THE MAGAZINE FROM PALAIS DES THÉS

93

2024

Head

THE MAGAZINE FROM PALAIS DES THÉS

93

2024

Head

It is such an immense pleasure to be celebrating the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Tea School. Recognized as the gold standard for tea professionals and amateur tea drinkers alike, it was founded by François-Xavier Delmas and Mathias Minet, the creators of Palais des Thés, with the idea being to share their passion for tea with as many people as possible. What do Michelinstarred chef Anne-Sophie Pic, our tea sommeliers and all of our employees have in common? A love for tea, passed on and taught at the Tea School, of course! From learning about how its produced, to tea culture and tea tastings, as well as discovering tea and food parings and tea mixology, more than twenty-five thousand students – from professionals, beginners and amateur tea drinkers alike – have already taken courses and workshops taught by our dedicated trainers.

From its humble beginnings in 1999 in a small room adjoining one of our stores in the Marais neighborhood in Paris, the Tea School moved to a two hundredsquare meter space in Paris’ 11th arrondissement in 2008. This anniversary year marks new chapters in our school’s history. We opened a new branch in Marseille to train tea sommeliers from our stores in the south of France. Furthermore, this month we will also open La Manufacture, a place like no other located in the heart of an old tea farm in Georgia, which is dedicated to learning about how to produce tea. Our employees will learn all the ins and outs of tea production, which we’re excited to share with you in a Travel Journal article in a future issue.

These major projects for our Tea School, for which I have the pleasure of overseeing, are the next steps towards achieving our brand’s mission of offering unrivalled knowledge and expertise, providing training and sharing knowledge of this drink that has been enjoyed by many worldwide for thousands of years.

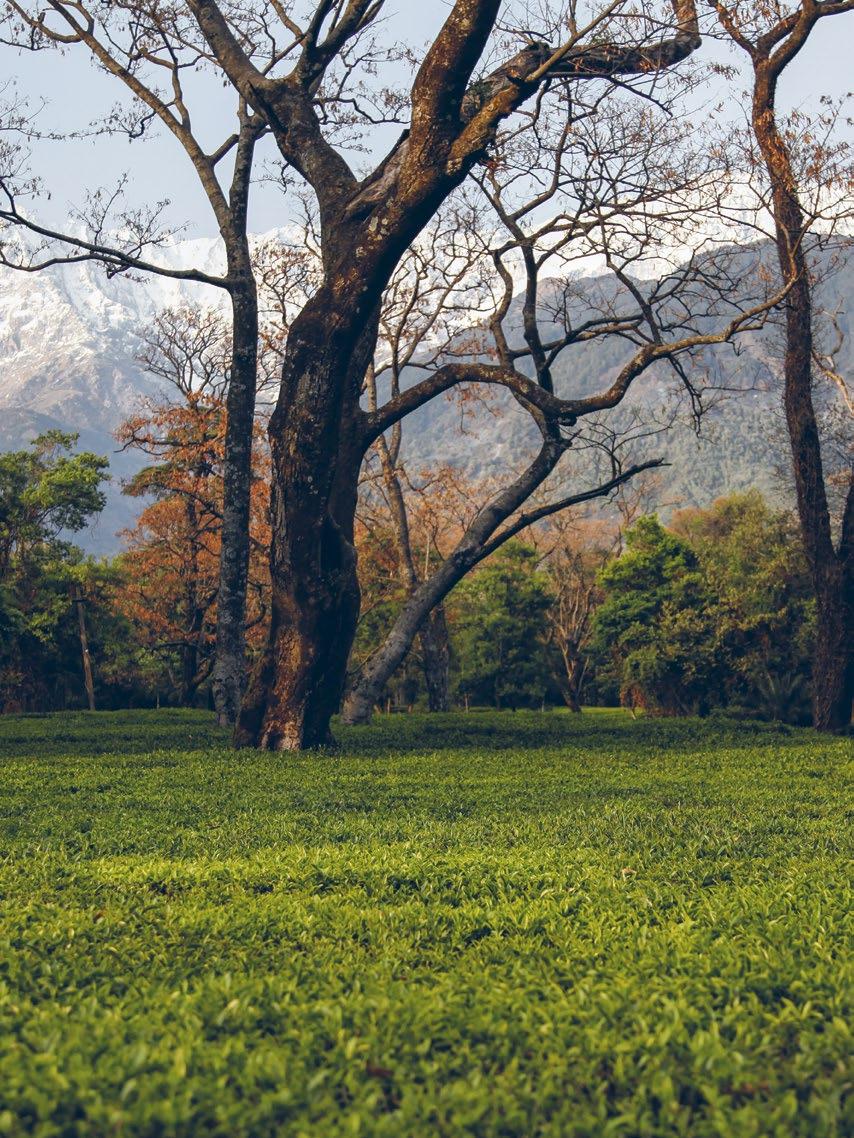

Trees are often planted in among the tea fields to provide shade for the tea plants.

By Yann Sowinski

By Elena Di Benedetto

By Cassandra Bagneris

By Désirée Picarelli

CONTRIBUTORS

Cassandra Bagneris

Cassandra is a master tea sommelier and sales advisor at the Grenoble store. She developed a passion for Nepalese teas when she visited the country’s tea farms for the first time in 2022.

Désirée Picarelli

Désirée joined Palais des Thés twelve years ago and is currently a master tea sommelier and manager of the Rue Tronchet store in Paris. She is also part of the teaching staff at the Tea School.

Yann Sowinski

Yann is a master tea sommelier and became the manager of the Tea School in 2023. He joined Palais des Thés over twenty years ago as a sales advisor, before going on to run stores in Paris and Rennes.

As an amateur tea drinker, who doesn’t dream of flying off to Japan? As the newly appointed head of the Tea School in Paris, this new role offered the ideal opportunity to lift the veil on a tiny part of this country which has fed my imagination since my teenage years. My mission? To bring back educational resources and objects, but also meet some of the artisans behind the teas which have infused in my cup and in my mind for the past decades.

