TRICKS OF THE TRADE

BIKE SPRING COLLECTION

Yushy

“I felt lucky to document UK and South Asian cultures naturally colliding,” says the British Indian photographer who shot Mumbai hip hop crew Swadesi. “Hearing classic grime reimagined in the local language was eye-opening - their stories mirror those told in the UK.”

Jessica Holland

The London-based freelance writer gravitates towards inspirational people, which made horticulturalist/ skater Danni Gallacher the ideal interviewee. “Talking to her was inspiring,” says Holland. “I love that she’s combined her passions to create a totally new path.”

Matt Blake

The British journalist and author of the book Hearth of Darkness (out in October) met up with BMX ace Kieran Reilly. “Seeing him fly off ramps made me think of the bike scene in ET. His control feels almost supernatural.”

From the ruins of a 16th-century Irish castle to Europe’s largest skatepark, the peak of Nepal’s Annapurna to a backstreet nightclub in Mumbai, this month’s issue features contrasting locations all populated by people pushing their limits.

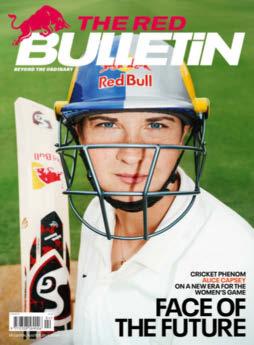

Our cover star Kieran Reilly has been glued to his bike since the age of eight, and it shows. The 23-year-old is at the forefront of freestyle BMX, landing world firsts and taking major titles. We find out how he does what most riders can only dream of. We also meet India’s Swadesi, a hip hop collective bringing dubstep, grime and reggae to a new audience, to tell important stories to the rhythm of floor-shaking bass. And we enter the sport of competitive cliff diving, where the world’s most fearless divers hurl themselves seawards in the hope of emerging victorious. Enjoy the issue.

shrine

With grit, athleticism and flair – the triple flair, to be precise – the Gatesheadborn rider is pushing the limits of freestyle BMX

Dropping science with the 2024 cohort of this heartpumping, jaw-slackening, globetrotting spectacle

The record-breaking mountaineer talks mental edge, the value of fear and the euphoria of summiting

Swadesi, the rap collective shaking up India’s club scene with their incisive lyrics and inclusive door prices

LEGENDS NEVER TAKE THE EASY WAY.

The next evolution of all-terrain tires is here. The BFGoodrich® All-Terrain T/A® KO3 tire raises the bar in toughness and durability. Again. Designed to do it all, the KO3 tire has better wear performance than the KO2 tire, the excellent sidewall toughness you’ve come to expect, and is made to grip, even in the worst of conditions. Legends are written in dirt. It’s time to write yours.

KYLE STRAIT

Saalbach, Austria

Supersize me

Like popcorn tubs at the cinema, slalom skiing comes in various sizes: slalom, giant slalom, super giant slalom, even combined (if you like sweet and salty). When Marco Odermatt lined up at the 2025 Alpine Ski World Championships in February, the Swiss ski racer eyed one of the few titles that had eluded him thus far: Super-G world champ. Two days after the training run pictured, Odermatt took the crown, beating runner-up Raphael Haaser by a whole second. Mega XL giant slalom can’t be invented soon enough… redbull.com

Dublin, Ireland

Break cover

Sneakerheads will go to any lengths to keep their new kicks box-fresh. Here, we see the One-Handed Puddle Guard – a deterrent against pavement tsunamis triggered by passing cars. Best of all, it doubles as a breaking move. The Red Bull BC One Ireland Cypher at Dublin’s Button Factory in February had competitors dreaming of a place at this year’s World Final. And it was B-boy Aleon and B-girl Tara who won the right to fly the tricolour in Tokyo this November. Hey, don’t forget the Miso Splash Grip, guys… redbull.com

Abu Dhabi, UAE Making waves

The meticulously manicured and – some might argue – culturally barren city of Abu Dhabi may lack the laid-back, inclusive vibe of South Africa’s J-Bay or O‘ahu’s North Shore, but surfing can be found if you know where to look. Hudayriyat Island is home to Surf Abu Dhabi, marketed as the world’s best and most advanced artificial wave facility. This February, it hosted the World Surf League Championship Tour for the first time, and at this inaugural event reigning champ Caitlin Simmers (pictured) from California rode to victory. redbull.com

North Island, Aotearoa

Urge to surge

At Tree Trunk Gorge in New Zealand’s Kaimanawa Forest Park, it’s not only the tree trucks that are gorge – the canyon’s weathered banks and fierce whitewater are magical to France’s Nouria Newman (pictured). No water is too wild for the kayaking ace: in 2021, she broke records with her 31.69m descent of a waterfall in Ecuador. Newman is just one of many inspirational athletes – including big-wave surfer Andrew Cotton and ski explorer Preet Chandri – who tell their story of breaking boundaries and achieving the seemingly impossible in season three of the How to Be Superhuman podcast. Listen on your favourite podcasting app, or go to redbull.com/superhuman

Run beyond your best

Bartees Strange Outside the box

The eclectic American musician shares four tracks that helped him dare to be diferent

US singer/guitarist Bartees Cox Jr – aka Bartees Strange – was born in Ipswich, Suffolk, thanks to his Air Force engineer father who, joined by Strange’s operasinging mother, was stationed in the UK at the time. But Mustang, Oklahoma, was where he grew up, a nerdy Black teen who identified as bisexual, rebelled against rural conservatism and loved hardcore bands. He ended up playing in several of these bands while pursuing other day jobs, which included the role of deputy press secretary in the Obama administration. With more time on his hands during lockdown, in 2020 Strange released his debut album Live Forever; its unique blend of punk, hip hop and jazz earned him fans among critics and peers alike. Here, the 36-year-old picks four tracks that demonstrated he could choose his own individual path… Bartees Strange’s latest album, Horror, is out now; barteesstrange.com

At the Drive-In One Armed Scissor (2000)

“In the early 2000s, there was no better band in the entire world. They played a small show in Oklahoma City when I was a kid. They walked in and spoke Spanish the entire time – kind of a ‘fuck you’ to us kids from a white, conservative town. But One Armed Scissor was so good. I think it’s sick to do whatever the hell you want to do.”

Funkadelic Hit It and Quit It (1971)

“Something about this is so country, so pop and so folkyfeeling. It’s a crazy blend, unlike anything I’ve ever heard. Funkadelic made me feel like you can do whatever you want, because they didn’t confine themselves to just one sound. George [Clinton, the band’s leader] blends it so well, and I always wanted to be an artist like that.”

Bloc Party Helicopter (2004)

“I was in eight or ninth grade when I fell in love with this band. One, it’s an amazing song; two, I don’t think I’d seen a Black indie-rock band, ever. I was like, ‘Holy shit, this is so fast and so good, and the playing is so great.’ It’s such a clearly beautiful and huge song, it just really grabbed me. I wanted to play songs like it.”

TV on the Radio Wolf Like Me (2006)

“When I heard this song, it was like my whole spirit came alive: ‘Oh God, that’s me. That’s what I want to be when I grow up.’ It put this thought in my head that I could make music for a living, even though I had no idea what I was doing with it. I owe them a debt of gratitude for singlehandedly changing what I wanted to do with my life.”

The Poetry Pharmacy

Nurse of verse

If you’re feeling anxious, indecisive or merely in need of a pick-me-up, Deb Alma can prescribe a personalised supplement you may not have considered: poetry

When people complain to Deb Alma of a broken heart, she points them towards the poem Love After Love by late Saint Lucian poet Derek Walcott, which reassures its reader, “You will love again the stranger who was your self.”

“The poem talks about living your own rich and interesting life,” says Alma. “Being in love with your own life, which is a wise thing to do.” Her remedy draws from personal experience: when she was heartbroken, Alma stuck Walcott’s poem on her fridge, and over the years she has given copies to friends in the same situation.

The 60-year-old believes so passionately in the power of poetry to help navigate

difficult periods in life that she has founded the world’s first poetry-based chemists, prescribing poems to soothe customers’ emotional ailments – from existential angst to indecision to writer’s block.

