Plains to School

A Conceptual Shared Use Path for Easthampton Students and Residents Galen Hammitt and Walker Powell

The Conway School of Landscape Design Spring 2020

And, of course, heartfelt thanks to our families, who gracefully adapted to our new athome schedules and remained completely supportive throughout.

Photo by Walker Powell

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

Thank you to our fellow students, the faculty, and the staff of the Conway School, for being so supportive and working together to make this strange upside-down spring term a truly great one. The community we have created is a truly special one.

CONTENTS PAGE TITLE

We would like to extend our gratitude to Jeff Bagg, Easthampton City Planner, for all of his guidance, support, and advice. Easthampton is lucky to have such an inspired and forward thinking planner and we are honored to have aided in his vision. Sincere thanks to Scott Cavanaugh for his advice and to Gerrit Stover for a wonderful day spent bushwhacking through the woods and his many helpful maps.

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

Acknowledgments

INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................1 OVERVIEW OF PROPOSED ROUTE............................................................2 HISTORICAL CONTEXT................................................................................3 PHOTO TOUR: SOUTH................................................................................4 PHOTO TOUR: NORTH................................................................................5 CONNECTIVITY.............................................................................................6 HYDROLOGY................................................................................................7 SLOPES AND DRAINAGE.............................................................................8 SOILS..........................................................................................................19 REGIONAL VEGETATION AND WILDLIFE .................................................10 NEIGHBORHOOD VEGETATION AND WILDLIFE .....................................11 SUMMARY ANALYSIS.................................................................................12 DESIGN ALTERNATIVES.............................................................................13 COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT....................................................................14 FINAL DESIGN: Shared-Use Nature Path..................................................15 FINAL DESIGN DETAIL: Plain Street .........................................................16 FINAL DESIGN DETAIL: Plain Street Parking ............................................17 FINAL DESIGN DETAIL: Chicoine APR.......................................................18 FINAL DESIGN DETAIL: Holly Circle Wetland............................................19 FINAL DESIGN DETAIL: Fill Site.................................................................20 FINAL DESIGN DETAIL: Natural Playground..............................................21 FINAL DESIGN DETAIL: River Valley Way..................................................22 FINAL DESIGN DETAIL: White Brook School.............................................23 FINAL DESIGN DETAIL: Nonotuck Park Connection North.......................24 FINAL DESIGN DETAIL: Park Street Trailhead ...........................................25 FINAL DESIGN DETAIL: Park Street Spur...................................................26 FUNDING SOURCES..................................................................................27 MATERIALS AND PRECEDENTS................................................................28 NEXT STEPS AND FUTURE CONNECTIONS............................................29

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

School Consolidation In 2018, voters approved a plan to construct a new school for all Easthampton pre-K through eighth grade students, to be built at the site of the current White Brook Middle School. Students who would otherwise attend school at four different elementary schools will attend the White Brook School beginning in 2022. This consolidation will lengthen the commute for some students, and will shorten the commute for others. After the consolidation, students living in south Easthampton, a neighborhood colloquially known as the Plains, will be within walking distance of school. However, existing infrastructure for pedestrians and bicyclists between the Plains and the White Brook School is lacking, meaning students may be dependent on transportation by car or bus to get to school. The planned school consolidation has raised interest in creating safe routes for students to walk or bike to school. In 2019 and 2020, the city’s planning department commissioned a set of studies by students at the Conway School of Landscape Design in Northampton to help envision new pedestrian and bicycle routes for students and residents of Easthampton.

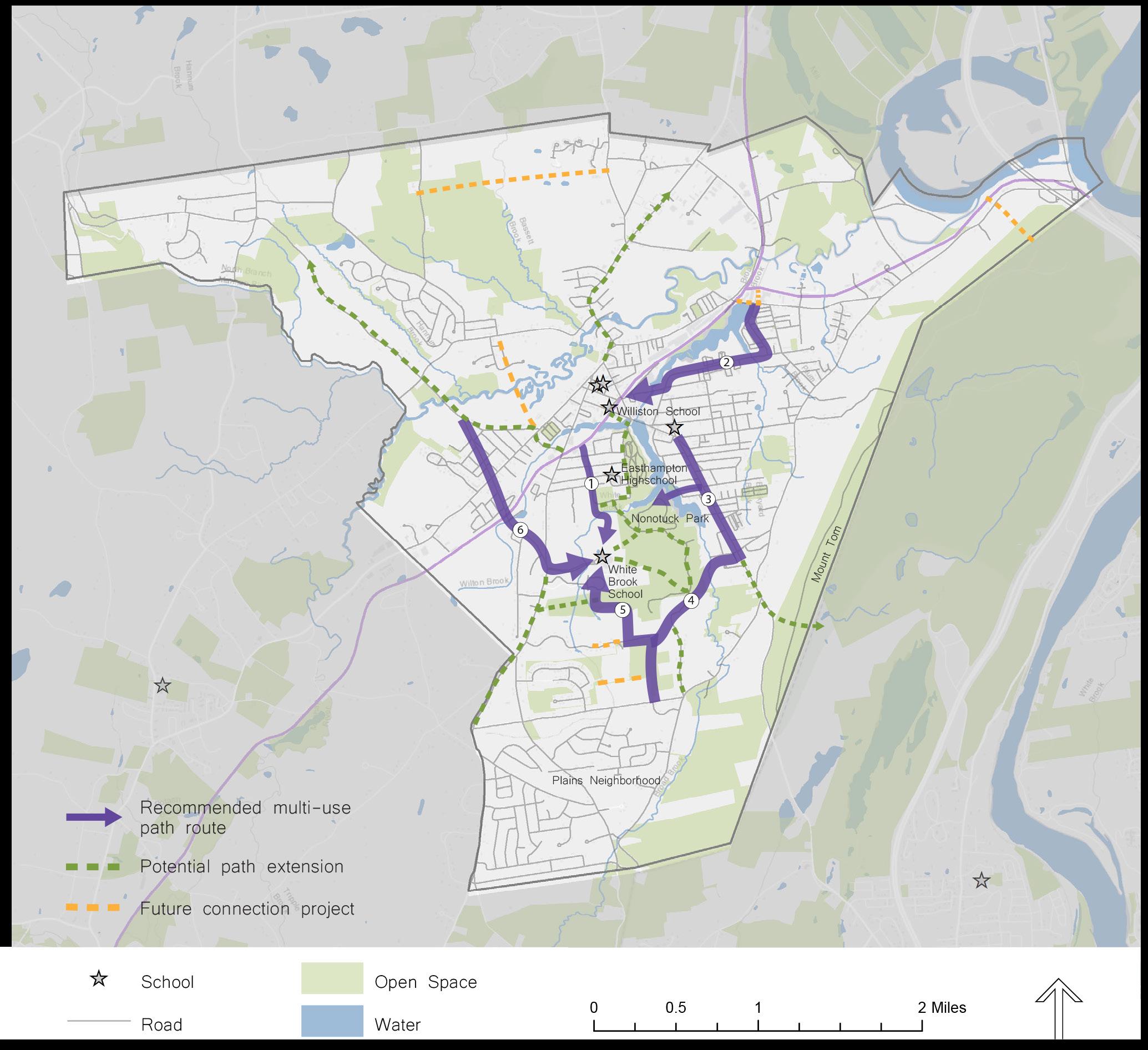

Emerging Pathways: A Conceptual Multi-Use Trail Network (2019) In 2019 a team of students conducted a preliminary study to assess the existing infrastructure for pedestrians and bicyclists and determine potential routes to connect residential neighborhoods to the downtown area, the new school, and protected green spaces. The report found that the Manhan Rail Trail, built in 2004, “provides safe

