St. Croix Resilience Plan

Fall 2022

University of Pennsylvania

Weitzman School of Design

Image: UPenn Studio

Image: UPenn Studio

Fall 2022

University of Pennsylvania

Weitzman School of Design

Image: UPenn Studio

Image: UPenn Studio

The following adaptation plan is the culmination of a semester-long study of climate-related effects on the environment, infrastructure, and people of St. Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Through the lens of city planning and environmental studies, students engaged with local partners in USVI to better understand the challenges and opportunities associated with climate change resilience on the island. Students had the opportunity to travel to St. Croix meeting with local partners, leaders, and residents to gain a first-hand perspective into the complex social, physical, and environmental factors informing the Island’s responses to extreme weather events, sea level

rise, and other impacts of climate change. Informed by the experiences and knowledge shared from the local partners, data collected on the island, and remote research, students developed a series of adaptation strategies for target areas or subjects on the island which are reflected in this document. By no means a comprehensive adaptation strategy for the island of St. Croix or USVI, this project is intended to provide a summary of student’s observations from four months of studying the island and, hopefully, offer some inspiration or alternative ideas for St. Croix’s future resilience.

This project was conducted by the St. Croix Resilience Studio at the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn Studio). Led by Scott Page and Jaime Granger, 15 master’s students from a variety of backgrounds in city planning and environmental studies worked together to investigate resilience in St. Croix.

Master of Environmental Science

Master of City Planning

Housing, Community, and Economic Development

Land Use and Environmental Planning

Public Private Development

Urban Design

In the first weeks of the studio students created shared definitions for climate change terminology and researched case studies of adaptation strategies worldwide.

The students then transitioned into research about St. Croix to establish foundational knowledge about the island.

Near the conclusion of the learning phase, the entire studio traveled to St. Croix for seven days. During the trip students collected information about existing conditions of the environment and urban centers that could not be uncovered remotely. They also met with several community leaders and stakeholders from a variety of backgrounds and interests.

After returning from St. Croix, the studio worked to refine their research into a comprehensive analysis structured around a driving narrative. This also helped inspire the studio’s shared definition of resilience for St. Croix.

In the final phase, the studio broke out into small teams to tackle specific resilience projects for St. Croix. These projects cover a variety of topics based on student interest in areas of need uncovered through the analysis phase and working with studio partners.

This project would not have been possible without the support of our partners. Throughout the semester the studio has collaborated with local leaders in St. Croix and others who are actively involved with resilience and climate work in St. Croix. Additional partners provided case study and precedent presentations through guest lectures to inform and inspire. These partners have generously shared their time and knowledge and provided invaluable input. Thank you!

Scott Bishop Bishop Land Design

Kirk Chewning Cane Bay Partners

Teresa Crean Director of Planning, Building and Resiliency (Barrington, RI)

Haley Cutler St. Croix Foundation

Rich DiFede

Gold Coast Yachts

Joe Dwyer

NOAA’s CAP (RISA) program, Climate Program Office

Ryan Flegal Feather Leaf Inn

Frandelle Gerard

Crucian Heritage and Nature Tourism (CHANT)

Greg Guannel

Caribbean Green Technology Center, University of the Virgin Islands

St. Croix St. Thomas Mainland

Wayne Huddleston Small Business Administration

Deanna James St. Croix Foundation

Daryl Jaschen Virgin Islands Territorial Emergency Management Agency (VITEMA)

Josh Lippert Former Floodplain Manager, City of Philadelphia

Hilary Lohmann

Department of Planning and Natural Resources (DPNR), USVI

Kirsten McGregor SAGAX Associates

Gerville Rene Larsen Taller Larjas LLC

Richard Roark OLIN

Jessica Ward The Nature Conservancy

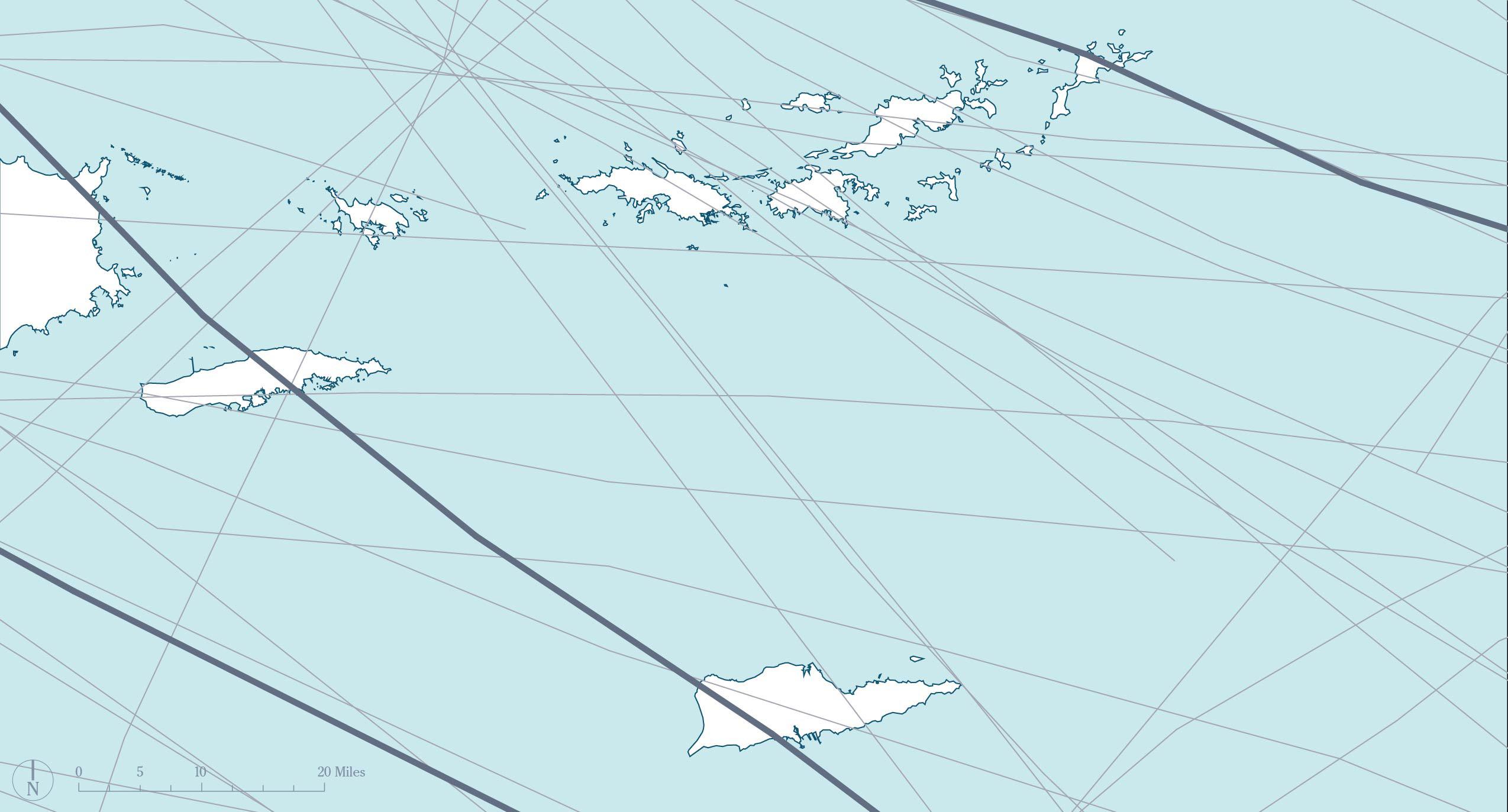

St. Croix is one of the many islands that make up the Caribbean region. The island is nestled in the warm waters of the Caribbean Sea brought across the Atlantic Ocean via the North Atlantic current.1 St. Croix is one of the 4 islands that make up the United States Virgin Islands (USVI), a US territory. USVI are the westernmost islands of the Lesser Antilles, neighbored to the west by Puerto Rico and to the east by the British Virgin Islands (BVI). St. Croix is the largest and most southern island in USVI, with St. Thomas, St. John, and Water Island lying approximately 35 miles to the north.

St. Croix itself is a beautiful island with mountains, moist forests, industry, and a barrier reef that stretches around the entire island shelf. The two main towns of St. Croix include Christiansted on the north shore and Frederiksted on the west shore. The island covers an area of 84 square miles and is 7 miles wide and 28 miles long.2

St. Croix has beautiful landscapes, crystal clear Caribbean waters, and a rich culture.

