Basketland

Trieste and the USA

Player Idol Playground

Basketland

Trieste and the USA

Player Idol Playground

Nei primi mesi di quest’anno, alla vigilia dell’ingresso della proprietà americana nella Pallacanestro Trieste, ci siamo ritrovati intorno ad un tavolo a parlare del rapporto di Trieste con il basket –e con lo sport in generale– e di quante eccellenze fosse stata in grado di esprimere una città con una provincia così piccola. Durante la conversazione, esempi e storie hanno affollato il tavolo senza sosta, lasciandoci sempre più stupiti di quanto fosse speciale la nostra città e quanto fosse importante ricordarlo sia a coloro che, come noi, vivono immersi nella quotidianità di Trieste, sia a chi ancora non ha avuto la fortuna di conoscerla. Trieste è davvero un luogo eccezionale sotto molti punti di vista, e noi abbiamo scelto di concentrarci sul suo lato sportivo. Il basket rappresenta l’orgoglio di una cultura sportiva senza rivali, scorre nel sangue dei triestini, unendo la gente in una comunità coesa e grintosa. Trieste Basket, che sostiene questo progetto narrativo in collaborazione con IES, è nata come simbolo dell’identità locale e come collante tra la prima squadra cittadina, la Pallacanestro Trieste, ed il tessuto imprenditoriale locale. Con questo numero speciale di IES, abbiamo voluto condividere la nostra passione con la città ed oltre i confini locali, per raccontare come in un territorio così piccolo possano esistere così tante storie straordinarie.

Lorenzo Pacorini Presidente Trieste BasketEarly this year, as the acquisition of Pallacanestro Trieste by American investment group CSG was being finalised, we set together to discuss the bond between the city of Trieste and basketball – and sports in general – focusing on the sheer number of top athletes originating from such a geographically limited area. Countless examples and stories, like overflowing rivers, poured into our conversation, as we realised how incredibly unique Trieste is, and how her uniqueness deserves to be celebrated, both among those who, like us, are lucky enough to live here – and may need to be reminded thereof – and among those who have yet to experience our city.

Of all the numerous reasons why Trieste is truly exceptional, we chose to focus here on sport-related aspects.

Basketball is the flagship of the city’s unparalleled sport vocation, it runs in the veins of her citizens and brings them together in a proud, closelyknit, and gutsy community.

Trieste Basket, partnering with IES in this story-telling project, was born as a symbol of local identity, to act as the glue keeping together Trieste’s first basketball team Pallacanestro Trieste and the city’s business fabric.

This special edition of IES is our way of sharing our passion with locals and visitors alike, by presenting an extraordinary collection of amazing stories, all originating from this little big territory.

Trieste Basket nasce dall’impegno di un gruppo di imprenditori appassionati, che credono nei valori di questo sport e nelle potenzialità del territorio. Imprese, liberi professionisti, attività commerciali e realtà consortili si uniscono per essere il secondo socio del club, con un consigliere all’interno del CdA. Spirito sportivo, etica, rispetto, impegno ed organizzazione: sono questi i punti di riferimento di un gruppo che vuole fare squadra al servizio della Pallacanestro Trieste e che negli anni è cresciuto sino a raggiungere gli oltre 40 marchi che oggi sono rappresentati.

Chiari gli obiettivi che Trieste Basket si prefigge ed insegue: sostenere questo sport in città con azioni concrete; rilanciare il tessuto produttivo del territorio grazie a nuove collaborazioni e far crescere l’entusiasmo della comunità attorno alla squadra con attività coinvolgenti.

Previste convenzioni sia in campo che fuori, con appuntamenti riservati, scontistica sulle sponsorizzazioni alla squadra, partite e incontri conviviali, oltre ad offerte esclusive per il B-to-B con altre realtà legate al basket.

Entra allora in Trieste Basket. Gioca a tutto campo, metti insieme passione e ragione!

Trieste Basket owes its existence to the determination of a group of entrepreneurs, who firmly believe in this sport and the potential of this territory. Businesses, freelancers, firms, and consortium companies came together to become the club’s second shareholder, with one member in the Board.

Sportsmanship, ethics, respect, commitment, and organisation: these are the guiding principles leading this group that decided to come together as a team to support Pallacanestro Trieste, and today counts over 40 brand names within its representation.

Trieste Basket is actively pursuing a set of clear goals: providing material support for this sport in the city; giving new momentum to the local production industry by enhancing its underlying cooperation network; and promoting the local community’s involvement in the club’s activities through dedicated events.

Future actions include new agreements – both in- and outside the court, with premium-only events, sponsorship discounts, exhibition games, and gettogethers, as well as basketball B2B-exclusive offers.

Join Trieste Basket. Merge passion and reason, and become your own game maker!

90%

10% Trieste Basket

Board of Directors

CSGI Cotogna Sports Group Italia Gianni De Palo Consigliere /director Andrea Monticolo Consigliere /director Daniele Muha Consigliere /director Lorenzo Pacorini Presidente /President Antonio Rosanò Consigliere /director Silvio Stafuzza Consigliere /director Franco Stock Consigliere /director Consiglio direttivo Trieste BasketLaforza di un gruppo per la Pallacanestro Trieste

Pallacanestro Trieste and the power of teamwork

È Trieste che si è innamorata della pallacanestro o è stato questo gioco a strizzare l’occhio alla città? Forse è un quesito di poca importanza. Sta di fatto che tra un pallone da basket e la nostra gente molto tempo fa è scoccata una scintilla, diventata poi attrazione, passione, infine amore. Come chiamarlo, altrimenti?

E allora, questo numero speciale che IES dedica al basket, altro non può essere che “un atto d’amore”. Perché a Trieste, nonostante il calcio con le sue leggende in maglia alabardata, nonostante la calamita di un mare che attrae migliaia di cittadini-naviganti, nonostante la viscerale passione per tutto quanto è corsa, movimento, sudore, aria aperta e vento tra i capelli, che negli anni l’hanno fatta diventare la “città più sportiva d’Italia”, nonostante tutto ciò, in fondo al cuore di molti, l’arancia ed il canestro conservano un posto speciale.

Ecco il perché di queste pagine, ricche di immagini, storie, racconti ed aneddoti, che testimoniano il profondo legame di quel gioco nato per caso in una palestra del nord America e diventato uno degli sport più praticati del mondo. Ce lo raccontano, tutti assieme, i campioni di ieri e di oggi, sfogliando l’album dei ricordi e guardando al futuro, attraverso le testimonianze raccolte da amici e colleghi, che al basket hanno donato gran parte della loro vita.

Che il viaggio abbia inizio! Tra alti e bassi, trionfi e sconfitte, gioie e delusioni, pianti ed abbracci. Sullo sfondo, l’innegabile feeling con la patria di questo sport, quegli Stati Uniti d’America che hanno segnato la storia di questa città, lasciando un’impronta calpestata poi da migliaia di “basket-ball shoes”. Dal primo parquet della città, realizzato dagli americani all’Idroscalo, ai play-ground di casa nostra (qui si chiamano Ricreatori Comunali), che sfornano ancor oggi i campioni di domani; dalla costola triestina che ha fatto nascere la grande Milano cestistica di ieri e di oggi, fino alla squadra triestina attuale che –incredibilmente– è di nuovo legata al Paese che questo sport lo ha inventato.

Il nostro magazine di accoglienza turistica, una volta di più è pronto a vestire i panni del cicerone, per farvi stavolta da guida tra i segreti e le bellezze di Trieste e del suo amore per il basket.

di /by Giovanni MarziniWhether it was Trieste that first fell in love with basketball, or basketball that started flirting with the city, is of little importance. What really matters is that their initial spark soon turned into attraction, then passion, and, finally, love. There is no better word to describe it. This is why this special issue of IES is an “act of love” and a dedication to basketball. True: Trieste is fond of her legends wearing the city’s halberd on the football field; her sea and seafarers; her outdoors, especially the city’s jogging itineraries, and the feeling of the wind running its fingers through one’s hair, each step echoing one’s heartbeat. Indeed, the sheer number of local joggers and running enthusiasts has earned Trieste the title of “Italy’s city of sports”. And yet, despite all the above, many a heart in Trieste beat only for the rock and the hoops.

A special issue of images, tales, history, and anecdotes, illustrating the bond between Trieste and basketball – an indoor game invented by a Massachussettes PE professor to keep his gym class active on a rainy day, that soon evolved into one of the world’s most popular sports. Guided by the voices of past and present basketball champions, IES readers can revisit the glories of the past and cast a glance into the future, thanks to the invaluable contribution of friends and colleagues, who have devoted a significant part of their lives to basketball.

Let the journey begin! With its highs and lows, triumphs and defeats, celebrations and disappointments, laughs and tears, against the backdrop of basketball’s home, the United States of America, and the impression they left on Trieste – in this case, a footprint outlining the herringbone pattern of a basketball shoe.

From the first hardwood-floored court built by the Americans at the Idroscalo (lit. seaplane base) to the city’s “playgrounds”, which here are called Ricreatori Comunali (lit. municipal recreation centres), still churning out some of Italy’s most promising rookies; from the golden age of Trieste’s basketball, feeding the A-League teams of Milan, to today’s home team and its renewed American connection.

Once again, our magazine welcomes Trieste’s visitors, ready to guide them through the city’s secret treasures and love for basketball.

direttore responsabile

Giovanni Marzini

coordinamento

Rino Lombardi

segreteria di redazione

Fabiana Parenzan redazione@prandicom.it

Via Cesare Battisti 1, 34125 Trieste

hanno collaborato

Severino Baf, Raffaele Baldini, Federico Bolle, Paolo Condò, Roberto Degrassi, Rino Lombardi, Carolina Meucci, Guido Roberti, Marco Stabile, Franco Stibiel, Sergio Tavčar

traduzioni

Rita Pecorari Novak, Eugenia Dal Fovo progetto grafico e impaginazione

Matteo Bartoli, Elisa Dudine – Basiq

stampa

Riccigraf S.a.s.

foto di copertina

Linda Cravagna

fotografie

Giovanni Aiello, Demis Albertacci, Camilla Bach, Carlo Borlenghi, Linda Cravagna, Simone Ferraro, Stefano Gattini, Paolo Giovannini, Andrea Pisapia, Fabio Ramani, Archivio Pallacanestro Trieste, Archivio Adobe Stock

I“In Italia le città del basket sono quattro: Milano, Varese, Bologna e Trieste!” È la risposta del nuovo general manager della Pallacanestro Trieste alla domanda che IES gli ha fatto sul perché abbia accettato l’offerta del gruppo Cotogna. Può bastare, perché nello stile asciutto di questo sessantenne avvocato di New York aver inserito la nostra città nel ristretto rango delle basket-city italiane giustifica la sua scelta.

