join.oanda.com/us-en/red-bull-rampage

Performing a blend of genres he calls “cross country,” Breland has woven together a variety of his musical infuences into a sound that is at once unique and undeniably country.

join.oanda.com/us-en/red-bull-rampage

Performing a blend of genres he calls “cross country,” Breland has woven together a variety of his musical infuences into a sound that is at once unique and undeniably country.

PETER FLAX

There is a time-honored metaphor that compares the pursuit of success to the process of climbing a ladder. This suggests that the pathway to greatness may be as straightforward as working hard to ascend toward a goal in a well-defned and linear manner. Sometimes success can be achieved in this fashion, but more ofen than not achieving your life goals is considerably more complicated and unpredictable than that. Frequently, people realize the ladder has been leaning against the wrong wall and that they need to create an entirely new plan to strive toward a diferent goal.

Several people featured in the issue you are holding have life stories that demonstrate this kind of purposeful adaption. Consider, for instance, our cover story—on Breland, a fast-rising country singer-songwriter. He was raised on gospel, then developed a ferce interest in soul and hip-hop, all before melding these infuences with his growing passion for storytelling and country. He calls his genre “cross country,” and his success is part of a broader movement in which the country scene is getting more diverse and richer in texture.

In the same vein, the incredible life story of Parks Bonifay, a champion wakeboarder turned creator and ambassador of fun, illustrates how we’re all capable of evolving and fnding new successes in a nonlinear path. For 15 years Bonifay was a dominant athlete in his sport, arguably the GOAT of wakeboarding, but he has smoothly transitioned—to be a wildly creative performer, a mentor to the next generation of pros and a versatile waterman— to remain relevant into his 40s.

And then there’s the inspiring story of dancer SonLam Nguyen, a popper who recently won the Red Bull Dance

Your Style National Final in Atlanta. Born and raised in Vietnam—he moved to the U.S. in 2017—he had to face all sorts of adaptations and challenges to fnd his way. If you read his story, you’ll learn more about the hardships he faced and the ways he sought tranquility to center himself and fnd success. Nguyen’s journey was hardly as simple as climbing a ladder to success—it was far more difcult, and far more rewarding, than that.

We hope you enjoy these and all the other stories in this issue—and, of course, that they help inspire you to place a ladder against a diferent wall and continue your ascent.

Sometimes people realize that they need to create an entirely new plan to strive toward a different goal.

PHOTOGRAPHER

“Being from the South, I grew up really appreciating and loving country music,” says the photographer, who grew up in Atlanta but now resides in L.A. and shot our cover story on country sensation Breland. “I remember a lot of people back then thought it was weird that this Black kid from the city had Garth Brooks and OutKast on the same CD mix.” Askew’s clients include Hypebeast, Adidas, HBO, GQ and The New York Times. Page 10

WRITER

The Atlanta-based writer and event host—who authored our cover profle of Breland—has been covering music, sports and other cool shit since 2003. He is the co-author of The Art Behind the Tape, a coffee-table book documenting hip-hop mixtape history. He’s also hosted concerts for Big Boi, Kendrick Lamar and Travis Scott. Garland’s work has been published by Spin, Billboard, Complex and XXL. Page 10

PHOTOGRAPHER

“My shoot with the incredible SonLam was truly a dream because of all the freedom I was given,” says the L.A.-based photographer, who shot the dancer in a botanical garden. “I was able to roam around the location with the athlete at our own pace and try many different things. The whole process felt organic and I couldn’t be happier with the results.” Govea’s clients include Apple, Nike, Spotify and LiveNation. Page 38

PHOTOGRAPHER

Mulka, a self-taught photographer based in Detroit, found a passion for livemusic photography early in his career and quickly fell in love with the captivating atmosphere of Stagecoach in the Coachella Valley. “I like to think my joyful personality matches the joy of that festival,” he says. His clients include AEG Presents, Goldenvoice and Paxahau. Page 22

8 COUNTRY

Breland The singersongwriter charts a unique path to country stardom

Portfolio: Jake Mulka The photographer captures the warmth of Stagecoach

The Nashville music series champions fresh country

Priscilla Block shares four tracks that empower her

SonLam The champion popper is powered by an unshakable calm

Bull Batalla Spanish freestyle rap takes off in the U.S.

Red Bull Culture Clash

NYC’s vibrant parade scene comes to life in an epic battle

66 WATERSPORTS

Parks Bonifay The legendary wakeboarder is in it for life

Red Bull Foam Wreckers A surf contest that’s all about serious fun

Kai Lenny

The surfer gives back to Maui

88 BIKE

Hannah Bergemann The freerider is ready to reach new heights

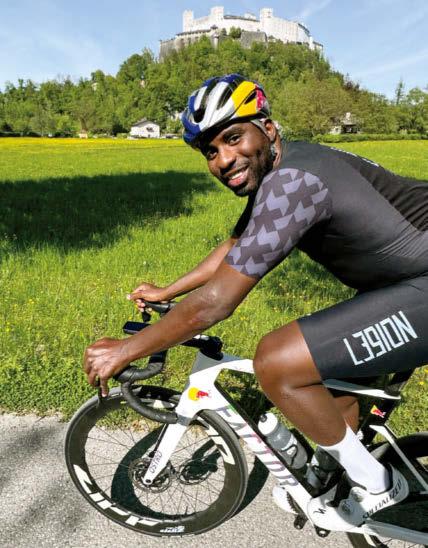

Postcard from a Pro Bike racer Justin Williams has an Austrian adventure

Fabio Wibmer

The trials icon nails a cool trick for LeBron in a new flm

122 Gear Powerful devices to get you in top shape 36

104 SPORTS + FITNESS 106

MiLaysia Fulwiley

The fashy college hoops star is no fash in the pan

114 In the Moment Breaking records like an All-Star

116 Train Like a Pro Surfer Ian Walsh shares how he trains with intention

Singer-songwriter Breland is charting a unique path to becoming a country star by honoring all the genres that have shaped his distinctive sound.

alking down Fifth Avenue on a Wednesday afternoon in downtown Nashville, Tennessee, feels about as busy as you would suspect in any capital city. Vacationers wearing cowboy hats and Crocs in “sport mode” are moving slowly as they visit local tourist spots, while working people in attire ranging from business to construction are rushing back to their jobs after eating lunch. Moving at his own pace, country artist Breland is living both of those paths as he wraps up the last leg of a playful, hours-long photo shoot on a balmy day in late June.

The day began at contemporary residential skyscraper 505 Nashville. Throughout the shoot, Breland is open to the photographer’s spontaneity, despite it requiring multiple elevator trips and calls to the building staff for key-card access. One minute he’s shooting pool at the game room on the seventh floor of the apartment renters’ wing; the next he’s playing John Legend’s “Ordinary People” on the Yamaha grand piano inside the luxe eighth-floor lounge for the building’s condo owners. As the day goes on, residents’ facial expressions range between an inquisitive “who?” when they see him with a camera crew and an annoyed “why?” when they can’t fit on the elevator with them. Breland responds to both with the same pleasantries.

505 Nashville has a commanding presence in the city, standing 45 stories tall, with a glass facade that reflects every color in the sky. But the photo shoot’s next location, the historic Ryman Auditorium, with its arched stained-glass windows, still manages to tower over it with 132 years of music history.

Formerly home to the legendary Grand Ole Opry, the Ryman is flanked by statues honoring some of its past performers, all of whom left their marks on country music. Among them are pioneering female singer and guitarist Loretta Lynn, bluegrass music creator Bill Monroe, and its latest addition, Charlie Pride, who is known as the first Black superstar in country music.

While Breland is a long way from getting bronzed, the goldand platinum-selling 29-year-old singer-songwriter already has a mainstay presence at the venue and is becoming hard to ignore. Ever since crashing onto the music scene with his 2019 viral hit “My Truck,” Breland has been on a mission to change the way people view country music and Black people’s position in it. The song emerged on the heels of Lil Nas X’s crossover smash “Old Town Road” and Blanco Brown’s dance anthem “The Git Up” and a year before Nelly’s collaboration with country duo Florida Georgia Line, “Lil Bit.” All of which feature Black men as the lead vocalist on a country song, foreshadowing the current larger wave of Black artists swerving over into the country lane.

Going on to plant his flag with 2020’s Breland EP and his 2022 debut album Cross Country, Breland quickly became one of country music’s most sought-after collaborators due to his exceptional songwriting and penchant for melody. Just four years into his solo career he’s already been on tour with country queen Shania Twain, co-written two songs with Grammy-winning star Keith Urban and won an Academy of Country Music Award (in 2023). This June he was named a Global Music Ambassador for the U.S. State Department alongside artists like Chuck D of Public Enemy and Herbie Hancock, who will all be tasked with “elevating music as a diplomatic platform to expand access to education, economic opportunity and equity, and inclusion.”

It has to be mentioned that he was already doing that before the government gave him a job title. Since 2022, he’s hosted his

annual “Breland & Friends” benefit concert at the Ryman, where a long list of music superstars, including Josh Groban and Nelly, have joined him on stage to perform duets and create a slew of one-night-only memories for sold-out crowds. Last year’s show produced a live album, and to date, the event series has raised more than $300,000 for the Oasis Center, an organization dedicated to helping youth in Middle Tennessee, with services ranging from crisis intervention to college prep.

