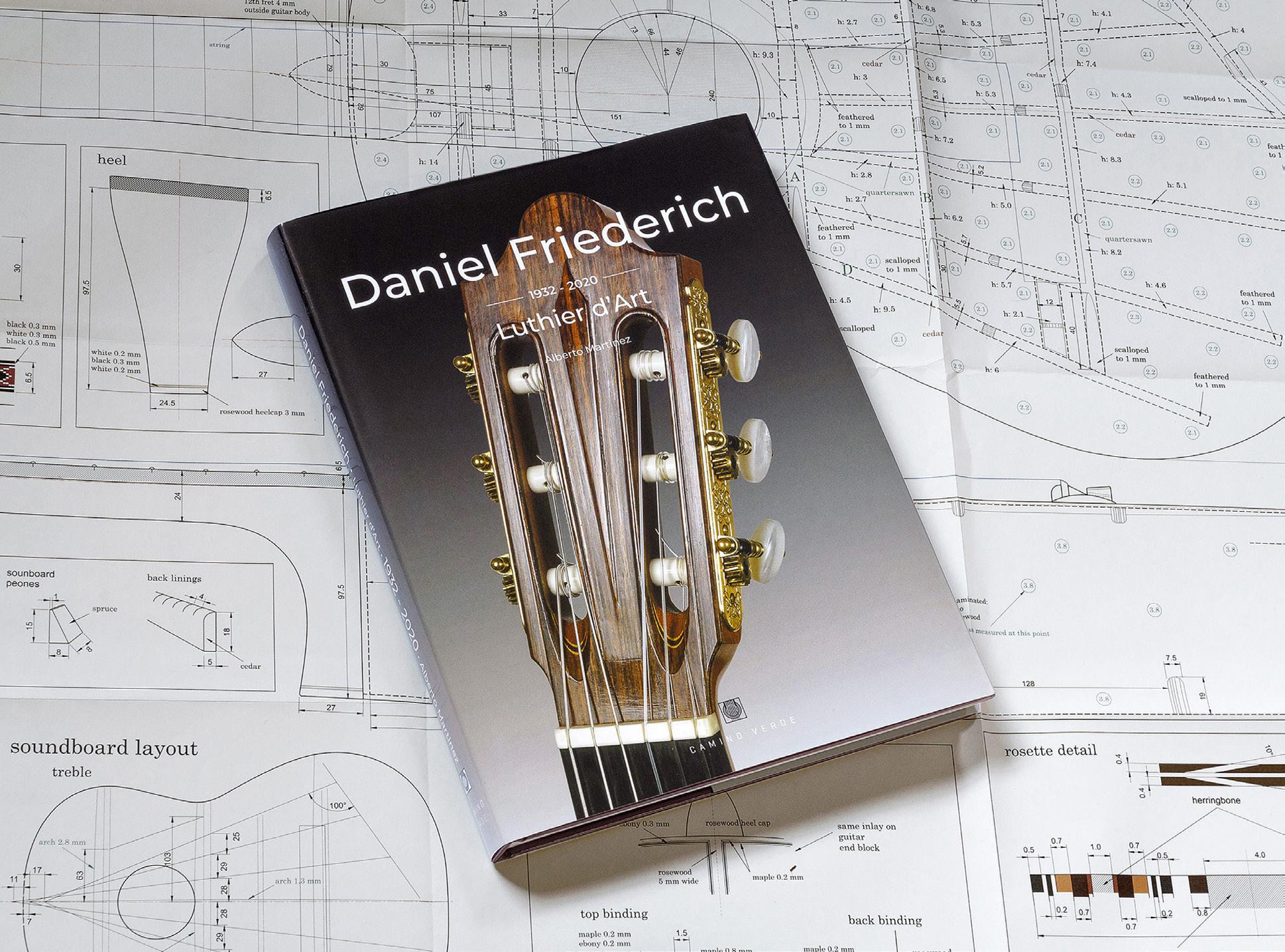

Book size:

22.5 x 30 cm (2 kg) 216 color pages

1 life-size Friederich guitar plan

French/English Price: €90 (France) + shipping

French-Spanish

2

Alberto Martinez

Publishing

© OrfeoMagazine Founder and Publisher:

Art Director: Hervé Ollitraut-Bernard –

assistant: Clémentine Jouffroy

orfeo

order your copy, click on the book below The book on Daniel Friederich is available!

translation: Maria Smith-Parmegiani – French-English translation: Meegan Davis Website: www.orfeomagazine.fr – Contact: orfeo@orfeomagazine.fr www.caminoverde.com

To

From the Editor

orfeo

MAGAZINE

For as long as I can remember, even as a young boy in Montevideo, where I learned my first chords for playing zambas and milongas , I have always had a guitar within reach. And I am no exception. The guitar is ubiquitous in Uruguay and Argentina, being truly the people’s instrument: it’s what makes a house a home.

As chance would have it, in the course of my work as a photographer in Europe, I found myself one day in the workshop of luthier Fritz Ober, in Munich. The encounter triggered a fascination in me: the desire to meet with more luthiers, to share the wonders of their craft and to create Orfeo Magazine was born on that day.

It was therefore quite an emotional journey for me go back to the Río de la Plata basin to meet with luthiers working there. I understand the supply issues that they face with regard to tonewoods and tools, as well as the administrative hurdles and the vagaries of the import business. Against all odds, these passionate luthiers, highly skilled craftsmen all, nonetheless follow a true calling.

One could be forgiven for thinking that Uruguay’s influence on the history of the guitar in the Río de la Plata area might be commensurate with its size: the country is sixteen times smaller than Argentina and its population fourteen times smaller. But don’t let that fool you… Alberto Martinez

N°23

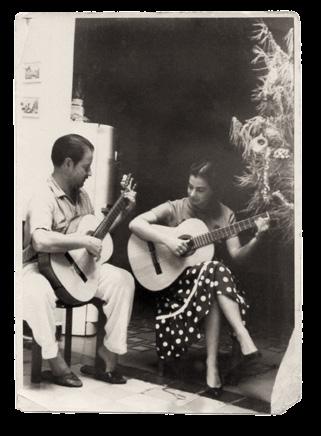

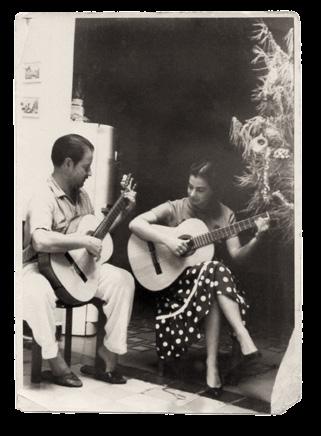

Alberto in Uruguay in the 1960s.

The guitar in the Río

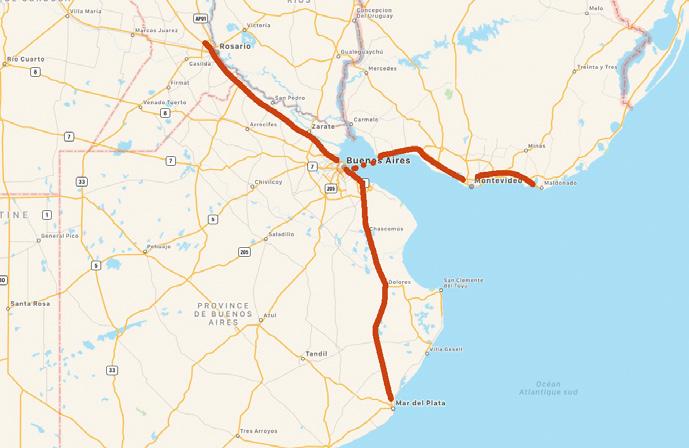

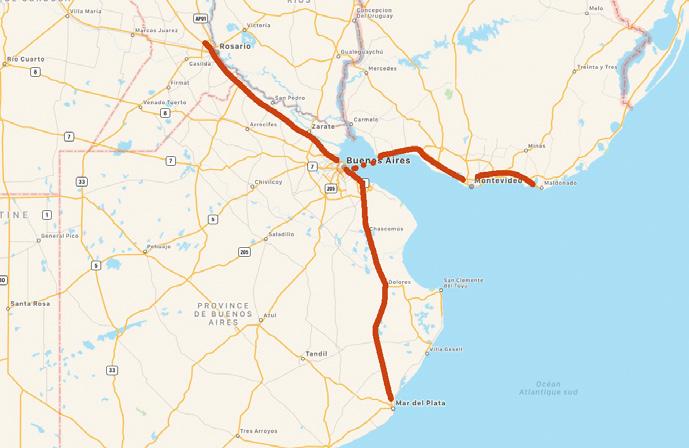

The itinerary, showing our visits to luthiers in Argentine and Uruguay.

Río de la Plata (which translates literally as “River of Silver”) forms a natural border between Argentina and Uruguay. With its two main ports – Buenos Aires to the west and Montevideo to the east – it comprises a vast estuary formed from the confluence of the Paraná and the Uruguay rivers, more than 200 km wide, which empties into the Atlantic. In the late 19th century these twin shores were the birthplace of the tango.

The history of the guitar in the Río de la Plata area stretches back to Christopher Columbus’ discovery of the “New World” in 1492 and the voyages of Amerigo Vespucci. On the planisphere published in 1507 by cartographer Martin Waldseemüller, the first to describe the existence of the new continent, he named it America in Vespucci’s honour. The guitar first arrived in America with the Spanish conquistadors and later with the Jesuits of Río de la Plata.

The Jesuit missions were first established in Córdoba (Argentina)

in 1589, and as of 1607 they spread to areas that are nowadays part of Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay. The Order’s Father General charged the founders with the task of teaching Christian doctrine, reading and singing to the indigenous people. The Guaraní people (native to South America) proved most receptive to music. Ruins of the Jesuit mission in San Ignacio (Argentina).

4

Diego Contestí Buenos Aires

ARGENTINA URUGUAY

Mar del Plata

Piriápolis

Rosario Mateo Crespi

Alexis Parducci Ariel Ameijenda

de la Plata region

They quickly formed musical ensembles and choral groups, and artisans started crafting musical instruments in the mission workshops. These artisans took their inspiration from the various types of old guitars brought by the Spanish colonisers which explains the advent of the cuatro , the tiple and the charango (with tuning inherited from Baroque guitars, with the bass strings in the centre).

Over time, the vihuela lost popularity and was eclipsed by the guitar, which gradually shifted to a six-string configuration, becoming the instrument as we know it today, and incidentally the inseparable accoutrement of the gaucho (cowboy of the pampas).

In 1717 an Italian Jesuit missionary named Domenico Zipoli (1688-1726), who was a musician and composer, arrived in Buenos Aires. His musical and liturgical compositions helped adapt the European Baroque style to vernacular musical tastes. These melodies, whether stemming from dance or song, along with indigenous and African elements, laid the foundations for the region’s musical folklore. This is how rhythms like the zamba , chacarera and malambo came into being.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the guitar seduced the region’s city folk with a rhythm of African influence called “tango” and became the most popular instrument for accompaniments.

5

© Centro de Fotografia de Montevideo

The guitar, faithful companion to the gauchos of the Río de la Plata basin.

The guitar in Argentina

In Argentina, from the gaucho to the boss, everyone played the guitar, unlike in Spain where it was simply a popular instrument. The upper classes of the Río de la Plata also studied guitar.

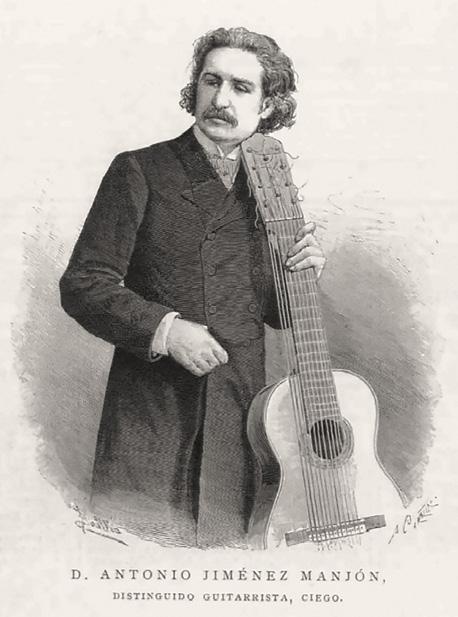

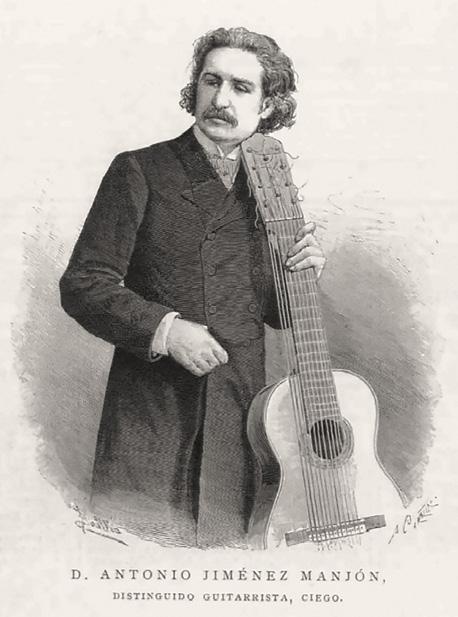

Antonio Jiménez Manjón settled in Buenos Aires in the early twentieth century.

