QUANTUM LEAP

– SOCRATES

“IT IS A SHAME FOR A MAN TO GROW OLD WITHOUT SEEING THE BEAUTY AND STRENGTH OF WHICH HIS BODY IS CAPABLE”

– SOCRATES

“IT IS A SHAME FOR A MAN TO GROW OLD WITHOUT SEEING THE BEAUTY AND STRENGTH OF WHICH HIS BODY IS CAPABLE”

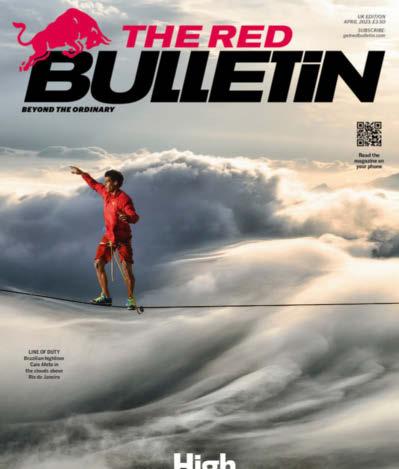

The Spanish photographer lives in Austria, documenting his passion for snowboarding – and anything else that piques his curiosity. He visited the Nürburgring to shoot the World Rallycross series for this issue. “I was impressed by the acceleration of the cars, and the precision needed to control them,” he says. “The teams are pushing into the unknown with the move to electric.” Page 5 0

Progress relies on people daring to do things differently, and in this issue we feature athletes willing to leap into the unknown – literally, in the case of our cover star, cliff diver Aidan Heslop (page 32). The 20-year-old from Plymouth – who is pictured on our cover performing the world’s hardest dive in Polignano a Mare, Italy, in 2022 – is pushing his sport into a new era with dives so complex they’ve never been attempted before. His latest creation is about to push the bar higher than ever, and could see him become a world champion this year.

Then we meet the warring dynasties of the World Rallycross Championship (page 50), a series which last year entered a brave new world that’s fully electric and faster than F1, presenting spectators with a multisensory experience thanks to engines that purr rather than roar.

The award-winning writer and editor, based in Ontario, Canada, has written for The Atlantic and The New Yorker. Interviewing Aidan Heslop in Montréal gave him a fresh perspective on cliff diving. “Aidan’s dives appear effortless,” he says. “He’s just as comfortable in the air as he is on solid ground. It’s clear his willingness to test his physical limits is changing the sport.” Page 32

And we conquer new heights with Lebanese climber and professional ‘mover’ Nelly Attar (page 42). Before she scaled summits, Attar went underground, using her dance skills to bring movement to women in her adopted home of Saudi Arabia, where physical activity has historically been severely restricted.

Enjoy the issue.

8 Gallery: highlights from global photography contest Red Bull Illume, including a legend of the falls in Iceland; ‘hoverboard’ trickery in Salt Lake City, USA, and tilting at (broken) windmills in northern Spain. Plus, some F1 time travel in the Czech Republic

15 Halcyon tracks: award-winning singer-songwriter Ellie Goulding revisits four cherished songs

16 Free ride: how the trans bikers of Original Gents MC are changing the stereotype of the motorcycle club

19 To dye for: meet the biologist extracting pigments from fungi

20 Not-so-minibeasts: going large on the plight of the insect world

22 Grand designs: turning unwanted pianos into concert venues

24

The ultrarunner on injury, mental strength, and how you can join his team in the Wings for Life World Run

26 Luke Shepardson

It’s lunchtime. Grab a sandwich? Not if you’re this lifeguard turned unlikely big-wave surf champion

28 Jodie Harsh

Home is where the beats are, says the DJ, party girl and music-maker

32 Aidan Heslop

We talk to the young British cliff diver who’s transforming the sport with his audacious, next-level leaps

42 Nelly Attar

This inspirational Lebanese mountaineer is a mover and shaker – in more ways than one

50

Inside the fully charged, all-electric, mixed-terrain rally series where family pride is at stake

64 America’s Cup

A state-of-the-art racing yacht is only as good as the crew of humans who sail it. Here’s why…

73 Total ledge: the highs and lows (but mostly highs) of big-wall climbing in Chamonix

79 You snooze, you win: how to get the sleep of your, erm, dreams

80 Block head: why an addiction to Tetris might not be a bad thing

82 Fit for purpose? The phenomenon of FitTok, and how to spot the cons

84 Power trip: everything you need for your next electric mountainbiking adventure

94 Essential dates for your calendar

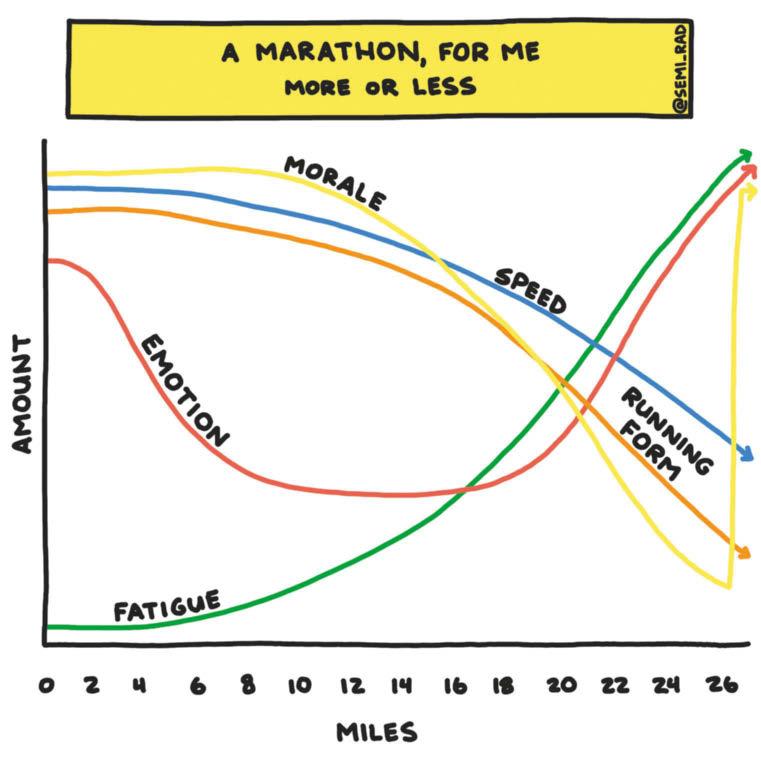

98 Outdoors wisdom from Semi-Rad

50

Scraping victory: World RX races may be short and fast, but they’re no less punishing

Prior to this project, David Nogales Tarragó was a novice at photographing river sports. But when you’re invited to Iceland to shoot a giant of kayaking – Aniol Serrasolses (pictured) –anticipation beats trepidation. This image, shot at the 20m-high Aldeyjarfoss waterfall – “one of the most beautiful I’ve ever seen, because of the energy of the water and the strange basaltic stone formations” – won the Spaniard a semifinal place in global photography contest Red Bull Illume. dnogales.com; redbullillume.com

They may resemble Hot Wheels from this distance, but you’re looking at two eras of excellence in motor-racing engineering. Formula 1 legend Sebastian Vettel’s 2011 Drivers’ Championship-winning RB7 (top) and the Tatra T607 – the 1951 Czech F1 car that never was – were brought together by lensman Jirí Šimecek. For his Time Lap project, he shot them racing side by side, using an era-specific camera for each, to highlight advances in photography and motorsports. Sadly, this is the closest the T607 ever got to elite competition – the Cold War scuppered its plans. jirisimecek.com

You don’t see a “Jesus-like kick-flip out of the Great Salt Lake” – as photographer Dan Krauss calls it – every day. In fact, you almost didn’t see this one. The Salt Lake City native was prepping submissions for Red Bull Illume when, he says, “I realised I’d shelved an idea I had tech-scouted the previous year: a unique look at forced perspective to create a surrealist dystopian environment.” With snowboarder and skater Jack Hessler on board (where else?), Krauss rebooted the project, bagging himself a semi-final spot as a result. dankraussphoto.com; redbullillume.com

“I’d long heard about a certain location [where] some pieces of torn-apart windmills had been left to rot,” says Spanish photographer Ismael Ibañez Ruiz, “so my [BMX rider] friend Sergio Layos and I decided to take a look. It was love at first sight… Curves, lines, hips and transfers galore.” Ruiz’s image won him a semi-final place in the ‘Masterpiece by SanDisk Professional’ category of Red Bull Illume, but sadly this BMX wonderland has since been destroyed. At least we have the photo. Not as much fun to ride, mind. ismaelibanezphoto.com; redbullillume.com

ELLIE GOULDING

ELLIE GOULDING

The award-winning British singer-songwriter revisits four songs that have played a crucial role in her musical education

A pop career wasn’t always assured for Ellie Goulding. Raised by her mum in a council house in Herefordshire, with three siblings – her funeraldirector dad left when she was five – Goulding went on to fail music at A level. But she’d been writing songs since the age of 15 and possessed ambition to match her talents. Now 36, she has three platinum albums to her name, along with two BRIT Awards, and a Grammy nomination for her 2015 hit Love Me Like You Do. To mark the release of her fifth studio album, Higher Than Heaven, the mother of one waxes lyrical on four songs that have inspired her. elliegoulding.com