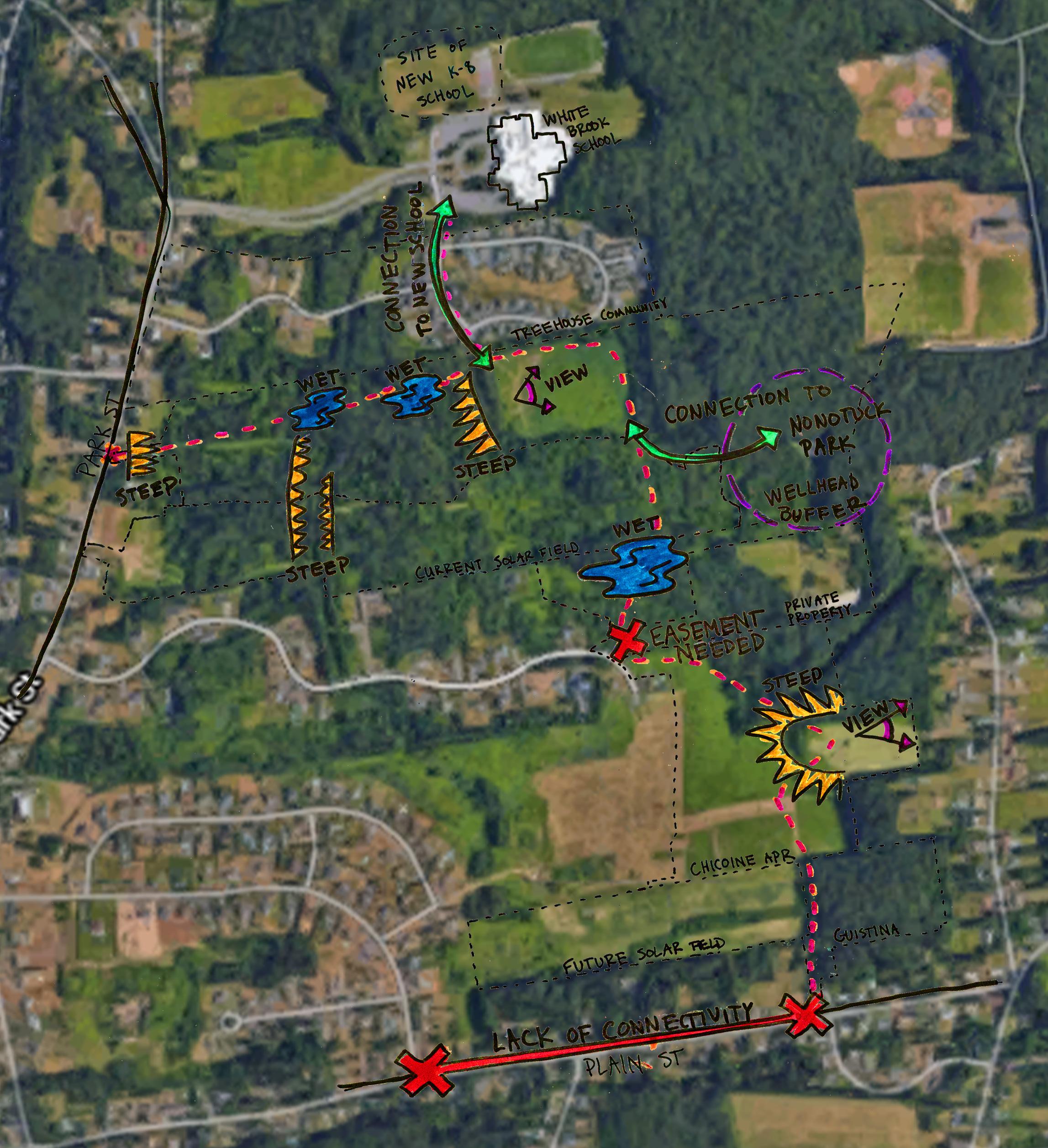

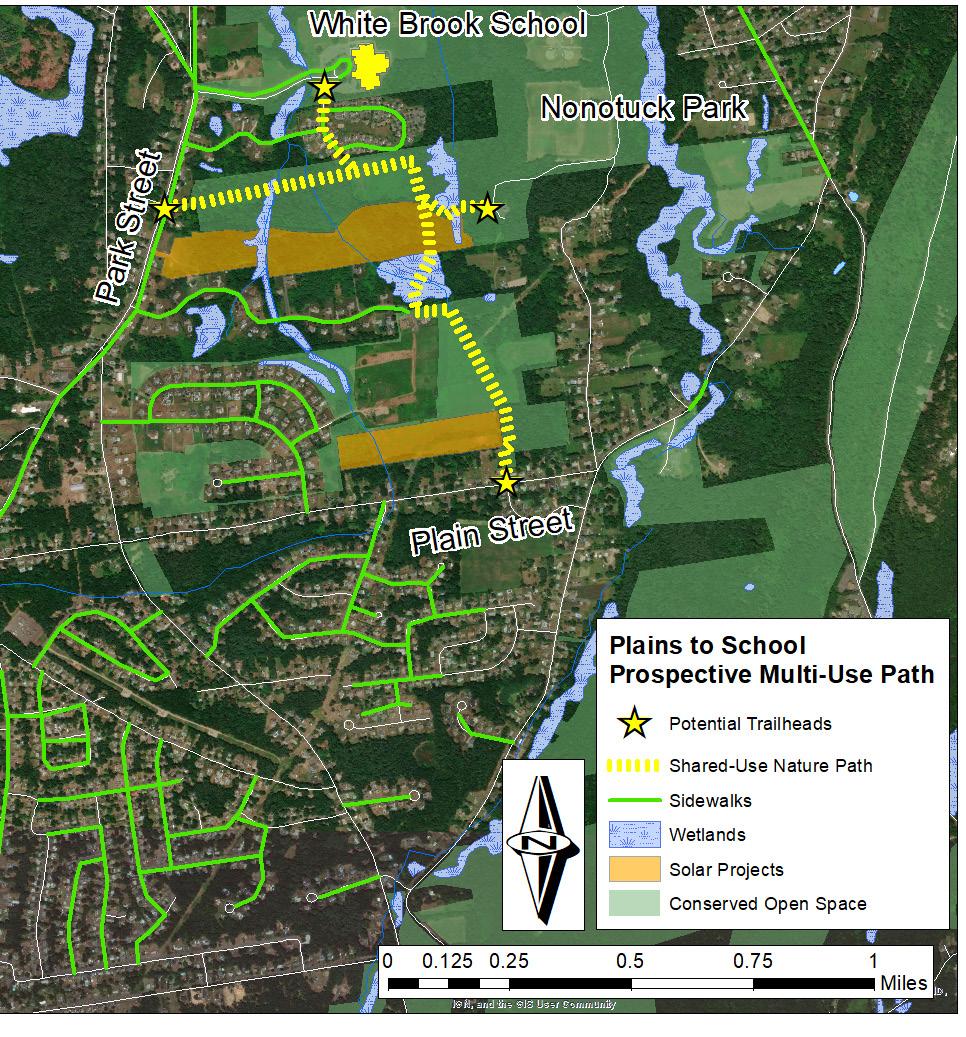

A network of multi-use trails proposed in the 2019 Emerging Pathways report. The Plains to School project provides a detailed examination of the proposed Route 5 connecting the Plains to the White Brook School.

walking and cycling infrastructure and supports non-motorized transit,” but elsewhere, “dilapidated sidewalks, narrow streets, and high-traffic roads within Easthampton obstruct safe, continuous pedestrian and bicycle movement through the city” (Gessinger, 3). The authors propose a network of multi-use path segments to improve pedestrian and bicyclist mobility throughout the city by improving infrastructure along existing roadways and developing new paths through conserved open spaces. The Plains to School project provides a close examination of a single route proposed in

the Emerging Pathways study to connect pedestrians and cyclists in the Plains to the White Brook School and Nonotuck Park (route 5 in the map above). The goals of the Plains to School project are to assess the feasibility of the proposed route, consider alternative routes, gather community feedback, and create a preliminary design for an accessible path between the Plains and the White Brook School.

1

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

This commitment to pathways is strongly represented in the city’s 2008 Master Plan. Both the 2008 Master Plan and the 2013 Open Space and Recreation Plan list connecting the Manhan Rail Trail to schools and other community facilities as a high priority. The Master Plan identifies increasing bicycle and pedestrian connectivity and walk-ability within the city is a top strategy for revitalizing downtown. According to the plan, the Manhan Rail Trail has greatly benefited the city by encouraging development in the downtown mill area, raising land values near the trail, attracting visitors to the downtown, and increasing walk-ability for Easthampton residents.

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

The city of Easthampton is committed to providing safe and pleasant walking and biking trails for the utility and enjoyment of city residents. In a survey conducted for the 2013 Open Space and Recreation Plan, 91 percent of respondents listed nonmotorized trail use as a favorite activity, and 55 percent of respondents listed new nature trails as the city’s greatest recreational need (OSRP, 60). Easthampton has many popular recreation areas including the Manhan Rail Trail and Nonotuck Park. There is a recognized need to connect these assets to one another, an to schools and neighborhoods throughout Easthampton. There is also a need for more universallyaccessible trails so that all Easthampton residents can access natural areas. The second listed community goal in the OSRP is to create a network of connections to the Manhan Rail Trail as well as adding parks and open spaces.

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

INTRODUCTION PAGE TITLE

A Commitment to Pathways

B C

D

E F

Treehouse Circle

d

Button Roa

H

Giustina Conservation Area. This 9-acre parcel was acquired by the city in 2005 with the assistance of Pascommuck Conservation Trust. The Giustina Conservation Area is entirely forested, with the exception of a cleared corridor in the southwest corner that connects to Plain Street. Though the city is interested in promoting public access, there are currently no established trails, and the site sees little recreational use.

