THE

-

2023 13

SÃO FRANCISCO RIVER BASIN COMMITTEE MAGAZINE

MAY

CREDITS

President: José Maciel Nunes de Oliveira

Vice President: Marcus Vinícius Polignano

Secretary: Almacks Luiz Silva Produced by Communications Office

CBHSF, Tanto Expresso Comunicação e Mobilização Social

General coordination: Paulo Vilela, Pedro Vilela and Rodrigo de Angelis

Communication coordinator: Mariana Martins

Editing: Karla Monteiro

Editorial assistant: Luiza Baggio

Texts: ndréia Vitório, Arthur de Viveiros, Deisy Nascimento, Hylda Cavalcante, Karla Monteiro, Luiza Baggio and Mariana Martins

Graphic design: Márcio Barbalho

Layout: Albino Papa and Rafael Bergo

Photos: Allan Rodrigo, Azael Neto, Bianca Aun, Cristiano Costa, Edgar Kanaykõ Xacriabá, Edson Oliveira, Fernando Piancastelli, Geovana Jardim, Juciana Cavalcante, Letícia Massula, Léo Boi, Léo Ramos and Pedro Vilela

Cover photo: Emerson Leite

Illustrations: Albino Papa and Bruno Lanza

Review: Isis Pinto

Printing: ARW Gráfica e Editora

Print run: 3500 copies

FREE DISTRIBUTION

Rights Reserved. Allowed to use information provided the source is cited.

Committee Secretariat:

Rua Carijós, 166, 5th floor, Downtown Belo Horizonte - MG

CEP: 30120-060 - (31) 3207-8500 secretaria@cbhsaofrancisco.org.br

Service to users of water resources in the São Francisco River Basin: 0800-031-1607

Communication Advisory: comunicacao@cbhsaofrancisco.org.br

Online english version: bit.ly/Chico-Magazine-13

www.cbhsaofrancisco.org.br

Visit

Instagram: Instagram.com/cbhsaofrancisco

Facebook: Facebook.com/cbhsaofrancisco

On-line edition : issuu.com/cbhsaofrancisco

Videos: youtube.com/cbhsaofrancisco

Photos: flickr.com/cbhriosaofrancisco

6 Green pages

Indian does not want whistle

SUMMARY 4 Editorial Protagonists Indigenous

Ibama

“Wearing the Headdress in Power means Standing forests”

18 Profile The men of

12 Indigenous issue

Podcasts: soundclound.com/cbhsaofrancisco the CBHSF website Use your cell phone and access the QR Code

Access the multimedia contents of CBH São Francisco:

50 Rehearsal 48 happened 30 Infrastructure Water to drink 34 Gastronomy A script that takes you by the stomach 38 Tourism Cerrado Seed 42 Archeology Lost City 22 Public policy The return of Ana 26 Infrastructure What are you thirsty for?

PROTA GONISTS

4

INDIGENOUS

In the first weeks of the year 2023, we were confronted with the most terrible images: emaciated Yanomami people, living dead, victims of neglect. According to the Israeli-born writer Noemi Jaffe, the images were comparable to the Holocaust. “They belong to the same order of horror, and the method used is also the same,” she wrote on Twitter. Speaking in Boa Vista, the capital of Roraima, alongside the Prime Minister of Indigenous Peoples, Sônia Guajajara, President Lula promised, above all, to ensure dignity for the indigenous peoples.

