OLIVEWOOD TIES

Rooting peace and healing in the divided landscape of Israel/Palestine

Samantha Miller

LARC 598 / GP2

2022-2023

Supervisor: Fionn Byrne

Committee Members: Izzeddin Hawamda, Justin-Benjamin Taylor, Nada Awadi

Submitted in partial fulfillment for the Master of Landscape Architecture, School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, University of British Columbia.

نوتيزلا طباور / תיז ץע רוביח

Olivewood Ties

Rooting peace and healing in the divided landscape of Israel/Palestine.

By: Samantha Miller

Bachelor

of

Environmental Design (Landscape and Urbanism), University of Manitoba, 2020.

Submitted in partial fulfillment for the Master of Landscape Architecture, School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, University of British Columbia.

Supervisor: Fionn Byrne

The University of British Columbia May 2022 ©

* Trigger Warning *: This content deals with matters relating to traumas such as genocide and displacement, as well as war/conflict, and mourning/loss.

This PDF document is interactive and compatible with most PDF viewing software. Words highlighted and underlined in red can be clicked on to be taken to the definitions page. Click the ‘back’ button on the definitions page to return to the page you were on last.

ABSTRACT

Past and present peace negotiations have failed to propel Israelis and Palestinians to coexistence and liberation. These nations have conflicting collective narratives that make it challenging to accept the legitimacy of the other’s right to exist. Furthermore, physical barriers to peace, such as the nearly 800-kilometre separation barrier, erode possibilities for interaction and human connection. This academic endeavour challenges the myth that peace and war are binary and cannot exist simultaneously. Upon the acceptance that the consequences of war are sociocultural and spatial, we can begin navigating a spatial strategy for peacebuilding. Both groups share a deep-rooted love and respect for the land they call home or dream of one day returning to. Because of this, these communities have enmeshed realities, and their futures are both tied to each other and the land.

Olivewood Ties investigates how landscape can be a peacebuilding mechanism in the divided context of Israel/Palestine. Presently and historically, trees in Israel/Palestine were proxy soldiers, employed in warfighting, land acquisition, and nation-building. If trees and flora were instead proxy peacebuilders, what implications do different landscape design strategies possess and moreover, what opportunities do they offer as a mechanism toward healing and unity? This project aims to reveal the faces of perseverance, the activist groups who unite Israelis and Palestinians, and the trees who bore witness to the tears of suffering and celebration of liberation.

< Front Matter > iii

Front Matter

Abstract

Contents

List of Figures

Acknowledgments

Positionality + Disclaimer

Introduction

Part 1: Diaspora & Manifestations of Rootedness

Diaspora

The Wall

The Pine and the Olive

Literature Review and Methods

Literature Review

Landscapes are Peacebuilding Mechanisms Methods Precedent Studies

and Counter Stories Story 01: Displacement / Mourn

02: Disruption / Unity

03: Uproot / Root

iv < Front Matter >

CONTENTS

Conclusion End Matter Definitions Schedule Bibliography ii iii iv vi x xii 1 7 8 12 18 27 28 32 34 40 55 58 68 78 91 95 96 98 100

Stories

Story

Story

< Front Matter > v

Fig. 1. Olive Trees outside of Al-Aqsa Mosque, Jerusalem, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 2. Two Cupressus sempervirens in Jerusalem, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 3. Hebron, the home of Abraham, Issac and Jacob, 1899, Israeli Archives. Public Domain.

Fig. 4. Map of current legal/de facto borders in Israel/Palestine using Google Earth imagery as a base, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 5. Overlooking Masada, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 6. Concept diagram, Samantha Miller.

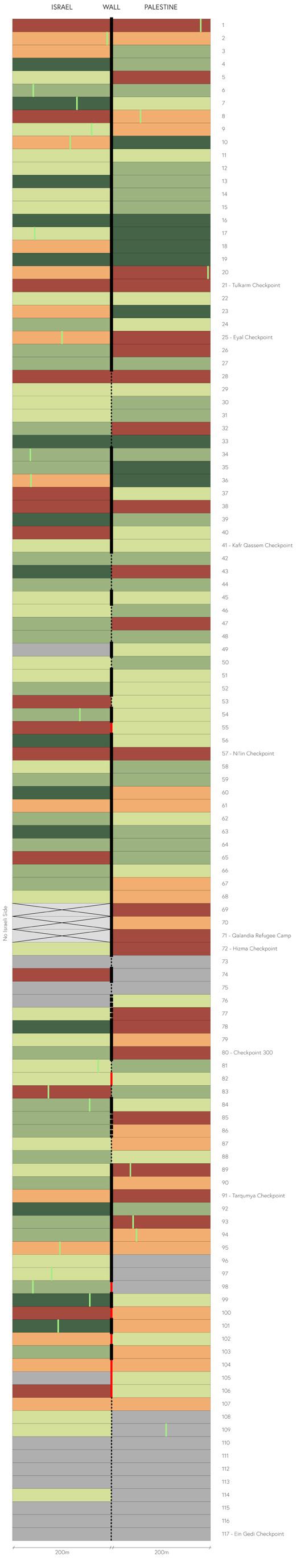

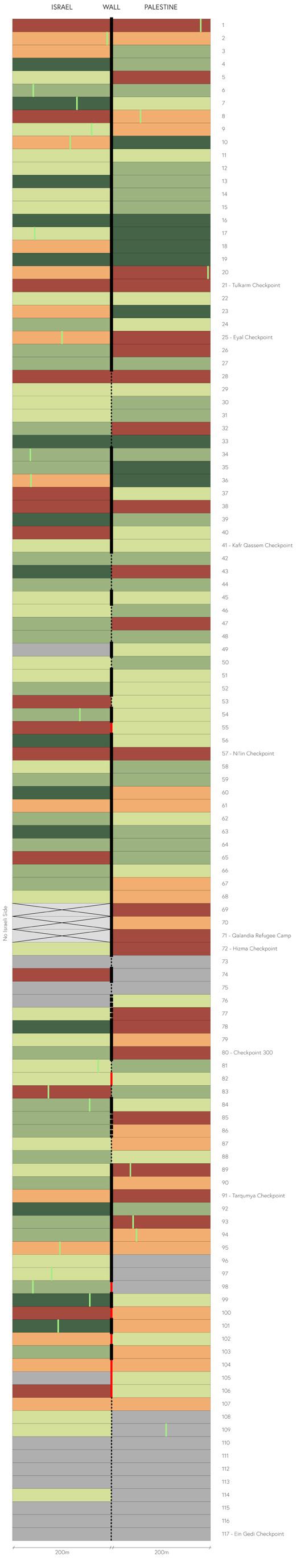

Fig. 7. Map of wall and checkpoints, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 8. A section of the West Bank separation barrier in Bethlehem, April 2009, Daniel Case, Public Domain.

Fig. 9. Israeli West Bank barrier near Jerusalem, September 2010, Antoine Taveneaux, Public Domain.

Fig. 10. Diagram of the Green Line and the Wall, Samantha Miller.

Map of Separation Barrier, surrounding political and ecological contexts, and land use index chart, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 11. Map of Separation Barrier and surrounding political and ecological contexts, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 12. JNF blue boxes, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 13. View from Yad Vashem Holocaust Museum, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 14. Drawing of sample 101 from land use index showing pine habitat and relationships, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 15. Olive trees near Nablus, 2022, Izzeddin Hawamda.

Fig. 16. Drawing of sample 20 from land use index showing olive habitat and relationships, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 17. Planting scheme axo sketches, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 18. Planting scheme axo sketches, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 19. Location of precedents, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 20. Freedom Park in Salvokop, Pretoria, September 2013, Leo za1. Public Domain.

Fig. 21. Isivivani - Freedom Park. Pretoria, South Africa, June 2011, Shosholoza. Public Domain.

Fig. 22. Freedom Park, Salvokop, Pretoria , September 2013, Leo za1. Public Domain.

Fig. 23. The Walled Off Hotel by Banksy in Bethlehem, West Bank, March 2017, Addy Cameron-Huff. Public Domain.

Fig. 24. The segregation wall in front of the walled off hotel, May 2017, no author. Public Domain.

Fig. 25. Banksy mural of Palestinian and Israeli solider having a pillow fight painted in one of the hotel rooms (by Walled Off Hotel, n.d.)

Fig. 26. Stepped amphitheatre using marble retrieved from nearby doorsteps, 2007, Karl Linn.

Fig. 27. Community members actively engaging in collecting and preparing salvaged materials, post construction, and making music while construction occurred, 2007, Karl Linn.

Fig. 28. Completed project with stepped amphitheatre and play area, 2013, Anna Goodman.

Fig. 29. Map of three intervention sites atop locations of forests and olive groves, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 30. Map of location of olive groves and pine forests, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 31. Khirbet Zakariyya before the Nakba, Palestine Remembered.

Fig. 32. Attack on Khirbet Zakariyya, Israeli Archives. Public Domain.