By Yann Sowinski

In Japan, tea is machine-harvested, resulting in uniform and extremely orderly rows of tea plants

Culture, philosophy, aesthetics… From literature and gastronomy to the slightest artisan made object, everything related to Japan is at the heart of my existence. I even tried my hand at learning a few basics of the language which, when used in real life situations, turned out to be rather rudimentary and proved I had much room for improvement! Accompanying me on my travels is Léo, a tea explorer at Palais des Thés. The world’s tea farms have been his playground since he was nineteen years old, and this trip will be will be an opportunity to witness how his expertise is recognized by everyone throughout the industry, but also how important it is to maintain these valued relationships with the tea artisans by visiting them regularly. We take advantage of a short layover in Tokyo to go visit an exhibition on Rikyū, Oribe and Enshu tea ceremony utensils and marvel at the works of these great masters. Taste is refined with your eyes. My mission is to bring back authentic pieces that I will endeavor to learn about throughout our journey. I barely have time to go to Ito-ya, the holy grail for lovers of Japanese stationery, before we leave for Shizuoka. Located less than two hours from the capital by shinkansen, the national high-speed train, we will travel from this city through tea farms, production sites and other influential places related to Japanese tea.

The Shizuoka tea experience

Shizuoka is both the name of the prefecture and its capital. With around seven hundred thousand inhabitants, the city is considered small in Japan. Less obvious here than in Tokyo is the notion of tatemae, which is a behavior specific to Japanese culture that could be compared to “social politeness.” With more than twenty thousand hectares of tea farms, Shizuoka beats to

the rhythm of tea: 45 percent of Japanese tea is produced here and 70 percent of leaves harvested in the archipelago are processed here.1 In this city where the Tokugawa shogunate* (1603-1868) left their mark, making it the city of tea, you’ll find the most beautiful tea gardens, the best factories and unique expertise when it comes to tea refining techniques. These plantations are the most northern in the world, along with those in Turkey and Georgia. The climate is harsh for a good part of the year and, in certain seasons, there is the threat of frost. The climate is undoubtedly no stranger to the quality of the teas from this mountainous region covered in forests, which boasts a wide temperature range between day and night. In the Japanese lunar calendar, the names of the months refer to the climatic characteristics of the season or to traditions. The abundant rains and early monsoon that greet us attest that June is the aptly named “month of water.” Unlike tea buds, which flourish in these ideal conditions, it takes me a little bit of time to acclimatize to the humidity and ambient heat. It is time for the summer harvest. The excitement of the precious spring harvest having passed, producers are more available and already know whether it will be a good year for them or not. The 2024 vintage seems promising, as they appear to be relaxed and confident!

“Farmer’s tea”

We leave the city behind to head into the misty heights of Hebizuka, around seven hundred meters above sea level, to reach Mr. Nakamura’s pocket-sized tea garden. For several years now, this man of considerable age has been supplying us with Serpentine Gyokuro, an exceptional shaded tea. This grand cru can be purchased on site years in advance en primeur, just like wine futures in the world of wine, and is as legendary as its producer. The small, old-fashioned house from which he greets us reminds me of my grandfather’s DIY shed. It is a bric-a-brac of machines, with the most recent dating from the early 1960s. Together, we drink three gyokuros from three different varietals. These are pre-refined “farmer’s teas.” In fact, the Japanese tea production process has two distinctive stages, which can be widely spaced out in terms of time and space: the first consists of producing unrefined, crude tea, or aracha, while the second, by refining it, will give the tea leaves their final shape but also their character. These unrefined teas are milder and less potent than those that have undergone roasting (hi-ire) and the effects of time. As long as the tea is not finished, its quality remains uncertain but an experienced palate can already detect its promise. Aracha tea is hard to find on the market, and few tea industry professionals come directly to the tea farms to try it. Sheltered from the rain under the veranda of the family home, we savor the simplicity of pairing these teas in the making with potatoes dressed in Hokkaido butter, prepared by Mrs. Nakamura, and a few dried persimmons. We chat and bond with Mr. Nakamura, who reveals the concern shared by his generation of not finding a successor. The harshness of life in the mountains and the isolation puts young people off. It is even difficult for this renowned farmer to find a handful of pickers to harvest his tea in spring. Every time we visit, the question of age and the challenge in finding a successor always comes up. The land and the tea plants will remain, but who will take care of these gardens whose gastronomic richness plays an integral part in the world of tea?

1. Christine Barbaste, Franç ois-Xavier Delmas, Mathias Minet, Guide de dégustation de l’amateur de thé (La maison Hachette Pratique, 2022).

*Commanders-in-chief of the Japanese army.

This mountainous region covered in forests boasts a wide temperature range between day and night, providing the ideal conditions for tea plants to flourish.

The Japanese tea market is an ecosystem of different types of organizations, all of which I plan on visiting during my trip. It is very rare to find a factory that also owns tea gardens, a refinery and a distribution network, all at the same time. More often than not, these are three separate entities. Another particularity to Japan is that most of the teas sold there are blends. Each tea house or brand has a limited range of teas but showcases its own style. However, at Palais des Thés, what interests us most is the cultivar and, of course, the person or people who make the tea. We mustn’t forget that it was here in Shizuoka in 1954 that Hikosaburo Sugiyama developed the hybrid yabukita tea plant. There are also other cultivars, such as koshun, tsanumi, yellow-leaved cultivars and other species that I struggle to identify. When I bite into the fresh bud as I would a grape, I immediately detect the unique taste of each variety. My other aims during this trip are to document local cultivars, from both a botanical and a visual perspective. I conscientiously photograph different tea plant varieties and the tea gardens’ environment, I draw diagrams when the shot isn’t possible, I take notes, so that I can share all this precious knowledge as thoroughly as possible with our tea sommeliers.