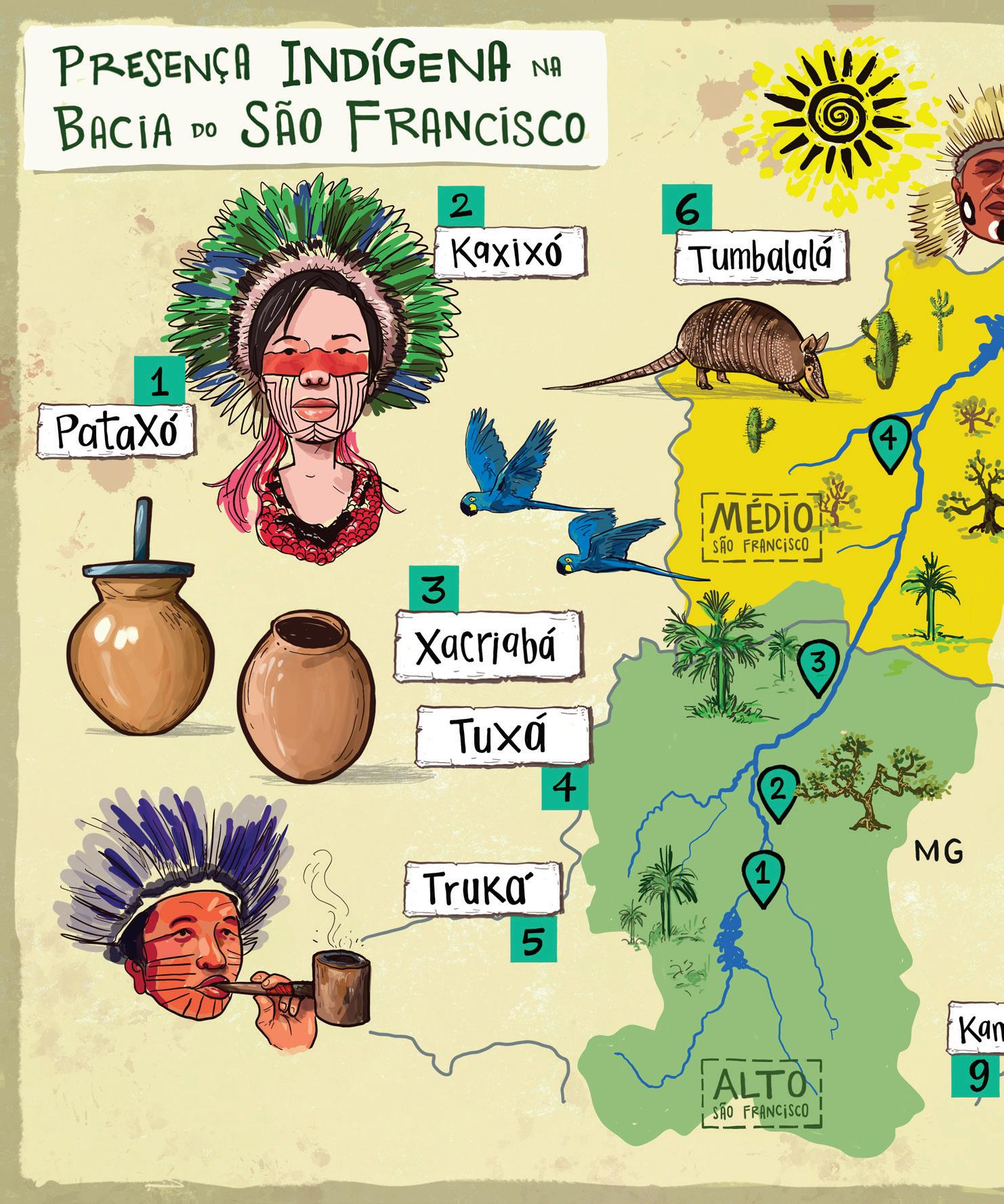

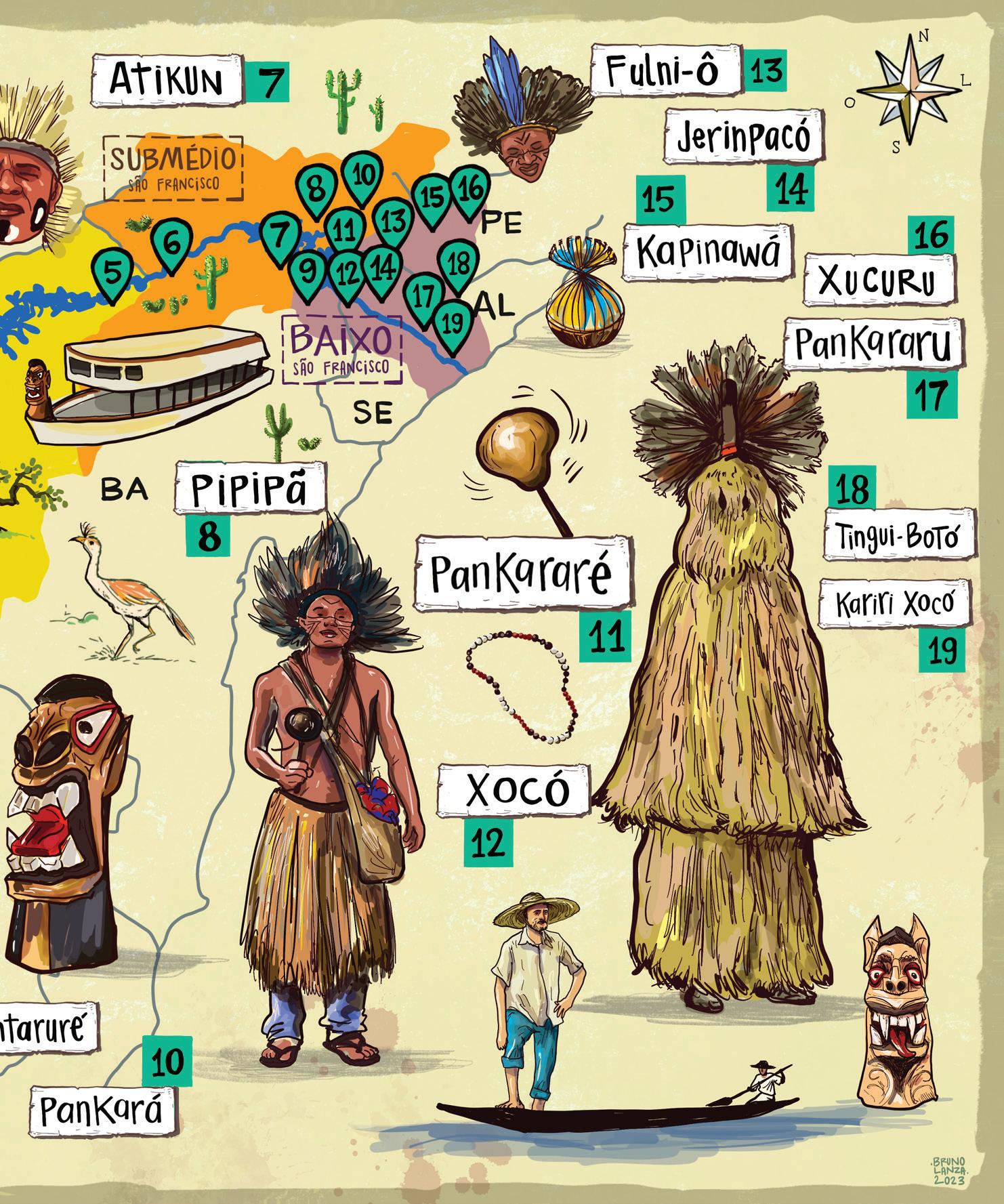

The Yanomami issue brought our ancestral debt back to the center of the debate. Over 40 ethnic groups resist on the banks of the Velho Chico River to the procession of epidemics, violence, and destruction: Fulni-ô, Kambiwá, Tumbalalá, Tingui-Botó, Kapinawá, Tuxá, Pankararu, Pankará, Truká, Xocó, Xakriabá, and other peoples. In the report “Índio não quer apito” (“Indigenous people don’t want whistles”), CHICO magazine interviewed leaders to assess the situation in the communities. The main issue continues to be land demarcation, parallel to the annihilation of the environment.

“The essence of an indigenous people is its territory,” said Chief Uilton Tuxá, coordinator of the Technical Chamber of Traditional Communities (CTCT) of the São Francisco River Basin Committee (CBHSF). With the creation of the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples, hope lies in better days.

In this edition, indigenous peoples are the protagonists. In the Green Pages, federal deputy Célia Xakriabá, the first indigenous woman elected in Minas Gerais, shows why “having a headdress in power means standing forests.” At 32 years old, she is making history in the National Congress. In another report, “What are you thirsty for?,” CHICO magazine attended the inauguration ceremony of the new water supply system in the Kariri-Xocó community. With a cost of almost nine million reais, the project, led by CBHSF, will benefit 4,200 people. According to Anivaldo Miranda, coordinator of the Regional Consultative Chamber (CCR) of the Lower São Francisco, this achievement for the Kariri-Xocó is the result of a participatory water resources policy.

There is much more in the first CHICO edition of 2023. In the report “The Ibama Man,” a profile of the new director of the vital agency for the success of environmental policy, Rodrigo Agostinho. In the gastronomy itinerary, the travel account of the Minas Gerais chef Letícia Massula. In two expeditions along the São Francisco River, she discovered sophistication and diversity. If the idea is to hit the road, get to know Vila de Santo Inácio, in the Bahian hinterland, possibly the lost city of the French explorer Apollinaire Frot. And to clear your sight: a visit to the “Ser do Cerrado” project of the Inhotim Institute, the largest open-air museum in the world, located in Brumadinho, Minas Gerais.

Enjoy your reading!

Editorial

5

illustration: Albino Papa

Green pages

By: Hylda Cavalcanti

Edgar kanaykõ Xacriabá

By: Hylda Cavalcanti

Edgar kanaykõ Xacriabá

“WEARING THE HEADDRESS IN POWER MEANS STANDING FORESTS”

At 32 years old, Célia Xakriabá has already made history as the first indigenous federal deputy elected in Minas Gerais. Running for the PSOL party, she obtained more than 100 thousand votes. In Congress for just over four months, she continues to write new chapters. First, she assumed leadership of the socalled “Headdress Caucus.” Next, she was chosen to coordinate a mixed parliamentary front for the “Defense of Indigenous Peoples” and, more recently, to preside over the “Commission for the Amazon and Indigenous Peoples of the Chamber.”

The Xakriabá people are native to the banks of the São Francisco River, specifically around São João das Missões in northern Minas Gerais. Battles with the white man began early, back in the 18th century during the gold cycle. Carrying this heritage, Célia earned her PhD in Anthropology from the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG) and, immersed in her people’s struggle, became an activist, participating in the founding of the National Articulation of Indigenous Women Warriors of Ancestry. As she often says, “With me, 900 thousand headdresses enter the Federal Chamber.” “In over 500 years, indigenous peoples have been excluded from institutional politics, and our arrival in Congress represents a victory. Wearing the headdress in power means standing forests.”

6

Art: Albino Papa

Photo:

7

You were elected as a federal deputy with a significant number of votes. What does this mean?

We may have less time in the National Congress, but we have more time in Brazil. In the Legislature, we have much to do to defend indigenous peoples, in terms of land demarcation, environmental protection, women’s rights, and human rights.

In November of last year, even before taking office, you participated in the 27th United Nations Climate Conference (COP27). What are your impressions? Can we expect changes in the face of climate change?

As COP is a space closed to civil society, we did not have access to the official activities. However, President Lula’s participation was very important. Since the previous event in Glasgow, we have been saying that there is no solution to halt climate change without recognizing the power of the social technologies of indigenous territories and traditional communities. Now, we reiterate that. This COP also marked the end of a cycle in which Brazil faced four years of profound setbacks, with an Ecocide in power. Internationally, we had lost prestige and prominence.

Is it possible to dissociate environmental issues from the indigenous cause, as many attempted to do in the previous government?

You cannot talk about combating climate change without talking about the demarcation of indigenous territories. If the issue is funding, it is essential that it reaches the true guardians of the forests and biomes. At COP, for example, we made an important appeal to the European Parliament to carefully consider the anti-deforestation law. The law considers the Amazon, but not parts of the Atlantic Forest, Cerrado, Pantanal, Caatinga, and Pampa as forests. By not recognizing these biomes, it ends up legitimizing deforestation. We also advocate for the creation of a traceability law. Many commodities come from traditional communities and end up fueling violence in these territories. We also highlight mining, which is currently responsible for serious environmental crimes in Brazil, such as the one committed by Vale in the state of Minas Gerais, in the Doce River. Mining represents no more than 4% of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). If people are genuinely concerned about money, it would be important to promote conscious and intelligent consumption.

After four years of setbacks in the environmental area, Brazil now has a new government, including an unprecedented Ministry of Indigenous Peoples led by a woman indigenous leader. How do you see this change?

We have a unique opportunity to make progress, even though we understand that land demarcation is very costly due to the processes and rituals, just like the titling of quilombola territories. We are experiencing a moment of great hope to move forward because we cannot advance on indigenous education and health, for example, when the main issue is the territory. Without territory, our identity and way of life are threatened. So, we want and can occupy various ministries, such as Culture and Education. The Indigenous Ministry is extremely important, but it cannot be a place that restricts our presence. Our place is everywhere. We need to think about this transversal policy, thinking in an identity-centered way but also understanding that identity needs to be present in all spaces.

And what are the main prospects regarding this government?

Today, in Brazil, we have the opportunity to reverse ecocide and genocide. We are much more than activists because when they kill an indigenous leader due to territorial conflicts, such as Bruno Pereira and Dom Philips, it affects us, as we are part of the environment with our way of life. Recognizing ourselves and our ancestors also involves recognizing that the solution to climate change must reflect a conscious humanity. We understand the importance that when they attack the land and the environment, they are attacking us as well.

How does Minas Gerais fit into this context?

Minas Gerais is the state that deforested the most Atlantic Forest last year, and this obviously has a direct impact on the territories, in addition to the significant impact of mining. So, internationally, we emphasize the importance of decolonizing biomes. To understand what exactly the diversity of ecosystems that makes Brazil a country with such rich and powerful socio-biodiversity is, we need to protect the forests, waters, and ourselves because we are the defenders of these places. If they reach our territories and bodies, humanity will feel its implications. We cannot discuss this without listening to those who are most affected and most involved in this protection.

8

How was your performance, as militants of indigenous peoples, in the last four years?

I said that to President Lula. Since January 1, 2019 (the date of inauguration of former President Jair Bolsonaro), we have always been on the streets. Even with a reactionary and fascist government, in a pandemic context, we were camped for more than 30 days in Brasilia, because we understand that, if we didn’t die from the virus, it would be because of the passing of the herd and territorial conflicts. We now have huge expectations and challenges, we know it won’t be easy, but we are experiencing a moment of opportunity. Lula’s campaign was based on an environmental commitment, to break with illegal mining and carry out the demarcation of our territories.