Fig. 33. Hill where Khirbet Zakariyya was, Hasan Hawari.

Fig. 34. Officer from 1948 drinking from well, Israeli Archives. Public Domain.

Fig. 35. Stones left behind, 2007, Noga Kadman.

vi < Front Matter >

LIST OF FIGURES

Fig. 36. Map of destroyed villages and forests, with story 01, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 37. Context and access map for Story 01, using Google Earth Imagery as a base, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 38. Full site plan showing clearly marked gardens in the footprints of destroyed homes, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 39. Full site section, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 40. Zoomed-in plan of one of the footprint gardens, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 41. A place to witness the mourning of others, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 42. Moving rubble to make gardens becomes an act of acknowledging and making space for mourning, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 43. Perspective of one of the marked home gardens in Ben Shemen Forest, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 44. Files on no man’s land, 1948, Israeli Archives. Public Domain.

Fig. 45. Files on Oasis of Peace, 1993, Israeli Archives. Public Domain.

Fig. 46. Greek aircraft helping in firefighting efforts, 2016, Avi Ben Zaken. Public Domain.

Fig. 47. Firefighting plane near Nataf, 2016, Ronen Zvulun.

Fig. 48. Palestinian firefighters aid in firefighting, 2016, Lior Mizrahi/Getty Images. Public Domain.

Fig. 49. Map of national burning index and forests, with story 02, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 50. Context and access map for Story 02, using Google Earth Imagery as a base, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 51. Full site plan of story 02, showing program spaces for community building in No man’s land, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 52. Gathering space with dense conifers on edge for privacy, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 53. Prayer area facing Mecca and the Western Wall, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 54. Community garden for growing food together, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 55. Cutting burnt trees to build infrastructure or clearing them for space, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 56. Space to eat and gather facilitates cross cultural celebration and dialogue, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 57. Beit Jala residents protest wall, 2016, Ryan Beiler/Activestills.

Fig. 58. Uprooting olives, 2015, Sarit Michaeli.

Fig. 59. Map of violence rings and olive groves, with story 03, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 60. Context and access map for Story 03, using Google Earth Imagery as a base, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 61. List of protected species under Israeli Law that are suitable for the site, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 62. Full site plan of story 03 showing planted terraces through the plans for the wall, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 63. Section through site showing existing olive groves and proposed terraces, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 64. Planting plan of protected species, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 65. Section through terraces, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 66. Moving plants as a guerrilla planting effort to protect Palestinian land sovereignty, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 67. Perspective of story 03, to maintain a sense of rootedness for occupied Palestinians in Beit Jala, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 68. Connection to olive tree you cannot reach, Samantha Miller.

< Front Matter > vii

viii < Front Matter >

Fig. 1. Olive Trees outside of Al-Aqsa Mosque, Jerusalem, Samantha Miller.

< Front Matter > ix

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I was born and raised in Treaty 1 territory in what is now known as Winnipeg, Manitoba. These lands are the traditional and ancestral territories of the Anishinaabeg, Cree, Oji-Cree, Dakota and Dene Peoples and the homeland of the Métis Nation. I recognize that the lands in which I grew up were shaped by these Nations.

Now, I live in so-called Vancouver, on the traditional and unsurrendered territories of the xʷməθkʷəyəm (Musqueam), Sḵwxwú7mesh (Squamish), and Selílwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations. I am studying at the University of British Columbia, which is a colonial institution sitting on the traditional and unsurrendered territory of the xʷməθkʷəyəm (Musqueam) Nation. These Nations have experienced and continue to experience active colonization, genocide, and dispossession. I recognize that I have personally benefitted from this dispossession. I am committed not to simply acknowledging the Nations of these territories but to understanding, that acknowledgment is an active dedication to decolonization.

Thank you to my friends and family for supporting me in any way possible throughout my academic journey. I appreciate your open-mindedness and sensitivity to this difficult topic. Nick, thank you for being my rock and for teaching me something new every day. Thank you to my friends at رسج/Bridge/ רׁשג, to whom I owe the inspiration for this project. Izzeddin, Sam, Karen, Micaela, Zhila, Leah, Muhammed, Berrigan, Ademola, Frances, Allan, Joanna, Loraine, and Tali – your honesty, empathy, and compassion lifted me and changed my world. A special thanks to my committee members: Izzeddin (Izzy) Hawamda for your encouragement, support, and ability to make beautiful words out of an ugly conflict. It is an honour to work with you. JB and Nada, your encouragement and patience as we worked through best practices and approaches to narrative and design thinking were paramount in the success of this project. To my advisor, Fionn, thank you for pushing me to be rigorous and attentive, but allowing me to express myself in this project. Your knowledge, passion for landscape architecture, and dedication to this project inspired me to test the limits of this work.

For Saba

This project is dedicated to my late Saba, Yoram. A beloved family man, carpenter/ builder/fixer of all things, and soldier. With every word I write, I think of you.

x < Front Matter >

< Front Matter > xi

Fig. 2. Two Cupressus sempervirens in Jerusalem, Samantha Miller.

POSITIONALITY & DISCLAIMER

A large portion of my identity is shaped by my heritage– my roots stemming from a land filled with conflict, displacement, and intergenerational trauma. Half of my ancestors did not survive the atrocities of the Holocaust; those who survived struggled to make a place in the world that didn’t accept them. One who immigrated to Canada, and my first cousin is named for, lived his life as a hoarder, afraid that he would lose everything again. Antisemitism is very much alive and on the rise worldwide.

I have privileges as an Israeli citizen that Palestinians do not, such as the ability to visit, move, and speak freely. While I cannot access certain zones under Palestinian jurisdiction, my access to Israel is expedited. My friends and family in Israel and Palestine endlessly fear for their lives, in and out of bomb shelters, while I only worry from the comfort of my own home, never having feared being displaced. I am a member of a small dialogue group called Bridge, comprised partly of Jews and Palestinians. In that space, I have learned the importance of dialogue, understanding, and listening to each other’s stories and narratives. I learned that there is more that unites us than divides us. It is a privilege to have those conversations, engage in activism, and write this graduate project in Canada without fear of persecution.

As I write this graduate project, a constant existential battle occurs in my mind. Professors and classmates have told me I am somewhat optimistic. I am not naive or overly optimistic. I understand my family, my friends, and my own reality. I have seen peace, and I have felt the consequences of war. I know my words are universalist messages of hope. The conflict is internationalized, and I am playing a part. I know I am suitable to play a part, even if it is just optimism. I do not pretend to understand the lived experience of those who are occupied, but through this project I will listen.

I want to be clear that this project is a love letter to my country. The land that many people and myself feel deeply connected to. The olive groves, the fruit trees, rolling hills, and valleys are part of me. It is because of my connection and love for this land that I wish to see it progress. I think of my family, my friends, and my friend’s family who do not deserve to live in fear or occupation. I think of future generations who deserve peace and liberation.

xii < Front Matter >

< Front Matter > xiii

Fig. 3. Hebron, the home of Abraham, Issac and Jacob, 1899, Israeli Archives. Public Domain.

Introduction

In the contested landscape of Israel and Palestine, populated by communities with conflicting narratives, storytelling and placemaking plays a critical role in peacebuilding and mediating political tension. This project will study methods in landscape architecture that may reveal connections, stories, differences, and similarities embedded in the fabric of the landscape. While the Israeli-Palestinian situation is immensely complicated, this project takes a land-based approach to mediating what is ultimately a conflict rooted in the land. We are perpetually disappointed when we put our faith in politicians to facilitate conflict resolution. These past and present attempts at peace have created a landscape of estrangement through the construction of a ‘separation barrier,’ checkpoints, separate roads, and by using trees to fight wars or root oneself in the landscape. These divisive strategies not only divide the land but also divides those who inhabit it. Attempts at political peace to date are keeping everyone in a zero-sum game. No community’s freedom, liberation, and safety should come at the expense of another’s.

Israelis and Palestinians experience intergenerational trauma caused by centuries of persecution, displacement, islamophobia and antisemitism. Past social trauma, such as the experience of diaspora, fosters a distrust of others, a collective identity formed around victimhood, and bolsters us-versus-them thinking.1 A drastic mind shift happens when community members engage in humanizing dialogue and begin listening to each other’s narratives. We start to realize that our grief is the same grief. Storytelling and prioritizing discussion of personal, present experiences of the conflict increases empathy and intergroup acceptance in Israeli-Palestinian dialogues.2 These communities deserve a safe physical space that invites conversation, reflection, and storytelling. The manipulation of physical space can tell a story of deep love for the land, whether you live

there now or dream of returning one day. In Peacebuilding and Spatial Transformation: Peace, Space and Place (2017), Annika Björkdahl and Stefanie Kappler affirm:

“Spaces of war can be transformed into spaces of peace– and vice versa. Places therefore always hold the possibility of hosting spaces that reinforce division or that challenge and overcome the latter. It is the forms of agency that develop around a particular place that determine its social meanings and functions.”3

-Annika Björkdahl and Stefanie Kappler

Moreover, this project is a dialogue in and of itself. By approaching this topic with empathy at the forefront, we start to see the conflict through a new lens. We open the floor for discussions on the cultural symbolism of trees, the landscape manifestations of rootedness after diaspora, being willing to open oneself to new and challenging narratives, and the landscape practices of warfighting or peacebuilding.

