R a r e B o o k s L t d

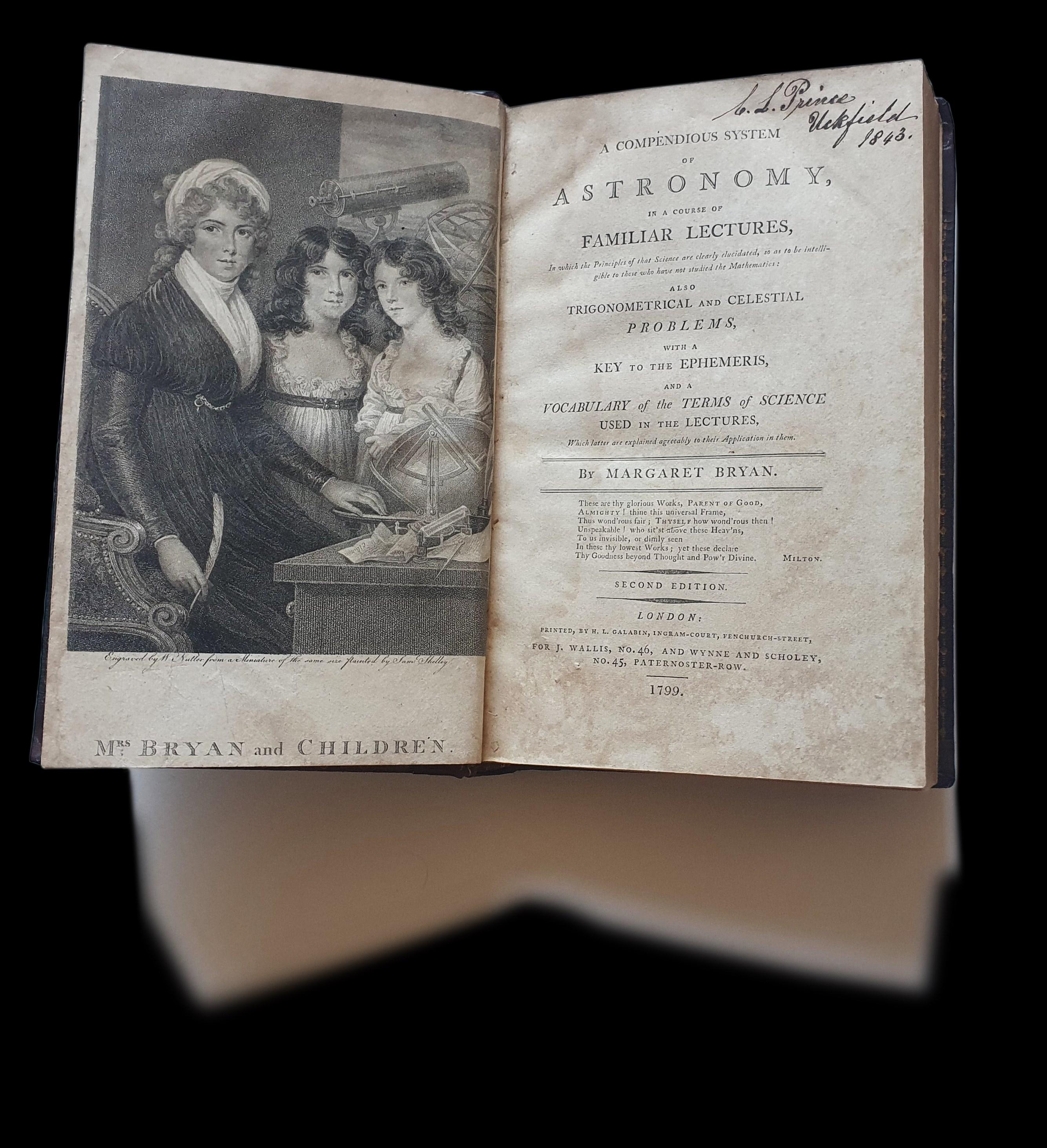

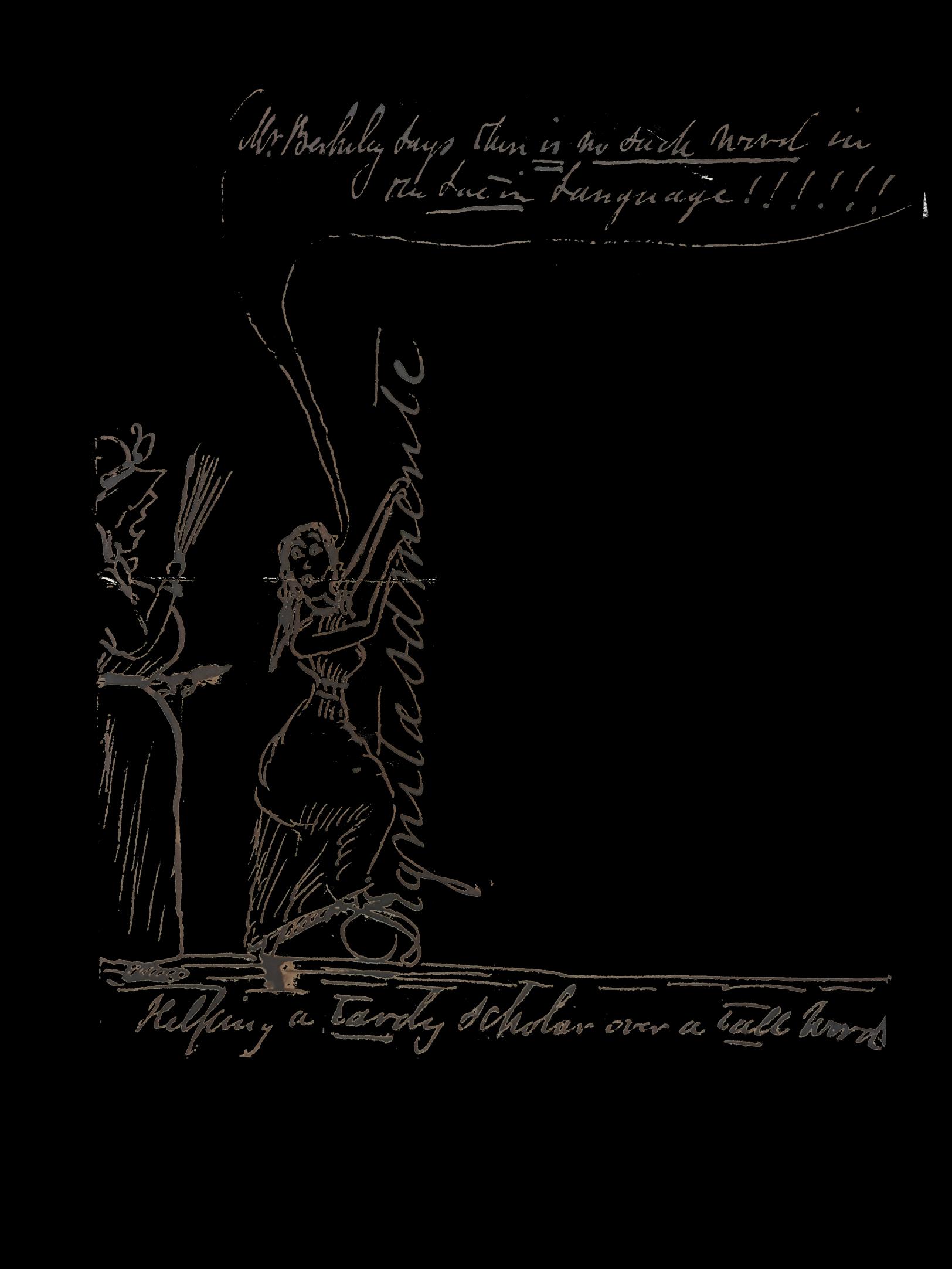

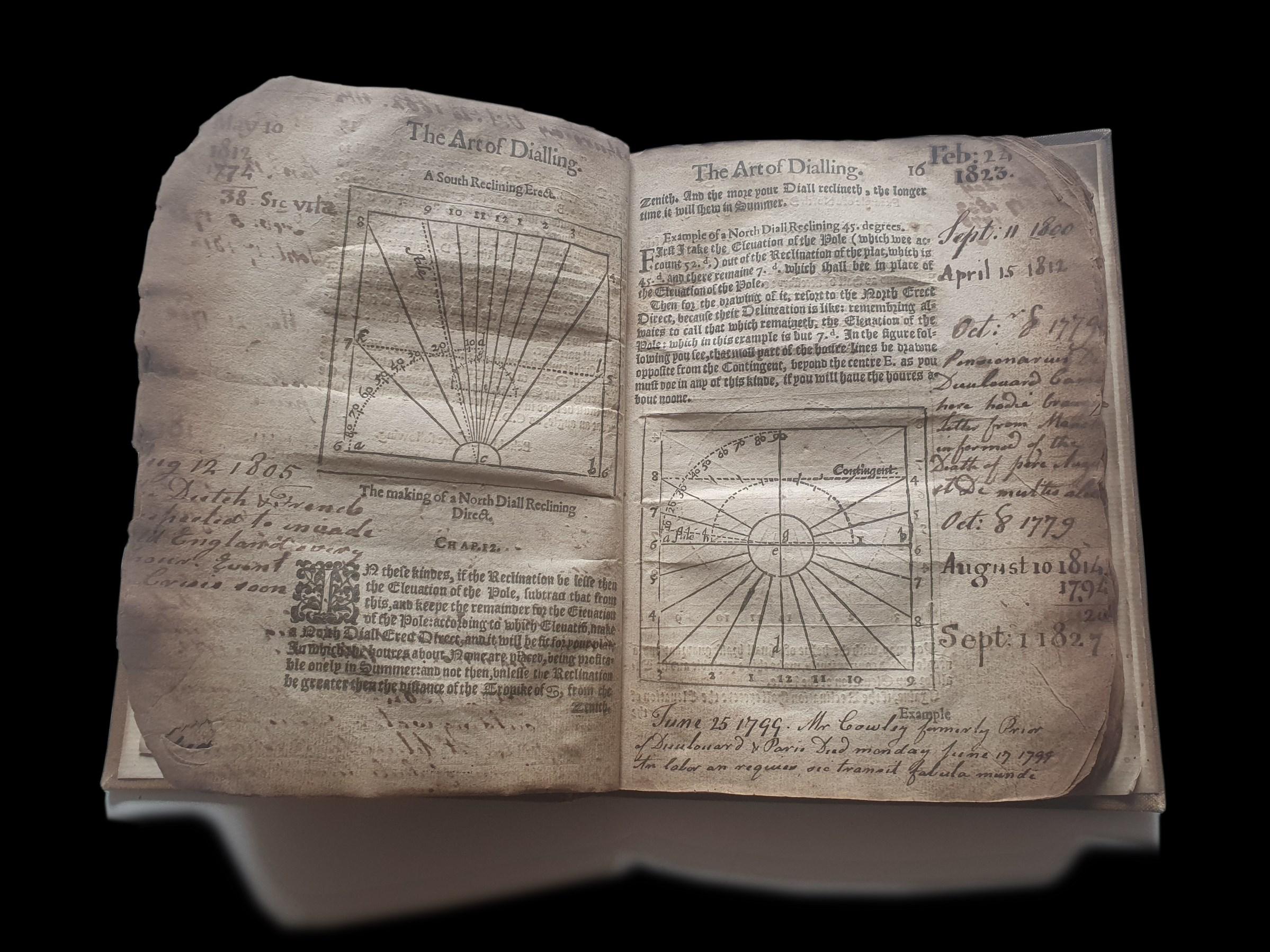

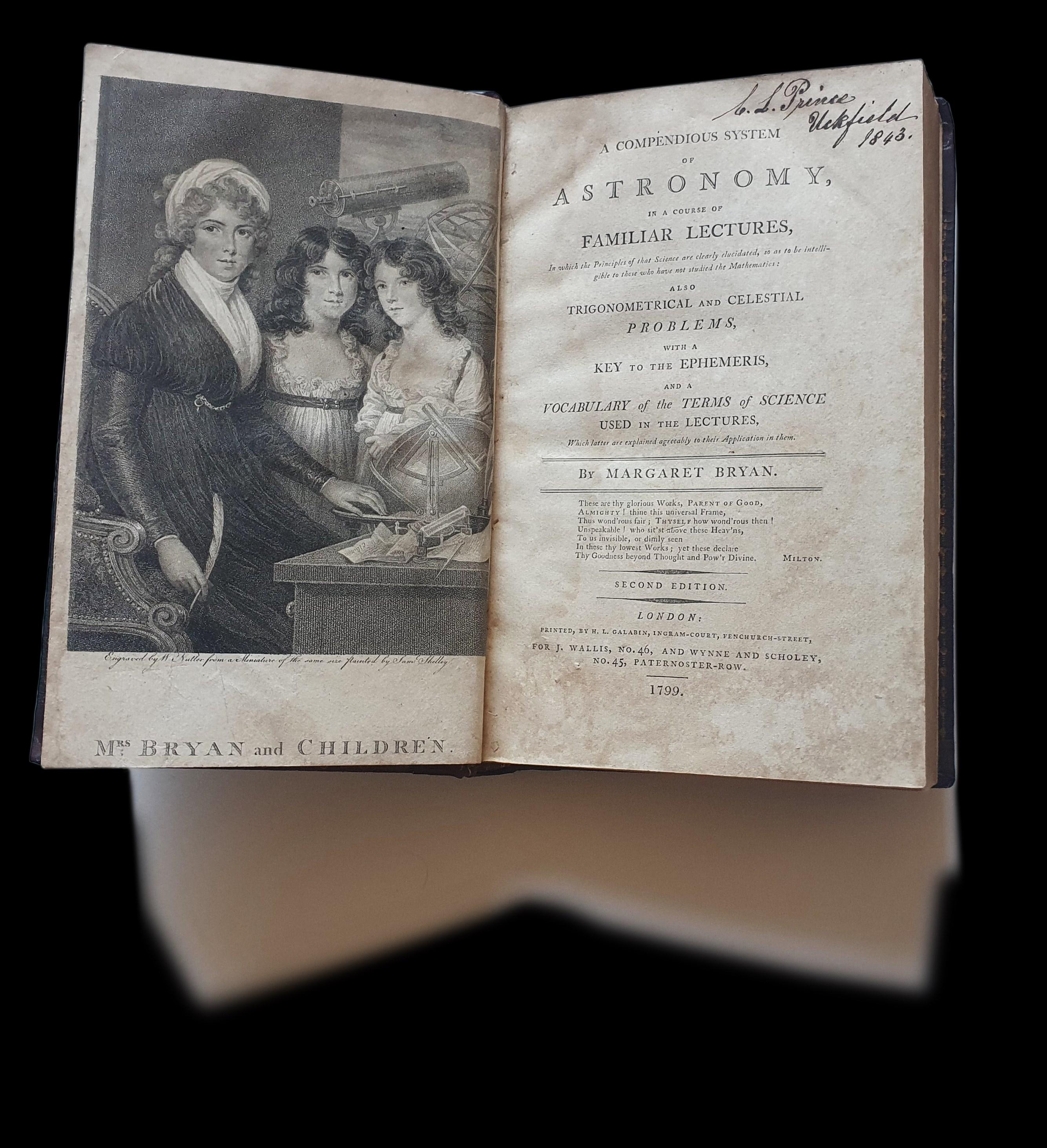

BRYAN, Margaret A compendious system of astronomy, in a course of familiar lectures, In which the Principles of that Science are clearly elucidated, so as to be intelligible to those who have not studied the Mathematics: also trigonometrical and celestial problems, with a key to the ephemeris, and a vocabulary of the terms of science Used In The Lectures, Which latter are explained agreeably to their Application in them. By Margaret Bryan.

London: printed, by H.L. Galabin, Ingram-Court, Fenchurch-Street, for J. Wallis, NO. 46, and Wynne and Scholey, NO. 45, Paternoster-Row, 1799. Second edition.

Octavo. Pagination xxxviii, [2], 415,[1] 17 engraved plates, of which 3 folding. Contemporary mottled calf, gilt, rebacked, red morocco label, corners restored, text and plates foxed and water-stained, some pencil markings to margins.

Provenance: engraved armorial bookplate to pastedown and inscription to title page (“C. L. Prince / Uckfield / 1843”) of Charles Leeson Prince (1821-1899). He had a medical practice at Uckfield, but retired in 1872 to create an observatory and pursue his interest in astronomy and meteorology. He was an early pioneer of photography, kept meteorological observations and published several works on astronomy and had a fine library. He was a Fellow of the Royal Meteorological and Astronomical Societies.

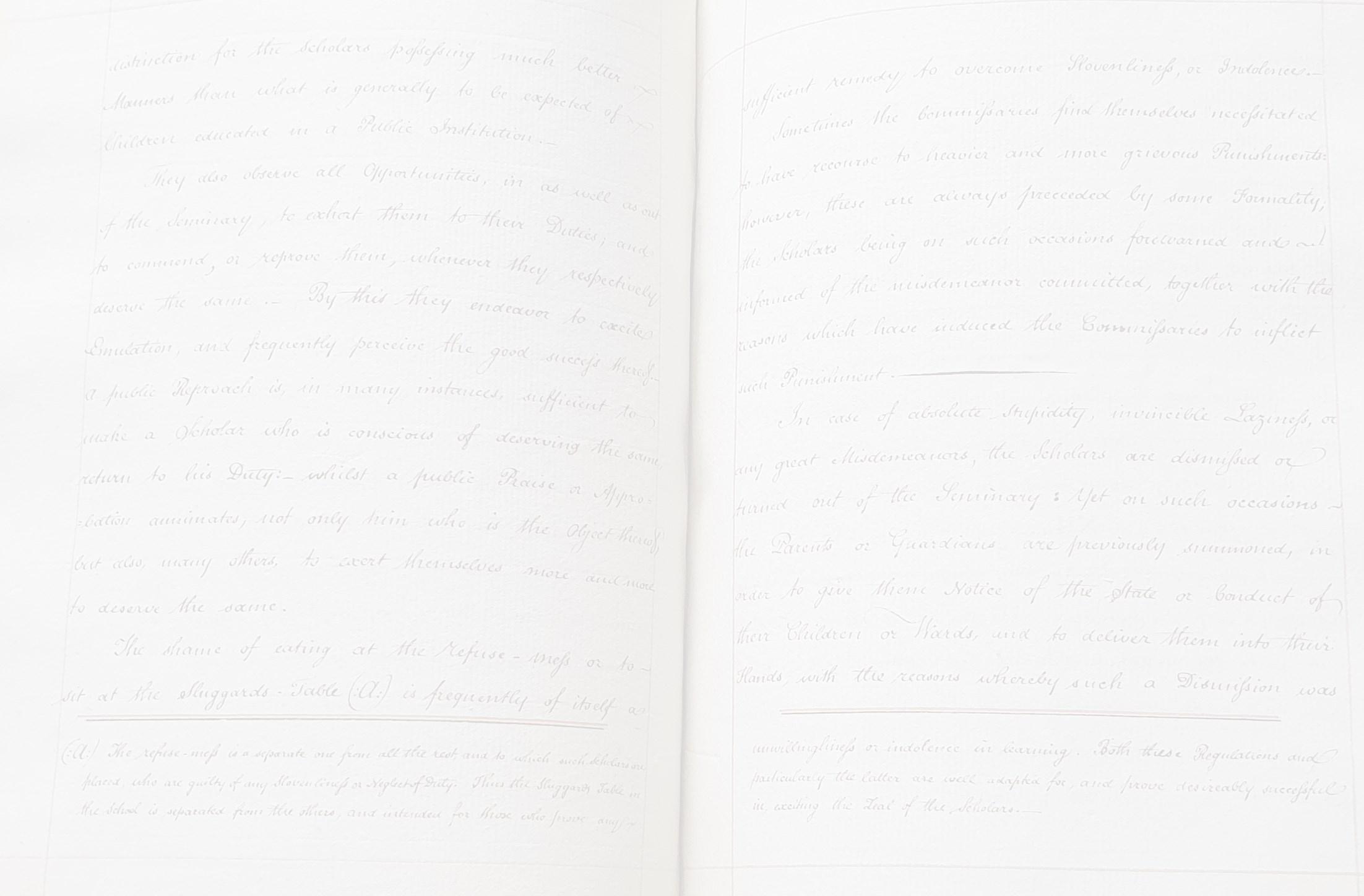

¶ Margaret Bryan suffered the fate of so many women, not just of her era but throughout most of history: in the words of ODNB, “Little is known about her life” – this despite her running several schools in London and Margate at the turn of the 18th century. That they were schools for girls may partly explain the obscurity surrounding her biography. But, as ODNB also records, she was “a noted early example of a woman teaching natural science to other women”.

This is the second edition of Bryan’s first book, A Compendious System of Astronomy, based on her lecture notes and first published in 1797. In her preface, she is at pains to disclaim any originality and expresses the hope that “those whose extensive learning and liberality lead them to judge impartially” will prove themselves superior to “the false and vulgar prejudices of many, who suppose these subjects too sublime for female introspection, (ascribing to mental powers the feebleness which characterizes the constitution)” and will bestow “their avowed patronage” upon Bryan’s sincere efforts, “acknowledging truth, although enfeebled by female attire”. The preface ends with an endorsement from one such learned liberal, the mathematician and educator Charles Hutton.

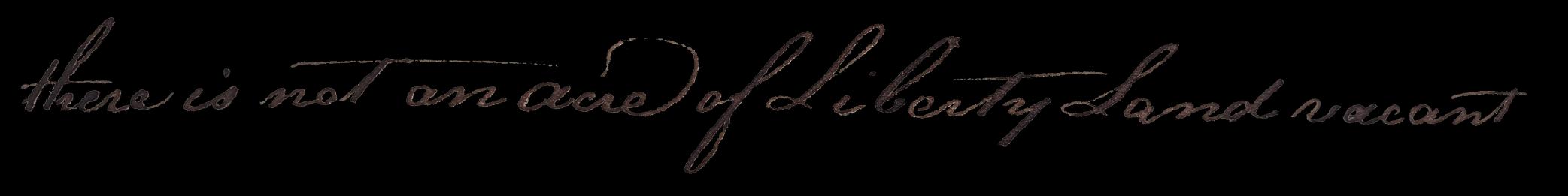

The book’s engraved frontispiece is another piece of careful positioning on Bryan’s part: she is pictured sitting among her instruments, holding the viewer’s gaze, as does one of her two daughters standing next to her. The twin spheres in which Bryan moves – the domestic and the scientific – are thus combined. Her trajectory may have left few biographical traces, but this portrait symbolises her trailblazing contribution to the scientific education of women.

£1,650 Ref: 8147

ONE

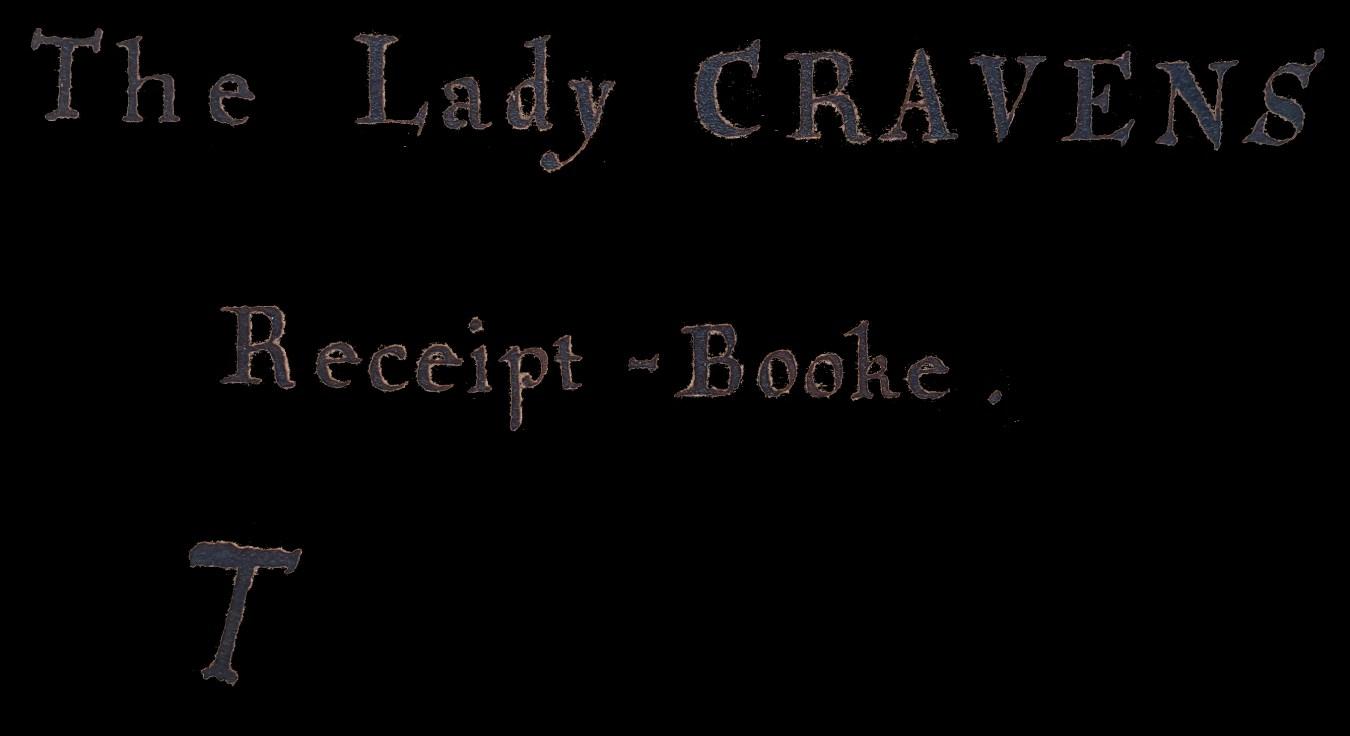

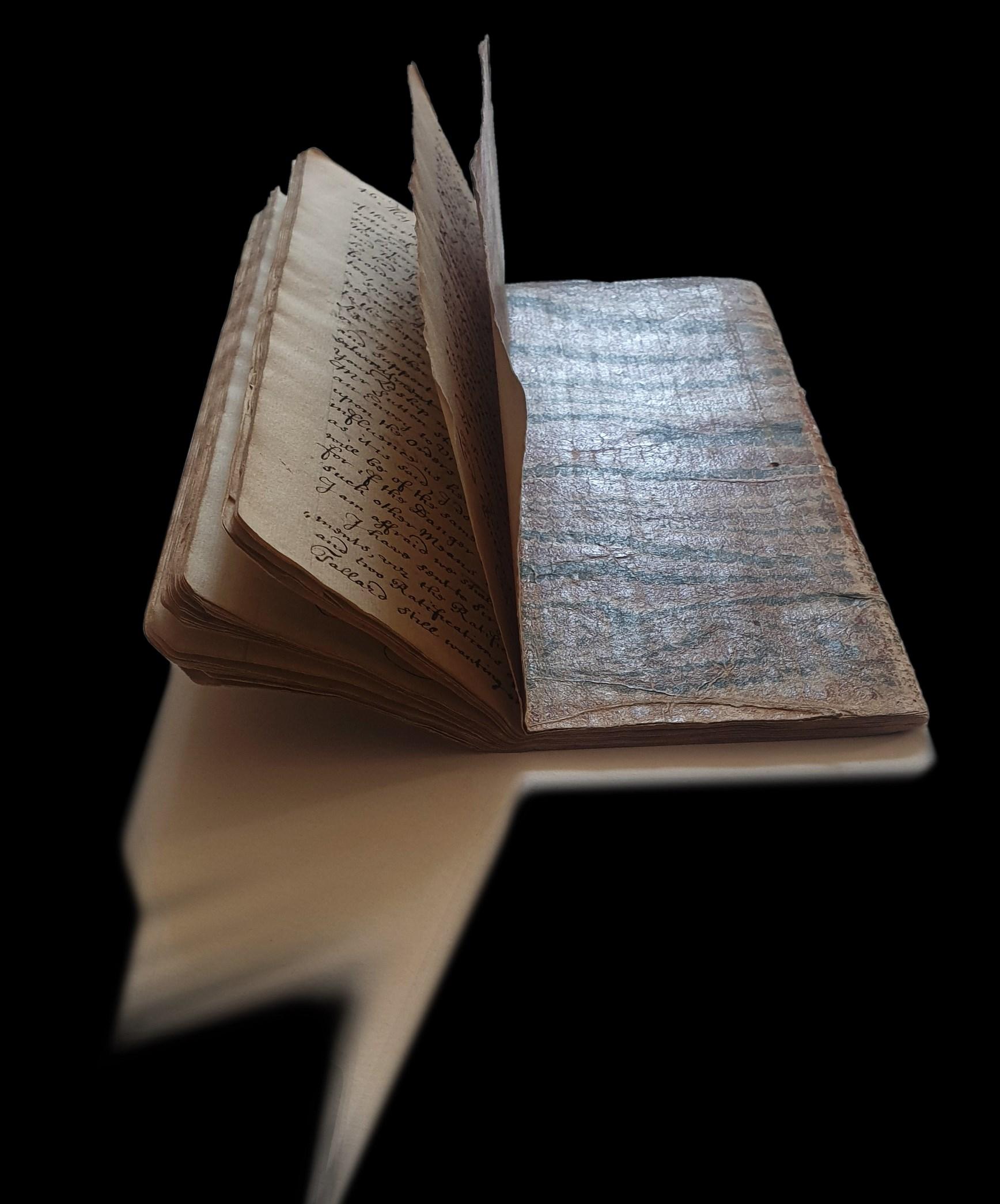

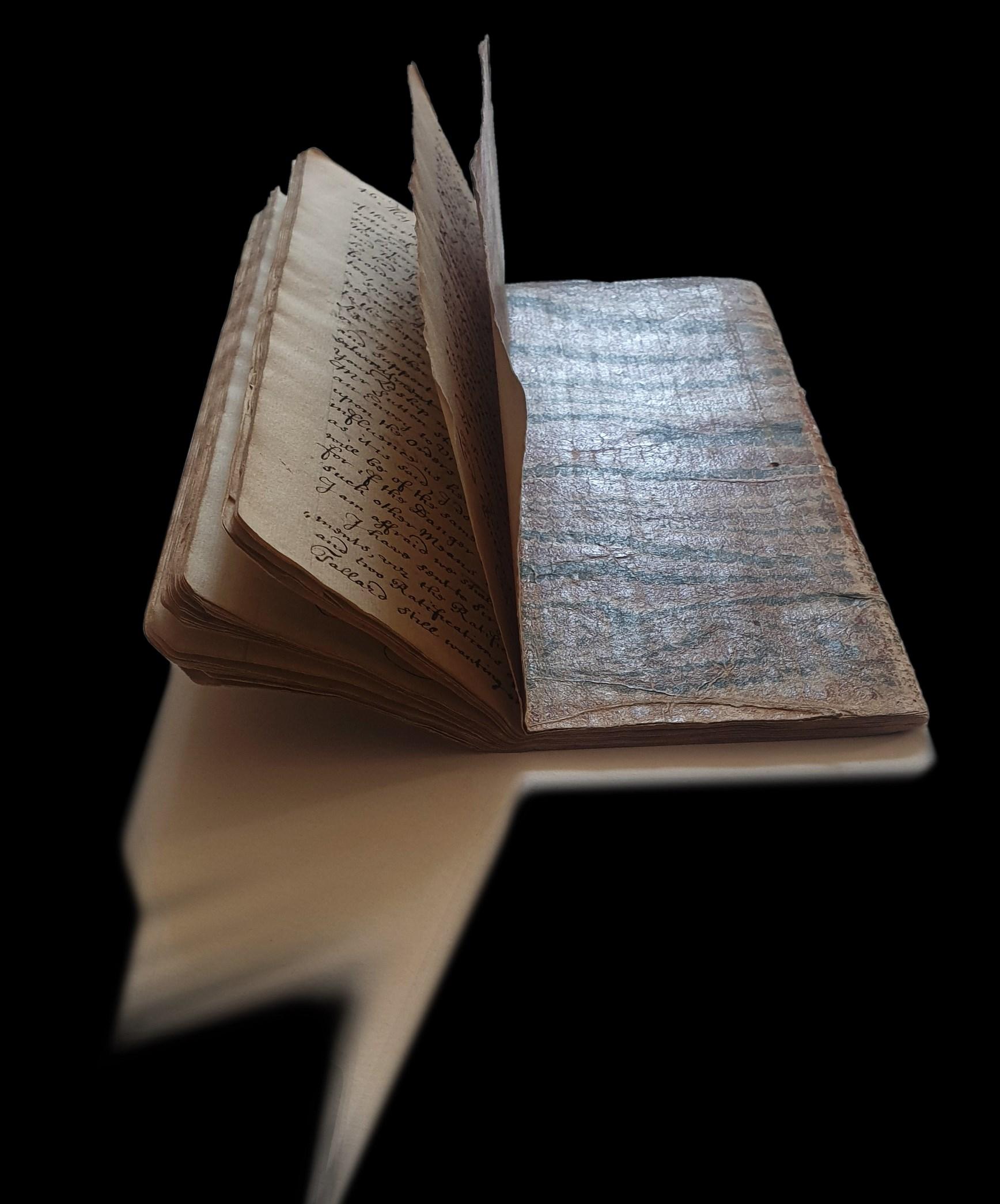

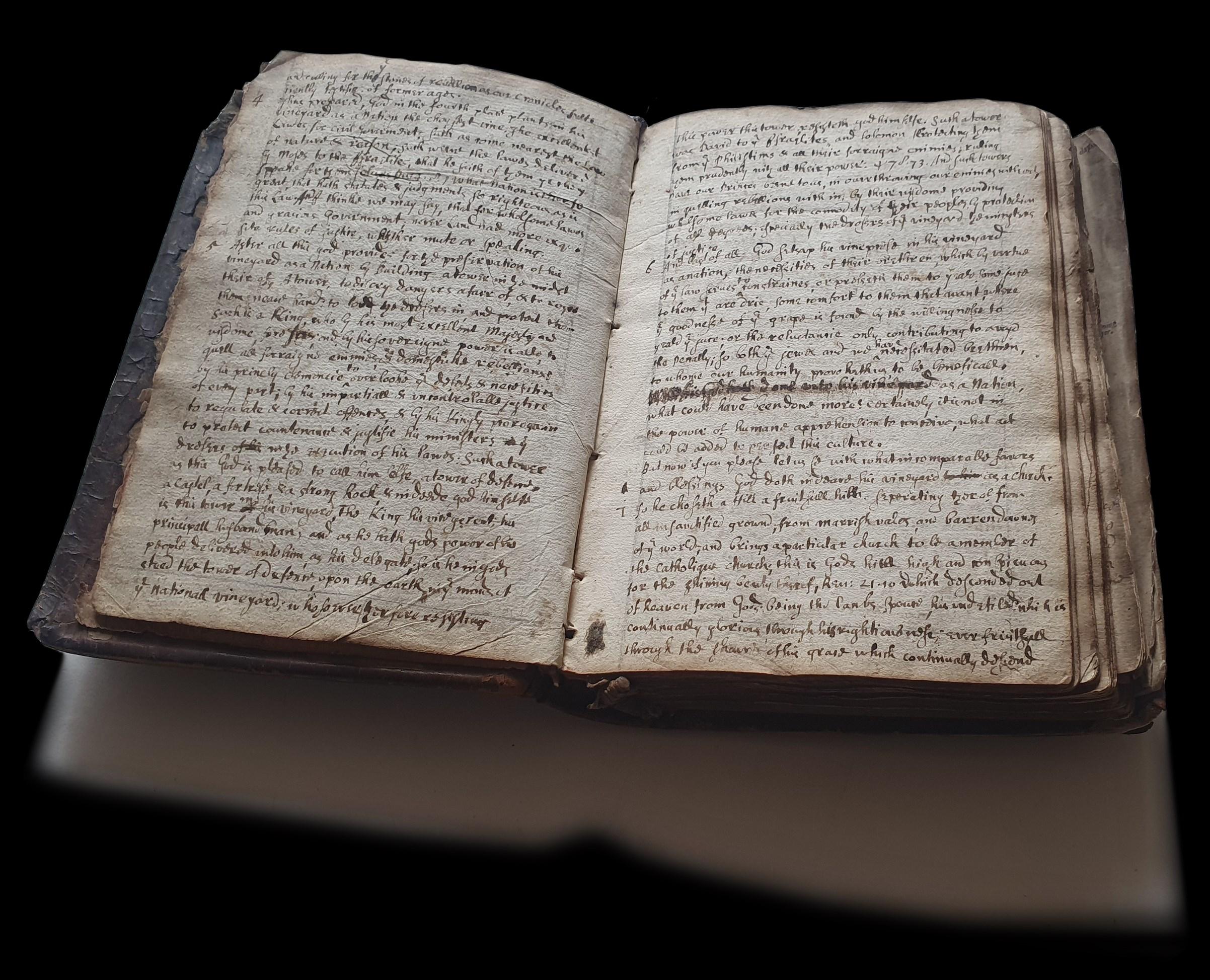

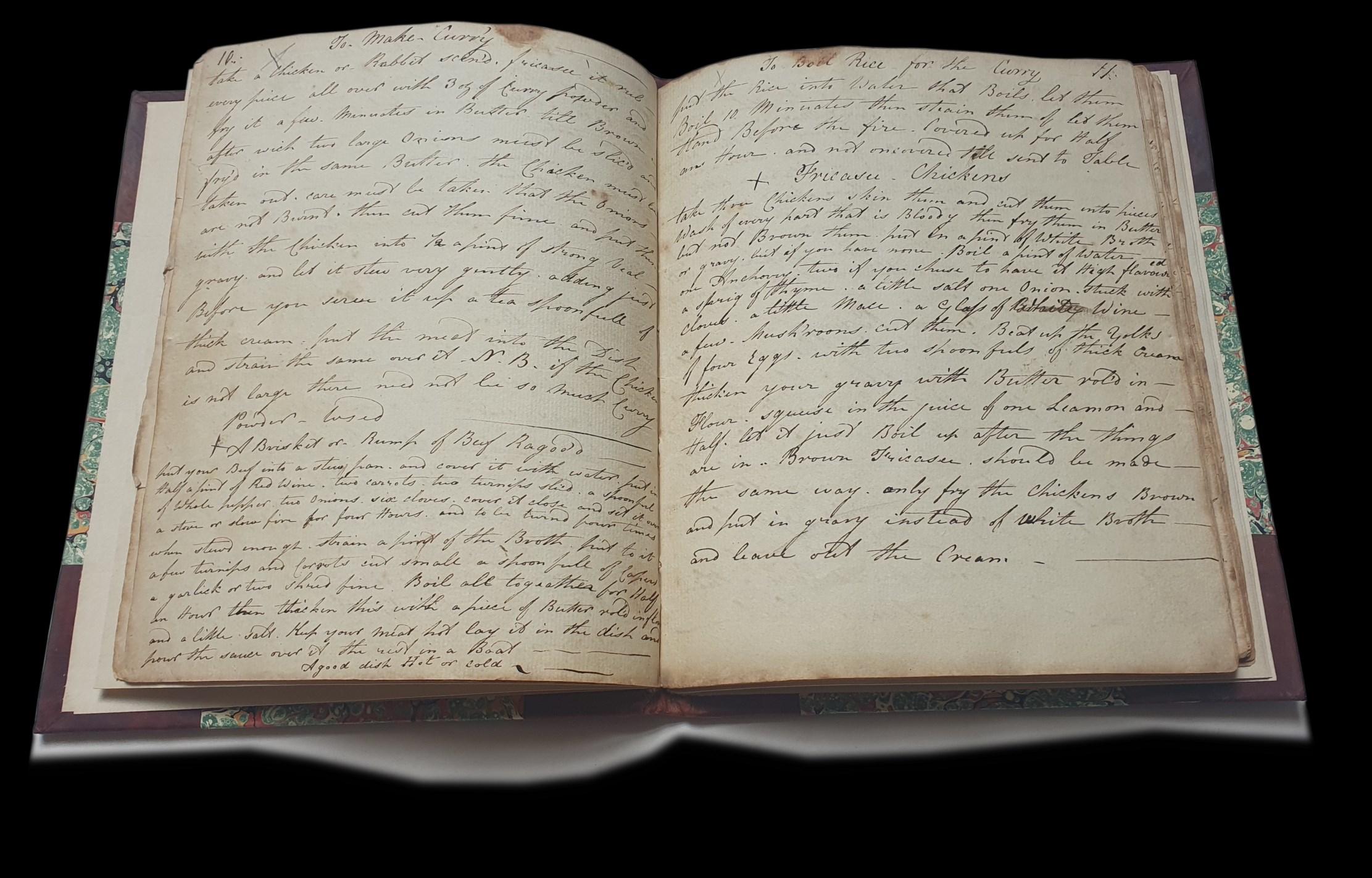

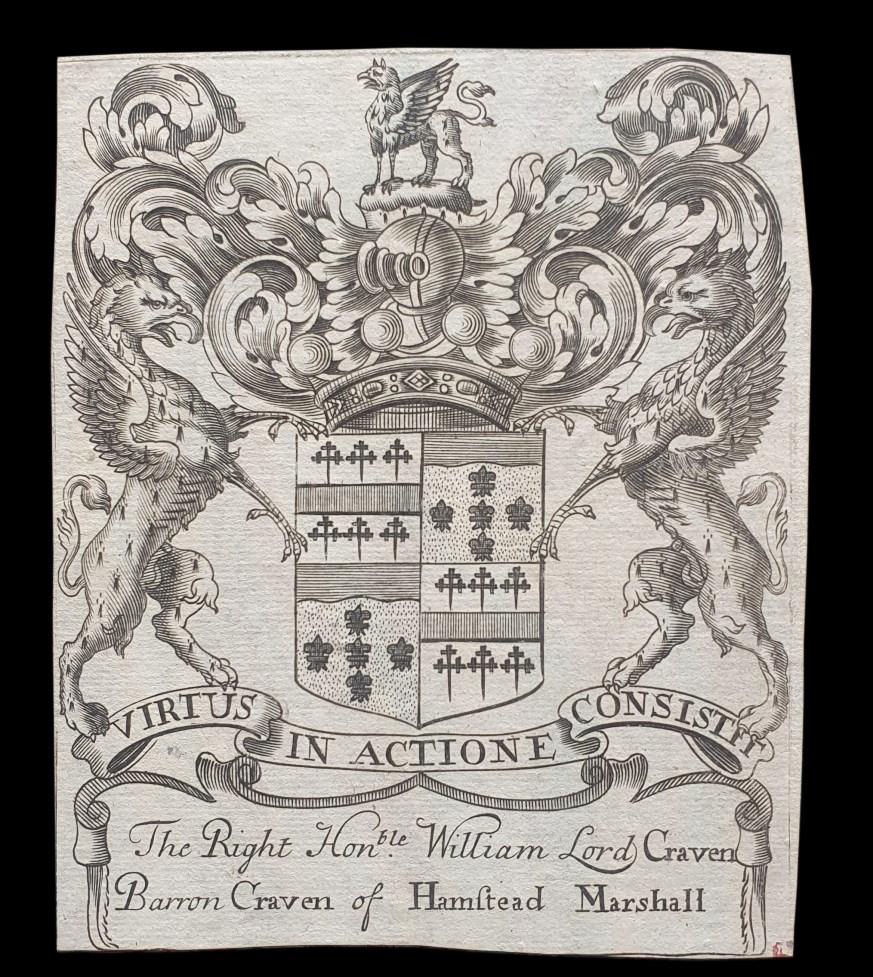

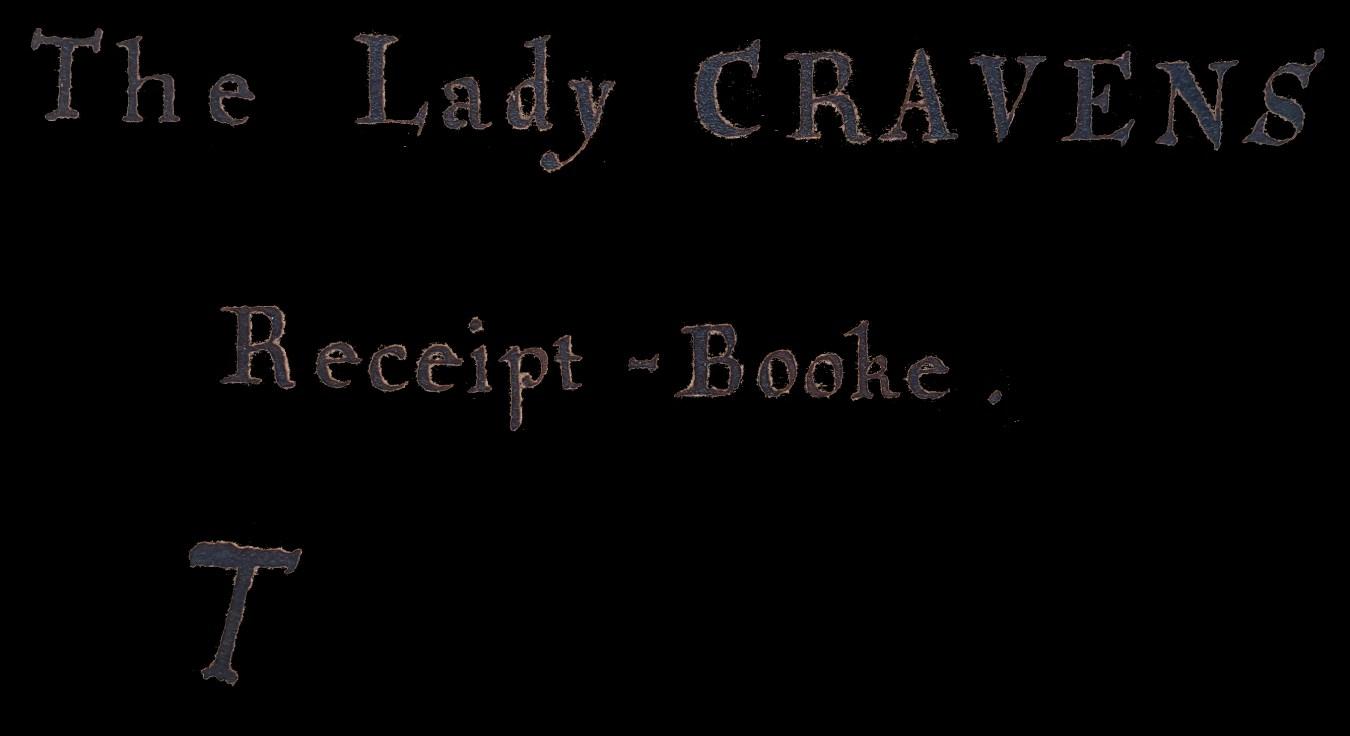

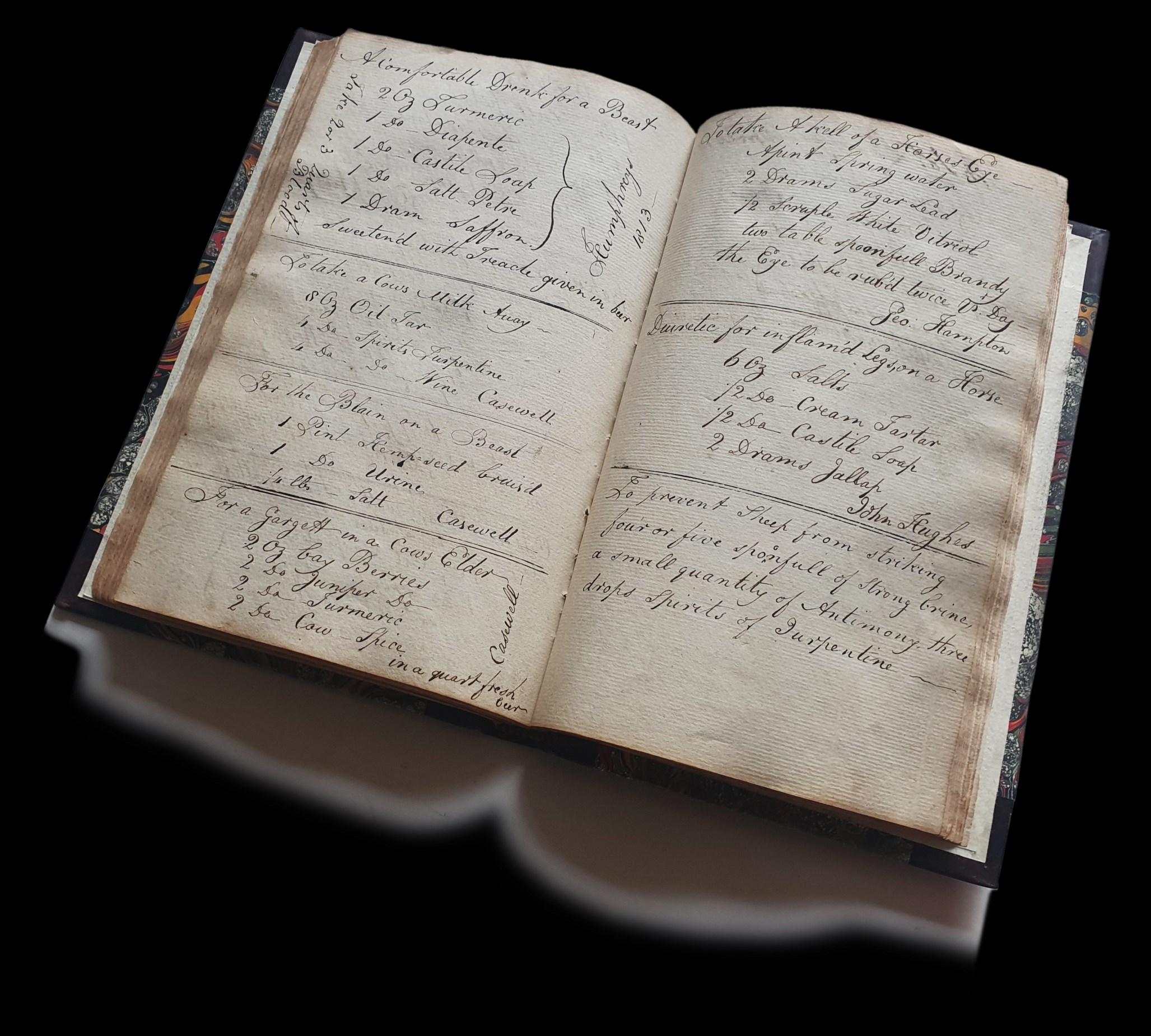

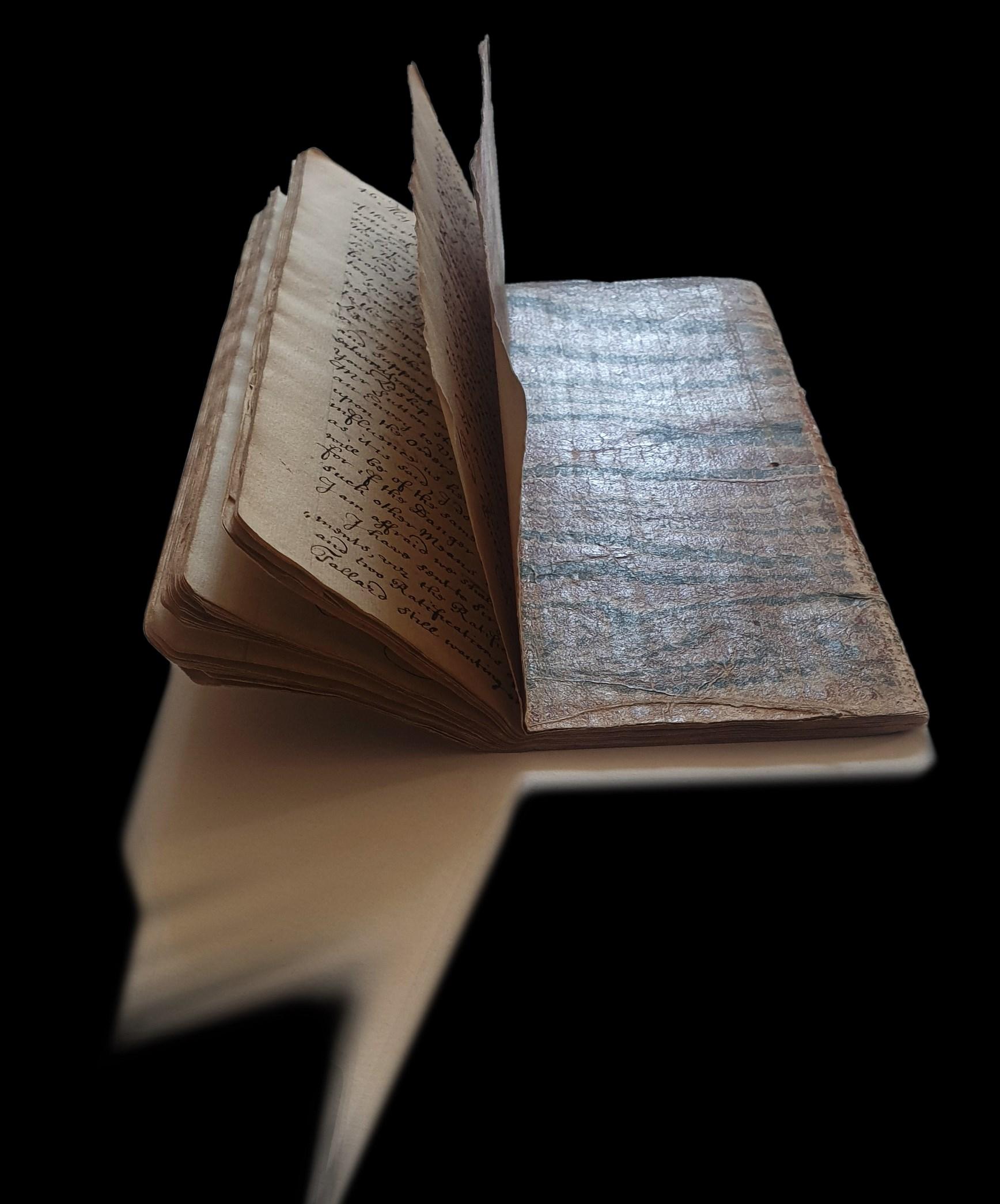

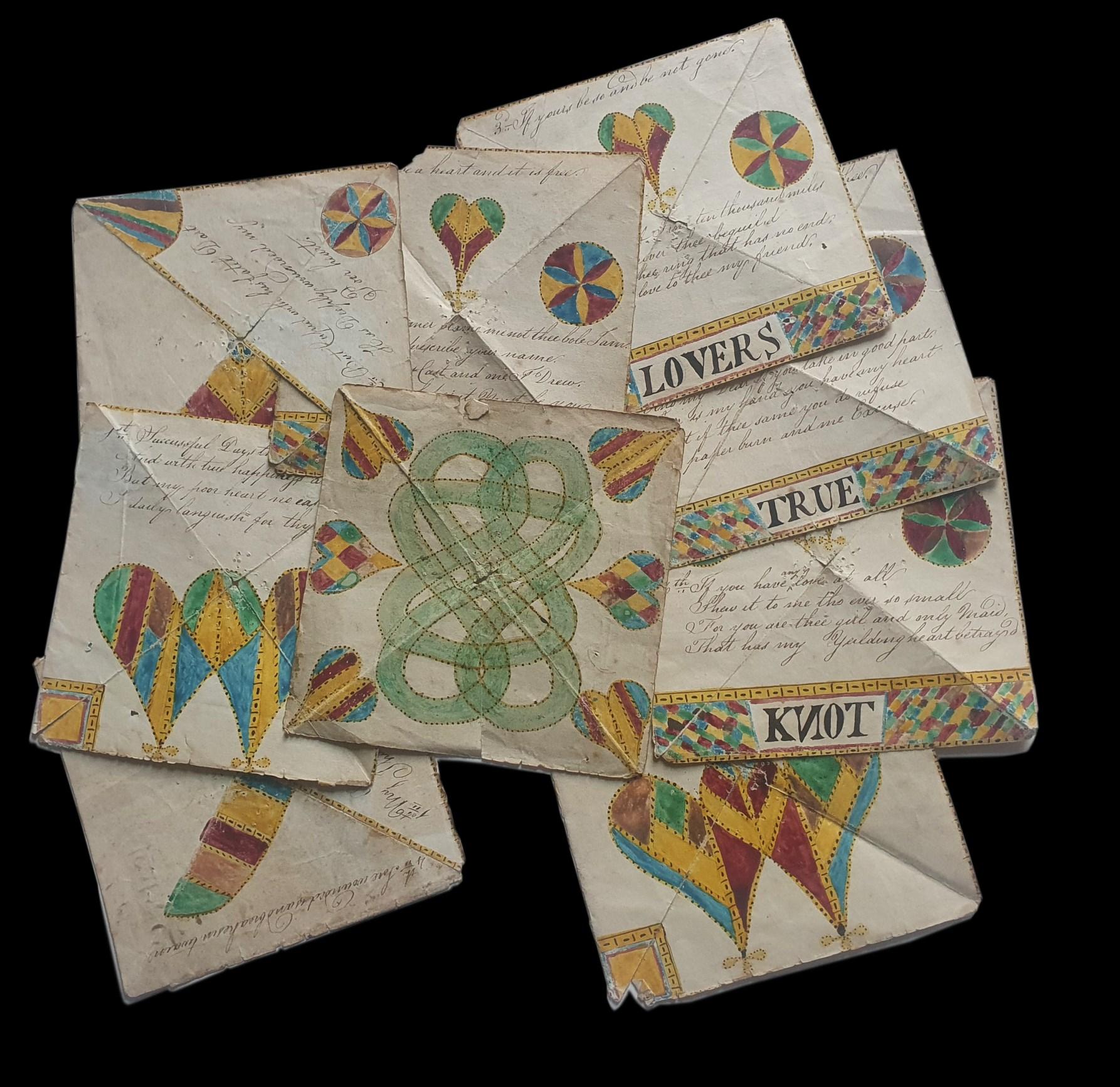

[CRAVEN, Elizabeth (née Skipworth) (1679-1704)] Late 17th-century culinary manuscript “The Lady Cravens Receipt-Booke”.