Christiansted

Christiansted

St. Thomas, St. John, and Water Island (USVI)

British Virgin Islands

St. Thomas, St. John, and Water Island (USVI)

British Virgin Islands

St. Croix is filled to the brim with life and opportunity. The Crucian culture is beloved by residents and visitors and boasts beautiful art, great music, and delicious food. The island’s identity is grounded in its rich history of resilience. The boardwalks along the waterfronts of Christiansted and Frederiksted welcome visitors to eat and shop with beautiful sea views. Miles of beaches let you touch the crystal-clear Caribbean waters and soak up the sun.

However, St. Croix is also facing many challenges. As the climate crisis worsens, St. Croix is feeling the impact

of severe weather events, such as the destruction caused by Hurricane Maria in 2017. Severe weather paired with declining infrastructure creates increased risks from hazards such as flooding, erosion, and pollution. These challenges take a toll on the natural environment as well, threatening beaches, coral reefs, and mangroves that help protect the island. While these circumstances are putting St. Croix at risk, the natural resilience of Crucians and their desire to protect their island and their community keep St. Croix strong. These diverse opportunities and challenges are the focus of this studio.

The following chapters of this plan cover an analysis of St. Croix’s current conditions conducted during this studio. Island ecologies, impacts of colonialism, infrastructure, equity, and the effects of climate change were all investigated in order to establish a baseline understanding of St. Croix’s resilience today. Following the analysis, this plan presents a common resilience

definition for St. Croix that has guided the work of the studio. Finally, six resilience projects will address the challenges and opportunities identified for St. Croix and present just a handful of ways that Crucians can fortify their resilience to climate, social, and environmental threats in the years to come.

1. “Geography Of The Caribbean,” n.d. https://www.worldatlas.com/geography/geography-ofthe-caribbean.html.

2. 2. “St. Croix: Facts & History,” n.d. https://www.vinow.com/stcroix/history/.

The history of St. Croix can be represented by resiliency in the face of colonialism. The island was first inhabited by indigenous peoples including the Arawaks and the Tainos before being claimed by the Spanish in the early 1500s. It was later occupied by the Dutch, and then the Danish, who established the first permanent European settlement on the island in 1653.1 The Danish colonized the island to act as an economic hub for the nation, becoming the ‘Garden of the Indies’ where enslaved islanders enriched their colonizers through the production of sugar cane.

In 1917, the Danish West Indies were sold to the United States, the islands latest colonizer, and St. Croix became a part of the U.S. Virgin Islands. Today, St. Croix remains a popular tourist destination and is home to a diverse population, with roots in the Caribbean and Africa, who in the face of colonialism have remained a vibrant and resilient people.2

Enslaved people on St. Croix endure 355 years of the sugar cane and slave trade from six different colonizers.5

St. Croix was inhabited by the Arawak Indian tribe as early as 800 AD, followed by the Taino people and eventually the Carib people about a century before Columbus arrived.3

November 14, 1493

The Carib people fought against the Spanish upon their arrival at Salt River Bay. This represents the first violent altercation between the Old World and the New. War continued between the Caribs and Spaniards for nearly a century.4

The island known today as St. Croix has endured seven different colonizers on its land for 529 years and counting.

General Buddhoe led a slave rebellion and demanded that Governor-General Scholten of Denmark emancipate enslaved people on St. Croix. Despite the emancipation, former slaves would continue to be subjected to forced labor due to laws that were created to limit their freedom.6

St. Croix, St. John, and St. Thomas were purchased by the United States of America from the Danish government for military reasons. The U.S. represents the last and current power asserting imperial rule.8

Fireburn revolt ends the slave-like conditions that persisted after emancipation. Over 879 acres of sugar cane were burned, and many laborers were killed. The revolt was led by four women known as the “Queens” of the revolt- Queen Mary, Agnes, Mathilda, and Susanna- who were later sentenced and jailed in Denmark.7

The government of St. Croix is organized as a territorial government within the federal system of the United States. St. Croix, St. Thomas, St. John, and Water Island make up the US Virgin Islands, a group of islands in the Caribbean Sea that were acquired by the US from Denmark in 1917.

St. Croix’s government is composed of three branches: the executive, the legislative, and the judicial. The executive branch is led by the Governor of the Virgin Islands –currently Governor Albert Bryan Jr, who was elected by popular vote in 2018. The Governor is responsible for implementing the laws of the territory and for overseeing the various agencies and departments that make up the executive branch.9

The legislative branch of the government of St. Croix is the Virgin Islands Legislature, which consists of a 15-member Senate and a 31-member House of Representatives. The members of the Legislature are elected by the people of St. Croix to serve fouryear terms. The Legislature has the power to pass laws and to approve the budget for the territory.10

The island’s judicial branch is

as states. composed of the Virgin Islands Superior Court, the Virgin Islands Court of Appeals, and the Virgin Islands Supreme Court. The Superior Court is the trial court of the territory and has jurisdiction over a variety of civil and criminal cases. The Court of Appeals and the Supreme Court are the territory’s intermediate and highest courts, respectively, and have the power to review decisions made by the lower courts.11

In addition to the territorial government, St. Croix is also subject to the laws and regulations of the federal government of the United States. The US Constitution applies to the territory, and the people of St. Croix are represented in Congress by a delegate to the House of Representatives – Congresswoman Stacey Plaskett - who has a voice in congressional debates but does not have the right to vote on the final passage of legislation.

The people of St. Croix, along with the people of the other US territories (such as Puerto Rico and Guam), are not represented in the US Senate and do not have the right to vote in presidential elections. As a territory of the United States, St. Croix does not

Despite being a U.S. territory, St. Croix and USVI still do not have the same rights

have voting power in federal elections. Because territories are not granted the same level of political representation as states, residents of St. Croix do not have the same rights and privileges as citizens of the mainland.12

Overall, the government of St. Croix operates in a similar manner to the governments of the other states and

territories of the United States, with one major exception, the right to vote. The existing power structure between the United States and St. Croix bears close similarities to the island’s previous colonial regimes.

St. Croix has shifted core industries since its initial colonization. Early in the 18th century, the Island’s economy was primarily agriculture based, focusing on sugar cane production, and relying on slave labor. It was in this period that the island was known as the Garden of the West Indies due to its high production of sugar cane. After the abolition of slavery in the Danish West Indies in 1848, the island’s economy struggled, and many plantation owners went bankrupt. The

plantation economy was eventually replaced by a system of small farms, but these were not able to support the population, leading many people to leave the island in search of work and the island to continue to find its economic identity.13

After the United States acquired St. Croix from the Danish West Indies, the federal government invested in infrastructure on the island, including roads and ports, and St. Croix became

St. Croix’s population has remained vibrant and resilient without clear economic footing.“The Mill Yard” by William Clark, 1823 (image: The British Library)

an important center of trade and commerce in the Caribbean.14

Between 1966 and 2018, oil refineries were the primary industry on St. Croix. It was the main source of income for many as the HOVENSA refinery was one of the largest refineries in the western hemisphere. However, the toxicity of oil refining has left many who lived near the refineries suffering health complications due to their proximity to the toxic chemicals. In the past decade, the refinery closed, reopened to new ownership, and closed again following environmental violations.15

Today, St. Croix is a popular destination for tourists, with its white sandy beaches and historic towns, drawing visitors from around the world. It is also home to a vibrant local culture and a diverse population with roots in the Caribbean, Africa, and Europe. Around 30% of Crucians work in tourism related industries and around 20% have found work in government positions. Despite its history of colonization and economic struggles, St. Croix has retained its unique identity and continues to thrive as a vibrant, diverse, and resilient community.16 17

Resilience is deeply ingrained in the history, culture, and life of St. Croix. The island has been ruled under seven colonial powers over the past 529 years and yet continually shows immense strength. However, the impacts of colonialism are still felt today with vulnerable populations still bearing the burden of historic inequities.

The population of St. Croix is not a monolith--there are a multitude of ways to experience the island. The tourist experience differs greatly from the local reality, which also differs greatly from the experience of wealthy second homeowners. The wealth

disparities on the island are evident. The East End of the island is decorated with multi-million-dollar homes that could even have staff and sweeping views, while many of the buildings in Frederiksted remain uninhabitable after the destruction from the 2017 hurricanes. The impact of the 2017 hurricanes is very visible today as much of the infrastructure is still recovering.

Vulnerable populations still bear the burden of historic inequities.