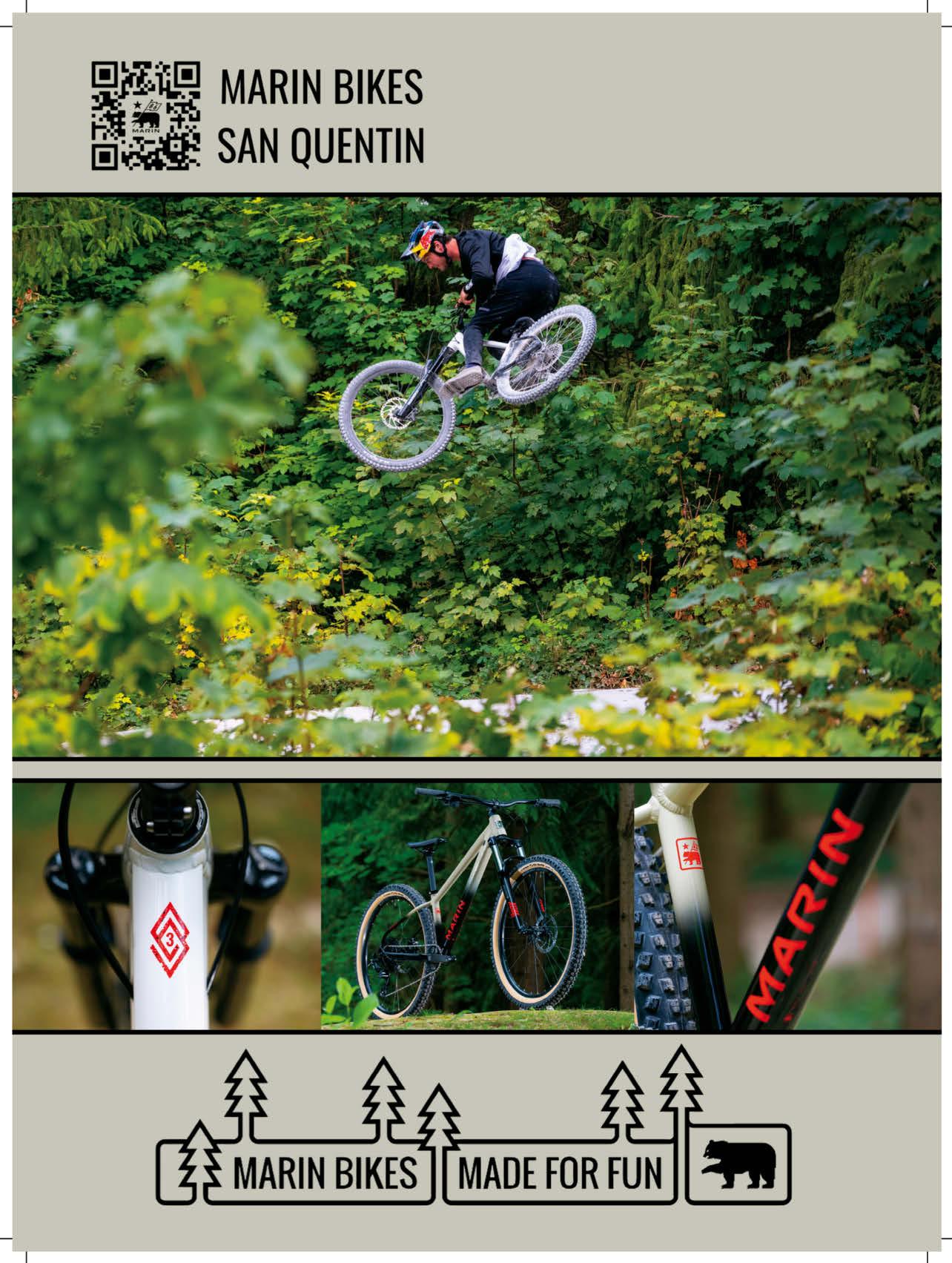

Blur Parklife (1994)

“This track shaped me as a lover of music, because it was the first song I ever bought and it kickstarted my love of indie and rock. It was just the most visceral kind of reaction to music back then, and I think we need that right now. It’s harder and harder to just sit there and listen to ballads about how depressing everything is.”

The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill (1998)

“This opened up a whole other world. It changed things, because it made me want to sing. I loved how personal it was, I loved the tone of her voice, I loved the inflections in her voice, I loved how powerful and direct it was, I loved the energy. It was really groundbreaking.”

Fleetwood Mac Dreams (1977)

“Dreams is a classic. I just didn’t know that something could sound so good! [Laughs.] I’m jealous of anyone listening to this song for the first time, and, of course, people are hearing it on TikTok now. I first discovered it while listening to a friend’s radio. I was just like, ‘Wow, this is such a beautiful song.’ It was like a revelation for me.”

Hanging On (2011)

“This song is a bit more modern – I actually did a cover of it. It’s a combination of this choral voice, very high, and music that’s hip-hop influenced but like a choir, ethereal. It’s impossible not to love, it’s so beautiful. And it’s like nothing I’ve ever heard before. It’s just amazing. Check it out!”

As a trans man, Dakota Cole didn’t feel accepted by other bikers. His solution? To start a new kind of motorcycle club

When Dakota Cole is out with his motorcycle club, he likes to ride his Honda Shadow 750 at the back of the group, where he can see his brothers making the most of the open road.

“I love seeing massive groups of motorcyclists,” the 31-year-old says. “Before we got a road captain, I used to lead, but I didn’t like that too much. As soon as we got a captain, I moved to the back… For me, being on a motorcycle is the ultimate feeling of freedom. You’re not encased in a car; you’re just going down the road feeling everything.”

Cole is co-founder of the Original Gents MC in Kansas

City, the world’s only motorbike club for transgender men. But until Cole helped establish the club, the freedom he felt on a motorcycle was at odds with his experience of traditional biker settings, which he found “very judgemental”, he says. “It’s not trans-friendly. I hate to say this, but cis white men on motorcycles are misogynistic and prejudiced. I knew that if I ever joined a club, I’d have to be stealth [to pass as cisgender] from beginning to end.”

And so, in 2020, Cole co-founded the Original Gents MC, which – contradictory to the reputation of motorbike club culture for illegal activity and aggression – is based on moral values: “Our number one rule is to always treat people with respect.” Choosing a name was the next crucial step and it required careful consideration. “We wanted a name that conveyed we were trans men, but without outing ourselves,” he says. “That can be dangerous – sometimes you see the Pride flag and it makes you a target, especially if you’re in the middle of the US.”

Ultimately, Original Gents MC fitted because “it plays on the fact that even though we were assigned female at birth, we were men from the beginning”.

The number of members has now doubled from the original four to eight, who, aside from being trans men and bikers, are from all walks of life; Cole is a computer technician for federal government, while others work in insurance, hospitals and car dealerships. But every month they proudly ride together.

Out on the road, the Original Gents MC might look like any other motorcycle club, but its very existence is activism in action. It provides safe, inclusive, non-judgemental spaces such as open rides for non-members, monthly bike nights at an LGBT brewery in Kansas City, and a memorial ride on November 20 every year for the Transgender Day of Remembrance.

“A motorcycle club badge has your name, logo and usually your territory,” says Cole. “But we don’t claim territory; we’re not that kind of club. Ours says ‘Brotherhood’ instead.” originalgentsmc.org

This molecular biologist is bringing sustainable colour to the fashion industry, courtesy of the wild world of fungi

It was in 2020 that fungi began to take over Jesse Adler’s life. The biomolecular scientist was working for Pangaia, a materials science fashion brand, during a year’s break from her MA in Material Futures at London’s Central Saint Martins (CSM) and looking for a topic for her final thesis. Then inspiration struck.

“I noticed that there was a need for more colours, more variations, higher performance; things that looked synthetic but were natural,” says the Detroitborn 26-year-old. “Then I saw Fantastic Fungi [a 2019 film by US director Louie Schwartzberg] and I was in awe of all the colourful fungi out there! So began the rabbit hole…”

Adler saw the potential in the world of fungi – organisms that include yeast, mould, lichen and mushrooms – for creating vibrant, environmentally friendly pigments. Until the mid-1800s, dyes were created by “mining, hunting and harvesting”, she says. Extracted from plants, minerals and animals, they were natural but not necessarily sustainable. Then, in 1856, British chemist William Henry Perkin – only 18 at the time –accidentally created the first synthetic dye, a purple he named mauveine, while searching for a treatment for malaria.

Today, most dyes are made from fossil-fuel derivatives and, as such, aren’t renewable. They have also become a source of pollution in our waterways, and, Adler says, “some of these colourants are more toxic than we ever realised”. She believes

mycology (the study of fungi) might have the solution. “The reason there are pigments in these organisms is because nature doesn’t see beauty, only function. For example, a wood decay fungus deposits its striking turquoise pigment as it grows and digests a log to act as antifungal protection, as if to say, ‘This is my territory –nothing else can grow here.’”

