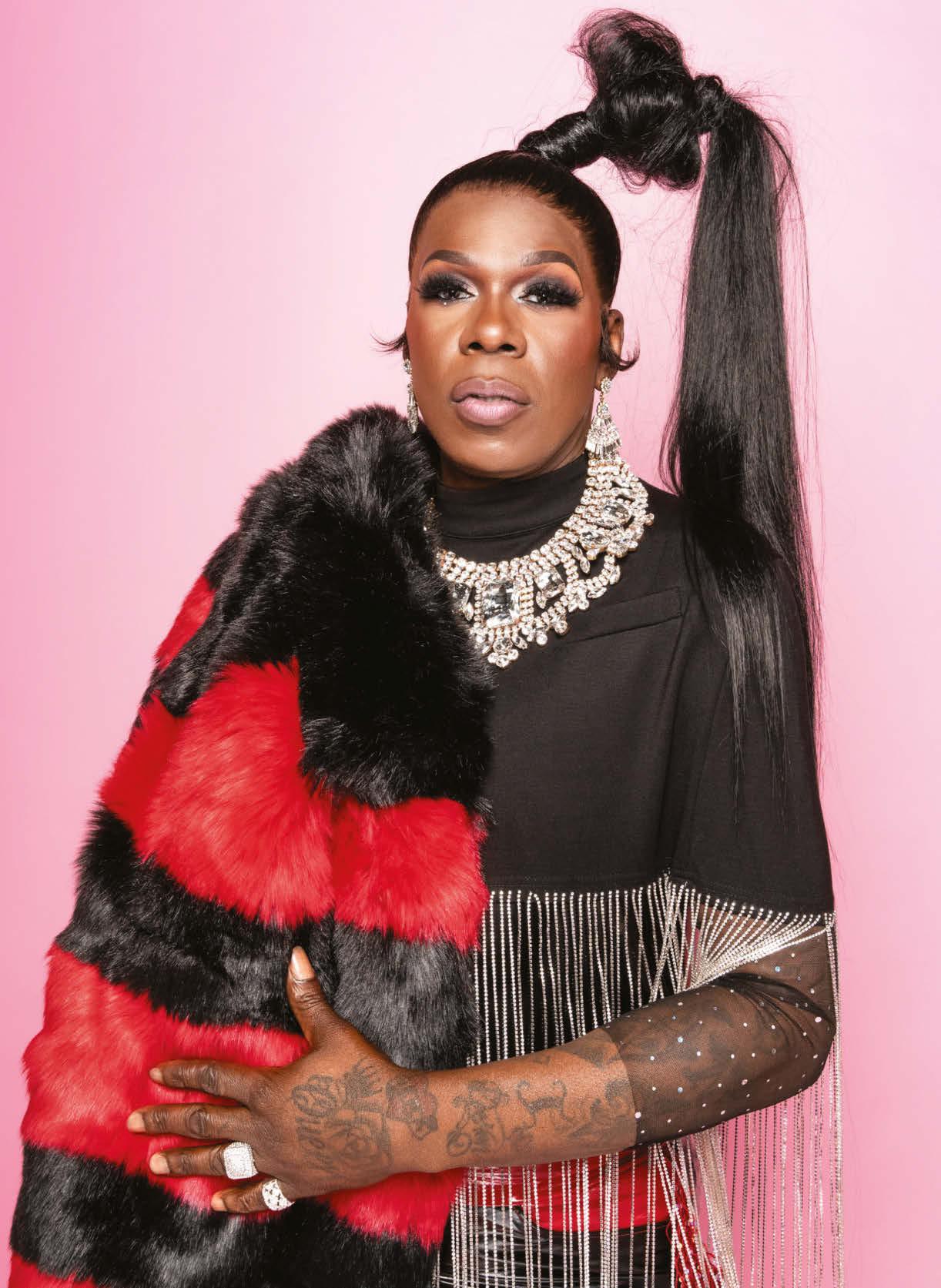

BIG FREEDIA IS READY TO SPREAD THE LOVE— AND THE SOUND OF NEW ORLEANS—AROUND THE WORLD

BIG FREEDIA IS READY TO SPREAD THE LOVE— AND THE SOUND OF NEW ORLEANS—AROUND THE WORLD

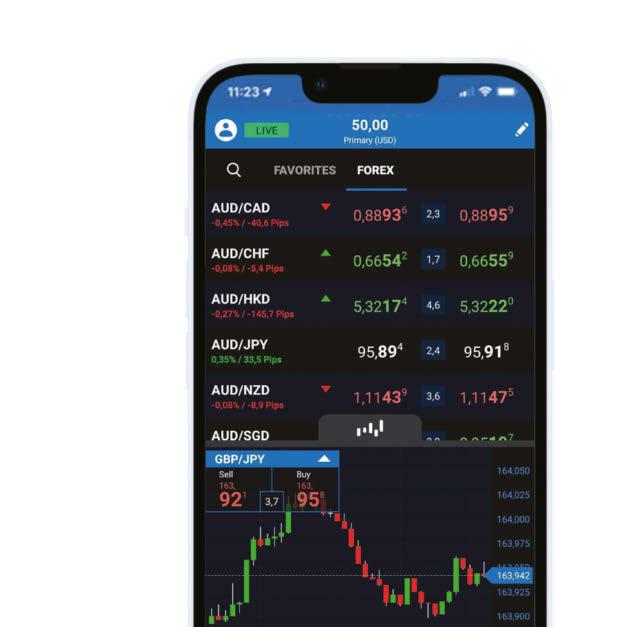

Leveraged trading in foreign currency contracts or other of-exchange products on margin carries a high level of risk and may not be suitable for everyone. We advise you to carefully consider whether trading is appropriate for you in light of your personal circumstances. You may lose more than you invest. We recommend that you seek independent fnancial advice and ensure you fully understand the risks involved before trading. Trading through an online platform carries additional risks.

In extreme conditions it’s all about knowing how to adapt. Seize opportunities and lead the way. Trade FX and crypto through one award-winning app.

oanda.com/rbny

For outsiders, it can feel like New Orleans is throwing a culturally rich celebration year-round. But nothing compares to the festivities around Mardi Gras, when the pageantry soars off the charts. This issue has numerous stories that celebrate the people and events that lend texture and personality to North America’s most epic carnival. There is, for instance, a tribute to Red Bull Street Kings, a raucous competition in which the city’s top brass bands showcase their extraordinary talents.

