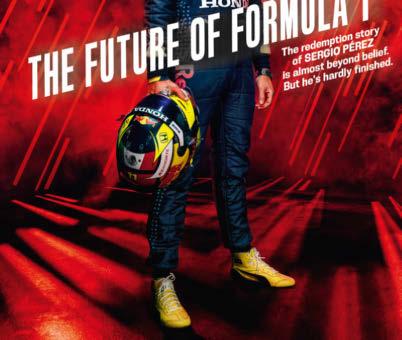

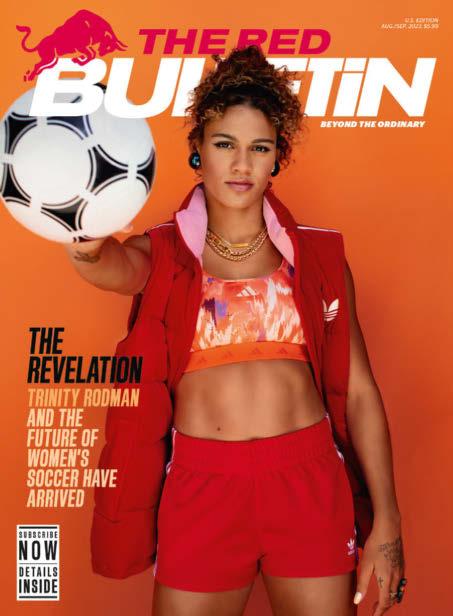

THE REVELATION

THE REVELATION

Serious traders approach trading with the instincts of a sportsperson - strategy combined with speed and decisive thinking. That’s why OANDA’s high-performance trading platforms and award-winning* tools help you trade smarter.

oanda.com

Why do we love sports? Passionate fans know the answer is deeper than highlight clips or the final numbers on a scoreboard. They’re drawn to the human drama that invariably plays out as committed athletes strive, amid genuine struggles, to fulfill their dreams and potential. That’s certainly the case with our cover story—a deep dive on soccer star Trinity Rodman. She plays the game with a remarkable mixture of joy, artistry and tenacity— qualities that reflect her life experiences and the manner in which she is successfully authoring her own story.

This issue explores the human side of sports. There’s an essay by former world champion mountain biker Kate Courtney on her quest to reclaim confidence. Supercross racer turned freerider Tyler Beremen shares his dream of a competition where creativity is king. And Wout van Aert, a versatile cycling champ, explains how he breaks barriers (by refusing to accept them). All of them, like many of us, know sports offer a path to our best selves.

WOLFGANG ZAC

The photographer, who splits his time between Berlin and Los Angeles and shot our cover story on Trinity Rodman, got directly in the line of fire to capture the soccer star striking the ball. He was lucky to escape with only a shattered lens filter and a bruise under his eye. Zac is booked worldwide for fashion and lifestyle shoots for brands like Adidas and Vanity Fair Page 22

The L.A.-based photographer, who loves to capture street and beach culture, shot Emelia Hartford—a custom car builder, actress and content creator.

“The best way to photograph Emelia screaming around turns on Angeles Crest Highway was on the back of a motorcycle,” she says. “It was a perfect equation for excitement.” Zumbrun’s clients include Glamour, Harley-Davidson and Triumph. Page 60

THE MOST CAPABLE RARELY GO IT ALONE.

THE MOST CAPABLE RARELY GO IT ALONE.

THE MOST CAPABLE RARELY GO IT ALONE.

August/September

22 Tenacity and Joy

The future of women’s soccer has arrived. She’s a prolific and creative talent—and her name is Trinity Rodman.

36 Field of Dreams

Freerider Tyler Bereman and builder Jason Baker are perfecting a dirt bike course beyond your wildest imagination.

44 Tour de Force

Belgian pro cyclist Wout van Aert loves to push himself to— and beyond—the limit.

54 Digging Deep

In her own words, pro mountain biker Kate Courtney describes how she learned to confront her fears and demystify obstacles.

Custom car builder, content creator and budding actress Emelia Hartford has found serenity—at very high speed.

72 The Spirit of Defiance

An all-women skate crew in Bolivia finds self-expression while wearing traditional Indigenous garb.

At 21, Trinity Rodman has the skills, artistry and grit to make her one of the most promising young stars in women’s soccer.

CLOUD RIDERS

Is this heaven? No, it’s Kansas. At Red Bull Imagination, freerider Tyler Bereman is making his dreams come true.

60

SURE AS FATE

In the new film Gran Turismo, Emelia Hartford plays a race car driver—a role the car builder was born to play.

Taking You to New Heights

9 How the Sushi Dragon makes the content of the future

12 Bright idea: a bar dedicated to women’s sports

14 Scaling walls in Idaho

16 Skating in South Africa

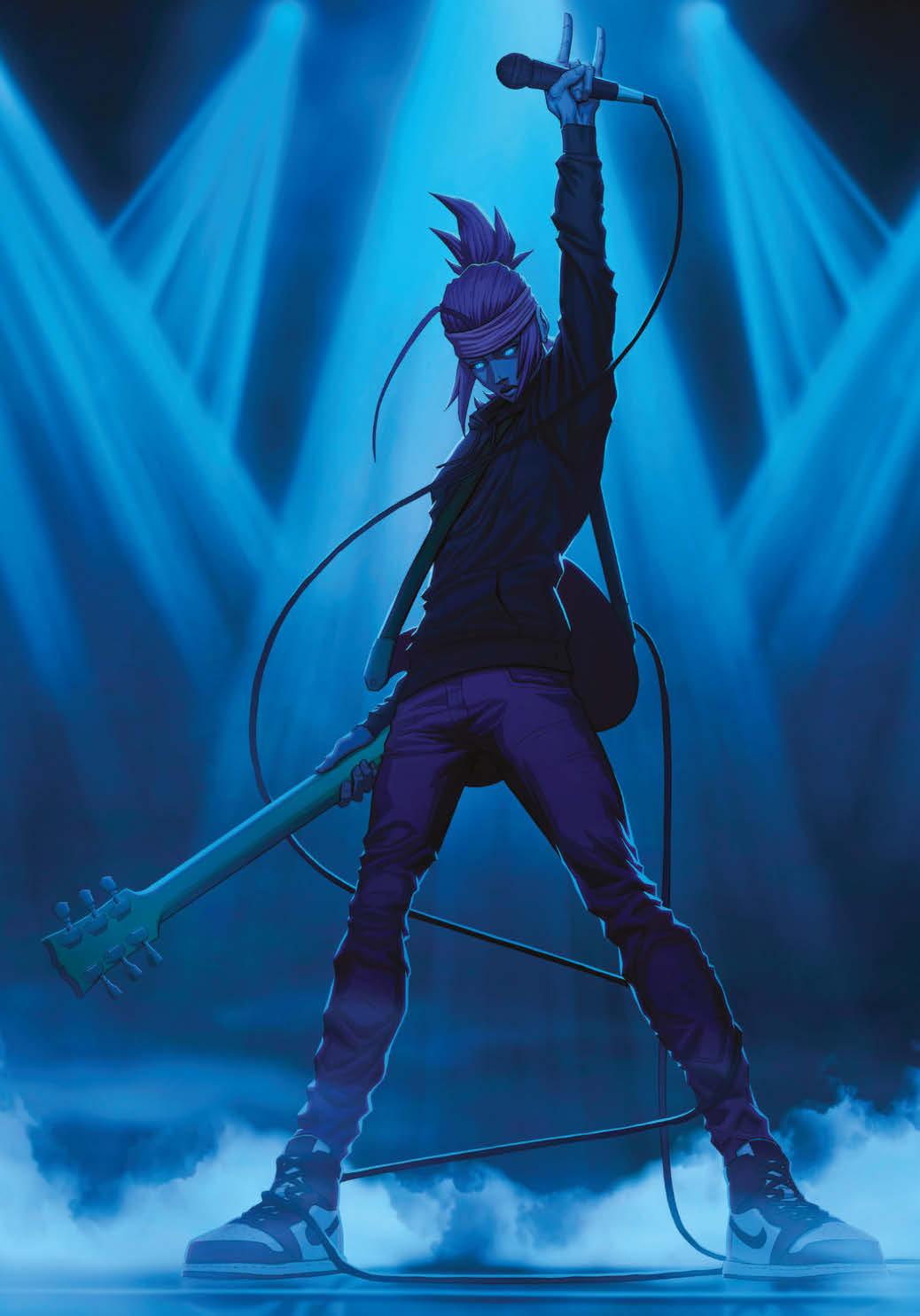

18 Meet Teflon Sega, a 2D anime singer

20 Albert Hammond Jr. shares some of his top tunes

Get it. Do it. See it.