The knowledge and taste of tea also enhance over a cup of tea. A tea tasting session is organized for our visit at the factory which processes Mr. Nakamura’s tea. The first teas are “easy,” or rather, they have a distinct umami taste we have come to expect from exceptional Japanese crus. Judging by our reaction of having tasted nothing new, we are offered teas with more character. The Japanese are intrigued by our Western approach and our sensorial, organoleptic tasting method which is borrowed from oenology and is gaining ground over here too. Not only does this entail analyzing the aromas, but also the texture of the liquor too. This quest for aromatic depth has pushed them to bring back forgotten or lesser-known cultivars. As an avid fan of tea rituals and their associated accessories, I really enjoy using the Japanese tasting set, which is very different from the British teaware we are used to using in France. The leaves are not removed from the cup and are therefore left to infuse for a long time, obtaining aromas that would have appeared after several successive infusions. Despite being over-infused for our taste (a way of revealing a tea’s potential imperfections), this can be rather off-putting to inexperienced taste buds.

The flowing day, we visit a different factory where teas from here and elsewhere are refined. Roasted, vegetal aromas fill the air, wafting their way outside the tea refinery. They are so intoxicating I have the impression that I am sailing in an ocean of tea. This factory visit is the perfect opportunity to ask the thousands of technical questions that cross my mind. I already know that the Tea School students will be able to benefit from all these fine details that can only truly be experienced and observed when visiting in person. At the final stage of the production process, one experienced worker has the sole and difficult task of smelling the leaves fresh from the oven, to check whether they are ready. Everything rests on this person alone. In an industry where machinery is the norm, there is always a highly skilled person carefully checking the tea leaves at every step of the production process.

In Kawane, to the north-west of Shizuoka, we meet Susumu San whose farm is in the middle of a dense and misty forest that looks like it is straight out of a Hayao Miyazaki film. Susumu San saves abandoned gardens by giving them a second life. He also produces roasted teas, twig teas as well as classic and experimental sencha teas. We can ask him to tailor-make teas for Palais des Thés, which we buy from the refinery that “finishes” his teas. Among his virtues, Susumu San practices chanoyu (the traditional tea ceremony in Japan) and he is also an amateur potter. He surprised us by preparing a chabako ceremony (“tea box,” for transporting leaves, picnic-style), enjoyed in the great outdoors. We drink in silence from his handmade bowls, which he generously gifted us. These bowls will be used at the Tea School and will surely bring the chashitsu* to life.

In the same area, we meet another, aging farmer. He has the (rare) chance to have a son-in-law who will take over his garden. He shows us just how efficient and precise his machine specially designed for harvesting tea is: not only can it adapt to the dizzyingly steep leaning slopes, but it can also detect and pick tea buds for plucking. This is yet another distinctive feature of Japanese tea-growing expertise: ingenuity and meticulous attention to detail, all in the name of quality teas.

Mr. Nakamura in his tiny tea garden which spans less than ten hectares.

*The place where tea ceremonies traditionally take place.

While tea production in the Kyoto region is less important in terms of size and production, it is nevertheless both the historical birthplace of Japanese tea culture and a prestigious designation for matcha, gyokuro and sencha teas. This stopover is an opportunity to meet two Korean and Thai partners, who do us the honor of coming to meet us and spending a few hours with us. I couldn’t go to Kyoto without stopping off at the Raku (ceramics) museum, located in the Raku family home, before buying a few second-hand bowls at the market by the famous Tō-ji Buddhist temple.

During a trip to Nepal, Léo met Misato, the daughter of a Zen monk. This slightly-rebellious thirty-something had taken over the family temple, located in Yaizu. Misato decided to rebuild the place and plant tea plants in its gardens, just like in its former past. This young woman is not frightened by this long-term endeavor, as she is determined to make high quality tea that she intends to export. She will be helped by Susumu San along the way, whom she met through Léo. Here is an example of the knowledge-sharing fostered by the various people our tea explorers meet on their travels. Misato is a generous and inquisitive person. As such, she takes us to visit a wasabi farm, as well as a factory run exclusively by women. Our day ends with the most beautiful gift of all: an initiation to senchadō (“the way of tea” is the second type of tea ceremony to appear in Japan, along with chanoyu), according to the ancient Obaku* tradition, by Misato’s grandmother. This is a first for me, and a first for this woman who is reputed for her knowledge, as it is the first time she has performed the ceremony to foreigners and men.

I love this unparalleled energy that people “crazy” about tea seem to give off. And at Palais des Thés, we encourage this type of creativity in the hope of seeing these free spirits bring to life some unique and exceptional teas for all you tea lovers to discover. •

Unlike other European countries, France’s love affair with tea came about pretty late. For several centuries, tea in France was the reserve of the elite and a drink consumed almost exclusively in restricted circles. This situation explains how tea was slow to spread throughout society, because unlike coffee, tea had not become a product of daily and widespread consumption. Tea is like a blank page that leaves the door open to creativity and a sense of discovery. Over the past few years, there has been renewed interest for tea in France, to the point which small tea farms are flourishing across the country. Could this be the beginning of a new tea culture à la française?

The first records of tea in France appear in the middle of the twelfth century. Distributed in France via the Dutch East India Company from 1610, it was soon accredited for its health benefits. Following a rumor that it had cured Louis XIV’s chief minister Cardinal Mazarin’s gout, aristocrats began using it as a remedy.

As tea was more expensive than coffee, it became the reserve of the elite. A symbol of luxury, crystalizing social inequality, drinking tea was denounced and discouraged during the French Revolution.

During the Second French Empire, enthusiasm for English culture and in particular Empress Eugénie’s passion for literature revived interest in tea. It was the drink of choice among intellectuals in literary circles, and then in tea rooms which were popping up across the streets of Paris. The latter were a popular place for women to socialize, offering high-born women the opportunity to meet outside of their homes without having to frequent establishments considered unsavory at the time, such as bistros and cafés. These practices provide an explanation as to why tea spread slowly throughout French society: unlike coffee, tea was a drink to be enjoyed socially and reserved for high society. In France, tea was not drunk on a daily basis, meanwhile in England, its consumption was growing especially as it was also enjoyed among the working class.

On top of this aristocratic image, there were the disadvantages linked to its supply. While the British could rely on their colonies (India, Ceylon) to get tea at a lower price and in large quantities, France mainly produced coffee (particularly in the French Caribbean) which was available at a rather competitive price, which could explain the nation’s preference for this roasted drink.