You are composing Congress in a legislature in which several exponents of agribusiness and conservatism were elected with great representation. What is your understanding of this fight?

People said that if it wasn’t now it would be later my election, and I said: it’s a context fight, we’re not going to have it again so soon. If we look at the history of Brazil, the leftist government never elected indigenous people. Mário Juruna was elected in 1982, in another context, and Joenia Wapichana won in the Bolsonaro government. So, it is an opportunity, mainly because we experience a scenario of profound violence against indigenous rights and the environmental issue. It is a response not only ours, but also of humanity, because at that moment it meant much more than the result on the ballot box.

Minas Gerais, which had 53 deputies, had never elected an indigenous woman to Congress. We managed to overcome racism, just like Sônia Guajajara in São Paulo. It is the first time that we are going to arrive with the “cocar bench”. Of the 853 municipalities in the state, we are allocated in 804 and I am the only female federal deputy from the north of Minas, in addition to being the third most voted in Belo Horizonte. They are different answers, it was not just arriving, but the process of breaking with the old logic of the way to arrive. We were not supported by the old traditional policy of supporting city halls. We knew it was the right time to provoke this moment and I understand, with great pride, that our election went through a polarization vote. It wasn’t just a progressive vote that elected us, they voted for Tebet, Lula, Ciro and us. Even Bolsonaro. This is interesting to observe what converges.

But practically speaking, what do you, of the so-called headdress bench, can they do it in Congress being a minority?

We, indigenous peoples, are not even 1% of the Brazilian population, we are 5% of the world’s population and we protect more than 30% of biodiversity. Not always who is in the majority is making improvements, and if our voice is not enough from the inside, we will continue to call for movement from the outside. Power is not just Executive, Legislative and Judiciary. Struggle is the fourth power. We may have less time for the National Congress, but we have more time for Brazil. It will be challenging, but we are prepared to face Ricardo Sales (Bolsonaro’s former Environment Minister and current federal deputy). Who is better prepared than us to face the ruralist group?

Coming out of Congress, we have had many indigenous people elected to various positions in recent years. How do you see the current indigenous moment and its evolution from the point of view of the political and institutional struggle?

Indigenous candidacies have grown considerably. In the 2020 elections we had one of the greatest results for city halls and councils and, now, we have grown compared to those of 2018. We are not going to stop here, we will continue to strengthen the presence of indigenous peoples within city halls and municipal and state structures for the coming years. We understand that this was a historic moment, but they will not be the last or only candidates elected, the idea is always to bring more people. Along with us come thousands of ancestral forces and that’s how we’re going to extend this summons to the headdress bench.

You have a good academic background, which you have always aligned with your roots. Can you talk a little bit about that?

I studied in indigenous schools and I always had a strong relationship with the territory and with the cultural roots of my people. The experience with education was what motivated me to become an educator and return to my territory. It is important to think about a territorialized education, where our body moves to places other than the classroom. And that’s how politics is for me: parliament moving to where the fight is. And I intend to do just that. Pioneering spirit is a motivation to keep fighting. We are no longer happy to be the only ones. We have a redoubled responsibility.

9

“Why have you declared that your mandate will be one of resistance when you were so well received in the elections?”

I understand that Minas Gerais has overcome the racism of absence by electing, for the first time in history, an indigenous woman as a federal deputy. And I have committed to legislate with the land, with the call of the earth, which brought me here. Minas will take pride in ‘feminizing,’ ‘reforesting,’ and ‘indigenizing’ politics. In 2020, 85 indigenous leaders were assassinated, which is why I affirm that this will be a mandate of resistance. It will be a mandate of struggle. In fact, the decision for my candidacy was due to the constant attacks on indigenous territories. We decided to confront them from within, against the ruralist caucus, against agribusiness, for the demarcation of indigenous territories and traditional communities, and for the environment. For over 500 years, indigenous peoples have been excluded from institutional politics, and our arrival in Congress represents a victory. Having a headdress in power means a standing forest. It represents ancestry and a different way of thinking and doing politics. That is our commitment.

Regarding your educational background, how do you view the importance of indigenous participation in academia?

The university, like other institutions, needs to break free from the racism of absence. I was the first indigenous person to earn a Ph.D. at UFMG, and I felt very isolated. We possess wisdom, and our presence is essential to “Aquilombate” (uniting as in a quilombo) and “indigenize” academia. The whole world witnessed the neglect of the previous government towards the Yanomami people, and their current situation, which calls for urgent action. You were one of the first to participate in actions and denunciations. Can you give a specific example of the situation?

The situation of the Yanomami people must be one of our priorities in our work. When we talk about them, we talk about the consequences of illegal gold mining and about lives that, for the past 523 years, have never been a priority in Brazilian politics. Do you know what it’s like to hear a father say that his child died of hunger? We need to think about life projects within the Chamber and the Senate. We need to investigate and halt other processes of violence. For example, over 70% of Yanomami children are contaminated with mercury.

You’ve achieved two recent victories since taking office: first, the presidency of the Mixed Parliamentary Front in Defense of Indigenous Peoples. What does this represent for your journey that is just beginning?

We managed to prevent our indigenous front from being undermined. Our ‘cocar’ caucus (indigenous representatives) simply prevented deputies directly involved in illegal gold mining from participating in the front and defining policies for this population. We want to make the Yanomami territory one of the main focuses now. We have been working on raising awareness. The parliamentary front was an important achievement. We got 203 signatures in the Chamber and the Senate. When we look at who signed, we see that it is a commitment that goes beyond progressive parties. We want to open a dialogue on environmental and territorial issues. We believe that there will be a lot of struggle, especially in a Congress with different economic and political interests, but popular pressure can change the decision-making process. We believe in our power, our voice of raising awareness inside and outside.

And about your second victory, the presidency of the Commission for the Amazon and Indigenous Peoples, what do you have to say?

Who else is capable of facing the ruralist caucus if not the ‘cocar’ caucus? I assume the presidency of this commission, reaffirming the need for broader protection, with policies that enhance the knowledge of indigenous peoples and conservation in all biomes, not just the Amazon. Assuming the role of leading this struggle is not just assuming the voice of an indigenous parliamentarian, but it is assuming the voices of the territory. The UN points to the demarcation of indigenous lands as one of the main instruments for tackling climate change. And support for indigenous agriculture is one of several ancestral social technologies that can be used as a territorial protection mechanism. I won’t be the only indigenous person leading the commission; there will be 900,000 headdresses leading it with me.

By: Andréia Vitório

INDIAN DOES NOT WANT WHISTLE

After the terrifying images of emaciated and half-dead Yanomamis were revealed, the indigenous issue was brought into the spotlight. CHICO magazine traveled along the winding course of the Velho Chico river to learn about the reality of the more than 40 ethnic groups that inhabit the basin. With the first indigenous minister in Brazilian history, Sônia Guajajara, there is hope that better days will come.

The new government was still settling in when President Lula arrived in Boa Vista, the capital of Roraima. In the entourage, composed of eight ministers of state, was Sônia Guajajara, the first indigenous person to hold a ministry. While the presidential caravan was there, images of emaciated and halfdead Yanomamis were spreading worldwide. Originating from the Brazilian Amazon, those photographs evoked the end of the Second World War when Russian soldiers opened the gates of Auschwitz, revealing the immense barbarity of the Nazis against the Jews. “I know that the Shoah seems beyond comparison, but it is not. The images of the Yanomamis are of the same order of horror, and the method used is also the same,” tweeted the Israeli-born writer Noemi Jaffe. Faced with the holocaust repeatedly denounced during the Bolsonaro government, Lula promised dignity for indigenous peoples.

“I came here to commit to the chiefs that we will give them the dignity they deserve in health, education, food, and the right to come and go,” the president declared. “We will take very seriously the matter of ending any illegal gold mining.”

Certainly, the task of the new government does not end in the Yanomami territory. This procession of epidemics, violence, and destruction has been running through the history of all ethnic groups. Along the winding course of the Velho Chico river, about 40 ethnic groups resist: Fulni-ô, Kambiwá, Tumbalalá, Tingui-Botó, Kapinawá, Tuxá, Pankararu, Pankará, Truká, Xocó, Xakriabá, among others. According to Chief Uilton Tuxá, coordinator of the Technical Chamber of Traditional Communities (CTCT) of the São Francisco River Basin Committee (CBHSF), the Velho Chico basin is mainly composed of indigenous lands. However, a significant portion of this territory remains undemarcated. In his opinion, the first issue to address would be resolving land ownership. “The essence of an indigenous people is its territory, the land to cultivate, practice their ancestral customs and traditions, and practice traditional medicine with medicinal plants,” he said.

Indigenous issue

Illustration: Bruno Lanza

12

Along the banks of the Velho Chico river, approximately 100,000 indigenous people currently reside, representing 9% of the total indigenous population in the country. The Submédio São Francisco region, comprising Bahia and Pernambuco, gathers the largest number of individuals and ethnicities. The most populous ethnic group is the Xakriabá, with 13,000 souls, most of whom live in the municipality of São João das Missões, in Minas Gerais, in the Alto São Francisco region. According to anthropologist José Augusto Sampaio, a professor at the State University of Bahia (Uneb) and one of the founders of the National Indigenous Action Association (Anaí), the new census by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) is expected to bring surprises, with an increase in this population. The last count was done in 2010, indicating 900,000 indigenous people in Brazil, with the majority (37.4%) in the Northern region.