81 Travel: Five off-road biking destinations to explore

84 Fitness tips from ultrarunner David Kilgore

86 Dates for your calendar

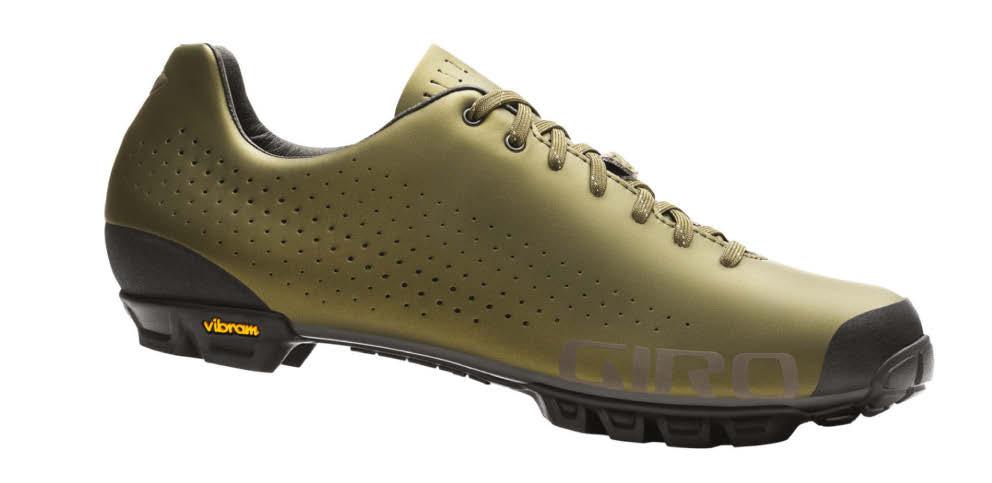

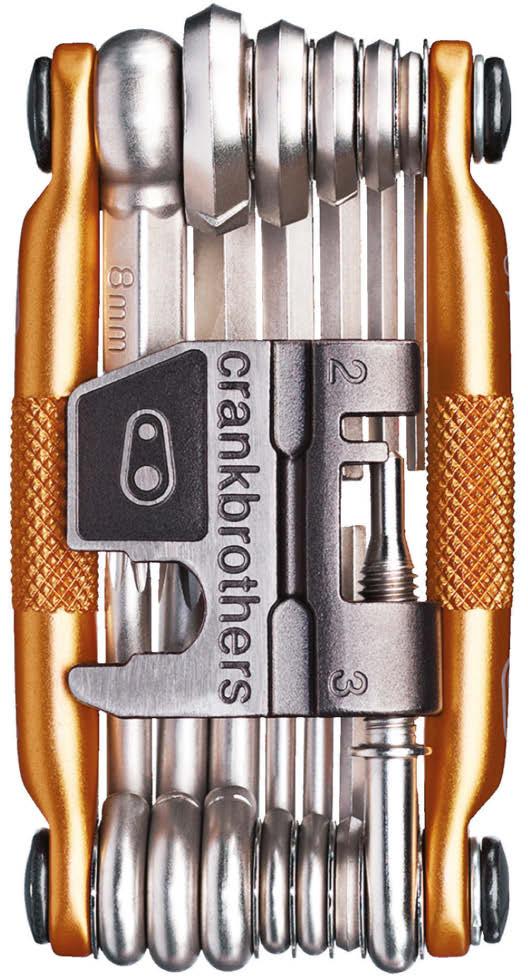

88 The best new bike gear

96 The Red Bulletin worldwide

98 Holding court in Italy

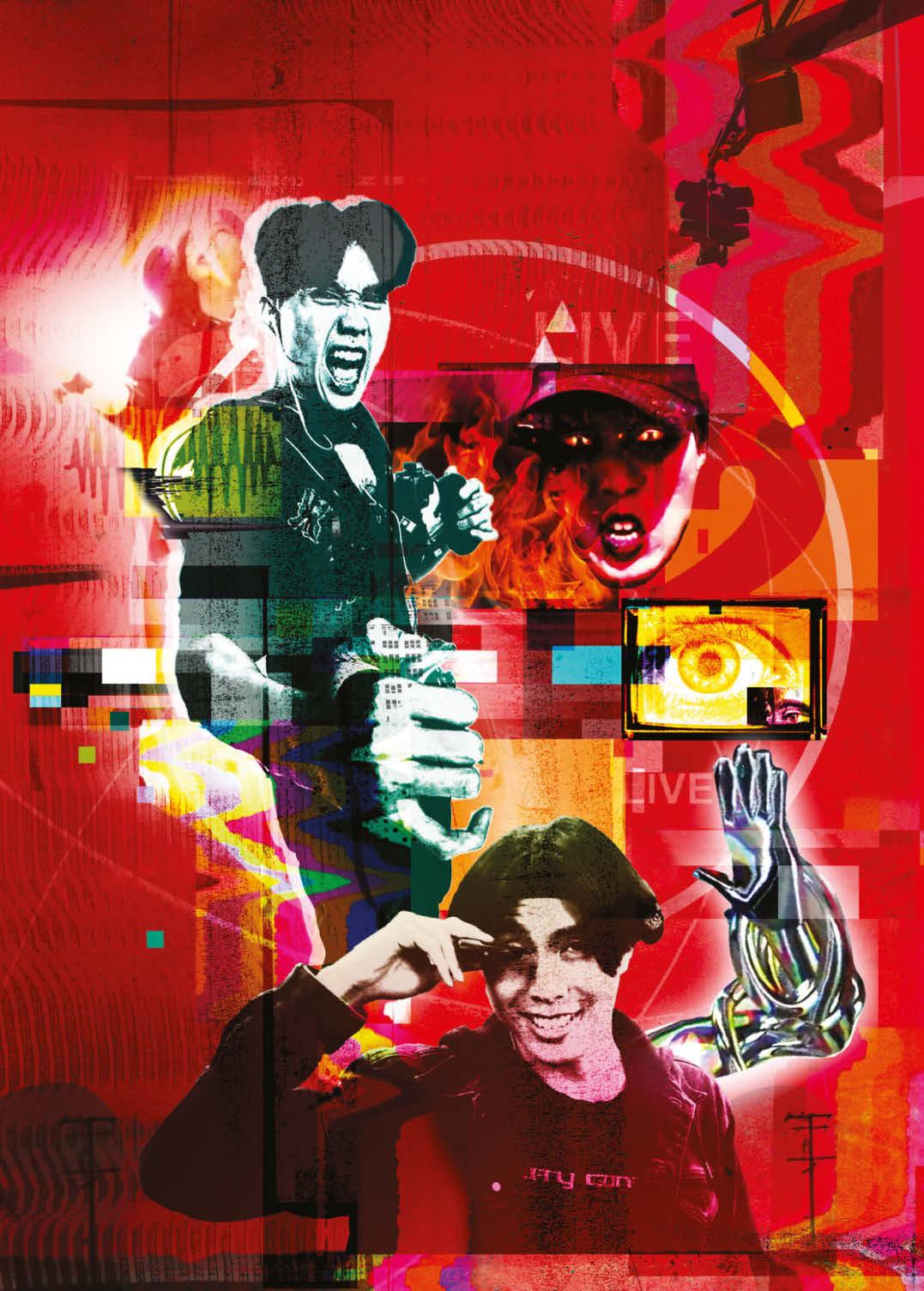

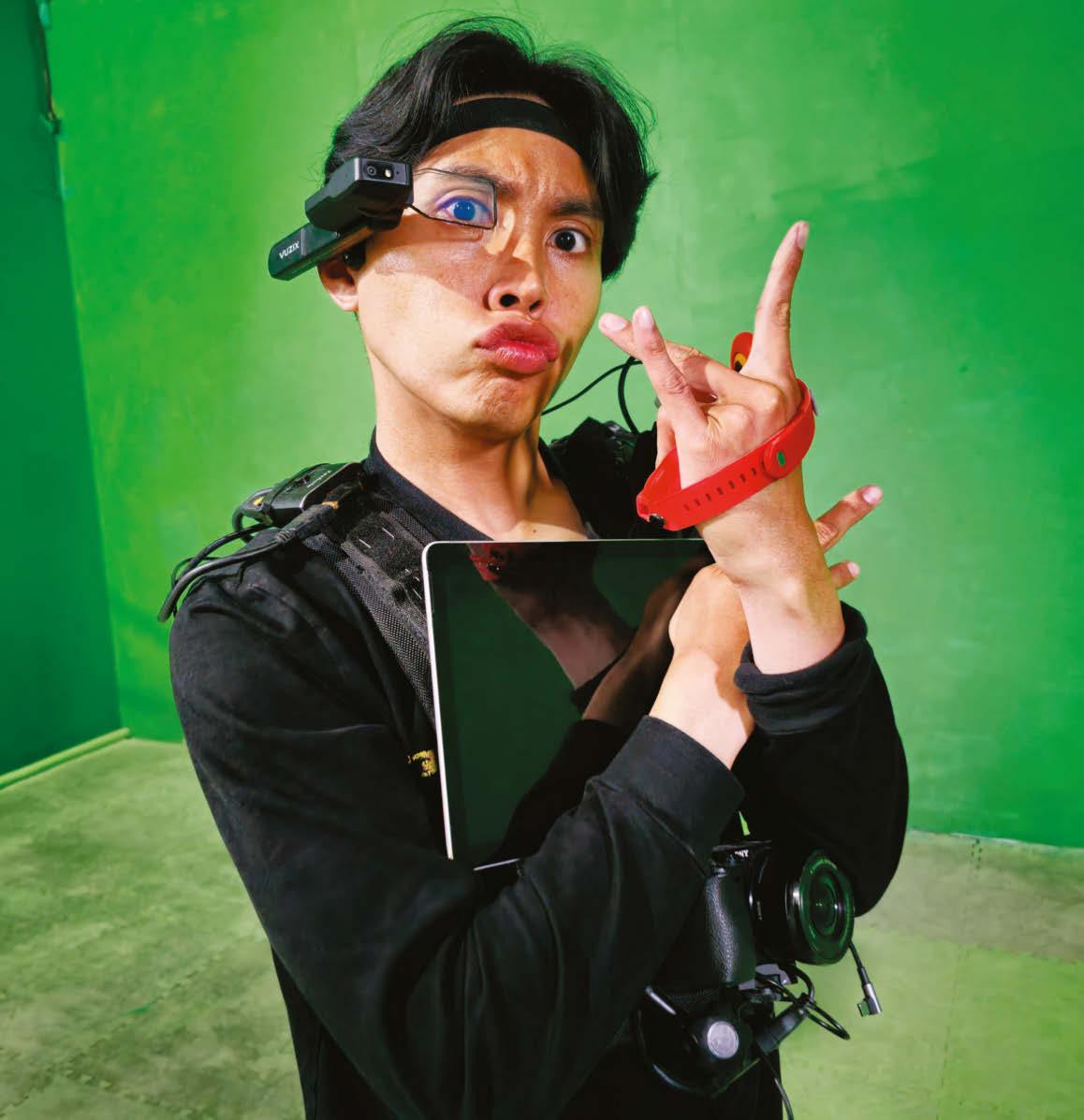

Content creator Stefan Li, aka the Sushi Dragon, is revolutionizing livestreaming with his innovative use of consumer tech.

Words NORA O’DONNELL

In a sea of Twitch creators, where viewers can watch everything from pro gamers to scantily clad women making pancakes, there’s one feed that’s aiming to redefine what it means to livestream. Whether he’s broadcasting from an 8,000-square-foot warehouse in Montana or out in the field, Stefan Li uses the latest in consumer technology to create augmented realities in real time. He effectively acts like a conductor who can trigger effects that alter his facial expressions, his voice and his environment without any need for a film crew or a postproduction team.

“I’m essentially building a video game based on real life,” says the 31-year-old Li, who’s known to his nearly 300,000 followers on Twitch as the Sushi Dragon. On his streams, which can run for hours, there’s the casual audience interaction that’s become a staple on Twitch channels, but what sets Li apart is his use of technology. With a small AR monitor covering his right eye, a computer strapped to his body and a one-handed keyboard controller, Li can produce a multicamera oneman show that uses the same filter technology that’s available on Snapchat or Zoom. When everything works in harmony, Li can layer voice and face effects not only on himself but those around him. “I call that the perfect flow,” Li says.

Li’s journey to that technological flow state has taken years to develop.

Growing up in Hawaii, Li wasn’t overly obsessed with gadgets. “I was like every kid growing up in the ’90s, consuming pop culture and video games,” he says. “I wasn’t a productive kid at all.”

Li was a restless child who found sitting in classrooms for hours to be absolute torture.

“I felt trapped by society’s expectations, and I think that’s because this road isn’t built for people with ADHD,” Lee explains. After graduating high school in 2009, he moved to Los Angeles to study biology in college and complete premed coursework, but his heart wasn’t in it and he eventually dropped out. What he did love was filming videos where he could explore his creativity, and when he met another creator who was putting his content on YouTube, something clicked. “Oh, right! This is what I want to do,” Li says.

In those early days, Li started creating videos from a closet in an L.A. apartment he shared with roommates. At the time, when YouTube was still young, the platform rewarded creativity, so Li would spend days filming whatever wacky idea came into his head. Some of those ideas went viral, including one where he surprised users on ChatRoulette with a homegrown re-creation of the music video “Gangnam Style.” Unfortunately, it didn’t last. As YouTube evolved, success on the platform became more formulaic, and Li wasn’t interested in confining his creativity to whatever the algorithm would reward. So, he abandoned content-making for four years and picked up jobs at places like Best Buy to make ends meet.