With so much on his plate—including opening for fellow genremashing artist Teddy Swims’s tour starting in September and performing at a new event called Red Bull Jukebox in October— no one would blame Breland for catching a breath on this walk he’s taking. But with the path that he’s helped to clear getting more occupied by the day, he doesn’t feel like he can slow down right now.

“When I came onto the scene, it was me, Kane Brown, Mickey Guyton, Darius Rucker, Jimmie Allen, Blanco Brown as far as Black artists in country music that had [record] deals,” says Breland, literally counting the names on one hand as he recites them.

“Now there’s probably 15 to 20 Black artists that have deals and are putting music out. Beyoncé coming into this space changes the landscape, and now there’s more diverse crowds that are tapped into country music and country music is having this really unique cultural moment that I definitely feel like I contributed to in a meaningful way.”

He pauses. “But it’s also something that I feel like I need to turn the gas up a little bit more, because there’s always more work to be done.”

The story of Breland and his breakthrough song “My Truck” has been well documented. The track, produced by Kal V and veteran songwriter Troy Taylor, features Breland harmonizing about Air Jordans, blunts, V8 engines and plenty of other things Americans of all races enjoy, over trap drums met with guitar picking. Originally released independently, the song picked up major momentum online, leading to Breland signing a record deal with Atlantic Records in 2020. The natural order of things was supposed to go: Take the song to radio, get it played, put out an EP and go on tour. But just as that plan was coming to fruition, the world stopped due to the coronavirus pandemic and the subsequent quarantine restrictions that came with it.

“We took ‘My Truck’ to pop radio literally a week before the pandemic hit,” remembers Breland, whose self-titled EP still dropped in May 2020 in hopes of salvaging some of the lost momentum. “They didn’t do anything, because people aren’t commuting to and from work anymore, so nobody’s listening to the radio.”

While radio and touring were no longer options, streaming still helped the project move along, with “My Truck” earning a gold plaque that August and then a platinum one the following January. (In June 2024, the single eclipsed the double-platinum mark for selling 2 million copies.) So the Breland EP served to introduce the singer-songwriter to audiences in the country

and hip-hop/R&B worlds who may have been curious about what each other were doing, but not so much that they would come over and introduce themselves.

“It was a social moment where there is now a song where you had like Black dudes in Atlanta and Houston and white people and old people and young people all vibing with this song,” says Breland. “That doesn’t really happen a whole lot in music because it tends to be segmented and the music industry has made it that way. There’s a lot of history to support that. So I knew that what I was doing was different and that it did have the chance to build a bridge between cultures that don’t always have anything at their epicenter.”

While it would be nice to think that technology has flattened the fences and made everything available to everybody all at once, that is only partially true. Because of algorithms, curated playlists and other metrics that continue to shape listeners’ tastes, it can be argued that audiences are as segregated as ever. In theory, a hardcore hip-hop head can click on a digital service provider’s “Hot Country Music” playlist out of sheer curiosity. Just like a lifelong country music fanatic could do the same with an R&B playlist. But if there’s nothing or no one there framing it in a way that would help them understand the music or the people behind it, it’s not likely they would take any real interest. It’s Breland’s hope that music like his can be that introduction past

the marketing and closer to the idea that people can find and appreciate what they have in common.

“I think country music and hip-hop are really two sides of the same coin,” says Breland. “You’ve got people that are expressing themselves in a way that doesn’t have any rules. To me, what makes that album a country album is that in its own way it is telling stories, and I think hip-hop does the same thing. It’s just using different language, production and instrumentation, but it’s the same thing.”

At age 29, it has taken some contrasting life experiences for Breland to arrive at seeing things that way. Born and raised in Burlington, New Jersey, Daniel Gerard Breland grew up exclusively around gospel music, as both of his parents were ordained ministers who also recorded and performed music themselves, touring churches and other small venues. With the town being just 40 minutes northeast of Philadelphia, he was also raised in the religion of sports, which explains why his Instagram feed mostly features videos of him singing or giving game predictions—or, at his apex, singing the game predictions.

Brought up in a musical household, Breland says he and his siblings had to learn how to sing whether or not they planned on pursuing the craft professionally. Luckily for him, when he did decide to do music for a living, he had tons of research to pull from.

“One of the benefits of growing up in an environment like that is we had Pro Tools when I was 9 years old,” says Breland of the popular audio software, adding that seeing his parents hold down day jobs while also producing music kept him inspired when he found himself in the same situation starting his own career.

“So now I have 20 years of Pro Tools experience where, if I’m in a studio and the engineer is moving too slow, I’m like, ‘Get out the way, bro—I’m about to just sit down and get this done myself.’ It brings me a lot of joy to be able to record myself, because it is a very grounding and fundamental experience from my childhood.”

It wasn’t until he left home and went to boarding school at the Peddie School in nearby Hightstown, New Jersey, in his teenage years that he was exposed to other genres like R&B, rock and rap. Up to this point, the only experience he had actually doing music was singing in his school and church choirs or singing background for his older siblings in impromptu performances at home. Now that he was out on his own, he wanted to try making this new music he was hearing. It was here that he started working with his roommate, who had the tools and instruments to help him do just that.

“The way my brain works just as a musician, when I hear two songs that are totally different, I’m immediately thinking of how they’re similar,” says Breland. “I love seeing how rock songs would play with these chord progressions and what types of production elements they would use and what really makes something a rock song, what really makes something a country song. Being able to find those similarities was just really exciting to me, just got my brain moving in a different way.”

Breland’s different way began to take shape when he declined admission into NYU’s highly coveted Clive Davis Institute for Recorded Music to instead study business at Georgetown University. He explains the decision simply, stating, “I already knew how to make music” and instead wanted to learn the business side of the industry he dreamed of entering. While at Georgetown, he joined the university’s long-running a cappella group, the Phantoms, but off-campus

he began dabbling with rap music, linking with producers Austin Powerz and Lee on the Beats, often working out of DJ Khaled’s New York City studio. Breland is the first one to admit that, as a studious college student raised in the church, he felt like a fish out of water in that environment. But he notes that he was able to connect with everyone in the room because they all spoke the language of music.

“Regardless of what everybody else was into in their personal lives or in their social lives, I knew when we got in the studio to make music, they could respect me as their peer because I’m gonna come up with melodies and I’m gonna come up with lyrics,” he says.

Unfortunately, activities in people’s personal lives are exactly what eventually impacted his decision to move on. One of the main artists with whom he’d built a rapport—a rappper from Queens and protégé of French Montana named Chinx—was gunned down at an intersection in 2015, changing Breland’s mind about what avenue he wanted to take into the music industry.

“It really rocked me because I hadn’t really been exposed to that kind of violence,” says Breland, adding that had it not been for Chinx telling him to stay in the studio and finish the songs they were working on, he would have been in the car with him that night. “I felt like at that point, I don’t know if I wanna be in this scene. It felt like the Fresh Prince of Bel-Air moment where ‘my mom got scared’ and said you can’t go to Far Rockaway, New York, anymore.”

After finishing up at Georgetown, earning a degree in marketing and management, the next mile of Breland’s walk took him where most people in his situation go: Atlanta. While the nicknames like “the Black Mecca” and “the Motown of the South” have begun to grow gray hairs, the city still remains a hotbed for young Black musicians looking to get to the next level—the catch being that there are so many of them.

“I personally loved how many people there were in Atlanta that were trying to make music, because it felt like it gave me a bit of a community,” says Breland, responding to the notion that being yet another Black person in Atlanta making music could lead to being completely overlooked. “I was learning from a lot of these people. I also knew that my skill set was unique, because while I did understand how to speak that hip-hop and R&B language, I was also approaching music more from a Nashville perspective.”

To Breland, the “Nashville perspective” means creating melodies and writing lyrics that, as he simply puts it, “make sense,” instead of relying on a stream of consciousness, just saying things that sound cool. This linear approach to songwriting slowly started to get Breland noticed in industry circles, catching the ear of

people like the previously mentioned Taylor, which led to getting placements with artists like Trey Songz, YK Osiris and Elhae. While reading his name on album cover credits felt great, opportunities were still trickling instead of flooding, leading to him taking a corporate job and working a side gig as a vocal coach to make ends meet. Around this time, Breland was also starting to wonder if he was being pigeonholed. He knew he could sing but was advised to remain a writer. He listened to different musical genres but was only being approached to write in the hip-hop, R&B and occasionally gospel spaces.

Wanting to try something new, Breland got back into the experimental phase he had first explored in high school. One of the fruits of that phase, “My Truck,” wound up pushing his career into four-wheel overdrive.

Soon after signing his deal, Breland relocated to Nashville, sensing that the direction his music was going would be more welcome there. Which was probably the best thing he could’ve done at the time. Atlanta’s musical identity is a by-product of its predominantly Black population, built on a legacy of artists including Curtis Mayfield, Bobby Brown and OutKast. It’s also

the birthplace of trap music and home to multiple Black megachurches. In such a crowded musical landscape, there wasn’t much room for Breland to find his path to success. Years prior, popular country singer Kane Brown had a similar go at it, learning that being a Black country artist in a Black city doesn’t always work before finally moving to Nashville himself. Things were looking up for Breland until March 2020, when the music industry slowed down due to COVID.

