FRAGILE MOUNTAINS

0 2 3 4 1

Ph Parra © 2022

, , . , , , , , , , , , , Territories Inner Crisis Interdependence Molecular Resources Constellation Metromontagna Cooperative Community

Economies Transition

, Fragile Areas Environmental Impacts Localisms Abandoned Borghi Identity Participation Multiple

Representation Energies

Agro-Forestry

Laboratory

Sustainable Culture-Based

THE INLAND PENINSULA Between Villages and Borghi

The civilizations of the Apennines, despite the geographical diversity to which they belong, have recurring common elements and are attributable to a single economic and social matrix.

Inland Italy, from North to South, has historically been structured on the identity of small villages and towns, a constellation of distinguishable but strictly interconnected localisms, which collectively have contributed to the social and cultural definition of the Bel Paese.

Starting from the end of the nineteenth century and with a strong acceleration after the Second World War, with the affirmation of the industrial society and an increasingly urban-centered development model, the Italian internal areas have undergone a progressive process of marginalization, they have been the object of a great depopulation and an almost definitive abandonment, inevitably becoming more and more vulnerable.

We have lost space (Pazzagli, 2021) together with the progressive disappearance of the territorial heritage that has structured Italy.

Le civiltà dell’Appennino, nonostante le diversità geografiche a cui appartengono, presentano ricorrenti elementi comuni e sono riconducibili ad un’unica matrice economica e sociale.

L’Italia interna, da Nord a Sud, si è storicamente strutturata sull’identità dei piccoli borghi e paesi, una costellazione di localismi distinguibili, ma strettamente interconnessi, che collettivamente hanno contribuito alla definizione sociale e culturale del Bel Paese

A partire dalla fine dell’Ottocento e con una forte accelerazione nel secondo dopoguerra, con l’affermarsi della società industriale e di un modello di sviluppo sempre più urbano centrico, le aree interne italiane hanno subito un progressivo processo di marginalizzazione, sono state l’oggetto di un grande spopolamento e di un quasi definitivo abbandono, diventando inevitabilmente sempre più vulnerabili.

Abbiamo perduto lo spazio (Pazzagli, 2021) e stiamo contribuendo alla scomparsa del patrimonio territoriale che ha strutturato l’Italia.