“Non ho mai pensato a Trieste come ad una piazza da serie A/2. Ok, adesso siamo qui, ma la mia valutazione è diversa. Per la sua storia, le sue tradizioni e la passione che gli abitanti di questa città da sempre hanno riservato alla pallacanestro, Trieste merita il palcoscenico più importante. E lo conquisteremo assieme”!

di /by Giovanni MarziniUn passato da buon giocatore, ad un passo dal vestire la maglia di un team bolognese sul finire degli anni 80 come oriundo e poi una carriera fuori dal campo tra coach nel college, scout e dirigente con diverse franchigie NBA (i Knicks di New York restano la sua squadra del cuore) sino all’esperienza italiana nella ricostruzione di Varese al fianco del presidente-giocatore Luis Scola. Una stagione soltanto, sufficiente per farlo nominare dalla LBA come “manager dell’anno”.

“L’arrivo nella vostra città è però anche dovuto a Richard de Meo e agli altri componenti di Cotogna Group, che conoscevo da tempo. Nutro grande stima per queste persone: quelli che escono dalla Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, sono manager di tutto rispetto. E quando mi hanno illustrato il loro progetto per Trieste, non ho avuto alcun dubbio nell’accettare l’offerta. Mi stimola poter costruire qualcosa che possa durare nel tempo. Per Trieste non vogliamo solo la risalita nel basket di vertice, ma disegnare veramente una società che possa ambire nell’arco di qualche anno ad avere un suo spazio a livello europeo. Ne serviranno 5, 6 o 7? Può darsi, ma intanto iniziamo a lavorare bene da subito”.

Avete iniziato ripartendo da uno stretto legame con la realtà del territorio. Tre triestini doc nel roster non sono poca cosa nel basket di oggi…

“A Bossi, Deangeli e Ruzzier aggiungici pure Daniele Cavaliero, che lavorerà al mio fianco. Credo molto nelle persone cresciute anche sportivamente nella città della quale indossano la maglia. Posso immaginare le domande, anche i dubbi della gente, sulla proprietà americana della società. Io però ragiono così: i veri proprietari sono i triestini. Sono i nostri tifosi, sono i nostri abbonati, sono quei settemila che spero torneranno prestissimo a riempire il nostro palazzo. Che pur non essendo il Madison di New York resta una delle arene più belle d’Italia. Vengo a Trieste con mia moglie (italiana, avvocato pure lei!) e mio figlio

di quasi due anni. Trovo la città bellissima e ritengo, al pari di quanto pensano e credono gli amici di CSGI, che nonostante il fatto non sia una metropoli, ha tutte le caratteristiche per essere più che mai una delle capitali italiane del basket. Per la sua collocazione geografica, la sua tradizione, il suo storico legame con l’impronta americana, ma anche la sua vicinanza con quel basket dell’est così importante per questo sport. Abbiamo le idee molto chiare per il futuro e mi sento di affermare che vogliamo lasciare un’impronta sulla storia di questo club”.

I progetti ed i traguardi prefissati dalla nuova proprietà quando si è presentata in primavera alla città, cozzano però con una retrocessione a dir poco traumatica…

“Certo, sono campionati diversi. In A/1 una squadra americana gioca con al massimo tre o quattro italiani. Quest’anno la nostra squadra italiana giocherà con due americani. Fa una grande differenza. Ma saremo un gruppo coeso, dove tutti si sentiranno responsabili e ugualmente protagonisti. Sono certo che i nostri tifosi capiranno la nostra filosofia. Così come la nuova proprietà ha perfettamente capito in quale realtà si è calata”.

1976 - 1981: Hurlingham

1981 - 1982: Oece

1982 - 1984: Bic

1984 - 1994: Stefanel

1994 - 1996: Illycaffè

1996 - 1998: Genertel

1998 - 1999: Lineltex

1999 - 2001: Telit

2001 - 2002: Coop Nordest

2002 - 2003: Acegas Aps

2003 - 2004: Coop Nordest

2005 - 2013: Acegas Aps

2016 - 2019: Alma

2019 - 2022: Allianz Timeline degli allenatori Coaching Timeline

1976 - 1977: Nicola Porcelli

1977 - 1982:

Gianfranco Lombardi

1982 - 1983: Rudy D’Amico

1983 - 1985: Mario De Sisti

1985 - 1986: Santi Puglisi

1986 - 1994: Bogdan Tanjević

1994 - 1995: Virginio Bernardi

1996 - 1997: Furio Steffè

1999 - 2001: Luca Banchi

2001 - 2004: Cesare Pancotto

2004 - 2007: Furio Steffè

2007 - 2008: Piero Pasini

2008 - 2010:

Massimo Bernardi

2010 - 2021:

Eugenio Dalmasson

2021 - 2022: Franco Ciani

2022 - 2023: Marco Legovich

2023: Jamion Christian

“Mi stimola poter costruire qualcosa che possa durare nel tempo.”

“I find long-term projects inspiring.”

There are four basketball cities in Italy: Milan, Varese, Bologna, and Trieste!” This was the answer that Pallacanestro Trieste’s new general manager Michael Arcieri gave IES, when we asked him what convinced him to accept Cotogna Sports Group’s offer. New York born, sixty years old, sports law professional, Arcieri says it all simply by mentioning Trieste as one of Italy’s cities of basketball.

“I do not believe that Trieste belongs in the A2 League. This is just where we are at, for now, but I have a different goal in mind. The love for basketball runs deep in Trieste’s history, tradition, and fan base, which is why PallTrieste deserves a place in the Italian top league. And we will get there together!”

Arcieri started off as basketball player, and almost ended up playing for an Italian team at the end of the 1980s. He then kept following his passion from the bleachers, first as varsity coach, and later as scout and director of basketball operations for various NBA teams (first and foremost his home team, the New York Knicks). He eventually landed in Italy, where he worked side by side with former power forward and current chief executive officer Luis Scola to rebuild Pallacanestro Varese. In one single season his exceptional contribution earned him the Lega Basket Serie A (LBA) award of “Best Executive of the Year”.

“I am now in Trieste thanks to Richard de Meo and the rest of the Cotogna Group. We go a long way back and I highly respect their work: MBA students of the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania are truly excellent business managers. When I was offered this job and learned about their project for Pallacanestro Trieste, I accepted without hesitation”.

“I find long-term projects inspiring.

Our vision for Trieste is not limited to game performance: we aim at designing a club that can keep growing over the next few years, and whose scope has the potential of reaching a truly European dimension. It may take time – five, six, seven years, perhaps? No matter: the important thing is that we start preparing for it now”.

One of the first moves of PallTrieste’s new ownership was an explicit commitment to the city: three Trieste-born players in the team roster are quite a statement in this day and age…

“Not only Bossi, Deangeli, and Ruzzier on the court, but also Daniele Cavaliero, who will work by my side. I never underestimate the value of having players wearing the jersey of the city they were born and bred in. It is easy to anticipate questions and doubts locals may raise concerning an American ownership. This is how I see it: ownership of Pallacanestro Trieste ultimately belongs to Triestini, our fans and season ticket holders, those 7,000 people that, hopefully, will soon fill Trieste’s arena again this year – true, it is no New York Madison Square Garden, yet Trieste’s Allianz Dome is one of the most beautiful arenas in Italy”.

“I am moving to Trieste together with my wife (who is Italian, and a lawyer like me) and my two-year-old son. Such a beautiful city. And I must agree with my friends at CGSI: Trieste has no large metropolitan area, and yet the city has everything it takes to become one of Italy’s basketball capitals. Witness the city’s location and tradition, her deeply rooted ties with the USA, as well as her privileged connection with Eastern European basketball. Our course is charted, and I am confident that our work will be remembered in the club’s history”.

The new ownership’s ambitious plans and goals were made public last spring, just in time for the club’s traumatizing relegation…

“Every championship is different. A-league teams in the US have a maximum of three or four Italian players in their roster. This year two American players will wear Trieste’s jersey. A significant change. But we are still a tightknit team, where everyone will bear equal responsibility and feel equally important. I have no doubt that our fans will understand and appreciate our vision, the way CSGI understands and appreciates the close relation between the team and their city”.

