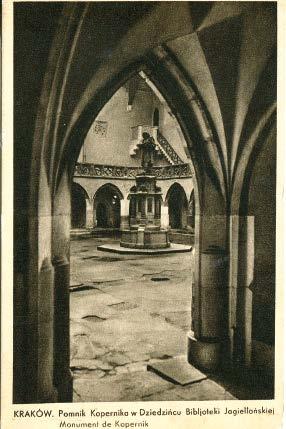

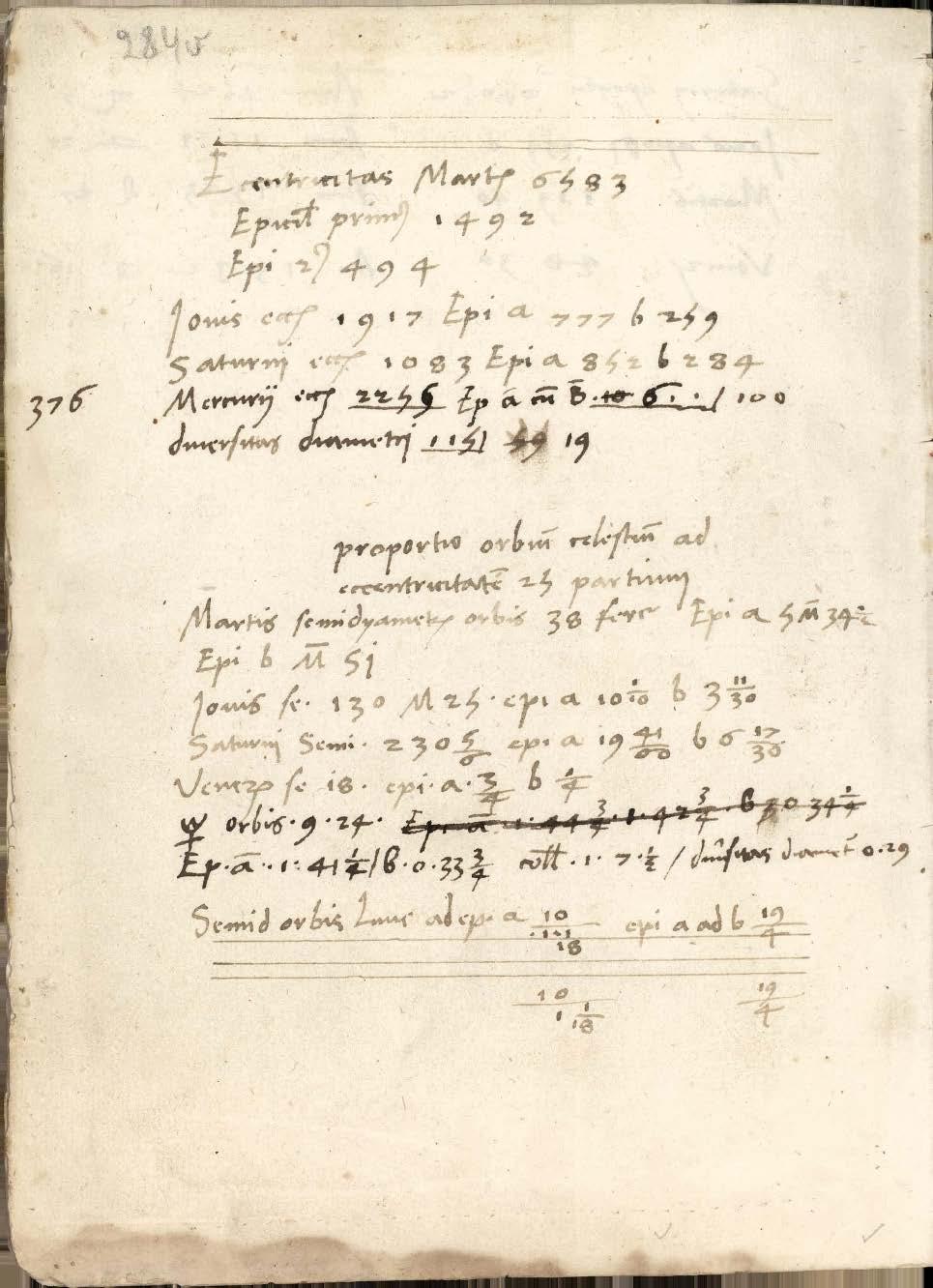

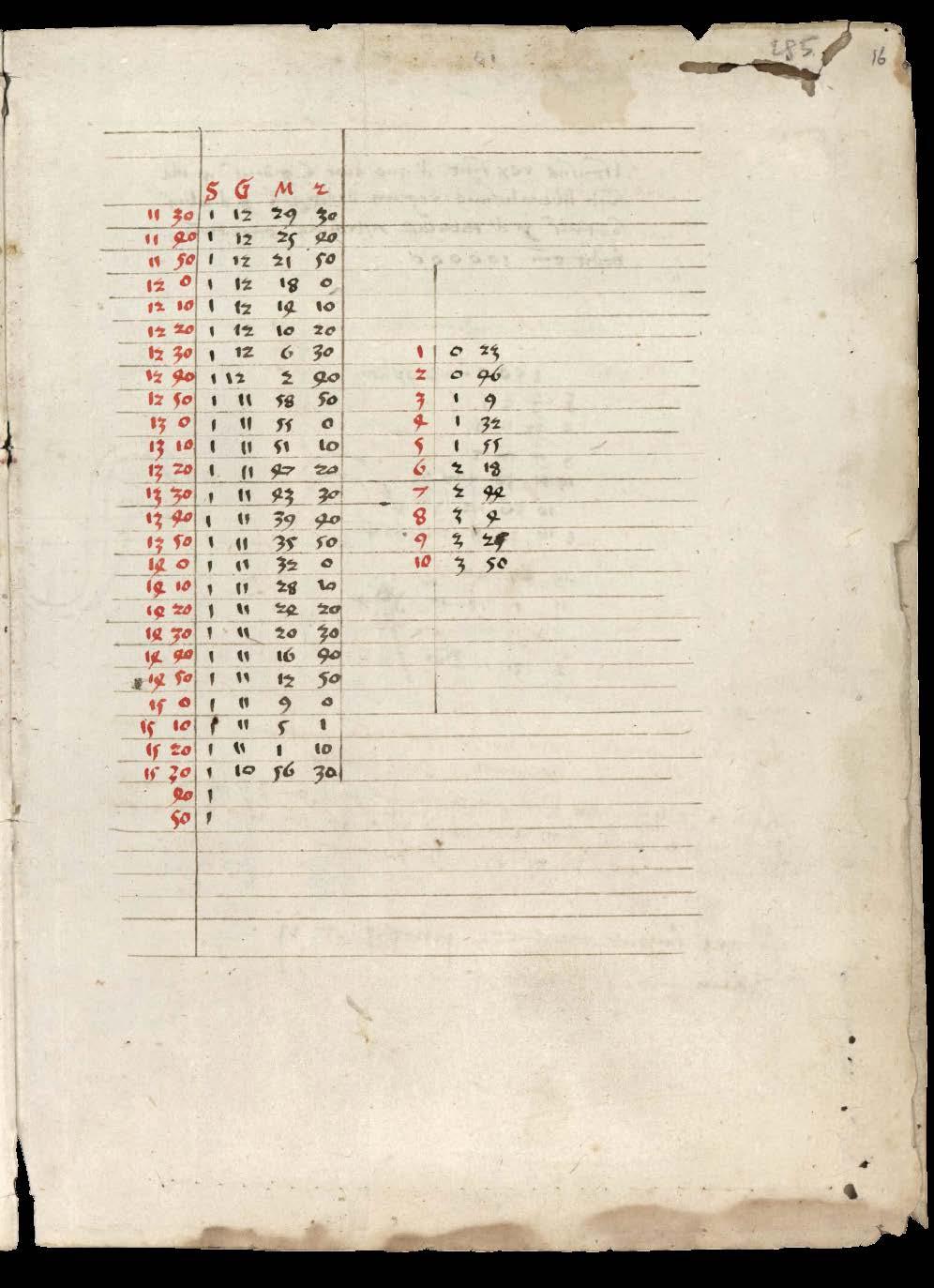

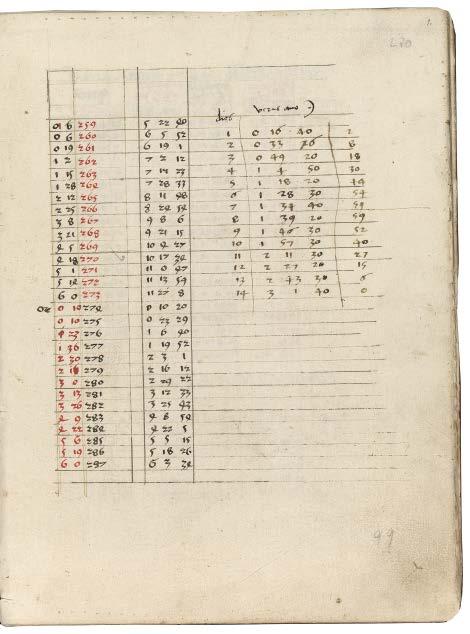

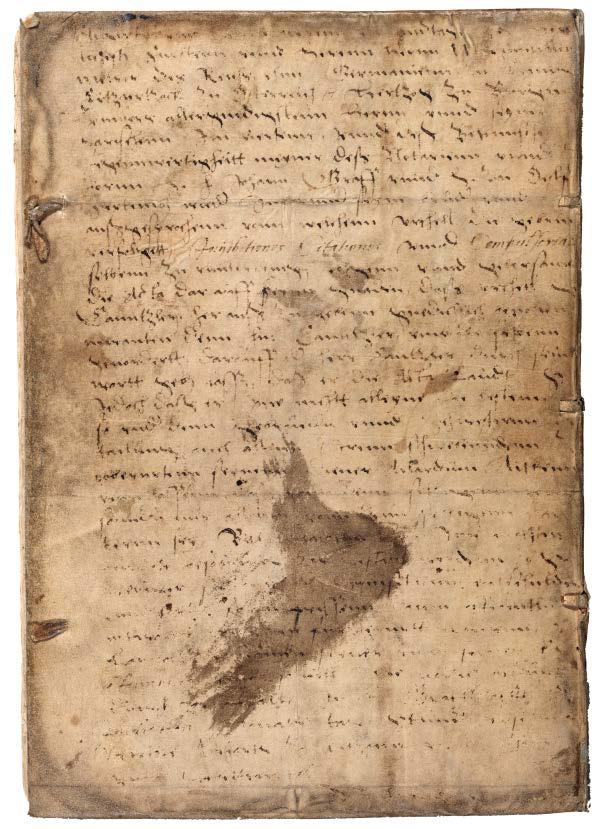

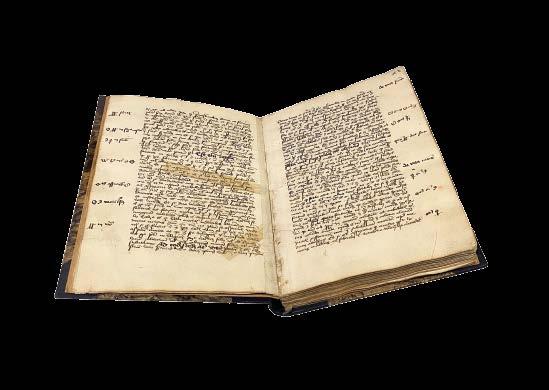

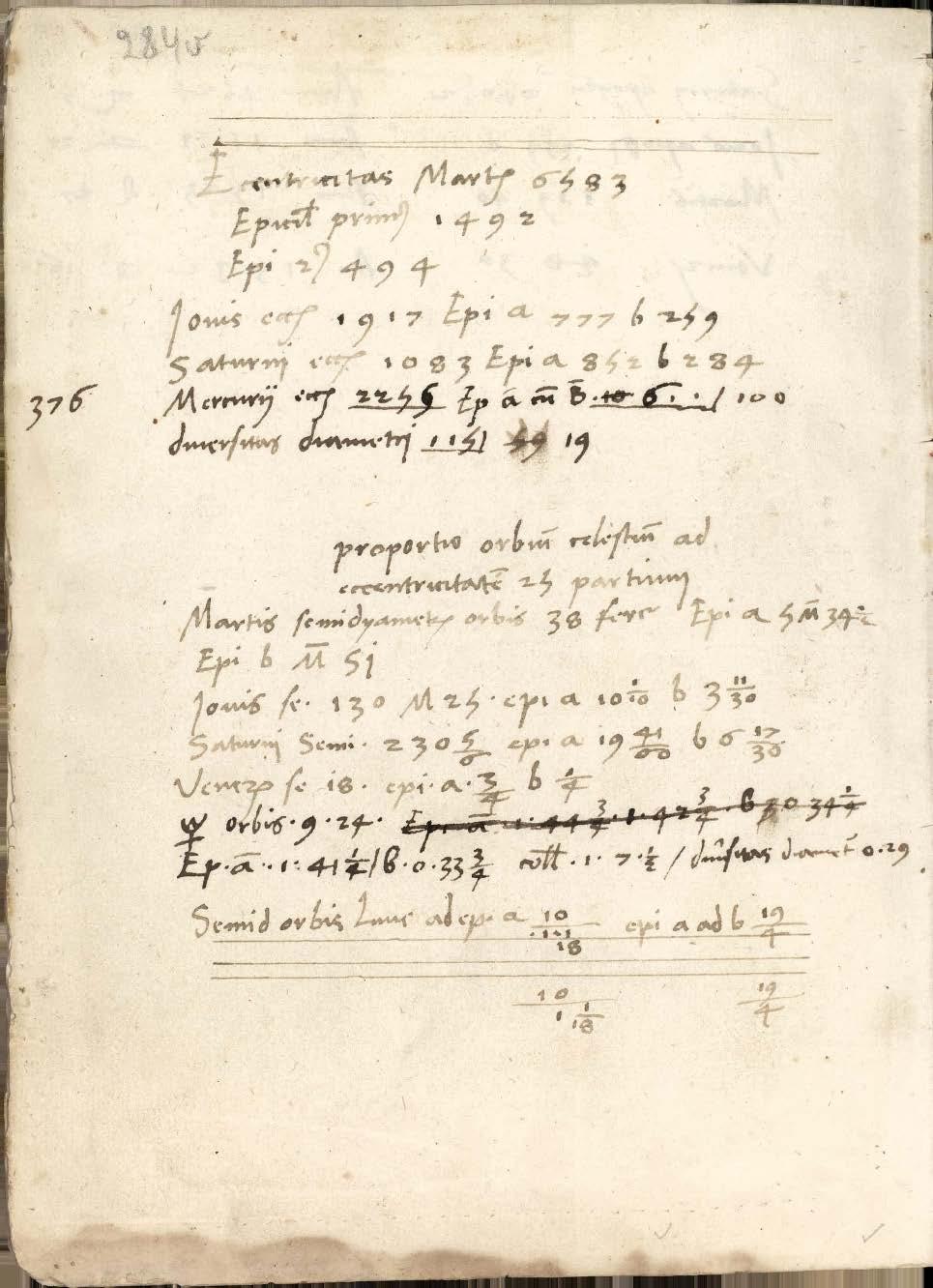

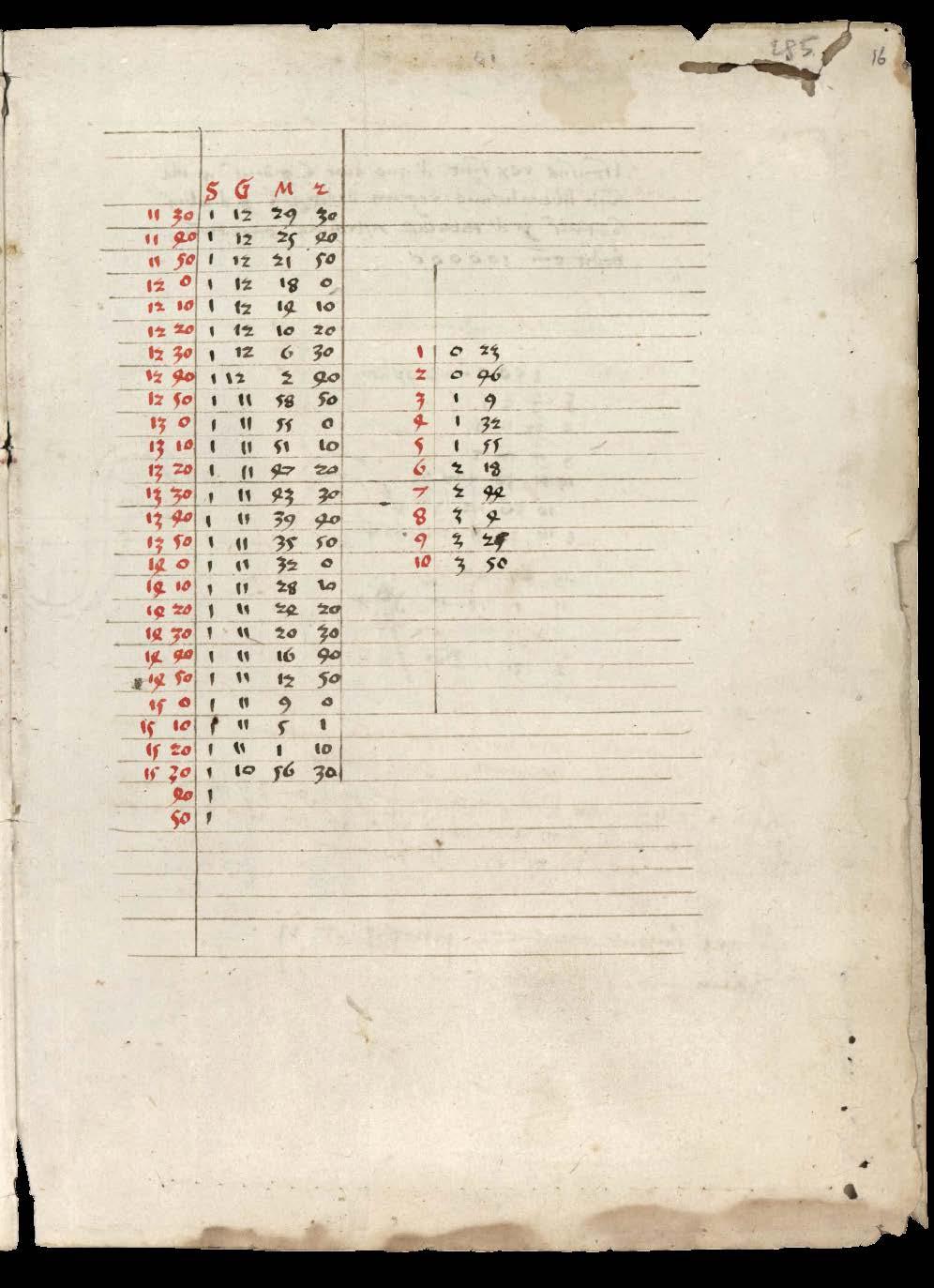

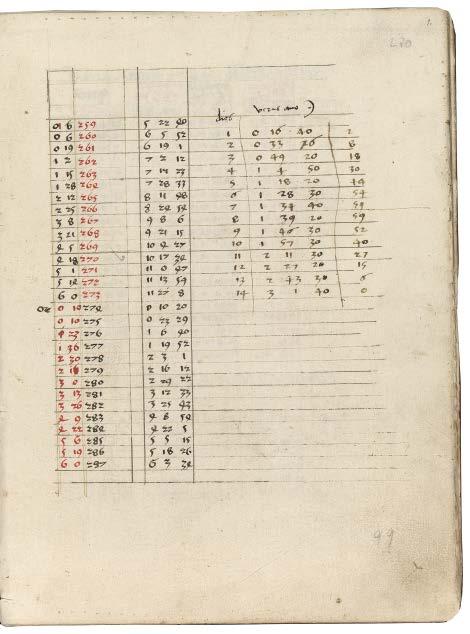

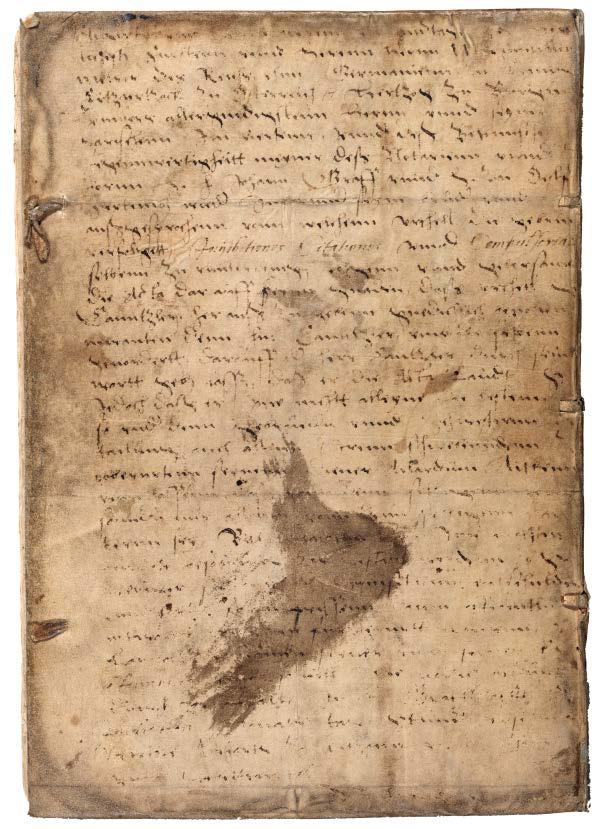

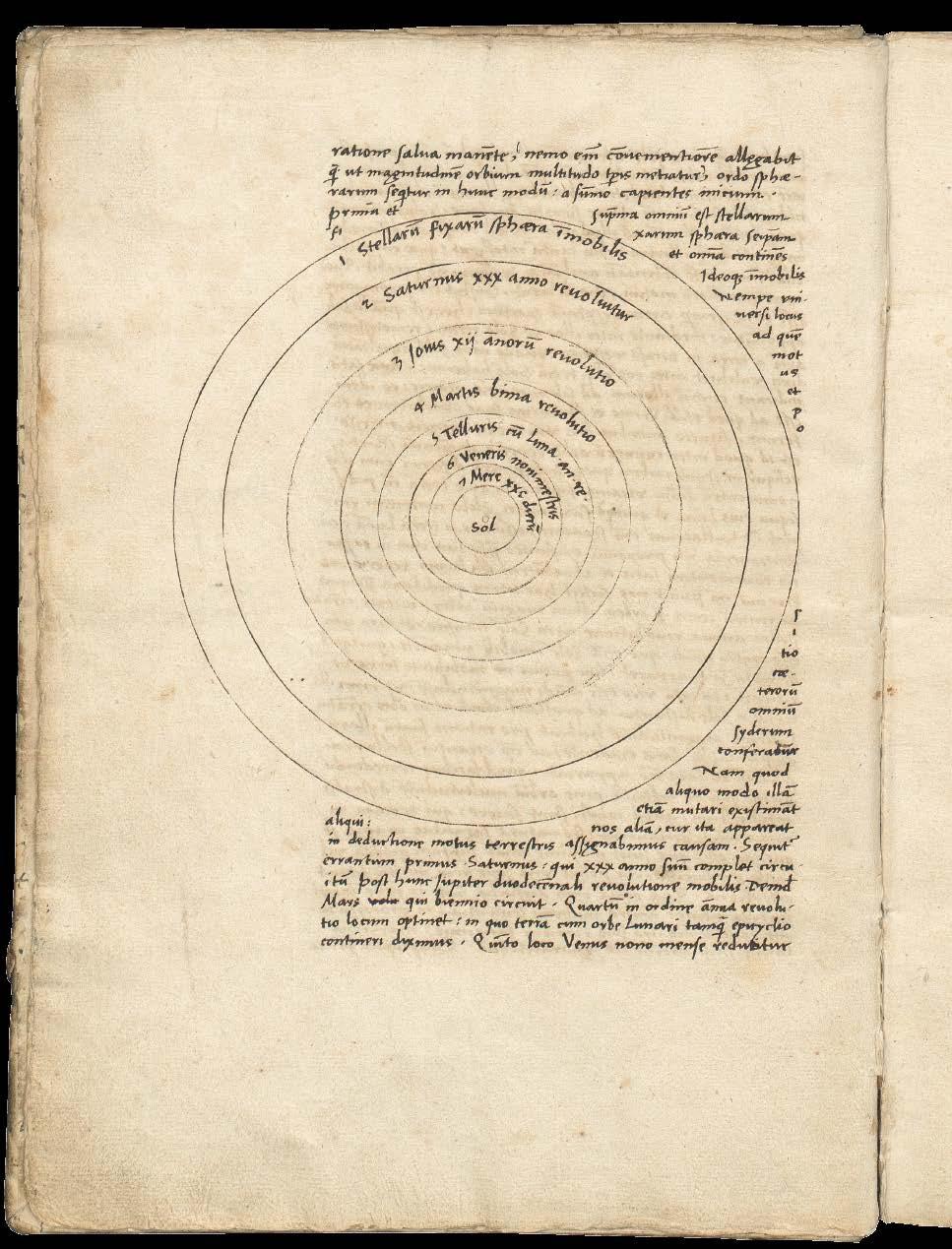

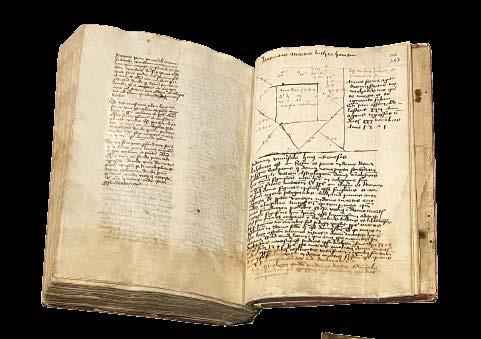

Part of a collection of 16 pages with astronomical tables and calculations, known as the Uppsala Notes. It contains astronomical observations handwritten by Nicolaus Copernicus. It is bound together with a copy of the Alfonsine Tables from 1492 and Regiomontanus’ tables from 1490. Originally the property of Nicolaus Copernicus, it later belonged to the archives of the Warmian cathedral chapter. Currently, it is part of the collection of the Uppsala University Library

Public domain

ALMA MATER TABLE OF CONTENTS

Jagiellonian University monthly magazine

Special edition No. 243/2023

EDITORIAL OFFICE

31-126 Kraków, ul. Michałowskiego 9/3 tel. +48 12 663 23 50

e-mail: almamater@uj.edu.pl www.almamater.uj.edu.pl www.instagram.com/almamateruj

PROGRAMME COUNCIL

Zbigniew Iwański

Antoni Jackowski