23 Communities supporting Landscapes

It En { * } 1. 01

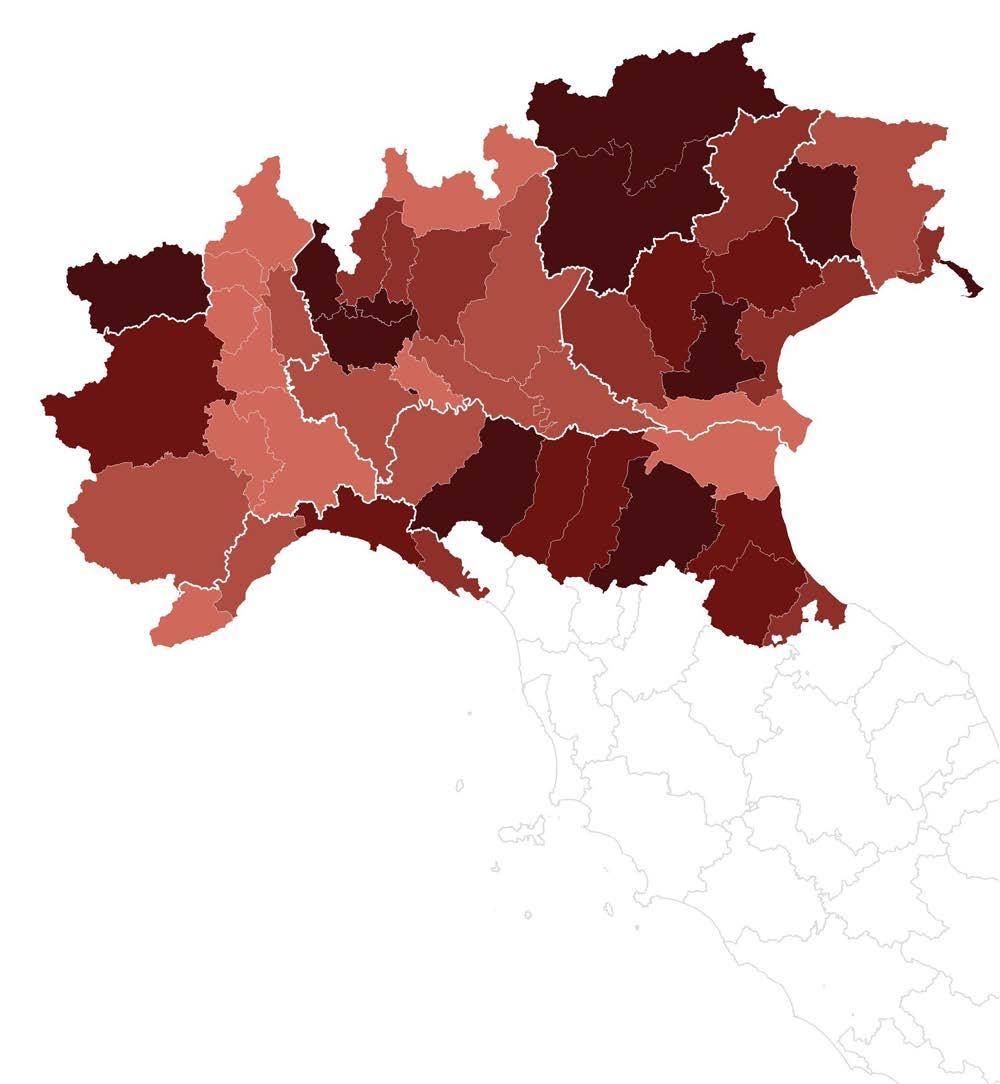

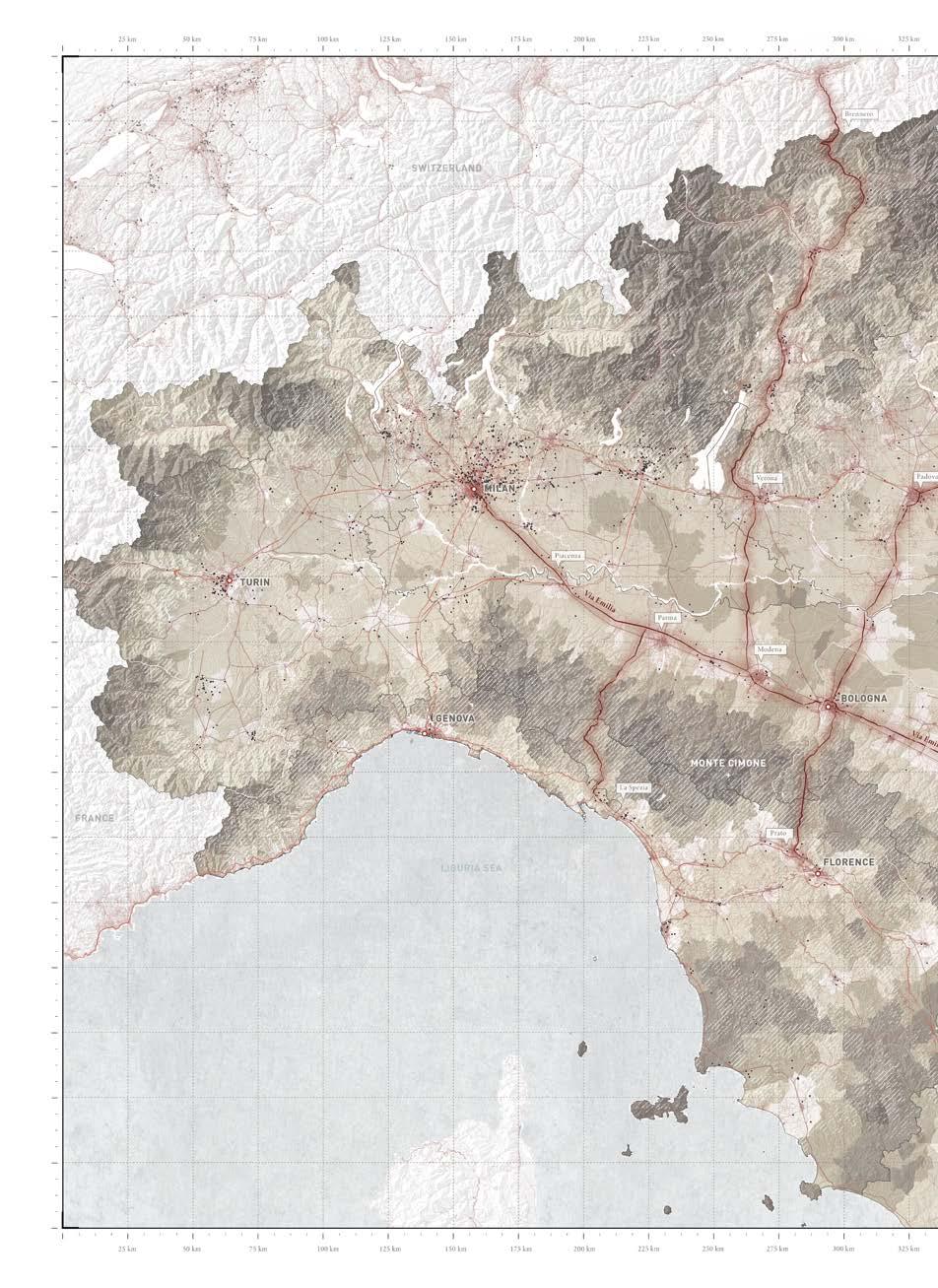

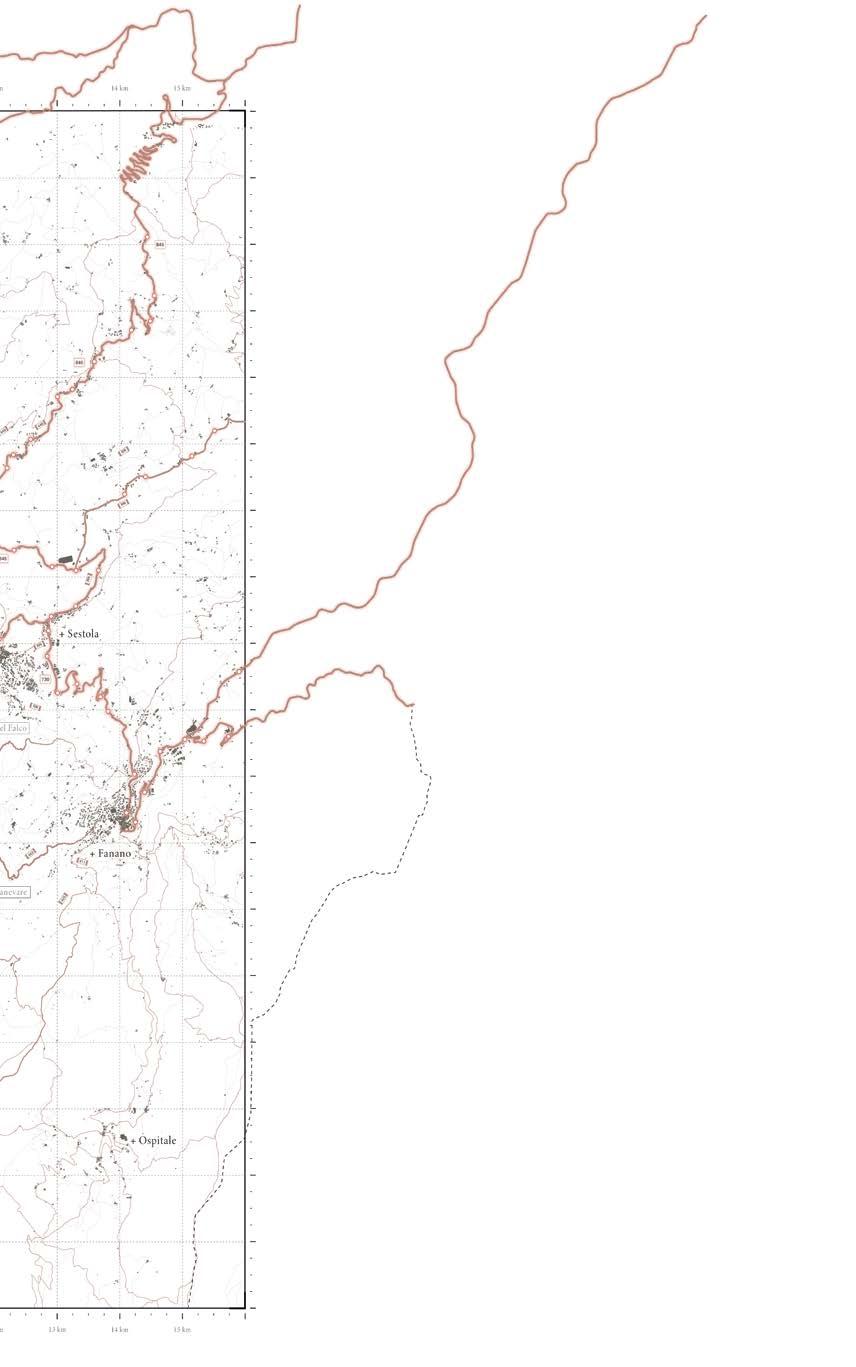

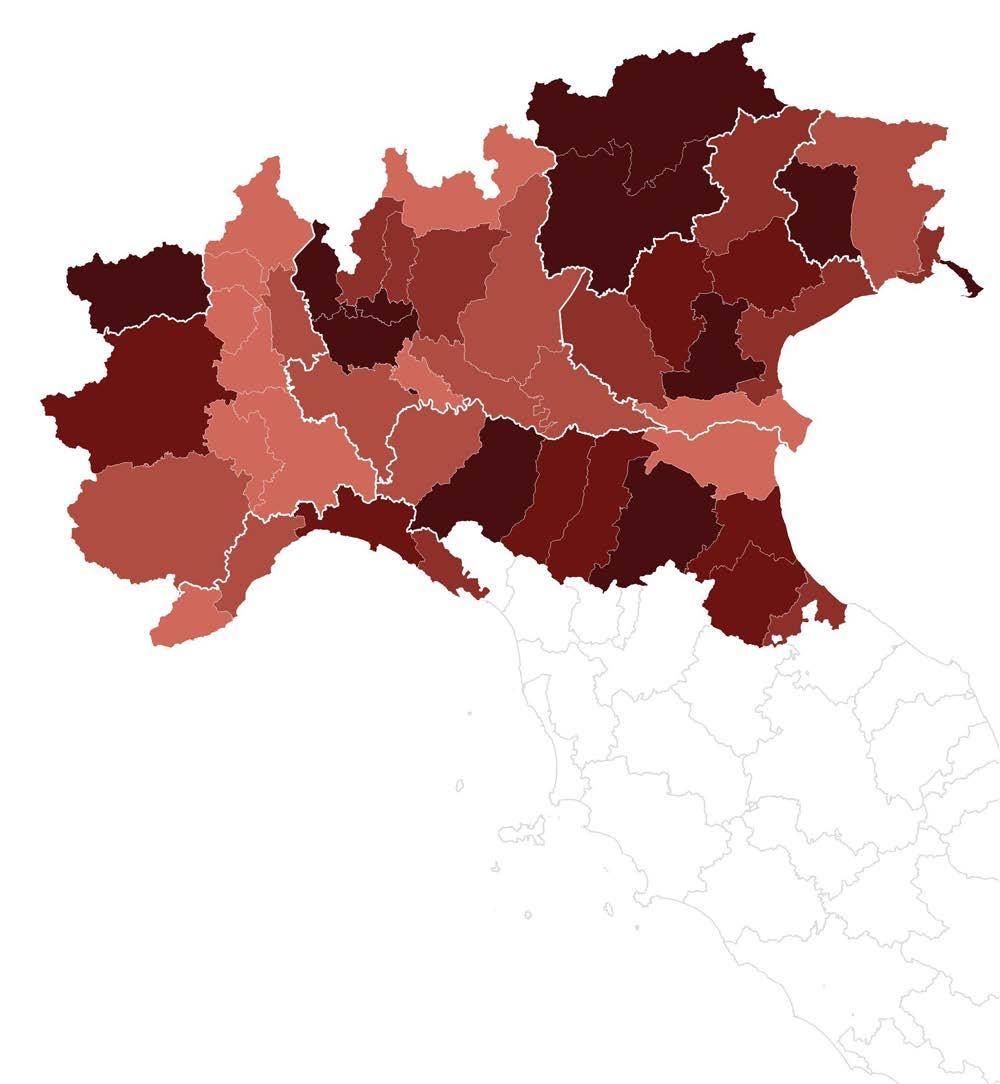

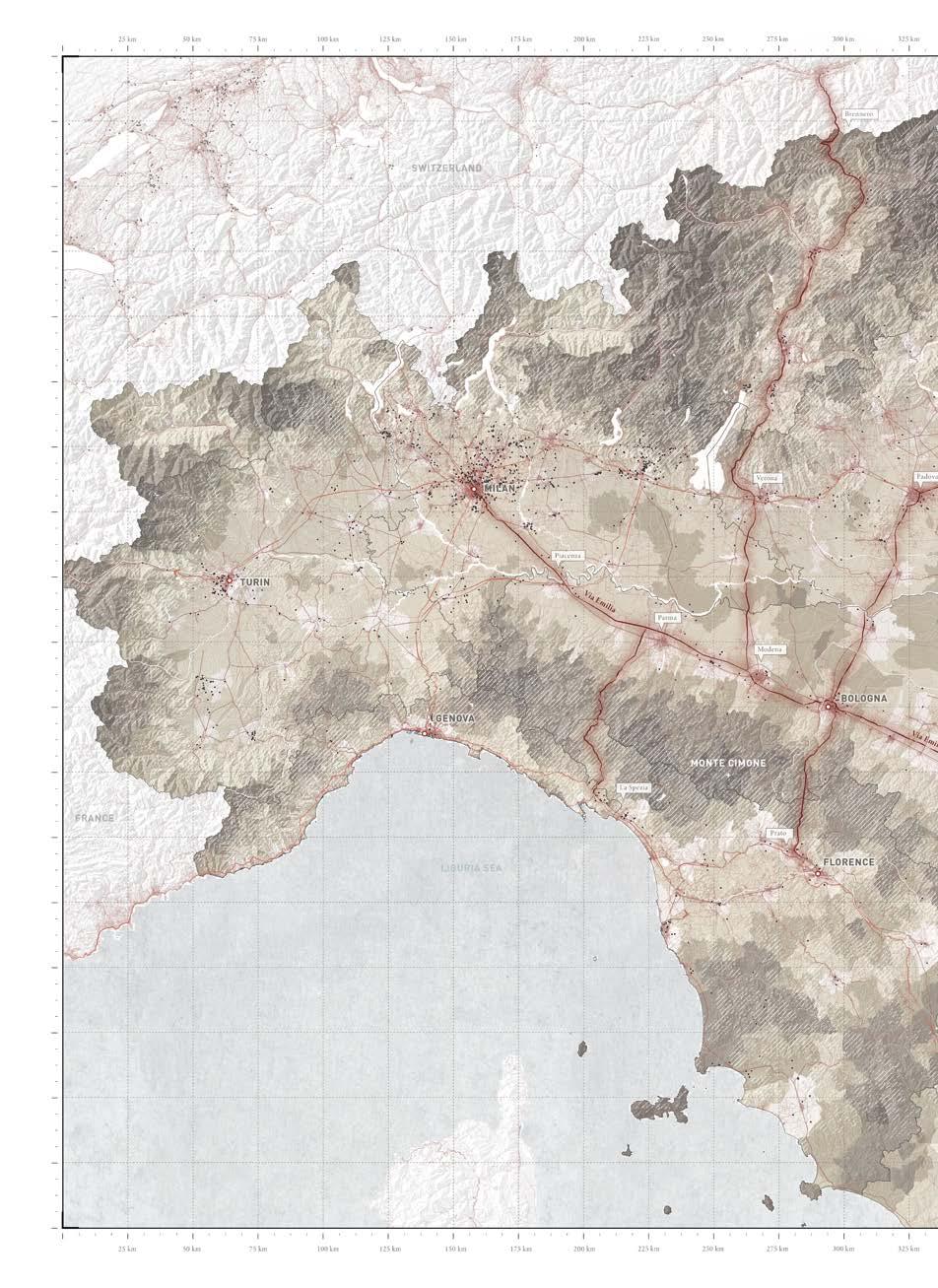

The current marginal condition of the Apennine Mountains.