Board Richard de Meo Presidente /President

Fitzann R. Reid

Vice Presidente /Vice president

Mario Ghiacci

Vice Presidente /Vice president

Connor Barwin

Componente CDA /Member of the Board of Directors

Andrea Bochicchio

Componente CDA, rappresentante di Trieste Basket /Member of the Board of Directors, representative of Trieste Basket

Staff tecnico

Jamion Christian Allenatore /Coach

Francesco Nanni Assistente /Assistant coach

Marco Carretto Assistente/Assistant coach

Roster

Michele Ruzzier

Playmaker

Stefano Bossi

Playmaker

Eli Brooks Guardia /Shooting Guard

Ariel Filloy

Guardia /Shooting Guard

Lodovico Deangeli

Guardia-Ala /Swingman

Luca Campogrande

Guardia-Ala /Swingman

Giancarlo Ferrero

Ala /Forward

Justin Reyes

Ala /Forward

Francesco Candussi

Ala-Centro /Forward-center

Giovanni Vildera Centro /Center

di /by Paolo Condò

di /by Paolo Condò

Noi triestini veniamo abituati fin da piccoli a guardare verso l’alto. Il colle di San Giusto. Le Scale dei Giganti. I palazzi sulle Rive. Il Santuario di Monte Grisa. Volgi gli occhi al cielo, ragazzo, tutto ciò che Trieste custodisce di bello per te è verticale, come ben sanno i radi ciclisti alle prese con i faticosi saliscendi cittadini: Salita Promontorio, Erta Sant’Anna, Scala Santa. Ricordo un amico entusiasta della sua nuova casa, in un quartiere satellite chiamato Altura. Non credo occorra altro per spiegare la nostra predisposizione al basket. Se sei abituato a guardare in alto, il primo oggetto che vedi in un centro sportivo è il canestro. Voglio dire: una porta di calcio è alla tua altezza, un campo di tennis ti pare in salita soltanto se giochi contro uno (tanto) più forte, la prima cosa che ti insegnano nella gita scolastica sulla neve è scendere con gli sci, quando ci sono poche navi in porto e il fondale dei Topolini è pulito, ti immergi. Nel basket balzi, ti elevi, ascendi, fin dalla palla a due che premia chi salta un centimetro più in alto dell’avversario. E il destino del triestino è innalzarsi, gli amici mi raccontano addirittura di un’ovovia per salire in Carso, la prossima volta vengo con i Moon Boot; che poi la Luna è proprio lì –bella in alto, luminosa– non ha il canestro incorporato come Saturno ma assomiglia a una palla, e gli spicchi ce li possiamo disegnare sopra. Guarda in alto, triestino. E mentre gli altri attaccano il chiodo, tu attacca il ferro.

Triestini are quite used to point their gaze upwards. It is something we pick up as children. The hill of San Giusto; the Staircase of the Giants; the tall seafront facades overlooking the Rive; the Temple of Monte Grisa. Look up, child, for Trieste offers her most precious treasures to those who are not afraid to climb. The cyclists pushing their way up the city’s steep slopes know it is true: Salita Promontorio, Erta Sant’Anna, Scala Santa. I distinctly remember the joy in the eyes of a friend of mine, who had just moved to a suburb area called Altura (lit. high ground). No wonder, therefore, that the city’s youth are naturally predisposed to basketball. If you are used to look upwards, the first thing you will see in a sports court is the hoop. What I mean to say is: a football goal is no taller than person; a tennis court only feels like an upwards incline when you are playing against a formidable adversary; when you are learning to ski, the first thing you are told is to keep your eyes on the slope. As for the sea, when the ships are off the coast and the seabed in front of the Topolini is clearly visible, you just dive in. Basketball is all about vertical jumps: the very start of a game is called jump ball, as players fight for possession outleaping each other. I am even told that Trieste will soon have its own cable car to travel from the city centre to the Karst Plateau – next time I visit, I will be wearing my Moon Boots. After all, the Moon looks so close from here, shining beautiful and bright: true, unlike Saturn, the Moon has no incorporated ring. Still, it may look like a basketball, just try to imagine the black ribs crossing its surface. Look up, Triestino. And while the world buckets along, you focus on getting those buckets.

La casa del basket triestino, dove abitano le grandi emozioni

The home of Trieste’s basketball, the place of great emotions

Quale miglior metafora per rappresentare una storia: il PalaTrieste “Cesare Rubini” è la casa del basket triestino, quelle mura che accorpano nel cemento una radicata passione fatta di cadute, risalite, delusioni e gioie immense. Iniziato nel 1994, concluso nel 1999, cinque lunghi anni di cantiere che portano a compimento quello che doveva essere il teatro per importanti successi nazionali ed internazionali sotto l’egida Stefanel. “Le cose si ottengono quando non si desiderano più” diceva Cesare Pavese, anche se i triestini hanno liberato l’Araba Fenice dalle ceneri trasformando il PalaTrieste nel simbolo di una rinascita, partita dal basso. Nel pieno stile di una città di confine, nell’incrocio di razze e culture in cui si è figli di tutti e di nessuno, l’arena nel corso del tempo ha mutato il nome, da PalaRubini (nel 2011) in onore del più grande atleta che la terra di Svevo ha dato (Cesare Rubini ndr.) al pirotecnico periodo Alma fra serie A2 e massima serie (nel 2016), dando il via al più classico abbinamento dell’era moderna con marchi di un certo calibro, sfociato nel recente abbinamento con il colosso assicurativo Allianz. Un’arena a “ferro di cavallo”, con una meravigliosa

copertura a cupola in legno lamellare da 6.943 posti a sedere, progetto nato per dare una multidimensionalità alla struttura, per rendere flessibile l’organizzazione di un evento sportivo come di un concerto o di un qualsiasi spettacolo; ambizioso e lungimirante intento che però ha visto il preponderante e pieno vissuto fra due canestri, forte della concessione dell’arena dal Comune alla Pallacanestro Trieste. Tanti “pienoni” in quasi 25 anni di gestione, non più il selvaggio ammassarsi dietro le porte del vecchio amato Chiarbola ore prima dei match che contavano, ma un educato pellegrinaggio alla “Mecca” del basket triestino. Nei playoff di serie A2 il PalaTrieste è diventato addirittura troppo stretto per la tracimante passione locale, con richieste per 10 mila biglietti almeno. Stesso afflato caldo della curva disassata di Chiarbola propagato dalla Curva Nord lungo gli “anelli” della nuova arena, campioni applauditi per l’ultima volta come Conrad McRae, altri rimasti nel cuore della gente come Ivo Maric, o espressioni di una identità forte cittadina come Pecile, Cavaliero, Coronica, Deangeli, Ruzzier, Bossi. Istantanee che meriterebbero un posto d’onore all’interno del cuore pulsante alabardato, magari lungo quei corridoi ingrigiti e freddi che distribuiscono il flusso al suo interno; il “museo del basket” avrebbe un luogo, il più adatto per elevare il senso di appartenenza, il più simbolico a sostenere le strutture portanti di una storia in continua evoluzione. Potrebbe coincidere con la volontà della nuova proprietà americana di proiettarsi al futuro, un restyling del PalaTrieste a tutto tondo, in senso tecnologico, avveniristico col principio chiave che governa lo sport professionistico negli States, cioè uno spettacolo degno di essere vissuto; siamo alla confluenza di due correnti opposte, quella fredda del confezionamento di un prodotto e quella calda del pathos latino imprescindibile, due mari che si abbracciano in nome della Pallacanestro Trieste; “se la corrente ti sta portando dove vuoi andare, non discutere” e vivi l’emozione cestistica al tuo massimo.

“Nei playoff di serie A2 è diventato addirittura troppo stretto, con richieste per 10 mila biglietti almeno.”

“During the A2 League playoffs PalaTrieste was sold out, with seat demands reaching 10,000 units.”

No other place represents this story of passion quite like PalaTrieste “Cesare Rubini”: the home of Trieste’s basketball, this concrete arena has witnessed falls and comebacks, bitter disappointment and wild joy. Built between 1994 and 1999, the Dome, also known as PalaSport, was meant to become a national and international stage for Pallacanestro Trieste during Stefanel’s sponsorship. As Italian poet Cesare Pavese used to say, “You only get what you no longer crave” –and yet, like a phoenix rising from its own ashes, Triestini were able to turn their PalaSport into a symbol of rebirth. Perhaps unsurprisingly, considering the city’s position at the crossroad of multiple peoples and cultures, the Dome was never particular about its denominations: officially known as PalaRubini in 2011, after basketball hall-of-famer Cesare Rubini (possibly the greatest Trieste-born athlete of all times), it was renamed Alma Arena in 2016, as the team moved (back) up to the top league. This was the first time the arena was given the name of the team’s current sponsor, which is now insurance and financial services giant Allianz. The horseshoe design of the arena is complemented by the beautiful dome structure of bent laminated wood and has a capacity of 6,943 seats. It was designed to be flexible, able to provide a multi-dimensional space that could host a wide range of events, from indoor sporting matches to concerts and shows: an ambitious and visionary project – perhaps a little too ambitious, since, so far, the Dome has hosted mainly basketball games, especially after its concession to Pallacanestro Trieste. The large crowd of basketball fans have never missed a match in the past 25 years – having elected this perfect accommodation the new Mecca of Trieste’s basketball, after the years of endless queues outside the old Chiarbola arena hours before each game. During the A2 League playoffs the Dome was sold out, with seat demand reaching 10,000 units. Triestini brought to the rings of the Dome the

same enthusiasm that used to run hot through the tilted stand of Curva Nord of Chiarbola arena − cheering heroes like Conrad McRae one last time; remembering beloved champions such as Ivo Maric; or celebrating the city’s pride kept high by players like Pecile, Cavaliero, Coronica, Deangeli, Ruzzier, and Bossi. Snapshots deserving a place of honour in the beating heart of the halberd city, perhaps displayed along the now bare and cold concrete walls of the arena access tunnels – a basketball museum, in the place that best expresses Trieste’s sense of belonging, while also representing a story that is still being written. An idea that may appeal to the current American owners: their forward-looking restyling plan, especially in terms of technology, follows the principles of American professional sports, which is first and foremost a show worth watching. Two opposite trends are about to join: the cold, calculating job of product selling, and the warm, passionate force of Italian culture. Two seas about to merge into one, in the name of Pallacanestro Trieste. “If the stream is taking you where you want to go, do not fight it”, simply live the hoops frenzy to its fullest.

Un’arena a “ferro di cavallo”, con una meravigliosa copertura a cupola in legno lamellare.