Zdzisław Pietrzyk

Aleksander B. Skotnicki Joachim Śliwa

ACADEMIC CONSULTANT

Jacek Popiel

EDITORIAL TEAM

Rita Pagacz-Moczarska – Chief Editor

Zofia Ciećkiewicz – Editor

Alicja Bielecka-Pieczka – Editor

Anna Wojnar – Photojournalist

ENGLISH TRANSLATION

Kamil Jodłowiec and Bartosz Zawiślak (except pages 38–45, 78–81 and 96)

PROOFREADING

Kamil Jodłowiec and Bartosz Zawiślak

He stopped the Sun and moved the Earth

Copernicus’ work has its roots in Kraków – An interview with Professor Marcin Karas by Rita Pagacz-Moczarska

PUBLISHER

Jagiellonian University

31-007 Kraków, ul. Gołębia 24

ORIGINAL IDEA AND LAYOUT FOR THE MAGAZINE

Rita Pagacz-Moczarska

PRE-PRESS

Agencja Reklamowa „NOVUM” www.novum.krakow.pl

PRINTED BY Drukarnia Pasaż sp. z o.o. 30-363 Kraków, ul. Rydlówka 24

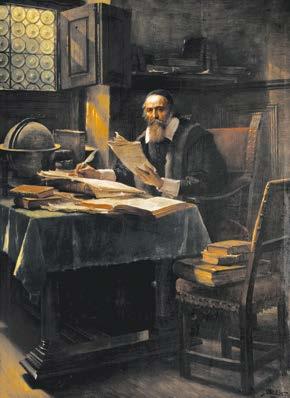

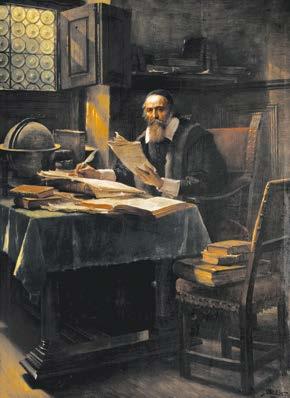

Cover photographs: Front – Jan Matejko, Astronomer Copernicus, or Conversations with God (fragment), 1873

Back – Statue of Nicolaus Copernicus in front of Collegium Witkowski

Photo by Rita Pagacz-Moczarska

The Editors do not return uncommissioned texts and reserve the right to abridge and edit submitted texts. The Editors are not liable for advertisements and notices.

Sent to print on September 15, 2023.