G F

Tomaszewski Solar Site. This 16-acre privately-owned parcel is in the early stages of being developed into a solar field. The developers plan to build an access road through the cleared corridor on the west side of the Giustina Conservation Area. White Brook APR. This 25-acre parcel is one of the few remaining agricultural areas in the White Brook area. The land protected under an Agricultural Preservation Restriction, which prevents any use that would detract from its agricultural value. It is owned by the Chicoine family who raise grass-fed beef, pork, and chicken at their farm on Oliver Road in the northwest Easthampton. There is currently little agricultural activity on the White Brook APR aside from hay production in the upper pasture on the eastern side of the property. The Chicoines are interested in providing increased public access to the White Brook APR and helping to preserve the rich agricultural traditions of Easthampton. They have granted the city an easement to establish a path from the southern edge of the property to the outlet on Holly Circle in the northeast corner of the property. The existing easement is only 8 feet wide because it was originally intended for a simple walking path, so the City would need to negotiate a wider easement to accommodate a shared-use path. The area immediately west of the White Brook APR is slated for residential development that would connect Crestview Drive to Holly Circle. Private Residence. The driveway of this private residence extends eastward from the end of Holly Circle and divides the White Brook APR from the city-owned open space to the north. This is currently the only parcel along the proposed route that isn’t owned by the City or for which the City hasn’t acquired an easement. At the time of writing, discussions between the City and the homeowner are under way. Holly Circle Open Space. This 9-acre city-owned parcel contains a large wetland and a historic grove of hemlock trees. The site currently difficult to access due to the wet conditions and dense vegetation. Any construction or disturbance to this sensitive area would need to be permitted and approved by the Easthampton Conservation Commission. Park Street Solar Site. At the time of writing, private developers were nearing completion of a large solar field. The private landowners have granted the City an easement to cross the parcel towards the eastern edge.

D

E cle

Holly Cir

C

w tvie

s Cre

ve

Dri

B

A

The route proposed by the 2019 Emerging Pathways study takes advantage of a series of conserved open spaces to connect the Plains and White Brook School. Park Addition. This 64-acre, cityG Nonotuck owned parcel is mostly forested except for an

open area south of River Valley Way where the City deposited approximately 250,000 cubic yards of soil that were dredged from Nashawannuck Pond around 2005. The mound of fill is up to 10 feet tall and vegetated with goldenrod and other early successional meadow species. Existing paths skirt around the mound of fill connecting River Valley Way to the trails of Nonotuck Park. The Nonotuck Park Addition extends westward across the central and western branches of White Brook to Park Street, raising the possibility of a

secondary path connecting to a trailhead on Park Street.

H River Valley Way and the Treehouse

Community. River Valley Way, Button Drive, and Treehouse Circle are home to a number of private residences, as well as the Treehouse Community, a multi-generational community that supports families with adopted children.

I

White Brook School. At the time of writing, construction is underway on the new K-8 School.

2

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

A

EXISTING CONDITIONS PAGE TITLE

The Emerging Pathways report identified a series of conserved open spaces in the White Brook area north of Plain Street, and envisioned an accessible shared-use path connecting the Plains to the White Brook School through woodlands and fields well away from the traffic of main roads. The following is an overview of the proposed route.

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

I

An Accessible Path Through White Brook’s Natural Areas?

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

OVERVIEW OF PROPOSED ROUTE

The land use patterns in the White Brook area impact the character and environment of Easthampton. As agricultural use has declined, open fields have been replaced with residential developments or have regrown into young forests. Pavement and other impervious surfaces constructed for new development in this area contribute to rising urban temperatures and diminish the land’s capacity to absorb storm waters. Forests and unused agriculture fields sequester atmospheric carbon, absorb storm water, and provide wildlife habitat. Conserving natural areas from development will help mitigate rising temperatures and flooding in Easthampton in decades

Pre-1600: Connecticut River Valley inhabited by the Pocomtuck people. A group known as the Norwottucks live on the shores of the Oxbow in present-day Easthampton. 1664: First white settler builds a home in Easthampton. 1847: Samuel Williston builds the button factory which still stands in Easthampton. Broad Brook is dammed to power the mills, creating Nashawannuck Pond, Rubber Thread Pond, and Lower Mill Pond. Circa 1850-1974: White Brook Area remains clear for agriculture. 1975: White Brook Middle School built. 1990: Development of Kingsberry Way. Early successional forests begin to grow. 2001: Development of Holly Circle. 2006: Development of Button Drive. 2019: Five acres cleared for the Park Street Solar Array. 2022: Construction of the White Brook K-8 School to be completed.

3

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

The land between the Plains and Nonotuck Park was cleared of forest for European-style agriculture by the mid-nineteenth century when the mill industries were built in Easthampton and the city’s population continued to grow. This area remained largely clear of forests throughout most of the twentieth century. Aerial photographs from 1942 through 2018 show the amount of land in agriculture production declining dramatically beginning around 1990 as some areas are built into low-density residential areas while others grew into early successional forests.

Timeline

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

The White Brook area has likely been cleared of native forest for Europeanstyle agricultural production for most of the last two centuries. Prior to its settlement by white Europeans, the Connecticut River Valley was home to the Pocumtuck people. There were an estimated 1,200 to 1,600 Pocumtucks living in the Connecticut River Valley at the beginning of the seventeenth century, but their population rapidly declined as people died from introduced epidemics and were dispersed by conflicts with the colonists. The Norwottucks, a local group affiliated with the Pocumtucks, likely fished and practiced light agriculture on the fertile lands around the Manhan River.

to come. While construction of a shared-use path would increase development and poses a disturbance to these natural areas, it would also allow for public access and foster greater appreciation and value for this beautiful landscape.

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

Land Use History

HISTORICAL CONTEXT PAGE TITLE

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Above: The Holly Circle wetland could present a challenge for building a path in this location.

Above: The access road to Giustina Conservation Area is on Plain Street across from Apple Tree Lane.

G

B

H

Above: A wooded edge marks the boundary between the Giustina Conservation Area the Tomaszewski solar site.

F

G

Above: This hemlock grove is one of the most mature forests in the White Brook area.

E

H

D C C B A Above: The White Brook APR field is flat and open but the soil is poorly drained.

Above: Views of the solar field offer an opportunity for learning about sustainable energy.

4

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

F

PHOTO TOUR: SOUTH PAGE TITLE

Left: The city is in discussion with the owner of this private parcel to negotiate an easement across the property.

E

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

A

Right: The view from the upper hayfield in the APR parcel is spectacular.

D

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

PHOTO TOUR: SOUTH

G C B

F E

C

Above: A sidewalk along River Valley Way connects the Nonotuck Park Addition to the White Brook School.

Above: The east branch of White Brook flows through this lush wet meadow within the Nonotuck Park Addition.

D

B

Above: The Nonotuck Park Addition contains a mound of fill from the dredging of Nashawannuck Pond around 2005.

F

G

H

A

Above: A shady, open woodland has grown in on the Nonotuck Park Addition since it stopped being cleared for agriculture.

H

Above: Emerging from the forest offers another spectacular view of Mt. Tom beyond the mound of fill.

5

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

Above: This wooded pool is a beautiful natural feature within the Nonotuck Park Addition.

Left: A hill descends from the road where the Nonotuck Park Addition meets Park Street.

PHOTOPAGE TOUR: NORTH TITLE

E

D

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

A

Right: The current middle school is shown in front of the construction site for the new school.

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

PHOTO TOUR: NORTH

Currently, the only contiguous pedestrian route that connects the Plains to other parts of Easthampton is the sidewalk on Park Street. Residents who don’t feel comfortable walking or cycling alongside cars have very limited options for traveling to and from the Plains without using a car themselves. Creating a new shared-use path away from vehicle traffic will dramatically improve people’s ability to come and go from the Plains without relying on motorized transportation.

Right: yellow numbers indicate the number of times streets in the Plains were reported as unsafe or uncomfortable by survey respondents.

CONNECTIVITY PAGE TITLE

The City of Easthampton aims to improve walking and cycling infrastructure within the Plains. The 2017 Complete Streets Prioritization Plan calls for the construction of new sidewalks on Plain Street, Strong Street, Phelps Street and Pomeroy Street, as well as a bike lane on Line Street and Park Street.`

6

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

While most of the secondary streets within the Plains have sidewalks, none of the main roads do except for Park Street and Line Street. There are no designated bike lanes within the Plains. In a survey conducted to gather community feedback on the experience of walking and biking in the Plains, residents reported that the quieter roads with sidewalks are pleasant to use, but the main roads feel unsafe due to the lack of sidewalks, the heavy traffic, and speeding drivers. The roads that were most frequently cited as being unsafe or uncomfortable are Park Street (even though it has a sidewalk), Plain Street, Strong Street, and Hendrick Street.