Traumatic experiences of diaspora that both Israelis and Palestinians experience fosters a desire for rootedness. To feel safe, secure, and liberated in the land. Our futures are threads that are now and forever entangled with one another. Perhaps the strongest thread is the one that runs deep into the landscape and ties us to it. In this way, the landscape is common ground. While it may be politicized and divided, the landscape is unprejudiced. The air we breathe is the same air, the water’s flow is unrestricted by borders, and the olive trees that grow on both sides are symbols of peace, truth, steadfastness, and perseverance. Olive trees take decades to produce fruit and can only be cultivated after enduring long-lasting stability, making their designation as a peace symbol properly ironic in this land.4 Olive cultivation and the use of charred olivewood in construction are traced back in this land likely to the Early Bronze Age.5 In Apeirogon: A Novel, author Colum McCann writes:

2 < Introduction >

INTRODUCTION

“In his first century B.C. treatise De Architectura, Vitruvius Pollio said that all walls which require a deep foundation- from barriers to huge wooden defence towers- should be joined together with charred olive ties. Olive wood does not decay even if buried in the earth or placed deep in water.”6

- Colum McCann

The olive tree, representing steadfastness for Palestinians and their territorial claim to Israel/Palestine, is paralleled with the symbolic importance of the pine tree for Israelis. The pine tree came to symbolize Jewish rootedness in the landscape because of the Jewish National Fund: Israel’s intermediary for land acquisition and prime afforestation agency. It is precisely because of the pine and the olive’s metaphorical rootedness in the landscape that they were natural proxy-soldiers, proxy-nation-builders, and easy targets. Pine forests are often located atop destroyed Palestinian villages and are often victims of arson attacks. Olive trees have been uprooted to make way for watchtowers, checkpoints, and the separation barrier.

The 708-kilometer built separation barrier that divides Israel and the West Bank is the physical manifestation of tension, division, and a desire for rootedness and security. The construction of borders is often used to keep unjust systems frozen in space and time and to maintain power imbalances.7 The wall has tattered opportunities and destroyed physical spaces for human connection and dialogue between both groups, and “exacerbated the conflict and contributed to the emergence of a segregated landscape.”8 Traversing agricultural land and desert, pine forests and olive groves, dividing cities and surrounding settlements, the wall epitomizes Israel’s endeavour to exert power and territoriality and practice the act of enclosure.

For Israelis, the wall symbolizes security, strength, and defence. For Palestinians, the wall symbolizes

theft, occupation, and an unreachable statehood. Symbolism, however, does not change the fact that children grow up in these landscapes shaped by conflict in a home shadowed by a concrete wall. The construction of the separation wall uprooted hundreds of hectares of olive trees9 and made many olive groves inaccessible for cultivation and care. Three sites for intervention at the separation wall will study relationships in a divided landscape and the roles trees and spacemaking play in peacebuilding. The olive tree will guide the design process as a statue of strength, a symbol of peace, and reinforce ties to each other and the land.

“The world I was born into, the one I grew up in, made no sense. Surrounded by such beauty: the land full of rolling hills, green pastures, clear streams, and strong olive trees, the community full of welcoming neighbours who became extended family, the sun, the rain, the animals on the farm. That is home. Also surrounded by: armed soldiers, giant military tanks, stolen land, homes destroyed, a 25-foot wall preventing the freedom to travel, daily checkpoints, ID checks on the way to school, death, sadness, anger. That, too, is home. In reflecting back I am acutely aware of my desire to make sense of the dichotomy in which I existed.”10

– Izzeddin Hawamda

< Introduction > 3

4 < Introduction >

Fig. 4. Map of current legal/de facto borders in Israel/Palestine using Google Earth imagery as a base, Samantha Miller.

Endnotes

1. Julia Chaitin and Shoshana Steinberg, “”You should Know Better”: Expressions of Empathy and Disregard among Victims of Massive Social Trauma,” Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 17, no. 2 (2008): 205.

2. Ella Ben Hagai, Phillip L. Hammack, Andrew Pilecki, and Carissa Aresta, “Shifting Away from a Monolithic Narrative on Conflict: Israelis, Palestinians, and Americans in Conversation,” Peace and Conflict 19, no. 3 (2013): 298.

3. Annika Björkdahl and Stefanie Kappler, Peacebuilding and Spatial Transformation: Peace, Space and Place, 1st ed, London: Routledge, 2017, 138.

4. Rami Sarafa, “Roots of Conflict: Felling Palestine’s Olive Trees,” Harvard International Review 26, no. 1 (2004): 13.

5. Nili Liphschitz et al, “The Beginning of Olive (Olea Europaea) Cultivation in the Old World: A Reassessment,” Journal of Archaeological Science 18, no. 4 (1991): 450.

6. Colum McCann, Apeirogon: A Novel, First ed, New York: Random House, 2020, 170-171.

7. Björkdahl and Kappler, 143.

8. Silvia Hassouna, “Spaces for Dialogue in a Segregated Landscape: A Study on the Current Joint Efforts for Peace in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict,” Conflict Resolution Quarterly, vol. 34, no. 1, 2016, pp. 57-82.

9. Gary Fields, “Landscaping Palestine: Reflections of Enclosure in a Historical Mirror,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 42, no. 1, 2010, 75.

10. Izzeddin Hawamda. Quote derived from a text exchange in September 2022, with permission granted for this purpose. Izzeddin is a teacher, activist, Ph.D. candidate, poet, storyteller, and dear friend of mine. He co-founded the IsraeliPalestinian Dialogue group, Bridge, of which I am a part. Growing up in a rural village near Nablus in the West Bank, Izzy offers an invaluable perspective that he manages to put into words in eloquent poetry and stories.

< Introduction > 5

Part 1: Diaspora & Manifestations of Rootedness

“Individual members of groups in conflict with one another are in fact profoundly defined by the conflict itself, meaning that resolution of the conflict means removing a — if not the — definitive aspect of group members’ shared identity.”1 –

Ingrid Anderson

I am a Jewish person with Israeli citizenship who grew up in a very one-sided milieu, view of history, and education on the conflict. While I have expanded my worldview to become as neutral as possible, I am still biased. In this section, I attempt to summarize some of the histories and narratives that set the context for this project. I will not try to pretend like I completely understand both sides and can, therefore, adequately speak for either. I especially leave room for personal Palestinian experiences and narratives to be heard and told by those who truly know them. The history of Israel/Palestine, its lands, and its peoples is a complex set of narratives on ownership, control, and competing national identities. I have included a timeline of key narratives in this section. However, it is critical to begin with an understanding of the primary narratives that make coexistence and peace more difficult to achieve.

Trauma, Belonging, Displacement

Whether or not as a Jew, you are religiously observant or what many call ‘culturally Jewish,’ having a connection to Eretz Israel (the Land of Israel) is one of the primary pillars of Judaism. Most Jews see ancient history as a story of exodus, genocide, and triumph. This very deeprooted cultural tale of one day returning to Israel prevents many Jews from being willing to part with this sense of belonging in any capacity. It is also why many Jews reject terms like ‘settler’ or ‘colonizer,’ as Israel is the land they feel a sense of belonging and indigeneity. The Zionist movement that brought Jews back to Israel is contested among the Jewish community. Still, the primary principle that Jews belong in Israel

and always have is less disputed. The many holy and sacred places in Israel/Palestine (the terms I use to describe the land as it is today) further connect Jews with their ancient history, such as the Western Wall in Jerusalem, the last standing wall of the Second Temple from the 2nd century BCE. Overlooking the Dead Sea, Masada houses ancient remains of a Jewish fortification built to resist Roman troops and is also where I had my Bat Mitzvah at age thirteen. While Jews existed in Israel/Palestine long before the birth of Islam, Arab presence in the land is also ancient. The Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa Mosque, built by the Umayyads after the Muslim Conquest, is a holy site for Muslims worldwide. Arab tribes fought against Byzantine and Roman invasions, just as Jews did if not alongside them. But these two communities and countless foreign powers wrestled for control of Palestine. It must also be acknowledged that the most recent foreign entity to control the land, the British, played a critical role in dividing Arabs and Jews and kickstarting the current conflict as it exists today.

8 < Diaspora >

DIASPORA

Fig. 5. Overlooking Masada, Samantha Miller.