One striking example is José de San Martín, the Argentinian General and statesman who was, along with Simón Bolívar, Bernardo O’Higgins and José Artigas, one of the heroes of South America’s independence movements. It is highly likely that he took guitar lessons, while exiled in France, with none other than Fernando Sor. As the twentieth century dawned, Antonio Jiménez Manjón and Domingo Prat settled in Buenos Aires and, with their guitar methods, laid the pedagogical foundation for guitar study. Later, Miguel Llobet, Emilio Pujol, Agustín Barrios, Andrés Segovia and numerous other eminent guitarists performed concerts and gave classes in Argentina.

NOTABLE IMMIGRANTS AND VISITORS

• Francisco Nuñez moved to Argentina in 1858. This luthier created the largest guitar manufacturing workshop of his time (see separate section).

• Antonio Jiménez Manjón , blind guitarist and composer, travelled to America in 1893, visited Buenos Aires, and went to Chile and Central America before returning to the Argentine capital where he settled permanently. He founded a conservatory, which was subsidised by the Argentinian government at the time, and gave numerous concerts on his eleven-string guitar, which Domingo Prat described as “ongoing demonstrations of art”.

• Domingo Prat settled in Buenos Aires in 1907. He revolutionised guitar teaching with his method and transcribed numerous popular melodies. Over and above his profound influence on the development of the guitar in Argentina, Prat was also behind the success of Enrique García’s guitars and those of his successor, Francisco Simplicio.

• Miguel Llobet came to Argentina in 1910 upon the invitation of Domingo Prat. It was where he gave his first concerts abroad as a soloist and later made recordings with María Luisa Anido.

• José Ramírez Galarreta (José Ramírez II),

6

learned lutherie in the Madrid workshop belonging to his father, José Ramírez I. But he was also a guitarist and in 1904, he headed to Buenos Aires for a two-year tour around South America. The two-year tour, after repeated extensions, ended up lasting nearly twenty years! When the rondalla with which he was travelling split up, he decided to stay on in Buenos Aires. It was there that he met Blanca, a Spanish woman whom he later married and with whom he had two sons: José (later known as José Ramírez III) and Alfredo. In 1923, he learned of his father’s death and decided to return to Madrid with his family. Two years later, he took over the famous guitar shop located in Calle Concepción Jerónima.

• Andrés Segovia visited Buenos Aires several times as of 1920 and lived in Montevideo from the mid-1930s to mid-1940s with his wife, Paquita Madriguera, the former child prodigy pianist. With Segovia, the Spanish and European repertoire greatly developed (see section on Uruguay).

FOLK MUSIC

From 1960 onward, the guitar enjoyed increasing air time on both radio and television. Local folk music artists include: Atahualpa Yupanqui , a poet,

writer, guitarist, composer and singer, who is considered Argentina’s most representative folk performer. He left behind a substantial poetic and musical legacy comprising nearly 1,500 compositions, some of which have become veritable canons of Argentina’s folklore.

Eduardo Falú , guitarist, composer and folk performer, is another key figure of his homeland’s grass-roots music. He penned more than 200 compositions, including the famous Tonada del Viejo Amor and Zamba de la Candelaria .

Cacho Tirao , a guitar virtuoso who performed both in recitals and on television, was renowned for his way of blending tango, folk and popular music.

Just as iconic on Argentina’s musical landscape are the “payadores” , gauchos who, just like minstrels in Europe, would cover vast distances with their ever-present guitar, improvising verse about all manner of current events, politics or philosophical topics.

TANGO

Born in the underprivileged Atahualpa Yupanqui, best-loved symbol of Argentine folk music.

7

Left to right: Miguel Llobet, Emilio Pujol, Juan Carlos Anido with his daughter, María Luisa Anido, and Domingo Prat in 1919.

districts of Buenos Aires, the tango – its music brimming with melancholy and its dance sensual and romantic – was the pastime of the poor and the downtrodden.

The guitar was ever-present in tango, usually as an accompaniment for the singer. Three striking examples spring to mind: guitarist Roberto Grela, singer Carlos Gardel (see separate section) and composer Astor Piazzolla. Piazzolla was not a guitarist; rather, he played the bandoneon. He came to be regarded as a master of tango composition. In this regard, he inspired a whole generation of classical guitarists. His composition studies commenced under the illustrious Alberto Ginastera, and then continued in Paris with Nadia Boulanger. Piazzolla introduced hitherto unknown formal elements to the danced form of the art, giving rise to the Tango Nuevo, an instrumental tango.

8

The famous Café Tortoni in Buenos Aires, where patrons can still enjoy tango performances.

“El Escuadrón de Guitarras”: 12 to 15 guitarists, brought together and led by Abel Fleury in 1938.

CLASSICAL GUITAR

Notable Argentinian composers include:

Abel Fleury (1903-1958), a composer and guitarist whose best-known compositions are Estilo Pampeano and Milongueo del Ayer

Alberto Ginastera (1916-1983), one of the most important Latin American composers of the twentieth century. He left behind major works (operas, symphonies, cantatas and concertos), chamber music, pieces for the piano, as well as four songbooks for vocals.

Jorge Cardoso (1949) is a composer, guitarist and guitar teacher at the Real Conservatorio Superior de Música de Madrid. He has composed more than four hundred works for the solo guitar, for duets (two guitars, guitar and violin, guitar and harpsichord, guitar and flute, guitar and cello), for guitar trios, for quartets (both for four guitars and for string quartets), for quintets (guitar and strings, guitar and wind instruments), twelve concertos for the guitar and orchestra, and for guitar ensembles, as well as countless songs.

On top of these famous names, we should not forget such composers and guitarists as Máximo Diego Pujol and Adrián Politi.

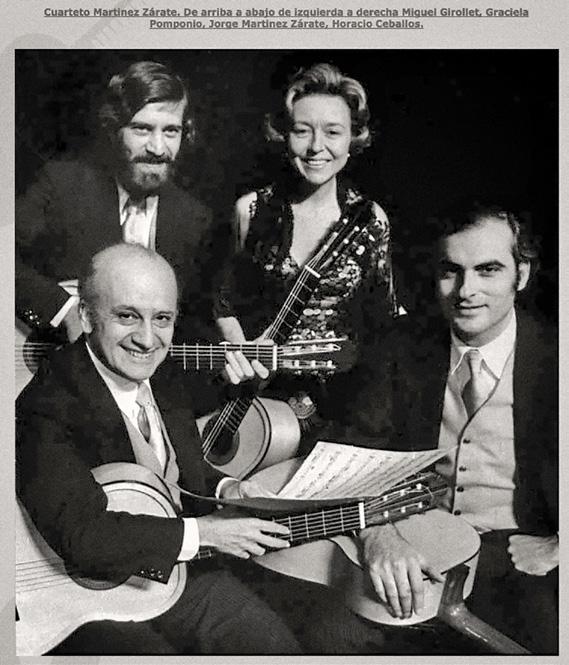

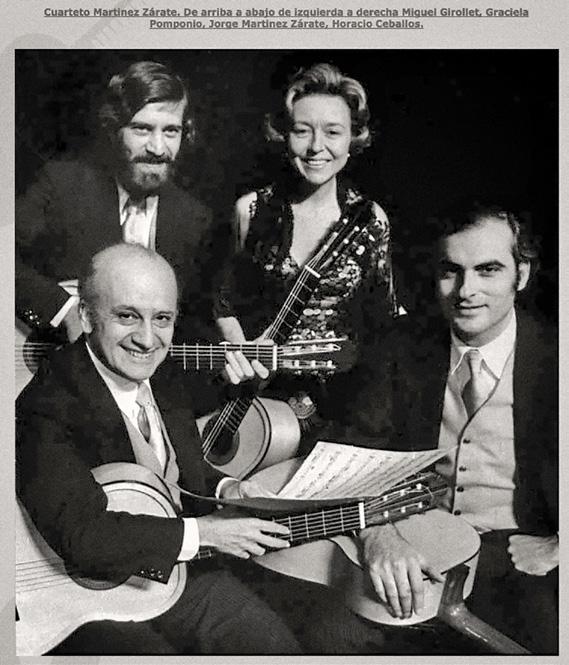

Argentina’s famous guitarists include: María Luisa Anido (1907-1996), guitarist and teacher, trained by Miguel Llobet. She is considered the great dame of the Latin guitar. Her pupils included Graciela Pomponio and Jorge Martínez Zárate, a famous duo who in turn trained a whole generation of brilliant Argentinian guitarists: Roberto Aussel, Ernesto Bitetti, Horacio Ceballos, Eduardo Frasson, Hugo Geller, Miguel Ángel Girollet, Walter Enrique Heinze, Eduardo Isaac, Jorge Labanca, Raúl Maldonado, Pablo Márquez, Enrique Núñez, Osvaldo Parisi…

Ed. – Our deepest thanks to Lucas de Antoni, who taught us much about the history of the guitar in Argentina and allowed us to photograph some historical instruments in his collection.

“THE

RIO DE LA PLATA SCHOOL”

by Roberto Aussel

This is the name given to a modern school of guitar, born on Rio de la Plata’s shores in the 1960s. It encompasses a whole new aesthetics of the guitar and a new approach to studying it, thanks to the work of Jorge Martínez Zárate in Argentina and Abel Carlevaro in Uruguay.

Some of its main features are as follows:

• The instrument’s placement in relation to the player’s body; it is the guitar’s position that adapts to our body and not our body to the guitar.

• Constant care with the placement of the left hand on the guitar neck, so as to avoid any unwanted string noise when shifting from one position to another.

• Greatly varied expressiveness, offering myriad dynamics and colours, thanks to the right-hand technique, with frequent use of an airier fingerstyle – free stroke – while nonetheless alternating with rest stroke, which was predominant in the latter half of the twentieth century.

9

Miguel Ángel Girollet et Graciela Pomponio, Jorge Martínez Zárate et Horacio Ceballos.

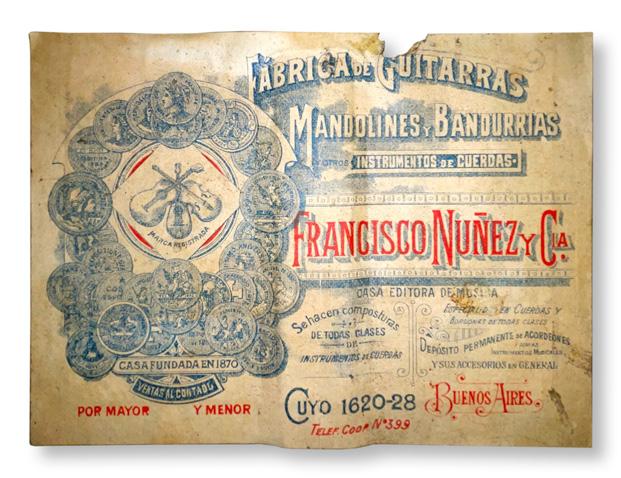

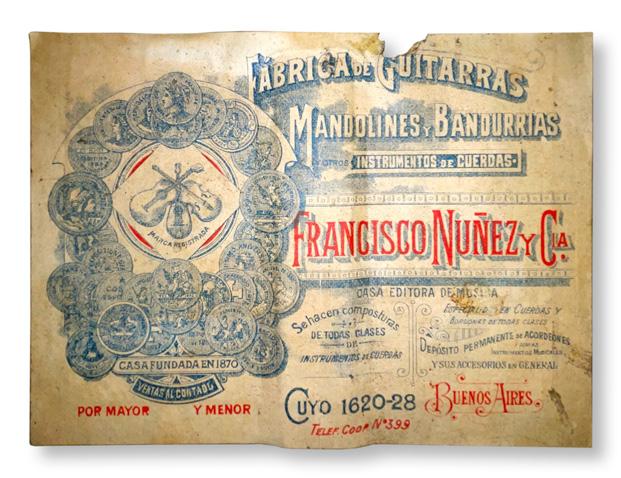

Antigua Casa Nuñez

Francisco Nuñez emigrated from Spain and settled in Buenos Aires in 1858. He learned lutherie with Salvador Ramírez and in 1870 founded a firm called Fábrica de Guitarras Francisco Nuñez y Cía.

In 1894, he went to Europe to procure modern machines so as to massively scale up his guitar production. In just a few years, Francisco Nuñez’s company managed to set itself apart as a serious manufacturer, winning gold medals and awards at international fairs. His annual output – forty thousand guitars – surpassed even that of the guitar-makers in Valencia (Spain).

The enthusiasm for tango, and in particular for singer Carlos Gardel, helped fuel his success with the distinctive guitars adorned with starshaped rosettes.

When Francisco Nuñez died, in 1919, his widow and nephew took over the firm. In 1925, the company name was changed to Antigua Casa Nuñez and, following a fire in the factory in 1926, it relocated to its final – and current – address in 1929: number 1573 Sarmiento.

The brand’s creations include the first doubleback guitars, guitars with an aluminium body and

The historical section of the shop, featuring portraits of Atahualpa Yupanqui and Cacho Tirao and various models of star-rosette guitars.

The same address since 1929.

some using Bakelite: all revolutionary constructions for their time.

Over time, Antigua Casa Nuñez has continued to adapt to the different generations that history has ushered through its doors, to stand proudly as Argentina’s largest and most emblematic guitar-maker, celebrated both nationally and internationally.