ISSN 1427-1176

Print run: 1000 copies

BANK

Uniwersytet Jagielloński PEKAO SA 87124047221111000048544672 marked ALMA MATER – darowizna

5

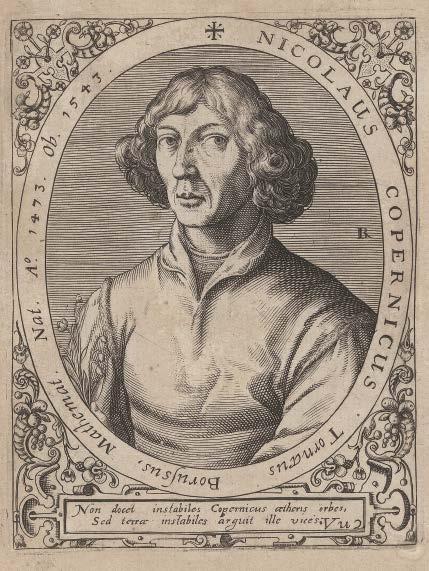

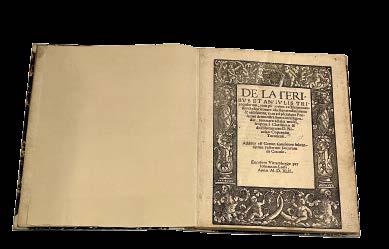

6 Images of Nicolaus Copernicus from the

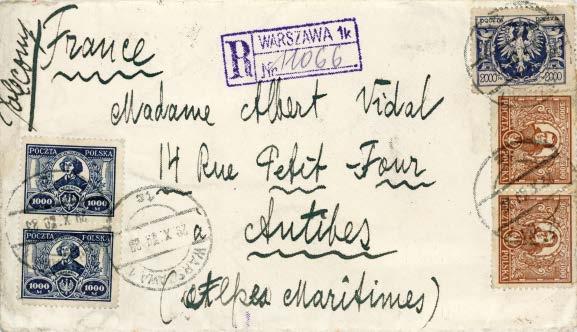

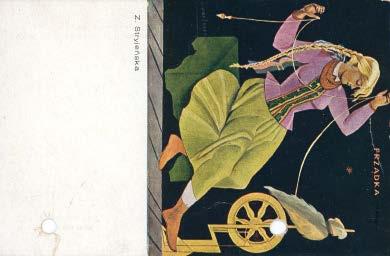

Jagiellonian Library 18 Key dates in Nicolaus Copernicus’ life 22 Krzysztof Stopka – Kraków, its university, Copernicus and his fame 24 Reverend Professor Michał Heller – Copernicus as a relativist 34 Zdzisław Pietrzyk – A history of the autograph manuscript of Nicolaus Copernicus’ De revolutionibus 38 Jacek Partyka, Wojciech Świeboda – Copernican collection in the Jagiellonian Library 46 Ryszard W. Gryglewski – Nicolaus Copernicus as a physician 50 Maciej Grodzicki – Traces of Nicolaus Copernicus’ reflections in modern economic thought 52 Astronomer Copernicus, or Conversations with God 56 Anna Lohn-Pieróg – Copernicus through the eyes of Matejko 58 Marcin Bojda – Escape from routine: Copernicus Treasury as an escape room 62 Selected Kraków Copernicana 68 Rita Pagacz-Moczarska – Copernicus in the Opera by Jan A. P. Kaczmarek 70 Copernicus in musical .............................................................................................................................. 71 Małgorzata Kusak – Nicolaus Copernicus – the restorer of astronomy 72 Unique items in the Jagiellonian Library collection 74 Natalia Bahlawan, Marcin Banaś – Copernicus and His World: exhibition at the Royal Castle in Warsaw 76 Bartosz Brożek – Science in the Centre of Culture: On the Copernicus Center for Interdisciplinary Studies 78 Jerzy Duda – Postal Copernicana 82 Copernican exhibition in the cellars of JU Collegium Maius .................................................................. 89 Statue of Nicolaus Copernicus in the Collegium Maius courtyard 90 Aleksander B. Skotnicki – The statue of Copernicus by Cyprian Godebski 92 Postcards with the statue of Nicolaus Copernicus in the courtyard of Collegium Maius 94

ACCOUNT

collection of the

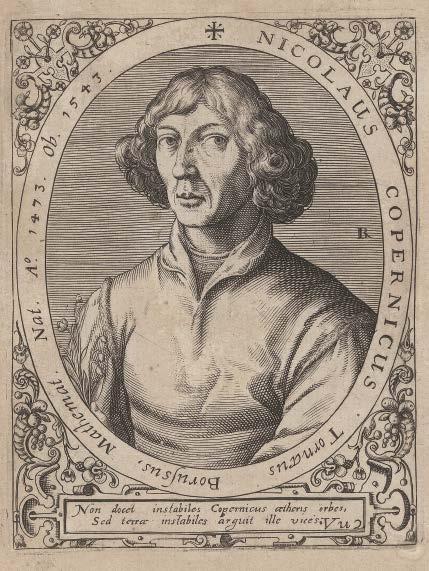

From the collection of the Jagiellonian Library

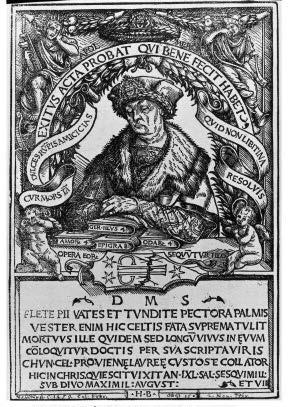

Portrait of Nicolaus Copernicus – a woodcut by Tobias Stimmer, published in Nicolaus Reusner’s Icones sive imagines virorum, Strasbourg 1587. Commonly thought to be the most veracious depiction of Copernicus

FROM ThE EdiTOR

True genius. Creator of the heliocentric model of the Universe. Astronomer, mathematician, physician, lawyer, economist, philosopher: one of the most remarkable students of the University of Kraków and at the same time one of the most famous men of science in the world. Nicolaus Copernicus. Why is he so extraordinary? What proof do we have that he was Polish? What did he wait for thirty years before publishing his earth-shattering work, De revolutionibus? What is the most spectacular lie about Copernicus? What can we still learn from him today? The articles published in this special edition of Alma Mater monthly are an attempt at answering these and many more questions about the life and passions of the exceptional Polish scholar. The issue is published to celebrate the 550th anniversary of the birth of Nicolaus Copernicus and the 480th anniversary of his death.

Copernicus was a modest man. He was characterised by his humility in the pursuit of truth, curiosity about the world, consistency in avoiding rash actions and courage in the face of new challenges. His studies in 1491–1495 in Kraków had a profound impact on his scholarly career, and his most famous work, as stressed by Professor Marcin Karas in the issue’s opening interview, has its roots in Kraków. Professor Krzysztof Stopka writes about the thriving liberal arts school at the University of Kraków and the open-mindedness of young Copernicus’ teachers, while Reverend Professor Michał Heller, in a published fragment of his latest book Nicolaus Copernicus’ Theory of Relativity, emphasises that ‘in his work, Copernicus’ pioneering astronomical achievements are intertwined with his contemporary worldview on philosophy and nature’. The issue also features the fascinating story of the subsequent owners of the De revolutionibus manuscript and its way to the Jagiellonian Library told by Professor Zdzisław Pietrzyk. There are noteworthy texts about Copernicus as a physician, about the traces of his reflections in modern economic thought, about exhibitions devoted to the astronomer in the Royal Castle in Warsaw and in the Jagiellonian Library, about numerous Copernicana as well as Jan Matejko’s famous painting Astronomer Copernicus, or Conversations with God owned by the Jagiellonian University.

I encourage you to read on, and I hope that the articles published in this issue of Alma Mater, together with more than 250 unique illustrations sourced mainly from the Jagiellonian Library and Jagiellonian University Museum, are a fitting commemoration of Copernicus’ life and work, presenting interesting insights into his biography and showing him in a new light.

I would also like to believe that the knowledge contained in this issue will intrigue the Readers and become an inspiration for creative endeavours in various fields. Maybe it will even give them an idea for a new research project and entice them to solve some mind-boggling research mysteries? As we have learned from Copernicus, everyone can become a discoverer, provided they have no shortage of passion…

Rita Pagacz-Moczarska

He stopped the Sun and moved the Earth

To mark the 550th anniversary of birth and the 480th anniversary of death of the great astronomer, who in his work De revolutionibus orbium coelestium presented the framework of the heliocentric model of the Universe, thereby shattering the commonly accepted view of the world, the Senate of the Republic of Poland has proclaimed 2023 as the Year of Nicolaus Copernicus.

To celebrate this occasion, the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, Jagiellonian University in Kraków, and University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn, together with the Polish Academy of Sciences Institute for the History of Science have organised the World Copernican Congress in Poland. They aim to present the current state of research on the life and work of the eminent scholar and his influence on the development of science, culture and art. The official opening of this unique event took place on February 19, 2023 in Toruń, on the anniversary of the birth of Nicolaus Copernicus. International debates attended by historians, culture experts, literary scholars and art historians interested in discussing Nicolaus Copernicus’ place in culture as well as astronomers, historians of astronomy, specialists from the field of medical sciences, economists, philosophers, and historians of these disciplines were held in Toruń, Kraków, Olsztyn and once more in Toruń.

Issue co-funded by the Minister of Education and Science and the Ministry of Education and Science

Minister Edukacji i Nauki Ministerstwo Edukacji i Nauki

Copernicus’ work has its roots in Kraków

An interview with Professor Marcin Karas from the Department of Polish Philosophy of the Jagiellonian University Institute of Philosophy by Rita

Pagacz-Moczarska

□ Professor, in you book Nowy obraz świata. Poglądy filozoficzne Mikołaja Kopernika [A new image of the world. The philosophical views of Nicolaus Copernicus] published in 2018 by the JU Press, you write that the great scholar is numbered amongst the most famous scientists in our culture. It seems that everyone in the world has heard about the genius of Nicolaus Copernicus. Why is he so extraordinary?

■ To learn about Copernicus, one needs only to look at the introduction to the first book of De revolutionibus. Although it’s a rhetorical text aimed to prepare the reader for reception of the work, reading between the lines it can also be seen as a kind of intellectual autobiography: how the astronomer saw himself, how and in what conditions he carried out his research, and what his conclusions were.

Surprisingly, he kept to himself and did not engage in research in his everyday life. He managed the funds of the Warmian cathedral chapter, he fulfilled the duties of a canon, lawyer, physician and economist; he even dabbled in security and defence. He was a practical man. The astronomical discovery for which he is the most famous and which has earned him his recognition was the result of his spare time activities. He wasn’t a professional astronomer: he hadn’t worked at any university, he hadn’t been part of the academic community, he hadn’t given any lectures; he had contacts with scholars because of his interests. And it was precisely because of this freedom as well as the amateur and solitary nature of his work that he was able to keep his thinking fresh and out of the box. It’s worth to mention that he was also interested in mathematics, physics, history, cartography, philology, astrology and philosophy. So his extraordinariness is to a large extent based on contrast: that such a modest person, largely unknown in the scholarly community and living in Frombork, where there was no academic presence, managed to make such a monumental discovery.

6 alma mater No. 243

Portrait of Nicolaus Copernicus by Jeremias Falck, 1644

From the collection of the Jagiellonian Library

If Copernicus was a professor of our Kraków University, or other prestigious institution such as one of the universities in Paris, Padua, Bologna, Naples or Cologne, it could’ve been reasonably expected that such a discovery would’ve eventually come. What is more, it would’ve been safe to presume that he would’ve created more works describing even more discoveries. As it stands, there was only one book, published after long deliberations, since its author needed to be sure his reasoning was sound and provable.

□ There have been many discussions on Copernicus’ nationality. What do historical sources say? What proof do we have that he was Polish?

■ That’s a very good question. There’s a lot of superficial information on this subject to be found on the Internet. It could be jokingly said that probably every country would in some way like to, directly or indirectly, place Copernicus among its citizens and somehow prove his relationship with it. The Danish would like to see him as the predecessor of astronomer Tycho Brahe, the French – as the successor of Bishop Nicole Oresme, the English – as a precursor to Thomas Digges, who explored the heliocentric theory, the Italians –as a student of Domenico Maria Novara da Ferrara, and the Greeks – as a faithful follower of Bessarion. The Germans started to make claims that Copernicus belonged to their nation in the 19th century, when the Polish state ceased to exist due to partitions. Previously,

they had no doubts he was a Pole. The historical facts that need to be borne in mind unequivocally confirm that Copernicus was Polish.

It is widely known that the concept of ‘nationality’ was understood differently than it is today. That’s why, when carrying out research on Copernicus’ national identity, I first set up a number of criteria related to ethnicity, language as well as social and political issues, and then checked how Copernicus fit into them. As far as ethnicity goes, the Copernicus family came from Silesia. The area where they lived in the 14th and 15th century was dominated by the Polish. Though the name Copernicus (Kopernik) is of German origin, the family was of Polish ancestry from both the father’s and the mother’s side.

Even though Copernicus wasn’t recorded to ever have said ‘I’m Polish’ or ‘I’m German’, research by linguist Professor Stanisław Rospond very clearly shows that Copernicus made mistakes in German texts, while he wrote correctly in Polish (when writing down names). It points to the fact that he was more familiar with Polish than German.

Toruń, where Copernicus’ parents settled down, was a multilingual town, but Poles constituted a large part of its inhabitants. As I mention in my book, in the 15th century there were five churches in the town: in three of them, sermons were delivered in Polish, in the other two – in German. So there was a noticeable majority of Poles there. Besides, when the Polish King Casimir IV Jagiellon –who negotiated what is now known as the Second Peace of Toruń

7 alma mater No. 243

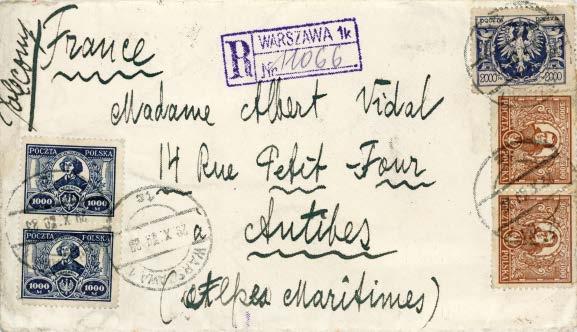

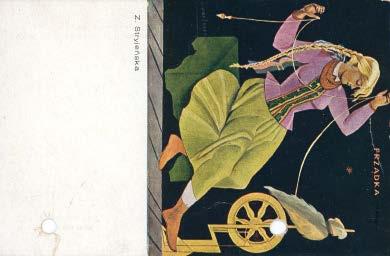

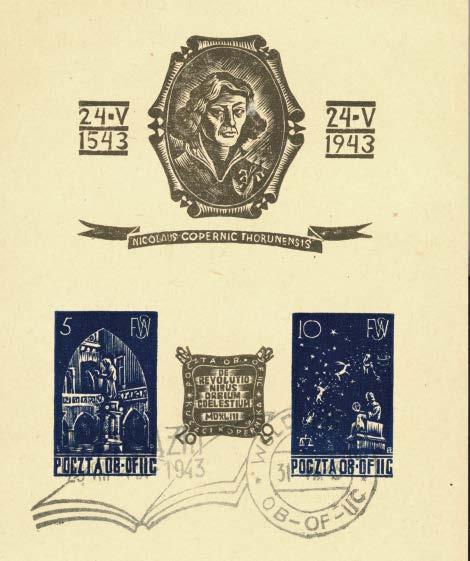

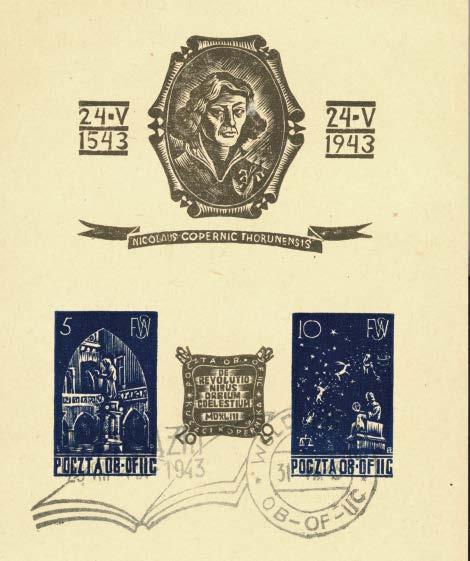

From the collection of the Jagiellonian Library

Nicolaus Copernicus with his predecessors and successors, listed from left to right as: Tycho Brahe, Ptolemy, Newton, Hipparchus, Laplace, Wojciech of Brudzewo, Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler, Jan Śniadecki, Bradley, Hevelius, Egyptian astronomer, Czau-Kong, Moses, Indian astronomer. Jan Styfi, Warsaw 1872

with the Teutonic Order on October 19th, 1466 in Artus Court – frequented the town, representatives of the town council spoke with him in Polish. So despite what some Germans might be saying, Toruń was not a Hanseatic, Germanic town. The Polish heritage of Copernicus’ parents is also confirmed by the fact that, being very religious, they joined the Third Order of Saint Dominic, but not the one operating at the Toruń convent, which at the time was aligned with the Teutonic Order; instead, they chose the Kraków monastery. Copernicus surely spoke Polish both at home and at school, including his time at Kraków University.