The Holocaust and the Nakba

Israelis and Palestinians both experienced and continue to experience trauma relating to displacement. The two primary events contributing to this collective feeling are the Holocaust and the Nakba. The growing wave of violence against Jews worldwide, especially in Europe, stimulated desperate immigration to Palestine. The Holocaust resulted in the systematic genocide of over 6 million Jews at the hands of the Nazis. Research has shown that traumas of massive social violence, such as the Holocaust, haunt victims and their decedents for many years as the trauma is biological, sociocultural, psychodynamic and familial.2 Holocaust studies are hyper-prevalent in Jewish schools and programs worldwide. Delegate groups like March of the Living sends groups of students to death camps across Poland, strengthening the notion of needing a safeguard that would protect Jews from another genocide. It certainly does not help matters that millions of people deny the factuality of the Holocaust, and white-nationalist Nazi groups worldwide terrorize the memory of this trauma.

The aftermath of the Shoah saw the immigration of deeply traumatized and displaced Jews who became beneficiaries of the traumatic displacement and forceful removal of the Palestinian people. This mass exodus and displacement of approximately 750,000 Palestinian people from the land is referred to as al-Nakba (the catastrophe). The Nakba occurred in 1948, beginning the morning after Israel declared its independence and ended the British Mandate for Palestine. That morning, Jordan, Egypt, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen joined forces to enter the newly formed state and attack. Israel won the war after ten months of fighting and occupied even more territory than they held during their Declaration of Independence. Almost every Palestinian has

been affected by the Nakba, regardless of age or location. Similarly to the Jewish collective trauma, victims and their decedents continue to suffer.

According to most Israeli narratives, the hundreds of thousands of Palestinians who left during the war did so voluntarily as they expected and were told that they may eventually return to their homes after an Arab victory, which ended up not happening.3 The trauma of the Nakba became the essence of the Palestinian cause post-1948, and the narrative of an uprooted nation of refugees emerged.4 The Palestinian narrative claims that Palestinians have lived in this region for 1500 years and made up 90% of the population at the time when the British issued the Balfour Declaration.5 Mourid Barghouti describes this feeling of displacement and diaspora in I Saw Ramallah, writing:

“Because of the many places that the circumstances of the Diaspora made us live in, and because we so often had to leave them, our places lost their meaning and their concreteness.”6

-Mourid Barghouti

The argument about which group has suffered more as a collective is a typical proponent in many discussions of national belonging. Even Jewish Israelis who are critical of the Zionist movement and actions that have been taken on their behalf by the Israeli government often rely on this very comparison that views them as ‘inheritors of Jewish fate and tragedy’ as having greater victimhood than the Palestinians and their suffering.7 The fact of the matter is that both groups have suffered at the hands of the other and the hands of external foreign forces. For Israelis, omnipresent existential fear and memories of trauma and victimhood make it difficult to acknowledge their oppression of the Palestinians. Palestinians’ demand for dignity, justice, and liberation is fueled by “seemingly permanent humiliation, indignity, dispossession

< Diaspora > 9

and disrespect.”8 They are constantly reminded of the unbalanced power dynamics and feel that Israel (with the United States at their side) is to be blamed for their suffering and Israel’s destruction is necessary if they are to see an end to occupation and achieve just independence.9

At the heart of it, neither group accepts the other’s legitimacy, narrative, or right to exist. Both experience distrust and intergenerational trauma and believe they would be safer and happier if the other found somewhere else to live (which, of course, will never happen). One-state, two-state, or no-state, there is no future where either will be satisfied so long as no one speaks to each other or acknowledges the other’s right to exist. Facts can be disputed, and the history of this land is so ancient that texts and discoveries have been revisited and retranslated countless times.

It is not up to one person to say that someone else’s entire belief system and one group’s entire collective narrative is wrong. It is imperative at this point that we move toward a place where we can acknowledge that two truths can exist at once, and the future holds the possibility for a new collective identity, one that is not based on the delegitimization of the other.

While suffering and displacement are a pillar of both narratives, it is paramount to remember that these stories are also tales of resilience. Palestinians have continued to persevere under consistent occupation, and Israelis have been resilient to continuous external threats made against them by their many enemies. They will continue to make a home for themselves in the land they love and care for.

10 < Diaspora >

< Diaspora > 11

Fig. 6. Concept diagram, Samantha Miller.

LANDSCAPE MANIFESTATIONS OF ROOTEDNESS 01: THE WALL

“You cannot be a complete person alone... For that you must be part of, and rooted in, an olive grove... Because without a sense of home and belonging, life becomes barren and rootless. And life as a tumbleweed is no life at all.”10 –

Thomas Friedman

A land flowing with milk and honey, the ‘Holy Land.’ A piece of land that is roughly the same size as Lake Winnipeg, where I spent much of my time growing up. It connects three continents, bridging flora and fauna, climates, and conditions of Africa, Asia, and Europe. Snow and bears exist in the north, while camels and sand dunes live in the south.11 Rivers, mountains, seas, swamps, valleys, and riverbanks. Vegetables, fruit trees, wheat fields, grape vineyards, and olive tree groves. These are more than ecological conditions; they represent a greater desire for rootedness. There are many environmental factors to this conflict that characterize both Israeli’s and Palestinians’ desires to find stability and rootedness in the land to counter their experience of diaspora. The calculated use of trees and walls in this conflict highlights how the landscape reflects the existing political and social context.

The Wall: Strongholding

Hamas, a widely recognized terrorist organization, launched a series of suicide bombings and attacks in Israel starting around 1993.12 These perpetrators detonated explosive devices on their bodies in very public areas in Israel. These terrorists’ signature bombing locations were public buses. I remember family members being anxious about public buses and being sensitive to this subject when I was growing up. In the same year, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, Israeli Defence Minister Shimon Peres, and Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) Chairman Yasser Arafat met with United States President Bill Clinton to negotiate peace processes and agreements. The resulting signed

‘Oslo Accords’ are notoriously disappointing as many grave issues were left unresolved, and most parties felt unfulfilled. Hopes were high as people worldwide witnessed a historic handshake on the White House lawn. To the world, the Oslo Accords appeared somewhat successful, even earning Rabin, Peres, and Arafat the Nobel Peace Prize in 1994.13 However, these signed arrangements were just the beginning of continued violence and failures on all sides to implement any agreements. Individuals suffering in this conflict felt that they were either no closer to reaching security or no closer to independence and statehood; this process “progressively eroded confidence on both sides.”14 A second Oslo Accord was signed in 1995, which saw Israel relinquish control of some of Gaza and the West Bank to the Palestinian Authority (PA) (formerly PLO.)15 Shortly after, a twenty-seven-year-old student assassinated Rabin in opposition to his negotiations with Palestinian leaders. Ehud Barak was elected Prime Minister of Israel and continued negotiations and withdrawal processes. Clinton hosted another meeting at Camp David, which saw fourteen days of negotiations in which no deals were made, and no issues resolved.16 Lack of progression to peace was fueled by Palestinian refusal to take responsibility for terrorism, security, and diplomacy, and Israeli refusal to let go of land annexed.17

Shortly after Camp David in 2000, Israeli opposition leader, and later Prime Minister, Ariel Sharon made the injudicious decision to visit the temple mount with hundreds of armed guards. Some scholars suggest that his visit intended to strengthen Israel’s entitlement to a united Jerusalem, and to undermine Ehud Barak, his political rival.18 The substantial military presence at the sensitive site provoked riots and violence. While Sharon’s visit triggered the uprising, it was not the cause. The cause was pent-up frustration with the peace process, seeing no change in everyday life, and anger.19 This event threw

12 < The Wall >

Israelis and Palestinians into an unimaginable wave of violence known as the Second Intifada. The First Intifada, while slightly less violent, ended around 1991. Stone-throwing, rioting, suicide bombings, and killings were met by the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) with even more violence, including but not limited to tear gas, rubber bullets, tanks, and rockets. Instances of suicide bombings increased and continued to occur in public places such as malls, buses, street corners, and restaurants. The number of suicide bombings reached around 120, and death tolls were in the thousands.20 Violence, negotiations, mass murders, elections, and assassinations continued. Israel launched ‘Operation Defensive Shield’ in 2002. The operation commenced a military occupation of much of the West Bank and its major cities and towns, which saw the arrest of thousands of Palestinians. Israel began the construction of the separation barrier in June 2003.21 At the time, this decision was the latest strategy employed to dominate and progress Israel nationalist intentions and to keep the unwanted ‘others’ out.