A WEALTHY CLIENTELE

Other distinguished guitar shops included Romero y Fernández, Romero y Agromayor and Celestino Fernández, who imported high-quality Spanish guitars, such as those built by Enrique García, Francisco Simplicio, Domingo Esteso and Santos Hernández. This attests to the standard of living enjoyed by amateurs and professionals alike in the Río de la Plata region in the first half of the twentieth century.

The old label, displaying the medals awarded since the firm was founded in 1870.

11

12

Out of the 40,000 guitars that left the workshop floor each year, only a handful were personally made by Francisco Nuñez. This 1910 guitar is one of his most beautiful achievements, crafted to commemorate the centennial of the Argentine Revolution (25 May, 1810).

13

Carlos Gardel’s guitar

This guitar, with its characteristic star-shaped rosette, is an integral part of the image of Carlos Gardel, Argentinian singer, composer and actor (1890-1935), the best-known performer in the history of tango.

Gardel, throughout his entire artistic career, only ever chose guitarists for musical accompaniment and performed with a guitar sporting a mother-of-pearl star design around the soundhole. The first purchase of two guitars of this model stretches back to 1911 or 1912, to the time when the guitarist formed a duo with Uruguayan singer, José Razzano: they both appear in photos with guitars featuring the starshaped rosette.

In September 1925, after having performed together for twelve years, Razzano was forced to stop singing because of an injury to the larynx, and instead began handling the administrative aspects of Gardel’s shows. In photos of Gardel as a solo vocalist, ever-accompanied by guitarists, he clutches the star-rosette guitar to him, as if it were part of his stage persona, and the same is true when he appears in the films Down -

ward Slope (1934), The Tango on Broadway (1934) and El Día que me Quieras (1935).

This particular guitar model was chiefly produced by Casa Nuñez and sold in music stores under various brand names. We also know that Gardel owned not just one, but several guitars of the same model throughout his career.

Carlos Gardel was killed in a plane crash on 24 June 1935 in Medellín, Colombia, and his guitar died with him. The instrument’s twin, the guitar used by José Razzano and bearing a label from the Breyer Hermanos music store (although doubtless manufactured by Casa Nuñez), is the one in the photographs on these pages, which can be seen today on display in the Vicente López y Planes Museum of Argentina’s performance rights association (the Sociedad Argentina de Autores y Compositores de Música, or SADAIC).

14

The José Razzano and Carlos Gardel duo.

There are several versions of this guitar model, with its rosette in the shape of a star, sporting different labels.

Throughout his career, Carlos Gardel had several guitars of the same model.

16

This guitar, the twin sister of Carlos Gardel’s one, belonged to José Razzano.

17

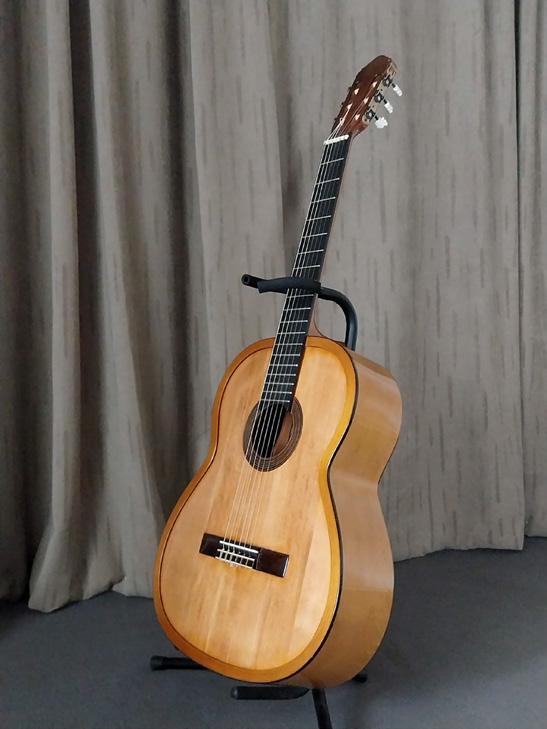

Guitar inspired by the 1958 FE 08 by Antonio de Torres.

Guitar inspired by the 1958 FE 08 by Antonio de Torres.

Argentinian luthiers

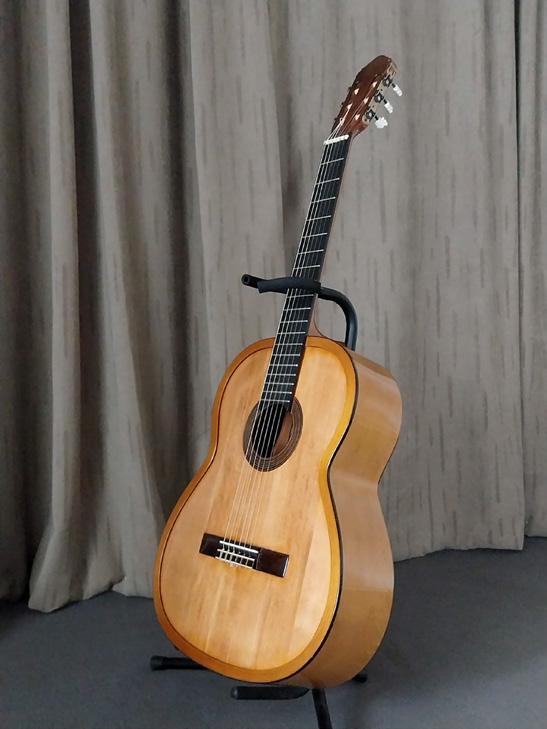

For our discussion on Argentinian luthiers, we have chosen, over and above Francisco Nuñez (see dedicated article), a further six luthiers who exemplify the art in the twentieth century: Galán, Carzoglio, Viudes, Yacopi, Estrada and García.

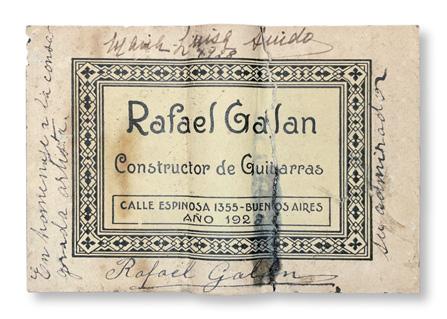

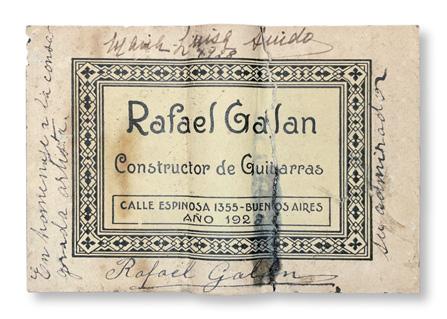

Rafael Galán Rodríguez

Born in Málaga, Spain, he was, along with his brother Juan, the son and pupil of guitar-maker Juan Galán Caro, also hailing from Málaga, who in turn had learned the craft under Antonio Lorca (senior). In 1906, the Galán brothers left Spain and made Buenos Aires their home, experiencing first-hand the guitar’s revival in Argentina as of 1908.

Rafael’s labels read: “Rafael Galán” for guitars that he built himself, and later, “Galán-Velasco” once he went into a partnership with luthier José Velasco.

Luigi Carzoglio

Born in the province of Genoa, Italy, in 1874, this luthier came to Argentina in 1898. His instruments were highly sought-after, not only in Buenos Aires, but also in his native Italy.

Domingo Prat, in his Diccionario de Guitarristas , wrote: “The concert guitars built by Carzoglio are models of excellent manufacture… He stands today as the pride of Argentine lutherie, as his

19

Guitar by Rafael Galán, 1928

“In homage to the famous artist María Luisa Anido”.

He proudly printed on his labels the mention:

Pupil of Manuel Ramírez.

guitars have nothing to envy of even the best ones crafted by the great Torres himself.”

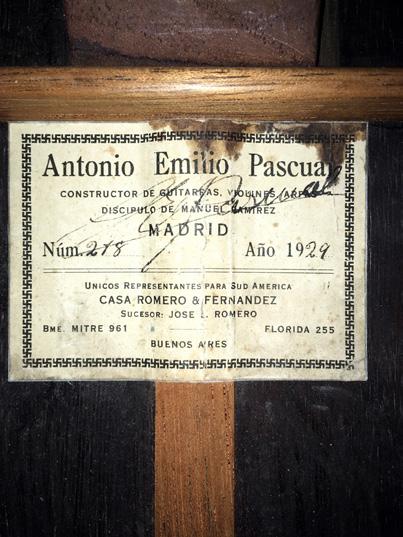

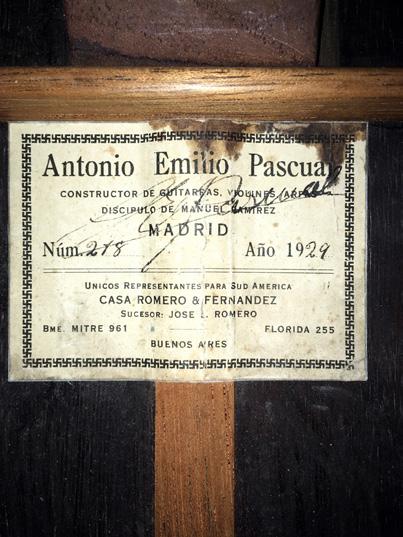

Antonio E. P. Viudes

Born in Alicante, Spain, in 1883, to a family of luthiers. He was sent to Madrid at a very young age to learn lutherie under his uncle, Valentín Viudes. It was there that he met Santos Hernández, a fellow apprentice. He subsequently worked in the workshop of José Ramírez, and then in that of Manuel Ramírez. In these two studios, il met and built guitars with Julián Gómez Ramírez, Enrique García, Domingo Esteso, Modesto Borreguero, Rafael Casana and Santos Hernández.

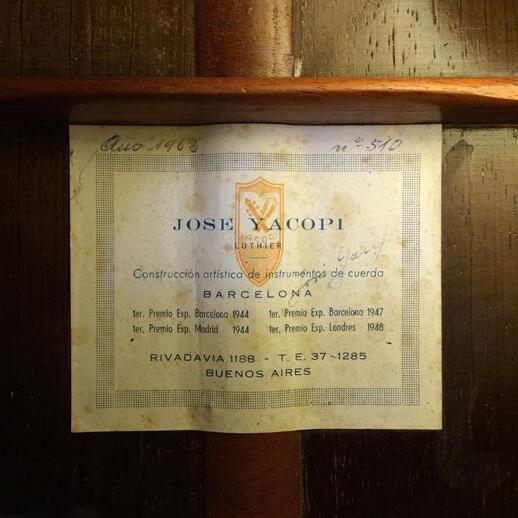

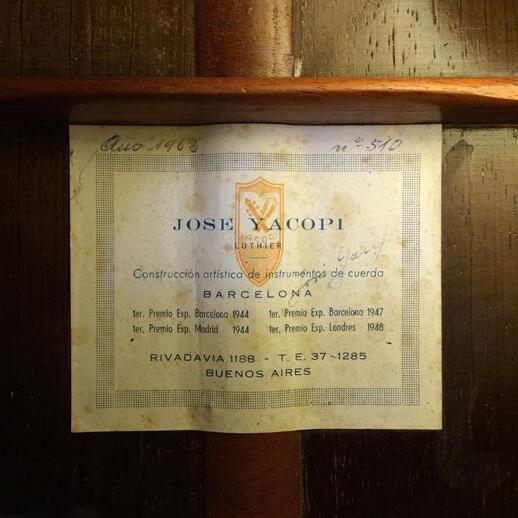

José Yacopi

In 1909, once married, he emigrated to Buenos Aires. He remained faithful to the guitar-making tradition of Antonio de Torres. He signed his labels “Antonio Emilio Pascual”, adding: “Pupil of Manuel Ramírez”.

His guitars featured an inverse sevenstrut fan, splaying out from the end block toward the soundhole.

He was born in the Spanish Basque Country, where the family lived after an initial sojourn in Argentina. From there, they moved to France, before returning to Spain. As a youngster, José Yacopi was a guitarist and studied with several teachers, including Emilio Pujol. In parallel, he learned how to be a luthier with his father, Gamaliel Yacopi.

In 1949, due to wars and shortage of work in

21

“Making a guitar isn’t difficult; the hard part is giving it a soul!”

Francisco Estrada Gómez

Spain, the family decided to return to Argentina, and settled in San Fernando. It was here that José started to earn a living by teaching and building guitars.

One of the features of his guitars is the soundboard bracing that he created in 1947 with his father, using an inverse seven-strut fan, starting at the end block and opening up toward the soundhole.

The workshop grew with the help of his son, Fernando, until it was producing about three hundred guitars annually. Most were student guitars, built by contracted artisans under their supervision, while the concert guitars were made personally by José or by his son.

Francisco Estrada Gómez

Argentinian luthier, indefatigable researcher and creator of his own personal fret distribution, he started out as a luthier in 1953, going only by tips from his father, who was a joiner. His earliest guitars were strongly influenced by those of Enrique García and Francisco Simplicio, each with carved headstock and six-strut asymmetrical fan bracing.

One of his obsessions in guitar-making was accuracy. Dissatisfied with both the conventional fret layout, and the idea of compensating string length solely at the bridge, he came up with a

whole new way of calculating the distances between the frets. He felt that fret spacing ought to offset variations in string length caused by the pressure exerted by the fingers of the guitarist’s left hand.