In Warmia, when settling peasants on the lands belonging to the cathedral chapter, he wrote down their names phonetically, with Polish pronunciation and spelling, as no German would’ve done. He always signed his own name in either Polish or Latin, never in German. Additionally, when he treated Georg von Kunheim the Elder, he wrote letters in German to Duke Albrecht Hohenzollern, making simple mistakes that according to Professor Stanisław Rospond were caused by the fact that Copernicus used it as a non-native language.

When it comes to political identity, Copernicus favoured neither the Teutonic Order not the Germans. He never felt close to any German duchy. He never travelled to Germany, though his bust is included in the pantheon of famous Germans at the Walhalla memorial in Donaustauf. Instead,

he always sided with the Polish King Sigismund I the Old, whose reign (1506–1548) came during the times of Copernicus’ professional career. The author of the heliocentric theory was loyal to the Polish king, as he represented his interests in Warmia. When addressing the king on behalf of the Warmian chapter, he called him ‘our monarch’. Poland was Copernicus’ homeland in the broader meaning of the word; in the narrower sense, it was Royal Prussia. He became a Prussian by choice and supported his fellow countrymen, working towards the economic prosperity of Warmia, but always in a close relationship with Poland. There’s also much evidence that in 1504–1530, during regional assemblies in Royal Prussia, he served as a translator for Polish officials who performed their duties at the behest of the Polish king.

So, in every possible way of understanding the concept of nationality, both past and present, Copernicus was Polish.

□ Another proof of his everyday use of the Polish language is the fact that his servant was a Pole named Wojtek Cebulski…

■ It was either Cebulski or Szebulski. Indeed, Copernicus must’ve spoken with him in Polish, since the boy came from a Masovian village and couldn’t have spoken German. Interestingly, in German historiography Cebulski is called Albert in order to cover up his true ethnicity. Copernicus also spoke in Polish with peasants coming to Warmia from Masovia. They also couldn’t have spoken German, and Copernicus had to talk to them in detail about farming issues as well as their rights and responsibilities. In Olsztyn, together with Zbigniew Słupecki, who only spoke Polish, Copernicus organised the defence of the town against the Teutonic Order.

□ Copernicus’ father, also named Nicolaus (about 1420–1483), was a merchant who came to Kraków as a young man. His mother, Barbara (about 1440–after 1495), came from the family Watzenrode. Where exactly did his ancestors come from?

■ The Copernicus family came from the village of Koperniki, located in the powiat (district) of Nysa, near the border with Czechia, close to Opawa Mountains. Even today, in the village there stands a church dedicated to St. Nicholas – though not the original one from the times of Copernicus, but one built later by a German architect in the late 19th century, when the settlement belonged to Germany. When the Copernicus family lived there in the 15th century, the village’s population was ethnically Polish. Based on the names of other places in the area, we can assume that the majority of people were Polish. It was later that German settlers arrived and the region gradually became Germanised. The Copernicus family moved around to various regions in the south of Poland, in particular Nysa, Wrocław, Kraków and Toruń. The astronomer had many Polish relatives, such as his grandmother Katarzyna Modlibożanka and members of the Konopacki, Kostka and Działyński families. Copernicus’ father lived in Kraków, then

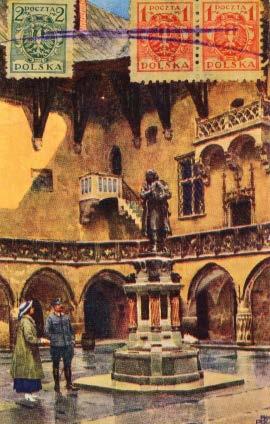

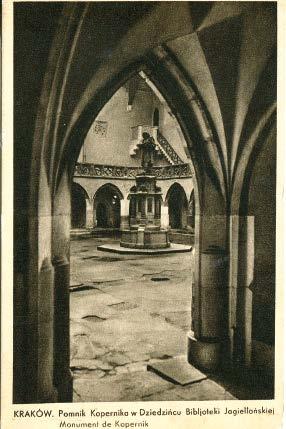

8 alma mater No. 243

Portrait of Łukasz Watzenrode (1447–1512) – a doctor of canonical law, bishop of Warmia, diplomat and patron of the arts and sciences. A copy from the collection of the Nicolaus Copernicus’ House in Toruń

Public domain

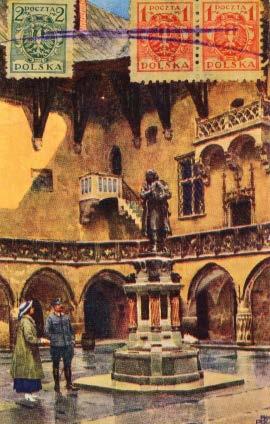

Nicolaus Copernicus’ father – a painting from the 17th century, author unknown

From the collection of the Jagiellonian University Museum / Janusz Kozina

became a copper trader and moved to Toruń, which turned into an important trading hub after Poland regained it from the Teutonic Order, as the Vistula River was the main waterway for transporting goods to Gdańsk and further west. In Toruń, he married Barbara Watzenrode, who probably came from Świdnica. The family of Nicolaus’ mother who lived in Toruń was also Polish-speaking.

□ Copernicus had three siblings: two sisters, Barbara and Katarzyna, as well as a brother, Andrzej, with whom he travelled to attend the university in Kraków. What do we know about Nicolaus’ brother and sisters? Did he stay in touch with them?

■ Questions related to Copernicus’ siblings weren’t in the scope of my research. Details on that can be found, among other works, in Jerzy Sikorski’s book Prywante życie Mikołaja Kopernika [The private life of Nicolaus Copernicus]. We know that his brother Andrzej, also a canon of the Warmian cathedral chapter, later fell ill with leprosy, which he’d contracted while in Italy, and soon died as a consequence. Katarzyna married Bartłomiej Gaertner of Kraków and had five children. Barbara joined the Cistercian monastery in Chełmno.

□ After the death of Nicolaus’ father in 1483, the family was looked after by his mother’s brother, the Warmian bishop Łukasz Watzenrode (1447–1517), who had the reputation of a very strict man. It was his idea to send both of Barbara’s sons, Andrzej and Nicolaus, to study at the University of Kraków in 1491. When he arrived in the city, Nicolaus was not yet 19 years old. Which lectures at Kraków University had the greatest impact on his further academic career?

■ I suspect instead of lectures on economics, law and medicine, he was most interested in the philosophy of science as well as astronomy, discoveries and cosmology.

Kraków University was an ideal place for Copernicus, most importantly because he could be schooled not only in observational and theoretical astronomy, but also philosophy. Unfortunately, not many researchers focus on this issue. One of the greatest experts in the Polish philosophy of the late Middle Ages was the medievalist Professor Mieczysław Markowski. I had the honour of him being the reviewer of both my PhD and habilitation theses. That great scholar carefully examined the background of Copernicus’ life by reading manuscripts found at the Jagiellonian Library that had not been previously studied by anyone. This project resulted in a phenomenal book, Burydanizm krakowski w okresie przedkopernikańskim [Cracovian Buridanism in the pre-Copernican period], which contains about six hundred pages. Unfortunately, it was only published in a limited number of about five hundred copies. Maybe now, during the Year of Nicolaus Copernicus, somebody will provide the funding necessary to publish it again, this time in more copies… For me, it was the fundamental reading matter during my research on Copernicus in Kraków. Professor Markowski posited that at Kraków University, philosophy was taught in a very open way, in particular when it came to natural philosophy. There were many schools of thought which complemented each other through discussion. Scholars debated the philosophy of not only John Buridan, but also Thomas Aquinas, Albert of Saxony, John Versor, Giles of Rome and William of Ockham. Other European

universities tended to focus on one of these schools and there were heated debates when it came to choosing the direction for natural philosophy. In Kraków, however, professors came to a very sound conclusion that if scholars in Paris or Oxford are wasting their time discussing trifling issues, it’s better to find a common ground, via communis: a stable, shared platform which would serve to further develop philosophical thought. And Copernicus found it to be a great foundation upon which he could devise his reform of astronomy, since he saw potential in the philosophy of Aristotle. In contrast to the writings of later historians, who had no knowledge of Buridanism, Aristotelianism was not an obstacle for Copernicus. When reading Copernicus’ works in the original, one can clearly see he based his theory on Aristotle, but in the way he was perceived in the Middle Ages in Kraków, influenced by the via communis approach. Aside from Albertism, Thomism, Ockhamism and Buridanism, the astronomer used his own, shall we say, Copernican natural philosophy as a base to create the heliocentric model of the world. It turned out that it wasn’t necessary to replace Aristotle with Plato, as per Popper’s views, but rather correct him, as was previously done by Thomas Aquinas, William of Ockham, and others, particularly John Buridan and Albert of Saxony.

To prove that Earth moves, some assumptions needed to be changed. The main problem was that based on classical Aristotelianism, Earth cannot be moved, because it’s heavy and there’s no force trying to do it. Heavenly spheres move because they are formed out of aether, and so they only need a ‘constant mover’ that faces no resistance, metaphysically driving them and giving them purpose. This movement is very simple, because they have no mass,

9 alma mater No. 243

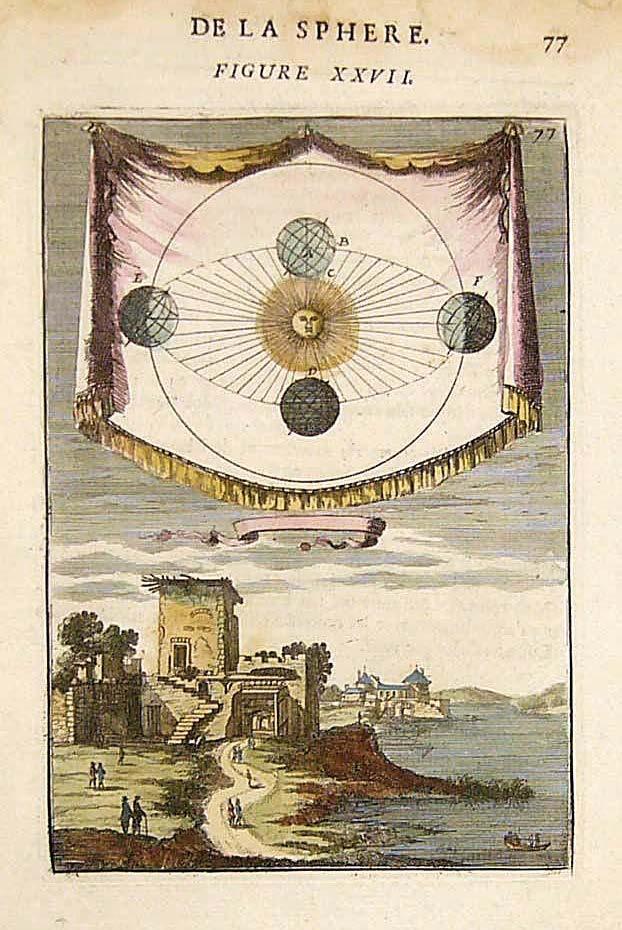

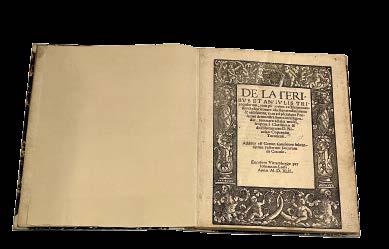

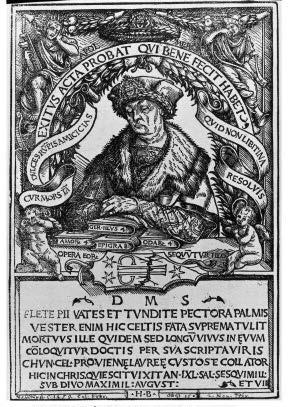

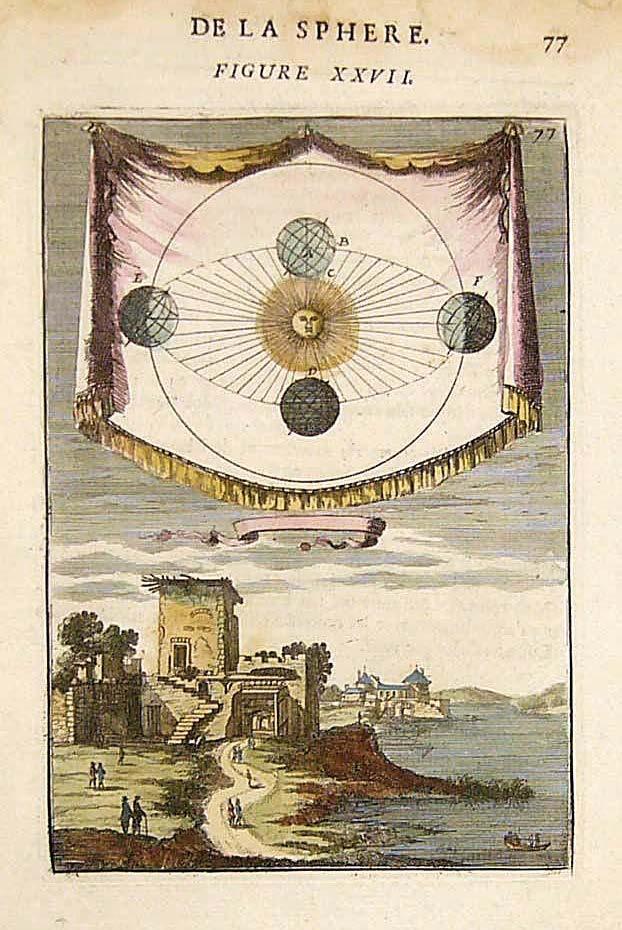

Title page of Galileo’s main work from 1635. The illustration by Jacob van der Heyden shows a discussion by Aristotle, Ptolemy and Copernicus, who in his left hand holds a representation of the heliocentric model

From the collection of the Jagiellonian Library

no weight. Earth, however, as Aristotle saw it, has no mover, and therefore must be in the centre of the Universe.