While the Israeli population sees the wall as a security measure to prevent terrorist attacks, International Law sees closures as a method of collective punishment.22 The current occupation has divided Palestinians into different levels of residency, whether it be Jerusalem residents, West Bank residents, Gaza identity, or even those holding Jordanian passports. Each group holds a definite hierarchy that determines how much freedom or access that person is entitled to.23 However, Jews worldwide are given automatic citizenship should they return to Israel according to the Israeli Law of Return and are provided easy access anywhere in the country. The checkpoints allow the IDF to decide who gets to pass through and who doesn’t. Closure and checkpoints restrict Palestinian’s access to employment, healthcare, and farming practices. In the resulting landscape “social networks and community are disrupted, and memories of place and familiar routes begin

to recede, replaced by a circumscribed space of everyday life.”24 Thousands of Palestinians funnel through unsanitary and overcrowded checkpoints every day. Checkpoints are embarrassing, discriminating, and unpredictable. The wall, checkpoints, and watchtowers allow Israel to assert visual dominance over the Palestinian territories. While Israelis and Palestinians live in close proximity as neighbours, the wall renders them distant. Author of Apeirogon: A Novel, Colum McCann writes:

“For him, everything still came back around to the Occupation. It was a common enemy. It was destroying both sides. He didn’t hate Jews, he said, he didn’t hate Israel. What he hated was being occupied, the humiliation of it, the strangulation, the daily degradation, the abasement. Nothing would be secure until it ended. Try a checkpoint for just one day. Try a wall down the middle of your schoolyard. Try your olive trees ripped up by a bulldozer. Try your food rotting in a truck at a checkpoint. Try the occupation of your imagination. Go ahead. Try it.”25

-Colum McCann

< The Wall > 13

Fig. 7. Map of wall and checkpoints, Samantha Miller.

14 < The Wall >

Fig. 8. A section of the West Bank separation barrier in Bethlehem, April 2009, Daniel Case, Public Domain.

Fig. 9. Israeli West Bank barrier near Jerusalem, September 2010, Antoine Taveneaux, Public Domain.

The wall is now almost 800 kilometres long. Some sections are made of prefabricated concrete slabs, and some sections are made of metal fencing and razor wire. It is punctuated by watchtowers and firing posts around every 300 meters. Beside the wall, a gravel road makes up the ‘buffer zone’ where military patrols travel and set up remote sensors, cameras, and barbed wire.26 The wall roughly follows the green line, although it is roughly double its length due to its tendency to include Israeli towns built inside the west bank and surround important land assets like forests and scrublands. The wall separates farmers from

their lands and families from one another. It prevents the flow of not just people but of flora, fauna, and ecological processes.

Sampling the wall every 5 kilometres illuminated that the wall traverses many different land types and, most importantly to this project, two very distinct physical manifestations of national rootedness in the landscape - the pine tree and the olive tree. The wall uprooted thousands of acres of agricultural land and tens of thousands of trees.27

< The Wall > 15

THE GREEN LINE + STATEHOOD THE ‘GREEN LINE’ IS THE 1949 ARMISTICE LINE, DRAWN BY ISRAEL AND JORDAN FOLLOWING THE 1948 WAR IT BECAME THE DE-FACTO BORDER BETWEEN ISRAEL AND PALESTINE WALL IS OFTEN BUILT TO INCLUDE ISRAELI SETTLEMENT/TOWN LAND GRAB MAKES A 2-STATE SOLUTION MORE DIFFICULT TO ACHIEVE AS THE DE-FACTO STATE LINE OF PALESTINE DIMINISHES ‘NO MAN’S LAND’ OCCURS WHERE THE CRAYONS OF THE JORDANIAN AND ISRAELI OFFICIALS DID NOT CLOSELY OVERLAP ‘GREEN LINE’ SEPARATION WALL OCCUPIED PALESTINIAN TERRITORY ISRAEL RAMALLAH JERUSALEM 0km 4km 8km 2km

10.

Fig.

Diagram of the Green Line and the Wall, Samantha Miller.

Map

16 < The Wall > LAND TYPE INDEX AT SEPARATION WALL MAP OF SEPARATION WALL AND INDEX SAMPLES WITHIN SURROUNDING POLITICAL, SPATIAL, AND ECOLOGICAL CONTEXTS BUILT WALL WALL UNDER CONSTRUCTION WALL PLANS APPROVED WALL PLANS VOIDED GREEN LINE (1949 ARMISTICE LINE) WATERWAY SAMPLE AREA WATERBODIES PALESTINIAN LOCALITIES ISRAELI LOCALITIES AREA B: PALESTINIAN ADMIN + ISRAELI SECURITY AREA A: PALESTINIAN ADMIN + SECURITY AREA C: ISRAELI ADMIN + SECURITY CHECKPOINT DESTROYED VILLAGE WESTERN AQUIFER COASTAL AQUIFER NORTH EASTERN AQUIFER EASTERN AQUIFER INSTANCES OF VIOLENCE 0km4 km8 k 2km2 0k 2k TREE COVER - 15 9 SHRUBLAND - 28 | 25 GRASSLAND - 30 26 LEGEND GREEN LINE/1949 ARMISTICE LINE CROPLAND - 14 19 BUILT-UP - 15 22 SPARSE/SAND - 12 16 WALL PLANS APPROVED, NOT YET BUILT BUILT WALL WALL UNDER CONSTRUCTION WALL VOIDED LEGEND

of Separation

political and ecological contexts, and land use index

Samantha

Barrier, surrounding

chart,

Miller.

Fig. 11. Map of Separation Barrier and surrounding political and ecological contexts, Samantha Miller.

Fig. 11. Map of Separation Barrier and surrounding political and ecological contexts, Samantha Miller.

LANDSCAPE MANIFESTATIONS OF ROOTEDNESS 02: THE PINE AND THE OLIVE

In Israel/Palestine, the pine and olive trees have come to represent nationhood through the direct use of these trees as proxy-soldiers and proxynation-builders. The pine and the olive became cultural counterparts and, in a sense, are perfect opposites. The pine roots deeply, fast-growing, and shorter-lived, whereas the olive roots slowly but is long-living and slow growing. They also represent different cultural landscapes, the forest and the field, or even different ideas of human labour.28 Irus Braverman, author of Planted Flags: Trees, Land, and Law in Israel/Palestine, summarizes these cultural counterparts by saying: “The pitting of pine tree/people against olive tree/people reflects the discursive and material split constructed with much fervency and determinacy by the two national ideologies that compete in and over Israel/Palestine.”29 The history of these two trees becoming the symbols they are today likely begins with an analysis of the Ottoman Empire and the land practices and systems they employed in this land when they occupied it. This analysis is outside this project’s scope but a worthy investigation for future research. This section will briefly explain the primary agencies and processes that created these two symbols of nationalism and rootedness.

Pine Tree / ربونصلا ةرجش / ןרוא ץע

Jewish tradition and biblical teachings stress the importance of caring for the land and preserve natural resources. The annual festival in Israel of Tu Bishvat celebrates trees and the mitzvah of planting trees. Throughout recent history, many Zionist projects involved settling recently immigrated Jews in agriculturally fertile land, asking them to land reclamation and cultivation. The Jewish National Fund (JNF) is Israel’s intermediary for land acquisition and their prime afforestation agency, two roles which are co-productive and co-dependent. The JNF has successfully persuaded Jews worldwide to contribute to and become involved in land

cultivation and transformation. The signature JNF blue tin boxes are entrenched in my memory as they sat in the halls of my school, synagogue and youth organization growing up. By putting money in the blue tin box, you could sponsor the planting of a tree and feel rooted in Eretz Israel. The JNF created a widespread perception of the tree as a personal symbol of identity, as described by Simon Schama:

“What we did know was that a rooted forest was the opposite landscape to the place of drifting sand… The diaspora was sand. So what should Israel be if not a forest, fixed and tall.”30 – Simon Schama

Since 1901, the JNF has planted over 240 million trees in Israel, mostly pine trees that became the signature Zionist tree as they ‘re-forested’ the Holy Land.31 Tree planting in masses was a way of rooting outside the physical act. It helped people to fill the hole in their lives caused by recurring social traumas of displacement.32 The state of Israel, hand in hand with the JNF, was able to cloak their political agendas in green, as trees appear neutral but simultaneously claim and occupy the land. Today, the pine tree, among other species, are “icons of national revival, symbolizing the Zionist success in “striking roots” in the ancient homeland.”33 Irus Braverman, author of “Planting the Promised Landscape” writes:

“In the Israeli context, the pine tree has become almost synonymous with the Jewish National Fund (JNF). JNF is probably the major Zionist organization of all time. It is also the most powerful single organized entity to have shaped the modern Israeli/Palestinian landscape.”34

-Irus Braverman

18 < The Pine and the Olive >

< The Pine and the Olive > 19

Fig. 12. JNF blue boxes, Samantha Miller.

20 < The Pine and the Olive >

Fig. 13. View from Yad Vashem Holocaust Museum, Samantha Miller.

< The Pine and the Olive > 21

Fig. 14. Drawing of sample 101 from land use index showing pine habitat and relationships, Samantha Miller.