Joaquín García Fernández

Son of Spanish immigrants, he was born in Santa Cruz, Argentina, in 1929. Two years later his family returned to Spain and at the age of 13 he began an apprenticeship as a cabinetmaker.

In 1949 he left Spain for Argentina, where he worked for a guitar maker. Seeing his woodworking skills, the company’s luthiers encouraged him to learn the trade and in 1952 he built his first guitar. In 1974 he decided to return to Spain and found work with the guitar maker Raimundo. In 1982 he opened his own workshop, first in Torremolinos and then in Málaga.

A tireless researcher, he created a model with a double back and sides to isolate the instrument from the player and achieve better resonance.

22

The double-back and double-sided model by Joaquín García.

Francisco Simplicio’s influence can clearly be seen in the early guitars by Francisco Estrada Gómez. This model is from 1969.

DE LA GUITARRA

In the heart of the pampas of Córdoba (a province in Argentina) stands an impressive grove of trees planted in the shape of a guitar roughly one kilometre in length. It was Graciela, wife of Pedro Ureta, the Estancia’s owner, who came up with the idea of planting trees to create a guitar that would only be visible from the air.

Graciela unfortunately died of an aneurysm, but Pedro was able

to make his wife’s dream come true with the help of their four children.

Construction began in the late 1970s, with the planting of seven thousand trees, of heights ranging between fifteen and twentyfive centimetres at the time. Dark green Californian cypress trees outline the guitar and bluish eucalyptus represent the strings, while pines make up the guitar’s bridge and star-shaped rosette.

24

ESTANCIA

25

The golden age of the Uruguayan

The dizzying heights attained by the art of the soloist guitar is one of the most distinguishing features of Uruguay’s cultural landscape in the late twentieth century. To such an extent that its most outstanding representatives achieved worldwide renown.

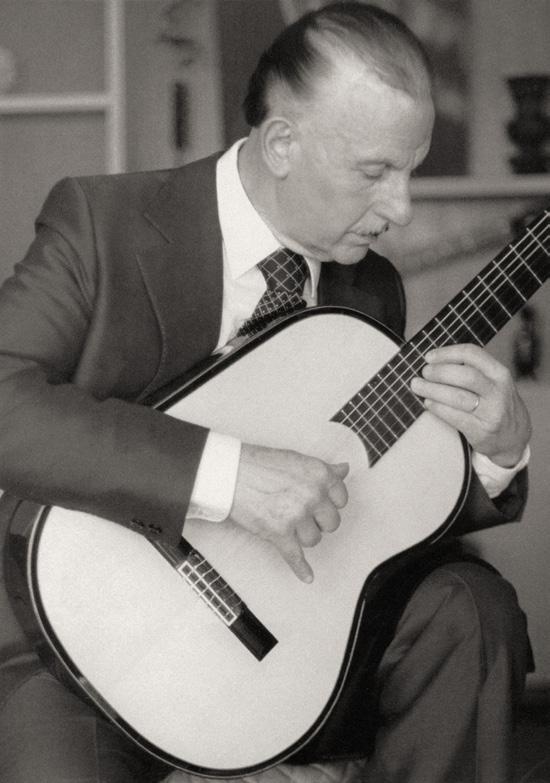

The virtuoso who best embodies our guitar artistry, Abel Carlevaro, revolutionised the playing technique and pedagogy of the instrument, thus becoming an undisputed reference for several generations of guitarists from all corners of the globe.

A little history

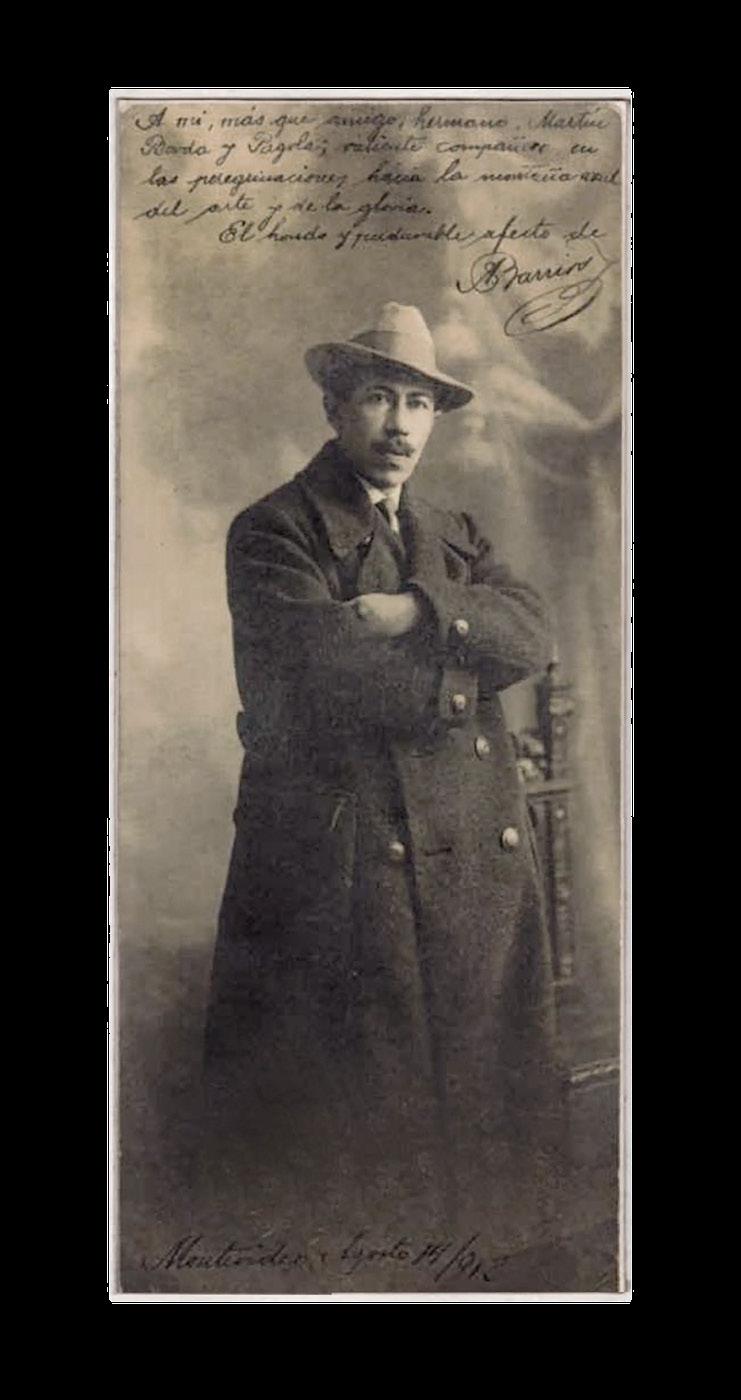

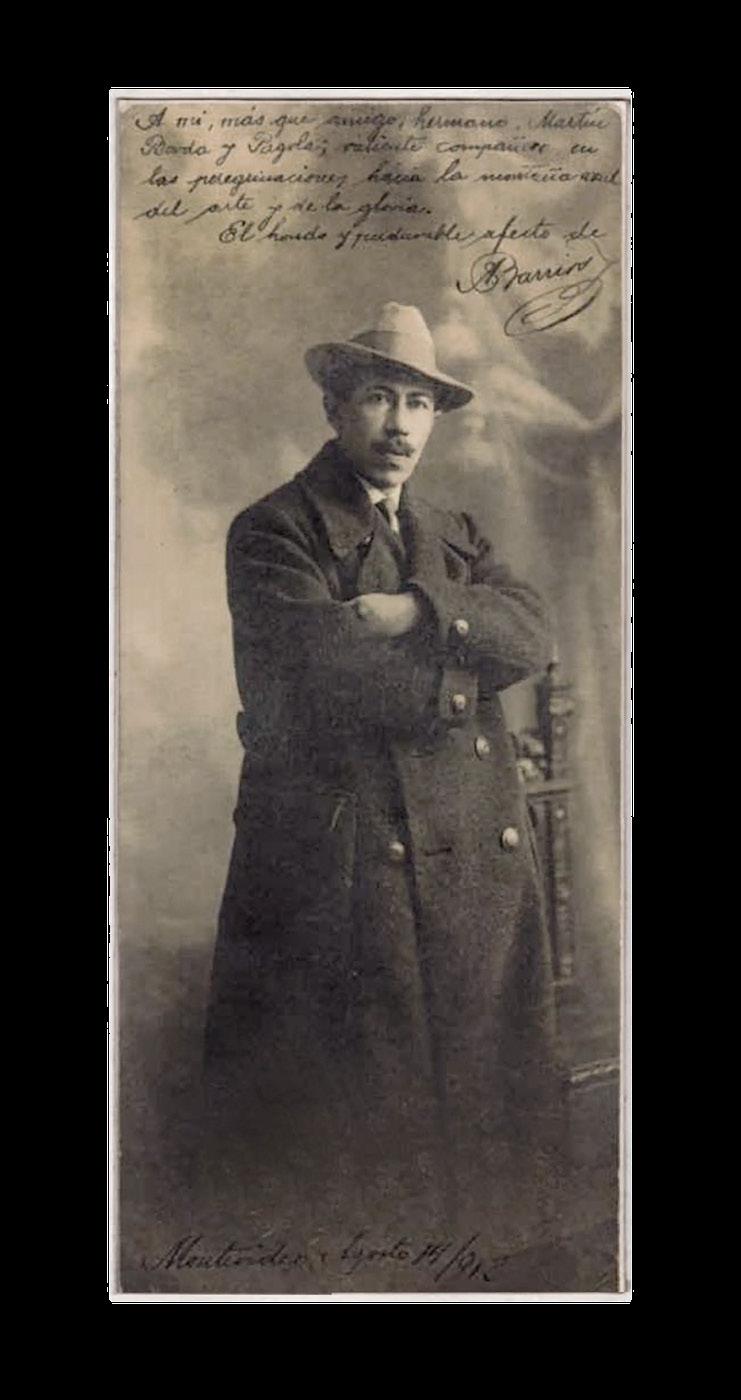

This phenomenon, which peaked in the latter third of the century, did not occur in a vacuum; rather, it grew out of a combination of circumstances that were conducive to its development. Río de la Plata had become, since the late nineteenth century, a magnet for guitarists coming from Spain. Some of the better-known ones were Gaspar Sagreras, Carlos García Tolsa and, in particular, Antonio Jiménez Manjón. These musicians interacted with the local guitarists that they met here, sharing, but also receiving in return, musical elements and techniques. As of 1912, Paraguay’s Agustín Barrios had become a frequent visitor. The gui -

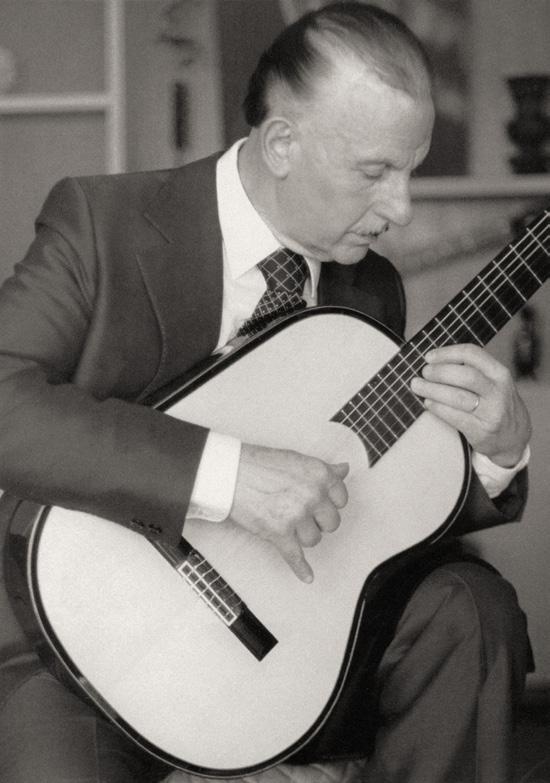

Paquita Madriguera and Andrés Segovia spent about ten years in Montevideo.