Working with a cosmetic formulation chemist, Adler created a make-up collection, Alchemical Mycology, to show potential commercial uses for fungi-derived dyes. Prototype eyeshadows, eyeliners, tinted serums and lipsticks were made in shades of red, yellow, brown, purple, green and blue – all extracted from lab-grown or ethically foraged fungi.

“Make-up was a provocative way to tell this story,” Adler

says, “but now I’m researching how to extract these pigments more sustainably and create different outcomes. The dream is for this to become as scalable as brewing beer.”

Now a self-described “mycological alchemist”, Adler is continuing her work in a research fellowship with CSM and the Jan van Eyck Academie in the Netherlands, exploring the many possible real-world applications of fungi-based pigments, from cosmetics and food to textiles and art supplies.

After a year spent delving into this field, fungi continue to surprise Adler every day. “I got an amazing acid green from some ethically foraged lichen the other day,” she says. “But I was supposed to get orange. That’s the beauty of nature!” jadlerdesign.com

Photographer Levon Biss is turning minibeasts into giants to show the true scale of their plight

When London photographer Levon Biss (pictured with his camera rig, above) came to shoot the giant Patagonian bumblebee for his 2022 project Extinct & Endangered, a collaboration with the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York, he tried an unconventional approach: he shot the insect from underneath. “It looks like it’s got a big mane on its back,” Biss says. “It’s an arresting image – you don’t normally see bees photographed that way.”

Upending our perspective on insects is at the heart of the project, currently on display at the AMNH, and online at extinctandendangered.com.

Extinct & Endangered features 40 extraordinary photos of creatures that are lost – or close to being so – for ever, from the Rocky Mountain locust (last seen in 1902) to Australia’s rarely spotted Christmas beetle. Biss photographed specimens from the AMNH’s 20-million-strong collection and enlarged the images – some to as big as 1.4m by 2.4m –for maximum impact.

A 2020 study in the journal Biological Conservation reported

All in the detail: (clockwise from top left) the ninespotted lady beetle, Luzon peacock swallowtail butterfly, giant Patagonian bumblebee, and lesser wasp moth

that our planet has lost five to 10 per cent of its insect species over the past 150 years. “It’s hard to quantify the rate of loss, because of the difficulty of monitoring them,” says Biss. “Insects are the building blocks of virtually all ecosystems. And if you don’t share an ecosystem in the right way, it gets out of balance. We need education on insects – they’re not horrible creepy-crawly things.”

Indeed, his images highlight the insects’ intricate beauty. But creating such exquisitely detailed photographs isn’t straightforward; Biss uses a homemade photography rig with microscopic lenses that can be moved in minuscule increments. “Generally, the camera will move forward around seven microns –that’s about one tenth of the width of a human hair,” he says. “When shooting at high magnification, you end up with a shallow depth of field. To get around that, you take lots of slithers of focus, creating a stack of images – maybe 500 – and then you use software to squash those together, giving you an image that’s fully focused from front to back.”

Biss splits each insect into around 25 sections, each photographed separately and with custom lighting – for example, backlighting a wing to highlight its structure. The final image is pieced together from more than 10,000 separate shots, which takes around three weeks. In total, Biss’s project took two years. But, he says, it’s worth all the meticulous work.

“When you view something at high magnification, you’re seeing things in a completely different way. With insects, I love looking at the engineering; they’ve adapted to their environment in such an impressive way. But then, when you’re working with an extinct insect, it’s humbling to know this thing will never fly again. Nature has evolved over thousands of years to create this creature, but now it’s not there. It’s a fragile thing.” Extinct & Endangered is at the AMNH, and the book Extinct & Endangered: Insects in Peril is out now; amnh.org

PIANODROME

These Edinburgh musicians have found the key to keeping old pianos out of landfill

A hundred years ago, the piano was a focal point in many a living room; a status symbol and source of entertainment at the heart of the family home. But thanks to changing lifestyles, technological advances, and living space being at a premium, subsequent years have seen it replaced by the TV, the computer and mobile devices. As a result, hundreds of pianos – neglected and out of tune – have become destined for landfill.

This is what Edinburgh musicians Matthew Wright and Tim Vincent-Smith discovered seven years ago when the latter got talking to a piano mover he had hired, named Jerry. VincentSmith, who’s also a woodworker and a designer, asked if Jerry had any pianos going spare; within a few weeks, five had appeared on his doorstep. “They just kept coming,” says

Wright, who plays alongside Vincent-Smith (pictured below, left, with Wright) in musical trio S!nk. “Tim started dreaming about what could happen with these pianos, and he came up with the idea of making an amphitheatre. Over a couple of years, we began taking apart pianos and building prototypes.”

In 2018, they opened their first official Pianodrome at the

Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh – a month-long residency as part of the Festival Fringe. The unique, 100-seat, in-the-round arts venue was constructed using more than 40 unwanted and repurposed instruments. “These pianos are so beautifully put together,” says Wright. “It’s partly out of respect that we’re doing this. We’re looking after them on their way to the dump. We’re intercepting them and giving them new life.”

The pianos are graded using a four-tier system, with some kept whole – each venue includes instruments that are playable – and others deconstructed to varying degrees to create ballast, accessible seating and gangways. “It’s a nose-to-tail construction philosophy,” says Wright. “We’re working with materials solely from pianos, right down to the screws, planks and structural components.”

Key to Pianodrome, though, is that “no working instruments are harmed in the making”. Its Adopt-A-Piano scheme brings restorable instruments back to life, giving them a retune and a new home. Wright and VincentSmith estimate that, to date, they have rescued around 300 pianos, with projects including a sculpture trail for the 2021 Leeds International Piano Competition, the building of a second venue for a 2022 Fringe run at Edinburgh’s Old Royal High School, and the creation of America’s first Pianodrome for the Charlotte SHOUT! arts festival in North Carolina this April. The two existing UK Pianodromes are in storage, ready for their next installation.

“We want people to appreciate the heritage and the stories bound to these pianos,” says Wright. “There are decades of family experience and love and music-making in them. This is a way of allowing these pianos, which have imbued all this stuff throughout their lives, to breathe and communicate with humans once again.” pianodrome.org

Tom Evans

Tom Evans

Driving a pick-up truck through his temporary hometown – Sedona, Arizona – British ultrarunner Tom Evans is beginning to look like one of the locals. A cowboy hat, he jokes, is next on his list. Evans is on the first of three planned stints of altitude training Stateside, and while the 31-year-old misses his home in Loughborough, his wife Sophie, their two dogs Rocco and Poppy, and their brood of rescued batteryfarm chickens, he’s laser-focused on his upcoming American challenge.

The 100-mile (161km) Western States Endurance Run in California this June is a race Evans calls “the Super Bowl of trail running”. He’s also preparing for the Wings for Life World Run on May 7, a unique annual event that raises money for spinal-cord injury research and sees thousands of runners across the world race against a moving finishing line while being chased by a virtual Catcher Car.

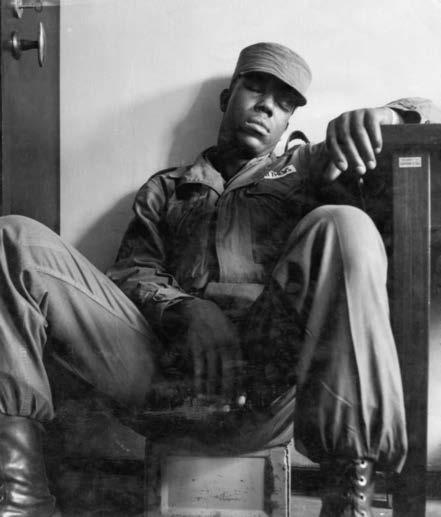

Evans is putting together his own team to take on the challenge, and is more than qualified to be captain: since his statement-making thirdplace finish in the 251km Marathon des Sables in 2017, the former British Army officer, originally from Sussex, has established himself as one of the world’s top ultrarunners. But it’s another podium placing –in the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc last August – that he’s most proud of, coming as it did just a year after major knee surgery.

Here, Evans talks to The Red Bulletin about the emotional investment of ultrarunning, and that big injury comeback…

the red bulletin: What do you love most about ultrarunning? tom evans: It’s not just a physical challenge but arguably a bigger one mentally. Your mind is the thing that unlocks it. I want to see how far I can push myself, and I’m constantly searching for that limit. Western States is described as ‘a life in a day’ – you go through the highest of highs and the lowest of lows, and it’s how you deal with them. You learn so much about yourself. In this sport, there are more uncontrollable factors than controllable ones, so you have to solve problems and make tactical decisions quickly. I didn’t get the same buzz from road or track running.

What has been the biggest highlight of your career?

I had major knee surgery in August 2021 and, a year after that, I raced in the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc. It’s 170km with 10,000m of climbing, going through three countries. My goal for that race was to be on the starting line; I ended up finishing third. [It helped me] put all my rehab demons to bed and say, “I do belong here.” I was so emotional, because I’d worked so hard. I did believe I could do it, but deep down there was a huge question mark.