The Poetry Pharmacy opened in the small market town of Bishop’s Castle, Shropshire, on National Poetry Day 2019; it was joined by a second branch, in the Lush Spa on London’s Oxford Street, in June last year. “I think poetry, more than any other art, speaks very intimately, as though from one person to another,” explains Alma. “[It tells us] that somebody has been there before you and has come through it. In the poems we prescribe,

Rhyme is a healer: (from top) Deb Alma at her Poetry Pharmacy in Bishop’s Castle; Poemcetamol – always read the label… and the pill itself

there’s always a positive outcome; they’re not poems where someone’s writing in the middle of their despair. I think it was William Wordsworth who described poetry as ‘emotion recollected in tranquillity’.”

The pharmacies are actually the second iteration of Alma’s service providing poetic tonics to those in need: for several years, she drove a vintage ambulance to festivals around the UK, offering support as ‘the Emergency Poet’. Now, her bricks-andmortar stores sell tiny vials of poetry ‘pills’ to counteract ‘Dithering’ or offer a ‘Boost of Confidence’, and books are arranged according to theme rather than alphabetically, which encourages customers to browse intuitively, searching for verses that match their mood or requirements at that specific time. “We get questions like, ‘My friend’s just been diagnosed with an illness – what poetry might help her?’” says Alma, whose background is in bookselling and working with people with sight loss and dementia.

Now a published poet, Alma is currently editing eight poetry anthologies that correspond to the pharmacies’ book sections, including Love, Comfort, First Aid and Wild Remedies. For First Aid, Alma says, “the idea is that you need something, but you don’t quite know what it is –something that’ll just lift your spirits,” while Wild Remedies poems are reminders to stay grounded, such as WB Yeats’ The Lake Isle of Innisfree. And although Alma primarily deals with emotional ailments, she does suggest a poem that might even help with the common cold: The Word by late American poet Tony Hoagland. “It’s a little drop of sunlight [for] people who are not looking after themselves properly, for those who are too busy and just need to stop for a minute,” she says. poetrypharmacy.co.uk

Change of art

By manipulating classic works, artist Volker Hermes adds humour to the sometimes po-faced world of portraiture, giving us a history lesson in the process

In one painting, a 17th-century Dutchman peeks out from beneath frothy layers of white lace that almost completely overwhelm him. Another work shows a young woman from the same period, her forehead and ringlet curls visible but the rest of her features wrapped in teal silk and scarlet ribbon like a birthday present.

These aren’t the original paintings but rather reworkings – of Michiel Jansz van Mierevelt’s Portrait of a Man in a White Frill (c1620s) and Jan de Brays’ Portrait of a Young Woman (1667) respectively – by German artist Volker Hermes.

Since 2007, Hermes has been using digital manipulation to transform portraits from the early 16th to mid-19th centuries. “I really try to keep the original spirit of these paintings,” the 52-year-old Dusseldorf-based artist says of his Hidden Portraits project, “because I don’t want to destroy these historical works – I love them! Nevertheless, I think we can change our perception of them.”

The project was born from Hermes’ reflections on the way contemporary audiences interact with historical works – paintings in which fashion,

Fresh look: (clockwise from top left) Hidden Anonymous (Don Juan), Hidden Gower, Hidden Perronneau III, Hidden Anonymous (Pourbus IV); (above) Volker Hermes

poses and props have been carefully chosen to convey messages about the social conventions of the day, and the status of the subject.

“I recognised that our focus is mostly on the face, because we don’t know all these allusions and metaphors and symbols any more,” says Hermes, a trained painter. “I felt it was disappointing to lose all this major information that shows us so much about these societies.”

Self-taught in Photoshop, Hermes trawls the openaccess archives of museums then uses digital manipulation to reimagine the portraits, exaggerating and playing with elements to draw attention to details that viewers might otherwise miss. Hermes prefers to find unknown works rather than use famous pieces by the likes of Rubens, he says. And he adds nothing new to them, only manipulating elements that already exist.

Hermes’ tongue-in-cheek approach has proven popular among art fans – so much so that last September he published a book compiling his works, Hidden Portraits: Old Masters Reimagined Whether it’s a gentleman whose jacket, buttoned up to the top of his head, looks as if it has swallowed him, or a gentlewoman encased in a brocade mask that resembles a motorcycle helmet, Hermes believes that injecting these historical works with a sense of humour both illuminates their often ludicrous opulence and encourages viewers to consider them in a new light.

“The huge danger is that I’m getting too didactic,” he admits. “It’s this teacher thing in me. And if you’re raising your finger and telling people, ‘You should know this,’ it’s not very useful. Humour is a sharp knife, and you can point to things very, very fast. You can take power apart in a second.” hermes.art

Hidden Portraits

When naming his new fitnesstech product, startup CEO Léo Desrumaux was inspired by the involuntary noise people made when they used it. “It just kicks your ass!” he says of his smart punch bag, Growl. Using a combination of projectors, sensors and cameras, the device generates a life-size, AI-powered trainer that replicates the experience of boxing with a real coach.

“Our starting point was to recreate one-on-one coaching,” says Desrumaux, who’s based in Austin, Texas. “How do you build a punch bag that replicates that physical presence?” Growl doesn’t look much like a traditional boxing bag: although still made from foam and leather, it’s an elliptical, wall-mounted, mattress-like structure. But it’s the frame containing the technology that its co-creator – with business partner Nicolas de Maubeuge – hopes will revolutionise at-home combat training.

Desrumaux discovered boxing after being kicked out of school in Paris at 16 and moving to the US as a foreign exchange student. Speaking very little English, he joined his high-school wrestling team and then an MMA and boxing club. “It did two beautiful things,” he says. “I discovered I wasn’t made out of glass, and I learnt the discipline, the drive, the ferocity, the competitiveness and just the sheer resilience required to execute your potential.”

He entered a career in private equity investment, but an interest in “connected fitness”, along with his love of boxing, sparked the idea for Growl: “If I wanted to reach my potential in boxing, I needed to make the bag into a coach.”

Specifically, Desrumaux wants to replicate the way a trainer works against you, setting a pace you must match, pushing your limits. Growl’s 4K high-brightness projectors present the life-size image of

Hitting

This AI-powered punch bag ofers all the benefts of boxing with a real-life coach, minus the perils of setting foot in the ring

a trainer on the bag, and timeof-flight, infrared sensors shoot lasers down its surface. When a punch breaks a beam, the technology interprets its power, speed and accuracy.

A multi-angle camera system captures images of the user’s body in real time. “We can recreate your body’s joints in a 3D space,” Desrumaux says. “Do you keep your guard up when you’re throwing a cross? Is your elbow at the right angle when you’re throwing a hook? We identify discrepancies and basically give you cues in real time to improve your performance.”

There’s currently a waiting list for Growl, with US presales

due to open later this year and the first products to ship in 2026. The machine will cost $4,500 (£3,600), plus a $60 monthly subscription.

This might seem a big outlay, but Desrumaux believes that by making homebased boxing training more effective, the sport will become less intimidating and more accessible. “Growl is not for the one per cent of people who actually go to a technical boxing club and do sparring,” he says. “It’s more for the 99 per cent who’d never enter one in the first place, who just don’t want to get punched in the face – for good reason!” joingrowl.com

Growl boxing trainer

home

Proud as punch: Growl co-creators Leo Desrumaux (right) and Nicolas de Maubeuge

FC

Urban

Global goals

Got the football boots but not a full 90 minutes to spare? This burgeoning community could be the answer to your casual kickabout dreams

Showing up to play a game of football with just your boots and no idea who your teammates or opposition will be might seem a little underprepared. But when you’re part of pioneering ‘football on demand’ community FC Urban, these basics are all you need.

“It’s a dream situation for a footballer,” says Ashley Skellington, FC Urban’s director of partnerships. Traditional amateur football leagues thrive, but they’re not the right fit for everyone’s lifestyle. “If you join a team [in the capital, for example], you’ve probably got training every Wednesday night and then a game at the weekend,

which could be anywhere in London,” says Skellington. “From my own experience, when you join these teams you have wait for your chance. You might be sat on the bench and only get 10 minutes at the end of the game.”

FC Urban provides flexibility for those who want to play but can’t commit to joining a regular team. Instead, you sign up with the app, register locally, and you’re guaranteed a one-hour game organised by a dedicated host.

Skellington first came across FC Urban in 2017, when he joined the growing community as a user while living in Amsterdam. When its popularity “exploded” in the

Netherlands, he approached the founders about bringing it across the Channel. The first few UK games were played in London’s Hyde Park and Clapham Common in summer 2018. In the past year, membership numbers in the capital have grown from 150 to around 1,500, with games ranging from five- to nine-aside happening every day of the week, all over London.