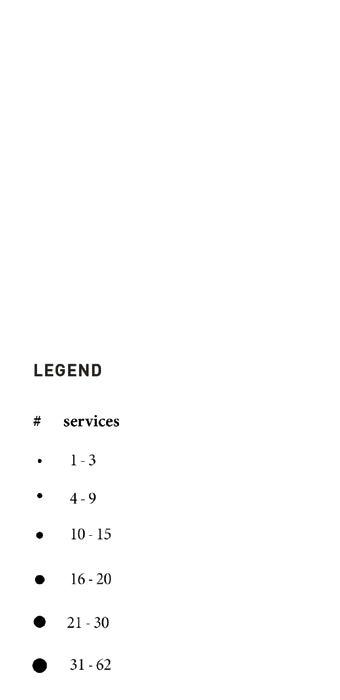

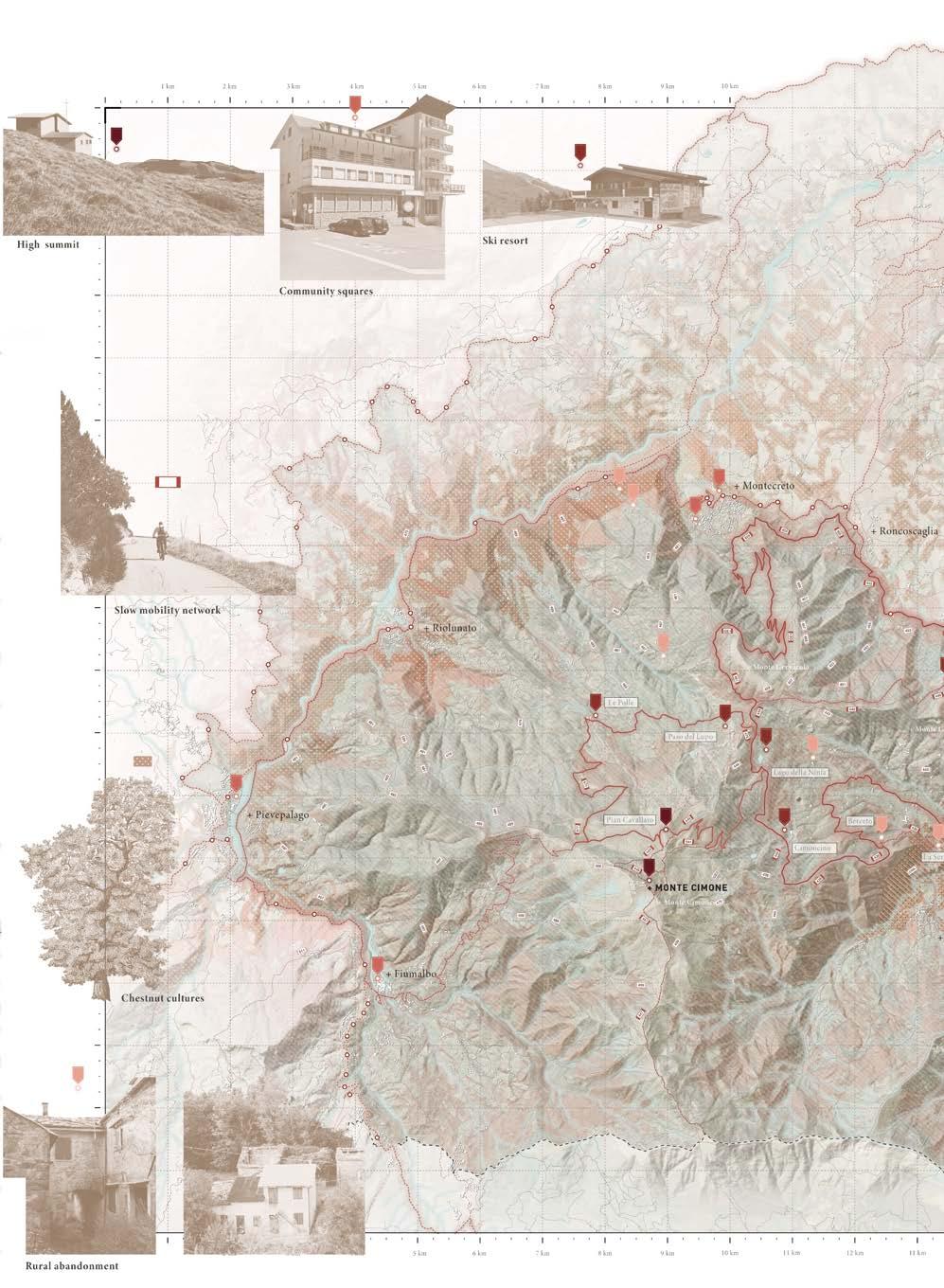

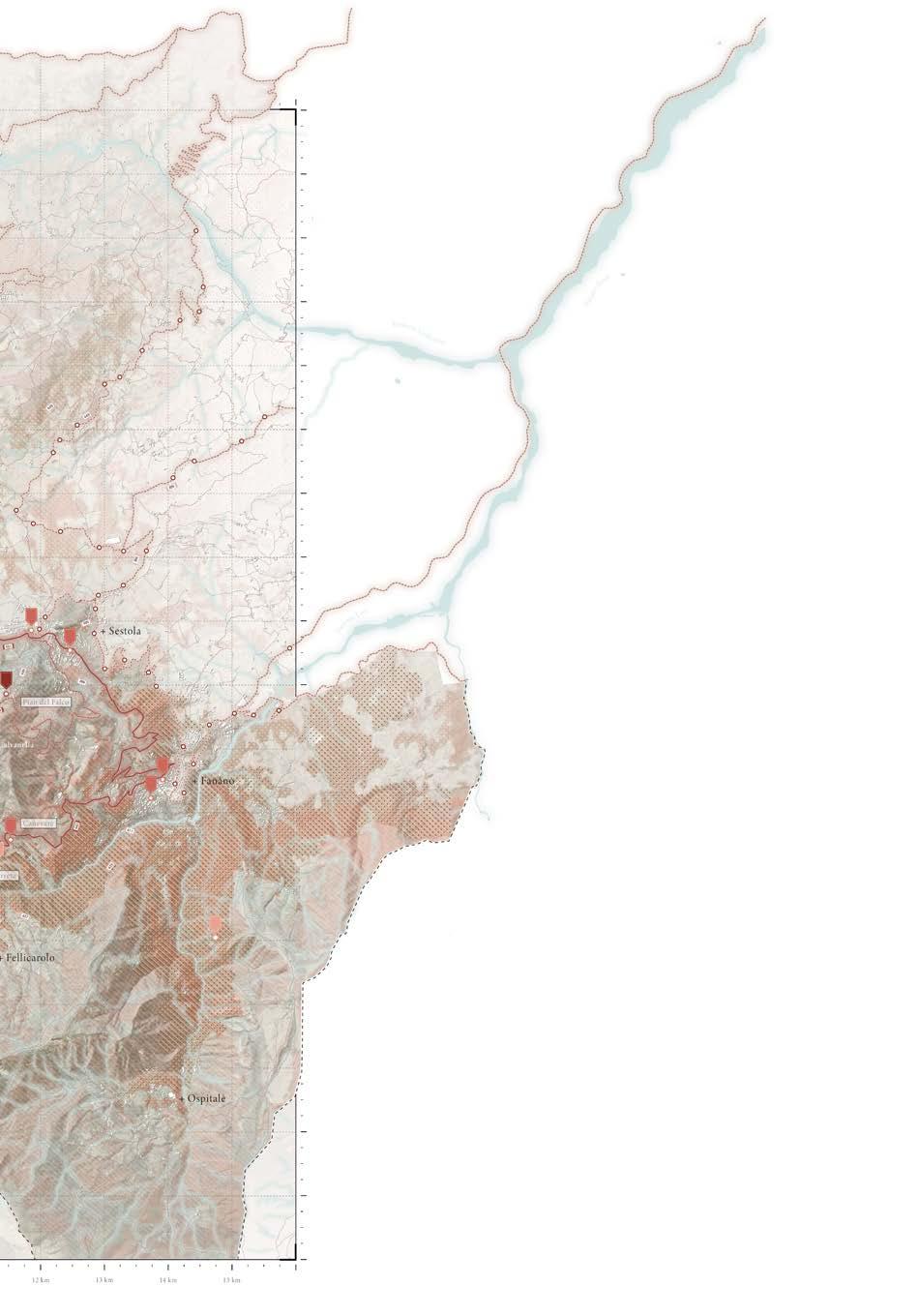

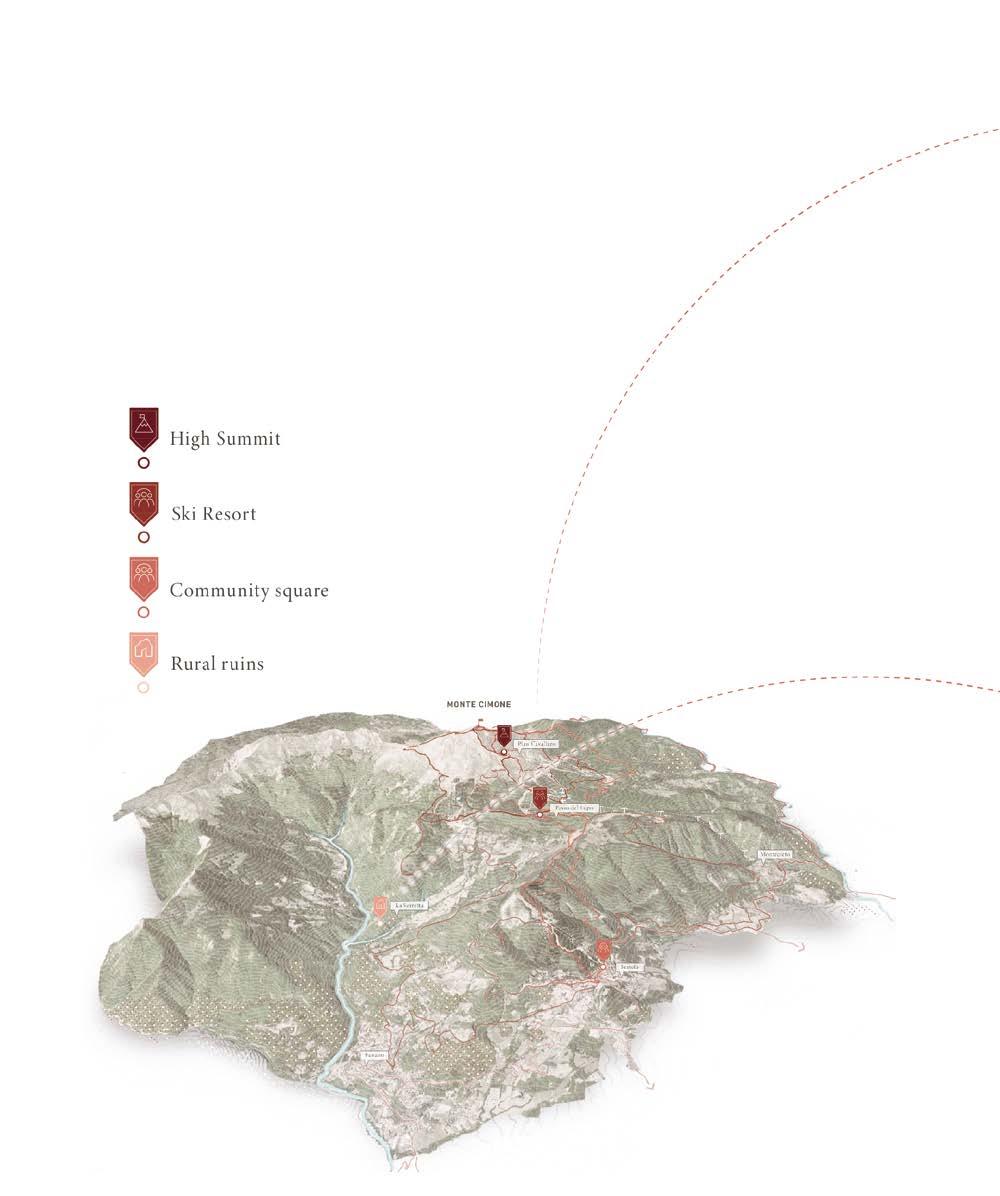

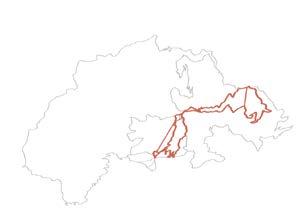

LEGEND

F- Ultraperiferico

E- Periferico

D- Intermedio

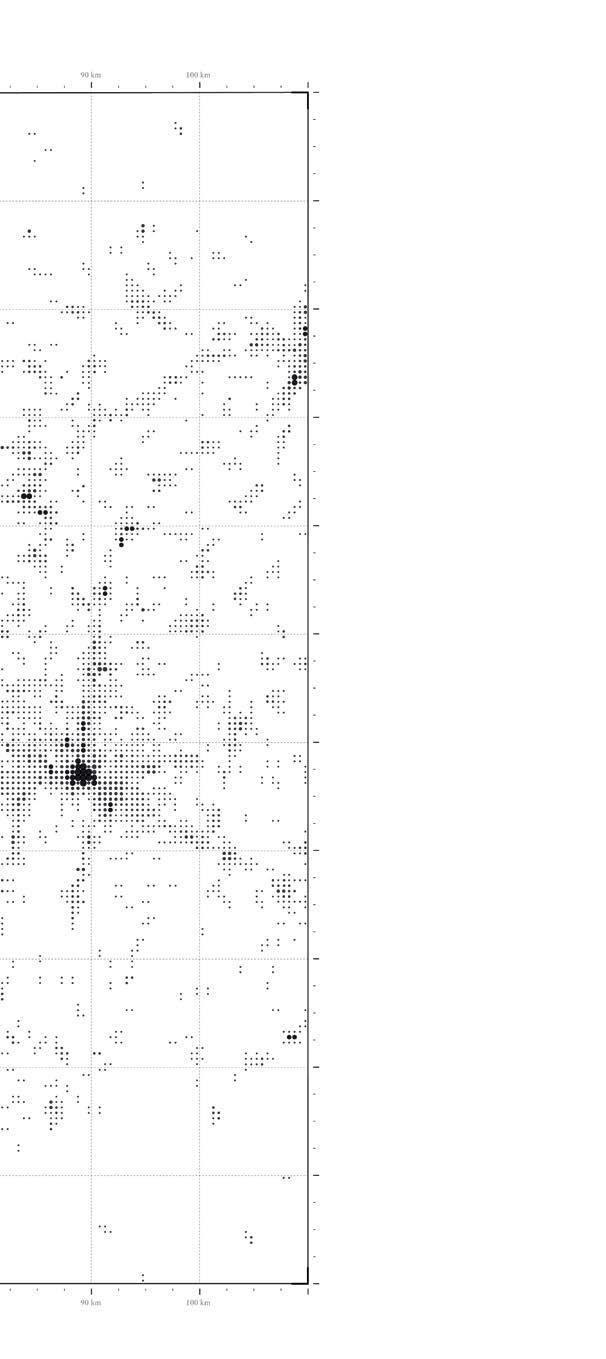

24 Fragile Mountains 0 km 100 km 200 km

Fig 1. Classification of regions according to the Inner Areas 2020.

Considering this current marginal condition as a starting point, it must be emphasized that in recent decades good development practices have been established and expanded for a cultural and territorial reconversion of countries. Taking advantage of the void created, it is necessary to encourage policies and practices of reappropriation of the space of small nuclei, of their relationships, of the network of knowledge, towards the definition of an economic and productive system that can once again give identity to the multiplicity of these places.

The change of perspective is fundamental, the landscape becomes a strategic element, both practical and theoretical at the same time, for the definition of a model of transformation capable of leading us towards a new equilibrium.

For a profound rethinking, two essential elements can be specified: the physical one of the territory and the social one of participation. Following the reasoning of Rossano Pazzagli, the land becomes a territory when it is a means of communication, a means, and an object of work, production, exchange, and cooperation. For reconstruction and re-appropriation of inland areas, one must retrace the lost roads through a vision capable of overturning the assumptions on which they were built, in order not to fall into the banality of imitation, but to open new horizons of economic growth capable of giving a new housing capacity necessary for a return to these places (2021). Countries are a common good, material and immaterial, only through the correct definition of priorities is it possible to reconstitute their identity, a place-based participatory process is fundamental to pursue these objectives.

Considerando questa condizione come punto di partenza, bisogna però sottolineare come negli ultimi decenni si siano stabilite ed ampliate buone pratiche di sviluppo per una riconversione culturale e territoriale dei paesi. Approfittando del vuoto creatosi, bisogna incentivare politiche e pratiche di riappropriazione dello spazio dei piccoli nuclei, delle loro relazioni, della rete di conoscenze, verso la definizione di un sistema economico e produttivo che possa nuovamente conferire identità alla molteplicità di questi luoghi.

Il mutamento di prospettiva è fondamentale, il paesaggio diventa elemento strategico, contemporaneamente pratico e teorico, per la definizione di un modello di trasformazione capace di condurci verso un nuovo equilibrio.

Ai fini di un profondo ripensamento si possono specificare due elementi imprescindibili: quello fisico del territorio e quello sociale della partecipazione. Seguendo il ragionamento di Rossano Pazzagli, la terra diventa un territorio quando è tramite di comunicazione, quando è mezzo e oggetto di lavoro, di produzioni, di scambi, di cooperazione. Per una ricostruzione e riappropriazione delle aree interne si devono ripercorrere le strade perdute attraverso una visione in grado di ribaltare gli assunti sui quali si erano costruite, per non cadere nella banalità dell’imitazione, ma per aprire nuovi orizzonti di crescita economica in grado di conferire una nuova capacità abitativa necessaria per un ritorno in questi luoghi (2021). I paesi sono un bene comune, materiale e immateriale, solo attraverso la corretta definizione di priorità è possibile ricostituire la loro identità, un processo partecipativo place-based è fondamentale per perseguire questi obiettivi.