Forced into quarantine like the rest of the world, Breland figured that since everyone, including in-demand producers, songwriters and artists, were all at the house and not touring or bouncing around studios as usual, he should shoot as many shots as possible. This led to him forming online relationships with dozens of people despite being new to town. Those bonds would pay off in the form of a star-studded cast joining him for his 2022 debut album Cross Country, featuring appearances from the aforementioned Urban, Guyton, Lady A and Thomas Rhett, with writing contributions from Sam Sumser, Sam Hunt and Hardy to name a few. Some of these same friends and more have performed at “Breland & Friends” too. A rolodex of this kind usually belongs to artists who have already proven themselves with a string of hit records. In Breland’s case, he garnered all of this support in less than five years.

“Country music is a space where being of value to the environment in which you’re working trumps everything,” says Nashville-based country music reporter Marcus K. Dowling, about how and why Breland can already be surrounded with such talent. “So if you’re an A-plus-level songwriter or if you’re a fantastic arranger-producer-composer and you’re also somebody who understands exactly what a vocal should sound like and you can do all of these things like Breland can? Then when you put him into those rooms, he is immediately a person of great value.”

The success of “My Truck” came at a time when genres, especially hip-hop and country, were beginning to flirt with each other more often, as more artists began to try different styles in hopes of reaching a larger audience. While the song’s clever songwriting and clean production kept it from being seen as a gimmick, there was still a hint of “oh that’s different” to the tune. But since then, more Black artists who were well known in rap and R&B are stepping into cowboy boots, making it look normal while making history in the process.

In 2022 we saw Chicago drill rapper Lil Durk link up with country bad boy Morgan Wallen for the hit song “Broadway Girls.” The following year former Love & Hip Hop cast member K. Michelle announced she was leaving her R&B career to start a new one in country. In spring 2024, Beyoncé’s single “Texas Hold ‘Em,” from her album Cowboy Carter, was replaced at the top of Billboard’s Hot Country Songs chart by Shaboozey’s “A Bar Song (Tipsy),” marking the first time two Black recording artists consecutively occupied the chart’s No. 1 spot. (Both songs peaked at No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100, too.) In the months after that we’ve seen Quavo of Migos enter the country chart with his Lana Del Rey collaboration “Tough,” and LVRN, a label known for acts like 6lack and Summer Walker, sign its first country artist, Tanner Adell, off the strength of her trap-tinged country song “Buckle Bunny.”

Where many artists could view more people entering a lane as competition for attention, Breland still views it as an opportunity for everyone to thrive. But, as he stands on the sidewalk between Pride’s statue at the Ryman and the National Museum of African American Music right across the street, he does have a place in mind where competition could be welcome.

“The BET Awards would be a great space where you could have an award for Best Country Artist, Best Country Album and let it be by the culture for the culture,” says Breland, well aware that the awards show is being taped in Los Angeles the same weekend we are speaking. As of 2024, there are no country music categories at the awards show. “We’re still probably a couple years away from that, but I do think it would be great, because we’re probably not going to fully be able to break down some of those other barriers within the country music world. So why not try something else? There’s a lot of artists in this space now that are making music at a high level. And I just think that exposure on a night like that would be really dope, man.”

The photographer has a talent for capturing intimate moments on stage. Here he shares country’s engaging warmth at Stagecoach.

BY NORA O’DONNELL

“I remember the joy of the hobby when I was younger, and I wanted to pursue that,” says the Detroitbased Mulka, who started shooting photos when he was 7 years old. An avid skateboarder, he attacked learning photography from every possible angle as he got older. “My father is a musician. I never had musical talent, but I wanted to understand it, to photograph it and express myself in that way as an artist.” he adds. At Stagecoach, the iconic country music festival in Indio, California, Mulka has witnessed the rise of newer artists like Zach Bryan, as well as the commanding power of megastars like Carrie Underwood and Eric Church. But, he says, the one thing

that’s truly captivated him is the festival’s atmosphere, as you can see in the below image of Ryan Bingham.

“There’s a unique warmth and a certain romance to the way the light falls there at golden hour. The dust kicks up and you have all these beautiful silhouettes of people dancing to country music. For some reason, there’s something about Stagecoach where I feel like I can pull out very intimate moments.”

Mulka had hoped to capture Lana Del Rey on the main stage at Coachella, Stagecoach’s sister festival, which occurs two weekends earlier, but his camera was stolen. Luckily, he got a tip that she would be making a surprise appearance with Paul Cauthen at Stagecoach. “It was serendipitous,” he says. “I got to photograph her perform in this genre-bending moment in an intimate little set. It was just magic.” Above, Charley Crockett shows off his vintage cowboy style, while our cover star, Breland, busts out some of his signature dance moves (facing page, top).

“I’ve wanted to capture Orville Peck in my own style for a very long time,” Mulka says. “When he walked out on stage in his full getup, dressed to the nines, it was so cool.” For Mulka, shooting the style at Stagecoach is a highlight.

“There’s a beauty in country fashion that some people don’t understand,” he says, “an ornate set of boots or a really awesome hat. There’s such an appreciation here.” Above, the actress and singersongwriter Lola Kirke kicks off the 2024 festival while donning a cherry-red outft.

At right, newcomer Levi

embraces the wolf motif.

“What is country? Country is an interpretation. It’s subjective,” Mulka says. “You can bring your own fair to being country, and I think that’s more present in this current age of the genre. It’s lovely to see the evolution and capture it, because it’s a moment in musical history.” On this spread, Mulka captures some artists of this moment within the genre, including Bailey Zimmerman, Luke Combs and Brittney Spencer. Of Zimmerman, Mulka says, “He really bared his heart and soul—so much energy.”

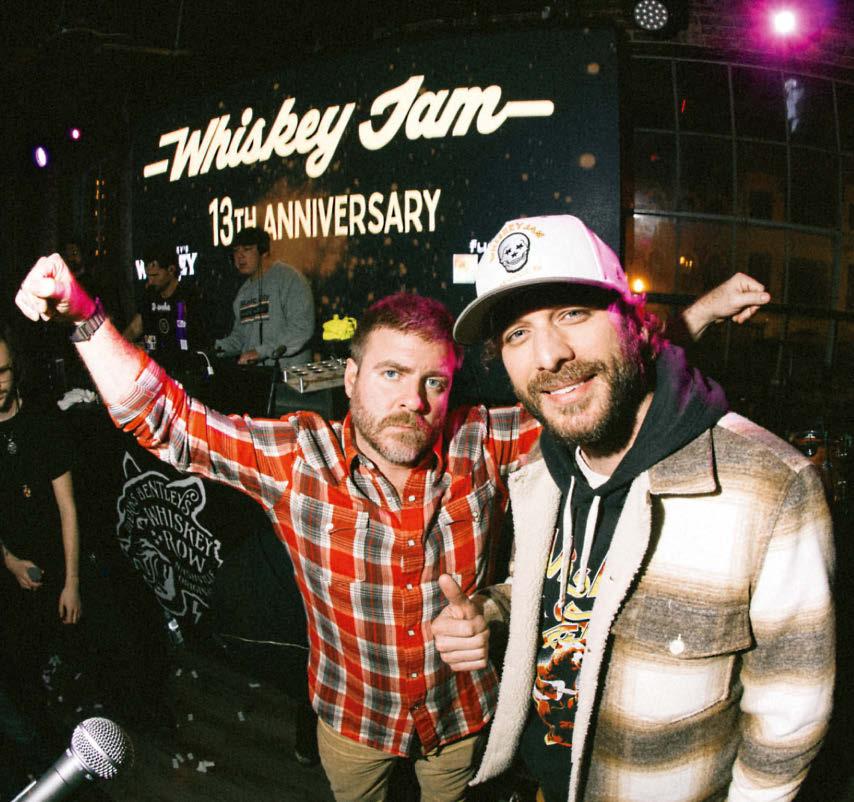

For years, the music series Whiskey Jam has championed Nashville’s newest sounds.

Every night in downtown Nashville, a swell of live music pours out of the crowded bars on Broadway Street. Some honky tonks embrace the early days, where cover bands play “White Lightning”—a rockabilly hit made famous by country artist George Jones in 1959—on steady rotation. Then there are the celebrity-backed watering holes that lure in boot-clad tourists with Dolly Parton standards. Workin’ 9 to 5? What a way to spend vacation. But for those seeking discovery, there’s a beacon of new music tucked

inside a gastropub near the corner of Fourth Avenue.

Every Monday and Thursday night on a small stage on the second foor of Dierks Bentley’s Whiskey Row, aspiring artists showcase original tunes to a curious crowd. As patrons down cold beer and stif shots, a bearded man sporting a baseball cap, polo shirt, shorts and running shoes jumps up to the stage and introduces each group with a childlike giddiness. “Golly!” he exclaims. “The bands tonight are really, really incredible. I’m fred up!”