However, France sought to develop tea production in its colonies, attempting to make them tea-growing regions to meet the demands of mainland France. In fact, colonists tried to plant tea bushes in Guyana, but this project was abandoned when France abolished the slave trade in 1815. A few tea bushes were later planted on Reunion Island, yet the quantity produced was unable to satisfy demand.

It wasn’t until the nineteenth century that there finally came a turning point in the French people’s relationship with tea. During the twentieth century, tea consumption increased and major French tea houses began to build their names.

Very quickly, the French market soon distinguished itself by approaching tea without having a pre-established consumption habit. Up until then, tea had not managed to become popular outside very exclusive circles. The French were discerning and savvy when it came to gastronomy and wine culture, so naturally they took a great interest in and had a curiosity for tea. Indeed, the notions of terroirs, harvests and varietals are common to both the worlds of wine and tea. Thanks to the impetus of major French tea brands, including Palais des Thés, France became a place where you could find a wide variety of teas, especially grands crus teas of all colors and origins. As such, the interest for superior quality teas continued to grow.

As France was not a historical tea-producing country and nor was it directly linked to the development of its colonial past, tea does not have the same roots in France as it does in China, Japan or the United Kingdom. That said, France’s gastronomic heritage permeates and influences our tea culture. Palais des Thés founder François-Xavier Delmas goes on to explain, “The French have always taken an interest in where their food and drink comes from and how they are produced. Tea culture is in many ways similar to the world of French wine, because it has a history and is linked to the terroir. At Palais des Thés, we consider tea just like wine. We explore a tea’s flavors in the same way we would wine. We can produce different colors, different vintages, new varietals, single estate teas, or fermented teas, just like in the wine-making world.” Interest in this drink is consistent with French mealtime culture: we eat, talk and discuss about what we eat without ever

The first documented use of tea in cooking in France was in a recipe for tea pudding by Vincent La Chapelle, a French chef and food writer. Published in 1742 in Le Cuisinier moderne, the recipe remained the only use of tea in French cuisine until the nineteenth century, before recipes for tea-based sweets were developed. The popularity of matcha tea, a Japanese tea ground to a fine powder, ushered in a new era of tea-flavored cakes.

2 out of 3 French people drink tea or herbal tea every day.

The French drink around 3 kg of coffee per year compared to 250 g of tea.

getting bored, and always with an importance for quality produce. In recent years, tea has garnered a bigger place on the gastronomic landscape, with the emergence of tea sommeliers, tea and food pairings, and tea recipes. A whole universe specific to our heritage and our codes is developing, be it in Michelin-starred restaurants, cafés or in cake baking. This vision contributes to inventing a true identity for French tea.

France’s renewed taste for tea and the curiosity aroused paves the way for new horizons: for tea production in mainland France.

Tea growing in mainland France is an idea that first emerged in the nineteenth century. In 1838, botanist Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Guillemin was commissioned by Louis Philippe to assess the possibility of growing tea in France by importing tea plants from Brazil. More than three thousand bushes were planted in Brittany, the region considered the most conducive for tea growing. However, the project never came to fruition with the botanist’s untimely death in 1840.

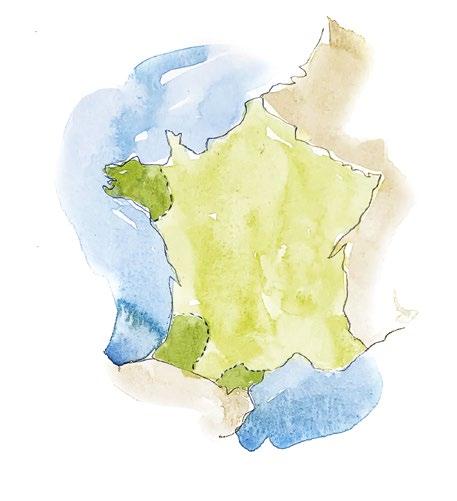

It was only in 1950 that tea growing resumed, albeit timidly. Production on the island only truly began to take off at the beginning of the noughties, a time when tea bushes were also starting to be planted in mainland France. Since then, tea gardens have been popping up all across the country, producing teas that each display a strong character rooted in their terroir. Acclimatizing the tea plant to our environment is no easy feat. It requires specific conditions to flourish, like acidic soils and a climate that alternates between heavy rain and sunny spells. These conditions are currently found in Brittany, the Pyrenees and even in the Massif Central, regions that are sufficiently humid, sunny and protected from frost to encourage the tea plant to thrive. The pioneers of French-grown tea are passionate about promoting this little-known, limited production which is inspired by centuries-old Asian expertise, while providing a form of freedom and creativity with respect for tradition. Initiatives in mainland France are arousing the curiosity of producers from around the world as well as tea lovers, and they are also being encouraged by French tea brands. We are certainly keeping a close eye on the latest goings-on in this tea-growing adventure – and we can’t wait to share them with you! •

There have been many attempts at growing tea in France since the beginning of the noughties. As such, there are now around thirty to forty tea farms in mainland France. Acclimatizing tea plants to the country’s soils and mild climate can be a bit of an adventure, but it is a challenge many of the country’s teagrowing pioneers face on a daily basis. While the sector still remains rather niche, the quality is promising and yield continues to increase.

In their quest to produce quality tea in harmony with the biodiversity of the land on which it grows, the few tea-growing enthusiasts in France often work on small farms and are proponents of sustainable agriculture with a leaning towards organic practices. In mainland France, around two hundred kilograms of tea are processed to go on sale, which is very little. Of the forty or so tea growers, only five process tea to go to market. Other producers grow leaves which are then sold or used for experimenting. As such, French tea is a rare gem with high prices.

Around twelve tea farms in Brittany,* including Filleule des Fées (30,000 plants and cuttings).

Around five tea farms in French Basque Country located in Ustaritz, Sainte-Engrace, Urrugne and Saint-Jean-de-Luz: Ilgora –Herriko tea farm (1,900 tea plants covering 2,000 m2).

The Pyrenees: Arrieulat tea farm (2,000 tea plants covering 5,000 m2).

*Discover in store our very first French black tea, produced in Brittany and available in limited quantity.