Then Twitch exploded. As the livestreaming service grew, Li realized he could use the platform to edit his own live show. “Twitch reignited a creative passion because you could see the feedback of your editing in real time,” he says. “The stakes felt higher because it was live. It started triggering every magical sense in my brain, and being able to live edit was hitting all the cues of my ADD.”

Li also started building his own PCs around this time, and he realized his vision of creating a one-man live show with visual effects was within his grasp. His setup became more and more elaborate, as he moved from his closet into his bedroom—and eventually into a garage in Sacramento, where the rent was more affordable. Each time he moved, he had to rewire his setup, which at this point included multiple PCs, at least 20 webcams, and green screens he found on Craigslist.

As interest in Li’s channel increased, he started getting “raided,” which is when a streamer sends viewers to another channel, but his stitched-together tech couldn’t handle a massive influx of people, so his stream kept crashing. “My setup just kept on breaking, kept on melting, kept on burning,” Li says.

Li, however, was determined to work through his technical difficulties. He told himself, I’m going to keep figuring this out, and learn it through. And then he got really good at it. He moved back to L.A. for a stint, but a few years ago he moved to Montana, which is where he currently keeps his setup in a warehouse. At the warehouse, he’s constantly tinkering and rebuilding his setup. “I was forced to learn how to be efficient, and that rebuilding led to the discovery of portability,” he says.

These days, thanks to years of experience and newer tech, Li can take his setup on the road with just a couple of laptops, and that portability comes in handy when he’s traveling to L.A. for his newest job as host of Red Bull New Game, a game show that’s available on the YouTube channel Red Bull LFG. Using AR technology, the set is projected on green screens,

and Li can manipulate not only the set but the faces and voices of the contestants.

“The show is more ambitious because it’s multiplying my tech times four, where the guests can also hear and change their voice,” Li says.

Li runs the controls, but on Red Bull New Game, he has technical help. If something

goes wrong with the audio or video, he has people on hand who can troubleshoot for him.

“That’s the thing about having a team,” he says. “It frees up a lot of my technical weight so I can be more creative and bring my world to other people.”

But in the end, Li’s biggest goal is simply to make his own art through the process of

live editing, whatever the environment. “When I do a great livestream, it’s not about how many viewers I get,” he says. “It’s about how everything flows so naturally, and it was done by my one brain. It’s magical to see everything flow so organically because you can’t predict what’s going to happen next.”

At his warehouse in Montana, Li has 8,000 square feet to produce his one-man show, but he’s increasingly finding ways to take his live editing on the road with just a van and a couple of laptops.

“IT’S MAGICAL TO SEE EVERYTHING FLOW ORGANICALLY.”

Frustrated by the lack of options to watch women’s sports while out drinking with friends, Jenny Nguyen decided to do something about it.

On a weeknight in April 2018, Jenny Nguyen went to a sports bar with friends to watch Notre Dame play Mississippi State in the final game of that season’s NCAA women’s basketball tournament. It was the only championship game being aired that night, but none of the 32 screens in the bar was showing it. Nguyen’s sizable group asked to see it and were given one TV in the back of the bar. They ordered food,

drank beers and witnessed one of the greatest finishes in NCAA history, with the team from Indiana hitting a lastsecond 3-pointer to clinch the title.

“I remember throwing my hat across the bar as we all screamed and lost it,” Nguyen says. “That’s when we realized no one else in the bar knew why we were cheering. We had watched the entire game with the sound turned off by the bar. We hadn’t even questioned it.”

Years of experiences just like this inspired the 43-yearold to launch the Sports Bra. The bar in Portland, Oregon, is dedicated to showing women’s sports in a space that “supports, empowers and promotes girls and women in sports and in the community.” Unbelievably, it’s the first of its kind in the world.

Nguyen, a medical school graduate who spent years working in the restaurant industry—three of them as executive chef at a Portland college—was looking for a new direction when she hatched the idea for the Sports Bra. In February last year, she launched a Kickstarter to make it happen. The goal of $50,000 was soon surpassed; in the end, supporters across the world donated more than $105,000.

“I had never felt so certain of something before,” says Nguyen, who had played college basketball until an ACL injury forced her retirement. “I had this vision of what seeing more women’s sports would have meant to me when I was younger, and the impact it would have made on me. I felt like I had to make it a reality.”

Opened in April last year, the Sports Bra excludes no

one from coming through its doors; it simply gives women’s sports the space they don’t get in other sports bars. “The statistics are that 95 percent of all sports on TV and in the media are male, so this bar highlights the other 5 percent and tells the stories people never hear,” Nguyen says. “We’re not only talking about women but about all the other sports stories that don’t

get space: nonbinary athletes, trans athletes. A space like this is so important not just for women but for the intersectionalities of all those underrepresented folks.”

People now travel from all over the world to sit in the Sports Bra’s booths and watch a game, and Nguyen hopes to open similar bars in other states and countries.

“Every day, I see the impact

of what we’re doing,” she says. “In the first couple of months of being open, two little girls were here with their dad, and they couldn’t take their eyes off the sports on our TVs. As I walked by, the dad touched my arm and said, ‘Thank you for giving my daughters this place.’ That’s what this bar is. That’s what we’re doing here.”

thesportsbrapdx.com

“EVERY DAY, I SEE THE IMPACT OF WHAT WE’RE DOING.”

When the COVID-imposed lockdowns of early 2020 made self-isolation mandatory, people were crawling up the walls—in a literal sense at photographer Ben Herndon’s home in the Idaho Panhandle, which has a climbing setup in the garage. On his Instagram, Herndon acknowledged the importance of avoiding risky outdoor activities that might burden local emergency services. “The good news,” he observed, “is there are plenty of ways to get hurt from home!” benherndon.com; redbullillume.com

When Brazil’s Letícia Bufoni began skating at the age of 9, she was the only girl on a board in her São Paulo neighborhood. During her tour of South Africa in March of this year—“Letícia Pushes Mzansi”—the six-time X Games gold medalist, who became an American citizen in 2021, passed on her knowledge to the next generation via clinics and workshops. In between, she found time to ride at Cape Town’s stunning Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa, an appropriate venue to showcase her own unique artistry in motion. redbullcontentpool.com

Created as a means of outsmarting the music industry, this 2D anime singer is pushing the boundaries of artistry in the metaverse.

Teflon Sega isn’t like other R&B musicians. This much is obvious from his gravity-defying blackand-pink hair and his purple skin. But there’s another, bigger difference: He can only be seen in the metaverse. The 2D anime singer, who has almost half a million monthly listeners on Spotify, more than 21 million YouTube views and 5.6 million SoundCloud streams, is a real artist with a digital visage.

The invention of an anonymous musician and visual artist, Sega’s music and online presence show how the lines between the virtual and physical art worlds are no longer clearly defined. Sega, who achieved viral success in 2016 with his breakout single “Beretta Lake,” interacts with fans through online videos set in a purplehued dystopian world, as well as on social media and in virtual concerts. “My dream is to have a fully touring holographic augmented-reality live show,” he says. “That’s what I imagine when I close my eyes.”

the red bulletin: You just released your debut album, Welcome to the Mourning Show. How was the creative experience?

teflon sega: I’ve been releasing singles since 2016, but I hadn’t thought about doing a whole album until the past year. The experience is so different. With singles you can easily tell one story in a few minutes, whereas an album lets you show different sides to a story. This was a chance to explore and show my brighter and more uptempo sides.

Why did you decide to create music within the metaverse as the digital avatar Teflon Sega?

It’s been a long, weird journey. Years ago, I was signed and then shelved on a major label, and they wouldn’t let me off. First, I tried leaking music onto SoundCloud, but that didn’t work. I became depressed. I was in the worst period of my life because I couldn’t express myself creatively. So I created an avatar and started releasing music secretly behind it.

So it started as a loophole to get around a contract?

Yeah. The success was amazing —one song charted at number four on Spotify’s global viral chart—but I was still under contract. I didn’t know if the label was going to find out and sue me. They ended up dropping me, thankfully. Then they reached out to Teflon Sega, saying they were interested in signing him. Hilarious.

Did you consider dropping the avatar once you’d been released by the label? I did. In 2018, I told my audience that I was going to do a face review, and I announced a date. But I was flooded with messages saying the exact same thing: “Don’t do it, don’t ruin something special, don’t ruin this escape . . .” That changed everything. It made me realize this story was now bigger than me. My job now is to breathe as much life as I can into Teflon and this unique situation. I’ve unearthed an entire new passion, which is world-building and storytelling within music and the metaverse.

How did you learn the skills to create real-time animations? I have no background in 3D art, or in animation or technology. I learned everything on YouTube and found a few mentors online. I was obsessive, doing it for 15 hours a day, every day. It was a painful learning process, but within a few years I started feeling more confident. I put out a lot of cringey content and learned in front of my audience. I feel like I’m still learning.

Recently you posted a side-byside comparison of a motioncapture music video and the creative process behind the scenes. Why did you decide to show that now?

It’s something I’d wanted to do for a long time. Animation as an art form is more than 100 years old, but real-time animation and motion capture is so new, and it’s becoming accessible for creators in their homes, without studios or big budgets. People would send messages complimenting my “team” on their work. I wanted to show that I’m just making this stuff in my garage, and that you can do it, too.

Do you feel different as an artist because of your avatar? I do. It’s been beautiful. In the process of what you could call a gimmick, I’ve learned that avatars are just a new version of what’s always existed in art. History is full of anonymous creators; there’s a plethora of artists from the past who felt that by putting on a literal mask, they could remove a metaphorical one and express something that was a little risky or a little more real. When I started making music as an avatar, I was able to express sides of myself—my depression, my anxiety, some of my quirks— that even the people around me have never seen. My audience connected deeply with them, and it was freeing. I think that’s the experience of a lot of introverted artists. So avatars are going to become a big wave in the creation of art in the future.

Instagram: @teflonsega

“MY JOB NOW IS TO BREATHE AS MUCH LIFE AS I CAN INTO TEFLON.”