[Coome Abbey? Circa 1697-1704]. Folio (text block: 307 x 200 x 15 mm). [8 (title and index)], approximately 30 text pages, and over 130 blank pages. Contemporary panelled calf, neatly rebacked.

Watermark: Arms of Amsterdam (similar to Haewood 346-369, which he variously dates between 1670s and the 1710s); countermark: MHG interlinked. This combination is not in Haewood, but he does record a similar interlinked MHG in combination with a Fleur-de-lis (Haewood 1656, circa 1684).

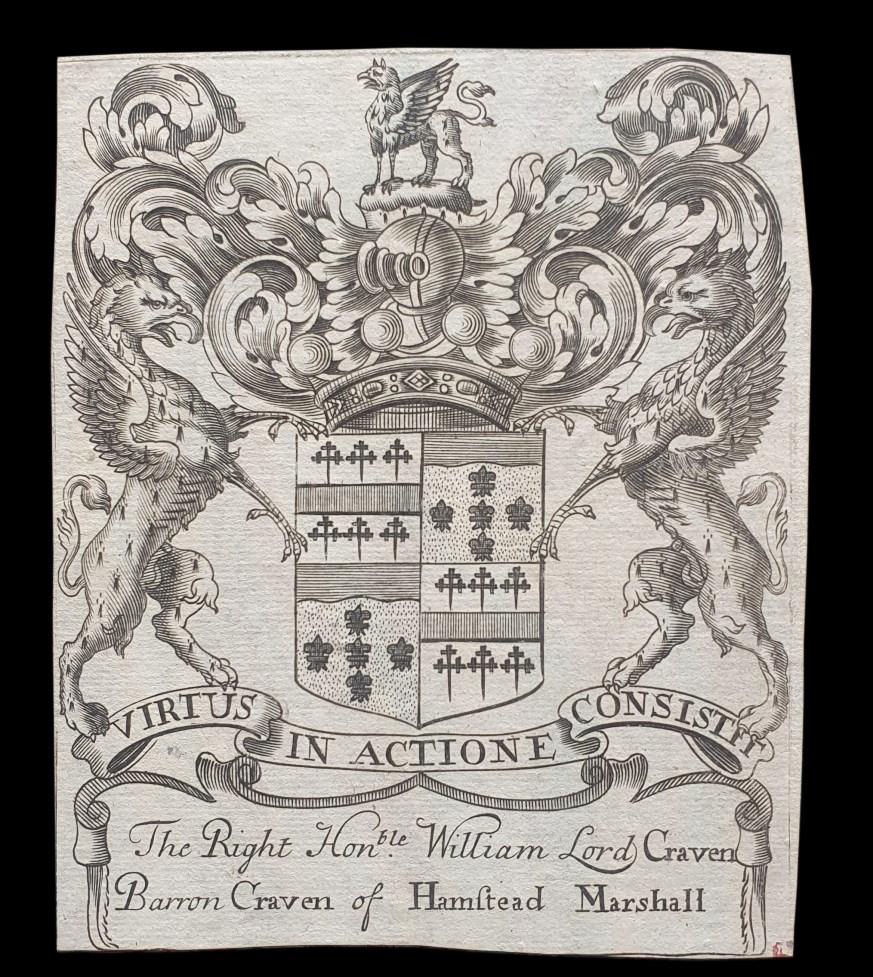

Provenance: Title page reads “The Lady Cravens Receipt-Booke”. Unusually large armorial bookplate to paste-down of “The Right Honble William Lord Craven Barron Craven of Hamstead Marshall”, with the motto “Virtus in actione consistii”.

opportunity to see the original intentions of its compiler who has clearly planned her layout in advance. Sadly, Elizabeth Craven died at the age of 25, leaving many eloquently empty pages.

DATING THE MANUSCRIPT

Elizabeth styles herself “The Lady Craven” on the title page, so the manuscript must have been written sometime between the date of her marriage in 1691 and her death in 1704. One useful piece of evidence is the several mentions of “Lady Bridgman” in the manuscript – a reference to a relative by marriage who only started using that title in 1702, which narrows the dates our manuscript to the period 1702-4. This strongly suggests that the manuscript was commenced shortly before Lady Craven died and would explain the large number of unused pages.

TWO

ARRANGEMENT

Lady Craven begins her compilation with a six-page index and then carefully arranges her recipes into four sections, each of which is separated by around 20 pages.

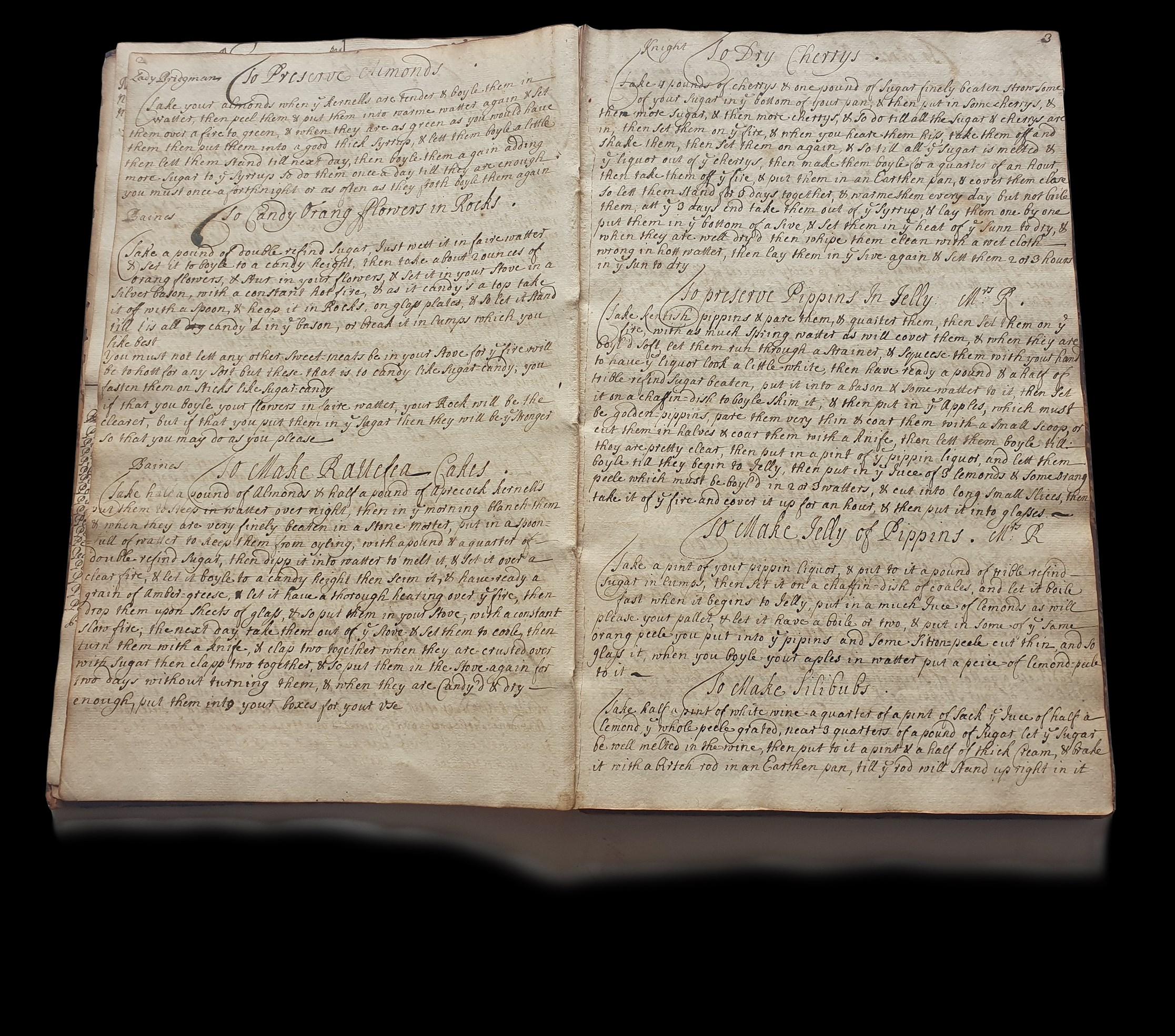

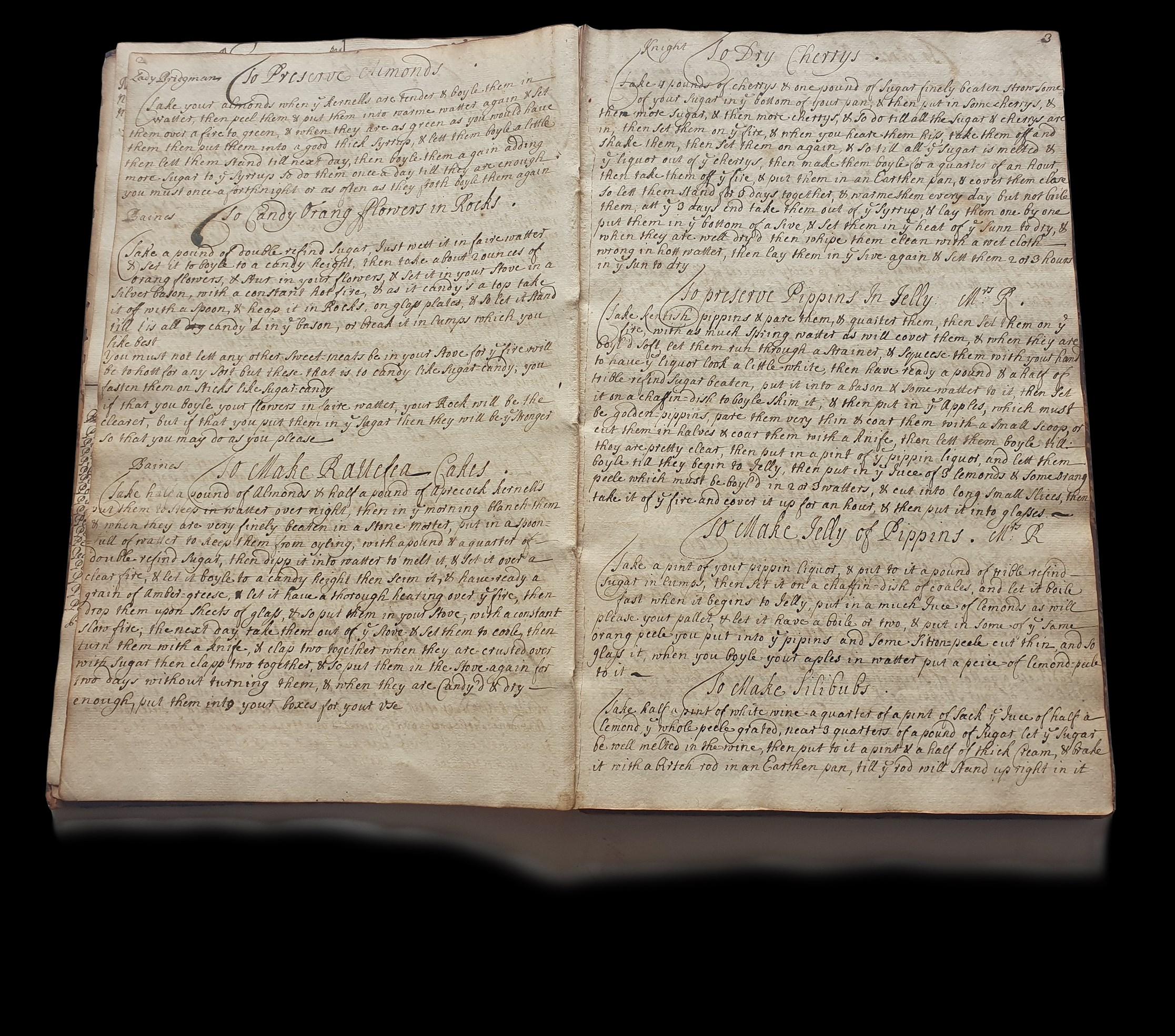

The first section (pp.1-7) contains 27 recipes for cakes, puddings and other sweet dishes including “To Candy Oranges Mrs Hudlestone”, “To make Comfitts”, “to Make Pistacho Cream”, “To preserve Pippins In Jelly: Mrs R”, “To make Silibubs”, “To Make Orang Cakes”, “Lady Anderson – To Make Fruite Biskett”, “The Spanish Cream”, “To Make Cloutted Cream”, “To Make Almond Cakes”, “Mrs Hudlestone – To Make Clear Cakes”, “To Make Cassia”, “To Make Pippin Marmelet R”, “To Make Lemond Cream”, “Lambert: To preserve Goodberry White”

The second section begins at p.55 and is represented by a single placeholder: presumably to have marked the beginning of a group of cordials and other medicaments.

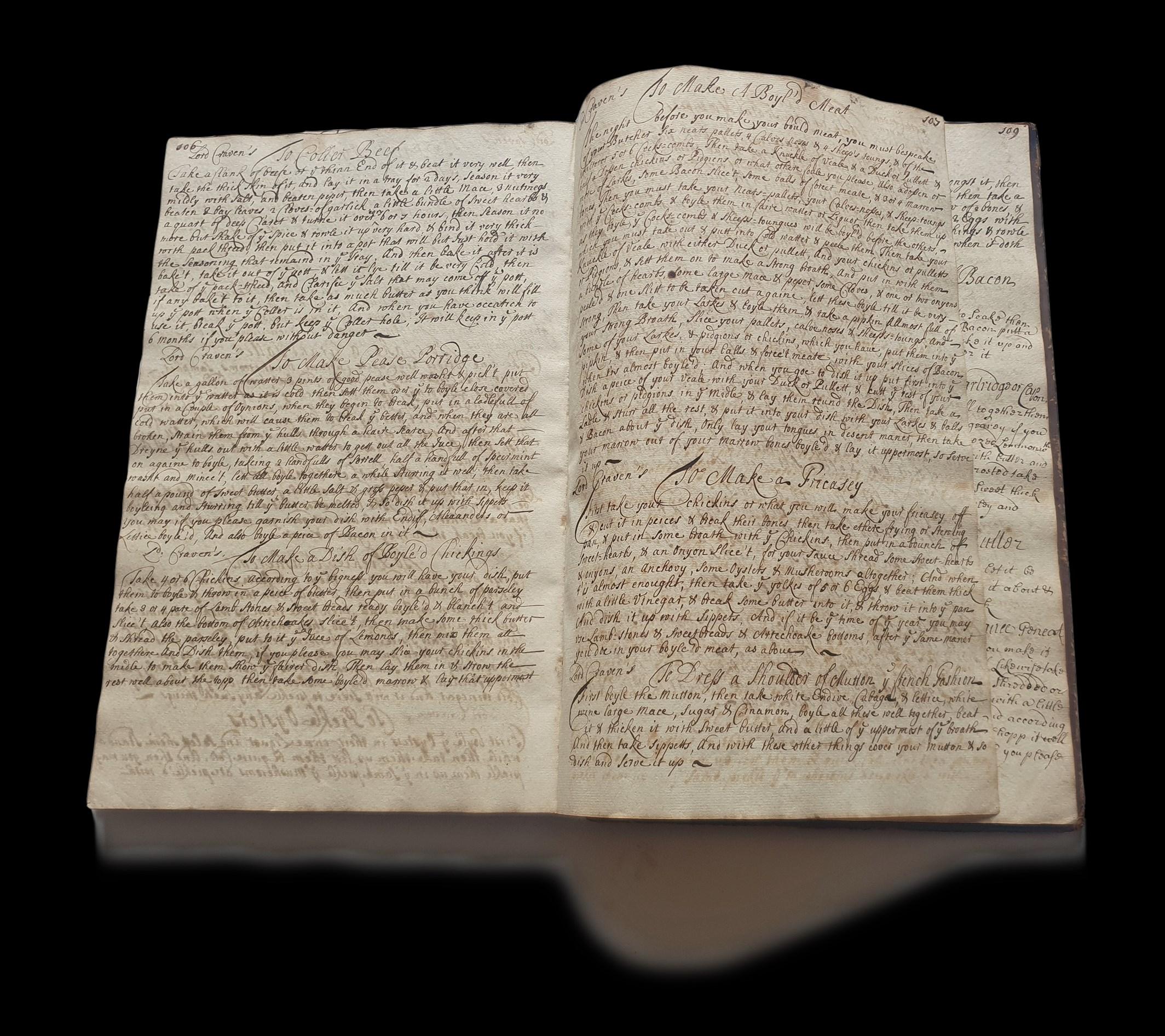

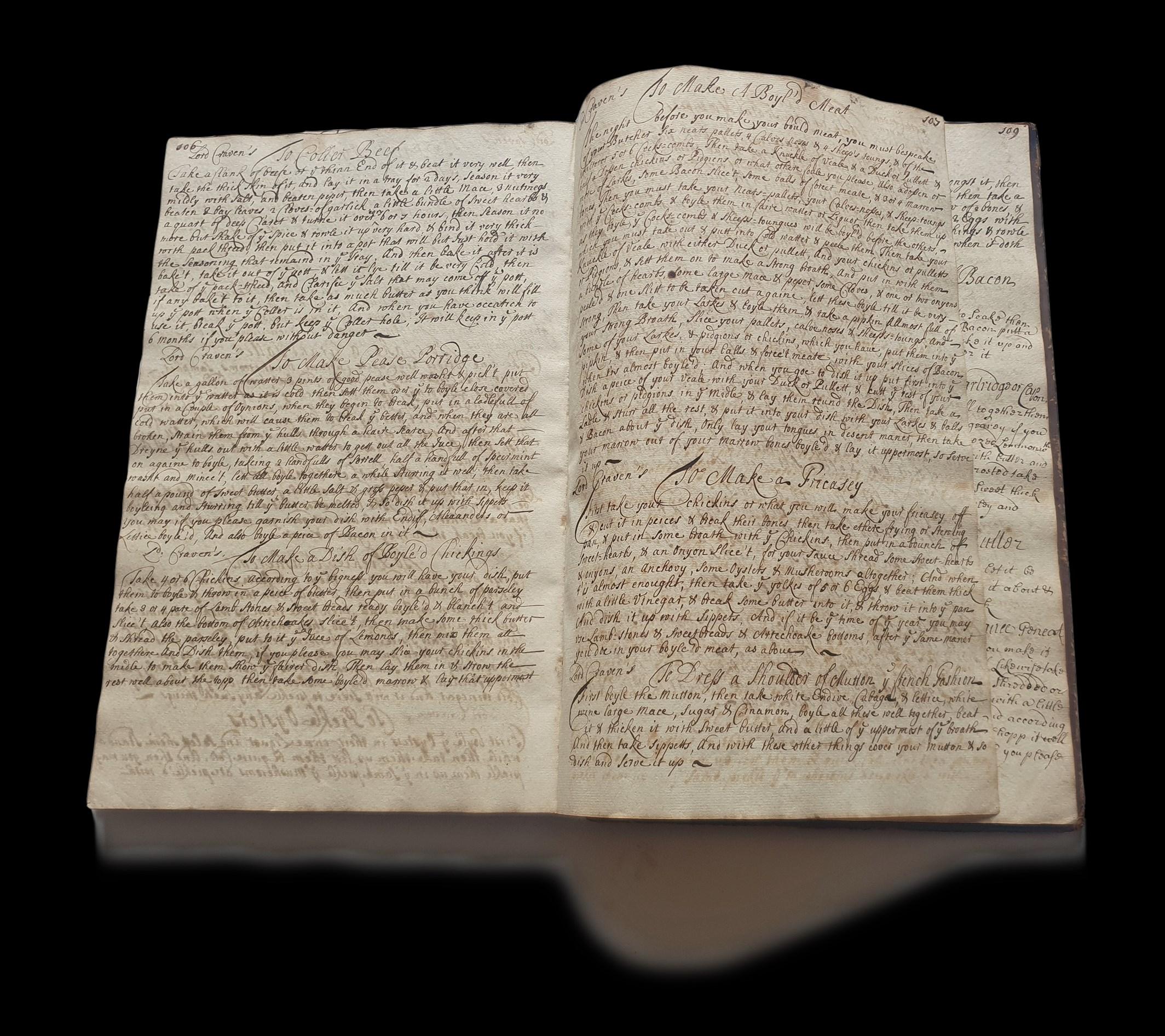

After another 20 or so pages, Lady Craven created the third section, which begins with around 43 savoury dishes, but then pivots back to cakes and puddings. This shift from savoury to sweet occurs midway through a large group of recipes attributed to “Lord Craven”, so the explanation for such a disruption so soon after she began the book seems to be simply that she continued her task of copying a batch without stopping to consider the order of things. Regardless, these recipes make for interesting reading. While many are for traditional fare (“To Salt Hams – Lady Bridgman”, “Lady Duncombe – To Ragow Pidgions”, “Lord Craven’s For a Haunch or Shoulder of Venison”, “Lord Craven’s To Boyle a Legg of Mutton”), vegetables make unusually frequent appearances for an early-modern cookbook: these include “Lady: D: To Make a Ragow of Musheroms”, “Lady: Db: To Make Pottato Pye”, “To keep Artichoakes for fricaseys”, “French Beanes to keep all ye year”, and “To Dress Mushrooms”.

Following another gap of 22 blanks, Elizabeth moves to dairy produce, with directions “To Make the Angelote Chese”, “To Make a Winter Cheese”, “Make little straw Cheeses”, “Make a Slipe Coat=Cheese”, “To Make Summer Cheese”, and so on.

INGREDIENTS AND INSTRUCTIONS

The Cravens are obviously wealthy enough to afford sugar in different forms (“good loaf sugar”, “double refined sugar”, “brown sugar”, “sack-sugar”, ffine sugar”), along with a multitude of other ingredients that include “oranges”, “Lemonds” “Carroway seeds”, “Pistachos”, “Almonds”, “Aprecock kernalls”, “Candid Eringo Roots”, plenty of meat and fish, and – as indicated above

an uncommonly healthy range of vegetables. The grandly named “Beef Royall” indulges in both the specific and the casual, calling for the addition of “truffles, pestatia=nutts” and specifically, “portugall=pease” but concluding vaguely that it may be garnished with “Carrotts Lemonds, & wth else you thunk fitt”.

The methods of preparation, too, indicate a certain level of resource, whether in time, equipment or fiddliness. To “Salt hams”, the “Lady Bridgman” recommends that it be “hung up in ye Chimney to dry but not to be blake a month or six weeks will dry it”; and the recipe for “Peloe” requires “2 loynes of mutton [...] some Cubbebs, cloves, large Mace, & whole pepper, & a handfull of shallots”, seasoning and “2 pound of Indian rice”, all of which are to be cooked “for 3 hours” in “a pan that can be close riveted down that no steam can get out” – then take “a fatt fowle very handsomely boyle’d” and “put it in ye midle”

The sweet side of things is represented by the likes of “Chocolett Cream”, which mixes cream and “one spoonfull of chocolet, & ye yolks of 2 Eggs & the white of one, then sweeten to your taste, let it boyle up [...] serve when it is cold”. We assume they cooked with chocolate fairly frequently, judging by the deployment of the eponymous “Chocolet pot”. Also on offer is a recipe “To Candy Orang fflowers in Rocks”, in which the mononymic “Baines” instructs the reader “to set it to boyle to a candy height [...] with a spoon, & heap it in Rocks, on glass plates, & so let it stand till t’is all dry candy’d in ye bason, or break it in lumps which you like best”

Then there is the exotic and slightly baffling “To Dress Indian Birds Nest”, which we have not been able to trace elsewhere, but which advises that “before you boyle them doe not forgett to Cutt them Small Otherwayes they will Look Like tow and by Consequence Loathsom”.

CONNECTIONS AND CUISINE

Lady Craven’s liberal use of attributions in these recipes evokes a web of social connections; and her background confirms it. In 1697, Elizabeth Skipworth (1679-1704) married William Craven, 2nd Baron Craven of Hampsted Marshall (1668-1711) to become Lady Craven. They appear to have had four children: William Craven, 3rd Baron Craven of Hampsted Marshall (17001739) and Fulwar Craven, 4th Baron Craven of Hampsted Marshall (1700-1764), Robert Craven (1703-1715) and John (1704-?). John’s birth is recorded the same year as his Elizabeth’s death, so it is plausible that both mother and son died during or near the time of childbirth.

The Skipworths and Cravens were both wealthy, influential, land-owning families whose alliance through marriage would have been advantageous to both sides, and also branched out to other families, extending their power and influence. The ostensibly simple act of exchanging receipts forming part of the complex social web that helped maintain the threads that bound these families together and maintained their hold on power and influence. Several of their connections are traced in this manuscript. “Lady Bridgman”, for example, who provides methods “To Preserve Almonds” and “To Salt Hams”, was an acquaintance via Elizabeth’s sister-in-law Mary Dashwood, whose sister, Susanna Dashwood (c. 1685-1747), married Sir Orlando Bridgeman,

–

2nd Baronet, FRS (1649-1701) in 1702 to become Lady Bridgman. Other prominent names include “Lady Anderson” (To Make Fruite Biskett”), “Lady Duncomb” (a.k.a “Lady: Db:”, “Lady D:”) who provides at least seven recipes, including “To Dress Ealls a la Matelote”, “a Ragow of Musheroms”, and “To Make Oyster Loaves”

Closer to home is a “Mrs Skipwith” (sharing Elizabeth’s birth name) who knows how “To Order Bacon Like Wesfalia”, and, closer still, “Lord Craven”, who provides no fewer than 30 recipes, mostly arranged together (as mentioned above) as if copied out at the same time. These are arranged alongside lesser-known figures such as a “Mrs R”, “Lambert” (who can “Make Nuns Bisketts” or “Rattafia Cakes”) and “Baines” who, besides “To Candy Orang fflowers in Rocks” (above), also knows how to “Make rattefea Cakes”. The use of initials and untitled surnames suggest these were perhaps servants. The abundant peppering of names of eminent persons i books often acts as a form but Lady Craven herself had nothing to prove: she came f prominent family, so it seems likely that her mentions of titled relations are present more as a matter of record than a selfconscious flaunting of family connections. Although, for tragic reasons, the book does not appear to have had much practical use, it nonetheless offers an unusual glimpse of the ordering and rapid disordering of early-modern cookbooks. The blank sections between Elizabeth’s bursts of culinary ambition give this volume an unintended flavour of poignancy.

SOLD Ref: 8141

Lady Craven's family tree, whic https://www.ancestry.co.uk/family-tree/person/tree/119332615/person/372037331956/facts

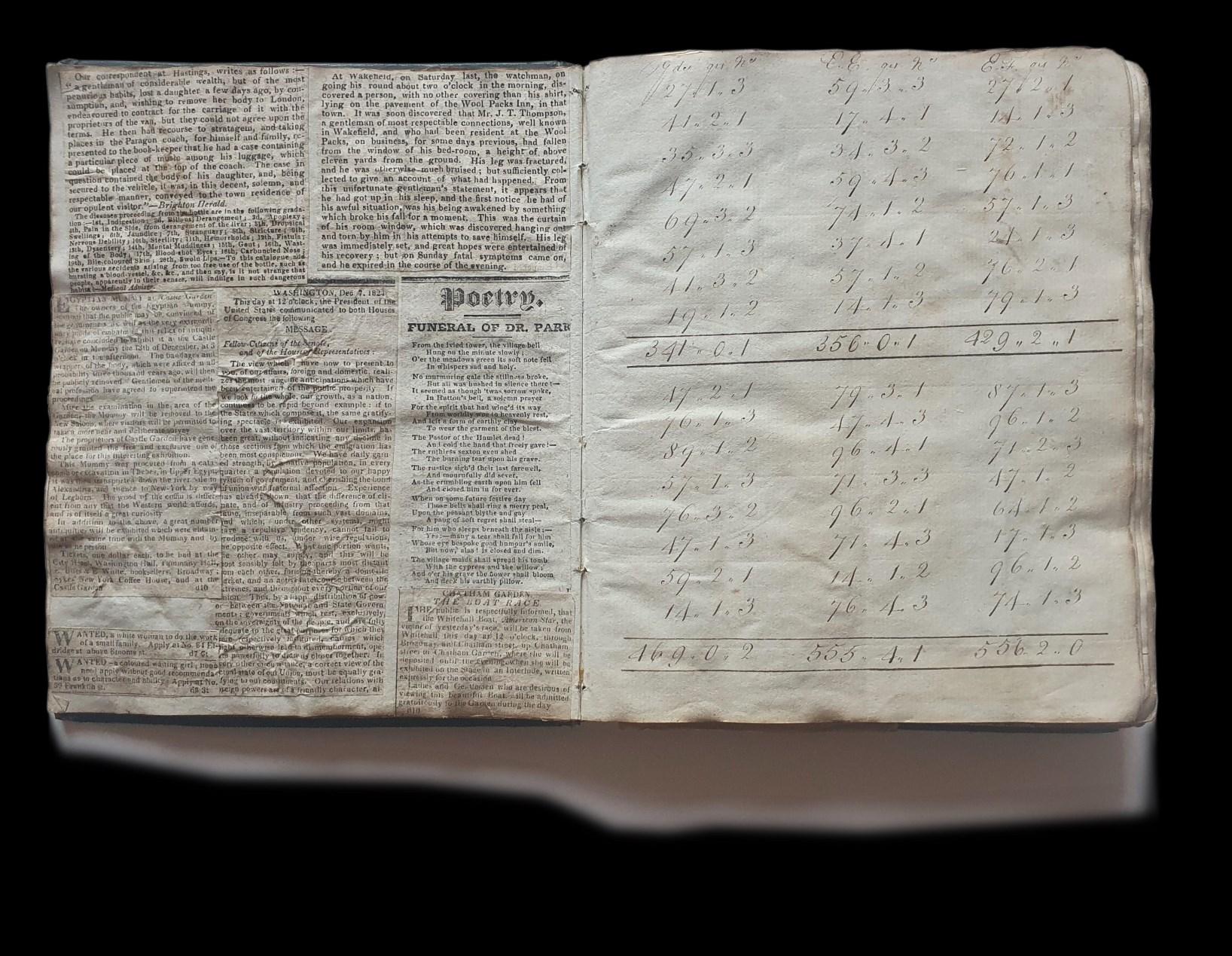

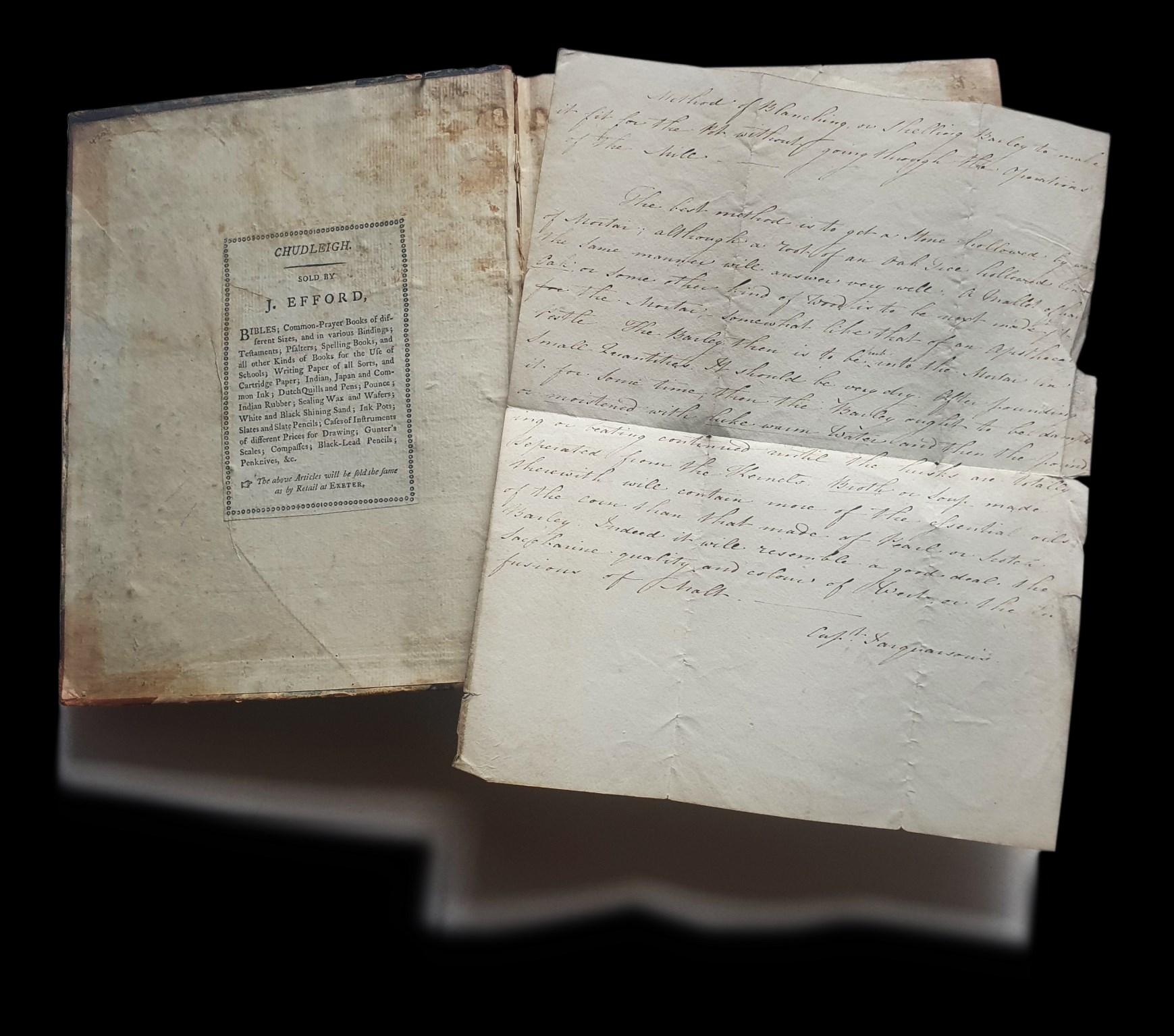

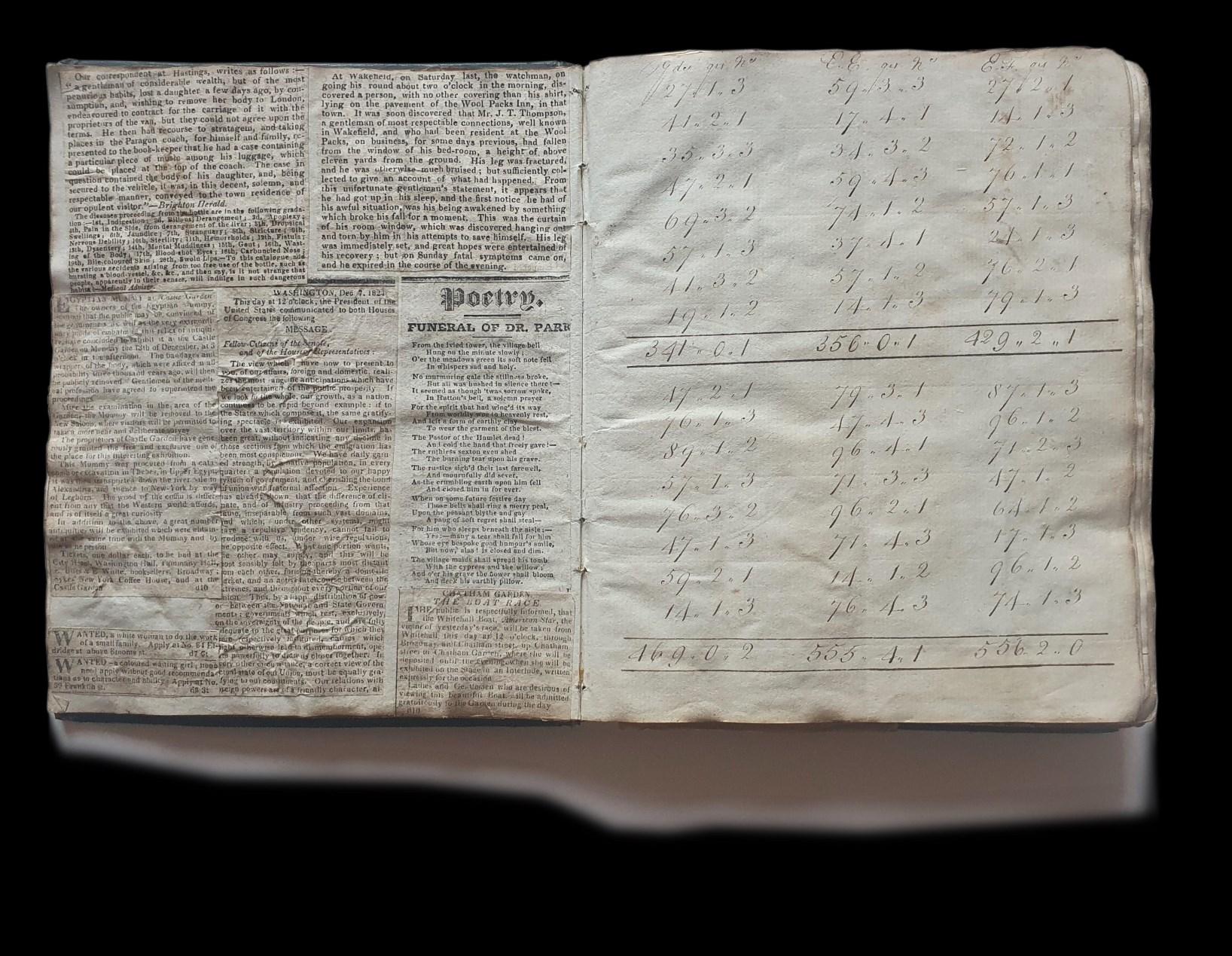

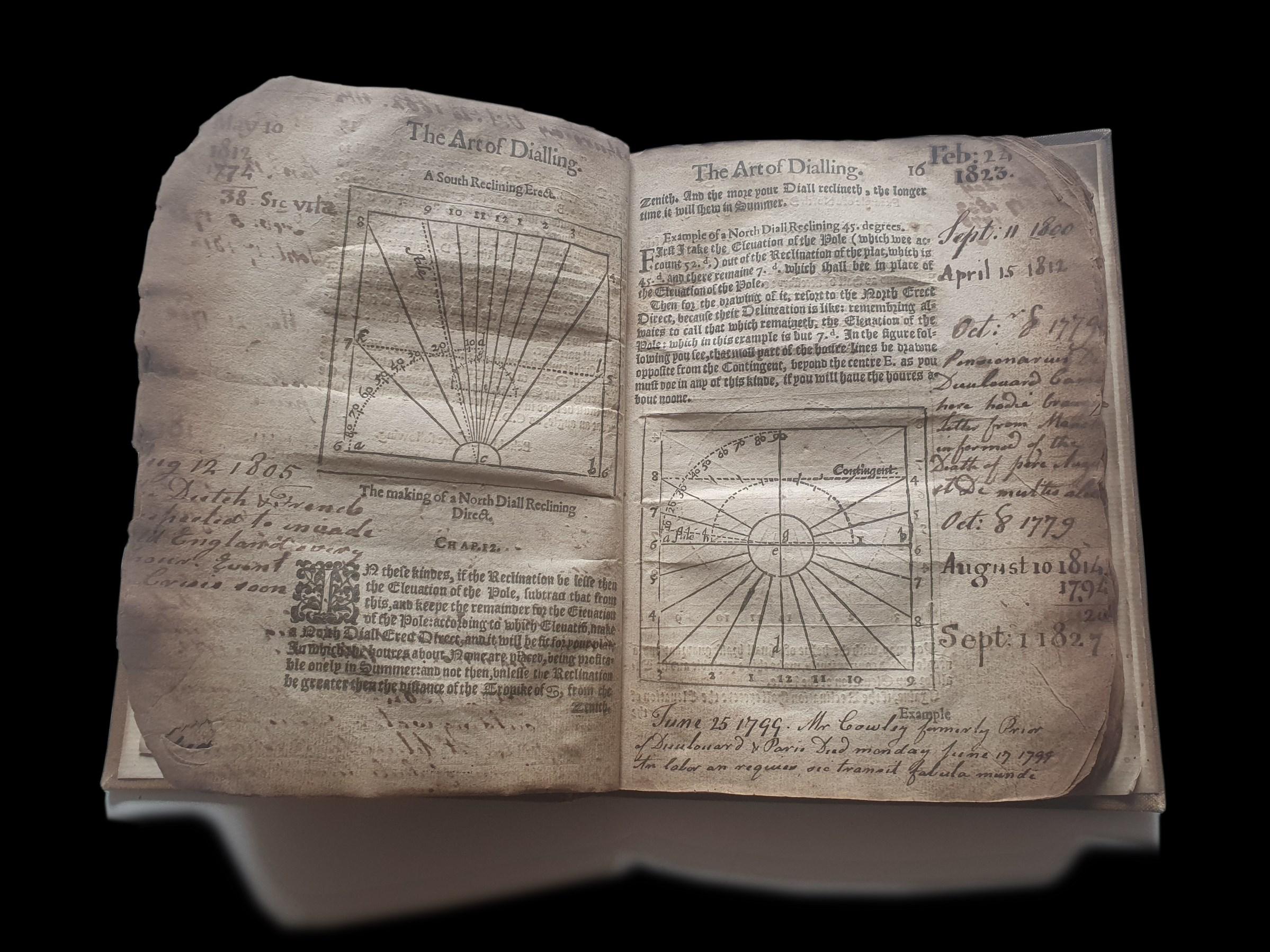

[PALMER, Samuel] Early 19th century manuscript ciphering, scrap and gardening notebook

[Cira 1800-20]. Quarto (195 x 160 x 25 mm). 170 leaves (of which approximately 40 pages are in manuscript text or calculations and 68 pages of printed scraps), a few leaves excised. Contemporary green vellum. Watermark: Britannia, letters MB beneath.

Inscription to pastedown reds

“Samuel Palmer His Book”

¶ This Georgian green vellum stationer’s notebook began as the schoolboy Samuel Palmer’s ciphering book, around the beginning of the 19th century. Palmer seems to have decided he no longer needed these notes and has repurposed the volume into a scrapbook and horticultural notebook.

Many of the scraps have been pasted directly over the earlier mathematical exercises, showing how Palmer’s requirements and concerns may have altered with maturity. They have been cut from printed texts, including journals and newspapers. Clippings include articles on fashion (“Female Fashions for April”), reports of crime (John Kent was tried of assaulting, with intent to kill”, “A most barefaced robbery”, “Human Flesh market”, “A Bailiff Outwitted”), auctions (“Dr Parr We have authority to state that there is no truth in the report, of the valuable Library of this celebrated man being shortly brought to the hammer”), the arts (“Chatham Garden Theatre, This evening, Dec 10, will be presented the Comedy of The Wonder”, “New Opera called the Saw Mill”), sport (“Warwick Races”), travel (“Margate-Eclipse steam Packet”) and other newsworthy events (“Death of Lindley Murray, the Grammarian”, “Remarkable Capture of a Hare”, “Defeat of the Royalists in Peru by Bolivar”).

Palmer has flipped the volume to incorporate manuscript recipes (“Receipt for the White Scale”, “A Method of Raising Mushrooms”, “Receipt for growing Potatoes in Winter”) and notes on horticulture, including lists of plants (“List of Vines”, “List of the Bulbs sent from Town”) memoranda on work carried out (“Shifted Pines Succession 26 February 1821 [...] cut cucumbers, Planted out Melons”) and descriptions of varieties of pine trees (“the Silver Striped Pine”, “the Queen Pine”).

£450 Ref: 8123

THREE

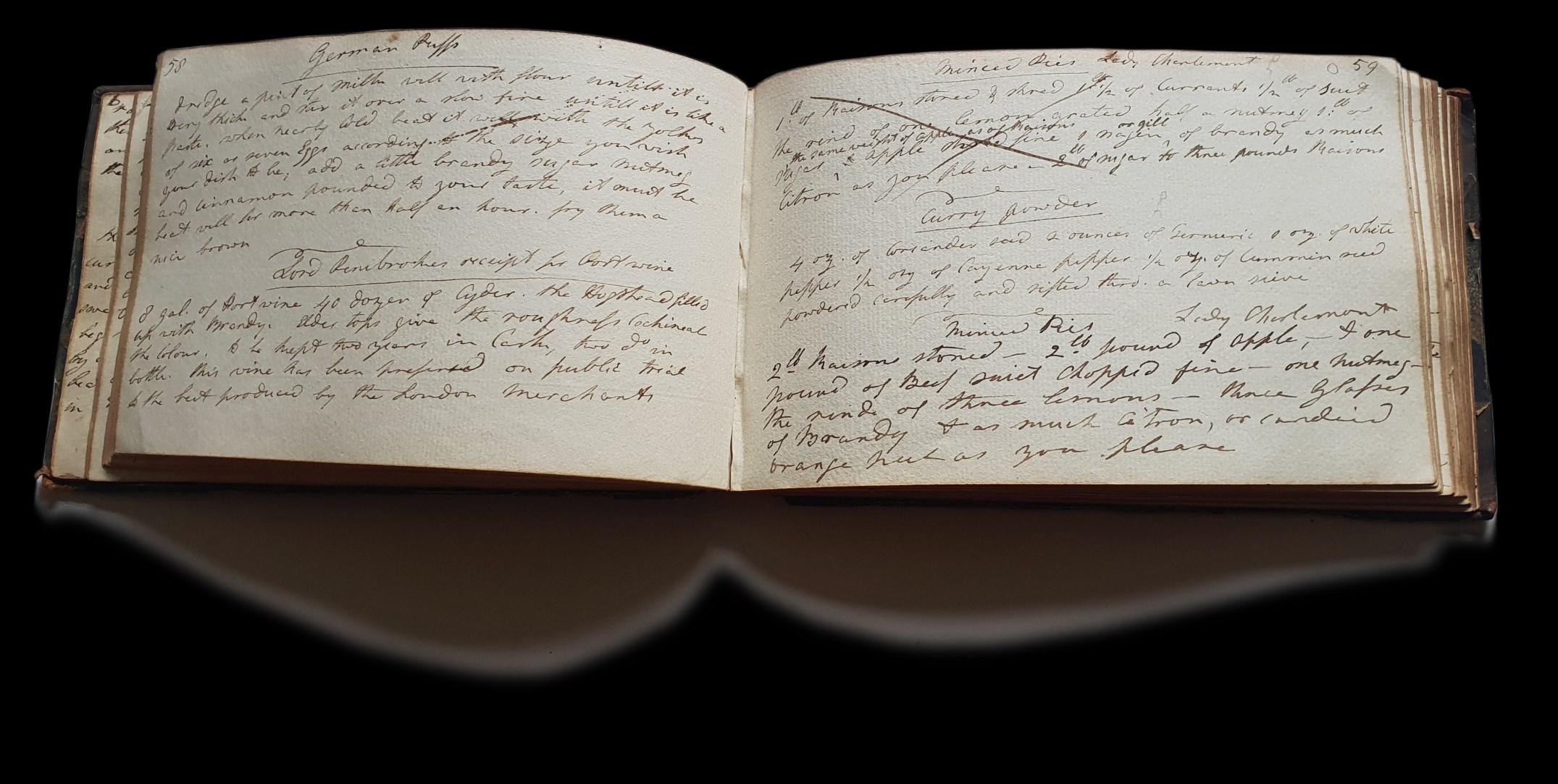

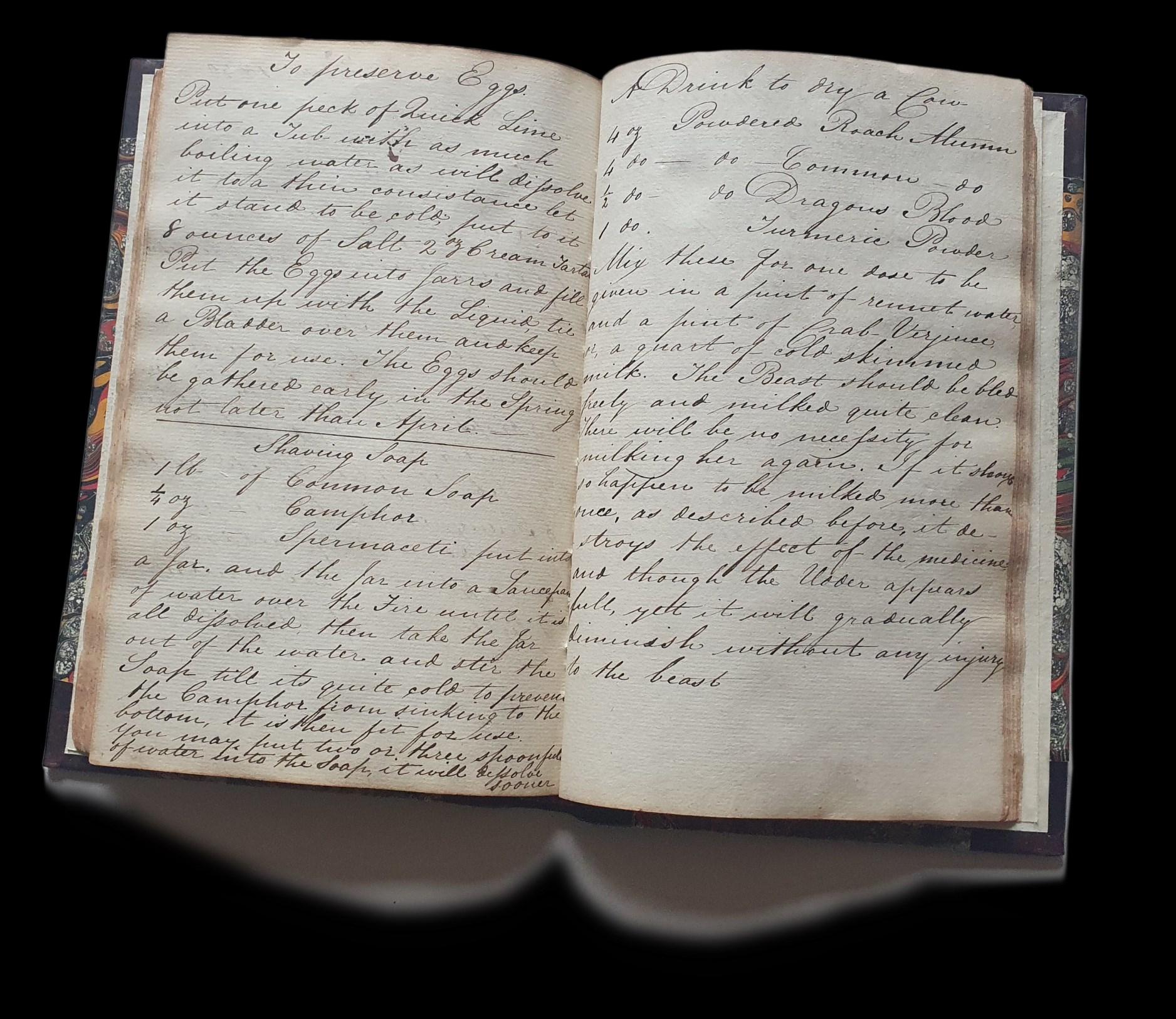

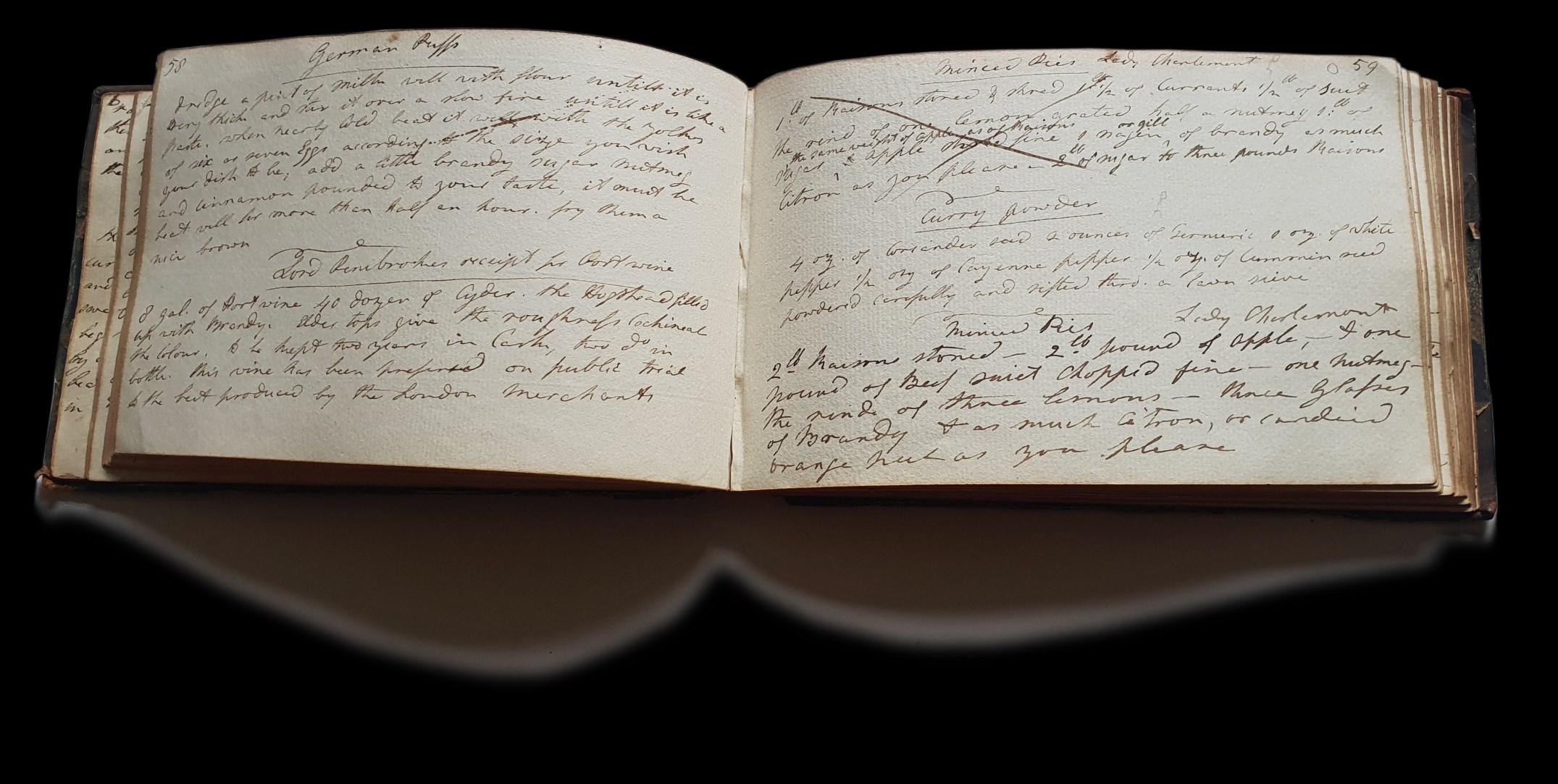

[SPERLING, Mrs] Manuscript book of recipes and remedies.