A FUTURE FRENCH CERTIFICATION LABEL?

1.5 tons of tea was produced in 2023, including 1.3 tons on Reunion Island.

Founded in April 2021, the French National Association for the Promotion of French Tea Producers (ANVPTF) has created a “French-grown tea” certification label. Keen to protect the designation of origin of their teas, it prevents tea produced in other countries from being sold under the designation “made in France.” It is assigned to producers farming more than one hectare of land and who process their teas in France in accordance with environmental standards. It is renewed every year after an audit and aims to promote French and local tea-growing expertise.

Tea growing is a relatively new exploit in France. Unlike the Asians, the French do not have two thousand years of tea-growing expertise. So those looking to launch into the business are faced with many challenges.

Adapting tea plants to our soils and climate

This is the first challenge. The tea plant particularly likes acidic soils and flourishes when planted at altitude and on steep slopes which favor good water drainage. There are two regions particularly suited to tea growing: Brittany and the Pyrenees. These two regions both boast suitable levels of humidity, a climate that alternates between heavy rain and sunny spells, and a variation in temperatures between day and night – conditions that the tea plant loves. Soils with a pH between 5.5 and 6.5 are ideal for the Camellia sinensis to flourish.

The conditions for planting the tea plant are therefore incredibly challenging, making it hard to find areas in France which could achieve significant tea yields (except in the regions mentioned).

It takes an average of three years for the tea plant to settle into the soil and produce leaves suitable for tea making. It reaches full production maturity after six years. Therefore, leaf picking and processing does not offer an immediate return on investment. What’s more, one hectare of French-grown tea plants produces on average three hundred kilograms of tea, compared to six hundred kilograms of Grands Crus and three thousand kilograms of so-called “common consumption” teas on the same surface area in Asia. Finally, unlike China or India, labor is a significant cost, which is not yet profitable in terms of yield harvested. Therefore, France cannot currently rival traditional tea-producing countries in terms of quantities produced and the approximate two hundred kilograms produced in mainland France are sold at high prices.

Tea production in France is only in its infancy. However, what is emerging is a drive to create exceptional quality, groundbreaking tea, with complex aromas and a focus on the freshness of a locally produced cru, while collaborating closely with those in the gastronomic world to promote artisanal practices. While French tea remains a niche produce, the fields of innovation to explore within the sector are immense!

It takes an average of three years for the tea plant to be mature enough to produce leaves suitable for plucking.

Tea plants flourish on hilly slopes among rolling landscapes.

Tea, so fresh and so green! While some teas like first flush teas fully express their character in the three months after being processed, others reveal their secrets over time.

Fermented teas are the most iconic example of this, but did you know that all tea colors can stand the test of time?

By Elena Di Benedetto

The story behind aged tea coincides with that of fermented tea, whose thousand-year-old roots can be traced back to the Golden Triangle region in South-East Asia. Sometimes referred to as “tea for aging,” for it can be stored for a long time, fermented tea shares many parallels with fine wines: both can be given a vintage and improve with age, allowing their complex and evolving aromatic profile to develop. But fermented teas are far from being one and all the same, and the way they are processed and aged vary greatly depending on the type of tea.

It all began with the mao cha. Plucked, withered, pan-roasted for partial fixation, rolled and then, most often than not, left out to dry in the sun, the leaves of this tea are then used to make the most famous fermented tea: Pu Erh. What is so distinctive about this tea is that it is fermented, a process which can be done naturally or accelerated. “Raw” or sheng Pu Erh, is aged naturally: mao cha tea is compressed into round cakes, then may be left to oxidize, then ferment for up to several decades, either in warm, humid basements like in Hong Kong, or in drier conditions like in Taiwan. Sheng Pu Erh initially reveals a rather floral taste; after ten years, it develops more fruity and mineral notes; after which does it then reveal its woody aromas. These matured teas have amassed a following, and in the 1970s demand was so high that some manufacturers tried to make Pu Erh more quickly by speeding up the fermentation process. After a being left to ferment under a tarpaulin for a month or two at a temperature of around 50 °C, the mao cha is then ready to be compressed into cakes, bricks, in the shape of a mushroom or bird’s nest, or even left as loose tea leaves. These “cooked” or shu Pu Erh are sweet with earthy, mossy notes. They are the most common Pu Erh teas on the market today.

While all types of Pu Erh tea were for a long time only made from mao cha, these days the latter is valued as a tea in its own right and enjoyed in its natural, loose-leaf state, or rather, as an uncompressed sheng Pu Erh! Many excellently crafted mao cha teas regularly come to market, with a varied flavor profile, ranging from mineral, fruity, even vegetal and musky notes. Mao cha still has a lot to offer even the most curious palates.

In the Golden Triangle region, Thailand and even Laos have been producing fermented teas for several centuries. They are renowned for their mao cha teas and the local, large-leaf tea plants which flourish in this region of

Fermentation is the process in which certain organic materials are transformed through the action of good bacteria. It can be found everywhere in our daily lives, in yogurts, pickles, sourdough bread and even in certain teas! On the other hand, oxidation is a chemical reaction that occurs when the enzyme oxidase contained in the tea leaf is exposed to oxygen. This process particularly occurs when the leaves are bruised or manipulated, as is the case for black tea (fully oxidized) or oolong (partially oxidized).

the world lend themselves particularly well to the production of fermented tea. Cao Bo in Vietnam, Chiang Ma in Thailand and Bokeo in Laos, these are all exclusive terroirs which produce exceptional fermented teas.

In Korea, producers also make fermented tea by adapting the production process to their own traditions: the leaves are oxidized and fermented in an earthenware jar called an onggi, before being left to age, which gives the tea a rather unusual complexity. This technique is not dissimilar to the one used in Georgia to make wine, where they use large earthenware vessels called qvevri!