The unassuming host is Ward Guenther, Nashville’s ultimate hype man. As the co-founder of Whiskey Jam, Guenther has spent the past decade giving some of the freshest talent in the country music scene an outlet to perform, ofen at a moment when they’re on the cusp of major success. Some of today’s brightest stars— including Morgan Wallen, Luke Combs, Lainey Wilson and countless others—have graced the tiny stage, and since the music series launched in 2011, nearly 400 No. 1 singles have been written or performed by Whiskey Jam alums. And this October, Whiskey Jam will host Red Bull Jukebox, where Shaboozey, Brothers Osborne, Priscilla Block, Tucker Wetmore, Breland—and other artists—are slated to perform in Nashville. If anyone can claim he has his fnger on the pulse of country music, it’s Ward Guenther.

Of course, it wasn’t always that way. Before Guenther became an arbiter of taste in Music City, he was slinging drinks at a bar while chasing his own dreams of becoming a musician.

“I moved here afer college and didn’t know anybody,” says Guenther, who graduated from the University of Tennessee in Knoxville in 2003. “I went out every single night to a diferent music event, and I completely fell in love with the social scene in Nashville and the friends you could make.”

Over the years, Guenther’s network grew as he hustled to make it as an artist. He wrote songs, signed up at open mic nights, played in cover bands and toured as a backing musician. During his early years in Nashville, he noticed there was a chasm between the more subdued nature of

“I want to keep the real nucleus of what we do the priority— keeping the magic of music in its purest form.”

songwriter nights, where people hung on every word, and and the higher engery of a band showcase or an informal jam with friends. What if there was a way to marry those elements and make it really fun?

The answer came through a fortuitous text message, in a tale that has become Whiskey Jam legend. Guenther was about to go to bed when a friend pinged him, Let’s go play some music. It was a rare night of, but Guenther rallied. This was the reason he moved to Nashville.

“We just played for fun,” Guenther says. “It wasn’t a gig. It was just for the joy—the purest night of sharing a good time with your friends.”

The next day, Guenther sent out a tweet thanking everyone for coming out for the “frst-ever Whiskey Jam.” Immediately, his friend and frst business partner, Josh Hoge, recognized the potential of creating an atmosphere where anybody could come play, discover new music, meet new people and have fun. Hoping to recreate the same ambience, they texted everyone they knew—about 250 songwriters, signed artists, session and touring musicians—and invited them to come out and jam. And everyone showed up, including Brett Eldredge, Chris Young, and Charles Kelley and Dave Haywood of Lady A. “Immediately out of the gate, it’s funny how efective it was at flling that gap,” Guenther says.

As the years have passed, Whiskey Jam has become its own ecosystem. Every Monday and Thursday night, Guenther books a handful of acts to perform. Some bands come to him through a submission form, while others come through suggestions from friends. Every lineup is diferent by design. “I’m very conscious of it not

Before he had three No. 1 country albums, Luke Combs wowed crowds on stage at Whiskey Jam. Since then, he’s become a regular fxture of the

being ‘Ward Guenther’s Whiskey Jam,’ ” he says. “I try to book bands that I don’t know. It’s opened my eyes to new bands, and I think it’s the best approach to attract the most people in the widest variety of fans.”

“I can say on a regular basis, you’re probably not going to like everything you see, but you’re going to like a bunch of it,” Guenther continues. “It’s like a sampler platter, and it’s great for this generation. You’re not going to a twoand-a-half-hour concert of one band; you’re getting a 24-song mixtape. It’s all diferent. And in a Nashville setting, it’s hard to have a bad time.”

Now, 13 years and nearly 1,000 shows later, Whiskey Jam remains the same at its core. During one Thursday-night show in late June, the lineup includes acts from all over the country, such as Rodell Duf from Houston, and the Deltaz, a brother duo from Los Angeles. “I don’t expect you to know half of these bands,” Guenther tells the crowd. “But that’s the beauty of it.”

It’s also not unusual for bigger names to make an appearance at Whiskey Jam—Keith Urban, Randy Travis and Chris Stapleton have all dropped in. Raspy-voiced rocker Melissa Etheridge reached out when she wanted a real Nashville experience. Even NFL legend Peyton Manning hopped onstage to sing his rendition of “Rocky Top” while Guenther strummed along on his guitar.

There have been missed connections, too. One time, an artist opening up for Justin Bieber sent him a DM on social, but that week’s lineup was stacked and Guenther didn’t recognize who it was. His name was Post Malone. “That is my biggest regret,” Guenther says, emphasizing that Post has an open invitation to come to Whiskey Jam whenver he’s available.

“Through the years we’ve had so many amazing artists,” Guenther says. “But over and over again, I get most excited about these random occassions where an artist will play and you’ll see a diferent reaction in the crowd. We saw that with Luke Combs.” Indeed, before Combs had multiple No. 1 hits on the country charts, he submitted to play Whiskey Jam and wowed the audience with his soulful appearances.

Other artists swing by just to watch. Shaboozey, who at press time topped the Billboard Hot 100 and Hot Country charts with his summer smash “A Bar Song (Tipsy),” has stood in the crowd on several occasions. “He’s drawn to our event as a cool place to hang and meet people,” Guenther says. “We were trying to fgure out a time for him to come play, and then he blew up.”

Thankfully, Guenther has found a bigger stage. On October 2, Shaboozey will be joining the lineup at Red Bull Jukebox at the 6,800-capacity Ascend Amphitheater in Nashville. “I’m so glad we’re having this event where we can bring him into the Whiskey Jam family, where we can mix together what he stands for and what we stand for,” Guenther says. “As Nashville evolves, I want to make sure we grow and serve more people, get more music to more ears, and keep the real nucleus of what we do the priority— keeping the magic of music in its purest form.”

Nashville-based singer-songwriter Priscilla Block on the songs that inspired her to empower others through music.

Priscilla Block is as unapologetic as they come—and she wouldn’t have it any other way. The 28-year-old singer-songwriter found fame thanks to her 2020 viral hit, “Just About Over You,” but it’s her bold stance on body positivity and self-love (as heard on songs such as “Thick Thighs” and “PMS”) that earned her a loyal fan base. “I struggled with my confidence for years, but now more than ever I love myself and I want people to feel that way, too,” she explains. Here the country star highlights four songs that played a huge part in her growth as a musician and empowered her on the path to stardom.

Priscilla Block’s new EP, PB2, is out now. See her live in Nashville at Red Bull Jukebox on October 2; redbull. com/jukebox

KACEY MUSGRAVES

“Follow Your Arrow” (2013)

“This whole song is just about being who you are and never letting anyone change you. Kacey’s songwriting is what inspired me to write a song like ‘Thick Thighs,’ and I think it’s songs like this that inspire artists to put out music that promotes the importance of being who you are and being unapologetic about it.”

JASON ALDEAN

“The Truth” (2009)

“As an artist you always want to make timeless music. This is one of those songs that I can listen to on repeat, even now, and never get sick of it, and that’s inspiring as a songwriter and an artist who puts out music. It’s a really sad song, but for whatever reason it doesn’t make me feel sad.”

SHANIA TWAIN

“Any Man of Mine” (1995)

“There’s so much empowerment in this song, especially when it comes to never settling, and it’s true in relationships, in business and just with the people that you surround yourself with. There’s a standard there and hearing a woman say it is awesome. Watching her play it live last year when I opened up for her on tour was the craziest full-circle moment.”

TAYLOR SWIFT

“You’re Not Sorry” (2008)

“Taylor Swift has always been a huge inspiration to me. I love that she’s not afraid to be too specifc in her songwriting. This was the frst song that I ever learned on piano when I was about 13. Shortly after, I wrote my frst song on the piano; it was the start of me being an artist and my songwriting journey.”

In May, SonLam Nguyen won the Red Bull Dance Your Style National Final in Atlanta. As he prepares for the World Final in Mumbai, the dancer shares his secret to a winning mindset—powered by an unshakable calm.

In May, at the Red Bull Dance Your Style National Final in Atlanta, the audience crowned Nguyen the winner at the end of a ferce, bracket-style competition featuring 16 elite dancers from around the country.

When I first meet SonLam Nguyen on a humid, cloudy morning in Los Angeles, I’m sweaty, frazzled and over 30 minutes late. Having grossly underestimated how long it would take to retrieve my rental car from the hotel valet and then drive in increasingly frantic circles around a parking garage trying to find a spot, I’m now finally here, power-walking through the botanical gardens where I’m meeting him and a photo crew hired by The Red Bulletin. By the time I find them near a hillside of pink and white wildflowers, my heart is racing and my armpits are damp.

But then I meet SonLam. Wearing his tightly cropped hair and flowy windbreaker pants, he shakes my hand politely, exuding a monklike composure that’s impossible to stay freaked out around. As we walk to the next setting, he turns to me and his wife, Yasmin Kimberly Nguyen, who is here to support.

“Everything look good, guys?” he asks in a light Vietnamese accent. I immediately feel my nervous system revving down.

Lam, as his friends call him, is the reigning U.S. champion of Red Bull Dance Your Style, a unique event where dancers of all street styles—from hip-hop to house to popping and locking— battle one another through a bracket-style competition, with the audience choosing the winner of each round. This is the 29-yearold popper’s second time to win a Red Bull Dance Your Style event; he also won a regional qualifier in Oakland in 2022, during his first run at the series. This November, he’s heading to India to compete in the world championships in Mumbai.