FC Urban now has around 3,000 active members and 1,000 monthly games. In addition to the Netherlands and London, it has outposts in Antwerp, Stockholm, Alicante, Murcia, Newcastle and Manchester, with plans to launch in Birmingham this year. The goal is simple: to become “the biggest football club in the world… football anywhere and everywhere”.

In reality, this means the main role of FC Urban’s game hosts is to ensure the teams are balanced, even if that means pausing the game and swapping one side’s best player with an opponent: “The most important thing is to keep it interesting to the last minute, from a fitness perspective as much as anything.” While every game is “essentially mixed gender”, most are predominantly men, but Skellington is keen to build on the 10 per cent of the community that are women.

Unusually, FC Urban is a sporting community where, its director of partnerships says, “winning is not the most important thing”. Instead, its ethos is to foster a good vibe, be welcoming to all, and simply allow everyone to enjoy the beautiful game.

“Organically, we created this community of nice people,” Skellington says. “You need to be OK with playing with a whole mixture of abilities, otherwise this probably isn’t the group for you… Instead, it’s a reason to get out, go to a pitch, see real people, and have a chat and a run around. You go home feeling better.” fcurban.com

Doing it for kicks: Ashley Skellington, director of partnerships for ‘football on demand’ pioneers FC Urban

INDEPENDENTLY OWNED

Mike West Founder

George Scholey

He may love solving Rubik’s Cubes, but this man’s no square. The 22-year-old has broken world records, and his obsession has now secured him his dream job

Words Emine Saner Photography Dan Wilton

In 2022, George Scholey broke the world record for the most Rubik’s Cubes solved in 24 hours: 6,931. The 22-year-old from Northamptonshire could unscramble one in less time than it took you to read that sentence. In the speedcubing world, where every millisecond counts, Scholey’s personal best – 3.25 seconds – seems barely slower than the current world record of 3.13s, set by American cuber Max Park in 2023, though Scholey modestly admits that his average is “six seconds flat”. Still, not bad for someone who only solved his first cube at the relatively old age of 13. Nine years later, Scholey holds three Guinness World Records, has broken national records and is a multiple UK champion.

Invented in 1974 by Hungarian architecture professor Ernő Rubik, the Rubik’s Cube is an enduring and endlessly fascinating piece of pop culture; with more than 43quintillion (that’s 18 zeros) possibilities, every scramble is a unique challenge. Scholey first picked up a cube after finding one his uncle had left lying around. He began watching YouTube tutorials and became hooked. Before long, he was spending up to six hours a day training. Then Scholey picked up other types of puzzle cubes. In less than a year, he was UK champion for the Skewb.

As well as his 24-hour record, which he credits to the people around him scrambling almost 7,000 cubes and handfeeding him burgers, Scholey holds the Guinness World Records for the most cubes solved while skateboarding (500) and –last year, on the 50th anniversary of the Rubik’s Cube – the most completed while running a marathon (520). He can even tackle a cube blindfolded or one-handed. Now working in marketing, Scholey has just landed his dream job as associate brand manager for Rubik’s Cube, based

in Toronto, Canada. “It really emphasises that these hobbies, however niche, can end up giving you cool jobs,” he says. Here, Scholey talks about creating a life from your obsession, and why any one of us could do it…

the red bulletin: Are you a genius? george scholey: Absolutely not. I truly believe anyone could do what I do. The difference is, I found the thing I was passionate about, practised as much as I could and improved.

How did you get into it?

I was into magic tricks when I was around 13, and Rubik’s Cube magic became a bit of a trend, so I wanted to put that in my routine. I found YouTube videos on how to solve it. It took about four days to learn because I decided to do one step each day and practise that over and over, rather than trying to get through it all at once. By the time I entered my first competition, about five months later, I was averaging 17 seconds [per cube]. I can’t remember how much time I spent practising, but if I wasn’t at school or eating or sleeping I was probably solving. My mum was supersupportive. She was like, “This is your thing. As long as you do your homework, you can practise all you want.”

Are there tricks involved?

The centrepiece colours determine the colour of each side. Essentially, those six pieces are always solved. You solve in layers, not sides. You need to know five or six algorithms. I realised that if I could learn more, I could cut corners – I’ll be solving two to 10 pieces at a time because I know an algorithm that can solve all those at once. For beginners, it probably takes around 200 moves; for me, it’s around 60.

What does training look like?

There’s passive practice – solving over and over – which builds a good base and

helps you learn to recognise algorithms quicker, but you won’t improve that much. Then there’s active practice, which is learning new algorithms and implementing them. They’re often considered to be a chore, but I actually enjoyed learning those algorithms.

You combined your two biggest passions – running and the Rubik’s Cube – at the London Marathon last year. How was that experience? More difficult than the 24-hour attempt, because of logistics involved. I couldn’t have people running beside me, so I had to do it self-sufficiently. I had 600 cubes which I sent to cuber friends to scramble, then they were put into sealed bags of 50 and handed to me by people at twomile intervals. I had two backpacks on my front – one was full of scrambled cubes and weighed around 10kg, and when I’d solved each cube I’d transfer it to the other bag. Then I’d get 50 new, scrambled cubes at the next checkpoint. It was fun.

What has the Rubik’s Cube taught you about life?

I think it’s taught me the importance of being part of a community, finding your tribe, a group to be connected to. I’ve learnt diligence and the gratification you get from taking a less conventional path. When I’m teaching people, I tell them the first thing to realise is that you have to mess up stuff you’ve worked hard to build, and then you put it back when you’ve solved more [of the puzzle]. You might not enjoy that feeling, but then you’ll realise it’s just part of the process. That applies to so many things [in life]. Cubing teaches you to enjoy the process rather than the success, because success might not even come. I just want to do this thing for the sake of it.

Cube route

2016 Scholey becomes Skewb UK champion, securing his first national record with an average of 3.88 seconds

2022 Claims two Guinness World Records – for the most Rubik’s Cubes solved on a skateboard, and the most in 24 hours

2023 Sets a new national record for the Square-1 cube: 5.47 seconds

2024 Takes the Guinness World Record for the most cubes completed while running a marathon Instagram @george.scholey

“Beginners will take around 200 moves to solve it; for me, it’s 60”

Danni Gallacher

She writes about foraging, created a skateable forest garden, and runs board-riding retreats in the Norfolk woods. The green-fingered skateboarder tells us how

she found a way to combine and share her two big passions

Words Jessica Holland Photography Amanda Fordyce

Danni Gallacher creates her own path rather than following in the footsteps of others. In 2014, the Sheffield-based skateboarder, writer, gardener and foraging expert launched Girl Skate UK – initially a community website, then also an Instagram page and event series – to link and elevate women skaters; sister groups in Australia and India followed.

More recently, she has shifted her focus to the healing power of nature. After building a skate ramp in her ‘garden forest’ allotment, Gallacher found the space so energising that she decided to replicate it on a larger scale for others to enjoy. In 2021, The Skate Retreat was launched.

On an ancient patch of Norfolk woodland, skaters gather to share skills, swap stories around campfires, eat homegrown food, and spend two nights in rustic accommodation. Some of the retreats focus on skate coaching, others incorporate activities such as foraging, wildlife walks and barefoot forest bathing. There’s even a ‘wild spa’ with an outdoor, wood-fired bathtub. Last year was another significant milestone for Gallacher: she stepped away from Girl Skate UK and published her first book, The Forager’s Almanac. As she gears up for a spring series of retreats, the 37-year-old talks about her love of nature and skateboarding, and how she’s been able to share this connection with others…

the red bulletin: You’ve created more than one organisation from scratch. Does the process come naturally to you?

danni gallacher: I don’t really like to go with the grain, so to speak. If I see a lot of action in one area, I try to focus my attention somewhere else. So

I found it quite easy to go down that sort of route. Skateboarding and nature: they’re not something you see together very often. But they’re two things I’m super-passionate about, and I know that if I want to put a lot of my time and effort into something, I have to be passionate about it, otherwise I’m not going to take it seriously.

Why did you feel it was time to move away from actively running Girl Skate UK?

There are already groups now striving for the same sort of vision, so I felt like my energy didn’t need to be directed there any more. Now, as I’m growing older myself, I’m more passionate about getting more adults into skateboarding. I love growing the skateboard scene in general, and my focus with The Skate Retreat is that we lose a sense of play as we get older; we lose that sense of joy, discovery, curiosity. The idea of The Skate Retreat is to combine that element of play with skateboarding and our innate connection to nature.