“There is a significant number of indigenous people from this region in universities, or who have attended universities, unlike previous generations of leaders,” Sampaio commented. “These leaders are highly qualified and are driving the indigenous movement to reclaim territories and access public policies.”

Spiritual sustainability

“The physical and spiritual sustenance of these indigenous people depends mainly on the Velho Chico river,” affirmed indigenous expert Ivo Augusto Oliveira Ferreira, who has been serving the National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples (FUNAI) since 2010. According to him, the scenario is one of resistance and, at the same time, resignation. While on one hand, efforts are made to rescue an ancestral language, such as “Dzubukuá,” on the other hand, there is the arrival of evangelical religions, with pastors becoming the new Jesuits. By the way, throughout the Brazilian Northeast, except in Maranhão, only the Fulni-ô maintain their own active language: Iatê. “We are very close to the Pankarás, for example, and we hear a lot about how they lost the cultural, spiritual, and metaphysical connection they had with the São Francisco River after the construction of the Paulo Afonso and Itaparica Hydroelectric Complex,” Ferreira exemplified.

The issue of territory permeates the entire indigenous life, from spiritual connection to physical health. According to Marcelino Mendonça de Aquino, head of the technical coordination at FUNAI in São João das Missões, the Xakriabá people, for instance, face various problems that have led to migration: drying springs, intermittent streams with water only during the rainy season, contamination from pesticides, urban sewage, siltation, loss of riparian forests, irregular occupation, and illegal logging. “During the dry season or harvest period in other regions, many leave to seek other financial resources,” Aquino emphasized. On the other hand, there are also young people leaving their communities to study at federal institutes and universities, aiming to return with knowledge in education, health, production, and commerce to change their reality.

San Francisco River Basin

Indigenous land Ethnicity City/State

State of Sergipe

Caiçara/Ilha de São Pedro Xocó Porto da Foha - SE

State of Alagoas

Aconã Tingui Botó Traipu - AL Fazendo Canto Xucuru - Kariri Palmeira dos Índios - AL Gerinpancó Jeripancó Água Branca - AL Kalanko Kalanko Água Branca - AL Jeripancó Jeripancó Pariconha - AL Karapotó Karapotó São Sebastião - AL Kariri-Xocó Kariri-Xocó S. Brás / P.R. Colégiado - AL Mata da Cafuma Xucuru - Kariri Palmeira dos Índios - AL Tingui Botó Tingui Botó C. Grande / F. Grande - AL Xucuru - Kariri Xucuru - Kariri Palmeira dos Índios - AL

State of Pernambuco

Atikun Atikun Salgueiro / Belém - PE

Entre Serras Pankararu Tacaratu / Petrolândia - PE

Fazenda Cristo Rei Pankararu Jatobá - PE

Fuini-ô Fuini-ô Águas Belas / Itaiba - PE

Ilhas da Tapera Truká Orocó - PE

Kambiwá Kambiwá Ibimirim / Inajá - PE

Kapinawá Kapinawá Brique - PE

Pankará da Serra do Arapuá Pankará Carnaubeira da Penha - PE Pankararu Pankararu Jabora / Tacarau - PE

Pipipã Pipipã Floresta - PE

Truká Truká Cabrobó - PE

Tuxá de Inajá Tuxá Inajá - PE

Xucuru Xucuru Poção / Pesqueira - PE

Xucuru de Cimbres Xucuru Poção / Pesqueira - PE

State of Bahia

Barra Atikum / Kiriri Margem S. Francisco - BA

Brejo do Burgo Pankararé Rodelas / Glória - BA

Fazenda Remanso Tuxá Margem S. Francisco - BA

Ibotirama Tuxá Ibotirama - BA

Kantaruré Kantaruré Glória - BA

Pankararé Pankararé P. Afonso / Rodelas - BA

Quixaba Xucuru-Cariri Glória - BA

Tumbalalá Tumbalalá Abaré / Curaça - BA

Tuxá Tuxá Serra do Ramalho - BA

Vargem do Alegre Pankararu Serra do Ramalho - BA

State of Minas Gerais

Caxixó Kaxixó Pompeu - M. Campos - MG

Cinta Vermelha / Jundiba Pataxó / Pankararu Araçuaí - MG

Iruã Mimatxi Pataxó Itapecerica - MG

Xakriabá Xakriabá Itacarambi - MG

Rancharia Xakriabá S.J. das Missões - MG

Source: FUNAI Identification in the Basin: Environmental Museum “Casa do Velho Chico” São Francisco River Basin

13

PEOPLE SPEAK

Threats and Ancestral Protection

At 23 years old, Caroline Silva Lima was born on Assunção Island, an ancestral territory of the Truká people located in Cabrobó, Pernambuco. Despite her young age, she is already at the forefront of battles, being part of the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples and Organizations of the Northeast, Minas Gerais, and Espírito Santo (Apoinme). According to her, the current threats come from large-scale projects, such as a nuclear power plant that has already established a test point in the region. “We are aware that in a few years or even months, we will have to deal with the consequences,” she said. “We know that the majority of compounds used are bioaccumulative, meaning they do not affect us immediately, but accumulate in our bodies and can cause irreparable diseases in the future.”

Caroline mentions that the Truká people primarily rely on family farming and fishing. However, due to environmental imbalances, fish are becoming scarce. Nevertheless, they are resilient and continue to fight for the security of their sacred territory, defending the rights of those who came before and those who will come after. They remain steadfast in preserving their culture through their songs and the traditional dance “Toré,” seeking protection and strength from their ancestors on this journey.

Truká

Location in the basin: Assunção Island, in the Middle São Francisco, municipality of Cabrobó, Pernambuco. Estimated population: approximately 5,000 indigenous people.

Territory: about 6,000 hectares. Demarcation: yes.

The Umbu Festival

“We are from the surroundings of the São Francisco river. Before the construction of dams and hydroelectric plants, we used to live here, fishing and maintaining our traditions, which took place by the river’s edge. After the construction of the Itaparica and Paulo Afonso plants, we were prevented from continuing our traditions. Now, we need to ask for permission to fish,” said Sarapó Pankararu. He mentioned that his people no longer rely on hunting and fishing, and even agriculture has become scarce, leading to migration. There is a community of over two thousand Pankararus in São Paulo.

A very common tradition among the Pankararu people is the Umbu Festival, celebrated between February and March to honor the umbu tree’s harvest. This ritual represents renewal and purification and holds significant importance for the wise Pankararu people, as their ancient culture has been passed down from generation to generation. Alongside their traditional practices, they also deeply adhere to Catholicism.

Pankararu

Location in the basin: Between Petrolândia and Tacaratu, in the Pernambuco backlands, Glória, Bahia, bordering Pernambuco and Alagoas, in the Lower São Francisco. Also present in Pariconha, Água Branca, Porto Real do Colégio, and Palmeira dos Índios, municipalities in the Submédio and Lower São Francisco, respectively.

Estimated population in the basin: over 7,500 indigenous people.

Territory in the basin: approximately 8,377 hectares. Demarcation: yes.

The Ouricuri Ritual

“Our connection with the São Francisco River is strong; it sustains us. It irrigates our beans, corn, and quenches the thirst of our cattle, besides being our main source of income from fishing,” said Karine Santos, 32 years old, from the Xocó tribe. She mentioned that the Velho Chico has risen again, leaving the community stranded. “It filled up as it hadn’t done in a long time.” In the ebb and flow of the waters, one tradition remains: the Ouricuri, a sacred ritual involving the consumption of the Jurema plant, which, according to the Xocó people, transcends their ancestral lineage.

Karine also mentioned that ceramics used to be the main source of income for her people in the 70s, 80s, and 90s, but now it is passed on through workshops and schools to children. Looking to the future, she emphasizes the importance of indigenous people occupying various spaces, including politics, as there are several bills in Congress that threaten indigenous rights and seek to roll back the progress achieved by their ancestors in securing these rights.

Xocó

Location in the basin: Aldeias Ilha de São Pedro and Caiçara, in the municipality of Porto da Folha, Sergipe, in the Lower São Francisco.

Estimated population: over 600 indigenous people. Territory: about 3,600 hectares.

Demarcation: yes.

Ancestry and the Caatinga

“The relationship of our people with the São Francisco River is cultural, traditional, and spiritual. It is sacred because our ancestors reside at the bottom of this river,” said Cícera Leal Cabral, 41 years old, Pankará chief. She mentioned that rituals are always performed with the water of the Velho Chico, on its banks. At the river’s depths, there is the Nego D’água, who overturns the canoe of those who engage in irregular fishing. In the community, some people make a living from growing beans and corn, others from handicrafts, and some are teachers. After much struggle, they have access to healthcare and a school that teaches their specific knowledge

14

For her, it is crucial to continue fighting for the right to preserve the São Francisco River and the Caatinga. Currently, the mobilization is against the construction of a nuclear power plant in the region. “We have made significant progress with the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples, a space where we can bring our demands with greater expectations of being heard and attended to,” she concluded.