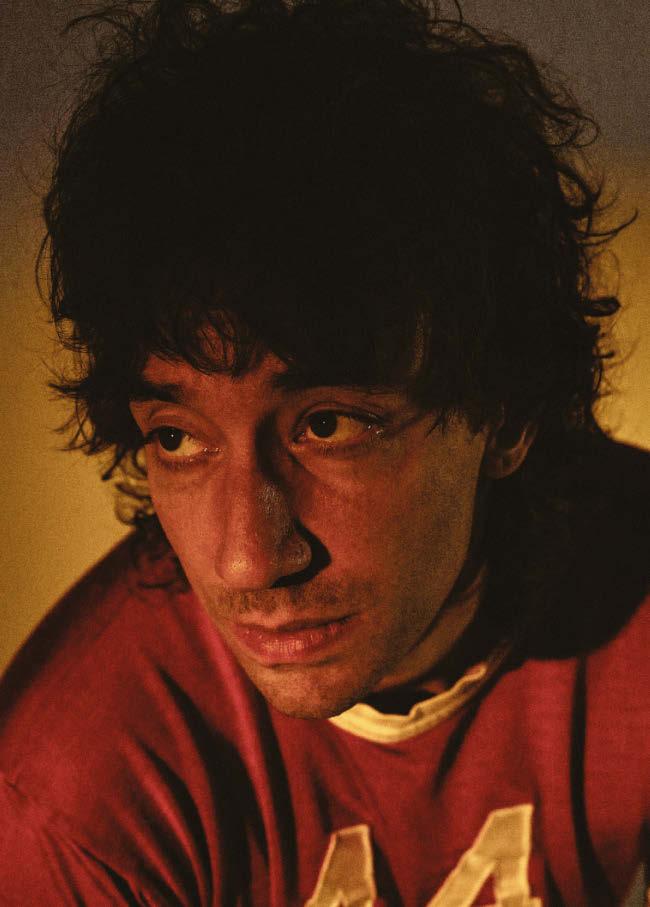

The Strokes guitarist and solo artist Albert Hammond Jr. reveals four tunes that give him a sense of clarity.

In April of this year, Albert Hammond Jr.—guitarist and singer-songwriter with Grammywinning New York City rockers the Strokes, and a solo artist since 2016—played a gig with the band in Minneapolis. After the show, they were listening to one of his playlists. First there was a track by minimalist composer Philip Glass, followed by Nick Lowe’s 1978 hit “I Love the Sound of Breaking Glass,” which prompted Strokes drummer Fabrizio Moretti to ask if there was an intentional theme. “I was like, ‘No, but I should keep this going—it seems like fun,’ ” recalls Hammond Jr., now 43. To mark the release of his fifth solo album, Melodies on Hiatus, here he does exactly that. Melodies on Hiatus is out now; redbullrecords.com

Scan the QR code to hear our Playlist podcast with Albert Hammond Jr. on Spotify.

NICK LOWE

“I LOVE THE SOUND OF BREAKING GLASS” (1978)

“While renovating my house, I stayed at this cool apartment building in L.A. where a lot of musicians stay. I became friends with the musician Joy Downer, and she had this on her playlist. I was like, ‘Wow, what is this?’ I love Nick Lowe, but I wasn’t aware of [this song]. It’s so cool when you discover a song you didn’t know by someone you like.”

BLONDIE

“HEART OF GLASS” (1978)

“In our early days, we got compared to some bands I didn’t really listen to until other people said it—[bands] like Blondie. Blondie are great, and it’s so cool to see them still playing. When you’re younger, you want to live fast, die young. Then you get older and realize it’s so exciting to keep creating and changing, and what you lose with age you gain in wisdom and ability.”

PHILIP GLASS

“STRING QUARTET NO. 3” (1985)

“I do sauna and ice baths with friends every Sunday. One time in the sauna, this came on, and even though I’m a huge Philip Glass fan, I didn’t know it. I fell in love with it instantly! I usually put it on every playlist now, because it cleanses the palate and it’s fun to listen to when you’re driving at night. It’s inspirational for creating, too, if you’re in a lull.”

“This is a song from [Strokes singer] Julian’s first solo record that I’ve always loved. He’s amazing at melody, even if I don’t know what he’s saying sometimes, the word combination with the melody always brings melancholy. He’s really good at hitting you with little things that reflect your life. So regardless of what he’s saying, you’re having thoughts about your own life.”

JULIAN CASABLANCAS “GLASS” (2009)

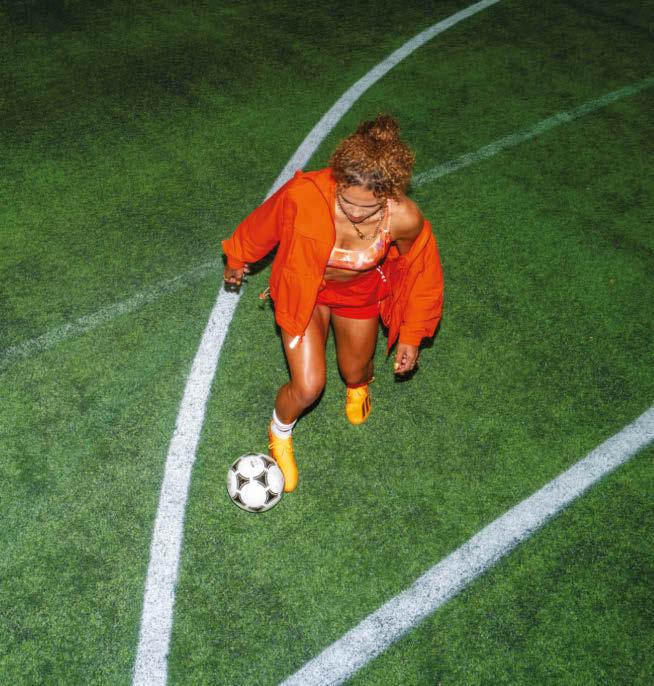

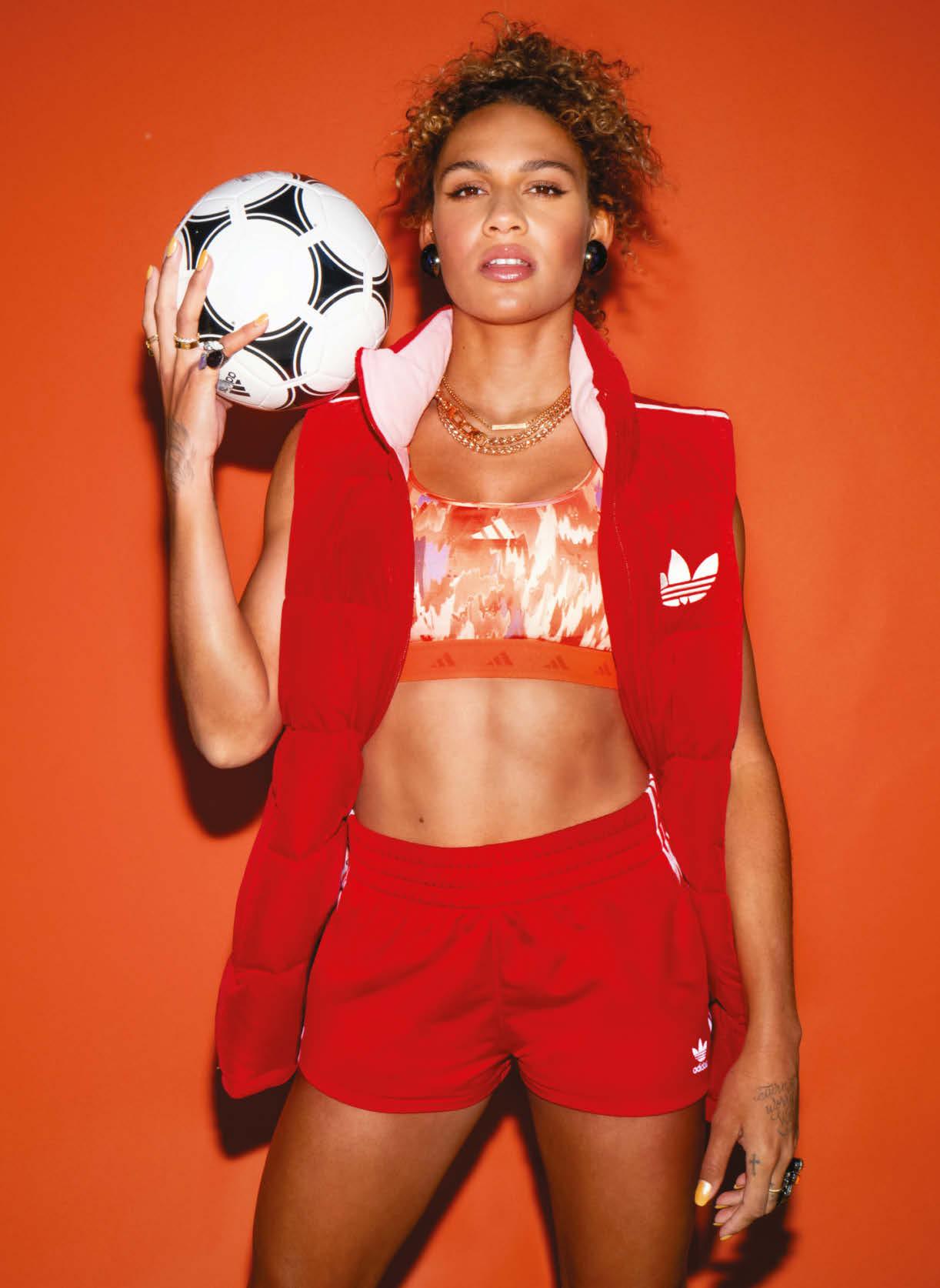

“I think my personality comes through in the way that I play,” says Rodman, who was photographed in Springfield, Virginia, on April 24.

The future of women’s soccer has arrived. Her name is Trinity Rodman.

Words PETER FLAX Photography WOLFGANG ZAC

It’s halftime in New Zealand. The U.S. women’s national team is officially beginning its 2023 World Cup campaign with a January contest against the co-hosts of that looming, allimportant tournament. Although the Americans dominated possession in the opening 45 minutes, the score remains 0-0. The U.S. coach, hoping to inject energy into the game and break the deadlock, begins the second half with four substitutions.

Trinity Rodman runs onto the field. Six minutes later, the young striker— she’s four months shy of turning 21 at the time—receives a perfect pass as she streaks toward the right corner. With a Kiwi defender tight to her left shoulder, enticing Rodman to drive toward the corner, the American instead abruptly cuts left and back, creating a momentary space. Rodman takes one touch with her right foot and lofts the ball into the box with her left as teammate Mallory Swanson sprints toward the goal. In about a second it goes from Rodman’s left foot to Swanson’s forehead to the back of the net.

About 20 minutes later, Rodman initiates another lovely combination. Her teammate Lynn Williams has good position on the edge of the box and Rodman curves a cross around a defender to Williams, who heads it into the back left corner of the net. The U.S. squad, winners of the last two World Cups and overflowing with talent, closes out the game with a 4-0 win.

There are plenty of logical questions one can ask about Trinity Rodman—after all, she’s so young, and the arc of her professional career is just beginning—but there is simply no question about her star power. The ability to make something out of nothing. To lift fans out of their seats. To showcase the free-spirited beauty and emotion of the game.

Ponder what Rodman has accomplished in Act I of her career. She reached the professional National Women’s Soccer League (NWSL) without playing a single game in college—and

The truth hurts: Our photographer had to replace a shattered lens filter moments after this frame was captured.

“I want people to see that I’m a regular person and not just a famous soccer player,” Rodman says.

wrapped up her debut season with the Washington Spirit as the league’s rookie of the year. She made the assist on an NWSL championship-clinching goal. Last year she signed a seven-figure contract extension with the Spirit that reportedly makes her the highest-paid player in NWSL history. And now, in her third season, she’s trying to lead the Spirit back to the promised land and get her World Cup storyline off the ground.

