Since the advent of the deadly War on Drugs (WoD) when President Rodrigo Duterte assumed office in 2016, thousands of Filipinos have been subjected to several human rights violations (HRVs). Thousands of presumed drug users and dependents were killed, and many innocent people were caught in the crossfire, either as suspects or direct victims of the rampant killings and abuses which characterize this militaristic approach. Systemic violence was justified under the guise of eradicating the supposed “drug problem” of the country and relegated those involved with drugs as the “scourge of society.” Aside from the ongoing need for comprehensive and critical research regarding the ongoing killings and various forms of HRVs within WoD, the urgent need for services and proper avenues for those left behind by EJK, the “surviving families” of those who have been killed, has to be intentionally studied and collaboratively addressed. In addition to the traumatic experience of violently losing loved ones, they are forced to contend with the ill effects of trauma and different forms of systemic violence since the incident, and indefinitely as they live.

In this paper, various needs and effects on the biopsychosocial-spiritual aspects of ten surviving families during their grieving, coping, and recovery were examined and analyzed, together with exploring the assistance made available to them, their desire for seeking government accountability and legal justice, and their potential to organize themselves as human rights advocates. The study aims to not only shed light on the realities of these families, but also to outline ways for advocates and service providers (such as NGOs, CSOs, government agencies, and faith-based organizations) to work together in creating a holistic and multisectoral intervention that will facilitate the families’ full recovery, while seeking justice and growing as justice advocates.

With these objectives, the study employed a case study method for in-depth understanding of the ten cases with the use of various lenses and theories namely Strengths-based perspective, Human Rights-based perspective, Ecological and Social Systems theories, and Empowerment Theory. From the transcripts, similar and related concepts and ideas were drawn through data auditing and coding. Major themes were then created to encapsulate their experiences and identify the different factors present in the systems the families are a part of, their needs, the effects of the EJK, the assistance they received, and the potential roles in organizing among surviving families and partner organizations. On the other hand, structured written interviews

Abstract

were given to three organizations who are known and established to give various assistance to the EJK surviving families in order to know their strategies and best practices being implemented. All of the findings were then used to inform the creation of a referral pathway or a biopsychosocial-legal framework that could hopefully benefit the families and those who wish to provide structured assistance based on the grieving, coping, and recovery processes that the EJK surviving families went through.

The results of the research have several implications to both theories and practice. The summary is as follows: first, EJK survivors across different research all experienced drastic changes to their biopsychosocial well-being after the incident; however, there is a lack of literature exploring the psychological and spiritual changes to these families. Second, there is a need to explore not only the immediate needs of the families after the incident happened, but also their needs even months or years later as the EJK brought irreversible and long-lasting effects to their lives. Third, the micro, mezzo, and macro systems and the biopsychosocial factors involved in these systems that the families are a part of, need to be explored during their grieving, coping, and recovery process, because the impacts of the EJK and the survivors’ needs should not only be the basis of intervention. Fourth, this research affirms the need for a continued and sustainable provision of psychosocial services, support systems, and safe spaces for the survivors which aid them in their journey to healing, recovery, and their seeking for justice. Fifth, survivors are willing to pursue legal actions if only their basic and survival needs are met and resolved, and that the political climate of the country is not riddled with impunity, thus allowing for safe legal-seeking advocacies. Sixth, there is a lack of documentation and exploration on the legal processes that these surviving families go through; thus, this aspect needs to be explored especially for when the families decide to pursue legal justice. Seventh, there is a lack of literature exploring the potential of the EJK survivors to organize their own group as human rights advocates. Last, a lack of provision on different needs such as medical, economic, educational, and psychosocial needs still remains a challenge for the families.

Acknowledgment

Gratitude abounds to all those who have contributed in making this research and advocacy work truly meaningful. Much is to be done for human rights and the empowerment of communities and families who have experienced extrajudicial killings (EJKs). But with such a supportive and inspiring network of co-advocates and mission partners, we believe that true healing and empowerment are steadily within reach of marginalized communities and that of our nation.

We extend our gratitude to Prof. Jowima “Jowi” Ang-Reyes, Ph.D., our research consultant and loving mentor throughout this challenging journey. Through her guidance, we were able to sift through a myriad of processes and feelings associated with rigorous research amid a pandemic, and with emotionally-laden topics such as the ongoing journeys of surviving families and the ongoing “war on drugs.”

We are thankful to our leaders, colleagues and friends from IDEALS: Sir Egad Ligon, our executive director, for trusting us with this feat and enabling us to learn from his creativity for our shared advocacy; Sir Joey Faustino and Atty. Gettie Sandoval, members of our board of trustees, eager supporters, and esteemed human rights advocates within their respective fields; Atty. Ansheline Bacudio, our supportive and courageous Human Rights program manager; Atty. Carlo, Ms. Alenah, and Ms. Bea for their research and technical writing skills and advice. We also extend our fond appreciation to our other colleagues from IDEALS: Red, Lian, Tuesday, Jill, and Nel – your contributions and friendship enabled us to make our research more comprehensive and well grounded. Furthermore, the research team wishes to express its gratitude towards the entire IDEALS team, well spread out across Mindanao, Mindoro and Metro Manila – we honor your dedication and work “para sa bayan!” (for the nation!)

In connection to our work, we are indebted to the generosity of our partner funding organizations who share in the mission of human rights, democracy and social justice across borders. For this particular project, we are grateful to the National Endowment for Democracy, for its generous support towards all the costs associated with the implementation of “Empowering and Building Resilience Among Victims of Extrajudicial killings and HRV Survivors,” simply referred to as “BRAVE,” of which this research is a vital component of the project.

We remain grateful to all our organizational partners and friends who joined us last 30th of July during the launch of our research. We look forward to the next collaborative steps with you!

We are ever grateful to the hardworking and courageous team members of our partner organizations, Commission on Human Rights Region IV-A, PAGHILOM and Project SOW, whom we have directly worked with for data gathering and processing.

Lastly, we find much meaning and gratitude to learn from our 10 women interviewees, five from PAGHILOM, and five from Project SOW. These 10 women continue to face the challenges of their vulnerable state as they advocate for human rights, and justice for their departed loved ones who have been kiled through EJK. Through their heartfelt sharing of grief, vulnerability, generosity and love, we can only come out as more empathetic and dedicated human rights advocates.

Charmen Balana

KZ Briana

Aloe Pagtiilan

Christine De Leon

Raevene Morillo

When the dust finally settles on the current administration’s war on drugs, it is not just going to be the number of deaths and extrajudicial killings that will remind us of this dark period in our history-- but vivid images of thousands of families the victims had left behind, and other lives that were irrevocably changed by the chilling drug war. They shall serve as testimony of this administration’s terrible legacy.

While it may be difficult to uncover the full details of the Duterte administration’s bloody campaign against drugs, this study sheds light on crucial, yet largely overlooked aspects of the killings: the biological, psychological, social, and spiritual effects of the drug war to the mothers, wives, and children of the countless Filipinos who have been victimized by the campaign.

What this study reveals is truly alarming. First, it backs key findings of yet another IDEALS study that the war on drugs is, in fact, a war on the poor. It has also become apparent that this misogynist administration continues to further target and marginalize women and children, may it be directly or indirectly.

And as in the case of human rights violations of political origin, past and present, the war on drugs is no different. My heart always bleeds for the women and children, the families who bear the brunt of its ill effects-- for a lifetime.

Oftentimes, women who are suddenly forced to take on the role of breadwinner and solo parent after a loss are made even more vulnerable given their economic and educational incapacities and limitations. Their children are introduced to the culture of violence and, even more alarming, show signs of following the thread since many vow to avenge their father’s death. In addition, families become broken as many choose to uproot themselves due to safety concerns, or misunderstandings arise between members as they struggle with their psychological wellness.

On the other hand, the study also confirms the strength and resiliency of Filipino families who continue to live for their loved ones despite the experience, and choose to move forward and recover from their trauma, with the hope that their families and other community members will be spared from the same pain and injustice.

foreword

Moreover, we see from their perspective how the wider backdrop of the struggle for truth and justice can be far from the limited version modern society portrays it to be. For many of them, justice is more spiritual or dependent on their own healing, especially given their misgivings with our broken system and the current administration.

Still, many families continue to hold on to the hope of achieving true accountability in the future.

We in IDEALS, together with our partner organizations, dare to see through their lenses. We join them in their fight for restitution and reparation in the context of transitional justice. Through this study, we are hopeful that we are at the least able to provide the families a platform to raise their voices and promote awareness on the issue.

Let me also take this opportunity to thank our staff, especially the Networking, Advocacy, and Social Workers team who took the lead on this research amid the current pandemic, and exhibited great dedication, empathy, and compassion for the families in the course of their work.