[Circa 1799-1815]. Oblong octavo (190 x 117 x 23 mm). Scraps pasted to front paste-down. [6, index] 177 numbered pages (included rear paste-down), a few newspaper cutting pasted in. Contemporary half calf, rubbed and worn., joints split Watermark: Fleurs-de-lis; J Whatman 1794. Inscription to front paste-down: “Mrs Sperling’s receipt book began about the year 1799”.

¶ This recipe book, belonging to a “Mrs Sperling”, takes the unusual format of an oblong octavo. The volume contains culinary recipes (written in multiple hands) as well household recipes and medical remedies. There are also a few culinary cuttings from newspapers which have been pasted in alongside the copied recipes.

Several of the culinary recipes are written for the “the poor” (“A Haggis for the poor”, “Cheap dish for the poor” p.45, “another cheap dish”), giving the impression that Sperling may, at least some of the time, have been cooking for others who were less fortunate. Some recipes are attributed (“Mrs Colville”, “Lady Charlemont”), but very few to specific publications, an exception to this being “Receipts for the Poor taken from The Cottage dialogues of Mary Leadbeater”.

Also included are a range of culinary recipes such as “Cheese on Toast”, “Chicken & Rice”, “Oyster Sauce”, “Milk Lemonade” and “Buttered Tart”. The volume has clearly seen action: some recipes have been crossed through, presumably where Sperling has found them unsatisfactory; others have small adjustments and notes added (“Instead of Turmeric and Keyanne Pepper, add two large tea spoonful of curry powder”) which further suggest that the volume was consulted frequently. Some recipes, in both the index and the pages, have been marked with “X” or “O” – probably to signify a pattern of usage (perhaps to indicate those to be shared with others). The latter half of the volume mainly contains medicinal remedies (“For a Cancer”, “Violets for coughs”, “Epilepsy”) and household recipes (“Wash Balls”, “Cleaning Linen by Steam”, “to die green”).

FOUR

SOLD Ref: 8143

FIVE

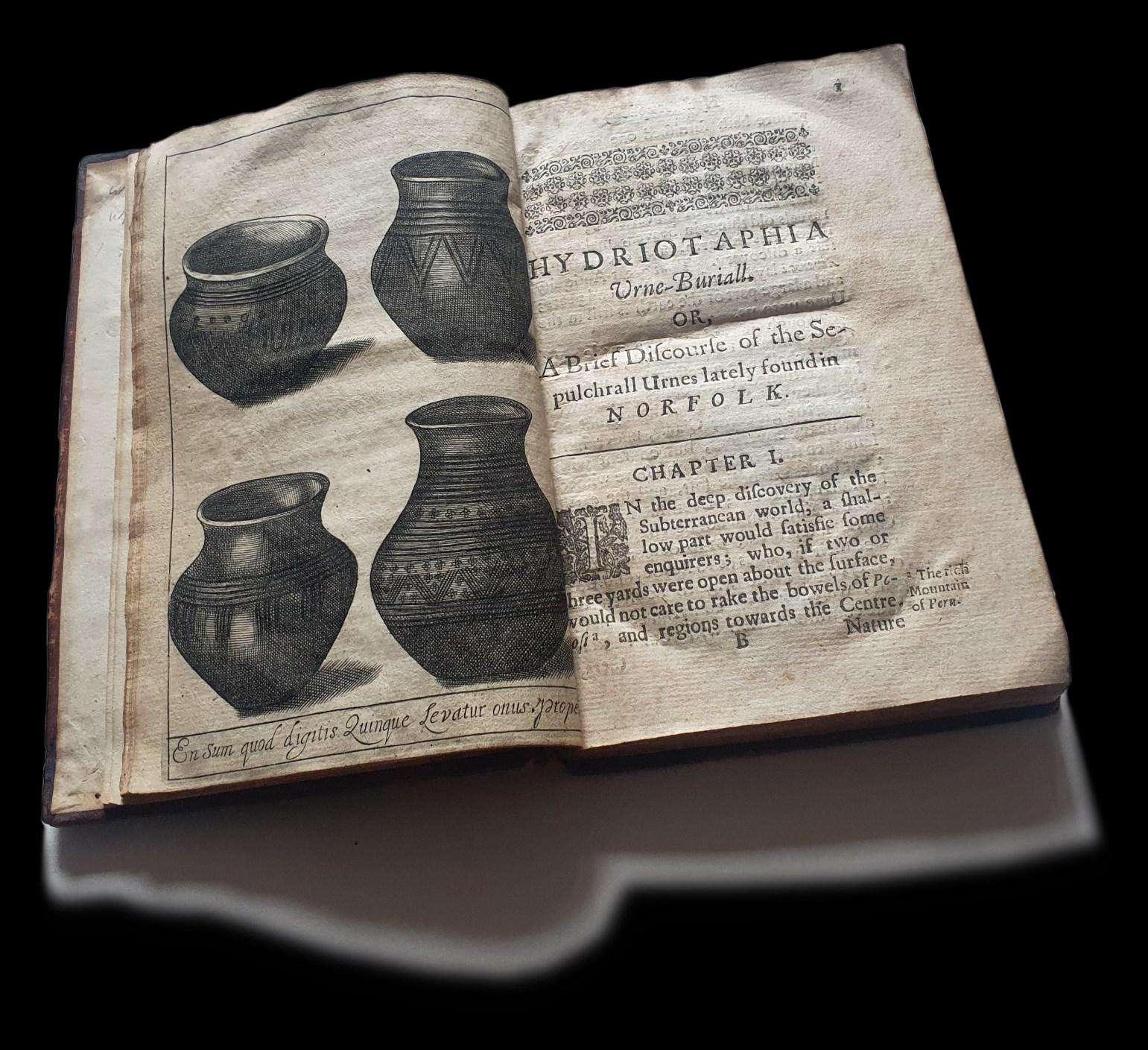

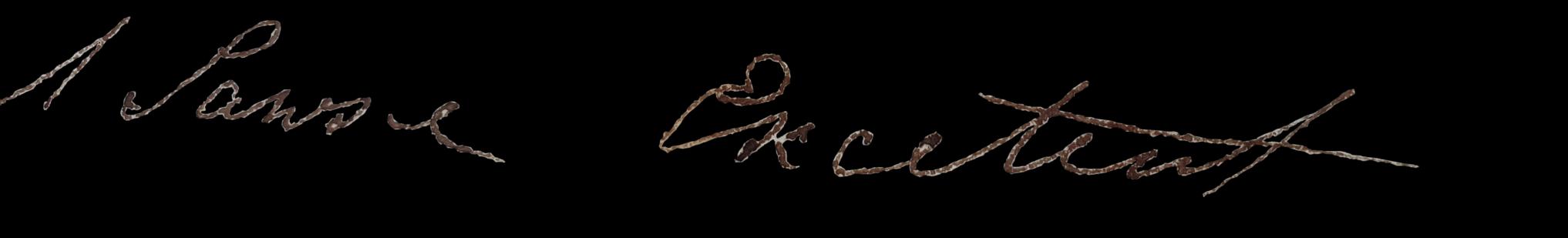

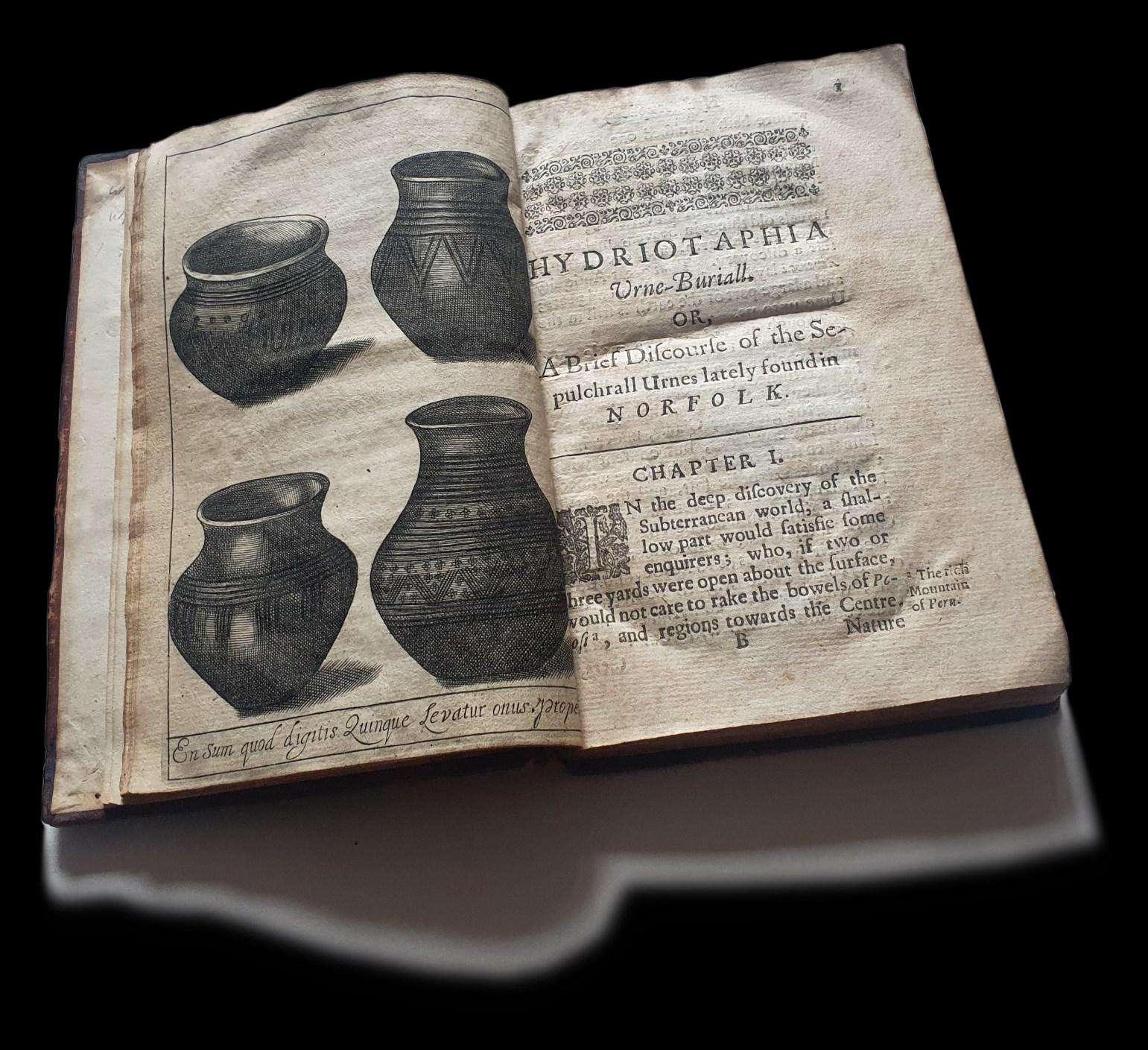

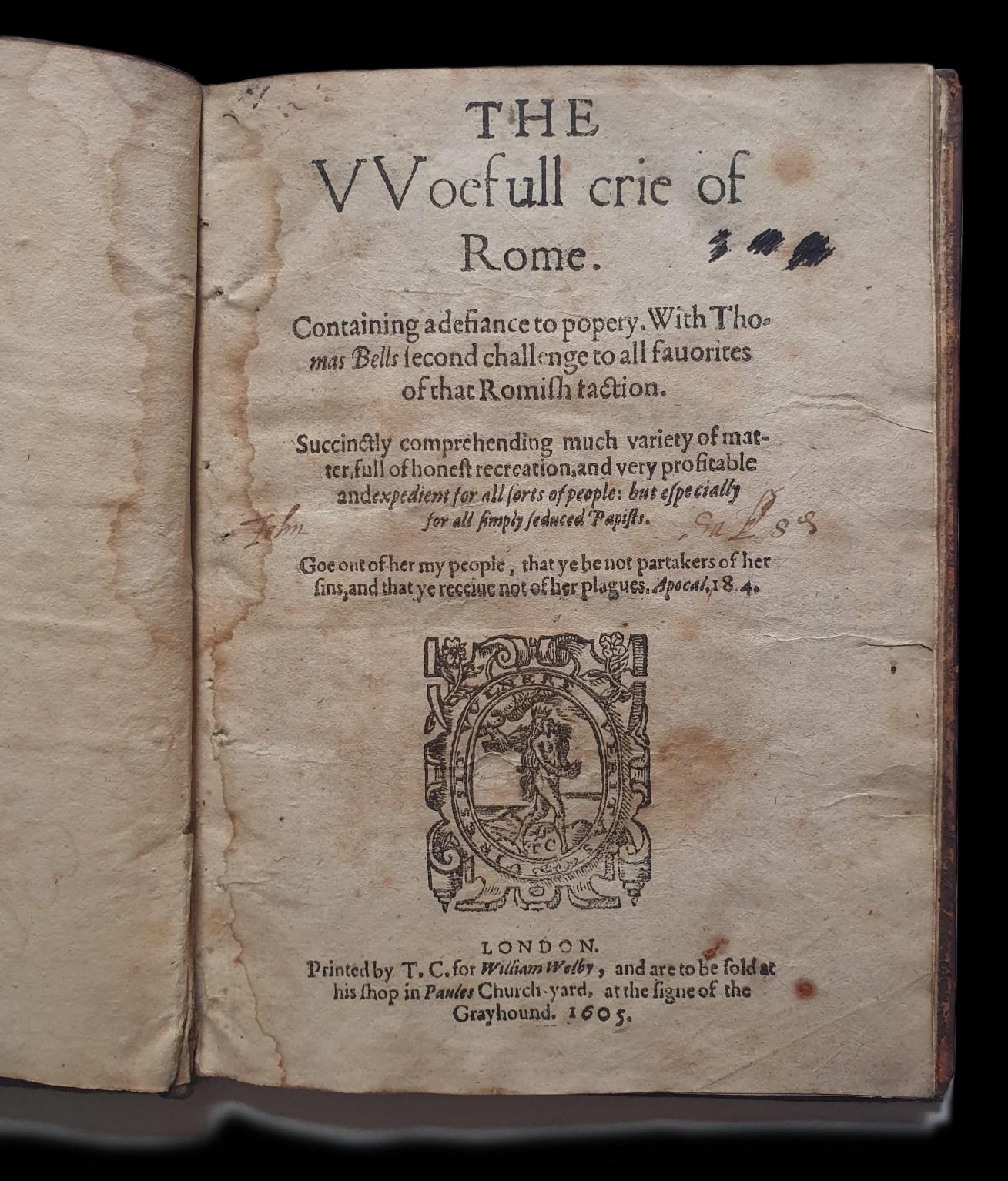

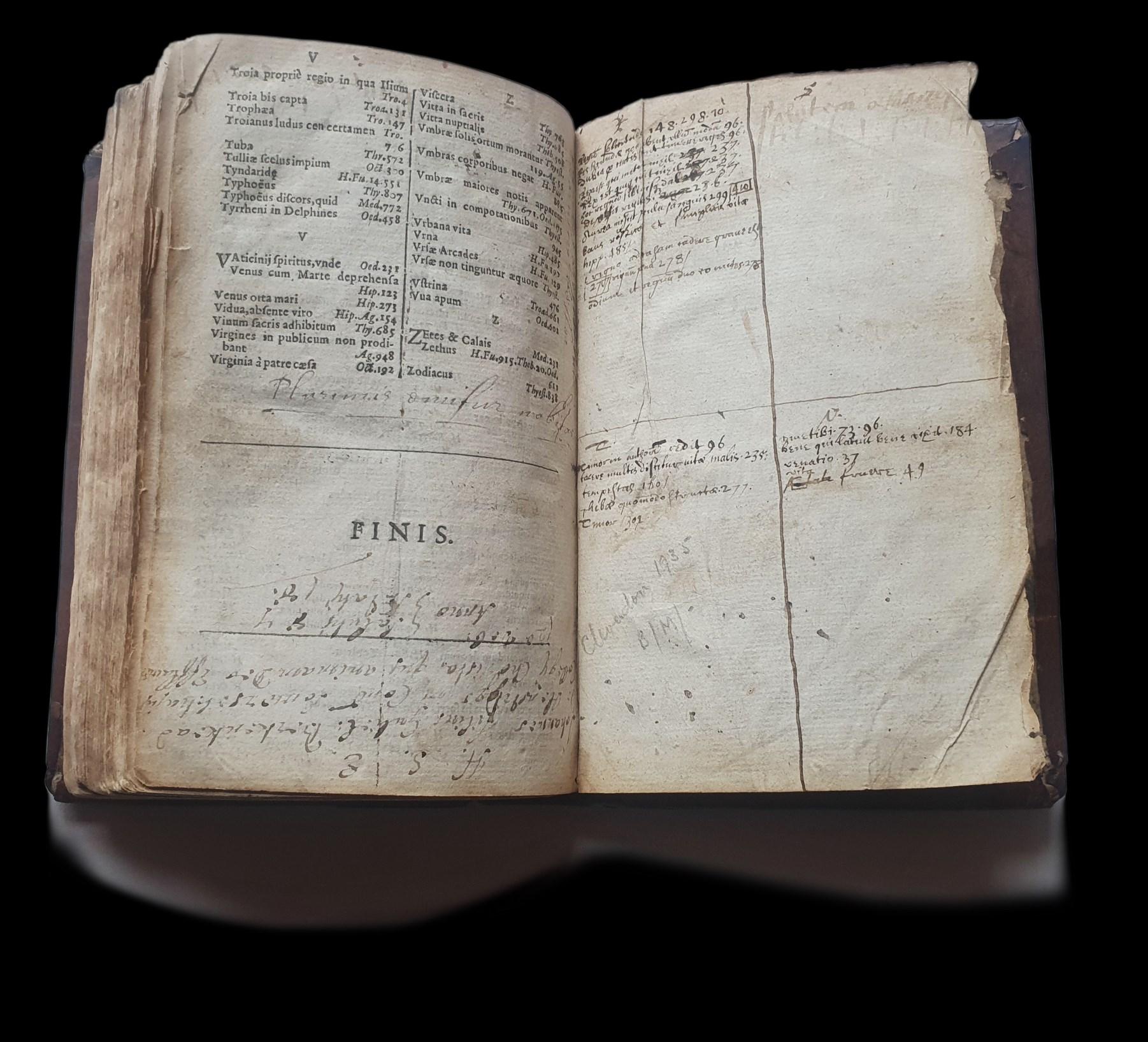

CORYATE, Thomas (approximately 1577-1617). [Coryats crudities; hastily gobled vp in five moneths trauells in France, Sauoy, Italy, Rhetia co[m]monly called the Grisons country, Heluetia aliàs Switzerland, some parts of high Germany, and the Netherlands; newly digested in the hungry aire of Odcombe in the county of Somerset, & now dispersed to the nourishment of the trauelling members of this kingdome.

[London: printed by VV[illiam] S[tansby for the author], anno Domini 1611]. FIRST EDITION.

Quarto. Pagination [196], 364, [23], 366-393, [23], 395-398, 403-655, [51] p., 4 engraved plates (3 folding: Clock, Stupendious Vessell, Amphitheatre of Verona), single plate present together with a copy of the same scene from the 1776 edition (both trimmed to plate edges and mounted), full-page sunburst woodcut of the Prince of Wales’ feathers, engraved portrait on p.496, text engraving of a dragon on Bbb3 verso, errata leaf at end. Text clean, a few small tears to margins very neatly repaired. Note: lacks the additional engraved title page, which is supplied in facsimile. Bound in 19th century morocco, rubbed and some wear, all edges gilt. [STC, 5808; Keynes, Donne 70; Pforzheimer 218].

¶ Thomas Coryate was perhaps one of the earliest models for our modern notion of ‘an Englishman abroad’ – well-connected, intrepid, learned, curious, foolhardy and often insensitive, Coryate travelled extensively, taking in continental Europe, Turkey, Persia and India. He often absorbed these environments at great length and made influential friends, before capping his archetype of the blithe British adventurer by dying of dysentery in Gujarat.

Coryats Crudities was the product of his first journey, in 1608, through France and Italy to Venice (en route becoming possibly the first of his countrymen to discover two Italian ‘innovations’, the table fork and the umbrella), then homewards via Switzerland and Germany. Written as a spur to his peers to broaden their outlook by undertaking such travels (anticipating the Grand Tour), the book “contains illustrations, historical data, architectural descriptions, local customs, prices, exchange rates, and food and drink, but is too diffuse and bulky […] to become a vade-mecum” (ODNB). The collector Carl Pforzheimer summarized both Crudities and its author when he remarked: “There has probably never been another such combination of learning and buffoonery as is here set forth”.

Coryate sought testimonials from fellow writers to include in the first edition of Crudities; the contributors of these mostly mock-heroic verse included Ben Jonson, John Donne, John Harington, Michael Drayton and other luminaries of the ‘Mermaid Tavern’ set of which he was also a member.

SOLD Ref: 8103

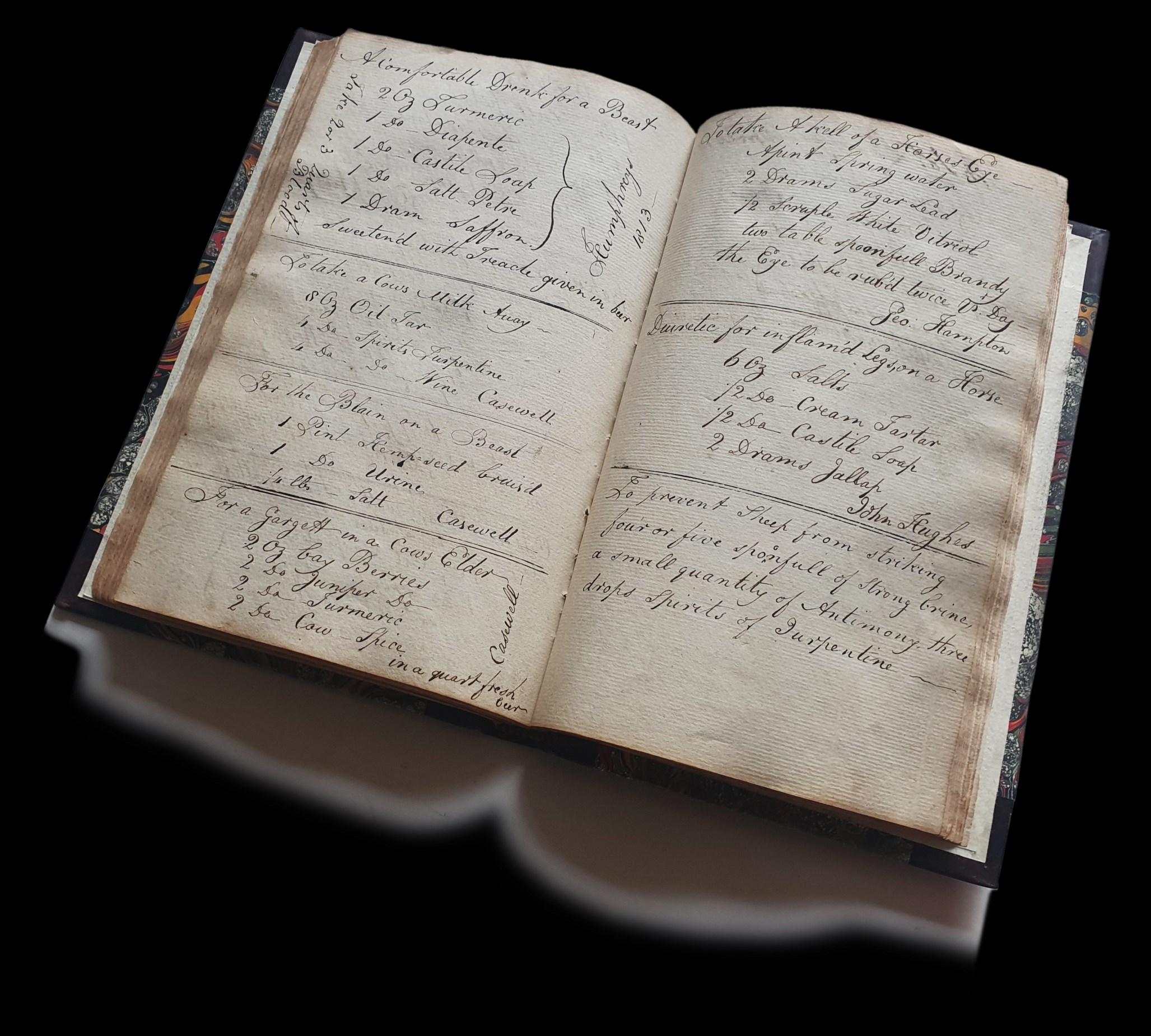

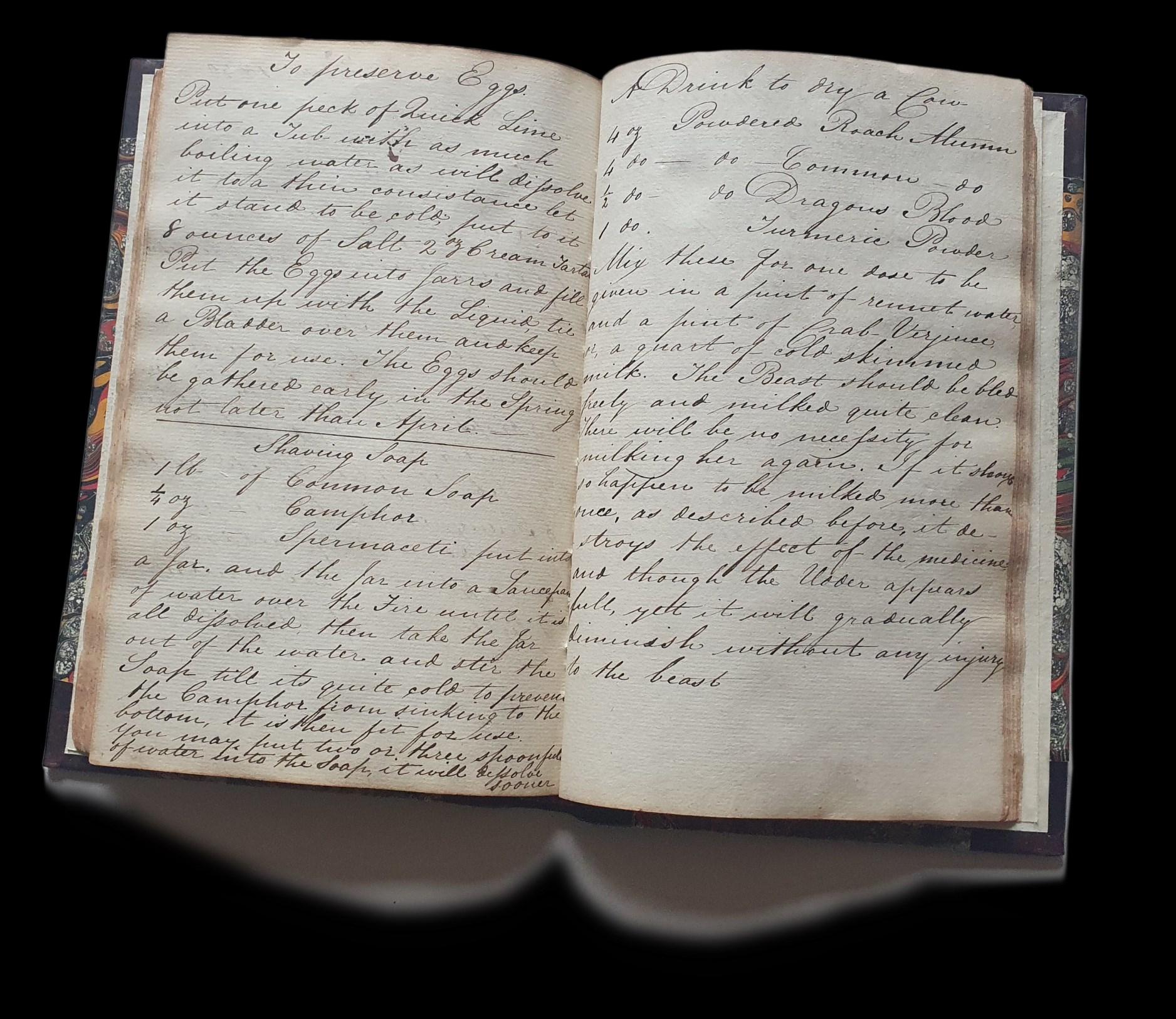

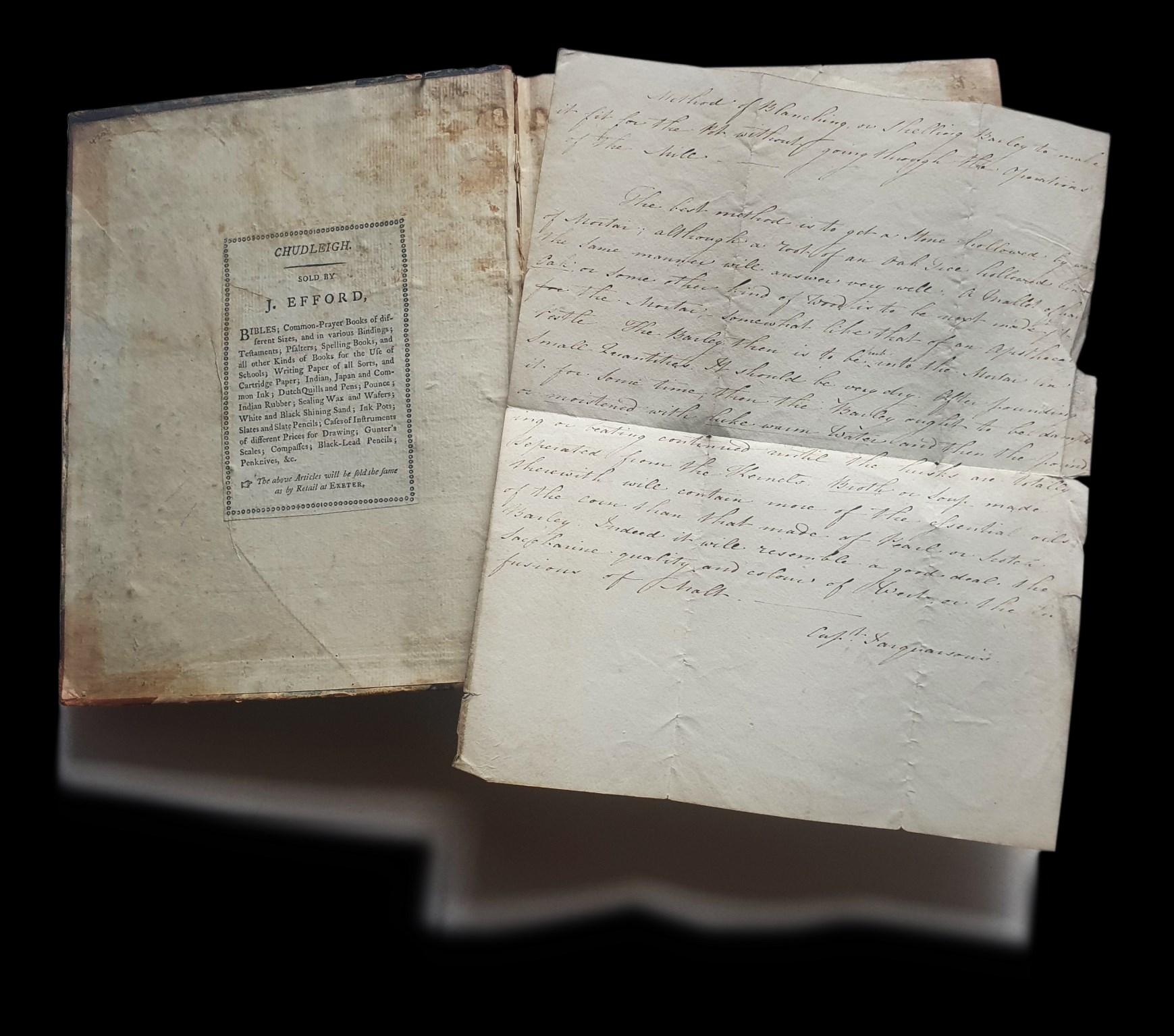

DOWNING, J. A treatise on the disorders incident to horned cattle, comprising a description of their symptoms, and the most rational methods of cure, founded on long experience. By J. Downing. To which are added, receipts for curing the gripes, staggers, and worms in horses; and an appendix, containing instructions for the extracting of calves.

[Stourbridge]: Printed and sold at Stourbridge. Sold also by T. Hurst, Messrs. Longman and Rees, Paternoster-Row; and Messrs. Rivington, St. Paul’s Church-Yard, London, 1797. Reissue of the first edition, published the same year. Octavo. Pagination xii, 131, [1], xiv (misnumbered ziv), [4] p. Lacking the half-title. Numerous blanks bound in at the end, with manuscript remedies to 14 pages. Modern half calf, marbled boards, endpapers renewed, some marks and browning to text.

¶ Downing’s treatise contains details of symptoms and treatments for diseases in cattle, together with a small number of remedies for maladies in horses. Of its over 250 listed subscribers, many are local to Stourbridge or Worcestershire generally, from where the author hailed. Many were presumably landowners, yeomen or people otherwise directly concerned with farming, but the list also includes professions such as surgeon and druggist, and of course booksellers.

Whichever of these groups our scribe belongs to, they have augmented the work into the 19th century, adding some 31 recipes and remedies (variously from 1803 to 1840) including “For Black Water in Cattle”, To Prevent Calves Striking”, “For a Gargett in a Cows

SIX

Elder”, “To take A kell of a Horses Eye”, “Diuretic for inflam’d Legs, on a Horse”, and “To prevent Sheep from striking”. Most simply list ingredients and quantities, but there are short notes (“the eye to be rub’d twice pr Day”), and some more detailed instructions like: “The Beast should be bled freely and milked quite clean. [...] If it should so happen to be milked more than once [...] it destroys the effect of the medicine [...] though the Udder appears full, yet it should gradually diminish without any injury to the beast.” Among all the practical remedies for animals, they’ve allowed themselves some indulgence, judging by “To make Punch Ice”

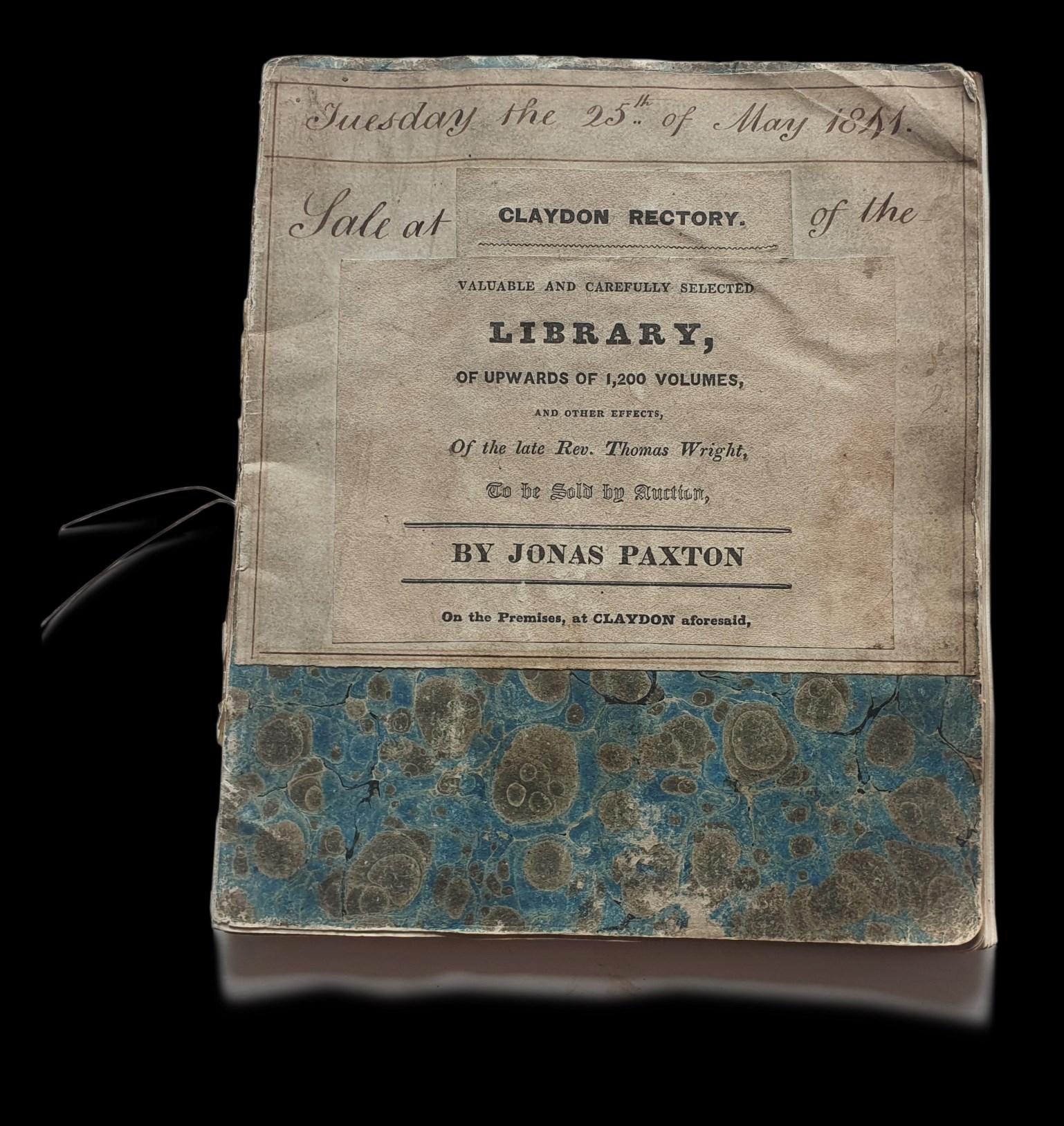

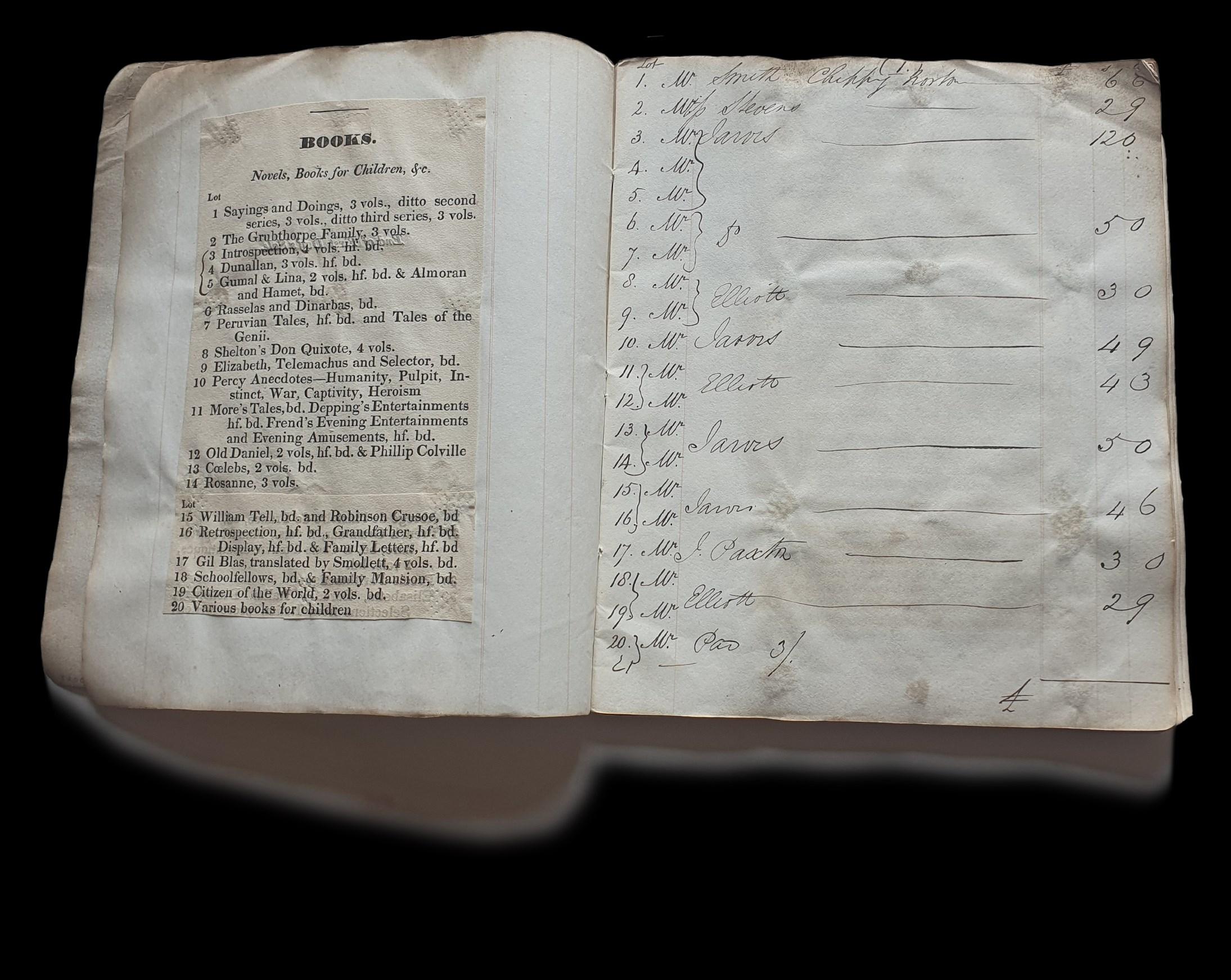

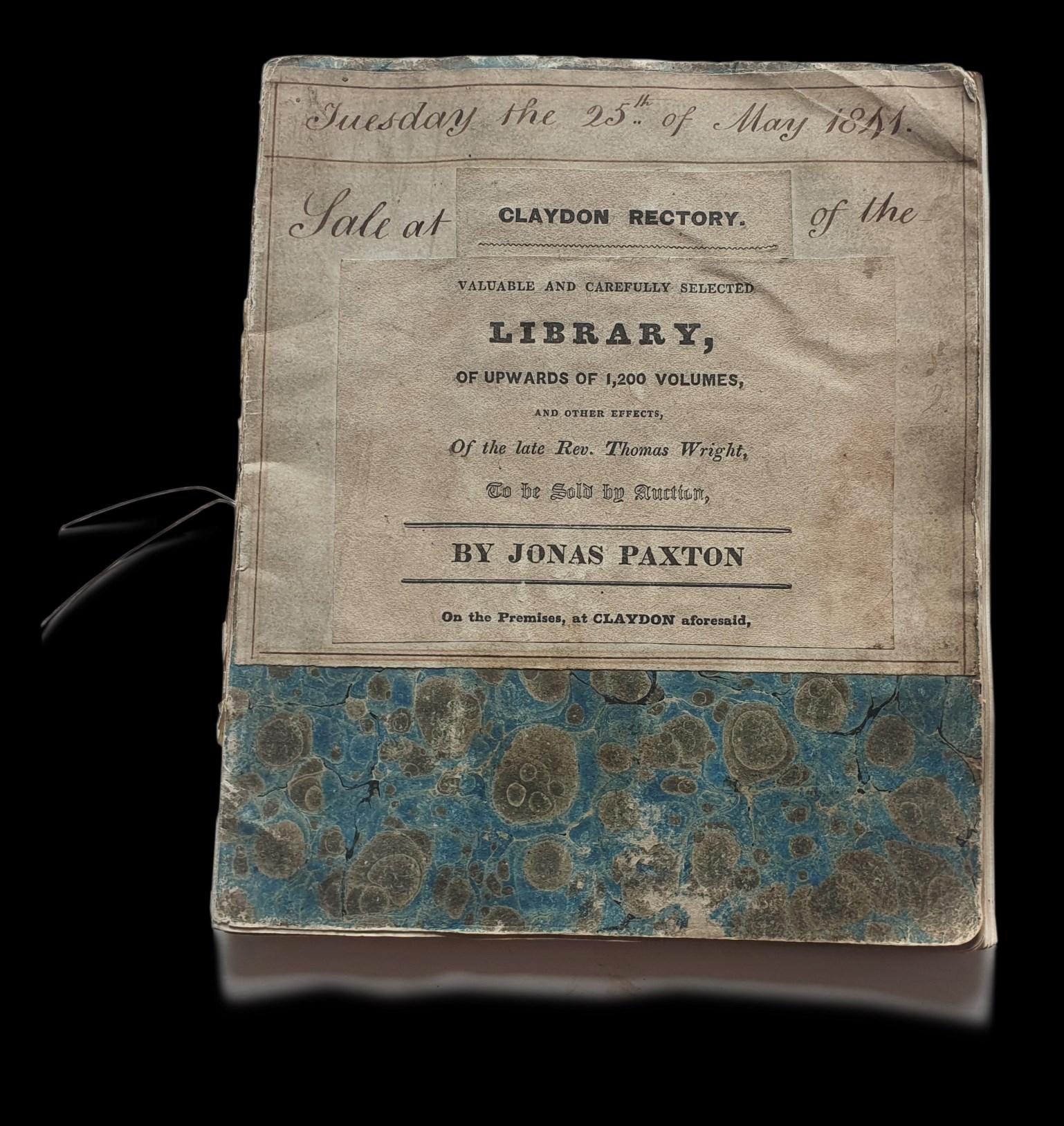

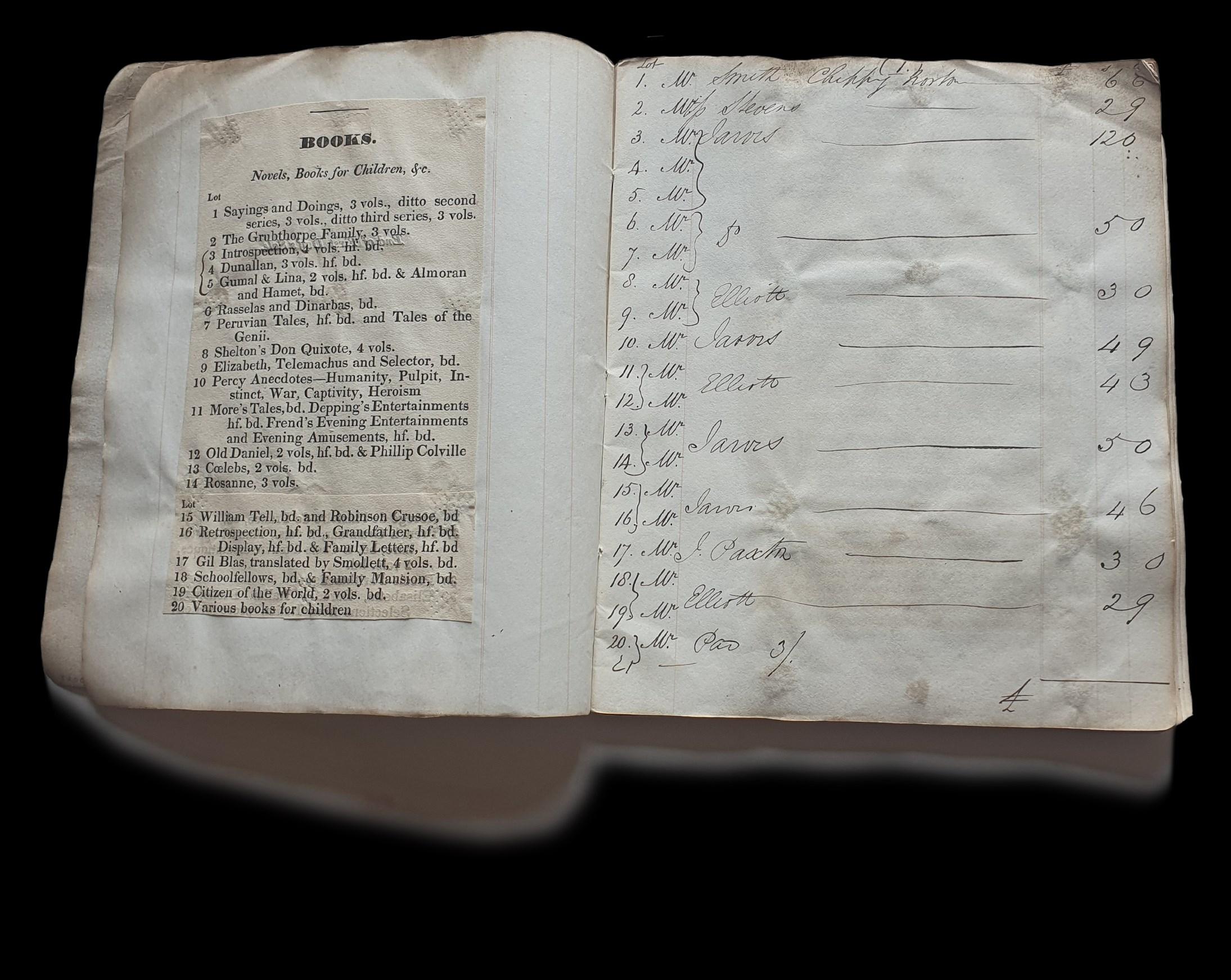

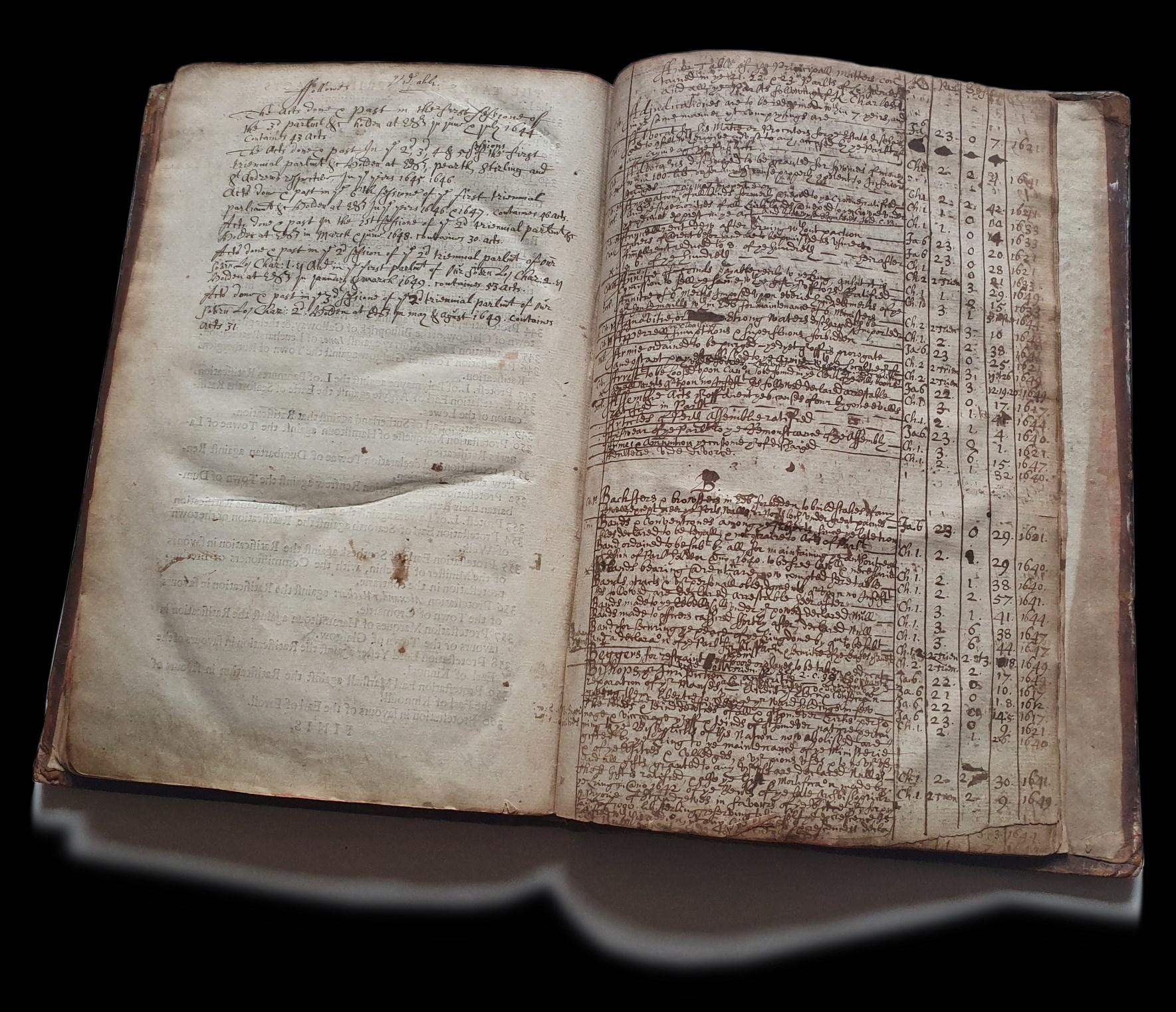

[WRIGHT, Rev. Thomas (c.1775-1841); PAXTON, Jonas] Claydon Rectory. Valuable and carefully selected library of upwards of 1,200 volumes, and other effects, of the late Rev. Thomas Wright, to be Sold by Auction, by Jonas Paxton. On the Premises, at Claydon aforesaid. [Claydon Rectory, Buckinghamshire. Circa 1841]. Slim quarto (193 x 162 x 4 mm). There are 21 sheets (plus a sliver of one sheet) of two octavo printed catalogues. These sheets have been trimmed and pasted to the versos of quarto stationer’s book. The title of one of the catalogues has been trimmed and pasted to the front cover, with details of the date of the sale added in manuscript.

