Autor przypisuje elitom kluczowe, czy wręcz rozstrzygające znaczenie w tworzeniu demokratycznych instytucji i konsolidacji reguł funkcjonowania demokratycznych mechanizmów. Zwraca uwagę, że do udanej demokratyzacji przyczyniła się nie tyle wymiana elit (w niektórych państwach miała ona bardzo ograniczony charakter), ile przyjęcie przez nie zasady samoograniczenia, akceptacja pluralizmu politycznego i zasady zmiany władzy w wyniku w miarę uczciwej konkurencji wyborczej. Tam gdzie elitom takiej „chęci do demokratyzacji” zabrakło, a więc przede wszystkim w państwach postsowieckich, doszło do instytucjonalizacji rządów autorytarnych. Z drugiej strony wskazuje na szereg słabości właściwych elitom politycznych „nowych demokracji”, takich jak: oportunizm, uwikłanie w nieformalne układy i powiązania, brak profesjonalizmu i podatność na to co nazywa „popularnymi ideologiami”. Najgroźniejszy mankament „nowych demokracji” widzi jednak gdzie indziej – w niestabilności systemu partyjnego. Dr Witold Rodkiewicz Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich im. Marka Karpia (OSW) Studium Europy Wschodniej, Uniwersytet Warszawski

ISBN 978-83-61325-85-7

LAT

Jubileusz

Studium

Europy Wschodniej

9 788361 325857

Uniwersytet Warszawski

1990-2020

STUDIUM EUROPY WSCHODNIEJ

U N I W E R S Y T E T WA R S Z AW S K I

d

B i b l i o t h e c a E u r o pa e O r i e n t a l i s

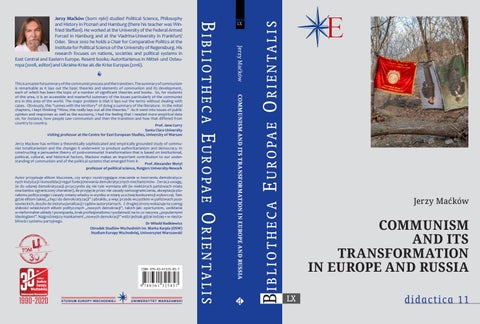

Jerzy Mackow has written a theoretically sophisticated and empirically grounded study of communist totalitarianism and the changes it underwent to produce authoritarianism and democracy. In constructing a persuasive theory of post-communist transformation that is based on institutional, political, cultural, and historical factors, Mackow makes an important contribution to our understanding of communism and of the political systems that emerged from it. Prof. Alexander Motyl professor of political science, Rutgers University-Newark

LX

COMMUNISM AND ITS TRANSFORMATION IN EUROPE AND RUSSIA

This is a masterful summary of the communist process and the transition. The summary of communism is remarkable as it lays out the basic theories and elements of communism and its development, each of which has been the topic of a number of significant theories and books. So, for students of this area, it is an accessible and masterful summary of the issues particularly of the communist era in this area of the world. The major problem is that it lays out the terms without dealing with cases. Obviously, this “comes with the territory” of doing a summary of the literature. In the initial chapters, I kept thinking “Wow, this really lays out all the theories.” As it went into issues of public opinion and responses as well as the economy, I had the feeling that I needed more empirical data on, for instance, how people saw communism and then the transition and how that differed from country to country. Prof. Jane Curry Santa Clara University visiting professor at the Centre for East European Studies, University of Warsaw

BEO

Jerzy Maćków

•

B i b l i o t h e c a E u r o pa e O r i e n t a l i s

Jerzy Maćków (born 1961) studied Political Science, Philosophy and History in Poznań and Hamburg (there his teacher was Winfried Steffani). He worked at the University of the Federal Armed Forced in Hamburg and at the Viadrina-University in Frankfurt/ Oder. Since 2002 he holds a Chair for Comparative Politics at the Institute for Political Science of the University of Regensburg. His research focuses on nations, societies and political systems in East Central and Eastern Europe. Resent books: Autoritarismus in Mittel- und Osteuropa (2008, editor) and Ukraine-Krise als die Krise Europas (2016).

Jerzy Maćków

COMMUNISM AND ITS TRANSFORMATION IN EUROPE AND RUSSIA LX

d id a ctica 11