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

Pedestrian and Bicyclist Infrastructure

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

CONNECTIVITY

Given the abundance of hydrological features and the constraints of the conserved parcels of land, it is not possible to build a path that completely avoids the hydrological resource protection areas. However, paths can be built through these sensitive natural features using techniques that minimize negative impacts to the local hydrology and ecology. (See sheet 29 for precedents and construction details.)

Water from Mount Tom and the highlands west of Easthampton drains through the Manhan River and its tributaries northeast through the city and empties into the Oxbow and the Connecticut River.

HYDROLOGY PAGE TITLE

Throughout the White Brook area, wetlands form along the brooks in pockets of poorly drained soil. These important natural features absorb excess water during storms, filter pollutants out of storm water, provide habitat for wildlife and wetland plants, and sequester atmospheric carbon dioxide. Perennial streams and wetlands are regulated under the Wetlands Protection Act, and any development or disturbance within the resource protection area requires permitting and approval from Easthampton’s Conservation Commission. There are likely additional wetlands within the area not identified by this study, which would need to be professionally delineated as part of further planning for any path through this area.

7

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

The entirety of Easthampton is located within the watershed of the Manhan River, which drains the land northeast of Mount Tom into the Oxbow and the Connecticut River. White Brook and Broad Brook are tributaries of the Manhan River, which flow through the Plains and northward through the study area before draining into Nashawannuck Pond.

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

Abundant Streams and Wetlands Impact Path Design

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

HYDROLOGY

A Gently Rolling Plain, Shaped by Water The landscape of the White Brook area is mostly level or gently rolling. Water from the steep slopes of Mount Tom and the highlands southwest of the Plains flows across the landscape and into the brooks that drain the Plains and fill the mill ponds. The various branches of White Brook have carved channels into the landscape over time, creating steep stream banks in places. The steep slopes in the area are generally aligned along a north-south axis, paralleling the brooks. The landscape between Plain Street and the White Brook School can be traversed without crossing any steep stream banks or any other slopes that would pose a major challenge to constructing an accessible shared-use path. The landscape between Park Street and Nonotuck Park poses more significant, though not insurmountable, challenges because the direction of travel from west to east requires crossing some hillsides and stream banks aligned with White Brook.

In order to accommodate an accessible path across this landscape, these slopes will have to be careful considered and the land may need to be regraded in places.

Right: cross-section showing areas of steep slopes between Park Street and the fill mound.

A

A’ 15%

>15%

15%

8

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

The section below shows the slopes of the Nonotuck Park Addition parcel from Park Street eastwards towards the mound of fill. From Park Street the landscape of the Nonotuck Park Addition descends a hillside towards White Brook. Much of the hillside is around a 5% grade, but the first 100 feet east of Park Street are sloped at a 15% grade. Further east, the landscaped descends gently until it reaches the western bank of White Brook. Here, the stream bank ranges in slope from 15% to as much as 40% in places. The slopes of this stream bank are less severe towards the northern edge of the parcel. The landscape between the western and central branches of White Brook is low and wet with no significant slopes. East of the brooks, a hill with a grade of 15% ascends to the mound of fill south of River Valley Way.

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

A

Navigating Hills and Stream Banks

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

A’

PAGE SLOPES TITLE

SLOPES AND DRAINAGE

In other areas of the potential corridor, well drained and sandy soils present a different set of challenges to trail construction and maintenance. Sandy soils are light and erode easily, so areas of the trail that are located on or near slopes may have a higher incidence of erosion during construction if proper erosion control measures are not taken. Design strategies for minimizing the potential for erosion include: grading the shoulder of the trail to less than 33%, ensuring all sloped areas are vegetated, and using erosion control mats during plant establishment. Proper placement of the trail and management of water runoff will also help reduce erosion.

9

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

Issues such as ponding and flooding are challenges to trail construction and maintenance and may require the import of substrate in these areas, which increases the risk of accidental introduction of invasive plant species, or the use of a boardwalk to elevate the trail above the standing water or mucky soils. (See sheet 29 for more information about boardwalk construction).

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

As is typical of Easthampton, most of the soil types in the potential trail corridor are sandy and well drained. However, bands of poorly drained soils, primarily Raynham Silt Loam, appear to overlap with the proposed trail corridor and may present challenges to building a trail in these locations. Though deep and fertile, these soils are classified as very poorly drained and are often found in wetlands.

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

Poorly Drained Soils May Present Challenges for Trail Construction

SOILS

SOILS

The Impact of Trails on Natural Communities The construction and use of a surfaced path in this area has the potential to have an impact on nearby natural communities. This impact could be either negative or positive, or, mostly likely, a mix of both. Planning Trails with Wildlife in Mind, a publication by Colorado State Parks, lists potential ways that trails can help improve the health of ecosystems. Trails “can help: •

restore degraded stream corridors and other habitats in the process of trail building;

•

guide recreational users away from sensitive wildlife habitat and into more adaptable settings;

•

educate people about wildlife issues and appropriate behavior in the outdoors; and

•

build broad constituencies for wildlife conservation by putting people in contact with nature” (PTWM).

However, trails can also have negative impacts such as fragmenting or disturbing habitats, stressing wildlife, and introducing invasive plant species or pollutants like dog waste or trash. Methods for reducing harm from the construction of a trail include: •

routing the trail along existing edges between more disturbed areas and intact habitat, or through previously disturbed areas;

•

avoiding areas of especially high habitat value;

•

adding screening or cover for wildlife in areas where it is lacking;

•

keeping dogs on leash (PTWM).

Trails can also impact plants, primarily through trampling if users leave the trail. Well-designed trails that offer a variety of natural experiences

and are graded properly will reduce the risk of users creating paths off the main trail. In sensitive areas, signs or even barriers can be used to protect plants. Another issue could be the introduction or spread of invasive plants. Management of invasive plants and the planting of native plants when re-vegetation is required can help keep the environment suitable for native wildlife and plant species.

AND WILDLIFE

10

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

Easthampton contains some notable natural features, especially the basalt ridges of Mount Tom and the sand plains that underlay much of the town. Easthampton is also situated over a large portion of the Barnes Aquifer, a valuable resource that provides 1.2 million gallons of water to 60,000 people in four communities (BAPAC). The city is bordered by large stretches of BioMap2 core habitat and critical natural landscape, which indicate areas of high biodiversity or rare species; the Mt. Tom Reservation is the largest local area of this type of landscape. Given the project area’s location between these larger regions of important habitat, and that hydrological systems like streams traverse open spaces and connect to these habitats, there is a possibility that the open spaces here are used as corridors for animals crossing through the city (shown by green arrows on map).

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

Regional Patterns of Connectivity

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton REGIONAL VEGETATION

REGIONAL VEGETATION AND WILDLIFE

Two areas along the proposed path route have notably high levels of invasive plants: the connection between Park Street and the spur to the school, where young Oriental bittersweet forms much of the ground cover, and behind the Park Street solar field, where thickets of multi-flora rose and non-native honeysuckles are nearly impenetrable. The bittersweet, shaded by the mature pine forests in this area, could become a much larger problem if clearing a path route requires tree removal, which would let in more sunlight and lead to increased bittersweet growth. Oriental bittersweet can threaten native species diversity by altering soil chemistry, plant succession, and stand structure (Fryer, 2011). The rose and honeysuckle thickets likely offer valuable cover and forage for local wildlife and given that they do not block the proposed path route, may not need management. However, the risk remains that they will continue to spread and out-compete native plants. The educational opportunities along the potential route are many, given the wide range of natural communities it could pass through. In particular, the succession of abandoned farm fields into forest is an important part of Massachusetts’ history and an increasingly rare ecosystem, which can be seen in various stages along the proposed path. Students and other residents would also be given the chance to appreciate and learn more about the wetlands and streams, which are often undervalued ecosystems.

Wildlife and the Path During two site visits in spring 2020, signs of wildlife observed included extensive deer tracks and scat along the proposed path route. Other tracks were also seen, including opossum and raccoon. Further observations in other seasons may reveal other patterns of wildlife use. The diversity of plant species and types of plant communities likely provides good habitat for birds, small mammals, predators, and deer. Wildlife in the wetlands and vernal pools is especially important to protect, given these species’ vulnerability to human disturbance. FrogWatch, a citizen scientist project, has mapped the calls of native frogs in the wetland located behind the school, showing that a healthy population of spring peepers lives here, as well as other frog species such as wood frogs and American bullfrogs. While the presence of other amphibians is unknown, it is probable that salamanders also breed and live in and near the vernal pools and wetlands.