How does it feel at the finishing line after putting yourself through such a gruelling experience? Racing is relatively easy – I race four or five times a year, but I train 350 days and there’s no one watching and cheering for you [then]. So if a race goes well, it’s almost a relief that everything I did worked. It’s really emotional, both the victories

and the losses. I heard a phrase on a podcast last year: “Don’t let the highs go to your head or the lows go to your heart.” I think that’s so important. I want to be stood on the starting line knowing I’ve left no stone unturned.

Why should people join your team for the Wings for Life World Run on May 7?

Running is such an individual way to express yourself, but a team is only as strong as its parts. I want to create this team to hold me accountable to then hold all the others accountable. It’s that tribe mentality – a collective of individuals coming together to achieve something we couldn’t do on our own. I might have people in the UK, the US, Australia, Argentina, Brazil, wherever. We’re all doing it together. And Wings for Life is a charity I’ve seen do incredible work. I want to raise as much money as I can.

How far are you hoping to run?

I ran 63km last year in Vienna. So… 64?

Are your tactics different in a race like this where you’re trying to avoid the Catcher Car rather than reach a set finishing line?

It’s really important to trust yourself, go out at a pace and hold that pace. Whether I have to run, walk or crawl, I’m just going to keep going and try to get as much distance as I can between myself and the Catcher Car. It’s the same mindset that everyone should go into the race with: as long as you keep moving in the right direction, you’re doing an incredible thing. You’ve just got to put one foot in front of the other. Running is such a basic sport; in racing, all you’re trying to do is get from A to B as quickly as possible. Whether it’s Usain Bolt in the 100m or Eliud Kipchoge running the marathon, we’re all trying to do that same thing. The Wings for Life World Run starts at 12 midday on May 7; wingsforlifeworldrun.com

Scan the QR code to join Tom Evans’s team in the Wings for Life World Run

RACHAEL SIGEE

He may have plans to conquer the US, but first the British ultrarunner has his sights set on a challenge that’s closer to home – and he wants you to join him

“Wings for Life is a charity I’ve seen do incredible work”

1978] was the first lifeguard on the North Shore with a perfect record of rescues. It’s a testament to how good of a waterman and lifeguard he was. He performed so many selfless acts, ultimately sacrificing his own life to get help when the canoe he was in capsized at sea. It’s just about honouring his legacy.

Did that help you overcome the pressure of competing?

Words RACHAEL SIGEE Photography PHILIPP CARL RIEDLIt had been seven years since conditions were right for the Eddie Aikau Big Wave Invitational to take place, but on January 22, 2023, word came through: the waves were good. The Eddie was a go.

The Eddie – a surfing event held only when waves exceed 30ft [9m] in height – brought thousands of people to Waimea Bay on the North Shore of Hawaiian island O’ahu, where Luke Shepardson works as a lifeguard. The 27-year-old North Shore native had long dreamt of competing in the Eddie, and had been invited to sign up after organisers saw him surf the break back in 2016. So, this year, despite being on duty that day, Shepardson had permission from his boss to take part during his lunch break.

When the time came, the Eddie novice donned his competition jersey, ran into the waves he first rode at the age of 13 – and won. Shepardson scored an incredible 89.1 out of 90, beating some of the world’s best surfers and winning the $10,000 prize – and the respect of the surfing community.

the red bulletin: When did you start surfing?

luke shepardson: I grew up surfing with friends and family. I’ve always done it. It’s what I love to do. It keeps me in the present moment and is always there for me. It helps me get away from stuff if I’m having a hard day. Every time you get out of the water, you go back to whatever you were doing feeling better.

Did you have dreams of making it as a pro when you were younger? I did, but it wasn’t for me. I was sponsored by a local surf shop, North Shore, but they didn’t have a ton of money. I’d feel so anxious whenever I paddled out in a competition jersey. Total butterflies. I’d make mistakes that I otherwise wouldn’t have. I [won a few competitions], but generally I was putting too much pressure on myself. It took the fun out of surfing.

Why did you become a lifeguard?

It had always been a dream of mine. I tried out at 18 and then again at 20, but they wouldn’t let me in, because I was taking all this time off for surf competitions. I had my son when I was 23, and I decided I needed something solid, so I quit competing and got accepted as a lifeguard. That last competition, I made it to the semifinals. Because I knew it was my last, I didn’t put any pressure on myself.

What has been your gnarliest moment as a lifeguard?

Two of my friends got injured a couple of years apart, both at [local break] Pipeline. I saw my friend nosedive from the top of a wave and go down pretty hard. He didn’t come up, and a few surfers brought him to shore. He was non-responsive. I performed first aid and eventually he responded. But it was a long road until he was back to full health. The same kind of thing happened with another friend a few months ago.

Given the danger of big waves, what’s the appeal of the Eddie? It had always been a dream to compete. Eddie [Aikau, a local legend, who died in a canoeing accident in

Yeah, it had been a lifelong ambition because of him. And it was right there on the beach where I worked. I was overwhelmed when I took part – I cried when I put the jersey on. It’s a huge deal to everyone in the sport.

What was it like to take part?

I was preoccupied with work during the day, but when I grabbed my jersey for my heat I started tearing up. I was so stoked to achieve this lifelong goal – I was blown away that it was coming true. To be surfing among legends I’ve looked up to my whole life, and to be part of that energy, was unbelievable. I surfed as best I could, then went back to work.

Did you ever think you had a chance of winning?

The competition is in two rounds. Right before my second round, I was told the scores and what I needed to win. I knew I had a couple of good waves in my second heat, so I did have a thought I could win, but of course you never know. When they announced it, it was… I don’t even know how to explain it. The emotion that filled my body was just… I was in shock. It was one of the best moments of my life.

Has winning changed things?

I’m only really starting to process it, because on the day itself there were thousands of people I had to keep an eye on. But it’s all pretty surreal. I don’t want to give up being a lifeguard, but I would like some sponsors to help me go surf dream breaks in Tahiti and Africa – although the cold water there kind of scares me. I’m done with competitions, but I’ll never stop surfing. Ever.

Instagram: @casualluke

How the 27-year-old unsponsored lifeguard claimed victory in surfing’s biggest event – on his lunch break

“I surfed as best I could, then went back to work”

DJ, producer and songwriter Jodie Harsh found a home and happiness on the club scene as a teenager. Now she hopes her music can help others find the same thing, too

Words LOU BOYD Photography THOMAS KNIGHTSJodie Harsh is up for a party. The London-based DJ, music producer, songwriter and self-proclaimed “reigning Queen supreme over international nightlife” has been at the forefront of the UK’s club scene for the past two decades. A fixture at iconic noughties club Circus, and a gifted club DJ, over those 20 years Harsh has been pictured out on the town with everyone from Kate Moss and Paris Hilton to Lady Gaga and Amy Winehouse, and has gained a reputation as one of London’s happiest and most hedonistic party girls.

When clubs suddenly closed in 2020 at the start of the pandemic, however, Harsh’s day job and exhilarating lifestyle evaporated overnight. With a year of festival bookings, DJ gigs and public events cancelled, she made the choice to stay positive and focus on creating a party from home instead, making and releasing her own music for the first time. Her debut original single, My House, which dropped in November 2020, revealed that not only did Harsh have a musical talent away from the DJ decks but she had a sound that people loved. The beat- and hook-heavy track quickly totted up millions of streams online.

“People were stuck at home, missing the clubs and the fun,” Harsh says. “I like to think my track provided them with a bit of that feeling for a few minutes. It started getting played quite a bit on the radio, and it was nice to think that I was bringing some fun to people’s day during those months [in lockdown].”

Now, with further successful singles to her name, more music on

the way, and an upcoming headline show in London on the horizon, Harsh spoke to The Red Bulletin about her experiences of the changing club scene since the early noughties, how finding a home on the scene was so crucial to her younger self, how she found her own sound, and why nightlife is such an important element of UK culture.

the red bulletin: Your music perfectly encapsulates the joy of being on the dancefloor. Is that something you consciously try to express with your sound?

jodie harsh: I’ve spent my life on the dancefloor, since I was 15, so I’ve always just been a fan of the happier side of music, like disco and funky house. Now more than ever, after what we’ve been through over the past few years, I think my mission statement in life is to provide a bit of an escape and a good time for other people through music.

Most of your career up until 2020 was club DJing and remixing other people’s tracks. What pushed you to focus on your own music? The pandemic, I guess! My single My House came out halfway through the pandemic and blew up. That became my crossover moment. It sounds so silly and analytical, but that was the moment when I felt like my music went from being underground – just for the people already following me – to living in the real world outside my scene.

Can you remember when you first played your own music in a set? Definitely. It was a terrace show at Night Tales in east London after the

first lockdown. That was the first time I’d done a show that was just me and wasn’t attached to a club brand or to someone else’s show or a festival. It was just my name on it; people were coming to see me. When I played My House, everyone started singing along, and I just thought, “Wow, this is connecting.” Now, when people are at my events, they’re always singing my lyrics back at me. I never thought I’d get to experience that.

Tell us about your latest single, Hectic. How did that come about?

