34 minute read

Javier Fernández Ortea, Gonzalo García Vegas y Covadonga Escandón Rubio

FROM SITE TO THE MUSEUM AND FROM THE MUSEUM TO SITE. PHOTOGRAMMETRIC MODELS DISPLAYED IN AUGMENTED REALITY AT THE SITE OF ERCÁVICA (CAÑAVERUELAS, CUENCA, SPAIN)

Del campo al museo y del museo al campo. Proyecto de visualización en realidad aumentada de modelos fotogramétricos en el yacimiento de Ercávica (Cañaveruelas, Cuenca)

Advertisement

Javier Fernández Ortea Monasterio de Monsalud y Ciudad Romana de Ercávica javierfernandezortea@gmail.com; Gonzalo García Vegas VIPAT - Arqueología y Virtualización del Patrimonio vipat.arq@gmail.com; Covadonga Escandón Rubio Allen Archaeology Ltd. c.escandon@allenarcheology.co.uk

Abstract: We are presenting the creation of a digital application based on the software Augment, for the display of photogrammetric models in augmented reality of key features in the archaeological site of Ercávica (Cañaveruelas, Cuenca). Following the selection of a group of findings deposited at the Museum of Cuenca, we are aiming to bring them back to their original context using virtual technologies, and thus providing some content for cultural structures that are currently empty. This contextualization of a group of statues and reliefs from Ercávica is expected to be a useful tool for visitors and some support for guides, helping with the display of finds found during the different archaeological campaigns. Furthermore, it is indeed a more interactive way to research our past, especially for young people. Resumen: Se presenta una experiencia de creación de una aplicación digital, basada en el software Augment, para la visualización de modelos fotogramétricos con Realidad Aumentada en puntos clave del yacimiento de Ercávica (Cañaveruelas, Cuenca). A partir de la selección de una serie de objetos conservados en el Museo de Cuenca, donde se depositaron tras las excavaciones, se pretende su vuelta al campo de procedencia, pudiendo visualizar en el yacimiento aquellos bienes en el lugar en el que fueron hallados, dotando de contenido a unas estructuras vacías en la actualidad. La contextualización de piezas de estatuaria y relieve de Ercávica pretende ser una herramienta útil para el visitante y un refuerzo para los guías como recurso que ilustre los objetos que fueron descubiertos en las sucesivas campañas de

excavación arqueológica. Además, es una vía más participativa de indagar en el pasado, especialmente atractiva para la gente joven. El uso de tecnologías de representación gráfica aplicadas a la arqueología y el patrimonio es un hecho bastante extendido a día de hoy y que, mediante este trabajo, pretende visibilizar su idoneidad tanto en la investigación y documentación de bienes arqueológicos como en su puesta en valor y difusión. Fotogrametría digital, modelado tridimensional y realidad aumentada han sido las técnicas y herramientas utilizadas para este proyecto, experimental e innovador, cuya continuidad, reforma y adaptación ésta relacionada con los resultados del mismo, tanto a nivel técnico, como de valoración del visitante. Keywords: Virtual Archaeology; Digital Archaeology; Cultural Heritage; 3D Reconstruction; Augmented Reality. Palabras Clave: Arqueología virtual, arqueología digital, patrimonio histórico, reconstrucción 3d, realidad aumentada. 1. Origins of the project. inexpungable stronghold, due to its Management of the site of Ercavica. antieconomic, difficult to sell and

In January 2014 a team of centre of acute social sensitivities archaeologists won by public tender (Lopez and Tudanca 2006:25). In the management of the visits to the spite of that, the management of such Roman-Visigoth city of Ercávica heritage space was assumed as a (Cañaveruelas, Cuenca) and the professional and personal Cistercian monastery of Monsalud opportunity on which the effort and (Córcoles, Guadalajara). The implication of the guides has pursued goal of Dirección General de positively affected the number of Patrimonio of the regional visitors, visibility in the media and government of Castilla-La Mancha performed activities. was the reopening of these spaces by The natural ability of the means of a public-private co- mission required a strong role as operation that allowed its economic cultural manager in the figure of an viability. The new vision of the archaeologist, who could join the management involved the challenge conservation and scientific accuracy of making profitable two with the planning, execution and unprofitable spaces in a short period evaluation of effective strategies for of time, 4 years, circumstance that the diffusion of heritage. In this way, dragged out the possibility of professionals of the Culture investment due to the short time for immersed in a continuous process of the write off. To theese the chronic innovation act as producers, problems which constrain the designers, sellers, promoters all at heritage must be added which makes the same time (Rowan 2010:41). In some authors consider heritage as an order to contribute to a premeditated

action plan a complete management project was carried out so as to contextualize and undertake the guidelines of action (Fernández 2017). According to Querol (2010) the following phases in the management of heritage must occur: knowing, planning, control and diffusion. Once the team was documented on bibliography, cartography and the diplomatics available for the two spaces, a solid speech was made to be spread presentially or virtually. Later a communication plan was outlined at touristic and institutional level which gave consistency and image to the two centres as well as allowing the interaction with the web user. For the first time an on-line reservation booking form was available which facilitated the internal organization of the team and the touristic visitors forecast. In the same way a social networks portal was open to spread the programmed activities and get the interest from users without neglecting the holders and publications of traditional leaflets in the region.