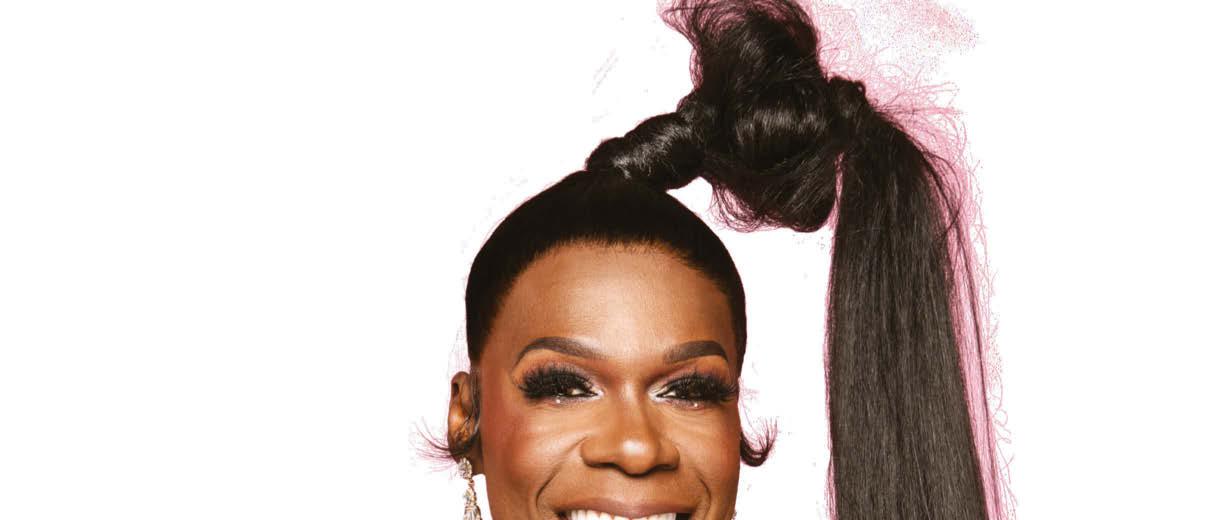

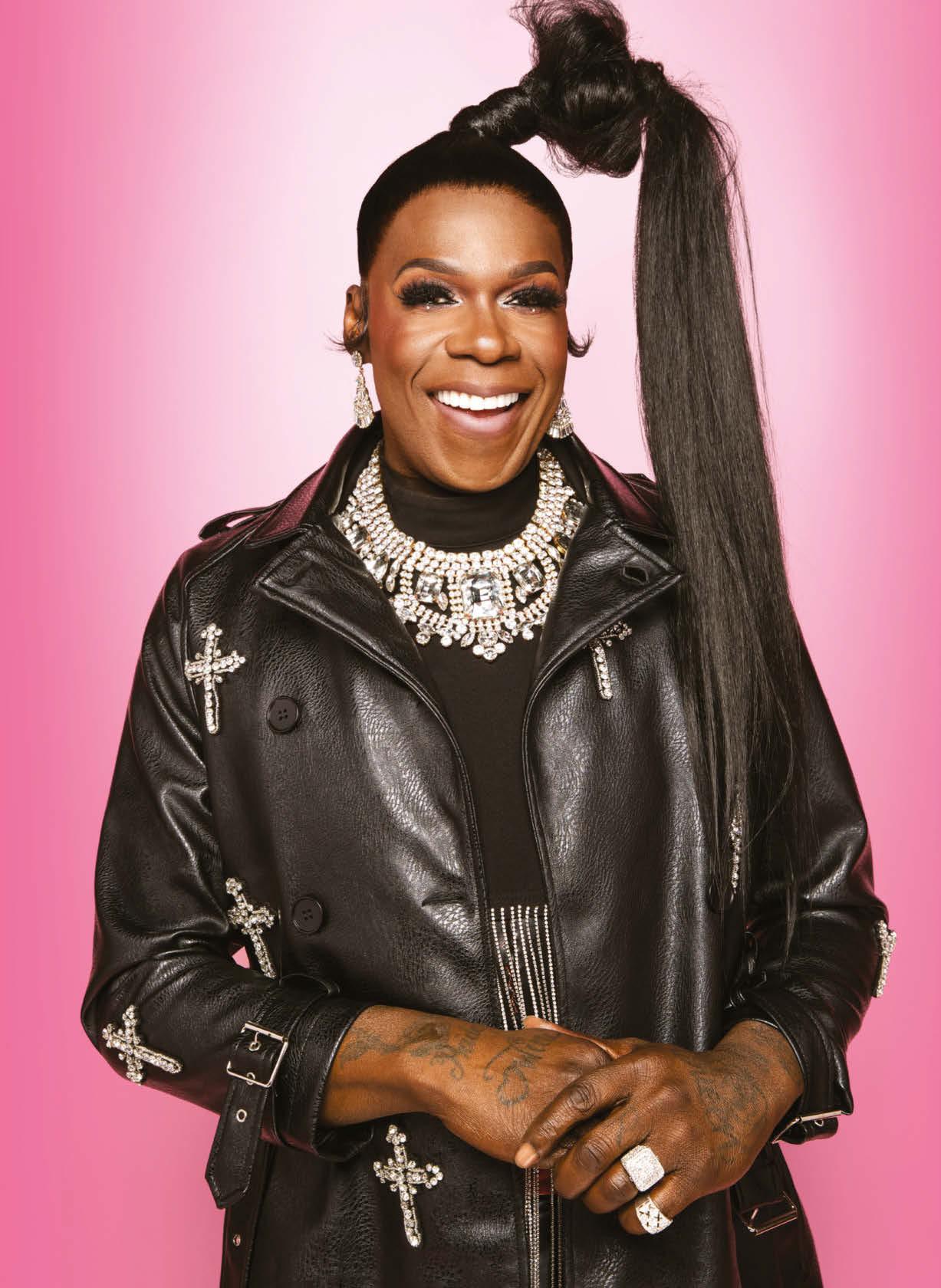

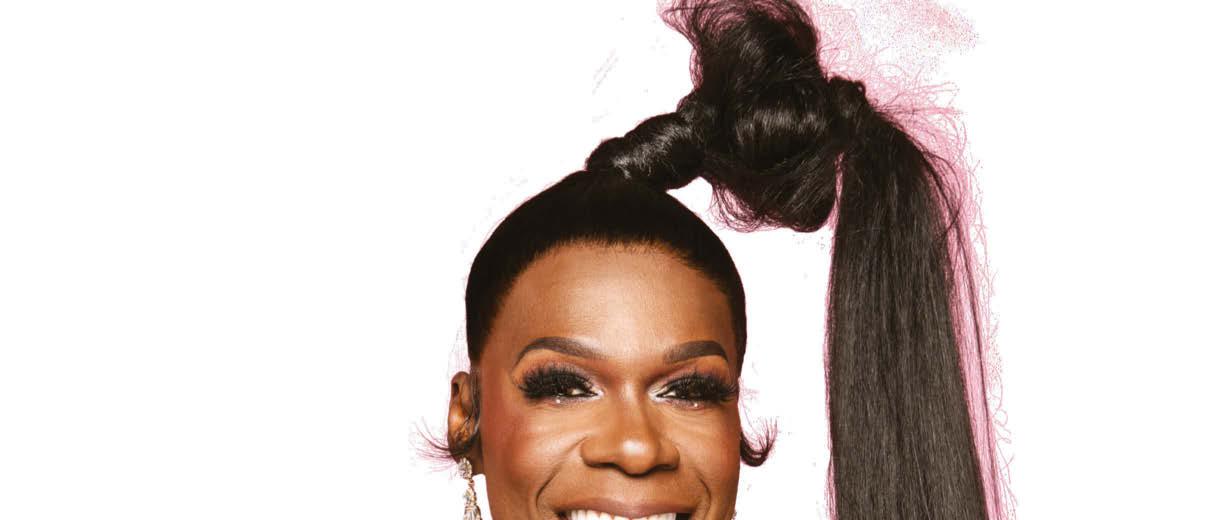

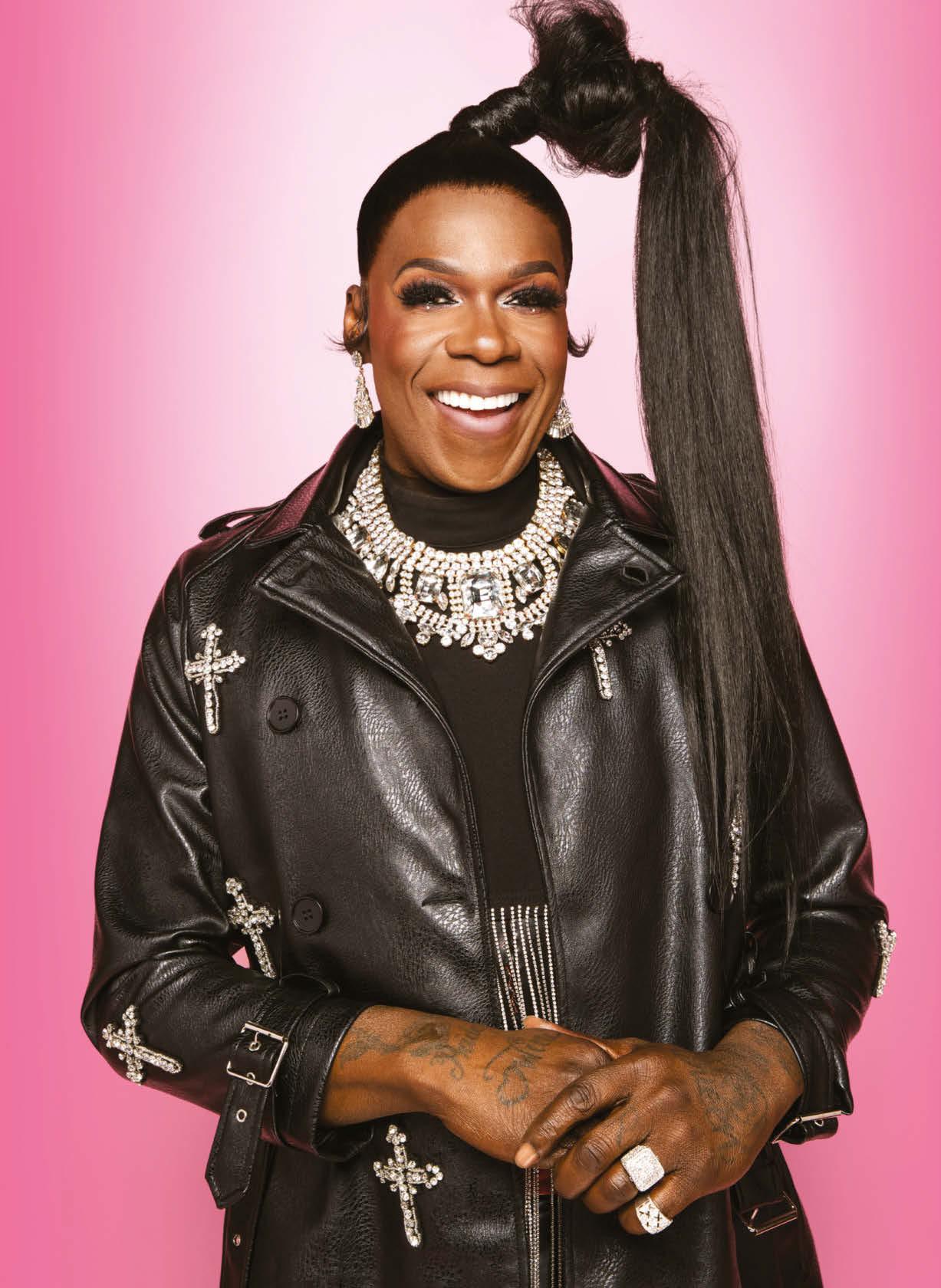

New Orleans hip-hop icon Big Freedia, who has propelled bounce music into the mainstream, collaborating with legends like Beyoncé and Drake. Along the way, she’s been a tireless ambassador for the region, a dependable source of love and inclusion and booty-thumping good times. Sometimes life is tough, and sometimes life is a party. Like Freedia, we’re in favor of embracing the party.

“New Orleans always wraps me up in its spirit whenever I’m there, and this time Big Freedia did too,” says the Brooklyn-based author of our cover story, who wound up interviewing the artist during a tornado. “I’d watched Freedia on reality TV and seen she was a genuine person, but her authentic kindness in real life had such an impact on me.” Starling has worked with The Fader, Teen Vogue, Spin and Netflix. Page 22

The New Orleans–based photographer says he was surprised how much prep time went into his cover shoot with Big Freedia. “My main goal was to make Freedia as comfortable as possible while not wasting any time,” says Williams, who has worked with brands like Tissot, Starbucks and Capitol Records. “Freedia was super easy to work with and I am forever grateful to have the opportunity to make these photographs.” Page 22

Big Freedia is ready to spread bounce around the hip-hop universe with the grace of a leader who deserves her crown.

At Red Bull Street Kings, New Orleans’s finest brass bands went head to head, but the live audience was the big winner.

Legendary hip-hop mogul, NOLA native and Red Bull Street Kings judge Mannie Fresh shares the secrets to his success.

In 2022, Nelly Attar became the first Arab woman to summit K2, and she’s inspiring millions of women to move their bodies.

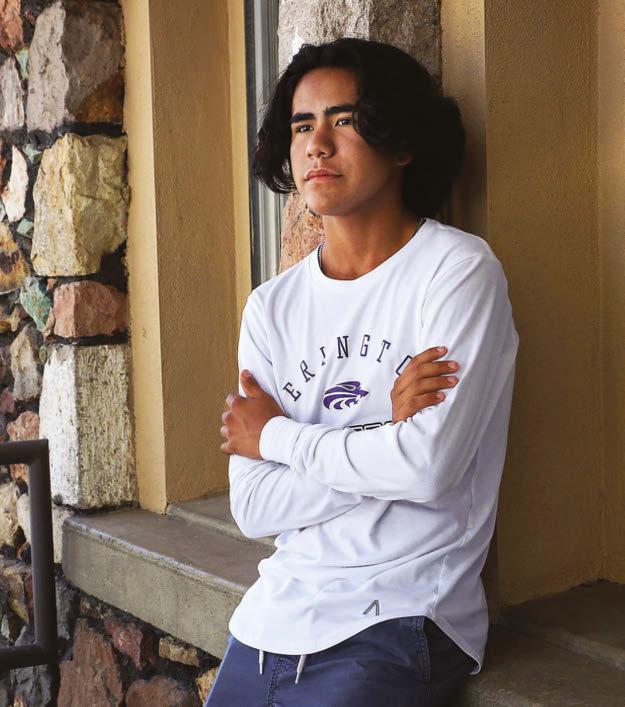

Nevada high school state champ Ku Stevens runs to honor his Native American ancestors—and to illuminate a dark history.

Why are pro gamers flocking to a Dallas suburb? In Call of Duty: Warzone, where every millisecond counts, it’s all about the ping.

More than a decade ago, Big Freedia propelled bounce music into the mainstream. “I love what I do,” she says.

As a senior at Yerington High School in Nevada, Ku Stevens broke the state record for 3,200 meters.

48

ICY HOT

Nelly Attar recently reached the frigid top of K2, but she largely trained in desert climate near her home in Riyadh.

Taking You to New Heights

9 How Tekken pro Cuddle Core is changing the game

12 Tennis pro Stefanos

Tsitsipas’s mental magic

14 BMXing and kitesurfing in the Netherlands

18 Indie-pop star Tegan Quin on her new TV show

20 Artist-producer Danger Mouse shares his top tracks

Get it. Do it. See it.