I’m really proud of it. I wanted to write a song about going out with your friends on a proper night out, and when we came up with Hectic I left the session thinking, “I don’t know whether that’s completely genius or if we’ll be leaving it on the cutting-room floor.” When I was in Australia last year, I heard loads of people constantly using the word hectic, and I thought, “Oh, that’s fun.” It reminded me a bit of Dizzee Rascal’s Bonkers

A good night out should be hectic, right?

Oh, one hundred per cent. Good nights should always be hectic. I think that word summarises the happy chaos of when you’ve got the whole gang together and you’re going to a club. You’re glad to be together having fun, and it’s about pure escapism. It’s like, “Right, fuck it, we’re going out. Let’s go and have a good time.”

As well as launching your music career in 2020, you started your own podcast, Life of the Party What kind of conversations do you have on it?

We tell stories about nightclubbing and how it’s an important part of our culture. It’s great to hear stories of how people have met their loved ones and friends in clubs, and how clubbing developed their tastes, whether that’s music, clothes or even who they fancy.

Who have been your most memorable guests?

Nile Rogers was amazing. He’s one of my heroes. He was at [legendary

“I just want to bring a little bit of extra joy into people’s day”

’70s/’80s New York nightclub]

Studio 54, and it was amazing to hear those stories. And Fatboy Slim was great, of course. We also had Tom Daley on, who’s obviously a sportsperson and therefore hasn’t been really allowed to go out and let loose for much of his life. Also, Self Esteem was funny, because she doesn’t like going out, so we dissected why that is – I became her therapist for an hour.

What is it about going out and clubbing that's so important in your life?

Nightlife has always been about connection. It’s a moment to go out and forget about your very real life outside by going into a dark room, hearing the music you love and letting loose. It’s about meeting someone, it’s about kissing someone, it’s about finding your people and hanging out with your friends. It’s about sharing a moment and an experience. Sharing music and dancing together.

A place of belonging?

Exactly. I remember walking into a club for the first time. I was very young – 15, about to turn 16 – with

an excellent fake ID, and for the first time I saw all these people who were like me. Growing up as a little queer boy, I felt different and disconnected from other people. When I stood in a nightclub for the first time, hearing the music I love, among thousands of people I could identify with… for the first time in my life, I felt like I was home. Life experiences happen in nightclubs. You learn about yourself from those rooms with their lights out. Those loud, dark rooms have always been very, very important.

What’s your opinion of the club scene in London today?

People love to complain about the state of clubs, but I think it’s probably always been that way. If you went back to the amazing clubbing heydays of the ’80s and the ’90s, I’m sure that people then

were complaining about how all the best places had already gone. Maybe we never appreciate what we’ve got till it’s gone. Personally, I think there’s loads going on. Just look at my corner of the nightclubbing landscape: queer clubs. Really exciting things are happening at places like [north London club] Adonis, for example – you see thousands of people pouring out of those nights, and it’s hard to get in.

Do you see a change now from how clubs were before the pandemic?

Venues have closed, and that is, of course, really awful. But things die and other things are born – that’s just the way of art and of life, isn’t it? There’s still so much on offer, especially if you travel around different parts of the country. There are whole new scenes starting, and they’re growing so fast. In times of struggle – especially now when we’re all struggling financially –clubs will become more DIY again. I think things are maybe going back to the source a little more.

Tell us about your headline show at The Outernet in London. Will you be playing your own music?

It’ll be a visual live show playing all my music, everything I’ve released, and probably some extra bits I’m working on. I really enjoy marrying the visual side of what I do with the musical. I’ve always liked artists who do that, whether it’s Grace Jones back in the day with her one-woman show, or Madonna’s best tours. I want the show to feel like a 360-degree experience. It's kind of boring when it’s just a DJ playing music – I really enjoy extra elements like big sets, massive LED screens and dancers. It’s my biggest-ever headline show. Exciting, but also a lot of pressure!

What are your aims for this year?

To bring music to more ears and bring a bit of happiness to people. Whether it’s a DJ set for 90 minutes or a three-minute tune on the radio, I just want to help to bring a little bit of extra joy into people’s day or night. That’s what I’m here for, I think.

Jodie Harsh’s headline show takes place at The Outernet in London on April 15; jodieharsh.com

“When I stood in a club for the first time, it felt like I was home”

Need to shift a bulky load? The Cargo Hybrid is the environmentally friendly solution you‘ve been looking for: simple, easy to ride and endlessly versatile. Powered by Bosch‘s fourth generation drive system and featuring an EPP foam carrier, it‘s the best excuse yet to ditch the car.

CUBEBIKESUK / www.cube-bikes.co.uk

CUBE CARGO HYBRID

CUBE CARGO HYBRID

At the age of 12, British cliff-diver AIDAN HESLOP decided that one day he’d be a world champion in the sport. Now, eight years later –and armed with the two most difficult dives in cliff-diving history – he may be about to make that dream a reality

Words SAM RICHES P hotography GIAN PAUL LOZZA

ore than 20,000 people stand watching from the banks of the waterfront, the decks of anchored yachts, and the crowded balconies of high-rise towers. All eyes are on a 27m-high platform jutting from Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art. It’s June 2022 and, at the first stop of the Red Bull Cliff Diving World Series, nine-time world champion Gary Hunt has just landed himself in first place. But there’s one diver still to leap.

Aged 20 and just starting his first full season of competition, Brit Aidan Heslop isn’t an obvious contender for the win. But for Hunt there’s a kicker: Heslop is about to attempt the most difficult dive in the history of the sport. To achieve it, he must nail four forward somersaults and three-and-a-half twists pike in the 2.8 seconds it’ll take him to reach the water – something none of the more seasoned divers watching from below have ever attempted, let alone landed.

The anticipation is palpable. The live heart-rate monitor shows Heslop’s bpm steadily rising as he stands on the platform, but – despite being under the most intense pressure of his so-far short career – the young diver has no problem listening to his head rather than his heart. He breathes in deeply, blocking out the noise around him, focussing on what he’s about to do. He starts his run-up and launches himself upwards and into a series of impossibly quick twists and spins. As Heslop hurtles toward the water, he’s folded forward at the waist, hands clasped behind his thighs before straightening out and bracing for impact, his body tensed and taut to absorb the coming shockwave. He enters the water feet-first, at a speed of more than 80kph.

Hunt begins to clap even before the judges have awarded their scores. And

when they do, they confirm what the 38-year-old diving legend already knows: Heslop is top of the podium, having secured his first-ever win in the series.

“That, folks,” announces the commentator, incredulous, “is the new generation coming in red-hot.”

In February this year, Heslop stands on a platform 20m above the comparatively calm, warm water of the Olympic Pool in Montréal, his head just a few metres from the ceiling. From this vantage point, he can see almost every inch of the sports centre – the largest aquatic facility in Canada, and one of the few places in the world to accommodate such high diving indoors. Since moving to Montréal last September from Plymouth in Devon, it’s become a second home for Heslop. “If I want to be the best I can possibly be,” he says, “this is the one place in the world where I need to be.”

The upper limit of Heslop’s natural ability is unknown even to him. Aged 16, he already had a reputation as a prodigy after his cliff-diving debut in Polignano a Mare, Italy, in 2018 made him the youngest person to ever compete in the World Series. Then his performance over the eight global stops of last year’s Series saw him take second place overall and make him the cliff diver most likely to

challenge eventual 2022 champion Hunt for the crown this time around.

Gary Hunt is Heslop’s idol and inspiration. Described by his peers as the “Michael Jordan, Muhammad Ali and Tiger Woods” of cliff diving, he’s part of the reason Heslop is where he is today. Born in Chelmsford, Essex, but raised in Plymouth, Devon, Heslop spent his youth skateboarding and BMXing the narrow, cobbled streets of the port city. He had also tried diving, inspired by fellow Plymouth native Tom Daley, but then a friend showed him a video of Hunt performing a back triple quad – a backwards triple somersault with four twists – and everything changed.

Heslop initially thought the video was fake. He’d never seen anything like it. He

”I want to dominate the sport. I want to be untouchable”

Aiming high: Heslop has his eye on first place in this year’s Red Bull Cliff Diving World Series

Drop zone: Heslop performs a dive at Polignano a Mare, Italy, in the World Series last September

“I’m very good with my limits and knowing where they are, what I’m physically capable of”

couldn’t shake the image of Hunt twisting and somersaulting through the air. The wiry and rumbustious kid wondered if he might have a natural inclination for this, the most extreme form of the sport.

The first time Heslop leapt off a 10m diving board, he knew he was hooked. It wasn’t just the adrenaline, though that was part of it, but also how quickly he progressed. With every dive, he felt himself getting better. He entered his first junior event that year, competing at a height of 15m. Not much to him now, but it felt pretty high at the age of 12.

“Diving is just something I clicked with,” he says. “From the very first day I tried it right up to now, things kind of come naturally to me. At 12 years old, I was convinced that one day I’d be a high-diving world champion.”