Copernicus’ saw that his observations imply that the model of the Universe would’ve been better if it had been more rational, more ordered, more elegant. It would explain more and in a simpler way, in terms of quality, not quantity, with more inner cohesion, and would be better suited to the Creator’s expectations. And that is what he decided to show. If the Creator made the world wisely, then there is no chaos, no unnecessary additions. Everything must be structurally harmonious and coherent. Additional changes need to be applied to Aristotelianism: firstly, aether needs to be removed, following Buridan’s example. The whole Universe is built out of the same four elements: earth, water, air and fire. The concept of ‘place’ needs to be altered as well. The centre of the Universe is not the natural place for Earth. Every star and every planet is round and has its own place. Places are no longer absolute, but rather relative. It can be said that Copernicus’ theory was based on a relative concept of natural places. Aristotle’s assumptions excluded the possibility of a moving Earth: it was in the centre because it was natural. And Copernicus said: ‘Every planet is in its own natural place, and since other planets move, Earth must also be doing so. Even the Sun could be moving, though it does not have to, but if there is a centre, something should be in it. And it is the most fitting for the Sun to be at the centre, just as we hang a lamp in the middle of the ceiling’. These are very basic examples, but they are in accordance with the Aristotelian spirit. A healthy dose of empiricism, kept under control by speculative theory. The Sun shines equally on the entire Universe if it’s in the middle. If it was in a more peripheral place, its light wouldn’t be distributed evenly. Planets are brighter when they are close and darker when they are far – a simple observation. Copernicus observed that there must be three types of Earth’s movement: daily motion, yearly motion and precessive motion. All of this works only if one modifies the concept of element, which is what Buridan did, and the concept of place, which is what Copernicus did. One more scholastic comment on Aristotle, if you will.

□ So could one be compelled to say that Copernicus’ work is strictly Cracovian in nature?

■ Even if Copernicus wouldn’t have said that Kraków University is his alma mater in the intellectual sense, such conclusion might be made on the basis of his writing. In all his deliberations on Aristotle, he writes about physics as a foundation for astronomy. The essence of these considerations is Cracovian. It’s as if he discussed this with someone in Kraków. And although Copernicus worked out of Frombork, he based his work on the knowledge he had gained as a student taking notes in Kraków.

□ Still, during the debate Czego nie wiemy jeszcze o Koperniku [What we don’t know about Copernicus], which took place in November 2022 in JU Auditorium Maximum within the

framework of Big Questions in Kraków, when one person asked: ‘Where did Copernicus make his great discovery?’, most panellists were of the opinion that it must’ve been in Italy…

■ I daresay that might not necessarily be the case. Copernicus might’ve thought of the idea when he was still in Kraków. He may have looked for more proof in Italy, but he was already convinced that Kraków shaped him as an astronomer, and I’m sure that when leaving for Italy, he had the basic idea of the heliocentric theory, especially since he described the first model of this theory in his short work Commentariolus (Little Commentary) as early as the first decade of the 16th century, a short while after his studies in Kraków.

□ And what role in Copernicus’ scholarly development was played by Kraków University professor Wojciech of Brudzewo, also known as Albert de Brudzewo or Wojciech Brudzewski, an eminent representative of Kraków school of mathematical and astronomical thought, who had had already stopped teaching astronomy at the University, but instead passionately told students about the philosophy of Aristotle? What influence could he have had on young Copernicus?

■ To my mind, enormous. But to confirm it would require more research into manuscripts found at the Jagiellonian Library. An interesting paper entitled La critique de l’univers de Peurbach développée par Albert de Brudzewo a-t-elle influencé Copernic ? Un nouveau regard sur les réflexions astronomiques au XVe siècle [Did the critique of Peurbach’s universe developed by Albert de Brudzewo influence Copernicus? A new look at astronomical reflections in the 15th century] was published by Italian researcher Michela Malpangotto in Almagest, International Journal for the History of Scientific Ideas in 2013. In that paper, she proved that there’s a direct influence of Brudzewski’s writing on Copernicus, and it’s a positive one. Copernicus has drawn a lot of inspiration from the works of that scholar. This is because Wojciech of Brudzewo asked himself questions that bothered all philosophers of the late medieval period: ‘How to reconcile two different geocentric models of the Universe? How to reconcile Ptolemy with Aristotle?’. And Copernicus did it! To simplify a bit, it can be said that Copernicus’ work is at the same time the last gasp of medieval science and the first cry of Renaissance science. Proponents of Scholasticism demanded a reconciliation between Ptolemy and Aristotle. It’s not good when there are two similar models that differ in some aspects, when the beautiful Universe is described in two ways. Brudzewski wanted to reconcile these two concepts and conceive of a coherent theory. In his 13th century commentary to Aristotle’s view of the heavens, Thomas Aquinas also said there were two models and there might be a third one in the future.

Wojciech of Brudzewo tried to find out who erred – was it Ptolemy or Aristotle? – and correct him. He criticised the concept of equant (equant point) and various issues related to geometry. He asked questions, but couldn’t find the answers. And then all these

10 alma mater No. 243

Wojciech of Brudzewo

From the collection of the Jagiellonian University Museum

questions and arguments gathered by Brudzewski were used by Copernicus, who in that sense was his ‘student’. He didn’t necessarily need to listen to Brudzewski’s lectures. It’s enough that he read his notes, commentaries or books, and talked to people Brudzewski had taught at the University of Kraków. Copernicus knew that Brudzewski set the task of ‘fixing astronomy’, and the pope – of ‘fixing calendar’. And so, he worked on these problems and found the solution.

□ Why did Wojciech of Brudzewo disappear in Copernicus’ shadow?

■ He shared the fate of John Buridan, Nicole Oresme and Nicholas of Cusa. Copernicus’ discovery was so great – one of the greatest in human history – that it overshadowed the achievements of other distinguished scholars. When the Sun shines in the sky, no planet is visible. Though they are all there, one cannot see them, because the Sun is too bright. Copernicus made such a breakthrough in all aspects of life that the others are simply overlooked, even though they directly or indirectly helped him. That’s the way of the world: when someone achieves something truly great, something revolutionary, then the others who came before receive less recognition.

□ Where could have Nicolaus lived during his studies in Kraków?

■ Students from Royal Prussia lived in dormitories, such as the Dormitory of the Poor (Bursa Pauperum), Philosophers’ Dormitory (Bursa Philosophorum), Jerusalem Dormitory (Bursa Hierusalem), Hungarian Dormitory (Bursa Ungarorum) and German Dormitory (Bursa Theutonicorum). Were the brothers Nicolaus and Andrzej

among them? We’ve no idea. According to some researchers, it’s highly probable that the brothers lived in the Jerusalem Dormitory, which used to be located in ul. Gołębia (Gołębia street). Some speculate they might have lived in ul. Kanonicza (Kanonicza street), in the house of nobleman Piotr Wapowski, a friend of their uncle Łukasz Watzenrode. This seems all the more likely because later Nicolaus became a friend of Piotr’s nephew, Bernard Wapowski, with whom he exchanged letters, for instance about the movement of the eighth sphere.

□ During the aforementioned debate (What we don’t know about Copernicus), you stressed how extremely important for learning the details about the life and discoveries of the famous astronomer is the study of source texts, which should be also read between the lines. You emphasised that Copernicus should be discovered through various contexts. So, reading between the lines – since Copernicus didn’t write any footnotes – and taking into account various contexts, is it possible to determine what books he made use of while reinventing the image of the world?

■ He could’ve made use of an entire collection of canonical works available to astronomers and cosmologists, including De sphaera mundi by Johannes de Sacrobosco, synopses of Ptolemy’s Almagest (a treatise in thirteen books containing comprehensive astronomical knowledge of that time period and a mathematical explanation of the geocentric theory) written by Georg von Peurbach and Regiomontanus, and astronomical tables from Spain. Professor Ludwik Antoni Birkenmajer travelled around the world – including, naturally, to Uppsala – to gather records of Copernicus’ collection of books and his research. Copernicus faced a very difficult task, as he concluded that it wouldn’t be possible to reform astronomy after

Feliks Sypniewski, Mikołaj Kopernik wykłada swą naukę wobec uczonych krakowskich w r. 1509 [Nicolaus Copernicus lays out his theory to Kraków scholars in 1509], woodcut, Warsaw, 1870s. Drawing published in Tygodnik Ilustrowany weekly No. 269 from February 22, 1873, devoted to the memory of Nicolaus Copernicus on the 400th anniversary of his birth

From the collection of the Jagiellonian Library

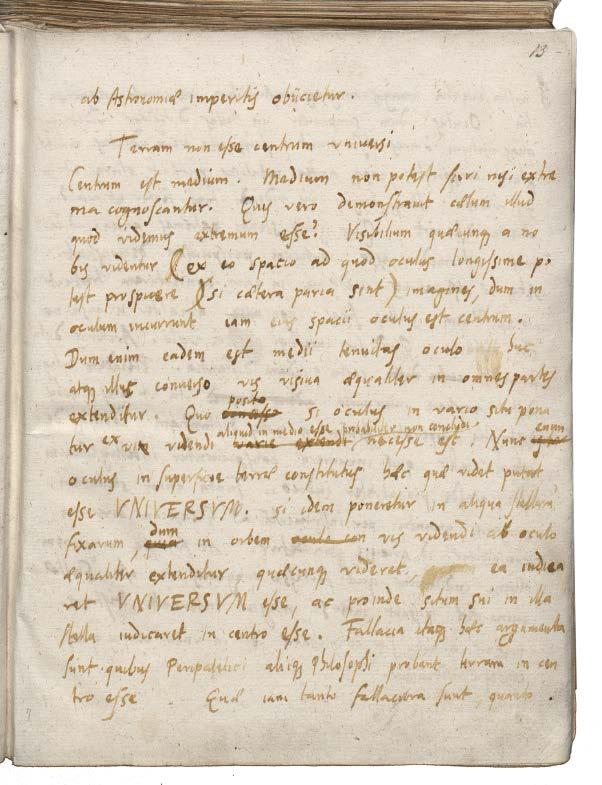

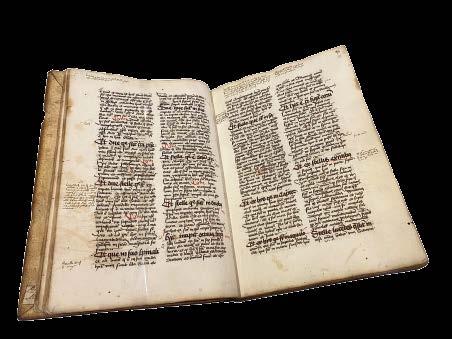

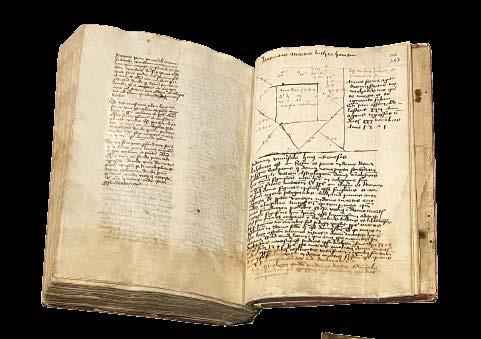

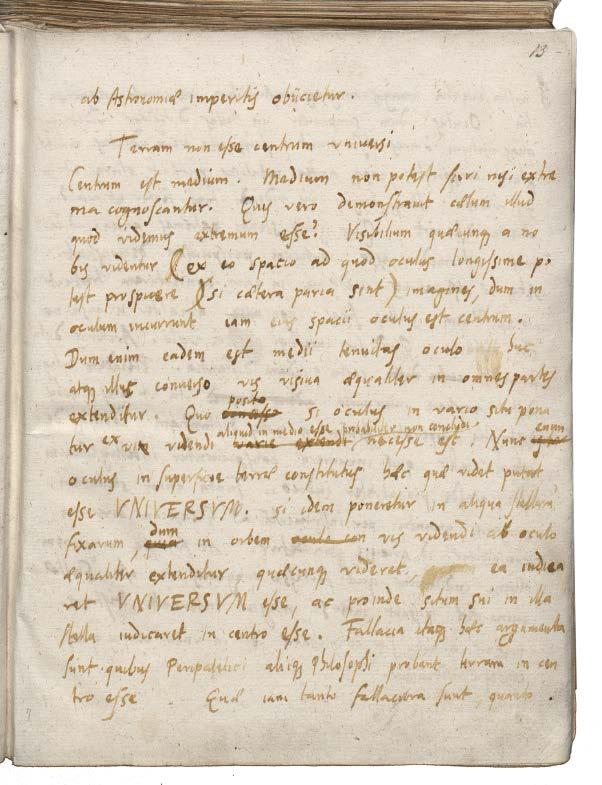

Page form Vitello’s 13th-century work on optics entitled Vitellionis mathematicii doctissimi peri optikis id est de natura, ratione et proiectione radiorum visus, luminum, colorum atque formarum quam vulgo Perspectivam vocant Libri X, Nuremberg 1535. Originally belonging to Nicolaus Copernicus

taking just one look at the sky, because in that case, one only had the knowledge of its current state. Some celestial bodies move very slowly, others have long-period movement that makes it impossible to predict the geometry of their passage during the course of one lifetime. Hence, Copernicus’ had to collect records of all medieval and ancient observations, compare them as best as he could with his own conclusions, and only then perform calculations.

One has to bear in mind that Copernicus had no specialised optical equipment to carry out his research, just simple wooden rulers and a brass astrolabe which he used to measure the angles between bright dots in the sky. He wanted to know how the regularly moving dots had looked like a few thousand years ago. The problem was, as proved by Birkenmajer, that all available literature was devoted to the Egyptian calendar. So even if some information about the Sun, an eclipse or the position of a particular planet had had been recorded somewhere, and Copernicus read it, at first it would have meant nothing to him, because it was based on the Egyptian calendar. He first had to translate it to the Christian calendar. He had to put in an enormous amount of work to, for instance, learn how the Egyptian calendar looked like and how the months were called (and they were called differently in every manuscript), then determine which date an ancient astronomer had had in mind, and only then find the correct date in the Julian calendar, which was the norm in his times. Afterwards, he could calculate how many years,

months, weeks and days passed between the observations, put it all into one model and finally determine the mechanics of a particular movement. When carrying out this partly scientific, partly detective work, he acted like a good historian: he collected all available sources and studies and attempted to find patterns. And then he built his model on the basis of that. Copernicus was not primarily an observer. He chose what to observe, because he already knew what to look for thanks to the records left by his predecessors, and he wanted to know what had changed since their times. It’s a very interesting approach: astronomy based on history rather than observation.