The horseshoe design of the arena is complemented by the beautiful dome structure of bent laminated wood.P. Giovannini

La pallacanestro triestina in versione americana

Italian basketball the American way

La sensazione era che quel ragazzino smilzo avesse celato l’immensità dei sogni nelle scarpe, enormi, ma ideali per seguire orme e prodezze di Joe “Jellybean”, considerato il precursore di Magic Johnson, dopo essersi permesso una imperiosa schiacciata in faccia a Kareem Abdul Jabbar. Una manna per il nostro basket e per il figlioletto. E pazienza se per assistere da vicino alle esibizioni del papà girovago dovesse armarsi di stracci per pulire il parquet. Niente male la contropartita: una bicicletta di colore rosso. Ma l’imberbe prodigio, a Reggio Emilia, ennesima tappa della famiglia Bryant, ammirava stupito anche un giovane dal fisico statuario e si offriva di portargli orgogliosamente il borsone alla fine dell’allenamento. Che strana coppia, il futuro rettile nero imprendibile dei Lakers, ovvero il “Black Mamba”, e il “mulo” di Trieste, Graziano Cavazzon, cresciuto alla Ginnastica Triestina. All’apice della fama, quando i cronisti lo stuzzicavano chiedendo se il suo egoismo in campo fosse imputabile ai trascorsi nel bel paese, Kobe ribatteva imperturbabile: “A parte la mia notevole elevazione, il resto lo devo all’Italia”.

Te la do io l’America: che sia la replica di un vecchio sketch, l’invito a leggere il libro di ricette di Joe Bastianich, una minaccia, o una promessa? Più semplicemente, una lezione pratica. Il diciottenne Giulio Iellini guarda e impara. Non c’è tempo per oziare con l’ex studente modello di Princeton, che si perfeziona a Oxford e mette a

“A parte la mia notevole elevazione, il resto lo devo all’Italia.”

Kobe Bryant

“Aside from my considerable vertical jump, I owe everything else to Italy.”

Kobe Bryant

disposizione di Milano la sua classe cristallina. Va per vetrine, senza essere, però, un turista per caso. Infatti, osserva, immobile, gli oggetti, allo scopo di affinare la visuale periferica. Nemmeno l’1 aprile 1966, giorno della storica sorpresa-impresa, sembra interessato alle bellezze di Bologna. Il mattino che precede la sfida fra Simmenthal e Slavia Praga convince l’allibito custode ad aprire il palasport e, scalzo, si esercita ai tiri liberi. Rimane per nulla soddisfatto, poiché ne ha infilati “solo” 88 su 100. Capitan Gianfranco Pieri (alle Olimpiadi di Roma aveva lasciato di stucco illustri personaggi come Jerry West, Oscar Robertson e Jerry Lucas), l’unico a indossare le mitiche scarpette rosse, in serata alzerà la prima Coppa dei Campioni. Bradley diventerà una stella dei Knicks di New York vincendo

due anelli nell’NBA (i compagni, cattivelli, lo chiameranno “Dollar Bill”, per il braccino corto e non per la mano fatata) e da senatore di lungo corso tenterà, senza successo, la scalata alla Casa Bianca, nonostante l’appoggio di un certo Michael Jordan.

C’è, però, chi è capace di trovare l’America in Italia. Nella Trieste senza pace e identità, il Governo Militare Alleato aveva “prestato” due yankee di non eccelsa levatura, Robert Evans e John Philips, rimpiazzati dal talentuoso John Mascioni, architetto con l’obiettivo di ottenere la terza laurea, traguardo che gli avrebbe garantito l’assegnazione gratuita di un appartamento negli States.

Ironia della (buona) sorte è che la Milano del domani viene abbozzata in… “California”. Che, poi, altro non è che un angolino dello stabilimento balneare “Ausonia”, dove Adolfo Bogoncelli, folgorato dalla beata gioventù giuliana, cattura Cesare Rubini per portarlo in terra lombarda in modo da allestire la Triestina Milano e con l’intento, non secondario, di tenere viva la questione dell’italianità dell’alabarda. Sarà ripagato adeguatamente dal gruppo di irriducibili che, col marchio Borletti, dominerà la scena nazionale per un lungo periodo e avrà la soddisfazione di misurarsi con i fantastici Harlem Globetrotters davanti ai ventiduemila spettatori del Vigorelli.

L’imprenditore trevigiano forgia il Principe in tutto e per tutto. Una nobiltà conquistata con la forza della povertà cui si aggiungeranno ulteriori etichette: Padrino, a giudizio dei detrattori, Monacone per gli amici della pallanuoto (il vero amore) e compagni dell’oro olimpico conquistato ai Giochi di Londra. Cesare indossa con disinvoltura numerosi abiti, da giocatore, allenatore e dirigente. Sta con un piede in palestra e con l’altro in piscina raccogliendo scudetti e attestati a non finire nelle varie competizioni, nella certezza che alla gloria è preferibile la gloria con i quattrini. Così opterà per la palla a spicchi, “attrezzo” di lavoro e fonte di ragguardevoli opportunità.

“Ironia della (buona) sorte è che la Milano del domani viene abbozzata in… ‘California’.”

“U.S. Funnily enough, the future champions of Olimpia Milano started off in ... ‘California’.”

De Coubertin non avrebbe potuto figurare neppure in panchina in una squadra che deve rispettare un comandamento fondamentale: chi dà per primo non è mai in debito. Sempre leoni in campo, spesso animali notturni pronti a combinarne di cotte e di crude, fidando nelle eccezionali doti di recupero. Si rende conto che non si vive soltanto di una debordante carica agonistica. Sa individuare gli uomini giusti, traduce efficacemente idee e progetti, può contare su una valida rete di collaboratori persino oltre oceano, tuttavia non conosce l’inglese e zoppica quanto al tatticismo da sfoderare durante gli incontri. Ecco, allora, il paracadute rappresentato da Sandro Gamba. Per completare la “rosa” di una formazione impegnata su vari fronti non si fa scrupoli nello strappare i fiori dal giardino di casa (Renzo Vecchiato è uno di questi), fra la disapprovazione dei suoi concittadini.

Un Principe non poteva che occupare un posto di riguardo nel regno del basket. La Hall of Fame di Springfield, nel Massachusetts, lo accoglie con il gratificante messaggio del Presidente Clinton. Nello stesso anno (1994) la sua città natale, da lui definita bella addormentata e prigioniera di un eterno scontento, gli consegnava il prestigioso “San Giusto d’oro” mentre la Trieste dei canestri assisteva, dopo quasi mezzo secolo, al secondo esodo verso Milano. Guarda la combinazione, protagonista del trasloco, stavolta originato dal matrimonio di interesse, è ancora un industriale della Marca, Bepi Stefanel, che si butta alle spalle rimpianti e polemiche.

GA

M BA

ENGLISH TEXT

22 IES, TRIESTE SPORTSLIFE N°22 –Autumn 2023 Memories

young, statuesque scorer, who let little Kobe carry his bag after training. The two made quite a pair: the future L.A. Lakers’ “Black Mamba” and Trieste’s “mulo” (i.e., Triestine dialect for “guy”) Graziano Cavazzon, who grew up playing for Ginnastica Triestina. At the peak of Kobe Bryant’s career, when reporters teased him about his selfish game style, blaming it on his childhood years in the Bel Paese, the Black Mamba would not flinch: “Aside from my considerable vertical jump, I owe everything else to Italy”.

“Te la do io l’America” (lit. I’ll show you America): a fitting refrain, born from an old sketch, and echoed in reference to Joe Bastianich’s cook book, both a threat and a promise…or, quite simply, a lesson: 18-year-old Giulio Iellini watched and learned. There was no time to waste as long as he was playing alongside Princeton and Oxford graduate Bill Bradley for Olimpia Milano. He was an avid observer, never missing any detail. Not even on 1st April 1966, an historic day for Olimpia Milano, before it was renamed Simmenthal Milano, at the 1965-66 FIBA European Champions Cup (European top-tier level professional basketball club competition, N/T), did he let himself get distracted by the

sights of the city of Bologna, where the game was to be held. On the eve of the final against Slavia VŠ Praha (now USK Praha N/T), Iellini managed to talk an astounded caretaker into unlocking the Palasport arena’s doors at the break of dawn, so that he could practice (barefoot) his free throw. When he came out, he was disappointed because he could “only” hoop 88 out of 100 shots. That same night, Captain Gianfranco Pieri (who had been able to amaze basketball giants such as Jerry West, Oscar Robertson, and Jerry Lucas at the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome, and who was the only player from the legendary Little Red Shoes formation) raised the team’s first Champions Cup. Seven years later Bradley joined the New York Knicks, winning two NBA championship rings (and earning the nickname “Dollar Bill”, because of his frugality, rather than his talent), before becoming U.S. Senator and running in the 2000 presidential primaries – he fell short, despite the endorsement of basketball star Michael Jordan, among others. There are also those who found America in Italy. The Allied Military Government of Occupied Territories in Trieste, still far from achieving its own peace and identity, brought in two

“Cesare Rubini indossa con disinvoltura numerosi abiti, da giocatore, allenatore e dirigente.”

“Cesare Rubini nonchalantly switched between his many roles: player, coach, manager.”

(unexceptional) Yankees, Robert Evans and John Philips, later replaced by talented John Mascioni, then an ItalianAmerican architect working at his third degree to obtain free accommodation in the U.S.

Funnily enough, the future champions of Olimpia Milano started off in … “California”, i.e., the nickname of a corner of one of Trieste’s oldest bathing establishments, Ausonia. This is where Treviso-born businessman and sports manager Adolfo Bogoncelli met future hall-of-famer Cesare Rubini, and was immediately won over. Bogoncelli brought Rubini to Milan to join the roster of his Triestina Milano (1945 team sponsored by Italian liberal-socialist and anti-fascist Action Party with the aim of promoting Trieste’s Italian identity). After a brief interval as Pallacanestro Como, in 1947 Bogoncelli merged former Triestina Milano and Borletti’s Olimpia to form a new society, known as “Borolimpia”. Bogoncelli’s original dream team repaid his vision and efforts playing against the spectacular Harlem Globetrotters in Milan’s velodrome “Vigorelli” in front of 22,000 viewers.

Cesare Rubini, known as “il Principe” (the Prince) despite his humble origin, owes much of his success to Bogoncelli’ managerial vision. He was also nicknamed “il Padrino”, mostly by his detractors, and “O’ Monacone” (lit. big monk) by his water polo friends and fellow Olympic gold medallists, who shared the 1943 victory in London. Cesare nonchalantly switched between his many roles: player, coach, manager, … one foot on the basketball court, the other in the water, collecting accolades and championship titles in both disciplines. He was deeply aware that fame and glory without money do not last, which is why he eventually set aside water polo (his true love) and devoted his professional life to basketball and its numerous career opportunities.