25 Communities supporting Landscapes

26 Fragile Mountains

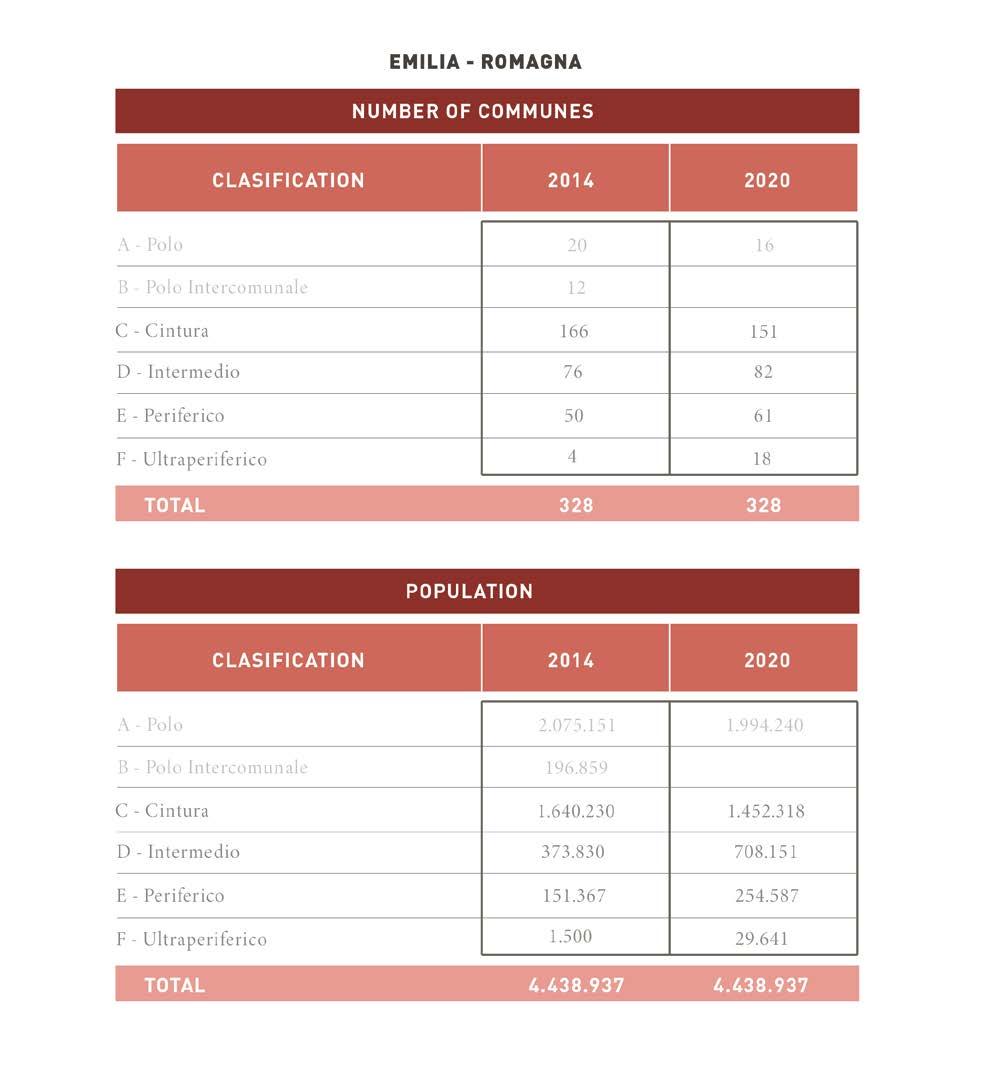

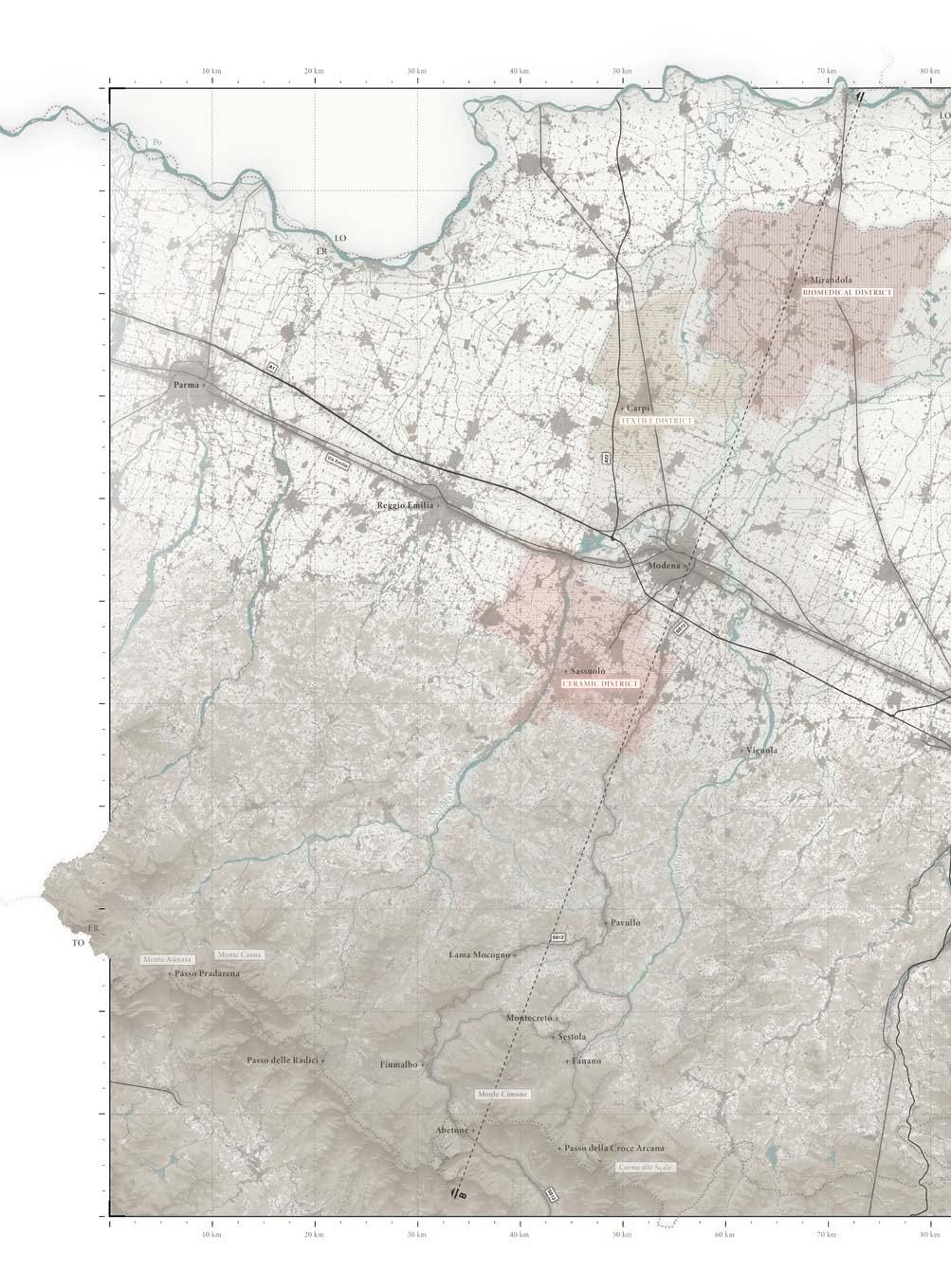

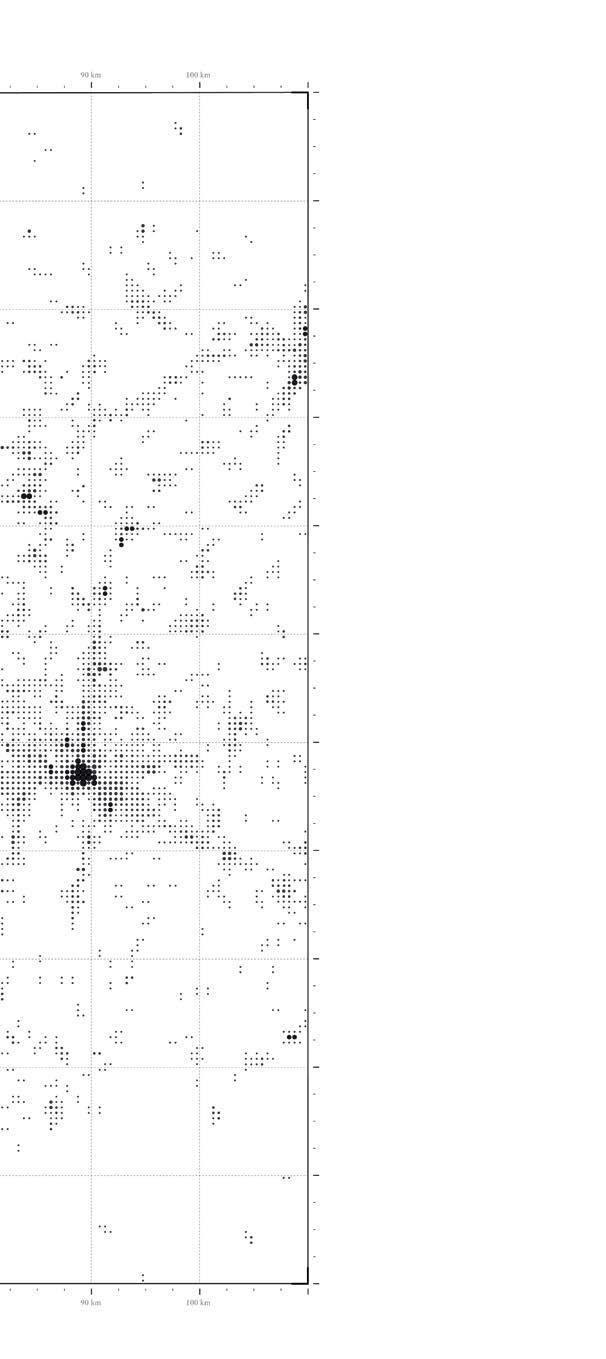

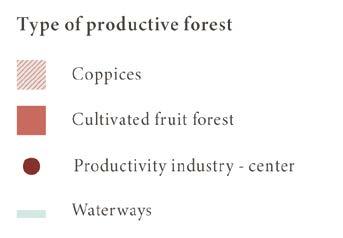

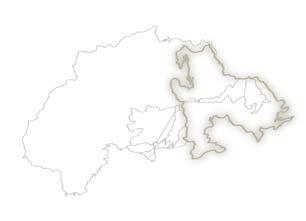

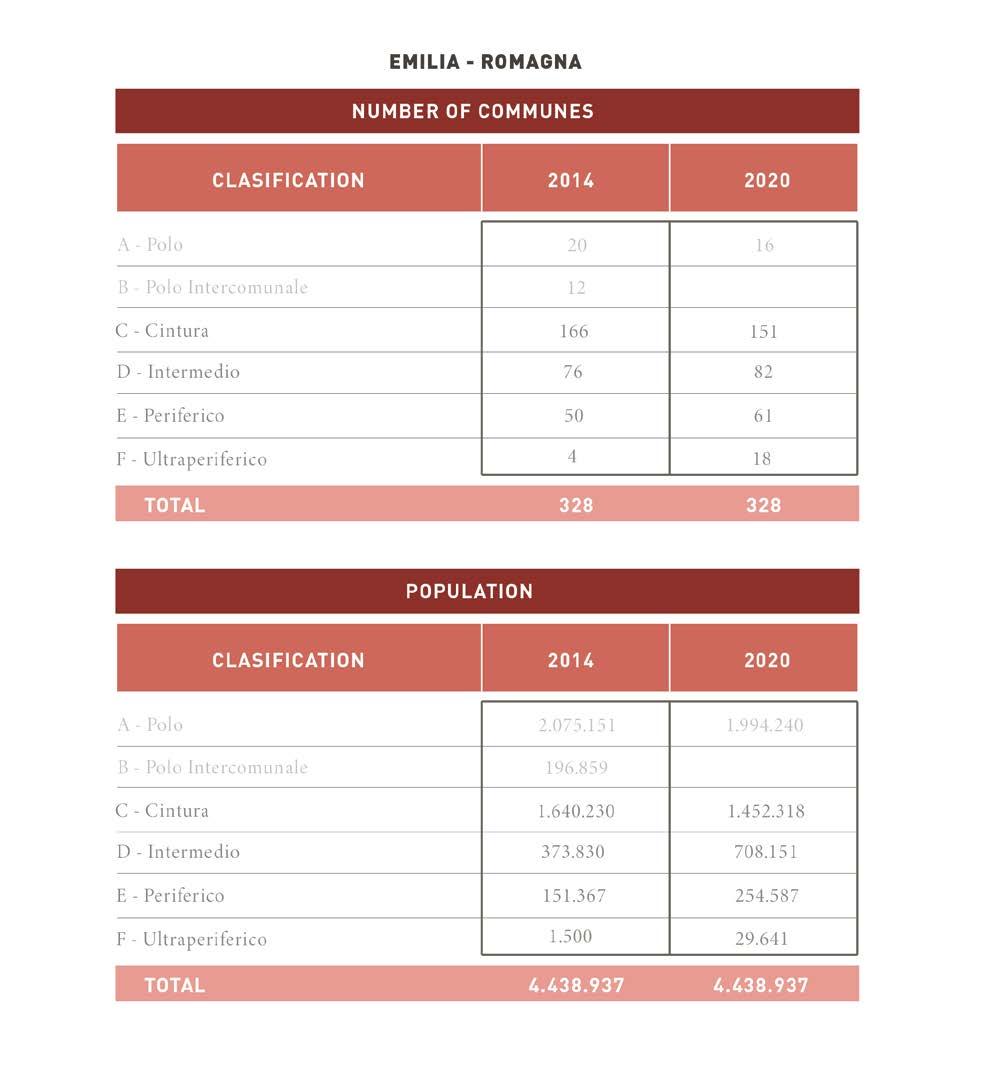

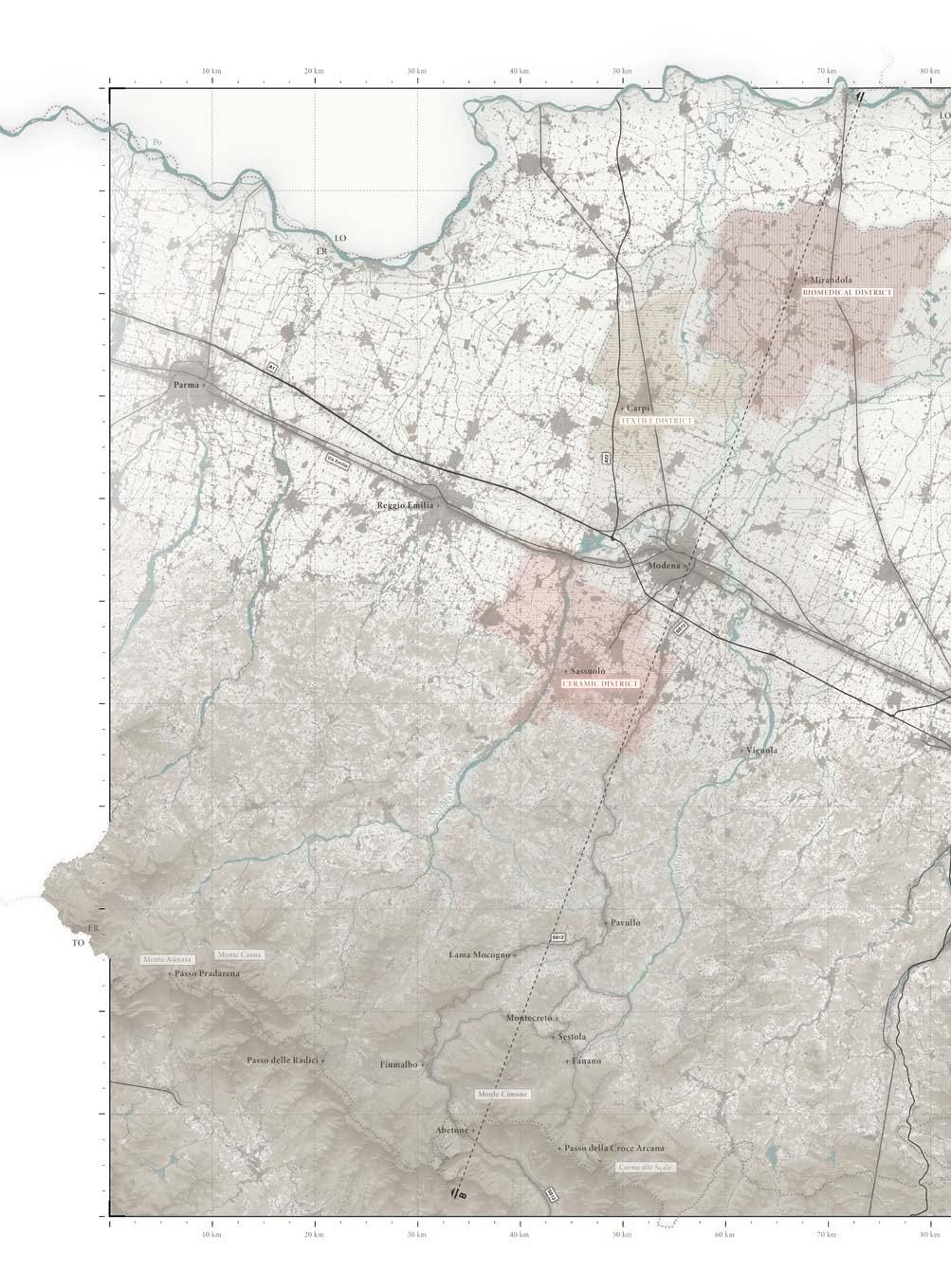

Fig 2. Classification of regions according to the Inner Areas 2020.

The history of Mountain economies.

Historical relevance is necessary for understanding a place’s economic and cultural sphere. The place is an anthropological concept, its understanding does not occur simply in terms of space, the place is a social and cultural construction, the result of an incessant production by its visitors and inhabitants. To understand the meaning of places, their soul, and their feelings, it is necessary to deepen their historicity about our gaze, to the space-time condition from which we observe them (Vito Teti, 2018).

The local development policies of territory with the characteristics of the Apennines can only be based on a direct exploration of the meaning of history. As Augusto Ciuffetti explains in his book “Appennino. Economie, culture e spazi sociali dal medioevo all’età contemporanea”, historical research can bring out the complexity of the relationships between the economic process, local resources, and the evolutionary process of which the Apennine localities have built and rebuilt their economic well-being (2019).

The foundations of Apennine society appear clearly defined already in the Middle Ages. During the Middle Ages, the Apennines were for a long time a vital and central area, at the forefront, the seat of technological innovations, and the scene of refined political, cultural, and religious elaborations. The Apennine reliefs were configured as an area continuously crossed by goods and people, places of experimentation and exchange.

During the centuries of the modern age, the areas of inland Italy underwent the downsizing of their economic role, they were surpassed in wealth and attractiveness by the cities of the coastal and flat belt. Despite this, the Apennines manage to resist the decline thanks to the extraordinary feature of income complementarity (Ciuffetti, 2019) that characterized the economy of every single peasant family: complementarity deriving from work in the fields, domestic industry, and specific activities related to forest management.

La rilevanza storica è necessaria per la comprensione della sfera economica e culturale di un luogo. Il luogo è un concetto antropologico, la sua comprensione non avviene semplicemente in termini di spazio, il luogo è una costruzione sociale e culturale, frutto di un’incessante produzione da parte dei suoi frequentatori ed abitanti. Per comprendere il senso dei luoghi, la loro anima e i loro sentimenti, occorre approfondirne la loro storicità in relazione al nostro sguardo, alla condizione spazio-tempo da cui li osserviamo (Vito Teti, 2018).

Le politiche di sviluppo locale di un territorio avente le caratteristiche degli Appennini non posso essere fondate che su un’esplorazione diretta del significato della storia. Come spiega Augusto Ciuffetti nel suo libro “Appennino. Economie, culture e spazi sociali dal medioevo all’età contemporanea”, la ricerca storica è in grado di far emergere la complessità delle relazioni tra il processo economico, le risorse locali e il processo evolutivo sulle quali le località appenniniche hanno costruito e ricostruito il loro benessere economico (2019).

Le basi della società appenninica appaiono ben chiaramente definite già nell’età medioevale. Nel corso del medioevo l’Appennino è per lungo tempo un’area vitale e centrale, all’avanguardia, sede di innovazioni tecnologiche e teatro di raffinate elaborazioni politiche, culturali e religiose. I rilievi appenninici si configuravano come un’area continuamente attraversata da merci e persone, luoghi di sperimentazione e di scambio.