Pankará

Location in the basin: Mainly in the Serra do Arapuá, municipalities of Carnaubeira da Penha and Itacuruba, in Pernambuco, Submédio São Francisco.

Estimated population in the basin: Over 5,000 indigenous people.

Territory: Around 15,000 hectares. Demarcation: In the demarcation process.

The Migrants

The Tuxá people originate from Rodelas, northern Bahia. Many still live in the region, in an urban village. However, some have migrated to Minas Gerais. The construction of the Luiz Gonzaga hydroelectric plant (formerly known as Itaparica) in 1988 contributed to this migration, submerging the Viúva Island, where the community was located. “Our territory is the environment where we live, practice our human ecology, produce food, and use biodiversity sustainably,” said Chief Uilton Tuxá, coordinator of the CTCT of CBHSF.

The Tuxá people also use the sacred Jurema plant in the Toré ritual. However, it is through the force of the Velho Chico that the Tuxás connect with their ancestral spirits. Beyond the sacred practices, many of these indigenous people rely, sometimes exclusively, on fishing and commercial agriculture for their livelihoods.

Tuxá

Location in the basin: Mainly on the borders of the Bahian municipalities of Muquém do São Francisco, Ibotirama, and Rodelas, and on the right bank of the Moxotó River, in the Pernambuco municipality of Inajá, in the Submédio São Francisco. Also present in Buritizeiro, Minas Gerais, in the Alto São Francisco.

Estimated population in the basin: Around 2,500 indigenous people.

Territory in the basin: Approximately 2,150 hectares. Demarcation: 1,650 hectares already demarcated, 500 hectares under concession by the Government of Minas Gerais, and 4,300 hectares in the process of acquisition to establish an indigenous reserve.

What is the Technical Chamber of Traditional Communities?

The Technical Chamber of Traditional Communities (CTCT) of the São Francisco River Basin Committee (CBHSF) is a significant achievement. It brings together representatives of traditional and native peoples with the purpose of strengthening the interests of these groups, which often align with environmental protection and revitalization concerns. Uilton Tuxá, coordinator of the CTCT, believes that one of the main demands of the Chamber is to feel more valued within the structure of the CBHSF itself. He also points out that the population of the basin is unaware of the diversity of traditional segments in the region and their significant role in preserving ecosystems and biodiversity.

Among the significant results of this work is the implementation of water pipelines (adutoras) for some communities, such as the Pankará people in Itacuruba, Pernambuco. “We obtained a pipeline worth over 3 million reais that guarantees water supply for our community. Before, it was challenging because we relied on water trucks, and the supply was insufficient,” said Cícera Leal Cabral, Pankará representative who is also part of the CTCT and a member of the CBHSF.

15

Map for illustration purposes only. It does not represent the entirety and precise location of the indigenous groups present in the São Francisco River basin. Various sources: Interviews, Funai, Museu Ambiental Casa do Velho Chico, and Povos Indígenas no Brasil website.

16

17

By: Hylda Cavalcanti

THE MEM OF IBAMA

Profile 18

With experience in environmental activism and a passion for nature, former federal deputy Rodrigo Agostinho has taken over the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources, a vital agency for the international success of the Lula government.

19 Arquivo câmara

deputados

dos

On February 24th, a Friday, Rodrigo Agostinho, a native of São Paulo, took over as the president of Ibama, the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources. Undoubtedly, a challenging mission. During Jair Bolsonaro’s government, the agency was practically dismantled, and it currently operates with the smallest workforce since 2001. The situation is so critical that Ibama has more vacant positions than employees. However, at the inauguration ceremony, alongside Marina Silva, he seemed enthusiastic about the challenge of getting the institution back on track. Given President Lula’s commitment to zero deforestation in the Amazon and prioritizing environmental policies, time is of the essence: “We have a shortage of inspectors. Ibama used to have 2,000 field inspectors, but currently, it only has 350 agents to carry out enforcement work throughout Brazil. My dream is to try to halve forest loss this year, but I know the situation is not exactly favorable for that.”

According to Agostinho, though: “Ibama is back to work. The presidential discourse has changed. If people were expecting to continue investing in illegal logging, mining in indigenous lands because there was no longer any enforcement, they are now beginning to reconsider that.”

To tackle the challenges, he relies on his extensive experience. Born in the countryside of São Paulo, in Cafelândia, he began his career as a city councilor in Bauru and later became the city’s mayor. He was

When he was still a federal deputy, Rodrigo Agostinho (PSB-SP) stated that he would defend the rights of indigenous people. At his side, great indigenous leader, Cacique Raoni, known internationally for his fight for the preservation of the Amazon and the peoples

elected as a federal deputy for the PSB of São Paulo, where he served in the Environmental Commission of the Chamber, a committee he also presided over. He also coordinated the Parliamentary Environmental Front of the National Congress and was a full member of the National Council of the Environment (Conama) for over 10 years. Furthermore, he is part of the World Commission on Environmental Law of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Beyond his credentials, he has always been passionate about environmental issues, dedicating his public life to protecting water sources.

“I have a passion for rivers. They are trying to eliminate the councils and basin committees, where civil society has a voice. It is through civil society that we advance public policies,” said Agostinho, who was awarded the Velho Chico medal by the São Francisco River Basin Committee (CBHSF). “We must fight to restore dialogue with society and not let decisions be made from top to bottom, as it has been happening.”

Agostinho often says that everything is contained in the 1988 Constitution, which guarantees everyone the right to an ecologically balanced environment, defining it as “a common good of the people and essential for a healthy quality of life.” Thus, he presented a bill in the Chamber to allow individuals and companies to take legal action to stop environmental degradation. The permission

20

Arquivo câmara dos deputados

for any citizen to act in defense of the environment was included in a text approved by the National Congress but was later vetoed by then-President João Figueiredo. “It was vetoed with the argument that ‘it would not be advisable to give everyone the power to request court injunctions to prevent or correct environmental degradation.’ A true mistake, even more so when based on the ‘public interest’,” he explained. In Agostinho’s view: “Over the years, international and national jurisprudence has evolved in the system of guarantees of rights, allowing all citizens to seek in the judiciary the fundamental right to a sustainable environment protected from degradation caused by human actions in biomes, forests, rivers, and oceans.”

As coordinator of the Parliamentary Environmental Front in Congress, the goal was unity: “Our ideal is to work towards adopting tougher measures to combat deforestation, and for that, we need the support of civil society. It is essential that we

keep an eye on what happens within parliament and in Brazilian public policies in general,” he declared at the time. Regarding debates on climate change, he often highlights: “Environmental licensing, dam safety policy, and protection of conservation units will be systematically monitored. We cannot move an inch back in the country’s environmental legislation. We will face mass extinction, and environmental imbalances tend to increase. We need to react.”

At the helm of Ibama, Agostinho is dealing with the new Action Plan for Prevention and Control of Deforestation in Legal Amazon (PPCDAm), a tool originally launched in 2004, crucial for the more than 80% reduction in deforestation in the forest between that year and 2012. According to him, despite the initial success, the plan failed to promote a sustainable development project that offered economic alternatives to the region that did not involve destruction, paving the way for the resurgence of devastation in recent

years. However, in his opinion, the new version will address this while dealing with the more complex scenario of criminality.

“My passion for the environment is what drives me, but the analyses here at Ibama are technical. Now what we need is to have a clear vision of the country’s project, and this is not a decision of Ibama. It is a government decision that needs to be well-balanced,” he commented. “We are seeing the statements from the president, from the minister. Never before has a government spoken so much about sustainability as we are hearing now. It is a great opportunity. Brazil can be a leader in clean and renewable energy, seeking other paths. I am very confident about this. I believe that the future of the country lies there. And the continuity of our existence in this world depends on it. Climate change comes to remind us all the time that either we reconcile with nature, or the consequences will be disastrous.”

21

Alan Rodrigo

Rodrigo Augustine was honored with the medal Old Chico in 2019

Public policy

By: Luiza Baggio

Art: Albino Papa

By: Luiza Baggio

Art: Albino Papa

THE RETURN OF ANA

Central to water resources management in the country and to lead the Sanitation Legal Framework, ANA returns to the Ministry of the Environment

The National Water Agency (ANA), responsible for implementing the National Water Resources Policy in Brazil, has returned to the Ministry of the Environment, which now also includes Climate Change. The transfer is part of a Decree issued after the inauguration of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (PT). The agency returns to the environmental portfolio four years after being linked to the Ministry of Regional Development (MDR), created during the administration of former President Jair Bolsonaro (PL).

The removal of the institution from the Ministry of the Environment and its transfer to the then-new Ministry - a result of the merger of the Ministries of Cities and National Integration - was criticized, mainly for not being discussed with society and for indicating a weakening of the environmental portfolio, as stated by Vicente Abreu, who presided over ANA between 2010 and 2018. “The fact that the entity was linked to a Ministry of an economic nature when water is considered a fundamental resource for the maintenance of human life and the environment was one of the criticisms directed at the Bolsonaro administration due to the change,” he said.

23

CONTROVERSY

In Lula’s government, the main pillars of his third term have been reinforced: democracy, combating hunger, and environmental sustainability. Aware of its importance in this triad, the Minister of the Environment and Climate Change, Marina Silva, demonstrated her strength in the early days of the government when there was a political controversy about which ministry should house the responsibilities of ANA (National Water Agency).