77 Travel: Four perfect ways to experience New Orleans

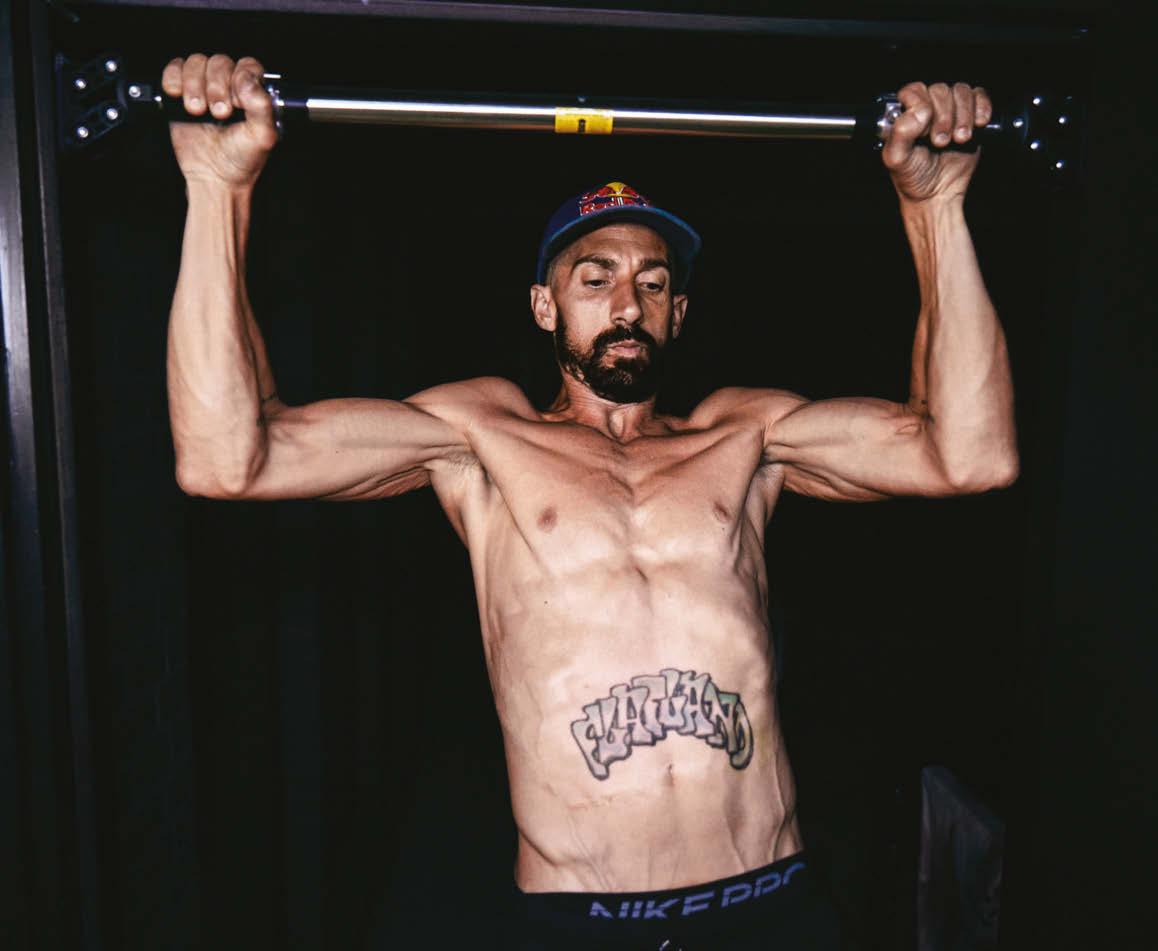

80 Fitness tips from BMX flatland pro Terry Adams

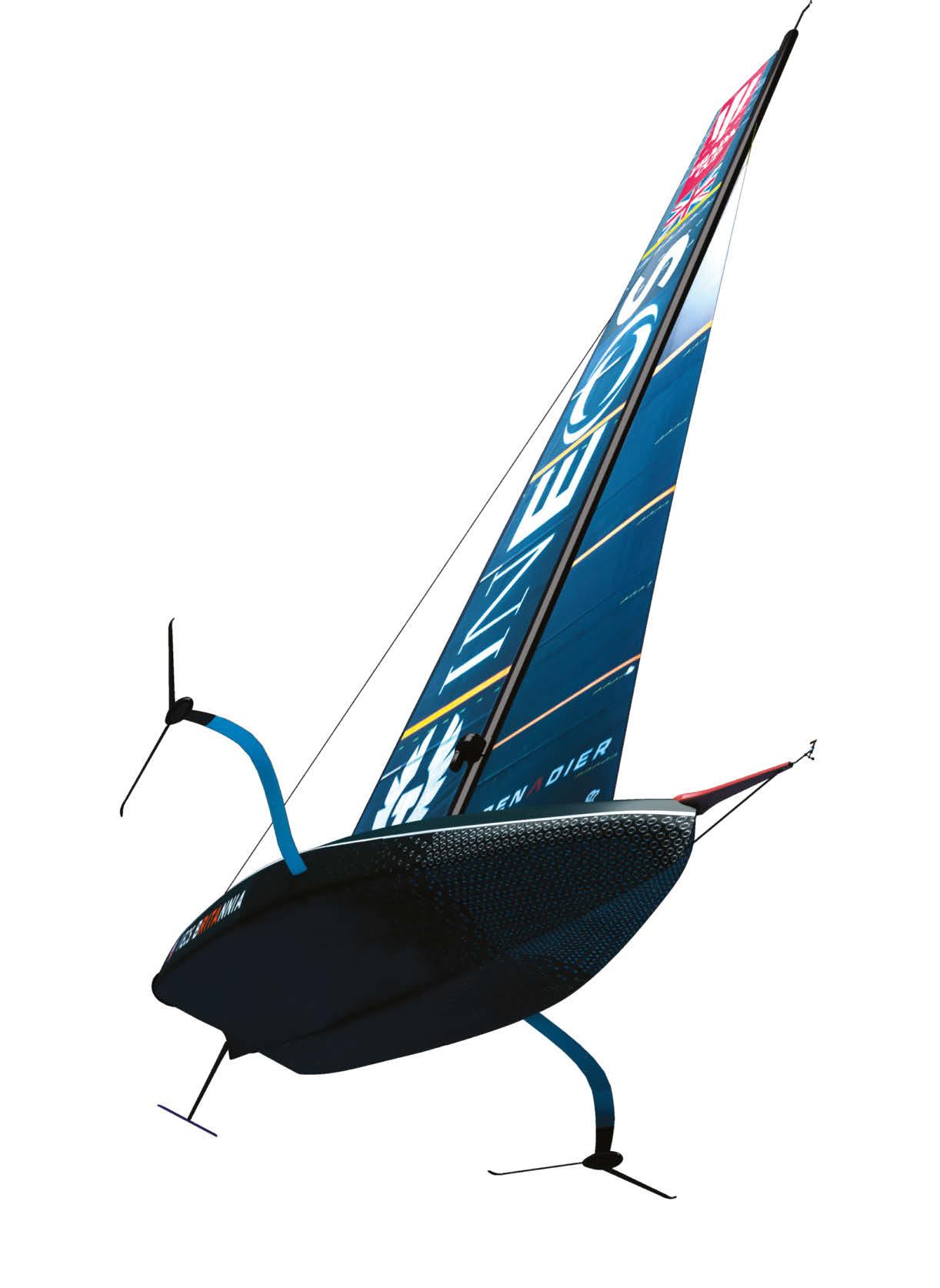

82 How the America’s Cup yachts travel at top speeds

86 Dates for your calendar

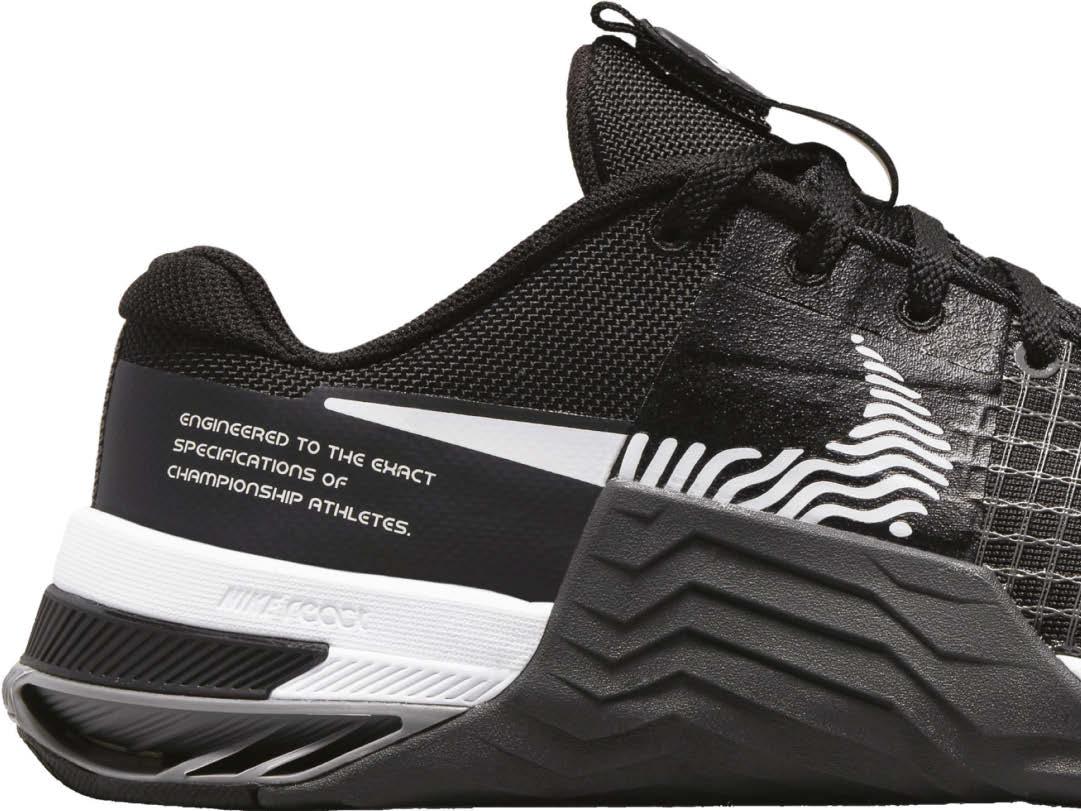

88 The best new athletic shoes

96 The Red Bulletin worldwide

98 Finding balance in NOLA

How Tekken pro Jeannail Carter— aka Cuddle

Core—is racking up big wins and changing the face of competitive gaming.

Words PETER FLAX

Jeannail Carter is a pioneer, breaking ground with scrappy resolve. The 28-year-old pro—who plays under the nickname Cuddle Core—is a rising talent in the fighting game Tekken. And now, her impact, as a voice and symbol for representation in esports, is reverberating through the broader culture. Her face has adorned a Times Square billboard because her success has larger meaning.

Carter’s gaming journey began early. Growing up in a Chicago exurb, she remembers being riveted as her father threw down in PlayStation fighting games. When she was only 5 or 6, she grabbed a controller to make her Tekken 7 debut. Carter, who also loved watching martial arts movies, was hooked. “What can I say—I love to throw hands,” she laughs.

And yet, while a lifelong love affair with Tekken was taking root, Carter didn’t contemplate a career as a pro esports athlete until she was in her 20s. She had a passion and talent for art and wound up earning a degree in illustration. “During college I was playing, but only when I had time,” says Carter, who dubbed herself Cuddle Core as a reference to the remixes in the game Dance Dance Revolution.

Everything changed after she graduated in 2018. She got invited to join a televised Tekken tournament, where a strong performance led to an invitation to join the Equinox pro team. What came next was a leap of faith. “I was on a different career path but I took a chance,” she says. “That decision changed my life.” Though Carter moved to play for Counter Logic Gaming last year, Equinox CEO Emily Tran remains her mentor and personal manager.

Carter has worked hard to refine her Tekken skill set, but she clearly has innate talent and a distinctive playing style. “People say I have an offbeat timing,” she says. “I love movement, to manipulate my opponent’s decisions. And I’m never afraid to throw hands in very close quarters.”

While Carter’s career is a tale of triumph, she has faced sadly predictable obstacles along the way. To be blunt, Carter does not look like the typical elite Tekken pro. Most dominant players come from Japan, Korea and Pakistan. And the majority of pros are men. And historically, few Black players have reached the sport’s upper echelons.

As success came, Carter learned that many people in gaming culture were not ready to embrace an American Black woman as a rising star. The trolling on Twitch and YouTube was harsh. “People would talk about my appearance, or debate my sex appeal, or compare me to top women from Japan,” she recalls. “There was a lot of conversation about things other than my performance or the joy I felt for the game.”

She learned to develop a thick skin. “I had to be numb to it—people who have a problem with Black women in gaming don’t deserve my energy,” she says. Luckily, she found respite in competition. “When I’m on that stage, I forget everything.”

Still, the negativity hurt, and she saw that trying to ignore it wasn’t a great longterm strategy. In the past 18 months, Carter has pursued therapy that she says has been beneficial to her well-being and gaming performance.

“Competing in tournaments is already super stressful and now I feel better about myself and more confident than I’ve ever been,” she says.

In that same time frame, Carter has intensified her collaboration with her coach and begun intensive work with a mental-performance specialist. Now her routine includes meditation, deepbreathing exercises and positive-affirmation rituals. She does weekly sessions with her coach to deconstruct past performances, study game analytics and craft solutions to tricky scenarios in Tekken. And she’s approaching her fitness with new resolve— going on 45-minute runs and working on upper-body and core strength. In short, Carter is doing everything she can to pursue Tekken glory.

It’s working. For 2022, she gave herself a playfulsounding goal with serious underpinnings. “I wrote down that I wanted to win more shiny medals,” she laughs. “The medals are a visual representation of the success I want to achieve. Having a lot of medals means that I was consistently competitive in tournaments.” Indeed, in 2022, Carter won an important tournament and finished in the top 8 ten times.

Carter plans to continue her upward trajectory for 2023—“I’m focused on consistent performance and recovery,” she notes—and is also focused on growing her impact outside the sport. She is grateful and humbled by the positive reaction to her success and outspoken advocacy for representation. In five years, Carter has evolved from an art student to a pro gamer who is inspiring a ton of aspiring players—people who previously didn’t see someone who looked like them in the elite ranks—to pursue their dream. “It matters that people can see themselves in spaces they care about,” she says.

Carter’s passions are driven by a profound love for the

game that has provided her an unexpected career path and a platform to promote positive change. Part of it is how Tekken appeals to the artist in her. “It’s a 3D game, which demands creativity,” says Carter, who loves to draw portraits and natural scenes with colored pencils in her

precious downtime. “And it has such thoughtful character design—the animation is beautiful, and the color and music themes are so creative.”