26

Uruguayan guitar

by Alfredo Escande

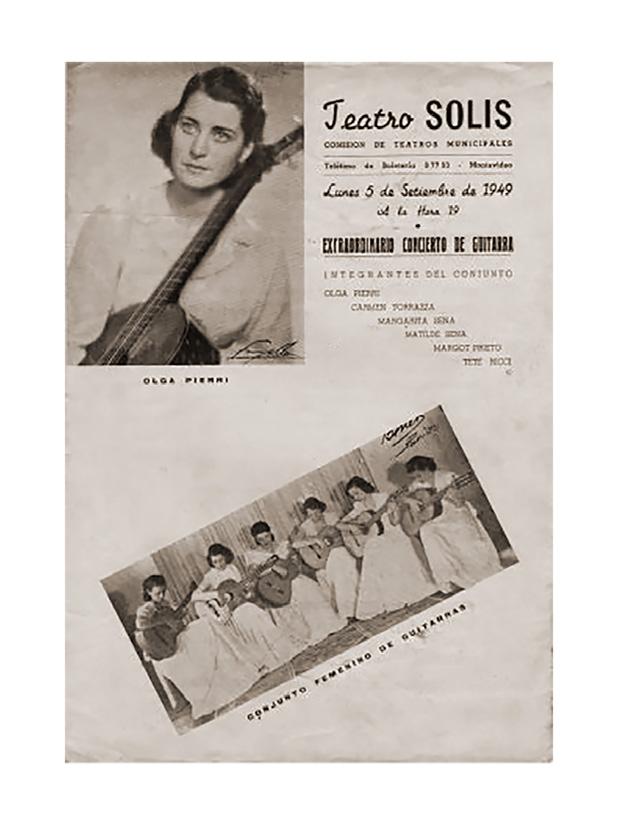

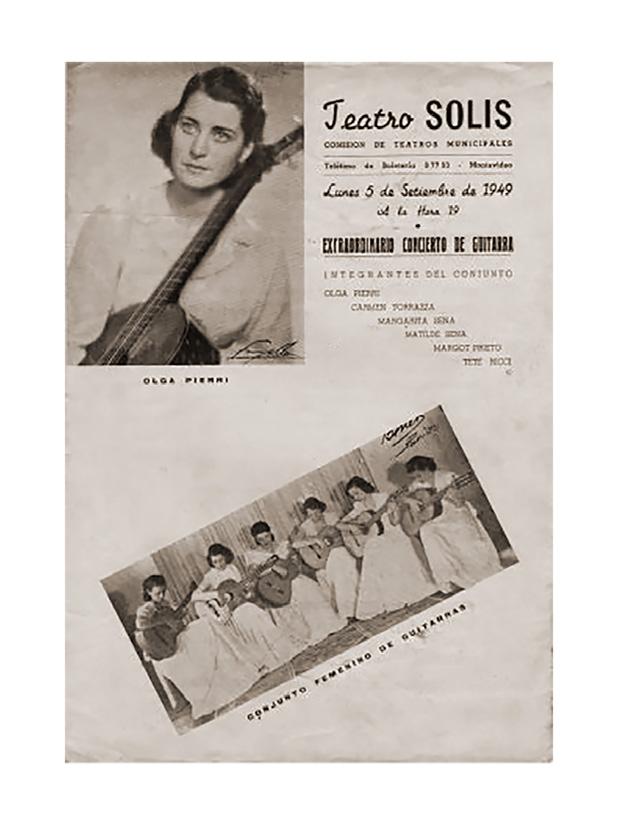

Olga Pierri, guitarist and teacher.

tar scene that developed here stimulated – and at the same time helped –Barrios to hone his technique and give wings to his compositions. In this regard, the protection and friendship that Martín Borda Pagola, Luis Pasquet and Eduardo Fabini afforded him were essential.

Segovia in Montevideo

As the twentieth century dawned, several successors of Francisco Tárrega were beginning to arrive in Montevideo: Josefina Robledo, Miguel Llobet, Emilio Pujol. The most important, Andrés Segovia, performed here for the first time in 1920, subsequently returning in 1921, and again in 1928 and 1937, before taking up residence for several years after marrying Spanish pianist Paquita Madriguera. Segovia’s presence in Montevideo gave the musical scene of the city – and, from there, the entire country – a tremendous boost, especially in guitar circles.

Carlevaro, the teacher

That same year, in 1937, Abel Carlevaro started taking lessons under Segovia, although he had already officially started giving public performances in 1936, in concert venues as well as on air, and had already created a name for himself as one of the most momentous guitarists of the day. This was followed by his work with the Brazilian

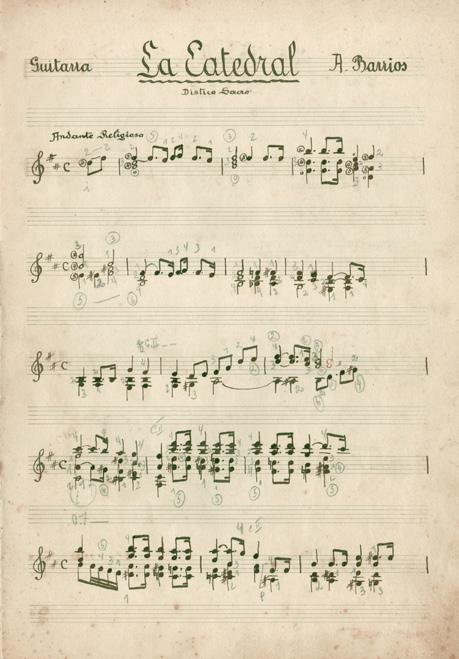

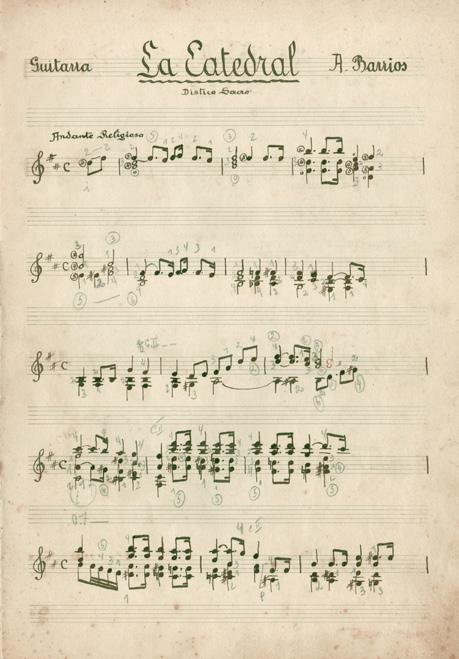

Agustín Barrios and the manuscript of his composition inspired by Montevideo’s cathedral.

27

Carlevaro, concert performer and composer, trained a whole generation of brilliant guitarists.

master composer, Heitor Villa-Lobos, his tours around Brazil, his three-year stint in Europe, and then a period of retreat in Montevideo, where he spent nearly twenty years working his guitar technique discoveries into a more structured shape. This was also the period, from 1951 to the mid-1970s, in which he consolidated (via his classes and publications) his status as an innovative educator and began attracting students from Uruguay and abroad. There were other major teachers whose legacy stems from this same era, including Atilio Rapat, Olga Pierri (Álvaro Pierri’s aunt), Lola Gonella de Ayestarán, to name but a few.

International success

Meanwhile, other Uruguayan guitarists were also rising to fame around the world: Julio Martínez Oyanguren in the United States, Isaías Savio in Brazil, and, in the second half of the century, two big-name disciples of Atilio Rapat successfully established themselves in Europe: Oscar Cáceres and Antonio Pereira Arias, as well as Betho Davezac and, later, Jorge Oraison, a pupil of Lola Gonella de Ayestarán.

As of the 1970s, and for nearly all of the crucial thirty-year phase of Carlevaro’s international

Abel Carlevaro with the guitar of his own invention, built by Manuel Contreras initially and then by Eberhard Kreul.

career as a concert performer, composer and teacher, several of his Uruguayan disciples were shining on stages all around the globe: Baltazar Benítez, Eduardo Fernández, Álvaro Pierri, José Fernández Bardesio, Juan Carlos Amestoy, César Amaro, as well as – in the field of popular music – Daniel Viglietti, Eduardo Larbanois, and other top-level guitarists. But Carlevaro’s direct students were not the only Uruguayan guitarists to achieve success abroad. The names Eduardo Baranzano, Álvaro Córdoba, Ruben Seroussi, Leonardo Palacios, Ricardo Barceló and Sergio Fernández Cabrera (to list but a few) attest to the magnitude and international transcendence of Uruguay’s guitar talent in the last third of the fertile twentieth century.

28

The first Uruguayan guitars

by Guzmán Trinidad

Lauro Ayestarán, Uruguay’s leading musicologist, asserted in his 1953 tome La M ú sica en el Uruguay that “there had been luthiers working in our country since at least as far back as the 17 th century”.

it is well known that “in the Jesuit missions, in the north of the territory, luthiers, guitar makers and even organ builders were making a name for themselves”. The first trace in writing, however,

dates from 1841: an advertisement in the Montevideo press announcing that Agustín Caminal (a piano- and guitar-maker) had closed his workshop in the street called Calle de San Juan because he was out of the country.

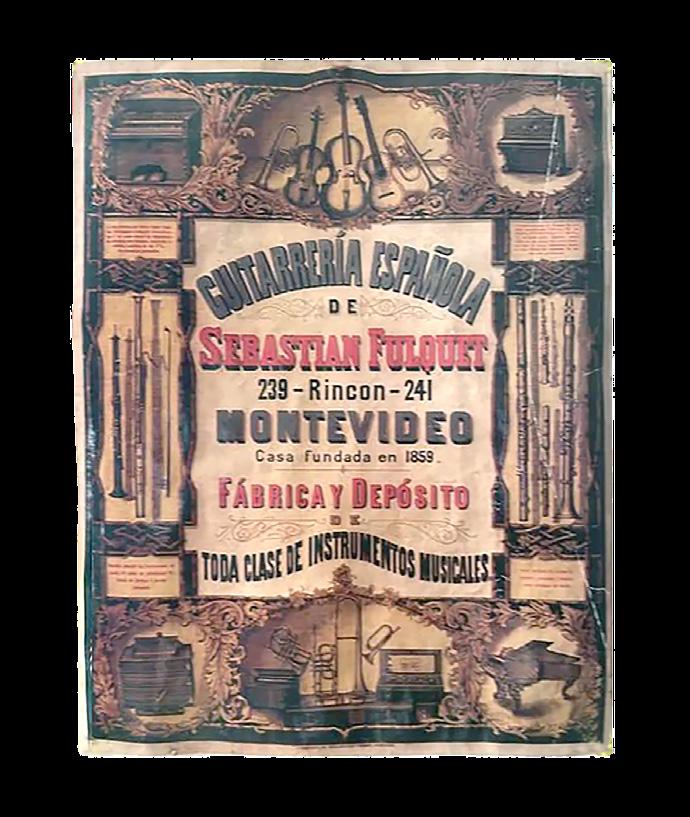

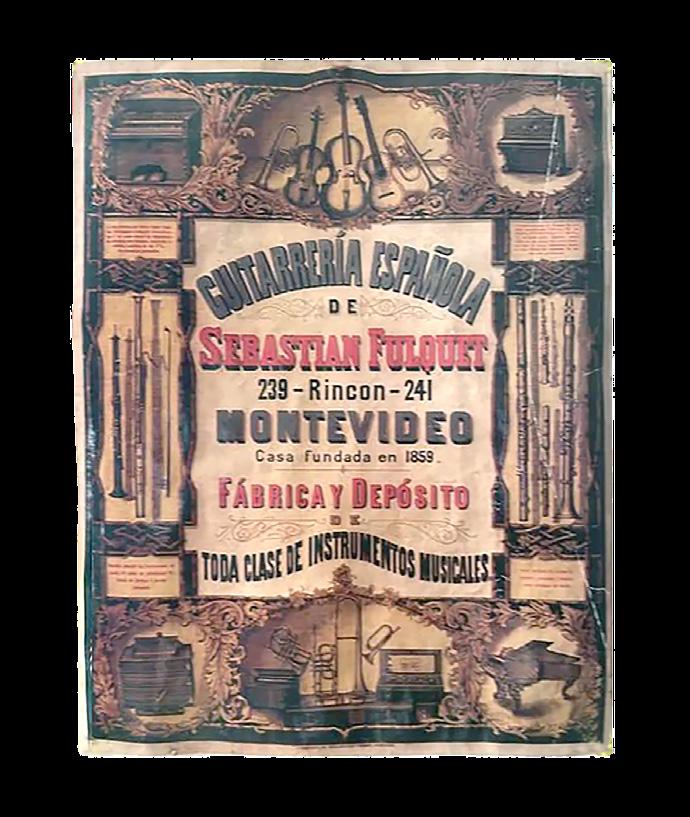

We also know of another pioneer in lutherie named Sebastián Fulquet , who founded the Guitarrería Española in Montevideo in 1859 and produced a great many instruments through to 1891.

To illustrate Uruguayan lutherie, we have chosen three luthiers who best illustrate their craft in the twentieth century: Vittone, Pereira Velazco and Santurión.

Pedro Vittone (1871-1940)

He was an accomplished guitarist and an excellent guitar maker. He also taught guitar, following the Dionisio Aguado school. Among his pupils, notably, was Abel Carlevaro (from the age of seven) and his brother, Agustín.

One of Abel Carlevaro’s first ever guitars was a guitar that Vittone had built in 1936. It was on this instrument that he recorded Variaciones sobre ‘Folías de España’ y Fuga by Manuel Ponce in 1958.

Sebastian Fulquet was making guitars in Montevideo from 1859 to 1891.

30

Antonio Pereira Velazco

Born in 1900, this luthier achieved international renown. From a very young age, he trained in woodwork and subsequently specialised in cabinetmaking. Around 1938, he struck up a friendship with the famous Spanish guitarist Andrés Segovia, who was living in Uruguay, when repairing Segovia’s Hauser guitar. He was also able to study Segovia’s Manuel Ramírez, which he later used as the basis for his own manufacture.