We want nothing more than to have this study be used by others to help put a stop to tyranny and state violence. Though painful, the narratives will hopefully act as a catalyst to open the eyes of the greater public and make them realize the simple fact that no one should have to suffer the same fate as those in our case studies -- not for the war on drugs, or any excuse at all.

Once again, we resonate the call: Stop the Killings.

Joey Faustino Board President, IDEALS

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 Statement of the Problem 5 Scope and Limitations of the Study Significance of the Study 8 Definition of Terms 9 CHAPTER 2: REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE 14 The Incident 14 Narratives of EJK survivors and their families 14 The Aftermath 17 The biopsychosocial-spiritual well-being of survivors 17 Economic Impacts 18 Social Impacts 19 Biological Impacts 22 Psychological Impacts 22 On Psychological Impacts: A Closer Look at Grieving and Trauma 25 Coping and Recovery 33 Coping: What Makes Their Coping Harder 33 Coping: What Makes Their Coping Easier 37 Recovering: What Makes Their Recovery Harder 38 Recovering: What Makes Their Recovery Easier 40 Human Rights Organizations Providing Assistance to HRV Surviving Families 41 The Journey Forward 44 Experiences with Justice and Claim-making 44 Hindering Factors Affecting Their Desire to Seek Accountability 45 Facilitating Factors Affecting their Desire to Seek Accountability 47 Looking forward: what do they hope for in the future? 48 Potential to Organize 49 Synthesis of the Literature Review 52 Theoretical/Conceptual Framework 54 Social Systems & Ecological Systems Theory 54 Strengths-Based Perspective 55 Rights-based Perspective 56 Table of Contents

CHAPTER 3: METHODOLOGY AND RESULTS 59 Research Design 59 Case Studies 59 Profile of the Participants 59 Research Method/Data Gathering Procedure 61 Ethical Considerations 61 Benefits of the Research 65 RESULTS 66 The Story of the Pajaro Family 66 The Story of the Acierto Family 74 The Story of Lou And The Children 80 Carol and Her Children’s Story 87 The Story of Tina’s Family 97 Joan’s Story 104 Claire’s Story 112 The Story of the Batislaon Family 118 The Story of the Lopez Family 128 The Story of the Ocampo Family 141 Demographics of The Participants 150 Profiling Of Organizations 157 CHAPTER 4: DISCUSSION 168 Objective 1 169 Biopsychosocial-spiritual Impacts 169 Biopsychosocial-spiritual Needs 175 Hindering Factors To Grieving 179 Facilitating Factors To Grieving 183 Hindering Factors To Coping 187 Facilitating Factors To Coping 192 Hindering Factors To Recovery 195 Facilitating Factors To Recovery 200 Objective 2 208 Views and Meanings 208 Struggles 215

Roles and Processes 218 Objective 3 222 Hindering Factors To Seeking Accountability And Legal Reparation 222 Facilitating Factors To Seeking Accountability And Legal Reparation 224 Objective 4 228 Potential To Organize 228 Objective 5 & 6 238 Network Of Organizations, Programs and Services 238 Conceptual Framework 248 Implications 251 Biopsychosocial-spiritual Impacts 251 Biopsychosocial-spiritual Needs 251 Grieving-hindering 252 Grieving-facilitating 253 Coping- hindering 253 Coping-facilitating 254 Recovery-hindering 254 Recovery-facilitating 255 Views and Meanings 255 Potential to Organize 257 Provision of Assistance 258 Limitations 261 REFLEXIVITY 263 RECOMMENDATIONS 268 REFERENCES 272 ANNEXES 289

Abbreviations

INSTITUTIONS AND ORGANIZATIONS

ADMU Ateneo De Manila University

AKAP Pamilya Abot Kamay Alang-alang sa Pagbabago

APA American Psychological Association

CEFAM Center for Family Ministries Foundation

CenterLaw Center for International Law

CHR Commission on Human Rights

CHR IV-A Commission on Human Rights Region IV-A

DILG Department of the Interior and Local Government

DLSU De La Salle University

DOJ Department of Justice

DSWD Department of Social Welfare and Development

FLAG Free Legal Assistance Group

IDEALS, Inc. Initiatives for Dialogue and Empowerment through Alternative Legal Services, Inc.

MAG Medical Action Group

MANLABAN sa EJK Manananggol Laban sa Extrajudicial Killings

NASWEI National Association for Social Work Education, Inc.

NEDA National Economic and Development Authority

NHRI National Human Rights Institution

OHCHR Office of High Commissioner for Human Rights

OSG Office of the Solicitor General

OVP Office of the Vice President

PDEA Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency

PhilRights Philippine Human Rights Information Center

PNP Philippine National Police

Project SOW Project Solidarity with Orphans and Widows

SC Supreme Court

SOCO Scene of the Crime Operatives

SSDD Social Services Development Department

UN United Nations

UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund

UNODC United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

UP University of the Philippines

UPD University of the Philippines Diliman

TERMS

4Ps Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program

BRAVE Empowering and Building Resilience Among Victims of Extrajudicial Killings and HRV Survivors

CALABARZON Cavite, Laguna, Batangas, Rizal and Quezon

CI Counterintelligence Investigation

CICL Children in Conflict with the Law

COVID-19 Coronavirus Disease

CSO Civil Society Organization

DDS Davao Death Squad

EJK Extrajudicial Killings

FBO Faith-based Organization

GBV Gender-based Violence

HR Human Rights

HRVs Human Rights Violations

IGO Intergovernmental Organization

INGO International Non-governmental Organization

LGU Local Government Unit

MC Memorandum Circular

NCR National Capital Region

NGO Non-governmental Organization

OFW Overseas Filipino Worker

PFA Psychological First Aid

PIE Person-in-Environment

PPE Personal Protective Equipment

PSI Psychosocial-spiritual Intervention

PTSD Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

QC Quezon City

RSW Registered Social Worker

SAP Social Amelioration Program

SSS Social Security System

VAWC Violence Against Women and Children

WoD War on Drugs

WPP Witness Protection Program

The “War on Drugs” (WoD) is a costly global approach for many reasons. In addition to the degradation of lands serving as the source of raw material for drugs, death tolls continue to increase, and international drug syndicates have proven effective in instigating violence and financing conflict and arms. In addition to these unquantifiable losses, the cost of waging this war globally is pegged at least USD 100 billion a year (Cruz, 2019).

The international WoD can trace its history to national and international policies by two former US presidents. First, former US President Richard Nixon’s declaration in response to an increase in the diversion of Turkey’s opium for non-medical and heroin production, primarily for the consumption of the US market (Global Commission on Drug Policy, 2018). Throughout his presidency from 1969-1974, he labelled drug abuse as “public enemy number one” (Esquivel -Suárez, 2018). Through his anti-drug campaign, he increased the power of federal drug control agencies and encouraged measures such as no-knock warrants (Drug Policy Alliance n.d.). Prohibition was used to vilify dissidents and Black Americans by having marijuana associated with the antiwar left labelled as “hippies,” and heroin with Black Americans (Drug Policy Alliance, n.d.). Two presidential terms after Nixon, the presidency of Ronald Reagan from 1981-1989 expanded the WoD as shown in the increase of nonviolent drug-related incarcerations of 50,000 persons deprived of liberty in 1980, to over 400,000 in 1997 (Drug Policy Alliance, n.d.). Setting the tone for the global WoD, the following primary strategies appear: prohibition of use, eradication of the sources of drugs, and incarceration (Lero, 2019).

Though countries struggle in different ways, the dynamics of WoD often lead to developing countries experiencing troubling death tolls. For example, Mexico’s current death toll is at 61,000, when in 2015, it was documented to be at 55,000 (Castañeda, 2012). On the other hand, despite this longstanding war, an estimated 750,000 deaths per year across the globe are linked to illicit drug overdose, and more so to the various health risks connected with drugs (Ritchie & Roser, 2018). Further marginalization and poverty are immediate as communities are forced to leave their lands, which continue to bear the brunt of both militaristic and ecological violence. Recently, Colombians are further burdened by the use of drones by the Trump administration for aerial fumigation using toxic glyphosate on croplands (Esquivel-Suárez, 2018).

1

Chapter 1 Introduction

On the other hand, the WoD remains a lucrative business as it is inextricably tied with the unregulated though economically predictable black market. Currently, drug trafficking is estimated to reap USD 300 billion per year (Hidalgo & Vásquez, n.d.). The WoD is the militaristic and alternative iron hand of the drug trade. Though the black market in theory is unregulated, the law of supply and demand remains the main guiding principle. Initially, cheap raw materials available in developing countries such as cannabis and poppies are grown, processed, and then sold to high paying developed countries. Dried coca leaves sourced from the Andes and then initially processed would cost USD 385; it would increase in value to USD 2,200 in Colombia, and then could be sold in the US at a retail price of USD 122,000 (Hidalgo & Vásquez, n.d.). Simultaneously, paramilitaries are paid to facilitate the sourcing and transfer of these drugs (Esquivel-Suárez, 2018).