But it’s even deeper than that. “I appreciate how five people can play the same character and everyone is different,” Carter says, talking

about the personal growth her love of Tekken has allowed. “It’s a way I get to express myself. When I play, my heart explodes out of my chest. I feel so sure and confident about what I’m doing—I get to put in the hard work and show it to everyone. That gives me energy and joy.”

The woman known as Cuddle Core is making an impact within Tekken, and as a powerful voice for change within esports.When the Greek tennis pro wanted to uncover the secret of winning, he discovered the answers were all inside his head.

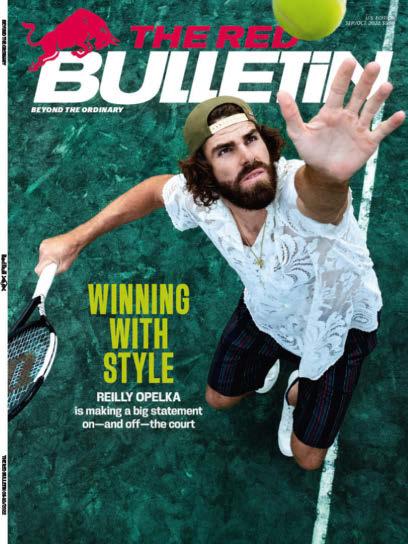

Greek tennis ace Stefanos Tsitsipas, presently ranked fourth in the world, first picked up a racket at the age of 3, and now, at 24, he’s one of the sport’s elite competitors. Last February he celebrated his 200th tour-level win; two months later, in his adopted home of Monte Carlo, he joined the select set of players who have successfully defended an ATP Masters 1000 title. Plus he has an Instagram account dedicated to his perfect hair.

But, as this year’s Grand Slam season looms, there’s no time for Tsitsipas to rest on his laurels. He’s hungry for a win, and as Tsitsipas tells us, it will all come down to mental magic. The following is an excerpt from his conversation on the new podcast, Mind Set Win.

the red bulletin: What’s your best mental strength?

stefanos tsitsipas: Patience. I think this is something that this generation lacks. Especially with social media, they’re very impatient and want everything done right here, right now.

Have you always been a patient person, or is it a skill you’ve honed?

I was a pretty hyper kid, but I learned with time to become slower-paced, to think about my intentions. It’s important to know when to let go, to reflect

and to appreciate the small things you’ve been able to contribute to what you’re trying to do, even if it’s [only] adding 1 percent. Some people want big results too soon.

How does patience improve your game on the court? There were two times when I found myself in the same situation with the same opponent, but [it was] a different Stefanos each time. The first time I faced Rafael Nadal at the Australian Open in the semifinals [in 2019], I was really impatient. I remember thinking, “OK, I’m playing against one of the best. I really need to prove myself with big shots and go for it.” [He lost to Nadal in straight sets.] Two years later, I faced him again at the same tournament, this time in the quarterfinals. After going two sets down, I understood what I was doing wrong. I remember coming to an agreement with myself, saying, “OK, you’re going to become patient. You’re going to wait. You’re going to spend every single minute on the court enjoying the play and just make it a fun game.” It turned out to be one of the best comebacks in my career so far. [Tsitsipas fought back to take a surprise victory in five sets.]

How did that feel?

How can I describe it? It felt like

I was in a cage and someone decided to unlock it. I suddenly felt free. Every decision I went for felt right. It’s what I like to call flow. I was able to reach that flow by decreasing my expectations. It was a pure fight. It was all mental. It was excruciating, physically and mentally—I don’t think I’ve ever played at such high focus levels for so long. Everything felt like it made sense. It’s like a drug when you’re able to experience it—it brings you to another level. You’re not playing with your skill anymore, you’re playing with your soul.

Can you find your flow whenever you want?

I had this conversation with my mental trainer: How can we get into that flow state more often? The answer, surprisingly, is that you just have to let go. You can’t think you want to be in the flow state or you’ll never reach it. It happens gradually; it builds up. It’s a climax you reach when you stop overthinking and just act, using more of your instinct.

Do you have a mental goal?

To be the most positive guy on Earth, I guess.

Can you always remain that positive as a competitor?

That’s a tricky question. Criticism is important—I like receiving it. When I was younger, I was very sensitive to it, but as I’ve got older I think it’s essential. It’s the only way you can achieve perfection. I mean, perfection doesn’t really exist, but you can get close. That also comes with your attitude to what you do. If you do it with love and care, if you wake up every morning and do the best things to succeed in what you do, with people who are chasing that same dream, anything is possible. With your mind, you can achieve everything you want in life. That’s where it all starts. It all starts with an idea. To hear the full conversation, visit redbull.com/MindSetWin

“IN THE FLOW, YOU’RE NOT PLAYING WITH YOUR SKILL BUT YOUR SOUL.”

When Aaron Zwaal attends a shoot, it can mean one of two things. The Dutchman doesn’t only take pictures of athletes like BMXer Daniel Wedemeijer, seen here; since 2018, he has also worked as a military photographer for his country’s Ministry of Defense. This image earned Zwaal a semifinal spot in the “Energy by Red Bull Photography” category of Red Bull Illume. “Daniel asked me to take a photo for a flyer for a BMX event,” says Zwaal, “but we made the most of the shoot while we were there. We were blessed with a dry skatepark and some puddles, which resulted in this close tire slide . . and a wet camera.” aaronzwaal.com; redbullillume.com

Rein Rijke’s global photographic project “The Last Line,” featuring professional kitesurfer Roderick Pijls, also has environmental destruction as its focus. “[The title] refers to the last line Roderick can surf, because all the places we visit are affected by human interventions that cause climate change,” explains the Dutch lensman. When the pandemic hit, they were temporarily forced to go local, but this was no hindrance for Rijke: “Kitesurfing the Waddenzee with low tides has been on my list for a long time. It’s a saltmarsh wilderness, and the high and low tides have a great influence on the area. That gives a very unique perspective from the sky.” The project was honored by Red Bull Illume; this shot was a semifinalist in the “Masterpiece by SanDisk Professional” category. zoutfotographie.nl; redbullillume.com

The 42-year-old singer-songwriter on the strangeness of heading back to high school to see her life story turned into TV fction.

Tegan Quin is used to sharing her life with the public. The singersongwriter is one half of successful Canadian pop act Tegan and Sara, which she started with her identical twin sister in 1995, writing about small-town life in Calgary, Alberta. The duo won international success by the age of 15; they had a record deal before their 18th birthdays.

From their very first song, “Tegan Didn’t Go to School Today,” Tegan and Sara’s music has been intensely autobiographical, sharing their most private thoughts and feelings, so it made sense when, in 2019, they published a successful memoir of growing up in the ’90s. “It feels like you know everything about me, and that’s my job,” says Quin. “Because Sara and I have shared so much about what it was like to grow up together, people feel really close to us.”

Now, Quin is sharing her life once again in the Amazon Freevee TV series High School, a fictionalized coming-of-age comedy written in collaboration with actress-director Clea DuVall. The series, which stars real-life twins Seazynn and Railey Gilliland, follows a year of the Quin sisters’ adolescence as they discover music and explore their identities and sexuality (both Tegan and Sara have openly identified as queer since the start of their careers).

Here, Quin (pictured opposite, left, with Sara) speaks to The Red Bulletin about

fictionalizing her own life, the importance of centering queer narratives and how she hopes the TV series will correct people’s assumptions of what it means to be a twin.

the red bulletin: Were you nervous about allowing your life story to be fictionalized? tegan quin: We clearly feel compelled to share stories about ourselves. I think the discomfort we sometimes feel in revealing our personal lives is worth it. There are so few stories like ours, so few queer stories that get told, especially when you really look at the intersection of being queer women and creatives and songwriters. We so rarely see stories about women being creatives. It felt important and worth the risk.

Was representing a queer female story a driving force?

Yeah. I love a lot of the queer TV, but some of it—especially what’s aimed at adolescents and teens—feels a little neutered. I feel like this show is more real. It’s like a group of friends hanging out in the ’90s, figuring out who they are.

You went back to your old high school in Calgary to shoot the series. How was that? Surreal. It was so weird to watch the monitors and to see our story play out in front of us. The biggest mindfuck, though, was thinking about what dirtbags we’d been at school. I don’t think anyone expected much of us, but now we’ve had a very

successful career and we’re back in Calgary filming this show based on our lives.

You found Seazynn and Railey on TikTok. Were you nervous to cast sisters with no acting experience?

I think people thought we were crazy for suggesting it. We saw the twins on the app and it just felt right. They worked so hard with an acting coach and trained in music, and they’ve amazed everyone with their performances.

Do you recognize yourselves in the characters they’ve created? Sara and I were very verbose and hyperactive, quite extroverted and outgoing in high school. I feel like Railey and Seazynn’s performance shows more of our internal world. I see so much of how I felt on the inside, how I was privately struggling. Railey and Seazynn brought so much of themselves into their roles, and Clea [DuVall] and Laura [Kittrell, scriptwriter] put parts of themselves in there, too. Because of that, I never felt like I was watching myself. It was easy for me to disconnect and just watch it as a beautiful story about girlhood and adolescence.

What was it like to work with another set of identical twins?

Meeting Railey and Seazynn was so good because I’d never been friends with other identical twins before. So much of what they said was just like me and Sara. They love each other, they do everything together, and yet they still struggle with that pull to be their own person. High School is a beautiful, nuanced portrait of what it’s like to be a twin, and I think it’ll resonate with people. You don’t have to be a twin to know what it’s like to feel lost in a crowd or next to those you’re closest to. Everyone knows what it’s like to feel overshadowed.

High School is available to watch now on Amazon Freevee

“THERE ARE SO FEW QUEER STORIES THAT GET TOLD.”

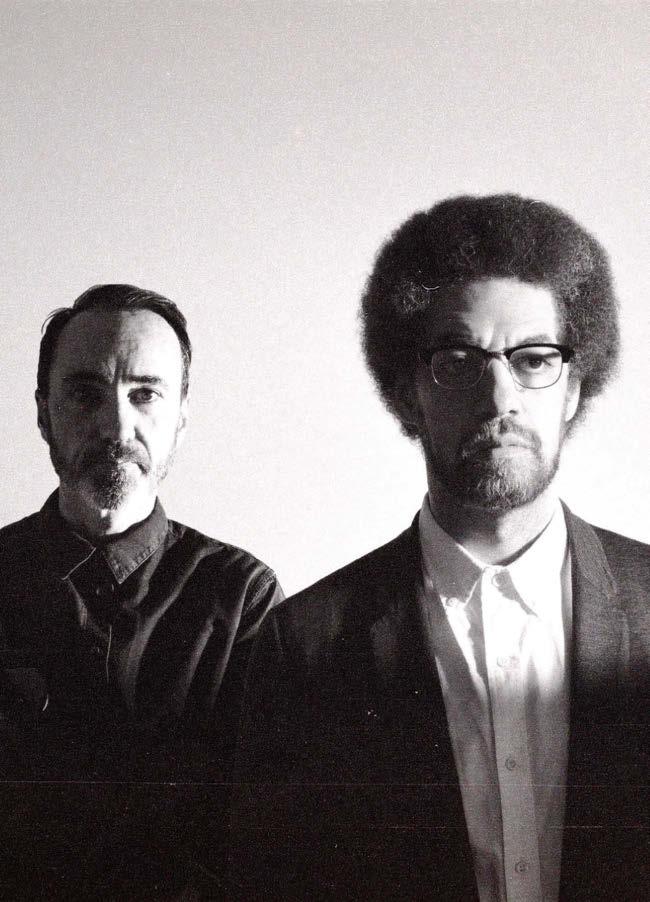

Artist-producer Danger Mouse picks four songs that helped defne his musical journey.

Brian Burton, aka Danger Mouse, has produced tracks by some of music’s biggest names—Adele, Gorillaz and the Black Keys among them—but also has an impressive résumé as an artist in his own right. His solo breakthrough, 2004’s The Grey Album, mashed up vocals from Jay-Z’s The Black Album with samples from the Beatles’ 1968 “White Album,” and as half of Gnarls Barkley he was responsible for the 2006 hit “Crazy.” To mark the release of Into the Blue, the third album by Broken Bells—his project with singer James Mercer of the Shins (pictured, left, with Burton)— the 45-year-old picks four songs that left a mark on his life. brokenbells.com

Scan to hear our Playlist podcast with Danger Mouse on Spotify.