Vacant Businesses

Recovering Community

Damaged Homes

In 2011, the Center for Disease Control created the Social Vulnerability Index, which uses various socioeconomic factors to determine the social vulnerability of an area, including unemployment, income, disability, and English proficiency.18 Since its creation, the Social Vulnerability Index has become an invaluable tool for analyzing and advocating for communities. In St. Croix, the most socially vulnerable areas are located around Christiansted, Frederiksted, and in the southwest portion of the island—just slightly west of key

industrial sites such as the Limetree Bay Oil Refinery and the Anguilla Landfill. Over 37% of the population lives in the top 10% of the most socially vulnerable estates.19 20

The most vulnerable estates are also majority Black and Hispanic/Latino communities. Racial disparities related to income and educational attainment are stark. White residents are likely to have higher incomes, while Black and Hispanic/Latino residents are more likely to live below the poverty level and lack a high school diploma.21

Data: 2010 Decennial Census of Island Areas Data: 2010 Decennial Census of Island

Seemingly contradictory to the social disparities present throughout the island, St. Croix has a high percentage of homeownership, with 56% owner-occupied units.22 St. Croix residents have an immense desire to be homeowners despite systemic roadblocks—many of them bypassing banks and achieving homeownership through mutual aid or their own construction.

However, despite this high percentage of homeowners, as of 2010, 22% of housing units were vacant.23 Further with many houses suffering damage from the 2017 hurricanes, it is likely that vacancy rates have only increased over the last decade.

As the island’s median income of just over $36,00024 and traditional mortgages or insurance is not the norm, many households may not have been able afford to rebuild, leaving many houses abandoned. Even in the towns of Christiansted and Frederiksted that are prime tourist destinations, abandoned structures, such as the one on the following page, are a common sight.

Over the last decade, the total number of housing units has grown by less than 1%,25 indicating that the island has struggled to produce new housing units, even with a high demand for housing for both Crucians and incoming disaster recovery workers.

In the wake of the 2017 Hurricanes, many homes have been damaged and abandoned, creating a high percentage of vacancy on St. Croix.

Given the changing outlook for St. Croix, the island is struggling to keep up with the modern challenges presented. This is not just on a social and economic level, but also on the infrastructure found on the island and its capacity to provide reliable resources. The following limitations begin to explain the constraints of infrastructure systems that have consequently taken a toll on the quality of life on the island.

There are 5 main infrastructures on the island of St. Croix:

1. Waste Management

2. Water

3. Energy

4. Transportation

5. Internet

Although these are five independent systems, they are closely intertwined and reliant on each other to provide services to the entire island. Because one closely impacts the others, they cannot be discussed independently of each other.

Infrastructure systems struggle to keep pace with modern challenges.

The U.S. Virgin Islands Waste Management Authority (VIWMA) is the governing body of waste management on St. Croix. There are two dumping sites servicing the island. However, illegal dumping is one of the major infrastructural issues on the island. This is partially due to inaccessibility. Residents are required to take their own waste to the sites; however, this is not always possible due to unpredictable hours of operation and tipping fees required

to dump which often exceeds what residents can afford to pay. Most recently the trash hauler strikes have caused an additional hurdle to waste management. Since 2019, VIWMA owes the trash haulers upwards of $6 million with an overall debt of $24 million.26 All of this has led to an increase in illegal dumping in various parts of the island and has had devastating impacts on other infrastructural systems and wildlife.

These five systems are closely intertwined and reliant on each other to provide services to the entire island.

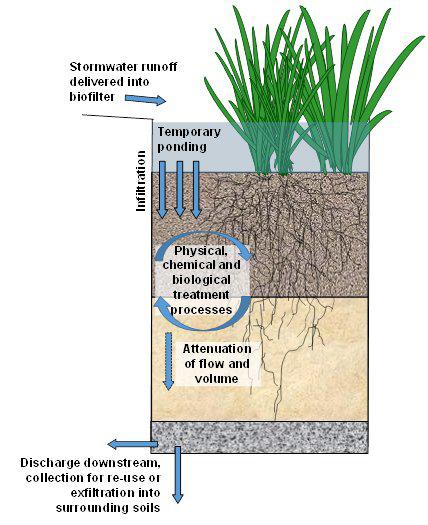

The water system can be broken down into two components; water mitigation through the guts network and water distribution through the potable water system and cisterns.

One of the systems most impacted by illegal dumping has been the guts system. The guts systems are important for directing water coming into the island from storm surge and

from excessive water intake. Guts come in two forms, natural and urban, with the biggest natural gut being on the south shore and draining 11 square miles. When trash is dumped in the path of a gut, it impedes drainage and causes backup and erosion from a clogged system. Additionally, many natural guts have been altered by drought on the island and being paved over.

The gut network directs water from storm surge and excessive water intake.

Gut Network Guts River Gut Jolly Hill Gut Salt River Creque Gut

The potable water system is the public water system on the island. It is a system of electrically powered pumps and pipes that source up to 2.2 billion gallons of drinking water per day from the island’s desalinization plant. However, since the pumps are electrically powered and the system has very few backup generators, when there are power outages, the population reliant on this water system does not have access to water. Additionally, the pipes are outdated and in need of upkeep, contributing to the limited reliability of the potable water system.

Because of the uncertainty of the water system, 70% of households on St. Croix have cisterns, in addition to tapping into the public water system.27 However, cisterns are also electrically powered and susceptible to power outages. Additionally, their design makes them vulnerable to contamination from animals and other sources, like the ones caused by the refinery oil spill in 2012.28

28% of households rely solely on the public water system.

St. Croix has its own electric grid capable of producing up to 140 megawatts daily.29 However, given how reliable other systems are on electricity and the islands susceptibility to power outages, this is a very fragile system. Since 2017, some improvements have been made to the system to make it more resilient to shock. Some of these improvements include more backup generators, inputting underground electric lines, and installing composite electric polls.

In addition to the traditional electric power grid, solar power is the primary form of renewable energy on the island. Even so, this only accounts for less than 10% of the island’s power usage.30 Petroleum is still the primary supplier of energy for St. Croix, in addition to being the biggest import and export making it an important resource for the island.

Petroleum meets nearly all of the island’s energy needs.Richmond Power Plant (Image: UPenn Studio)

Data: VITRAN

St. Croix has 4 main public bus routes, providing service from Frederiksted to Christiansted and the airport, among other destinations. The island also has a ferry port and cruise port. However, only 7% of the population uses public transit or walks.31 87% use a private car as their primary source of transportation.32 The condition

of roads provides an explanation for this division; 88% of roads have no sidewalks, 47% have no lighting, and 78% have no walkable destinations.33 This impacts accessibility to resources, safety concerns, as well as where people are willing to travel to and how far to access essential services like jobs, food, education, and health care.

88.6% of streets have no sidewalk. 78.2% of streets have no walkable destinations. 46.7% of streets have no lighting.

6 fiber-optic lines connect in St.

St. Croix is uniquely situated in the convergence of 6 fiber-optic lines servicing the entire region and beyond. Even so, 22% of households do not have internet access.34 This is an issue of accessibility, not supply, and can be attributed to a multitude of factors including cost and connection. Recently there have been efforts to eliminate this gap. ViNGN, a private company, has begun to install free Wi-Fi hotspots throughout the island. Currently, there are an estimated 27 locations.35

Croix.East End (Image: UPenn Studio)

Free Wi-Fi Hotspots

Community Wi-Fi Locations

St. Croix’s unique and complex natural environment plays an important role in the island’s opportunities and challenges. Rich soils on the island advanced a long agricultural history under colonialism. But in the present day, the island’s hot and dry climate puts stress on island systems, while natural threats like sargassum and flooding jeopardize island infrastructure. While the rich biodiversity of the island is a major selling point, contributing to its resilience and beauty, it is also under threat. In the midst of a changing climate, the protection of St. Croix’s natural environment will inform how the island responds to shocks now and into the future.

The climate of St. Croix is defined by its geographic positioning, which places it in the sub-tropical zone, where the trade winds blow along the length of the island. The island is warm all year, with little variation in average temperature between months or seasons. Temperatures are expected to

grow more extreme with the onset of climate change.36

Precipitation across the island is quite variable. The western part of the island receives substantially more precipitation than the east end. Annually, on average, it rains 30 inches in the east and 50 inches in the west and most rainfall occurs during the hurricane season.37 Precipitation varies substantially by season. The wettest month is September and the driest months are February and March. Severe seasonal droughts are a reoccurring problem on the island and are expected to worsen in the future.38

Terrestrial systems depend heavily on soil types. Soils contribute to the diversity of habitat types on the island and range from stony, to gravelly, sandy, silty, and loamy.39 Some soils are more suitable for agricultural practices than others, but these properties would not exist without the underlying geology of St. Croix. Much of St. Croix is well-suited for agriculture, and it has historically been known as the breadbasket of the Lesser Antilles.40

St. Croix is an elevated island with few regions existing below 70 feet;41 this topography influences how and where rainwater collects. When St. Croix formed, it was uplifted and created

an extensive reef system composed of limestone.42 The Limestone Plain separates the Northside Range and the East End Range. However, limestone and alluvial deposits (small areas with a specific geologic features) exist throughout the island. During rain events, the alluvial deposits are responsible for recharging the aquifer systems on St. Croix.43 The aquifers on St. Croix are associated with dissolved solids contaminants, complicating access to fresh water.44 The threats of drought on the island are compounded by the lack of fresh groundwater or freshwater streams.