The Philippine context of WoD mirrors that of the international realm. First, as a developing country struggling with governance and accountability, its porous borders are ideal for the country to serve as both a source and transporter of drugs. However, due to its geopolitical proximity, its market, supply, and demand are primarily tied to China (Chalmers, 2016). While international arms producers earn from the WoD in other countries, drug syndicates, primarily Chinese, continuously earn from the Philippines despite the government’s highly publicized efforts in curtailing illegal drugs. In fact, two-thirds of 77 arrested foreign nationals for meth-related offenses were Chinese, while almost a quarter were Taiwanese or Hong Kong citizens (Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency [PDEA] cited in Chalmers, 2016).Current PDEA spokesperson Derrick Carreon even said, “It’s safe to say that the majority of the meth we have comes from China” (PDEA, cited in Chalmers, 2016). In addition, and similar to the international model, incarceration has also dramatically increased since July 2016, after President Rodrigo Roa Duterte, the main spokesperson of the Philippine WoD, was sworn into office.

Prior to becoming chief executive of the country, Pres. Duterte served as the mayor of Davao City for 22 years, never losing an election. He hails from a politically involved family, his father being a former governor of the Province of Davao, and his mother a known critic of the late dictator and former president, Ferdinand Marcos (Paddock, 2017 and Ranada, 2016). Currently, his eldest daughter, Sara Duterte-Carpio, and youngest son, Sebastian Duterte, respectively serve as the mayor and vice-mayor of Davao City; while his eldest son, Paolo Duterte, serves as the representative of the city’s first district (Bueza & Castro, 2019 and Jiao et al., 2019).

2

Pres. Duterte served as Davao City mayor for three terms from 1988 to 2016. From 1998, at least 1,400 (Picardal, n.d.) people were killed by the “Davao Death Squad” (DDS). Despite being considered a “model city” in terms of security, data by the Philippine National Police (PNP) shows that Davao has the highest murder rate from 2010-2015, citing a figure of 1,032 murder cases (Frialde, 2016) This notwithstanding, Davao had the highest murder rate and second highest rape rate among 15 large Philippine cities (Johnson & Fernquest, 2018). Of the reported 1,400 deaths, a majority were from marginalized sectors involved in the illicit drug trade as either drug users or pushers. On the other hand, there were cases of petty crimes such as cellphone snatching, theft, and gang membership (Picardal, n.d.). From this minimal and documented estimate, urban poor children and young adults make up 50 percent of the tally. On the other hand, despite Mr. Duterte’s outspoken hatred against drugs, there were neither drug lords nor powerful criminals “disposed of” by DDS (Picardal n.d.).

Shortly after the former mayor won his presidential election, an estimated 687,000 people across the country surrendered to the police due to their involvement with drugs (Johnson & Fernquest, 2018). For many, this seemed like the start of the fulfilment of Pres. Duterte’s campaign promise to “end the drug problem within three to six months.” The launch of “Operation Knock and Plead” (Oplan Tokhang) soon drew headlines:

“Forget the laws on human rights. If I make it to the presidential palace, I will do just what I did as mayor. You drug pushers, hold-up men and do-nothings, you better go out. Because I’d kill you,” he said at his final campaign rally. “I’ll dump all of you into Manila Bay and fatten all the fish there.” (Duterte, 2016 as cited in BBC News, 2016).

Due to the sudden surge of surrenderees, the government could not keep up. Out of 45 accredited drug treatment and rehabilitation centers in the country, only 16 were public, with a total capacity of only 5,300 inpatients (Amnesty International, 2017). Despite criticisms against the government’s approach, there are no indications that inpatient rehabilitation services take part in forced labor or abuses (Amnesty International, 2017).

Soon, one of the most common threads that would link thousands of killings either due to police operations or vigilantes/hired killers, would be that they were former surrenderees. In addition to the president’s vocal support for WoD, investigative reports and publications attest to hired killers being linked to the police; some were even police officers in disguise, killing for financial incentives of about 10,000 pesos per killing (Amnesty International, 2017). On another note, official orders from institutions have provided structures for the WoD.

3

For example, the Command Memorandum Circular No. 16-2016 that operationalized the anti-illegal drug campaign, issued by former police chief retired general Ronald dela Rosa, the main implementer of the WoD in Davao during Mr. Duterte’s reign as mayor. The Memorandum Circular (MC) uses the vague term “neutralize,” which, as seen in information reports filed by the PNP during pre-operations, is synonymous to “kill” (Buan, 2019). Despite “neutralization” being absent from the official PNP Manual of Operations, the former chief confirmed that it is used in PNP reports and parlance meaning to “kill” (Free Legal Assistance Group [FLAG] cited in Buan, 2019). The MC has its counterpart issued by the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) through its MC No. 2017-112, which operationalized the Mamamayang Ayaw sa Anomalya, Mamamayang Ayaw sa Iligal na Droga or MASA MASID (Buan, 2019). The system has been highly criticized for allowing residents to anonymously report suspected drug users without proper checks and balances. An example documented by Amnesty International (2017) illustrates the gaps in the processes when a purok leader in Mindanao shared how he compiled a “drug watch list” as he was instructed by the police to do so. The leader collected names of those who previously used drugs (regardless of their history being “drug free”), in addition to those he knew personally and were referred to him by community members. Despite a lack of certainty, the leader then submitted the list to the police, entrusting the role of verifying data to the latter. For the WoD in Metro Manila, the same organization has documented the similar processes committed by local government unit (LGU) leaders. In effect, these questionable and unverified lists might be considered as “unsubstantiated blacklists” (Amnesty International, 2017).

In addition to documented and direct actions of the State and its proponents in encouraging the WoD, the refusal to disclose data regarding so-called legitimate police operations prevents accountability. Retired Senior Associate Justice Antonio Carpio was adamant in his role as member-incharge in the petition by Center for International Law (CenterLaw), by leading the Supreme Court (SC) in unanimously demanding for documentation regarding WoD police operations (Buan, 2019). The PNP and the Office of the Solicitor General (OSG) were required to provide documentation regarding 20,322 killings committed by both policemen and vigilantes from July 1, 2016 to November 27, 2017 (Buan, 2019). However, despite being legally mandated to provide documents, the documents sent to the SC only showed further negligence by law enforcement authorities in upholding due standards:

The OSG and PNP have displayed a lack of intention to obey the processes of this Honorable Court… the misrepresentation on and submission of irrelevant documents to the Supreme Court by the OSG and PNP constitute direct contempt of court (CenterLaw in Buan, 2019).

4

Reports on the killings also show that the WoD mainly targets males belonging to marginalized sectors. However, while few women have been directly targeted by perpetrators, each death of a male surrenderee or suspect from marginalized communities means that countless women are left to deal with the stigma associated with being linked to drug users, as they struggle with the heavy burden of addressing the financial, psychosocial, and emotional needs of their traumatized family members (Dionisio, 2020). These women have much to share as everyday survivors of systemic violence and poverty. In addition to their personal voices, it is also through their roles as mothers, wives, partners, daughters, cousins, and sisters of their dead loved ones that they are called to advocate further.

The goal of this research is to serve as an avenue for the voices of these women to be heard, along with their valid grievances and thirst for justice. Building on this initial goal, their experiences and support systems, composed of family, fellow survivors and partner advocates,and the community, will also be assessed through the narratives of the women survivors. Through systematic analysis, recommendations will be outlined based on the needs and strengths of the women, and the remaining gaps for partner agencies and service providers like civil society organizations (CSOs), non-government organizations (NGOs), faith-based, and government organizations, will be identified to enable grounded and collaborative efforts for the healing and social empowerment of these women advocates and survivor families.

Statement of the Problem

Survivors of Human Rights Violations (HRVs) deserve avenues for empowerment and healing through their personal assertion of government and offender accountability, claim-making for reparation, and their powerful voices and roles in advocacy-raising for human rights.

Thus, there is a need for these families to reclaim their rights and lives. Despite an active network of non-government organizations (NGOs), civil society organizations (CSOs), and faith-based organizations partnering with survivors, there is a need to build a holistic and comprehensive support system that is rooted in the survivors’ actual needs, and proactively shaped and guided by them as victims, survivors, and stakeholders.

This research will engage the families who have experienced the multifaceted violence associated with the extrajudicial killings (EJK) of their loved ones, explore and assess the different systems that affect their ability to address the issues caused by the aftermath of the violence, and to further assist both support networks and survivors in facilitating relationships and services that are based on client needs and strengths, and would uphold the potential of clients as growing human rights advocates.

5

These are the specific objectives of the research:

1. To identify the bio-psycho-social-spiritual changes, needs, and hindering and facilitating factors experienced by the EJK surviving families during the process of grieving, coping, and recovery.

2. To explore the views, meanings, struggles, roles, and processes identified and experienced by the surviving EJK families in their claim for reparation for damages.