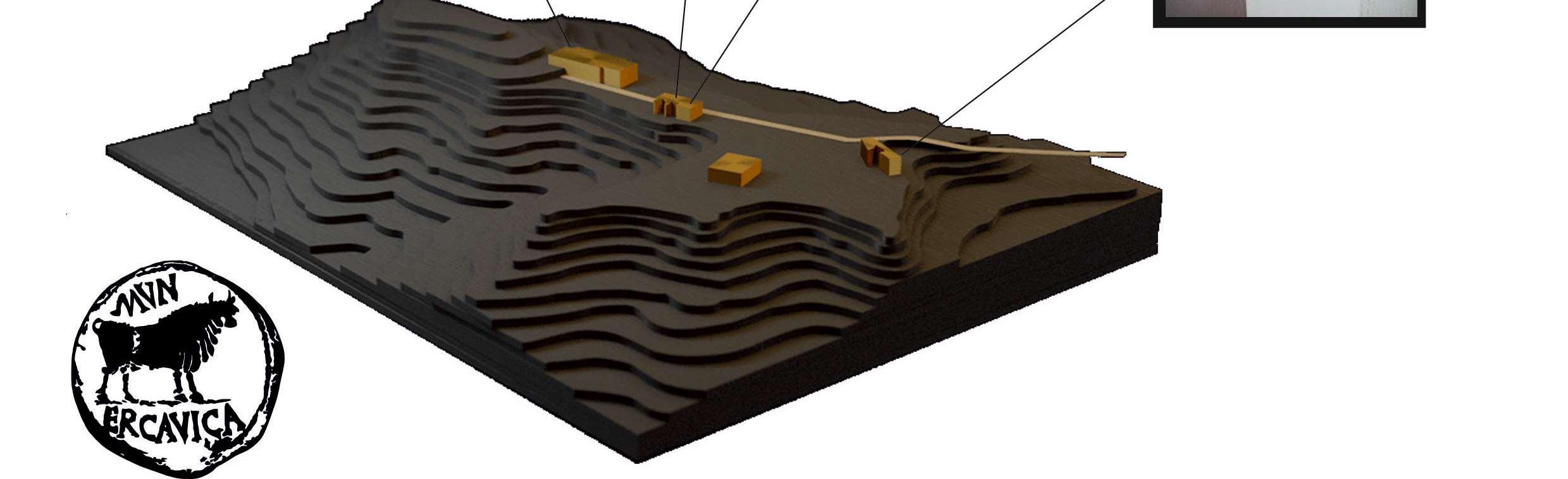

In this article, we will refer to a particular action in Ercávica. The site of Ercávica (figure 1) lies in the castrum of Santaver, municipal district of Cañaveruelas (Cuenca) over the cliff of river Guadiela, it has an extension of approx. 14 hectares. We have the testimony of Titus Livius in regard to the military campaigns of L. Postumius and T. Sempronius Gracchus around 179 before Christ who defined it as nobilis et potens civitas (Livius XL 50). It played a remarkable role in the romanization of the inner Peninsula and obtained the legal promotion of Municipium under the Principality of Augustus (Rubio 2013). In the middle of the 3rd century its decline was confirmed and the population moved to the surrounding valleys (Barroso and Morin 1993-94). In spite of that it reached the episcopal status under the name of Arcávica attending several synods in the Visigoth era.

Figure 1. View of Ercávica.

Regarding the touristic dynamization of Ercávica, several pondered initiatives were taken so as to obtain a high sustainable efficiency with the acute lack of infrastructures. The lack of a covered space except for the welcome visitor centreand the recent volumetric reconstruction of Domus 4 (2015) limited the potential activities a great deal. The scarce grade of musealisation and information panels of the site were a first problem for the legibility of it. To overcome this drawback a system of MP3 selfguides was created that made the understanding of the ruins possible, this helped with the logistics of the guided visits with the limited personnel available. With a small investment, a service required by isolated visitors and couples was fulfilled, this made possible the feasibility of the model without personnel cost. Connected with the diffusion activities we can mention workshops for children, night visits, tastings of Roman wine or the yearly celebration of the Roman days.

2. Identification of difficulties in the interpretation of the archaeological sites.

As Mansilla says the great forgotten in the promotion of archaeological heritage is paradoxically its receiver, the public (Mansilla 2002). Even today there is a lack of studies regarding visitors and archaeological sites except for monographic studies on local heritage value (López and Navarro 2007; Chavez et al. 2009-2010 and Moreno, 2013). They deal with diffusion or management with some general works (Ballart and Tresserras 2001; Querol 2010, Ponce and Rubio 2013). At a national level it is worth mentioning the qualitative study of Morère and Jiménez, with limited results due to the shortage of institutional response (2006). Personally, we are waiting for the publication of our own quantitative study on the figures of visitors to archaeological sites all over the country as we understand it becomes a must to start knowing the real market and verify that it is a development engine as it has been referred to so many times. One of the major problems that the visitor of archaeological sites faces is the legibility of the ruins interpretation. In such a way it has been commented to us along the years we have been doing our job in Ercávica, this makes the guided tour with a specialist a must. The true statement came from the users, there is a big difference between seeing a nice place and seeing a nice place and understanding it at the same time .It is true that the visual support and signing are essential resources but the archaeological heritage by definition has scarce legibility for the average visitor (García and de la Calle 2010), making this way insufficient to transmit messages of profound importance. In the case of Ercávica the signing is not enough to distinguish a complete itinerary of the city, with remarkable vacuums in

the thermae, southgate, house of the Doctor and Forum. Despite that, it was recently installed an allusive monolith to the Route of Crystal in Hispania at the bottom of Santiver Castrum and an explicative sign of the fountain of Pocillo water supply that existed during the Visigoth era and till the mid-20th century (García de Domingo et alii 2015: 65). Moreover, more signs have been added in the road linking Cañaveruelas with Ercávica in order to guide the visitors to the site. Even though those elements are necessary they don’t solve the main problem, the unbridgeable distance between some structures empty of content and the visitor.

The evident reality between the public and the site is the succession of wall structures orphans of content. The archaeological excavations intend to document scrupulously every remaining that allows contextualize the structure and permit a factual interpretation. Once the pieces have been classified and catalogued, they are deposited in museums where they are kept. This way we get to a contradiction in the diffusion of archaeological heritage, the places that have been custodians of these funds lose them, become empty, and the museums receive some goods with the difficulty of divulgate them without deeply knowing its context (Querol and Martínez 1996). Certainly, the conservation and research of the rescued remains must be the maximum priority. In this situation we can wonder how we could bring back the materials that give content and sense to the structures without compromising its security and maintenance.

3. Project of virtualization of photogrammetric models on site with Augmented Reality.

The didactic possibilities that digital photogrammetry offers are unlimited “archaeological studies and analyses of architectural structures, digital documentation, preservation and conservation, 3D repositories and catalogues, virtual reconstruction, computer-aided restoration, virtual anastylosis, physical replicas, virtual and augmented reality applications, monoscopic or stereoscopic renderings, multimedia museum exhibitions and virtual visits, archaeological prospection, web access, visualizations and so on” (Fernández-Palacios et alii 2013). We know some examples of its combined use with Augmented Reality at international level as the Augment models of the Lincoln Home National Historic Site. However, in Augmented Reality predominate the models of architectonic virtual reconstruction as you can see in the project Archeoguide en Olimpia (Vlahakis et alii 2002), Pompei or Rome (Canciano et alii 2016). In our country the case of Ampurias can be mentioned or the application development for the Roman thermae of Albir (Alicante). At a didactical level the pioneer Techcooltour

Augmented Reality Mobile Application, means a further step by activating thru markers, presentations and virtual guides in twelve archaeological sites of the Roman and Byzantine times in four different countries.