De Coubertin, founder and president of the International Olympic Committee, would never have made it in a team that must follow one rule: the first who gives owes nothing to anyone. Lions on the court, owls in the night, partners “in crime”, coming up with the craziest of stunts, confident that they would always recover in time for the next match. Cesare knew that competitiveness is not everything. He could spot the right man for each role, and effectively translate ideas into actions, knowing he could rely on a tight network of cooperation spanning all the

way across the Atlantic. However, he did not speak English and his tactical skills needed honing. Which is why he brought in Sandro Gamba. The Prince was ruthless when it came to completing his ideal formation and did not hesitate to pillage the team of his home town to get the players he wanted (such as Renzo Vecchiato), despite the disappointment of his fellow Triestini.

A Prince had to have his throne in the royal hall of basketball. Rubini was inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame in 1994, as announced by then U.S. President Bill Clinton. In the same year Trieste, his birthplace and, in his words, a sleeping beauty prisoner of her own unending discontent, honoured him with the prestigious “San Giusto d’oro” award – at the time when the city was, once again, being drained of her players, leaving for Milan. And, for the second time, the mastermind behind the drain was a businessman from the area of Treviso: Bepi Stefanel had brought Trieste’s team to the A League, but transferred his sponsorship to Olimpia Milano, amidst unforgotten regrets and controversies.

“Un Principe non poteva che occupare un posto di riguardo nel regno del basket.”

“A Prince had to have his throne in the royal hall of basketball.”

Dal dimenticato Richard Montgomery fino all’indimenticabile Javonte Green, tutti gli ambasciatori del basket USA in città.

From long-forgotten Richard Montgomery to unforgettable Javonte Green: all the ambassadors of American basketball to Trieste

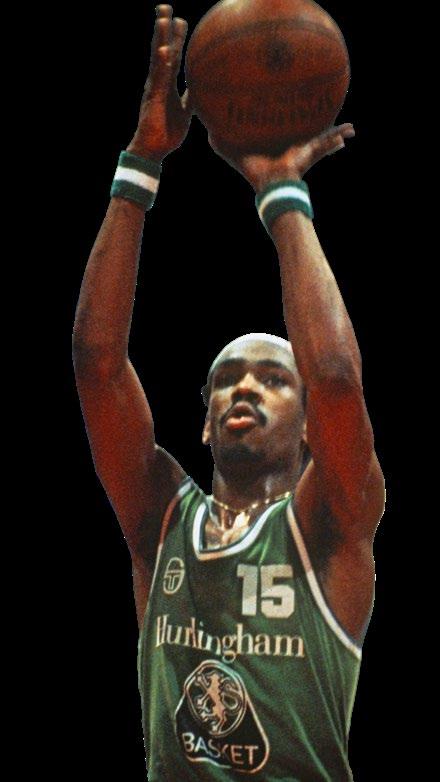

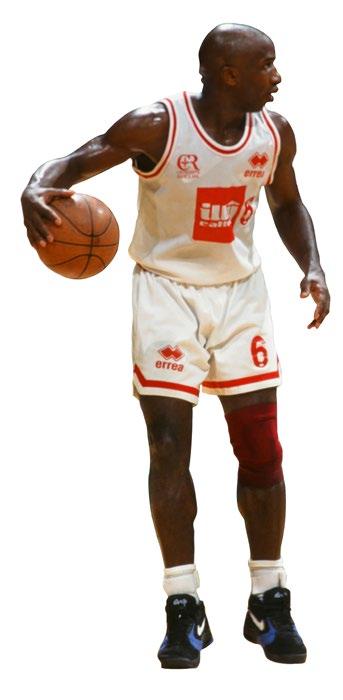

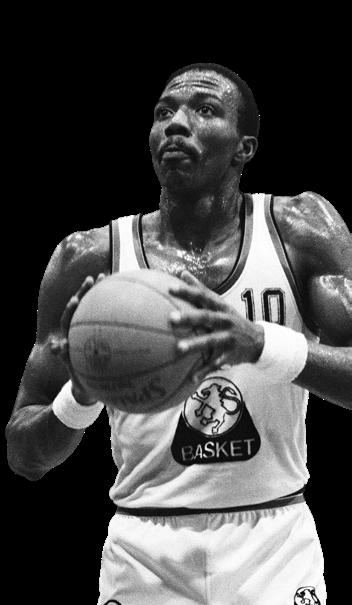

Predicatori e peccatori. Ex campioni Nba ed ex Harlem Globetrotter. Campioni e bidoni. Lunghi che nel volo sopra l’Oceano perdevano misteriosamente centimetri e altri che perdevano la capacità di giocare a basket. Giocatori che si innamoravano dell’Italia e altri che si innamoravano di un’italiana. Il basket triestino nella sua storia a stelle e strisce non si è fatto mancare niente. Nemmeno la disputa su chi sia stato in realtà il primo Usa della pallacanestro a Trieste. Qualcuno ricorderà negli anni Settanta Steve Brooks in maglia Lloyd Adriatico ma prima ancora, con la Sgt Stock, ci fu Richard Montgomery, californiano, arrivato in Italia a bordo del transatlantico Giulio Cesare nel 1957, che a Trieste trovò il primo ingaggio europeo e l’amore della sua vita.

La storia degli statunitensi al Palasport di Chiarbola (il PalaTrieste, o PalaRubini, o Allianz Dome doveva ancora arrivare) si divide in quelli arrivati prima di LUI – tra cui il predicatore Butch Taylor -e quelli giunti dopo di LUI. Il lui in questione è lo straniero più amato di sempre dai tifosi triestini. Rich Laurel. Quello che sarebbe diventato l’idolo di una città rischiò di venir tagliato appena presentatosi in palestra. Il coach, il vulcanico Dado Lombardi, appena lo vide entrare a Chiarbola aggredì verbalmente il general manager Ettore Zalateo.

“Ma chi mi hai portato? Guardalo, magro, sembra malato”. Zalateo, che prima di Laurel aveva già visto bocciare una lista di possibili candidati, non le mandò a dire. “Tientelo”. Fu l’affare della vita.

Il magrolino con la fascetta bianca sulla fronte incantò Chiarbola e portò per la prima volta la Pallacanestro Trieste

targata Hurlingham in serie A1.

Per interrompere un idillio così doveva accadere qualcosa di clamoroso. Marvin Barnes. Per rendere l’idea: alcuni sprazzi del basket più celestiale visto a Trieste ma –soprattutto– l’uragano che spezzò il giocattolo Hurlingham e scosse Trieste con il pasticciaccio passato alle cronache come lo scandalo di via Buonarroti. Quello che negli Usa era chiamato “Bad News” (Cattive notizie, e magari qualche sospetto poteva pure venire….) in un appartamento triestino diventava una Sex Machine. Droga e sesso. Dalle pagine di sport a quelle della cronaca nera. Fine del sogno. Addio Bad News. E bye bye a Rich Laurel. Tornato in età matura a Trieste per viverci.

Storie di americani. Di presuntuosi. Ammettiamolo: succedeva che giocatori arrivassero dagli States approcciandosi al basket italiano con superficialità, convinti che bastasse esprimersi al minimo sindacale per fare la differenza. Sbagliando. Difficile ricordare, ad esempio, una figura più barbina di quella rimediata da Jerome Harmon, impappinatosi perdendo una scarpa sul parquet perché non l’aveva allacciata bene.

Storie di americani. Di rimpianti. Il principale è legato a uno dei giocatori più egocentrici, egoisti ma anche dannatamente forti visti da queste parti. Steve Burtt è stato una formidabile macchina da canestri, puntava alla retina perché il suo credo cestistico era “io contro gli altri”. L’unica volta in cui tutti avrebbero voluto che andasse dritto a canestro ebbe la sciagurata idea di passare il pallone a un compagno, peraltro quello dotato di minor talento offensivo. E fu così che l’allora Illycaffè Trieste,

“Il basket triestino nella sua storia a stelle e strisce non si è fatto mancare niente.”

“The stars-and-stripes chapter of Trieste’s basketball history truly has it all.”

costruita sulle ceneri lasciate dal trasloco della Stefanel a Milano, non vinse una incredibile finale di Coppa Italia contro Treviso…

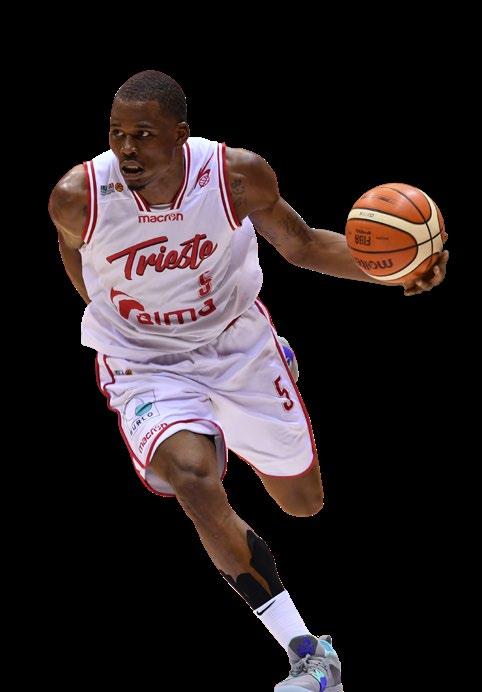

Storie di americani. Di lacrime e ricordi. Conrad McRae era un giovane lungo in grado di volare. Lo chiamavano “Mangiafuoco” perché lui, con un pallone infuocato, era riuscito a schiacciare. Talento atletico impressionante, qualche uscita sopra le righe ma gliela perdonavi perché era un generoso. E non solo d’animo. Accettò di rinviare un viaggio negli Usa dopo la notizia della morte del padre per aiutare Trieste a espugnare il PalaEur di Roma nei play-off. L’uomo che sapeva volare aveva un sogno: giocare stabilmente nella Nba. Ma il destino si rivelò l’avversario più implacabile: in un maledetto giorno di luglio, nel 2000, in attesa di una nuova occasione nella Summer League, il cuore lo tradì. Uno choc per tutti i tifosi di Trieste che lo adoravano e gli avevano dedicato un coro. Storie di americani. Di scommesse vinte. La Pallacanestro Trieste nell’estate del 2016 pesca nella terza lega spagnola, dallo sconosciuto club del Peixe, l’esterno Javonte Green. Atletico è atletico ma è uno degli stranieri con il curriculum più scarno mai visti da queste parti. Ci pensa il buon Green a fugare i dubbi. Una forza della natura. La dimostrazione vivente del divertimento e della spettacolarità del basket. Riporta Trieste in serie A. Impossibile trattenere ancora un talento così. Va in Germania a Ulma e poi va a giocarsi le sue carte nella Nba. Riuscendoci, visto che ci gioca tuttora. Trieste si accontenta di seguirlo da lontano. La porta del PalaTrieste per Green però resta sempre aperta.