Why was it so important to you to incorporate nature elements into The Skate Retreat?

Every time people came to skate at my allotment, they commented on how calm the space made them feel. There’s a lot of science to do with ‘green exercise’ and how exercising in green spaces helps you work hard without your body realising it. I wanted to create a space that could let everybody in on that joy we were feeling in my little garden.

What is it about both foraging and skateboarding that make them so meaningful to you?

It’s funny, people think skateboarding and foraging are polar opposites, but I view them as quite similar. They make

me feel very calm and grounded as well as excited, and they make you view the world in a different way. As a skateboarder, you’ll go through the city and look at a curb or a rail or a little transition totally differently to the businessman walking next to you. You do that when you’re a forager, too. These things give you open eyes and contentment, and they slow you down. That’s so important, especially now. And in both cases you have to be present or it could be quite dangerous.

What’s next for you?

I’m working on another book, which may be a second part to The Forager’s Almanac. Also, we’ve added another nature connection weekend to this year’s Skate Retreat itinerary. And I love learning, so every couple of years I focus myself on a different area of study. This year, I’m booking myself onto a natural navigation course. It’s about how to navigate the land without maps or a compass, just by looking at the clues from nature. That’s my area of study for the year. I’m really looking forward to it.

What are the hardest aspects of running The Skate Retreat?

Every year, I think, “Am I going to pull this off?” But when you’re passionate about something and put care and love into it, then it usually does work out. When you’re not quite there, that’s when things go awry.

What are the best moments?

The alfresco bathtub is my favourite place to spend an evening when everyone else has gone to bed. I sit there in the dark for an hour, listening to the wind rustling in the birch trees. Sometimes you see deer running through. It’s magical. theskateretreat.com

Planting seeds

2014 Gallacher launches Girl Skate UK, initially as a website to share information about events 2017 Takes over an allotment plot in Sheffield

2020 Builds a wooden mini-ramp there and starts running skate coaching sessions 2021 First Skate Retreat held in woodland in Norfolk 2024 Publishes a book, The Forager’s Almanac 2025 The Skate Retreat continues to grow, combining skating with other elements such as bushcraft, homegrown food and a wild spa

“I wanted a space that let everyone in on the joy of skating in nature”

Darren Edwards

After a climbing accident changed his life, the British adventurer was determined not to slow down. Instead, he’s redefining the boundaries of what’s possible

Words Margot Stanley

Impossible is a word Darren Edwards heard constantly in the months following his devastating climbing accident. “It was people trying to limit my expectations as somebody with a spinal cord injury,” says Edwards, who was left paralysed from the chest down. “But my experiences of the last eight years have all been about pushing back that line and redefining what people think can be achieved.”

A climber and adventurer since his early teens, the 34-year-old from Shropshire was part of the first adaptive team to kayak 1,400km from Land’s End to John o’Groats, and in 2023 he became the first handcycle athlete to complete the World Marathon Challenge – seven marathons, in seven days, on seven continents. In December, he aims to sit-ski a record distance of 333km to the South Pole, battling exhaustion and temperatures as low as -30°C. The expedition, Redefining Impossible, will raise money for Wings for Life, the charity that is similarly redefining spinal cord injury research.

It was in August 2016, while climbing in North Wales with best friend and now Redefining Impossible teammate Matt Luxton, that a section of rock face gave way beneath Edwards’ feet. His climbing partner, more than 10m below, heard the crack and saw him fall. Luxton risked his own life to throw himself on top of Edwards as his friend hit the ledge he was on, hoping the momentum wouldn’t send them plummeting 80m to the ground.

During five months of rehabilitation, Edwards found himself in some dark places. Just 26 at the time, he’d started a career as a teacher, lived for climbing, and was two years into training for the reserve unit of the SAS. The words of one of his physios stayed with him: “Don’t think about how you feel, think about who you want to become.”

Today, Edwards is a record-breaking adaptive adventurer and disability advocate, and he and his wife are about to welcome their first child. Here, he talks resilience, gratitude, and why (temporarily) breaking out of hospital was a key step in his recovery…

the red bulletin: How did you begin to come to terms with your injury? darren edwards: When starting rehab, you get it wrong all the time, falling out of your wheelchair, struggling to push yourself off the floor. The physios, nurses and therapists are incredible; they push you to your limit. There was a lot that resembled selection for the SAS Reserve – and climbing – because you’re constantly asked to go one further. That mindset really helped. I don’t think it existed naturally – if I’d had the same injury without that experience, I don’t think I’d have dealt with it the same way. One big thing for me was learning to apply perspective. For the first few weeks, I considered myself unlucky and a victim. Then I saw a photo taken by somebody who was on the road below [where I had my accident] – you can see how far I fell, and how far I could have fallen. I realised I was really lucky to be here at all. That was so powerful. I started rehab with that mindset.

How did you decide who you wanted to become, as your physio advised? That advice from Kate [the physio] was something I focused on in difficult moments. The Paralympics were on TV while I was in hospital, and I decided I’d be [at the Games] four years later. I wanted to do it in a kayak – even though I’d never kayaked before – because I saw these athletes drifting off, leaving their wheelchairs at the side of the lake. I disappeared from hospital one day, causing a panic on the ward, because I’d convinced Matt to drive us to go and buy two kayaks. For the next four years I worked towards that goal, that vision.

Injury prevented you from competing in the Paralympics, but you enjoyed success with your kayaking expedition. What did that mean to you?

Like the South Pole [sit-ski challenge], it’s a case of, “Does it provide inspiration and empowerment to others?” We didn’t know Land’s End to John o’Groats by kayak had never been done by anyone, let alone five blokes with life-changing injuries. But if we can kayak 1,400km over a month and battle through wind, waves and whatever else, anything’s possible. I want others with spinal cord injuries to think, “If he can do that, I can do this.” And that might be something as simple as returning to work. We call it Redefining Impossible because you could apply it to your own life. Not everybody wants to ski to the South Pole, but we should each feel like we can pursue our passion and not limit ourselves. All these expeditions – as well as this year’s Wings for Life World Run, which I’m taking part in – raise money for charity, so that’s the other purpose. One day, there could be a version of me that gets to walk out through the double doors of a spinal unit.

How is your Antarctica training going? We’ve trained for two years now, and done three expeditions. We crossed Iceland’s Vatnajökull glacier, the largest ice cap in Europe, [across a distance of] 135km, which took 12 days. And we’ve been twice to the home of polar training in Norway, where Shackleton, Scott and Amundsen all trained. The sit-ski in this environment is really new, so you’ve got to have a kind of pioneering spirit.

Wings for Life World Run

In this unique, global race, all entrants start at the same time, whether taking part in a flagship run, a local group run or wherever they are, using the app There’s no set distance – the finish line comes to you in the form of a (virtual) Catcher Car – when it reaches you, you’re out The Catcher Car begins to chase 30 minutes after the start and gradually increases its speed from 14kph to 34kph All money raised goes directly to research into finding a cure for spinal cord injury

This year’s run is on May 4 wingsforlifeworldrun.com

“I want others with spinal cord injuries to think, ‘If he can do that, I can do this’”

Pedal

In the world of freestyle BMX, the line between distinction and defeat is often razor-thin, the stakes as high as the most intimidating vert ramp. But in switching up his approach, Gateshead-born rider KIERAN REILLY is not only taking titles – he’s shaping the future of his sport

Words Matt Blake Photography Eisa Bakos

to the medals

Kieran Reilly perches at the top of the ramp, exhales and drops. His legs pump like train pistons, his head down, as he hits the up-ramp and rises in a fight against gravity that he’s winning. Then, at the lip, Reilly yanks his handlebars, throws back his head and launches into the air. He’s spinning backwards now, man and bike blurring into a Catherine wheel of black, blue and silver, his trademark mullet flailing like a cape. He still has three full backward somersaults and a twist to complete before hitting the floor 6m below. He loops once, twice, then – just as he is surely about to impact – loops again, swivels, and touches down on the wood wheel-first. The skatepark erupts. No one has landed the elusive triple flair before; it’s 16 years since a rider first did the double. Reilly will forever be remembered as not only the BMXer who landed the trick but the first with the courage to even attempt it.

“It was the best feeling I’d ever had,” he says. “Pure elation. All the work that went into landing that trick: the months of training, the days of failing, the nerves, the fear, the crashes… it was just…” He shakes his head, unable to find the words. “I still get a shiver when I think about it.”