These days, Rodman is the object of outsized expectations when she steps on the pitch. She’s been in the spotlight for a relatively long time, at first for being a precocious talent with a famous last name and then for being a prolific talent busy making her own name. When you watch Rodman in action, all of her strengths—her world-class speed and skills, of course, but also the tenacity, creativity and joy that she brings to her game—are on full display.

“I think my personality comes through in the way that I play,” says Rodman, who is finding peace and having outsized fun and making art as she tears around the field. “I feel so much freedom when I’m playing.”

It’s a wet and miserable April evening at Audi Field in Washington, D.C., the kind of night that inspires some people to wear a trash bag like a coat. But the Washington Spirit and the Houston Dash soldier on. Rodman is all over the field, trying to make something happen. In the first 25 minutes, she sets up two corner kicks and makes a nifty pass to give one of her teammates a solid shot on goal. She is clearly the fastest player on the field and she is pressing hard, even on defense, like she can’t bear to stand still.

There is an old chestnut that we are all products of our environment—that we are shaped by the things that happen to us. This is true, of course, but it’s also true that who we become is ultimately shaped by the way we respond to the things that happen to us. We are not simply actors in the drama of our lives; we are the screenwriters, too.

Consider how Trinity Rodman careens around the water-logged confines of Audi Field. She is not such an imposing force by some glorious cosmic accident. She willed it to be. This kind of effort takes something beyond talent. It takes thousands of hours of work. It takes a hunger.

Two days after that soggy game, Rodman is hustling around a cavernous indoor training facility in suburban Virginia, juggling as a videographer captures 360-degree footage with an airborne camera and dribbling through cones with disarming fluidity as another content creator huffs by her side. Meanwhile, her mother, Michelle, sits in a quiet corner, showing a reporter old Facebook videos foreshadowing Trinity’s greatness. In one, uploaded in August 2011—meaning the girl with the ponytail was 9—Rodman bounces off, dribbles through and outflanks several defenders. Someone is shouting at her to shoot with her left foot but she instead uses her right to slot it cleanly into the bottom corner.

“She started playing soccer when she was 4,” Michelle recalls. “She had this clarity about it even then. She would come off the field on the verge of tears and ask, ‘Mom, why isn’t everyone else trying to win? We need a goal.’ ”

Michelle believes that this focus to dominate on the field is a response to chaos off the field. People who have followed Rodman’s career know that her father is NBA legend Dennis Rodman.

“I feel so much freedom when I play,” she says.Rodman loves to paint and draw when she finds the time. “It’s like soccer,” she says. “It’s a way to express myself beyond words.”

Trinity is not keen to discuss the past, present or future of that relationship— she’s focused on establishing her own legacy and on the people who have been by her side the whole way, namely her mother, her brother, DJ, and older sister, Teyana.

Michelle says that Trinity experienced plenty of obstacles growing up. Other girls often were cruel to her, and as she developed as an athlete, people assumed she was advantaged by a life of privilege, heading from practice to a mansion or something. But the reality was entirely different. Michelle was raising these kids as a single mom, struggling financially, sliding from one rental to another around Newport Beach, California.

At one point, the family called a motel home, sharing a room and heating frozen burritos in a microwave oven for dinner. Michelle tried to frame the situation around the positives—the way Trinity and DJ could make waffles at the Comfort Inn’s free breakfast every morning, or take a dip in the small pool before school, or bounce on the beds after dinner. “My goal was always to keep them busy,” Michelle says. “I tried to keep their minds focused on goals.”

So is it any surprise that the soccer pitch became a refuge for Trinity?

“Growing up, people didn’t really know what my family and I were going through,” she says. “They didn’t know what we had or didn’t have. But when I was on the field, everything was equal— there was no talk about finances or living situations or family stuff. It was just soccer—the ball and the field and me. I was always happy on the field. And I still feel the same way.”

From an early age, DJ and Trinity, separated by only a year, were intensely competitive. They treated every sporting situation and even unremarkable household moments like competitions of consequence. DJ recalls that in elementary school, he and Trinity had an ongoing battle to see who could call shotgun on the drive to school—an honor that went to whomever could touch the car first. The increasingly fierce footrace escalated until DJ tripped

on a pipe by the side of the house and wound up getting seven stitches on his head. DJ laughs out loud when he recounts this story—it has, after all, become a bittersweet symbol of their shared grit.

“I’m a lifelong basketball player and she’s definitely more competitive than any teammate I’ve ever had,” says DJ, who has NBA aspirations and recently transferred to USC to play his final year of college basketball. “To say it bluntly, she always wants to win. She really doesn’t like to lose.”

DJ says he knew his sister was something special when she was in second grade and he goaded her to play in a basketball league—a sport she didn’t like or have experience playing. But she wound up playing against fifth graders and more than holding her own. “That’s when you know someone is a truly great athlete,” he says. “When they’re that good at every sport.”

Still, soccer was always her first love. And when Trinity was 10, her trajectory in the sport changed when her mom brought her to a tryout for the Southern California Blues, a youth club that is a force in the greater Los Angeles region, the unparalleled hotbed of soccer talent in the U.S. Rodman’s raw athleticism and obvious drive impressed the coaches and she made the squad, playing with that club until she was drafted.

The simplest way to summarize Rodman’s youth progression as a soccer player is that she kicked ass. She helped propel her club team to a national championship and two different high school squads to glory. She was first invited to play with the national team when she was 13, going on to play with U-16, U-17 and U-20 squads. In the 2020 CONCACAF U-20 championships, which includes teams from North America, Central America and the Caribbean,

Rodman has a lighthearted soul, but the tenacious way she trains and studies film is no joke.

“To put it bluntly, she always wants to win. She really hates to lose.”

Rodman scored nine goals in seven games to help lead the U.S. squad to an undefeated run through the tournament.

After her high school career was over, Rodman enrolled to play and study at Washington State. But before she could play her first collegiate game, the season was canceled due to the pandemic. NWSL rules prohibit high schoolers from entering the draft but now Rodman had cleared that hurdle. On January 13, 2021, the Washington Spirit selected Rodman as the No. 2 pick, making her the youngest player ever drafted in the league’s history. She was 18.

It was the first of many firsts for Rodman. A few months later, minutes after entering her debut professional game, Rodman neatly trapped a long pass and punched it into goal, making her the youngest player to score in the league. She became a starter in the following game. She wound up leading the league in assists that year.

“Honestly, my rookie year was my easiest so far,” she admits. “Nobody knew what I could bring to the table. There basically was no pressure on me.”

It’s a Saturday afternoon in early May, and the sun is out in Washington, D.C. The San Diego Wave—led by the striker Alex Morgan, co-captain of the national team—are visiting Audi Field. With both teams sitting near the top of the NWSL standings and more than 12,000 fans in attendance, it’s a big game. Though Washington controlled the first half, the score is tied until the 55th minute. Spirit midfielder Ashley Sanchez gets the ball in open space and launches a sharp pass behind the defense. Rodman and a defender race at full speed for the ball. In desperation, the defender lunges to deflect the pass, but she can’t quite reach the ball. Yet Rodman, running full bore at a different angle, tracks it down and pokes a shot inches under the left hand of the goalie. The stadium erupts and Rodman flaps her hands over her head in jubilation.

Fifteen minutes later, Rodman ignites another round of celebration. She receives the ball outside the box and accelerates from a jog to a sprint in a diagonal line toward the goal. As she nears the box, the defense collapses on

her. At least four defenders are covering or watching her. Just at the moment where it looks like she might try a spectacular low-percentage shot, she crosses the ball with her left foot to Sanchez, who is streaking into open space. Sanchez slams it into the top of the net. Sanchez and Rodman exchange an absurdly formal handshake, like they’re sealing a business deal.

The Spirit wind up winning 3-1 and Rodman, who is two weeks shy of her 21st birthday, ends the afternoon as the youngest player in NWSL history to notch 10 career goals and 10 career assists.

But this is hardly the only way Rodman is impacting the women’s game. You can see it when you walk around Audi Field during a Spirit match. There, hordes of adolescent girls, many wearing official jerseys with Rodman’s name and number on the back, jump to their feet and holler every time their favorite player charges down the sideline. These girls, who later crowd the edge of the field for an autograph or a selfie, love the dynamic way Rodman plays, and also the youthful, human side she shows when

“I play my best when I’m not overthinking or feeling isolated from the world. I want to feel connected with everybody,” Rodman says.

Rodman admits that she sometimes surprises herself with her own footwork in games.

Rodman admits that she sometimes surprises herself with her own footwork in games.

she posts dances on TikTok or asks her followers for color suggestions as she does her nails live on Instagram. “I want people to see that I’m a regular person and not just a famous soccer player,” she says.

Perhaps no one can better appreciate the combination of talents that Rodman brings to the pitch than her team’s head coach, Mark Parsons. “I think she has the quality to be something that this planet hasn’t seen in women’s soccer,” he says, itemizing the strengths that his young star brings to the table. Her worldclass athleticism. Her competitive mentality. Her technical skills. Her decision-making instincts. Her work ethic. “It’s rare that you find a player with all these qualities, and she’s only 21.”

Parsons describes the intense challenge defenders face trying to cover Rodman. “She can of course run behind you,” he says. “But she also can dribble at your left or your right. She can shoot with both feet. She can pass across and combine with her teammates. You have to be greedy as a striker, but she understands that she wants to feed easy opportunities, too.”

All the players at the professional level have a pretty high level of commitment, but Parsons says Rodman has something extra, a drive that comes from within. “When we don’t have the ball, Trinity chases, hunts and presses like her life depends on it,” he says. And it’s not something that only plays out in the physical realm. Parsons, recalling the flight back to Washington after a recent game in Orlando, says that Rodman spent her time in the air watching a replay of the game they’d just finished. Twice.

One of the beautiful things about the game of soccer is the freedom that it affords. Sure, there are lines on the field and a book full of rules and coaches prowling the sidelines, but the reality remains that skilled players have boundless opportunities to improvise and express themselves artfully.

Rodman is, not surprisingly, an artist. This isn’t a metaphor; she likes to paint when she finds the time. With all the demands of her pro squad and the

national team, it’s been tough lately to find the time. Rodman says she has taken “every art class I could ever take” and travels with a sketch pad—drawing animals and abstract figures and portraits of people she sees. “I love to sketch with a pencil,” she says. “I like to draw whatever comes to mind. I’m not trying to make it perfect. I do it because I love it.”

Once, right before Rodman left to go to college, she visited her sister, who wanted to hire a professional to paint a zoo scene on her son’s bedroom walls. Trinity says she had two hours to kill before she had to head to the airport, so she sketched and then painted a giant giraffe on her nephew’s wall. It’s a cool story, no doubt, but the context is clearer later when Trinity’s mom whips out her phone and pulls up a photo of the giraffe. It’s not some sweet gesture; it looks pro.

“It’s like soccer,” Trinity says, offering a writer a shrink-wrapped transition. “It’s an outlet, a way to express myself beyond words.”