Given the intensive historical agricultural use and the more recent disturbance from the construction of the solar field where the proposed path would pass, and the absence of any reports of rare species here, a path in this area would have less impact than one in a more intact environment. However, the fact that the path area is adjacent to so much developed space could indicate that this area serves as a refuge for wildlife and the path route should avoid causing further fragmentation. As mentioned previously, trail construction can provide an opportunity to restore degraded ecosystems and can function as wildlife corridors through developed spaces.

11

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

All of the parcels the path would transect were at least partially cleared for agriculture and as recently as 2005 much of the area was still primarily covered with shrubs and early successional trees. The plants in these areas have regrown, forming a patchwork of different plant communities, most comprising a mix of native and non-native species. One major exception to this recent disturbance is the hemlock grove north of the Holly Circle wetland, which has remained uncut, according to aerial maps, at least since 1942. Because of this patchwork of communities, there are many natural edges in or near the potential path corridor; routing the path along such edges may reduce habitat fragmentation and provide a diverse and interesting route for users.

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

Plants and the Path

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

NEIGHBORHOOD VEGETATION AND WILDLIFE

NEIGHBORHOOD VEGETATION AND WILDLIFE

Some of the challenges of this project include the issue of ensuring safe and usable connections to the trailheads from nearby neighborhoods, and traversing the at times difficult natural terrain, which includes steep slopes and wet areas. A further challenge will be designing a path that is both useful to humans and does not harm the wildlife and plant communities in the area. Bringing people, especially young people, into these natural areas in a way that teaches the value of these systems and how to care for them is likely to increase the sense of connection residents have with these systems and landscapes.

Climate Change One of the most important implications of this project could be its potential to mitigate climate change by providing access to the school, a park, and potentially downtown without the use of cars. In addition, given the presence of two solar fields along the proposed route, students could have the opportunity to learn about renewable energy. The potential impacts of climate change on the area are also important to consider. Changes predicted for the Connecticut River watershed include both increased frequency of heavy rain events and increased frequency of drought, which will alter hydrology and the resilience of plants. Summer temperatures are predicted to increase and the variability of spring frost dates and early warming trends will impact wildlife migration patterns and plant flowering times. All of these will put stress on plants and wildlife. The opportunity exists to create an ecosystem in the trail corridor that could create greater resilience in these areas and induce a greater sense of stewardship in trail-users. For example, one positive impact could be the increased ability to manage the existing invasive plants in areas where the trail will pass through.

12

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

Challenges

SUMMARY ANALYSIS

The possible path corridor passes through beautiful natural settings, provides access to diverse habitats and landscapes, which can be interpreted through educational elements, and presents the potential to connect an isolated neighborhood to recreational opportunities, including access to Nonotuck Park, and to create a route for students to commute to school without using fossil fuels.

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

Assets

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

SUMMARY ANALYSIS

Pros: • Gathering spaces are versatile and could also be used as outdoor classrooms. • Takes advantage of views and highlights along the path. • Includes sidewalks and/or bike lanes along Plain Street. Cons: • Steep slopes may constrain trail path near the Park Street wetland. • Crossing the Holly Circle wetland would involve about 400 feet of boardwalk. • Passes through ecologically sensitive areas.

This design uses existing infrastructure to access the school site. Pros: • Avoids all open space and wetland areas. • Least permitting and fewest environmental constraints. • Takes advantage of existing sidewalk along Park Street. Cons: • No opportunity to experience a natural setting. • Likely to be hotter in the summer and noisier for path users. • In order to benefit people to the east, a sidewalk on Plain Street would likely still be necessary.

This design avoids some of the wetland areas while still providing access to Nonotuck Park. Pros: • Avoids Holly Circle wetland. • Less permitting required. • Connects to Nonotuck Park more directly. Cons: • Trails from Nonotuck to the fill site have to cross steep and wet terrain. • May pass through the buffer around a public well. • Has a less natural setting and fewer educational opportunities.

Would the proposed Shared-Use Nature Path benefit you or your child? Would the proposed Park Street Sidepath benefit you or your child? Would the proposed Brook Street Bike Path benefit you or your child?

DESIGN ALTERNATIVES 13

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

This design takes advantage of the open spaces and natural beauty of the proposed route.

lane along Brook Street connecting to a shared-use path through Nonotuck Park and River Valley Way to the White Brook School. Plains residents had the opportunity to review these alternatives and share their feedback in an online survey from June 1 to June 15, 2020 and at a virtual community meeting hosted on June 6, 2020.

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

The following preliminary design alternatives assess the feasibility of a shared-use path through conserved open spaces as originally proposed by the 2019 Emerging Pathways document, and consider two alternative path alignments. The second alternative proposes a separated side path in place of the existing sidewalk on Park Street and Line Street. The third alternative proposes a bike

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

DESIGN ALTERNATIVES

Both the survey and the community meeting presented three design alternatives (see map below). The first followed the original route as proposed in the winter Conway report, through several open space parcels and town easements. The second proposed a side path on existing roads and sidewalks for the entire route. The third proposed a bike lane or sidewalk on a dead-end street and then passed through a portion of Nonotuck park and a town-owned parcel. The responses to these alternatives showed that the original route was the most popular, followed closely by the side path. The combined route was least popular.

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT

Primary Concerns Throughout the survey three topics came up repeatedly as concerns or important issues for residents. These were: safety of path users (especially children), the potential impact on wildlife, and questions regarding path maintenance, particularly in the winter. Another repeated comment was concern about the ability of users, especially those with children, to access the trailhead, due to a lack of sidewalks or other pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure on Plain Street. Examples of comments from the survey that indicate safety concerns: “For travel to and from school it would be nice if there were monitors on the path, just as there are at the crosswalks and intersections. If my child was traveling independently I would like to know that someone else is also keeping a watchful eye.” Examples of comments from the survey regarding impact on natural areas: “Please protect the native vegetation and animals that use the conservation areas for refuge and safety.” Examples of comments from the survey that indicate concerns about accessing the trail: “I walk on Strong St., Plain St., and Hendricks St. every morning and some evenings . . . It is a very vulnerable position to be in as a pedestrian without the slight protection that a sidewalk provides. This is such a wonderful idea and will be great for everyone, especially the children getting to/from school. THANK YOU!!!

Community Support Overall, the community feedback was quite positive. A few of the many supportive comments: “This is an amazing idea and would really enrich the city.” “I think your proposed shared-use nature path is brilliant and very much support its development.” “I live at the end of Holly Circle. This path would be very beneficial for me. I need to drive approximately 5 miles to get to the soccer fields at Nonotuck Park which are probably a half mile from my house.” “We love Easthampton and walk and bike as much as we can! Thank you for your advocacy and vision.” “I love this idea and hope it can be connected to the existing Manhan Trail and the Cottage Street district.” “This would greatly improve the quality of life for me and my family, and encourage us to stay in Easthampton. Right now the busy roads make us consider moving to a more rural setting, this would fix that.” “The more people in different parts of town have easy access to paths and trails without driving, the better!” “LOVE THIS PLAN!!!!”

14

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

The community meeting, held on Saturday, June 6, had 30 attendees. The student team gave a presentation about the project and three preliminary design alternatives, and participants were given the opportunity to respond through several polls as well as typed questions. While the additional engagement with the community was valuable, the results matched the survey well enough that the team decided to continue to use survey responses as the primary marker of community opinion.

Support for a Shared-Use Nature Path:

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

Because many of the residents of the Plains neighborhood had no knowledge of the Emerging Pathways report, the student team aimed to engage this area specifically by first sending out targeting mailers to almost 1600 residents in the Plains and nearby neighborhoods (see map on left). These mailers contained a brief description of the project, a link to an online survey, and the date of an online community meetings. This survey was posted online on June 1 and was available through June 15. At the same time, a description of the project was placed on the Easthampton website, with links to the winter project. In the week before the community meeting on June 6th, the team received almost 140 survey responses. That amount increased to 177 total by June 15. The majority of respondents (83%) heard about the survey through a postcard in the mail, 13.6% heard about the survey through the Easthampton Planning Department Facebook page, and 3.4% heard about the survey from another source.

Left: Routes where survey mailers were sent are shown in blue.

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT

Not for Construction. This document is a student project and not based on a legal survey.

15

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

Universal Accessibility. The Shared-Use Nature Path should be constructed according to Architectural Barriers Act standards of accessibility, so all Easthampton residents and visitors can explore the path comfortably. A small parking lot at the Plain Street trailhead would help non-local or less mobile users access the path.