The 23-year-old Brit was already well-known in the world of freestyle BMX before landing the triple flair three years ago. But that jump catapulted him to stardom, launching a career that’s seen him compete pretty much everywhere a BMXer can pick up a medal. In 2022, he won silver at the 2022 European BMX Championships in Munich. Then, the following year, he swapped it for gold at the European Games in Krzeszowice. In August 2023, Reilly won gold in the Men’s Freestyle BMX event at the Urban Cycling World Championships. As a result, he qualified easily

for the 2024 Paris Olympics, where he missed out on gold to the Argentinian José Torres Gil by just 0.91 points. Further golds followed in the British and European Championships. In short, right now Reilly is at the top of the BMX ramp. And as every BMXer knows, the top is where the cool stuff really begins.

We’re at the Adrenaline Alley skatepark in Corby, the Northamptonshire town Reilly moved to with his girlfriend Savannah three years ago. With more than 11,000sqm of ramps, pipes, rails, bowls, ‘volcanoes’ and pretty much anything else you can jump off on wheels, Adrenaline Alley is the largest indoor skatepark in Europe. “It was hard leaving Gateshead, all my family and friends,” says the Tyne and Wearborn rider, who gave up a carpentry apprenticeship to turn pro in 2021. “But I knew that if I wanted to make it professionally, coming here was the only way.”

Adrenaline Alley is no playground; it’s a training ground where the line between progression and peril is razor-thin. For every big trick landed, there’s the risk of a devastating fall. And it’s not the pain most riders fear but the time off. Today’s ride is his first since a hernia operation two weeks ago, sustained simply by pushing his body too hard. “It’s horrible,” he says. “Not being on the bike just kills me. It’s basically my fifth limb. The really scary thing about crashing is not being able to ride.”

Since taking up the sport at the age of eight, Reilly has broken both ankles, his wrist, all his fingers (this is surprisingly common in BMX) and suffered two serious concussions. He barely remembers his first injury, in a competition in Whitley Bay in 2012. “I was 10, and it was the first time my mum came to see me compete,” he recalls. “I wasn’t even doing a trick; I just had a lapse in concentration going

“Not being on the bike just kills me. It’s basically my fifth limb”

Tall in the saddle: freestyle BMX champ Kieran Reilly, photographed for The Red Bulletin in Corby, Northamptonshire, in February this year

Home from home: Reilly trains at Adrenaline Alley, Europe‘s biggest indoor skatepark.

“It was hard leaving Gateshead, all my family and friends,” he says. “But I knew that if I wanted to make it professionally, coming here [to live in Corby] was the only way”

“Seeing BMX in the Olympics has shown parents that you can make a career of it if you work hard enough”

“With the triple flair, serious injury was always a possibility. But in this sport you have to push the fear down and back yourself”

down a ramp, my front wheel washed out, and I went over the handlebars.”

This, in BMX slang, is a scorpion, where the rider flips over the handlebars and lands on their face, their legs bending backwards over their head. “Your body looks like a scorpion’s tail when you hit the floor,” he grins. “I was knocked out, split my chin open, and my mum was in bits. I woke up in hospital with a pretty serious concussion. It took a while for my mum to watch me ride again.” Scorpions are an occupational hazard for BMX riders, and, like most action sports, freestyle has its share of cautionary tales. “The fear is always there,” Reilly admits. “With the triple flair, I knew [serious injury] was always a possibility. But in this sport you have to push the fear down and back yourself if you want to do well.”

Starting strong

When Reilly took his first bike – a WWE-themed Christmas present – down to Leam Lane skatepark in Gateshead, the fear of crashing was as far from his mind as Olympic gold. “I never thought about the consequences,” he says. “I was the kid who’d try anything. Plus, I was always the youngest in the skatepark, and the older kids looked out for me.”

Maybe they saw something in Reilly – an absence of fear, or an abundance of talent. Or perhaps it was simply his determination to pedal on until it was too dark to see. Living within whistling distance of the skatepark helped: “It was literally across the football pitch from our house. Mum just poked her head out the door and whistled for me when tea was ready.”

Even now, whenever he hears a loud whistle he’s transported back through time. “My heart always sank when I heard that sound, because it meant I had to go in,” he smiles. “The only place I ever wanted to be was in the skatepark. It was all I thought about, from the moment I got up to when I went to bed.”

Reilly’s glossary of BMX jargon

Dead sailor

“That’s when you kick a tailwhip and the bike just drops away from you. Basically, you mess up the trick and you’re going straight to the floor.”

Scorpion

“When you crash on your face, and your legs fall over your head so you look like a scorpion’s tail.”

Huck

“A big pull, like you’re really trying hard on a trick.”

OTB

“Over the bars. As in a crash. Never a good thing.”

Sandbag

“Someone who enters an amateur competition when they’re already a pro. It’s easier to win that way, but it’s not really respectable.”

Send

“Going all-in on something risky.”

Prime

“When you land a trick really good, nice and clean.”

Case

“When you’re jumping from one ramp to another and you don’t quite make it, so you land with half the bike on the ramp and half off.”

Dialled

“When you do something that looks easy and consistent. As in, ‘His tailwhips are dialled.’ It also means a bike that’s well maintained.”

Wood pusher

“[Laughs.] It’s a derogatory term for a skateboarder. But no one really says that any more. There’s more respect between us than there used to be.”

Reilly’s journey from windswept skatepark to Olympic arena mirrors the evolution of freestyle BMX itself. Born in the sun-soaked suburbs of California in the late 1960s/early ’70s, BMX emerged from a desire for freedom, self-expression, and a rejection of the mainstream. Like skateboarding and surfing, it soon grew into a subculture, with homemade ramps serving as launching pads for aerial acrobatics and –for the most talented – fruitful careers. By the ’80s, the vibrant energy and rebellious spirit of US BMX culture had crossed the Atlantic, captivating British youth seeking an identity outside mainstream sports.

“The difference between BMX and skateboarding, for instance, is that [BMX] is relatable,” Reilly says. “Everyone can ride a bike, so they understand what we’re doing.” By 1995, sports channel ESPN had founded action-sports event the X Games, which included freestyle BMX. Riders competed in timed runs where they whipped and flipped and spun on a course of ramps, jumps and other obstacles in ever-more gymnastic feats. It didn’t have the rigid technical criteria of other judged sports; a run was largely assessed on an overall ‘impression’ of its difficulty, amplitude, originality, risk, variety and style – more like a critique of art than of sport.

The International Olympic Committee (IOC), keen to connect with modern youth, was paying attention. From the late ’90s it began adding action sports to its roster, with mountain biking, snowboarding and, in 2008, BMX racing. It invited BMX freestyle, along with skateboarding and surfing, to join in at Tokyo 2020. However, Reilly says, “When the first Olympics came in, there was a big divide as to people for and against.” The argument against was essentially this: BMX is a lifestyle, not a sport, based on self-expression, creativity and good times, not hierarchy, discipline and nationalism. Reilly sees it differently: “I get the argument, but I don’t know anyone of my generation who doesn’t think the Olympics are a good idea. It’s brought money to the sport; more bikes are being sold. And seeing BMX in the Olympics has shown parents you can make a career of it if you work hard enough.”

He believes that these days riders are seen more as athletes and role models than the baggy-trousered layabout trope of yore. “Ninety per cent of the guys you see now, they’re trying to be their best self on a BMX,” Reilly says. “They’re athletes. The sport has really changed. You see kids now who are like, ‘I want to be like that’, in the same way they look up to their favourite footballer. The Olympics helped that.”

Gold ambition

So what gave Reilly the edge over the thousands of BMX-obsessed kids growing up in skateparks across Britain? “It’s not just about talent,” says British BMX legend Bas Keep, owner of the brand Tall Order and a mentor to Reilly since his teens. “What makes Kieran special is his attitude.” Keep illustrates the point with a story: “Kieran must’ve been 15 when I invited him to a jam I’d organised in Brighton. He and his dad drove all the way from Gateshead the night before, and they slept in the car. The next day, everyone was having a good time until the heavens opened. Kieran was the

Fitness focus

Reilly’s BMX prep

Quads

”For my quads, I do a lot of intervals on a bike, like the assault bike. You need strong quads for BMX because they give you the power to pedal, especially when you’re sprinting up the ramp. Interval training is good because it helps you build endurance for those bursts of speed.”