¶ This unrecorded library catalogue chronicles the sale of the books of a largely little-known country parson. As such, it nicely reflects the reading or at least collecting tastes of literate and once-important local figures whose profiles dwindled posthumously to near anonymity, but who, through their acquisitive habits, contributed to the preservation and shaping of the wider culture and the formation of our collective memory.

THE BIBLIOPHILE

Thomas Wright was born circa 1775, the eldest son of Thomas Wright, a London merchant. As so often for the period, his mother’s name is not recorded. He was educated St. Paul’s School, London before matriculating at Pembroke College, Cambridge in 1794 (B.A. 1798; M.A. 1801). He was ordained deacon in 1798 (London), subsequently becoming rector of Otton Belchamp, Essex (1807-11), and of Little Henny (1811-20) before attaining the living as vicar of Middle and East Claydon, Buckinghamshire in 1820 until his death in 1841. Venn notes that he was the “Father of Thomas (1827)”. There are several possible matches for his marriage, but we have been unable to confirm the name of his wife or the date of their marriage with any degree of certainty. What we do know is that she predeceased him, since he requests in his will that he be “buried in the same grave as my beloved wife at Steeple Clayton”.

SEVEN

THE BOOKS

His books, however, seem to have left more of a trace in the “valuable and carefully selected library of upwards of 1,200 volumes” which lists 414 lots. The majority are individually lotted books, which usually include author’s name, title, date and very brief details (“Dryden’s Juvenal, 1713”, “Donne’s ditto [i.e. ‘LXXX Sermons’], folio, 1640”), while some lower-value items are grouped into titles of two or three (e.g. “27 Levizac’s French Grammar, hf. bd., Clef de Levizac’s 2 copies, and Boyer’s Dictionary, bd.”), and others of apparently nominal value do not justify naming (“School books”, “Ditto”).

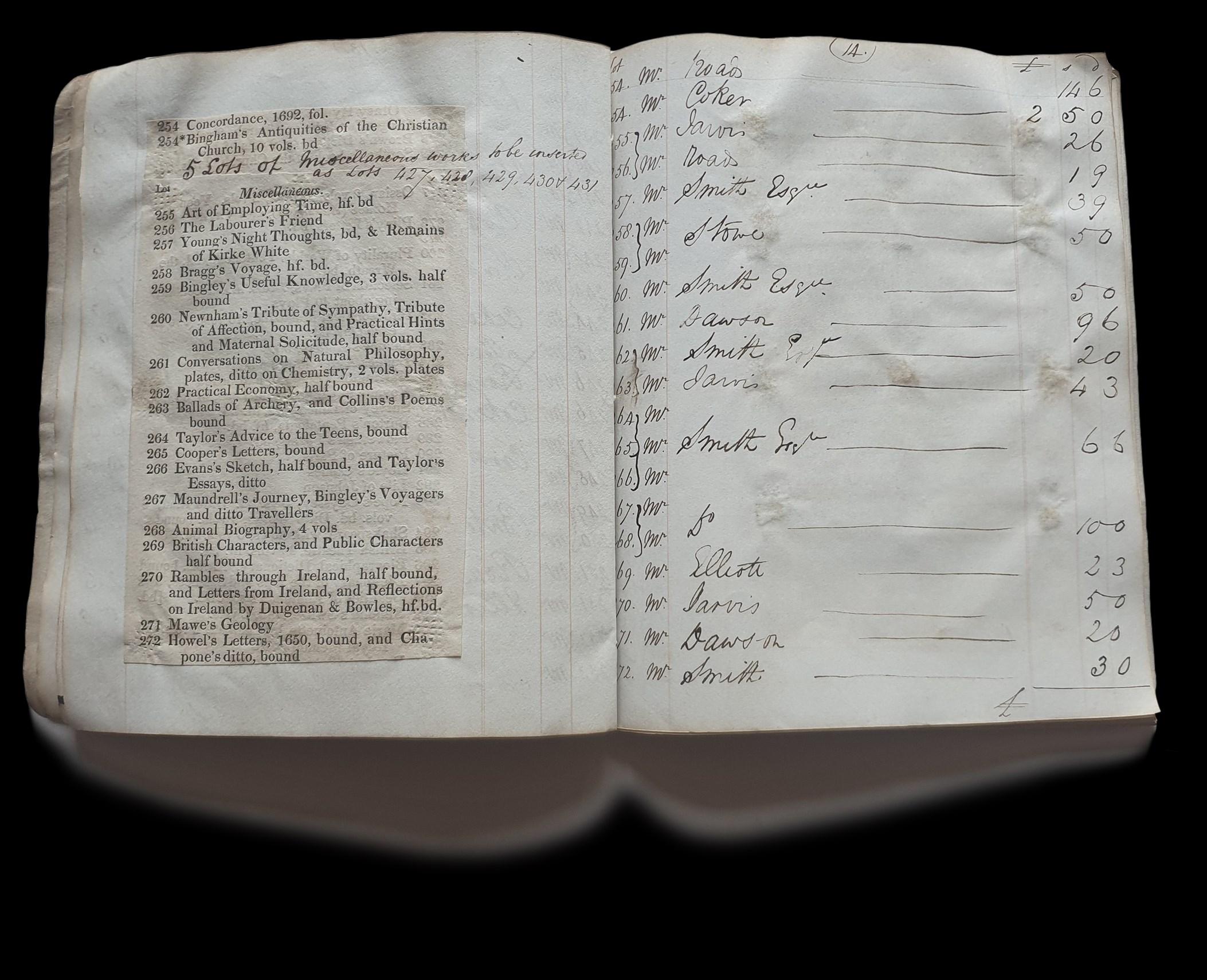

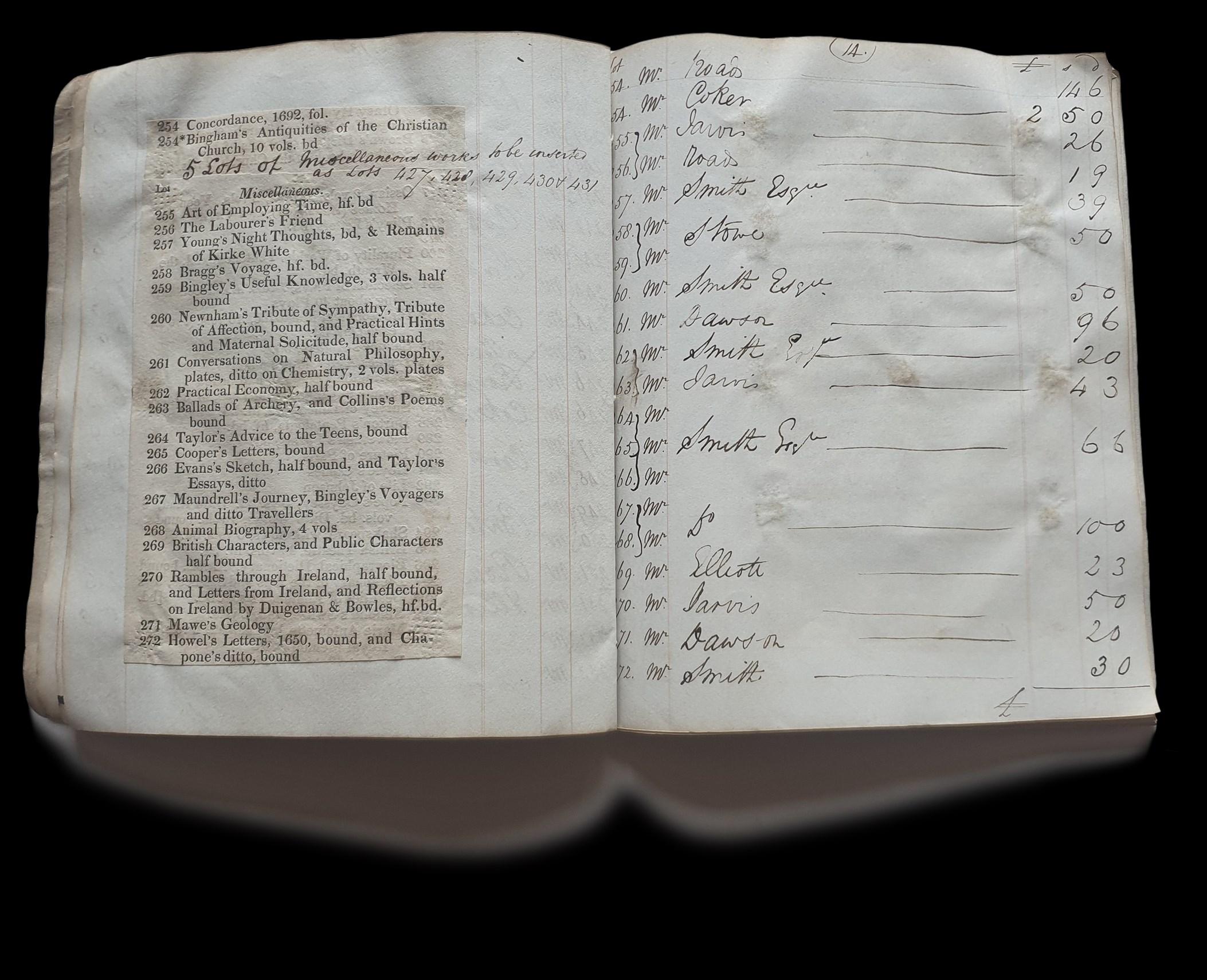

The collection has been grouped into nine categories arranged in the following order: “Novels, Books for Children, &c.” (125); “Works in Modern Languages Grammars, &c.” (26-43, plus one added in manuscript: “*43 Cobbetts Grammar”); “Works on Gardening, Botany, &c” (44-50); “Classics, School Books, &c” (51-104, although 54 is recorded as “no lot”); “Hebrew Works” (105); “Works on Law” (106-121); “Works on Divinity, Sermons, &c” (122-254*, this latter and six others extra lots are marked with an * or added in manuscript);

“Miscellaneous” (255 410); and “Odd Volumes or Imperfect Books” (411-414). The numbering is continued in manuscript to 431. These sundry lots include “Odd Books” (415-6), and five lots (427-31) of “Miscellaneous books” which were all bought by a “Mr Road” for “1.3.0”, and the others (417 -26) are left blank.

As the above list indicates, pride of place is given to novels and children’s books, although it is not certain that this reflects a value judgment by the auctioneer: of these first 25 lots, several are bundled up together (e.g. Lina, 2 vols. hf. bd. & Almoran and Hamet, bd.”, “11 More’s Tales, bd. Depping’s Entertainments hf. bd. Frend’s Evening Entertainments and Evening Amusements, hf. bd.” simply with “Ditto”. Books which warrant a single-entry name include “6 Rasselas and Dinarbas, bd”, “Shelton’s Don Quixote, 4 vols”, and “17 Gil Blas, translated by Smollett, 4 vols. bd.”

Wright kept several books on languages including Welsh, Italian, and French. The last of these is reflected in some of his books, but to judge from his collection, he preferred works in Latin or English.

Unsurprisingly for a man of the cloth, there are many theological books. These range from influential 17thcentury works like “Pearson on the Creed” in “2 vols. hf. bd”, “Butler’s Analogy” and “Taylor’s Holy Living and Dying, bd., and Pilgrim’s Progress, bd” (these latter lotted together), and important works from the 18 Theology” and “Wilberforce’s View”, through to contemporary authors such as Hannah More (here represented by “on St. Paul”, “Christian Morals”, “Moral Sketches”, and “Bible Rhymes”).

The “Miscellaneous” books encompass works of literature (including “293 Pope’s Odyssey, 5vs. bd. Ditto Iliad, 6 vols. bd. Ditto Works, 9 vols bound”, “294 Shakespeare, with notes, 8 vols. bd.”, and “329 Works of Rabelais, 1694”), travel books (“267 Maundrell’s Journey, Bingley’s Voyagers and ditto Travellers”, “283 Salame’s Algiers, bd”, “”286 Voyage to China, by M’Leod, hf. bd”), and scientific works (280 Plurality of Worlds, Fontenelle”, “325 Treatise in the Globes, 1639”, “358 Lavoisier’s Chemistry”). And Wright would have taken his place in the pantheon of the great and good recorded in “327 Graduati Canatbridgienses ab anno 1639 ad 1824”.

THE AUCTIONEER

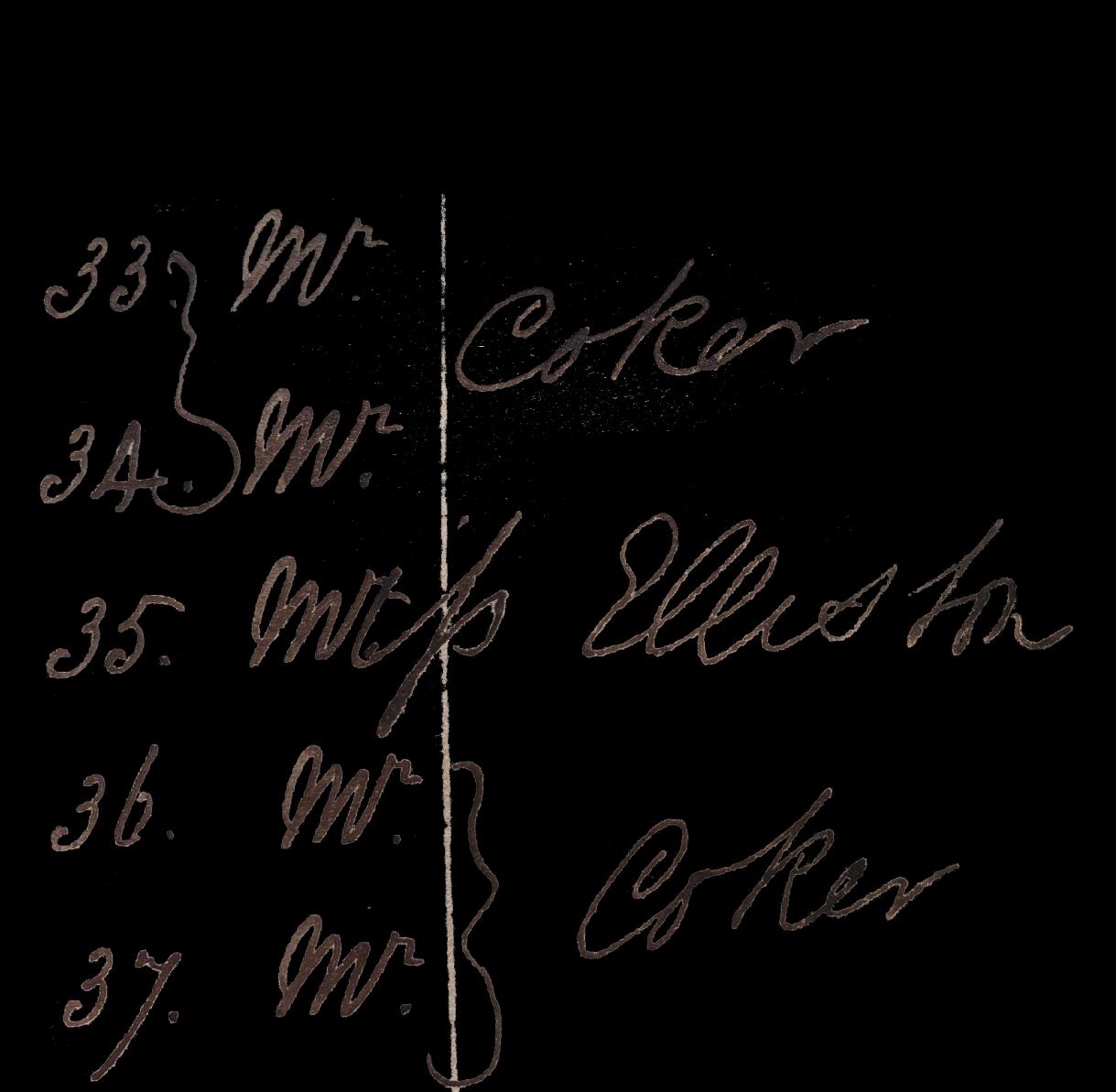

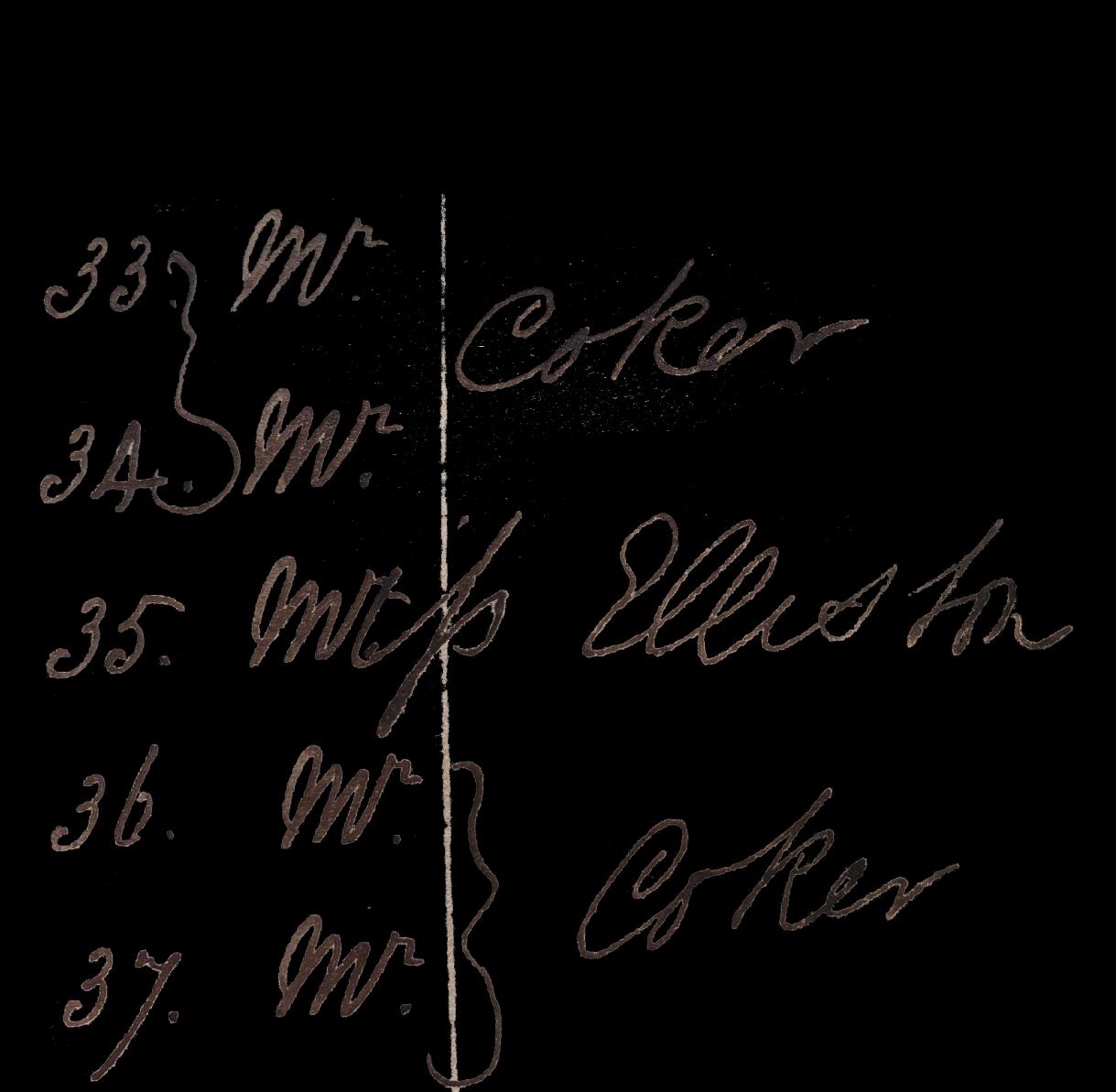

We are confident that this was the auctioneer’s retained copy. As noted in the physical details above, it was collaged together from at least two printed copies of the catalogue and then mounted into a book to allow the scribe to record in manuscript the buyer’s names, the prices paid, and several other crucial details. These include manuscript notes such as “5 Lots of Miscellaneous works to be inserted as Lots 427, 428, 429, 430 & 431” – and the ‘clincher’ is the record of several instances of the buyer having settled their invoice (several lots are marked “Paid” or “Pd” next to the purchaser’s name).

Jonas Paxton was an auctioneer based in Bicester, Buckinghamshire. From this rural market town, he held sales of farms and farmland as well as household dwellings and contents. The earliest record of his name as an auctioneer was in 1838, with the announcement in Jackson’s , of a sale to be held in Bicester. However, the earliest record for Paxton in library holdings is a catalogue for a sale held in 1849 (Particulars & conditions of sale of freehold and copyhold estates at Blackthorn and Fritwell in the County of Oxford). His son appears to have joined the firm around 1854, and Paxton senior sometimes worked in partnership with George Castle (library holdings record various combinations of Jonas, his son, and Castle). The early catalogues were often printed by “E. Smith and Son, printers and booksellers”.

As noted above, the earliest library holding for a Paxton sale catalogue is 1849. Although he travelled as far as Cambridgeshire on occasion, all his other sales were for land, dwellings, or house contents; this sale, therefore, not only marks his earliest recorded sale catalogue, but suggests a remarkably intrepid debut, involving as it did the taking on and cataloguing of a library as a stand-alone sale and conducting it in situ at Claydon Rectory.

THE BUYERS

The most voracious buyer was a “Mr Elliott”, who secured 107 lots – over a quarter of the total sale. Given the sheer quantity and range of his purchasing, we would assume he was a dealer. “Mr Rowsell” picked up 36 lots (again wide-ranging), and several buyers bought in the high teens to early twenties. A cluster of bidders secured around a dozen lots each, including a “Mr Child” who bought John Donne’s sermons for “7s”, along with several other books. After that, the purchases tail off into small amounts or even single books. Whether they were unsuccessful or highly focused in their buying is difficult to say at this distance, but a few are certainly worth drawing attention to. Paxton himself appears to have bought lot 17, “Gil Blas, translated by Smollett, 4 vols. Bd.”, for “3s” .

Paxton’s close colleague “Smith Printer” bought nine lots, including “297 Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, 8vs” for “15s” as well as Hind’s Arithmetic, Moore’s Juvenal, Edinburgh Dispensatory (342-344), and several others, so was perhaps selling books from his premises in Bicester as well as printing, among other things, Paxton’s sale catalogues. The scribe has prewritten “Mr” before each entry, but lot 35 (“Italian Pocket Dictionary and Zotti’s Italian Grammar”) has been amended to “Miss” followed by “Elliston” who paid “4s 6d” – an unusual, early record of a woman purchasing at auction.

The 1,200-plus volumes recorded in this sale catalogue offer a window onto the rich cultural and literary landscape of a rural clergyman in the early 19th century. Wright’s vocation may (or may not) have secured him eternal glory, but in the temporal realm, it was his passion for books that has left the clearest traces of his earthly existence.

£2,650 Ref: 8152

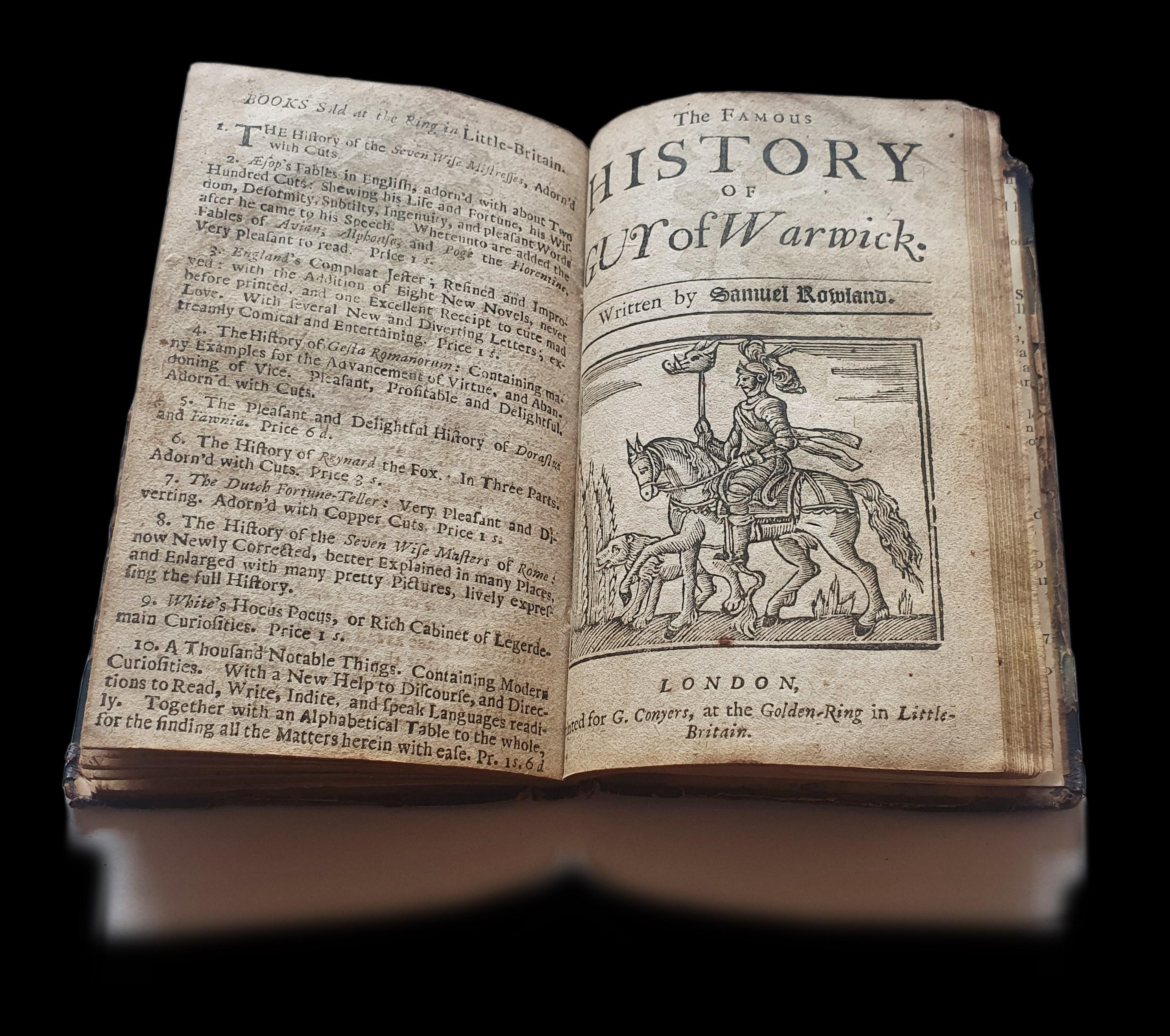

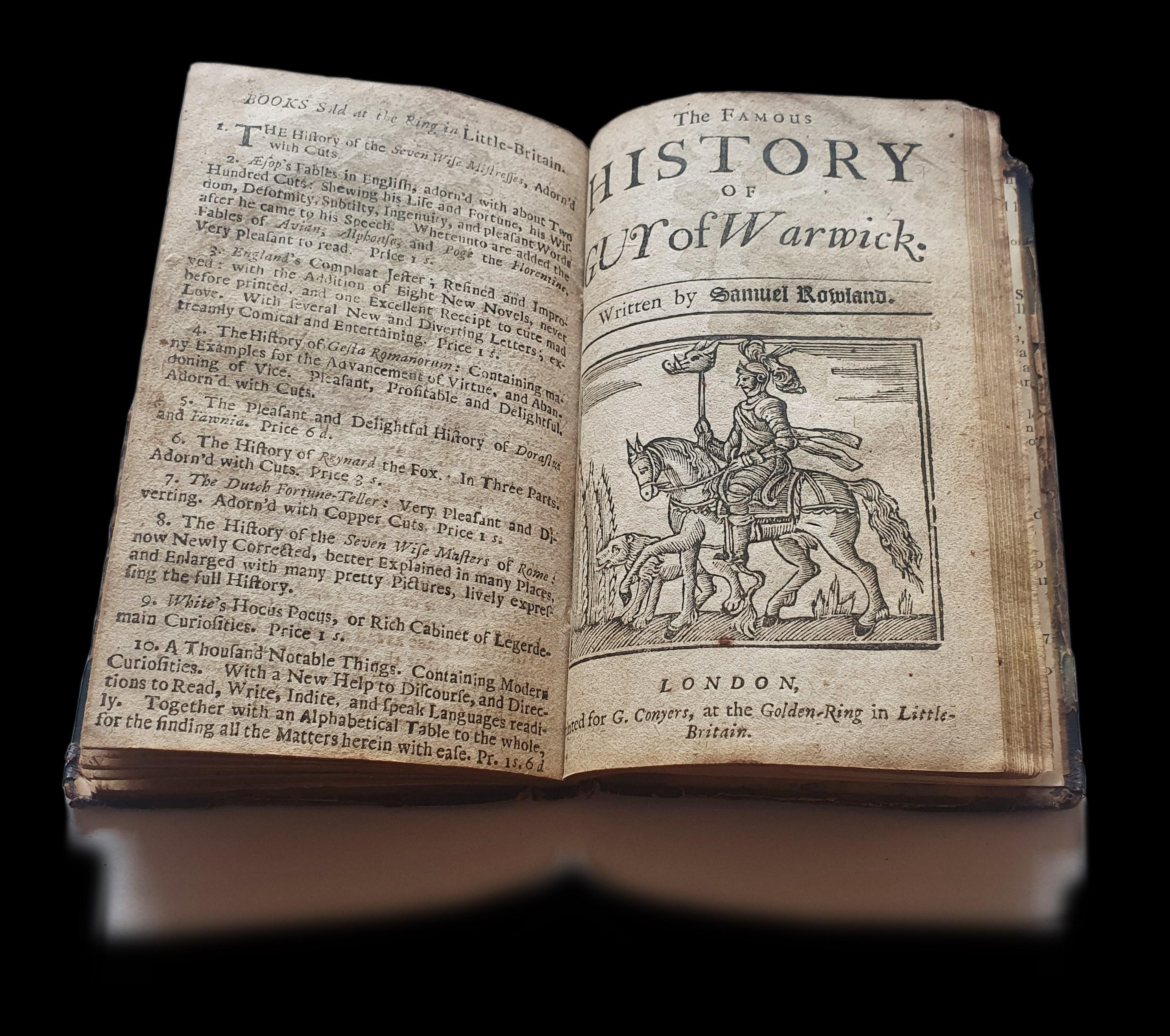

ROWLANDS, Samuel (1570?-1630?). Two editions of ‘The Famous History of Guy Earl of Warwick. Written by Samuel Rowland’

London: printed for G. Conyers, at the Gold-Ring in Little-Britain, [1680?];

London: printed for G. Conyers, at the Golden-Ring in Little-Britain, [1701?].

Octavo. Pagination 79, [1, adverts] (woodcut vignette to title page and 8 woodcuts in text); 30, [2, adverts] (woodcut vignette to title page and 7 woodcut vignettes in text). [ESTC, R218418 and T184950]. ESTC note to the latter: “NUC suggests [1690?].

G.Conyers active 1686-1712.” However, the advertisements include 19 books, some of which do not appear to be listed in ESTC, but those that do date to circa 1700-5 which supports the slightly later date.

18th-century half calf, marbled boards, rubbed and worn but sound. Title page to the 1680 edition torn at fore-edge with loss of a triangular section approximately 50 mm vertically diminishing to 25 mm into the woodcut image and a small hole (10 x 5 mm)to the upper section of the woodcut.

Provenance: inscription to verso of the 1701 edition: “Richd Paly his Book Stall not this Book for ffeear of Shame Over this there is my Name Mdcclviii”. The woodcut image has been crudely copied through in ink wash, probably by Paly. Ownership bland-stamp to first text leaf of Francis Henry Cripps-Day (1864-c.1945), antiquary, lawyer, and author of books on armour and pageantry.

Page from an old bookseller’s catalogue pasted to rear endpaper with address at its head: “66. Great Russell St., London, W.C. 1 Facing the British Museum” – probably that of James Tregaskis, who was, according to the British Museum website, a “Major London book dealer (1850-1926)” who “worked as printer in London until 1889 when he went to work in the bookshop of his wife, Mary Lee Bennett (1854?-1900) at 232 High Holborn, or “Caxton Head”, which became ‘J & M.L. Tregaskis’. In 1915 the Caxton Head moved to Great Russell St. […] His son from his second marriage to Eveline Belwood Davis (1877-1948), Hugh Frederick Beresford (1905-1983) helped run the firm with his father and it became ‘James Tregaskis & Son’”.

The catalogue clipping includes a reference to the similarly titled The heroick history of Guy Earl of Warwick. Written by Humphrey Crouch. ESTC records four editions of that work and observes that “The woodcuts are the same as those used in the 1635 edition of “The famous historie of Guy earle of Warwick” by Samuel Rowlands (a different work)”.

All editions are extremely rare: ESTC records 16 between 1609 and 1701, mostly only one or two copies of each (the two exceptions being the 1667 and 1689 editions which are represented by three copies each). Indeed, the two editions bound together here are no exception: ESTC locates 2 copies of the 1680 edition (British Library and Columbia University) and 2 of the 1701 edition (National Library of Scotland and the Bodleian).

¶ Two extremely rare editions of Rowlands’ poem The Famous History of Guy Earl of Warwick are here bound in one volume – a curious choice with no evident motivation. This was one of many renditions of the Guy of Warwick legend, so rooted in English folklore that the figure of Colbrand the giant, whom Guy slays in the narrative, is mentioned in two of Shakespeare’s plays (Henry VIII and King John).

EIGHT

The poem is also a notable sidenote to the vogue for ‘Turk plays’ largely launched by Christopher Marlowe’s Tamburlaine – a wave of dramatic renditions that included the anonymous The Tragical History, Admirable Atchievments and various events of Guy earl of Warwick. In these works, as in Rowlands’ verse retelling of the legend, as Annaliese Connolly remarks, “English conceptions of Anglo-Ottoman relations in the sixteenth century are superimposed on the medieval depiction of English or European crusaders and their Saracen enemies”

Samuel Rowlands was chiefly known as a satirist, and his earliest work in this vein became a succès de scandale after copies of his first two satires were publicly burned. He also published a handful of pious works, including The betraying of Christ (1598) (described by ODNB as “a somewhat sententious biblical paraphrase”); and The Famous History which was entered in the Stationer’s Register in 1608 and went through a number of editions during the 17 century, all of which are rare.

£2,750 Ref: 8149

1.‘Guy of Warwick, Godfrey of Bouillon, and Elizabethan Repertory’, Early Theatre. Vol. 12, No. 2 (2009), pp. 207

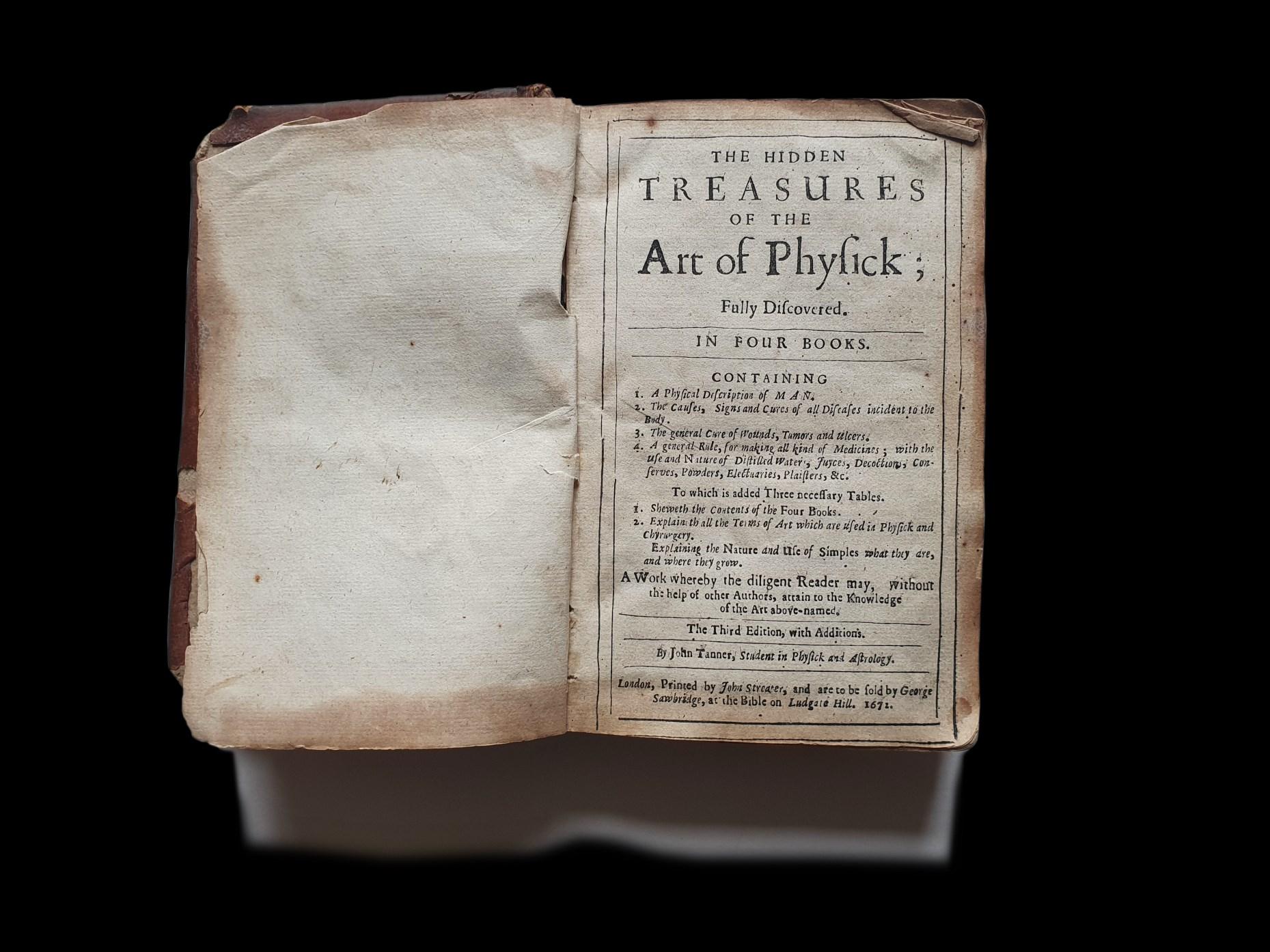

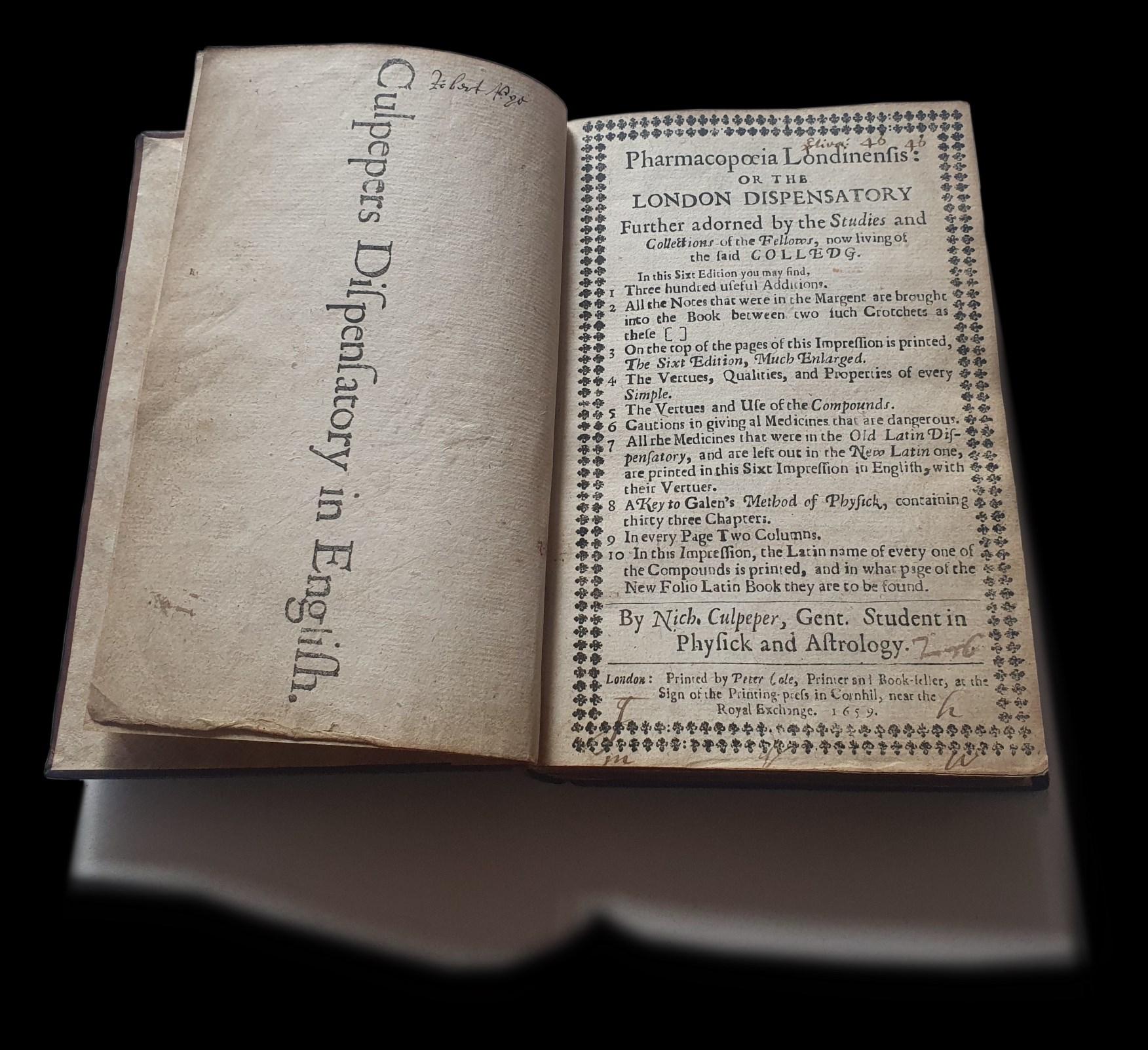

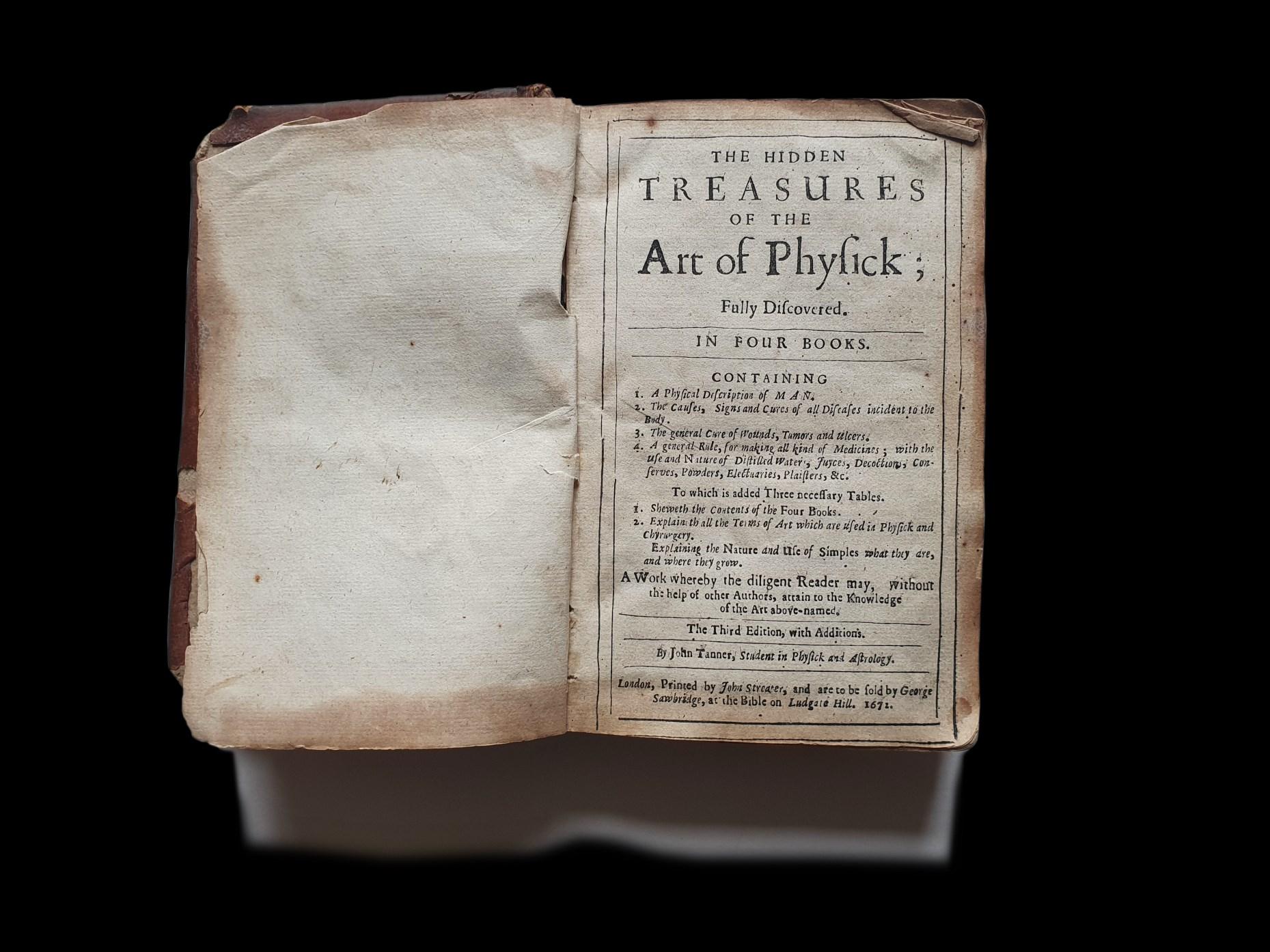

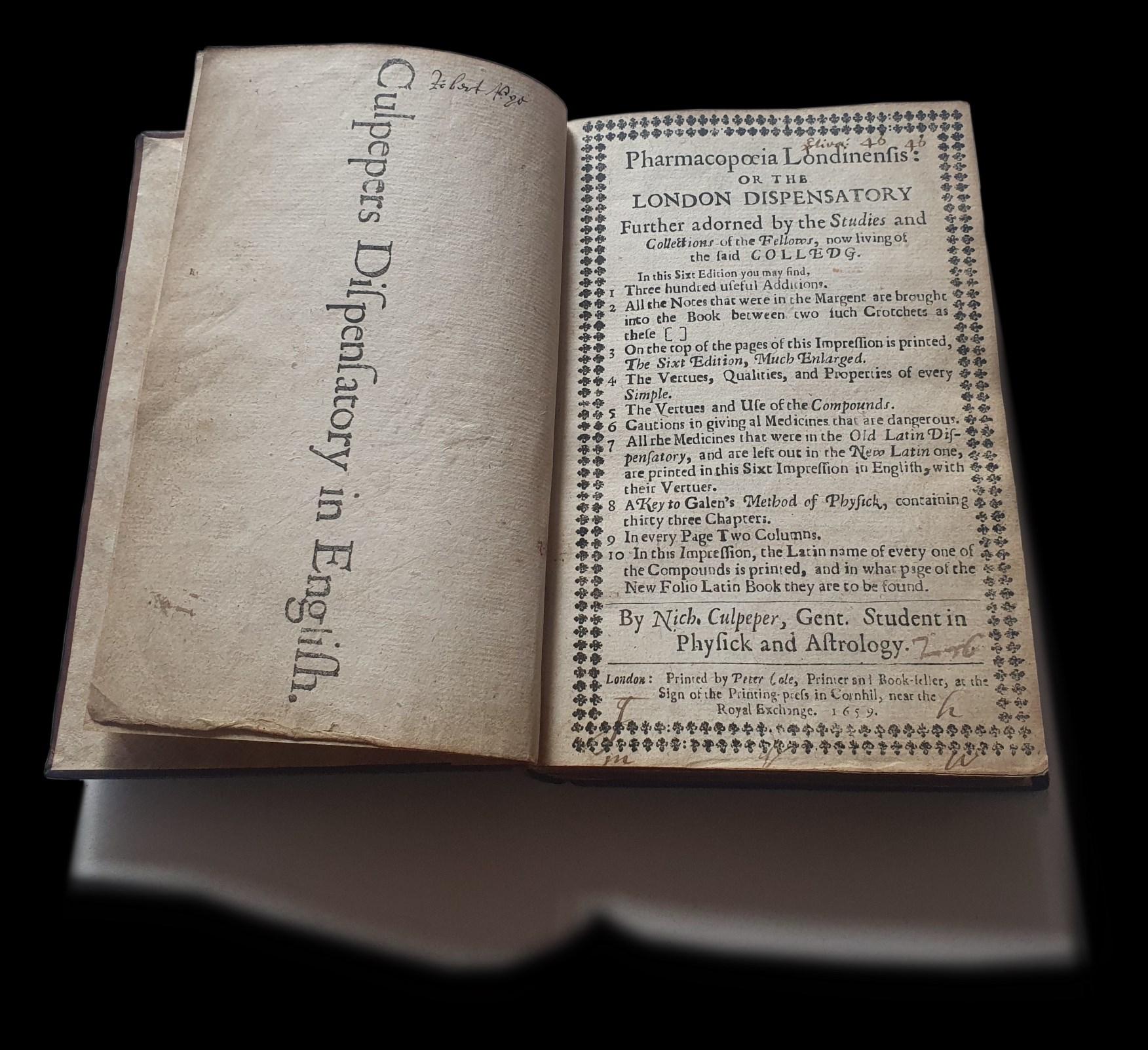

TANNER, John (approximately 1636-1715) The hidden treasures of the art of physick; fully discovered. In four books. Containing 1. A physical description of man. 2. The causes, signs and cures of all diseases incident to the body. 3. The general cure of wounds, tumors and ulcers. 4. A general rule, for making all kind of medicines; with the use and nature of distilled waters, juyces, decoctions, conserves, powders, electuaries, plaisters, &c. To which is added three necessary tables. 1. Sheweth the contents of the four books. 2. Explaineth all the terms of art which are used in physick and chyrurgery. Explaining the nature and use of simples what they are, and where they grow. A work whereby the diligent reader may, without the help of other authors, attain to the knowledge of the art above-named. The third edition, with additions. By John Tanner, student in physick and astrology.

London: printed by John Streater, and are to be sold by George Sawbridge, at the Bible on Ludgate-Hill, 1672. Octavo. Pagination [14], 324, [22] p. first leaf is blank. [Wing, T137A; Heirs of Hippocrates, 601]. Contemporary sheep, rubbed and worn with loss to corners, spine chipped.

¶ This is an early example of the production of medical texts for a popular readership. John Tanner, who held a licence from the College of Physicians and practiced in London in the mid-to-late17th century, first published this volume in 1656 (subsequent editions in 1659, 1667, and 1672), with a preface in which he describes how he “collected, out of the Works of most of the Ancient and Modern Physitians now extant among us, this Compendium or Abridgment of Physick”. The majority of the contents, he assures the reader, are “confirmed by the Probatum est of my own Experience”, and are intended not as “competition with the Works of so many more grave and Learned Rabbies; but for the good of those that want such helps, and are unacquainted with the Latine Tongue” – these including “industrious Students”, “People void of Learning, and of mean Capacities”, and “Ladies and Gentlewomen who are wont to tend to their poor

Tanner begins with “A Physical Description of down of human anatomy, before launching into the panoply of diseases affecting it. He then turns to the treatment of wounds, tumours, ulcers and fractures, and concludes with “The Faculty and Natural Operation of most of the Compound Medicines now in use amongst us […] together with a general Rule for the making of all such kind of Medicines”. Fittingly for a popular text, Tanner includes a glossary and a table of simples to aid the finding and using of medicinal plants.