□ So the ground-breaking discovery wasn’t based solely on observations of the sky, but also on reading the works of his ancient and medieval predecessors?

■ Yes. Copernicus said that one needs to look at reality with both eyes, meaning one needs to observe, but make use of knowledge, and experience the world empirically, but based on reason. It’s an Aristotelian proposition. Texts contain theory, but observation is empiricism. Plato, though, would probably not be so inclined to observe things. For him, mathematical speculation was more important. Since the world is made up of shadows, one needs to look at their source – ideas – instead of reality. However, Copernicus stayed true to Aristotle’s postulate that theories are tested with observations, and observations are explained with theories. If one follows this principle, then theories can very closely adhere to reality. This was stressed chiefly by Thomas Aquinas. So it could be said that Copernicus was in some sense a Thomist. Some versions of Aristotelianism became a bit blurry when it came to established concepts, so I think that on the spectrum of all the possibilities, Copernicus was not only a Buridanist, but Thomism was also close to how he viewed reality. This was basically his own philosophy. So in this sense, he’s the precursor of modern science; not of various positivist approaches, but rather those related to metaphysics, which contain a bit of the speculative element.

It’s worth to point out that some books simplistically state that Copernicus read Greek originals because Latin translations were poor. That is not true. To learn about the structure of the Universe, he required only the Latin synopses of Almagest written by German astronomers nearly one hundred years earlier. He based his work on Latin sources and later, when his only student Georg Joachim Rheticus bought him the Greek original as a gift, he compared the two and saw that he was right.

□ What else can we read between the lines when analysing Copernicus’ works?

■ Something that might surprise a lot of readers: respect for tradition. Copernicus is often spoken about as a revolutionary who had to destroy everything and build something new in its place. In truth, no one reading his work will find a single mention of revolution. In his book, Copernicus says he will paint a new, better picture, but he will essentially do it using the old ways and old tools. He draws from tradition, which he respects along with his predecessors, whose works he had read with great care. He doesn’t say they are silly and fool their readers, but instead shows that science is constantly developing, accumulating more and more information, and at a certain point it becomes necessary to rebuild everything, because old information can be interpreted in new ways.

12 alma mater No. 243

From the collection of the Uppsala University Library

He acted very similarly as an administrator. When he arrived at the Warmian cathedral chapter and saw that fields were not being tended due to war, he didn’t blame his predecessors and accuse them of negligence. He didn’t complain or cry in outrage, but instead invited peasants from Masovia and parcelled out the land. He encountered a problem and set out to find a solution.

Likewise, as Poland regained Royal Prussia from the Teutonic Order after the Second Peace of Toruń, he didn’t complain that participants of regional assemblies were unable to communicate because some of them spoke Polish and some German, but instead travelled to these gatherings and translated from one language to the other.

He had the idea that coins should be minted bearing not only the Polish coat of arms, but the Prussian one as well, so that Prussians would feel connected to both Kraków and King Sigismund I the Old. He promoted local patriotism. He made sure the price of bread was reasonable and that Olsztyn had a sufficient reserves of gunpowder in the face of a Teutonic attack. He negotiated the amount of the gunpowder with a Polish commander. On that occasion, he also learned how to operate a cannon, and later, when writing De revolutionibus, he used expressions such as ‘sudden ejection of a charge by rapidly burning gunpowder’. He saw that during military exercises. He saw what Newton later described as angular momentum. He wanted to show his readers that physics is related to movement.

□ Copernicus was undoubtedly a hard-working, conscientious, consistent, curious and modest scientist. What else can be said about him as a person?

■ Based on what the astronomer himself said, on what his student Georg Joachim Rheticus recorded, and on the opinions of his contemporaries, we can say quite a lot. He was a solitary man when it came to science, he carried out his research by himself, but he was by no means a loner: when he travelled to assemblies, he enjoyed the company of other people. He felt fulfilled as a physician. He didn’t argue with people. He was neither vainglorious nor arrogant, he didn’t make people around him nervous. He had clear, concrete ideas. He was modest, as he never put himself before his research. He made a great discovery, but had the humility to notice the achievements of many great scholars who came before him and from whom he learned so much.

He was very patient and persistent. He put off the publication of his work until he was sure he checked everything, and published it after Rheticus’ arrival in Frombork, when he understood that he could find no more arguments.

Naturally, there is much literary oversimplification. Some people would like to see Copernicus in a more dramatic light, so they portray him as pushed off to the edge of the world, where he still managed to become successful and make his discovery. But he lived in Frombork because of his work. If he lived in Kraków, he probably would’ve reformed astronomy as well. Indeed, he made calculations and wrote his observations on the basis of the Kraków meridian, so Kraków was always a place close to him. Not German universities, but the University of Kraków.

□ He must have been a man of great resolve, strength and bravery, since he defied his domineering uncle and refused to become ordained…

■ Copernicus found a way to get along with him. At first, he did what his uncle told him, but later he came to value his independence.

□ And what about Anna Schilling? Who was she to Copernicus?

■ I didn’t investigate this issue, because I don’t like being sensational.

□ Copernicus’ life got more complicated when Johannes Dantiscus, a schemer and manipulator, became the Bishop of Warmia. Copernicus became the target of denouncing letters, some of which were written by Feliks Reich. The main reason behind them was the issue of Anna Schilling. In a letter to Dantiscus, Copernicus wrote that he hadn’t had send her away since it was difficult to cast aside a person who was not only a good cook, but also a relative… He promised to resolve the matter, but put it off for several years! Why did he ignore Dantiscus’ reprimands for so long and reacted only after the threat of a canonical trial in Frombork?

■ It shows how much freedom he had. Clearly he wasn’t under much pressure, since for many years he was able to tell the bishop: ‘I’ll do it, but not just yet’.

It must be remembered that a canon was a bishop’s associate and the latter didn’t have absolute power over the former. The next

13 alma mater No. 243

Astronomical tables with Copernicus’ handwritten notes, known as the Uppsala Notes

From the collection of the Uppsala University Library

bishop was chosen from a group of canons. So these reprimands should be taken with a grain of salt and seen more as reminders from one colleague to another.

Speaking of the denunciations, there’s one interesting issue which shines a light on another Copernican legend. It’s often said that Copernicus was criticised for his theories and that he was afraid to publish them. Well, he wasn’t afraid, he just wanted to be sure. If his theories had been frowned upon in his time, then aside from the issue of Anna Schilling these denouncing letters would’ve contained accusations that Copernicus was spreading dangerous concepts, which were already known from his Commentariolus from 1507–1510. And yet such accusations weren’t made. So it wasn’t a problem.

□ Why did Copernicus wait thirty years before publishing his ground-breaking work, De revolutionibus? Why did he delay it for such a long time?

■ It took a lot of gruelling work to compare all the tables, make the calculations and compile it all into a uniform system. He needed to make long observations of the Sun. He wanted to spot Mercury, and that was very hard to do, because it is possible either shortly after sunset or shortly before sunrise, very close to the horizon. Frombork was often shrouded in fog, so he had to wait a long time for a good opportunity to gather his observations in one place and make sure his calculations were correct. Some traces of his observations of the Sun remain visible to this day on a wall in Olsztyn. He ordered a special wall to be built, on which he marked the position of the Sun throughout the seasons. He wanted to collect as much information as possible and test his model as much as he could. He didn’t want to be ridiculed for proposing a completely new image of the Universe without proper empirical arguments.

He looked for empirical proof, and yet there was none. The most basic way of confirming his theory would be to mark the movement of Earth in relation to the stars: the annual parallax. Closer stars are in a different position in relation to their background in January than in June. They move, because sometimes Earth is on one side of the Sun, and sometimes on the other. This is called an annual parallax. It was first observed in the mid-19th century, and it’s the easiest method of verifying the heliocentric theory. If one posits that Earth is moving, then it would be good to show it. If one cannot show it, then it would be good to explain why.

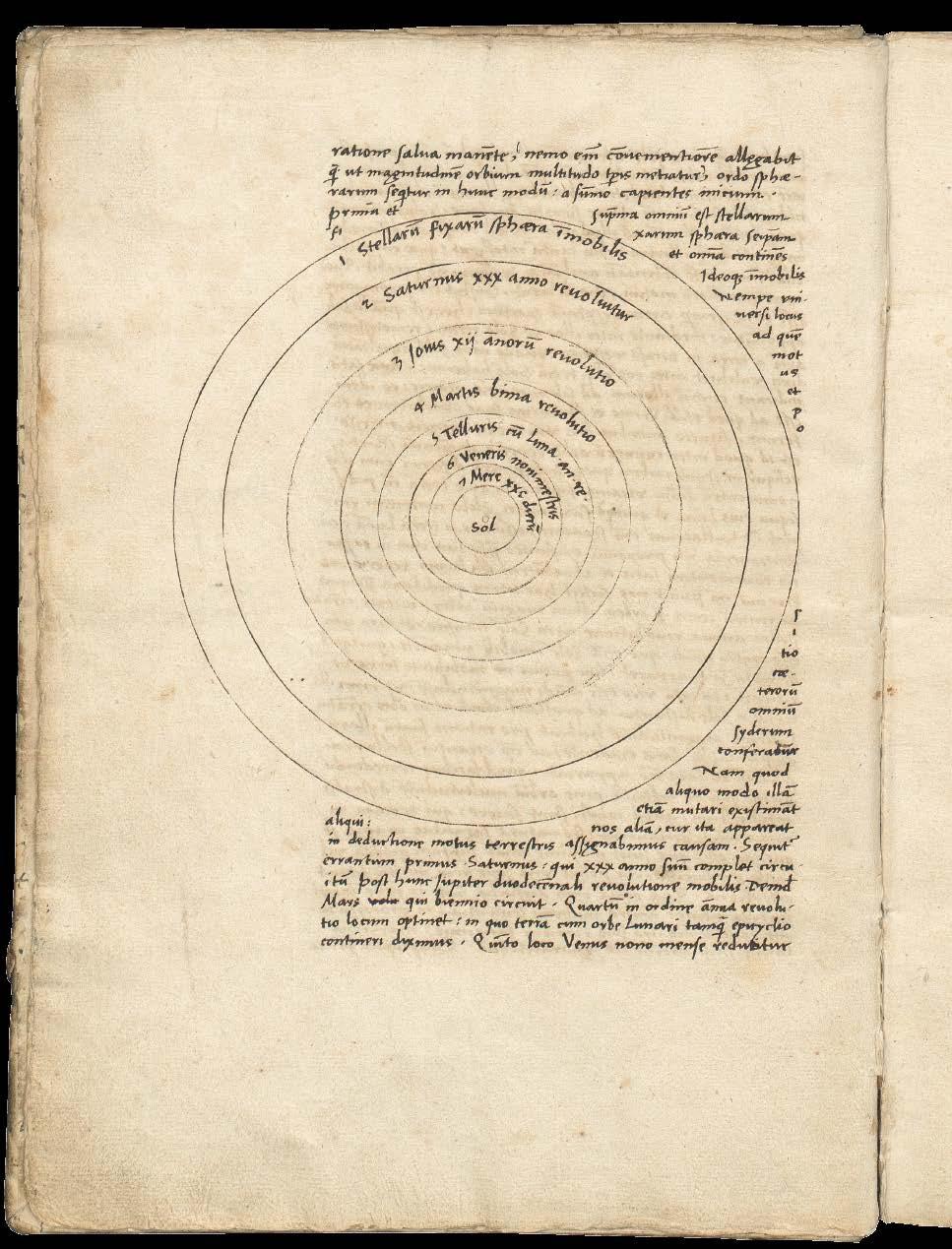

It’s because Earth is so far from the stars that the shift is virtually impossible to notice. It’s a rational conclusion, of course, but it leads to a very serious problem, specifically with the drawing Copernicus put in De revolutionibus after the tenth chapter of book one. In the drawing, the Sun is in the centre. Other planets – Mars, Jupiter, Saturn etc. – encircle it. And then, at the edge, the gap between Saturn and the fixed stars is just the same in width as in the case of other planets. And so, the Universe seems beautiful, everything is in order.

However, if one looked closer – and every talented astronomer or cosmologist would’ve been able to follow this reasoning – then it would turn out that if that gap was equal to the others, the annual parallax should be observable. And so if Copernicus claimed it couldn’t be seen because the stars are too far away, then there is a vast amount of space between them and Saturn. I have made my own calculations in line with modern astronomical knowledge: the closest star is 270,000 times further than Saturn. Let us imagine that due to much less precise equipment Copernicus would’ve underestimated this figure tenfold and assumed that the closest star is 27,000 times further than Saturn. If he tried to maintain that scale in a drawing on a piece of paper, he would’ve had to draw the sphere of fixed stars three houses further down the street.

And that would mean the drawing was irrational, because somebody could’ve said: ‘Right, the Universe is beautiful, but something is wrong here. The beautiful part ends at Saturn, then there is a great chasm of emptiness, and the stars are behind it. So this model is worse than then previous ones, because it cannot be represented in a drawing. Why is this great gap here? What’s it for? Why do you maintain that the Universe is rational, even though you say that somebody left here this vast space with nothing in it, which is completely irrational?’.

Copernicus couldn’t have drawn this to scale because it contradicted his assumption that the Universe was soundly, rationally, structurally and geometrically ordered. And such a great gap would violate this order, it’d be chaos, empty space with noting to put in it. Copernicus knew it, so he hesitated to share a theory that had weak spots. He wondered what people would think. I reckon he was concerned about that.

Furthermore, he probably questioned whether he’d be believed, since he wasn’t a university professor, but a canon living in Warmia. Who would’ve trusted a lone, independent scholar that lacked recognition, had no students, was never a rector, had never travelled to universities, never held any debates, and who then suddenly appeared with a finished body of work? His knowledge would’ve seemed suspicious, since he wasn’t an accomplished author.

As Copernicus struggled and hesitated, in 1539 he was visited by a young professor of astronomy and mathematics from the University of Wittenberg, a Protestant man by the name of Georg Joachim Rheticus (1514–1574), full of enthusiasm, who became his only student. He lived with the author of De revolutionibus for two years and finally convinced him by saying that if he died, all his work would be wasted. That proved to be the strongest argument for Copernicus. In 1540, Rheticus printed the introduction to his most famous work in Gdańsk, and published the rest three years later in Nuremberg.

□ How did Rheticus know about Copernicus?