Ecology

St. Croix’s natural environment is rich in unique features and biotic communities, from the rugged terrain of the upland forests to the grassy plains down the south coast and the immense coral reef system.45 The island’s natural resources provide a variety of habitats that sustain diverse species, and this rich biodiversity contributes to the resilient systems that support human life.

The marine shelf, reef system, and mangroves all have a unique relationship with the hydrology of St. Croix. The increasing depth of the marine shelf, composed of scattered elkhorn, brain, fire, boulder, and staghorn corals, and its associated

canyon help attenuate wave action.46 However, attenuating wave action is something mangroves and coral reefs do as well. Coral reefs can help stabilize shorelines and support a variety of marine life.

Likewise, mangroves stabilize shorelines and blossom with various wildlife species; additionally, mangroves sequester carbon and reduce flooding. Red, black, and white mangroves are located primarily along shorelines with red being the most salt and water-depth tolerant and white mangroves dominating inland regions and higher elevations.47 Mangroves are unique systems playing a specific role in marine and terrestrial ecosystems

72% of the island is categorized as subtropical dry habitat, with the remaining being categorized as subtropical moist forest.Subtropical dry forest (Image: UPenn Studio) Subtropical moist forest (Image: USDA)

Mangroves cover less than 1% of the island’s land and reefs cover 67% of its shelf.

due to their unique tolerance to flooding and salinity. The underwater habitats created by submerged mangrove roots are important to the life cycles of some economically relevant fish species. Unfortunately, the USVI has lost 50% of mangrove habitats between 1980 and 2005. The largest mangrove forest on St. Croix was destroyed in the 1960s to build the island’s oil refinery. The loss of these special habitats threatens the biodiversity of the island as well as its resilience to storm forces.

St. Croix has diverse terrestrial habitats as well; these habitats include forests and shrublands. 72% of the island is categorized as subtropical dry habitat, with the remaining being categorized as subtropical moist forest.48 Variations in rainfall across the island create a variety of ecosystems. Most protected natural spaces on St. Croix include one of the above natural systems - highlighting the need to appreciate and steward these systems well. These spaces are not only protected for their beauty but, also, for their ecological services.

The existing conditions of some of St. Croix’s natural systems display how interconnected human systems are with natural systems. One native species, Sargassum—a type of floating seaweed, has led to several challenges for St. Croix’s infrastructure ultimately resulting in a declared emergency. Sargassum is naturally occurring; however, it is currently overabundant and creates thick mats. These thick mats clog the guts and the Seven Seas Desalination Plant intake pipes. Clogged guts can lead to slow drainage of water on land and clogged Plant intake pipes make it nearly impossible to treat and deliver potable water. The Sargassum influx may be linked to pollution that originates outside of the Caribbean.49

The threat of pollution is significant given the island’s industrial history, which has impacted air, soil, and water quality. Pollution is a major threat to coral reefs and aquatic ecosystems because these systems rely on delicate water chemistry to survive. Similarly, mangroves and other important terrestrial and shoreline systems are threatened by development, which can either decrease the functionality of or completely remove habitats altogether.

Three major events defined the last decade for St. Croix. The events include the closing of the refinery between 2012-2019, the 2017 hurricanes, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Over the last decade, these three major events have changed aspects of the makeup and function of the island. Not only was the refinery a major economic engine on the island, but it also supplied residents with stable, middleincome employment. Since its primary closure in 2012 and shut down of reinstallation efforts in 2019, there has yet to be an operation to fill its gap.

In 2017, Hurricane Maria ravaged St. Croix, a natural disaster the island is still rebuilding from. Lastly, the COVID-19 pandemic has helped St. Croix turn into a tourist destination, but it is important to note this might be at the expense of residents’ health. These three recent events will forever be part of St. Croix’s history and shape how the island operates in the future.

HurricaneMaria(2017)

Hurricanes

Hurricanes (1922-2022)

Important Storms

Data: NOAA

Hurricane Hugo served as a turning point on the island as disaster management methods and planning greatly increased after Hugo.

In 1989, Hurricane Hugo left a devastating path of destruction on the island, causing severe human and ecological loss.50 This served as a turning point on the island as disaster management methods and planning greatly increased after Hugo. However, these remedies would prove only a small step in the right direction as decades later in 2017, St. Croix was severely hit by a category 5 Hurricane Maria. Maria came right on the heels

of another category 5 hurricane, Irma, where the neighboring Virgin Islands were devastated as well. Five years later, St. Croix is still recovering from the physical impacts of Maria. For example, homes still have blue tarps covering roofs and composite telephone poles are still being installed. That said, St. Croix fared rather well in managing the population’s safety with few fatalities; this is due to preparations after Hugo.

Another major event that has impacted the island is the COVID-19 pandemic. Surprising to some, St. Croix emerged as a newfound tourism hot spot as many Americans could not travel outside of borders. Tourism increased significantly between 2019 (640,887 visitors) and 2021 (738,040 visitors).51 While this is beneficial from an economic development perspective, it has not been as generous for the health of islanders. Hurricane Maria left the

only hospital on St. Croix in disrepair, additionally a history of mistrust made it difficult to persuade the public to opt into taking the vaccine. Thus, the vaccination rate for the island is relatively low (55% compared to 81% in Puerto Rico), meaning that with every tourist, there is higher risk for residents to get sick and a limited number of resources to treat them.52

Hurricanes Irma and Maria decimated the hospitals on St. Croix and St. Thomas in 2017, requiring them to be torn down and rebuilt, which left them weak and exposed to the COVID-19 pandemic.

$140 million in annual tax revenue lost

The final major event was the volatile closing of the HOVENSA / Limetree Bay Refinery in 2012 and again in 2021. Prior to its closure, the refinery was the largest employer on the island. The refinery closed due to EPA violations and a tragic acid rain incident that polluted the island’s aquifers.53 While the closure of the refinery may be beneficial to the environment, it slashed USVI exports by 50%, lost 2K jobs, and $140M in annual tax revenue. The island is still recovering from the economic loss of the refinery.

~ 2,000 jobs lost 50% of USVI exports

From this report’s analysis, we have identified these major events as contributing factors in St. Croix’s population loss. From 2010, St. Croix has lost 19% of its population base — mirroring the population decline the entire USVI is seeing.54 While these three events cannot be the sole causes for the observed population loss, they did have a significant impact on the population.

Data: 2000, 2010, & 2020 Decennial Census of Island Areas and 2005 & 2015 Virgin Islands Community Survey, Eastern Caribbean Center

Climate change compounds the previously mentioned challenges St. Croix faces. Whether the island is contending with a future of flooding or drought or both, the way of life on St. Croix must adapt to future climate threats. As discussed further below, climate change impacts both all natural and man-made systems on the island. The current reality of St. Croix is that infrastructure is flooded all too easily, crops and agriculture struggle from increased temperatures and lack of irrigation, and all of this impacts the well-being of people.

Unfortunately, the young, the elderly, and especially the socioeconomically vulnerable individuals, will face the brute of the impacts of these future threats. Planning for resilience strengthens and empowers all citizens of St. Croix to prepare for, adapt to, and recover from climate-related threats.

In looking at climate projections, St. Croix is facing two dire situations. In the climate average scenario of Global Climate Models (GCMs), St. Croix is expected to become much drier—a worry for the island’s water supply. And, in the climate extreme scenario, St. Croix is expected to become slightly wetter—meaning increased flooding and rising coasts.56

More modeling suggests that it is heavily indicated that St. Croix will become warmer by roughly 2 degrees Fahrenheit by the 2050s and 3.3 degrees Fahrenheit by the 2100s.57 Night temperatures are expected to

increase, as well.58 The temperature changes will cause a multitude of emerging issues. For example, the large elderly population of St. Croix at a higher risk of heat-related illness and vector-borne diseases and agriculture on the island will be negatively impacted, as well. It is important to remember that increase in temperature is not a localized phenomenon. Several regions across the globe are increasing in temperature leading to the melting of land ice and expansion of the ocean; this melting and expansion cause sea level to rise.

Sea Level Rise by 2090 Roads Arterials Arterials Impacted

Airport/Sea Plane Base Ferry Terminal/ Cargo Port

By 2050, sea level rise will capture 3.7% of the island and 40 years later, that figure will increase to 8.2%.