During her inauguration ceremony, while doubts still lingered about ANA’s fate, the minister ensured that it would stay under the Ministry of the Environment. The agency will play an important role, for example, in the new regulatory framework for basic sanitation. This led to a dispute between the Ministries of Cities, National Integration, and the Environment. With the new regulatory structure signed by President Lula at his inauguration, the responsibility to regulate the multiple uses of water is returned to the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change.

Minister Marina Silva stated that ANA was transferred to a “non-place” during Bolsonaro’s administration. “ANA cannot be under a sector that demands permits, as was the case with the Ministry of Regional Development. It must be in a neutral place because the law establishes criteria - first, serving human needs, then animals, and finally other uses,” she said in an interview with Valor Econômico newspaper (January 2, 2023).

BASIC SANITATION

The issue of sanitation is one of the most delicate for the current government, as Brazil is just a decade away from the deadline for meeting the targets established by the Sanitation Legal Framework (Federal Law No. 14.026/2020). According to the law, by 2033, the country must ensure that 99% of the population has access to potable water supply and that 90% of the population is provided with sewage collection and treatment services.

The director-president of ANA, Veronica Sánchez, mentioned the agency’s objectives to achieve the Sanitation Legal Framework. “Despite the acknowledgment of a diagnosis of a still precarious situation regarding access to the service for a large part of the population, we have a great opportunity brought by the new framework, which already attracts investments ten times greater than those practiced so far, and will change the scenario of service provision in Brazil and access to the service by the Brazilian population,” she emphasized.

Veronica Sánchez further explained that ANA’s idea, through the new Sanitation Legal Framework, is to guarantee universal access to services. Thus, it includes new responsibilities for the agency to establish reference standards for sector regulation in the country.

“The Agency will issue standards based on the best national and international practices for the regulation of these services. This will allow subnational regulatory agencies to incorporate these reference standards and improve the quality and standards of service provision in the country through improvements in oversight and the preparation of service concession contracts,” she said.

24

Understand the role of ANA in the environmental agenda

ANA is responsible for granting water use rights in rivers under federal jurisdiction. It also regulates water resources nationwide, establishes reference standards, and manages and controls these grants to ensure the multiple use of water for human consumption, irrigation, and industry without conflicts.

The regulatory agency defines the operation conditions of public and private reservoirs, monitors water levels by measuring flows, and assesses the feasibility of water-related projects using federal resources.

The agency also aims to promote the creation of new River Basin Committees. These committees bring together members of civil society and representatives from the government to discuss water management and encourage the regionalization of service provision.

Since 2020, ANA has also been issuing reference standards for the sanitation sector. However, the agency is not responsible for monitoring the services provided or applying sanctions, as these are tasks for municipal and state regulatory agencies.

Other responsibilities of the agency include regulating irrigation services under concession, water distribution, and overseeing dam safety. The National System of Information on Dam Safety (SNISB) gathers information on dams used for multiple water purposes, electricity generation, containment of industrial waste, and containment of mining tailings.

By: Deisy Nascimento Infrastructure

By: Deisy Nascimento Infrastructure

WHAT ARE YOU

THIRSTY

FOR?

After many years facing water scarcity, the Kariri-Xocó people celebrated the inauguration of the new community water supply system, which includes a water collection unit, pipeline networks, treatment plant, and reservoir. With a cost of almost nine million reais, the project, led by the São Francisco River Basin Committee (CBHSF), will benefit 4,200 indigenous individuals.

26

27

Pedro Vilela

Kariri-Xocó indigenous village, located in Porto Real do Colégio (AL)

It was a special day, celebrated with the Toré ceremony, the traditional dance of the Kariri-Xocó people. On March 31st, the indigenous community, located on the banks of the São Francisco River in Porto Real do Colégio, Alagoas, received a long-awaited project from the São Francisco River Basin Committee (CBHSF): “This is a historic moment for our community, and I thank the Committee for making this dream come true,” said tribal councilor José Eudes Militão. According to Chief José Cícero, the struggle for access to water had been going on for a long time, and the achievement of a water supply system represented a great victory: “Now we have the system here, and everyone will have access. The Committee deserves congratulations. We are very grateful for the project’s implementation.” Naldinho, one of the community leaders present at the event, highlighted: “A compassionate gesture that will improve the quality of life and health for everyone.”

With an investment of almost nine million reais, the new water supply system will benefit about 4,200 indigenous people. The project includes a water collection unit, pipeline networks, a treatment plant, and reservoirs. According to Maciel Oliveira, president of CBHSF, the Committee conducted a diagnosis of the community’s water supply issue in 2017. “The water treatment plant that supplied the community did not have adequate isolation, allowing water contamination from various pathogens,” explained Maciel. “In addition, the low flow of the São Francisco River at that time led to new difficulties in water collection, which was previously done in a low-current area of the river, making it a suitable environment for the accumulation of algae and excess organic matter.”

The following year, in 2018, joint actions were initiated by CBHSF, the São Francisco and Parnaíba Valleys Development Company (Codevasf), the National Water Agency (ANA), and the National Center for Monitoring and Early Warning of Natural Disasters (Cemaden). It was necessary to urgently supply clean water to the Kariri-Xocó people. From then on, the Committee began devising a definitive solution for the water supply issue. According to Anivaldo Miranda, coordinator of the Regional Advisory Board of the Lower São Francisco, a technical cooperation agreement was established that year between the Committee, the Special Indigenous Sanitary District of Alagoas and Sergipe, the Indigenous Community Association Kariri-Xocó of Porto Real do Colégio (AL), and the Peixe Vivo Agency. “This achievement is the result of participative water resources policies, and we at the Committee are pleased to make possible a project that brings dignity,” commented Anivaldo.

Representing the State Secretary of the Environment and Water Resources, Gino César, the Superintendent of Environment, Marcelo Ribeiro, emphasized the importance of the partnership between the São Francisco River Basin Committee and the State Secretary of the Environment and Water Resources of Alagoas (Semarh/AL) for the implementation of significant projects for riverside, indigenous, and quilombola populations. “The Committee deserves congratulations for implementing the water supply system, which will benefit hundreds of Kariri-Xocó people and bring health to all of them,” he said. Érico Gomes, the Federal Public Prosecutor, responsible for Indigenous Populations and Traditional Communities, highlighted the work of the Federal Public Ministry (MPF): “We held meetings and worked to overcome barriers, unite the indigenous people, and resolve other obstacles so that the community could have good quality water in sufficient quantity. We take this opportunity to congratulate the partners and emphasize the importance of this inter-institutional cooperation.”

28

With an investment of almost nine million reais, the new supply system will benefit around 4,200 indigenous people

Culture of Resistance

For countless generations, the Kariri-Xocó people have resisted on the banks of the São Francisco River. In fact, the very name harks back to the genocide that marked colonization and extended into the 20th century. During the Empire period, many groups merged in the region, migrating in search of survival: Xocó, Fulni-ô, Natu, Caxagó, Aconã, Pankararu, Karapotó, Tingui-Botó. In the 20th century, the name KaririXocó emerged from the fusion of the Kariri from Porto Real do Colégio and part of the Xocó from the fluvial island of São Pedro in Sergipe.

In the Toré dances, the Kariri-Xocó preserve this memory of struggle. “To” means sound, and “Ré” means sacred. In the Toré, the songs and dances express historical and cultural events, as well as natural phenomena. The musical instrument is the maraca, played to the beat of the heart. The circular dances represent the circumference of the earth, the sun, the moon, the village, the maloca (communal house), and life.

THE COMPONENTS OF THE SYSTEM

• A floating water intake unit with a pumping capacity of 26 liters of raw water per second;

• 2.2 km of raw water pipeline in PVC-O, with a diameter of 200 mm;

• Three treated water pipelines, totaling 7.2 km;

• A water treatment plant composed of the main treatment stages required for raw water from the São Francisco River;

• A reservoir at the treatment plant with a capacity to store 250 thousand liters of water;

• An elevated reservoir in Ouricuri with a capacity to store 220 thousand liters of water;

• A third reservoir made of reinforced plastic with fiberglass, with a capacity to store 20 thousand liters of water;

• 10.4 km of distribution pipelines;

• Approximately 1,000 metered connections.

29

Edson Oliveira

By: Deisy Nascimento

Infrastructure 30

Edson Oliveira

WATER

TO DRINK

On March 16th, the CBHSF delivered to the city of Piaçabuçu, in Alagoas, at the mouth of the São Francisco River, the so-called “lung tanks,” a robust water collection and storage system that comes to change the reality. During the prolonged drought between 2013 and 2019, the sea intruded into the São Francisco River, causing the salinization of the waters in the region.

Durante a pior seca dos últimos tempos, entre os anos de 2013 e 2019, o Velho Chico perdeu força, correndo fraco rumo à foz, no município de Piaçabuçu, em Alagoas. Com isso, o mar entrou rio adentro, salgando tudo. De repente os moradores da região se viram sem água potável, virando-se com caminhões-pipa e água salobra. Para os pescadores, apareceu peixe de água salgada na água doce. Com a salinização do São Francisco, até a saúde da população acabou afetada, com o aumento de doenças como pressão alta e hipertensão. Desde então, Piaçabuçu enfrentava essa luta, que terminou no último 16 de março, quando a cidade recebeu, do Comitê da Bacia Hidrográfica do Rio São Francisco (CBHSF), os chamados tanques-pulmão, um robusto sistema de captação e armazenamento de “água bruta”.