In Japan, the parallel with wines and spirits continues: Yamabuki Nadeshiko is a very rare Japanese fermented tea that is made using a koji, a yeast fermentation starter usually used to make sake! After being fermented for around ten days, the tea reveals particular licorice notes. There are also awa bancha and sannen bancha, regional Japanese teas harvested in summer or fall, which require time for their full potential to be revealed. While the former is lacto-fermented in water for ten to twenty days before being dried on straw mats, the latter is harvested then the leaves and stems are bundled together and left to age for three years before being processed for drinking. It is hard to pigeonhole these teas as they blur the lines between the colors: awa bancha is considered a fermented tea, just like Yamabuki Nadeshiko even though it is processed like a green tea, while sannen bancha is aged but not fermented, falling under the green tea category.

There are still other exceptions to the Japanese green tea tradition, like shincha and gyokuro. While first-flush teas harvested in spring are revered for their unbeatable freshness and verdant tones, it might seem absurd to wait more than a few months to enjoy them. However, kuradashi tea is one exception to this rule. This ancient method for aging green tea is the traditional way of making gyokuro tea. The ichibancha* spring harvest is sealed in a box and left to age for six months in a special tea storage outhouse (ochakura). Several months later, this precious tea comes out of its hibernation and is revealed during the kuradashi no gi ceremony. The first sip is like experiencing a spring awakening for the second time, only in fall. Kuradashi enhances the intensity of the umami flavor, creating an almost creamy roundness and complexifying the flavor profile. The kuradashi method offers a genuine newfound freshness, enhancing the tea by making time an ally.

However, not all aged teas require large-scale manufacturing and can actually be aged in your very own home: fermented teas can be aged in your basement, and many knowledgeable hobbyists even age white tea themselves, to be enjoyed several years later. With regards to white tea, there is even a saying in China that goes: “white tea aged for three years is like medicine, after seven years it becomes a treasure.”

“You can experiment by lightly roasting tea at home, to reveal and create new aromatic notes. All you need is a heat source, a small wok and some tea.”

In Taiwan, the method is even different, as some partially-oxidized teas stay within a family for generations! Of course, the island has a rather humid climate, so for an oolong tea to retain its freshness it needs to be heavily roasted to begin with or regularly re-roasted to remove any excess water. This gives the tea its evolving flavor profile and an aromatic complexity reminiscent of dried flowers, candied fruits and incense – and the balance of these notes is unique to each family. The tea can then be stored for a long time, while also perpetuating a priceless legacy, and all it costs is a few moments spent manipulating the leaves.

The tea world never ceases to amaze tea drinkers with its new innovation and traditional practices. And while time has always been a crucial factor for harvesting, when it comes to taste, it can be used to our advantage, to give tea the time to reveal all its secrets. •

Try a vertical tasting across several consecutive years, comparing a Vietnamese Cao Bo Mao Cha tea from 2017 to 2021. Explore each vintage’s astringency and notice how their floral and mineral notes evolve over the years.

*Ichibancha: first flush Japanese green tea harvested at the very start of spring.

comes in many different shapes, shown here as small bird’s nests, cakes or even loose leaf tea.

Let me take you on a journey of discovery of a treasure in China, the country considered the birthplace of tea. Of all the tea in China, the Yin Zhen, or “Silver Needle,” is one of the most prized. This delicately subtle white tea is crafted entirely from tender buds and is considered one of the finest teas around.

Désirée Picarelli is the manager of the Rue Tronchet store in Paris. She used to be an Italian teacher before joining Palais des Thés twelve years ago. She obtained her master tea sommelier certificate in 2017, before becoming a teacher at the Tea School and bringing a wealth of teaching experience to the role. Her passion for Japan and its culture, traditions and tea motivated her towards a career in tea.

By Désirée Picarelli

The story behind the origin of Yin Zhen dates back to 1796 during the Qing dynasty, a time when white tea production techniques as we know them today first emerged. A few years later, a new tea plant variety, the da bai or “big white”, appeared in the region, whose name was chosen for the size and white color of its downy, fuzzy buds. The delicious Yin Zhen that we shall discover today comes from this exact cultivar.

This tea never ceases to amaze me. While its production process may seem relatively simple (there are only two steps to the process), it requires in-depth knowledge and a mastery of skill of the tea leaf itself [1]. It begins with the harvesting stage, which itself is rather “unusual,” as only the buds are picked before being left to wither in the sun for two days. This is the point at which all the producer’s talent comes into play, for they must master the level of residual oxidation which occurs during the withering stage, and stop the process by drying the

leaves naturally in the sun. It means playing around with the weather conditions, getting the right balance between the sunshine, humidity and temperature, all unpredictable factors which can jeopardize the process in no time at all. The leaves are then carefully left to dry,

completing the production process. In his novel, The Tea Master (1981), Yasushi Inoue sums up perfectly this mastery of skill: “We would like to put it down to genius, but it is surely the result of a lot of effort…”

The art of kooridashi

I like to prepare this Chinese tea according to kooridashi, a brewing method traditionally reserved for Japanese teas. This cold-brew technique is a really gentle way to bring out the Yin Zhen’s full depth of flavor and subtle nuances [2]. In fact, this method can be used for all your favorite single estate teas, creating a surprisingly refreshing result.

To infuse my tea, I will use a shiboridashi, a traditional Japanese teapot made from Tokoname clay. I add three grams of Yin Zhen, taking the time to admire the wonderful contrast between the black clay pot and the silvery white buds. I add a couple of ice cubes, letting them melt slowly over the tea leaves. This may take a while, even up to an hour, depending on the room temperature.

Once the ice has melted, I pour the tea liquor into my cup [3] . This moment is precious. The honeyed, floral notes are particularly present, while the sweet flavor and oily texture cover my palate with a delicious sensation. Every time I make this tea, I rediscover its sophisticated aromas and subtle freshness.

I like to enhance this exquisite white tea by pairing it with a dessert that reminds me of my homeland, Italy. I place a large spoonful of buffalo ricotta on a plate and drizzle it with wildflower honey and a sprinkling of crushed Bronte pistachios. The pairing elevates the Yin Zhen’s floral, nutty notes and increases it creamy texture. It is the perfect sweet finale to any meal! •

Yin Zhen

Cultivar Dai Bai Hao

OriGiN Yunnan (Mang Bai)

BrEWiNG GuiDE

→ Seven minutes at 80 °C or one hour using the kooridashi technique

FOOD PairiNGS Buffalo ricotta with pistachios

Surprise your guests with a smoked tea pissaladière, the perfect snack for drinks with friends or an early fall dinner. Used in all its forms, this tea adds depth to this famous southern French classic.