3. To determine the factors influencing their desire or lack thereof to seek accountability and claim reparations through the filing of legal cases and litigation.

4. To explore the potential of the EJK surviving families to organize their own association so they can assist and support each other in their needs and have a unified voice in seeking justice and reparation.

5. To identify the network of organizations and programs and services made available to surviving families of the EJK victims.

6. To identify effective strategies utilized by various stakeholders in the advocacy of human rights and seeking justice and accountability from the State/government.

In line with the research objectives are these questions that the research seeks to answer:

1. What are the demographics (age, gender, role in the family of both the EJK victim and the respondent, and their relationship) and the bio-psycho-socialspiritual changes, needs, and hindering and facilitating factors experienced by the EJK surviving families during the process of grieving, coping, and recovery?

2. What are the roles, views, meanings, struggles, and strengths experienced by the respondents in the process of claiming reparation for damages and advocating for their human rights?

3. What are the factors influencing their desire or lack of desire to seek accountability and claim for reparation such as filing of legal cases or litigation, or other ways through which they can seek justice?

4. What are the effective strategies utilized by various stakeholders in the advocacy of promoting human rights and seeking justice and accountability from the State?

5. What and how did the various network of organizations provide support and make available the programs and services to surviving families? What suggestions do the networks have to make their support more effective and responsive?

6. What are the different potentials to organize the EJK surviving families?

6

Scope and Limitations

The researchers conducted the study with 10 surviving family members left behind by EJK victims. All 10 come from across Metro Manila, five of whom come from the PAGHILOM program based in the City of Manila, led by Fr. Flaviano “Flavie” Villanueva, S.V.D., and the other five from Solidarity with Orphans and Widows (Project SOW) led by Fr. Daniel “Danny” Franklin Pilario, C.M., in Quezon City.

The study sought to explore the different kinds of factors that have affected the surviving families in dealing with the effects of the WoD in their lives, as well as identify their various needs to inform the creation of a network of organizations providing different services.

The study heavily depended on the willingness and desire of the surviving families to speak out, seek justice, and eventually claim financial reparations, and drew from these factors their possible and potential roles in human rights advocacy, including claim-making.

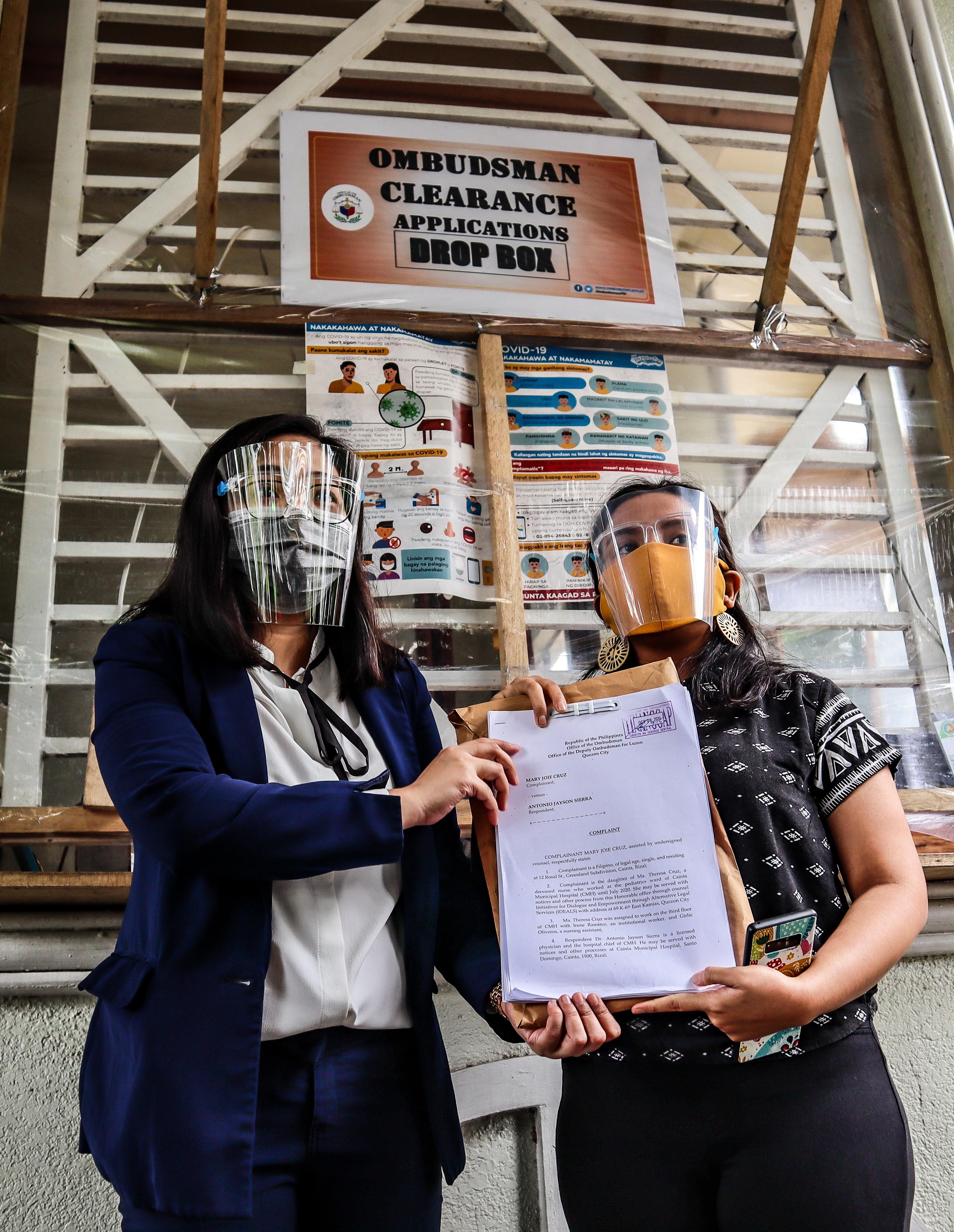

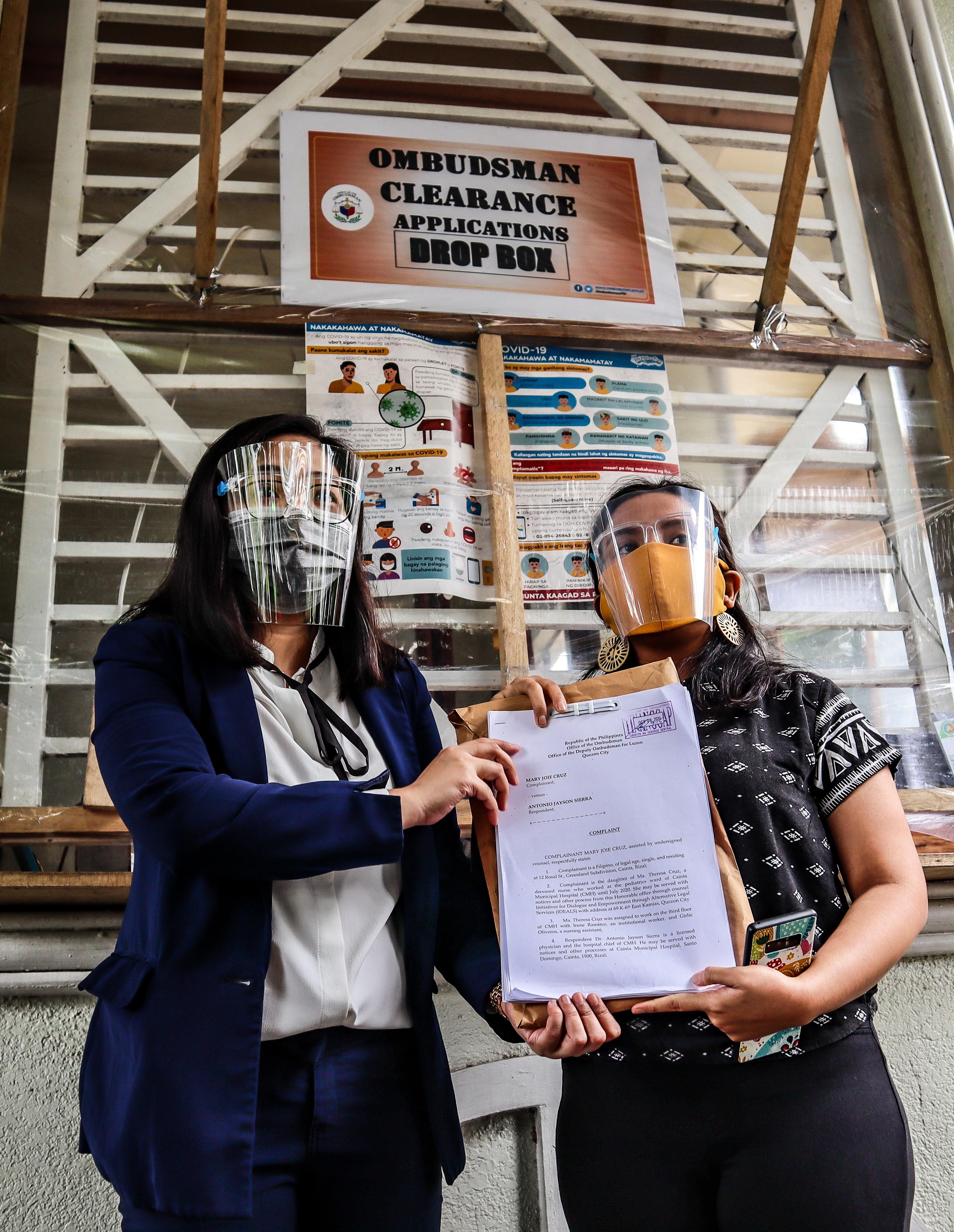

Moreover, because of the sensitivity of the cases and the current COVID-19 pandemic that caused limitations to movement, looking for safe spaces to do the data gathering with the participants was one of the primary challenges faced by the researchers. Mobility and physical gatherings were limited, thus the implementation had to adjust accordingly. Compliance to the minimum health and safety standards by the Department of Health (DOH) was strictly observed for the conduct of face-to-face interviews.