Grip strength

”Grip strength is crucial in BMX. You need to be able to hold on tight when you’re doing tricks and landing. I do a lot of dead hangs, where I just hang from a bar with my arms fully extended and my feet off the ground. They’re a simple yet effective way to target multiple muscles in your upper body and arms, especially fingers.”

Lungs (cardio)

”You need good cardio. And again that’s just a lot of intervals on the assault bike, mainly sprints. It might be 20 seconds on, 40 seconds off, that kind of thing. A 60-second BMX run in a competition might not sound like that much, but it doesn’t take long to wipe yourself out. So lung capacity and stamina are crucial to last the distance.”

Core

“A strong core is super-important in BMX. We’re rotating and flipping through the air, and everything comes from your trunk strength. So you use your core for pretty much every trick. Hanging leg raises are good, and I also use this machine at the gym called a GHD – it stands for glute ham developer, but it’s good for sit-ups and building core strength.”

Lats

“Lats are important, too. I use them for a lot of tricks, especially tailwhips where I’m throwing the bike around my body. Strong lats help you control the bike. To train them, I do pull-ups. I haven’t really tested my max, but I reckon I could do about 35.”

Calves

“Calves are important for pumping – that’s when you push down on the pedals and kind of spring up off the bike to get more speed and height. For calves, I’m doing box jumps, high box jumps. That’s plyometric training – it makes your calves more powerful.”

only one who didn’t run for shelter, staying out there in his T-shirt, sodden and cold, performing in the rain. Then, when it was over and everyone had left, he and his dad stayed behind to pick up litter before driving all the way back up north for work the next morning.

“It was obvious from the start that Kieran was different. And that Olympic final performance… well, I think in those 60 seconds we all saw what an incredible rider he is.”

While it’s impossible to say exactly how many viewers saw Reilly clinch silver in the BMX Park final at Paris 2024, it’s safe to say the figure outnumbered the population of most countries. The rider produced a performance as immaculate as it was visceral, a spine-tingling feat of aerial gymnastics that would have given Isaac Newton pause for thought. At the end, he flung his bike away and dropped to his knees – he knew he’d done something special. Afterwards, Reilly thanked his “lucky mullet” for the performance. “I’m stuck with it,” he laughs. “I only had it because I’d got a dodgy haircut just before the Euros [in 2023] and was trying to grow it out. Then I won gold at the Worlds, and the good results kept coming in. I thought, ‘Well, I can’t cut it now.’”

After winning silver, only a true pro could home disappointed. “I went to Paris to win the gold,” he says, “and I really believed I could. To have come so close…” He pauses. “I’m very proud of that silver, but it was bittersweet.” His thoughts turned almost instantly to Los Angeles 2028. “I literally cannot wait,” he says. “I’m doing everything I can now to get that gold.”

Full force

Reilly’s lifestyle could hardly be further from the dirtbag image of the first UK riders. At 1.6m (5ft 3in) tall, his low centre of gravity helps him stick to the bike like a burr. His thighs – the engines of his sport –are the size of Ibérico hams, and his heavily tattooed arm muscles bulge beneath his T-shirt like they’re trying to break free. As Keep says, “Kieran wasn’t born that strong – he’s built that body in the gym.”

“I was always in denial about the gym until I began training for that triple flair,” Reilly says. “Then I realised: BMX is a game of inches, marginal gains. I changed everything up: my off-bike training, my diet. I genuinely believe that’s what made the triple flair possible, and everything else I’ve achieved since.”

Now, his training is a holistic blend of on-bike practice and gruelling gym work. He rides five to six times a week at Adrenaline Alley, followed by a one-to-two-hour gym session focusing on areas crucial for BMX: fingers, quads, lats, calves and core strength. “I’ll have a light snack in between, some fruit, then go to the gym to train,” he says. “That’s pretty much my life now.”

Another part of Reilly’s push to go bigger and better is Hyrox, the wildly popular – and punishing –global indoor fitness race that combines running with strength exercises like sled pulling and the farmer’s carry. At the London event in 2023, he finished in the top six per cent of entrants, with a time of 01:10:56: “It is hard but, man, it feels good to cross that line.”

No limits

If Reilly’s eyes light up when discussing fitness, they sparkle when he talks about riding. This is what he was made to do – to blend body with BMX, pushing each to their limits. In a few weeks, for example, Reilly will attempt to jump over a bus in Manchester city centre. Is he nervous? He grins. “Nah, it’s about a 20-foot [6m] jump. And there’s no tricks, just air.”

The stunt is publicity for upcoming event Red Bull Featured – the brainchild of Bas Keep – where 16 of the world’s BMX elite will land the most outrageous tricks possible on a custom-built course. “I can’t wait,” Reilly says, eyes widening. “I’ve been working on three new tricks, world firsts, and I’m hoping to do them [there].” What are they? “I can’t tell you that,” he winks. “I wouldn’t want my competitors getting wind of it.”

That’s the beauty of freestyle BMX: the only limit is your imagination. For many, a bike is simply about getting from A to B. For a freestyle BMXer, A and B were never the point; it was only ever about ‘to’. It’s why many BMXs have no brakes: they never need to stop. Reilly will be the first to admit he has none, either: “I always said that after the Olympics me and my girlfriend would go on a two-week holiday to Mexico to relax. But I realised I couldn’t take that long off, so we did a long weekend in Greece instead.”

Does Reilly think he’ll ever reach his limit? He thinks for a moment. “No,” he replies. “I see no reason why BMX as a sport can’t constantly evolve, for ever. And I can’t imagine not being a part of that.”

Check the balance: Reilly treats us to a footjam tailwhip – no sweat for one of the elite riders of BMX

Red Bull Featured will take place at Manchester Central Convention Complex on April 12. For tickets, go to redbull.com

Last year saw the Red Bull Cliff Diving World Series pay a first-ever visit to Northern Ireland’s magnificent Causeway Coast, which was used as a filming location for Game of Thrones Divers including Mexico’s Jonathan Paredes leapt from rocks close to the ruins of 16th-century Kinbane Castle.

Making

the Leap

Cliff diving is a compelling combination of beauty and brutality, graceful twists and spins performed at 85kph. The 2024 RED BULL CLIFF DIVING WORLD SERIES raised the bar higher than ever as divers from around the world stepped up and took off

Words Rachael Sigee

Cliff divers must combine power, poise and balance with precise calculation and extreme courage. Plus, they need to adapt to the unique challenges of each location, whether diving off a bridge, rocks, or a purpose-built platform like this one at Montréal’s Grand Quay, where American David Colturi leaps from 27m.

Last season opened with ideal conditions at Lake Vouliagmeni in Athens – a first-time visit for the women’s competition, which began in 2014. Women divers like the USA’s Eleanor Smart (pictured) compete from a slightly lower height – 21m – than the men to account for their muscle mass and physiology as they enter the water.

As they teeter on a rocky precipice at the height of an eight-storey building, a cliff diver must be in total control of mind and body. There’s no margin for error as they launch themselves and plummet at speeds of up to 85kph, contorting their body through twists and somersaults. When they hit the water – feet-first, their muscles tensed to prevent injury – the impact will be as much as 10Gs, akin to landing on concrete.

First attempted in Hawaii in the 1700s, this breathtaking spectacle is often called ‘the world’s oldest extreme sport’, and today the Red Bull Cliff Diving World Series brings the jaw-dropping action to some of the world’s most stunning locations, from ancient Irish coastlines to iconic Italian beaches.

Last season saw the coronation of new cliff-diving royalty. A fearless competitor from the age of 16, 2024 winner Aidan Heslop leads a new generation of divers who are raising the bar and triggering a recalibration of Degree of Difficulty scoring to reflect their daring new tricks. The 2025 season, which starts in El Nido in the Philippines in April, will push boundaries further than ever before, but the 300-yearold principle of lele kawa – which loosely translates from Hawaiian as ‘leaping feet-first from a high cliff into the water without making a splash’ – remains.

After launching from the rocky cliffs at Dunluce Castle on the first day of diving in Northern Ireland, the UK’s Aidan Heslop (pictured) lay in third place. But on days two and three, despite strong winds on the platform at Ballycastle Harbour, he kept his composure to deliver mammoth degrees of difficulty – 5.7 and 5.9 – and nab the home win in front of 30,000 spectators.