Sea level rise would impact the vibrant Christiansted boardwalk and several historic buildings in Frederiksted. Sea level rise will critically impact infrastructure on St. Croix, as 23% of the arterials and many beaches will be underwater—a major economic assets to the island.

Without beaches, the tourism industry of St. Croix will decline. Beaches on the island are also facing other problems, like storm surge, which can cause dramatic flooding and erosion on the beaches.

Storm surge will also exacerbate natural and infrastructural flooding. As storm surge is a result of storm events, such as hurricanes and hurricanes are expected to increase in intensity, so will storm surge.

While St. Croix has a gut system that tries to alleviate flooding, guts do not completely solve the problem and the potential flooding and run-

off threatens millions of dollars in infrastructure, including homes. 32% of the island is within a flood zone and 3,656 are endangered. While “storms [are generally] considered part of living on barrier islands”, flooding of infrastructure should not be.59

Flooding Impact

Flood Zone Roads

Arterials Impacted

Bus Routes Impacted

Airport/Sea Plane Base

Ferry Terminal/ Cargo Port

32% of the island is within a flood zone, including 3,656 buildings that are at risk of flooding.Christiansted Frederiksted

$1.17 Billion

Data: Government of the US Virgin Islands Open Finance

Although an abundance of disaster recovery funding is available to St. Croix, the local government struggles to access these funds.

the middle of the United States Virgin Islands, the middle of the Caribbean, and not too far from Florida. However, when storm events, such as hurricanes, occur ports are often closed. Since most goods and services are imported to St. Croix, this heightens the reality of isolation and the challenges of living on an island; again, proclaiming the importance of planning for the resilience of St. Croix.

St. Croix is an isolated island, but it is not alone. The geographical context of St. Croix is such that it is situated in

1. “Columbus Landing 1493 St Croix,” November 11, 2021. https://mystcroix.vi/columbuslanding-1493-st-croix/.

2. “St. Croix: Facts & History,” n.d. https://www.vinow.com/stcroix/history/.

3. “St. Croix History,” n.d. https://www.soulofamerica.com/international/st-croix/st-croixhistory/.

4. Ibid.

5. “St. Croix: Facts & History,” n.d. https://www.vinow.com/stcroix/history/.

6. “The Slave Rebellion on St. Croix and Emancipation,” n.d. https://www.virgin-islandshistory.org/en/timeline/the-slave-rebellion-on-st-croix-and-emancipation/.

7. Angela Golden Bryan. Fireburn the Documentary, 2021. https://www.newday.com/films/ fireburn-the-documentary.

8. “St. Croix: Facts & History,” n.d. https://www.vinow.com/stcroix/history/.

9. “United States Virgin Islands: Government and Society.” In Britannica, n.d. https://www. britannica.com/place/United-States-Virgin-Islands/Government-and-society.

10. Ibid.

11. “History of the V. I. Judiciary,” n.d. https://www.vicourts.org/about_us/overview_of_ judiciary_of_the_virgin_islands/history_of_the_v__i__judiciary.

12. “United States Virgin Islands: Government and Society.” In Britannica, n.d. https://www. britannica.com/place/United-States-Virgin-Islands/Government-and-society.

13. “St. Croix History,” n.d. https://www.soulofamerica.com/international/st-croix/st-croixhistory/.

14. “St. Croix: Facts & History,” n.d. https://www.vinow.com/stcroix/history/.

15. “Refinery on St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands.” United States Environmental Protection Agency, n.d. https://www.epa.gov/vi/refinery-st-croix-us-virgin-islands.

16. “St. Croix History,” n.d. https://www.soulofamerica.com/international/st-croix/st-croixhistory/.

17. “St. Croix: Facts & History,” n.d. https://www.vinow.com/stcroix/history/.

18. “CDC/ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index.” November 16, 2022. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/ placeandhealth/svi/index.html.

19. J. Dwyer, G. Guannel, H. Lohmann. “U.S. Virgin Islands SVI Map.” 2002. ArcGIS Online. https://arcg.is/181TD5.

20. “2010 Island Areas - U.S. Virgin Islands Dataset.” United States Census Bureau, n.d.

21. Ibid.

22. Ibid

23. Ibid.

24. Ibid.

25. “2020 Island Areas - U.S. Virgin Islands Dataset.” United States Census Bureau, n.d.

26. Bill Kossler. “STX Trash Haulers Unpaid Again, Stop Hauling Again,” July 6, 2022. https:// stthomassource.com/content/2022/07/06/stx-trash-haulers-unpaid-again-stop-hauling-

again/.

27. “2010 Island Areas - U.S. Virgin Islands Dataset.” United States Census Bureau, n.d.

28. Suzanne Carlson. “EPA Investigating Limetree Bay Refinery’s Contamination of Cisterns on St. Croix,” March 5, 2021. http://www.virginislandsdailynews.com/news/epa-investigatinglimetree-bay-refinerys-contamination-of-cisterns-on-st-croix/article_53ac355d-bd2e-59df8c1c-da1fe697ba23.html.

29. “US Virgin Islands: Territory Profile and Energy Estimates Profile Analysis.” U.S. Energy Information Administration, January 20, 2022. https://www.eia.gov/state/analysis. php?sid=VQ#:~:text=The%20USVI%20has%20significant%20solar,scale%20solar%20 power%20generating%20capacity.&text=The%20USVI’s%20first%20large%20solar,at%20 King%20Airport%20on%20St.

30. Ibid.

31. “2010 Island Areas - U.S. Virgin Islands Dataset.” United States Census Bureau, n.d.

32. Ibid.

33. Ibid.

34. Ibid.

35. “Virgin Islands Next Generation Network,” n.d. https://vingn.com/.

36. Bowden, Jared H., Adam J. Terando, Vasu Misra, Adrienne Wootten, Amit Bhardwaj, Ryan Boyles, William Gould, Jaime A. Collazo, and Tanya L. Spero. “High‐resolution Dynamically Downscaled Rainfall and Temperature Projections for Ecological Life Zones within Puerto Rico and for the U.S. Virgin Islands.” International Journal of Climatology 41, no. 2 (February 2021): 1305–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.6810.

37. Donald G. Jordan. “A Survey of the Water Resources of St. Croix Virgin Islands.” National Park Service, 1975. https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/1973/0137/report.pdf.

38. The University of the Virgin Islands. “Climate Change Adaption Planning Assessment and Implementation: Final Vulnerability and Risk Assessment Report,” 2019. https://www.doi. gov/sites/doi.gov/files/1.-usvi-climate-vulnerability-and-risk-assessment-report-final.pdf.

39. “Web Soil Survey - Areas of Interest.” United States Department of Agriculture, n.d. https:// websoilsurvey.sc.egov.usda.gov/App/WebSoilSurvey.aspx.

40. “St. Croix’s Locavore Revolution,” 2013. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/ article/st-croixs-locavore-revolution.

41. “Saint Croix Topographic Map.” US Topographic, n.d. https://en-us.topographic-map.com/ map-qjqtj/Saint-Croix/?center=17.60814%2C-64.7437&zoom=14&popup=17.61695% 2C-64.77496.

42. G. E. Hendrickson. “Ground Water for Public Supply in St. Croix Virgin Islands,” 1963. https://pubs.usgs.gov/wsp/1663d/report.pdf.

43. Ibid.

44. National Park Service. “Salt River Bay: Natural Features and Ecosystems,” n.d. https://www. nps.gov/sari/learn/nature/natural-features-and-ecosystems.htm.

45. Tristan Alan Pierre Allerton and Skip J. Van Bloem. “Forest Health Conditions of St. Thomas and St. Croix, US Virgin Islands.” Baruch Institute of Coastal Ecology and Forest Science, n.d. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343489268_Forest_Health_of_St_ Thomas_and_St_Croix.

46. Ibid.

47. Ibid.

48. National Park Service. “Salt River Bay: Natural Features and Ecosystems,” n.d. https://www. nps.gov/sari/learn/nature/natural-features-and-ecosystems.htm.

49. “Sargassum White Paper: Turning the Crisis into an Opportunity.” UN Environment Programme, 2021. https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/36244/ SGWP21.pdf?sequence%E2%80%A6.

50. William Branigin. “Hurricane Hugo Haunts Virgin Islands.” Washington Post Foreign Service, October 31, 1989. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/longterm/ hurricane/archives/hugo89a.htm.

51. “USVIBER.” U.S. Virgin Islands Bureau of Economic Research, n.d. https://usviber.org/.

52. Susan Ellis. “Just 55 Percent of USVI Vaccinated as COVID-19 Infections Continue,” May 26, 2022. https://stthomassource.com/content/2022/05/26/less-than-half-usvivaccinated-as-covid-19-infections-continue/.