Indeed, there’s an artfulness to the way Rodman plays the game. Perhaps because her feet and her mind often move a little faster than most everyone else, she is able to summon these bursts of creativity that turn ordinary moments into something magical. There is a YouTube video, unironically titled Trinity Rodman Soccer Highlights That Will Blow Your Mind!, that showcases the flair she integrates into her play. She runs down balls that should not be reachable. She pokes the ball through the legs of hapless defenders—megging them, in soccer parlance. And perhaps most of all, she makes gorgeous crossing passes to teammates, as if she has intuited all the angles before she even receives the ball.

“I definitely don’t practice that kind of stuff that I do in games,” Rodman says when asked where this on-field creativity comes from. “It just kind of happens. But as soon as a game begins, my feet just start moving.”

“The best way to deal with pressure is to just ignore it.”

Talking to any 21-year-old, even a high-profile professional athlete, about the future is always strange. They are too busy wrestling with the present and absorbing the recent past to have much bandwidth or interest to peer into the future. This is a beautiful thing, because the present is the place to be. You don’t enjoy a party or live out your dreams in the distant future; you do it right now.

As this issue goes to press, Rodman’s chances to make the U.S. national team for the fast-approaching World Cup are promising but not finalized. Most soccer pundits think that Rodman has the qualities to be a long-term fixture on the national team, perennially the strongest women’s squad on the planet. Right now Rodman faces intense expectations—will she make the team at 21? Start? Score? Show her greatness on a global stage?

If these are questions that Rodman is mulling over, she keeps that to herself. Her mother—whom Trinity calls her “bestie”—says they chat about basically everything, but they don’t talk much about the World Cup. But Trinity is hardly reserved when asked about the differences between practicing with her Spirit teammates and the hall-of-fame caliber players on the national team. Without a doubt, she says, there’s

”Allowing myself to make mistakes has helped my game and my mental well-being,” Rodman says.

something profoundly comfortable about playing with the Spirit—the depth of the relationships and the way she’s been able to intuit what everyone is usually thinking on the field.

Playing with the national team is a completely different story. “The standard is just so high,” she says, noting that many of the top women have played together for 10-plus years. “It’s a very new environment for me, and I have to

focus on gauging that environment, building relationships and learning people’s tendencies on the field.”

One thing she has quickly absorbed is the intensity with which these American soccer legends treat every moment. “There’s no doubt that playing on the same side as Alex Morgan, Megan Rapinoe and Becky Sauermann is surreal,” Rodman says. “You can tell who’s been on the national team for a while because they play with this grit and relentlessness.” There is no such thing as an easy scrimmage or a casual drill.

“That’s kind of the whole point,” Rodman continues. “It’s the national team and we’re not there to make friends. We’re trying to make each other better every step of the way and we’ll work just as hard—or maybe even harder—against each other than against our real competitors.”

Mark Parsons, her coach with the Spirit, is delighted to hear of this reflection and adds that he sees Rodman growing in this regard. “Last year, she was more inconsistent in her impact,” he says. “She would be there, the best player on the team, and then she would disappear and then she would come back. This year she’s been more consistent. This is totally normal for a young player.”

But even as she makes strides to become more consistently relentless during games and practices, Rodman is committed to having a good time. Being serious about performance, she insists, does not require a moratorium on fun. This perspective comes through loud and clear in Rodman’s social media presence. On Instagram and especially TikTok, Rodman is accessible and fun loving.

“You’re never going to shut me up,” she laughs. “I’m always dancing. I’m always singing around the [practice] facility and the locker room. I’m always telling jokes and messing with people.”

This approach even impacts her preparation for big games, where she’s more likely to record a dance clip for TikTok than meditate in silence. “I know a lot of athletes like to spend those moments with headphones on, locked in,” Rodman says. “I’m the opposite of that. I need to be carefree and listening to music—I play my best when I’m not overthinking or feeling isolated from the world. I want to feel connected with everybody.”

Parsons has zero issues with his star’s easygoing demeanor. “I know some coaches who would think she doesn’t care because she’s laughing so much,” he says. “I care about the player being ready to perform. Trin is very loose, full of joy, and you can see in critical moments how she’s full of passion. You can see her bring joy to the biggest moments.”

Not surprisingly, Rodman doesn’t have a simplistic answer when asked how she manages pressure. She holds herself to a very high standard, which influences her approach to preparation— whether it’s in the weight room or during drills or studying film. But beyond that, she tries to filter out external pressures.

“The best way to deal with pressure is to just ignore it,” she says. “Everyone has opinions, but I have a sense that I got here for a reason, and outside pressures do nothing but put your own expectations too high and start impacting every little detail of your game.”

This sounds tricky, holding herself to a very high standard while tuning out things that would raise her own expectations. So I ask her to explain the difference.

“I think the best way to become the best player is to fail all the time,” she says. “And allowing myself to make mistakes has helped my game and my mental well-being.”

In real terms, Rodman says, this means she has learned to trust her instincts, to make quick decisions—about what to do with the ball before she receives it, for instance—and then give herself a break if it doesn’t succeed. She watches hours of film of each game and says she hates seeing herself trying to do something amazing on her own when a teammate was open. But she resists being selfcritical if she tried a pass or a run with a good idea in mind and it didn’t work out. It’s just something to clinically work on and try to do better the next time.

Allowing herself that kind of freedom is a big part of what Rodman loves about soccer. “Outside of team principles, every single player on the field has the ability to do essentially whatever they want,” she says, articulating something about the fluidity of the game and the way that she plays it. “Every player has the ability to be as creative as they want to be, to do dangerous things, to put on a show. There’s something so entertaining about that. I don’t think soccer is just a sport.”

“Every player has the ability to be as creative as they want to be, to do dangerous things, to put on a show.”

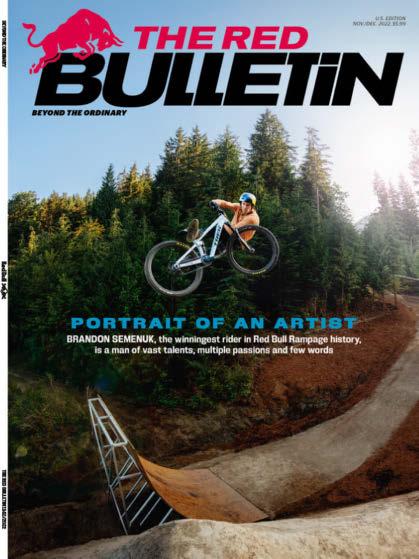

In the plains of Kansas, freerider Tyler Bereman and builder Jason Baker are perfecting a dirt bike course that inspires riders to go big and unleash their creativity.

Words NORA O’DONNELL Photography KYLE LIEBERMAN

For freerider Tyler Bereman, every obstacle is a potential instrument for his artistry. At Red Bull Imagination in Fort Scott, Kansas, his dreams became reality with a one-of-a-kind dirt bike course.

bout 100 miles south of Kansas City and a mile west of the Missouri border, there’s a sprawling cattle ranch in the Osage Plains where dreams come true. The land’s heavy clay soil can be sculpted into a dirt bike course unlike any other, turning it into a mecca for freeriders seeking the ultimate playground.

A few years ago, pro rider Tyler Bereman had a vision. After building a career in supercross racing, he found he was happiest when he rode his dirt bike through the rolling hills of Southern California during his spare time. That natural terrain was where he could discover novel jumps and execute them with creativity. But what if he could build a course that combined all these features in one place?

When Bereman met Jason Baker, he knew he’d found the architect for what would come to be known as Red Bull Imagination. Baker is the owner and main operator of Dream Traxx, the company behind some of the best motocross and

supercross tracks in the world, but this course wouldn’t have a traditional beginning or end. Instead, Baker and Bereman had free rein to invent wild obstacles that could be tackled in any order. The goal would be an invite-only competition, where riders wouldn’t be judged by landing the biggest trick but by the style and flow of their lines. “The whole idea is creativity is king,” says Bereman.

In 2020, Baker brought in a fleet of bulldozers to transform a plot of land near Fort Scott, Kansas, into a world-class freeride course in just a few weeks. The result was so spectacular—and so outrageous—that Bereman couldn’t believe it. “He’d blown my vision completely out of the water,” he says. “He’s an artist, and his paintbrush is a John Deere tractor.”

What Baker built that first year was so mind-blowing that some of the riders were too intimidated to attempt some of the craziest obstacles, including a blind jump over trees and a

30-foot quarter pipe. “We know the inherent risk, but there’s that extra level of love and trust that goes on beyond all of this,” Baker says.

“I 100 percent trust him with my life,” Bereman says. “If he says it can be done, I’ll go hollow head and just go for it. That trust level that I’ve built with him is something that I try to pass on to all the other riders. Listen to Jason tell you how it [an obstacle] should be hit, and I promise it’s gonna work. We have the same brain.”

Every year, the course has evolved. By 2022, the park had close to 120 different jumps and one dirt lip that was cut at a staggering 80 degrees, pushing the limit of what’s possible. “There comes a point where the risk starts outweighing the reward, and we don’t want to dabble with that line,” Baker says.

Bereman and Baker know they’re on the edge of how far they can go, so for this year, they’re focused on getting riders more comfortable with the terrain, building a crowd and creating a better viewership experience for attendees as well as those watching at home.

Indeed, the images shared on these pages offer just a glimpse of the spectacular experience that is Red Bull Imagination, which will return to Kansas in September. “I wouldn’t say that we’ve changed the game,” Baker says of their creation. “We just went ahead and started a whole new game.”

“I gotta pinch myself sometimes,” Bereman adds. “It doesn’t seem real. But it’s not random. All these things are the way they are because of the love and passion that we put behind it.” For more information, visit redbull.com/imagination.

Jason Baker, seen here with his son, Jace, has built some of the best dirt bike tracks in the world, but the opportunity in Kansas was unlike anything he’d ever built before.

“I wouldn’t say that we’ve changed the game. We just went ahead and started a whole new game,” says Baker, the builder behind Red Bull Imagination.

Ryan Sipes, who’s known for his versatility across multiple disciplines, can’t resist a wall ride on the Red Bull Imagination billboard.

“I’m interested in unexpected challenges,” says van Aert, who was photographed in Spain’s Sierra Nevada on May 10.

Wout van Aert is somehow not tired. He recently clambered off his bike after a five-hour ride in Spain’s Sierra Nevada mountains, spinning and churning up 11,500 feet of climbing in summerlike heat. But let’s not get dramatic; for the Belgian pro, this is an unremarkable training effort, a seemingly inconsequential building block. Yet these sorts of rides, piled together with intention, enable him to be a central figure at the most consequential races.

It is the middle of May—roughly a month after van Aert completed a campaign in the storied Spring Classics, a series of one-day European road races among the most prestigious on the international cycling calendar. But rather than head to the beach to recharge with a novel and a cocktail, the racer just got back to work. There is always a looming goal—in this case, he has joined his Jumbo-Visma teammates to begin his buildup for the Tour de France, which departs from the Basque city of Bilbao on July 1.