To enhance the legibility of Ercávica site, giving content to the various urbanistic areas, we intended to document and virtually represent the main pieces of the site, today kept at the Cuenca museum, in the place they were found. According to Caballero (2011), both museums and sites must be active centers of experimentation in which the participation of the public takes a special relevance, so wanted to know their impressions about this initiative. The accessibility and economics of the digital photogrammetry allowed the possibility to bring back the objects to their origin without risk or cost. This technique permits guessing the grounds and elevation of an element based on photographs, which can make a topographic drawing of it (Santamaria and Sanz 2011). The basic idea did not have antecedents in our country where the use of photogrammetry and 3-D have been applied to the reconstruction of buildings and places belonging to historical heritage (Pérez et alii 2011; Angulo 2013; Ortiz 2012), exhibitions (Jiménez et alii 2013; Escaplés et alii 2013), archaeological documentation (Ortíz 2013; Ramírez-Sánchez et alii 2014; Miñano et alii 2012) and other uses but not in materials out from, its place and in the open countryside.

The used tools have offered to us a wide range of possibilities and benefits: first, a reinforcement to the local identity and its self-stem as there is a feeling of uprooting when the pieces found in Ercávica were sent to Cuenca. This is a common effect in all rural areas which have had archaeological excavations and where the virtual return of the main findings can be an important moral restitution. The neighbors of these villages don’t know the recovered objects as they have not been informed about the findings, so they don’t know its subsequent destination. The virtual initiative implies an interesting spur in terms of visibility and promotion as the media are hungry for publishing news on cultural activities, especially if they are combined with new technologies. In this case, the incorporation of this kind of technologies replaces a costly advertising campaign as well as impacts positively on the image and services of the center. Security is other of the big benefits. Firstly, Digital Photogrammetry implies a back-up copy of the museum funds and it is an accessibility tool for the researches that avoids manipulating the originals with the implied danger. We can also enjoy the best pieces in the open countryside without being afraid of its conservation or vandalism. Research also benefits from photogrammetry by spurring curiosity and getting

access to the first-hand materials especially if these are in online drivers. This way the comparative analysis and analogies with other sites is also simpler. From the economical point of view, it is evident the profitability of this resource that can substitute or at least complement the so-called interpretation centers, spaces normally closed due to the lack of maintenance and personnel, lacking scarce planning (Martín 2011:407). What is more they can sometimes substitute costly physical and virtual reconstructions as the materials can be illustrative enough to substitute any addition. Finally, the didactic attraction of a virtual resource is an argument for its implementation by drawing the attention of the visitor especially the youngest. In this sense it has a double interest by drawing the attention of the groups lees used to the current museological language, nobody can deny the importance of game in the learning process for children and adults alike.

Following Santacana and Serrat (2007:84) the function of the objects in the didactic field is vital as referent and support of memory, enhancing the empathy with the visitor and contributing so as he creates his own hypothesis. Photogrammetry together with Augmented Reality fulfil the need of creating dialogue in the archaeological sites.