53. Juliet Eilperin. “St. Croix Refinery Halts Operations after Raining Oil on Local Residents Once Again.” Washington Post, May 13, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/climateenvironment/2021/05/12/limetree-bay-refinery/.

54. “USVI Population Drops a Stunning 18.1 Percent to 87,146 From 106,405.” The Virgin Islands Consortium, October 28, 2021. https://viconsortium.com/vi-top_stories/virginislands-usvi-population-drops-a-stunning-18-1-percent-to-87146-from-106405.

55. “Predictions of Future Global Climate.” Center for Science Education, n.d. https://scied. ucar.edu/learning-zone/climate-change-impacts/predictions-future-global-climate.

56. Ibid.

57. Ibid.

58. “What Climate Change Means for the U.S. Virgin Islands.” U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2016. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-11/documents/climatechange-usvi.pdf.

59. Gaul, Gilbert M. The Geography of Risk: Epic Storms, Rising Seas, and the Costs of America’s Coasts. First edition. New York: Sarah Crichton Books/Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019.

Based on the research conducted in the first half of the studio and the on-island travel experience, our studio team developed a shared definition of resilience to apply specifically to our work in St. Croix. We looked at stakeholders, strategies, actions, and other elements that contribute to resilience and brought them together to uncover commonalities and priorities. The definition was driven as much by research as it was by lived experiences in St. Croix, as travel week had a significant impact on the framing of previous research and allowed the team to approach this resilience definition with a new perspective.

This resilience definition serves as a guiding vision for the studio and has been used to steer the resilience projects pitched in the second half of this plan. Each project speaks to this definition by proposing ways in which existing systems on St. Croix can anticipate changes that may come in the future and prepare for them now. This definition unifies the projects with the goal of helping St. Croix maximize its resilience and promote the well being of all people on the island.

St. Croix’s strength lies within its resilience. It is the ability to adapt to and recover from environmental, social, and economic shocks in order to ensure the prosperity of the island and its people.

Reimagining Ecotourism was conceptualized from our personal experiences while visiting St. Croix. Seeing the abundance of cultural and environmental assets that the island offers and realizing that tourism is concentrated much more heavily in St. Thomas inspired this project, which aims to make St. Croix more competitive as a tourism destination. This project is inspired by and builds upon the incredibly valuable existing work of so many cultural organizations – CHANT, VITAL, VIEDA, The Nature Conservancy, St. Croix Environmental Association, and the St. Croix Foundation to name a few.

We aim to reframe how tourism is viewed in St. Croix, appreciating the island’s resilience and culture while envisioning St. Croix as a median between St. Thomas and St. John, valuable for both its environmental and cultural assets. Overall, this project is about celebrating St. Croix’s people, building upon the existing work of Crucians and reimagining ecotourism in a way that puts islanders first.

Some of the most major impacts on the tourism industry are those discussed previously. The COVID-19 pandemic has drastically altered the way that tourists visit the USVI. Mainland Americans can travel more easily without passports; however, incoming tourists pose greater risks to the health and safety of islanders. Without sufficient hospital infrastructure, tourism in the age of COVID-19 significantly affects St. Croix’s economy and existing population. The 2017 hurricanes and other natural disasters caused destruction to both infrastructure and the environment, and the island is still recovering from the effects of major weather events. With the refinery’s closure causing the loss of the island’s main job industry, tourism grew to be a primary economic driver.

It is most important that Reimagining Ecotourism acknowledges the ways that St. Croix has been resilient, appreciating both Crucian culture and environment. Ecotourism creates the perfect opportunity to rebuild the tourism industry in a way that benefits different people.

To understand how ecotourism can benefit St. Croix, it is important to define it and distinguish it from traditional tourism.

The UN World Tourism Organization defines sustainable tourism development as “tourism that takes full account of its current and future economic, social and environmental impacts, addressing the needs of visitors, the industry, the environment and host communities.”1

A more general definition for ecotourism: “tourism directed toward exotic, often threatened, natural environments, intended to support conservation efforts and observe wildlife.”2

Reimagining Ecotourism merges these ideas and applies them specifically to St. Croix. To do that, we have defined ecotourism in a St. Croix-specific context to address the ways that we envision ecotourism benefiting the island’s people.

• Acknowledge island history and Crucian resilience

• Preserve natural assets

• Link tourists and Crucians to the environment

• Contribute to the local economy

• Redistribute wealth to native islanders

• Return agency to islanders, protecting the people and the natural environment

in St. Croix should be

A sustainable tourism industry that seeks to preserve people, culture, and environment

To help illustrate the possibilities of ecotourism and frame this project, we have analyzed two case studies.

Belize has successfully implemented a sustainable tourism industry while minimizing its impact on nature. With more than 70% of the country being forested, there are 103 protected areas, many of which serve as animal sanctuaries.3 Additionally, the country’s barrier reef is no longer endangered, and offshore oil exploration and drilling is banned.4 One of the main draw-in points for ecotourism in Belize is volunteering and conservation groups in the rainforests, a unique opportunity to appreciate the country’s landscapes.5 With such forward-thinking approaches to environmentalism and great opportunities for tourism, Belize’s impressive tourism industry draws in many visitors to Central America.

The Republic of Palau is renowned for its innovative approach to environmental conservation and sustainable tourism. When tourists arrive on the islands, they must sign the Palau Pledge, requiring them to act in an ecologically and culturally responsible manner.6 With over 740,000 pledges taken, tourism, the country’s most significant economic driver, benefits both the visitors and native islanders.7 Additionally, Ol’au Palau, a travel rewards program via a smartphone application, provides visitors exclusive access to island activities by interacting with sustainable initiatives, accredited local businesses, and customs.8

With such creative and effective approaches to supporting the tourism industries, both Belize and Palau inspired new ways to envision how Reimagining Ecotourism can flourish in St. Croix.

In 2019, more than 2 million people visited the United States Virgin Islands, bringing in more than $1 billion in expenditures.9 That year, cruise passengers and day-visit excursionists made up 75% of visitation but only 33% of expenditures.10 On the other hand, the remaining 25% of visitors were longer-stay tourists who brought in the majority of expenditures.11 This demonstrates the significant impact that longer stay tourists can have on the island’s economy, and as such more resources should be geared towards developing these longer stays.

However, cruise ship passengers and day excursionists make up the majority of visitors to both the USVI12 and BVI.13 This day-visit-focused travel industry model contradicts the function of normal tourism, and the USVI, especially St. Croix, which could greatly benefit from the longer-term travel industry growth.

It is abundantly apparent that tourism is an established industry in St. Croix and the USVI; this project merely aims to strengthen it in favor of both native islanders and the environment, ideally attracting more longer-stay visitors that spend more money at local businesses, thus having a greater economic impact.

2017 - 2022

According to USVI Bureau of Economic Research data, longer-stay/air travel to St. Croix after the onset of COVID-19 in 2020 has recovered decently well to pre-COVID levels.14 This is likely because travel in the age of COVID-19 is easier for mainland Americans, as they do not need passports to visit the USVI. However, there are still significantly fewer travelers to St. Croix in comparison to St. Thomas.15 In 2019, only 25% of all air passengers arriving at the USVI came to STX.16 The industry may have recovered closer to pre-COVID levels, but the island still falls short as a tourist destination.

2017 - 2022

On the other hand, the cruise industry has not recovered to pre-COVID levels.17 Only a tiny fraction of cruise

ships come to St. Croix; in 2019, not even 4% of cruise ships arriving in the USVI came to St. Croix.18 Given that cruise passengers make up most visitors and that St. Croix receives very little benefit from the cruise industry (by comparison to St. Thomas), the travel industry needs revitalization.19 At this rate, the cruise industry is not likely to recover from COVID soon. However, the cruise and day visit market is not serving our goal of improving economic investment and experiencing the full potential of St. Croix’s environmental assets. By shifting the travel industry to focus on longer-term stays, the tourism industry can have a much stronger economic impact on St. Croix.

Analyzing the accommodations industry, St. Croix falls short compared to St. Thomas. In 2021, the average hotel occupancy rate in St. Thomas was 66%, while it was only 55% in St. Croix.20 In their respective high seasons, St. Thomas occupancy rates reached up to 88% in March, and St. Croix reached 80% in May.21 During the low seasons, however, St. Thomas dropped down to 41% in July, and St. Croix dropped to 34% in October.22 For reference, an ideal occupancy rate is between 70% and 95%. That same year, St. Thomas had about 775,000 Room Nights Available, which is the number of nights that accommodation units are available for occupancy in a given period, while St. Croix had not even 300,000 Room Nights Available.23 This data shows that visitor capacity is lower in St. Croix. Even with decent occupancy rates in the high season, tourism is still much slower than that in St. Thomas. To address this discrepancy, we do not want to build more hotel rooms in St. Croix. It is clear that the accommodation infrastructure is already there; we just want to encourage more people to make longer-term stays, to replace the people making day visits from cruise ships. More longer-stay visitors filling out these rooms has the potential to bring St. Croix much more revenue, ideally in ways that can directly benefit Crucians.