Durante i secoli dell’età moderna, le aree dell’Italia interna subiscono il ridimensionamento del loro ruolo economico, esse vengono infatti superate in ricchezza e attrattività dalle città della fascia costiera e pianeggiante. Nonostante ciò, l’Appennino riesce a resistere al declino grazie alla straordinaria caratteristica di complementarità dei redditi (Ciuffetti, 2019) che caratterizzava

27 Communities supporting Landscapes

It En

28 Fragile Mountains

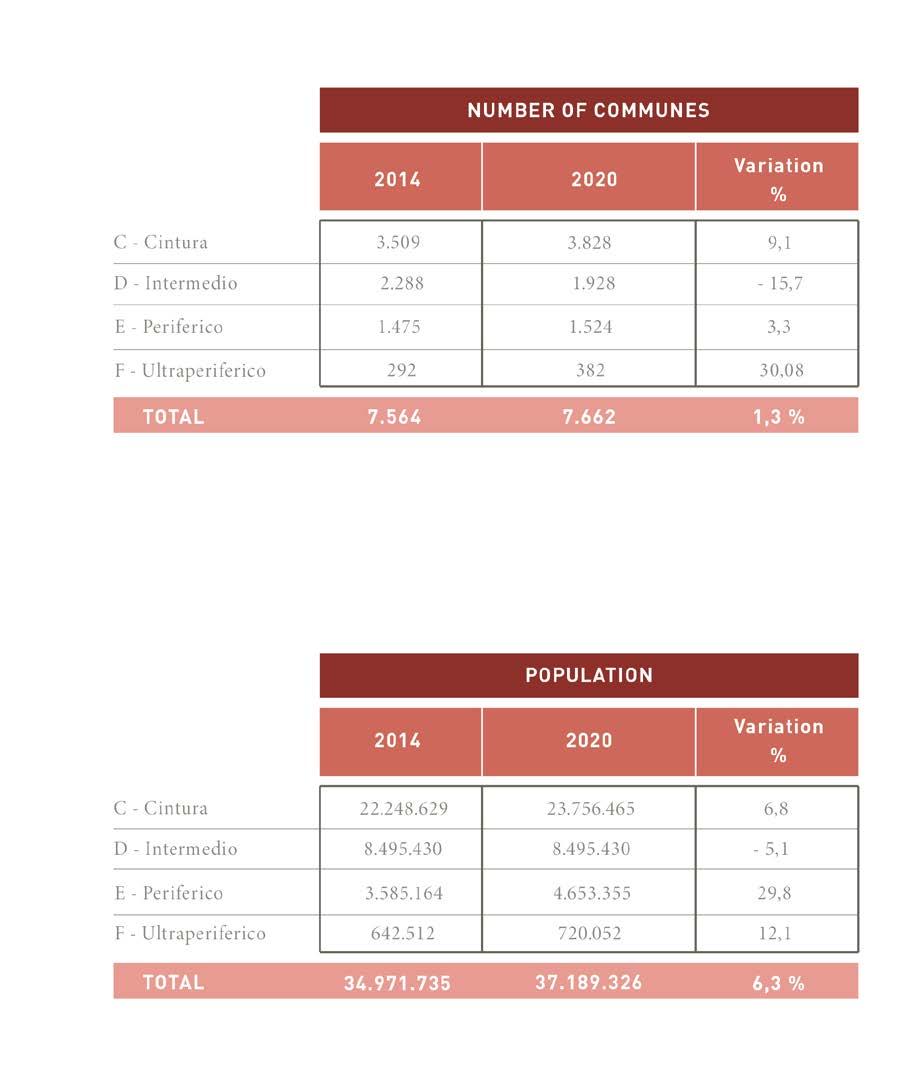

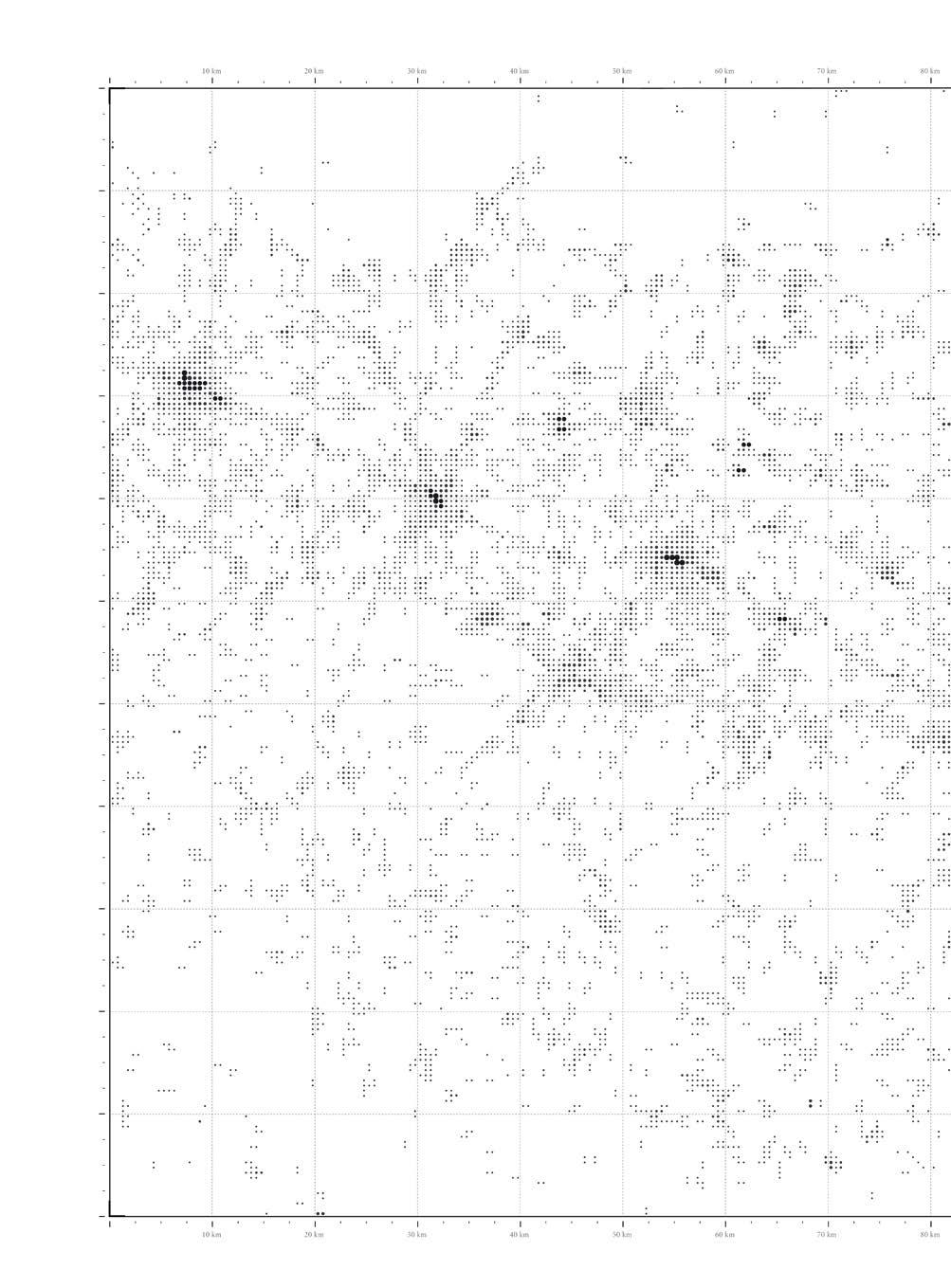

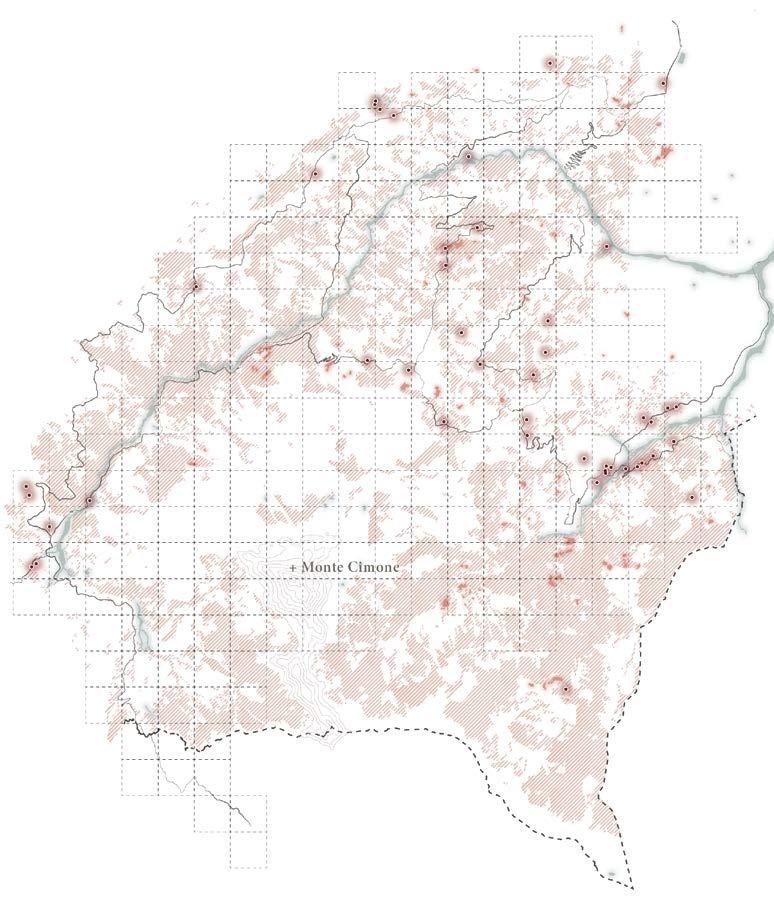

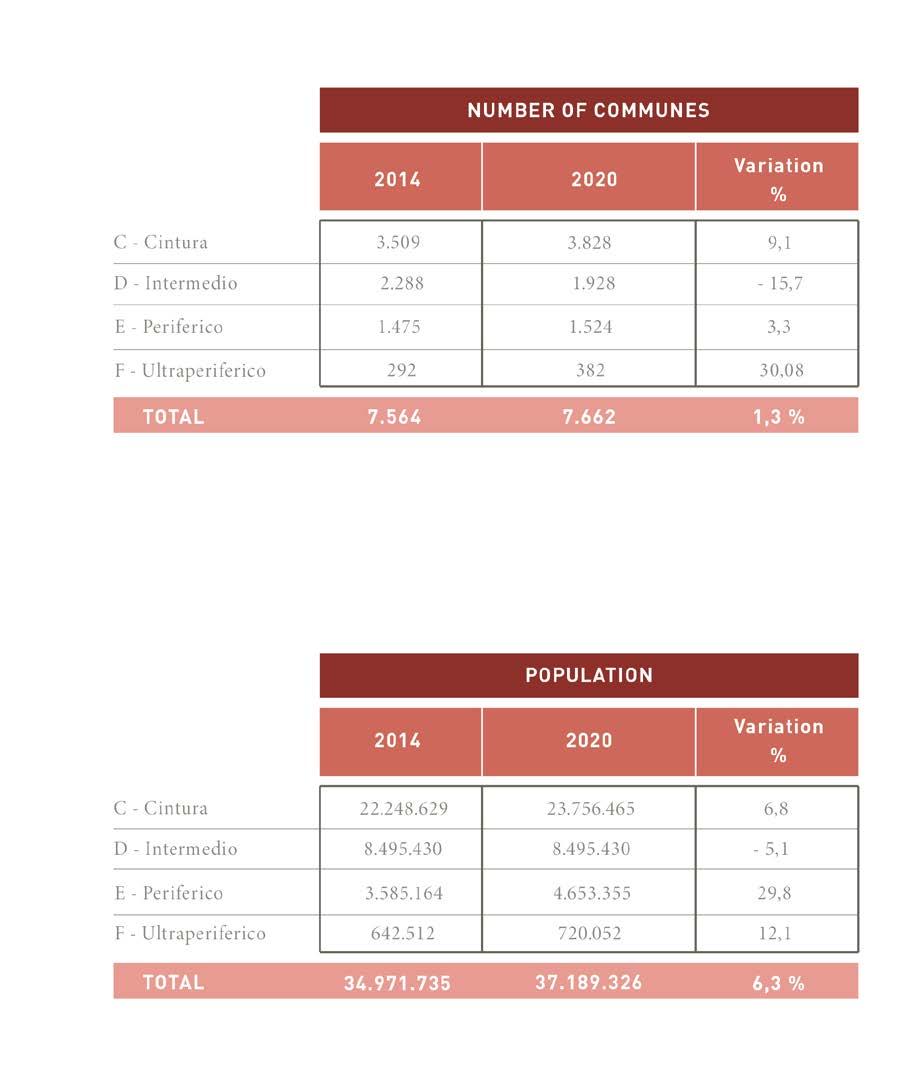

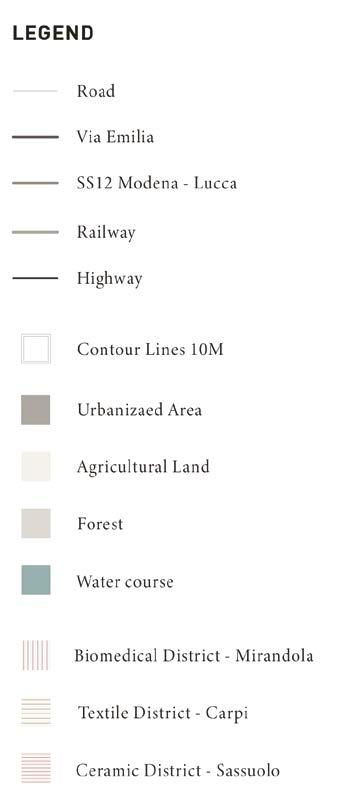

Fig 3. Comparison of number of municipalities and population distribution between 2014 and 2020.

The depopulation of the Apennines is a process that started only during the twentieth century, assuming the connotations of a real migratory context in the years of the economic boom of the second post-war period.

Instead, between the end of the twentieth century and the beginning of the new millennium, there is a sort of rediscovery of the Apennine mountains, a place of new opportunities and localized recovery paths.

As described by Lanzani and Zanfi in “Riabitare l’Italia”, the 2008 economic crisis acted as an accelerator against those phenomena that had already timidly emerged in the previous fifteen years. A new trait seems to emerge concerning the more consolidated dynamics of “emptying” and “filling” of the urbanized territory, differentiated movements emerge that molecularly invest the internal territories (2018). Different dynamics seem to characterize the countryside and small towns that had experienced a strong exodus. Alongside definitive abandonments, countertrend phenomena multiply: migrations by choice of return repopulate some of these realities. Processes of social innovation find in these contexts material and intangible assets of quality to build different futures.

The future of the Apennine spaces also lies in the rediscovery of trades, production processes, economic activities, resource management methods, lifestyles, and cultural forms which, drawing on a consolidated tradition, can be renewed and inserted into the most advanced economic dynamics of our contemporaneity.

The link between culture and territory must return to the center of attention. By linking history, culture, and society, it is possible to make cultural and environmental heritage available again, made up of tangible and intangible, material and immaterial elements.

History is useful if it can look to the future, nourishing an ever-renewed identity, rather than reproducing an ideal world that has now passed, which was not so ideal (Pazzagli, 2021).

l’economia di ogni singola famiglia contadina: complementarità derivante dal lavoro nei campi, dall’industria domestica e da specifiche attività legate alla gestione dei boschi.

Lo spopolamento degli Appennini è un processo attivatosi solo nel corso del Novecento, assumendo i connotati di un vero e proprio contesto migratorio negli anni del boom economico del secondo dopoguerra. Invece, tra la fine del Novecento e l’inizio del nuovo millennio, si evidenzia una sorta di riscoperta della montagna appenninica, luogo di nuove opportunità e localizzati percorsi di ripresa.

Come descritto da Lanzani e Zanfi in “Riabitare l’Italia”, la crisi economica del 2008 ha agito da acceleratore nei confronti di quei fenomeni già timidamente emersi nel quindicennio precedente. Sembra emergere un tratto nuovo rispetto alle più consolidate dinamiche di “svuotamento” e “riempimento” del territorio urbanizzato, affiorano movimenti differenziati che investono i territori interni in maniera molecolare (2018). Dinamiche diverse sembrano caratterizzare le campagne e i piccoli centri che avevano conosciuto un forte esodo. Accanto ad abbandoni definitivi, si moltiplicano fenomeni in controtendenza: migrazioni per scelta di ritorno ripopolano alcune di queste realtà. Processi di innovazione sociale trovano in questi contesti beni materiali e immateriali di qualità per costruire futuri differenti.

Il futuro degli spazi appenninici risiede anche nella riscoperta di mestieri, processi produttivi, attività economiche, modalità di gestione delle risorse, stili di vita, forme culturali che, attingendo a una consolidata tradizione, si possono rinnovare e inserire nelle più avanzate dinamiche economiche della nostra contemporaneità.

Il legame tra cultura e territorio deve tornare al centro dell’attenzione. Collegando storia, cultura e società è possibile rendere nuovamente disponibile un patrimonio sia culturale che ambientale, composto da elementi tangibili e intangibili, materiali e immateriali.