It’s an unlikely outcome for a dancer who’s only lived in the U.S. since 2017 and who remains relatively unknown compared to other Red Bull Dance Your Style champions, with a modest 15K followers on Instagram. The shoot is mostly quiet as he flows from one pose to another, directing himself. At a wooden bench, he hooks his foot under the armrest and leans back, going horizontal, his gaze soft and serene. “Are you kidding me?” the photographer says aloud, snapping away. In front of a stand of bamboo, he tries one pose and then another unselfconsciously, then realizes

something is missing. “Can you put the music back on please?” he graciously asks Yasmin, who wears her brown hair in a voluminous ponytail, her dimpled smile framed by two long tendrils. Watching Lam, I’m intrigued. I want to know how this gentle personality wins not only battles but the hearts and minds of raucous street-dancing audiences. I’ll soon learn that, in addition to obvious talent and discipline, Lam’s understated surface belies another secret weapon: an inner tranquility that’s been forged and honed like a sword.

After the shoot, Lam, Yasmin and I walk a few blocks to lunch. On the way, we chat easily about strength training (he just got a personal coach), yoga and cold plunging. For several years Lam has been practicing Wim Hof’s methods of breathing and cold exposure via daily cold showers. But recently, he began taking ice baths. In February, he sat in a freezing river in Aspen, Colorado, surrounded by snow. He’s also taken it too far: Once he stayed submerged in ice for 20 minutes, then got sick afterward, nauseated and shivering nonstop. “That’s when I realized my mind was stronger than my body,” he says. Now he does 10 minutes max. But he enjoys finding his limits.

Lam was born in a large family, the baby brother of two older sisters. His mom’s siblings and parents also lived with the family, about 20 people in total all under the same roof of a large house in the center of Saigon. He grew up surrounded by his uncles, aunts, grandmothers and cousins, and he was a good kid, rarely in trouble. At 15, he watched the Jabbawockeez win America’s Best Dance Crew and became obsessed with dancing, learning through YouTube videos. Soon, a reputed local crew invited him to join them. “But I said no, I want to be in a crew that’s not famous,” he says. Like in the movies, “I wanted to start from the ground up.”

Lam was drawn to another local dance outfit called X Clown Crew, which was brand new. “They said we’re going to be the first professional street-dance crew. No cursing, drinking or smoking,”

Nguyen’s secret weapon is an inner tranquility that’s been honed like a sword. He has a goofy side, too.

he recalls. “And we’re going to practice hard, like athletes.” This approach resonated with Lam, even at his young age. His mentors in X Clown Crew instilled in him the value of preparation, one he still holds to this day. “The battle is already happening, now,” he says. “[Mumbai] is happening now.”

Lam won dance competitions in Asia in his teens. At 19 he got his big break, winning his country’s edition of So You Think You Can Dance. After that, people recognized him on the street. But he didn’t feel like he was being himself. He felt creatively underdeveloped. On the show, he simply completed challenges; he didn’t yet have his own voice or style. He wanted to go somewhere where no one knew who he was, where he could isolate and dive deep into freestyle, without being subject to anyone’s expectations.

“When I get comfortable,” he says, “I tend to do something harder.”

In 2017, Lam moved to the U.S., landing in the Southern California city of Lawndale and studying dance at a local community college. The goofy young man from Vietnam became shy and quiet, shut off from much of the world by a cultural and linguistic barrier. He didn’t get why people laughed about certain things. He wasn’t always able to convey humor himself.

But Lam had come to the U.S. to learn and to grow. One of his core beliefs is that adversity makes you a better person.

“I don’t really fit the mold of what people envision as a street dancer.”

He bought an old bike and rode it in all conditions, choosing a heavier rig on purpose to make the task harder. He relished the rain especially—pedaling through a downpour, he imagined that he was the protagonist of a movie, like Rocky Balboa. “It was so exciting,” he says. “Every time the hardship came, I was like, OK, let’s go. I’m the main character. Let’s go through this.” He laughs when he tells me this, knowing it sounds ridiculous. Lam has perhaps my favorite combination of personality traits: He’s cerebral and idealistic, without taking himself too seriously.

Thousands of miles from his mentors and his family, the people who unconditionally supported him, he had to learn to support himself. In the U.S., he says, “I’m my own coach. I have to be a better friend to myself, a better coach to myself.” He started journaling, writing down his thoughts, almost a way of having dialogue with himself.

He talked to himself during competitions, too—if a song came on that he didn’t know, which happened often because he didn’t grow up with American music, he wouldn’t say, I’ve never heard this song, how can I do it? He’d say, Let’s play, I love this. He assembled a library of role models in his head—his mom, his best friend from his crew in Vietnam—and he pulled them down from the shelf like favorite books, whenever he needed their strength and love.

His second semester at the community college, he went to a dance audition. During the audition another dancer took a fall, but Lam improvised, helping her up and incorporating it into the routine. The improv impressed the choreographer, another student. She asked a friend, Who is that guy? The friend said, “He’s from Vietnam. He’s so good, but he doesn’t talk to anyone— he just comes to school, dances and then leaves.” The choreographer decided she would talk to him.

Lam had noticed this classmate a few days earlier, laughing with her friends. She dressed in baggy sweats and big T-shirts, no makeup, hair in a messy bun, but she was beautiful. Her name was Yasmin.

Yasmin and Lam started hanging out every day. “I brought him out a lot,” Yasmin recalls. “I’d tell my friends, he’s funny!” And he was. Lam might deploy fewer words than everyone else, but he could make them count. He had a knack for dropping deadpan punchlines that got the group rolling.

Lam is grateful for some of the harder, more isolating experiences of those early days. They made him more empathetic, for one thing. Not everyone was welcoming to him at events, though they got nicer when he started winning. Now when he walks into a room and sees new people in a corner, he goes out of his way to say hello. “I wish somebody would have come up to me,” he says. “So I’ll be that person for them.”

Lam is remarkably, disarmingly open. We sit down for lunch at an airy, upscale restaurant in the courtyard of a museum, and he tells me that the botanical garden was a very appropriate location for the shoot. “It fits me,” he says. He takes inspiration from various sources, including nature, and an urban setting wouldn’t have felt authentic. “I don’t really fit the mold of what people envision as a street dancer,” he says.

I ask what he means by that. Seemingly referring to feedback he’s either received or perceived, he tells me that sometimes, people think “maybe you don’t do that move as street, or as raw, or it doesn’t bring that dirtiness.” He continues, “Sometimes I feel out of place, you know? As a person who immigrated from Vietnam to here, a lot of things I’m not knowing.” Even in rap music, he doesn’t always understand the slang or lyrics. He connects instead with the visuals and movement the music inspires.

But the first principle of street dance, he believes, is that you have to be yourself. During his earlier years, he felt like he was wearing a mask. “I think the first step of learning something is that you really want to be a good imitator,” he says. “You want to fit in and do things right. But after you dance for a long time, you start to want to be comfortable with what you do and look in the eyes of people you love and say this is me completely.”

In the U.S., with so much time spent in solitude, Lam became deeply acquainted with who he was. For a class, he mixed a Jaden Smith song with a Vietnamese song and performed a solo, meant to convey the feeling of being an international student in the U.S. His teacher cried. Lam was struck that he’d moved her so deeply. After that, he told himself, “Just keep doing things that align with you, that are honest.”

Over the years, he’s gained more courage to dance in the way only he can: by infusing his popping foundation with other disciplines, like contemporary and modern. His style includes theatrical flair, as he often conveys emotions through his facial expressions, too. The more authentic he is, the more people respond. “The audience likes to see somebody being themselves.”

To be clear, Lam is also crazy talented, with superhuman mobility. “He’s made of rubber,” says friend and mentor Jordan McLoughlin, 36, who also comes from popping and

“He’s able to move with energy and harness it in a really beautiful way.”

“He’s made of rubber,” says friend and mentor Jordan McLoughlin.

“His body can twist and fing itself in ways I’ll never touch.”

teaches and competes. “His body can twist and fling itself in ways I’ll never touch.”

He continues, “He can move with energy, but a lot of people, when they try to apply that energy, they lose control and things get sloppy. But he’s able to harness that in a really beautiful way.” McLoughlin, who met Lam in 2017 and has trained with him over the past several years, has watched his friend grow and evolve, soaking up new influences in L.A., but balancing those infusions with fidelity to his roots. “I’d say in the last couple years he has reestablished a sense of responsibility to adequately express his popping foundation,” McLoughlin says.

In 2022, Lam got the call-up to the first Red Bull Dance Your Style Regional Qualifier in Oakland. He was ecstatic. “I made the list!” he tells me of his reaction. “Like, ‘I made it mom!’ I was so happy.” The next three months he trained hard. He and Yasmin had transferred to San Francisco State to complete their bachelor’s degrees, and they lived close to Golden Gate Park. Lam would wake up at 5:30 a.m., take a cold shower (“freezing!” Yasmin interjects), go to the gym, lift weights for two hours while Yasmin was still asleep, come home, eat breakfast with her, go to school, take dance classes, come home, do homework and repeat. “That was a beautiful time,” he says.