Serves eight

For the tea

6 g smoked tea

(Dharamsala Smoked, Guava tree smoke)

200 ml filtered water

For the pastry

10 g (or 2 tbsp) of smoked tea

200 g flour, sieved

100 g butter

Salt

For the topping

800 g onions

5 tbsp olive oil

Salt

Marjoram, oregano or herbes de Provence

Anchovies (optional)

Olives (optional)

For the tea

Heat the water to 90 °C and brew the tea for ten minutes. Leave the liquor to cool.

For the pastry

Grind the dry tea leaves to a powder by bashing them.

Cut the cold butter into small chunks and add to a bowl with the flour, 50 ml of cold tea liquor, a pinch of salt and the ground tea leaves. Using your hands, mix to form a smooth dough. Set aside in the fridge for thirty minutes.

For the topping

Peel the onions. Cut in half then slice into 5 mm-thick slices. Soften the onions in the olive oil over a low heat. Add a pinch of salt.

When they start to color, add the tea liquor. Cover and leave to simmer over a medium heat for thirty to forty minutes until the onions are soft and translucent. Remove the lid and continue cooking for a further ten minutes or so until all the liquid has evaporated.

Pre-heat the oven to 210 °C.

Roll out the pastry, then line and mold into the tart tin. Transfer the onions to the tart tin, shaking off any excess liquid before spreading across the base.

Top with anchovies and olives, adjusting to your taste. Sprinkle with your choice of herbs. Bake in the oven for thirty minutes, until the edges of the pastry and the onions start to turn golden brown.

Make extra pastry and cut into small rounds. Top with your choice of herbs, a little salt and a drizzle of olive oil. Bake then eat hot out of the oven, as a tasty snack.

Did you know that American independence was partly due to tea? And that the Boston Tea Party was not actually a social gathering but rather a significant event centered around the famous imported drink? Let’s head over to the Americas to discover this key moment in the history of tea – and the world!

By Cassandra Bagneris

The history of the Boston Tea Party begins in the eighteenth century, at a time when Great Britain was experiencing a period of financial difficulty after having been weakened by the Seven Years’ War against France (1756-1763).

To avoid bankruptcy, the British Parliament decided to introduce new taxes in its Thirteen American Colonies, including the Townshend Acts, named after Charles Townshend, the Chancellor of the Exchequer. Enacted on November 20, 1767, these laws aimed to tax products imported by the colonies, such as porcelain, paint, lead, glass... and tea.

These measures were expected to generate around forty thousand pounds, mainly from a tax on tea. What a windfall! However, colonists found this difficult to bear and so contested the measures. There was growing tension leading to the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770, during which five colonists were killed and six others injured by British soldiers.

During these hostile times, American colonists, who were big tea drinkers, began to boycott British East India Company (EIC) imports, favoring smuggled Dutch tea to the detriment of tea from the British colonies. In the port of New York, three-quarters of tea shipments entered illegally. This proved to be fearsome competition for the EIC, which found itself with millions of pounds of unsold tea on its hands.

To avoid bankruptcy, Prime Minister Lord North granted the EIC a monopoly on the sale of tea in the colonies in 1773. The Tea Act of May 10, 1773 allowed the EIC to directly ship its tea duty-free to America, enabling them to offer lower prices than other importers, including those on the black market. However, colonists were required to pay a small import duty of three pence.

In response to the various laws put in place, Samuel Adams, a political figure in Boston, took charge of the Sons of Liberty. This secret group of revolutionary patriots was made up

of representatives from the thirteen colonies who strongly opposed the taxes imposed by the Crown. They went on to organize several actions aimed at provoking confrontation.

On December 16, 1773, Samuel Adams gathered the residents of Boston at the Old South Meeting House, a church that became a meeting place after the Boston Massacre. People came out in force, voting against paying taxes on tea and refusing to let three EIC ships that had recently arrived at the port from

unloading their tea. That same evening, as the governor had refused to grant permission for the ships to be sent back to Great Britain and had ordered for the tea to be unloaded, a group of men (probably members of the Sons of Liberty) dressed up in Mohawk (Native Americans) warrior disguises and boarded the three ships. They destroyed around forty-five tons of tea worth around ten thousand pounds, by dumping it into the sea in protest. This event came to be known as the Boston Tea Party. When the news broke, the British parliament responded swiftly, adopting a series of

punitive measures. They were evocatively named the Intolerable Acts. These acts included the closure of Boston port until colonists paid for the destroyed tea cargo. These laws provoked indignation throughout the American colonies, making the Boston Tea Party one of the triggering factors of the American War of Independence.

In response, the thirteen colonies formed the Continental Congress, a legislative body in Philadelphia.

War broke out on April 19, 1775 in Massachusetts, between American patriots against British forces and loyalists. On July

4, 1776, the United States Declaration of Independence was signed in Philadelphia, marking the formal end of the colonies’ cooperation to British rule. The Boston Tea Party was far from being an isolated case, acting as a catalyst for colonial defiance against British imperialism. To think that tea played a role in the emancipation of the United States as a country... •

Dao Pu Erh is a fermented tea, a type of tea whose taste improves with age (see p. 22). This particularity is linked to its production method, which involves a long fermentation. The most famous of its kind is Pu Erh, which were originally produced in and around the town of the same name in China. Vietnam also produces some delicious Pu Erh teas, including one made by the Dao, an ethnic minority in the north of the country.

Pu Erh: the most famous fermented tea

In the seventh century during the Tang dynasty, tea was mainly used as a condiment. It soon became an everyday beverage and was used as currency to swap for Tibetan horses. The Chinese decided to compress the leaves into round discs, making it more compact and less bulky to transport on horseback (see p. 20-25, Bruits de Palais n° 92). At the end of their long journeys, the traders realized that the tea had fermented naturally, offering unique flavor profiles. This discovery marked the birth of Pu Erh tea, which is

still made today in disc form, as well as bricks, mini “bird’s nest” cakes or loose leaf. This type of tea can be left to age for many years, to let all the nuances of its flavor fully develop.