Olive Tree / نوتيز ةرجش / תיז ץע

The olive tree has been a signature symbol of Arab Palestine and a distinctive feature of the cultural and physical landscape. Olive orchards have been the centre of many land and lawrelated disputes between Palestinians and Israeli settlers since the 1980s and prior.35 For Palestinians, the olive tree represents resistance and Sumud (steadfastness) and has been one of the primary roots of their economy. The olive tree has helped them to strengthen their territorial claims over land and, over time, came to symbolize the Palestinian people as a wholetheir durability, longevity, and strength through the struggle for independence. The olive tree has become a living memory of the Palestinian village and its people and is a silent witness of their suffering36 and their beauty and strength.

While the first few Prime Ministers acknowledged that there were olive groves around most Arab towns, they maintained that the olive trees had been planted by Alexander the Great, and during the Arab conquest, no trees were planted; this created the misconception that Palestinians were neglectful and unproductive.37 Regardless, olives remain integral to Palestinian culture. As of 2008, 50% of the Palestinian population in this region participate in annual olive harvests, and there were around 9 million olive trees in occupied territories.38 Before the Second Intifada in 2000, many rural farmers in the West Bank were employed in Israel. However, since the Intifada resulted in Israel tightening their restrictions on movement in and out of the West Bank, many farmers lost their jobs in Israel. As such, the agricultural sector and the local olive industry in Palestinian culture have increased dramatically since the start of the Second Intifada. In I Saw Ramallah, Mourid Barghouti describes the Palestinian connection to olives and olive oil. He writes:

“After ‘67 my discovery that I had to buy olive oil was truly painful. From the day we knew anything we knew that olives and oil were there in our houses.... For the Palestinian, olive oil is the gift of the traveler, the comfort of the bride, the reward of autumn, the boast of the storeroom, the wealth of the family across centuries... In Cairo I would not let olive oil into my house because I refused to buy it by the kilogram.”39

-Mourid Barghouti

Olive branches have also been a symbol of peace for Jews and Israelis and are wrapped around a sword in the emblem of the Israeli Defense Forces. The decision to use the olive tree in these state emblems came from the consensus that the olive was a concrete symbol of peace and abundant fruit of the land.40 Ultimately, this idea of rootedness is clearly carried through for both peoples and both trees. The Palestinian draws a connection to their ancient presence in the land with the olive tree rooted for thousands of years. The Israeli sees the afforestation task as a method of finally feeling stable in their ancient homeland from which they were displaced. Braveman summarizes this notion in Planted Flags, saying:

“The olive speaks for the uprooted person. The interplay between the olive’s absence and presence in Palestinian narratives could be seen as a mirror image of the pine’s absence and presence with relation to the diaspora Jew, who’s absence from the Promised Land is embodied in the presence of the pine donated in her or his name.”41

-Irus Braverman

22 < The Pine and the Olive >

< The Pine and the Olive > 23

Fig. 15. Olive trees near Nablus, 2022, Izzeddin Hawamda.

24 < The Pine and the Olive >

Fig. 16. Drawing of sample 20 from land use index showing olive habitat and relationships, Samantha Miller.

Endnotes

1. Ingrid Anderson, “Surviving the Story: The Narrative Trap in Israel and Palestine by Rosemary Hollis (Review),” The Middle East Journal 74, no. 2 (2020): 323.

2. Julia Chaitin, “Co-creating peace: Confronting psychosocial-economic injustices in the IsraeliPalestinian context,” In Peacebuilding, Memory and Reconciliation, edited by Charbonneau, Bruno and Genevieve Parent, Routledge, 2012, 147.

3. Michael Rubner, “The Two-State Delusion: Israel and Palestine - A Tale of Two Narratives,” Middle East Policy 23, no. 1 (2016): 164.

4. Omer Bartov, Israel-Palestine: Lands and Peoples, edited by Omer Bartov, 1st ed. New York: Berghahn, 2021, 4.

5. Rubner, “The Two-State Delusion,” 164.

6. Mourid Barghouti, I Saw Ramallah, 1st ed. New York: Anchor Books, 2003, 88.

7. Bartov, Israel-Palestine: Lands and Peoples, 6.

8. Rubner, 164.

9. Rubner, 164-165.

10. Thomas L. Friedman, The Lexus and the Olive Tree, 1st ed. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1999.

11. Rachel Gottesman, Tamar Novick, Iddo Ginat, Dan Hasson, and Yonatan Cohen, Land, Milk, Honey: Animal Stories in Imagined Landscapes, Tel Aviv; Zurich, Switzerland; Park Books, 2021, 34-35.

12. “Historical Timeline: 1900-Present,” Britannica | ProCon, June 14, 2021.

13. “Historical Timeline,” Britannica.

14. Kirsten E. Schulze, “Camp David and the Al-Aqsa Intifada: An Assessment of the State of the IsraeliPalestinian Peace Process, July-December 2000,” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 24, no. 3 (2000): 215.

15. “Historical Timeline,” Britannica.

16. “Historical Timeline,” Britannica.

17. Schulze, “Camp David and the Al-Aqsa Intifada,” 217.

18. Schulze, 216.

19. Schulze, 220.

20. “Historical Timeline,” Britannica.

21. “Historical Timeline,” Britannica.

22. Julie Marie Peteet, “Permission to Breathe: Closure and the Wall” in Space and Mobility in Palestine,

Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2017, 35.

23. Peteet, “Permission to Breathe”, 37-38.

24. Peteet, 40.

25. Colum McCann, Apeirogon: A Novel, First ed, New York: Random House, 2020, 123.

26. Peteet, 42.

27. Peteet, 42.

28. Irus Braverman, Planted Flags: Trees, Land, and Law in Israel/Palestine, Cambridge University Press, 2014, 31.

29. Braverman, “The Tree is the Enemy Soldier,” 450.

30. Simon Schama, Landscape and Memory, Toronto: Random House of Canada, 1995, 5-6.

31. Irus Braverman, “”The Tree is the Enemy Soldier”: A Sociolegal Making of War Landscapes in the Occupied West Bank,” Law & Society Review 42, no. 3 (2008): 450.

32. Braverman, Planted Flags, 95.

33. Yael Zerubavel, “The Forest as a National Icon: Literature, Politics, and the Archeology of Memory,” Israel Studies (Bloomington, Ind.) 1, no. 1 (1996): 60.

34. Irus Braverman, “Planting the Promised Landscape: Zionism, Nature, and Resistance in Israel/Palestine.”

Natural Resources Journal 49, no. 2 (2009): 318.

35. Sheffi and First, “Land of Milk and Honey,” 203.

36. Braverman, Planted Flags, 128.

37. Gorney, “Roots of Identity, Canopy of Collision: Re-Visioning Trees as an Evolving National Symbol within the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict,” 331.

38. Saree Makdisi, Palestine Inside Out: An Everyday Occupation, 1st ed, New York: W. W. Norton & Co, 2008, 24.

39. Mourid Barghouti, I Saw Ramallah. 1st ed. New York: Anchor Books, 2003, 58.

40. Sheffi and First, 203.

41. Braverman, Planted Flags, 129.

< The Pine and the Olive > 25

Part 2: Literature Review and Methods

This project sits at three key intersections: landscape as a device of war and peace, storytelling and dialogue as an approach to peace, and reading and telling those stories with landscape design. This literature review will examine some of the bodies of work that span these fields, such as political science, planning and landscape, conflict resolution, and design.

Spatial Transformations: War + Landscape

Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture

Fionn Byrne’s research builds upon the emerging research on the relationship between landscape, well-being, and conflict. Byrne’s article “Verdant Persuasion” (2022) frames this relationship in the context of furthering military agendas through a three-stage framework: preparation for war, active combat, and postwar activities. The postwar activities stage is often the focus of related work, where landscape researchers and ecologists analyze the influence of war on the landscape and how inhabitants feel these changes.1 Byrne’s work focuses on the second stage,- active combat, and how landscape design is used as a tool during wartime to advance military goals.2 He presents Operation Enduring Freedom to illustrate how some US Military-funded projects employed landscape elements, like tree planting, to meet military goals. In other words, his analysis centres around landscape design as an active, rather than reactive, warfighting tool.3 He argues that the manipulation of landscape, be it from active combat or landscape-related intervention during wartime, has lasting impacts on the well-being of residents beyond active combat.4 He calls the use of landscape in this context ‘soft power.’

Planner and Professor Gary Fields argues that landscapes reflect the communities that inhabit them and represent the powers that govern them.5 In “Landscaping Palestine” (2010), Fields highlights the built environment’s capacity

to advance territorial agendas and maintain political control, especially in Israel and Palestine. Fields references the Israeli government’s uprooting of olive trees and how that disrupts not only Palestinian economic life but also the cultural life that maintains Palestinian’s place in the landscape.6 His discussion on the direct and indirect effects landscape or built elements have in furthering military goals parallels Byrne’s writing. While Byrne presents these concepts relating to the US Military and counterinsurgencies in Afghanistan, the notion of landscape as a soft power tactic to the conflict in Israel and Palestine is supported by Fields’ writing. Both scholars are concerned with how the landscape is affected by active conflict, control, resistance or a marker of societal wellbeing. These topics are critical in understanding the relationship between landscape, conflict, and people. This project aims to fill a gap in this scholarship regarding how landscape design can be used during an active conflict as a peacebuilding mechanism rather than as a warfighting, control, or resistance tool. It would be impossible to move forward in this project without a foundational understanding of how the landscape is used to divide, control, influence, or resist colonial and military agendas. Not only does this understanding help us grasp the historical use of landscape in war, but also how the interventions we propose may change over time both physically and socially.