In the Red Bull Cliff Diving World Series, 12 men and 12 women –eight permanent divers and four rotating wildcards in each group –compete for the King Kahekili trophy, named after an 18th-century Hawaiian chief reputed to have leapt from the holy cliffs of Kaunolo. At Puglia’s Polignano a Mare, 40,000 fans saw local wildcard Elisa Cosetti (pictured) dive from the beach’s famous terraces into the turquoise waters of the Adriatic Sea.

From rocks high above the Mediterranean in Antalya in Türkiye, the Netherlands’ Ginni van Katwijk catapults herself into a first dive. On each stop on the tour, the athletes complete four dives of increasing difficulty, and judges award them scores for take-off, position in the air, and water entry.

diver Yolotl Martinez, 21, was one of 2024’s rising stars. On his debut, in Boston (pictured), the Mexican rookie narrowly missed out on a podium, but after only a two-month wait he claimed third place in Montréal. Now he’s on the permanent line-up for 2025, ready to reach new heights.

Wildcard

Cliff diving requires nerves of steel – few know this better than Australia’s Xantheia Pennisi. After overcoming a fear of heights to compete, the former gymnast endured a tough 2024 season, with a mental block in Athens and then a withdrawal in Boston. But she made a triumphant return in Italy and even debuted brand new dives in Antalya (pictured).

There was a fairytale moment for cliff diving’s power couple when Molly Carlson (pictured) and Aidan Heslop snatched a double win at Carlson’s home event in Montréal, where the pair live and train together. The win sent Heslop to the top of the men’s rankings and boosted Carlson in her season-long battle with Australian rival Rhiannan Ifflandalthough the Aussie ultimately triumphed.

Sunshine and blue skies aren’t guaranteed on the tour. Even in July, the Atlantic waters in Northern Ireland were chilly for athletes like Mexico’s Sergio Guzman (pictured), and the women at Kinbane Castle faced an extra challenge: abseiling 10m down the cliff face to their launch spot.

The permanent divers competing in the 2024 Red Bull Cliff Diving World Series line up at Athens’ Lake Vouliagmeni, ahead of the season opener.

new Breaking ground

When ADRIANA BROWNLEE summited Shishapangma in Tibet last October, she became the youngest woman ever to climb all 14 of the world’s highest peaks – the eight-thousanders. But then, the London-born mountaineer was already something of a veteran, having started training at the age of eight. Here, she talks thrills, fears and near-misses… Words

Go Cho: Adriana Brownlee makes her ascent of Cho Oyu in October 2023, using the lesserclimbed route on the Nepal side

“Mountaineering

is 70-per-cent mental strength, 30-per-cent physical for me”

Icy determination:

Brownlee, pictured during her 2023 ascent of Cho Oyu, has been pushing the limits of endurance from an early age

the

“I’m human – I do have fear. But that fear is what keeps me going”

red bulletin:

You’re only 24 – where did you get the drive to scale the world’s 14 highest peaks at such a young age?

adriana brownlee: It started when I was eight years old. I was in the classroom at primary school – I think it was in year three – and our teacher asked us to write down what we wanted to do when we were older. My dad was climbing at the time and had just got to the top of Aconcagua [in Argentina, the highest mountain in the Americas], and I was massively inspired by that. I wrote that I wanted to climb Everest, to be the youngest woman to do it, and to use that achievement to inspire other people. I’ve still got that letter today. And 12 years after I wrote it I was standing on the summit.

Does a challenge like this get easier as you go along – or rather, further up? From a fitness perspective, it gets harder. Every eight-thousander you complete, your muscle mass depletes and your cardio goes down the drain. That’s because you can’t really train between summits, and when you’re on the mountain you’re actually stagnant for about two months. You don’t really do anything before you go for a rotation and a summit push. You lose a lot of fitness, so by the end I was finding it hard to get to the level that I was at when I started the project.

What kind of training did you have to do for this project?

At the very beginning there was COVID, so I couldn’t even go outside. I was running up and down the stairs of our apartment building with a ten-kilo backpack and an oxygen-suppressing mask. The first part of that was in Kingston [in Surrey], then I continued during the first four months at my halls of residence in Bath. I was doing

it in my university block – I was known as the crazy stair person! I had two ulterior personalities: one was the typical student in Fresher’s Week, going out and getting drunk every night; the other was this hardcore trainer who was completely focused on this mountain challenge.

How did the mask prepare you for life on the mountain?

Essentially, it’s like breathing through a straw – it suppresses the amount of air coming in and makes your lungs work harder. It gets you prepared, because that’s how it feels when you’re climbing at altitude without supplementary oxygen: breathing is very difficult, very laboured, and your lungs are working incredibly hard. I could have just run up those stairs with a backpack, but [the straw] added a whole new level of discomfort.

Did you use supplementary oxygen at all during the 14 climbs?

I did 12 of my eight-thousanders with supplementary oxygen. I tried K2 without

it, but we didn’t have enough support. We would have trailblazed had we managed it, but it’s almost impossible. How do you know when you need it? You have to listen to your body. But most of it is pre-planned, especially in the first few mountains while you’re improving your skills. It wasn’t until the end of the project that I knew my body could deal with it – I knew I could rescue myself without it.

How much of the preparation for this was physical and how much mental? I was trying to do as much fitness work as I possibly could. When the [COVID] restrictions were lifted, I was doing a lot of cardio – 5K and 10K runs – and an awful lot of swimming. I was doing probably an hour or two a day, seven days a week. The rest of the time would be training my skills – rock climbing, watching documentaries, planning out the routes. Mental training was obviously really important, too. I practised a skill known as ‘red to blue’, where you

Dream team: the British mountaineer knows that Gelje Sherpa – her partner in climbing and in life – always has her back

essentially write down everything that could possibly go wrong on the mountain: avalanche risk, rock fall, bad press, death! Every single eventuality. Then you write down what you would do, step by step. It allows you to prepare for the worst-case scenario, basically.

Training can only prepare you for so much. What was the hardest part of the project in reality?

When you get negative thoughts, you have to brush them off – if you don’t, it’s easy to slip into a spiral. There were some very tough times, but I told myself that no matter what was thrown at me, as long as I wasn’t dying, I would keep going. A lot of it is mental, but there was physical pain, too. It’s quite a slow, gradual sport. But on Shishapangma [in Tibet], when I was doing a summer without oxygen, every two or three steps I just wanted to vomit. My digestive system was failing; it was extremely uncomfortable. Some of the mountains come with a very high avalanche risk, too. Take Annapurna [in Nepal] – the death rate on that mountain is 35 per cent, and the one thing you

“When you’re working in the death zone, you don’t have the energy to talk”

want to do is minimise that risk by climbing at night when it’s colder and there’s more chance the snow will be compacted.

Sorry, 35 per cent?

Yes, it’s ridiculous. Annapurna is the most dangerous mountain in the world. Climbing Annapurna is probably the most dangerous activity you could do in any sport, anywhere.

Is reaching a summit always the most euphoric moment in a challenge such as this?

No, the most euphoric is generally when you know that you’re going to get to the summit. On Shishapangma, that was when I saw the headlights coming back down the mountain [from the summit] – I knew they were only an hour ahead of us. For me, that was the most emotional and exciting moment. Reaching the summit is almost the most stressful part: there’s generally only enough space for one or two people at the actual summit, but there’ll be five or six trying to get a photo. Getting home and reaching safety is always a nice moment, too, but when you’re at the summit you’re only 50 per cent of the way there.

Your dad has been a big influence on your life, hasn’t he? Definitely. He hasn’t done any of the

Climbing the fitness mountain

“When you’ve scaled this many peaks in such a short pace of time, your muscle mass does deplete and your cardio is impacted,” says Brownlee. When returning from a big trip, she says, in terms of fitness it’s almost like starting again. And Brownlee’s tried-and-tested methods for building strength can help anyone get moving –whether or not summiting Everest is part of your plans…

Make a splash

“Doing a sport that’s soft on the body is a good way to start – things like running or a StairMaster can be hard on your knees. Swimming and light cycling is a great building block, probably my favourite way to get my cardio [levels] back up. It’s a full-body workout.”

Take your time

“When you’ve built a base, you can start jogging. It’s not about speed; it’s about gentle cardio. Gradually build up the distance so you go faster and longer. But don’t rush.”

Find your balance

“In terms of getting back my muscle mass, it’s a case of doing what I was doing when I was at my max, but bringing the weights all the way down, starting small. Working on balance is good, too. Use a half yoga ball – stand on one leg, then add in some squats and some pigeon squats.”