The researchers, with the help of the target programs, conducted a validation test for the target participants. The participants had been pre-identified by the program as: emotionally stable or out of the psychological crisis state, at least 18 years old, and had been exposed to the EJK incident at least two years ago (2016-2018). Moreover, the participants identified or suspected their perpetrators as state agents or related to state agents. Aside from the EJK surviving families, the staff and implementers of the target programs were also given structured written interviews to know their views on the WoD and the strengths and gaps of their respective programs.

7

SignificancE of the Study

The findings of this study will contribute to enabling organizations who are eager to establish relationships with other organizations in the creation of a holistic and multidisciplinary support network for the survivor families of the anti-illegal drug campaign. This is because the needs, experiences, and recommendations of the survivors regarding their current and ideal contexts will be systematically assessed considering the goal to have a more unified collaborative effort with the survivors.

In addition, the need for claim-making for reparation as survivor advocates will be explored. This would enrich literature and experiences for both service providers such as nongovernment organizations (NGOs), civil society organizations (CSOs) and faith-based organizations (FBOs), and client survivors who are challenged in the realm of legal empowerment. This would contribute to the sustainability of initiatives as most service providers - though able to provide key services such as food donations, counseling, support groups, and livelihood programs - are unable to prioritize legal needs due to valid limitations such as financial and security related issues often associated with legal casework.

For a shared understanding of these terms, the authors stand by widely accepted definitions and characteristics of these organizations, while acknowledging that there remains certain contentions in terms of definitions as there are overlapping and interconnected features, and as organizations are multifaceted. According to the UN Guiding Principles Reporting Framework developed by Shift (n.d.), Tomlinson (2013), and VanDyck (2017), the term CSO is the overarching classification among the three as it compromises both NGOs and FBOs. This may be traced to how “civil society” may be broadly defined as the realm outside the family, State, and market, which consist of organizations and collective actions (VanDyck, 2017). Despite these sources agreeing with CSO as an encompassing term, Tomlinson (2013) acknowledges that both development actors and governments, particularly governments from developing countries, utilize the phrase NGO more.

Proceeding to the next term, Karns (n.d.) characterizes a nongovernmental organization (NGO) as a group of individuals or organizations formed for service provision and advocacy raising regarding various human and environmental concerns. According to Karns (n.d.), “NGO” was coined by the UN in 1945 to distinguish these organizations from private organizations and intergovernmental organizations

8

(IGOs) such as the UN. Majority of these NGOs are also nonprofit organizations, and though not affiliated with governments, NGOs nonetheless work with different governments and international entities in providing technical expertise and accessing funding for local programs (Karns, n.d.).

In terms of FBOs, as mentioned earlier, these fall within CSOs (Tomlinson, 2013, and VanDyck, 2017). In fact, earlier literature has also used the term “religious nongovernmental organizations.” Despite FBOs being a “subcategory” in terms of the CSO and NGO world, FBOs nonetheless remain complex and evolving due to changing organizational structures and various forms of faith expression, in addition to whether these FBOs provide certain services or not (Tadros, 2010). However, as the main FBOs in this study are PAGHILOM and Project SOW, the authors consider Tadros’ (2010) narrowed definition regarding service-providing FBOs as apt which is that “as a civil society organization of a religious character or mandate engaged in various kinds of service delivery.”

Lastly, though the current context might not allow the filing and litigation of legal cases on behalf of survivors, this could assist in the gradual readiness of these stakeholders once political conditions would permit them to opt for legal action and financial reparation. Consequently, legal actions could be more feasible due to the growing network this research seeks to foster. It is this network that would enable survivors to naturally grow into their roles as human rights advocates, as they are encouraged and empowered.

Definition of Terms

To ensure that the understanding of the readers and the researchers are the same, the key terms used frequently all throughout the study are defined as follows:

Asset. Refers to capital with a positive value, it could be in a tangible or intangible form such as human, financial, or social capital (Sampson & Bean, 2006 as cited in Homan, 2011 p.40)

Bio-psycho-social-spiritual impacts. For the purpose of this research, this refers to the disruptions that the surviving families experience on the biological, psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions of their life after the victims were killed through extrajudicial killings (Sumalsy, 2002).

9

Bio-psycho-social-spiritual needs. For the purpose of this research, this refers to the biological, psychologica, social, and spiritual needs of the surviving families that arise as a result of the EJK incident (Gale et al., 2019).

Buy-bust operation. Refers to entrapment plan police authority organized to capture drug-related criminals by setting-up fake transactions with illegal drug-sellers (Ayala, 2017).

Coping. Refers to an individual’s adaptation to manage their negative emotions brought by various stressors (APA Dictionary of Psychology, 2014). Additionally, the researchers defined coping as the short-term process they underwent to manage to survive and deal with the aftermath of the incident.

Coping Mechanism. Refers to the activities an individual does to manage the trauma and/or stress they experience, in such a way that their well-being is stabilized and the negative emotions are managed (Good Therapy, n.d.).

Drug raid. Refers to unexpected police operations with the objective of making arrests and/or confiscating items related to illegal drugs (Collins Dictionary, n.d).

Empowerment. Refers to the development of assets and capabilities of people. Some of the indications that marginalized sectors are being empowered are the ability to participate, negotiate, influence, and demand accountability from agencies that are responsible for providing services for that particular sector, or for the people in general (Jayakarani et al., 2012).

Extrajudicial Killing (EJK) or Extrajudicial Executions. Due to the historic commissions of EJK throughout history, and particularly in the Philippines, the researchers agree with what veteran lawyer Theodore Te (2019) describes as a “general and all-encompassing” definition of EJK stated in Republic Act 11188 Section 5(1):

Extrajudicial killings refer to all acts and omissions of State actors that constitute violation of the general recognition of the right to life embodied in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the United Nations Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the UNCRC and similar other human rights treaties to which the Philippines is a State party.

Further contextualizing the definition to fit the purpose of this research, the incidents of EJK presented in this study were all committed under the guise of WoD. Related literature agrees with the Philippine definition that, in the absence of deliberate order, the government could still be held accountable of EJK if it responds with complicity or acquiescence despite the presence of unlawful and deliberate killings (Amnesty International, 2017). Consequently, these executions might either be carried out by State

10

forces or by non-state groups that the government fails to investigate and prosecute despite its main role as duty bearer (Amnesty International, 2017).

Extrajudicial Killing (EJK) Surviving Families/Surviving Family Members/ Survivors. This research would make use of this phrase to serve as a key term in this study, and would make use of the APA definition of “family” below, and further contextualize it to stand for family members of EJK victims who have been “left behind” after their deaths. This phrase was also used by Human Rights Watch in their annual report (2020). There are variants of this term but stand for the same principle of the “living” or “surviving” family members who have outlived, or at times born after the incident. Some examples are “families of EJK victims” and “EJK families.”

Extrajudicial Killing (EJK) Victim. This study would also use this term referring to a person who has been killed or executed during an extrajudicial killing by state or non-state actors (eg. Vigilante Groups) under President Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines. This is for the purpose of a more focused discussion However, extrajudicial killings have been happening even prior to Pres. Duterte’s term as president (Te, 2019 & Amnesty International, 2017).

Family. Refers to a kinship unit consisting of a group of individuals unified by blood or by marital, adoptive, or other intimate ties (APA Dictionary of Psychology, 2014).

Grief. Refers to painful emotional experiences that a person deeply feels after a significant loss, usually a death of a family member or a loved ones (APA Dictionary of Psychology, 2014).