Storytelling + Dialogue in a Divided Landscape

This project establishes that dialogue and storytelling are critical in studying peacebuilding and are approaches that are innately interwoven in the context of the landscape. A large body of research has investigated the effectiveness of dialogue and storytelling both in the context of Israel and Palestine and in general conflict studies. A group from UC Santa Cruz, including

28 < Literature Review & Methods >

LITERATURE REVIEW

Ella Ben Hagai, Phillip Hammack, Andrew Pilecki, and Carissa Aresta studied Israeli/ Palestinian dialogues by analyzing recorded sessions to pull out the root narratives and illuminate the tactics that led to more acceptance and progress. The article “Shifting Away from a Monolithic Narrative on Conflict” (2013) is a fantastic investigation of root narratives and power dynamics across different scales. Most importantly, their research revealed that when groups shared personal experiences and stories, they noticed an increase in acknowledgment, perspective-taking and empathy.7 Emphasizing the personal nature of the narratives we chose to tell and their power in building inter-group empathy is an especially key takeaway moving forward. As part of this study, participants partook in group-building exercises such as visiting tourist spots and playing outdoor games which likely helped increase comfortability and companionship with the participants. However, this article lacks an explicit discussion on spatial barriers to successful dialogue, as these studies took place in the United States. The article also fails to mention the quality of space that hosted the dialogue sessions and why or why not that might have contributed to the success of conversations.

Economic and Social Research

Council

Postdoctoral Fellow Silvia Hassouna argues that literature relating to dialogue and conflict resolution neglects the importance of spatial planning in contested landscapes.8 Hassouna studies storytelling in this political context, documents joint efforts for peace, and highlights creative and imagined futures. Her article “Spaces for Dialogue in a Segregated Landscape” (2016) asks imperative questions about the feasibility of spaces for dialogue and barriers to such practices, emphasizing the separation wall in Israel/ Palestine as having exacerbated these problems and hindered opportunity for dialogue. Her findings concluded that there are numerous

barriers to human interactions, such as travelling logistics, isolation, and dehumanization, and offers strategies to overcome such barriers. The previous authors’ findings set the foundation that dialogue-based approaches are indeed effective in increasing empathy in Israeli/Palestinian groups, underpinning Hassouna’s argument that more specifically stresses the capacity dialogue carries in renegotiating collective narratives. Hassouna states that this conflict is an intractable struggle of identity where recognizing the legitimacy of one side means denying the legitimacy of the other.9 Additionally, she maintains that one of the most significant barriers to peace negotiations and dialogue-based initiatives is an antinormalization drive rooted in many community members who see those who engage in such initiatives as unpatriotic or traitors.10

I heard these misconceptions in my own community and discussed these notions about competing narratives in my dialogue group. Lessening the anti-normalization drive and acknowledging each other’s narrative through dialogue-based initiatives propels us to “recognize the common sense of belonging to the land.”11 Both articles emphasize storytelling as one method that breaks through these barriers and even saw epiphanies regarding the need for nonviolent approaches to ending the conflict. Numerous other highly inspirational tales of such epiphanies and moments of reflection exist.12 Both articles examined in this section illustrate the weight of personal and collective narratives and how space creates either a barrier or an opportunity. This project echoes Hassouna’s argument that while dialogue may be an effective conflict-resolution method, space must be created to facilitate it, especially in a divided landscape. This position is best summarized in her writing:

“Space can be used as both a force for conflict when urban planning becomes the manifestation of division and as a force for peace when used to facilitate

< Literature Review & Methods > 29

contracts and dialogues in contested spaces.”13

-Silvia Hassouna

Memory and Stories in the Landscape

We have established that storytelling and dialogue are effective peacebuilding strategies that must now be translated into physical spacemaking. What does space-making mean in this context and what are the legitimate strategies for making space in such a contested landscape? Many of the methods designers employ when designing for post-war or active conflict involve commemoration or memorialization. Such strategies are exhaustively written about across numerous fields.14 However, in Topographies of Memory (2017), Instructor of Landscape Architecture and researcher Anita Bakshi challenges some approaches to commemoration, saying they are problematic, especially in contested cities, as they often seek to freeze time in place and tell sanitized versions of collective memories. Controlling collective memory through memorials or museums doesn’t often leave room for alternative meanings and is “rooted in Western and colonial understandings of heritage, which prioritize the nation state as the arbitrator of the past despite competing claims by minority groups.”15 She does, however, recognize that landscape architecture is a vehicle through which the ephemeral phenomenon of memory can be expressed16 and offers some strategies for new forms of commemoration.

The strategies outlined in the book often involve active participation, which helps participants process the dynamism of events and their perceived effects on physical places.17 This process often involves layering individual memories through map-making or sketching to create a dynamic display of collective history. These activities help the participants process the dynamism of events and their perceived effects on physical places.18 The fieldwork summarized

in this chapter illustrates the importance of establishing new connections with place and allowing community members to engage in the process: critical aspects to consider as I approach this project. In the following chapter, Bakshi discusses physical and material interventions that may more equitably highlight memory. It is evident that spaces associated with contested or traumatic memories require a thoughtful approach to narrativization and memorialization. Such approaches should involve design considerations for the body’s physical, emotional, mental, and social aspects.19 Bakshi presents a short discussion on a child survivor of the Holocaust to make the central point that these spaces may not just share the story of a collective or personal experience (in this case, the horrors of the Holocaust) but that the space may help individuals come to know and process the experience. In these cases, abstraction and ambiguous forms may be ineffective compared to designs that engage the body more wholly.20 Bakshi emphasizes the importance environments conducive to sharing and the subsequent strengthening or re-understanding of narratives.

Landscape architect, author, and Distinguished Professor Anne Whiston Spirn details design approaches to reading and writing meaning into landscapes in the chapter “A Rose is Rarely Just a Rose: Poetics of Landscape” in her 1998 book The Language of Landscape. These techniques, including emphasis, exaggeration, contrast, distortion, and metaphor, are certainly options to consider as methods in this project and have been used by world-renowned landscape architects like Martha Schwartz. In other chapters, she discusses theories relating to stories and the reading of meaning in the landscape. Whiston Spirn proposes that landscape forms, materials, and processes are innately analogical, poetic, and enveloped with meaning.21 She argues that landscape designers often fail to recognize the potential power landscapes hold to evoke meaning, both intended

30 < Literature Review & Methods >

and unintended, surface level and profound.22 However, the critical notion of landscape literacy is missing in Whiston Spirn’s book but present in Bakshi’s book. Additionally, while Bakshi positions interactive map-making and active participation as key to establishing connections to memory and place23, Whiston Spirn places the most emphasis on the designer as the key driver in creating meaning in the landscape.

Landscapes are Peacebuilding Mechanisms

It would be a shame not to introduce Professor of Political Science Annika Björkdahl briefly. Her research studies peacebuilding and space, but primarily the article “Urban Peacebuilding” (2013) offers seminal insights and arguments to consider. She frames the concept of urban peacebuilding as an attempt to transform ethnonationally contested and divided spaces to mitigate conflict, strengthen interdependencies, and weaken division.24 She contends that placebased processes are equally as crucial as peoplerelated processes in achieving self-sustaining peace.25 She and I share a similar viewpoint that research is lacking around the legitimate production of space and peacebuilding practices. I found that this article, some of her other writing, and the key works cited still lack specific methodological approaches to peacebuilding as a landscape intervention. These and other pieces of literature reaffirm my position that this conflict is, in part, a landscape problem to which a landscape solution is applicable and possible. An approach forward will entangle numerous strategies (such as those mentioned by Whiston Spirn) and considerations across fields.

< Literature Review & Methods > 31

LANDSCAPES ARE PEACEBUILDING MECHANISMS

To demonstrate that landscapes are peacebuilding mechanisms and building upon the discussion of the symbolic and cultural importance of the pine and the olive, planting strategies using the pine and the olive were rapidly iterated upon. The sites were chosen from the land use index shown in the previous section, each with a varying condition of wall construction. Strategies tested included creating shared space, deconstructing the physicality or visual dominance of the wall, creating ecologically diverse and rich spaces on both sides of the wall, or using the pine and olive as narrative and teaching tools to tell the stories of collective narratives.

32 < Literature Review & Methods >

Fig. 17. Planting scheme axo sketches, Samantha Miller.