Heslop’s parents used to ferry him to competitions in their motorhome, his mother often moved to tears of worry as she watched her son scale ever loftier heights. But she accepted his love of it, even as it became clear it was high diving that was Heslop’s real passion. “The creativity made me fall in love with the sport,” he says. “And with high diving it’s the adrenaline. That’s a huge factor.”

He swapped his parents’ motorhome for aeroplanes as his competitions increasingly required travel to more exotic and far-flung locations. And all the while, Heslop was progressing, taking in the science of each aerial manoeuvre and transition, improving on the grace of his execution to move away from his early rep as a ‘scrappy’ diver.

“In my early days I was labelled as the scruffy guy who went for the big tricks,” he says. “I still go for the big tricks; I just make them look pretty now. The scruffiness is still sometimes a weakness, because I’m up against divers from a gymnastics background who live their life with straight legs and pointy toes. That’s not quite me; I have to put some thought into it. But when I learn a new skill, it’s like, ‘Yeah, I understand that. I’ve got it. I’ve done it.’ There’s a limit to [what you can achieve] but I don’t think I’ve hit mine yet. I’ll know where it is when I get there.”

The search for this limit has brought him to Montréal, where he’s training under Stéphane Lapointe, who he describes as the world’s best high-diving coach. Heslop lives here with his Canadian girlfriend and fellow cliff-diver Molly Carlson.

When Heslop toppled Hunt for the first time to take his first World Series win at last year’s Boston stop, Carlson secured her own maiden win at the event. “It was an amazing moment,” says Heslop. “But even when I have a bad competition, it picks me up [to see her hit] her dives the way she can. Every day we go to training together here, it’s just more motivation.”

To access the 20m platform at the Montréal Olympic Pool, divers must climb several flights of stairs, scale a ladder, then stroll a lengthy catwalk as gym goers and recreational swimmers at ground level crane their necks and gawp.

Up on the platform, Heslop bounces on his toes with the assurance of someone still on solid ground. His lithe frame, built for speed and agility, belies his physical strength, evident in the explosiveness that launches him into the air. He pushes off the platform with his back to the water, a small crowd watching him from the poolside. Heslop seems to float for a moment, his body parallel to the pool far below him, before twisting and somersaulting into position in the blink of an eye. His entry into the water reverberates throughout the facility like a small explosion, mixing with audible gasps.

“I think something I have that a lot of others don’t is complete self-confidence,” he says as he stands by the pool, dripping, wearing a characteristic smile, “and the willingness to try dives right on the limit of what I’m physically capable of.”

But this willingness is currently being tested: having executed the dive awarded the highest degree of difficulty score in his sport’s history, to progress Heslop must now find a way to beat it. To that end, he’s working on a back quad

quad, which means adding another somersault and twist to an existing 5.2 degree of difficulty (DD) dive, pushing the DD score to an unprecedented 6.6. For comparison’s sake, the difficulty table for men begins at 2.8 for the required dives and previously reached a ceiling of 5.6 for the most demanding, with each twist and somersault adding 0.4 to 0.6 to the score. If Heslop nails it, he’ll be armed with the two highest difficulty dives in the world this season. And he’ll make cliff-diving history. Again. “It’s moving into new territory that no one’s ever touched, or even come close to touching,” he says. “So it’s definitely nerve-racking. I’m more nervous about this dive than the previous one, because it’s such a step up.”

Heslop’s 6.2 dive has already changed the game. The first time he performed it in competition – at the FINA High Diving Qualifier in Abu Dhabi in December 2021 – it won him gold. Then the dive cemented his place as a permanent competitor at last year’s World Series with his Boston win and then another in Sisikon, Switzerland, leaving Hunt in second place on both occasions. “Beating my hero and seeing him below me on the podium was surreal,” says Heslop. “Not many people get to do that.”

It seems the rest of the pack has yet to catch up. “I believe he’s still the only athlete in the world who can physically achieve this dive,” says high-diving head judge Olivier Morneau-Ricard. Meaning Heslop could compete in 2023 with that same weapon in his arsenal and stand a good chance of becoming champion.

But Heslop’s motivation is pushing himself and his sport to new heights. The way he sees it, the top divers have been pulling off the same dives for years and operating in a bubble of difficulty that he’s ready to burst. “Learning new things and having fun is what it’s all about, I think. I just want to do the biggest dive, pushing my own limit and [those] of the sport.”

According to Morneau-Ricard, Heslop has all the tools to do just that. “[Aidan] has aerial awareness that is out of this world,” he says. “It’s a gift. To get to the point he has, that young, it’s not normal. At the moment, he’s still missing a dive here and there in competition. But with age, more experience and practice, I don’t think anyone will be able to beat him any more.”

The world-class facilities in Montréal are a possible game-changer when it

“In my early days I was labelled as the scruffy guy who went for the big tricks”

Signs of descent: Heslop plunges from the daunting 20m diving platform at the Montréal Olympic Pool

Signs of descent: Heslop plunges from the daunting 20m diving platform at the Montréal Olympic Pool

comes to honing Heslop’s already impressive skill set. Compared with competing outdoors, where divers must account for wind, rain, birds, crowd distractions, and what is often a cold sea churning below them, landing in the pool in Montréal – even from 20m – is a cakewalk. “The water’s so warm you just kind of cut through it,” Heslop says. “The hardest water for us is cold salt water, because that’s the densest. Here, the impact is not so bad.”

The pool’s unique set-up – it also features 18m, 15m, 12m and 10m platforms – can be traced back to Lysanne Richard, a high-diving world champion and former Cirque du Soleil performer. In 2015, the facility was heavily renovated and the 18m platform was installed at her suggestion. Richard saw an opportunity to modernise the building and support a growing sport. About two years later, the 20m platform, which is competition height for women, was bolted into the roof.

Now, Heslop trains at the sports centre three days a week, with two days a week spent at another pool, about 20 minutes away. He also weight-trains three days a week, conducts extensive video analysis, practises in a foam pit, and does trampoline work where divers develop the reflexes to land perfectly, feet first, every leap.

This packed schedule is evidence of a dramatic transformation in the sport in recent years. The environment in which Heslop is developing is very different to the experience of divers like the 38-year-old Hunt. “High divers [training back then] didn’t have access to coaches,” says Morneau-Ricard. “They didn’t have access to facilities, to personal trainers, nutritionists, psychologists. There was no funding.”

Heslop is now part of the first group of international high divers training together at the same place. Rather than training in isolation, which has been Hunt’s preference, this new generation of divers are working together to propel themselves and the sport into a new era. “Having six people here who are worldclass athletes and pushing their limits every day just makes you try harder,” Heslop says. “It’s a bit of competition.”

The group of six is led by Lapointe, one of only a small number of cliff-diving coaches in the world. The Canadian first met Heslop when the Brit was 18, and he says he’s seen huge leaps in the young

diver’s focus since then. “It used to be that every time he stepped on a tower he wanted to do a dive for fun,” says Lapointe. “But now he’s more mature in his reactions. And if he misses a dive, he’s able to come back and hit the next one. A year and a half ago, he would be more up and down.”

The coach says an important part of his job is providing an emotional outlet for the divers, making sure they feel secure and approach competitions with the right mindset. He calls it empathetic listening. “I need to know them. I need to know what they think and what they feel to be able to make sure they’re safe and they’re on point to perform.”

This is crucial in a sport with such high stakes. “If you do something wrong, you can seriously injure yourself and be done with the sport, full stop,” says Heslop. He says it’s a misconception that cliff divers compete without fear. Rather, fear is useful, a necessary reaction for self-preservation. “I think that fear gives you a bit of a reality check, and that’s so important in an extreme sport like this.”

Heslop learnt that lesson early on. When he made his cliff-diving debut in Italy at 16, he landed a few degrees too far on his backside and fractured his tailbone. When he first hit the water, his adrenaline overpowered any awareness of the injury, but for the next six months sitting down for more than five minutes at a time was painful. “That was an awkward one,” he says. “There’s nothing you can do for a broken coccyx.”

But even after setbacks, Heslop doesn’t need much persuading to get back up on the board. “The adrenaline is a part I love,” he says. “When you stand on the [platform] and you’ve got a new dive to learn and your heart’s going, it’s

almost like an addiction, which has always made me want to continue. But I think I’m fairly level-headed, too. I’m mentally prepared for what I’m doing. In my head, I’m going to do this dive and I’m going to be safe about it.”

It’s what’s helping him drill the back quad quad, ready for this year’s World Series. “It’s daunting doing something you haven’t watched someone else do, but I’m treating it like learning any other dive,” he says. “I’ve tried it off the 20m with one somersault less than the final dive. Now I just have to add a somersault in the middle of it somehow. I’m very good with my limits and knowing where they are, what I’m physically capable of. And I think this is within my limits – just. But it’s the hardest thing I’ve ever done.”

The first stop of the Red Bull Cliff Diving World Series is once again set to be held at Boston Seaport this June. It will mark 10 years since a wideeyed, pre-teen Heslop first watched that video of Gary Hunt, and a year since he first managed to beat him to the top of a podium. Heslop hopes this year’s Boston stop will also mark the start of a series that sees him crowned king of his sport. “To know I’m pushing the world champion at 20 years old feels great,” he says. “I really like the position I’m in.”