£500 Ref: 8100

NINE

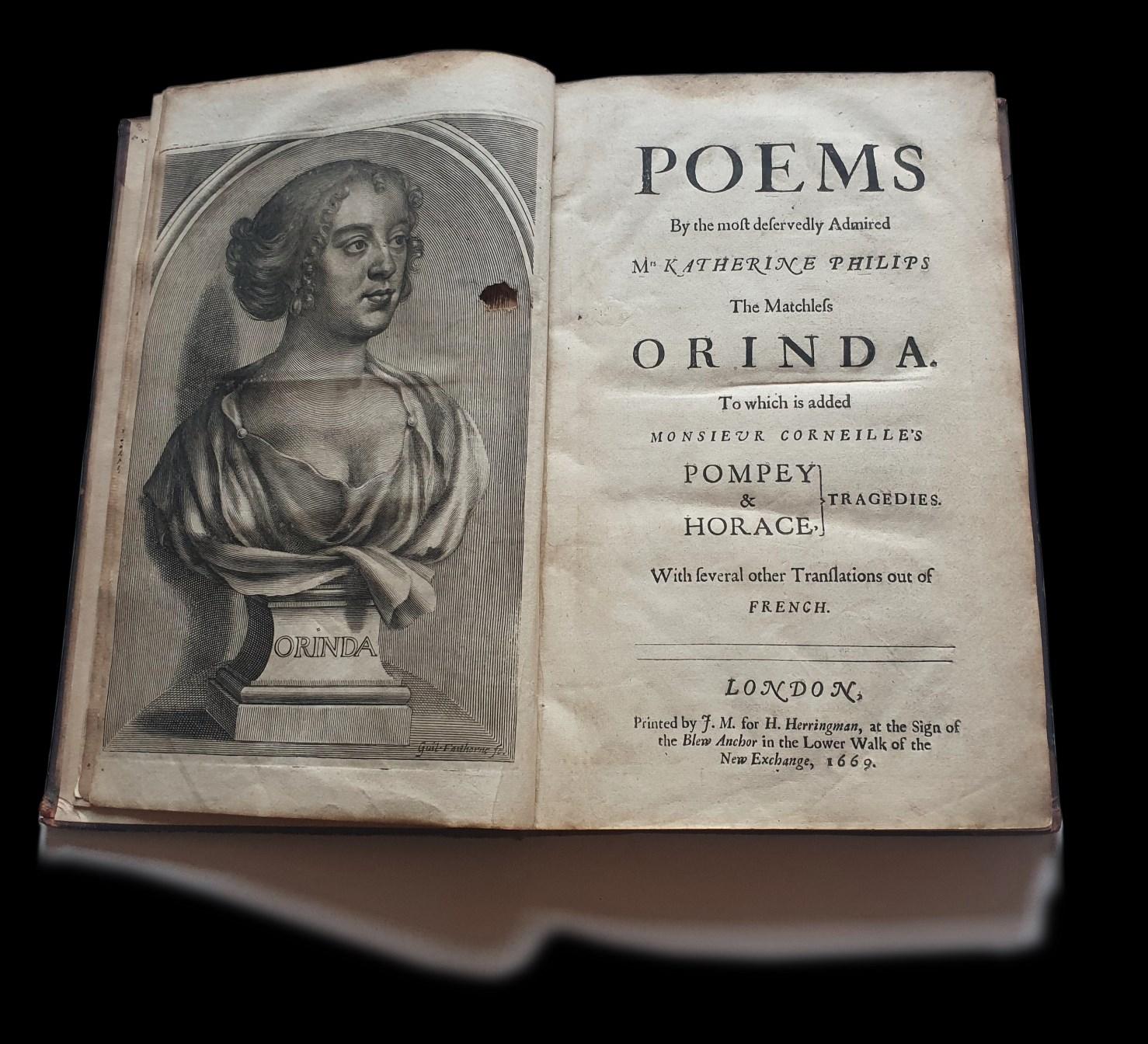

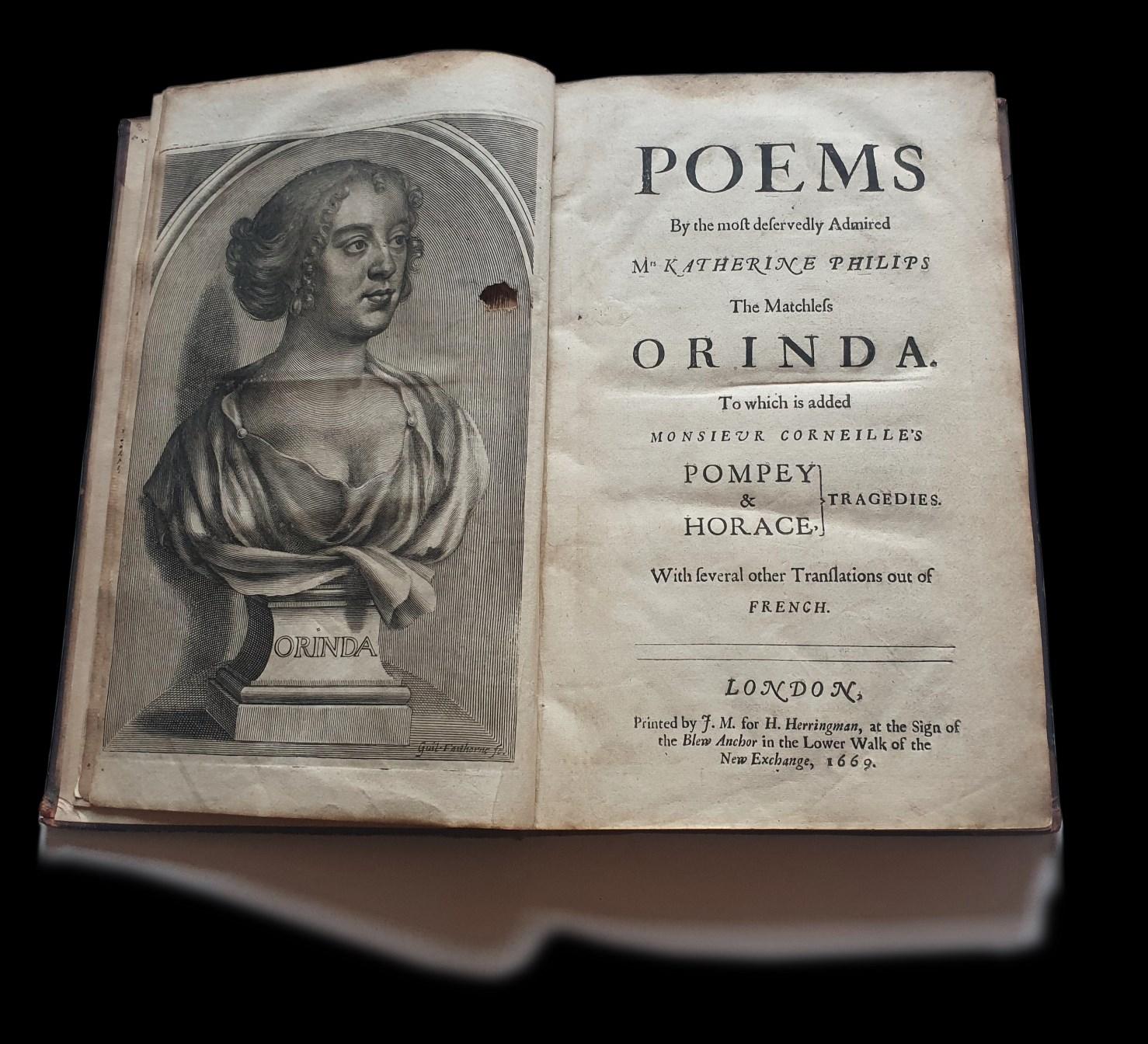

PHILIPS, Katherine (1631-1664) Poems by the most deservedly admired Mrs Katherine Philips the matchless Orinda. To which is added Monsieur Corneille’s Pompey & Horace, tragedies. With several other translations out of French. London: printed by J[ohn]. M[acock]. for H. Herringman, at the sign of the Blew Anchor in the lower walk of the New Exchange, 1669. Second edition. Folio. [36], 198, [8], 124, [2] p. : port. [Wing, P2034]. engraved portrait frontispiece, small hole, C1-2 & E1-2 with marginal hole just touching affecting odd letter, previous owner's late 18th/early 19th century copious manuscript notes in an academic hand to early blanks, one or two notes in margins, scattered spotting, occasional marginal staining, contemporary calf.

¶ Katherine Philips was one the most celebrated poets of the 17th century and a contemporary of Aphra Behn, Margaret Cavendish and other women writers and poets who flourished after the English Civil War. Born into a largely puritan family but developing royalist sympathies for a time, she married James Philips (c.1624-1674), a supporter of parliament who served as MP under both Cromwell and Charles II; some of her poetry shows her navigating the tricky terrain between their contrasting (albeit both moderate) political outlooks, sometimes defending her husband against his critics and distinguishing “her own ‘follies’ and ‘errours’ in loyalty to the dead monarch [Charles I] from her husband's views” (ODNB).

Philips is perhaps best known for her poems celebrating friendship – an interest she also pursued by establishing a close literary circle of associates, to whom she assigned coterie names (she herself famously took the name ‘Orinda’). Her reputation has survived into the 21st century, with renewed interest thanks to feminist scholarship.

This is the second edition of a posthumous collection first published in 1667, which, along with her poetry and translations, included fulsome tributes (“the honour of her Sex, the emulation of ours, and the admiration of both”) that nevertheless betrayed the patronising tone characteristic of the age: her close friend and frequent correspondent Charles Cotterell (whom she gave the coterie name ‘Poliarchus’) wrote of her poems that “there are none that may not pass with favour, when it is remembered that they fell hastily from the pen but of a Woman”.

£1,500 Ref: 8120

TEN

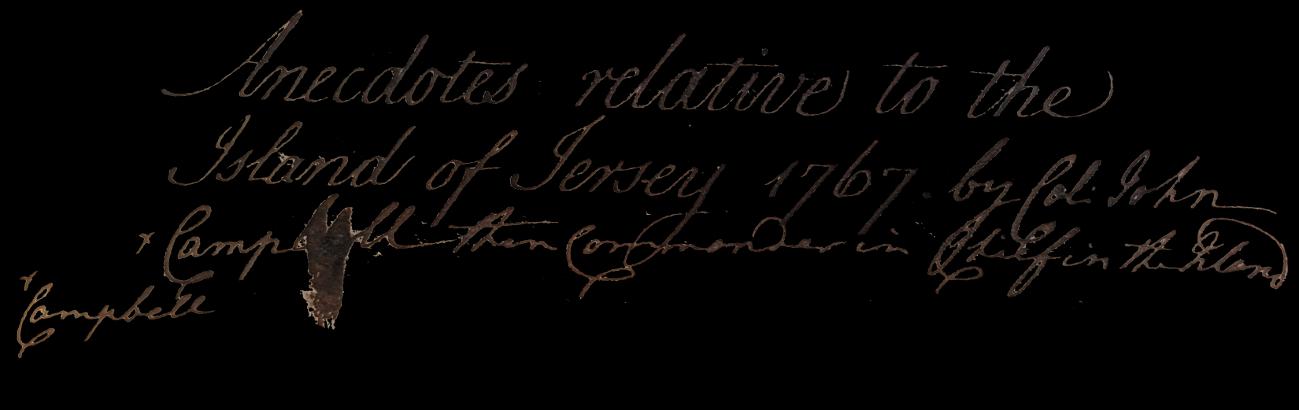

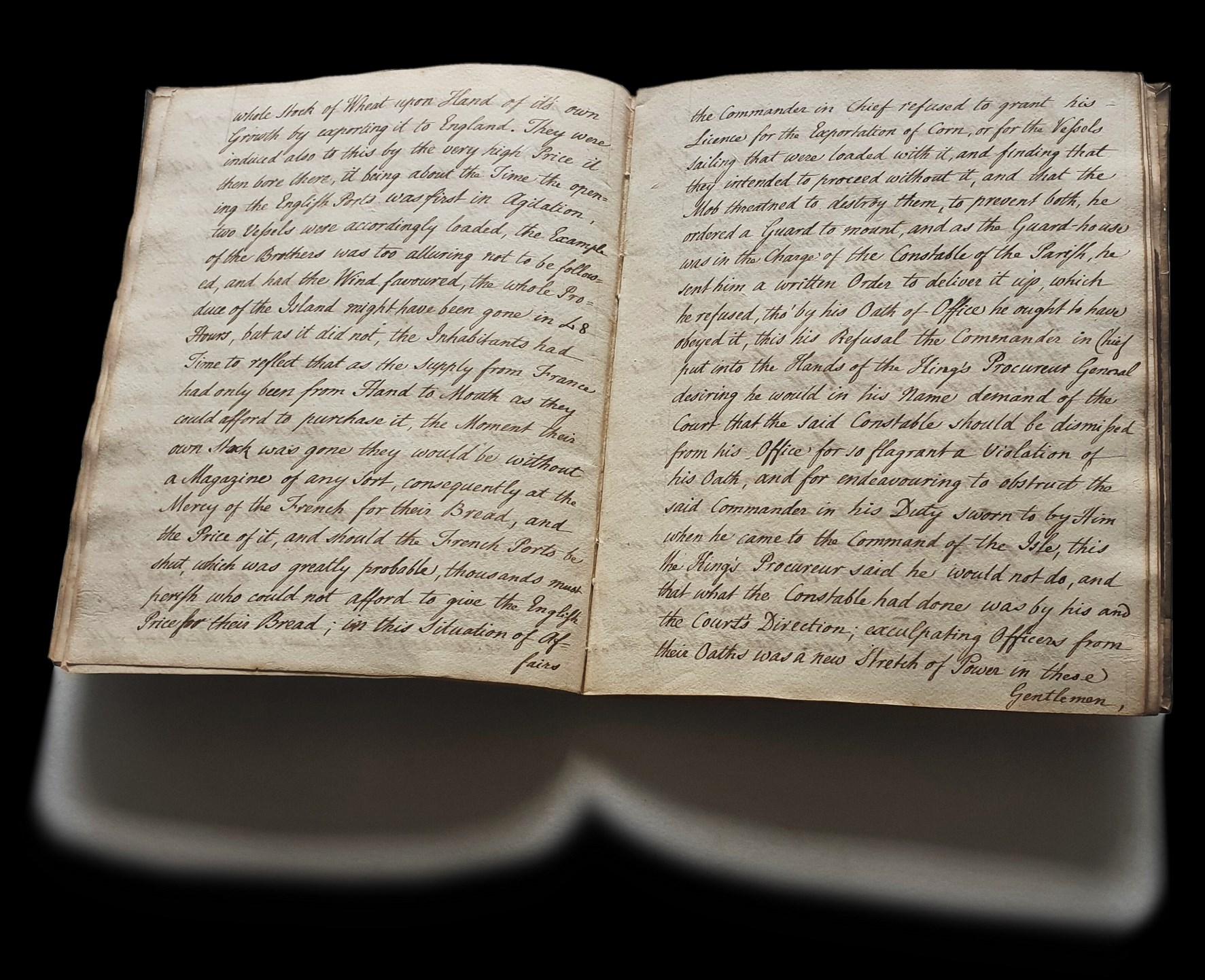

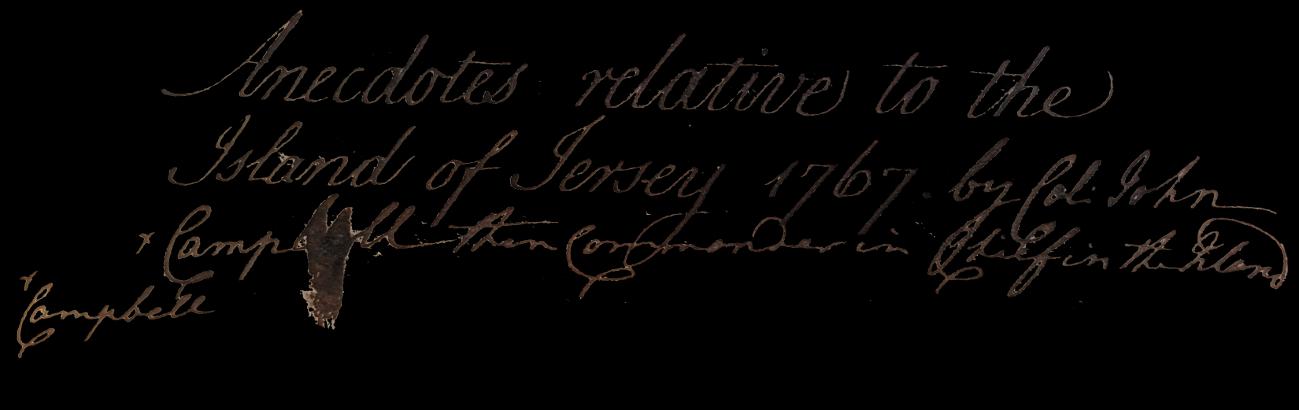

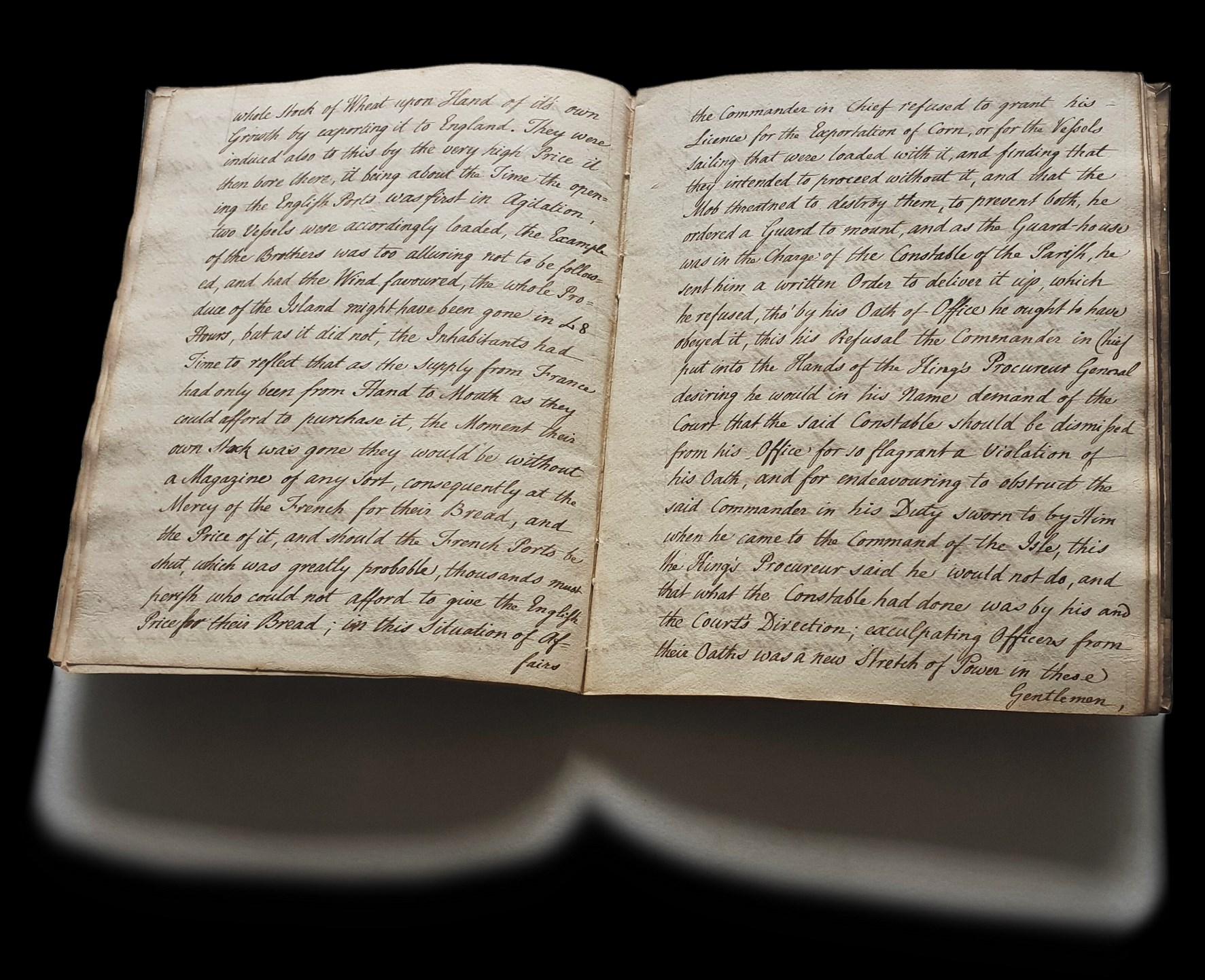

[CAMPBELL, John]. Manuscript entitled ‘Anecdotes relative to the Island of Jersey 1767’ and early ciphering book.

[Jersey. Circa 1770-79]. Quarto (195 x 160 x 12 mm). Dos-a-dos. Foliation Island of Jersey: [1, title and blank], 28 leaves (55 text pages); [Ciphering book]: 23 (several leaves excised, 39 pages of calculation and text). The two sections are separated by five blank leaves. Contemporary limp vellum, several slash marks to covers, amateur repairs (brown paper stuck to paste-down), horizontal cut to first three leaves of the ciphering section, neatly repaired.

¶ The Corn Riots of 1769 were a watershed moment in the history of Jersey, prompting a loosening of the semi-feudal conditions under which the Lemprière family had held sway over the island. Charles Lemprière and his brother Philippe had a monopoly of the judicial and legislative arms of government – Charles as Lieutenant Bailiff, Philippe as Receiver-General. The protests were centred on the repeal of a law banning the export of grain, which was seen as a ruse to create scarcity and thus increase the price of wheat; many Jersey landowners – foremost among them the Lemprières – stood to gain since the rents from their tenants were payable in wheat.

The acts of resistance that followed included the raiding by local women of a ship loaded with corn for export and an enmasse disruption of a Court session in which the protesters laid out their demands. Among these demands were that the price of wheat be lowered, tithes be reduced, and a range of oppressive fines and seigneurial rights be abolished. The Lemprières took their case to the Privy Council, prompting an investigation and, ultimately, the appointment of Colonel Rudolph Bentinck as Lieutenant-Governor. The ban on exporting crops was reinstated, and a Code of Laws in 1771 divided judicial and legislative powers between the States of Jersey and the Royal Court, ending the Lemprières’ monopoly.

This manuscript is a copy by “Ph: Carteret. R.N / Trinity” (as inscribed to the front free endpaper) of an extremely rare, printed book, Anecdotes relative to the Island of Jersey 1767, which describes events leading up to the unrest of 1769. Whether Carteret copied the text from another manuscript or from the published book remains unsettled. It was published anonymously in Southampton in 1773 at Southampton, and ESTC records only one surviving copy, at the British Library (Citation No: T92621). Among this handwritten copy’s points of interest is Carteret’s attribution of the previously anonymous work to “Col: John Campbell then Commander in Chief in the Island”.

From reading the text we learn that as commander in chief John Campbell played an active role in proceedings and had first -hand knowledge of events. He would have been ideally placed to report on them as, unlike most of the participants, he does not appear to have had any vested interest in the outcome and could provide something like an objective eye on proceedings.

ELEVEN

Philip Carteret (1733-96), a naval officer and explorer, was probably somewhat less objective. During a forced hiatus from the navy as a result of some bruising disputes with the Admiralty over the dilapidated state of a ship he commanded, Carteret returned to his native Jersey in 1770 to succeed his father as the seigneur of Trinity, “joining the rebels against the Lemprière family’s hold over the island” (ODNB). But why might he have wanted to make a copy of Campbell’s book –and why write it in an old ciphering book rather than start with a new, blank volume?

A possible answer to both questions lies in Carteret’s own situation between 1770 and 1779 (the period during which we assume the manuscript was written, since he left Trinity to take up command of another ship in 1779). According to the ODNB, Carteret left the navy in 1770 “with his health ruined and with scant reward from the Admiralty”, and moreover “he was left on half pay.” Since Trinity is known to have played an active role in the rebellion against the Lemprières, he may have wanted to find confirmation of a belief he already held about the Lamprières’ grip on power; or he may simply have wished to study the document in order to understand the situation better. In any case, it is exactly the kind of political text that would have engaged a man who had himself lately suffered from the heavy hand of aggressive authority. As to his use of his old schoolboy ciphering book, simple impecunity may well account for this decision.

His handwritten, contemporary copy of a very rare printed book speaks to the degree of feeling he – in common with his fellow islanders have felt about the situation; and his attribution of the work to John Campbell, which we have no reason to doubt, rescues a firstperson account of the events concerned from anonymity.

£1,750 Ref: 7896

TWELVE

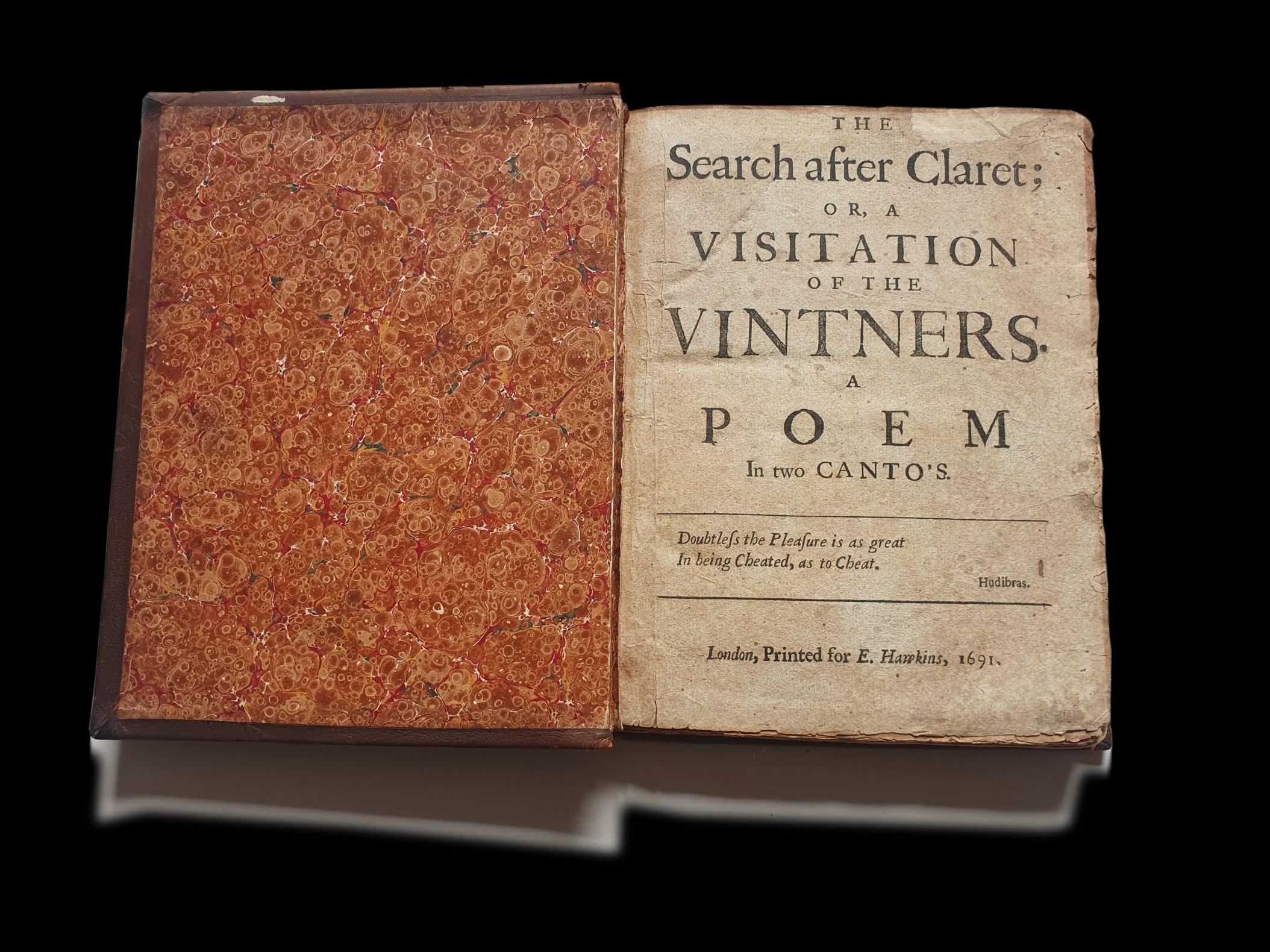

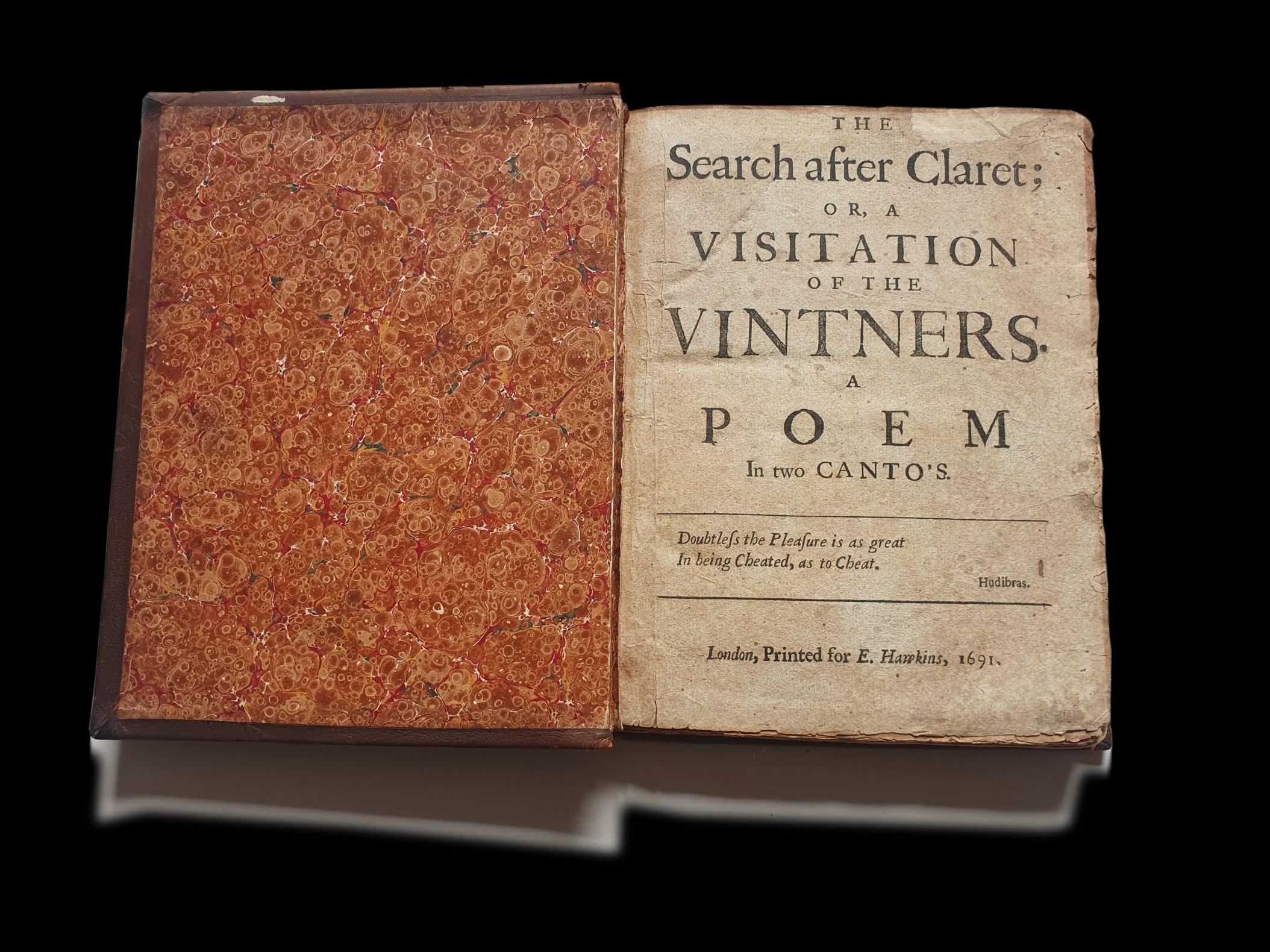

[RESTORATION SAMMELBAND] A collection of 12 rare 17th-century works, many relating to wine. London: 1690-91. Quarto. Later full sheep, rubbed and worn.

¶ This sammelband could almost be said to recreate the lively, argumentative atmosphere of a Restoration coffee house. It begins as a showcase for the work of the satirist Richard Ames (1664?-1692), whose comic poems included several on the subject of drinking and socializing: his Search after Claret sequence, contained here, laments “the declining quality of the claret served in London taverns” (ODNB), and elicited a parodic riposte, also featured here. But the collector of these works clearly had more than roistering on their mind: also included is the playwright Thomas D’Urfey’s political satire The Weesils a Satyrical Fable (concerning the furore over clergyman William Sherlock’s refusal to pledge an oath of allegiance to William and Mary), along with two works in response.

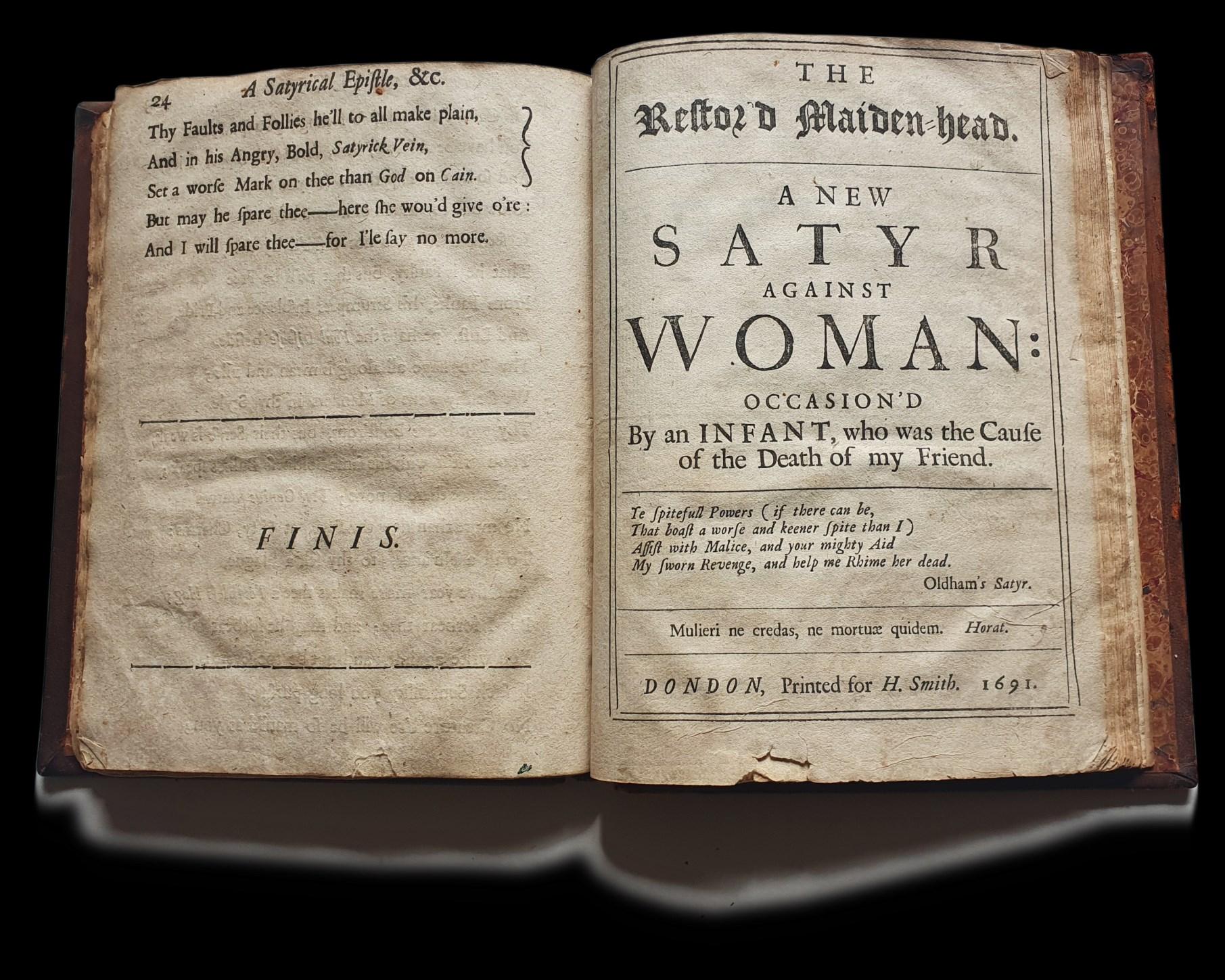

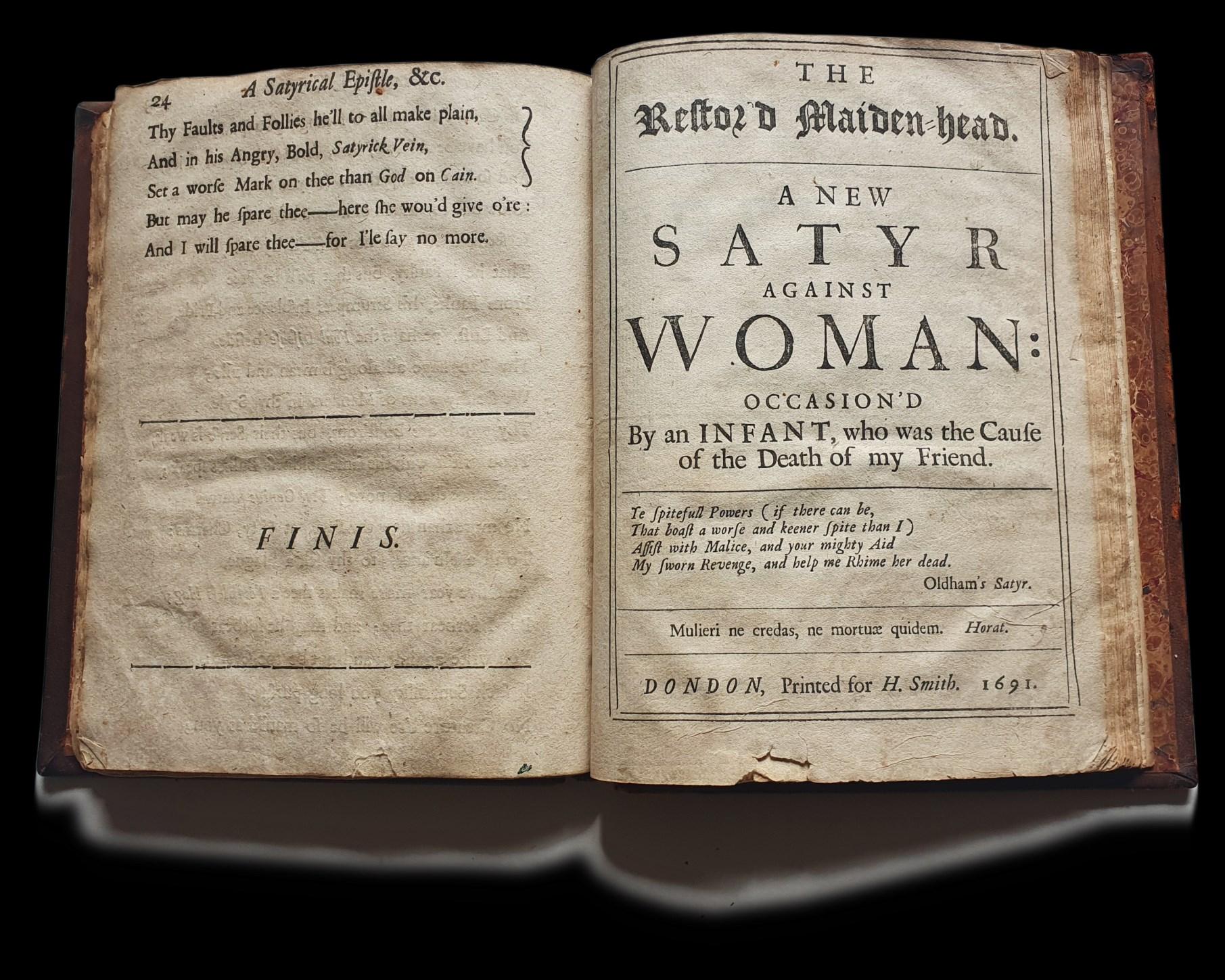

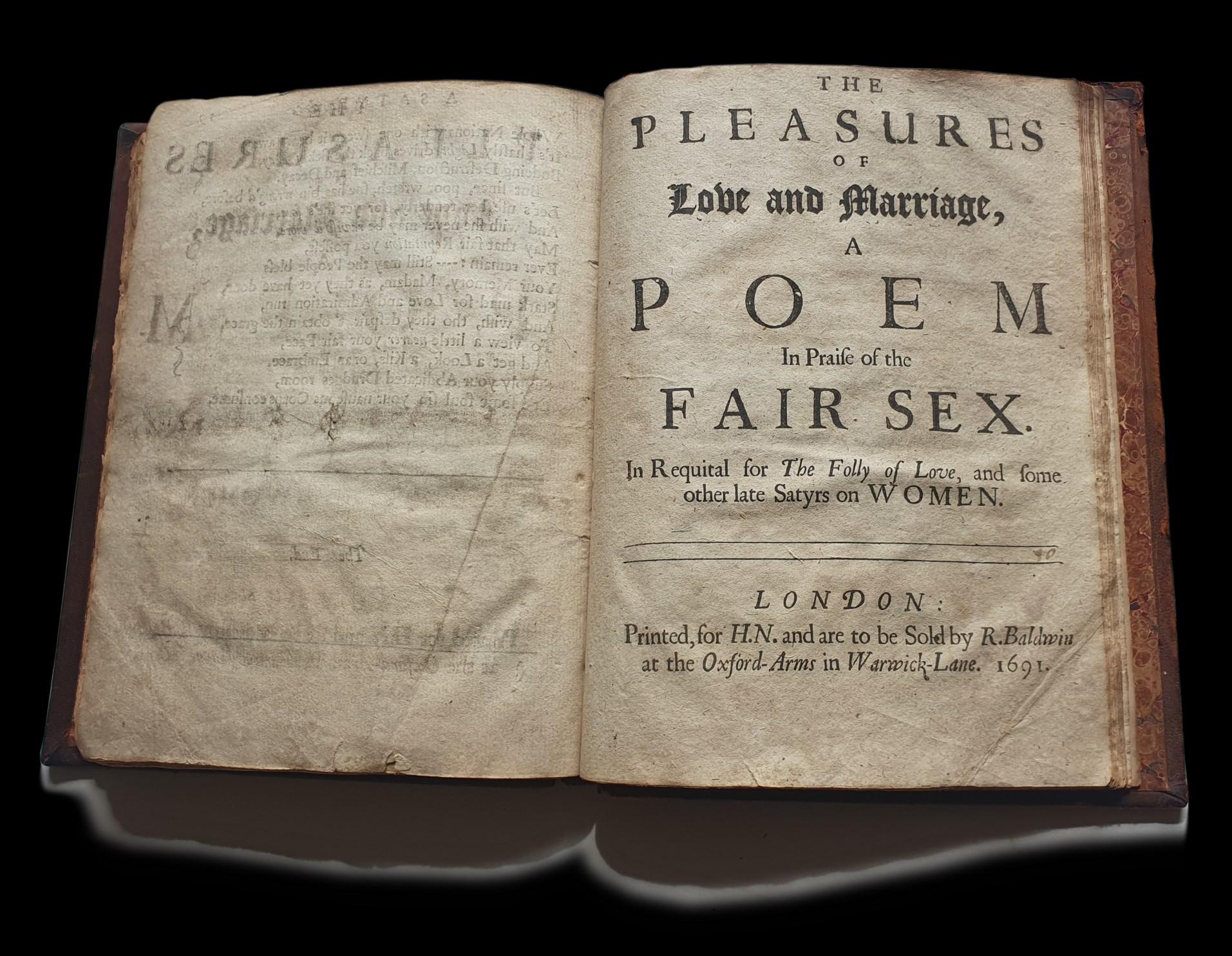

The sense of conversations and arguments raging within these covers is further amplified by the final three pamphlets. The first of these, Robert Gould’s A Satyrical Epistle to the Female Author of a Poem, call’d Silvia’s Revenge, &c. By the Author of the Satyr against Woman, is actually a riposte to a riposte, since Sylvia's Revenge, or, A Satyr Against Man (sadly not included here) was actually Richard Ames’ answer to one of Gould’s misogynist satires. The theme is continued with New Satyr Against Women and concludes with Ames’ more conciliatory

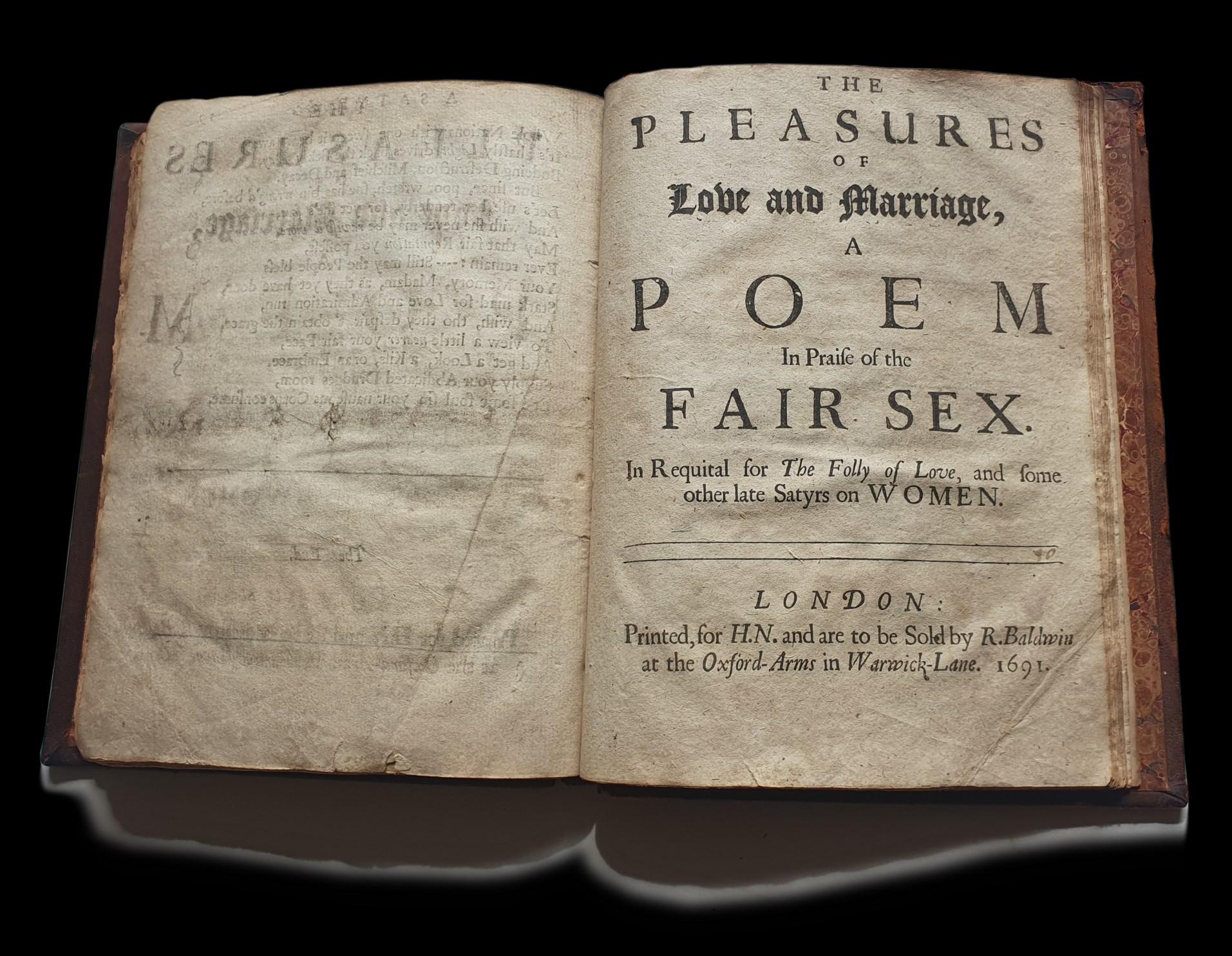

The Pleasures of Love and Marriage, a Poem in Praise of the Fair Sex. In requital for The folly of love, and some other late satyrs on women

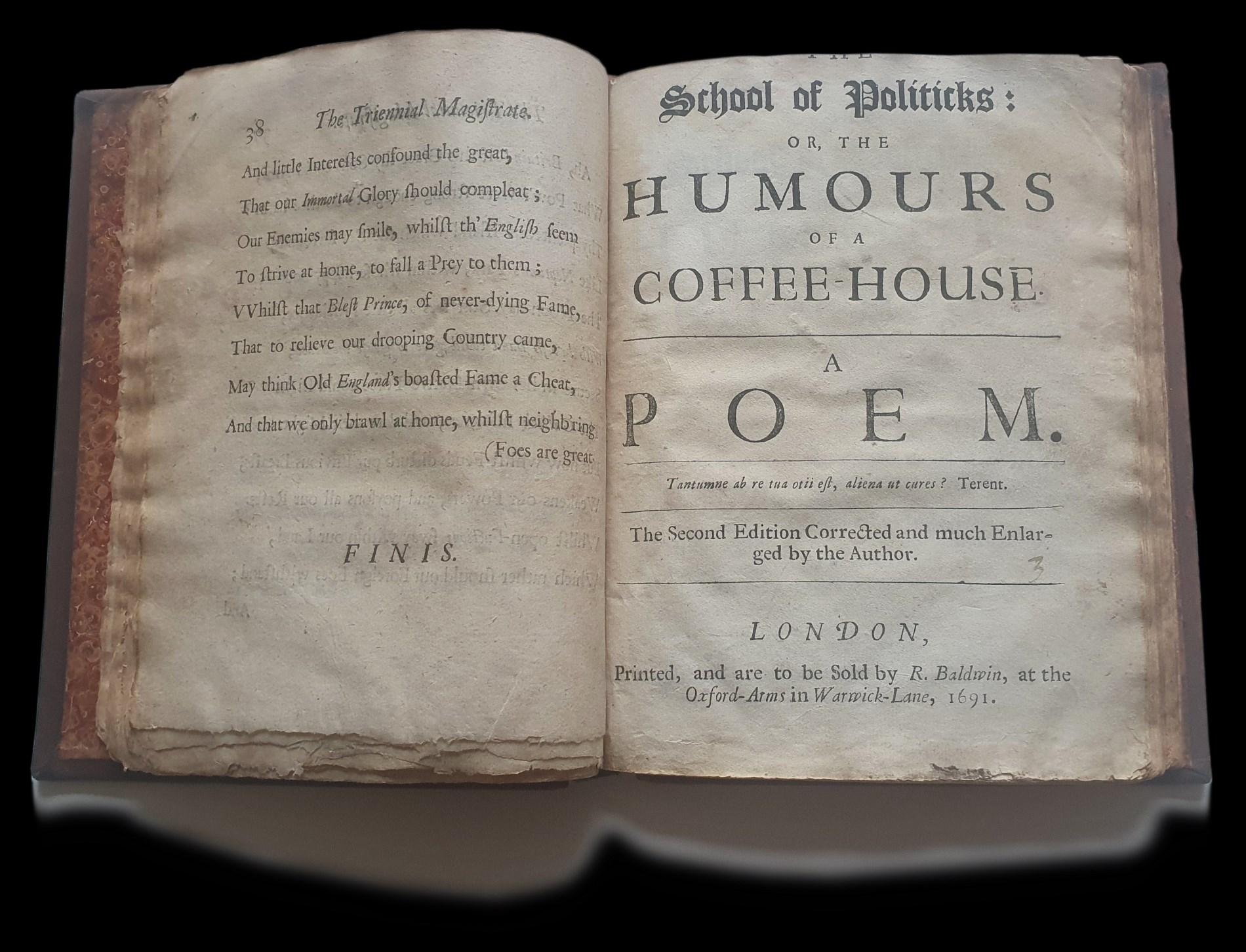

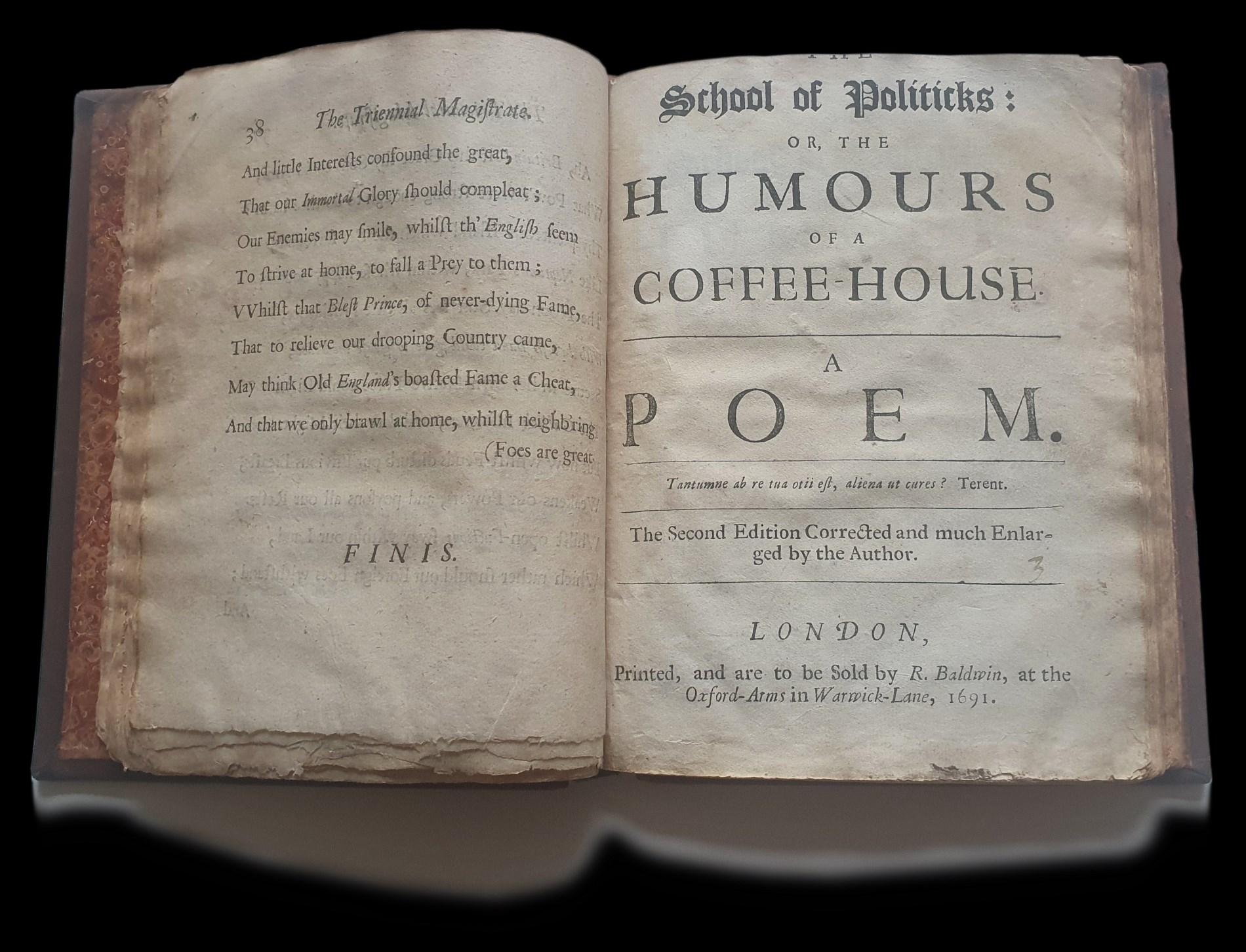

All in all, the lively Restoration culture of disputation and public exchanges of fire on a range of topics is well represented in this sammelband, which appropriately also features Edward Ward’s pamphlet School of Politicks or the Humours of a Coffee House.