“To be honest, I also like to go to the beach, but it’s the middle of the season,” van Aert, 28, notes when asked about his current training objectives. “Here is the serious restart of preparation toward summer, and there are different accents necessary for a race like the Tour de France versus what I need for one-day races. But at this camp we are creating a stable base for the whole summer.”

Professional bike racing is rooted in time-tested traditions, and one trend that has defined the sport’s

modern era is specialization. For decades, as the stakes have risen and training methods have advanced, the biggest races in every discipline have been dominated by riders who lean into their specific strengths—whether it’s climbing or sprinting or time trialing or racing off-road.

Van Aert is one of a handful of riders who have taken this paradigm and smashed it to pieces. He entered the public eye as a cyclocross phenom, a rider with the gifts and work ethic to win world championships in that discipline, which demands technical skills and intense power. And he did just that.

But in the past five years, van Aert has kept pushing the envelope, finding success in a mindboggling range of racing endeavors. He has become a key protagonist at the hardest Spring Classics. And he has made a surprising impact at the Tour de France, the most celebrated bike race on the planet, winning stages in every conceivable scenario—in other words, beating the specialists at their specialties.

Van Aert says that his astounding versatility cannot be fully explained by his talents and work ethic. “The biggest thing is that I never limited myself—I’ve never thought that’s impossible,” he says, reflecting on his unexpected breakthroughs at the Tour de France. “I was just always openminded, always wanting to give it a go. A lot of people don’t try it because they think they can’t.”

“The only way to discover the limits of the possible is to go beyond them into the impossible.”

Arthur C. Clarke

“The biggest thing is that I never limited myself,” says the Belgian cyclist. “I’ve never thought that’s impossible.”

Van Aert trains with the JumboVisma squad. Last year he helped teammate Jonas Vingegaard finish the Tour de France in the yellow jersey, given to the overall leader.

Van Aert trains with the JumboVisma squad. Last year he helped teammate Jonas Vingegaard finish the Tour de France in the yellow jersey, given to the overall leader.

Every year that van Aert has ridden the Tour, a teammate has finished on the podium.

This bike-racing legend, like so many others, begins in the Belgian region of Flanders. Van Aert was born and raised in Herentals, a small city near Antwerp. In Flanders, bike racing is hugely popular, arguably even bigger than soccer. Wout’s father was an amateur racer, and the boy entered his first race at the age of 8. After scoring a secondplace finish in that race, the youngster was hooked.

Van Aert, who as an adolescent was already turning heads with his raw power and tactical intelligence, formally arrived on the scene as a world-class talent in 2012, when he finished second in the Junior Men’s race at the UCI World Championships in West Flanders. Standing next to him on the podium was a Dutch teenager named Mathieu van der Poel, who had finished the race 8 seconds earlier. Thus began a rivalry that continues to sizzle today, one already acknowledged as among the greatest in cycling history.

The two teenagers would grow up to dominate cyclocross on the global stage, continually pushing each other to the extreme. To date, van Aert has won three world championships and three World Cup season titles, but those stats fail to fully capture his generational talent. He clearly was on track to establish himself as an all-time cyclocross legend.

But he was destined for bigger success. “It was definitely not a plan—it just came quite naturally,” says van Aert, discussing his transition to road racing. “When I was just a cyclocross rider, I did some races on the road as a preparation and I felt I had a good level on the road, too. So I thought, ‘Why not try some Spring Classics?’ ”

When asked to synopsize the differences between cyclocross and road racing, van Aert offers a brief tutorial. “A cyclocross race is about one hour—and it’s flat-out from the gun,” he begins. “A lot of times it’s a battle against yourself, trying to do the course as fast as possible without any mistakes.”

Road races are a different beast. “They can go up to six or seven hours,” van Aert continues. “There are more easy parts in between, where you need to draft and save yourself for the finale. But there’s always a point where the race explodes. So you definitely need a bigger engine because it’s so long. It’s more about fatigue resistance—often it comes down to who has a tiny bit more left in the finale.”

Commentators and professional racers doubted that van Aert would have the stamina to factor into the final moments of any of the big Spring Classics, especially against seasoned road-racing specialists who were used to the longer distances and hadn’t already raced an intense cyclocross calendar from September to February.

The pundits were wrong. In 2018, his first attempt at a road-racing campaign, van Aert finished in the top 10 at major Spring Classics like Strade Bianche, Gent-Wevelgem and the iconic Tour of Flanders. And after showing steady improvement the following year, he notched a breakout year in 2020—winning Strade Bianche and Milan San Remo and finishing second at the Tour of Flanders and the UCI World Championships. In just three years, he blossomed from an intriguing question mark on the road into a proven superstar.

Van Aert laughs and says his initial participation in the Tour de France was “basically by accident.” One of his JumboVisma teammates withdrew soon before the race began and the Belgian was inserted onto the roster with little warning. Nonetheless, the 2019 Tour started off well. On Stage 10, the rookie van Aert came into the final kilometer with a select pack of 30 riders and outmuscled several elite sprinters for the win.

Immediately van Aert saw how winning a Tour de France stage is unlike winning any other race. “It’s the biggest race in the world and you can feel it on everything,” he says. “If you have a big performance, you have media straight after the finish until you go to bed. I remember getting so many messages and phone calls; it felt like the whole world was watching.”

But the party ended a few days later with a catastrophic crash in a time trial on Stage 13. Van Aert clipped a poorly placed barrier on a tight turn and suffered a deep cut in his thigh. The bloody injury ended van Aert’s season—he couldn’t walk until autumn—and threatened the arc of his career. But fortunately he was able to make a full recovery.

Now, several years later, van Aert has nine individual stage wins at the Tour, a remarkable tally given the variety of the terrain he has triumphed on and the way he has ridden in service of teammates vying for the overall title. Jumbo-Visma is the most dominant team in the sport—on par with Red Bull Racing in Formula 1—so the pursuit of personal glory must be balanced with team responsibilities. Every year that van Aert has ridden the Tour, a teammate has finished the race on the podium.

When asked to pick his most thrilling Tour victories, van Aert singles out two performances. The first came on Stage 11 at the 2021 Tour, on a route that straddled the hulking Mount Ventoux twice. For a larger rider who is known for his power more than his sustained climbing ability, the achievement was startling.

“It’s the biggest race in the world and you can feel it on everything.”

His original plan was simply to get into the day’s breakaway and see what happened. But as the race unfolded, he dropped his breakaway companions one by one and held off the charging generalclassification competitors for the win. “I mean, for me it was kind of a surprise that I could win the stage like that,” he admits.

And then last year, van Aert had another electrifying win, on Stage 4. For two days, he had already worn the yellow jersey, given to the rider with the lowest overall time at the Tour. “Riding in the yellow jersey was for sure a childhood dream of mine,” he says. “But it’s not really common that the yellow jersey can attack and then win the race solo.” But that’s just what the Belgian racer did, pedaling with such ferocity near the top of a punchy climb late in the stage that he dropped everyone and rode alone to the line. As he approached the finish, he flapped his arms like a bird, radiating pure joy.

Van Aert finished the 2022 Tour de France with three stage wins to his name, the green jersey (given to the best sprinter) and the combativity

award, honoring his relentless aggression—and best of all, his Jumbo-Visma teammate Jonas Vingegaard ended the race in the yellow jersey. “Those kinds of achievements make me feel most proud,” he says. “Doing something special means more to me than trying to win certain races three or four times. I’m more interested in unexpected challenges.”

But life is complicated, even for a wildly talented world champion road racer. This year’s Spring Classics season exemplified the sorts of challenges van Aert must wrestle with—and the poise with which he manages them. It’s hard to possess greatness and shoulder the expectation that you will always prevail, especially if you are always competing against others who also possess ethereal talent, train obsessively and relentlessly fight for victory.

Van Aert was self-aware enough to seek the counsel of a mental coach, Rudy Heylen, when he was a teenager. He’d buckled under the weight of pressure in championship races and understood that he needed some guidance. “I felt like it was harder at that time to deal with the stress of going to a championship,” van Aert says. “One of the most important things Rudy taught me is to focus on controlling the controllables. It’s a waste of energy to think about the weather or your competitors.

“Doing something special means more to me than trying to win certain races three or four times,” says van Aert.

And so I started using this mantra— Ik, fiets, focus [I, ride, focus]—as a trick to keep my focus on myself instead of thinking it’s hard or there’s still five laps or I made a mistake there.”

This mental training helped a ton—enabling van Aert to win more big races, contextualize the races that didn’t go his way and remain focused on the things he can control, like his tactical savvy and his dedication to training. Fittingly, when van Aert co-wrote a memoir in 2017 detailing his approach to cyclocross glory, he titled it Ik Fiets Focus. “Yeah, it’s easy to say,” he admits. “But it’s not easy to do.”

Consider his 2023 Spring Classics campaign. One would not be exaggerating to say that in the history of bike racing, van Aert may have posted the best results that could be labeled a disappointment. In the five races that defined his spring, van Aert finished third, first, second, fourth and third. He failed to win the three most important races (Milan San Remo, the Tour of Flanders and Paris Roubaix) but was in the mix in the final moments of all three, seconds or one small misfortune away from victory, beaten by his longtime rival, van der Poel, or another generational talent, Tadej Pogačar. In these iconic races, van Aert, van der Poel and Pogačar were riding on a different level than everyone else.

“It’s special to be in the end of the race always with the same guys,” says van Aert, acknowledging the meaning of these rivalries. “To be one of them it’s already something big—and both Mathieu and Tadej are exceptional athletes.”

Van Aert’s rivalry with van der Poel inspired much public debate this past spring. As they sat on a backstage couch before the podium presentation at Milan San Remo, TV coverage captured obvious awkward tension between the two men. Van Aert later acknowledged that he would never consider his big rival a friend. And now, sitting in Spain two months later, he’s pondering how competition and friendship play out on the racecourse.

“I really think it’s important to respect everyone that’s competing, especially your biggest rivals,” van Aert says. “It’s important to be able to shake hands after the race, because your rivals are training 100 percent and then giving 100 percent to race at such a high level. But I think friendship is something else and it would be impossible to fight against a friend.”

Van Aert’s feelings about friendship and the deeper meaning of competition played out two weeks later at Gent-Wevelgem. There, van Aert appeared to be the strongest rider but wound up out front for the final 50 kilometers with his teammate, Frenchman Christophe Laporte. In horrible weather, the two riders held off a pack of pursuers and in the final moments, van Aert allowed his teammate to cross the line first. Several icons of Belgian cycling criticized the gesture, opining that true champions shouldn’t offer such gifts.

But van Aert couldn’t care less whether he retires with one Gent-Wevelgem title (he won in 2021) or five. “For me it feels like we won this race together,

and I was surprised there was so much talk about it,” he says. “Me and Christophe are good friends. So it wouldn’t feel nice to race for it against each other. I think for Christophe this victory meant a lot more than for me and it was amazing to dominate the field with a teammate and ride in the front for 50K. I have no regrets and it will always be a special day for me.”