But Hunt isn’t in any rush to give up the mantle. He’s currently training in Dubai at DuDive, the only springboard and high-diving club in the UAE. No stranger to improvisation, Hunt has been launching himself from DuDive’s rafters as he trains for the upcoming season, toeing a narrow ledge before leaping 20m into the pool below. He’ll come with his own answer to Heslop’s challenge.

Full of the self-confidence that’s got him this far, Heslop says he’s excited to leave the warm haven of the sports centre in Montréal and get back out into the elements. The title is on his mind, but – armed with a dive that will have the designer of the World Series’ difficulty graphic sweating – from Heslop’s vantage point it’s also possible to see much further.

“It isn’t just about the world title,” he says. “I’m pushing my limits to their maximum capacity. I want to dominate the sport. I want to be untouchable.”

The 2023 Red Bull Cliff Diving World Series starts in Boston on June 3. Watch all the action live on Red Bull TV; redbull.com. Instagram: @aidan_heslop

“Diving is just something I clicked with… Things kind of come naturally to me”

Top of the world: Attar summits K2 in July last year –an icy contrast with the desert in Riyadh, where she trained

In 2022, NELLY ATTAR became the first Arab woman to summit K2. And back in Saudi Arabia, where women have long been discouraged from physical activity, she’s become a fitness role model, inspiring millions to move their bodies

Words MAUREEN O’HAGAN

Photography TERRAY SYLVESTER

Words MAUREEN O’HAGAN

Photography TERRAY SYLVESTER

“I’ve learned through life there are plenty of opportunities through challenges”

ou might picture serious mountaineers as a grizzled bunch, but this one grooves. Nelly Attar has danced on her way up Mount Everest, her big curls bouncing wildly before reaching the summit. She’s danced on technical Ama Dablam and on mellow Kilimanjaro. She’s even danced on terrifying K2 this past summer. She’s danced when she’s happy, danced when she’s bored, and she’s danced through fear. For Attar, “movement is medicine”.

Here’s another incongruous fact: this 5ft 2in (1.57m) powerhouse trained to climb the world’s highest peaks from a home base of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. That’s hot, flat desert, not mountain snow and ice. Then there are the rules, both written and unwritten, that for much of Attar’s life gave most women and girls little access to sports or fitness – not as athletes, as spectators, or even in school gym class.

Dancing in public has also been taboo. “I’ve learned through life there are plenty of opportunities through challenges,” she says. “You just have to be creative.”

Attar’s progression as an athlete – from teaching dance classes underground and opening a wildly influential dance studio to completing marathons and Ironmans and climbing the world’s tallest mountains – is indeed a story of challenges and creativity. But that’s only part of it. Her career trajectory, from psychologist to sports figure, tells another story, too, one that reflects how life in Saudi Arabia is changing, and how Attar is helping to change it. “I shifted careers to work in sports, because in Saudi that’s what created more impact,” she says. “Especially in mental health.”

In a country where 60 per cent of women get less than 30 minutes of physical activity a week, simply moving the body can be transformative. The physical struggle – of the climb, of the marathon, of a dance class, or an hour spent at the gym – is a way to deal with life’s other trials: the losses, disappointments, self-doubt, and even the hardest of them all, grief. “It’s the best antidepressant, the best anti-anxiety pill ever,” she says. Which is the story she wants to share with fellow Saudis, with women, and with the world.

In the record books, Attar’s singular achievement to date is her climb of K2, long dubbed ‘the savage mountain’ because, as one early climber said, it “tries to kill you”. It’s a gruelling, weeks-long process that involves a long approach; an acclimatisation rotation; avalanche, weather and rock- and ice-fall hazards; and a looming serac over a steep, narrow passageway that has claimed numerous lives. Last July, she became the first Arab woman to reach the 8,611m summit. But in many ways, another first – one that won’t go in any record books – is just as significant. It involves dance.

If you live in a region where dance performances, clubs and lessons are common, and where music fans dance at concerts, this may be hard to grasp, but until relatively recently, dance and music weren’t permitted in public places in Saudi Arabia. Attar helped open the world of dance and movement to Saudis, which is why we’ll begin the story of her mountain journeys here. It started with a period of personal challenges. Moving to London in 2010 to pursue a Master of Research degree in psychology, she was plagued by anxiety – throat-constricting panic attacks that left her feeling like the world was collapsing. It took months to learn how to cope. She started with stillness, slowing her breath and focusing on just one thing. Then, for a longer-term fix, she turned to movement. “My outlet was sports: running along the Thames, fitness classes, dancing. I tried everything,” Attar says. “When I didn’t train, I wouldn’t feel good.

I’d feel lazy. When I’d start to train, I’d feel better, want to take care of myself more, eat better.”

After graduating, Attar looked for work in London, then in Lebanon, where her father lived, but the job hunt went on for more than a year. In 2013, she finally found work back in her hometown, Riyadh, providing therapy for brain injury patients. But then she had another challenge. In Saudi, women like Attar had few outlets. The few existing fitness options open to women were mostly poorly equipped gyms connected to beauty salons. An Arab woman jogging in public was unusual enough to draw comments. So was simply being outdoors without an abaya – a long, black, robe-like dress. But she knew she had to move.

So she had the idea of offering female colleagues dance lessons after work. It was a scary prospect at first, but the move “changed my career and, later down the line, my life”. As the classes became more popular, she began travelling around the city, to embassies and other private venues, teaching dance underground. Her mother and stepfather had another intimidating idea: she could open her own studio. This was 2017, and it was a risk. That year, a 14-year-old boy was detained after doing the ‘Macarena’ on a city street. There was no clear path to get a business licence. Some conservative elements couldn’t accept the idea of women doing anything athletic. She could be in trouble if discovered. She wasn’t even sure if she was a good-enough dancer. “I did one thing consistently right,” she said in a 2021 TEDx talk. “Regardless of how it looked, I took that imperfect step forward.”

She named the studio Move. Open only to women and girls, it offered everything from Afrobeat to belly dancing and hip hop. But learning dance steps was

only part of the appeal. Women would arrive early just to bask in the warm, supportive environment. Girls would bring their mums, who would hang around to watch, learn and socialise. On the side, Attar was organising other activities for the larger community, too – hikes, running events, anything to get women moving. “There are infinite possibilities. Basketball, dance, playing with your kids. Movement is such a big umbrella. You have to go and see what works for you. Unconsciously you’ll start to build.”

She saw it in the twentysomethings who found confidence through movement. She saw it in the conservative mums who took up belly dancing at Move. “It was like a party, really,” Attar says of the scene. Students became “a tribe, a community. Their whole emotional wellbeing changed”. She remembers one teen who was so shy when she walked through Move’s door, she could barely speak. Through YouTube, the girl had learned some dance moves and convinced her sceptical mother to allow real lessons. At her first class, a one-on-one with teacher Noura Al-Abdulaziz, the girl was shaking. All she could do was nod and try to follow the steps.

Al-Abdulaziz understood. She had once suffered a paralysing depression, but “I started communicating with people through my body, through dancing, not saying one word”, she says. “That’s how I got healed.” Now, she watched her struggling student do the same: “She found her own style, her own personality.” Now a creative director, choreographer and dance teacher working all over the country, Al-Abdulaziz says, “Move started the idea that dance is something fundamental we need here in Saudi. I feel like I’m truly healing the Saudi people through dance.”

Only those who risk going far can find out how far they can go – this was something Attar’s father, Mohamed, said often. When she was younger, he took her on hikes, which wasn’t common in her region, but he loved exploring the outdoors. “We’d come across a beetle and he’d tell me about it,” she recalls. “He opened my eyes to nature.” When she was 17, he took her to Africa, where they climbed Mount Kenya. They didn’t summit, but a seed was planted. When climbing, Attar “just blossoms”, says her sister, Rasha Attar Elsolh. “She looks her best, feels her best, does her best. She’s meant to be on a mountain.”

Mohamed Attar wasn’t just her father, he was her best friend. They spoke by phone many times a day, and his words became a fuel for her climbing. She ticked off more peaks: Kilimanjaro, Elbrus, Aconcagua, Island Peak. Still, the first time someone suggested

“Movement is the best antidepressant or anti-anxiety pill ever”

Mount Everest, Attar thought it was absurd. How do you train in the desert for the world’s tallest mountain? Then she thought about her father encouraging her to push her limits, about how meeting challenges makes you stronger, and she took that imperfect step forward. Training for an arduous climb is never easy, but in Saudi Arabia there are additional challenges. Because there are no snow and ice-covered peaks, she ran intervals on sand dunes. To build strength, she dragged tyres through the streets. To dodge the desert heat, her workouts began at 3am. To avoid attracting attention from the moral police, she jogged in her black abaya. Finding the highest elevation gain in

Riyadh – about 150m – she trudged up and down for hours at a time. Attar’s training drew some stares. But it also had a hidden benefit: “People have said to me, ‘That’s how you’re so strong mentally.’”

In 2019, as her group – Attar, other Arab women climbers, plus trained guides and Sherpas – made their way from one high-altitude camp on Everest to the next, she’d listen to encouraging voice messages from her father. After spending two months on the mountain, they reached the summit.