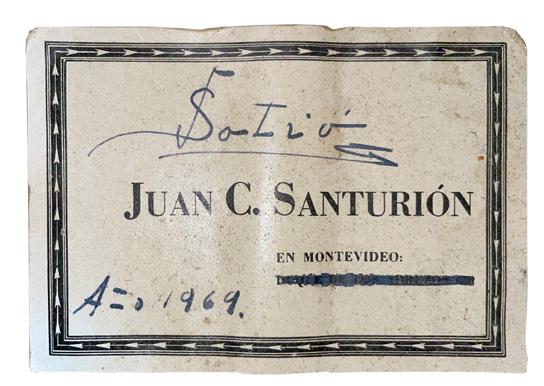

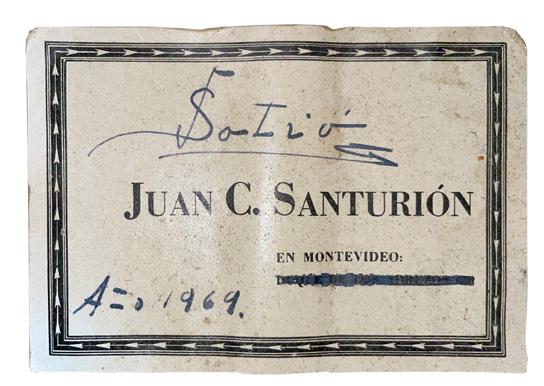

Juan Carlos Santurión Martínez

Both musician and luthier, he was born in 1913. He studied the guitar with Maestro Atilio Rapat, gave recitals and concerts and performed on tour in South America. In 1950, he headed to Spain to perfect his skills: as a guitarist with Emilio Pujol; and as a luthier with Ignacio Fleta. He was the first to teach lutherie at the Universidad del Trabajo del Uruguay (Workers’ University) and has trained, since 1955, generations of excellent artisans in the construction of classical guitars.

31

Guitar by Pedro Vittone with which Carlevaro recorded Folías de España y Fuga by Manuel Ponce.

for

32

Antonio Pereira Velazco took the inspiration

his guitars from the Manuel Ramírez that Andrés Segovia owned.

33

Juan Carlos Santurión Martínez perfected his craft has a guitarist with Emilio Pujol and as a luthier with Ignacio Fleta.

the

34

Situated on

eastern bank of Río de la Plata, opposite Buenos Aires, Colonia del Sacramento is the oldest city in Uruguay.

35

Ariel Ameijenda, luthier,

36

musician and composer

Born in Montevideo, Ariel Ameijenda learned his craft from his father, luthier Manuel Ameijenda. His father had been a pupil of Juan Carlos Santurión, who in turn had studied lutherie in Ignacio Fleta’s Barcelona workshop in the early 1950s!

37

Where does your relationship with music come from?

Ariel Ameijenda – My mother was a pianist; my father sang, played the guitar and was a luthier. My mother also used to help him sand and varnish the guitars. So, I really grew up in a luthier’s workshop, playing around with wood and listening whenever clients would come to try out the guitars. My father showed me the ropes and I used to help him with his repair work, but at the age of 17, I had not yet settled on any clear vocation. Since I wanted to see the ancient civilisations of the Americas, I set off on a trip to Peru with a friend to see Machu Picchu. When we got to Cusco, as we passed by a restaurant, I heard some Indian music that piqued my curiosity. It was an album by Ravi Shankar and I had an absolute epipha -

ny. When I got back to Montevideo, I enrolled in Musicology at university. I studied organology, composition, harmonics, acoustics, history of music… and I built a sitar.

When I completed my studies, I started saving money for a trip to India. I was able to travel there three times, staying for four months each time. It was there that I studied art music, and the sitar with Saeed Zafar Khan, I visited lutherie workshops and practised yoga alongside yogis who were also musicians.

I also met Swami Nada Brahmananda, a Himalayan yogi, more than 90 years of age, who achieved enlightenment through music and who taught me, in two unforgettable hours, much more than I had ever learned at university, especially with regard to rhythm and melody, space and time, shape and colour.

The ribs are attached to the heel with the use of wedges.

The ribs are attached to the heel with the use of wedges.

38

Delia and Manuel Ameijenda, Ariel’s parents.

What I love about India is the way that they see music as a kind of higher language compared to verbal language, as a means of accessing a different state of consciousness. They also explained to me that they deemed music a living thing, something that is born, which blossoms and then dies.

This is my usual gripe about guitars made out of carbon! When the fundamental note fades, the remaining sounds are dissonant. With a Torresstyle guitar, though, when the note fades, the dying overtones will still be in harmony with the fundamental. This is what makes a sound beautiful. And it is this beauty that gets lost as guitars pursue ever-increasing volume.

When I returned from my third trip to India, I composed some music for the theatre, to be played live on instruments from different countries: Indian sitar and sarod, African kalimba, Turkish saz, Brazilian berimbao, etc. These compositions earned me several awards.

In 2001, my father fell ill and passed away.

Bracing inspired by the Torres SE 81 guitar.

Bracing inspired by the Torres SE 81 guitar.

39

He glues the linings into a mould separately.

His personal model, with back and sides of rosewood.

I knew that I had to pick up where he left off. So, I stopped my work as a musician and as a composer and focused instead on lutherie in a full-time capacity. I enjoy working with my hands, in the silence of the workshop, working with tangible things and feeling that I am making something for others.

What are your guitars like?

A. A. – More than twenty years ago, when I was repairing several guitars by the great Spanish masters, I fell in love with their sound. That was when I realised that the sound I liked the best came from Torres, Manuel Ramírez and their successors.

I also like the guitars by Ignacio Fleta from

the 1950s, before he increased their size and changed the bracing in 1958.

We all agree that the soundboard is really important, but I am becoming increasingly aware of the importance of the sides, back and neck as well. All of the guitar’s parts have an acoustic function.

The soundboard works like a membrane, but it is made of wood, and wood has veins, meaning that it won’t have the same flexibility length-wise and cross-wise. The fan’s job is to even out this discrepancy.

One of the bracings that I use, which I copied from a 1952 Fleta, is made up of seven

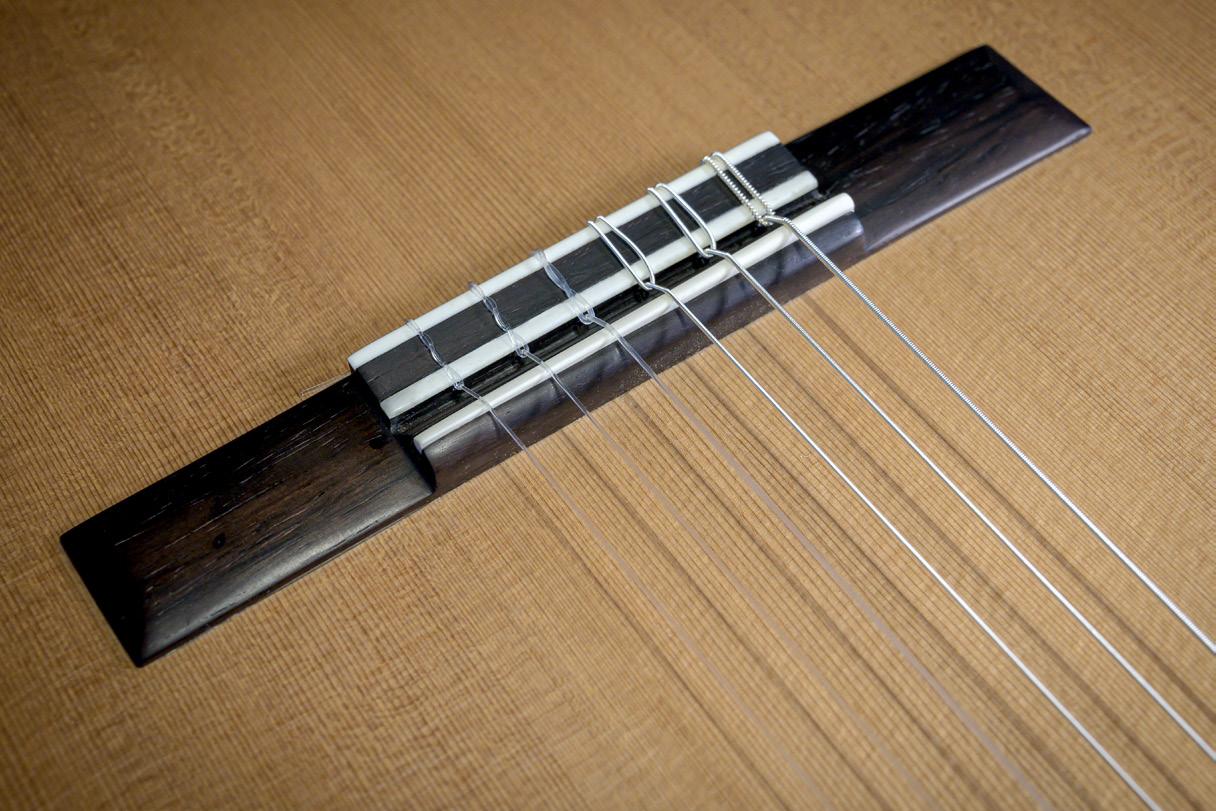

The ebony nut lends a touch of elegance.

40

His

model inspired by the Torres SE 81 guitar.

His model, with cedar top and headstock inspired by Torres.

struts. Not all of the struts converge at the same point; the third and fifth braces converge a little higher than the others. I also use a five-strut bracing pattern inspired by the Torres SE 81, of which I often make replicas. During construction, I first set the ribs into a mould and glue in the linings (with the kerfs facing inward). Next, after having glued the soundboard and neck separately, I place them on the solera , then add the ribs with alreadybonded linings, and finally I glue on the back. In this way the ensemble is firm, the gluing is strong and everything is easier. I don’t use peones . I am sure that Torres used this method for many

of his guitars, especially in the second epoch. When I first started following Torres, I began thinning out the soundboard and these days, when making my replicas, I also reduce the thickness of the sides to 1.2 mm. I think that the curved shapes of the sides are enough to give them the required stiffness, despite being so thin. The arched shape makes the soundboard stronger, meaning that I can pare it down even further; if it’s made of spruce, I go down to 1.3 mm around the edge and 2.3 mm in the centre.

The headstock is designed to enhance string alignment.

43

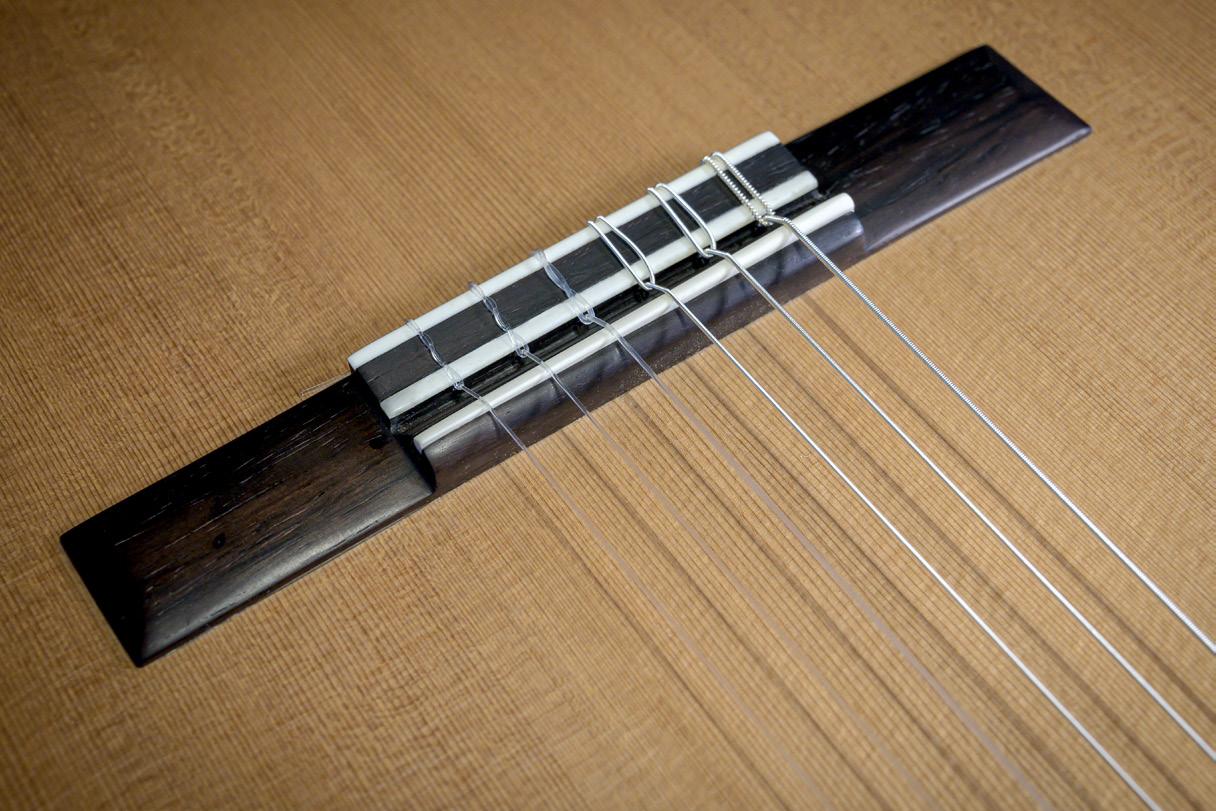

The carved saddle ensuring string length compensation.