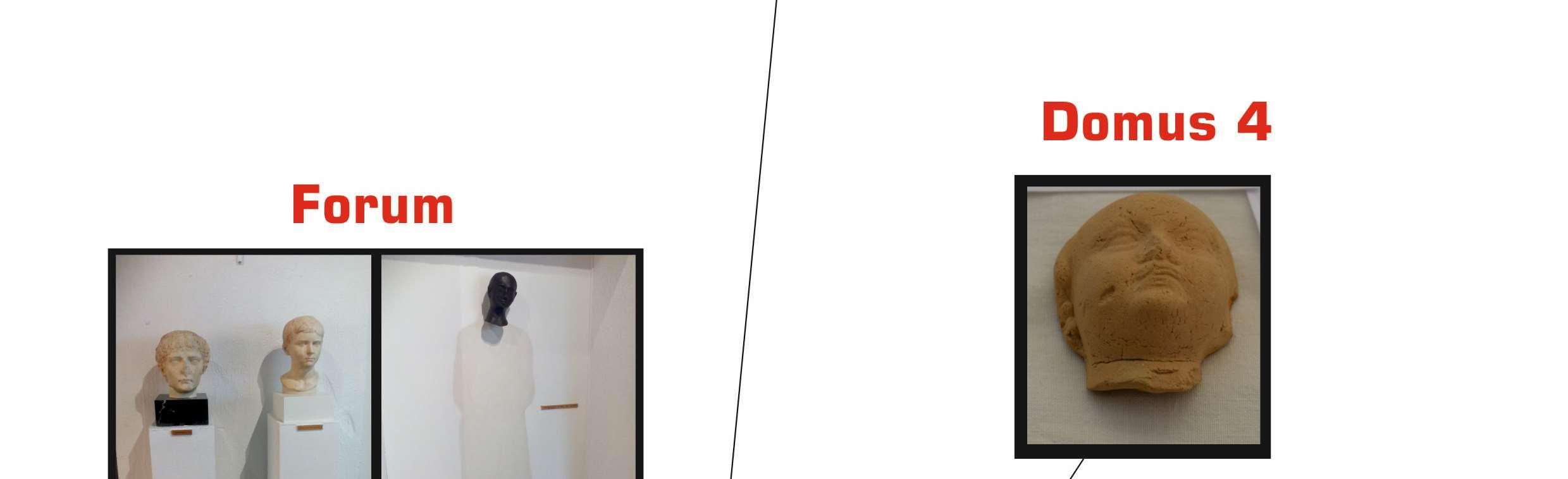

The management team of Ercávica visited the facilities of Cuenca museum in February 2017 in order to know the funds coming from the Roman city, especially those that comprise the permanent exhibition after the compulsory authorizations of the Sub direction of Culture in order to undertake the photogrammetric task. After getting to know all the deposited pieces it was decided to make a selection of statuary and embossment due to reasons of coherence and technical feasibility. In regard to the first one, sculpture is a significative referent of the Roman culture and particularly of Ercávica having examples of various supports, techniques and periods of time at the museum. The selected items have different supports (bronze, ceramic and stone) and correspond to constructive, ludic, political and religious functions, most of them coming from the Forum area of the 1973 campaign by Manuel Osuna (Osuna 1976). They are a bust made of bronze attributed to a senator (AA77/19/379), a plaque also made in bronze as a part of a ceremonial ara (AA77/19/369/375), the marble busts of Lucius Caesar (AA77/19/438) and Agrippina, a stone later Roman capital and the face of a possible puppet in ceramic. The designed tour of markers (figure 2) start with the later Roman capital introducing the visitor at the end of the Roman world and in the disappearance of the Visigoth kingdom, the necropolis-hermit cave of Ercávica and the Servitan monastery (Barroso and Morín 1996; Barroso et alii 2014), all of it on the base of the site.

Figure 2. Itinerary of the virtual models in Ercávica. Drawing from www.canaveruelas.org.

After that it is the access to Domus 4 with its volumetric reconstruction which submerse the public into the domestic world, this is the reason why we have chosen the virtual model of a ceramic puppet whose original context is unknown. Half way from Cardus Maximum and before the doctor’s house, another marker permits the visualization of a religious ceremonial plaque, which helps to understand better the cult of the ancient times with the shown elements: aspergilum, ápex flaminis, simpulum, patera, oinochoe y bucranium (Osuna 1976:101). The plaque appeared in the forum but due to logistic reasons of the tour we preferred to display it in this point, helping the explanation of the guide in his introduction to the world of religion and medicine so much connected in ancient times. To finish

the forum hosts the busts of Lucius Caesar, Agrippina Minor and the head of a possible senator. The two variations of portraits, official and local, help illustrate the preeminence of the imperial cult on one side and the socio-political structure of a municipum on the other side. In the same way it makes possible the explanation of the stylistic aspects in the evolution of portraits and the meaning of the Roman lus imaginum. We would have liked to include black and white photographs of the findings of these sculptures on site published by Osuna (1976) but we dismissed the idea so as to avoid liabilities with image property rights. In future it would be a desirable tool to have these pictures as they faithfully reflect the place of origin and the circumstances of the discovery.

4. Methodology and execution of the project

The execution of the Project is based in the comprehensive utilization of different techniques which improve quality wise the final result. Moreover its use as a noninvasive technique (so important in the maintenance and conservation of heritage) as well as its visual attractiveness and virtual interactions, make photogrammetry, three-dimensional modelling and augmented reality, an interesting option to go on experimenting in order to bring closer the past to our present, arising the social interest for historic legacy. The process carried out to execute the project is based on the use of digital photogrammetry as a tool of three-dimensional documentation and augmented reality as a technique to digitally represent the selected archaeological items. In the same way, it was necessary three-dimensional modelling in some parts of certain pieces, due to some technical difficulties that we encountered and about which we will deal later.

4.1 Digital photogrammetry

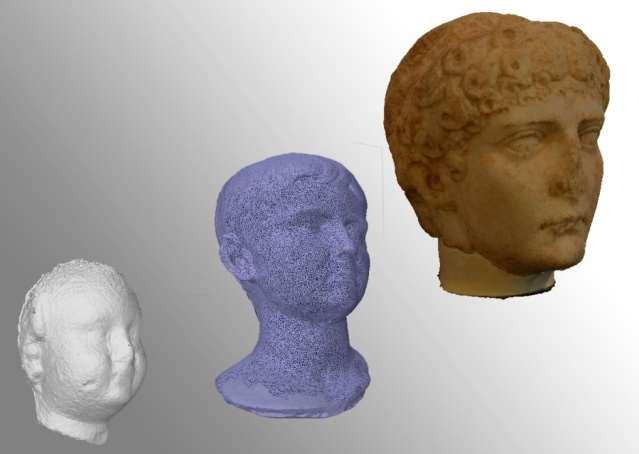

Digital terrestrial photogrammetry is a great potential tool in the service of archaeology and heritage, becoming today a big part of the resources allocated not only to the divulgation and diffusion of the remains, but also in the research and documentation of historical goods. With its use, we can succeed in making three-dimensional models (figure 3) based on images coming from digital photos. In the same way, it is very useful in the creation of orthophotos due to restitution of the conic projection, which deforms the images from photographic lenses, by the orthogonal, which keeps the metrical properties of the studied object.

Figure 3. Three-dimensional drawings of the Project represented in different steps, documented by means of digital photogrammetry.

In this case we went to the museum facilities with the photographic equipment in those days limited to the public and this way the proposed works were carried out. Once the pieces have been previously selected by its historic-archaeological interest as well as its physical characteristics a photographic register is made taking into account several factors: -Purpose; the type of work that is presented, conditions the parameters and values to be followed in the process. In this case and considering its diffusion by devices that allow the use of Augmented Reality (mostly user mobiles and tablets) it is necessary to make a balance between functionality and representation that is to say a light model that assures the interaction on real time without losing details and important characteristics. -Morphology of the pieces; Making a planning of the capture according to the geometry of the piece. -Placement: Depending on the lighting of the room or the place where they are located, it may be necessary, if is possible, to move them to other places with better conditions for the capture of images. In cases where its movement is not possible it will be used -always with the pertinent authorizations of the museum- a box of light or soft light box, with white lights and a tripod with rotating base, this will allow us to have a better control of lightning, one of the key elements for the correct three-dimensional documentation.

-Physical properties of the piece (composition); depending on the base material of the piece, it can produce reflections which can make difficult the subsequent photogrammetric processing. Once having in mind these agents, the adequate photographic parameters must be followed to have all pixels of the object represented in the 3-D model (sharpness, overlapping of images, etc). After introducing the images in a photogrammetric software, with a previous analysis and correction of the necessary parameters on each photograph, the following task is carried out: creation of clouds of points and mesh, as well as final texturing of the piece, manually adjusting the values on each phase and executing the processes by algorithms. Those pieces, virtually documented, are taken to another three-dimensional modelling software, -Blender in this case, - (figure 4) so as to be retouched and optimized (by means digital sculpturing and retopology -among others -) in order to visualize them on real time with Augmented Reality.