Not long after, Attar suffered a series of personal losses. First, the pandemic hit Move and wound up crippling the business (though she has hopes to reopen one day). Then, in October 2020, Mohamed Attar died of COVID. In one fell swoop it felt like she had not only lost her father but also her way forward. “I felt my heart was open and it was leaking, like a fountain I couldn’t close,” Attar recalls. She couldn’t eat, couldn’t sleep. Seeing friends, dancing, training… it all felt impossible. And yet she knew what she had to do: move.

“Starting to teach dance changed my career, then my life”

In autumn 2021, Attar announced a plan to climb K2 the following summer. It was a dangerous goal: only around 400 people had summited it at that point, and statistics showed that one climber died for every four who stood on top. So she amped up her training, enlisting Mike McCastle, the US coach who trained explorer Colin O’Brady for his unsupported Antarctica trek. “He’s a brilliant coach,” she says, lauding the creative ways he pushed her limits, not only building strength but unearthing weaknesses.

By this time, Saudi Arabia was changing, too. The government was pushing a modernisation plan, Vision

2030. In 2016, it had established a women’s branch of its sports authority. The government also agreed to license female gyms – a reaction, in part, to alarming obesity statistics. In 2017, live music was no longer prohibited. In 2018, women were given the right to drive and to attend certain sporting events. In March 2022, Riyadh had its first official marathon, where men and women ran together. Many more women were going without the abayas that impeded physical activity. The government even began sanctioning concerts where men and women danced together. “I didn’t think all this could be happening so quickly,”

Attar says. “It’s just amazing, so surreal. The country changed, and we were part of that change.”

Attar was also becoming more widely known. Several publications wrote about her. Strangers recognised her at running events. She was tapped to be the first trainer in Saudi’s Nike Training Club. The Saudi Sports for All Federation appointed her as an official ambassador. The government had partnered with Move and Attar to provide a free boot-camp programme as a public-health measure, and also to teach dance to schoolkids. She had tens of thousands of followers on social media. And yet, when she sought

sponsors for her K2 climb, she couldn’t get traction. Though she’d spent almost all her life in Saudi, she was a Lebanese national, which made Saudi brands less receptive. It also became clear local companies still weren’t sure what to do with a female fitness icon. “I’ve had brands tell me they can’t work with me because I am Lebanese; because I dance too much; because I’m a woman, yet I don’t dress ‘feminine’ enough; because I have too many passion activities; because I can’t fit in a box,” she posted on Instagram.

Finding sponsors was exhausting. But then she recalled her father’s words on moving forward. She drained her bank account and made the plan anyway. Right before her departure for Pakistan, Bateel, a dried-fruit brand, agreed to support part of the cost of her trip. Incongruous, maybe, but her spirits were buoyed: “That’s why you should never give up.”

Not long after, she found another partial sponsor, digital media brand Yes Theory. As Attar began the seven-day trek from the village of Askole to the base of the mountain, she thought about the thousands of women and girls she’d supported through dance and fitness, and how they, in turn, were supporting her. She thought about her family back home, cheering her on. “I have a whole tribe of people climbing with me,” she realised. When the team spent two brutal weeks waiting out a storm at camp, Attar danced away the stress and boredom, infusing strangers’ tents with her energy even as she understood the tough journey ahead. Looking up at the endless snow and ice, she knew trusted guides would show the way. She also knew she’d have to take every step to the top herself.

Sometime after 10pm on July 21, they set off in pitch-black darkness. All the training had paid off: her legs and her lungs were up to the task. But, as her headlamp glared against a forbidding wall of ice, she faltered. Training in Saudi, there was no way to master ice climbing, yet here she was facing an ice wall on the world’s most dangerous mountain. Struggling for purchase with her crampons, she slipped again and again, at one point swinging perilously on her rope. Suddenly, for the first time in years, she was engulfed in throat-closing panic. Breathe, she told herself. Focus. Filter everything else out. “I’ve already been through grief, the worst thing in the world,” she realised.

Her heart slowing, she kicked her right crampon into the ice and made a move. She kicked in her left and made another. Around 3.30am, she cried as she reached the top. And when the team returned to camp, around 10 hours after starting, everyone danced.

“I’m Nelly Attar,” she likes to say, “and I move for a living.” nellyattar.com

“It’s amazing. Saudi Arabia changed, and we were part of that”

Words ALEX KING Photography CARLOS BLANCHARD

Words ALEX KING Photography CARLOS BLANCHARD

It’s the car racing series that’s hit the motorsport world like a bolt of lightning. And now, channelling pure electricity to save the future, the WORLD RALLYCROSS CHAMPIONSHIP is accelerating so fast it’s leaving Formula 1 in the dust

Inside the garage of the Hansen Motorsport team, AC/DC is blasting out of the speakers as mechanics speed through final tweaks to their cars. The Swedish team’s drivers, Timmy and Kevin Hansen, are amping up to head out onto the track; the latter is honing his reaction times by darting around and smashing at BlazePods – flash-reflex training devices – arrayed across a table.

With their matching clean-cut hairstyles and boyish faces, the two are clearly brothers, Kevin discernible by his glasses and a sheen of stubble. At 24, he’s six years Timmy’s junior and the more gregarious of the pair. Kevin currently sits in fourth place in the World Rallycross Championship, but he has

a palpable desire to match the success of his elder brother, the 2019 champion, who’s ranked number two this season. Timmy, meanwhile, is going through race data on a laptop with the team manager, who also happens to be his father, Kenneth Hansen, a former European Rallycross champion.

Rallycross, as the name suggests, has its roots in rallying. But back in the 1960s, before drone footage and dash cams became commonplace, the format – individual cars running against the clock over a lengthy point-to-point course across multiple days – was a hard sell to TV audiences. In 1967, Robert Reed, a producer of recently launched ITV programme World of Sport, had an idea: multiple cars duelling it out on a mixed-terrain circuit of asphalt and gravel. Easy to film and exciting to watch, with fast races over five laps, it was a concept tailor-made for TV. On the morning of Saturday, February 4, 1967, the first rallycross race was aired. Within a year, it was attracting almost 10 million viewers.

The sport also proved a hit with rally drivers across the world. In 1969, the first Dutch and Australian rallycross events were held, and a full European Championship was born in 1973. In 2010, the US debuted the RallyCar Rallycross Championship. Then, in 2014, the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA) – motorsport’s preeminent governing body – launched the World Rallycross Championship (World RX). But the sport’s dramatic evolution didn’t stop there. At the end of the 2021 season, it was revealed that the World RX Championship would go fully electric.

It’s November 2022 at the Nürburgring motorsport circuit in the German district of Ahrweiler. Spectators are packed around a small, closed section of the legendary track called the Müllenbachschleife, here to witness the final round of this first electric season.

“I was caught, in the middle of a railroad track. Thunder!

I looked round, and I knew there was no turning back. Thunder!”

Time for focus: Timmy Hansen prepares for the race start; (opposite) Johan Kristofferson and teammate Ole Christian Veiby battle it out

Time for focus: Timmy Hansen prepares for the race start; (opposite) Johan Kristofferson and teammate Ole Christian Veiby battle it out

Breaking up the asphalt straights are gravelled corners. Switching between the two surfaces adds drama to each lap, the asphalt sections boosting top speed while the loose gravel creates unpredictability and often chaos as the sliding cars throw up clouds of dust, wreaking havoc on the visibility of drivers in pursuit. Each race takes less than three minutes, with onboard cameras showing many drivers don’t even blink from start to finish.

Five cars are lined up on the grid, waiting for the green light. As they hurtle off the line, any doubt about their electric capabilities evaporates in a split second. The acceleration is blistering. These cars can hit 100kph in less than two seconds – faster than an F1 car – and the sound is unlike anything you’ve ever heard: an otherworldly chorus of high-pitched whooshing, almost hydraulic, like Optimus Prime flexing his robotic muscles.

Standing by the first corner, you’re treated to a multilayered sonic picnic in high definition: the rise and fall in pitch of four-wheel-drive electric powertrains decelerating and accelerating again; fibreglass bodies crunching against one another; tyres ripping up dirt as they jostle furiously to exit the bend, and finally the impact of all the gravel spraying into other cars and the safety barriers. The only sound missing is the roar of internal combustion engines. But without this layer to drown out everything else, your ears receive more information, not less. Speed, acceleration, visceral contact – all these aspects are amplified. It’s a complete sensory experience in every way.

Alittle later, outside the pits, another head-to-head competition between the drivers is underway. Volvo Construction Equipment, one of the race series sponsors, and supplier of the electric recovery vehicles that unceremoniously pull disabled cars off the track, has set up a battery-powered compact excavator with a metal rod hanging from its hydraulic arm. The challenge is to dip it, in sequence and against the clock, into five stacked piles of tyres. Johan Kristoffersson jumps into the cab. But, rushing through the last tyres, he causes the pole to swing wildly, preventing it from lowering easily into the holes.

“What’s my time?” he shouts. “That’s no good. Let me go again.” On his third