In sum, this data shows us that the discrepancy between island visitation and the unrecovered cruise industry creates the perfect opportunity to target the longer-stay tourism industry in St. Croix. Tourism is already an established economic driver for the USVI. However, with a much

larger port and more tourist-centric programming, the industry is much stronger in St. Thomas. By promoting and effectively rebranding St. Croix for experiential ecotourism, the travel industry can reach a broader market, encouraging greater spending and longer stays.

Reimagining Ecotourism aims to diversify the economy, making St. Croix more competitive with other Caribbean islands.East End, St. Croix (Image: UPenn Studio)

To appropriately address the findings of this data and find ways to encourage the evolution of the travel industry in a way that prioritizes the island’s people and environment, we have outlined a list of policy and practice recommendations. These recommendations address

specific environmental issues and ways of preserving island assets, not just for the benefit of incoming tourists, but also to give Crucians a cleaner, healthier place to live. By recommending policies that preserve environmental assets, we can create actionable steps to ensure that the island is safe for all, protecting it for future generations..

The first recommendation for targeting and improving St. Croix’s travel industry is a waste management plan. Reducing litter and maintaining clean, livable land is key to environmental preservation. By managing waste and disposal, St. Croix can better preserve its beautiful vernacular landscape. To do this, we recommend that the island continues phasing out plastic, effectively protecting both marine and land environments while reducing carbon footprints. In the spirit of the 2022 law banning single-use, nonrecyclable plastic bags, continuing to phase out plastic would greatly improve the island’s waste issue. Additionally, St. Croix can greatly benefit from litter and landfill control. By creating more accessible waste disposal sites, we could mitigate illegal dumping in guts and undesignated locations. Currently, the island’s two dump sites have inconsistent hours and increasing tipping fees and stable waste disposal sites would provide great benefit to the island. However, this cannot be done without providing the VI Waste Management Authority with more consistent support and funding. By ensuring stable funding, the industry can reduce worker strikes and service unreliability.

The second recommendation, an open space and environmental protection plan, is aimed at proactively protecting St. Croix’s open space so that the island can be viewed as a destination that tourists want to visit for both its beauty and forwardthinking approaches to environmental preservation. This plan should continue banning environmentally hazardous materials, like the existing law prohibiting sunscreens with ingredients that are harmful to the coral reef. It should also have stricter development guidelines and limitations in locations where the environment needs to be preserved –specifically the coral reef, rainforest, mangroves, guts, and beaches. These assets are hubs of biodiversity, and the protection of island species is highly dependent on the preservation of these landscapes. One of the most effective ways that St. Croix can protect these landscapes is by regulating land use and preserving existing open spaces.

The third recommendation, a sargassum management plan, seeks to preserve beaches, one of the main assets drawing visitors to the Caribbean. With sea level rise and growing influxes of sargassum, St. Croix could benefit from seasonal policies to manage the seaweed. The plan should publicize health and safety measures for making contact with decomposing seaweed, ensure water filtration services are clean and sufficient, organize sargassum removal before it can settle on beaches, and proactively protect beaches to avoid the need to declare national emergencies. Sargassum is only projected to increase, and St. Croix must be prepared to handle it safely.

The last recommendation, and potentially the most important, is defining ecotourism and marketing why it is valuable to both visitors and island residents. Awareness is key to showing the possibilities of ecotourism and helping the industry grow safely and mindfully. By marketing the island’s assets to a broader audience, focused on longer-term stays, St. Croix can build a travel economy that is not solely dependent on the cruise industry. This can take form online through:

• An increased social media presence that markets the assets of the island.

• Travel applications that incentivize activities connected to cultural sites.

• Interactive travel experiences that provide new ways of linking people to island assets and resources. We want to push ecotourism as a new medium for economic investment in St. Croix, and increased methods of interacting with the island can be a great first step for growing the travel industry.

Awareness is key to helping the industry grow safely and mindfully.

To illustrate the possibilities of ecotourism in St. Croix, this project features experiential tour routes, each highlighting historical and cultural sites, natural preserves, festivals, and special events that can draw visitors to the island. These Eco-tours highlight the potential for interactive elements like smartphone applications and story maps that can bring visitors closer to the island’s people and culture. When choosing sites and locations of interest for these tours, we had very specific goals:

• Connecting assets around the entire island, not concentrating solely around the cities

• Locating ecological interests with the potential for greater engagement

• Engaging tourists in the landscape while preserving it

• Giving islanders autonomy over the narrative and image taught to tourists

• Creating employment and entrepreneurial opportunities for islanders

Envisioning ways that tourism can flourish while putting islanders first, this project aims to reshape the industry to accommodate more longerstay visitors in the post-COVID age. These Eco-tours inspire potential jobs surrounding guided tours, ecological maintenance, activity businesses, and restaurant growth. They demonstrate the ways that we envision St. Croix linking tourists, Crucians, and the environment. We hope that these tours can inspire more ways of bringing visitors closer to St. Croix’s culture while building opportunities for Crucians to benefit from this industry.

Historical

Natural Preserve

Cultural/Special Event

Interactive

1. Salt River Bay National Historical Park and Ecological Preserve

• Christopher Columbus Landing Site

• Kayak Tour

• Serenity’s Nest Concert Hall

2. Windsor Farm Trails / Scenic Road Trail Tour

3. Rustoptwist Sugar Mill / Scenic West Sugar Mill / Hams Bluff Sugar Mill / Estate Mount Washington Ruins

4. Annaly Bay / Carambola Tide Pools / Cane Bay Beach

• Educational, entrepreneurial, and employment opportunities: rainforest preservation, hazard protection, trail maintenance, sargassum management, bioluminescence

• Activity opportunities: live music, performances, marathons, bike races, kayaking, partnership with non-profit environmental organizations

• Interactive smartphone application topics: colonial history, traditional Crucian music, stargazing, biking trail map

1. Fort Christiansvaern / Danish West India and Guinea Company Warehouse / Steeple Building / The Scale House

2. Marine Nature Reserve Tour

• Buck Island

3. Boardwalk Tour

Fort Christiansvaern Image: StCroixTourism.com

• Educational, entrepreneurial, and employment opportunities: emergency management, coastline and natural disaster threats

• Activity opportunities: shopping, dining, live music and performances, boat tours, scuba diving, snorkeling, fishing charters and tours, water sports, parasailing, paragliding, surfing, windsurfing, kitesurfing, kayaking, canoeing, boat rental, partnership with the St. Croix Foundation

• Interactive smartphone application topics: Crucian culture, colonial history, marine life and habitats, animal and plant identification, walking tour guide

Historical

Natural Preserve

Cultural/Special Event

Interactive

Sandy Point Frederiksted• Historic District

• Fort Frederik

• Caribbean Museum Center for The Arts

• Athalie Petersen Public Library

• Walking tour with CHANT

• Educational, entrepreneurial, and employment opportunities: sea turtle protection, sargassum management

• Activity opportunities: shopping, dining, wildlife observation, wildlife art contests

• Interactive smartphone application topics: Crucian culture, colonial history, marine life and habitats, animal and plant identification, walking tour guide, shopping guide for traditional Crucian handcraft

Point Udall (Image: Gotostcroix.com)

Historical

Natural Preserve

Cultural/Special Event

Interactive

Hiking Goat Hill Image: Uncommon Caribbean

• Educational, entrepreneurial, and employment opportunities: trail maintenance, natural and marine environment preservation

• Activity opportunities: marathon, bike race, Whale Point Trail, Fairleigh Dickinson Territorial Park

• Interactive smartphone application topics: stargazing, walking tour guide, biking trail map

Reimagining Ecotourism seeks to highlight the untapped potential of the tourism industry in St. Croix. Tourism is already an established economic driver; however, rebranding tourism as ecotourism and finding new ways of caring for the environment can be a more effective method of increasing longer-stay visitors while caring for Crucians. We hope that this begins to inspire a new framework for ways of viewing the tourism industry and give way to ecotourism linking tourists to Crucians and the landscape in a mindful way.

1. “Sustainable Development.” UN World Tourism Organization. https://www.unwto. org/sustainable-development#:~:text=Sustainability%20principles%20refer%20to%20 the,guarantee%20its%20long%2Dterm%20sustainability.