GENE CLARK

“FROM A SILVER PHIAL” (1974)

“This is a beautiful song [by former Byrds member Clark] about how, in a way, you get closer to people who can hurt you; in order to not get hurt more, you get under their wing. Musically, the song is a mix of country and gospel. It’s very soulful and has this real melancholy, soulful element that comes in. It’s just one of my favorite songs ever.”

THE SHINS

“PHANTOM LIMB” (2007)

“I remember when I first heard ‘Phantom Limb.’ I loved it. James [Mercer, his Broken Bells bandmate] has a melodic sense that’s so unique; he’s one of those people who, like the Beach Boys, can make a song sound so pretty and upbeat but still inject that melancholy into it. I don’t know what the lyrics are about. I don’t even want to know, so I can just make the song my own.”

THE CHURCH

“UNDER THE MILKY WAY” (1988)

“This song [by rock band the Church] is one of my favorites of all time. I kind of wish I was a teenager when it came out, but I was only 11 at the time. I almost feel as if I was going through a heartbreak when I first heard it, though. [Laughs.] It makes me feel that melancholy and nostalgia of being young and getting your heart broken. I love that era of music so much.”

“This is an epic cover of Burt Bacharach’s ‘Walk on By’ that defined a whole sound for me when I was in college. It combined the soul music my parents used to play, the hip-hop feel that influenced me in my youth, and the Pink Floyd–sounding psychedelic prog stuff I loved at that time. And it’s 12 minutes long. I love the intent of that—it’s an artistic statement.”

You want to stick out and energize your content like a pro? Using the right music in the right way does the trick!

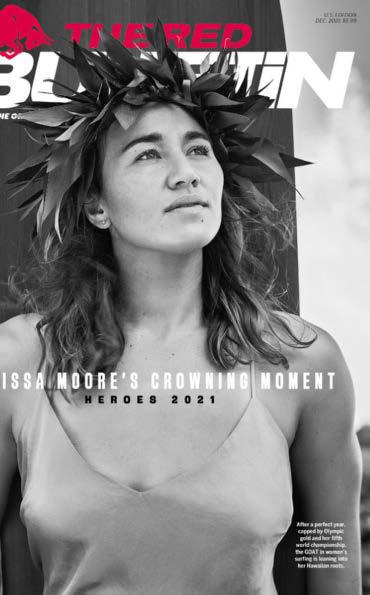

After propelling New Orleans’s bounce music into the mainstream more than a decade ago, the charismatic rapper and reality star Big Freedia is ready to spread her sound around the world with the grace of a leader who deserves to wear her crown.

Words LAKIN STARLING Photography JUSTEN WILLIAMS

Words LAKIN STARLING Photography JUSTEN WILLIAMS

and the sounds of deep belly laughs and playful banter are echoing off the walls of Tipitina’s, a historic music venue in New Orleans’s Uptown district.

The ceiling beams of the performance space are plastered with vintage show bills featuring famed artists like Irma Thomas and the Professionals, Fela Kuti and Taj Mahal, but just past the dance floor there’s a side corridor that leads upstairs to the green room, where another music legend is getting ready. Floating down from the break area, one infectious set of cackles stands out from the others. The resounding voice is magnetic, highly coveted, and it belongs to none other than the anointed bounce-music star and LGBTQ+ icon, Big Freedia.

Surrounded by her close-knit team, the “Queen Diva” is sitting pretty on a black leather couch as she admires herself in the mirror just before she starts a quick on-camera interview. At 44, Freedia is looking confident but slightly demure, flaunting soft glam, fan-like eyelashes and crystals that dazzle everywhere from her earrings to

the cropped seams of her top. Her sheeny, jet-black hair is slicked up into a high-teased ponytail, making her appear even taller than her 6-foot-2 frame.

“Yes honey, shine bright like a diamond,” Freedia playfully sings in response to a compliment she gets on her shimmering look. She is a gem in more ways than one.

For more than 20 years, Freedia has been working tirelessly at her craft while taking bounce music around the globe. She’s released multiple EPs, an album, published a book in 2015 (Big Freedia: God Save the Queen Diva!), led six successful seasons of her reality show (Big Freedia Bounces Back), is currently filming a new spin-off series (Big Freedia Means Business), and she’s working on a new album. In the last five years, she’s been tapped for collaborations and samples by artists like Drake, Lizzo and Beyoncé on more than one occasion. And most recently she received a long-overdue acknowledgment by earning a 2023 Album of the Year Grammy nomination for her work as a songwriter on Beyoncé’s Renaissance

“I’m forever grateful to come full circle with it all, to have a nomination and finally get the credit that I’m on a song as a writer,” Freedia says. “I get

to see something for all my hard work. I don’t need the validation, though. I’ve been working for a long time.”

Born out of New Orleans housing projects in the late 1980s, bounce is the manifestation of the soul, nerve and vibrancy of the city. The hip-hop subgenre combines upbeat tempos, a punchy bass and vocal repetition, which makes it impossible not to bounce your bottom while listening. Performing everywhere from small sweaty clubs to big concert venues, Freedia and her trusted crew of dancers have been all gas, no breaks in their mission to get crowds to move their bodies to music. For Freedia, ensuring that people walk away from her show feeling freer than when they walked in is key. “Commanding asses across the world” is what she calls it.

Freedia is firmly in control when she’s on the mic. Her ability to call a tune was nurtured during the years she devoted to singing with the acclaimed Gospel Soul Children of New Orleans and as an assistant director of her church choir. “Those were my early days of finding myself,” she says. “The church was my safe haven. My godmother, Georgia, who was the choir director at my church home, opened her arms really wide and accepted me.”

For 20 years, Freedia has been honing her craft. She recently earned a 2023 Grammy nom for Album of the Year for her work on Beyoncé’s Renaissance

“I was a heavyset choirboy from New Orleans,” she says of her childhood. Long before she created a sanctuary through bounce, Freedia was known as Freddie. The church was a refuge and a chance to get away from the hood where Freddie grew up. Her mother, a hairdresser, and father, who worked as a truck driver, did their best to provide a good life for Freddie and her brother and sisters. Then, just before Freddie entered ninth grade, her parents’ hard work paid off, and the family moved into a house in a better neighborhood, where she was a budding student at Walter L. Cohen High School in Uptown.

“I was always the one loud and out at school. Everybody knows who Big Freddie is,” she says with a laugh. “When I would come down the hallways, I would be hitting choir notes. Most people loved it, some people hated it. But it was just my unique calling.”

Freedia understood her gifts at an early age and didn’t shrink to conform. She was a light who kept an open mind and always tried to give people chances. It wasn’t always the easiest disposition to have growing up as a young, Black, queer person in the Deep South—where sexualities and gender expressions that exist outside of the heteronormative value system weren’t understood or affirmed. “Being Black and gay at that time was not so accepted,” Freedia says. “It was kind of hush-hush and your family probably was embarrassed about having a gay person in the family.”

Before finding her confidence in high school, 12-year-old Freddie came out to her mother, who instantly protected her and allowed her to be her truest self. That support ultimately helped her flourish. “I was scared and I was timid, especially in elementary and middle school, because I was finding myself,” she says. “But in high school, I was the choir director, so I had keys to the auditorium, and I was this queen who was around there like, Girl, y’all ain’t bothering me. I’m running things.”

The day after the photo shoot at Tipitina’s, a deadly tornado is brewing over New Orleans. When I approach Freedia’s house for our interview, the clouds begin to darken, and the wind is whipping trees and hurling leaves at the ground. As my car pulls up, Freedia is standing on the porch of her split-level home, no longer in photo-shoot glam but dressed in a comfortable purple housecoat and matching silk bonnet. She’s finishing up a cigarette while telling a beautiful, black, three-legged doodle named Yoncé to get in the house.

Off the stage and out of the spotlight, Freedia is tranquil and laid-back. “It’s coming down out there, chile—do you want anything to drink?” Freedia says as she looks out a window. I tell her I’m alright for now but jokingly ask her if I get stuck here will she let me spend the night? “If you have to,” she says and assures me with a smile.

Inside her cozy abode and safe from the storm, hand-painted portraits of Freedia are placed all around. The dining room next to the entryway is adorned with white furniture and elaborate place settings that look too perfect to be used for meals. For our chat we sit in the living room on a mustard-colored velvet couch that rests against a matching velvet-and-corduroy wall underneath a neon sign that says “Big Diva Energy.”

When she’s not booked and busy, this home is Freedia’s oasis, where only close friends and relatives are typically allowed to visit. This stable and safe space is a bittersweet blessing for Freedia, who gets a lot of unexpected visitors ringing her bell, asking for favors and pulling her in different directions when she’s not working. “It allows for people to suck things out of me,” she says. “When I’m gone and I’m on the road, I’m being productive and making things happen.” So as snug as it is here, Freedia prefers to be on the go.

In her early 20s, Freedia began performing at block parties for fun. Today she’s taking her sound around the world.

“I was always the one loud and out at school.”

Her strong work ethic has kept her on a rigorous schedule for most of her music career. She’s put in an immense number of hours to stay sharp and on the rise, and these days she’s finally starting to see the fruits of her labor. Is it as simple as her just staying in the studio? “Hell no,” she laughs. “I wish it was that easy but it’s not. From plane to plane, hotel to hotel, city to city, state to state and overseas, it’s quite a load. Cooking things. Sponsorships I have to do promos for. It’s a variety of things, and it keeps me all over the place.”

To have an international impact, Freedia travels everywhere. Bounce music is frequently sampled in charttopping hits, but it’s still not recognized as mainstream on its own. Even though Freedia has been performing for 20 years, there are still more ears to reach and stages to dominate, so she’s always had to wear multiple crowns.

Before she started taking music more seriously in her early 20s, Freedia was a college student at the University of Louisiana studying nursing and had a side

job decorating events for her mother’s social club, the Queen Divas, and other clients. But a fateful performance at a block party with her best friend and bounce music pioneer, Katey Red, created more opportunities to get on the mic.

“We used to play in the projects,” Freedia says of her early days with Katey Red. “We used to beat on electric boxes, and we’d make a beat and start saying any kind of thing. When Katey started in ’98, me and my best friend Eddie would go to the studio with her, go to her gigs, dance on stage, and I started backgrounding for her. And then one day they told me to get on the mic and that was my first actual performance at a block party hyping [it] up. When I started, people were like, ‘You heard what she said?’ ”

After that performance, word spread around New Orleans, and Freedia picked up more bookings for block parties. It began purely as something fun to do and a way to make a quick $50 to $100 per gig. Two years later, in 2000, a local record label called Money Rules Entertainment took notice of Freedia, helped her land

her first club gig and showed her the ins and outs of the industry. A year after that—and with a growing following in New Orleans—she released her first song, “Uh Huh, Oh Yeah.”

Her face lights up as she sings a few bars from the tune. “These hoes, they mad. Your boys, I had. I made my cash,” she laughs. “The girls loved it. It was so messy!”

The girls indeed loved it, and then, many years later, rap superstar Drake loved it, too—so much so that he sampled it for his 2018 viral hit “Nice for What.” Freedia was not invited to appear in the video for the song, however, so when Drake came to New Orleans to record the video for another bounceinfluenced single, “In My Feelings,” Freedia reached out to the rapper to be included. In an interview with TMZ, she called it a step in the right direction: “I think that other artists out there should feel the same way, that no matter what your background is—no matter if you’re a gay artist—that we can be able to be there just as anyone else.”

Part of what makes Freedia so special is that the music she recorded in the early 2000s is evergreen. Ahead of her time, or right on time, she’s always had her finger on the pulse of what bounce music would become to the world beyond New Orleans. In 2005, she fled to Houston when Hurricane Katrina forced her and thousands of others to evacuate. When she returned, she started a party called FEMA Fridays at Caesar’s, the first nightclub to reopen in New Orleans, and never looked back. Freedia told herself she was done with juggling side jobs, working a 9-to-5 and performing five shows a night. Music was going to be her “only child,” just as it had become an extension of her truest self.