Grieving. Pertains to the individual’s personal experience of deep sorrow and longing to after losing someone or something they loved (Mulemi, 2017). Additionally, for the purpose of this research, grieving also focuses on the surviving families’ emotional outbursts and ways of letting their thoughts and emotions out.

Human Rights. Refers to rights that are “inherent to all human beings regardless of race, religion, gender, sex, color, nationality, ethnicity, language, or any other status (Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights [OHCHR], 2019).”

Human Rights Advocate/Defender. Refers to a person who acts, whether in a professional or informal manner, to promote and protect human rights through various activities (OHCHR, 2019).

11

Human Rights Violation. Shall refer to two kinds of violations:

(1) Violations intentionally perpetrated by the State; in this research, the Philippine government. When the State engages in human rights violations, various actors or agents can be involved such as police, judges, prosecutors, government officials, etc. (Human Rights Careers, 2020).

(2) Violations as a result of the State failing to protect or prevent the violation. It occurs when there is a conflict between individuals or groups within a society. If the State does nothing to intervene and protect vulnerable people and groups, it is considered a participant in the violations (Human Rights Careers, 2020).

Illegal Drugs. Refers to drugs that did not go to legal and/or proper medical procedure to be produced, distributed, or consumed (Market Business News, 2019).

Intervention. Refers to planned action conducted to improve one’s well-being (Merriam Webster, n.d.).

Justice. Refers to the fair outcome and right resolution after going through informal negotiation or legal process (APA Dictionary of Psychology, 2014).

Litigation. Refers to the legal process of resolving conflicts and disagreement (Merriam Webster, n.d).

Palit-ulo. Refers to the involvement of police authority, or persons believed to be policemen, threatening a drug suspect with jail or death unless the suspect points to another suspect they could arrest or kill – a head in exchange for someone else’s (Talabong, 2020).

Perpetrator. Refers to someone who has committed a crime or harmful act (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d.).

Police operations. Refers to activities conducted by police authority to keep the law and order, and ultimately to protect citizens from dangers, crimes, and disorder in society (ScienceDirect, 2015).

Recovery. Recovery generally pertains to the individuals’ capacity to reclaim their lives, overcome traumatic events, and healthily manage their thoughts and feelings (Manitoba Trauma Information and Education Centre, n.d.). Additionally, for the purpose of this study, the researchers defined Recovery as the long-term process which facilitates healing from the incident such that they can reclaim their lives and become fully-functioning.

12

Reparation. Refers to any act of indemnifications, be it monetary or otherwise, that a government is accountable to fulfill to make amend to its wrongdoings (Dictionary.com, n.d.). For the purpose of this research, reparation shall also refer to any action done to repair any kind of damage, legal or non-legal.

Riding-in-Tandem. Refers to crimes committed by individuals or a pair of people riding on a motorcycle (Tan, 2014). For the purpose of this research, this pertains to the mode of arrangement that the suspects for EJK used to execute the crime and flee from the scene.

Security. Refers to freedom from danger, risk, doubt, anxiety, or fear (thefreedictionary. com, n.d).

Social functioning. Defined as the individual’s ability or lack of it to perform roles and tasks expected to them by different individuals, their immediate social environment, and society (Law Insider, 2013).

State agent. Refers to any officer or employee of a State agency with paid compensation, in whole or in part, from State funds and whose activities does not include any volunteer works without compensation (Law Insider, 2013).

Support system. Refers to various systems such as individuals, a network of people or groups that provide the affected individual or groups with practical or psychosocial support (Merriam Webster, n.d).

Trauma. Refers to any disturbing experience resulting in significant fear, feeling of helplessness, dissociation, confusion, or other disruptive thoughts and emotions that are intense enough to have a long-lasting negative effect on a person’s functioning (APA Dictionary of Psychology, 2014).

Urban Poor. Refers to individuals or families residing in metropolitan areas with earnings that are below the poverty line. Most of the time, they are part of the marginalized sectors of society that struggle to attain the minimum needs to experience living decently. They also usually settle on state-owned properties; such as garbage sites, cemeteries, sidewalks, or on private lands (Presidential Commission for the Urban Poor, 2018).

War on Drugs (WoD). Refers to Philppine President Rodrigo Duterte’s promise of largescale crackdown on drug lords, drug dealers and addicts in his term that resulted in increased cases on extrajudicial killings (Xu, 2016).

Well-being. Refers to the individual’s holistic state that encompasses their health and life’s satisfaction, and capacity to manage daily stress (Davis, 2019).

13

Review of Related Literature

The Incident: Narratives of EJK survivors and their families

Drug use and drug addiction are some of the biggest issues globally. Many reports of people who have become addicted to drugs despite adverse consequences to the individual and society are recorded. According to the United Nations, in 2017, an estimate of 271 million people used drugs globally. Moreover, some 35 million people are estimated to suffer from drug use disorders in 2019 and need appropriate treatment, yet only one of seven people with a drug disorder has received treatment (United Nations, 2019).

In the Philippines, the War on Drugs, which was created to respond to the alleged wide-spread problem of the country involving drug users and pushers, has been a controversial topic since the new administration took over in 2016. There were several cases that have been reported regarding the so-called EJKs occurring in the country under this policy. These narratives shared by the surviving families are proof that this HRV happened and will continue to happen in the country if not stopped. After only two months since the onset of this administration, UN rights experts have already called out the Philippine government to end the killings amidst the WoD. Agnes Callamard, the UN Special Rapporteur on summary execution, said, “Claims to fight illicit drug trade do not absolve the Government from its international legal obligations and do not shield State actors or others from responsibility for illegal killings” (Office of High Commissioner for Human Rights [OHCHR], 2016).

14

2

Chapter

International law states that each country should respect, protect, and fulfill human rights. The Philippine government was allegedly violating this because of the extra-judicial executions that have happened the past few months after President Rodrigo Duterte was elected. There were reportedly more than 850 people killed in May to August 2016 alone (OHCHR, 2016).

From July 2016 to September 30, 2018, the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) was able to record up to 4,948 killings during police operations for suspected drug users and drug dealers. Meanwhile, according to the report of Human Rights Watch, the Philippine National Police have recorded 5,526 suspects killed in police operations from July 1, 2016 to June 30, 2019. This does not include the thousands more killed by unidentified gunmen (Human Rights Watch, 2020).

As human rights champions consistently point out, these reports are not only cold, hard statistics, but are reflective of precious human lives. Moreover, they fail to account for the lives of children and family members affected by the loss of their loved ones. The reports also tend to overlook the truth behind cases of people killed due to drug-related allegations yet did not have the chance to pursue any judicial or legal process to prove or disprove the said allegations.

One example is the case of 11-year-old “Jennifer,” one of the children interviewed by Human Rights Watch, whose father was allegedly shot dead by the police. The child had trouble eating, became withdrawn, and for a while stopped going to school since the incident. Meanwhile, “Kyle,” a five-year-old boy, developed aggressive behavior after his father was murdered. (Human Rights Watch, 2019). There is also “Maria,” whose last memory of her father was him lying face down, before gunshots were fired on a December morning in 2016. She recalls seven men who look like policemen coming in their door that day (Smith, 2019).

In the case of Kian Delos Santos, a 17-year-old teenager who was murdered by three policemen, he was accused of being a drug courier in Manila City. The CCTV footage showed Kian being dragged away by the police and found dead in the pigsty. According to the court hearing, the policemen stuck to one story and said that they were in the middle of a One-Time Big-Time operation when someone fired a gunshot at them and that they had chased the gunman. In contrast, three eyewitnesses, two of whom were minors, said the policemen arrived on a motorbike and went straight to Kian Delos Santos’ house, kicked its gate, ran into Kian and punched him. Then, the policemen allegedly dragged Kian to the pigpen until witnesses then heard gunshots (Buan, 2018).

15

Kian’s murderers were found guilty and sentenced to up to 40 years of imprisonment (BBC News, 2018). Kian’s father, Saldy Delos Santos, said in an interview:

“Ang pangarap ng anak ko maging pulis. Kaya po siya nag-aral sa Our Lady of Lourdes College dahil may criminology, tapos kukuhanin ‘nyo lang nang ganoong kadali.” (My son dreamed of becoming a policeman. He studied at Our Lady of Lourdes College because it offered criminology, yet you took him away just like that) (Gavilan, 2018).

Another casualty was Myca Ulpina, a three-year-old child. A police raid was conducted against her father, Renato Dolofrina, who lives in Rizal province. The encounter killed both the father and Myca. This case has garnered public attention and the team responsible for the operation stated that the father used Myca as a “shield” for self-protection (Conde, 2019).