Segundo o Secretário Municipal de Educação de Piaçabuçu, Guto Beltrão, uma das autoridades a discursar na solenidade de entrega dos tanques-pulmão à comunidade, “a obra é um alento para a população local que vive uma crise hídrica, com água salgada que é imprópria para consumo. Nossa gratidão ao Comitê que uniu esforços para trazer água de boa qualidade à cidade”.

O investimento foi da ordem de 10 milhões de reais, mas, para a dona de casa Maria das Dores, o resultado vale ouro: “A água era muito barrenta, às vezes salobra, cheia de pó, amarela que não prestava para nada. Até para fazer o arroz era complicado e o café ficava salgado”. Para melhorar a qualidade da água de Piaçabuçu, foi instalada uma tubulação adutora, transportando a água do novo sistema de captação para os novos reservatórios. Também foram implantados painéis elétricos, gerando a energia necessária. Ao todo são três reservatórios de 275 m³, totalizando 825 m³ para armazenamento de água. Além das estruturas acessórias para a captação e adução de água, que incluem a implantação de sistema de captação a fio d’água, ocorreu a implantação de elevatória de água bruta, incluindo fornecimento e montagem de plataforma flutuante, ancoragem e dois conjuntos de bombas.

31

“We are receiving a system that will greatly help us in the capacity for raw water storage and improve the water supply to the treatment plant in Piaçabuçu,” said Luiz Neto, the president of the Water and Sanitation Company of Alagoas (CASAL). “For the municipality, it is extremely important to increase the storage capacity to maintain this service provision, at the very least, satisfactory.”

During the inauguration of the lung tanks, Anivaldo Miranda, coordinator of the Lower São Francisco Regional Consultative Chamber (CCR) of the CBHSF, was emotional. On that occasion, he emphasized the importance of valuing water and its planned management, and also demanded more in-depth work from some organizations to defend the São Francisco River and the riparian populations. “The construction of the lung tanks in Piaçabuçu, as well as other projects, is the result of water use fees. It may be little, but

we are managing to redistribute and implement well-planned, prepared, and useful projects within a serious management that help the communities in regions where there is a need for better-quality water,” he said. According to Anivaldo, the idea of building a reserve system was born in the crisis room of the National Water and Basic Sanitation Agency (ANA). “The idea of the raw water collection, conveyance, and reserve system, which will benefit thousands of residents in the region with 100% water supply to the urban area, emerged during the context of the water crisis, from 2013 to 2019 when the flow rates reached 500 m³/s, and the Committee proposed to solve some emergency situations, such as providing water to the population of the region since everyone was consuming salty water,” he commented.

32

Pipeline will reduce salinity of the water in Piaçabuçu

For CBHSF President Maciel Oliveira, the important thing is that Piaçabuçu will return to consuming quality water: “This is one of the major milestones of the Committee and one of the main ongoing projects as it arises from a conflict over water use. The municipality of Piaçabuçu, as well as CASAL, consequently, requested our support in resolving this conflict. All this situation arose due to the constant decreases in the flow of the São Francisco River. The Committee invested over 10 million reais to improve the water quality and the lives of the population.”

Today, almost half of the residents of Piaçabuçu suffer from high blood pressure. The consumption of salty water is a risk to the population and had become a chronic problem in the municipality. The expectation is that the change in water supply will improve people’s health. “The amount of hypertension medications used was 30% higher than in

municipalities such as Penedo and Igreja Nova, which are upstream. The new pipeline will bring more water from the mouth of the river and, consequently, will capture less salty water, and the storage through the tanks will improve the quality of this water,” explained Ângelo Barros, coordinator of the Sanitary Surveillance of Piaçabuçu.

The project will put into operation a system that will be able to supply the urban population of Piaçabuçu (AL) for a horizon of 20 years.

33

Pedro Vilela

STOMACH A SCRIPT THAT TAKES YOU BY THE

In two trips along the Velho Chico, from its source to its mouth, the acclaimed chef Letícia Massula discovered the sophistication and diversity of the Franciscan cuisine, which gains colors and flavors according to the transition of biomes.

By: Karla Monteiro

By: Karla Monteiro

Gastronomy 34

Photos: Letícia Massula

35

Half Minas Gerais, half Goiana, the chef Letícia Massula often uses a measure of “tropeiro” (a traditional Brazilian dish) in her journeys: four cheeses and one rapadura (a type of sweet made from sugarcane juice), with refueling on the road. Between 2014 and 2016, she embarked on two long journeys. In the first one, she crossed half of Brazil, always along the banks of the São Francisco River, from its source in Serra da Canastra, Minas Gerais, to its mouth in the city of Piaçabuçu, Alagoas. In the second journey, also along the Velho Chico, her destination was the mythical Canudos in Bahia. According to Letícia, good food was never lacking. From Minas Gerais to Alagoas, crossing five states, she discovered the sophistication of the riverine cuisine. As the biomes transition, the food transforms without ever losing its flavor.

“We slept wherever we could. If the place was nice, we stayed for a while. For me, these are research trips. I always focus on what people eat,” she said: “I usually observe food from a social point of view. Cuisine is not disconnected from infrastructure.”

Cooking emerged in Letícia’s life as an escape from the corporate world. A lawyer by training, she decided to quit everything and try her luck as a cook. In 2007, she started Cozinha da Matilde, a backyard experience. The name of the small restaurant in Vila Madalena, a neighborhood in the West Zone of São Paulo, paid homage to the poet Pablo Neruda and his partner, the lyric singer Matilde Urrutia, for whom he wrote “Cem Sonetos de Amor” (One Hundred Love Sonnets). With three accomplices, the idea was to live in a house with a garden and receive customers under the jabuticabeira tree. From there, a blog was born, mixing gastronomy and poetry, music, and drinks to accompany. Then, opportunities arose to host TV shows: “Brasil CookBook” on the BBC network, “Receitas Brasil” on the Sony channel, and “Trivial Perfeito” on TV UOL. Amidst all this, Letícia finds time to hit the road.

“The first time we traveled along the São Francisco, it was in June. It’s wonderful, everything is connected to the June festivals. End of harvest, fire at the doors of houses, a whole symbolism. Very beautiful to enter the backlands at this time of year. Time of abundance,” she commented. “The second trip happened at the end of the year. It’s completely different. Everything changes. In my opinion, the most beautiful sunset of the Velho Chico is in the city of São Francisco, near Januária, in Minas Gerais. We arrived just as the sun was setting.”

36

Chef Letícia Massula, on one of her journeys through the Velho Chico basin.

Manauê Cake, popular in the backlands

Letícia’s first journey began in Canastra, where, of course, she indulged in tasting tours of cheese dairies. “We left there with a contraband of more than 30 cheeses in the trunk,” she joked. As her memory serves her well, in this part of the road, the main dish is perhaps fried fish, in addition to countrystyle chicken and pork: “This connected me a lot with my childhood on the banks of the Paranaíba River in Goiás.”

Crossing Minas Gerais, the dairy culture also catches the eye, with sweet milk desserts served with cured cheese and other delicacies, such as sweet milk with jiló (a type of vegetable), and of course, cheese bread. As she enters Bahia, the focus shifts from cowboy tradition to beef cattle culture. “The way of interpreting the animal changes completely,” Letícia commented: “At this point, the art of carne de sol (sun-dried meat) begins. Originally, the backlands had no salt for jerky, as it was far from the coast. So, what was learned? They learned to open the meat and let it dry in the wind and shade. The so-called ‘carne serenada’ (serenaded meat). The curing is guaranteed by the wind and dry climate.”

For Letícia, the beauty lies precisely in this connection between cuisine and the transition of biomes. “The pão de queijo (cheese bread) disappears, and the sweet polvilho biscuit comes in, for example. We also experience a phenomenal work with manioc. The beiju houses are absolutely surprising.” According to her, there are about seven different types of delicacies made with manioc, with or without coconut, with or without sesame, salty or sweet, dry or wet. The most impressive thing is the taste of cheese without actually using cheese in the recipes, just by adjusting the fermentation. Another peculiarity that caught her attention was the culture of goat. She had never eaten so much goat prepared in so many different ways. “A very interesting place is the market in Aracaju. There, you can find both the backlands and the coast,” she pointed out. “If you go up to Itabaiana, they have the manauês. They look a lot like the mané pelado (a traditional Minas Gerais dish). Very creamy corn cakes.”

Stopping here and there, Letícia saw the profound sophistication in the simplicity of riverine gastronomy. In the face of scarcity, they seek varied flavors using the same ingredient. In the morning, roasted corn replaces bread. At night, it becomes a snack to accompany cachaça (Brazilian liquor), alongside fried fish. “The backlanders waste nothing. If they kill an animal, be it a pig, a cow, or a goat, they use the organs for broths, the guts for sausages, and so on,” she emphasized. Along the way, even the types of flour change: “In Minas, corn flour, fubá. In the backlands, sour flours, with larger grains. The backland bakeries are very interesting, with unleavened rolls.” In the summer, the attraction is the fruits: “Sweet milk with pequi (a fruit). Thickened milk with pequi. Pequi porridge. Sweet milk with jatobá (another fruit).”