Preachers and sinners. Former NBA stars and Harlem Globetrotters. Champs and scams. Giants, who mysteriously lost a few inches or their ability to play as they flew over the Atlantic to land in the Bel Paese. Players that fell in love with Italy, others who fell in love in Italy. The stars-and-stripes chapter of Trieste’s basketball history truly has it all – including an ongoing debate to determine who is the first American basketball player who joined Trieste’s team: most would indicate Steve Brooks, who played for Lloyd Adriatico in the ‘70s; yet others could point out that Richard Montgomery actually reached Trieste on ocean liner “Giulio Cesare” in 1957: the Stock Trieste’s jersey marked the first European contract signed by this Californian player, who found the love of his life in the city of Trieste.

Before PalaTrieste, PalaRubini, and Allianz Dome, it was Chiarbola Palasport indoor sporting arena that witnessed a constant flow of American players feeding the roster of Trieste’s home team throughout the decades. The timeline, however, is divided into a “before” and an “after”: those who came before HIM – including preacher Butch Taylor, and those who came after HIM. The watershed is Rich Laurel, Trieste’s most beloved foreign basketball player. Laurel’s Triestine adventure got off to a rocky start: the first time he showed up for training, hot-blooded coach Dado Lombardi took a look at him and flew into a rage, verbally attacking general manager Ettore Zalateo, “Who is this supposed to be? Look at him, all skin and bones, he looks ill”. Zalateo had already had enough of Lombardi

“Lo straniero più amato di sempre dai tifosi triestini: Rich Laurel.”

“Rich Laurel, Trieste’s most beloved foreign basketball player.”

rejecting potential candidates, so he cut him short: “He is all yours”. It was the deal of the century. The skinny American with his white headband immediately cast his spell over the entire arena and led Hurlingham Trieste to its first time in the A1 League.

Only something incredibly powerful could destroy such an idyllic picture. Or someone: Marvin Barnes. His name is synonym with some of the most spectacular games ever seen in Trieste, as well as the hurricane that wiped Hurlingham Trieste off the map and filled Trieste’s headlines with the scandal of Via Buonarroti. In the one year he played in Italy, Marvin “Bad News” Barnes (perhaps the most fitting name of all times) spent less time on the basketball court than he did behind the closed doors of his Trieste flat, which quickly became his personal temple of sex and drugs. His name slowly drifted away from the sports section, ending up first in the gossip columns and then in crime news. The idyll was over. Farewell, Bad News. So long, Rich Laurel (who would come back to Italy decades later to live in Trieste).

Americans and their American stories. Tales of arrogance. Let’s be honest: more than a few U.S. players came to Italy thinking they could very well afford to laze about, putting little to no effort into their game and still make a difference. But they were wrong. Suffice it to mention the humiliating view of a player like Jerome Harmon stumbling across the court and losing his shoe, because he could not be bothered to tie it properly.

Americans and their American stories. Tales of regret. The greatest one concerning Steve Burtt, one of the best, yet also most egotistical and self-centred

players ever seen in these parts. Burtt was a scoring machine, eyes constantly fixed on the net, following a strict “me against the world” mindset. The only time his selfishness was actually needed to score, he had the unfortunate impulse of acting in accordance with his point guard position for once, and passed the ball to the teammate with the least offensive skill. It was the Italian Basketball Cup final, Illycaffé Trieste had just recovered from Stefanel’s defection to Milan, and Burtt’s mistake costed Trieste the national title, which was won by Benetton Treviso instead…

Americans and their American sto ries. Tales of tears and memories. Young centre Conrad McRae could fly. He was nicknamed “Mangiafuoco” (lit. fire eat er) because of his slam dunk with a ball that was actually on fire. A tremendous talent, a little over the top, perhaps, but that was easy to forgive, for he was also a generous player – and a generous soul. After his father died, he agreed to postpone his flight to the U.S., because he would not abandon his teammates

“Storie di americani. Di lacrime e di ricordi.”

“Americans and their stories. Tales of tears and memories.”Marvin Barnes

during the play-off match at the PalaEur in Rome. The man who could fly had one dream: the NBA. But fate, it turned out, had other plans for Conrad: on that cursed day of July 2000, waiting for his second chance in the Summer League, his heart gave out. When the news reached Trieste, basketball fans were devastated: they still loved him and had even made a chant for him.

Americans and their American stories. Tales of successful bets. In 2016 Pallacanestro Trieste fished out a dark horse of sorts: small forward Javonte Green, who was playing with Marín Peixegalego (“Peixe”) of the Spanish third division. He was athletic, yes, but his game record was the shortest a foreign player had ever brought to Trieste. Green let his game speak for itself. He was a force of nature, the very expression of the fun and entertaining side of basketball. He quickly led Trieste back to the top, the A League. His talent knew no limits: he went on to sign with Ratiopharm Ulm of the Basketball Bundesliga (Germany) and, in 2019, Green finally made his NBA debut. Trieste keeps track of his victories from afar. The doors of PalaTrieste will always be open for him.

“La porta del PalaTrieste per Green resta sempre aperta.”

“The doors of PalaTrieste will always be open for Green.”Javonte Green

Giovanni Marzini

Giovanni Marzini

Una memorabile serata con il mito

An unforgettable night with the legend

Ci sono giornate che un cronista non può dimenticare, perché restano scolpite nella sua mente, ora per ora. Se poi quel cronista è un poco più che trentenne, che ha la fortuna di viverle fianco a fianco con un mito del suo sport preferito, allora diventano pagine di storia destinate ad entrare nel suo Pantheon.

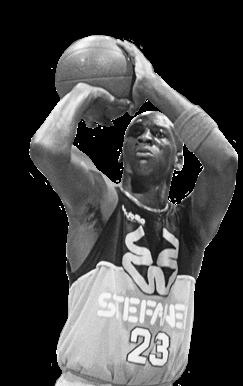

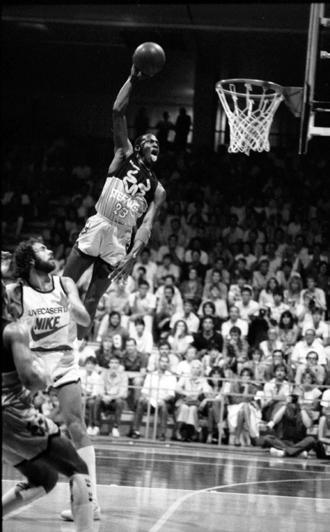

Era iniziato presto quel lunedì 25 agosto del 1985. Bisognava raggiungere Venezia per accogliere Michael Jeffrey Jordan, all’epoca 22enne. Era già qualcosa di più che una promessa. La Nike lo aveva ingaggiato per un contratto milionario e le sue scarpe si chiamavano già Air Jordan. Atterrava a Venezia proveniente da Parigi dove aveva lanciato una campagna pubblicitaria ad hoc. Ad attenderlo all’aeroporto ci sarebbe stato Bepi Stefanel ed un manipolo di dirigenti triestini della società che da un anno appena vestiva l’arancio e il nero del marchio veneto. Il blitz triestino di Jordan per un’amichevole a Chiarbola era stata un’autentica genialata, costata un bel po’ di soldini al nostro sponsor. Ma come certo saprete, si sarebbe trasformata in una clamorosa operazione di marketing, anche per un piccolo –poi diventato “storico”– particolare.

“A sensational marketing operation, especially thanks to a tiny detail that would be remembered as a milestone.”

Il vostro cronista avrebbe conosciuto MJ poco prima di mezzogiorno in un famoso ristorante di Venezia, blindatissimo per l’occasione. Pochissimi selezionati al tavolo, per un pranzo leggero a base di pesce. Jordan avrebbe dovuto raggiungere in macchina Trieste entro le 19. Partita programmata per le 20.30. Tre soli giorni di prevendita: avversaria la Juve Caserta di Bogdan Tanjević, già da anni squadra rivelazione della

massima serie. Pala Chiarbola praticamente sold out con richiesta di accrediti da mezza Italia.

A colazione appena iniziata, MJ fa una richiesta che ci lascia basiti. Ha saputo che Venezia ha un bellissimo campo da golf e chiede di poter fare qualche buca… Non sarà possibile. Per nostra fortuna. Si rispettano così i tempi e nel primo pomeriggio si riparte per Trieste.

Palazzetto gremito con buon anticipo. Perché già il riscaldamento diventa spettacolo, con le piroette di Michael. Il programma prevede primo tempo di MJ con maglia Stefanel, ripresa con la casacca bianca della Caserta di Tanjević, coach che quella sera entra per la prima volta a Chiarbola. Non sa ancora che quello sarebbe poi diventato il suo palazzo per otto anni. E la sua casa… per sempre! Al fianco di Jordan, con Santi Puglisi in panchina, il mito Bertolotti, l’artista Fischetto ed un manipolo di triestini, che ancor oggi conservano il nitido ricordo di quella sera: Zarotti, Colmani, Vitez, solo per citarne alcuni.