■ Handwritten copies of Commentariolus were read throughout Europe, and this is what piqued the interest of the young

14 alma mater No. 243

One of the solar charts made by Nicolaus Copernicus at the Warmia cathedral chapter castle in Olsztyn

Public domain

scholar. Rheticus made a long journey to Frombork to meet the mysterious figure behind the theories described in that book. He brought Copernicus new books and breathed fresh air into his studies. He told him that Commentariolus was read in Germany and Italy, that the pope knew about it, and that the calendar needs to be reformed. He also told him that he should find the courage to publish his work, because though he wasn’t well-known, people would read and understand it. At that time, Copernicus was already ailing and embittered, he was tired of it all, and the scheming involving his person wasn’t helping. Rheticus had to persuade him for many months, but in the end he succeeded.

□ In 1542, Copernicus suffered a stroke. He had nothing to lose…

■ Copernicus knew that in science, there are various types of arguments. His own argument was very weak, as it was based on elegance. It also flew in the face of empiricism, distorted Aristotle, and contradicted the Holy Scripture, reason and the senses. Think about it: when we stand, the ground doesn’t move beneath our feet, when we throw a stone in the air, it falls in the same place… Everything seems to disprove Copernicus. One of my students wrote an essay on every argument for and against Copernicus’ theory from the point of view of his contemporary physicists and philosophers. Almost virtually all of them were against. The only one in favour of Copernicus’ theory was that his model was more ordered. But the fact that something is ordered doesn’t automatically mean it’s correct.

Tycho Brahe, who lived later, had much better astronomical equipment and carried out more precise observations, still didn’t believe Copernicus, because when he made his calculations to check the parallax, he got zero.

□ Copernicus was not ordained as a priest, but was inducted into the ranks of the minor orders of the Church as a subdeacon in 1496, probably by his uncle Łukasz Watzenrode when he was the Bishop of Warmia. A year later, he became the canon of the Warmian cathedral chapter. How important was the role of faith and religion in the shaping of Copernicus’ scientific thought?

■ Very important. Copernicus himself said that he will carry out his studies by the grace of God, that God planned the world wisely. Being a canon, he recited psalms, sang in a choir, and was an earnest participant of the holy mass. He was never criticised for not fulfilling his religious duties. He took inspiration from his participation in liturgy. The scripture said that the wise God had designed the order of the world, that it was rational, beautiful and good, and that God had ‘arranged all things by measure and number and weight’, as the Book of Wisdom says. If throughout their lifetime someone constantly hears that the world is ordered and rational, then he doesn’t like the fact that there are two competing astronomical theories that explain it. So it’s better to turn them into one. I once asked Professor Krzysztof Ożóg, one of the most eminent Polish medievalists, about the issue of Copernicus’ membership in the Church and he told me Copernicus probably became just a subdeacon because it was sufficient for him to fulfil the role of a canon without giving him too much duties. He had a priest to celebrate the mass in

his place, he had his own altar. Was he obligated to remain in celibacy? I don’t know.

□ For nearly 40 years, Copernicus was a physician. He treated not only the wealthy such as Johannes Dantiscus and the Bishop of Chełmno Tiedemann Giese, but the poor as well. When he was 68, he travelled to the court of Duke Albrecht Hohenzollern in Königsberg following the Duke’s personal request to treat his advisor and friend Georg von Kunheim the Elder. Copernicus stayed in Königsberg from April 8 to May 3, 1541. But what do we know about his own health, aside from the fact that he suffered a stroke a year before his death?

■ I think he must’ve been in a pretty good shape if he travelled around Warmia and, I think, twice to Königsberg.

In 1541, at the bidding of Duke Albrecht, Copernicus set out from Frombork to Königsberg on a Friday before the Palm Sunday. To travel abroad during the Holy Week, he would’ve had to have a special dispensation from the chapter. He returned to Frombork on May 3. He probably rode on horseback for one or even two days. He seems to have been a vigorous man.

Besides, he probably remained in robust health, since after carrying out his observations on a roof, often on winter nights – the visibility of the sky is the greatest when the night is long and there is no dusk – he never fell ill with pneumonia. And the winters were cold back then. In the summer, nights are never fully dark, the sky is brighter and many things cannot be seen.

15 alma mater No. 243

From the collection of the Jagiellonian Library

□ From your point of view, what is the most spectacular lie about Copernicus?

■ There are several of those. One of them is that he was an extraordinary German scholar who neither spoke nor wrote in Polish. Such information is sometimes presented in German textbooks in no uncertain terms. And Copernicus wrote a lot in Polish: just take the names of the peasants whom he settled in Warmia. Another lie is that he was opposed to Scholasticism; the postulate that Scholasticism was bad and the philosophy of Renaissance was good, and Copernicus firmly stood with Italy and Renaissance thought. And yet his discovery was intellectually grounded in medieval Kraków and not what was taught in Renaissance Italy. During Renaissance, people were more interested in literature, arts and construction, and less in nature.

The case is similar with Aristotelianism and Platonism. There are numerous publications which treat Copernicus as a Platonist who broke off with Aristotle. Personally, I can see no signs of such a breakoff, and to confirm my intuition, during classes I ask my students whether they feel Copernicus’ writing is more Platonist or Aristotelian in spirit. I think I’ve never had a student that saw Platonism in Copernicus. Everyone agrees that Copernicus follows Aristotle’s thought, though in its later form, and Platonism seems more modern because many contemporary cosmologists refer to Plato, judging Aristotle’s philosophy as bad because Thomas Aquinas based his own theories upon him. This is a textbook example of antithesis and this is how Copernicus is inserted into ready-made, stereotypical categories. It’s not true that Copernicus was opposed

to Scholasticism and Aristotelianism. He was a proponent of both of those, he was shaped by them, lived by them. He merely read about them mostly in Latin, not in Greek.

□ Copernicus was interred in 1543 beneath the floor of one of the crypts in the Frombork cathedral, but for several hundred years it wasn’t known exactly where. It was only in 2005, thanks to the archaeological research supervised by Professor Jerzy Gąssowski from the Aleksander Gieysztor Academy of Humanities Institute of Anthropology and Archaeology, that the scholar’s remains were found. Three years later, his identity was confirmed by DNA tests, with samples taken from hairs found in a book belonging to Copernicus now stored in Uppsala. As a result, a second funeral was held for Copernicus in the Frombork cathedral on May 22nd, 2010. Do you think Copernicus’ grave was really found?

■ I hope so. But I can’t be sure, especially since I read the book Mikołaj Kopernik i jego świat [Nicolaus Copernicus and his world] written by Teresa Borawska in collaboration with Henryk Rietz, published by the Toruń Society of Arts and Sciences in 2014, which voices doubt about this claim. Supposedly these hairs could come from a completely random person. Researchers from Toruń fiercely attacked the results of Professor Gąssowski’s study. For me, the results seemed convincing. However, I’m not a specialist in forensic medicine, so it’s difficult for me to judge. I don’t have the tools to investigate the matter.

□ What do you think is still worth researching when it comes to Copernicus? What could one focus on to better understand and showcase his life and work?

■ I think it’s necessary to carefully study the work of Copernicus’ predecessors and the activities of Kraków scholarly community, in particular Wojciech of Brudzewo. I suspect only then it’ll become clear that Copernicus owes to the city of Kraków, Kraków school of astronomy and cosmology, and various strains of Aristotelianism much more than we’ve previously suspected. If we look closely enough, we might very well find that the author of De revolutionibus gathered as much as ninety percent of his work material during his studies in Kraków. Naturally, it wouldn’t in any way diminish his achievements. Wojciech of Brudzewo and other scholars also had access to that knowledge, so maybe they would’ve been able to build a new model of the Universe without observations if they managed collect all the records from antiquity and the Middle

Professor Marcin Karas – philosopher working at the JU Institute of Philosophy Department of Polish Philosophy. He served as the Dean of Faculty of Philosophy’s proxy for the teaching of PhD students. His main area of expertise is the history of cosmology. He is the author of two books on this subject matter published by the JU Press: Natura i struktura wszechświata w kosmologii św. Tomasza z Akwinu [Nature and structure of the Universe in the cosmology of St. Thomas Aquinas] (2007) and Nowy obraz świata. Poglądy filozoficzne Mikołaja Kopernika [A new image of the world. The philosophical view of Nicolaus Copernicus] (2018).

16 alma mater No. 243

Professor Marcin Karas during the debate Big Questions in Kraków, organised at the Jagiellonian University on November 28, 2022

Anna Wojnar

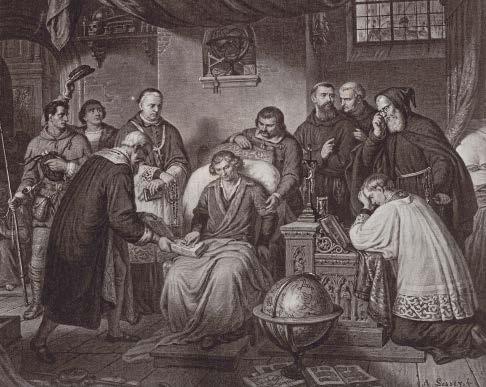

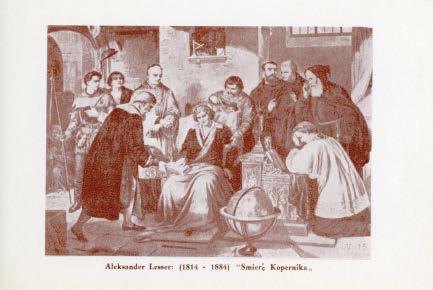

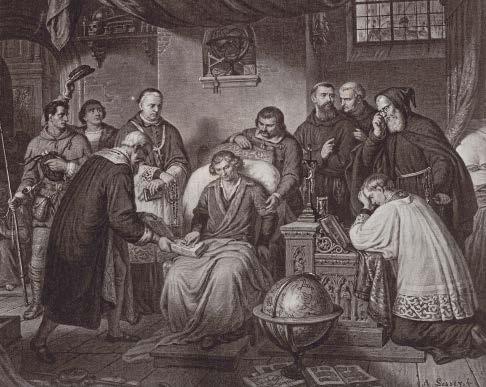

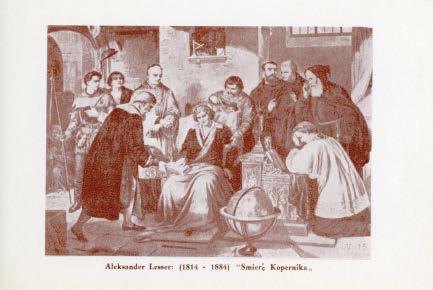

Aleksander Lesser, Ostatnie chwile Kopernika [Copernicus’ last moments], 1884

From the collection of the Jagiellonian Library

Ages. But they hadn’t – and Copernicus had. They helped him immensely, but the achievement is his. But we need to remember that Copernicus’ work has its roots in Kraków, in our University and in Scholasticism. This, I think, is something we should defend with particular care, so that there are no oversimplified narratives about how a Polish student travelled to Italy and there he achieved enlightenment, discovering that the Sun is in the centre of the Universe. As if he hadn’t learned anything in Kraków, but received all his knowledge from Domenico Maria Novara da Ferrara with whom he collaborated. We need to avoid such oversimplifications.

□ But why are studies on Copernicus so full of them?

■ The main problem in Copernican literature is that some authors derive their knowledge from old books instead of looking into sources. They take what was already written and don’t question how someone arrived at their conclusions, thoughtlessly repeating certain opinions. If they looked into sources, they’d see that it’s different: some interpret the work and history of Copernicus for themselves and others just repeat them. There’s a new book about Copernicus in which the author states that if he was a historian or researcher, he would’ve had to make all sorts of footnotes and disclaimers, but since he’s a journalist, he can just write whatever he thinks is right. We need to avoid this kind of thinking, or there’ll be no progress in the studies on Copernicus. There will be expressive and colourful stories, but they’ll be untrue. It’s necessary to scrutinise the source material, preferably in the original, and then look for studies done on the subject; check studies with sources, not sources with studies. From time to time, some famous astronomer specialising in, let’s say, extragalactic astronomy, is asked to write something about Copernicus. But if that person was never involved in researching the history of science, there’s a major risk that they’ll look at certain things through the modern lens, which simply doesn’t fit. Only a historian of science is competent here, someone who can read Latin and knows about certain contexts, about Aristotelianism.

The most common mistake people make when thinking about Copernicus is that he somehow degraded Earth, removed it from the centre of the Universe and put it aside with other planets. But someone who knows the philosophy of Aristotle will realise that in the eyes of Aristotelians Copernicus did exactly the opposite. He took Earth – the worst part of the Universe, where everything lives and dies and there’s nothing constant, nothing immutable – and turned it into a star! This is a promotion, a great honour, contrary to what’s often being written.

And the most basic issue: one can’t read Copernicus from the perspective of Newton, Einstein and Galileo, but instead start from the past: from the perspective of Thomas Aquinas, John Buridan, Albert of Saxony and Wojciech of Brudzewo. Copernicus knew about his predecessors, whereas he can’t have known about those who came after him. Presentism, introducing modern ideas into the past, is the greatest mistake. This is akin to asking what type of car Copernicus had owned. The question is preposterous in and of itself.

□ What can we learn from Copernicus today?

■ Humility. That we need to wait until the very end to present our conclusions. Copernicus must’ve been tempted many times to announce his discovery. The fact that he waited shows his maturi-

ty, that he understood the need to rethink and recheck, to discuss and then to publish something only after making absolutely sure it’s correct. Those who study Copernicus should do the same.

□ Your book Nowy obraz świata. Poglądy filozoficzne Mikołaja Kopernika [A new image of the world. The philosophical views of Nicolaus Copernicus] was published five years ago. Are you planning on writing anything else about Copernicus?

■ I don’t have any such plans, but I think it’d be worth to carefully study manuscripts related to Copernicus stored at the Jagiellonian Library. However, this would be quite a daunting task, as there are over a thousand of them. Not all of them are related to cosmology, but analysing just ten or fifteen of them could take years.

I myself would like to discuss the issue of Earth’s movement in post-Copernican cosmology, in its Aristotelian strain. Learn how scholars dealing with this branch of knowledge argued that the Earth stands still after Copernicus’ discovery. Was their approach to the subject narrow-minded or respectful but flawed? Because these are two completely different things. The standard explanation is that they weren’t mature enough to understand Copernicus. But I’d like to know why they weren’t convinced. Was it because they couldn’t have seen the movement of Earth? Or because Copernicus’ arguments were too refined? Or maybe they had their own arguments to the contrary? I already have some names of authors I’d like to research.

□ Then I wish you many more intriguing discoveries involving Copernicus. Thank you very much for the interview.