Figure 4. Optimized process with Blender of a capital documented with digital photogrammetry.

In this phase, according to what we previously mentioned, we have some issues that made us modify the working process; -The busts of Lucius Caesar and Agrippina (figure 5) are in the same room, very close together and with the back part of the head next to the wall. The impossibility of moving those pieces to a much more convenient place for its photogrammetric register makes it difficult to capture images at their full plenitude, dead angles can be seen with no chance to be documented in good conditions. The mentioned difficulty was overcome by drawing, description, and photography, - without taking into consideration the parameters of photogrammetry- of these areas and its later three-dimensional modelling by making a new geometrical mesh (following the volume of hair and the very cranial structure of each individual), and the texturization of such surface with similar colours to the marble material of these busts.

Figure 5. Busts of Lucius Caesar (Forefront) and Agrippina (secondary plane), their placement (and impossibility of moving them away) makes difficult the photogrammetric register.

-In the case of the bronze religious plaque that was only decorated on one of the sides it was not made the three-dimensional documentation due to the limited thickness and lack of decorative motifs in the rest of the surface. Due to that the piece was photographed and a 2-D image was obtained to be represented later on. -The bust named “senator” (figure 6), made in bronze, produces reflection (specular reflection) so it is necessary to find a device that controls the lightning and hence improves the graphic register.

Figure 6. Specular reflection of the Roman bust due to fact of being made in Bronze.

4.2 Augmented Reality

With this technology it is possible to obtain an improved perception of the real world with a combination of information generated by a computer (Ruiz Torres 2013). In this case, it was not chosen to make a new application from zero even though it was run thru different softwares like Unity® o Vuforia®. But due to the experimental character and the lack of economic resources, Augment®, a AR software of closed code was used. Its use was decided due to the following factors: -Free of charge. In spite that it is a platform of payment -except for those users with educative licences-, it was given free-of-charge, at least during one year with the possibility of extension under some requirements. In the same way it was necessary that it was a free application for the public, as it is not

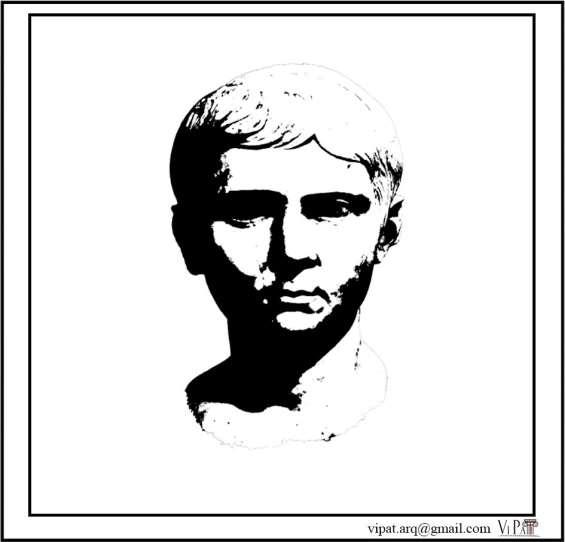

pursued an economical interest but offering the visitor a didactic resource to improve his experience and allows the joy and learning in a dynamics and attractive way. -Own characteristics of the software. the resources the programme offers makes it possible to use in our work according to our needs; -Work properties: Detection by markers -the projects of identification by GPS produce sometimes errors of geolocalization and thus make the Reading and realism of the application difficult -, visualization of different models in the same process, possibility of navigation in a 360º without the need of being connected to internet. -Personalization of the project: Characterization with own design (figure 7), inclusion of logos or modifications of basic functions, as the initial position of the model.

Figure 7. Personalized marker of the bust of Lucius Caesar.

-Functionality; Stability of the program, quick reaction of the software to the movement of the marker, low size application and friendly use. -Feedback: It allows the capture of images to be shared in the social networks (figure 8).

Figure 8. Image on the site where the model is, obtained by means of Augment and shared in the social networks with a mobile.

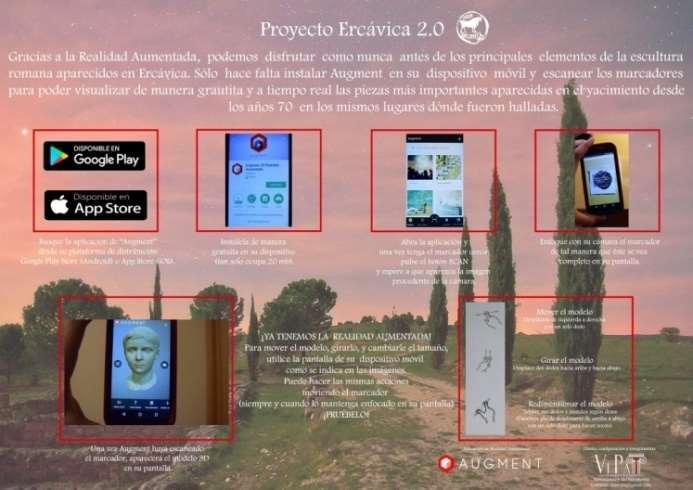

In the end, the idea is to have an application adapted to all publics and with different possibilities according to the interests and needs of the user, for those who want to enjoy the experience, they can download the application in the site and submerse themselves in the virtual world. If it is not possible the download or if it is difficult to understand they can interact with the pieces of equipment pf the guides in Ercávica.

5. Mise-en-scene

Once executed the process of photogrammetric documentation with its pertinent optimization- and obtained the license of the augmented reality software the following steps were taken for the finalization of the project: -Installation of the markers in key points of the visit which allow a logical and armonic speech with the proposed itinerary, taking into consideration the different thematic and functional areas of the site. -Test of the Works. Different tests have been made to determine the degree of stability and reaction of Augment before the threedimensional models. In the same way its functionability and capability in different stages have been checked modifying characteristics or parameters according to its appropriateness. -Creation of signage for easy handling and interpretation (figure 9). At the entrance of the site an informative panel was placed that tried to explain the utility and functioning of this representation mean used in Ercávica.