29 Communities supporting Landscapes

As previously stated, there are two fundamental elements, the integration of which appears necessary for the construction of new perspectives for the future: the materiality of the territory and the sociability of participation. The greatest challenge that we are required to face, in this research project as well as in the decision-making process of the national political landscape, lies in the ability to influence territorial choices capable of adding value and importance to the cooperative dimension. The design dimension which this historical time should develop has both a reconstruction and a propositional value, through the definition of a landscape design capable of relating culture, history, and society in a new dimension that positively influences and for a long time those areas that today are perceived as the back of the country.

La storia è utile se è capace di guardare al futuro, di alimentare una sempre rinnovata identità, anziché riprodurre un mondo ideale ormai trascorso, che poi tanto ideale non era (Pazzagli, 2021).

Come già precedentemente affermato, sono presenti due elementi fondamentali, la cui integrazione appare necessaria per la costruzione di nuove prospettive per il futuro: la materialità del territorio e la socialità della partecipazione. La maggiore sfida che siamo tenuti ad affrontare, in questo progetto di ricerca come nel processo decisionale del panorama politico nazionale, risiede nella capacità di influenzare scelte territoriali in grado di aggiungere valore ed importanza alla dimensione cooperativa. La dimensione progettuale che questo momento storico dovrebbe sviluppare ha una valenza sia ricompostiva che propositiva, attraverso la definizione di un disegno di paesaggio capace di relazionare cultura, storia e società in una nuova dimensione che influenzi positivamente e per lunga durata quelle aree che oggi vengono percepite come il retro del paese.

30 Fragile Mountains

Fig 4. Chestnut harvest in Montecreto.

Between abandonment and Reconquista.

It En

Analyzing the practice of departure, reference is inevitably also made to that of returning, while if you consider the practice of abandonment, you can always contrast that of resistance.

Abandonment and ruins are constant and recurring elements, characteristic of the inland areas of the Italian peninsula. Many villages and neighboring districts that are now weak and partly forgotten, their territories and their communities must be profoundly frail with depopulation, abandonment, and negligence which is removing this heritage from the memory of current generations. The rediscovery of the values of the historical and cultural heritage, together with the reconstruction of shared memory, is important to look at the past and the future of the territories to be witnessed at the same time.

How can internal Italy be re-inhabited? The question refers to a question of survival, the answer involves the renewal of our ability to give meaning and value to these territories and the ability to see their latent potential. A change of perspective capable of putting the territory as a common good for the community in the foreground is indispensable (Pazzagli, 2021).

The territory is a common good, the landscape is a resource. The mountain areas are luxuriant places of excellence, with territorial assets and ecosystem services that are important for safeguarding the Italian system. In this direction, it is necessary to give importance and value to mountain areas by protecting and making them attractive and habitable through multifunctional development. It is a question of identifying local microsystems, characteristic of a specific historical identity, which, through a process of territorial reorganization, become a guide for development (Ciuffetti, 2019).

Analizzando la pratica della partenza si fa inevitabilmente riferimento anche a quella del ritorno, mentre se si considera la pratica dell’abbandono si può sempre contrapporre quella della resistenza.

L’abbandono e le rovine sono elementi costanti e ricorrenti, caratteristici delle aree interne della penisola italiana. Molti borghi e villaggi appaiono oggi deboli e in parte dimenticati, i loro territori e le loro comunità presentano profondi segni di fragilità, vi è la necessità di contrastare il progressivo spopolamento, l’abbandono e l’incuria che sta eliminando questo patrimonio dalla memoria dalle attuali generazioni. La riscoperta dei valori del patrimonio storico e culturale, insieme alla ricostruzione di una memoria condivisa, è importante per volgere lo sguardo contemporaneamente al passato e al futuro dei territori che si vuole testimoniare.

In che modo può essere riabitata l’Italia interna? La domanda fa riferimento ad una questione di sopravvivenza, la risposta prevede il rinnovamento della nostra capacità di conferire senso e valore a questi territori e l’abilità di intravederne le potenzialità latenti. È indispensabile un cambiamento di prospettiva capace di mettere in primo piano il territorio inteso come bene comune per la comunità (Pazzagli, 2021).

Il territorio è un bene comune, il paesaggio è una risorsa. Le aree montane sono luogo rigoglioso di eccellenze, beni territoriali e servizi ecosistemici importanti per la salvaguardia del sistema Italia. In questa direzione bisogna dare importanza e valore alle aree montane proteggendole, tutelandole e rendendole attrattive ed abitabili attraverso uno sviluppo multifunzionale. Si tratta di individuare dei microsistemi locali, caratteristici di una specifica identità storica, che attraverso un percorso di riorganizzazione del territorio diventino guida per lo sviluppo (Ciuffetti, 2019).

31 Communities supporting Landscapes

Common goods can help strengthen the feeling of belonging to a place and participate in the definition of economies and production processes capable of generating monetary income, supporting local communities, and participating in their attractiveness.

The best experiences of regeneration taking place in the internal areas of our country show that it is possible to build fires capable of acting as accelerators of the social and economic development of the territory by intertwining themes such as culture, community health, and small local services, training and access to new technologies, support for micro-economies.

The contraction that characterizes the internal areas can be contrasted with the three rehabilitation dynamics that Arturo Lanzani and Francesco Curci express contrast (2018).

I beni comuni possono contribuire a rafforzare il sentimento di appartenenza di un luogo e possono partecipare alla definizione di economie e processi produttivi in grado di generare redditi monetari, per supportare le comunità locali e partecipare alla loro attrattività.

Le migliori esperienze di rigenerazione in atto nelle aree interne del nostro paese mostrano che si possono costruire fuochi capaci di agire da acceleratori dello sviluppo sociale ed economico del territorio proprio intrecciando temi come la cultura, la salute di comunità e i piccoli servizi locali, la formazione e l’acceso alle nuove tecnologie, il sostegno alle microeconomie.

La contrazione che caratterizza le aree interne può essere contrapposta dalle tre dinamiche riabitative che Arturo Lanzani e Francesco Curci esprimono come in controtendenza (2018).

32 Fragile Mountains

Fig 5. Picking blueberries with the typical utensil.

The first category refers to villages well connected to the piedmont and valley floor urban realities, fundamental relationships for access to basic services. For establishing and maintaining a community, accessibility to certain services such as health and personal services, schools, and community services, without which families cannot think of settling in a place in a lasting way, is essential.

A second dynamic recalls those processes of social innovation conducted by mountain residents or by all those who choose a life in the Apennines, in some cases a return to their native land, in other situations a decision in favor of new and unexplored perspectives, towards the discovery of new life and work projects.

A third recognizable trend is that linked to immigrants who re-inhabit marginal villages, by choice of life or momentary necessity, reactivating agro-pastoral or mining economies previously abandoned by their native populations.

If the following abandonment, it would not make sense to try to recover a past that has fallen into ruin tout court, what should be attempted is a refounding of places to get to know them, rethink them and take care of them to rediscover their own identity. Rebuilding places and taking care of them means welcoming, hosting, producing, making countries beautiful, transmitting the sense of living, and making places live towards the construction of a new memory (Teti, 2018).

Una prima categoria fa riferimento ai borghi ben connessi alle realtà urbane pedemontane e di fondovalle, relazioni fondamentali per l’accesso ai servizi di base. Per l’insediamento e il mantenimento di una comunità è infatti imprescindibile l’accessibilità a certi servizi quali quelli sanitari e alla persona, scuole e servizi di prossimità senza i quali le famiglie non possono pensare di stabilirsi in un luogo in modo duratura.

Una seconda dinamica richiama quei processi di innovazione sociale condotti dai residenti montani o da tutti coloro che scelgono una vita in Appennino, in certi casi un ritorno alla terra natia, in altre situazioni una decisione a favore di nuove e inesplorate prospettive, verso la scoperta di nuovi progetti di vita e di lavoro.

Un terzo andamento riconoscibile è quello legato agli immigrati che riabitano borghi marginali, per scelta di vita o necessità momentanea, riattivando economie agropastorali o minerarie precedentemente abbandonate dalle popolazioni natie.

Se a seguito dell’abbandono non avrebbe senso tentare di recuperare tout court un passato caduto in rovina, quello che si dovrebbe tentare è una rifondazione dei luoghi per conoscerli, ripensarli e prendersene cura per riscoprirne una loro identità. Rifondare i luoghi e averne cura significa accogliere, ospitare, produrre, rendere belli i paesi, trasmettere il senso di vivere e far vivere i luoghi verso la costruzione di nuova memoria (Teti, 2018).

33 Communities supporting Landscapes

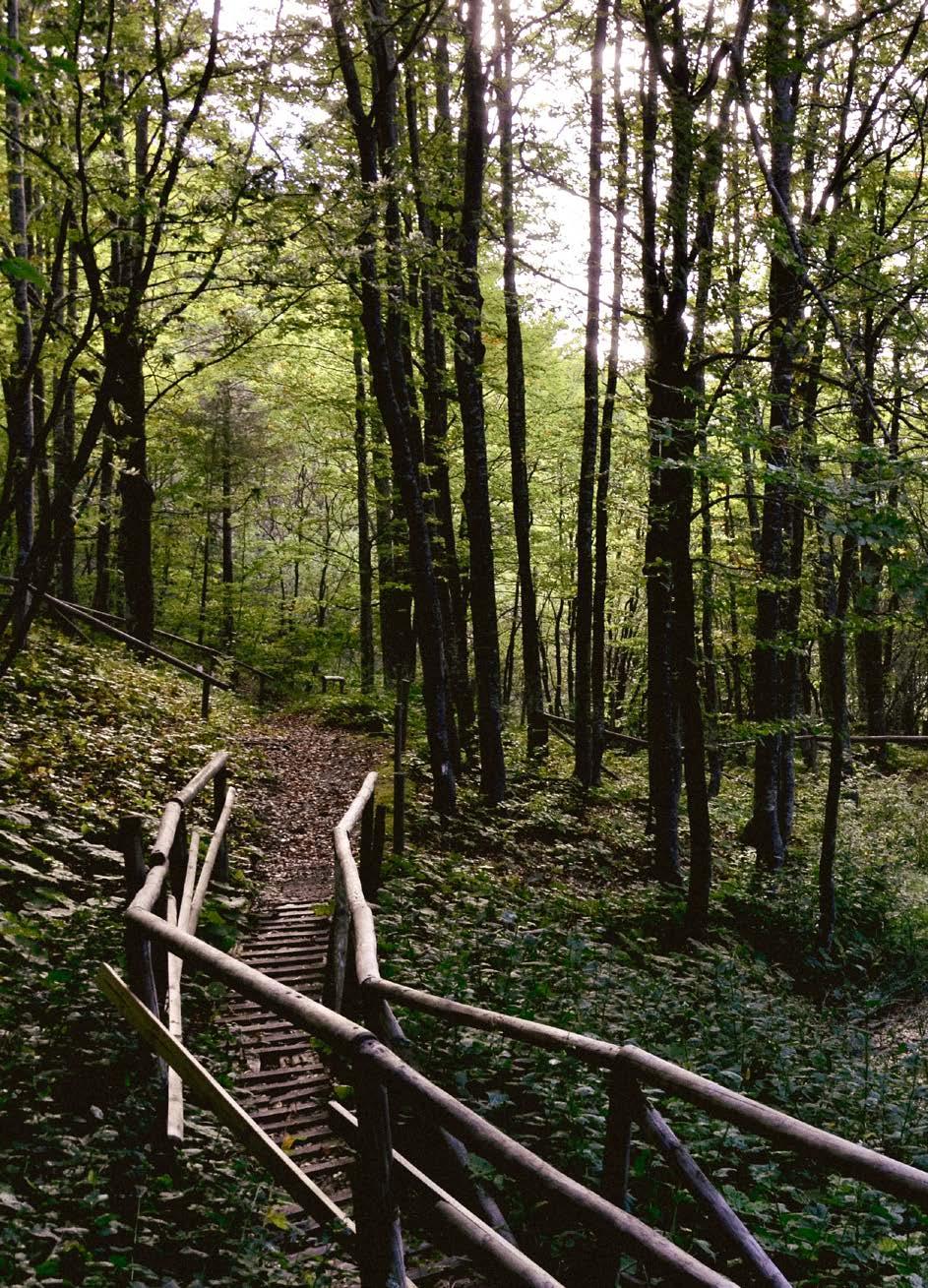

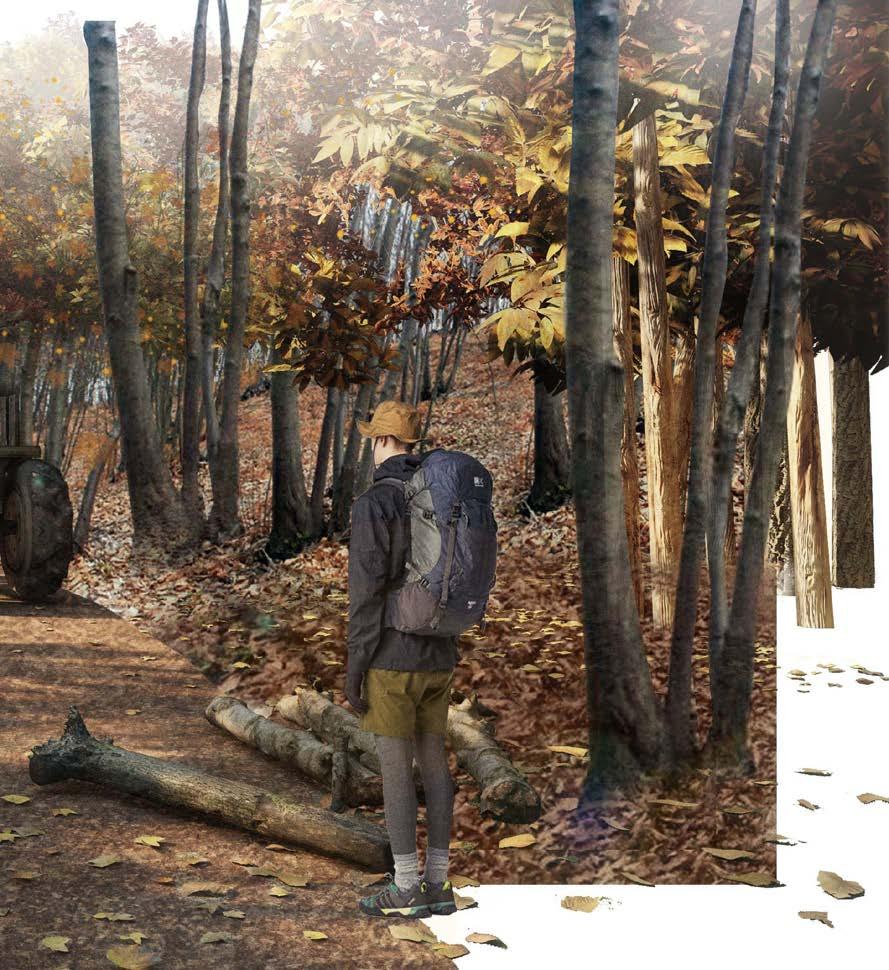

Ruins and Forest as rural Mountain heritage.