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

Getting Away from Plain Street Traffic. Residents of the Plains could enjoy a comfortable commute separated from traffic on a two-way side path on the south side of Plain Street within the city right of way. Creating a network of improved pedestrian and bicyclist infrastructure throughout the Plains and Easthampton will reduce dependence on motorized travel and create a more livable city.

Towards a Sustainable Future. Global climate change poses unprecedented challenges for every community on the planet, as well as opportunities for dedicated action to support a high standard of living for all. Easthampton will need to balance the need to conserve natural spaces, develop alternative energy sources, and provide alternative transportation systems in order to chart a course to a livable future.

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

Visiting Easthampton’s Natural Systems. Path users could experience the beauty of two wetland ecosystems up close from the comfort of an elevated boardwalk (Note: Boardwalks should have protective guardrails on both sides). The wetlands of the White Brook area store and clean surface runoff while sequestering atmospheric carbon and providing a rich habitat for local wildlife. Elevated boardwalks allow public passage with minimal impact on these sensitive and valuable natural features.

FINAL DESIGN

FINAL DESIGN - Shared-Use Nature Path

Cross-section showing location of path, buffer, and access road.

Right: Raised crosswalks could traverse both Apple Tree Lane and Plain Street to allow safe access to the trailhead. A 5 foot treelined buffer would separate the path from the solar field access road. A sign directs drivers and path users to the parking lot and information area ahead.

P2

Not for Construction. This document is a student project and not based on a legal survey.

16

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

Left: Measurements of the right-of-way for Plain Street would allow construction of a 10-ft side path with a 5-ft buffer on the south side of the street.

FINAL DESIGN DETAIL Plain Street

P2

e Lane

P1

P1

TREET

PLAIN S

Apple Tre

The city-owned right-of-way is 50 feet wide along the length of Plain Street. The existing roadway at Plain Street is 25 feet wide. The right-of-way extends 5 feet beyond the existing roadway along the north side of Plain Street, and 20 feet along the south side. In this design, a proposed 10-foot-wide shared-use path along the south side of Plain Street would allow people to walk or ride comfortably, separated from traffic by a 5-foot-wide tree-lined buffer. The side path could be constructed entirely within the city-owned right-of-way, though it would cross numerous private driveways along the south side of Plain Street. Some private homeowners may be resistant to the construction of a new side path in front of their houses, but survey responses from residents of the Plains, including many who live on Plain Street, indicate strong support for creating a safe pedestrian and bicycle route along Plain Street.

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

Giustina Conservation Area

The construction of safe and comfortable infrastructure for pedestrians and bicyclists along Plain Street would significantly improve people’s ability to travel without a car in the Plains and to destinations outside of the Plains. A safe route along Plain Street is essential to the overall success of the Shared-Use Nature Path by ensuring that residents of the Plains are able to reach the trailhead at the Giustina Conservation Area.

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

FINAL DESIGN DETAIL Plain Street

P1

Tomaszewki Solar Field

Parking Lot Left and above: The parking lot proposed for the solar field site includes 10 parking spaces, including one accessible space, a kiosk with a trail map and a dog waste station, and two benches under a flowering crabapple. Additional shrubs and trees have been added to screen the view of the solar arrays. Residents of the Plains access the Shared-Use Nature Path at the Giustina Conservation Area on Plain Street across from Apple Tree Lane. A raised crosswalk equipped with button-activated traffic signals provides a safe crossing from the side path on the south side of Plain Street. The Tomaszewki property (west of the Giustina Conservation Area and north of a number of residential lots on the north side of Plain Street) is slated to be developed as a solar array. The developers’ proposed plan includes an access road to the solar site through the southwest portion of the city-owned Giustina Conservation Area across from Apple Tree Lane. Collaboration between the City of Easthampton and the developers of the solar field presents the opportunity to create a trailhead, including an informational kiosk, a bicycle maintenance station, and a small parking lot, without clearing any of the mature white pine forest growing in the Giustina Conservation Area. A 10-foot-wide Shared Use Path could parallel the access road with a separated buffer. If the developers of the solar field are amenable to collaborating with the City, an easement acquired for the path to parallel the planned access road along the eastern border of the Tomaszewki property and cross into the White Brook APR land to the north would result in no significant clearing of forest in the Giustina Conservation Area. If this easement within the Tomaszewski property was acquired, there is a fairly level, roughly 12,000 square-foot space next to the proposed solar array which could accommodate 9 parking spaces (including one universally accessible space) for people who may be interested in driving to the southern end of the nature path.

lk

Crosswa

eet

Plain Str

appearance of the forest, it would also be difficult and expensive due to the steep grade along the western edge of the Conservation Area. The benefits of providing a parking lot would need to be weighed against the additional economic and ecological costs of installing one within the forest. There are currently no formal trails within the Giustina Conservation Area. As part of the effort to increase access to natural areas with the Shared-Use Nature path, a walking trail through the Conservation Area would allow residents to enjoy this currently unused open space.

Acquiring this easement for the path and parking lot is recommended to prevent clearing trees and to take advantage of the level ground in the Tomaszewski lot. Clearing 12,000 square feet of the Giustina Conservation Area for a parking lot would not only dramatically alter the ecological functioning and

Not for Construction. This document is a student project and not based on a legal survey.

17

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

Tomaszewki Solar Field

Woodland Seating Area

FINAL DESIGN DETAIL Plain Street Trailhead

Welcome Kiosk and Benches

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

P1

Walking Trail

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

FINAL DESIGN DETAIL Plain Street Parking

Any management decisions outside of the easement for the path are entirely up to the Chicoine family, provided that they do not detract from the agricultural potential of the land as regulated by the APR. Increased public access to the site on the Nature Path, as well as the planned expansion of nearby residential neighborhoods into the area immediately west of the White Brook APR, could allow for increased public engagement with this historic agricultural site through a community garden or a showcase of restorative agricultural practices such as agroforestry. This design envisions a community garden on the southwest corner of the property, production of chestnuts using restorative agroforestry techniques, and walking trails that could allow people to experience the exceptional views of Mt. Tom around the upper eastern pasture and the historic oak forest in the northeast corner of the property.

Alternative Alignment

Community Garden

Tractor Access Road Chestnut Orchard

Not for Construction. This document is a student project and not based on a legal survey.

18

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

The Shared-Use Path emerges into the open field of the White Brook APR from the Giustina Conservation Area and skirts along the woodland edge to connect to Holly Circle at the northwest corner of the property. The path would attract many Easthampton residents, and connect them to the city’s rich agricultural legacy and future agricultural possibilities.

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

The White Brook APR (Agricultural Preservation Restriction) is one of the few remaining agricultural areas in the White Brook area. The land is owned by the Chicoine family who raise grass-fed beef, pork, and chicken at their farm on Oliver Road in northwest Easthampton. There is currently little agricultural activity on the White Brook APR aside from hay production in the upper pasture on the eastern side of the property. The Chicoines are interested in providing increased public access to the White Brook APR and helping to preserve the rich agricultural traditions of Easthampton. They have granted the City an easement to establish a path from the southern edge of the property to the outlet on Holly Circle in the northeast corner of the property.

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

FINAL DESIGN DETAIL Chicoine APR

FINAL DESIGN DETAIL Chicoine APR

C

A Wetland Passage. The city-owned property immediately north of the private property is

dominated by a large scrub-shrub wetland. As a valuable natural resource that cleans water, reduces flooding, and provides habitat, wetlands are protected under the Wetlands Protection Act and any construction projects must be permitted and approved by the Easthampton Conservation Commission. Elevated boardwalks through wetland ecosystems can allow human access and passage with minimal disruption to local wildlife, vegetation, and hydrology. Here, a 400-ft boardwalk traverses the wetland from Holly Circle to the drier land on the north side of the wetland.

A Quiet Resting Area in a Stately Hemlock Grove. The hundred-year-old hemlock

trees in this grove on the north side of the Holly Circle wetland are some of the most striking natural features in the White Brook area. While much of the surrounding area was cleared of forest for agriculture, this grove has been largely undisturbed, perhaps because the soil is too wet for agriculture or farmers wanted to provide a shady resting place for livestock. This cool and quiet grove provides a peaceful resting area along the Shared-Use Nature Path that doubles as an outdoor classroom.

P1

The boardwalk through the wetland protects the ecosystem while offering beautiful views.

P3

Holl yC wet ircle land

B P1 Holly Circle

A

P2

The hemlock grove provides a cool place to sit or picnic. An outdoor classroom in the hemlock grove offers easy access to the solar field and the wetland in a cool dry location.

Not for Construction. This document is a student project and not based on a legal survey.