Figure 9. Panel displayed at the entry of the site. -Integration of the application in the proposed interpretation guide, both in the oral content, and in its visualization (thru a Tablet device that the personnel have for their explanation). The mentioned process enriches and dynamize the visit with new interactive content making more attractive interaction and learning.

-Diffusion of the content, press releases, social networks, publications, interviews with different mass media. Finally, a survey was conducted to analyse the impact of the project in the visitors so as to know better both the advantages and the defects of the application, as well as the interest of public in it, we could get some data that is mentioned below.

6. Results

With the intention of knowing the impressions of the public on the implementation of the Ercávica application a small statistic (figure 10) was produced to collect data about age, origin, rating and opinions, trying to get a representative quantitative and qualitative. Thirty-six surveys were conducted between May and August 2017 in regard to visitors randomly chosen. In this sense it spotlights the non-heterogenous origin of the tourists 50% coming from Madrid, after region of Valencia a (27,7%), Cuenca (16,7%) and Guadalajara (5,6%). Later it is remarked the response favourable to its use (75%), all groups approved its utility regardless the age, this can put in doubt some prejudices in respect to the use of new technologies in aged people. It is true that in the survey neither minors not elderly people over 65 are included as they had not used the application when they were questioned. However, it is true that the useful range of the application is very wide in any case.

1 4 1 2 1 0 8 6 4 2 0

Age Is i t u se fu l? P o s it ive an sw ers V alu at io n 1 8 - 29 y ears

3 0 - 39 y ears

4 0 - 49 y ears

Figure 10. Statistics on users’ opinions according to age.

In respect to the poured opinions, they are very different, but it is remarkable the enthusiasm of the young users of smartphones and the frustration of some visitors due to the reflection of their screens at certain hours, with the subsequent difficulty of running the software. On other hand it denotes that on some occasions the application becomes frozen, maybe due to the limited experience on the use if the markers. The major assessment corresponds with the age category between 18 and 29 years (7,7), followed by the category between 40 and 49 years (6,8).

7. Conclusions

The experience of proposing new languages in the museological speech is always rewarding. First because it puts us in the point of view of the visitor, finding the way of drawing his attention and sending him an efficient message. This assumption, even though it can be evident, paradoxically is not

common in the presentation of the archaeological heritage .In this area ,not only the bequeathed remains must be researched but also the way of presenting them, taking into consideration the type of visitors, their interest and expectations. In this way, we cannot neglect the key role of the new technologies, not only for the economics but also for the undoubtful practicality and appeal for the consumer of cultural products. The proposed initiative that can be improved on the basis, for instance with the inclusion of audio and video, with the register of other key and representative pieces, a deeper study of the evaluation of the application by the visitor or with the creation of an own and independent, means a first step towards the achievement of a museography beyond the unilateral message by giving an active role to the visitor. In the same way, the fact that it is a visualization in the open air it can be conditioned by climatology. The obtained results reflect a positive attitude of the visitor, who can understand the content of the orphan structures that give support to the guide, enabling him to endorse the explanations in his own hands thanks to Augmented Reality. For all that we advocate for the use of this kind of applications, finding ways of solving its drawbacks, as a resource to give value to ruins and filling them with the content kept at the museums. Finally we want to acknowledge the kindness of all the personnel of the Cuenca museum for making our job easy at every moment and for having a great availability, special thanks to the director, Magdalena Barril.

Bibliography

Alonso, N. Balaguer, A., Bori, S.,

Ferré, G., Junyent, E., Lafuente, A.,

López, J.B., Lorés, J., Muñoz, D.,

Sendín, M.& Tartera, E. 2001

“Análisis de escenarios de futuro en realidad aumentada. Aplicación al yacimiento arqueológico de ElsVilars.

Actas del 2º congreso internacional de interacción persona- ordenador (interacción’ 2001), pp.357-368. Angulo Fornos, R. 2013. “La fotogrametría digital: una herramienta para la recuperación de arquitecturas perdidas. Torre del

Homenaje del Castillo de

Constantina.” Virtual Archaelogy

Review, 4 (8): 140-144. https://doi.org/10.4995/var.2013.4355 Ballart, J. y Tresserras, J. 2001. Gestión del patrimonio cultural. Colección Ariel

Patrimonio. Barcelona. Barroso Cabrera, R. y Morín de

Pablos, J. 1993-94. “Las termas de

Ercávica: Un posible edificio de baños rituales en época romana”. AnMurcia, (9-10): 237-267. http://revistas.um.es/apa/article/view /64241/61911 Barroso Cabrera, R. y Morín de

Pablos, J. 1996. “La ciudad de

Arcávica y la fundación del monasterio Servitano”. Hispania

Sacra, 48:149-196. https://www.academia.edu/8978473/

Las_ciudades_de_Arcavica_y_Recop

olis_y_la_fundaci%C3%B3n_del_mo nasterio_Servitano._Organizaci%C3 %B3n_territorial_de_un_asentamient o_mon%C3%A1stico_en_la_Espa%C 3%B1a_visigoda Barroso Cabrera, R., Carrobles

Santos, J., Diarte Blasco, P. y Morín de

Pablos, J. 2014. “La evolución del suburbio y territorio ercavicense desde la tardía antigüedad a la época hispanovisigoda”. J. López Quiroga y

A.M. Martínez Tejera (coords.) In concavis petrarum habitaverunt:el fenómeno rupestre en el Mediterráneo

Medieval : de la investigación a la puesta en valor, 257-294. https://www.academia.edu/8975694/

LA_EVOLUCI%C3%93N_DEL_SUB

URBIO_Y_TERRITORIO_ERCAVIC

ENSE_DESDE_LA_TARD%C3%8DA _ANTIG%C3%9CEDAD_A_LA_%C 3%89POCA_HISPANOVISIGODA_E l_monasterio_Servitano_y_Rec%C3%

B3polis Caballero, F.J. 2011. “Nuevos métodos de difusión del arte.

Espacios expositivos virtuales: proyecto UMUSEO”. Actas de El

Patrimonio Cultural y Natural como motor de desarrollo: Investigación e

Innovación. A. Peinado Herreros (coord.), págs. 2487-2501 https://doi.org/10.4995/var.2012.4402 Canciani, M., Conigliaro, E., Del

Grasso, M., Papalini, P., Saccone, M. 2016 “3d survey and augment reality for cultural heritage. The case study of aurelian wall at CastraPraetoria in

Rome”. International Archives of the

Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing &

Spatial Information Sciences. Vol. 41.