Il vostro cronista sta per godersi da par suo una serata indimenticabile. Seduto in postazione a bordo parquet, sta per iniziare la sua telecronaca del match per Telequattro Trieste. Palla a due, tutto pronto, si va!

Il ritmo e le giocate sono da esibizione NBA stile all star game, con la ricerca del preziosismo, anche se Caserta fa più sul serio. Per Boscia è un test match, a poche settimane dal via della stagione. Ma già dopo una manciata di minuti, ecco i trenta secondi che entreranno nella storia. Perché le scarpe bianco-rosse di AIR Jordan decidono di decollare dalla linea di tiro libero per

“Una clamorosa operazione di marketing, anche per un piccolo –poi diventato ‘storico’–particolare.”

To see Michael

concludersi con una strepitosa schiacciata, sigillata da MJ con il canestro ben stretto tra le mani del giocatore. Non sapeva il protagonista di quel gesto che in Italia i ferri sganciabili dal cristallo non erano stati ancora introdotti. Ed il tabellone si frantuma in mille pezzi. Qualche scheggia finisce pure sulla mia postazione, ma restiamo incolumi. A differenza del povero Lopez, l’uruguaiano di Tanjević, che finirà la serata in ospedale con i legamenti della mano recisi. Stagione finita prima di iniziare.

MJ, alla ripresa del match, dopo oltre mezz’ora persa per sostituire il canestro, giocherà l’intera partita in maglia Stefanel (Boscia non lo vuole con i suoi dopo l’incidente!) portando al successo Trieste senza mai far più una schiacciata, ma deliziando ugualmente la platea. E le scarpe di quel volo devastante, trent’anni dopo verranno battute all’asta a New York per oltre mezzo milione di dollari. Ma il vostro cronista, quasi 40 anni dopo, è in grado di svelarvi un piccolo grande segreto. Le scarpe usate in quel volo non sono quelle vendute all’asta, perché a fine partita Michael quelle indossate le aveva già regalate ad un giocatore di Trieste. Il suo nome… alla prossima puntata.

There are days in the life of a reporter one could never forget. Events that are fixed in one’s memory. Each second is carved in stone. Even more so if such events take place when said reporter is barely thirty years old and they involve the presence of the reporter’s basketball idol: those memories become pages of history, to be preserved and cherished forever. The 25th August 1985 was a Monday. We left from Trieste quite early in the morning to reach Venice in time to welcome then 22-year-old Michael Jeffrey Jordan. The young Chicago Bulls’ rookie was already showing more than promise. He had just signed a million-dollar contract with Nike, with the creation of Jordan’s signature shoe, called Air Jordan. He was supposed to land in Venice after shooting a dedicated commercial in Paris to promote his shoes. The welcome committee at the airport was led by Bepi Stefanel, who had just signed the sponsorship deal with the managers of Trieste’s home team, now wearing the brand’s orange and black uniforms. The one-night Nike exhibition game at Chiarbola arena in Trieste was a stroke of genius – and an expensive one at that. Yet, it turned out to be worth every penny, as it was destined to become a sensational marketing operation, especially thanks to a tiny detail that would be remembered as a milestone. Yours truly met MJ at lunch, behind the heavily secured doors of one of Venice’s famous restaurants. A small party of few selected guests and a light meal of fish courses. Jordan’s schedule was tight: he would reach Trieste by car just an hour and a half before the game, set to start at 8:30 p.m. that night. Three days of pre-sale tickets and the Chiarbola arena was already sold out, while entry accreditation requests kept pouring in from all over the country. The guest side was Bogdan Tanjević’s JuveCaserta, one of the best A League underdog teams at the time.

Just a few minutes into lunch MJ wrong-footed the entire party with an unusual request: he had read about Venice’s stunning golf course and would like to hit the links. Impossible, too little time – unfortunately for him, luckily for us. After lunch we left, on time, for Trieste. Hours before the game the arena was already packed: the audience was eager to see him, and, after all, even

“Il ritmo e le giocate sono da esibizione NBA stile all star game.”

“The game tempo and moves were pure exhibition, NBA All-Star style.”

a simple warm up is worth watching, when Michael Jordan is in the house. MJ would play the first half of the game wearing Stefanel’s colours, and then he would switch to the white jersey of JuveCaserta for the second half. It was coach Tanjević’s first time at Chiarbola arena: little did he know that he would spend eight years of his coaching career within these very walls – and that the city of Trieste would become his forever home. With coach Santi Puglisi in the bleachers, Jordan wore the orange and black of Pallacanestro Trieste, side by side with sensational swingman Bertolotti, artist Fischetto, and a handful of other Triestini who would forever remember that night: Zarotti, Colmani, Vitez, just to name a few.

I reached my courtside seat, ready for the play-by-play to be broadcast on Telequattro Trieste. All I knew at that point was that I was about to live an unforgettable night. Ready, jump ball, go!

The game tempo and moves were pure exhibition, NBA All-Star style, right from the start. JuveCaserta, however, seemed to mean business: it was a test match for coach Boša, a few weeks from the beginning of the season. And then it happens. Air Jordan’s red and white

sneakers take off from the foul line, one of His Airness’s spectacular mad ups. He flushes hard, sealing the dunk by firmly grabbing the net of the hoop. However, cut-out hooks had not been introduced in Italy yet. The glass of the backboard shatters. A few glass splinters reach the courtside, but the audience is unharmed. Unlike Tanjević’s Horacio “Tato” López, who ends up in the hospital with a serious hand ligament injury, which will cause him to miss the entire season. It took more than half an hour to replace the hoop. When the game could finally resume, it was decided that MJ would play with the Pallacanestro

Trieste side for the rest of the game (Boša no longer wanted him too close to his players after the accident). There were no more dunks that night, but Jordan put on quite a show to the audience’s delight, and Pallacanestro Trieste won. Thirty years later those red and white flying shoes sold for $560,000 at a Sotheby’s auction. However, I can let you in on a secret: the Air Jordan 1S sneakers that were auctioned off in New York are not the ones MJ was wearing that night. Immediately after the game, Michael gave his shoes as a gift to a member of his team. His name…will be revealed in the next episode.

“Le scarpe di quel volo devastante, trent’anni dopo verranno battute all’asta a New York per oltre mezzo milione di dollari.”

“Thirty years later those red and white flying shoes sold for $560,000 at a Sotheby’s auction.”

Guido Roberti

foto di /Photos by Linda Cravagna

Guido Roberti

foto di /Photos by Linda Cravagna

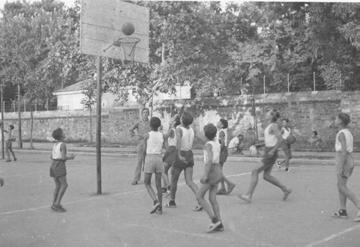

Non solo la palestra. I campi all’aperto, una passione che pervade i giovani triestini. “Muli, PCA o Revoltella?” Nei giorni di primavera è il dubbio che affligge i giovani cestisti, non paghi della sola attività in palestra, troppo affamati di questo sport per rinunciare ad un 3 contro 3 con l’unico dogma di dare spazio all’estro che in società talvolta è limitato nell’interesse del gruppo. Luoghi iconici a Trieste, i campi all’aperto di Piazza Carlo Alberto (PCA!) e Revoltella (nel parco omonimo), essi stessi un gergo triestino che pervade la fascia d’età in cui il lavoro è prospettiva lontana e l’ora alternativa allo studio si può concedere. In PCA ci si immerge in una architettura liberty che ricorda campetti open-air USA, e c’è un volto dipinto sui tabelloni. Mitja Gasparo, un ragazzo come tanti innamorato di basket, un ragazzo come tanti con un cuore a spicchi. Un ragazzo, come pochi, strappato alla vita a 24 anni da un dannato incidente. I capelli ricci di Mitja accompagnano le evoluzioni playground di tanti giovani, lì dove non c’è l’allenatore a tediarti per una tripla in più. Trieste è questo, provincia più piccola d’Italia e un concentrato di società operanti a livelli minibasket-giovanili da far invidia. Una trentina di società, migliaia di atleti, neanche la pandemia ha abbattuto i numeri. Un amore che varca le palestre e si sposta ai campi all’aperto. Dove chissà, si cela un futuro volto della Nazionale. In fondo dietro a un pallone c’è sempre un sogno. Non è più la Trieste dei ricreatori. Cambiano luoghi e modi, ma nel dna dei piccoli l’attrazione per questo sport sembra non subire alcun influsso discendente. “Time-out”, solo per dissetarsi, in PCA non c’è il coach a chiamarlo. “Val tutto”, dicono i giovani.

Indoor sports discover the open air: outdoor basketball is the new craze of young Triestini.

“Guys! PCA or Revoltella?” is the question echoing in young basketball players’ conversations on spring days: as temperatures rise, so does the desire to play outside, which, in basketball, means 3-on-3 games, where creativity rules the day. Trieste’s most iconic outdoor half courts are the one in Piazza Carlo Alberto (PCA!) and the one known as “Revoltella”, located in the park of the same name. Both have now become part of local youth jargon, usually associated with a couple of stolen hours after school, right before homework time. PCA’s atmosphere closely resembles that of U.S. streetbasketball backyards, here surrounded by liberty-style architecture, with the face of Mitja Gasparo watching over the court from the backboards. Gasparo was just an ordinary young man, who loved basketball, like so many of his peers. Unlike his peers, however, he met his end in a tragic accident when he was only 24. Today, his curly hair seems to sway still, as if his gaze was following the players’ moves – here, where no coach is going to yell at you for travelling, when no one else notices. This is Trieste: Italy’s smallest province (here referring to Italy’s secondlevel administrative division, N/T) and a powerhouse of biddy-basketball teams. Over thirty clubs and thousands of young athletes, whose passion for basketball was even stronger than the pandemic. So strong, in fact, that it is now spilling out of the city’s indoor arenas to invade outdoor courts. And, who knows? The future national team’s roster may be dribbling there right now – after all, behind every basketball there hides a dream. True: Trieste is no longer the city of ricreatori. Yet, while structures and places may change, there will always be a basketball genetic marker in young Triestini’s DNA. Someone calls “Time out!” for a quick gulp of water – no one in PCA is counting down seconds from the bleachers, anyway. “Everything goes”, this is the kids’ motto.