As mentioned, it is not only those killed who are considered victims of such cases. Even the families they left behind can be considered victims of HRV. Some of their families were illegally arrested and detained. Eleven families experienced harassment and threats during and beyond the incidents, leaving children without parents. Their right to security was deprived from them by the authorities who were supposed to be protecting them (Philippine Human Rights Information Center [PhilRights], 2019). One of the interviewees claimed:

“Hindi na namin nararamdaman na may seguridad pa kami. Hanggang ngayon, kapag may pumasok na pulis sa lugar namin, inaatake ng nerbiyos ang mga magulang ko kasi natatakot sila na baka may patayin na naman.” (We no longer feel secure. Until now, whenever there are police officers entering our community, my parents get so nervous because they fear that someone else will get killed again.) (PhilRights, 2019).

Due to the alarming cases, the United Nations (UN) Children Agency and United Nations International, Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), together with other children’s institutions, have been proactively condemning the death of children caught between the administration’s WoD (Conde, 2019).

Furthermore, some reports indicate that the drug raids are not entirely reliable or truthful. These reports claim that some policemen who implement the WoD manufactured evidence by planting weapons and drugs or saying that the alleged suspect “fought back” to justify their killings. Most of the victims lived from impoverished urban areas, and even children were targeted and killed. Several organizations concerned with the rights of children reported that more than a hundred children were killed since June 2016 (Conde, 2020).

16

These rabid killings of thousands of individuals during the Duterte regime have been alarming for Human Rights Watch as they basically strip the person from their rights as a human being. These HRVs, specifically the killings committed, were highly encouraged to be reported to the United Nations’ Human Rights Council (Conde, 2019), with the hopes that it will lead to the passage of a resolution for the UN Human Rights Council to launch a formal investigation on the rampant drug-related killings in the Philippines (Matar, 2019). In 2020, however, the UN Human Rights Council passed a resolution that provides technical assistance to the Philippines such that the country can uphold its human rights obligations, but the organization reiterated that no formal investigation will be conducted as they recognize the efforts of the Philippine government to review the reports of EJK killings in the country (Subingsubing, 2020).

The Aftermath: The biopsychosocial-spiritual well-being of survivors

This section seeks to understand the biopsychosocial-spiritual functioning of an individual as they grieve and deal with the loss of a loved one specifically due to EJKs committed at the start of the Duterte administration. Grieving is a complex phase in someone’s life. It is crucial that this paper tackles the varying emotions that could interrupt the person’s ability to function properly and take on roles and responsibilities, including the basic routine of their everyday lives (Testa, 2020). It is also essential to note that grief is experienced differently by everyone. It depends on the circumstances, various emotional factors during that part of the individual’s life, association with the deceased, their religion, cultural and social norms, and even gender expectations (Family Caregiver Alliance, 2013).

This section aims to highlight the impact of loss on individuals, families, and communities in order to assess and be able to recommend the necessary and most appropriate intervention and support for them while recognizing each individual’s unique situation. As Testa (2020) stated, “the loss of someone you love leaves a permanent imprint on our lives,” and this drastic change differently affects everyone.

Below is the elaboration to provide a better understanding on how surviving families are affected on the different aspects of their life.

17

ECONOMIC IMPACTS

One could only imagine the impact and the consequences of these instantaneous changes to the families left by victims of the WoD On the economic aspect, starting again and trying to cope with the tragedy may also mean: moving to a different area and buying/renting a new place; an urgency to look for a new job or additional sources of income; or, beginning to rebuild a life in a new place with little to no support system. These kinds of situations have also forced families to be apart from each other. One human rights defender from Sampaloc shared (Philippine Human Rights Information Center [PhilRights], 2019),

“May ilang pamilya kami na pinuntahan na talagang binantayan namin. Umalis sila, lumipat ng probinsya. ‘Yung bahay nila nakatiwangwang lang. Iniisip nila na baka balikan sila.” (There are some families that we visited and kept track of. They left their houses and transferred to the province. They think that the perpetrators will get back to them).

PhilRights has also conducted data gathering to identify the effects of EJKs on the urban poor families and communities last 2017. They have reported that 49 out of the 58 cases they have documented were breadwinners and financial providers for their families. After the killings, the women and elderly are expected to support the family’s finances. There are instances as well where the eldest in the family takes up the role of the parents who have passed on. During these circumstances, survival is the primary concern, which usually leaves no room for the person to grieve and process their emotions. They are forced to act tough to support the surviving family members (PhilRights, 2017). These individuals are pushed to look for additional means of income regardless of the working conditions or salary range.

In addition, the child/children of the victims killed were also the ones heavily impacted by the tragedy. Based on the report of Human Rights Watch (2016), one of the families they interviewed in Mandaluyong narrated that the three children of the victim, Renato, stopped attending school. The eldest became a garbage collector to support his siblings. The sibling said in the report,

“I had to work harder when my father died. I became a father to my siblings because I don’t want to see them suffer … so I’m doing everything I can. I force myself to work even if I don’t want to. I force myself for me, for my siblings” (Human Rights Watch, 2016).

18

In the same report, the victim’s wife and mother to their children said:

“It’s hard because you don’t know how you’re going to start, how you’re going to fend for your children, how you’re going to send them to school, and how you’re going to pay for their daily expenses and their meals. There are times they can’t go to school because they don’t have school allowance. We lost our tap water because we can’t pay the water and electricity bills, and many more things “(Human Rights Watch, 2016).

The traumatic experiences they went through not only affected them psychologically but their financial and economic state as well.

SOCIAL IMPACTS

As the surviving families seek safety, the social cohesion of their own families, communities, and neighborhoods are also disrupted. According to PhilRights’ documentation of EJKs related to WoD (2019), families still suffer months and even years after the incident. As the organization conducted their field work and data gathering in communities that are heavily affected by the WoD, members from urban poor communities in Bulacan, Caloocan, Sampaloc, and Navotas, shared their experiences and concerns. Most interviewees expressed their fears for their securityas they understand that these incidents are violations against their basic human rights. Specifically, the families left behind feel that their community and their own home are no longer a safe space for them. The trust between neighbors and community members was also tainted as everyone became vigilant with each others’ actions, and there seems to be confusion on where the community can turn to when there are instances of HRV.

One of the interviewees from Bulacan said:

“Dahil nga doon sa mga nangyayari, parang hindi ka na secure doon sa iyong community kasi mismong mga opisyal ng barangay kasama sa mga nang-raid. May takot nang namamayani, nakikiramdam na ang lahat tuwing gabi at hindi na makatulog. May epekto ‘yung halos linggo-linggo ay may pinapatay. (Because of the incident, you can no longer feel secure in your community. Because even the barangay officials are accomplices during raids. There is a prevailing fear, everyone is vigilant at night and can no longer sleep. The almost weekly killings had an effect [on the community].)” (PhilRights, 2019).

19

A sense of helplessness to attain justice for the families of those left behind was also a prevailing emotion. An interviewee shared:

“Wala kaming nakamit na hustisya diyan. Kahit gusto naming ilaban, di namin mailaban kasi nakatakip ‘yong mga mukha ‘nong mga pumatay. Madaming nakakita na mga kapitbahay na maraming pumasok, na marami sa harap ng bahay namin, pero hindi nila ma-i-describe yong mga mukha dahil nga mga naka-maskara. Kaya kahit gusto namin ilaban, wala kaming magawa. (We were not able to achieve justice. Even though we wanted to fight for it, we cannot demand because the perpetrators were wearing masks. Many of our neighbors saw that there were several people that went inside our house but they cannot describe them because they were wearing masks. That’s why even though we wanted to fight for it, we cannot do anything.)” (PhilRights, 2019).

The threat to the security of the families who were left behind and community members in general has disrupted their way of living and the activities and norms that they have in their small communities. Most of them are left with no choice but to leave their homes because of fear that the tragedy could happen again to their family, their relatives, friends, and neighborhood. As the interviewee recalls the impact of killings in their area, they claimed:

“Wala na silang kalayaan. Wala ng katahimikan sa puso nila. Ultimo pagtira sa bahay nila hindi na nila magawa kasi mas gugustuhin nilang magtago kesa balik-balikan sila kasi hindi naman natatapos sa pagpatay sa kaanak nila. Binabalik-balikan ang pamilya. May cases na patay na si kuya, nakakulong si ate, nakakulong si bunso, nakakulong si nanay. Iniisa-isa ‘yung mga natitirang kamag-anak. Kaya dahil sa takot ay umaalis na lang sila. (They no longer have freedom. There will no longer be a moment of peace in their heart. Even just living in their house, they can no longer afford that because they would prefer to hide than experience the perpetrators to keep on coming back and would not stop until they killed their relatives. They [perpetrators] keep on coming back to the families. There are cases where the older brother is already dead, the older sister is in jail, the youngest child is in jail, the mother is in jail. They go after each of the family members. Because of fear they just leave.)”

(PhilRights, 2019).