During intensive training blocks such as this one, Lam keeps what he calls a personal scoring system. He carries his journals everywhere, and now he pulls a spiral-bound notebook out of his backpack to show me exactly how his system works. He scores himself daily for hitting certain goals, like meditating or journaling, as well as three main categories of dance-related training goals: physical conditioning, technique and creativity. If he completes a task—a workout, for example—he gets a point. Each month he has a total points goal; say, 30 points. That way, if he has a slow day where he only scores three points, he can make up for it on another day with five. “I like to feel like I’m achieving before I step into a competition,” he says. If he surpasses his monthly goal, “I get an A+.”

Lam’s system fills him with confidence. By the time he arrived at the competition in Oakland, he tells me, he felt like he had already won. And then when he actually won, he thought, “I put in the work.”

Generally speaking, there are two types of goals: outcome goals, which are based on results, such as “Win the competition.” And process goals, which are structured around the steps one needs to take to achieve a result, such as “Train an hour daily until the competition.” Outcome goals are often partly dependent upon factors outside of one’s control, while process goals are almost

always based upon actions one can choose to take. Research has determined that setting process goals tends to improve athletic performance more than results-oriented goals; they do more to increase an athlete’s sense of self-efficacy (the feeling that one has agency over outcomes), decrease their anxiety and boost their motivation.

When I tell Lam about the concept of process goals, he lights up. “This makes sense!”

It is Lam’s instinct to control the controllables. Two years ago, when he competed at the 2022 Red Bull Dance Your Style National Final in New Orleans, just a couple of weeks after his victory in Oakland, he lost in the final round to David “The Crown” Stalter Jr., a Red Bull Dance Your Style world champion finalist from Minneapolis. Lam’s physical stamina failed him, he tells me: His mind wanted to keep going, but his body gave up. Meanwhile, he noted, his opponent had “a full tank.”

It was a valuable lesson learned. After that he put himself in uncomfortable situations in order to build endurance in both body and mind. Thus began the ice baths and more physical conditioning. He used to find the infamous seven-minute bus fight scene from the film Nobody difficult to watch (it was so violent it made him lightheaded), so he forced himself to watch it again and again. He and McLoughlin ran 45-second sprints up stair sets to mimic the intensity of 45-second battle rounds. They did a session where they didn’t break eye contact for 10 minutes straight (“extremely uncomfortable,” McLoughlin says), because being able to stare down your opponent while maintaining flow is a valuable battle skill.

The benefit of chasing process-oriented goals is that regardless of the outcome, you will feel like you achieved something. This is true, of course, not only in sports. In life, we can only control our actions and our effort. But if you do the work, Lam knows, you can be proud, whether you win the battle or not.

On the morning of the 2024 Red Bull Dance Your Style National Final in Atlanta in May, Lam woke with intention. He wanted to carry calmness throughout the day, so when he got out of bed he moved slowly: He got some sunlight on his eyes, did some stretching and mobility; he didn’t look at his phone. He drew a picture of himself in his notebook, visualizing his intentions for the night: a stick figure with a spiral over its shoulder (“circles are endless, so when you get stuck, circular motions”), an explosion for a hand (“in popping we have the idea of the pop, like a rocket exploding”) and muscular legs (“my strongest body part are my legs”).

“It fts me,” Nguyen says of the botanical garden setting. With his art form, he takes inspiration from various sources, including nature.

When the organizers allowed the dancers to come out to the stage, he examined every corner of the platform. He wanted the area to feel familiar to him, like home. He walked up to the speaker and said, “Hello, speaker.” He sat in various seats to see how the audience would see him. He lay on the floor and thought, This is my home. He walked around the event space in search of shy-looking people and shook their hands, thanking them for coming.

Near the beginning of the night, it rained, putting the outdoor competition on hold. The contestants got cold and stressed. The energy plummeted. Lam told himself, I love it. If they tell us to dance in the rain, I’m ready. When the competition finally resumed, he tried to treat each battle like it was the final. The slippery floor got in his head a bit, but he could see that everyone had to deal with the same conditions. During the final round, he was in the zone. Before the audience even raised their wristbands for the vote—red for his competitor, blue for Lam—he already knew the result.

The lights dimmed. He looked around. A sea of blue circles glowed in the dark.

“I think we need more examples of people in a competitive space,” Jordan McLoughlin says, “for whom humility is a weapon.” Lam, he says, is fundamentally humble, a quality that facilitates his success by keeping him open to learning. But McLoughlin calls it an “advanced humility.” “It’s not just that he’s nice,” he says. “His humility is a weapon.” He explains: “It’d be very easy to be as talented as he is and think ‘I got this.’ I don’t need to take in more information. But on the flip side of that, if you’re too open to new perspectives and you have no sense of self, that will lead you to be watered down.” Lam knows his worth, and that allows him to grow without losing who he is. That worth comes from a deep well of confidence, one earned by ticking off the small, stepwise goals each day—and knowing the results will follow.

When Lam won in Atlanta, he danced on stage with a friend, the two smiling and hugging. But when he went home, he did what he always does. He sat in his room alone. He asked if he was happy with himself, if he felt aligned. He wrote down his thoughts in his journal. He thought, This is a big deal, but it’s just a dot on my journey. I’ll keep climbing bigger and bigger mountains.

And he felt at peace.

WORDS BY RICHARD VILLEGAS ILLUSTRATIONS BY TIM MARRS

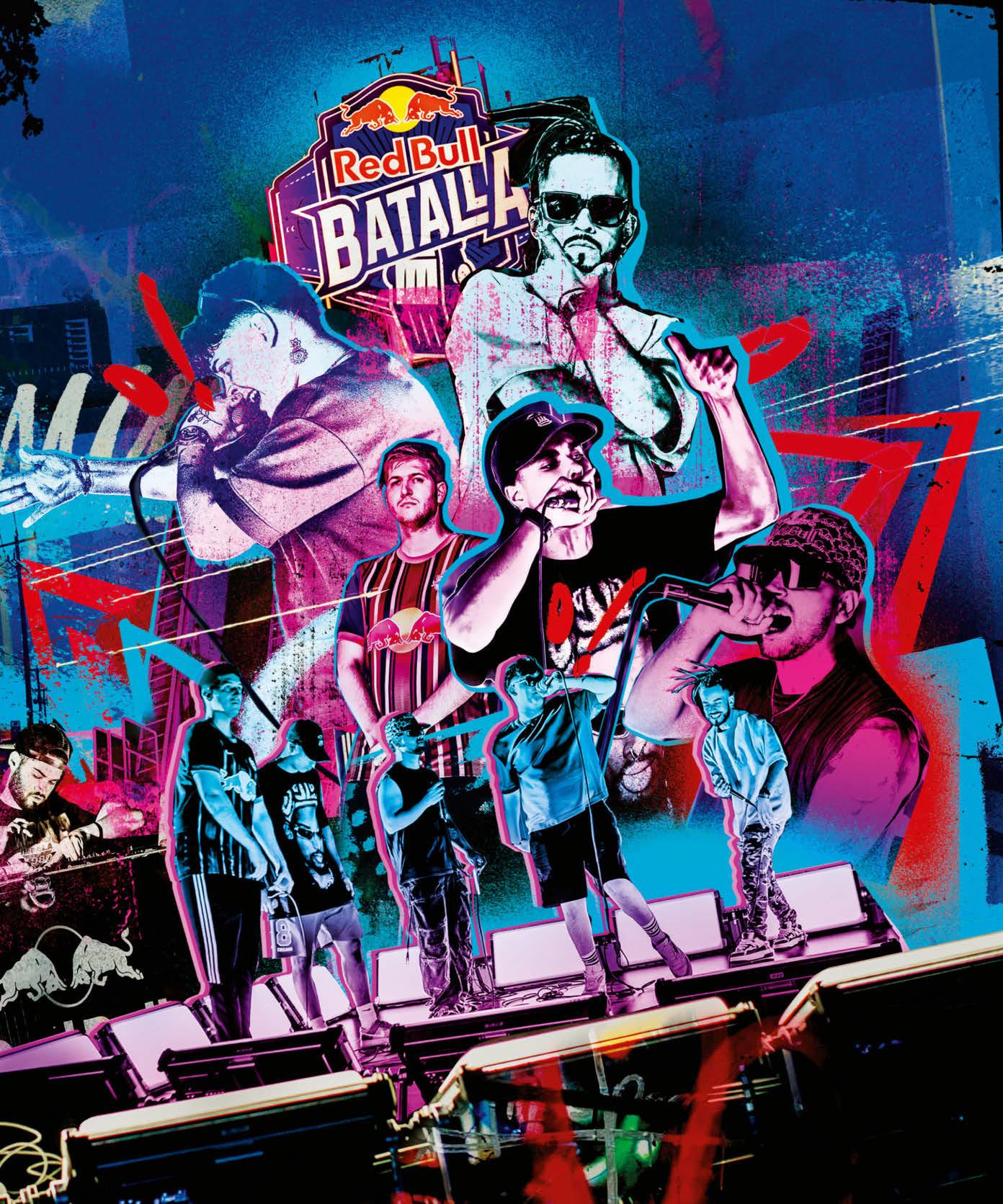

A coalition of MCs is leading the movement of Spanish freestyle rap in the U.S.—everywhere from city parks to Red Bull Batalla.