19

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

C

immediately north of the White Brook APR is the only portion of the proposed path for which the City doesn’t already have an easement. Initial conversations between the City and the homeowner indicate that the homeowner has significant concerns about ongoing disturbance and loss of privacy associated with a public path, and may have reservations about granting an easement. In this design, the Shared-Use Nature Path exits the White Brook APR at its northwest corner, and briefly aligns with Holly Circle to cross the private property as far from the house as possible to reduce any disturbance to the homeowner.

FINAL DESIGN DETAIL Holly Circle Wetland

B

Crossing a Private Driveway. The private residential lot at the end of Holly Circle

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

A

P2

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

FINAL DESIGN DETAIL Holly Circle Wetland

Fill Mound

C

Alternative Alignment

E

Park Street Solar Site. North of the Holly Circle wetland area, the City has acquired an

B

Southern Connection to Nonotuck Park. The gravel path between two wetlands

C

Mound of Fill. A 250,000 square-yard-mound was created in an area of open space south

D

P1

B

Park Street Solar Field

Above: The existing path to the east of the fill mound is already flat and wide enough to accommodate the shared-use path, and is lined with young poplar trees.

A

Nonotuck Park

A

easement for a path along the eastern edge of a second solar array.

that climbs a relatively steep hill to connect to the southernmost athletic fields in Nonotuck Park could be improved to a 10-foot-wide accessible paved path to connect the Shared-Use Nature Path to the park. The alignment of the original path may need to be adjusted to be accessible (See grading plan below and right). of Treehouse Circle when the City deposited soil dredged from Nashawannuck Pond around 2005. The Shared-Use Nature Path follows the alignment of an existing gravel path that skirts the eastern and northern edges of the mound. Some residents of Treehouse Circle who responded to the survey or attended the virtual community meeting expressed concern that the path would pass close to the houses on the south side of Treehouse Circle and disturb residents. As an alternative, it would be possible to regrade the mound to accommodate an accessible path farther south to minimize disruption to residents.

E

down a hillside among mature white pine trees and cottonwoods and veers west towards Park Street. (See page 27 for more details on the Park Street Branch.)

B

Natural Playground and Picnic Area. The open area between the mound of fill and

River Valley Way boasts a spectacular view of Mt. Tom and is close to both the new White Brook K-8 School and the multi-generational housing at the Treehouse Community. Near the confluence of the main Shared-Use Nature Path and the Park Street Spur is a flat open space suitable for a natural playground and picnic area where path users and neighbors can gather to enjoy the view while young children explore a playground composed of natural features and others venture off to play on the grassy slopes of the mound. (See following sheet for more details.)

Park Street Spur. From the fill site, a branch of the Shared-Use Nature Path winds Not for Construction. This document is a student project and not based on a legal survey.

20

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

D

FINAL DESIGN DETAIL Fill Site

P1

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

Treehouse Community

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

FINAL DESIGN DETAIL - Fill Site

A: A kiosk contains a map of the Shared-Use Path with distances and highlights. Beyond the kiosk, a crushed stone path leads past a bike rack and waste station to the play area.

A B

B: The play area features play structures made from natural materials, encircled by picnic tables that are shaded by five linden trees.

C

C: Beyond the playground, an open area of grass gives children a place to run or play with balls or frisbees. The low grass is enclosed by a meadow, mowed once a year, where native grasses and flowers offer year-round beauty and pollinator and bird habitat.

E

D: While the primary route follows the northern edge of the site, an alternative trail (dashed orange line) crosses the fill mound farther south, providing the houses to the north additional space, but requiring regrading of the mound.

x'

D Below: the flat area here is well suited for a playground and picnic space, while the edge of the mound encloses it to the southeast.

x

x' Not for Construction. This document is a student project and not based on a legal survey.

21

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

x

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

At the entrance to the Shared-Use Nature Path from River Valley Way, three path sections could converge at a shaded picnic and play area. This offers both path users and nearby residents a place to enjoy outside play, eating, and a clear view of Mt. Tom.

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

E

FINAL DESIGN DETAIL Natural Playground

FINAL DESIGN DETAIL Natural Playground

le

al rV

ve

Ri

Treeho u

y

se Circ

ay W

Above: River Valley Way, a quiet residential road, has an existing sidewalk that can be used to provide access through the neighborhood.

le

P1

Not for Construction. This document is a student project and not based on a legal survey.

22

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

P1

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

The Shared-Use Nature Path emerges from the wooded border of the Nonotuck Park Addition and merges with the existing sidewalk on the west side of River Valley Way. After sharing the sidewalk for about 600 feet, the path descends a gentle slope, which does not exceed 5%, onto the grounds of the White Brook K-8 School.

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

FINAL DESIGN DETAIL River Valley Way

FINAL DESIGN DETAIL River Valley Way

Students’ Bike Rack Area. After riding between

C

North Connection. East of the bike rack area, the

the new athletic facilities and parking lot, students using the path would arrive at an area with rows of bike racks where they can store their bikes well away from the hustle and bustle of the school entrance. A sidewalk provides a safe route from the bike rack area to the main entrances.

B

path loops through the play areas at the back of the school along a planned emergency access road, and departs the school grounds into the woods to the north for a connection to the northern part of Nonotuck Park.

A

D

Alternative Alignment Through Williston Athletic Fields. As an

alternative to connecting to Nonotuck Park Road, the city could seek an easement from Williston Academy to construct a shared-use path through Williston Academy’s athletic fields, and connecting to Easthampton High School and the Manhan Rail Trail along Taft Ave and Hisgen Ave. See Future Extensions on Sheet 30 for more details.

Not for Construction. This document is a student project and not based on a legal survey.

23

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

B

Valley Way, the path descends onto the grounds of the White Brook K-8 School. A small gathering area marks the transition to school property and also gives students, school staff, and general path users a place to eat a lunch near the trees.

FINAL DESIGN DETAIL White Brook School

Gathering Area. From the northern end of River

C

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

A

D

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

FINAL DESIGN DETAIL White Brook School

B

Connection to the North. In order to reach an area of moderately sloped stream banks

C

Wetland Crossing. The path descends a moderately sloped stream bank and crosses

C

B

suitable for an accessible stream crossing, the Shared-Use Nature Path would travel along the western bank of White Brook, skirting through the corner of a property northwest of Nonotuck Parked owned by Williston Academy, a private school. Extending the Shared-Use Nature Path to create this northern connection to Nonotuck Park would require the City to obtain an easement from Williston Academy.

White Brook on a 100-foot-long boardwalk before ascending the opposite bank and merging with Nonotuck Park Road near the entrance to Nonotuck Park. See Section X below for a cross-section of the more accessible stream crossing.

A

x'

C

y' x

y

x

x'

Above: Cross-section of the proposed wetland crossing north of the school. Below: Typical cross-section of existing stream crossings behind the school.

y

y' Not for Construction. This document is a student project and not based on a legal survey.

24

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

Nonotuck Park Connection North

trails behind the Middle School to cross White Brook on makeshift wooden bridges and connect to Nonotuck Park. These trails traverse the steep stream banks and muddy wetland soils around White Brook. The steep slopes and muddy terrain are challenging to navigate, and inaccessible to many users. In addition, heavy use of these trails is damaging sensitive vegetation and eroding the stream banks. In this design, pedestrian and bicycle traffic between the White Brook School and Nonotuck Park is redirected to a single universallyaccessible stream crossing, and the degraded stream banks behind the school have been restored and stabilized with native wetland plants. See Section Y below for a typical crosssection of the steep stream crossings behind White Brook School.

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

Restoration of Eroding Stream Banks. People currently use a network of informal

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

A

FINAL DESIGN DETAIL

FINAL DESIGN DETAIL Nonotuck Park Connection North

Switchbacks. The path winds down the slope in gradual switchbacks before straightening out as

B

Retaining walls. Retaining walls are built to hold a raised pathway at an accessible grade

it enters the forest.

above the existing grade. Path would be raised as much as 4 feet above existing grade. See section below.

Above: Gentle switchbacks wind down the slope. Above: Cross-section of proposed retaining wall (shown in red with new grade)

Below: In an example of how the switchback alternative could look, the path winds through an open area before entering the forest.

Below: A retaining wall allows for a shorter straight trail section.

B

Not for Construction. This document is a student project and not based on a legal survey.

25

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

A

FINAL DESIGN - DETAIL

The section of the Park Street parcel that connects to the road is both narrow and steep. This presents some challenges in ensuring that the path access here is accessible. Two potential methods for creating an accessible trailhead are shown here. Both require extensive regrading.