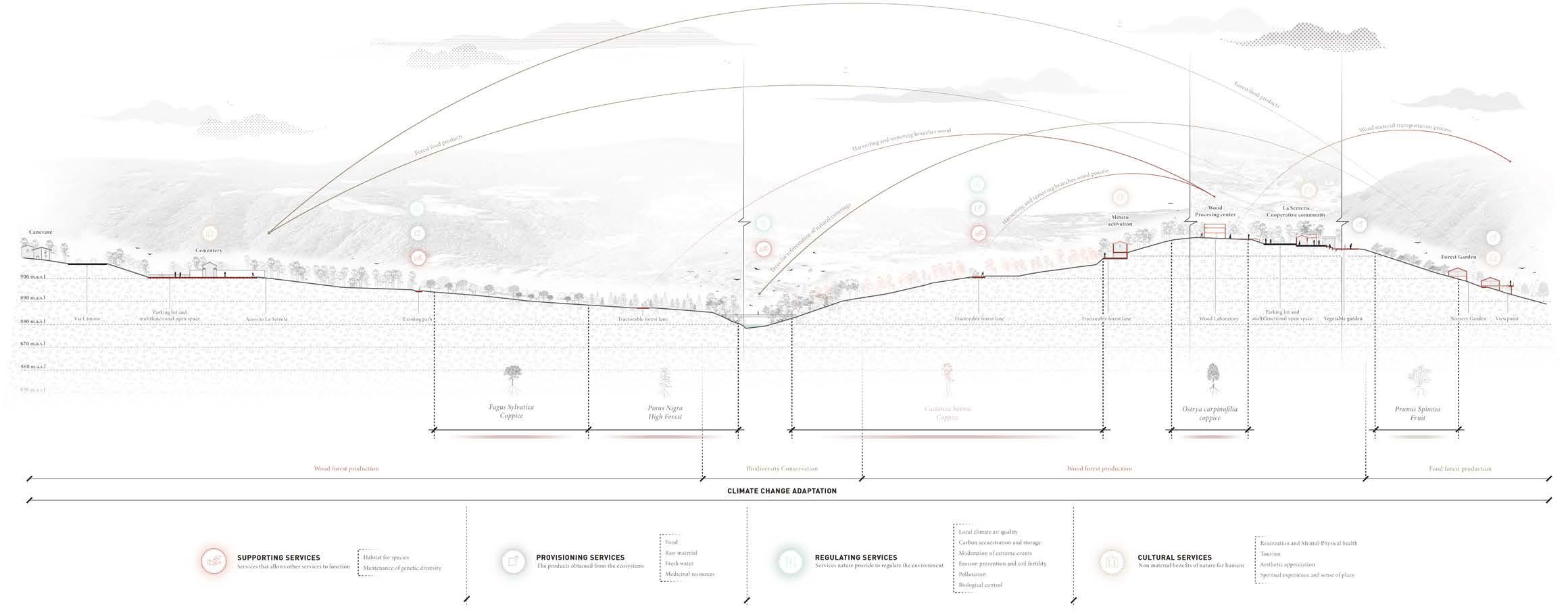

The forms of the landscape handed down to us until today are nothing more than the result of the centuries-old process of territorialization that the agro-pastoral reforms have produced on the territory. As Emilio Sereni explains in his milestone “Storia del paesaggio agrario italiano”, in most cases the instrument of territorial construction had been agriculture (2010).

In just one century, Italian society has gone from an agro-forestry-pastoral economy to an economy of global consumption, in which, alongside the demand for renewable raw materials, the demand for ecosystem and environmental services has increased. Also, during the twentieth century, alongside the dynamics of depopulation and aging of the population that have produced a progressive abandonment of the building heritage in inland areas, there have been processes of abandonment and aging of the forests that have caused problems of stability of the slopes and vulnerability in case of fire.

As previously addressed, dealing with the social and economic complexities of the Apennine Mountain areas is the key to building authentic and effective territorial management experiences towards the construction of unprecedented relationships with the natural environment and inspiring lifestyles and actions capable of protecting the landscape. The mismanagement of the woods and the abandonment of the building stock are negligent tendencies towards the territory, but they are the same ones that offer numerous opportunities and possibilities for the development of new strategies for a rethinking of the roles that these elements can have in the landscape system.

If in some cases the old Apennine settlements continue to be inhabited, the abandonment of the soils used for agro-pastoral activities, of coppice woods, and a minute hydraulic-forest arrangement have made those uses possible and have consolidated the mountain territory.

Le forme del paesaggio tramandateci fino ad oggi non sono altro che il risultato del secolare processo di territorializzazione che le riforme agro-pastorali hanno prodotto sul territorio. Come spiega Emilio Sereni nella sua pietra miliare “Storia del paesaggio agrario italiano”, nella maggioranza dei casi lo strumento di costruzione territoriale era stata l’agricoltura (2010).

In un solo secolo, la società italiana è passata da un’economia agro-silvo-pastorale a un’economia di consumi globali, in cui accanto alla domanda di materie prime rinnovabili è aumentata la domanda di servizi ecosistemici ed ambientali. Sempre nel corso del Novecento, accanto alle dinamiche di spopolamento e invecchiamento della popolazione che hanno prodotto un progressivo abbandono del patrimonio edilizio nelle aree interne, si sono verificati processi di abbandono e invecchiamento delle foreste che hanno provocato problemi di stabilità dei versanti e di vulnerabilità in caso di incendi.

Come già precedentemente affrontato, trattare le complessità sociali ed economiche delle aree montane appenniniche è la chiave per costruire autentiche ed efficaci esperienze di gestione territoriale verso la costruzione di inediti rapporti con l’ambiente naturale e per ispirare stili di vita ed azioni capaci di tutelare il paesaggio. La mal gestione dei boschi e l’abbandono del patrimonio edilizio sono tendenze negligenti nei confronti del territorio, ma sono le stesse che offrono numerose opportunità e possibilità verso lo sviluppo di nuove strategie per un ripensamento dei ruoli che questi elementi possono avere nel sistema paesaggio.

Se in alcuni casi i vecchi insediamenti appenninici continuano ad essere abitati, appare sempre più generalizzato l’abbandono dei suoli utilizzati per le attività agro-pastorali, dei boschi cedui e di una minuta sistemazione idraulico-forestale che ha reso possibile quegli usi e ha consolidato il territorio montano.

34 Fragile Mountains

It

En

Forests are an important resource that should be protected, but that must be managed, otherwise, the results are those that can be observed today: forests capable of producing less and less material goods and environmental services, exposed to the risk of aging and degradation.

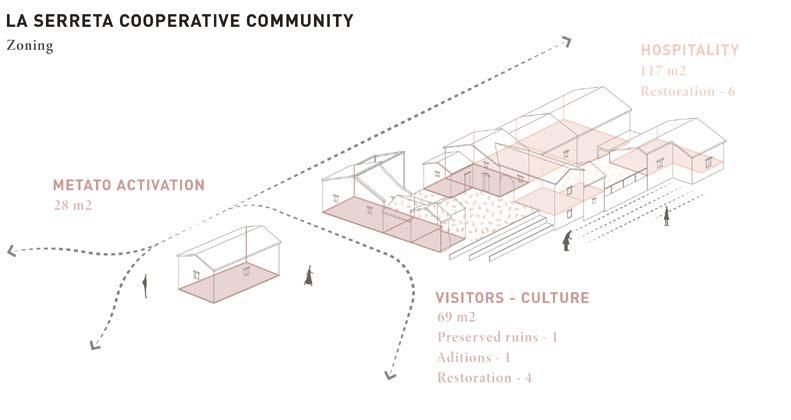

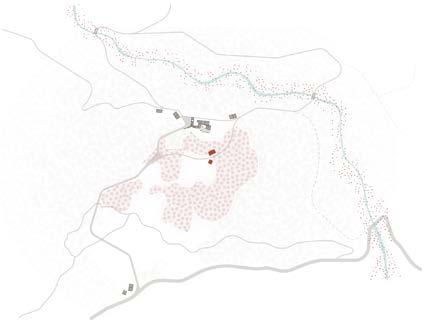

Following the national directives on the management of forest territories, they should be borne by the regions through the drafting of specific management plans. At present, however, a very significant part of public forests is not managed by the plans in force, many properties are underused or abandoned, and the forest is not a priority on public agendas. Following the reasoning of Davide Pattanella in “Riabitare l’Italia”, in this context, the private sector could play a fundamental role in the development of initiatives to enhance the local supply chains of wood and spontaneous forest products (mushrooms, truffles, chestnuts, pine nuts, aromatic and medicinal herbs, resins, cork, ...) towards the revival of the mountain economy. Very often territorial marketing policies can be started in which the forest product becomes the genius loci to systematize different activities for the local territorial holding and can lead to positive social and economic repercussions. In fact, alongside these supply chains, educational and training, recreational, sporting, cultural, therapeutic, and social inclusion activities can be developed at the same time, which in some cases can renew the disused building heritage (2018). Trees are grown for food and occupy a central place in the relentless production of landscape.

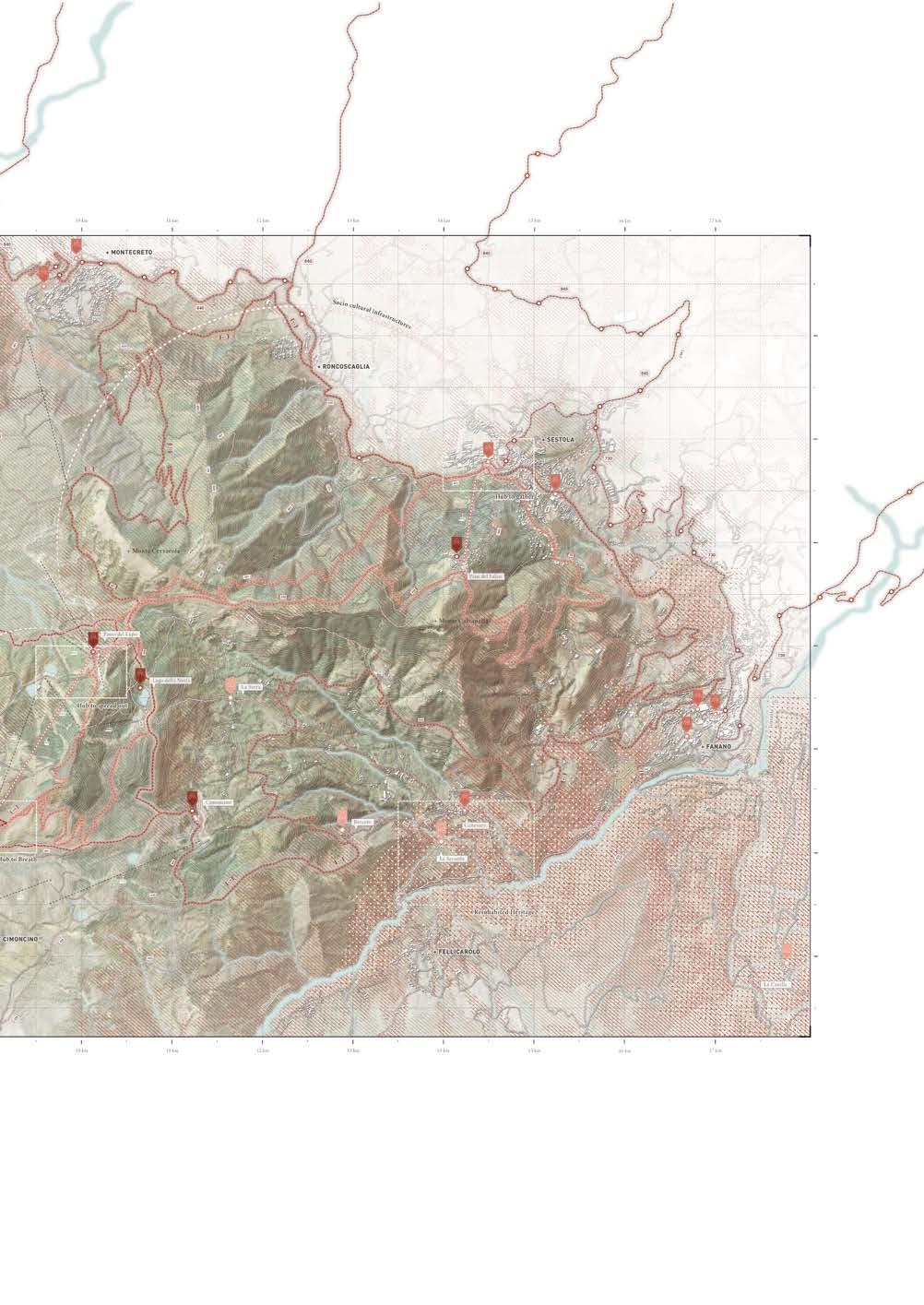

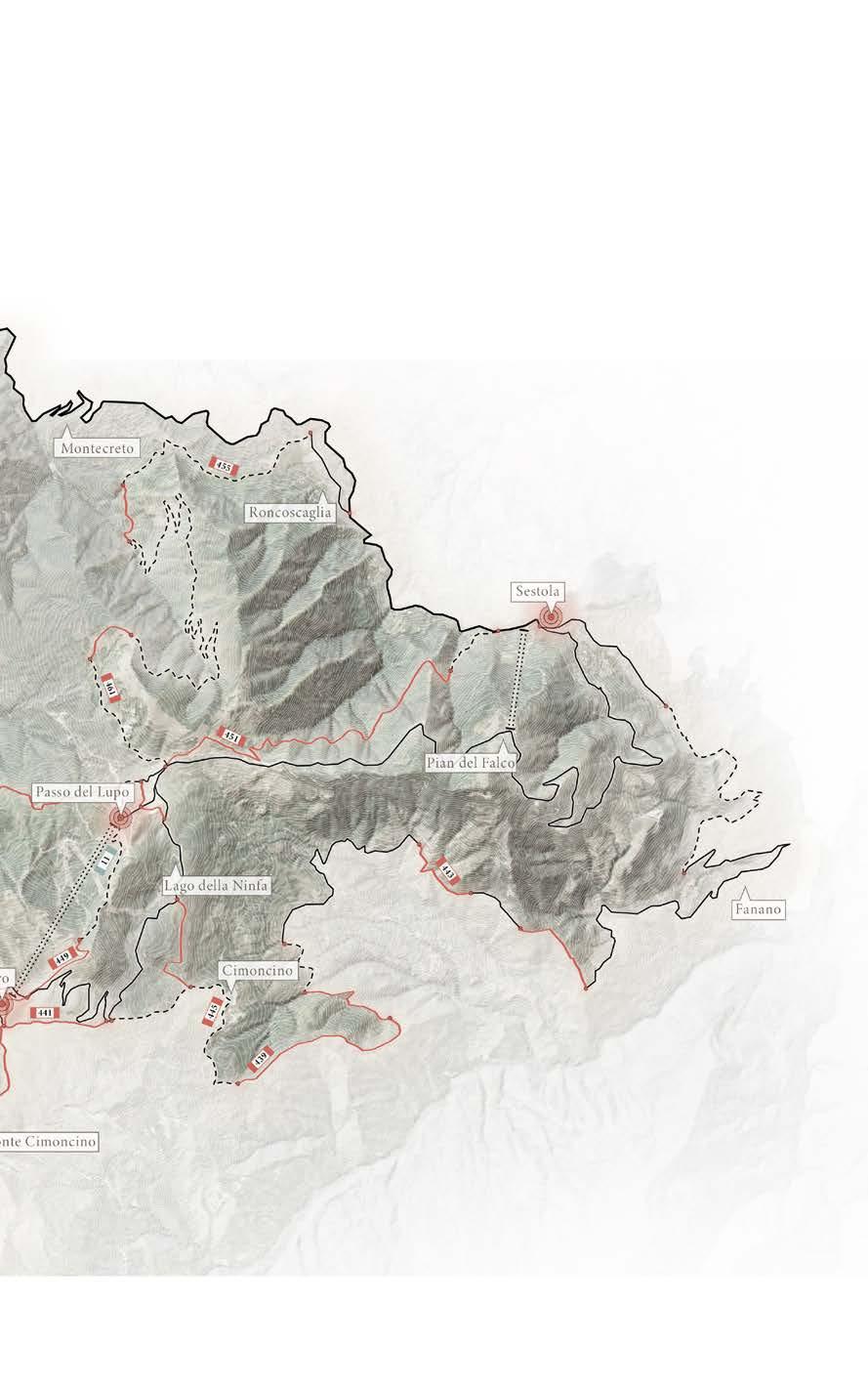

Alongside the forestry issue, the Emilia-Romagna Apennines are home to numerous abandoned villages, a heritage that, if not reconsidered, will fall into disrepair over the next few decades. For an abandoned country, however, there is another that is being reborn, both thanks to second homes and to regional initiatives such as the numerous Mountain Calls in which it’s possible to encourage the repopulation and revitalization of mountain areas through the concession of monetary resources to individuals, for the purchase of a home to be used as a first home. It is a widespread belief that a reactivated attention to the forest and built heritage, together with

Le foreste sono un’importante risorsa che si vuole proteggere, ma che va gestita, altrimenti i risultati sono quelli che osservabili oggi giorni: foreste in grado di produrre sempre meno beni materiali e servizi ambientali, esposte al rischio di invecchiamento e degrado.