The toughest pill to swallow came at the last race of his Spring Classics campaign, Paris Roubaix. There, van Aert showed signs of being the strongest rider, but he suffered a late puncture that allowed van der Poel to solo uncontested to victory. Van Aert admits that he initially absorbed his third-place finish as “a bit of a disappointment.” It’s hard to face so much external pressure and lose such a pivotal race due to a mechanical issue. But a week later, after remembering his priorities and his mantra about controlling the controllables and letting go of everything else, he saw things differently.

“Now I’m just proud of the level that I reached,” he reflects. “It’s important to realize as an athlete that things don’t go always exactly the way you want them to go, but the things I had in my own control I did 100 percent.” (Fittingly, rather than go to the beach, van Aert went on a three-day bikepacking adventure with some of his mates, riding dirt roads from Flanders to Champagne, staying active without studying any power data.)

As our interview winds down, van Aert pauses to describe the legacy he hopes to leave behind after his racing days are over. “Sure, there are still big races to win,” he says. But he is not looking to build a monumental Wikipedia entry; he wants to race with class and heart and panache. “I really like challenges, and it’s an even better feeling when you achieve something that everybody thinks is impossible. I want to be known as someone who tried to do special things.”

In her own words, pro mountain biker Kate Courtney describes how she learned to confront her fears and demystify obstacles by working with veteran rider Jill Kintner.

Words KATE COURTNEY

Closing my eyes, I visualize myself riding off it. Heels down, eyes up, weight centered. I know what I need to do. Yet a part of me still wonders if I will be able to do it when it counts.

Before I can let the doubt creep in, I hear Jill’s matter-of-fact voice shouting up at me. “If you think you can do it, just do it,” she says. Jill doesn’t buy into the drama for even a moment; doesn’t let her imagination fixate on what could go wrong. For her, the calculation is simple. If you know how to do it, then do it.

The confidence in her voice stirs something in me, pulling me back into the moment. I am reminded that this challenge is one I am prepared for. I take a deep breath and turn toward my bike, anxious anticipation now morphing into deep resolve. I don’t hesitate. I clip my feet into the pedals, steady my hands on the handlebars and go.

It is the second day of my most recent skills camp working with Jill Kintner in Bellingham, Washington. Both the town and Jill herself are famous for mountain biking: Bellingham for its endless singletrack filled with well-built features and infinite opportunities to progress. And Jill for being a world champion, Olympian and all-around badass who has excelled in everything

from downhill to BMX racing. For more than two decades, Jill has been a mainstay on the top step of the podium and a threat in any event she enters on the gravity side of the sport.

Jill also happens to be a fellow pro rider with Red Bull, which is how I first met her at a retreat in Texas in 2017. Like on many Red Bull retreats, we found ourselves immersed in a world that seemed almost unbelievable: a quick surf in an artificial wave pool before a helicopter dropped us at a pop-up camp village on Willie Nelson’s ranch.

Jill and I settled into adjacent trailers and, though it was a bike-free weekend, we found ourselves bonding over our shared awe at where cycling had taken us. Though Jill was a veteran and I was new to the scene, there was a synergy in our shared obsession with pursuing our best through the bike. And as I got to know her, I came to appreciate who Jill is as a person as much as I have always appreciated what she does as an athlete.

On the surface, Jill comes off as somewhat shy. She has a quiet voice and a silly sense of humor that endears her to anyone she meets. But as soon as a competitive task is introduced or the topic of racing comes up, Jill has a quiet ferocity and intensity that is unmatched. I love this about her. She is a perfectionist in the most beautiful way—always striving to get closer to that perfect turn, to flawlessly hitting the landing of a jump or building speed with just the right timing through the pump track. Jill doesn’t just have a relentless drive for mastery; she has a creativity and dedication to the process that actually gets her there.

So when I found myself struggling on the World Cup circuit in 2021, I knew exactly who to call. That year was one of the toughest in my career. For many years as a developing racer, things had only gone in one direction—up. I made quick progress through the junior ranks, built steadily as an Under-23 competitor and won the world championship in my first year as an Elite. The next year, I backed it up with World Cup wins, a World Cup overall title and an automatic qualification for the Olympic Games in Tokyo.

But at the start of 2020, things shifted rapidly. In a pandemic year with no racing in the U.S., I dropped from first to 77th in the UCI’s world ranking. Organizers pushed back the timing of our races six weeks at a time, which meant that the training never stopped. And I found myself pushing harder and harder to hold on to the fitness that I had built in the spring. By the time the Olympics at last arrived, a year later in 2021, I felt burned out mentally and overtrained physically. A poor performance in Tokyo only made things worse, and I struggled to even finish the World Cup season.

As I started to recover in the fall, it was time to take a hard look at every element of my game and begin to rebuild. When it came to technical skills, for example, I had the feeling I was missing something.

Over the years, I had worked with a few different skills coaches—mostly men who had competed on the downhill World Cup circuit. Early on, I made quick progress and must give huge credit to Shaums March, a former master’s world champion, for getting me safely around the courses at Junior World Cups. But as I began to progress, skills camps started to feel like a test of my courage more than a progression of my skill.

I feel an odd sense of calm as I peer over the edge of the rock, down toward the steep ribbon of dirt that would serve as a landing over 6 feet below.NICK MUZIK, BRYN ATKINSON(2)

Courtney, shown here racing in Lenzerheide, has worked hard to rethink how she approaches tough technical challenges.

Was the difference between a big jump and a small jump just in my willingness to send it? Maybe the men who were jumping higher and throwing whips effortlessly were just being braver. Fear appeared to be the main obstacle to my progress. So I focused on overcoming it. The “just send it” and “speed is your friend” mentality at least got me to try features for the first time, but as the stakes got higher and the features got bigger, I felt like my skills remained the same.

Even if I could ride something, I could tell my body position wasn’t quite right or that my timing felt a little off. I envied the Swiss riders, who had attended basic skills camps from a young age and seemed to have internalized perfect form. I had learned on the fly and under big pressure to hit features at World Cup events. It felt like I had somehow progressed by sheer willpower alone and with little technique. I remember watching a younger rider at the world championships in Les Gets, France, effortlessly send a big gap jump while I barely made it to the other side

without crashing. More speed helped and I was able to ride it in the race—but I knew if the jump had been any bigger, I would have been in trouble. As the features grew bigger and the competition tighter, it was clear I was beginning to reach the limit of where persistence alone could take me.

My strength coach, Matt Smith, introduced me to a concept that I feel captured the feeling perfectly. He called it the “fallacy of deep water.” The idea is that when you wade into the ocean and begin to swim, you start out in shallow water. You can see the bottom and you have no doubt that you will be able to stay afloat. Yet there comes a moment, as you swim farther from shore, that you realize that you are in very deep water. Fear or panic often sets in as you recognize how far you’ve come from shore and start to reckon with the groundlessness below you. In this moment, you can start to doubt your ability to keep yourself afloat. The fallacy of deep water is that, though your mind might tell you otherwise, the task of swimming remains the same and all that really matters is your ability to execute that skill.

As for my skills work, it felt like I had found myself in very deep water, feeling a little shaky about keeping myself afloat and certainly not eager to venture out any farther. I knew I needed to relearn the basics—and to know without a doubt that I had the ability to meet all the challenges that were sitting in front of me.

“With Jill, fear wasn’t the obstacle. The obstacle was the obstacle.”

That’s when I reached out to Jill.

The first time we rode together—in Santa Cruz, California, late in the fall of 2021—I instantly felt that this experience would be different. It was the first time I’d observed Jill’s meticulous approach to building skills up close. She keeps notes on every subtle change in bike setup, has charts lining her garage with the skills she’d like to master or improve and generally runs a very tight ship on and off the bike. When you train with Jill, it’s not just about getting something right. It’s about getting it perfect. Then doing it three times before you can move on.

When we first started working together, Jill put me on flat pedals and set up obstacles in a parking lot. I spent most of our sessions navigating cones and hopping over sticks before eventually moving on to the pump track. After every task, Jill showed me videos of my body position and demonstrated what the skill should look like when done correctly.

Those first few days would have looked very boring from the outside—no cool tricks or jumps or drops. I never felt even the slightest bit of fear. Yet I was as challenged and focused as I had ever been on my bike. My mind worked overtime to understand the mechanics of each skill and my body adapted to new ways of moving and approaching new features. I could instantly feel how tiny changes in body position or timing made a huge difference. And Jill continued to help me unlock new opportunities to improve. It was exactly what I had been looking for—and I found myself obsessed with how to make progress in this new paradigm.

Over the past two years, Jill has helped me progress from hopping over sticks in the parking lot to confidently navigating some of the biggest features and most technical terrain I’ve ever ridden. Muddy and slick roots and rocks became less intimidating as I learned to pick better lines and keep my body weight in the right position. I went from hitting the smallest jumps on the green line to clearing the gaps on the black line at the bike park, landing centered and in control.

With Jill’s meticulous process, I have built new skills, piece by piece, step by step, replacing fear with confidence in my ability to tackle new obstacles. And as we pushed the limits of drops and jumps on our last camp together, I found that I simply was no longer afraid of the same obstacles that had kept me up at night a few years ago. With Jill, fear wasn’t the obstacle. The obstacle was the obstacle. Our focus was on building the skills necessary to approach it with confidence.

Back atop that intimidating rock feature in Bellingham, I let go of the brakes and descend toward the drop. I am reminded of the fallacy of deep water. Jill has shown me that the water can become infinitely deeper, but all that really matters is whether you know how to swim. When I saw the feature for the first time, I felt afraid. Fear let me know that I was in deep water—that the stakes were high and that I needed to pay attention.

Yet as my wheels begin to turn, I am too consumed by the moment to be afraid—too focused on keeping those feet down and those eyes up. I know how to keep myself afloat. In an instant, I take off calmly and land gently at the bottom, enjoying the satisfying feeling of stretching myself just a bit further than I have before.

As a World Cup racer who makes a living pushing my mind and body to the edge, I know what it feels like to find myself in deep water. I go there often and I am usually alone. But in this moment, I turn and see a big smile on Jill’s face.

“See, told ya!” she shouts through a grin. “It didn’t even look hard!”

I smile up at her and feel proud. And even as I sit in the silent relief of the moment, a quiet curiosity seems to bubble up in me—could I go bigger?

I am grateful for the deep water, for the chance to challenge myself and change myself in the process. And I am grateful for Jill—who reminds me again and again that I know how to swim.

Courtney has discovered that she’s no longer so wary of obstacles that used to push her out of her comfort zone.

Words

Words

Custom car builder, content creator and budding actress Emelia Hartford has found much-needed serenity—at very high speed.JESSICA P. OGILVIE Photography HEIDI ZUMBRUN

“I DON’T DO WHAT I DO TO SHOVE IT IN ANYONE’S FACE. . . YOU EITHER TREAT ME LIKE AN EQUAL OR YOU DON’T.”

Driving north on L.A.’s 5 freeway, Emelia Hartford’s glimmering teal Ferrari 458 on a Tuesday afternoon doesn’t exactly blend in with the other cars. So it’s unsurprising when, less than five miles from her starting point, a highway patrolman finds a reason to pull her over. He keeps her for several minutes, chatting with her through the window, then lets her leave.