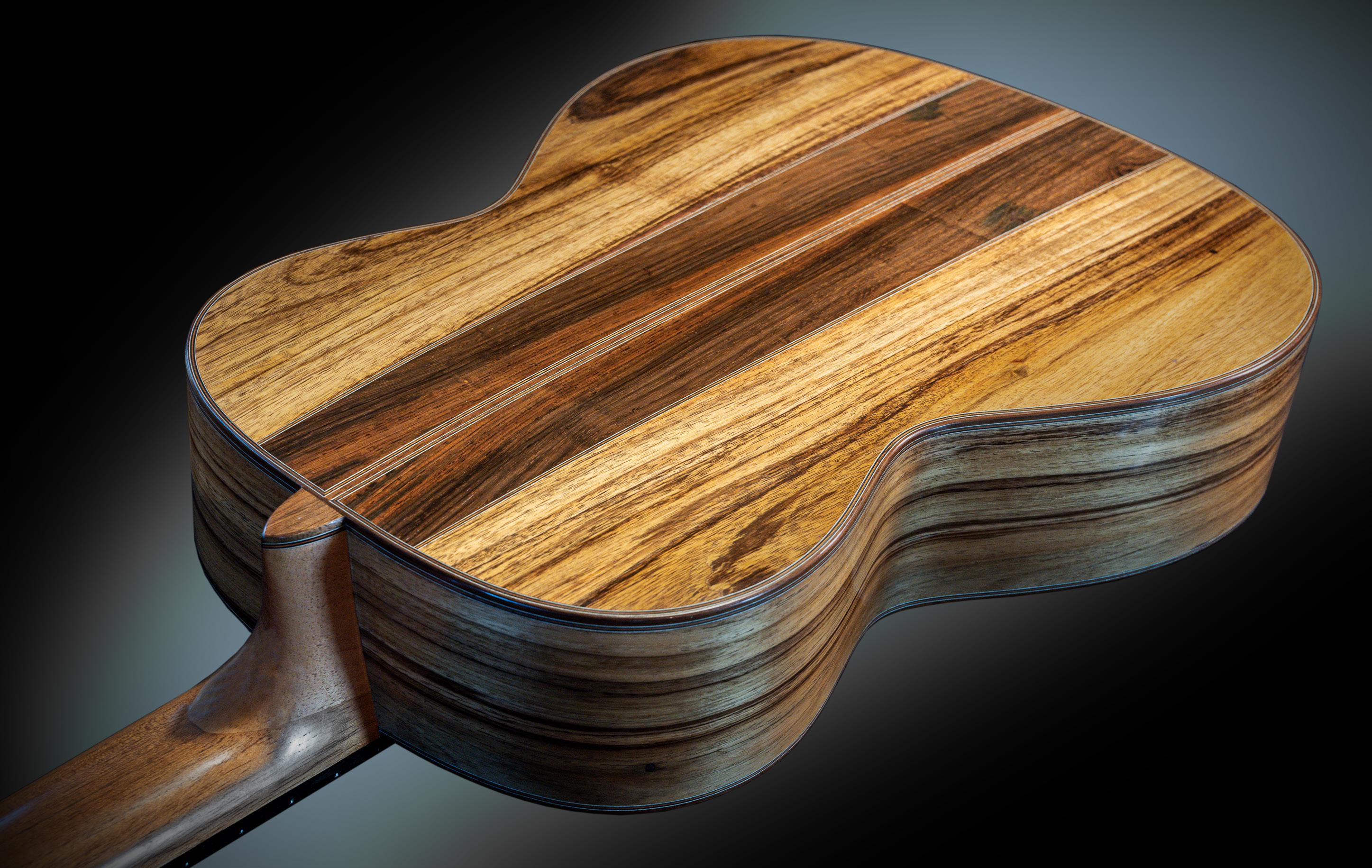

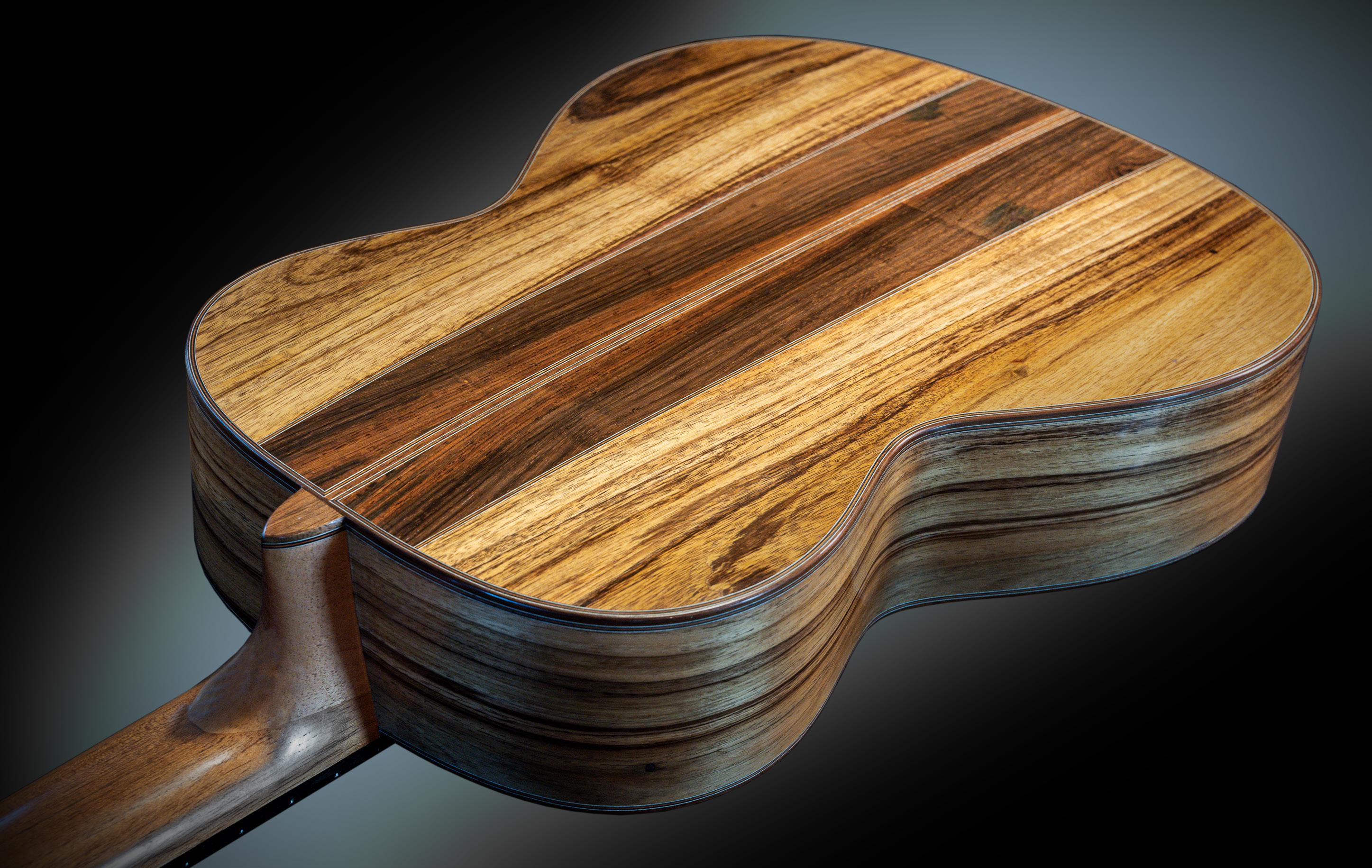

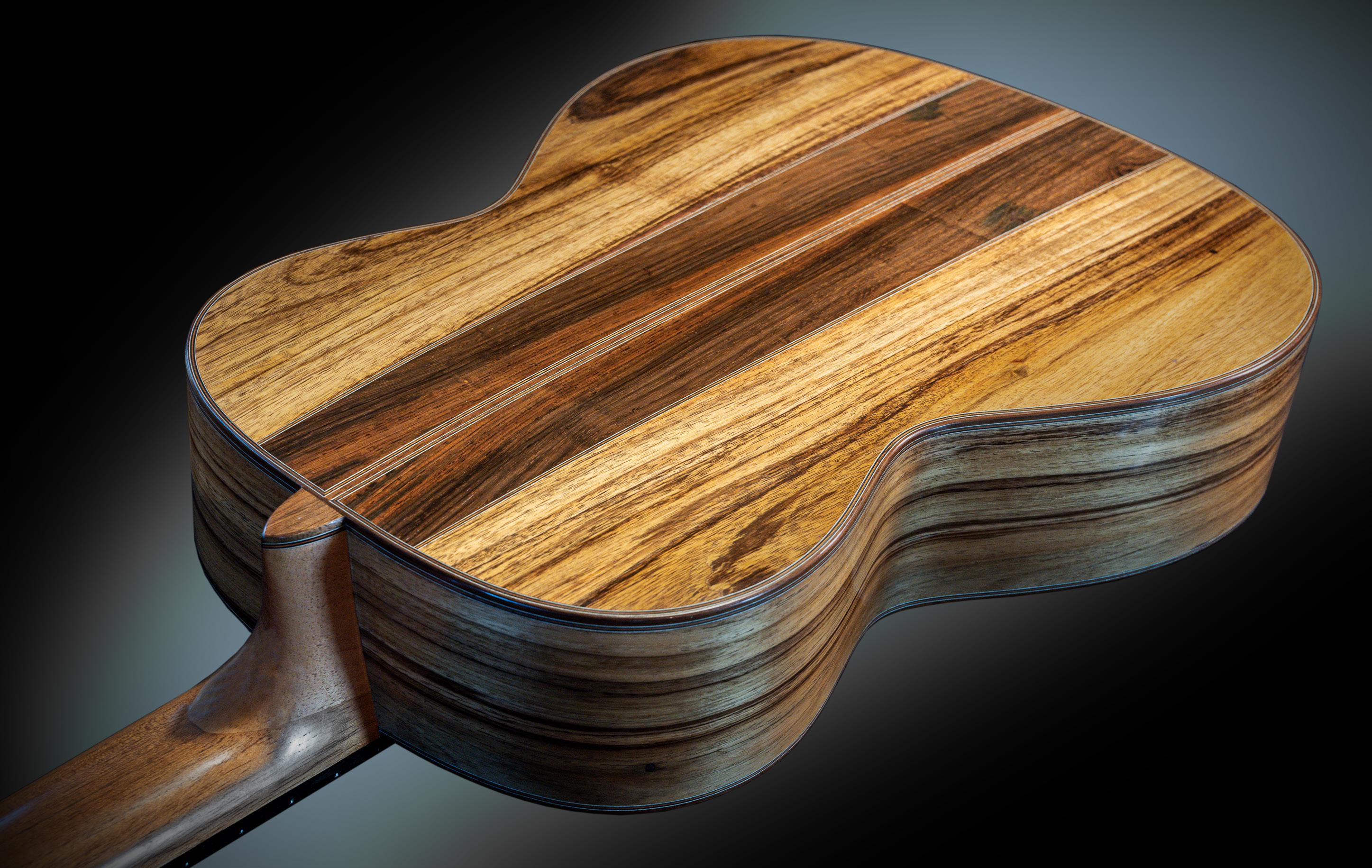

The sides are of blackwood while the back comprises a combination of blackwood and rosewood.

44

The headstock that I have designed gets narrower toward the top, so that the central strings, the third and fourth, go straight to the nut, angled as little as possible.

As a musician, I am seeking dynamism and balance more than volume; I want the guitar to sing!

Which woods do you prefer?

A. A. – For my soundboards, I like both woods. I mostly use spruce when making copies of the 1886 Torres SE 81. I think that spruce can perform at its best in this type of construction, when made gossamer thin. With cedar, it’s different; I tend to go more by intuition and, working with greater thicknesses than when using spruce, I think I have found a more crystalline sound, which I really like.

I also like using alerce 1 for my soundboards, but

1 Alerce (Fitzroya cupressoides). This is a tall tree that goes by the name alerce in its native countries: Argentina and Chile. It belongs to the Cupressaceae (cypress) family, the largest conifer family. The species can live for thousands of years and reach a height of fifty metres. It yields light wood (500 kg/m3) with a reddish colour; it is highly prized in southern Chile for making wood shingles. The threat of extinction led the Argentinian and Chilean governments to declare this species a natural monument. It is sometimes called Patagonian cypress in English.

using it does pose a few problems. It’s a magnificent, fantastic wood, albeit difficult to work, but trade in alerce has now been prohibited. I only ever use it if I can be certain that it was logged prior to the ban.

Since it is a heavier wood than cedar or spruce, I have to work with incredibly fine thicknesses, and despite this, the sound remains quite metallic. It’s a wood that divides opinion: musicians who try it either love it or hate it, falling in love with it or spurning it forever.

My father really loved it. There are also guitars with alerce soundboards built by Casa Nuñez in Buenos Aires.

Both alerce and Brazilian rosewood raise ethical issues: we need to be aware of their overexploitation and avoid encouraging poachers. If we want to continue using these woods, we must make absolutely sure that they predate the trade ban.

For the ribs and back, I like rosewood and maple. Upon the advice of my father, I started using blackwood ( Acacia melanoxylon ), a local wood that makes a good alternative to rosewood.

Each wood requires its own unique way of working and I try to bring out the best in each one.

46

In his office, Ariel is surrounded by antique instruments.

“As a musician, I am seeking dynamism and balance more than volume; I want the guitar to sing!”

47

The resort city of Punta del Este is just a few kilometres from Ariel Ameijenda’s workshop.