It’s September 2023, and the Texas heat is scorching. The sea of patrons at San Antonio’s Hemisfair Park is out in hats and shorts, with fully stocked coolers in tow.

Meanwhile, in a circle under the shade of an old tree, a group of rappers are duking it out—verbally—in the throes of a regional freestyle tournament put on by BDM (Batalla de Maestros). In this particular match, Argentine rapper and graffiti artist Zazo Wan is facing off against Mexican tongue twister Arian, spirited barbs flying and beads of sweat rolling down both their faces.

Two months later, a similar scene unfolds on stage at the Red Bull Batalla USA National Final in Dallas, where Zazo Wan is going up against Cuban rapper Reverse in the tournament’s heartpounding title match. This time, the MCs sweat under the high beams of the popular venue Gilley’s, surrounded by a crowd holding up flags from their respective countries, while beloved host Racso White Lion narrates the match with the heightened gusto of a soccer commentator. But the energy is palpably different. Gone is the laughter and collegiate casualness of the park, and instead each rapper is puffed up and red-faced, like bucks ready to lock horns to the death. Yes, there’s a trophy on the line, but digs about weight gain, betrayal among friends and drug abuse cut deep. Once the battle concludes, the exhausted MCs shake hands and clap for each other, followed by the announcement that Reverse has prevailed over his opponent, to roaring crowd approval. The tension that filled the room minutes ago dissipates into collective elation, capturing the thrill and fierce competitiveness fueling one of the fastest-growing art forms in the United States.

“You need to win on the stage and still hold your own in the park,” says Zazo Wan, zeroing in on the dichotomy between freestyle rap’s clandestine training grounds and the glitzy, cutthroat tournaments attracting legions of fans across the country. In less than a decade, a once-nebulous underground of Spanish-speaking MCs has grown into a nationwide movement with fertile enclaves in Miami, Los Angeles, Dallas and New York City. Trailblazing leagues such as Dioses de la City and Urban Rap Stars have generated buzz with stacked calendars and an organizational structure that pipelines promising local upstarts to national renown. For the artists—most of whom are Latin American immigrants—improvisation circles have also become

welcoming communities away from their ancestral homelands. Add to the mix viral rap battles unfolding at tournaments south of the border, plus a galvanized generation of wordsmiths eager to join the international conversation, and you have the makings of a zeitgeist-defining phenomenon. More often than not, that story begins in the park.

“Competing at Red Bull Batalla is the zenith of our industry and comes with unique prestige and opportunities, but you have to pay your dues locally as well,” adds Zazo Wan, who emigrated from the mountain city of Mendoza, Argentina, to the sprawl of Dallas in 2019. “It’s important to hone your reputation in the circuit, because sustaining a long-lasting career requires building relationships with your colleagues. Sometimes it’s not even about competing. Just show up to the park, hang out and exchange bars with friends. Being present and participating keeps the culture moving.”

Freestyle culture has been in motion for quite some time. After all, it’s a discipline predicated on ingenuity rather than budget and academic access, which in turn creates a universally leveled playing field. It’s one of the five elements of hip-hop alongside DJing, graffiti, breaking and the oral histories crucial to the movement’s survival. Since hip-hop was born in the Bronx in the mid-1970s, the borough’s vibrant Puerto Rican diaspora brought these buzzy new forms of songwriting and storytelling back to the island, which quickly proliferated across the Spanishspeaking world.

It makes sense that in 2005, Puerto Rico hosted the first international edition of Red Bull Batalla at San Juan’s iconic Club Gallístico, the cockfighting coliseum that would inspire the tournament’s avian branding for years to come. In its maiden voyage, the competition drew buzzy MCs from all over the Americas and Spain, anointing Argentine rapper Frescolate as the series’s first world champion and renewing excitement among the Ibero-American hip-hop community. A tidal wave of tournaments followed—Freestyle Master Series in Spain, El Quinto Escalón in Argentina, Supremacía MC in Peru and BDM in Chile—supercharging the battle scene and fostering some of the greatest talents to ever hold a mic.

“You need to win on stage and still hold your own in the park. It’s important to hone your reputation in the circuit, because sustaining a long career requires building relationships.”

Red Bull Batalla also continued to hold its annual jousts, constantly bouncing between various host nations and with only a brief hiatus in 2010 and 2011. However, the tournament would not return to the United States until 2019, when it took over Miami’s Wynwood Factory and drew more than 2,000 attendees. Defeating Mexican rapper Jordi in a riveting duel packed with boom bap and old school reggaeton beats, Boricua rapper Yartzi emerged as the first champion of the organization’s newly minted national chapter. But don’t mistake this homegrown triumph for the genesis of the U.S. Spanish freestyle scene, because in reality that win was the culmination of efforts that had begun long before.

“I pretty much created the Spanish-language rap battle circuit in the U.S.,” says an assertive Alfredo Molina, a.k.a Moha, founder of La Liga de la Calle in Los Angeles. Before arriving in California in 2013, the rapper and promoter would hold events called Garage Battles at his grandmother’s home in El Salvador. In L.A. he was met with a primarily English-speaking scene, and even though he occasionally took the stage in front of largely Black audiences, where he was positively received, the insurmountable language barrier dulled the punch of his bars. “I’d vent to my Mexican and Salvadoran friends that the scene here was dead,” he remembers, “and they’d reply, ‘Then we have to revive it.’ They looked to me as that game changer, so I pushed to start meeting [at Salt Lake Park] in 2016.”

Though La Liga de la Calle held its first competition the following year, word of how L.A. organized to form its own scene quickly spread on social media. Soon small crews in other cities launched leagues of their own: Liga Masacre in Houston, Dioses de la City in New York, the Match Freestyle in Chicago, Miami Freestyle League and Indigo FL in Orlando. The snowballing movement prompted the 2019 stateside revamp of Red Bull Batalla and brought in touring tournaments such as BDM, DEM Battles and Misión Hip Hop. And when the pandemic shutdown threatened to stunt the scene’s Herculean progress, online battles were folded into the new normal with ease. These strides have amounted to a rapidly industrializing freestyle infrastructure that did not exist at the top of the 2000s, built through the street-level work and consistency of local organizers.

“I believe the future lies in reinforcing regional circuits,” says Moises Santana Vidal, a.k.a. Green, who co-founded Dioses de la City alongside Dominican rapper El Dilema back in 2017. Since its inception, the league has focused on developing the Northeast circuit, tapping into vast, active hip-hop communities thriving in New York and New Jersey and seeing opportunity for growth in Connecticut. Green highlights distance as one of the biggest reasons the U.S. scene hasn’t fully broken through, since crosscountry travel expenses and time away from day jobs and family

pose the biggest challenges for MCs who are still on the come-up. To support competitors, his organization records all matches, producing videos that can be added to every rapper’s portfolio. Likewise, sponsorships and enrollment fees go toward awarding competitive monetary prizes, or even flights to out-of-state contests.

Though both founders of Dioses de la City hail from the Caribbean metropolis of Santo Domingo (the capital of the Dominican Republic), the pair transformed their personal passions for rap into a grassroots movement out of Queens, New York. Green recalls the first time El Dilema invited him to one of his “shows,” which turned out to be a cypher among friends on the corner of a local laundromat. Undeterred, they continued to meet, relocating to the verdant Flushing Meadows Corona Park with a growing roster of MCs. Soon they’d be partnering with BDM and Urban Rap Stars for regional events.

El Dilema diligently fought his way to the top of the country’s freestyle rankings, placing second at the 2020 Red Bull Batalla USA National Final. On the other hand, Green recognized that his lyrical chops wouldn’t cut it on stage, so he pivoted into organizing and judging. He’s since sat on panels at tournaments in Colombia, Peru and the U.S. and built relationships with freestyle leagues back in the Dominican Republic. But evaluating and comparing razor-sharp wits is only half the job when rappers on the stage hail from dizzyingly different backgrounds.

“Judges need to have broad cultural knowledge, since in the United States you’re dealing with people from many different countries, all in the same competition,” says Green. “New York is so diverse, with so many Mexicans, Central Americans and Caribbean people, that immersing yourself in these cultures is how you learn

to catch the terminology and references. Slang varies, and so do hot topics, so a judge needs to be aware of all of it.”

Scrolling deep through the archives of the Miami Freestyle League’s YouTube page, videos dating back to 2018 show groups of teenagers gathering at Downtown Doral Park, all fresh-faced and squeaky clean, as if plucked out of a wholesome afterschool special. But the bars are solid, and soon familiar faces begin to appear: Eckonn (third place at Red Bull Batalla USA 2021), Nico B (second place at Red Bull Batalla USA 2022) and Reverse (winner of Red Bull Batalla USA in 2021 and 2023). One especially cinematic clip from 2019 finds MCs Reverse, Huguito and Carlitos engaged in a nighttime battle underneath a jagged rock sculpture called “Micco,” created by Miami Beach contemporary artist Michele Oka Doner. Though Reverse easily bests his opponents, the segment is a strong example of the vibrant youthfulness that has elevated Miami as the new titan of U.S. freestyle.