Fermented tea production is very common in the Golden Triangle region, on the southern border of the Yunnan province. This high mountain region is home to many ethnic minorities who produce very good quality teas. As is the case of the Dao people, who are renowned for their dexterity in tea making.

While the Dao still continue to produce delicious Pu Erh tea, their traditions do not lie in fermented tea. It is in fact their neighbors in Hong Kong who took advantage of the Dao’s tea-making expertise to satisfy their own demand for fermented tea. Until the 1990s, almost all the tea produced in the huge Cao Bo tea factory was exported to the city-state.

Today, the Dao continue to exercise their talents and offer high quality teas to the whole world.

Among them is the Dao Pu Erh, a shu Pu Erh with an accelerated fermentation process. Beneficial micro-organisms work away at the leaves which, when fermented for more than three months, soften and develop a very recognizable flavor profile, similar to a Chinese Pu Erh tea. Like the latter, these teas also pair perfectly with hard cheeses, like a comté aged

for twenty-four months, making for a mix of deep woody tones with slightly sweet undertones.

But Dao Pu Erh also offers some other powerful notes which may appear occasionally, like licorice, which completes the earthy and mushroom tones. The effect of all these different flavors together evoke the forest in which the Dao grow their tea plants. •

When left unpruned, some tea plants’ “picking tables” can grow up to several meters high.

Fall is here, bringing with it the desire to snuggle up warm with a nice cup of tea. With our selection of teaware, making tea never felt so stylish!

1. Mister Yan’s Mao Cha

Ref. D3223AM – € 42 per 100 g

2. First flush Chinese yellow tea

Ref. 203A24AM – € 48 per 100 g

3. Clay shiboridashi (5 cl)

Ref. N366 – € 100

4. Kumo tea ceremony bowl

Ref. N076 – € 57

5. Ceramic infuser mug (44 cl)

Ref. N367 – € 26

6. Osaka teapot (0.9 l)

Ref. M205 – € 46

7. Glass infuser mug (45 cl)

Ref. N327 – € 25

Our commitment has always been to bring you the best teas possible, sustainably and responsibly made in harmony with local biodiversity. Despite the introduction of EU food safety regulations, only a small percentage of food on sale is tested by public authorities.

This prompted us to create the SafeTea label to guarantee that the teas bearing this logo have been independently tested to meet EU regulations concerning pesticide residue standards. Céline Colin, supply chain manager at Palais des Thés, tells us more about this game-changing move.

Why was the SafeTea label created?

Céline Colin— The main reason is that we want to guarantee a consistent level of quality to our customers by offering clean teas. The SafeTea label is also in keeping with our desire to preserve biodiversity in tea-producing regions. The principle is simple, rather than “randomly” testing batches, which is standard practice, we now systematically control all the batches of tea we receive. We introduced this measure in 2018 by informing all our producers that all batches of tea would be systematically controlled. If a batch is non-compliant, so the pesticide residues are above the permitted levels defined by the European Union (EU standard 396/2005), we help them to produce teas which are compliant. We are truly putting our money where our mouth is, so to speak, and our action has had an incredibly positive impact on the way tea is produced! It has encouraged producers to adopt much more responsible farming and production practices. This is ultimately a virtuous circle.

What progress has been made since the launch of SafeTea?

Has there been an improvement in the compliance rate on the batches controlled?

C. C.— In 2018, we refused and returned around 6 percent of the batches of tea received due to their non-compliance. Six years later this figure has reduced by three and in 2023, only nine teas were non-compliant and so were destroyed. Furthermore, there was a significant decrease in the number of pesticide residue molecules present in all our batches, from all sources combined. While we used to detect an average of seven pesticides per analysis

(which is below the limit!), nowadays only an average of one pesticide is found in our teas per analysis. It all comes down to the enormous effort our farmers and producers made to stop or drastically limit the use of phytosanitary products for the teas they produce for Palais des Thés.

What is the difference between a SafeTea-certified tea and a tea certified organic?

C. C.—At Palais des Thés, we sell both organic and non-organic teas. In 2023, 36 percent of our flavored creations were converted to organic, and we selected 68 percent of our single estate teas as organic. With SafeTea, we provide proof of result as we systematically analyze every batch of tea that has not been produced using organic farming practices, to ensure that no pesticides or pesticide residues beyond authorized limits are found. The SafeTea procedure is currently even stricter than the controls carried out on organic products, since it concerns each harvest rather than just a few batches. Unlike SafeTea, the organic certification is about best efforts and is not results-orientated.

What impact has the SafeTea certification had on the conditions of purchase, the relationships with producers and even on the tea itself?

C. C.—With our producers, we have forged a mutually beneficial relationship. Economically speaking, this initially had an impact on their yield as pesticides were used less, but it also enables them to produce better quality tea, which we purchase at a fair price taking into account all the efforts made. •

Bruits de Palais is a Palais des Thés

publication

Editorial team

Lucile Block de Friberg, B éné dicte

Bortoli, Chlo é Douzal, Mathias Minet

Translation and proofreading

Kate Maidens

Art direction and layout

Prototype.paris

Styling

Sarah Vasseghi

Illustrations

Sabine Forget

Imaging & retouching services

Key Graphic

Printing Printed in August 2024 by Groupe Prenant (France)

Palais des Thés

All translation, adaptation and reproduction rights in any form are reserved for all countries.

Photo credits

Ana Miyoshi: front cover • Guillaume Czerw: p.2, 25, 26, 27, 29, 34-35 • François-Xavier Delmas: p.4, 20-21, 23, 33, 36, 38, 39 • Yann Sowinksi and Léo Dugué-Perrin: p.6-13 • Kenyon Manchego: p.32, 36

Customer service

+33 (0)1 43 56 90 90

Cost of a local call (in France) Monday to Saturday 9am-6pm

Corporate gifts

+33 (0)1 73 72 51 47

Cost of a local call (in France) Monday to Friday 9am-6pm

Werner Lambersy