A sinistra /Left

Il campetto di Barcola

A sinistra /Left

Il campetto di Barcola

A destra /Right

Piazza Carlo Alberto

A destra /Right

Piazza Carlo Alberto

Dopo anni di basket giocato, nel 2009 tra le palestre trentine e lombarde inizio a divertirmi con la fotografia sui campi da basket. Tornata a Trieste nel 2012 inizio a collaborare con alcune testate giornalistiche locali e nazionali, fotografando la serie A e guadagnandomi un posto tra i fotografi degli Europei a Koper. Dal 2014 unisco anche il mio amore per i bambini, e ad oggi sono una fotografa specializzata in bambini e famiglie e fotografia sportiva.

After playing basketball for years, in 2009 I started taking recreational pictures of basketball players between Trentino and Lombardy. In 2012 I moved back to Trieste and started working as A-League photographer for local and national newspapers, landing a place in the official news crew of Koper European Championship. In 2014 I was able to combine sport photography with my other passion, children- and family photography, eventually specialising in both fields.

L’uso efficiente delle risorse energetiche esige la ricerca di un punto di equilibrio tra obiettivi di risparmio ed esigenze produttive.

EnerProject identifica, implementa ed investe in soluzioni ingegneristiche e di processo, che permettano ai propri clienti di ridurre drasticamente la propria spesa energetica.

Sono clienti EnerProject:

1. Anna Frank, via Forlanini, 30

2. Brunner via Solitro, 10

3. Cobolli Strada Vecchia dell’Istria, 76

4. De Amicis via Colautti, 3

5. Fonda Savio via Doberdò, 20/4

6. Gentilli via di Servola, 127

7. Lucchini via Biasoletto, 14

8. Nordio Pendice dello Scoglietto, 22

9. Padovan via Settefontane, 43

10. Pitteri via San Marco, 5

11. Ricceri via Reiss Romoli, 14

12. Stuparich viale Miramare, 131

13. Toti via del Castello, 1 - 3

1. Bor Basket strada di Guardiella, 7

2. Breg Basket San Dorligo della Valle, 462

3. Repubblica dei Ragazzi (Azzurra basket) largo Papa Giovanni, 7

4. Servolana basket via Soncini, 187

5. Campo del Kontovel Contovello, 152

6. Campo del Polet, Opicina via del Ricreatorio, 1

7. Asd Polisportiva, Opicina via degli Alpini, 128

8. M. Ervatti Borgo Grotta Gigante, 67

9. Campo Sportivo Villa Ara via Monte Cengio, 2

10. Circolo Canottieri Saturnia viale Miramare, 36

11. ASD Santos Basket Guardiella via Timignano, 2/1

12. Canestro pineta di Barcola

13. Campo di piazza Carlo Alberto

1. Don Bosco via dell’Istria, 53

2. San Vincenzo de’ Paoli via Ananian, 1

3. San Giuseppe Montuzza via Tommaso Grossi, 4 (solo 1 canestro)

4. Oratorio Sion, Centro Pastorale Paolo VI, via Tigor, 24

5. Oratorio San Michele al Carnale Piazza della Cattedrale, 4

6. Chiesa Parrocchiale San Luca Evangelista via Carlo Forlanini, 26

7. Don Dario via Umago, 5

14. Campo del Parco Revoltella

15. Borgo S. Sergio via Eugenio Curiel

Where do we play today?

The city, court by court

Se Trieste può essere considerata l’eponimo della pallacanestro italiana, i Ricreatori Comunali lo sono di Trieste. Dei 37 nazionali quasi la totalità si è avvicinata al basket nei ricreatori. Per divertimento, per gioco, indirizzati dagli insegnanti, dagli amici, dai genitori. Per loro la pallacanestro era un modo per stare assieme agli amici. Era un gioco, una sfida a segnare un canestro da più lontano dell’amico.

Ancora adesso Trieste è la città che ha fornito più atleti alla nazionale. Ben 37. Il mito Cesare Rubini, il grande Gianfranco Pieri, il classico Iellini, la torre Vecchiato, i più recenti Tonut, de Pol, Attruia, Pozzecco, Pecile, Cavaliero sono solo la punta dell’iceberg del movimento triestino. Che nei tempi eroici ne schierava anche tre o quattro per formazione.

Per questo Trieste meriterebbe di essere chiamata “la città della pallacanestro”. Come Zara che è (ufficialmente) Zadar, Grad košarke. Per l’appunto Zara, la città del basket. Con tanto di statua e viale in onore del suo giocatore più famoso, Krešimir Ćosić.

Il primo ricreatorio (Giglio Padovan) venne ufficialmente aperto il 25 aprile 1908 dopo parecchi anni di studio e tante pressioni all’amministrazione comunale da parte di Nicolò Cobolli. Fu uno dei più bei lasciti dell’amministrazione austriaca e da subito un successone tanto che in breve tempo se ne aggiunsero tanti altri, fino a raggiungere il bel numero di 15. Cioè uno in ogni rione della città.

L’apertura era pomeridiana con grande spazio alle “attività ginniche”. Cobolli

Quando in Italia non esistevano ancora i playground, a Trieste si giocava nei ricreatori. Uno in ogni rione. I ricreatori sono un’istituzione che esiste qui e solo qui.

Creati dal Comune nei primi anni del novecento, luoghi di ricreazione di impostazione laica per offrire un servizio sociale educativo e ludico, rivolto ai ragazzi e ai giovani, dai 5 ai 19 anni. Un vero vanto della città, un vivaio importante per il basket, dove sono nati grandi campioni.

–

Before the introduction of playgrounds at national level, basketball was played in Trieste’s ricreatori. One in each city district. Ricreatori are unique institutions, with no equivalent in the rest of the country. Trieste municipality created them in the early 20th century to provide young citizens from 5 to 19 years of age with non-religious recreation centres offering learning and recreational activities. A true badge of honour for the city, and a national basketball nursery, breeding some of Italy’s greatest champions.

comunali: la passione è nata qui — Ricreatori comunali: where passion is born

riteneva che:“ Il problema più importante del secolo presente per la gioventù è l’educazione, che purtroppo oggi è una parola vaga, un problema trascurato i cui effetti si vedono nella società per il germogliare continuo di un malessere, di un malcontento che si esplica con le più brutte forme ”. Parole che sembrano scritte ieri.

I ricreatori nacquero come attività complementare dell’istruzione scolastica con le loro biblioteche, la sala dei lavori manuali, il giardinaggio, la sezione banda e quella di cucito e ricamo. Ma quello che ragazzi e ragazze (dai 6 ai 14 anni) amavano di più era scorrazzare all’aperto nel campo giochi: le altalene, le giostre, le corse con i cerchi, le gare di tiro alla fune...

Dopo la I guerra mondiale però un’attività, uno sport emerse prepotentemente. La pallacanestro. Così i ricreatori, nati e cresciuti come un “doposcuola attivo”, mantennero tutte le loro attività e le finalità educative ma divennero ben presto il laboratorio dello sport giovanile a Trieste. E non solo della pallacanestro.

Quando nel 1921 nasce la Federazione Italiana Basketball si disputa pure la prima partita di pallacanestro a Trieste al ricreatorio De Amicis tra due formazioni del ricreatorio. In pochi anni gli altri ricreatori installano i primi canestri ed iniziano i tornei tra ricreatori, scuole e poi, con l’inclusione della pallacanestro nelle attività delle società di ginnastica locali, le gare tra società.

L’età dell’oro durò fino alla fine degli anni ‘80. Quando ogni ricreatorio era “obbligato” a partecipare al torneo dei maschi grandi (13-14 anni), dei maschi piccoli (11-12), delle femmine grandi (13-14) e delle femmine piccole (11-12).

I direttori dei ricreatori erano orgogliosi delle loro formazioni e il direttore generale Mario D’Urbino non ammetteva deroghe: “Impossibile non trovare almeno 5 che non sappiano fare un tiro a canestro”. Era come dire che i “maestri di campo” non facevano il loro mestiere.

Poi arrivò la crisi. Certi ricreatori decisero di non partecipare (“Abbiamo altre attività...”) e la direzione generale non aveva la forza (o il desiderio) d’intervenire. Sopravvissero per qualche anno le rappresentative, cioè le “nazionali” dei ricreatori che partecipavano ai campionati delle federazione. Erano composte dai migliori di quei tre - quattro ricreatori che ancora seguivano la tradizione. Gli altri non avevano più squadre. E nemmeno degli insegnanti appassionati. E fu il declino.

I ricreatori al giorno d’oggi sono sempre aperti dalle 14.30 alle 19.30, i canestri sono al loro posto. Cercasi campioni del futuro.

“Ancora adesso Trieste è la città che ha fornito più atleti alla nazionale.”

“Over the years, the majority of players who went on to play for Italy’s national team were trained in Trieste.”

If the city of Trieste is the quintessence of Italian basketball, Ricreatori Comunali are the quintessence of Trieste’s basketball. The majority of Italy’s national team members started off here, in one of the city’s ricreatori (i.e., recreation centres), where they saw their first basketball − some purely by chance, others following the suggestion of a teacher, friend, or parent. Playing basketball, then, was one way of spending time with friends – one of many games to challenge each other, for instance to see who could hit the hoop by throwing from the farthest point of the court.

Over the years, the majority of players who went on to play for Italy’s national team were trained in Trieste – 37, to be precise. The legendary Cesare Rubini, the amazing Gianfranco Pieri, the all-time great Iellini, Renzo “the Tower” Vecchiato; and, more recently, Tonut, de Pol, Attruia, Pozzecco, Pecile, Cavaliero, just to name the best of the best of Trieste’s large pool of athletes

– with the national team fielding a roster featuring up to four of them at a time in the past.