XXIII ISPRS Congress, 12–19 July

2016, Prague, Czech Republic. 931937. http://hdl.handle.net/11590/306694 Caro Martínez, M., Hernando-

Hernández, D., & Jiménez-Díaz, G. 2015. “RACMA o cómo Dar Vida a un

Mapa Mudo en el Museo de

América”. CoSECivi 2015: 80-89. http://ceur-ws.org/Vol1394/paper_8.pdf Chávez, M.E, Pérez, F, Pérez, M.E,

Soler, J, Goño, A y Tejera, A. 20092010. “El proyecto de San Blas (San

Miguel de Abona, Tenerife):

Revalorización del Patrimonio

Arqueológico”. Tabona, 18. 121-133. https://riull.ull.es/xmlui/handle/915/4 814 Delafuente, J., Castaño, E.& Labrador,

F.2017. “Augmented reality in architecture: rebuilding archeological heritage”. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences,

Volume XLII-2/W3, 2017 3D Virtual

Reconstruction and Visualization of

Complex Architectures, 1–3 March 2017,

Nafplio, Greece.doi:10.5194/isprsarchives-XLII-2-W3-311-2017 Doncel, R. 2015. Aplicación de Realidad

Aumentada en dispositivos móviles para la recreación de restos arqueológicos.

Proyecto Fin de Carrera / Trabajo Fin de Grado, E.T.S.I. en Topografía,

Geodesia y Cartografía (UPM).

Universidad Politécnica de Madrid.

Madrid. http://oa.upm.es/34839/1/PFC_ROBE

RTO_DONCEL_MU%C3%91OZ.pdf

El Museo Arqueológico de Burriana estrena un visor de realidad aumentada (2015, March 23). El periodic. Retrieved from http://www.elperiodic.com/burriana/ noticias/363573_museoarqueol%C3%B3gico-burrianaestrena-visor-realidadaumentada.html El Museo Villa Romana de l'Albir estrena una aplicación de realidad aumentada para visitar las termas en 3D. (2014, December 02). Europapress.

Retrieved from http://www.europapress.es/comunit at-valenciana/noticia-cultura-museovilla-romana-lalbir-estrenaaplicacion-realidad-aumentadavisitar-termas-3d20141202141813.html Escaplés, J. Tejerina, D. Bolufer, J. y

Esquembre M.A. 2013. “Sistema de

Realidad Aumentada para la musealización de yacimientos arqueológicos”. Virtual Archaelogy

Review, 4(9), 42-47. http://hdl.handle.net/10045/48194 Fernández Ortea, J. 2017. “Gestión privada del patrimonio cultural: los casos del monasterio de Monsalud y la ciudad romana de Ercavica”. Pasos,

Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio, 15, (1):121-137. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?i d=88149387008 Garagnani, S., Manferdini, A.M. 2011.

“Virtual and augmented reality for

Cultural Heritage. In: SIGraDi

Cultura aumentada”. XV Congreso de la Sociedad Iberoamericana de

Gráfica Digital, Santa Fe, 555–559 (2011).

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/110 70167.pdf García de Domingo, A, Castro Quiles,

A. y Martínez Navarrete. C. 2015.

Condicionantes hidrológicos de un abastecimiento histórico con aguas subterráneas a la ciudad romana de

Ercávica (Cañaveruelas, Cuenca). Carlos

Martínez Navarrete y Miguel Mejías

Moreno (Eds).Instituto Geológico y

Minero de España. Ministerio de

Economía y Competitividad, Madrid. García Hernández, M. y De la Calle

Vaquero, M. 2010. “Uso y lectura turística de los grandes conjuntos arqueológicos.Reflexiones a partir del

Estudio de Público de

MedinaAzahara / Madinat al-Zahra (Córdoba)”. Pasos, 8 (4). 609-626. https://www.researchgate.net/public ation/268146918_Uso_y_lectura_turis tica_de_los_grandes_conjuntos_arqu eologicos_Reflexiones_a_partir_del_

Estudio_de_Publico_de_Medina_Az ahara_Madinat_al-Zahra_Cordoba i2CAT impulsa la creación de modelos 3D de los yacimientos de

Empúries. (2014, May 02). Retrieved from http://www.i2cat.net/es/blog/i2catimpulsa-la-creaci%C3%B3n-demodelos-3d-de-los-yacimientos-deemp%C3%BAries

Illescas, S. 2017, (January 6). Expertos utilizarán la realidad aumentada para conocer al detalle las etapas de La

Alcudia. Información. Retrieved from http://www.diarioinformacion.com/e lche/2017/01/06/expertos-utilizaranrealidad-aumentadaconocer/1846179.html?platform=hoot suite Jiménez Fernández-Palacios, B.,

Rizzi.A y Remondino, F. 2013.

Etruscans in 3D - Surveying and 3D modeling for a better access and understanding of heritage. Virtual

ArchaelogyReview, 4, (8) : 85-89. https://doi.org/10.4995/var.2013.4324 La villa romana de Toralla, en Vigo, estrena una app móvil (2017, August 10). Faro de Vigo. Retrieved from http://www.farodevigo.es/granvigo/2017/08/10/villa-romana-torallavigo-estrena/1731257.html López, J.A. 2014. (March 30). Gadir se hace presente. Diario de Cadiz.

Retrieved from http://www.diariodecadiz.es/ocio/Ga dir-hace-presente_0_793420893.html López de Cámara, C y Tudanca

Casero, J.M. 2006. “El patrimonio cultural estratigrafía razonada de un concepto”. Berceo, 151: 11-29. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/arti culo?codigo=2667947 López, I. y Navarro, E. 2007. “El patrimonio arqueológico como dinamizador del turismo cultural: actuaciones en la ciudad de Málaga”.

Baetica. Estudios de Arte, 29: 155-171.

Facultad de Filosofía y Letras.