“We were displaced all over the world [after Katrina] and people were asking about the sound. A guy called me in Houston and said, ‘Come to Houston. Everybody keeps saying get Big Freedia, and I wanted to know who the fuck Big Freedia is.’ When he brought me to the club, I opened my mouth and it was like the whole choir in heaven started singing behind me,” she says. “It was unbelievable. It was then that I knew I had something special.”

By 2010, Freedia had ventured out of the South to perform in New York City and Los Angeles, and then tastemaker publications started writing about her. When she got recognized in New Orleans by two white guys jogging down the street who’d read an article about her in The New York Times, she knew that bounce music had traveled outside of her community and would change her life forever.

Before Top 40 hits and white audiences became familiar with bounce, Freedia says that the foundations of the genre sprung from pioneers like DJ Jubilee, Ms. Tee, Cheeky Blakk and DJ Jimmy, whose sound was rawer. “Back then, it used to be rough and raunchy,” she explains. “It was gangstas rapping bounce music and they were talking about each other on songs. When Katey and other queens started jumping in, it went another direction because we were able to open up another lane.”

When The New York Times wrote about Freedia in 2010 in the (now problematically titled) article “Sissy Bounce: New Orleans’s Gender-Bending Rap,” bounce artists were primarily

Freedia and her crew are ambassadors of bounce, setting a foundation to teach people about the sound and the culture.Freedia’s music is evergreen. Ahead of her time, or right on time, her fnger is on the pulse.

“Doors are opening and people are seeing that bounce is a big staple in the music game.”

straight Black men. After the high-profile article, which recognized queer artists for their contributions to the subgenre, Freedia says the straight performers started to “back up a bit.” But while the attention pushed Freedia’s community forward, she didn’t like the divisive take on their contributions.

“I had to start telling them we don’t separate it here [in New Orleans],” she says. “It’s just bounce music, and I happen to be a gay artist. You got gay people who do it, straight people who do it, girls, guys.” Ultimately, the residual outcome was a shift that left Freedia and other LGBTQ+ artists at the helm.

When Freedia tells me about the two white guys who recognized her on the street, I can’t help but think about the mostly white audiences who buy tickets to her shows. Indeed, it signifies her crossover appeal, which means more exposure and a rise in global popularity for bounce music, which gives Big Freedia the traction that she deserves. But with that growth there comes a coopting of certain elements—twerking to be specific. In 2013, with the help of Miley Cyrus, it was as if white women suddenly discovered the moves and then cringingly attempted to do them in bars and clubs and on social platforms, even monetizing them through dance classes. During that time, did Freedia ever feel protective of the culture?

“I would be upset about it and then I told myself, You are setting a foundation here of teaching people all around the world about the sound and about the culture,” Freedia says. “People teaching twerking classes, that’s not harming me. But if a big artist came and took my sound and put it on their song and they’re trying to get the credit for it, I feel like, No, I been did that. I been doing this. But now, I’m going down in history. It don’t matter what they do. And if

I have to speak about something or a certain situation I will, and I’m going to do it the right way. They just need to pay homage to the people who have really set the foundation. And it’s not just about me, it’s about the pioneers who have created this sound and the culture of New Orleans.”

And this is why being included in a music video, being listed in the song credits and finally being nominated for a Grammy means so much. “I think things are changing,” Freedia says. “Doors are opening up even wider, and they are seeing that the culture of bounce music is definitely a big staple in the music game.”

Even if Freedia doesn’t feel like she needs the endorsements, it’s really what she’s owed. There have been times when she admits that she felt like giving up because she’s had to work so much harder as a gay artist who presents outside the confines of the gender binary in an industry that has taken way too long to evolve. To remedy this, she’s set boundaries, continues to advocate for herself and her community, raised her price and pushed forward.

Lately, Freedia’s been working to create music that can be played for generations and doesn’t have a time stamp on it, much like she’s done thus far. In 2022, she started working on her new album, titled Central City, which will be released in 2024. The project is nearly done, thanks to a mega recording camp where Freedia and a fire team of writers and producers worked together to create droves of tracks. It’s a doubledisc record that’s a nod to her first album from more than 20 years ago.

“This is like bringing it back to the roots and elevating it with a few different new sounds,” she explains with excitement in her voice. “It still has that raunchy old Freedia that everybody’s used to. It’s my dance/disco album where I’m making the clubs dance down. That music that you can play at festivals. The party is jumping.”

Until then, she’s taping her new reality show, Freedia Means Business, which is set to air on Fuse this summer. The series will provide a look at how Freedia runs her empire, but more specifically, she wants to give young viewers insight into things like finding new business ventures, conducting

themselves in meetings, starting LLCs and paying taxes. Reality TV allows the audience to see Freedia just as I do right now, telling me about her life in her coordinated living room while barefaced in slippers and loungewear. The real Freedia is down-to-earth, caring, calm, hospitable and hilarious.

“You get to see me in my everyday life,” Freedia says. “I’m very humble when I’m not on stage. I’m not loud and don’t want to be seen and all that. I’m the one who’s hiding in the background trying to feed everybody.” While she’s grateful for her growing fame, adjusting to it can be a lot sometimes. Freedia still sees herself as “that hood bitch” who wants to keep normalcy in her life.

“I love what I do. I’m going to bring New Orleans to you.”

These days, when she steps out in public, everybody wants to hear her signature phrase delivered in her singsong style: You al-read-y knooooooow! “Girl, that takes power and energy to do that every time I see a person,” she says. “I’m not in the grocery store trying to say that. I’m trying to get my groceries,” she adds with a laugh.

As the storm picks up, Freedia is debating a trip to the supermarket so she can cook dinner. We wrap the interview early because it’s getting scary outside. Our phones and her home alarm system are blasting alerts, urging people to find shelter from a tornado that is approaching. Freedia—who survived Hurricane Katrina by cutting a hole

through her roof, calling a local radio station for help and getting rescued by a boat—remains serene as the raindrops crash down, lightning strikes and objects in the backyard begin to take flight. While I call a car and gather my things, she hands me a cold bottle of water and notices I have no umbrella. She comes back with a yellow poncho and a plate of 7 Up pound cake, thoughtfully covered in plastic wrap for my journey ahead. Freedia flickers the porch lights to flag the driver down in front of her house, and before I head out into the frenzy she looks at me and says, “If you get stuck at the airport, let me know. I’ll come get you.”

Freedia cares—a lot. More than just the formalities of Southern hospitality,

her kind gestures stuck with me for days after our exchange. It’s no wonder that masses of people across the world assemble to be touched by her glow. This level of intention with a stranger in her treasured home shows the same authenticity that radiates through her music—which is why major artists want in on her special appeal. In their bare form, bounce rhythms stand out on their own, but when Freedia adds her charm and wit, those sounds transform into something extraordinary.

“I love my music, I love what I do,” she says. “I take it and try and enlighten people’s spirits. You might not be able to come to New Orleans, but I’m going to bring New Orleans to you.”

Freedia relishes the spotlight with her dancers Tootie (far left) and Bobbi (far right) and model and chef Adriane.At Red Bull Street Kings, four of New Orleans’s finest brass bands went head to head—and collaborated with a local hip-hop artist—in a cultural competition where the live audience was the big winner.

Words PETER FLAX Photography JUSTEN WILLIAMS

Words PETER FLAX Photography JUSTEN WILLIAMS

So-called Mardi Gras Indians and culture bearers—locals who help keep New Orleans traditions alive and hopping—came out to support and elevate Street Kings.

Kings of Brass didn’t just perform at Street Kings—in the end, the group blew away the judges to win the competition.

As the competition and the mash-up of hip-hop and modern brass heated up, the energy of the crowd was palpable.

a

Downtown Lesli Brown, host of the event, told the crowd, “If your thighs aren’t burnin’ by the time you leave, you done did it wrong.”

Legendary rapper, record producer, NOLA native and Red Bull Street Kings judge Mannie Fresh shares the secrets to his success.

Words CHRISTOPHER A. DANIEL Photography JUSTEN WILLIAMSWhen Mannie Fresh returned as a judge for the Red Bull Street Kings brass-band competition in New Orleans this past September, the producer, DJ and rapper was excited to hear younger musicians in second-line bands from his hometown having fun while they performed. The experience took him back to his own humble beginnings growing up in the 7th Ward in the early 1980s, when streaming numbers didn’t make or break a rapper’s career. He realized that being surrounded by a supportive community, having passion for music and maintaining a strong work ethic were the key elements that enabled his bounce-flavored Cajun sound to become popular both around his hometown and across the world.

“Anybody who knew in the 7th Ward that I was doing music would constantly tell me to get off the block and go finish whatever it was I was doing,” the 53-yearold says today. “The whole 7th Ward raised Mannie Fresh.”

The village that surrounded Fresh ultimately fueled him to become the inhouse producer for the Southern hip-hop label Cash Money Records from 1993 to 2005, as well as one-half of the imprint’s Grammy-nominated duo Big Tymers. Fresh’s 808-fueled, brass-band-inspired tracks earned multiple gold and platinum plaques for major artists, including Juvenile, B.G., (Young) Turk, Lil Wayne and his Big Tymers cohort, Birdman, before he expanded his sound by crafting bangers for N.O.R.E., T.I., Jeezy, Slim Thug, Chamillionaire, Toni Braxton, 2 Chainz, UGK and the late Teena Marie.

Throughout the late ’90s Fresh’s ear was as sharp as his fashion—a familiar uniform of tall white tees, Girbaud jeans, white Reebok classics and solid-colored bandanas or “soulja rags”—his work behind the console generating a cavalcade of Dirty South staples turned pop-culture catchphrases: “Ha,” “Back That Azz Up,” “Bling Bling,” “Get Your Roll On,” “Stay Fly” and “#1 Stunna” to name a few.

Fresh’s stage name comes from his dad, Otto “DJ Sabu” Thomas Jr.—as well as his classmates, who noted his love of brandnew sneakers. The hitmaker’s dedication to creating memorable musical moments goes back to his experience tagging along to his dad’s DJ gigs. The impressionable youngster born Byron Thomas was so mesmerized by watching his father control the crowd the entire night and into the morning that he immediately realized music would be his career path.

“It was the caliber of how I wanted to be,” Fresh says. “He had the crowd mystified, holding on for that next record and how he was gonna drop it for five to six hours.

“The best DJs can change whatever is going on in somebody’s world,” Fresh adds. “If you’re with me for an hour or two, my job is to put you in a good mood and make you forget about every crazy thing that’s going on. If I’ve achieved that, then I’m good.”

Regularly DJing house parties and school dances around New Orleans, a teenaged Fresh joined the Big Easy’s pioneering hip-hop trio New York Incorporated with Mia X and Denny D in 1984. Mia X, who also served as a judge for Red Bull Street Kings alongside Fresh, went on to sign as a solo act with Master P’s No Limit Records in the mid1990s. The two are still based in New Orleans and remain close like siblings despite their divergent career paths.

who were both part of the hiphop crew New York Incorporated in the 1980s, recently reunited as judges for the Red Bull Street Kings competition in New Orleans.

“It’s me hanging out with one of my loved ones,” Fresh says. “We grew up together, so it’s always cool to be with people that’s in your company. We were always cordial and cool with each other.”

Three years later, Fresh linked up with Gregory D and landed his very first major-label deal with RCA Records, where he stuck around until 1993. He also interned at the label, doing everything from taking out the trash to sticking around the studio into the wee hours to help out with drum programs or whatever the session required.

“Whenever everyone else went home, I was still in the studio,” Fresh says. “I did stuff that I don’t see a lot of cats doing these days. Being in the studio and seeing

some of these guys work hard at the music, I picked up that ethic. That’s why I went so hard once I got on.”

Releasing his solo debut album, The Mind of Mannie Fresh, ahead of his departure from Cash Money in 2005, the beatmaker formed his own company, Chubby Boy Productions, and kept the wheels in motion. He churned out “Top Back” and “Big Shit Poppin’ ” for T.I. while providing Jeezy with his breakout single, “And Then What.” Those singles extended his shelf life as a force to be reckoned with.

“After Cash Money, I had a lot to prove,” Fresh says. “Those songs meant everything to me, so those were the moments I knew I was alright. It was a

lot ridin’ on ‘And Then What,’ so I knew if I got it right, the momentum was there.”