The following set of planting schemes looked to activist groups such as Tent of Nations, Combatants for Peace, the Parents Circle Family Forum, Oasis of Peace/Neve Shalom/Wahat al-Salam, and EcoPeace, as well as Israeli and Palestinian biodiversity reports to see if we could begin healing both the landscape and these two nations simultaneously.

< Literature Review & Methods > 33

Fig. 18. Planting scheme axo sketches, Samantha Miller.

METHODS

Attitude and Approach to Design

Needless to say, this is a complex topic to tackle and a polarizing subject for many people at the individual and national levels. There are many different possible approaches, and it will take several tries before landing on one that will serve the communities well. New research on healing and psychosocial pathology highlights communities’ invaluable role in mediating conflicts, aside from relying on the institutional level.26 One of the primary attitudes necessary for this project is to suppress the white saviour complex to avoid Western ethnocentricity that may conduct oppressive post-colonial proposals that would not truly respect the cultural nuances of this region.

Throughout this project, I have look closely at my methods and approaches, and stay selfcritical. I will need to make explicit what is in my control and what is not. Power imbalances exist that make interconnected public space difficult to achieve. But, just as gardens can thrive in seemingly extreme or difficult environmental conditions, so can peace.

Shaping Public Space

Much of the literature regarding sharing space in divided places revolves around urban planning schemes.27 This body of work most often acknowledges that public space parallels the enmity and asymmetrical power dynamics within it. However, there is potential to increase instances of encounters between divided communities and break spatial and cultural barriers. In this regard, the principal starting point is to re-think what ‘space’ is and understand that it is socially and physically grounded.28 Secondly, allowing the irregular, improvisation, and messiness to exist in whatever designed space we propose is critical. A space that allows itself to evolve and change dynamically alongside the

urban context is far more complex and offers investigation and happenstance.29 While more urban planning related, Gaffikin, Mceldowney, and Sterrett (2010) present a few key considerations to shaping public space in divided cities. First, to ensure that public space should have qualities of identity and inclusivity that all citizens feel they can use and identify with. Secondly, the designer should see themselves as having a role of influence rather than power or control. Thirdly, consider the design strategies that inadvertently encourage surveillance, such as ‘overlooking’ and creating distinct edges to space and borders.30

Education: Storytelling Over Textbooks

In post-war or active-war landscapes, education is a primary practice that influences public discourse and develops individual or societal perceptions and beliefs. However, history textbooks focus on times of war and suffering, painting someone as the enemy and someone as the ally. They tell a curated story of events, choosing which perspectives are shared and which are silenced. Education is essential, especially as more and more people worldwide deny the events of the Holocaust or believe that the separation barrier is simply a security measure and nothing more. The reading and writing of history are especially challenging in a context such as Israel and Palestine where numerous viewpoints and collective narratives are disputed and contradictory. History education should prioritize acknowledging memory and long-lasting trauma to prevent continued aggression and hostility.31 This may involve teaching “acknowledgment, truth-telling, apology, repair, and democratization” and “recognize the victims of violence and repression, as well as their suffering and need for justice.”32 Israel and Palestinian co-founders of the Shared History Project, Sami Adwan and Dan Bar-On, offered a space for both sides’ narratives to be presented

34 < Literature Review & Methods >

and shared. It is the goal of the Shared History Project to bridge narratives and communities.33 While I am not proposing the creation of a new textbook, it is imperative that through the design of a proposal, physical space emerges that educates visitors on the narrative of the other. As mentioned, dialogue and space to tell stories are two way to educate. However, education is a larger theme that should be explored through landscape intervention. To do this, time must be dedicated to collecting first-hand accounts and the understanding of both side’s recollections of history. This has partially been achieved through the process of writing this proposal, but more work is to be done in collecting a database of narratives.

Conclusion

This project recognizes the emerging literature and existing body of work and methods contributing to studies on conflict and spatial relationships. Several questions regarding active conflict and creating spaces of peace still remain to be addressed because previous studies have almost exclusively focused on post-war landscapes, memorialization/commemoration of a past event, or active-war fighting. Other pieces to the puzzle concerning memory, storytelling, dialogue and narratives are disjointed in the body of literature surrounding this context. A new approach is therefore needed to pull these tenets together to share stories and bring empathy to the forefront.

< Literature Review & Methods > 35

Endnotes

1. Some of the scholarship involving the relationship between war and landscapes includes Björkdahl and Buckley-Zistel (2016), Braverman (2008), Helphand (2006), Mostafavi (2017), and Pearson (2012).

2. Fionn Byrne, “Verdant Persuasion: The Use of Landscape as a Warfighting Tool During Operation Enduring Freedom,” Journal of Architectural Education 76, no. 1 (2022), 37-38.

3. Byrne, “Verdant Persuasion,” 39.

4. Byrne, 43.

5. Gary Fields, “Landscaping Palestine: Reflections of Enclosure in a Historical Mirror,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 42, no. 1 (2010), 64.

6. Fields, “Landscaping Palestine,” 75.

7. Ella Ben Hagai, Phillip L. Hammack, Andrew Pilecki, and Carissa Aresta. “Shifting Away from a Monolithic Narrative on Conflict: Israelis, Palestinians, and Americans in Conversation,” Peace and Conflict 19, no. 3 (2013), 298.

8. Silvia Hassouna, “Spaces for Dialogue in a Segregated Landscape: A Study on the Current Joint Efforts for Peace in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict,” Conflict Resolution Quarterly, vol. 34, no. 1, 2016, 58.

9. Hassouna, “Spaces for Dialogue in a Segregated Landscape,” 59-60.

10. Hassouna, 61.

11. Hassouna, 60.

12. Such tales of epiphanies include that of Rami Elhanan and Bassam Aramin. Their stories are ever-so-poetically detailed in Apeirogon, A Novel (2020) by Colum McCann, a book that has greatly inspired this project. Additionally, similar themes are highlighted in Letters to My Palestinian Neighbour (2019) by Yossi Klein Halevi, I Saw Ramallah (2003) by Mourid Barghouti, and in the work of Peace Heroes, Just Vision, Ali Abu Awwad, and more.

13. Hassouna, 63.

14. Some written works that discuss

memorialization and commemoration strategies include Pirker, Rode and Lichtenwagner (2019), Stevens and Franck (2016), Stevens (2013), Björkdahl and Buckley-Zistel (2016), and Mohammad (2017).

15. Anita Bakshi, “Modes of Engagement” in Topographies of Memories: A New Poetics of Commemoration. Secaucus; New York: Palgrave Macmillan (2017), 213.

16. Anita Bakshi, “Introduction” in Topographies of Memories: A New Poetics of Commemoration. Secaucus; New York: Palgrave Macmillan (2017), 12.

17. Bakshi, “Modes of Engagement,” 237.

18. Bakshi, “Modes of Engagement,” .

19. Anita Bakshi, “Chapter 7: Materializing Metaphor” in Topographies of Memories: A New Poetics of Commemoration, Secaucus; New York: Palgrave Macmillan (2017), 272-275.

20. Bakshi, “Materializing Metaphor,” 281.

21. Anne Whiston Spirn, “A Rose is Rarely Just a Rose: Poetics of Landscape” in The Language of Landscape, New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press (1998), 216.

22. Whiston Spirn, “A Rose is Rarely Just a Rose: Poetics of Landscape,” 216-217.

23. Bakshi, “Modes of Engagement,” 237.

24. Annika Björkdahl, “Urban Peacebuilding,” Peacebuilding 1, no. 2 (2013): 208.

25. Björkdahl, “Urban Peacebuilding,” 211.

26. David Senesh, “Restorative Moments: From First Nations People in Canada to Conflicts in an Israeli–Palestinian Dialogue Group,” In Peacebuilding, Memory and Reconciliation, edited by Charbonneau, Bruno and Genevieve Parent, Routledge, 2012, 163.

27. The literature surrounding shared public space in divided contexts include Björkdahl (2013), Bollins (2021), Brand-Jacobsen and Frithjof (2009), Calame and Charlesworth (2011), Gaffikin, Mceldowney, and Sterrett (2010), and more.

28. Frank Gaffikin, Malachy Mceldowney, and Ken Sterrett, “Creating Shared Public Space

36 < Literature Review & Methods >

in the Contested City: The Role of Urban Design,” Journal of Urban Design 15, no. 4 (2010): 497.

29. Gaffikin, Mceldowney, and Sterrett, “Creating Shared Public Space in the Contested City,” 498.

30. Gaffikin, Mceldowney, and Sterrett, 499-500.

31. Karina V. Korostelina, “Can history heal trauma? The role of history education in reconciliation processes,” in Peacebuilding, Memory and Reconciliation, edited by Charbonneau, Bruno and Genevieve Parent, Routledge, 2012, 196.

32. Korostelina, “Can history heal trauma?,” 197.

33. Korostelina, 202.

< Literature Review & Methods > 37

Part 3: Precedent Studies

PRECEDENT STUDIES

Introduction