48

Alexis Parducci, winner

Alexis Parducci currently lives in Mar del Plata (Argentina), where he works as a luthier and also organises lutherie training courses in which he passes

50

in Granada in 2022

on what he learned in Spain to young luthiers from his homeland. He won the Concurso Internacional de Construcción de Guitarras Antonio Marín Montero in 2022.

Where did you learn lutherie?

Alexis Parducci – It all began at the age of 14, when I went with my father to the workshop of Ruben Arnero, a luthier in Mar del Plata, to get my grandfather’s guitar repaired. I was already keen on woodcraft, but that workshop blew me away. Since that luthier was giving classes at the local school of arts and crafts, I decided to enrol and I started building guitars with him, in parallel to my studies.

Alexis checks the domed profile that he will be giving the guitar’s back.

He prepares the sides separately so as to work more comfortably.

When I was 18 years old, since I was still undecided as to what I wanted to study at university, I took a sabbatical and headed to Tenerife (in Spain’s Canary Islands). Like so many Argentinians, I am descended from Italian immigrants, which enabled me to obtain an Italian passport and work in Europe.

In Tenerife, I worked for some time but had no contact with luthiers; so, I went to Málaga, on the mainland, where I knew there was a school of lutherie. I managed to enrol and took a twoyear course. Classes would finish at 3 p.m. and I would then go and work as a waiter until midnight!

After four years abroad, I went back to Argentina, hoping to set up as a luthier, but I quickly realised that I was not yet sufficiently qualified. I therefore returned to Málaga to improve my skills in quartet lutherie under José Ángel Chacón and I ended up staying five years.

I then went on to work with Víctor Quintanilla, a colleague from the school of lutherie, with the aim of developing

a personal guitar model. We had studied many guitars from Granada, performed a lot of experiments and tested a host of templates, fan bracings, etc. Ultimately, I felt drawn to the tradition laid down by Torres, Santos, Barbero…

And are you still following that same path?

A. P. – Yes, my fan is similar to the one used by Barbero, with five near-parallel struts and two sloping ones on the sides. I think that the idea came from Santos. It’s a fan that offers very little resistance transversally, leaving the soundboard a great deal of elasticity.

I have my own personal method for gluing the brace that goes under the bridge. I lower the wood’s humidity level to 35%, so that when I glue in the brace and the humidity rises back up to the 45 or 50% level that prevails in my workshop, it expands and the soundboard naturally arches

The linings are laminated and the ribs are reinforced by slender supports.

52

Guitar and maté (traditional hot drink): two Río de la Plata icons.

53

With his colleague Víctor Quintanilla, he tested numerous templates.

His manner of building is traditional, Granadan, and his template is also inspired by Torres.

up into a domed shape. In this way, I am increasing its resistance, which makes it possible to use a fine brace – only 2 mm – and adding a small weight to the fan.

With which woods do you enjoy working?

A. P. – For the soundboards, I like a light, supple spruce, with grain that is not too tightly packed. Depending on the soundboard’s stiffness, I can thin it out, or vary the slope of the struts or the height of the braces.

By the same token, however, I have come to realise that there is a kind of knowledge that we all share: the intuition, on which we unconsciously tend to rely when making decisions for resolving unexpected issues. Since wood is a heterogeneous material, we have to factor it in when assessing each component of the guitar. For the sides and back, I love all rosewoods, but also certain local tim -

bers. The bridge, however, is always of Rio rosewood. When I carve it, I aim to recreate the look of vintage bridges.

The way that I build is conventional, Spanish, Granadan, in the style of Torres, and my template is also inspired by Torres.

Conventional construction, albeit with a few twists: Firstly, I position the sides in a mould, which makes it easier to glue in my top and back linings. The linings are laminated and the sides feature little supports which, despite adding very little mass, offer greater strength and power, and raise the body’s resonance frequency. The supports are triangular, affording maximum strength with minimum weight. I use artisanal clamps for gluing in the linings; their opening span and contact surface are a perfect fit for the shape of the rib.

His rosettes are both elegant and understated.

55

When the wood is beautiful, he doesn’t add a decorative central back seam.

A magnificent creation using London planetree

56

wood (Platanus x acerifolia).

The decorative elements are prepared on a guide so as to facilitate subsequent gluing.

He uses animal glue systematically.

The pressure can be adjusted with rubber bands. When the wood is beautiful, I don’t add a decorative central back seam.

With regard to the aesthetics of my guitars, I aim for both elegance and temperance. I don’t like guitars with excessive decoration. The guitar should be as beautiful on the inside as on the outside.

I’m not into modernity. I think that it’s a mistake to go trying to re-invent the guitar. I am not interested in lattice guitars or double-tops: those are not guitars; they’re something else. I don’t want epoxy glues or polyurethane or carbon in my workshop. The market has invented a whole bunch of things that we don’t need. The structure of wood is incredibly complex, and coaxing out its most beautiful sound is a very delicate alchemy.

You have to feel the wood, and handle it with love. When I’m working with wood, I am very focused, as if in a dialogue with it, and whenever little accidents occur or the unexpected happens, I respect them. I like to think of myself as just one more tool in the workshop. We are constantly controlling our strength, our full attention on the chisel’s tip. Science cannot really help us much. Factory-made guitars could never rival those made by luthiers because there’s such a huge component that boils down to feeling and intuition, which machines cannot hope to match. Craftsmanship like this is a way of defying the world in which we live.

58

A bracing system inspired by Marcelo Barbero.

“I use artisanal clamps for gluing in the linings; their opening span and contact surface are a perfect fit for the shape of the rib.”

Over the Paraná River, a bridge connects the cities

of Rosario and Victoria.

61

Diego Contestí, in search

He lives in Rosario, the largest city in the Santa Fe province (Argentina), on the western bank of the Paraná River, some

search of balance

300 km upstream from Buenos Aires. The export of cereals makes this port one of the most important in the country.

Have you always lived in Rosario?

Diego Contestí – I was born here, in the province of Santa Fe, but my family then moved to Buenos Aires. As a youngster, I loved Andean music and I had started making “quenas” 1, but one day my father gave me a stunning “charango”, built by a luthier in the region of Córdoba. I was captivated by this instrument, unable to believe that it could have been made by a person. From that moment on, I started looking for a luthier who could teach me the craft and I got in contact with Oscar Trezzini, who was teaching in Buenos Aires at the time. I stayed with him for two years, and then I continued all by myself, working to hone my skills without a mentor.

Which other influences have there been?

D. C. – I have not had the chance to see many guitars made by the master luthiers. The ones that I have seen made by Argentine luthiers were less than thrilling, with the exception of Oscar’s guitars, which I find marvellous. My first guitars were a bit hybrid: classical in appearance, but offering a slightly flamenco

1 The “quena” is a wind instrument similar to a flute. It is one of the oldest instruments to be found in the Americas. It is typical of the Andes Mountains.

63

64

“I build in the same way that luthiers make violins, with the body separate from the neck.”

“I have added an extra brace in front of the one under the bridge, designed to stop the soundboard from tipping toward the rosette.”

sound, quite percussive, with a very pronounced attack and moderate sustain. I was fairly happy with my guitars, until the day that I saw and heard a Dominique Field guitar, owned by one of Eduardo Isaac’s followers. It came into the workshop for some minor adjustments; the excellence of the craftsmanship and beauty of its sound left me in awe.

From then on, I started emulating Field’s guitars, with the sloping brace and five-strut fan. They sounded very nice, but I wanted to understand the reason why, and so I decided to build a guitar with a removable back, so that I could try out different bracings and thicknesses.

The big turning point came one day as I was trying out a guitar on which the top string had been tied in such a way as to leave a few centimetres resting on the soundboard. The guitar sounded fine, but when I cut off the excess length of string, the sound changed a little, just subtly, but it really riveted my attention. I understood that by removing or adding weight to certain areas, we could bring about a change in the sound, even on an already-finished guitar. That revelation opened up a whole world of possibilities. It was as if I had been doing maths all my life using only whole numbers and then suddenly learned to use decimals. It meant that I could make subtle, very fine adjustments to the sound.

65

When you have a sound in your head, you’ll never be satisfied until you’ve achieved it.

Has your bracing changed?

D. C. – Having built and repaired a lot of guitars, I get the feeling that the bracing style is not so very important. What I find crucial, however, is the balance between the soundboard’s flex and the weight of the bridge. As I gained experience, my bracing evolved and I added a transverse brace, meaning that, in addition to the brace that goes under the bridge, I include another one designed to stop the soundboard from caving in toward the rosette. In the modern guitar, it is understood that the back and sides need to be quite stiff in order to increase sound projection. For the sides, I have opted for Field’s solution: I strengthen them with little supports, since this adds less weight overall than would laminating the ribs.

Any other details to mention?

D. C. – To make the neck, I section the wood down its length, and glue the two halves together top to tail. I saw it done on a Colombian “tiple” 2 . Eve -

2 The “tiple” is a guitar, derived from the Spanish vihuela, with four three-string courses (twelve strings in total) which developed in South America, chiefly in Colombia.

Details of a guitar made of white carob (Prosopis alba), with cedar top, ebony saddle and simple rosette.

ry piece of wood has its own grain and flexibility; I think that doing it this way balances these phenomena and improves strength.

I build in the same way that luthiers make violins, with the body separate from the neck. My bridges are light, between 14 and 15 grams. The saddle is made of bone or ebony; bone produces a more crystalline sound. One other detail: I use French polishing on my guitars.

Which woods do you like?

D. C. – We can’t always access premium materials here; we buy whatever is available. From our range of local woods, I use white carob ( Prosopis alba ), an ironwood known as “lapacho” (Tabebuia spp.) and “guayubira” ( Patagonula americana ), which was the Guaraní people’s preferred timber for making bows and arrows. For my tops, I like both woods: cedar and spruce. During the pandemic it was hard for customers to come and collect their guitars once finished. Several guitars therefore stayed in the workshop for a few months and I was able to see how they developed in that time.

The cedar gave full sound right from the outset, straight away, and didn’t change much over time. Spruce, on the other hand, needed more time, matured very nicely and acquired something special that doesn’t come from the luthier’s hand.

66

Colourful houses in the La Boca neighbourhood, a major tourist attraction in Buenos Aires centred on two themes: football and tango.

68

Mateo Crespi,

from music to lutherie

Mateo Crespi studied classical guitar from childhood and obtained his diploma from the Instituto Municipal de Música de Avellaneda (in Buenos Aires), where he teaches to this day. Building on his knowledge as a guitarist and as a teacher, he took an interest in building guitars and opened his workshop in 1999.

To date, one hundred and thirtyeight guitars have been born in his Buenos Aires workshop.

71

Between the soundboard’s layers, he adds thin diagonal strips of balsawood.

His guitars have a raised fingerboard and, upon request, a side port.

Which kinds of guitars do you like?

Mateo Crespi – My vision of the guitar comes from the perspective of a musician who spends hours and hours a day playing, and so I’m interested in how dynamic the instrument is, how sensitive it is, how comfortable to play, the richness of its colours, its sound projection… The guitar has come a long way in recent years and is a different instrument nowadays. Of all the guitars on which I have been lucky enough to play, I very much enjoyed the double-top German guitars, especially the ones made by Toni Müller.

What are your guitars like?

M. C. – I build my guitars with a double soundboard, using only wood, and my preferred combination is to use spruce on the outside and cedar on the inside. Between the top’s two layers, I place very fine diagonal strips of balsa. The thicknesses are around 0.8 mm + 0.4 mm + 0.8 mm. So I make a strong but light top. That way the guitar has good volume and projection. Overall, I would say that my style of lutherie is modern: double-tops, laminated sides, raised

72

Mateo Crespi produces his own tuners.

“My style of lutherie is modern: doubletop, laminated sides, twelve-hole bridge…”

fingerboard, twelve-hole bridge… I prepare the necks with a CNC machine. I build the body separately, basically because it makes the purfling easier, and I use hot, vinyl or epoxy glues, depending on the part that needs bonding. Moreover, I apply my shellac using a sprayer, in a dozen or so extremely fine coats which are then wet-sanded. I use today’s tools. Stradivarius used to do his sanding with sharkskin, which would correspond to a sandpaper grain of 220 today. But does that mean that I have to sand with sharkskin? No: I just go and buy 220 grain sandpaper!

Perhaps the most personal touch in my construction process is my technique for connecting the neck to the body. Not only do I glue the neck onto the soundboard and ribs; I also add a wooden screw

to secure the heel to the block on the inside that connects the ribs.

The problem in Argentina is that no-one imports workshop machines; we have to either make them ourselves or get help from a machinist friend.

There was a time when I was happy playing in public, but lutherie won me over. In my twenty years as a luthier, I have built a hundred and thirty-eight guitars. When you set foot in a luthier’s workshop, it’s such a wondrous place that you never want to leave. He uses a wooden screw to join the neck to the body.

74

The shellac is sprayed on, coat after very thin coat.

Wood from local cypress is used as the inner laminate for the sides.

The neck and heel are crafted separately and then bonded to the body.

Paris, June 2024

Website: www.orfeomagazine.fr

Contact: orfeo@orfeomagazine.fr

Guitar inspired by the 1958 FE 08 by Antonio de Torres.

Guitar inspired by the 1958 FE 08 by Antonio de Torres.

The ribs are attached to the heel with the use of wedges.

The ribs are attached to the heel with the use of wedges.

Bracing inspired by the Torres SE 81 guitar.

Bracing inspired by the Torres SE 81 guitar.