Fresh’s longevity and due diligence have inspired New Orleans’s new wave of independent artists, too. Alfred Banks, an MC out of the 12th Ward who performed at Red Bull Street Kings with the winning band, Kings of Brass, looks to Fresh’s evolution and relentless attitude toward music as a blueprint for his own career.

“Mannie and Mia know without a shadow of a doubt that I’m definitely one of the dopest rappers to come out of the city in the past decade,” Banks says. “I’m very confident in who I am and what I do, but that means the most to me out of anything to have bandwidth in their brains to any extent. Their success laid

the foundation for what success could look like for the type of artists they were, so it gave me a template.

“Being independent is a lot of work and sucks at times” Banks adds, “but the payoff is incredible, because I control what I do at all points.”

These days, Fresh is extremely selective about the projects he takes on. He spends the bulk of his time DJing as opposed to posting in the studio round

the clock. Playing for crowds is where he gets his joy and retains his passion for making people escape their troubles.

Even as more celebrity DJs curate playlists and music streaming services barely list producers’ credits for their tracks, Fresh is grateful that he’s still actively booked to rock parties both in the U.S. and abroad.

“It’s a warm feeling when you do something you love,” Fresh says. “Before I was doing beats, I was already popular in my city. I already had this thing in my mind that I was successful, so whatever else happened was all God’s plan. I don’t even call my crowds fans anymore; I call them family.”

New Orleans natives Mia X (center) and Mannie Fresh (center right) pose with their fellow Red Bull Street Kings judges.

NOLA rapper Alfred Banks, seen here performing at Red Bull Street Kings, looks to Mannie Fresh as a role model for success.

New Orleans natives Mia X (center) and Mannie Fresh (center right) pose with their fellow Red Bull Street Kings judges.

NOLA rapper Alfred Banks, seen here performing at Red Bull Street Kings, looks to Mannie Fresh as a role model for success.

“The best DJs can change whatever is going on in somebody’s world.”

Last July, Attar reached the icy top of K2, but she largely trained in desert climate near her home in Riyadh.

In 2022, Nelly Attar became the first Arab woman to summit K2. And back in Saudi Arabia, where women have long been discouraged from physical activity, she’s become a fitness role model, inspiring millions to move their bodies.

Beyond climbing the world’s tallest mountains, Attar’s fitness journey reflects a growing movement in Saudi Arabia to become more active.

ou might picture serious mountaineers as a grizzled bunch, but this one grooves.

Nelly Attar has danced on her way up Mount Everest, her big joyous curls bouncing wildly before reaching the summit. She’s danced on technical Ama Dablam and on mellow Kilimanjaro. She’s even danced on terrifying K2 this past summer. She’s danced when she’s happy, danced when she’s bored, and yes, she’s danced through fear. To her, “movement is medicine.”

Here’s another incongruous fact: This 5’2” powerhouse trained to climb the world’s highest peaks from a home base of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Let that sink in for a moment. That’s hot, flat desert, not mountain snow and ice. Then there are the rules, both written and unwritten, that for much of Attar’s life gave most women and girls little access to sports or fitness—not as athletes, not as spectators, not even in gym class at school. Dancing in public has also been taboo.

“I’ve learned through life there are plenty of opportunities through challenges,” she says. “You just have to be creative.”

Attar’s progression as an athlete— from teaching dance classes underground and opening a wildly influential dance studio to completing marathons and Ironmans to climbing the world’s tallest mountains—is indeed a story of challenges and creativity. But that’s only part of it. Her career trajectory, from psychologist to sports figure, tells another story, too, one that reflects how life in Saudi Arabia is changing, and how Attar is helping to change it.

“I shifted careers to work in sports because in Saudi, that’s what created

Ymore impact,” she says. “Especially in mental health.”

In a country where 60 percent of women get less than 30 minutes of physical activity a week, simply moving the body can be transformative. The physical struggle—of the climb, of the marathon, of a dance class, or an hour spent at the gym—is a way to deal with the rest of life’s struggles: the losses, disappointments, self-doubt, even the hardest thing of all, grief. “It’s the best antidepressant, the best anti-anxiety pill ever,” she says.

Which is the story she very much wants to share with fellow Saudis, with women, with the world.

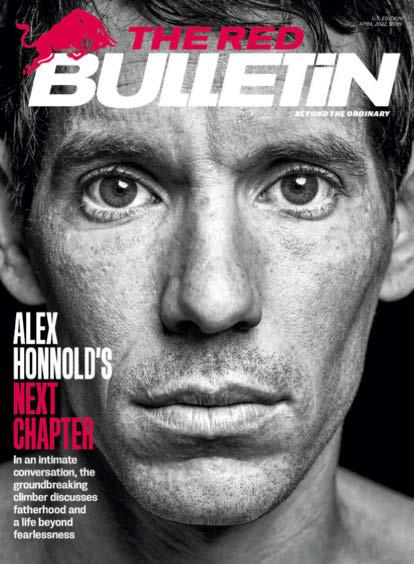

In the record books, Attar’s singular achievement to date is her climb of K2, long dubbed the “savage mountain” because, as one early climber said, it “tries to kill you.” It’s a grueling, weeks-long process that involves a long approach; an acclimatization rotation; avalanche, weather and rock- and icefall hazards; and a looming serac over a steep, narrow passageway that has claimed numerous lives. In July of 2022, she became the first Arab woman to reach the 28,251-foot summit. But in many ways, another first—one that won’t go in any record books—is just as significant. It has to do with dancing.

If you live in a region where dance performances and dance clubs and dance lessons are common, a place where music fans dance at concerts, then this part may be a little hard to grasp. But until relatively recently, dance and music were not permitted in public places in Saudi Arabia. Attar helped open the world of dance and movement to Saudis, which is why we’ll begin the story of her mountain journeys here.

It started with a period of personal challenges. Moving to London in 2010 to pursue a Master of Research degree in psychology, she was plagued by anxiety—throat-constricting, heartracing panic attacks that left her feeling like the world was collapsing. It took months to learn how to cope. She started with stillness, slowing the breath and

focusing on one thing, not many. Then, for a longer-term fix, she turned to movement. “My outlet was sports: running along the Thames, fitness classes, dancing. I tried everything,” Attar says. “When I didn’t train, I wouldn’t feel good. I’d feel lazy. When I’d start to train, I’d feel better, want to take care of myself more, eat better.”

After graduating, Attar looked for work in London, then in Lebanon, where her father lived, but the job hunt went on for more than a year. In 2013, she finally found work back in her hometown of Riyadh, providing therapy for brain injury patients. But then she had another challenge. In Saudi, women like Attar had few outlets. The few existing fitness options that allowed women were mostly poorly equipped gyms connected to beauty salons. An Arab woman jogging in public was unusual enough to draw comments. So was simply being outdoors without a long black covering, called an abaya. But she knew she had to move. So she got the idea to offer her female colleagues dance lessons after work. It was a scary prospect at first. But taking that step “changed my career and, later down the line, my life,” she now realizes.

As the classes became more popular, she began traveling around the city, to embassies and other private venues, teaching dance underground. Her mother and stepfather suggested another intimidating idea: opening her own

Before becoming a sports figure, Attar experienced anxiety and panic attacks. For her, “movement is medicine.”“I’ve learned there are plenty of opportunities through challenges.”

In the fall of 2021, Attar announced a plan to climb K2. At that point, only about 400 people had summited the “savage mountain.”

To amp up her training, Attar enlisted Mike McCastle, the coach who trained explorer Colin O’Brady for his unsupported trek across Antarctica.

studio. This was 2017, and it was a risk. That year, a 14-year-old boy was detained after doing the “Macarena” on a city street. There was no clear path to get a business license. Some conservative elements couldn’t accept the idea of women doing anything athletic. There could be trouble if she was discovered. She wasn’t even sure if she was a good-enough dancer. “I did one thing consistently right,” she said in a TEDx talk. “Regardless how it looked, I took that imperfect step forward.”

She named the studio Move. Open only to women and girls, it offered everything from Afrobeat to belly dancing and hip-hop. But learning dance steps was only part of the appeal. Women would arrive early just to bask in the warm, supportive environment. Girls would bring their moms, who would hang around to watch, learn and socialize.

On the side, Attar was organizing other activities for the larger community, too, like hikes and running events— anything to get women moving.

“There are infinite possibilities,” she says. “Basketball, dance, playing with your kids. Movement is such a big umbrella. You have to go and try and see what works for you. Unconsciously you’ll start to build.”

She saw it in the twentysomethings who found confidence through movement. She saw it in the conservative moms who took up belly dancing at Move. “It was like a party, really,” Attar says of the scene. Students became “a tribe, a community. Their whole emotional wellbeing changed.”

She remembers one teenage girl who was so shy when she walked through Move’s door, she could barely speak. Through YouTube, the teen had learned some dance moves and had convinced her skeptical mother to allow real lessons. At her first class, a one-on-one with teacher Noura Al-Abdulaziz, the girl was shaking. All she could do was nod and try to follow the steps.

Al-Abdulaziz understood. She had once suffered a paralyzing depression, but “I started communicating with people through my body, through dancing, not saying one word,” she says. “That’s how

I got healed.” Now, she watched her struggling student do the same. “She found her own style, her own personality,” Al-Abdulaziz recalls of the teen. Now a creative director, dance teacher and choreographer working all over the country, Al-Abdulaziz says, “Move started the idea that dance is something fundamental that we need here in Saudi. I feel like I’m truly healing the Saudi people through dance.”

Only those who risk going far can find out how far they can go.”

It was something Attar’s father, Mohamed, said often. When she was younger, he took her on hikes, which wasn’t common in her region, but he loved exploring the outdoors. “We’d come across a beetle, and he’d tell me about the beetle,” she recalls. “He opened my eyes to nature.” When she was 17, he took her to Africa, where they climbed Mount Kenya. They didn’t summit but a seed was planted. Climbing, Attar comes alive.

“She just blossoms,” her sister Rasha Attar Elsolh says. “She looks her best, feels her best, does her best. She’s meant to be on a mountain.”

Mohamed Attar wasn’t just her father. He was her best friend. They spoke by phone multiple times each day, and his words became a fuel behind her climbing, encouraging her to tackle harder and harder challenges.

After Mount Kenya, Attar ticked off more peaks: Kilimanjaro, Elbrus, Aconcagua, Island Peak. Still, the first time someone suggested Mount Everest, Attar thought it was absurd. How do you train for the world’s tallest mountain in the desert? Then she thought about her father, how he encouraged her to push her limits. She thought about how moving through challenges is what makes you stronger. Then she took a breath and took that imperfect step forward.

Training for an arduous climb is never easy, but in Saudi Arabia, there are extra challenges. Because there aren’t snowand ice-covered peaks, she ran intervals on sand dunes. To build strength, she dragged tires through the streets. To avoid the desert heat, she began her

“Movement is such a big umbrella. You have to try and see what works for you. Unconsciously, you start to build.”

workouts at 3 a.m. To avoid attracting attention from the moral police, she jogged in her black abaya. Finding the highest elevation gain in Riyadh (about 500 feet), she trudged up and down for hours at a time. Her training drew some stares. But it also had a hidden benefit. “People have said to me, ‘That’s how you’re so strong mentally.’ ”

In 2019, as Attar’s group, which included other Arab women climbers, plus trained guides and Sherpas, made their way from one high-altitude camp on Everest to the next, she’d listen to encouraging voice messages from her

Attar proudly displays the Lebanese flag from the top of K2.

father. After spending two months on the mountain, they reached the summit.

Not long after, she suffered a series of personal losses. First, the pandemic, which wound up crippling Move (though she has hopes to reopen one day). Then in October 2020, Mohamed Attar died of COVID. In one fell swoop it felt like she had not only lost her father but also her way forward.

“I felt my heart was open and it was leaking, a fountain I couldn’t close,” she recalls. She couldn’t eat, couldn’t sleep. Seeing friends, dancing, training . . it all felt impossible. And yet she knew what she had to do: move.

In the fall of 2021, Attar announced a plan to climb K2 the following summer. It was a dangerous goal, as only about 400 people in history had ever summited to that point. Statistics showed that one climber died for every four who managed to stand on top. So she amped up her training routine, enlisting Mike McCastle, the U.S.-based coach who trained explorer Colin O’Brady for his unsupported trek across Antarctica. “He’s a brilliant coach,” she says, lauding the creative ways he found to push her limits, which not only built strength but unearthed weaknesses.