CONTENTS:

1.[AMES, Richard (1664?-1692)]. The Search after Claret, or the Visitation of the Vintners, A Poem. London, Printed for E. Hawkins, 1691. FIRST EDITION.

Pagination [4], 18, [2], complete. [ Wing A2989; Goldsmiths 2875; Kress 1754].

ESTC records 5 copies in the UK and 8 in the USA.

The dedication addresses “all Lovers, Admirers and Doters on Claret, / (Who tho' at Deaths-Door, yet can hardly forbear it)”.

2.[AMES, Richard]. A Farther Search after Claret, or a Second Visitation of the Vintners. London: printed for E. Hawkins, 1691. ONLY EDITION.

Pagination [4], 19, [1], complete. [Wing A2977; Kress 1752].

ESTC records 5 copies in the UK, 7 in the USA, and 1 in Australia.

3.[Under-drawer at the ’s-Head-Tavern in Gate-Street]. A Search after Wit, or a Visitation of the Authors in answer to The Late Search after Claret or Visitation of the Vintners. London: printed for E. Hawkins, 1691. ONLY EDITION.

Pagination [4], 19, [1], complete. [Wing A299.].

ESTC records 4 copies in the UK, 4 in the USA, and 1 in Australia.

4.[AMES, Richard]

The Last Search after Claret in Southwark or a Visitation of the Vintners in the Mint ONLY EDITION.

Pagination [4] 11, [1], complete. [Wing A2985; Goldsmiths 2784; Kress 1753].

ESTC records 4 copies in the UK and 7 in the USA.

5.[ANON]. The Triennial Mayor or the New Rapparees. London: printed for Will. Griffits, 1691. ONLY EDITION.

Pagination 1-7, 14-38, lacking pp31-2. [Wing, D2789A, ESTC, R2692]. In praise of Sir Thomas Pilkington. ESTC records 11 copies in the UK and 10 in the USA.

6.[WARD, Edward]. The School of Politicks or the Humours of a Coffee House, Second edition Corrected and much Enlarged by the Author. SECOND EDITION.

Pagination [2], 29, [1], complete. [Wing, W753B]. ESTC records 4 copies in the UK and 10 in the USA.

7.[D’URFEY, Thomas, (1653?-1723)]. The Weesils a Satyrical Fable. London: [s.n.], printed in the year 1691. FIRST EDITION.

Pagination [2] 12, [2], complete. [Wing, D2790B; ESTC R7901]. Well represented in library collections.

8.[ANON] A Whip for the Weesel, or a Scourge for a Satyrical Fopp. London: Printed for J. Norris, and sold by most book-sellers, 1690 [i.e. 1691?]. ONLY EDITION.

Pagination 8, complete. [Wing, W1673].

A reply to pamphlet [7]: Thomas D’Urfey’s The weesils. ESTC records 8 copies in the UK and 6 in the USA.

9.[ANON]. The Anti Printed and Sold by Randal Taylor, 1691. ONLY EDITION.

Pagination 16, 9 16, 9-15, [1], complete. [Wing (2nd ed.), A3516]. Another reply to pamphlet [7]: Thomas D’Urfey’s The weesils. Well represented in library collections.

10.[GOULD, Robert]. A Satyrical Epistle to the Female Author of a Poem, call’d Silvia’s Revenge, &c. By the Author of the Satyr against Woman. London: printed for R. Bentley, at the Post-House in Russel-street in Covent-Garden, near the Piazza’s, MDCXCI. [1691] ONLY EDITION.

Pagination 24, complete. [Wing, G1436].

ESTC records 2 copies in the UK, 6 copies in the USA, and 1 in Australia.

11.[BEHN, Aphra (1640-1689), attributed]. The Restor’d Maidenhead. A New Satyr Against Women : occasion’d by an infant, who was the cause of the death of my friend. Dondon [i.e. London]: printed for H. Smith, 1691. ONLY EDITION.

Pagination [2], 19, [1], complete. [Wing, R1177].

ESTC note: sometimes attributed to Aphra Behn.

ESTC records 4 copes in the UK and 8 in the USA.

12.[AMES, Richard] The Pleasures of Love and Marriage, a Poem in Praise of the Fair Sex. In requital for The folly of love, and some other late satyrs on women. London: printed, for H.N. and are to be sold by R. Baldwin at the Oxford-Arms in Warwick-Lane, 1691. ONLY EDITION.

Pagination [4], 18 [i.e. 26], [2]

The “Epistle to Stella” is signed: Astrophel. [Wing, A2987].

ESTC records 4 copes in the UK, 3 in the USA, and 1 in NZ.

SOLD Ref: 8150

THIRTEEN

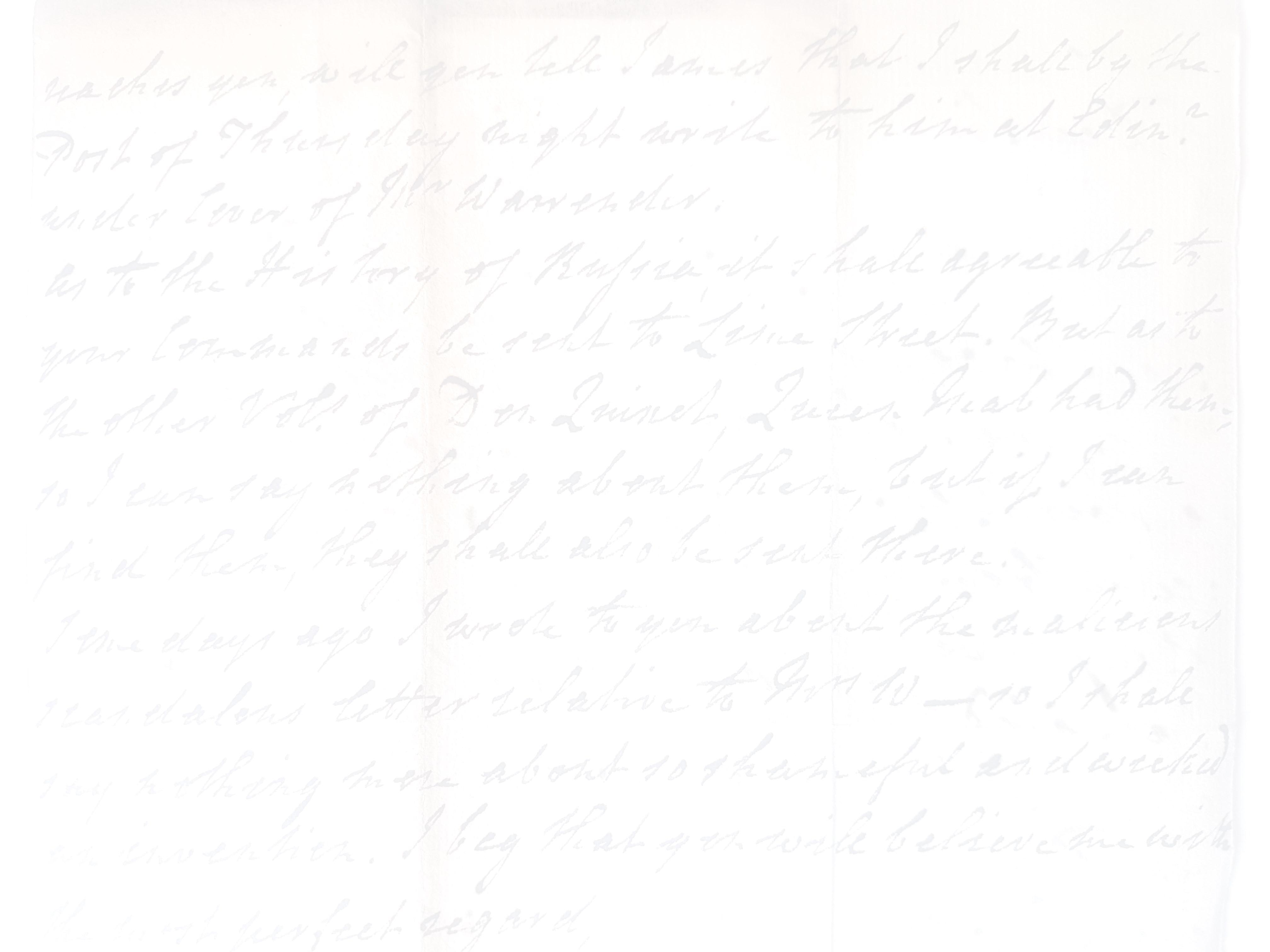

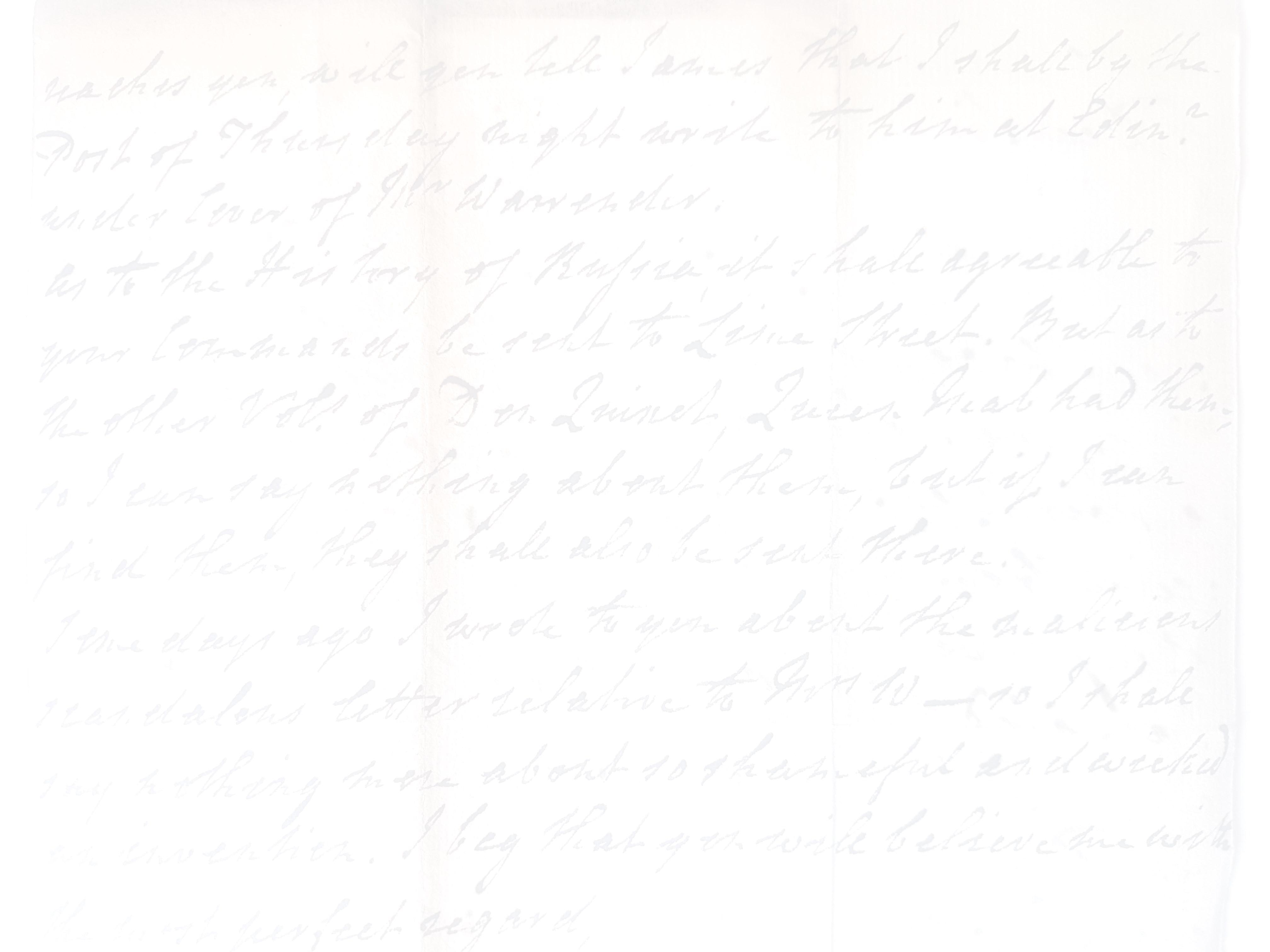

VERNON, James; Summers. Manuscript

Letter-book Concerning the 1698 Treaty

of the Hague.

[Circa 1698]. Small quarto (190 x 150 x 5 mm). 48 numbered pages on 26 leaves. Contemporary marbled wrappers, rubbed, small, neat repair to spine. Scattered spotting to text.

Watermark: Horn (similar to 17th century marks in Haewood, but with countermark of letter V inside an H).

Provenance: later ownership inscription of “Napier” to inner wrapper.

¶ This portable letter-book records some of the strenuous diplomatic efforts by Great Britain, France and the Dutch Republic to prevent war if the ailing and childless Charles II of Spain died. These and other efforts were in vain; but during 1698, when all the letters copied here were written, the select group of negotiators (which included King William III, his Secretary of State James Vernon, the Earl of Portland and the duc de Tallard) were progressing towards the drawing-up of the Treaty of The Hague – the first of two attempted treaties that proposed a partition of Spain’s possessions in Europe. Some of these letters appear in later published works including The History and Proceedings of the House of Commons (1742) others apparently, do not.

The letter-book begins in August 1698, when the two chief negotiators, Portland and Tallard, travelled to The Hague in order to complete discussions and draw up the treaty (Portland’s letters are sent from “Loo”, at The Hague). One might expect a book kept by a senior member of government to be a more impressive and prestigious object; but this is a small-format notebook whose air of basic functionality is strengthened by a vertical crease. The book, it seems clear, was folded for carrying, and it may well be that it was carried about in The Hague rather than in Whitehall – a geographical ambiguity that the unknown identity of the hand leaves unresolved.

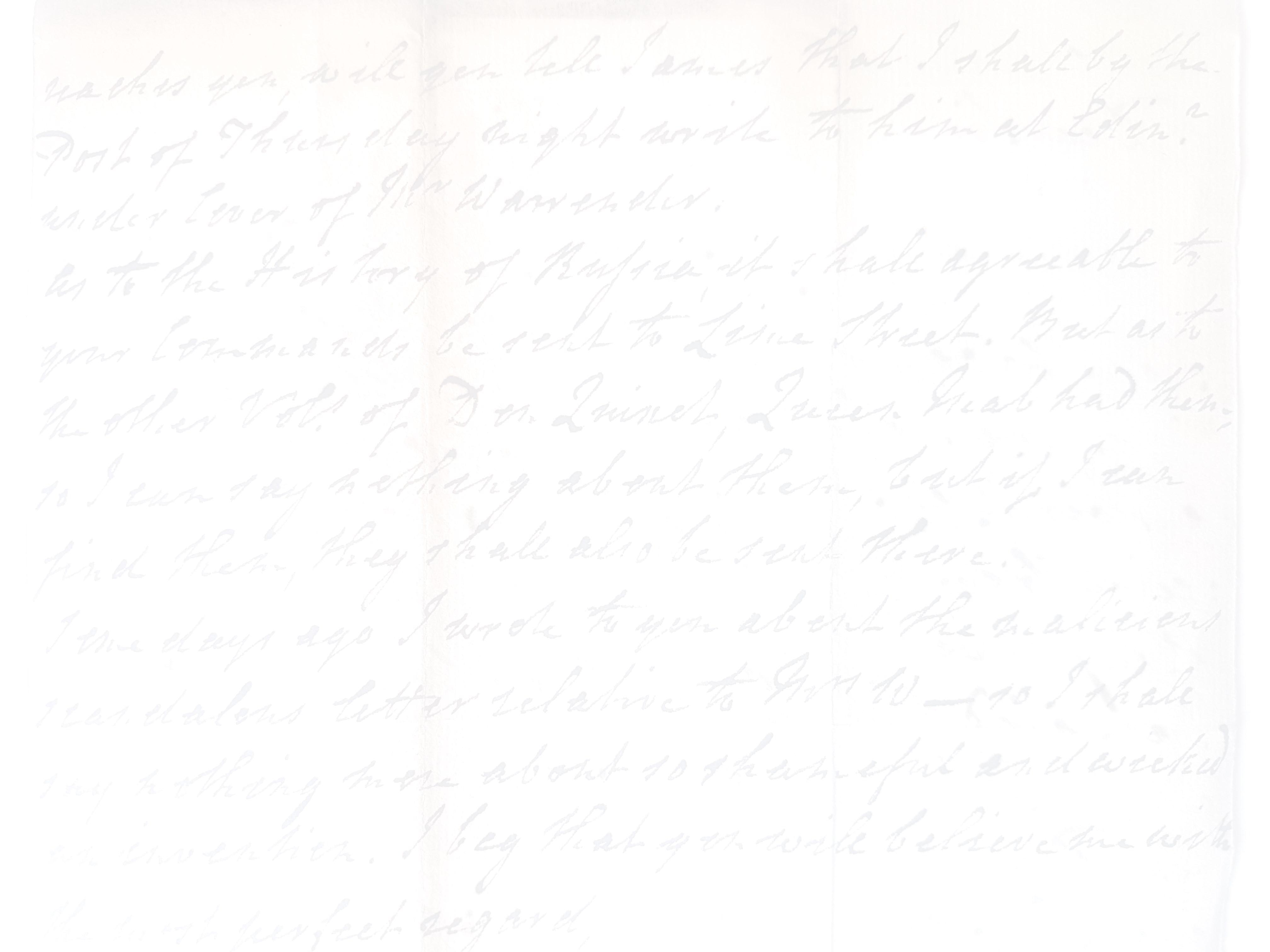

The incremental steps of diplomacy and the preparation of the treaty are traced in these letters, which are mostly exchanged between Portland and Vernon. In an early letter, from King William himself to “Lord Chancelor Summers”, dated “15/25 August 1698”, the monarch stresses: “there is no time to be lost, and you must send me the full powers under the great Seal with the Names in blank, to treat with Count Tallard”. He emphasises secrecy, stipulating “that the Clerks who are to write the Warrant & the full powers may not know what it is”; and urgency, since “According to all intelligence the King of Spain cannot outlive the Moneth of October”. A few pages further on, we read Somers’ reply, from “Tunbridge Wells 28 August 1698” (in which Somers somewhat apologetically reminds the King that he had given him “Permission to try if the Waters would contribute to the Establishment of my health”). His response abounds in the kind of 17th-century realpolitik evident throughout these letters: echoing his colleagues in this book, he points out the “Deadness and want of Spirit universally in this Nation”, whose people are “not at all to be disposed to the Thoughts of Entering into a new Warr”.

As matters progress, the key players mull over the geopolitics of the treaty’s various provisions, the likely behaviour of the French, the uncertain political climate of Britain (Vernon to Portland: “We have a new Parliament and no body can make a ), the urgency of the situation (“Summer is almost gone, and the fall of the Leaf comes on, which is a dangerous season of the ) and the dubious prospects that any treaty will actually be observed (Portland to “I confess experience has showed us too plainly, that Treaties have been ill ). Besides the chief topic, other issues are raised and addressed to varying degrees: the plight of Sir William Jennings, a loyalist of James II now seeking a royal pardon; a petition from one “Col Codrington” that he succeed his father in the governorship of the Leeward Islands; “Mr Elrington who was a Prisoner in that he be granted a military post.

The treaty was signed in The Hague on 11 October 1698; the reasons for its failure, and that of the second partition treaty, are a matter of historical record, as Europe was plunged into another costly war. This letter-book preserves the correspondence between the key negotiators, and as an object which could be either shared or concealed, evokes the earnestness, urgency and pragmatism with which these failed attempts at peacemaking were pursued.

SOLD Ref: 8076 1.<http://www.spanishsuccession.nl/>

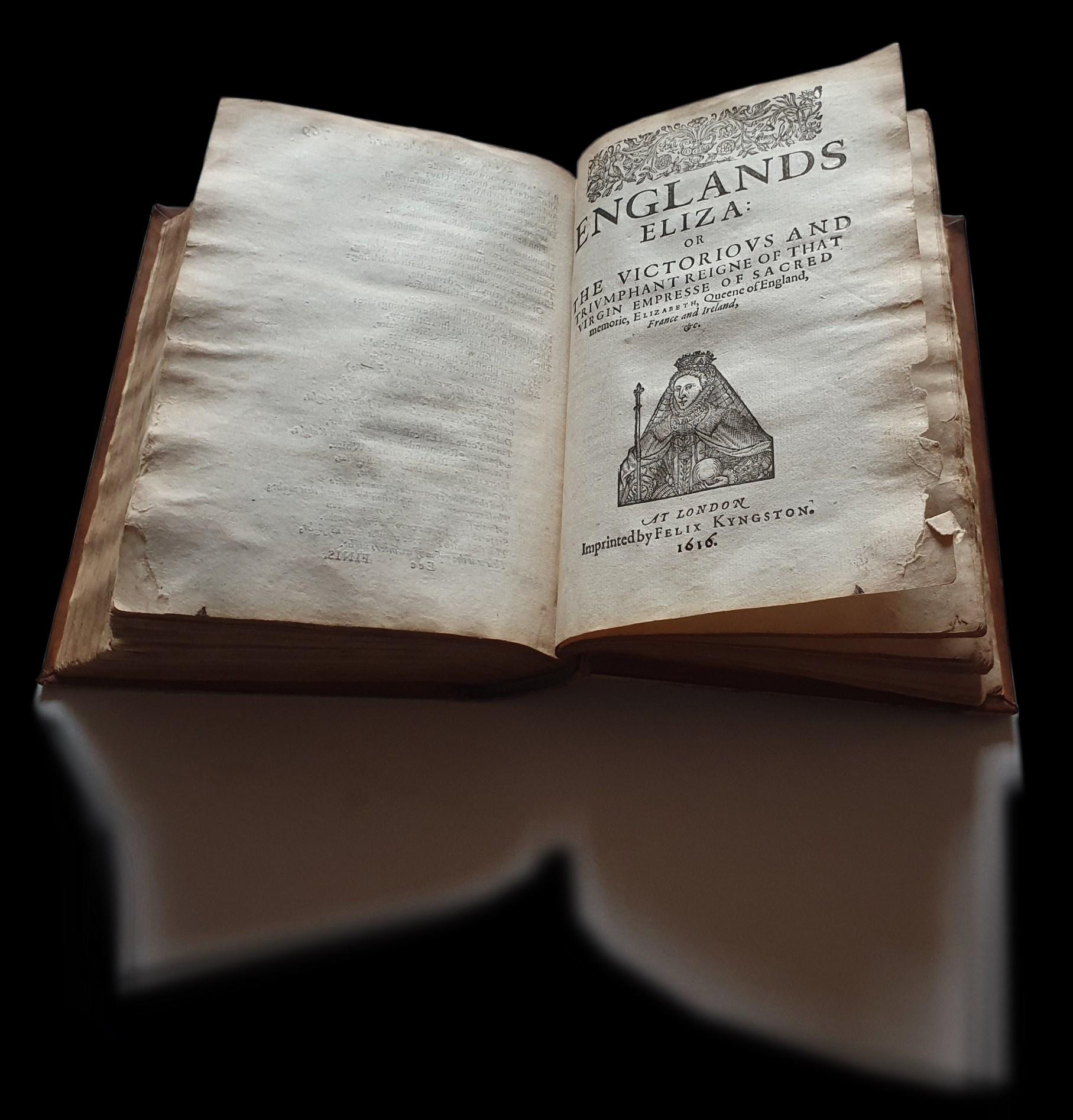

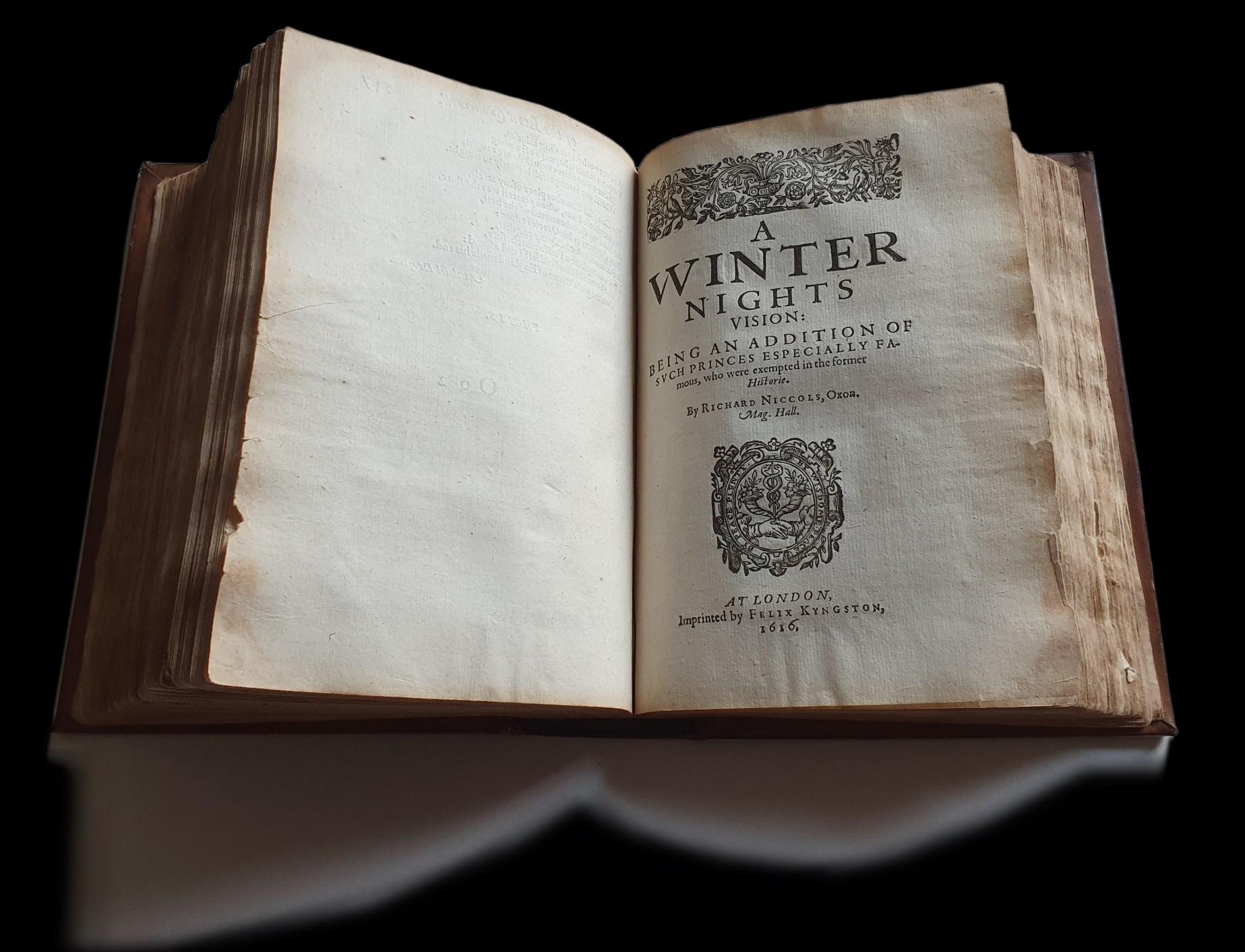

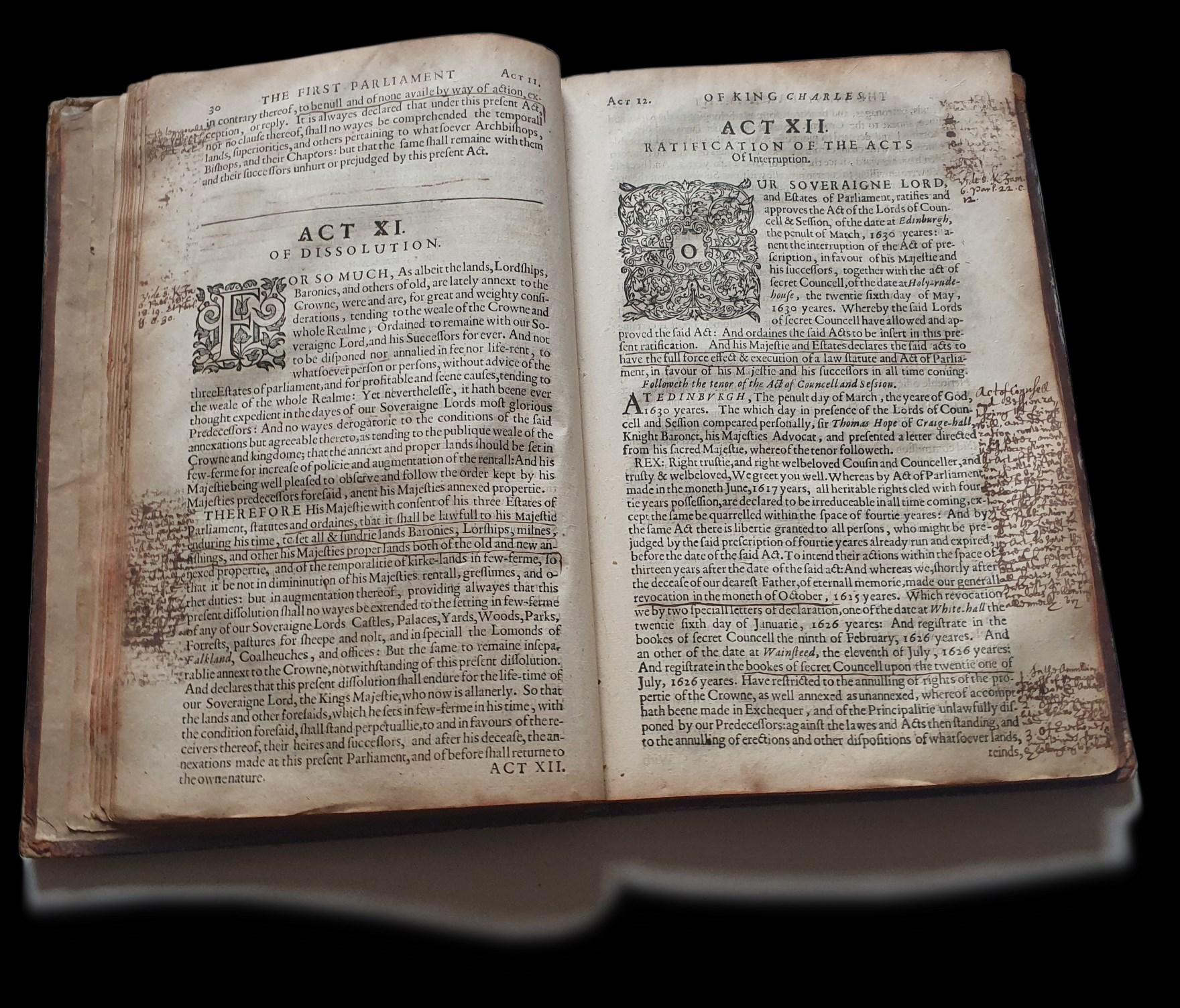

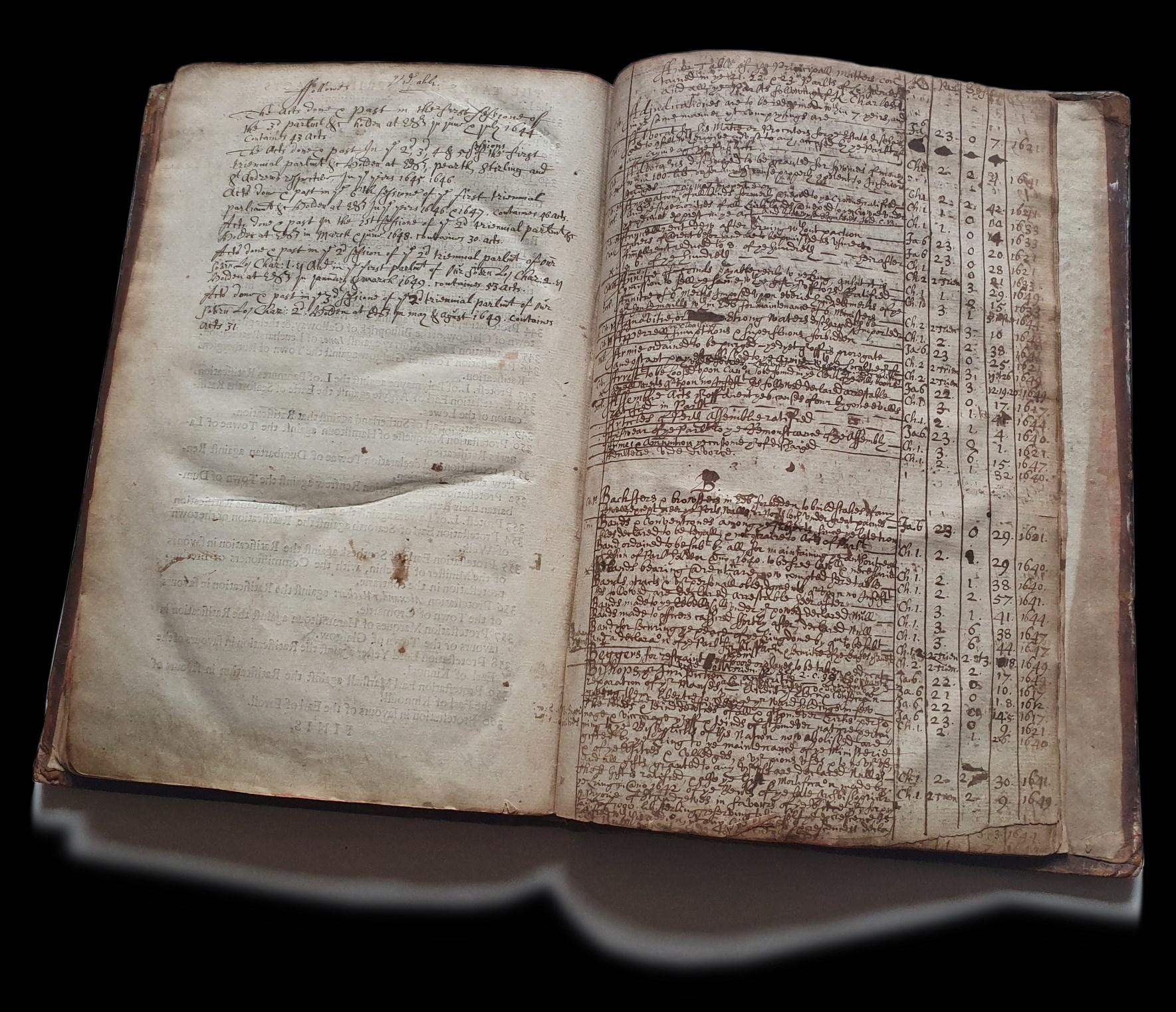

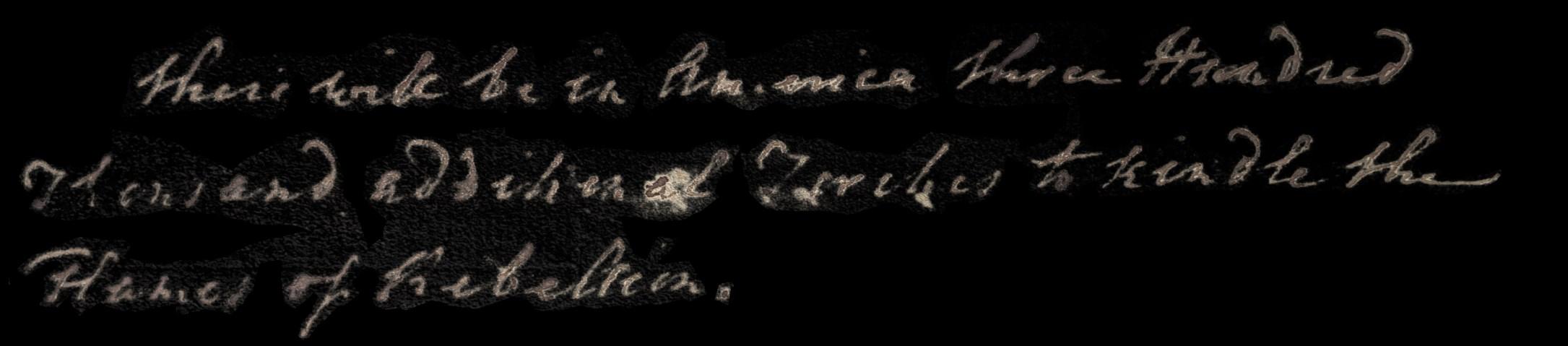

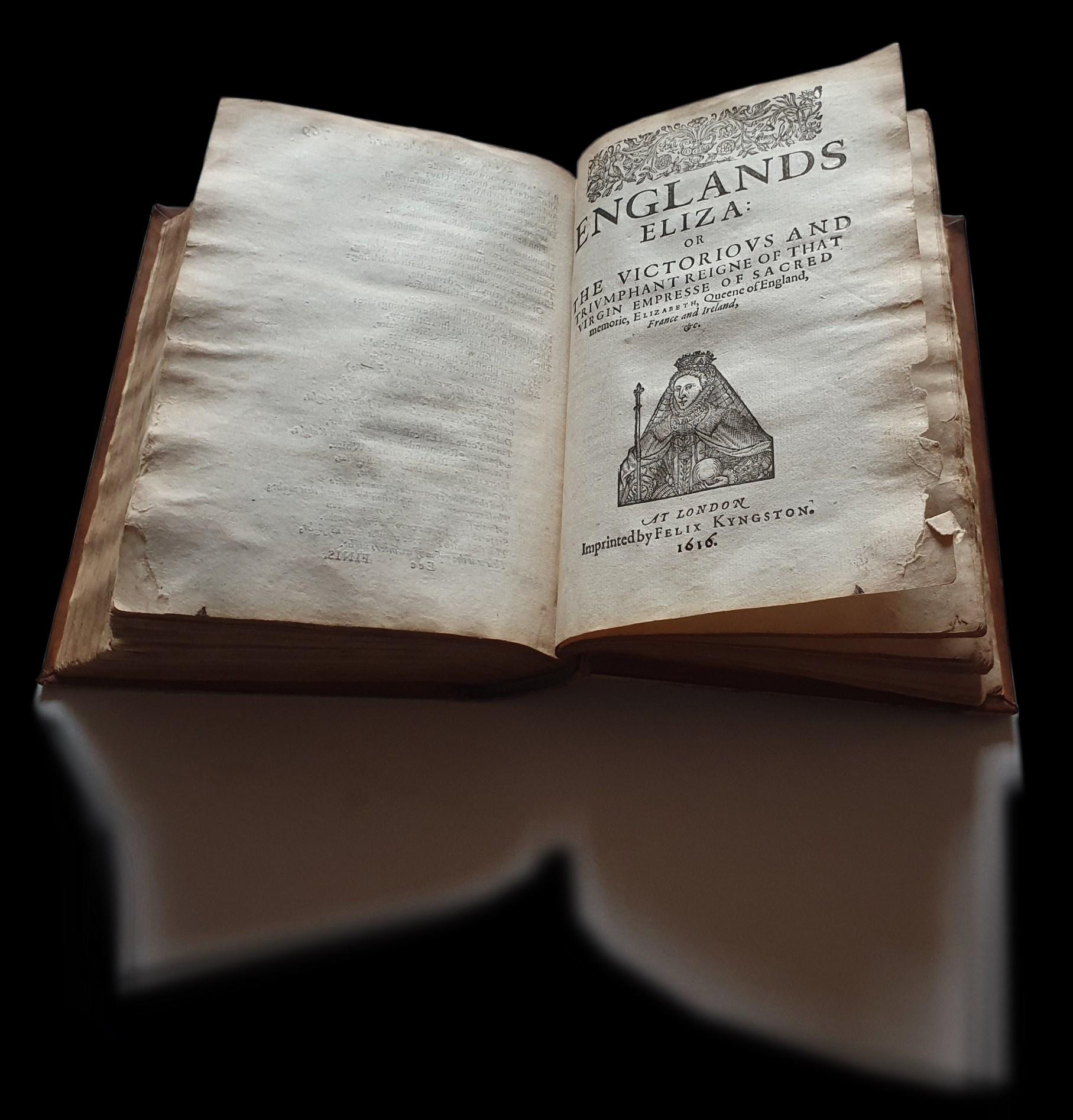

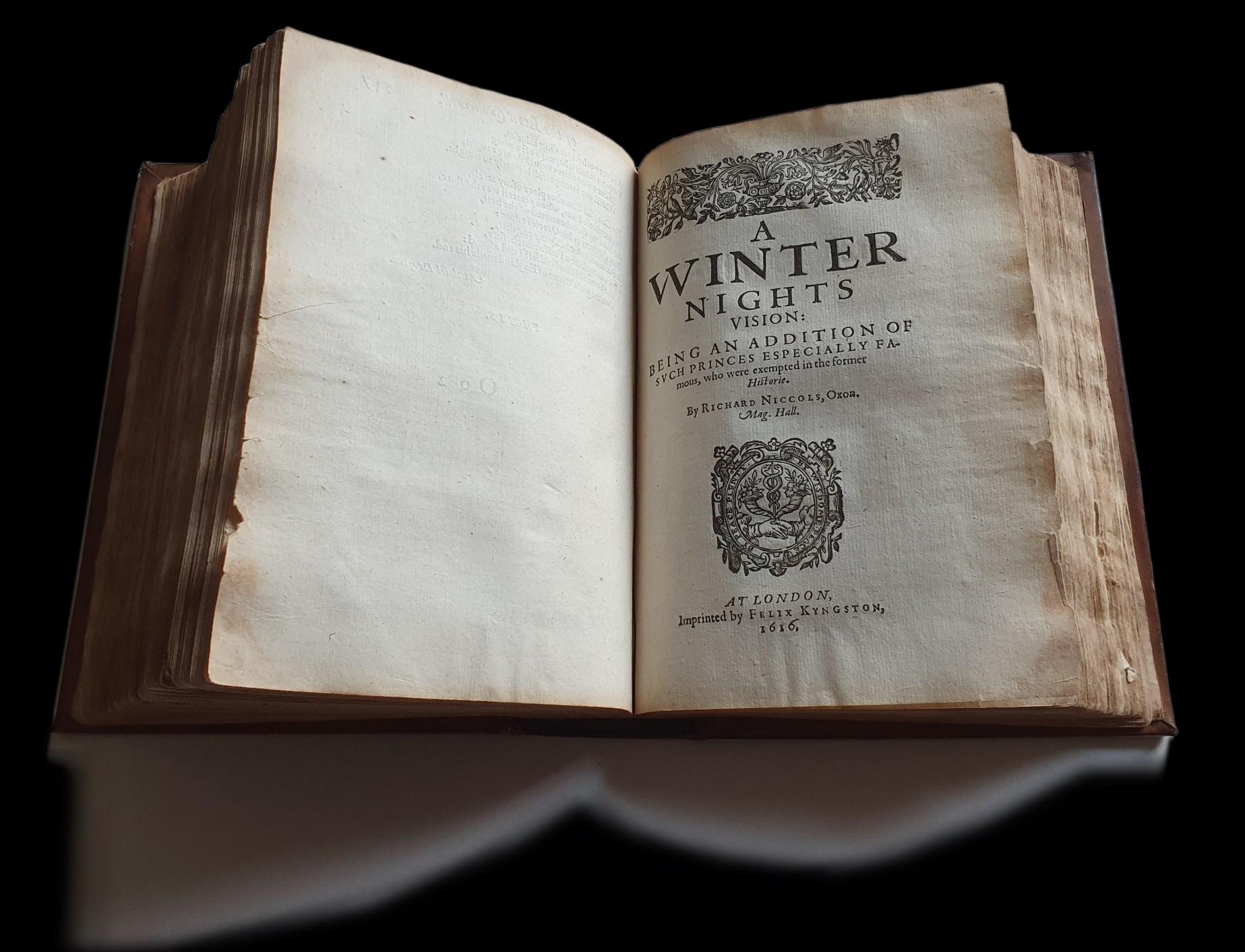

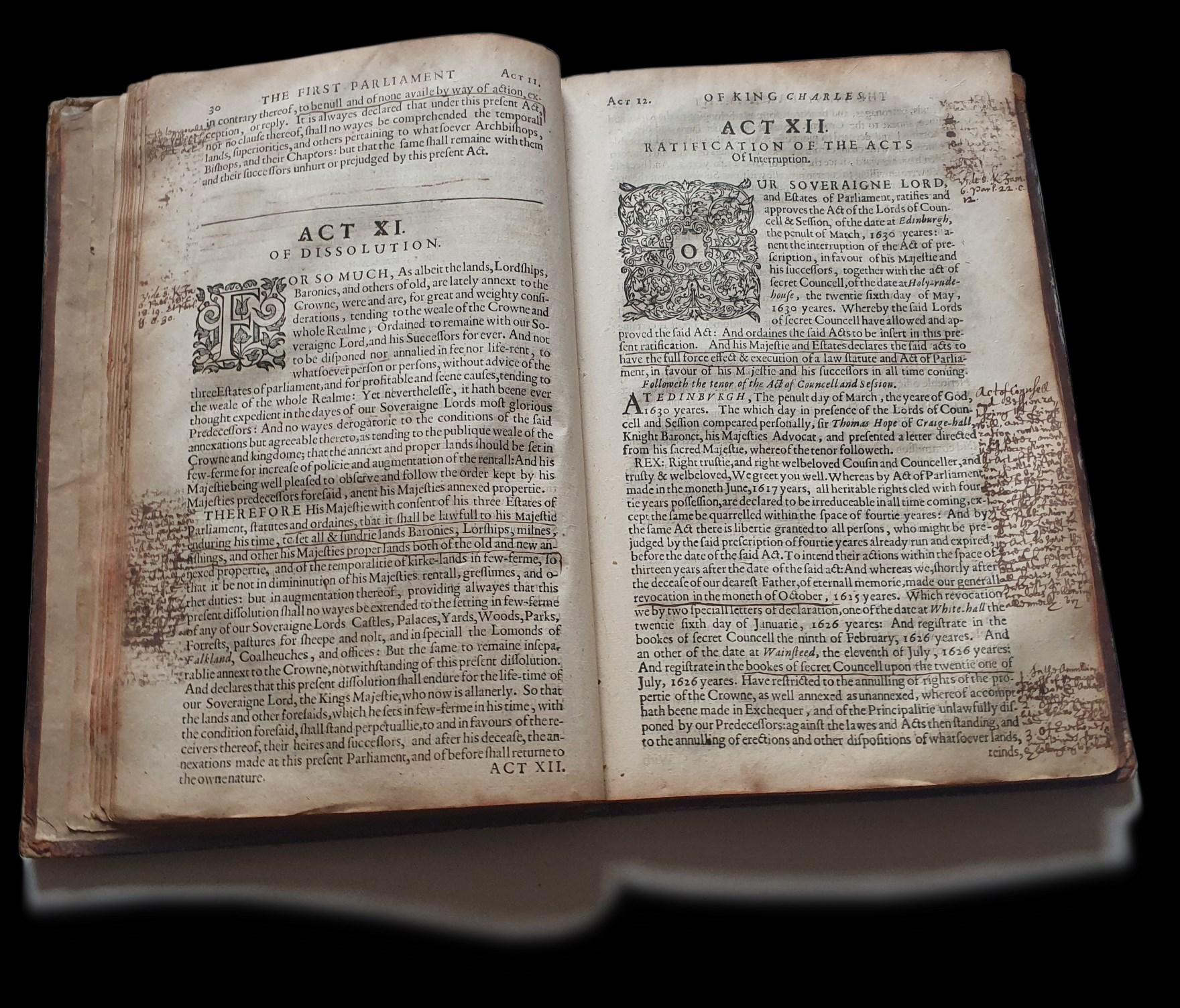

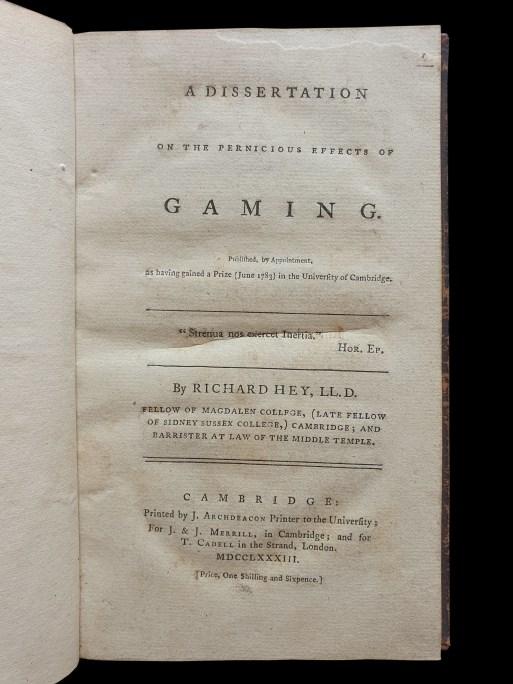

[HIGGINS, John (active 1570-1602)] A mirour for magistrates: being a true chronicle historie of the vntimely falles of such vnfortunate princes and men of note, as haue happened since the first entrance of Brute into this iland, vntill this our latter age

At London: imprinted by Felix Kyngston, 1610-09. Quarto. Pagination [20], 875, [1] p. Woodcut head-pieces, initials, and portraits within text. Collated and complete. Two verse dedications (Oo4 to Charles Howard, and Eee3) present, leaf Eee3 (Variant 3: cancel leaf signed “Nicols”), misbound after A4. [STC 13446; Pforzheimer 738].

Bound in later (probably 20th-century) panelled calf, first few leaves with small hole to blank inner margin, minor worming to first few gatherings, a few times touching text, a few closed tears, but without loss, some light damp staining and softening of blank margins of later leaves (Aaa with small loss to blank sections only.

Three of the four titles have their 1610 date neatly amended to “1616” in early ink manuscript (the 1609 date to ‘The Variable Fortvne’ has not been amended). We have not ascertained the reason for this. There was no 1616 edition of A Mirror for Magistrates, but the date coincides with the death of one of the book’s editors, Richard Niccols (15841616), and of William Shakespeare (15641616). 17th-century ownership inscription and purchase price to title page; “Ma: Weld pre 6d.8a.”

FOURTEEN

¶ A Mirour for magistrates, was an influential sourcebook for Elizabethan dramatists, including Shakespeare, who “was familiar with it and used the story of Queen Cordelia for some points in ‘King Lear’”. Also, to be found here is the story of Locrine, “which was used in the anonymous play of that name wrongly attributed to Shakespeare in the Third Folio”.1 The book is “a collaborative collection of poems in which the ghosts of eminent statesmen recount their downfalls in first-person narratives called ‘tragedies’ or ‘complaints’ as an example for magistrates and others in positions of power”.2

This is a complete copy of the first complete edition of edition collects all three earlier parts of Mirrour for Magistrates and adds ‘A Winter Nights Vision’ and ‘England’s Eliza’ (an account of the reign of Elizabeth I), written by Richard Niccols. Our copy is notable for having its cancel leaves present. According to Pforzheimer, “The general-title in all copies examined is a cancel, for what reason cannot even be conjectured. Originally A Winter Nights Vision had a dedication to Prince Henry, Sig [Oo4], but upon the death of that youthful patron of the arts that leaf was cancelled and a new one containing a dedication to the Earl of Nottingham inserted in its place. Evidently the substitution was delayed for most copies occur without any dedication.”3

1.Bartlett, Henrietta Collins. Mr. William Shakespeare, original and early editions of his quartos and folios; his source books and those containing contemporary notices, 1922. 277

2.<https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/a-mirror-for-magistrates-1574>

3.Jackson, William A.; Emma Va Unger. The Carl H. Pforzheimer Library: English literature, 1475- 1700. 1997. 738.