2. “Ecotourism: Argument/Persuasion.” Argument/Persuasion - Ecotourism. LibGuides at St. Petersburg College. https://spcollege.libguides.com/ecotourism#:~:text=Ecotourism%20 is%20tourism%20directed%20toward,conservation%20efforts%20and%20observe%20 wildlife.

3. O’Connell, Jeff. “Why Belize Is the Ultimate Ecotourism Destination.” Travel Belize, May 15, 2021. https://www.travelbelize.org/why-belize-ultimate-ecotourism-destination/.

4. Ibid.

5. Tzul, Sayuri. “Ecotourism Belize.” November 9, 2022. https://www.ecotourismbelize.com/.

6. Lin, Dan. “Palau Becomes First Country to Require ‘Eco-Pledge’ Upon Arrival.” Travel. National Geographic, May 3, 2021. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/ passport-stamp-ecotourism-pledge.

7. Palau Pledge. https://palaupledge.com/.

8. Ol’au Palau. https://olaupalau.com/.

9. “U.S. Virgin Islands Annual Tourism Indicators.” Charlotte Amalie: USVI Bureau of Economic Research, 2022.

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid.

13. “Tourist Arrivals by Category 2019 (January - December).” Statistics. Government of the Virgin Islands.

14. “U.S. Virgin Islands Annual Tourism Indicators.” Charlotte Amalie: USVI Bureau of Economic Research, 2022.

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid.

18. Ibid.

19. Ibid.

20. “H21-DEC-REVISED-1.” Charlotte Amalie: USVI Bureau of Economic Research, 2022.

21. Ibid.

22. Ibid.

23. “RA-21-DEC-1.” Charlotte Amalie: USVI Bureau of Economic Research, 2022.

The rapid succession of hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017 were devastating for the USVI. Collectively, the storms caused widespread power outages, flooding, storm surge, and infrastructure damage. The damages were profound and long lasting— estimated at over $10.76 billion in total, including sustained damages to 52% of the housing stock, 12% of which was severely damaged.60 The storms also hit during a time of significant budgetary strain for the territory with a total of $5.4 billion in public debt and unfunded obligations. These conditions coupled with the territory’s isolated geography, positioned it for a challenging recovery.

Like the storms, the recovery response has been substantial, with USVI anticipating as of October 2022 a total of $10 billion in federal recovery funding over the next 5–8 years. While the recovery response has been considerable, it has struggled with implementation challenges and delays, requiring the extension of some programs’ time horizons and, recently, the announcement of an audit by HUD on the administration of CDBG –Disaster Recovery funds.

This report explores the governmental entities, programs, and data being used to support USVI’s recovery from the 2017 hurricanes. As a highly complicated bureaucratic process, this work is intended to bring clarity to the funding process and shed some light on the dynamics impacting the current state of recovery funding in USVI.

We focused our approach around three central questions:

• Who are the primary federal funders and programs active in USVI?

• What does the delivery of these programs look like?

• What’s the current state of funding in 2022?

With these questions as our research basis, we have structured the following report with a summary of our research process followed by our main observations from our exploration of the federal recovery funding landscape and concluding with four central themes and a related recommendation for future work supporting the efficacy and equity in the allocation and expenditure of federal recovery dollars.

amount of money available to a federal agency for a specific purpose

once funding has been allocated for a given purpose, an agency can incur an obligation—a legally binding commitment

In framing our approach to this subject, we wanted to acknowledge the plethora of existing research on recovery and funding in USVI as well as recovery plans already made for the territory. Namely, the St. Croix Community Recovery Plan (2018), and Recovery in the U.S. Virgin Islands, otherwise known as the RAND Report (2019), were essential guides for our work and revealing foils to one and another (which we explore in more detail later). In addition to existing territory-level recovery and planning reports, we started our research by looking at major repositories of funding and government spending data. These two resources including USAspending.gov, which is a database of all transactions since 2008 by the US government, and the Office of Disaster Recovery (ODR), which was established in 2019 by the Territory to streamline the recovery funding

when a federal agency liquidates an obligation

process as the central coordinating and tracking entity of all recovery dollars coming into USVI.

We also analyzed some recovery programs active in the USVI. These included the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Community Development Block Grants Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) program and the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) Program Assistance (PA) recovery program. Given the recent HUD audit announcement and that it is one of the least expended funding sources thus far in recovery (22.4% expended), we particularly centered the CDBG-DR program for much of our programmatic analysis using it as example of potential challenges slowing or impeding the expenditure of recovery funds.

Since 2008, USVI has been allocated almost $19 billion dollars, or $187,000 per resident, in federal funding. Of that total, 70 percent of the funds, or $13 billion, $132,000 per resident, has been allocated since the 2017 hurricanes. To provide some reference, the entire USVI annual 2022 budget is around $1.1 billion, or $11,000 per resident. While the relative size of these funding amounts is staggering in and of itself, the bulk of the allocation

(70%) occurred following the storms which accounts for just 36%, or 5 of the 14 years, over the entire available data period. Given the size of USVI, this is tremendous amount of capital to handle in an extremely compressed time frame. The volume and timescale of these funds also underscores the profound potential effect they might have on the USVI’s economy and various on-island industries.

187K 132K 11K $$$ $$ $

Source: USA Spending

$18.7B amount of money allocated to USVI since 2008

$13.2B amount of money allocated to USVI since 2017

$1.1B average annual USVI budget

Source: Office of Disaster Recovery

In an effort to increase the efficacy of managing these funds, the USVI established the Office of Disaster Recovery (ODR) in 2019 to support the tracking and monitoring of federal dollars entering USVI. Using ODR’s available allocated, obligated, and expended data, we calculated the current burn (use) rate of federal recovery dollars, finding that USVI is currently projected to expend the entire $10 billion by June of 2034 with

only 30% of funds spent as of 2022 ($2.9 billion). As most of the federal recovery dollars have set expenditure deadlines typically ranging between five to seven years, at the current rate, USVI will not be able to meet these time horizons, leaving funds on the table and need unmet. While extensions are possible, the USVI faces a significant challenge in turning around its current low burn rates.

In 2019, ODR projected 80% of funds to be spent by the end of 2022, but only 30% ($2.9B) has been spent.

June 2034

projected to expend $10B

Source: Office of Disaster Recovery

Using USA Spending data, we tracked the overall share of federal funding allocations by USVI island: St. Thomas, St. Croix, and St. John (Water Island not indicated in data set). We found that while St. Croix and St. Thomas were relatively on par with Islandspecific federal spending prior to 2017, they experienced radical shifts in funding following the 2017 storms. Despite both islands receiving similar degrees of damage, St. Thomas is getting the lion’s share of funding, with St. Croix receiving just 13 percent of the entire funding pool.

While this divergence is likely due to a multitude of reasons, it is important to note that St. Thomas is the center of tourism for the territory with as many as six ships docked in a single day in its port Charlotte Amalie pre-pandemic. While St. Croix has a larger population and is the largest island in the territory it is very much a secondary island in terms of tourism and economic generation, and it would appear is being allocated funds in accordance with this observation.

St. Croix received

13%

of funds since 2017

Source: USA Spending

For our second finding, we evaluated some of the programs used to distribute the allocated funds to the island, namely at HUD’s Community Development Block Grants –Distracter Recovery (CDBG-DR). Transferred from HUD to the USVI’s Housing Finance Authority (HFA) for distribution, the CDBG-DR funds are broadly directed in four ways: for housing, infrastructure, economic revitalization & recovery, and public services.

The funds are used for a multitude of recovery efforts, one such notable use being the “Local match for FEMA,” which accounts for almost half of all total funds during just the first and second tranches alone. Most FEMA funding available to USVI is delivered on a reimbursement basis, which the USVI has addressed partially by diverting CBDG infrastructure funding to foot the upfront FEMArelated costs. Accounting for a huge

to

share of the total infrastructure allocation, these dollars could be used towards infrastructure separate from FEMA projects, if the reimbursement requirements changed.

Another potential challenge facing the system is the allocation of all CBDG funds to the Housing Finance Authority, even though the majority of the funds are not used for housing. Having the HFA as the primary recipient of CBDG funds creates the potential for this, already heavily used, Authority to be overburdened with assigned programs beyond its staffs’ scope and capacity.

As of September 2022, according to VI Housing Finance Authority:

A potential example of this maxing out of capacity for the authority is the current status of the EnVIsion Tomorrow Homeowner Rehab program. Designed to support homeowners repair and rebuilding after disaster, the program enables eligible households to have up to $350,000 worth of work towards rehabilitating their homes. A critical effort as 52 percent of all housing stock in the territory experienced major or severe damage, the program has experienced significant program