By this time Saudi Arabia was changing, too. The government was pushing Vision 2030, a modernization plan. In 2016, it had established a women’s branch of its sports authority. The government also agreed to license female gyms, a reaction, in part, to alarming obesity statistics. In 2017, live music was no longer prohibited. In 2018, women were given the right to drive and to attend certain sporting events. In March 2022, Riyadh had its first official marathon, where men and women ran together. Many more women were going without the black abayas that impeded physical activity. The government even began sanctioning concerts where men and women danced together.

“I didn’t think all this could be happening so quickly,” Attar says. “It’s just amazing, so surreal. The country changed, and we were part of that change.”

Attar also was becoming more widely known. Several publications had written about her. Strangers started recognizing her at running events. She had been tapped to be the first trainer in Saudi’s Nike Training Club. The Saudi Sports for All Federation appointed Attar as an official ambassador. The government had partnered with Move and Attar to provide a free boot-camp program as a public heath measure, and also to teach dance classes to schoolkids. She had tens of thousands of followers on social media.

And yet, when she sought companies to sponsor her K2 climb—a typical step for an athlete like Attar—she couldn’t get much traction. Though she had spent almost all her life in Saudi, she was a Lebanese national, which made Saudi brands less receptive. It also became clear local companies still weren’t quite sure what to do with a female fitness icon.

“I’ve had brands tell me they can’t work with me because I am Lebanese .

because I dance too much . . . because I’m a woman, yet I don’t dress ‘feminine’ enough . . . because I have too many passion activities . . because I can’t fit in a box . . .” she posted on Instagram.

Looking for sponsors was exhausting. But she remembered how her father had taught her to keep moving forward. So Attar drained her bank account and made the plan anyway. Right before her departure for Pakistan, a gourmet driedfruit brand, Bateel, agreed to support part of the cost of her K2 trip. Incongruous, perhaps, but her spirits were buoyed. “That’s why you should never give up,” she says. Not long after that she found another partial sponsor, digital media brand Yes Theory.

As she began the seven-day trek from the village of Askole to the base of the mountain, she thought about the thousands of women and girls she had supported through dance and fitness,

and how they, in turn, were supporting her. She thought about her family back home cheering her on. “I have a whole tribe of people climbing with me,” she realized. When the climbing team spent a brutal two weeks hunkered down at camp waiting out a storm, she danced away the stress and boredom, infusing strangers’ tents with her buoyant energy, even as she understood the treacherous journey ahead. Looking at the sheer amount of snow and ice above, she knew trusted guides would show the way. She also knew she’d have to take every step to the top herself.

Sometime after 10 p.m. on July 21 they began their summit push in pitchblack darkness. All the training was paying off: her legs, and her lungs, were up to the task. But as her headlamp glared against a forbidding wall of ice, she faltered. Training in Saudi, there was no way to master ice climbing, yet here

she was facing an ice wall on the world’s most dangerous mountain. Struggling for purchase on the wall with her crampons, she slipped again and again, at one point swinging perilously from the wall on her rope. Suddenly, she was engulfed in a feeling she hadn’t had in years. Heart-racing, throat-closing panic, as if the world would end. Breathe, she told herself. Focus. Filter everything else out. “I’ve already been through grief, the worst thing in the world,” she realized. When her heart slowed, she kicked her right crampon into the ice and made a move. She kicked in her left and made another. Around 3:30 a.m., she cried as she reached the top.

And when the team returned to camp—around 10 hours after starting— everyone danced.

“I’m Nelly Attar,” she likes to say. “And I move for a living.”

In high school, Native American Ku Stevens became the fastest longdistance runner in the state of Nevada. But he doesn’t run for fame or personal glory. He runs to honor his ancestors and put a spotlight on a dark history that deserves examination.

Words BILL DONAHUE Photography

Distance runner Ku Stevens grew up in a small house on a potholed street on a tiny Indian reservation in Yerington, Nevada, a cowboy town of 3,200 where the main drag still feels very Old West, boasting a Rexall Drug, a steakhouse and a dusty museum honoring local war veterans.

On Ku’s street, the yards were piled high with the tailings from the nearby Anaconda copper mine, so that the soil was too poisoned to sustain much vegetation. When he was in fifth grade, Ku and his friends terrorized their neighbors, playing doorbell ditch and lighting off fireworks. Was petty thuggery his destiny? Possibly. “When you’re a Native American kid,” says Ku, an Indigenous Paiute who recently turned 19, “you’re taught to lose. You’re taught to look at bloody moments in history where your people got killed and think, ‘That could have been me.’ ”

One hot July night during Ku’s mischievous phase, the Yerington police heard exploding firecrackers in the neighborhood. When Ku arrived home after midnight, there were two cruisers waiting for him in the driveway. He says his mother grounded him for the rest of the summer.

Sequestered in his bedroom, Ku had time to think. He recognized the racial pain he felt, living in a town where white kids threw slurs at Native Americans and where he’d been socially pressured, in fourth grade, into cutting off his long black hair. He also thought about how sometimes he’d felt deeply rooted, being Native. He remembered sitting in his family’s sweat lodge. He remembered foraging the high desert for buckberries and pine nuts with his father, Delmar, and watching his dad take part in a sundance. Several times, Delmar fasted and went without water for four straight days, all the while dancing barefoot on the hot desert ground. He prayed, as Ku puts it, “for his people, for their health and well-being.”

That summer, Ku told himself, “I’m never going to hang out with those kids again. I can be somebody.”

It was a sober decision for a 10-yearold to make but also characteristic of Ku. “He’s always been focused,” says his mother, Misty Stevens. “Even when he was in elementary school, he was serious about homework. I think it’s because he saw the neighbor down the street passed out with a bunch of empty bottles around him.”

Ku refused to go down that road, for he had an athletic gift and also a staggering dedication to running. For two years in high school, Ku didn’t have a coach. Or any teammates. The sole runner for Yerington, he ran alone on long, straight desert roads. Then in 2022, Ku broke the Nevada state record for the 3,200-meter run, clocking in at 8:54.83.

As he grew stronger, he also grew his hair long again. He began, as well, to think about racial justice, in part because when he was in eighth grade, two Black stepsisters at Yerington High, his friends Taylissa Marriott and Jayla Tolliver, were racially harassed at school—and then so ignored by administrators when they complained that they won a $160,000 settlement against the Lyon County School District. “There are blind racists out there,” Ku thought, “people who don’t even realize that this country was built on the blood and bones of my ancestors, and on misogyny and racism and slavery.”

In May 2021, Ku learned that 215 unmarked graves of Indigenous children had just been discovered on the campus of an Indian boarding school in Canada. He knew then that it was time for him to speak out. With both his voice and his legs. Helped by his parents, he began organizing a singular athletic event to remember— and also expose—a dark passage in American history.

It’s a chilly morning in August 2022. The sky is still dark, and 30 or so runners and walkers, many of them Native American, are gathered in Yerington, on a grassy lawn near Ku’s home, to spend the next two days hoofing some 50 miles west through the Carson Desert.

As part of the second annual Remembrance Run, hosted by Ku and his parents, Delmar and Misty, the group gathered here will journey to the now-shuttered Stewart Indian School, where, from 1890 to the 1960s, Native

American kids as young as 4 boarded year-round, forcibly removed from their parents, abused, beaten, belittled and forbidden to speak their native languages. Stewart was, like so many of the 400plus Indian boarding schools that once scattered the U.S., a K-12 facility with a graveyard on campus.

The runners are traveling in reverse the very route that one Stewart student— Ku’s great-grandfather, Frank Quinn—is believed to have taken to escape the school in the early 1900s, when he was about 8 years old. They’re making this

journey at a critical moment: Last May, the U.S. Department of the Interior released a report estimating that “thousands or tens of thousands” of Native children died at these boarding schools. Congresswoman Sharice Davids, a Kansas Democrat, is now pushing a bill that would establish a Truth and Healing Commission on Indian boarding schools. And last summer, Pope Francis toured Canada apologizing for the Catholic Church’s administration of many such schools and admitting the church was complicit in “genocide.”

“We’re not trying to make you feel bad about what your ancestors might have done,” Ku says, explaining the run’s purpose. “We’re just letting you know why Native Americans suffer such immense historical trauma.” His words are considered, his manner

“We’re just letting you know why Native Americans suffer such immense historical trauma.”

solemn. He exudes confidence and responsibility, and sometimes it’s hard to remember that he’s still a teenager. During one interview at his house, Ku decided, on his own initiative, to spend the afternoon weeding his family’s gravel driveway. He wielded a rake in the bone-dry 95-degree heat as he explained how Donald Trump is simply an heir to the racism underlying the 19th-century ravaging of Indigenous America.

At sunrise, we gather in a circle and Paiute/Shoshone shaman Russell Abel, once a meth addict, now a fit, chiseled runner, prays for “every step we take.” He prays, as well, for Ku, “who brought us together.” Soon, another spiritual leader wanders among us, ritually smudging each participant, burning sage in a seashell, then guiding the smoke toward our torsos and legs by

waving an eagle feather up and down. As Ku is smudged, he shakes out his legs, colt-like, loose; warming up, staying silent. He is intent, it seems, on imbibing all of the hope and the history contained in the smoke.

Then a moment later he is running, a gracefully lean young man with long black hair that sways with each footfall. Along with three other gazelle-thin harriers—32-year-old Lupe Cabada, who’s coached Ku part-time since 2020, and two top-tier Nevada high schoolers—he’s running at what for him is a snail’s pace, seven minutes a mile. At this pace, he can chat about girls, about his love for playing Super Smash Bros. on his Nintendo Switch, or about his 2001 BMW 330 Ci, which he wrecked by hitting a pole a few months ago. He can crack inside jokes with his running cronies, but that’s not really his style. There’s a cool, composed air to Ku, and now, as he stares off into the vast blue Nevada sky, he looks like a very different person from that kid who played games of doorbell ditch in 2015.

These days, Ku is a movie star, too. For a year now, a film crew has been documenting his life—his races, his graduation, the minor tiffs with his parents—as they make a full-length nonfiction film zeroing in on the Remembrance Run. Director/producer Paige Bethmann, a 28-year-old Indigenous Haudenosaunee from upstate New York, moved to Reno for the project because she was taken with the story of “a young person running 50 miles across the desert to honor his ancestors. He’s so articulate. He’s so positive.”

Ku is also a political operative. As he lopes west, Nevada’s governor, Steve Sisolak, is planning to meet him at the Stewart School to address the boarding school issue. Catherine Cortez Masto, a U.S. Senator representing Nevada, will be there too, as will Billy Mills, a Lakota runner who won the 10,000-meter race at the 1964 Olympics before becoming the eloquent leader of Running Strong for American Indian Youth, which funded this year’s Remembrance Run with a $10,000 Dreamstarter Award.

Will Ku become the next Billy Mills? It could happen. A month after this run, he’ll start his freshman year at the University of Oregon, becoming one of the first Native American harriers to join the nation’s most storied track program. U of O is where Nike founder Phil Knight made the world’s first waffle-soled shoes, and where ’70s-era phenom Steve Prefontaine became distance running’s icon of grit, gutting barrel-chested through 1,500- and 5,000-meter races as he minted brawny aphorisms such as “To give anything less than your best is to sacrifice the gift.”

As Ku turns left onto a gravel road, I think to myself: Who here isn’t rooting for this kid to shine? Hailing from a reservation afflicted by drug addiction and rampant suicide, he is a symbol of hope. It’s Ku’s picture that’s emblazoned

across all the T-shirts for this second annual Remembrance Run, and it’s Ku who is posing with a ceremonial wooden staff in all the newspaper stories about the run. It’s unlikely this journey would even have happened were it not for his star power, and as the sun climbs in the sky and the desert becomes a scorching, treeless oven, to a person, every single runner cites Ku as their inspiration.

“A lot of people think all Native Americans are dead,” Amber Torres, the chair of the Walker River Paiute, tells me as she jogs along, “or that we’re just angry or that we’re drunks. In using his very powerful voice to focus on the boarding school issue, Ku’s showing people why we’re angry and why we’re bitter. He’s also showing people that we’re still here—and that we can overcome hardship.”