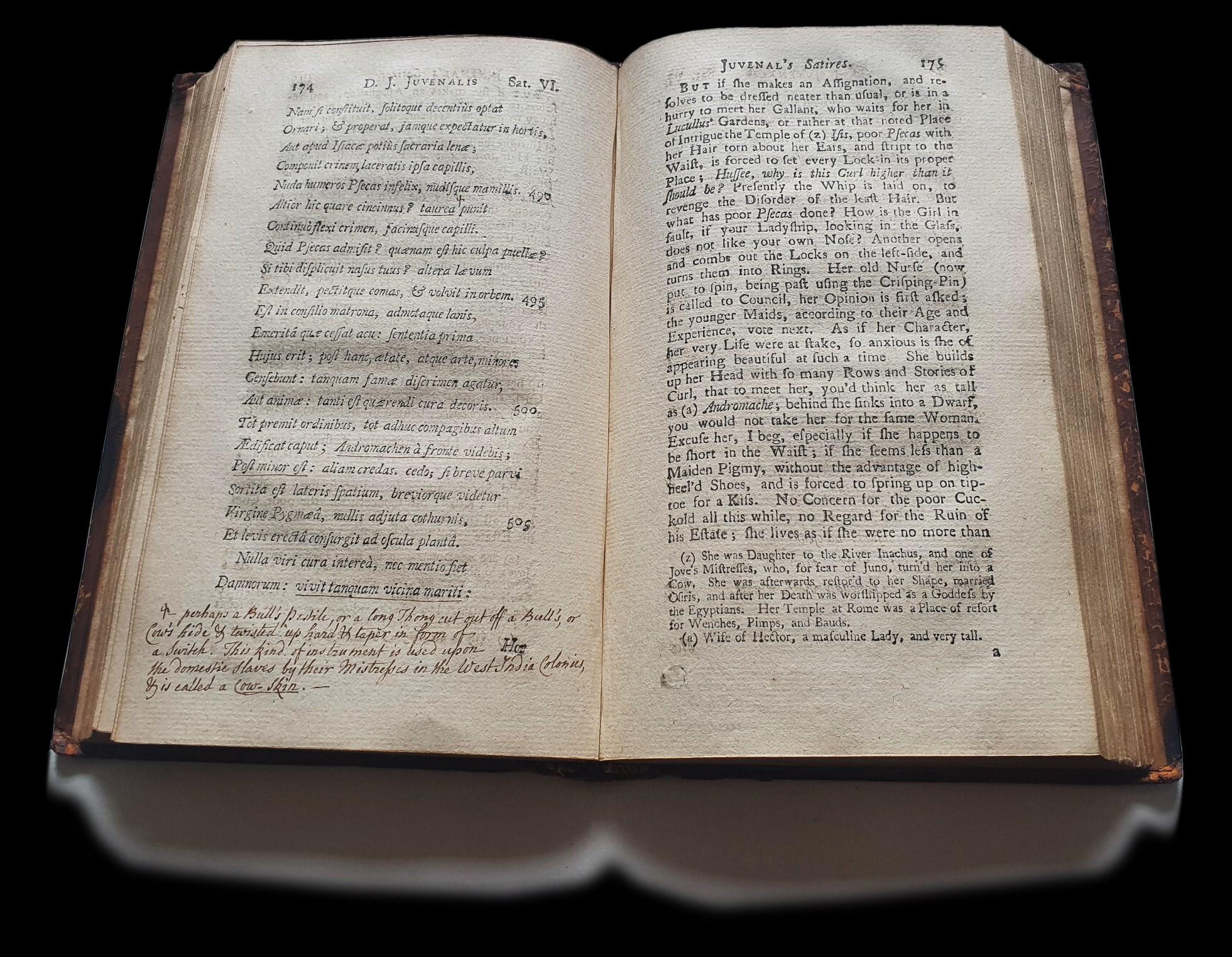

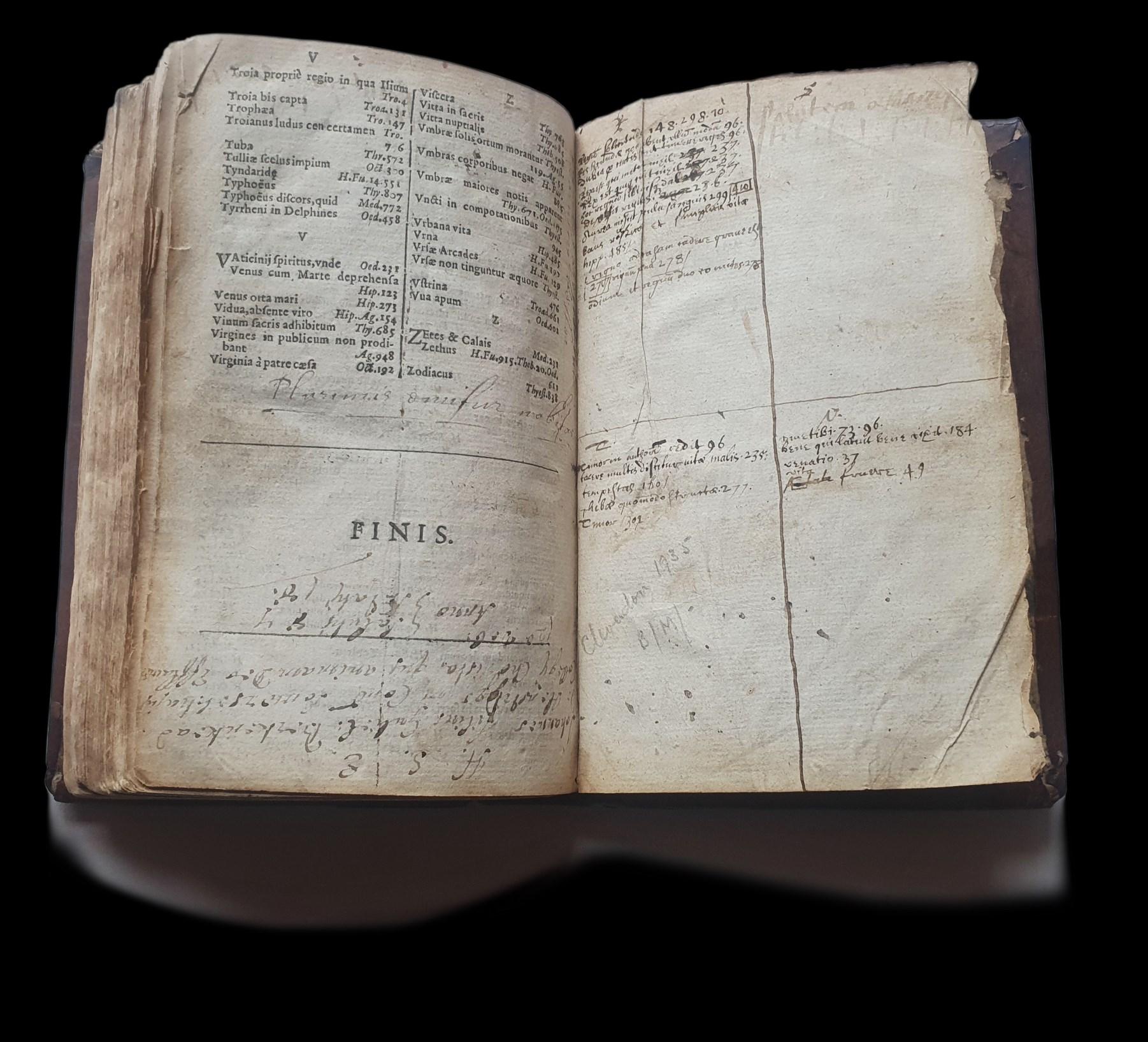

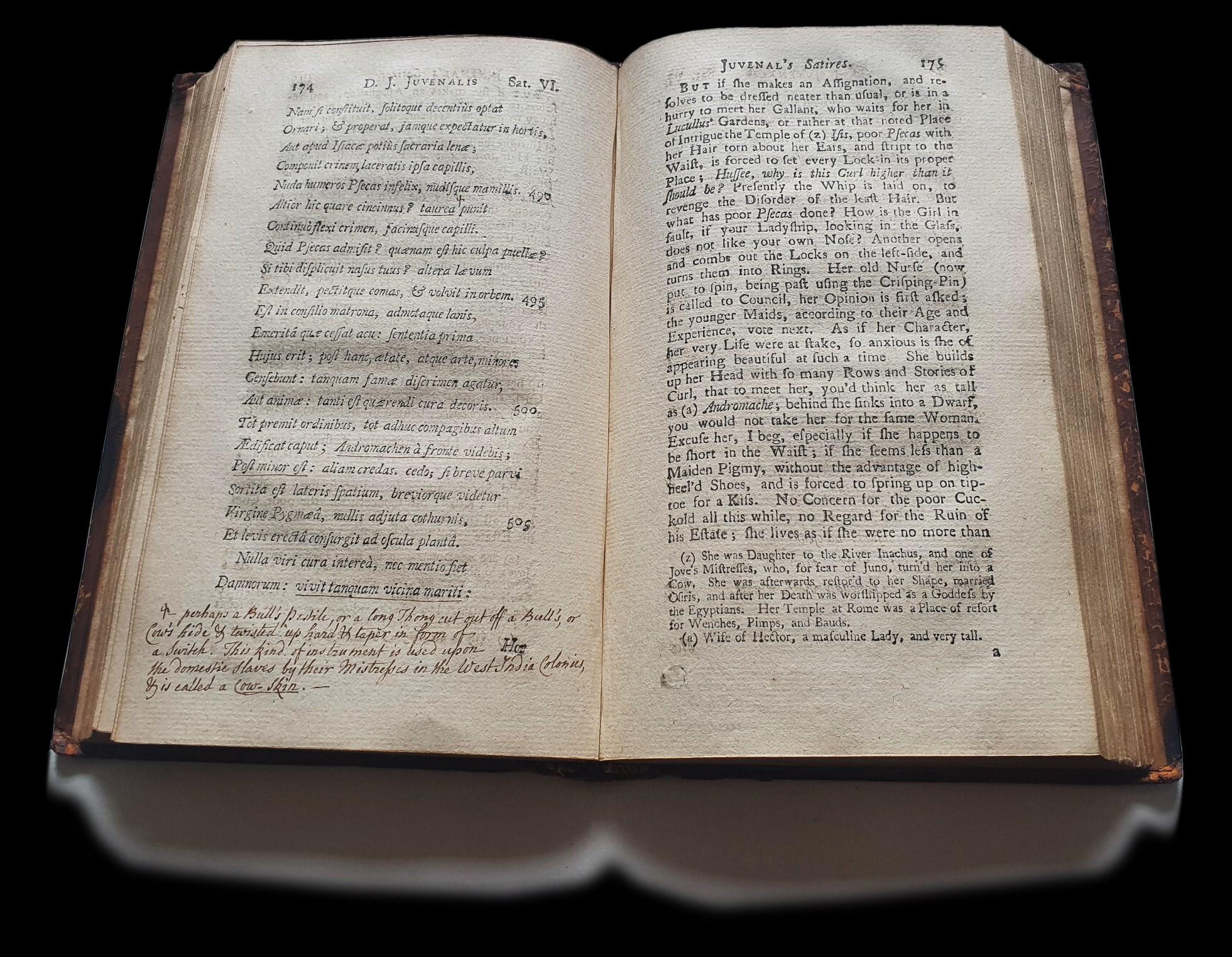

JUVENAL. The satires of Juvenal translated: with explanatory and classical notes, relating to the laws and customs of the Greeks and Romans. Annotated in an a contemporary hand.

London: printed for J. Nicholson, in Cambridge; and sold by C. Crowder, Paternoster-Row, and J. and F. Rivington, in St. Paul’s Church-Yard. [London], MDCCLXXVII. [1777]. Pagination xvi, 416 p. complete with the half-title. Contemporary mottled calf, rebacked preserving original spine.

Provenance: armorial bookplate of “Sir Thomas Hesketh, Bart. Rufford Hall, Lancashire.” Library shelf reference label to pastedown: “Easton Neston Library” (also a country seat of the Hesketh family). The bookplate is dated after 1761, when Sir Thomas was created Baronet. (A young William Shakespeare is thought to have performed in Rufford Hall for the entertainment of an earlier Sir Thomas Hesketh.)

¶ This parallel Latin and English edition of Juvenal’s ‘Satires’ (written during the Roman Empire) includes annotations that pointedly refer to the British Empire’s colonial territories in the West Indies.

Thomas Sheridan’s translation of Juvenal was first published in 1739; an early owner of this copy of a 1777 edition was evidently unaware of Sheridan’s authorship and has added “By Dunstan” to the title page, possibly thinking of Samuel Dunster, translator of Horace satires in the early 18th century. Whether our annotator is Sir Thomas Hesketh is uncertain, but he pasted in his bookplate in the last year of his life and the “Easton Neston Library” label dates from after his death.

The scribe has gone through the text and added notes, including short summaries at the beginning of each satire, as well as frequent underlining, occasional corrections to the text (both Latin and English), and notes on the meaning and context of some of the Latin words and phrases.

Our annotator draws out similarities with contemporary customs and culture: in Satire [II] (p.36), they have underlined “Dives erit, magno quae dormit tertia lecto” and added the note “This Line is applicable to his present Majesty the Baby King of Denmark with his late Queen & Count Halk” – likely a reference to Christian VII (1749-1808) who ascended the throne in 1766 aged 17 years.

One strand of annotations suggests an inclination to compare the Roman and British empires: commenting on Satire [XI] (p.308), they write: “The Romans, after they grew refined, affected the Greek as much as we do the French Language” –implying that the British have achieved a Roman level of refinement The scribe is keen to point out parallels in the classical text with the customs of the colonial West Indies: in Satire II (p 42), they have underlined “Et pressum faciem digitis extendere panem” and added in the margin below: “It is a Custom with some of the Ladies at Montserrat […] to retire for a fortnight to

FIFTEEN

refresh […] The discipline is exceedingly severe. They rub their faces over with ye oil of ye Cusso ^Cushoo nut. This lying on for a fortnight brings off all the skin of their face like a Mask, but if they smile, or distort their face in the least during this painful operation, they come forth horrid Spectacles.”

These anthropological asides occasionally betray a certain callousness: in Satire [VI] (p.174), on the line “Altior hic quare concinnus? Taurea punit”, the scribe underlines “Taurea” and adds a note: “perhaps a Bull’s Pestile, or a long Thong cut out off a Bull’s, or Cow’s hide & twisted up hard & taper in form of a switch. This kind of instrument is used upon the domestic Slaves by the Mistresses in the West India Colonies”. Clearly demonstrating that people in Britain were aware of the appalling treatment of enslaved people. Homophobia, too, is a feature, in the note to Satire [II] (p.28), which observes: “Here the Poet scourges the Hypocrisy, Effeminacy, & Bestiality of his Countrymen, as contradistinguished from the vilest & most libidinous Turpitude of Women. He is particularly severe upon that abominable intercourse between the male Sex. Which was highly fashionable.”

If our annotator displays some of the common prejudices of their era, they also indulge in some satirical jabs of their own. Against a line in Satire [III] (p.54), “Res hodie minor est, here quam suit, atque eadem eras. Deteret exiguis aliquid” (“since my means are less today than they were yesterday, and tomorrow will rub off something from the little that is left”), they observe drily (if cryptically): “An admirable picture of England in 1779”.

SOLD Ref: 8065

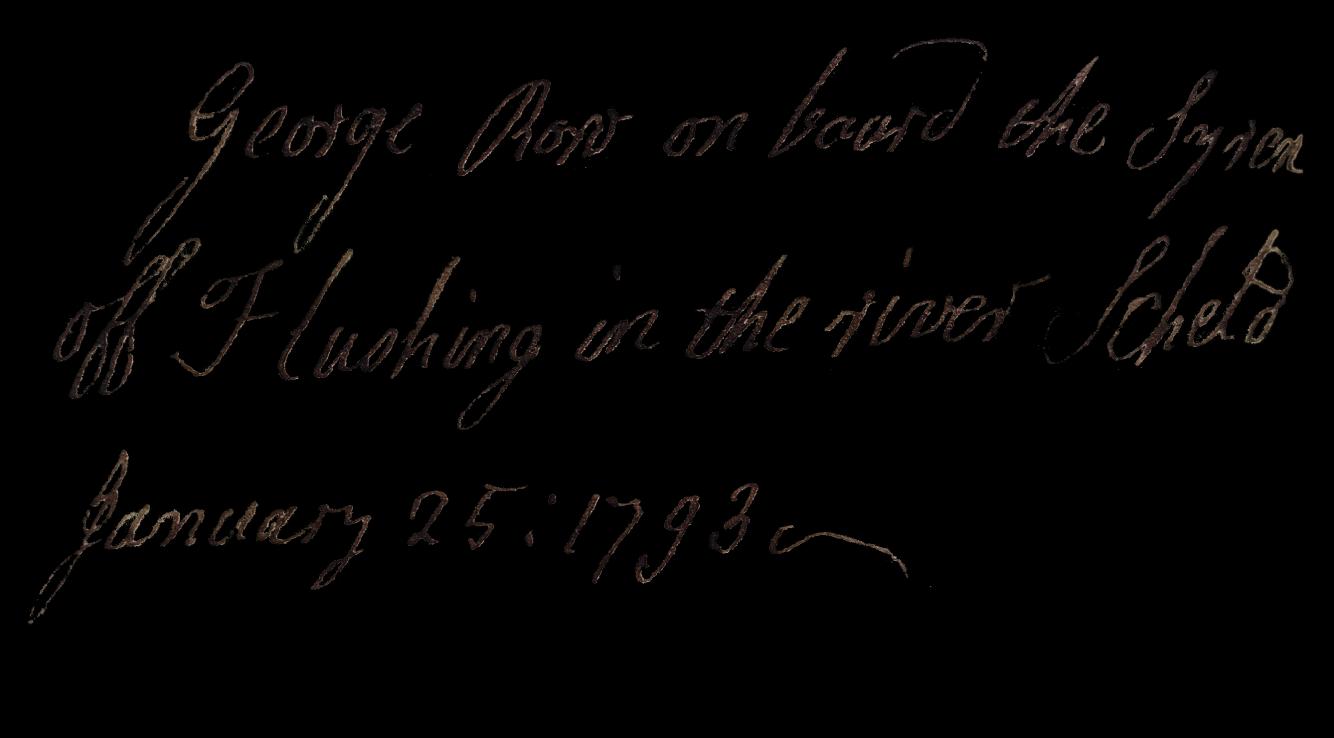

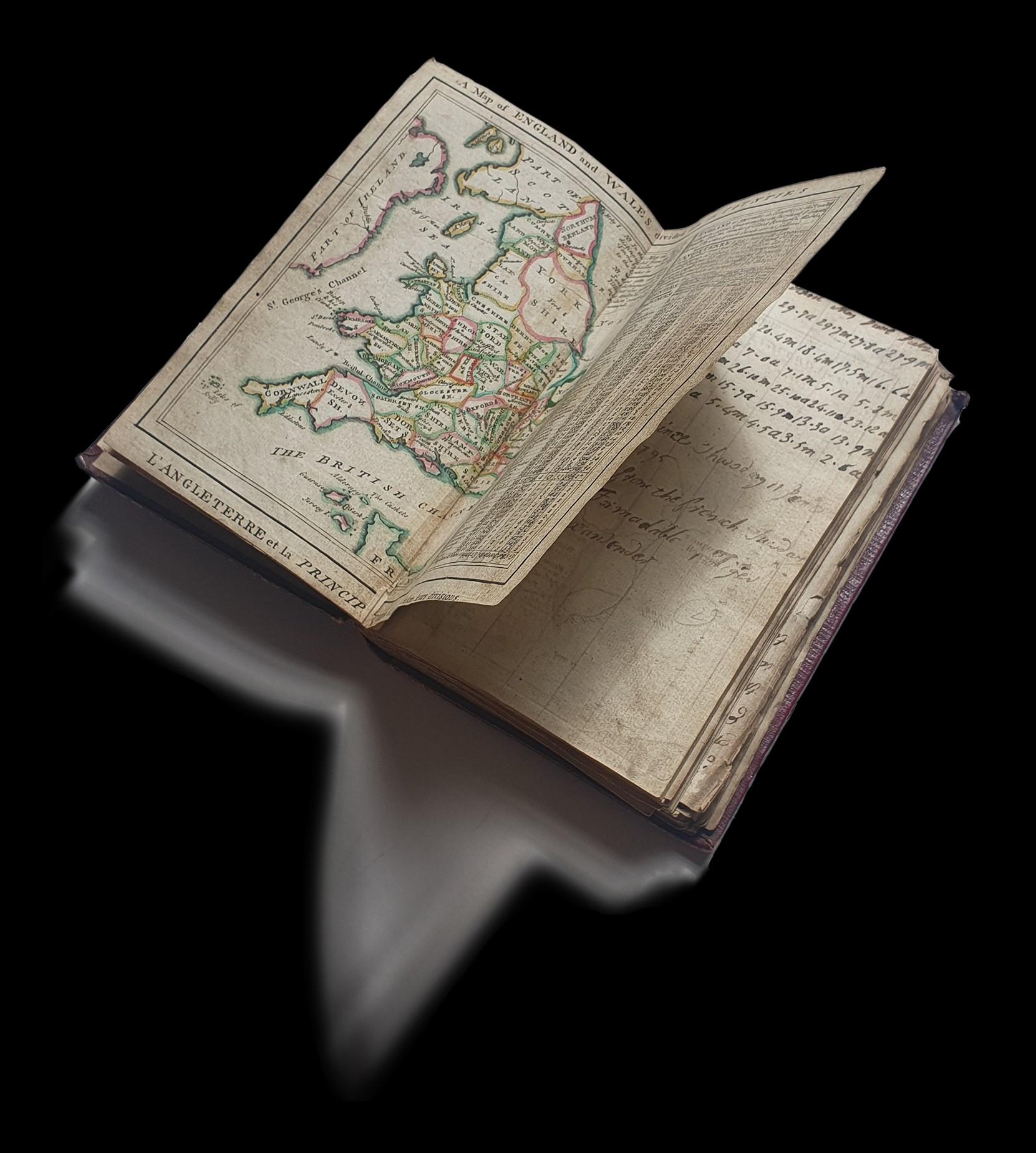

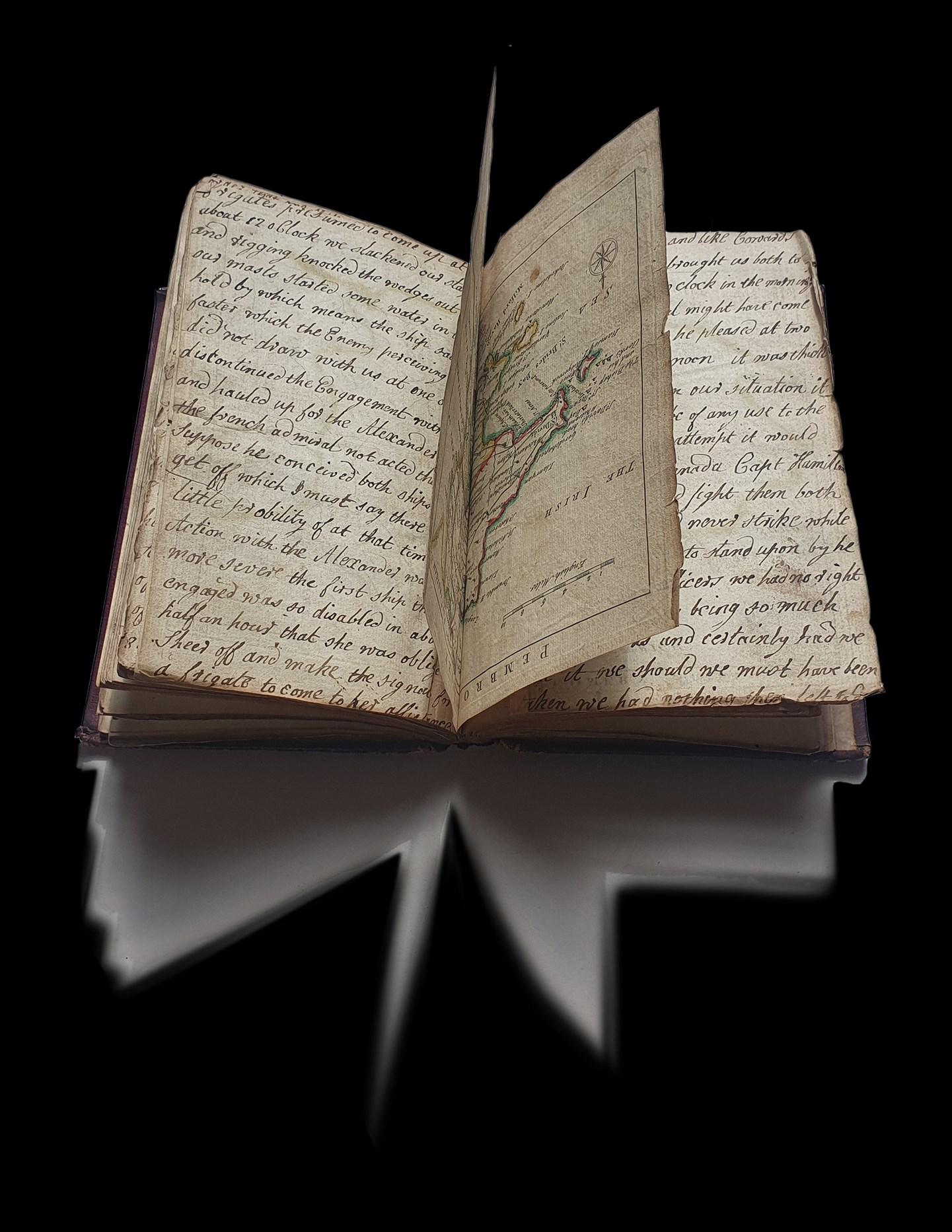

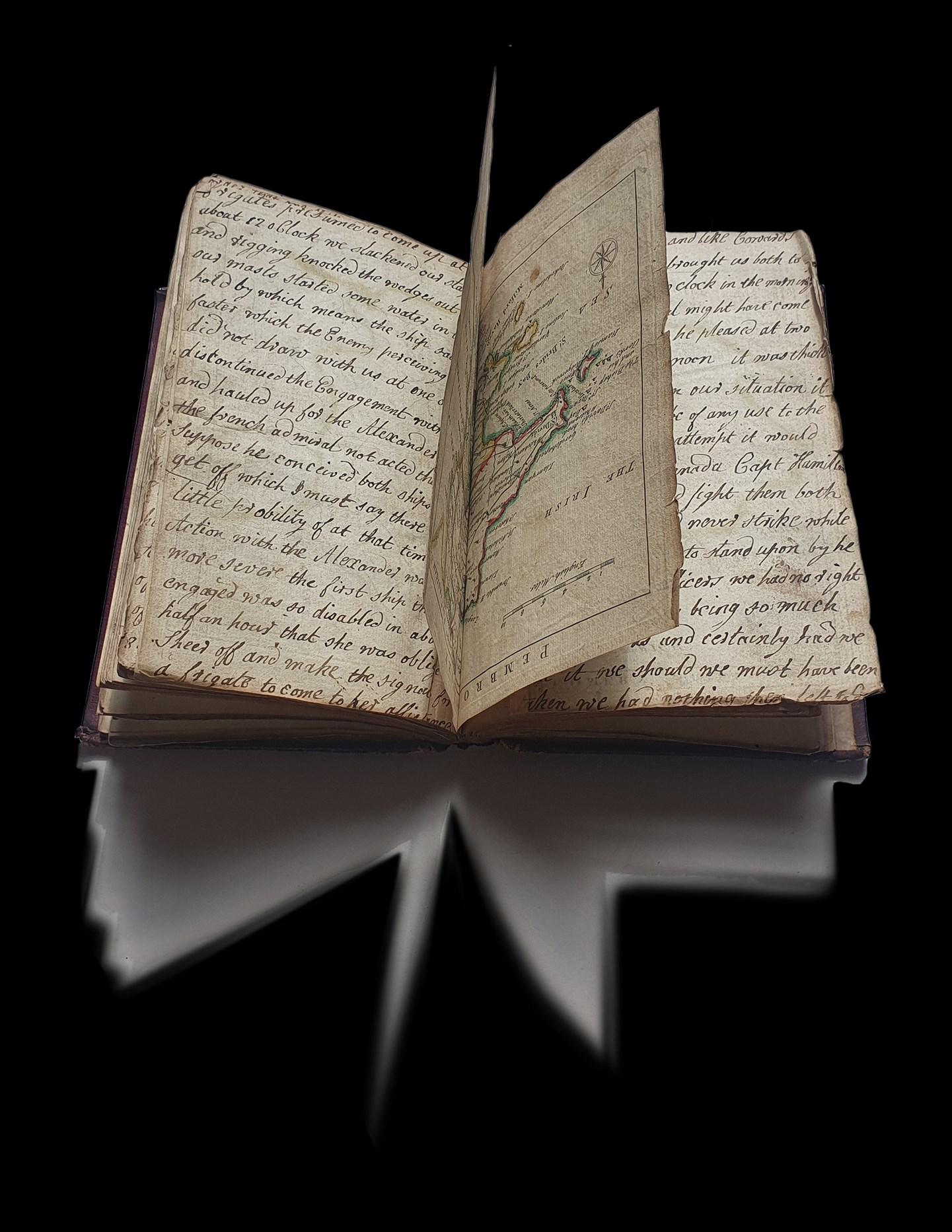

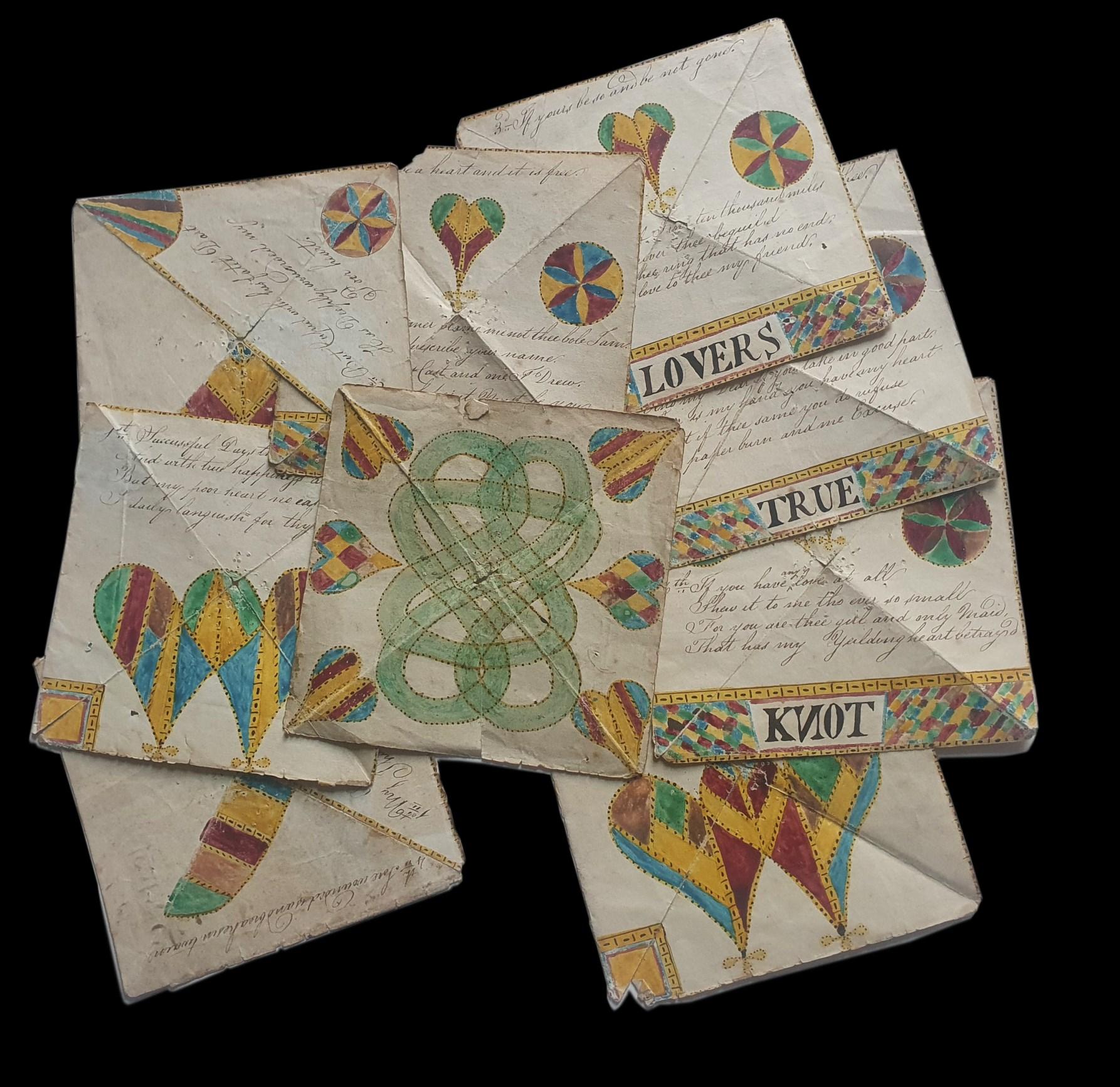

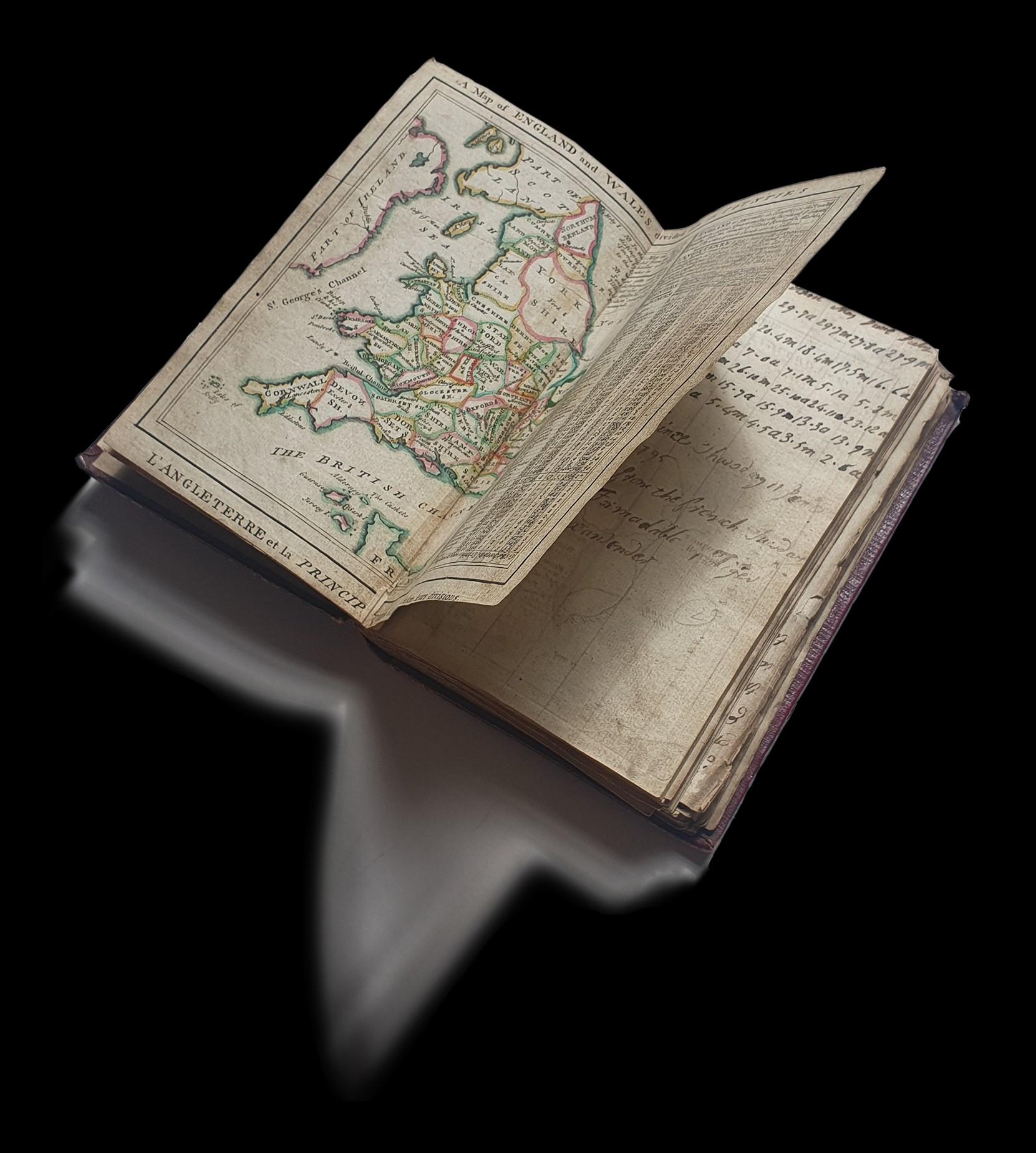

[ROW, George; ROQUE, Jean] Le Petit Atlas Britannique with manuscript notes in an 18th-century hand.

[1753]. Octavo. Letterpress title page in French and 47 (presumably only of 54 double-page maps engraved maps). The maps are hand-coloured in a contemporary hand. Manuscript notes to some pages and a nine-page account entitled “Capture of the Alexander”, which is written in the same hand as the scribe “George Row” (see provenance).

Early 19th-century straight-grained morocco, rubbed and worn, several leaves loose.

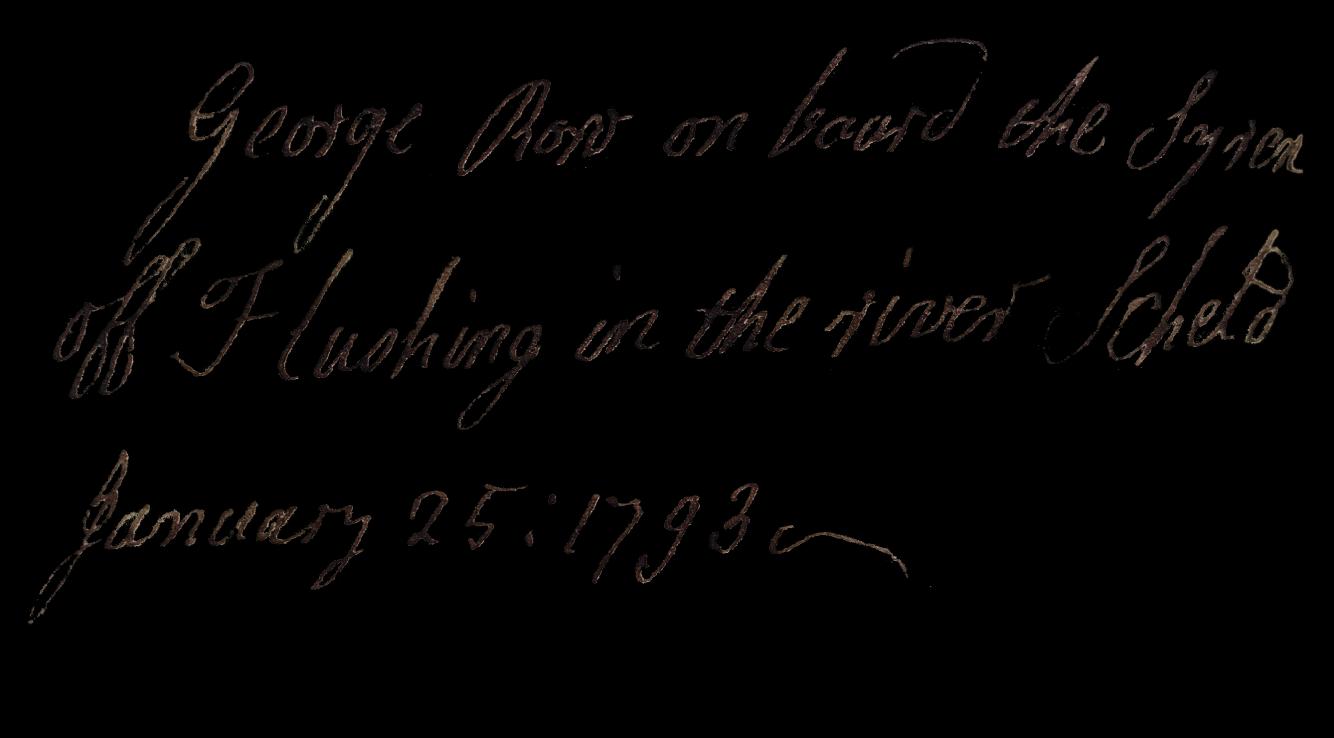

Provenance: inscription to the reverse of the map of Essex: “George Row on board the Syren / off Flushing in the river scheld / January 25 : 1793”

Inscription to reverse of Oxfordshire: “Richard Stroud His Hand 1799”. Inscription to title page: “W. Tollmach”. The Tollemaches were earls of Dysart; of Ham House and Helmingham Hall, Suffolk.

A rare atlas: ESTC locates three copies of the 1753 edition (Cambridge University Library, National Library of Ireland, and Bibliothèque Mazarine, Paris) and one copy of the 1762 at the Bodleian.

Both recorded editions of the Rocque’s atlas have engraved, parallel English and French title pages. In the 1753 edition, 42 of the 54 maps are numbered and all 54 maps are numbered in the 1762 edition; whereas our copy has only a French title page in letterpress and none of its maps are numbered.

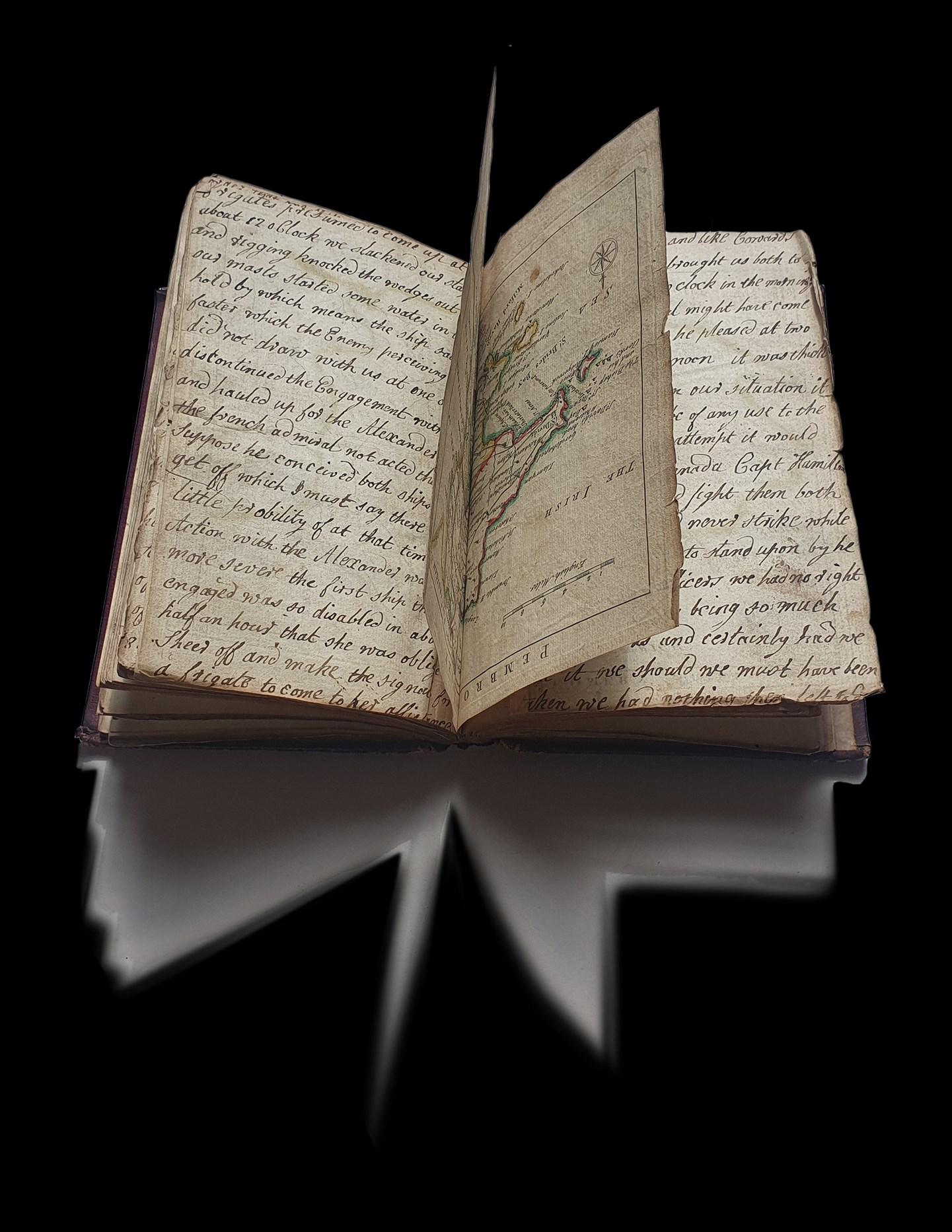

¶ There are two recorded editions of Jean (or John) Rocque’s Le Petit Atlas Britannique: one published in 1753 and one in 1762, both in London. As noted above, there are very few surviving copies of either, but what makes this copy all the more unusual is, first of all, the letterpress title page, of which we can find no other examples; and more significantly, the manuscript addition of a remarkable 1,150-word, first-hand account of a naval encounter in November 1794 that led to the capture of HMS Alexander by the French navy.

The author of this nine-page eyewitness description declares himself in an inscription to the reverse of the map of Essex: “George Row on board the Syren / off Flushing in the river scheld / January 25 : 1793”. After Flushing, he next plots his location as “Syren off Spain Monday 3 June 1793” (on a blank page shortly after the title page); by the next year, he was evidently serving on the HMS Canada when it was returning from Cape St. Vincent in company with the Alexander and the two warships became involved in a skirmish with a French squadron of five line-of-battle ships, three frigates, and a brig.

SIXTEEN

Row makes a series of apparently arbitrary decisions as to where to add his account: he chooses to flip the volume upside down and to begin writing on the reverse of “Isle of Wight”, continuing to “Merioneth Shire and Montgomery Shire” – neither of which are geographically very close to the site of the action that he unfolds.

He describes how “the Alexander of 74 Guns and our Ship of the same force”, having helped escort a convoy “ as far as Cape of St Vincent”, was returning to England “when about six [ ]ive Leagues to the Westward of Scilly at [t]wo clock in the morning of the 6th of this month we fell in with a french Squadron men of war”. Despite “masterly manoeuvring” by both ships, “the Enemy were of so Superior force it was thought necessary to separate” in order to split their pursuers. But in due course, Row relates, the French admiral “in the most dastardly manner hauled up for the Alexander being we imagine determined to make sure of one ship I say dastardly because if three heavy line of battle ships could not secure the Alexander he ought never to have gone to their assistance and should himself have chased us” – a breach of maritime etiquette, evidently.

Row speculates that “had we fortunate had a nother line of battle ship I believe we should have beaten them for the French handled their so bad and like Cowards”. After the enemy’s unprincipled pile-on, and having dismissed the idea of going to the Alexander’s aid against overwhelming odds, “we had nothing then left to do but to make the best of our way to England”. The manuscript is inscribed at the end “Canada Novmb. 6th 1795”. The date is perplexing because the Alexander was captured a year to the day earlier, on 6 November 1794. Our assumption is that this is a simple misdating because there is no obvious reason why he should be recounting the events of a year ago, nor would he have been compiling his account to be given in evidence: the court martial of the commander of HMS Alexander, Admiral Rodney Bligh was conducted on 25 May 1795. The court found in his favour, and he was honourably discharged.

Whatever the reason for the slightly puzzling date, and the atlas’s confounding publication details, Row’s narrative makes for compelling reading and attests both to the conduct of Bligh and to the impact of the events on the young able seaman.

SOLD Ref: 8160

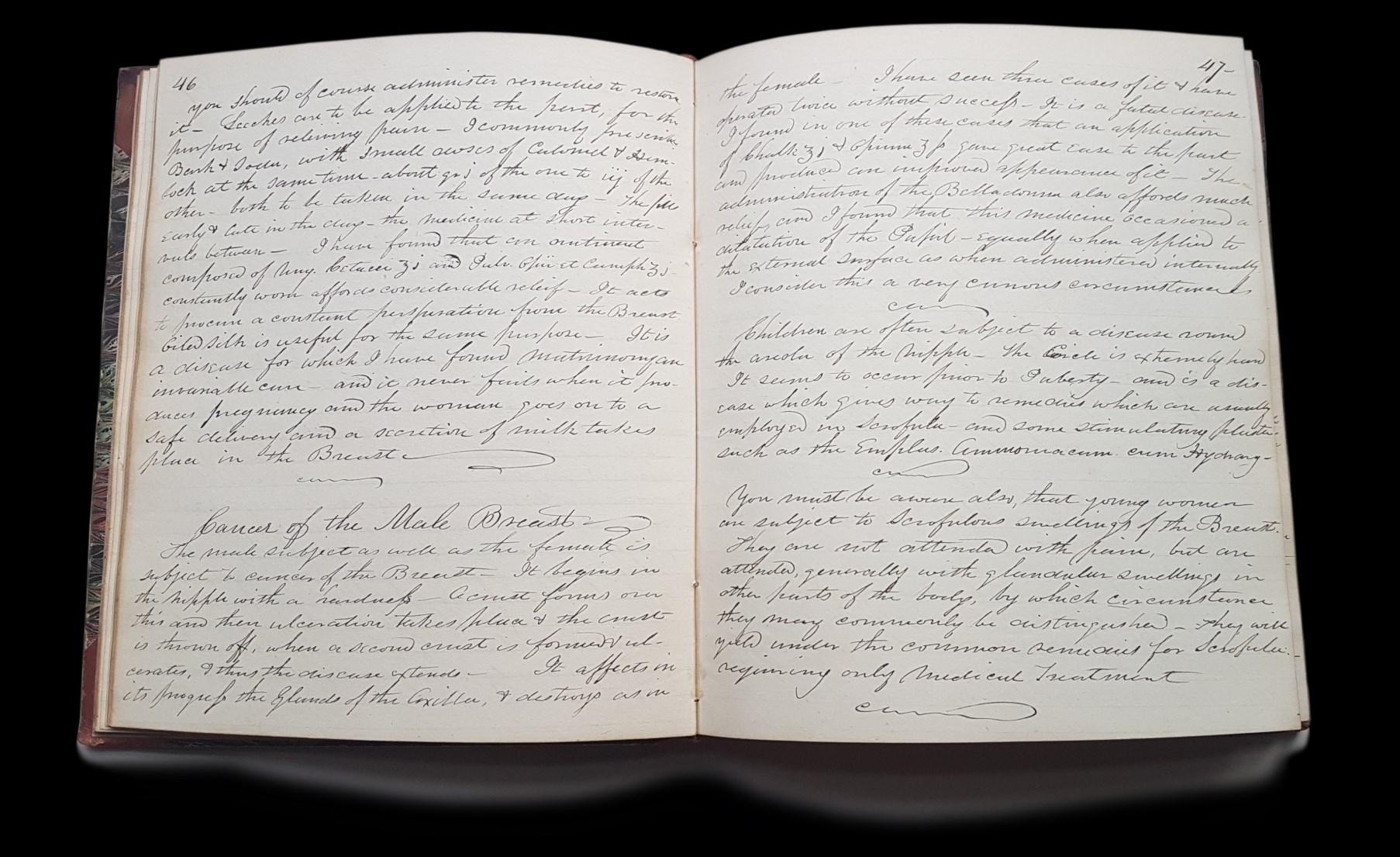

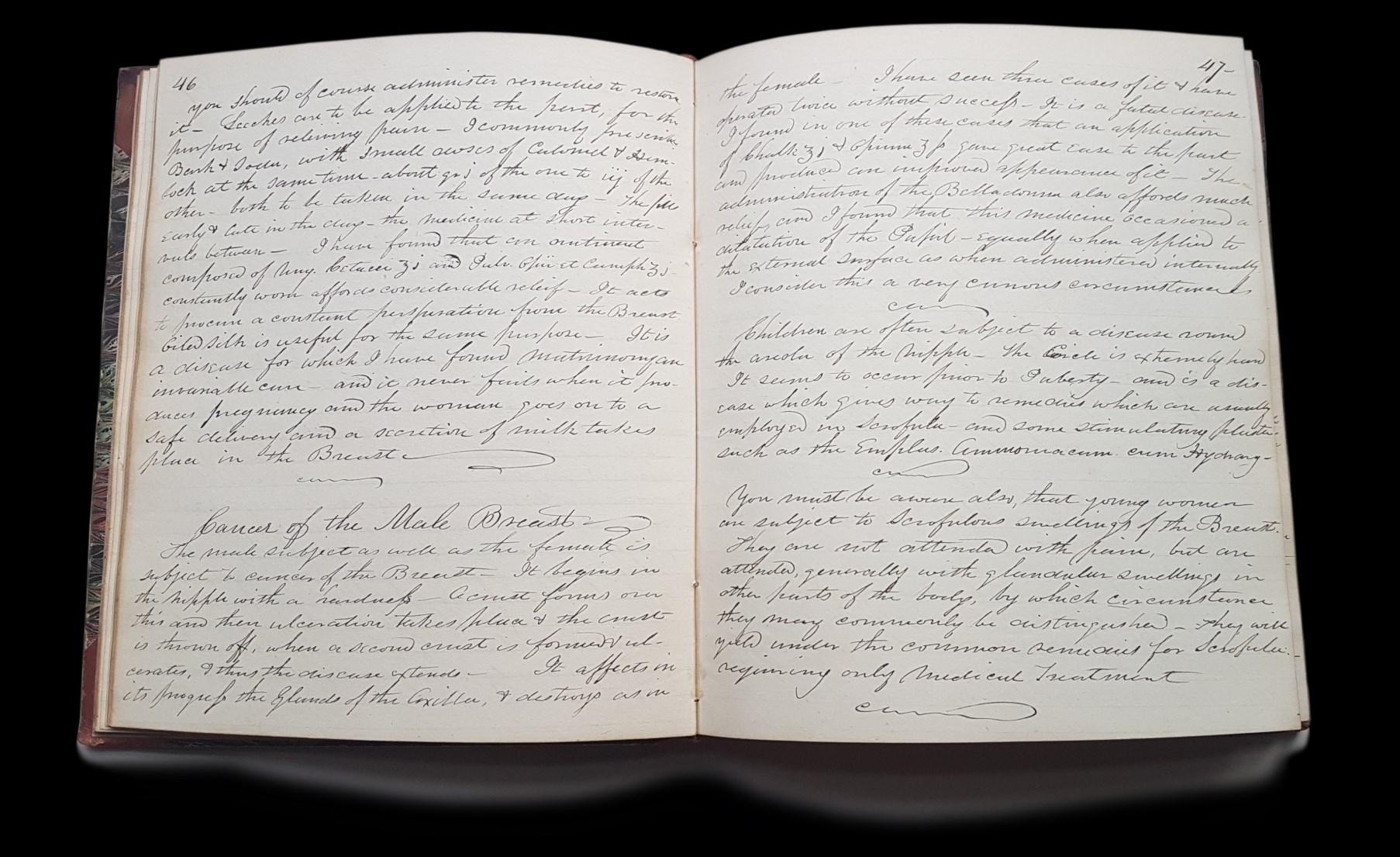

[CROSBY, Dixi (1810-1876); HALE, Safford Eddy (1818-1893)] Manuscript lecture notes taken by Safford Eddy Hale at Dartmouth Medical College in Hanover, New Hampshire, on venereal disease and urology, from lectures delivered by Dixi Crosby in 1840. [Circa 1840.] Half calf, marbled boards, rubbed. Small quarto (207 mm x 180 mm x 22 mm). 240 (numbered pages), [2, index].

¶ These lectures were almost certainly delivered by Dixi Crosby, who was professor of surgery, obstetrics, and diseases of women and children at Dartmouth Medical College when Hale was enrolled. Crosby had been appointed chair of surgery there in 1838. “He dominated New Hampshire surgery for thirty years. His practice in Hanover was very large, many patients being attracted by the high reputation of the school, while the personal ability of the man spread far around.” (Kelly Burrage, Dictionary of American Medical Biography. pp. 268-270). Crosby was the first surgeon in the United States to be sued for malpractice, though he was found not guilty.

An inscription to the front endpaper reads “S. E. Hale / Elizabeth Town / N. York”. Safford Eddy Hale was born in Chelsea, Vermont and attended Dartmouth Medical College graduating in 1841 and setting up a practice in Elizabethtown, New York the following year. He served as secretary of the Essex County Medical Society for several years and as its president for a term

The subject headings include hydrocele, diseases of the breast, irritable swellings of the breast, diseases of the testicles, fungus hematodes, chronic enlargement & abscesses of the testes, gonorrhea, stricture of the urethra, abscesses of the lacunae, spasmodic strictures, inflammatory strictures, irritable bladder, bleeding from the urethra, inflammation of the testicle, impotence, sympathetic bubo, gleet, gonorrhea in females, chancre, phymosis, chancres in females, bubo, secondary symptoms of the venereal diseases, venereal disease of the bones, venereal ophthalmia, of the effects of mercury, scrofula, and scrofulous enlarged glands, among others.