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

A

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

FINAL DESIGN DETAIL Park Street Trailhead

ok

e Bro

ch

ok W est B

ran

ranc

st B

h

Ea

The path ascends a moderately steep hill among cottonwoods and pines to emerge in the open area west of the mound of fill. Path users are rewarded for their effort with a spectacular view of Mt. Tom directly ahead to the east. This hillside would require some significant regrading to meet acceptable grades for an accessible path.

P1

P2

Left: The wetland crossing over the west branch of White Brook.

P2

Right: This forest was once an agricultural field, and is now a beautiful open woodland.

Not for Construction. This document is a student project and not based on a legal survey.

26

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

P1

A climb to a view.

B

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

A

Bro

B

B

ite Wh

steep slope adjacent to Park Street, the path descends a more gradual slope and winds northeast to cross the east branch of White Brook where the banks are more gently sloped. A 60-ft boardwalk crosses the wetland.

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

Park Street wetland boardwalk. After the

Whit

A

FINAL DESIGN - DETAIL

FINAL DESIGN DETAIL Park Street Spur

How the Project meets the Criteria While this trail as proposed does not connect to existing infrastructure or to downtown, it does connect a currently disconnected neighborhood with the school and a large city park, and could be extended in the future to provide further connections with downtown and the Manhan Rail Trail.

Equitable: Serve the diversity of Massachusetts residents.

Providing connections for youth to schools is one of the primary ways to provide equitable access.

Efficient: Allow for efficient use of grant funds. Ready: Are ready for the proposed phase.

Key factors of readiness include community engagement, permitting and access challenges identified and explored, and a maintenance plan in place. This report addresses the first two of those factors and offers recommendations for management.

Safe: Effectively incorporate safety.

Discussion of how to ensure the safety of path users is featured this report.

Accessible: Adequately address accessibility.

One of the primary goals of the City is for this path to be fully ADA compliant. Adding educational elements to the trail and siting the trail through a variety of natural settings are both integrated into this project.

Experiential: Create diverse, high quality recreational experiences and connect users to the natural and cultural wealth of Massachusetts.

Primary Criteria

Above: the green circle indicates a 2-mile radius from the current White Brook Middle School and the new PK-8 school site. The possible path is well within this radius.

•

Projects must be within a 2-mile radius of a school with students between kindergarten and 8th grades (see image to left).

•

Projects must be ADA compliant.

•

Schools must partner with the SRTS program’s non-infrastructure program and take on education, encouragement, enforcement, and evaluation activities to support the active transportation infrastructure.

The first two of these criteria are already met in the project design as proposed. The third criterion could be met with further support and planning on the part of the City and the school.

Criteria that increase application score, and are met or are able to be met in this project: • • • • • • • • •

Title I school Serves more than 300 students No plans to close or move school More than 5% of students live within 2 miles of the school Preliminary assessment/study/plan conducted Existing issues and proposed solutions have been identified The community supports the project Design plans and cost estimate have been prepared Connection to other infrastructure projects such as existing trails.

27

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

Both of these programs have criteria that need to be met by a project in order to qualify. The following tables demonstrate which criteria are already met or have the potential to be met by the proposed multi-use path connecting the Plains neighborhood to Park Street and White Brook School.

Primary Criteria Connect: Plan, Design or Construct off-road shareduse pathway and recreational trail connections between where Massachusetts residents live, learn, work, shop, and recreate.

FUNDING SOURCES

Two grants that may be appropriate for creating a path in Easthampton are offered by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. MassTrails grants focus on creating greater connectivity between existing path networks and increasing access to under served populations. The Safe Routes to School program aims to expand the opportunities for students to walk or bike to schools.

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

Grant Funding for Paths

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

FUNDING SOURCES

In 2001 the City of Woodinville developed a master plan for a city park that contained several wetlands and a creek used by endangered salmon. Part of the design was a trail system that included 1,470 feet of trail within the wetland buffers, with viewing platforms. This was intended to be used as both a recreational trail and an outdoor classroom. After much research, the city decided to use recycled plastic lumber instead of treated lumber, to reduce harmful impacts to the wetlands and stream. This lumber is 100% recycled and reinforced with fiberglass rebar, making it stronger than wood. This allowed the joists to span greater lengths than traditional wood, which reduced the cost of installation, and will last longer than wood, further reducing overall costs. The boardwalk itself was installed with the help of volunteers, and was completed in 2008. The local Rotary Club promised to manage and maintain the park and trail system.

For further information: www.gazettenet.com/Archives/2014/07/ trailswork-hg-073014 www.kestreltrust.org/places/fort-river-trail

Case Study: Pheasant Branch Creek Corridor Trail, Middleton, Wisconsin What: A project to improve an existing 1.2-mile community trail system that connects two major roads as well as two schools. Why: The existing crushed rock surface suffered from flooding, erosion, washouts, steep grades, blind corners, and three stream crossings that made it impassable in the winter. How: The trail was regraded and widened to 10’ with a 4’ crushed limestone shoulder, and the entire trail surface was paved with porous asphalt. Benefits reported by the city: • •

The trail used recycled materials, which were sourced locally. Faster snow and ice melting and less winter maintenance was required.

•

Protection of wetlands and soil health, both by slowing runoff and by filtering pollutants. • Competitive price: while the porous asphalt cost $10-15 more per ton than regular asphalt, the porous material spread 10-12% farther, making the overall difference in price negligible. • Easier to maintain: the reduction in snow removal and winter maintenance costs amounted to $3,500 per year compared to regular asphalt trails. The trail is cleaned twice a year with blowers or sweepers to remove leaves and dirt. • Less cracking. After two years of daily use and cold winters, the trail had no cracks and still looked brand new. • Trail users have given positive feedback, enjoying both the fully accessible firm and stable surface and the 20% reduction in density compared to regular asphalt, leading to less stress on runners’ joints. For further information: www.americantrails.org/ resources/porous-asphalt-shows-advantages-fortrail-surfacing

For further information: www.americantrails.org/resources/atale-of-a-trail-boardwalks-for-woodinville

Boardwalk with Helical Piles Of the alternative footing options available for boardwalks, helical piles make the most sense in terms of low environmental impact. Because they are narrow metal rods, screwed directly into the ground, they disturb a minimal amount of ground and do not impact wildlife. They also don’t require grout or other potentially polluting additives, and are quick to install. They are stable even in soft soils and can be installed in areas with limited maneuvering space. The boardwalk itself should be elevated high enough to ensure adequate sunlight reaches the vegetation beneath. The gaps between the planks should not exceed 1/2 inch. Narrower boards will leave more gaps, which increases the amount of sunlight that shines through. For more information about helical piles: contecompany.com/wetland-boardwalkconstruction-in-a-fragile-eco-system

Not for Construction. This document is a student project and not based on a legal survey.

28

Galen Hammitt | Walker Powell | The Conway School

This trail, located in Hadley, MA, is a fully accessible 1.2-mile trail that passes through a variety of natural systems including forest, grasslands, and river lands. The main part of the trail is surfaced with crushed stone, but extensive portions of the trail cross through wetlands via boardwalks. This trail was built with the aid of a youth conservation corps, providing valuable education and volunteer opportunities for local teens. The process of building the trail took four summers and was completed in the fall of 2014. Now, six years later, the trail is a favorite with locals for birdwatching and wildlife sitings, and a place for children, the elderly, and the mobility-impaired to experience a beautiful natural trail.

MATERIALS AND PRECEDENTS

An alternative to conventional asphalt, porous asphalt shows great promise as a surface for multi-use paths. The combination of increased drainage ability with a firm and stable surface means that porous asphalt is both more environmentally friendly and still suitable for ADA paths. A study done by the USGS in 2018 showed that porous asphalt may help filter pollutants and sediments out of stormwater (Selbig, 52). In addition, porous asphalt retains heat longer in the winter than conventional asphalt; this, combined with the ability of water to flow into the surface, means that porous asphalt is likely to require less ice and snow removal (51).

Alternative Materials: Woodinville, WA

Prepared for the City of Easthampton | Spring 2020

Porous Asphalt

The Fort River Trail

PLAINS TO SCHOOL: A Shared-Use Path for Easthampton

MATERIALS AND PRECEDENTS

Next Steps to Ensure the Success of the SharedUse Nature Path

C

Complete Streets Prioritization Plan. 2017. Vanasse Hangen Brustlin, Inc. easthamptonma.gov/government/forms-documents/planning/plans-anddocuments/1377-complete-streets-prioritization-plan-narrative/file.html

This report represents a beginning for a path that will provide residents of Easthampton many benefits. A few topics remain to be considered in more depth to ensure that the proposed path fully meets the needs of its future users. In particular, questions of safety and future management have not yet been addressed in this report.

Fort River Trail at the Conte Refuge. Kestrel Land Trust. www.kestreltrust.org/ places/fort-river-trail

D