Make it fun

“Rock climbing isn’t just a great way of building up fitness; it’s also great fun. Get yourself to a climbing wall and try it out. It’s a brilliant way of generating muscle very quickly. My next project with Gelje is to open a climbing wall in Kathmandu –not just for tourists but also for locals and their kids. It’s such a great sport and an amazing way of getting fit.”

Peak fitness: Brownlee undergoes crucial altitude training at a specialist centre in London

eight-thousanders – climbing was more of a hobby for him – but any time he had off work, he would go to the mountains. He loves to push himself to the absolute limit, so I had that [same] mindset growing up. He trained me from the age of eight. It was like I was going to be in the SAS – it was incredible! At weekends we’d be at Richmond Park; a typical training session started at about 6.30am. We’d head to the bottom of the biggest hill, then we’d run up and down it endlessly for about two hours. Sometimes we would attach a tyre to a harness, put it round my waist and run with that as well. Then my dad would probably go on another run. Then, later in the afternoon, we’d go to the gym and do some kind of resistance workout, or hill sprints on the treadmills. He would train me for Spartan Races –his main thing was OCR [obstacle

course racing], and I qualified for the World Championships when I was 16, I think. It was total madness. He still runs now – he did a 100K race a couple of weeks ago in under 10 hours. I still have no chance of beating him at 10K – he’s next-level.

It sounds like from an early age you were prepared for anything the world could throw at you… I think I’ve always had that mental edge. For me, mountaineering is 70-per-cent mental strength and 30-per-cent physical. Without that

“At eight, my dad trained me like I was going to be in the SAS – it was incredible”

mental strength, I wouldn’t have been able to do the things I’ve done. For me, climbing is almost, in a weird way, like meditation. You’re just so focused on one thing, and there’s nothing else in the world that can distract you. You’re literally putting one foot in front of the other. It’s very simple.

How has your life changed since leaving university?

In the past three years I feel like I’ve lived about 20, given the number of things I’ve achieved. It’s pretty special to think that just over three years ago I was sitting in uni accommodation, trying to do classes online. I had that big dream – I knew I was going to go to Everest – but you never know if you’ll actually achieve it. I don’t think I’ve yet had a chance to really reflect on what I’ve done. The planning, the climbing, the company as well…

High teen: a 15-year-old Brownlee and her dad Tony pose for posterity on the summit of Russia’s Mount Elbrus

everything has been a whirlwind. But none of it happened by magic – an awful lot of hard work and sacrifice has gone into this.

How does it feel when you return to ‘normal life’ after completing an expedition like this?

It’s always a challenge coming back home – you get this post-expedition depression and wonder what you’re going to do next. Luckily, myself and Gelje [Sherpa, Brownlee’s boyfriend and climbing partner] have a business together – an expedition company we started about a year ago. That’s our main focus now, and it takes up 99 per cent of our time. It’s amazing to guide people on the

mountains and show them what we love doing, too. We’re also going to try to get our paragliding up to scratch. We’re both trained paragliding pilots, and it’s something we love doing.

How important is it to have a partner who knows the kind of dangers and challenges you face on the mountain?

Mountaineering is always seen as an

individual sport, but a lot of teamwork goes into any climb. Gelje and I don’t even have to verbally communicate to know what each other is going through. When you’re working in the death zone, you don’t have time to talk; you don’t have the energy to talk. We trust each other with our lives. I remember on the very first expedition we did together on Everest, there was one section near the Hillary Step, [a vertical rock face] almost at the summit and probably one of the most dangerous parts of the mountain. I was tired and I didn’t have a lot of experience at 8,000 metres. I took both of my safeties off the rope, so for a split second I wasn’t attached to anything. He grabbed my arm, reattached them and started shouting at me. I could have died – all it takes is that split second of stupidity.

Have you helped him in vulnerable moments, too?

On Cho Oyo [in the Himalayas], which was Gelje’s last 8,000m peak for the 14 project, he tried to do it without oxygen, but we hadn’t acclimatised. We went straight for the summit push, but at about 8,000 metres Gelje started vomiting blood. He was so weak he couldn’t even walk, and he was falling asleep. There was one section that was like an ice wall and wasn’t roped up, so we had to rope to each other, and I basically had to pull him up. I remember him dozing off; I could feel his weight pulling me back. All I had to rely on was my crampons. I was just praying to God that we would make it up there. At the top, I got out the oxygen and the mask and told him to fucking put it on, because if he didn’t there was a fair chance we would both die up there. That was the only time I’ve really seen him as vulnerable.

Are you scared of anything?

I’m human – I do have fear. But that fear is what keeps me going. Fear is adrenaline and it’s the same hormone as excitement, so I try to channel it in a different way. It’s like being between life and death, and that’s the only time I feel truly alive.

There will be plenty of people who feel inspired by your story – was that one of your main motivations?

“In the past three years I feel like I’ve lived about 20, given all I’ve achieved”

That’s my main mission. I want to inspire the generation who were in the same school chair as I was at the age of eight. I want to show that, no matter how unconventional or unique your path is in life, you just need to go for it.

adrianabrownlee.com

Positive altitude: Brownlee hopes her achievements inspire others to follow their own path in life, no matter how unconventional

Urban beat. Alpine retreat.

THE INNSBRUCK REGION IS MUCH MORE THAN “JUST” THE CAPITAL OF TYROL.

This unique combination of city and countryside and valleys and summits is evident everywhere you go: the buzz of the city and sights to see are never very far away from sporting thrills and opportunities to conquer your next peak – whatever the season.

Touching bass

Scenes from a packed dancefloor at Mumbai club night Low End Therapy.

Hosted by Swadesi, it provides the city’s lowercaste youth with a rare entry point to club culture

Partners

MUSIC in Grime

Socially conscious Mumbai rap crew SWADESI want to change the world with their sound. The collective’s razor-sharp bars speak truth to power, and their multilingual club nights are democratising India’s dancefloors

Words Alice Austin Photography Yushy

The sound of muffled bass is audible before you actually see the club. Tucked away down a series of alleyways in Parel – a downtown district in Mumbai, Maharashtra – from the outside antiSOCIAL looks like any other building in the Indian city: lowrise and slightly ramshackle, framed by palm trees. But inside its walls a musical revolution is in progress.

Socially conscious rap crew Swadesi are presenting their sold-out club night, Low End Therapy. Basking in the full force of the bass, the crowd is 15 people deep and everyone in the front row has their gun fingers out. BamBoy is behind the decks, DJing under his alias Kaali Duniya. The air conditioning does nothing to prevent the sweat dripping down his forehead as he plays his reggae and dubstep selections, whipping the crowd into a frenzy. They bounce on the spot and dance right up against the decks. A man with a broken wrist headbangs so hard he almost jogs the CDJs. Then BamBoy steps up to the mic and declares in Marathi, the state language, “The music you’re about to hear is called grime.”

BamBoy is often recognised on the streets of Mumbai these days. A few days before his club night, he’s stopped him midway through a mouthful of biryani by a young man in a Nas T-shirt: “Yo,

BamBoy! I loved your Boiler Room set!” Last year, his crew Swadesi blew the world away with a live stream for the music broadcaster, showcasing 30 minutes of razor-sharp grime and hip hop rapped in Marathi, Bengali and Hindi, followed by a halfhour roadshow set from BamBoy alone. This was the first time that Mumbai street culture had been represented on the world stage, and the community adore him for it.

BamBoy, real name Tushar Adhav, stands about 5ft 6in (1.67m) tall but has the presence of a giant. He has intelligent eyes that miss nothing, and his customary dress code is baggy (“Not because of hip hop, but because I have a big belly,” he chuckles).

BamBoy is a rapper and key figure in Swadesi, a group of multilingual, socially conscious rappers, producers and musicians who aren’t afraid of speaking truth to power. The crew formed in 2013 with the aim of addressing India’s many social issues and creating a community for those most marginalised, while also representing their own roots. As well as BamBoy, the collective comprised DJ/producer NaaR (Abhishek Menon), rappers MC Tod Fod (Dharmesh Parmar), MC Mawali (Aklesh Sutar) and Maharya (Yash Mahida), and DJ/producer RaaKshaS Sound (Abhishek Shindolkar). But Swadesi’s community is expansive, way beyond just the core members. Every few months, they host Low End Therapy to give lower-caste communities access to a club space and introduce them to reggae, dubstep and grime