Interview by Rita Pagacz-Moczarska

17 alma mater No. 243

Unique woodcut with the transcript of Copernicus’ epitaph in Frombork, Kraków, about 1618

From the collection of the Jagiellonian Library

Images of Nicolaus Copernicus from the collection of the Jagiellonian Library

18 alma mater No. 243

Image of Nicolaus Copernicus, author unknown

19 alma mater No. 243

Portrait of Nicolaus Copernicus by Esme de Boulonois, 1682

Image of Nicolaus Copernicus by Leon Wyczółkowski, 1924

Copper-plate engraving of Nicolaus Copernicus made by Johann Theodor de Bry based on a woodcut by Tobias Stimmer. Jean-Jacques Boissard, Icones virorum illustrium…, 1598

Illustration from the Album of Nicolaus Copernicus by Ignacy Polkowski, 1873

20 alma mater No. 243

Series of likenesses of Nicolaus Copernicus from the Album of Nicolaus Copernicus authored by Ignacy Polkowski, 1873

21 alma mater No. 243

Copernican plaque in St. John’s Church in Toruń.

Photo print by Melecjusz Dutkiewicz, Warsaw, 1873

Image of Nicolaus Copernicus, author unknown

The Portrait of Copernicus by Jan Feliks Piwarski, 1852

Drawing by Władysław Łuszczkiewicz showing Nicolaus Copernicus

Portrait of Nicolaus Copernicus by L. Horwart, 1829

A. Comerio, Copernico Mery Litauer, Nicolaus Copernicus

Illustration from the Album of Nicolaus Copernicus authored by Ignacy Polkowski, 1873

Key dates in Nicolaus Copernicus’ life

February 19, 1473 – born in Toruń in a merchant family

1491 – completed education at St. John’s Church school in Toruń and arrived in Kraków with his brother Andrzej

1491 – 1495 – studied quadrivium (liberal arts) at the University of Kraków

1496 – received minor orders, probably subdeaconate

1496–1501 – studied canon law at the University of Bologna

1497 – became member of the Warmian cathedral chapter and took the office of Canon of Frombork

1500 – completed legal apprenticeship at the Papal Chancery in Rome

1501–1503 – studied medicine at the University of Padua

May 31, 1503 – received his doctorate in canon law from the University of Ferrara

1504–1510 (or 1512) – served as a secretary and physician to his uncle Łukasz Watzenrode, Bishop of Warmia (based in Lidzbark Warmiński)

1507–1510 – developed and disseminated in manuscript copies the first outline of the heliocentric model, known by the title Commentariolus

1509 – Theophylact Simocatta’s Letters translated by Copernicus from Greek into Latin are published in print in Kraków

1512 – together with the Frombork chapter swore an oath of loyalty to King Sigismund I; took the office of the Frombork Chapter Chancellor and Visitor of the chapter’s estate

1513–1516 – took part in the work on the Julian calendar reform

1514 – purchased a tower in Frombork (part of the city’s defensive walls) and established an astronomical observatory in it

1516 – started to perform economic and administrative duties on the estates of the Warmian cathedral chapter

1520 – organised the defence of Olsztyn during the last war against the Teutonic Order

1523 – became the general administrator of the Diocese of Warmia

1526 – drew up a map of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in collaboration with Bernard Wapowski

1528 – presented a monetary reform programme in the treatise Monetae cudendae ratio

1539 – was visited by Georg Joachim von Lauchen, known as Rheticus, a professor of mathematics from Wittenberg who wanted to learn about Copernicus’ astronomical theory

1542 – the book De lateribus et angulis traingulorum [On the sides and angles of triangles] was published in print in Wittenberg; it would later become part of the first book of De revolutionibus

1543 – the work De revolutionibus orbium coelestium was published in Nuremberg

May 24, 1543 – passed away in Frombork

22 alma mater No. 243

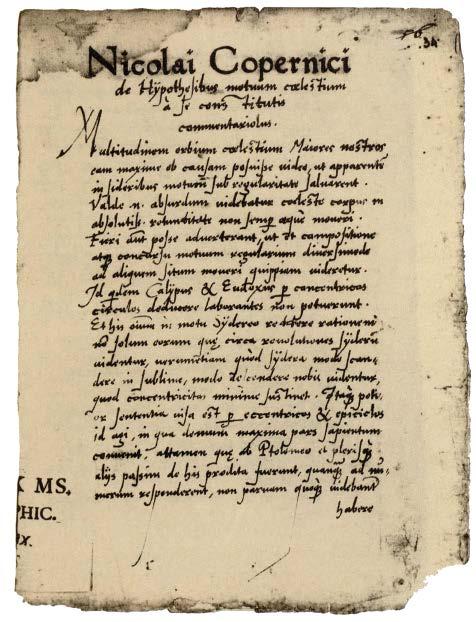

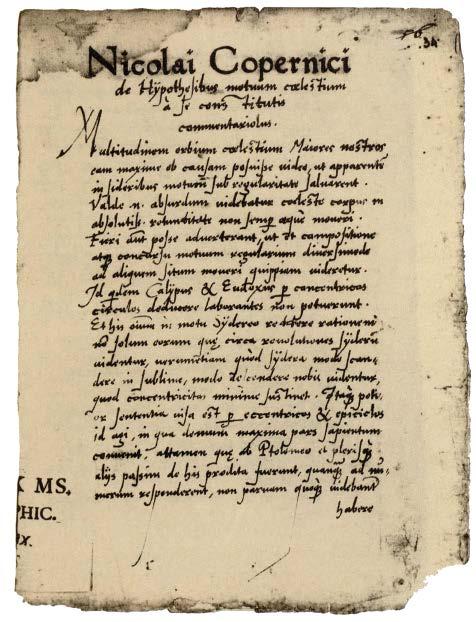

Nicolai Copernici de hypothesibus motuum coelestium a se constitutis commentariolus – first version of Copernicus’ theory, ca 1507

From the collection of Osterreichische Nationalbibliothek

Jan Matejko, The Influence of the University on the Country in the 15th Century, 1889, currently displayed in Collegium Novum assembly hall

the

the

Władysław Łuszczkiewicz, Nicolaus Copernicus in Collegium Maius Courtyard, middle 19th century The painting is currently displayed in Collegium Novum, near the Rector’s office

From

collection of

Jagiellonian University Museum

From

the collection of the Jagiellonian University Museum

Kraków, its university, Copernicus and his fame

CraCovia totius Poloniae urbs Celeberrima1

In the 1490s Kraków, together with neighbouring towns of Kazimierz and Kleparz, had about 20 thousand inhabitants. It was the capital of the Kingdom of Poland, the seat of the ruler of a vast country and of a wealthy bishopric. At that time the Kraków patriciate was ethnically German. The city was governed by the German Town Law, also known as Magdeburg Law. The patriciate of Kraków took great pride in St. Mary’s Church located next to the Main Market Square. In 1489, the woodcarver from Nuremberg Veit Stoss made an altar for the church’s chancel with the Assumption of Mary depicted in the centre. On Sundays and other occasions sermons in German were given there. Conversely, members of the higher clergy – prelates and cathedral or collegiate canons – were Polish and usually came from noble houses. Royal officials, wealthy nobles and chivalry, who were mostly Polish, also had residences in

the city. There was also a certain number of Poles among the common burghers and plebs. Besides the Wawel Cathedral and other urban parishes, Polish sermons were delivered in St. Barbara’s Church, located next to St. Mary’s Church. A new trend developed from the middle 15th century: more Poles than Germans were becoming citizens of Kraków. The total number of 42 people granted this status in 1495 included 28 Poles and 11 Germans. The entire city was also inhabited by Jews, who migrated to Kraków together with the German people. They spoke the dialect of German known as Yiddish. In the second half of the 15th century their religious buildings, mostly synagogues, were located near the current Plac Szczepański (Szczepański square). Only in 1494, King John I Albert, pressured by the city council, ordered Kraków Jews to leave the city and move to the neighbouring town of Kazimierz, which led to the creation of a separate Jewish district. Besides, the migrants to Kraków included Italians from such cities as Genua, Milan, Venice or Florence.

One of them, Filippo Buonaccorsi, called Callimachus, who came from San Gimignano, was the tutor of the sons of King Casimir IV Jagiellon. Kraków was also inhabited by Ruthenians, Hungarians and Lithuanians, as well as several families of Catholic Armenians. It was the most important centre of international trade on the east-west and north-south axes and the Hanseatic city located furthest away from the Baltic Sea. It enjoyed a staple right for goods brought from ‘all parts of the world’, which foreign merchants were additionally obliged to offer for sale.

At the time of Casimir Jagiellon’s rule, the main trade partner of Kraków on the north-south axis was Toruń. After the Second Peace of Toruń (1466), part of the State of the Teutonic order, including Toruń, Gdańsk, Elbląg, and Warmia, became part of the Polish Kingdom known as Royal Prussia. At that time Silesia consisted of numerous duchies, mostly ruled by dukes from the Piast dynasty, which earlier had reigned over entire Poland. From the middle 16th century, it was one of

24 alma mater No. 243

Colour woodcut of Kraków from Hartmann Schedel’s Nuremberg Chronicle, Nuremberg 1493 Public domain

the lands of the Bohemian Crown, which from 1471 was ruled by King Vladislaus II Jagiellon (died 1516), the son of the Polish king. From 1490 Vladislaus was also the ruler of Hungary and Croatia. The uniting of Poland, Lithuania, Bohemia, Hungary and Croatia under the reign of one dynasty brought all these countries together and fostered intense trade relations between them.

As a result, merchants from Prussia, Silesia, Hungary, and even Greeks, Turks, Tatars and Armenians from the Orient, could be seen in Kraków marketplaces. Hence, in the 1490s the city was an important centre of politics, religion, trade and crafts, of regional, Central European and continental significance.2

Civitas, in qua liberalium artium

The University of Kraków was founded in 1364 by King Casimir the Great, the last ruler of Poland from the Piast dynasty. After his death the University fell into decline, but in 1400 it was re-established by King Vladislaus Jagiełło, the founder of the Jagiellonian dynasty.4 In the middle 15th century, the University of Kraków entered a period of especially rapid growth. Its renown considerably increased, while many European universities were reduced to a regional status. It became an international university, a rival of other major academic centres, especially the University of Leipzig. People from Hungary, Silesia, Prussia, Lusatia, Meissen, South German states, and Switzerland came to study in Kraków. From winter semester 1491/1492 to summer semester 1495 a total of 1,232 scholars were matriculated at the University of Kraków, 516 of whom came from the Polish-Lithuanian state (comprising lands currently belonging to Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, and Ukraine) and 716 – from abroad. Hence, foreigners made up 58.11 percent of the entire student population, even though during that short period the matriculations were hindered by crop failure and an epidemic.5

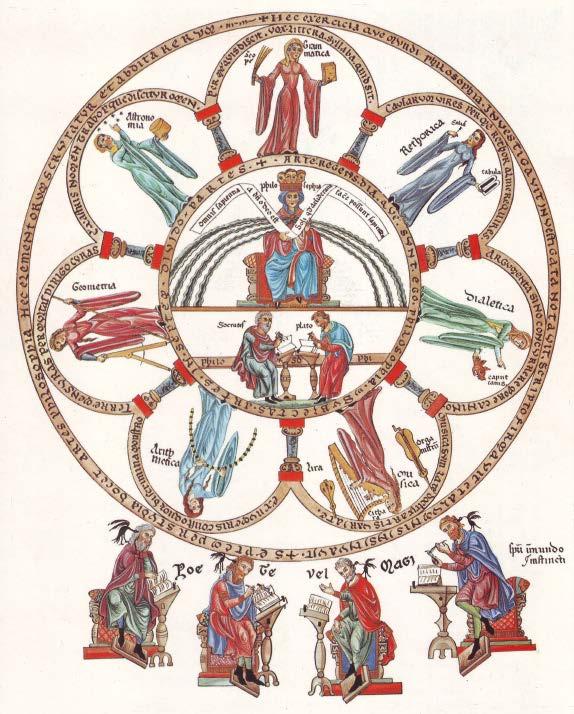

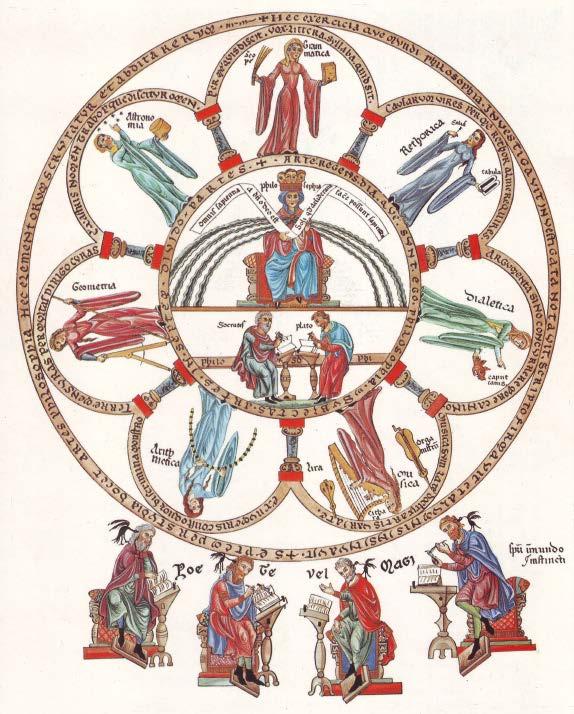

Kraków was especially famous in Europe for its high level of scholarship in the liberal arts ( artes liberales ). In his description of Europe (In Europam) written around 1458, the renowned Italian humanist Enea Silvio Piccolomini (from 1458 – Pope Pius II) stated that in Kraków ‘a school of liberal arts is thriving’.6

In a chronicle published in Nuremberg in 1493, the German humanist and historian Hartmann Schedel wrote that in Kraków ‘there is a renowned university, visited by many, famous for its outstanding learned men, which teaches the noble arts of rhetoric, poetics, philosophy and philosophy of nature. But the most thriving discipline there is astronomy, and there is no better school in this field throughout Germany’.7 In an epigram entitled Ad Gymnasium Cracoviense, dum orare vellet, the German humanist Conrad Celtes, who spent two years in Kraków (1489–1491), praised the city’s University, whose ‘academic fame reaches the heavens’, for studying liberal arts, exploring the mysteries of nature, the movement of stars, and the celestial map.8 At the same time the Italian humanist Antonio Bonfini, a court historian of Hungarian kings, wrote that ‘Kraków is full

of soothsayers and astrologists’.9 Astrology was then considered the crowning achievement of astronomy – its practical application.10

Liberal arts were traditionally divided into two ’paths’: trivium and quadrivium. The former consisted of grammar, rhetoric, and dialectic, whereas the latter comprised arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music. Grammar was taught from the language textbook Art of Grammar (Ars grammatica or Ars maior) authored by the 4th-century Latin grammarian Aelius Donatus. Another work studied during the course was the second volume of versified Latin grammar textbook Rules for Boys ( Doctrinale Puerorum ) written by the Flemish author Alexander of Villedieu (de Villa Dei, died c. 1240), discussing syntax. Then the students focused on poetics and rhetoric. The former was taught based on such works as Labyrinth (Laborintus) by Eberhard of Béthune (died after 1212) and New Poetics (Poetria Nova) by Geoffrey of Vinsauf (Ganfredus de Vino Salvo).