Ending by the seashore, Letícia concluded: “The ideal is to travel without haste, stopping at markets, fairs, and talking to people. There’s so much history, so much food culture, so much sophistication. The ways of dealing with ingredients are impressive. The semi-arid reminds me of the Mediterranean. I get upset when people say the backlands are a place of misery. The backlands are a place of resistance.”

37

By: Karla Monteiro Photos:

SEED CERRADO

At the Educational Nursery of the Inhotim Institute, the largest open-air museum in the world, located in Brumadinho, Minas Gerais, more than 280 Cerrado species are hidden within the lush biodiversity. In partnership with the Public Prosecutor’s Office of Minas Gerais, the “Being of the Cerrado” project aims to provide visitors with an experience of discovering the biome.

tourism 38

Léo Boi

39

ÀAt first sight, an endless exuberance is perceived: palm trees of many species, lush trees, luxurious foliage, a mixture reminiscent of the contemporary chaos of Burle Marx’s gardens. How to enter an Atlantic Forest Oasis in the heart of Brumadinho, a Brazilian city that gained fame with the tragedy caused by the dam breach of Vale in January 2019?

Inaugurated 17 years ago, the botanical garden of the Inhotim Institute, considered the largest open-air museum in the world, stretches over 25 hectares of land, containing approximately 4,300 native Brazilian and exotic species from various parts of the world. In total, the museum covers more than 140 hectares of visitation area, along with a private reserve of 250 hectares. Amidst all this, according to the biologist in charge, Sabrina Carmo, lies the discreet beauty that Inhotim now wants to reveal with the project “Being of the Cerrado,” carried out in partnership with the Public Prosecutor’s Office of Minas Gerais.

“When visitors arrive at Inhotim, they don’t see the Cerrado. However, we are located in a transitional area between the Cerrado and the Atlantic Forest. So our goal with the ‘Being of the Cerrado’ project is to train the eyes of visitors so that they get to know, value, and protect the Cerrado,” said Sabrina. “We don’t have the Cerrado from the north of Minas, the Cerrado from Goiás, but we also have Cerrado, because the Cerrado is diverse.”

Sabrina, responsible for the botanical garden of Inhotim, guided us through what she calls the “experience” of the Cerrado, through the Educational Nursery, a space where scientific research, environmental education, and landscaping converge. Contrary to what one might imagine, native species of the biome are not displayed like works of art hanging on the walls of the museum galleries but are nestled in the vast territory occupied by diverse vegetation. Suddenly, grass, cacti, and Cerrado flowers appear, and Sabrina

points them out as if she had just found Waldo: “We chose the nursery space to place some content or strategy related to the Cerrado in every corner,” she commented. Many of the plants have a QR-Code, for example, to access information about the species and its relationship with the biome.

“So, the project is this: a line of educational work combined with a line of collection improvement,” Sabrina summarized.

Walking through the paths of the Educational Nursery, the first stop is the “Garden of All Senses,” with plants that can be smelled and tasted. Next comes the “Desert Garden,” which reproduces the challenge of survival in dry and sunny lands. Then, the “Transition Garden,” the celebrated encounter of the Cerrado with the Atlantic Forest, with trails adorned by a mosaic of botanical species representative of both biomes.

40

Finally, the “Meliponário,” housing five species of stingless bees: Iraí, Jataí, Mirim-Droriana, Mandaçaia, and Moça Branca. According to Sabrina, these indigenous bees play a fundamental role in nature as pollinators: “The Meliponário is the last thematic garden we inaugurated, dedicated to stingless bees. They are native bees of the Cerrado. The world is facing a pollinator crisis. In Brazil, talking about stingless bees is urgent. Talking about stingless bees from the Cerrado is even more urgent.”

With the “Being of the Cerrado” project, the Inhotim Institute increased its collection of Cerrado plants by 110 species, totaling 280 species. Additionally, it has a laboratory dedicated to seed collection and seedling production. In this restricted area, there are large freezers and hundreds of seed boxes. According to biologist Naiara Mota, if the Cerrado disappears outside, Inhotim can

contribute to its repopulation. The dystopian scenario is not far-fetched, to tell the truth. Between August 2020 and July 2021, the Cerrado lost an area equivalent to almost twice the size of the Federal District. Over 8,500 square kilometers of native vegetation were deforested, the largest devastation since 2016. “The Cerrado is a biome that has been suffering from an absurd deforestation rate. In the latest report from 2021, 57 hectares of Cerrado were lost per hour.”

41

Sabrina Carmo, biologist at Inhotim

Archeology

CITY LOST

By: Arhtur de Viveiros

Have you ever heard of the Village of Santo Inácio?

Located in the Bahian backlands, the small village, a district of Gentio do Ouro, may be the lost city of the French explorer Apollinaire Frot, who followed the footsteps traced in the mysterious “Manuscript 512.”

42

Photos: Fernando Piancastelli

43

View of Toca da Coã Santo Antônio, in the village of Santo Inácio

It sounds like something out of Indiana Jones: could the small Village of Santo Inácio, a district of Gentio do Ouro in the Bahian backlands, be the famous “Lost City”? Just over a century ago, after a long search expedition, the French explorer Apollinaire Frot made notes with clues that indicate it might be. Or rather, perhaps. He followed the footsteps traced in the mysterious “Manuscript 512,” containing the account of a bandeirantes expedition that supposedly resulted in the discovery of a mountain of crystals and ruins of a settlement inhabited by descendants of the continent of Atlantis. The manuscript had been buried in the Court Library, now the National Library, and was discovered in 1839 by the Brazilian naturalist and writer Manuel Ferreira Lagos (18161871). The “Manuscript 512” had already inspired and would inspire other travelers. In 1865, the British consul Richard Burton traveled from the Central Plateau to Paulo Afonso, descending the São Francisco River by canoe. And in 1927, Percy Harrison Fawcett set off from Cuiabá towards Bahia. He would never arrive. He disappeared mysteriously in the jungles of Mato Grosso, along with his son and a travel companion. His last communication occurred nine days after departure. Recently, in 2018, the Spanish explorer Juan Francisco Cerezo Torres also undertook the search journey and came to the conclusion that the Village of Santo Inácio could indeed be the “Lost City” of Apollinaire Frot.

The mystery behind “Manuscript 512” has also inspired literature. The English writer Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930), creator of the detective Sherlock Holmes, wrote “The Lost World.” And the Brazilian novelist José de Alencar (1829-1877) penned “The Silver Mines.” Whether the Village of Santo Inácio is truly the fictional place indicated by “Manuscript 512” and discovered by Apollinaire Frot has never been proven, but the legend itself is worthwhile. Surrounded by waterfalls and privileged views of the São Francisco River, the village now has 300 inhabitants, situated on the shores of Lake Itaparica, the largest marginal lagoon of the São Francisco River

The Contemporaries

The first inhabitants of the Santo Inácio region were the indigenous peoples Cariris, Tupinambás, and Amoipiras, whose marks can be found in the sandstone massifs surrounding the city. During visits, tourists come across millennia-old rock paintings, most of them well-preserved, but some have already faced recent human interventions, such as graffiti and names carved into the rocks.

The history of Santo Inácio has very peculiar aspects, linked even to the intense mining activity of Gold, Diamond, Crystal, and Carbonate, which began in the region in the mid-1850s. The records of the first economic activities date back to 1836, precisely related to mining. Until then, the locality was inhabited by indigenous people. According to 84-year-old resident Helenita Bessa, who keeps a notebook with important records of the city’s history, the village began to be structured in 1911 with the construction of its first building, known by residents as “Convent.” From there, other structures were built, such as the church in 1913, the school in 1949, the prison, which is currently in ruins, in 1950, and the cemetery in 1951. The “growth” was due to the flow generated by mining in the region.

44

Santo Inácio dam

Rock paintings

45

Center of Santo Inácio, with buildings from the 1920s

Step by Step

Toca de Santo Antônio

After crossing the village and facing a vertical walk amid the rocks of a large sandstone massif, a typical formation of the region, the visitor arrives at a region of fine white sand where, just ahead, is the entrance to Toca de Santo Antônio. A small natural cave houses an image of the saint, which, due to acts of vandalism, is no longer in perfect condition. Nevertheless, the place seems integrated with nature, with dried trees forming a kind of “altar” covering.

After passing the cave, it is possible to see, from a privileged spot, Lagoa de Itaparica. Located in Xique-Xique, a neighboring municipality to Santo Inácio, it is the largest marginal lagoon of the São Francisco River, a true natural nursery since, during the Piracema period, when fish swim upstream to spawn, the lagoons are where the eggs are laid.

Cruzeiro

Upon leaving Toca de Santo Antônio, the itinerary proposed by the guide Daniel Leite, 16, proceeds to the visit to Cruzeiro. No longer under the fine sand, the walk continues among the rocks, with the sound of strong wind resounding in the ears until the visitor reaches a cross approximately three meters high, set into the rocks, blessing the city in the background. From this point, it is possible to clearly see the entire village and once again, Lagoa de Itaparica.

Toca da Coã