£650 Ref: 7907

SEVENTEEN

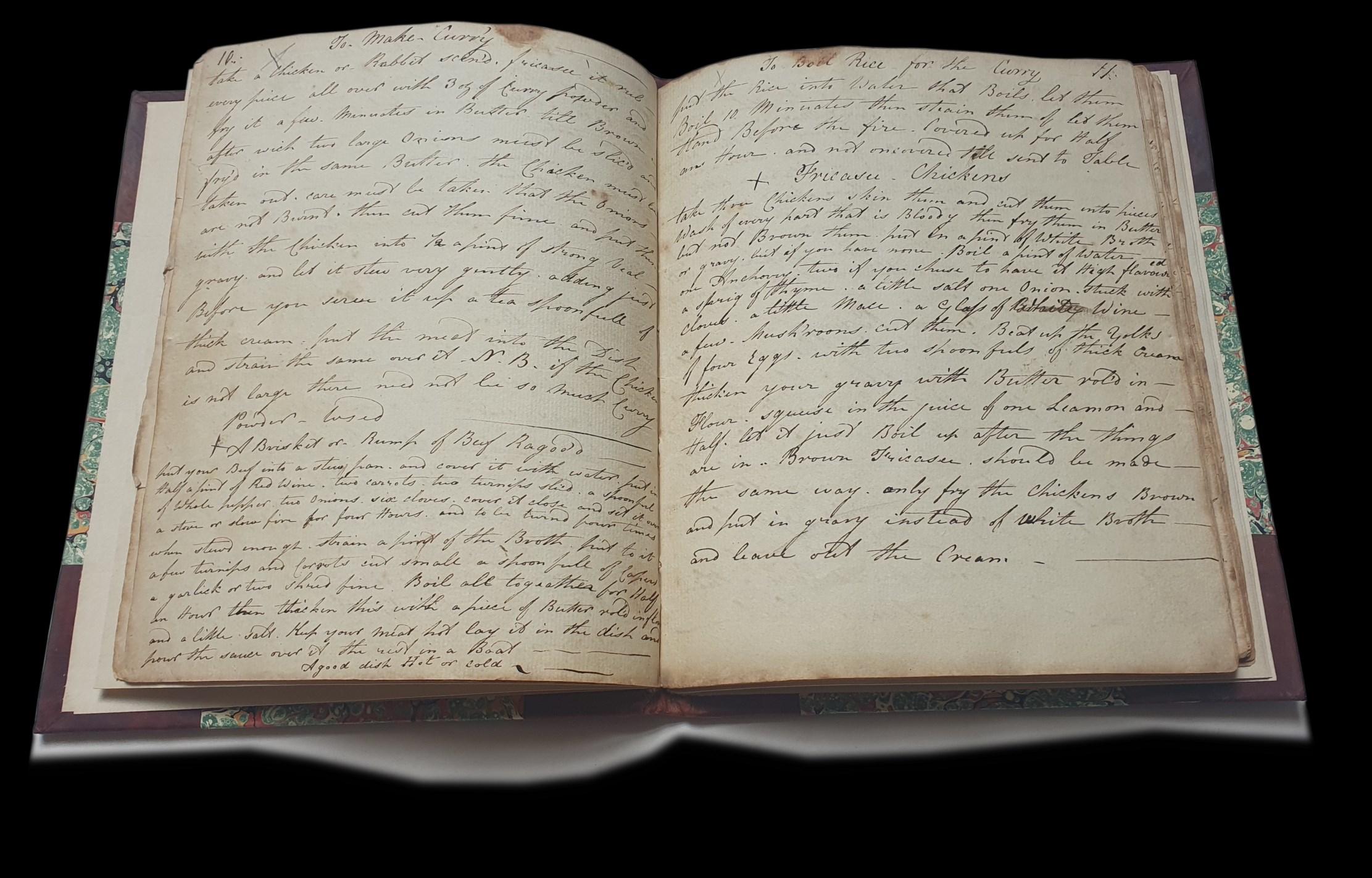

[CULINARY RECIPES] Early 19th-century manuscript book of culinary recipes.

[Circa 1810]. Quarto (204 x 70 x 17 mm). Approximately 97 text pages (of which 11 are pasted in recipes), 12 blank leaves. Vellum-backed marbled boards. Stitching broken, text block loose in biding. Boards heavily worn, some spotting to text.

¶ A note to the front paste -down reads “My Mother’s approved receipts” but this notebook is written in multiple hands. managing a household are written from the back. Recipes include “Shrewsbury Cakes”, “India Pickle”, “Fruit Acid” and “Diamond Cement” The volume also contains calculations for budgeting and managing a household, such as a sum for “the value of 152/2 Gallons of Brandy”. Dispersed throughout the calculations are a few household recipes, such as one “For French Polish”. The recipes have clearly been used, with those found unsatisfactory crossed through or labelled “Bad Bad”. Most of the recipes are unattributed, but a few are meticulously attributed to on the Art of making Wine by Macculloch 2d Edition”, complete with the publisher’s details.

£400 Ref: 8138

EIGHTEEN

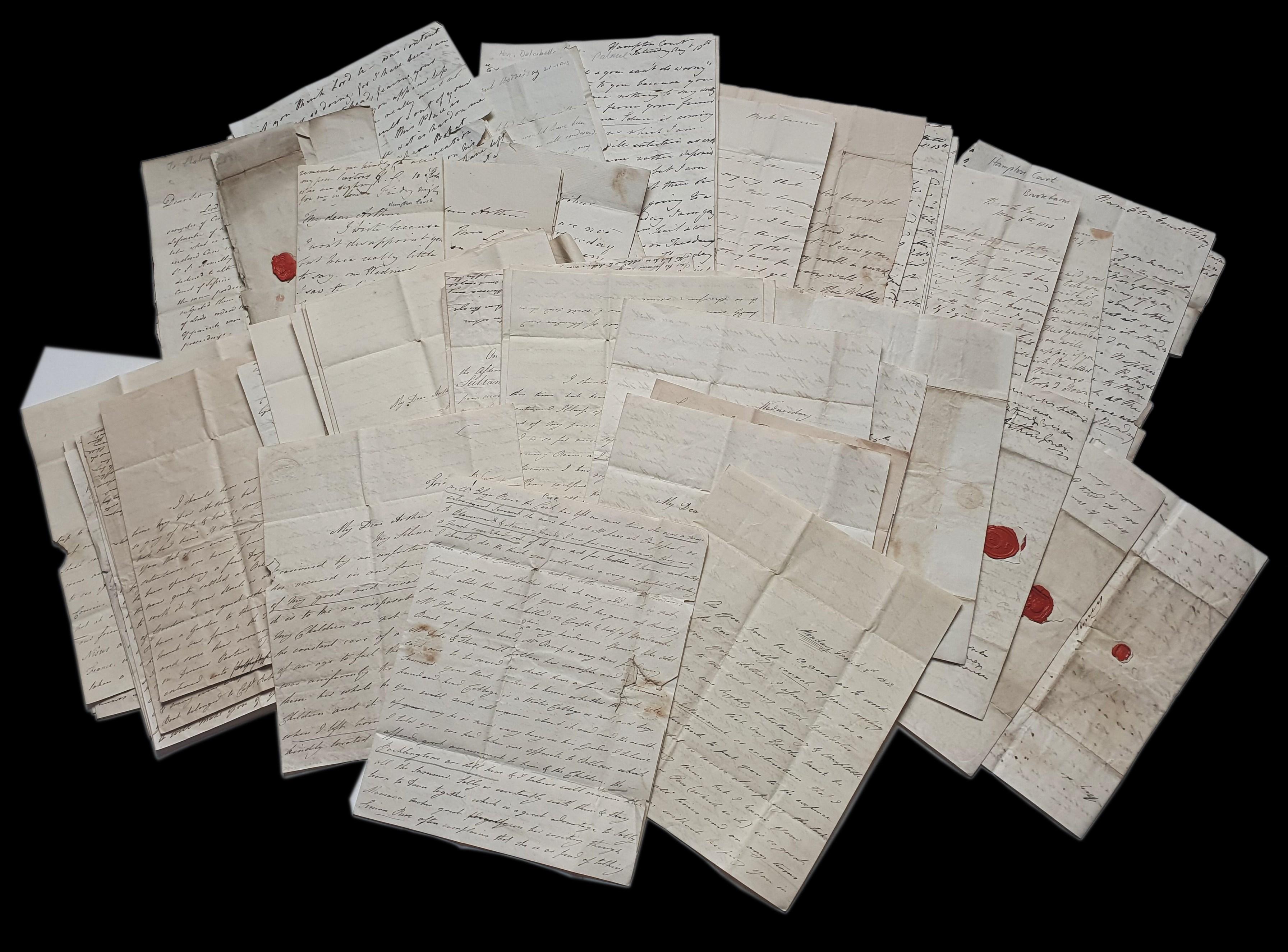

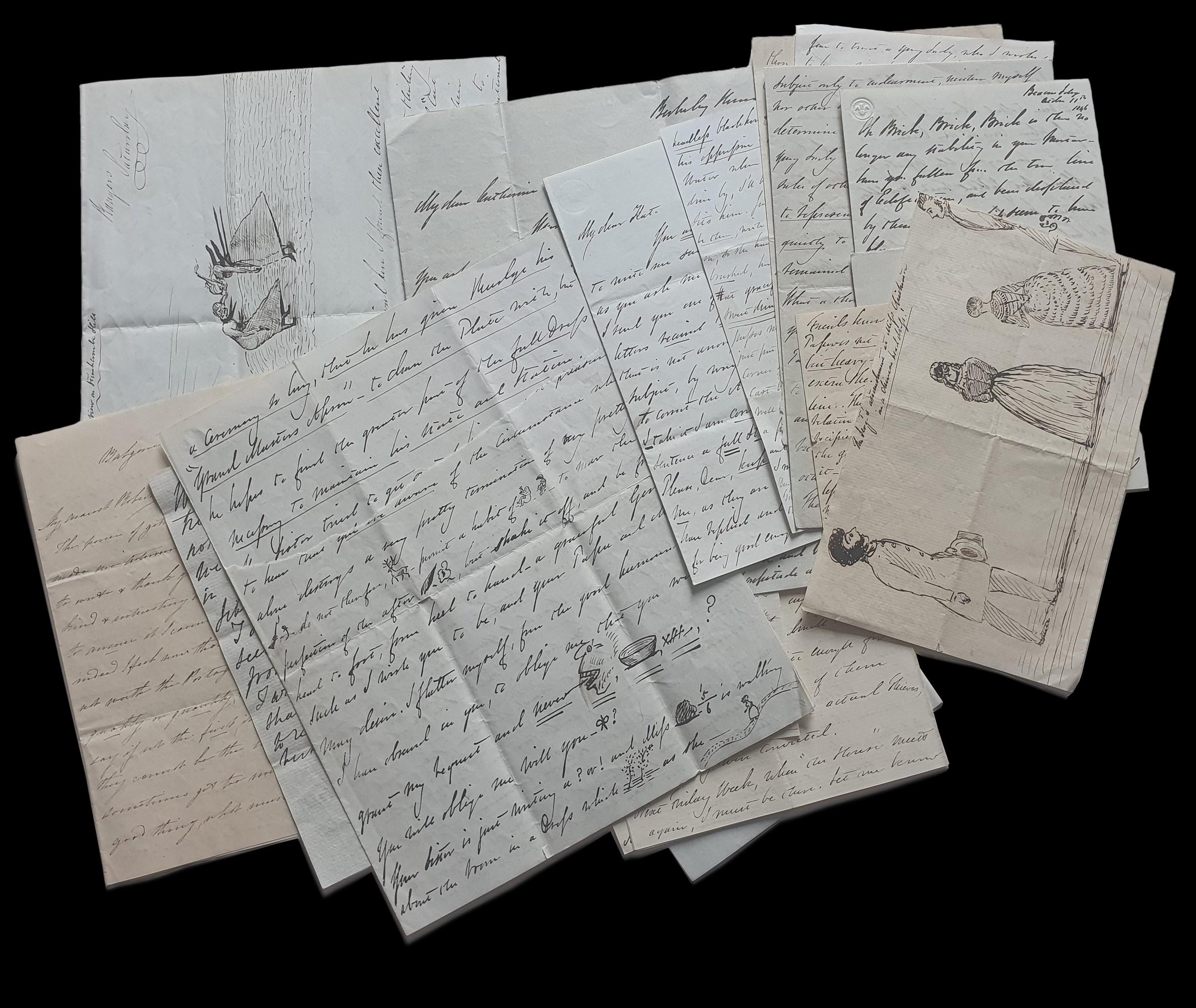

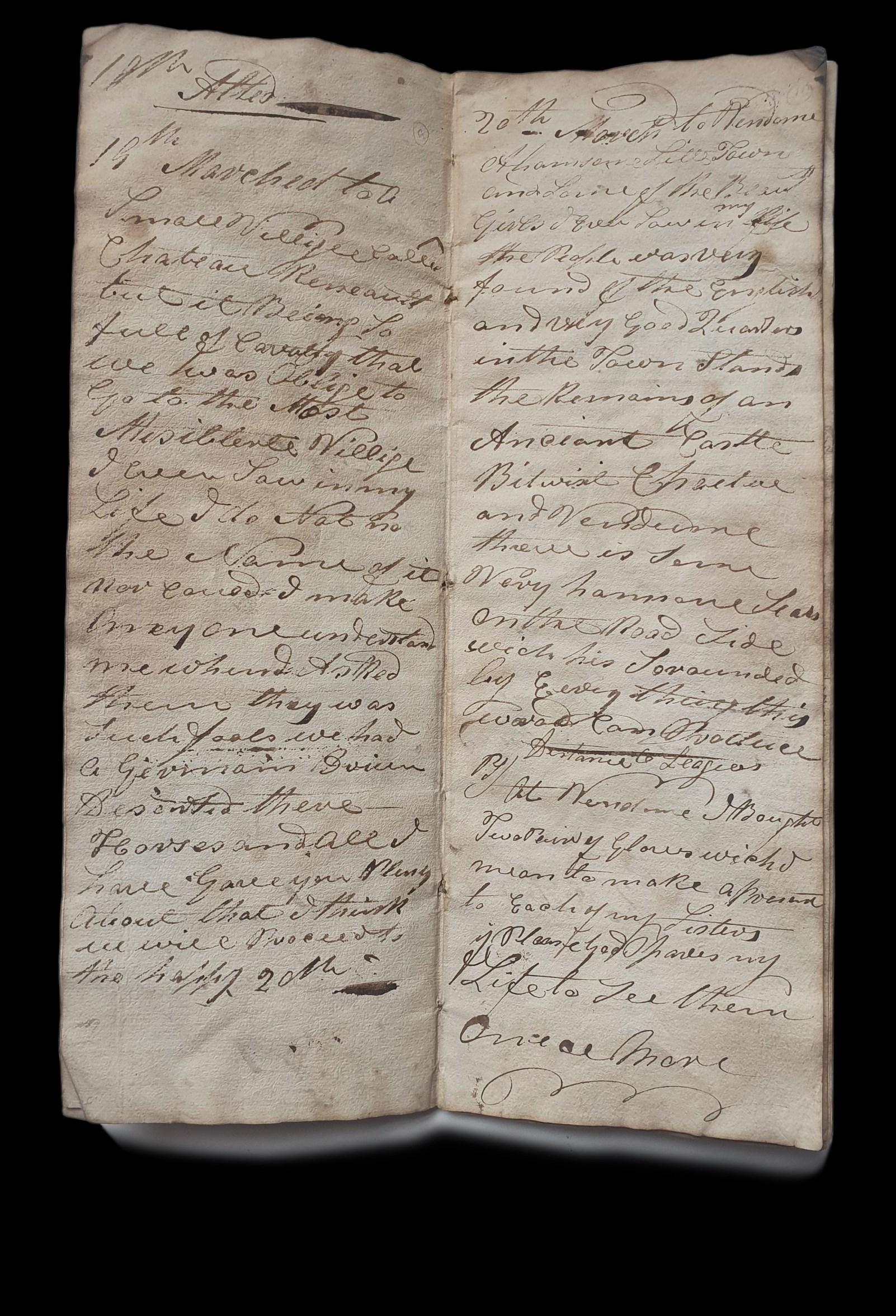

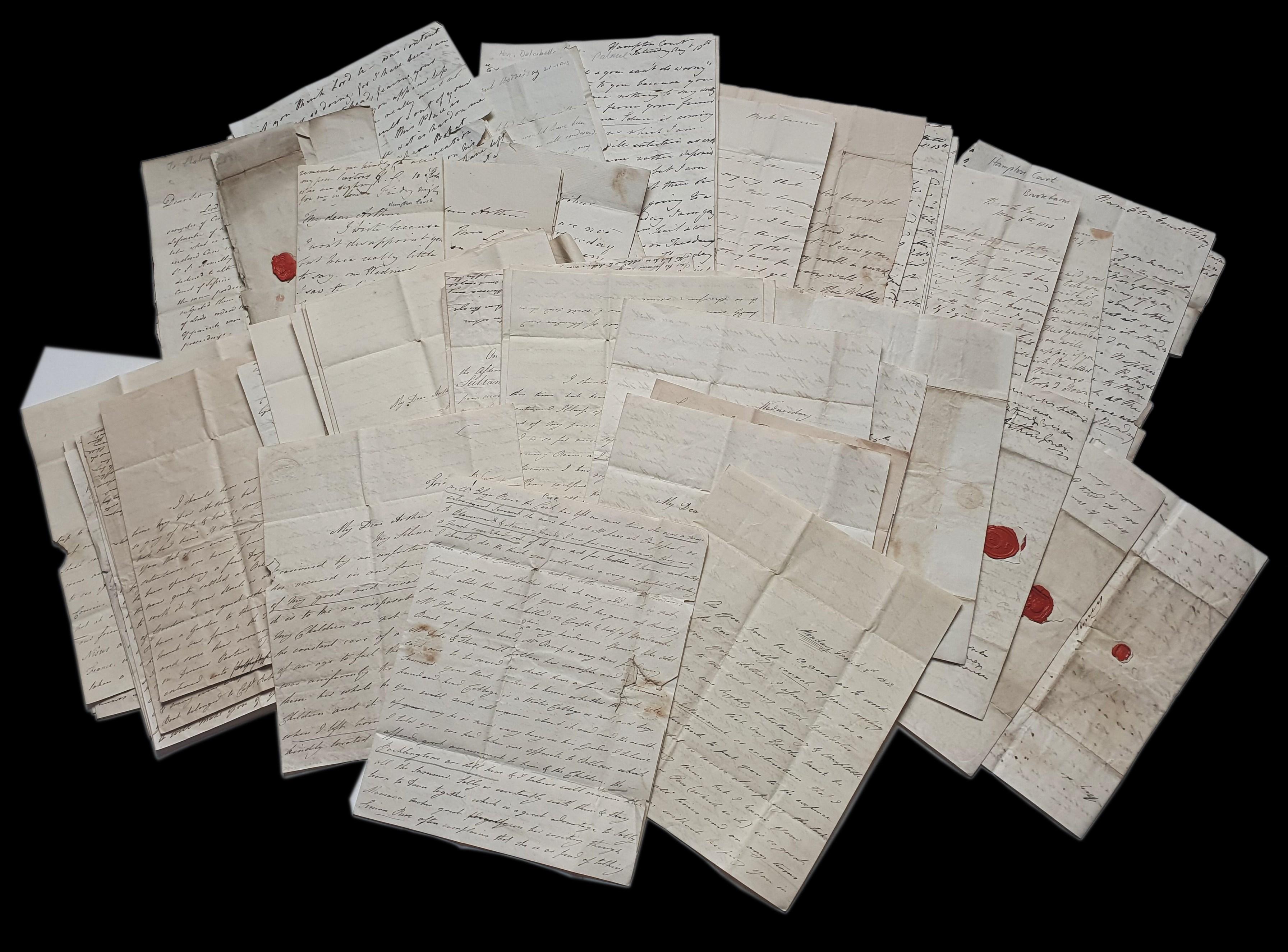

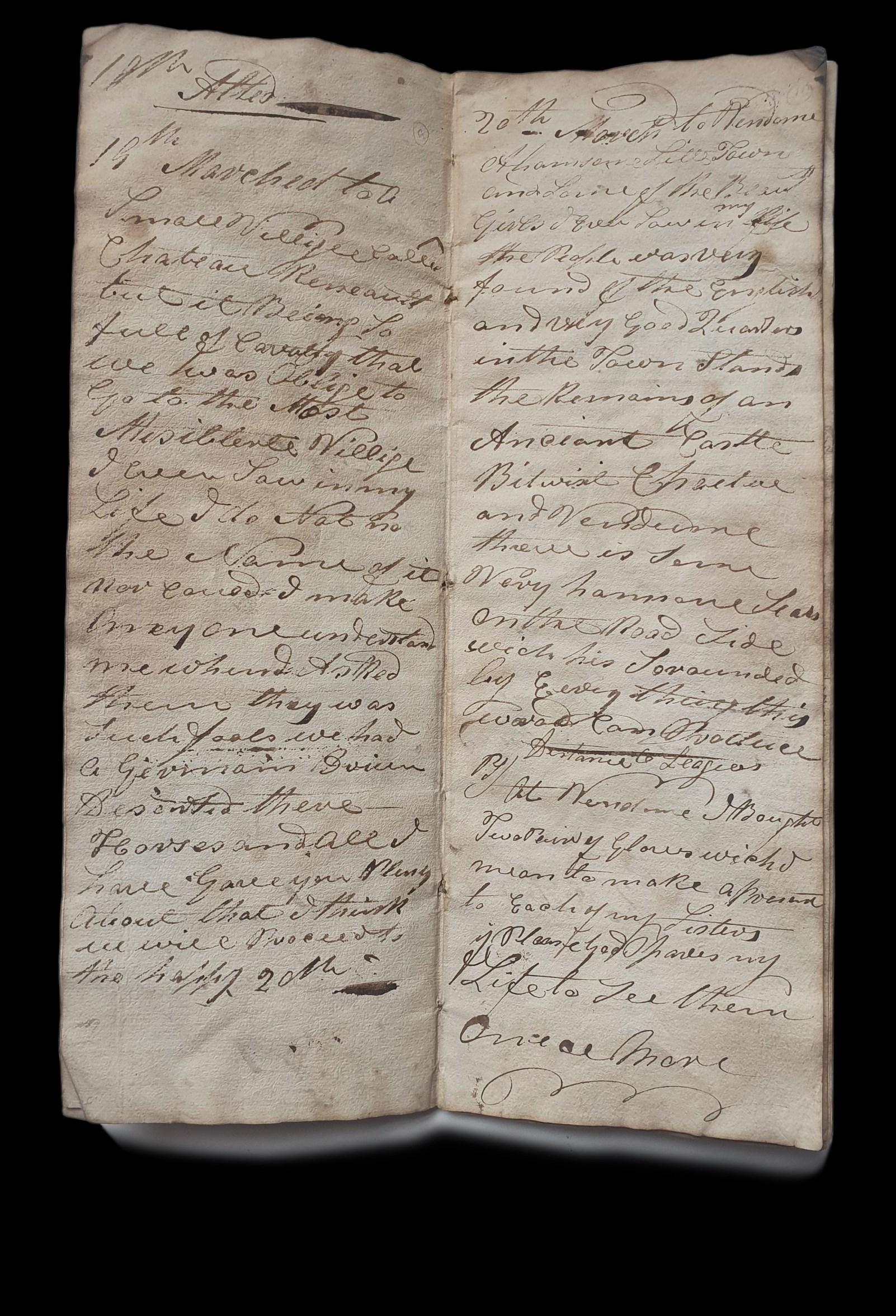

[JONES, Sarah (1768-1849); EDEN, Arthur (1793-1874)] A collection of correspondence addressed to Arthur Eden.

[Circa 1807-1813]. 65 letters, a few octavo, but mostly quarto. Folded for posting, some with address panels, and a few with seals.

¶ This collection comprises correspondence to Arthur Eden (1793 1874), later to become Assistant Comptroller of the Exchequer and Deputy Auditor of Greenwich Hospital. He lived with his second wife Frances Baring at Harrington Hall, Spilsby, the inspiration for “the Eden where she dwelt” in Tennyson's poem ‘The Gardener’s Daughter’.

The largest portion of this collection is the correspondence from his aunt, Sarah Jones (née Webber) (1768-1849), whose engaging collection of 37 letters run to some 140 pages. Sarah Jones married into a Welsh family and has the dubious honour of being the likely inspiration for James Gillray’s satirical print, “Venus a la Coquelle or the Swan-sea Venus” of 28 March 1809. This parody shows “a middle-aged sea-green block of a woman” driving her sea-shell chariot across the waves. – supposedly an allusion to Jones’ public profile as “a celebrated whip, frequently seen in Hyde Park who made herself elegantly conspicuous by driving about in a smart chaise and pair”.

In this series of letters, written in a clear hand, Sarah dispenses news and advice to her nephew. The earlier letters are addressed from “Belle Vue” (c.1807-9) and afterwards from “Hill House” in Swansea (c.1810-3). She touches on domestic topics including her dogs, her husband’s hunting, and news of friends, neighbours and family (such as “the sudden Death of Mrs Dixon who apparently in perfect health dropped off her Chair whilst at Dinner on Wednesday last & instantly Died”); after her move to Wales, she sometimes describes both dogs and children as “Rustics”. She often seems beset by melancholy (“I suffer’d materially in my health & spirits by great Anxiety & Afflictions two years since & I lost much of my good looks”) and preoccupied with the bad health of her husband (“my whole time has been taken up in nursing him”), but often articulates her thoughts with a certain liveliness (““Thinks I to myself”, Arthur is very angry with me”).

NINETEEN

Sarah is particularly exercised by troubles with servants: “Our man William Edwards”, she reveals, “turned out a great rogge”. She goes on to recall that “we placed so much confidence in him that he managed every thing in the way of Marketing, Bees, Coals, &c in every article of which he cheated us most grosly, nor did he content himself with this but he used to fill his Pockets with Bread Meat &c” and “Eliza Pierce the Cook has left us some time she was a most extravagant Servant she now ). In another letter she mourns “the Death of my good and invaluable Servant Sudden […] an “3 youngest Children”, who “still fancy she is Ill in the House”.

If this collection is anything to go by, Sarah’s husband, Arthur Jones (1768-1842) was a less frequent correspondent. He contributes four letters, which also cover domestic matters (especially their dogs), but with less vivacity than his wife, and in a comparatively untidy hand.

There are also 25 letters to Arthur Eden from his side of the family, including 10 from his sister, Lady Dorothy (Dora) Moore (née Eden) (c.1790-1875), whose emotional openness is often on display. She tells her brother:

“I have suffered a great deal since I last wrote to you […] If I don’t give vent to my grief my heart bursts, you will imagine my sufferings”. Her deeply felt experience of life has its consolations, as for example when she declares: “I think it is impossible for any body to love another better than I do Graham […] I sometimes think of him with wonder that a man can be so perfect”

Dora is well read, judging by her reference to Adam Smith’s idea of the “impartial spectator” or “man within” which is central to the philosophy in Theory of Moral Sentiments. She writes: “I am very sorry that you d d(?) with Eliza however the wisest cannot always command the impulse of the moment. & I & you “the man within” will forgive you if you promise us not to ere again. I like that expression of Smith’s “the man within” it is so expressive, there is something so dignified in it [...] there can be no real misery when the “man within” is satisfied”.

These letters represent one part of an extensive social and familial network, and give a more realistic portrait of Sarah Jones than the imperious figure parodied by Gillray. Moreover, since we have no corresponding replies from their recipient, the voices are predominantly female, a fact that nicely upends the usual state of affairs in matters historical.

£1,750 Ref: 8114

TWENTY

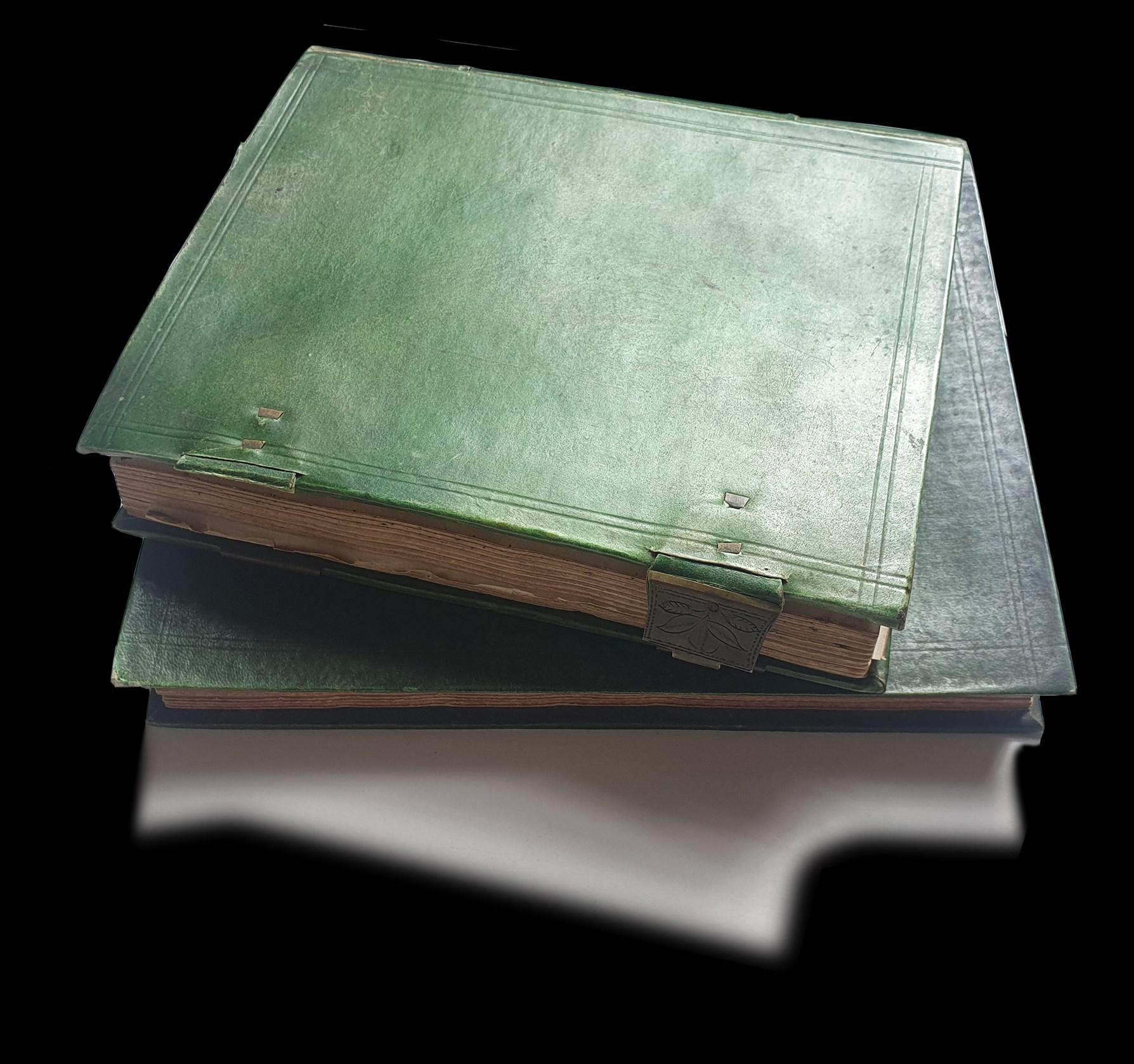

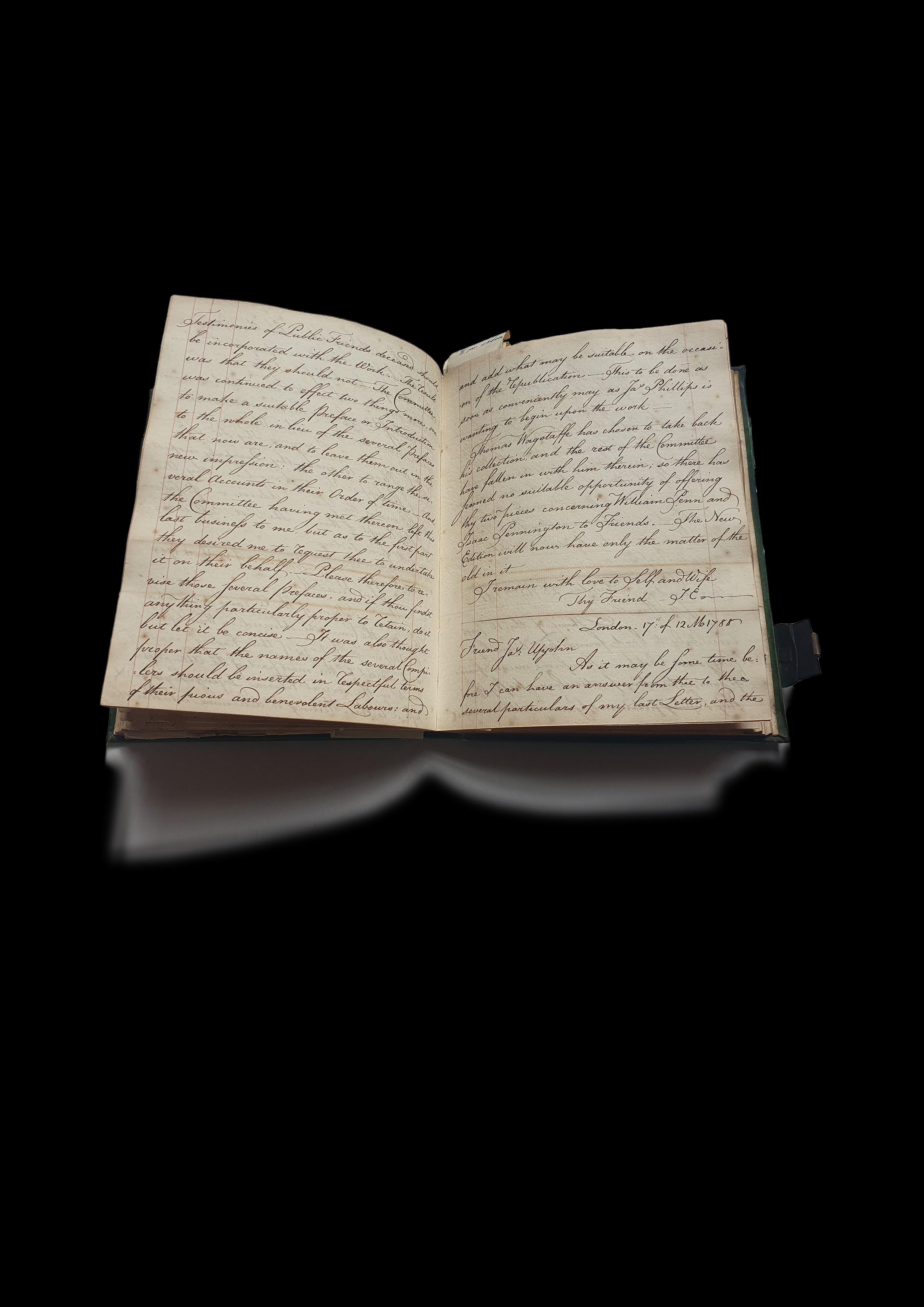

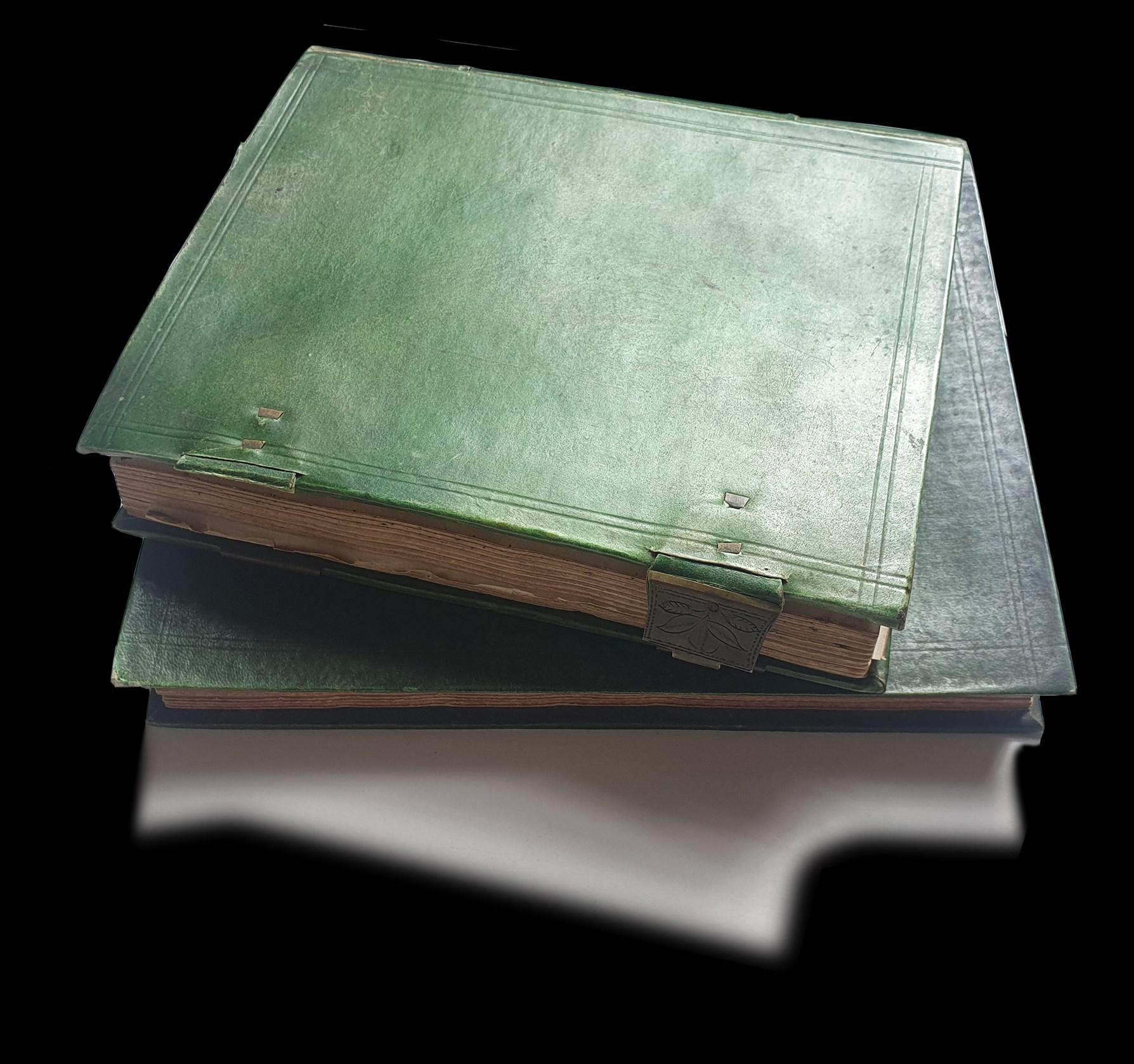

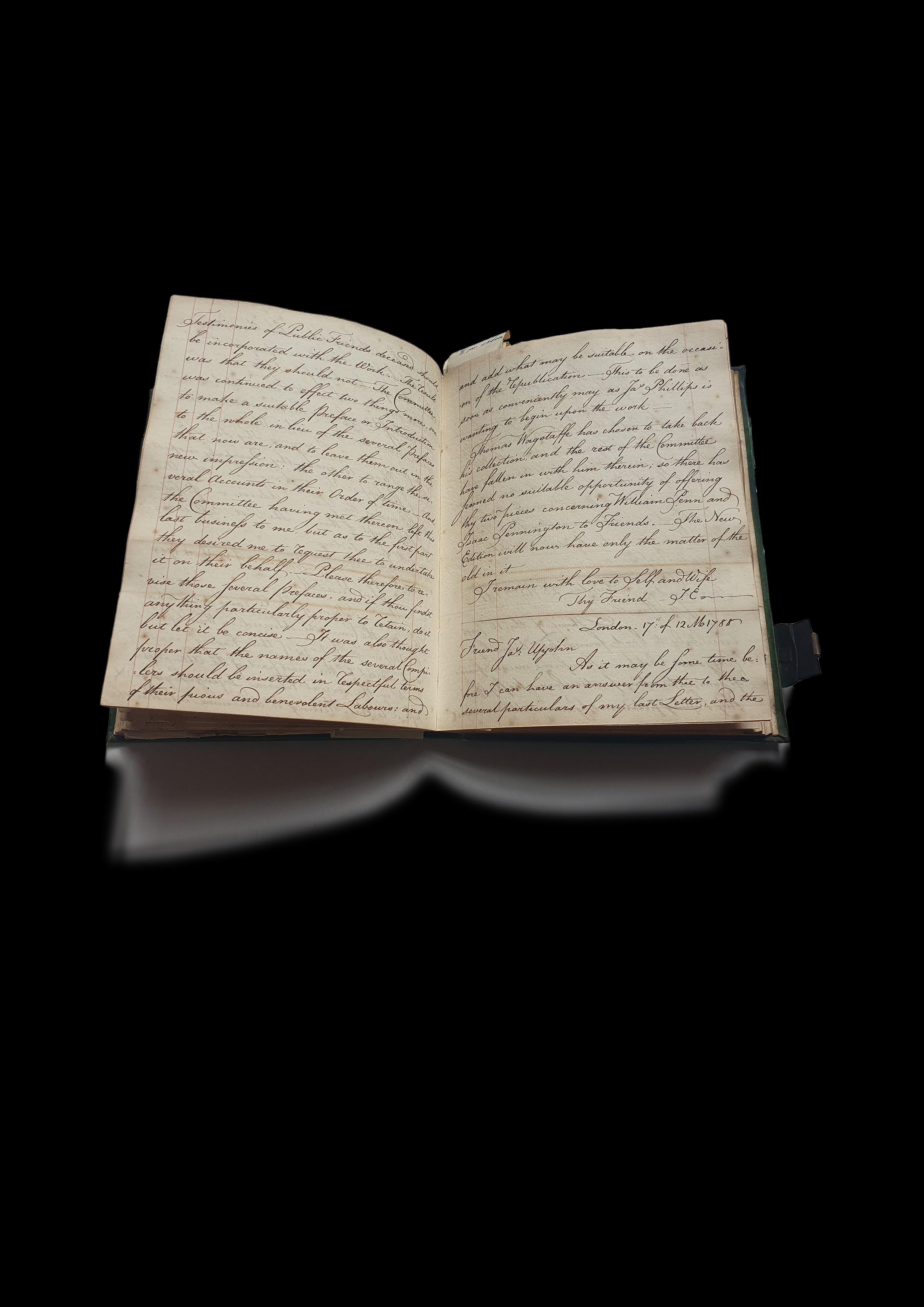

ELIOT, John (1735-1813). Two 18th-century manuscripts, comprising letter books and accounts [Circa 1780-88]. Folio and quarto volumes. Contemporary, green-stained vellum bindings.

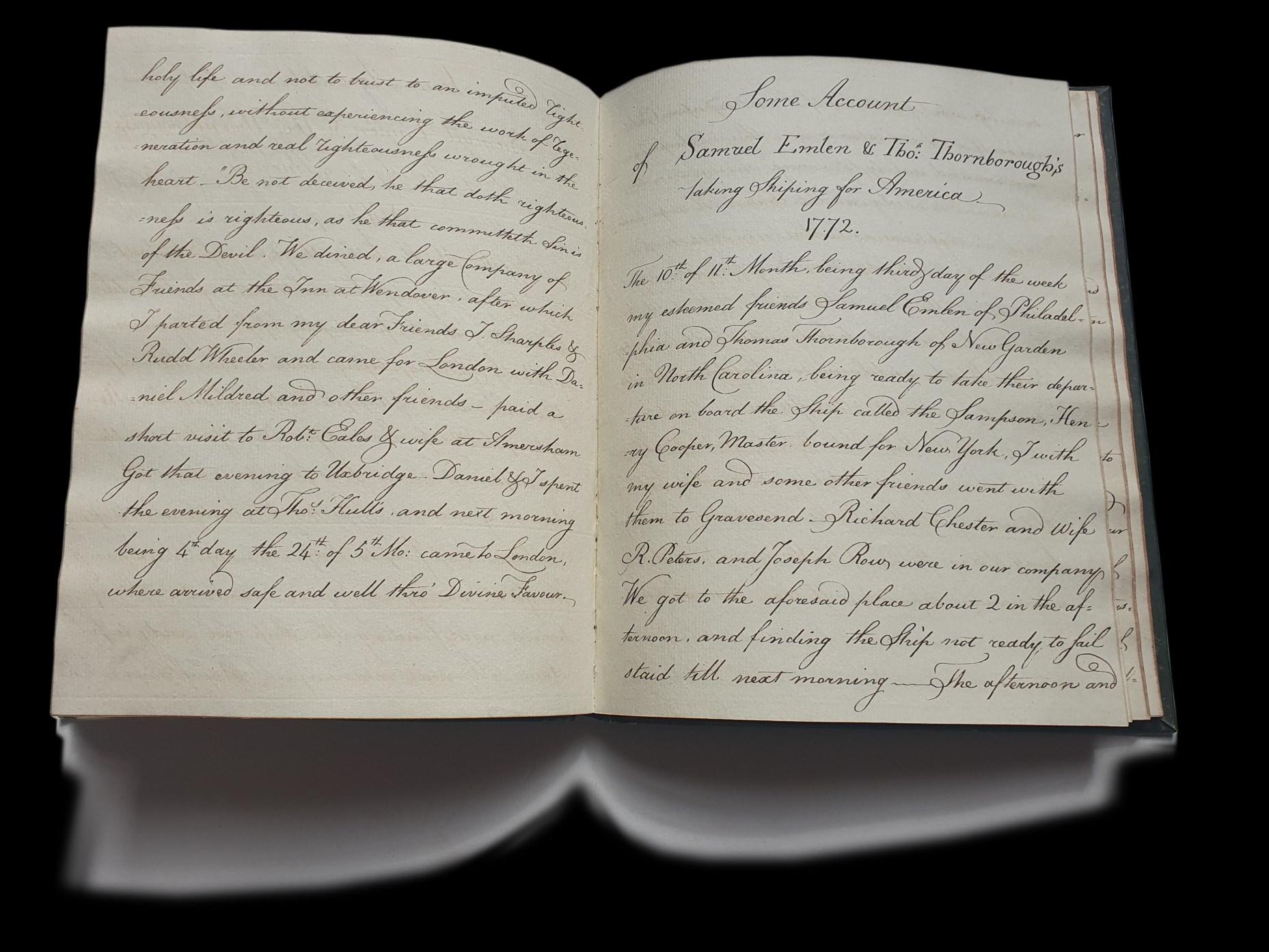

[1]. [ELIOT, John]. Manuscript fair copies of “Letters from several friends to Philip Eliot” and a Collection of Journeys. [Circa 1780]. Folio (243 x 195 x 25 mm). Contents page and approximately 140 text pages (numbered to p.96), followed by 16 blank leaves.

Green vellum, initialled “J E III” in manuscript to front board. Written in the same neat, clear copper plate hand. Watermark: Fleur-de-lis above GR; countermark: C Taylor. (Haewood 1856, except countermark: I Taylor).

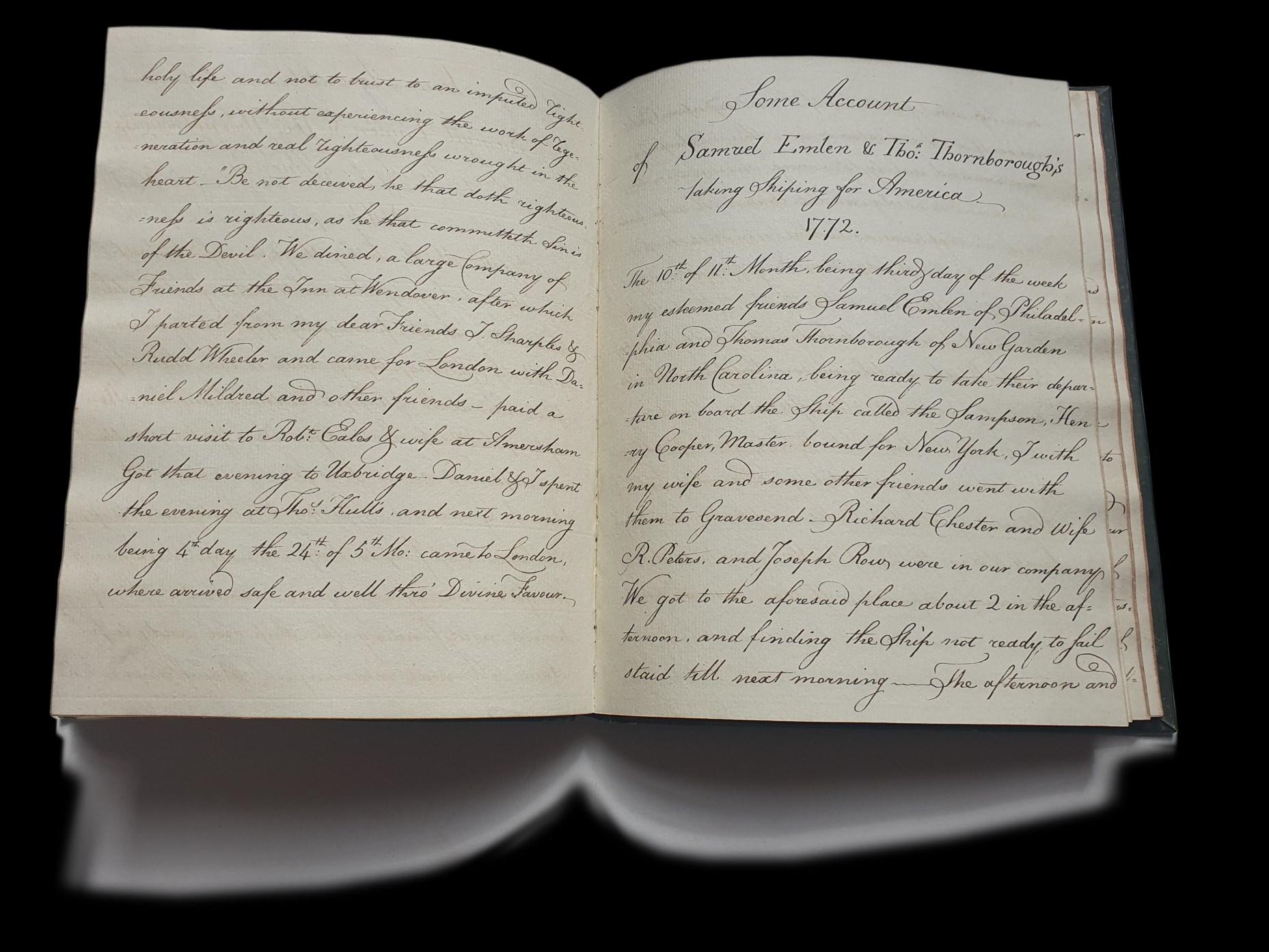

John Eliot’s manuscript fair copies of letters and accounts of journeys sent by Friends to his uncle, Philip Eliot between 1750 and 1779. Copies of 12 letters from correspondents including “James Gough”; “Claude Gay” (“While I was in France, I wrote to Friends of the Meeting for Sufferings, chiefly on Account of our few Friends in Jersey”); “Thos Whitehead”; and Accounts of journeys include those “to Friends in Holland. (The 7 of the 7th Month 1770)”

Portsmouth, Gosport & the Isle of Wight in 1779”

York Quarterly Meeting

[...] 22nd of 6th Mo: 1774”; and “to Thomas Whitehead at Reading. 16th of 3d Mo: 1771”

Also copied is “Some Account of Samuel Emlen & Tho Thornborough’s taking Shiping for America. 1772”

[2]. [ELIOT, John (1735-1813)]. Manuscript Letter Book and Accounts. [Circa 1784-89]. Quarto (208 x 164 x 30 mm). Text arranged dos-a-dos. Letter book: approximately 170 text pages; and approximately 60 pages of accounts (together 230pp, excluding a few blanks). Some pages excised at each end.

Green vellum, one clasp intact. Ruled in red for accounts. Probably a stationer’s book. Text and accounts written in the same neat, clear italic hand. Watermark: Pro Patria above GR. Manuscript inscription stuck in to paste-down: “Gulielma Briggins her book March 1734”. There are no other entries by her. The paper has a different watermark to the rest of the volume and has evidently been inserted, probably by Gulielma’s nephew and the compiler of this volume, John Eliot.

The manuscript compromises copies of over a hundred letters to and from John Eliot (correspondents are mainly Quakers, including Thomas Shipley, Ann Arch, John Trehawke, John Chamberlain, James Upjohn) between 1784 and 1789, together with his financial accounts for the years 1784 to 1788.

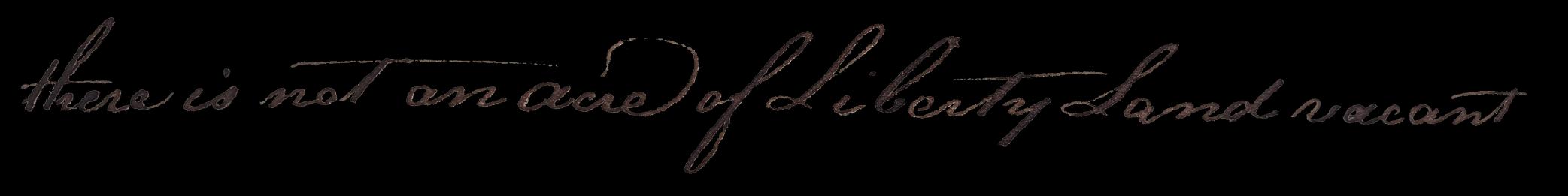

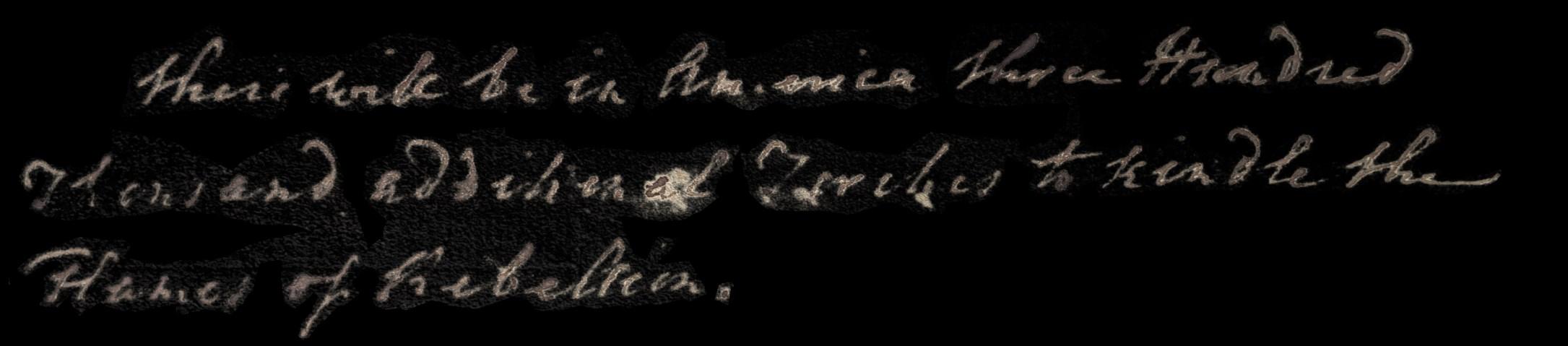

¶ 18th-century Quaker merchants stood in marked contrast to most of their peers. While so many of their fellow countrymen became rich through the slave trade, Quakers not only repudiated participation in the trade, but actively worked to achieve its abolition. Their development of ethical business practices, which grew out of their close connections, provided a model for English traders who preferred to see themselves as having ushered in the Industrial Revolution through sheer hard work and sound morals, rather than admit that the country had grown rich – directly and indirectly – through the trade in the lives of enslaved African men and women.