Venezuelan visionary Sebastian Avendaño created the Miami Freestyle League when he was 16, inspired by the battle videos he would watch on social media with his high school friends. As Florida’s first Spanish-language league, its contests became a rite of passage for any local rapper worth their salt. Reverse would come down from West Palm Beach, while Red Bull Batalla USA 2022 winner Oner commuted from Tamarac. Both MCs were 19 the first time they won the national championship. Word of Avendaño’s growing organization crossed state lines, and eventually Red Bull Batalla tapped him for promotion and talent selection for the tournament’s fateful 2019 return. Amusingly enough, the same youthfulness that put him at the movement’s vanguard kept him from attending the event, since he was underage.

“As we grew up, so did the scene,” recalls Avendaño, noting how swelling numbers led to noise complaints, which drove the league out of the park and into enclosed venues that helped formalize their dealings. This year, however, Red Bull Batalla USA returns to South Florida and Avendaño will attend, representing DEM Battles, the meteoric Chilean league that merged with his own in 2022. The success of Miami’s freestyle scene has also dovetailed into the financial and cultural capital of parallel happenings like the Miami Grand Prix, Art Basel and III Points Music Festival, producing unique regional synergy drawing audiences and tastemakers eager to discover the next global trend.

“The arrival of Red Bull Batalla made people look at us differently,” says Avendaño, reflecting on Miami’s fortified reputation. “We’re no longer kids rapping in plazas, but rappers freestyling at important tournaments. Back when I started, a good date used to draw 15 or 20 guys, but my most recent event had 70 MCs and 300 spectators. We’ve even pulled heavyweight stars like Nicky Jam, Tiago PZK and Micro TDH, and I’m sure industry brass is also coming through looking to scout talent.”

Clearly, the next step for U.S. freestyle is to begin launching its own stars, which will require an active and disciplined social media presence and carefully selected labels and collaborators who can contribute to an MC’s growth. These are time-tested strategies; just look at how Duki, Trueno and WOS parlayed victories in Argentina’s iconic Quinto Escalón circuit into critically acclaimed, stadium-filling artistic careers. The same goes for Mexican FMS legends Aczino and Yoiker, who are celebrated among Spanish freestyle’s all-time greats. Both took the stage at the 2023 Red Bull Batalla World Final in Colombia, performing in front of a sold-out crowd of 14,000 people at Bogotá’s Movistar Arena. The event also marked the international debuts of Oner and Reverse; in fact, the most promising U.S. candidate for a crossover career is Reverse, who has already signed a record deal and begun teasing cuts from an upcoming, genre-voracious project.

“There are so many Latinos who love this scene and feel that because they’re away from home their shot has passed,” says Racso White Lion, one of U.S. freestyle’s most emblematic voices. Synonymous with Orlando’s powerhouse scene, the Venezuelan rapper and organizer co-founded Indigo FL alongside his business partner Scarface in 2020, frequently meeting off the lake shores of Eagle Nest Park. However, Racso shifted from competing to hosting the events, earning the moniker of Mr. Pasión for his electrifying stage presence and eventually becoming the de facto presenter at Red Bull Batalla USA.

Racso underscores that the audience holds more power than they know, able to turn the tides of a competition by getting behind a floundering MC, as well as supporting their career long after they’ve snatched a trophy. But for U.S. freestyle to transcend, the connection between audience and artist must be cultivated, as the art form evolves to accommodate new voices. Organizers would also be wise to encourage a larger presence of women at their competitions instead of relegating them to the sidelines. In 2019, Canary Islands rapper Sara Soca unleashed an impassioned diatribe against femicide while competing at a Red Bull Batalla tournament in Mexico, going viral and proving that women are an untapped market that could catalyze the movement’s next chapter. But again, that change needs to begin in the park.

“A lot of people have asked where we were, but we’ve been in the same plazas for eight years,” says an emotional Racso. “It’s been a matter of getting the word out and making noise, and now that we’re reaching more people, they know we’re here to stay. Forever.”

“We’re no longer kids rapping in plazas, but rappers freestyling at important tournaments.”

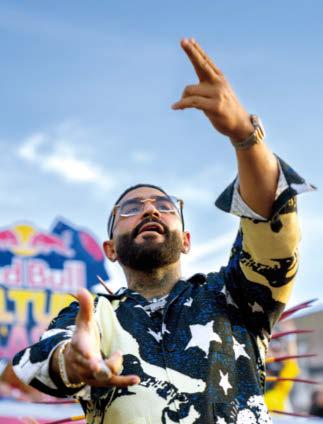

In Greenpoint, Brooklyn, the crowd blasts air horns to show their support at Red Bull Culture Clash, where the audience decides which crew will win the boisterous music competition.

ven in New York City, it’s not every day that you can immerse yourself in a sea of iridescent revelers clapping for death drops in front of the biggest sound system imaginable. Or hear a performer laying down a blistering solo on an amplified erhu, the two-stringed instrument popular in Chinese folk music. Or witness famed rapper and producer Wyclef Jean and Joshua Nesta “YG” Marley dub

Whitney Houston B sides while the guy next to you blasts an air horn strapped to a power drill to show his support. These are just a few of the unexpected scenarios one can expect to encounter at Red Bull Culture Clash. With more than 200 languages spoken across its five boroughs, NYC is the quintessential melting pot of culture, and the locals know how to throw a parade that showcases this diversity. The city hosts

around 60 parades a year—about five each month— drawing millions of spectators. This tradition, which dates back to the American Revolution, has evolved to become a grand celebration of processions that fuse historical charm with modern panache.

Bringing these dynamic parades together in a unique competition, Red Bull Culture Clash salutes the diversity and energy that make New York City truly special. Four teams, each repping a different

cultural parade—Lunar New Year, Pride, Puerto Rican Day Parade and West Indian Day Parade— come together and face off over four rounds to bring the noise and claim the crown.

Returning for the first time since 2022, this year’s epic showdown on June 1 in Brooklyn turned up the heat by merging the energy of New York’s finest dance and DJ crews with the essence of each parade. Here’s a look at the highlights.

Kicking off Red Bull Culture Clash and repping the NYC Pride Parade was Papi Juice, an LGBTQIA+ art collective celebrating queer and trans people of color. During the performance, queer-coded iridescent folding fans were dispersed to the crowd, who enthusiastically clapped along to a soundtrack of club-mix favorites like Nicki Minaj and Beyoncé. Backup dancers held up signs saying “For Sylvia” and “For Marsha,” in honor of activists Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson, while multihyphenate performers like DJ Mazurbate, Maya Margarita and drag legend Essa Noche all came to “werk.”

Asian media platform Eastern Standard Times gathered a powerhouse crew that came full force to represent New York’s Lunar New Year Parade. Hitmakers like Bohan Phoenix, Jay Park, Sunkis and Slayrizz brought the culture while backed by dancing dragons; musician Chiiwings, of the cybermetal quartet P.H.0., stunned the crowd with her incredible erhu solo; and R&B star Pink Sweat$ turned up to show his support.

The culture that brought us Tito Puente, Rita Moreno, Fat Joe, Bad Bunny and one of New York City’s biggest—and loudest—parades did not disappoint.

Alternative Latin media outlet

Remezcla delivered a distinctively Nuyorican flavor, including spots from duo Nina Sky, rapper J.I. the Prince of N.Y., DJ Bembona and Christian Martir with Capicu!

Legendary Latin Grammy–winning choreographer Violeta Galagarza was also on hand to usher in the next generation of Nuyorican dancers.

Modern urban parades and carnivals owe much of their roots to Jamaican/Caribbean sound system culture, making the act by collective No Long Talk a tough one to beat. Just like the West Indian Day Parade on Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn, the stage featured a huge replica of a semi truck with dancers in full Carnival attire. While the crew blasted everything from reggae and dub to a Michael Jackson remix, No Long Talk’s secret weapon turned out to be a cameo from Wyclef Jean and Joshua Nesta “YG” Marley, helping this fan favorite to rightfully snatch the Red Bull Culture Clash crown, as yellow streamers exploded in the sky.

rts watersports watersports watersports watersports

rts watersports watersports watersports watersports

rts watersports watersports

This story, like the legend’s life story, will begin and end in a high-powered towboat barreling toward the horizon. Let’s set it in Central Florida—at a lake with warm water ringed by cypress trees and blanketed by a heavy blue sky. This is the universe our hero was born into and the one he will inhabit until his heart stops beating.

Parks Bonifay is piloting a throaty MasterCraft XT22 on a June afternoon on Lake Minnehaha, 30 miles west of Orlando. His corgi, Pardi, is curled at his feet. His fiancée, Paige, and his mother, Betty, sit near the stern, staring at water and sky with the tranquil faces of people with experience meditating on boats.

You might ask why the story of a man who arguably is the greatest wakeboarder of all time doesn’t open with hyped-up action. After all, Bonifay has won world championships with jumps and grinds that stretch the boundaries of physics and human potential. He has been towed by helicopters and a Formula 1 race car.

selling juice cleanses and Instagram fantasies, but with Bonifay we’re talking about an actual way of life.