20

Another shared:

“Unang-una na nararamdaman nila ay takot. Takot na maulit muli, takot na balikan sila, takot na pati mga anak ay madamay. Takot na sila sa ganong sitwasyon na karamihan ng napapatay ay walang kadahilanan. Kaya para sa kanila hindi na ligtas ‘yung buhay nila. Nawalan na sila ng seguridad. Na kahit sino, bata man o matanda, ay pwedeng kitilin ang buhay. (The first thing they feel is fear. Fear for the incident to happen again, fear that perpetrators will come and go after them, fear that their children will get involved. They are already afraid to be in that position where people get killed without any reason. That’s why for them their lives were no longer safe. They lost their sense of security [knowing] that anyone, children or elderly, can be killed.)”

(PhilRights, 2019).

These statements show the consequences of EJK on the social life and functioning of the individuals/families who were affected. These changes could include “feeling alone, wanting to isolate yourself from socializing, finding it hard to pretend to feel alright, being pushed to be social by others, feeling detached from others, angry that others’ lives are going on as usual and yours isn’t, and not wanting to be alone or feeling needy and clingy” (Family Caregiver Alliance, 2013). These vary since it merely seeks to illustrate the most frequent reactions of persons towards a loved one’s death.

In the context of families and individuals affected by the WoD, the rabid killings have created communities of people that live in fear and are struggling to trust anyone. This is in contrast with how Filipinos value a strong sense of camaraderie (bayanihan) that is not only visible during challenging times but also in their everyday lives. This culture and the prevalent sense of belongingness in Filipino communities were threatened by the seemingly endless killings even amid other pressing matters, such as the pandemic, which certainly would have been better addressed with camaraderie and communal values (BALAY Rehabilitation Center & DIGNITY-Danish Institute Against Torture for the Global Alliance, 2017).

Sadly, the relations of some community members have become akin to walking on eggshells. Mistrust and fear have been the prevalent emotions that community members feel. This disrupted the social fabric of Filipino communities as some individuals and families now keep distance from one another in the fear of being suspected as someone involved with illegal drugs. This has significantly altered the way communities engage and treat each other (BALAY Rehabilitation Center & DIGNITY-Danish Institute Against Torture for the Global Alliance, 2017).

21

BIOLOGICAL IMPACTS

For the surviving families that were left behind, the tragedy also put a toll on their physical well-being. As they try to cope and provide for the needs of their family, the distressing situation has also affected their biological wellness; more so, for the elderly and children. Testament to this was the case of the Roa family, one of the documented cases by PhilRights (2017). When the daughter of Mrs. Roa was killed in their own home, it affected the biopsychosocial functioning of the latter. She no longer wanted to sleep, rest, and eat. This led to various complications until she, too, passed away a year and a half later (PhilRights, 2017).

A similar thing happened to Jennifer, 11 years old, when her father was killed in 2016. She became distressed and lost her appetite (Human Rights Watch, 2016). Aside from these situations, there are instances where the surviving families of the victims compromise their health simply because they do not have much of a choice. One of the survivors of an attempted EJK was taken into custody by the Commission of Human Rights (CHR). He was the sole provider of the family and while he was under the protective custody of CHR, his children and elderly parents who had no sources of income suffered and frequently skipped meals as their budget could barely cover for a kilo of rice per day. Later, the survivor decided to leave the CHR’s custody as he could not stomach the fact that his family was experiencing hunger every day. The EJKs have pushed these families that are already in poor health or poor living conditions to be in a much more vulnerable position as they can no longer prioritize their nutritional needs and health after those traumatic experiences (Human Rights Watch, 2016).

PSYCHOLOGICAL IMPACTS

Beyond the physical manifestations of distress brought upon by these EJKs, there are also emotional and psychological impacts that affect the functioning of the surviving families. These may consist of “sadness, crying spells, anger, frustration, rage, guilt, worry, anxiety, panic, yearning, edginess or irritability, memory problems or feeling distracted or preoccupied, depression, euphoria, passive resignation, fluctuating emotions, sense of lack of control, or others might see [you] as ‘unreasonable’ or ‘overreacting’” (Family Caregiver Alliance, 2013).

During an interview with PhilRights (2017), widowed mothers shared their observations on their children after the incident They claim that there have been drastic changes in their behavior. Manifestations of aggressiveness and ill-temperedness were starting to become evident in their children. Moreover, some began to avoid their home and started to spend more time outside so as not to be reminded of their loss (PhilRights, 2017).

22

Robert, one of the interviewed individuals by Human Rights Watch (2016), shared how his brother was affected by the killing of their father:

John [Robert’s brother] was more affected by my father’s death because ever since my father died, I never see him happy anymore. If I see him smile, it’s forced. He’s still looking for our father because he was my father’s favorite. He easily gets angry now and he loses trust in people (Human Rights Watch, 2016).

Normalization of the violence and killings in these communities have affected the developmental stages of children, values and norms of individuals and families, and it creates a culture of fear ingrained in them personally; collectively, this was manifested as well, since the general atmosphere of fear also became prevalent in their community (PhilRights, 2017).

EJKs are certainly difficult for any individual to accept and process; even more for children who are still building their perspectives, values, and principles in life. A mother from Sampaloc shared how witnessing the killing of her husband affected her child:

“Nahirapan mag-adjust ‘yung panganay ko. Four months ko siyang binantayan sa school kasi nagwawala siya kasi nakita niya ‘yung pagpatay sa tatay niya. Ayaw niyang magpaiwan. Lagi siyang galit sa mga taong nakakausap niya. Di siya kumakain. Iniiyakan ko siya para lang pumasok. Naiintindihan naman ng mga teachers kung bakit siya nagwawala minsan at bigla na lang tatakbo. Kapag gusto niyang matulog, pinapatulog naman siya doon lang sa labas ng classroom. Basta kailangan nakikita niya daw ako. (My eldest had a hard time adjusting. I observed them for four months at school because they fly into a rage since they witnessed the killing of their father. They do not want to be left behind. They are always mad at anyone they talk to. They would not eat. I would cry just so they’d go to school. The teachers understand why they fly into a rage and would suddenly run. When they [her eldest] would want to sleep, they allow it outside the classroom. They [eldest] just wanted to always see me.)” (PhilRights, 2017).

These changes of behavior and attitude are not only manifested by children. Parents and other adults also struggle to process the horrific incident, all the while striving to be strong for their family. Evidently, it affects their emotional and psychological well-being. A mother shared the impact of her eldest child’s death to their family:

23

“Ang asawa ko ayaw nang magtrabaho mula nang mamatay ang panganay ko. Tapos kapag pinag-usapan ang tungkol doon sa mga anak ko na namatay, sumisigaw ang asawa ko; may trauma ‘tsaka galit. ‘Yung anak kong isa malaki rin ang epekto sa kanya kasi isang beses naghahanap siya ng baril. Parang tanga raw siya na wala siyang nagawa para sa pamilya ng kuya niya. (My spouse no longer wants to work anymore since my eldest died. Then when we talk about our children who died, my spouse would keep on yelling; trauma and anger were apparent. My other child was also hugely affected because there was a time they were looking for a gun. They felt stupid because they were not able to do a thing for the family of their older brother.)” (PhilRights, 2017).

Despite these individuals’ and families’ recognition of the psychological and medical support that they need, there has been a lack of awareness on these forms of services. Consequently, the intersectionality of their economic, social, physical, emotional, and mental concerns becomes too overwhelming for them (PhilRights, 2017).

A human rights defender showed their observation from the cases that occurred in their area:

Makikita mo kaagad ‘yung epekto sa mga bata. ‘Yung takot, ‘yung phobia, ‘yung kinikimkim na galit lalo na sa mga bata na mismong nakasaksi sa pagpatay. Tapos meron pa na nakapag-asawa na teenager pa yung bata. Namatayan kasi siya ng magulang, ng tatay. Siyempre napakahirap noon at malaki ang epekto nito sa pagkain, sa kanyang pag-aaral, at sa kanilang pamumuhay. Ang escape niya is mag-asawa kasi ang asawa niya ang bubuhay sa kanya. (You can immediately see the effects of it on the children. The fear, the phobia, the bottled-up anger; especially on the children who witnessed the killings. There are also teenagers who got married at a young age. Their parents, the father, died. Of course it was difficult, it hugely impacted their food [supply], their education, and their lifestyle. Their escape is to get married because the spouse would sustain them.) (PhilRights, 2019).

Their statement exhibits how the biopsychosocial well-being of an individual is interconnected. The killing of their family member and loved one led to interrelated issues that directly and indirectly affect them, their family, and their community.

24

Finally, it is also important to highlight the spiritual effect of grief on a person. Family Caregiver Alliance (2013) discussed that one starts to philosophize life and death when faced with the loss of a loved one. There are different reactions to this: some may seek further closeness with their faith to find solace, or there may be feelings of rage or anger towards the Supreme Being they believe in. In the current WoD situation, many individuals and families have sought help and support from churches, parishes, and other religious institutions. Their faith became one of the support systems they hold on to during these challenging phases of their lives.

On Psychological Impacts: A Closer Look at Grieving and Trauma