Universidad de Málaga. http://dx.doi.org/10.24310/BAETICA. 2007.v0i29 Mansilla, A. 2004. La divulgación del patrimonio arqueológico en Castilla y

León: un análisis de los discursos (Doctoral dissertation, Tesis Doctoral,

Universidad Complutense de

Madrid, Madrid. http://eprints. ucm. es/tesis/ghi/ucm-t27682. pdf (Acceso 10/09/2011). Martín Piñol, C. 2011. Estudio analítico descriptivo de los Centros de

Interpretación patrimonial en España.

Tesis doctoral. Joan santana (Dir).

Universidad de Barcelona. http://hdl.handle.net/2445/41466 Miñano Domínguez, A.I, Fernández

Matallana, F. y Casabán Banaclocha

J.L. 2012. “Métodos de documentación arqueológica aplicados en arqueología subacuática: el modelo fotogramétrico y el fotomosaico del pecio fenicio

Mazarrón-2. Puerto de Mazarrón,

Murcia”. Saguntum, 44. 99-109.DOI: 10.7203/SAGVNTVM.44.1683 Moreno, A. 2013. “La planificación y gestión turística de SiemRiep /

Angkor (Camboya): Una aproximación desde el destino arqueológico considerando su relación con el parque arqueológico”.

Pasos, Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio

Cultural, 11 (1):107-119. http://ojsull.webs.ull.es/ojs/index.ph p/Revista/article/view/15 Morère, N. y Jiménez, J. 2006.

“Análisis del turismo arqueológico en

España. Un estado de la cuestión”.

Estudios Turísticos, 171: 115139.http://bddoc.csic.es:8080/detalles. html?id=624470&bd=ARQUEOL&tab la=docu

Morondo, I. (2017, April 16). La vieja

Oiasso, cada vez más real. El diario vasco. Retrieved from http://www.diariovasco.com/bidasoa /irun/201704/16/vieja-oiasso-cadareal-20170416003131-v.html Ortíz Coder, P. 2012. “Museo Virtual

Hiperrealista”. Virtual Archaelogy

Review. 3, (7): 23-26. https://doi.org/10.4995/var.2012.4375 Ortíz Coder, P. 2013. “Digitalización automática del patrimonio arqueológico a partir de fotogrametría”. Virtual Archaelogy

Review, 4 (8):46-49. https://doi.org/10.4995/var.2013.4287 Osuna Ruiz, M. (1976). Ercávica I.

Aportación al estudio de la Romanización de la Meseta. Arqueología Conquense.

Patronato Arqueológico Provincial.

Diputación provincial de Cuenca y

Ayuntamiento de Cuenca. Papagiannakis, G., Ponder, M., Molet,

T., Kshirsagar, S., Cordier, F.,

Magnenat-Thalmann, N. &

Thalmann, D. 2002. “LIFEPLUS:

Revival of life in ancient Pompeii”.

Proceedings of the 8th International

Conference on Virtual Systems and

Multimedia (VSMM’02). https://www.researchgate.net/public ation/37444098_LIFEPLUS_Revival_ of_life_in_ancient_Pompeii_Virtual_

Systems_and_Multimedia Pérez García, J.L, Mozas calvache,

A.T, Cardenal Escarcena, F.J. y López

Arenas, A. 2011. “Fotogrametría de bajo coste para la modelización de edificios históricos”. Virtual

Archaelogy Review, 2 (3), 121-125. https://doi.org/10.4995/var.2011.4633 Ponce, G. y Rubio, L. 2013. Gestión del patrimonio arquitectónico, cultural y medioambiental. Enfoques y casos prácticos. Alicante: Universidad de

Alicante; México: Universidad

Autónoma Metropolitana. http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/nd /ark:/59851/bmc47631 Ramírez Sánchez, M., Súarez Rivero,

J.P. y Castellano Hernández, M.A. 2014. “Epigrafía digital: tecnología 3d de bajo coste para la digitalización de inscripciones y su acceso desde ordenadores y dispositivos móviles”.

El profesional de la información, 23 (5): 467-474. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2014.sep.0 3 Rowan, J. 2010. Emprendizajes en cultura: discursos, instituciones y contradicciones de la empresarialidad cultural. Traficantes de sueños.

Madrid. https://www.traficantes.net/libros/e mprendizajes-en-cultura Rubio Rivera, R. 2013. “Los orígenes de Ercávica y su municipalización en el contexto de la romanización de la

Celtiberia meridional “. Vínculos de

Historia, 2:169-183. http://dx.doi.org/10.18239/vdh.v0i2.6 3 Ruiz Torres, D. 2013. La realidad aumentada y su aplicación en el patrimonio cultural. Trea. Gijón. Santacana Mestre, J. y Serrat Antolí,

N. 2007. Museografía didáctica. Joan

Santacana Mestre y Nuria Serrat

Antolí (coord.). Ariel, Barcelona. Santamaría Peña, J. y Sanz Méndez, T. 2011. Fundamentos de fotogrametría.

Universidad de La Rioja, Material

Didáctica, Ingenierías. 16. Tahoon, D.M.A. 2016. “Simulating

Egyptian Cultural Heritage by

Augmented Reality Technologies”. 1st BUE Annual Conference &

Exhibition, 1-10. http://www.bue.edu.eg/pdfs/Researc h/ACE/5%20Online%20Proceeding/2 %20Smart%20Heritage1%20(SBNE02)/Simulate%20Egyptia n%20Cultural%20Heritage%20using %20Augmented%20Reality%20Tech nologies,%20Case%20Study.pdf Querol Fernández, M.A. 2010.

Manual de gestión del patrimonio cultural. Akal. Madrid. Querol Fernández, M.A y Martínez

Díaz, B. 1996. La gestión del patrimonio arqueológico en España. Alianza

Universidad. Textos. Madrid. Una aplicación recrea el yacimiento arqueológico de Los Millares con realidad aumentada. (2017, July 27)

EuropaPress. Retrieved from http://www.europapress.es/esandalu cia/almeria/noticia-aplicacion-recreayacimiento-arqueologico-millaresrealidad-aumentada20170727171411.html Vlahakis, V., Ioannidis, N.,

Karigiannis, J., Tsotros, M., Gounaris,

M., Stricker, D., Gleue, T. Daehne, P. y Almeida. L. 2002. “Archeoguide:

An Augmented Reality Guide for

Archaeological Sites”. Computer

Graphics in Art History and

Archaeology, 22 (5) : 52-59. 10.1109/MCG.2002.1028726