Seguendo le direttive nazionali in materia di gestione dei territori forestali, essi dovrebbero essere a carico delle regioni tramite la redazione di appositi piani di gestione. Al momento attuale però una parte molto significativa dei boschi pubblici non è gestita dai piani vigenti, molto proprietà sono sottoutilizzate o abbandonate e nelle agende pubbliche la foresta non riveste carattere di priorità. Seguendo il ragionamento di Davide Pattanella in “Riabitare l’Italia”, in questo contesto il settore privato potrebbe avere un ruolo fondamentale per lo sviluppo di iniziative di valorizzazione delle filiere locali del legname e di prodotti forestali spontanei (funghi, tartufi, castagne, pinoli, erbe aromatiche e medicinali, resine, sughero, ...) verso il rilancio dell’economia montana. Molto spesso si possono avviare politiche di marketing territoriale in cui il prodotto forestale diventa il Genius loci per mettere a sistema diverse attività per la tenuta territoriale locale e può condurre a positive ricadute sociali ed economiche. Infatti, accanto a queste filiere si possono contemporaneamente sviluppare attività educative e formative, ricreative, sportive, culturali, terapeutiche ed a inclusione sociale che in certi casi possono rinnovare il patrimonio edilizio in disuso (2018). Anche gli alberi coltivati a scopi alimentare occupano un posto centrale nella incessante produzione di paesaggio.

Accanto alla problematica forestale, l’Appennino emiliano romagnolo ospita numerosi borghi abbandonati, un patrimonio che se non riconsiderato cadrà in rovina nel giro dei prossimi decenni. Per un paese abbandonato però, ce ne è un altro che sta rinascendo, sia grazie alle seconde case sia ad iniziative regionali come i numerosi Bandi Montagna nei quali si vuole incentivare il ripopolamento e la rivitalizzazione delle aree montane attraverso la concessione di risorse monetarie a persone fisiche, per l’acquisto di un alloggio da destinare a prima casa.

35 Communities supporting Landscapes

the fundamental sphere of social participation, are a good omen for addressing the situation of the Italian interior areas, towards a territorial and community project capable of making the mountain a place of fruitful and lasting life.

È una credenza diffusa quella che una riattivata attenzione verso il patrimonio forestale e costruito, insieme alla fondamentale sfera della partecipazione sociale, siano di buon auspicio per affrontare la situazione delle aree interne italiane, verso un progetto di territorio e di comunità in grado di far tornare la montagna luogo di vita fecondo e duraturo.

36 Fragile Mountains

Fig 6. Metato along 443 CAI path, in the neighborhood of Fanano.

Ph Forghieri © 2022

References

Ciuffetti, A. (2019). Introduzione. Un viaggio nel tempo per un nuovo modello economico e sociale. In Appennino. Economie, culture e spazi sociali dal medioevo all’età contemporanea. (pp. 11-12, pag. 20). Carocci.

Ciuffetti, A. (2019). Conclusioni. Un grande avvenire dietro le spalle. In Appennino. Economie, culture e spazi sociali dal medioevo all’età contemporanea. (pp. 292-293). Carocci.

Emilia-Romagna Region (2022). Bando Montagna 2022. https://territorio.regione.emiliaromagna.it/politiche-abitative/contributi-casa/ bando-montagna-2022

Lanzani, A. Curci, F. (2018). Le Italie in contrazione, tra crisi e opportunità. In De Rossi, A. Riabitare l’Italia. Le aree interne tra abbandono e riconquiste. (pp. 87-89). Donzelli.

Lanzani, A. Zanfi, F. (2018). L’avvento dell’urbanizzazione diffusa: crescita accelerata e nuove fragilità. In De Rossi, A. Riabitare l’Italia. Le aree interne tra abbandono e riconquiste. (pp. 132-136). Progetti Donzelli.

Nigro, R. (2020). Civiltà Appennino: l’Italia in verticale tra identità e rappresentazione. Donzelli.

Pazzagli, R. (2021). Montagne ritrovate. In Un Paese di paesi. (pag. 18). ETS.

Pazzagli, R. (2021). Territorio bene comune. In Un Paese di paesi. (pag. 23, pag. 27). ETS.

Pazzagli, R. (2021). Italie agricole. In Un Paese di paesi. (pag. 52). ETS.

Pazzagli, R. (2021). Contro il mito della transumanza. In Un Paese di paesi. (pag. 77). ETS.

Pettenella, D. (2018). Boschi e green economy: un progetto necessario. In De Rossi, A. Riabitare l’Italia. Le aree interne tra abbandono e riconquiste. (pp. 478-482). Donzelli.

Tarpino, A. (2012). Spaesati: luoghi dell’Italia in abbandono tra memoria e futuro. Einaudi.

Teti, V. (2018). Il sentimento dei luoghi, tra nostalgia e futuro. In De Rossi, A. Riabitare l’Italia. Le aree interne tra abbandono e riconquiste. (pp. 191-192, pp. 197-198). Donzelli.

37 Communities supporting Landscapes

or Transition?

From an environmental, social, and economic point of view, incalculable damage has been caused to the territory due to the climate and environmental crisis. In recent years, the need to consider scenarios for the future of human settlement structure in western countries has become more pressing. More specifically, in a country like Italy, where the encounter between nature and man has produced over the centuries and millennia a beautiful but fragile landscape, resistant but sensitive to climatic and anthropogenic changes (Pazzagli, 2012) thus showing with the outbreak of the pandemic, the impression of a collapsed territory.

The scientific world’s views on the habitability of territories are torn between two drastic scenarios with different but valid perspectives; scenarios that in turn allow identifying the multiple possibilities implicit in the evolution of social change.

In the first instance, a scenario is proposed in which cities will no longer be viable and habitable, the urban centers with fewer possibilities of adaptation would have fewer possibilities of

Da un punto di vista ambientale, sociale ed economico, la crisi climatica e ambientale ha causato e continuerà a provocare danni incalcolabili al territorio. Negli ultimi anni è diventata più pressante la necessità di considerare nuovi scenari per il futuro degli insediamenti umani dei paesi occidentali. Più precisamente, in un Paese come l’Italia, in cui l’incontro tra uomo e natura ha prodotto nel corso dei secoli e dei millenni un paesaggio bello ma fragile, resistente ma sensibile ai cambiamenti antropici e climatici (Pazzagli, 2012), lo scoppio della pandemia ha ulteriormente dimostrato le sue numerose fragilità, oggi si ha l’impressione dell’Italia come di un territorio in collasso.

L’opinione del mondo scientifico circa l’abitabilità dei territori è combattuta tra due drastici scenari aventi prospettive diverse, ma entrambe valide per il futuro dei territori. Questi scenari consentono di individuare le molteplici e implicite possibilità che il cambiamento sociale è in grado di guidare e far evolvere.

In primo luogo, si propone uno scenario in cui le città non saranno più percorribili ed abitabili, in

39 Communities supporting Landscapes

Mountain

of

change. It En { * } 1. 02

resilience in the face

climate

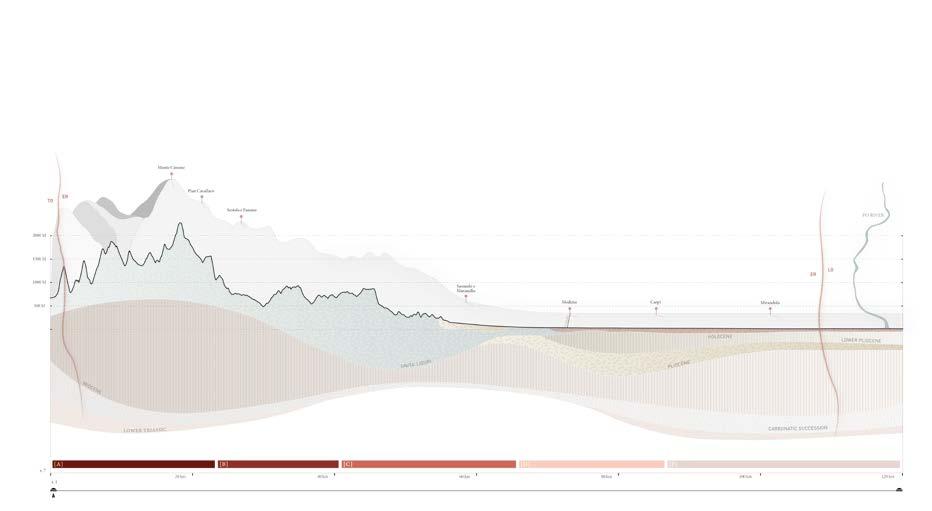

CLIMATE CHANGE IN MOUNTAIN TERRITORIES Decay

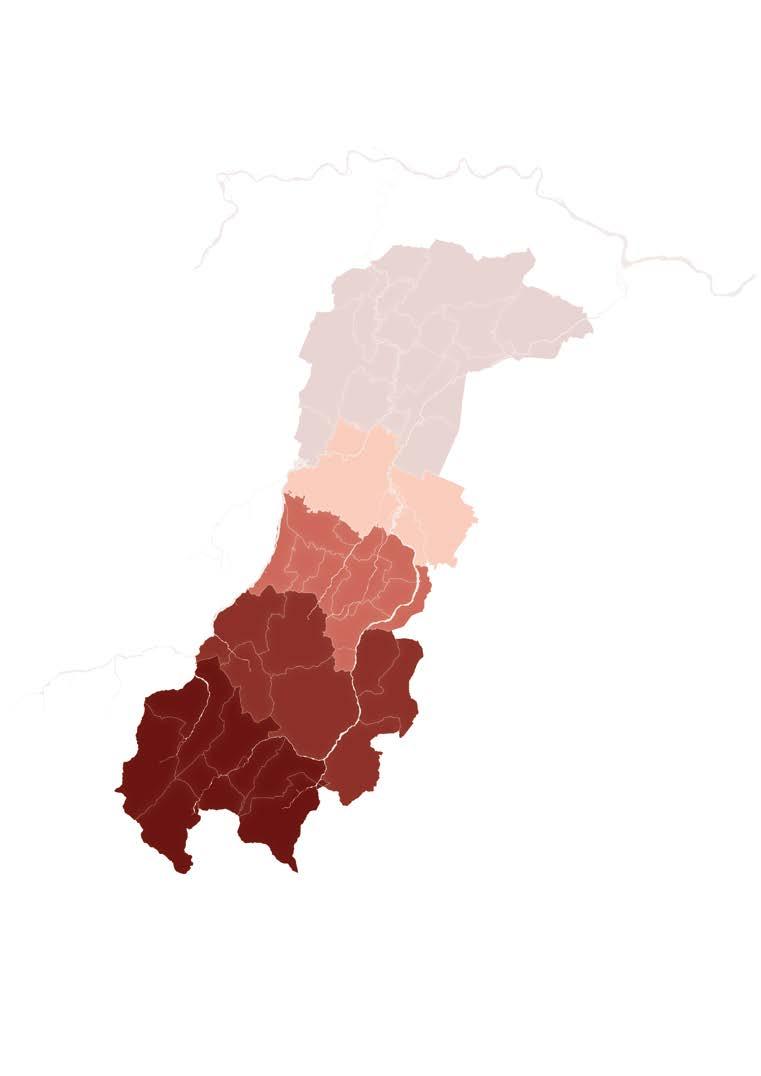

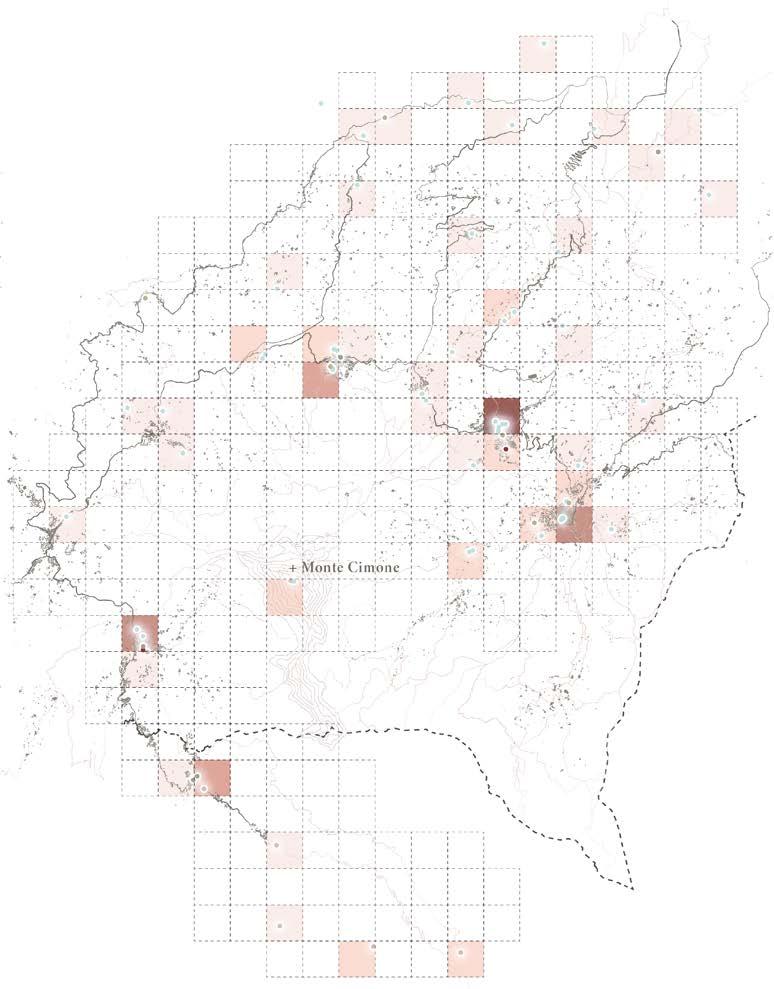

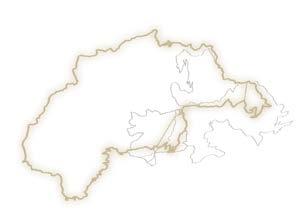

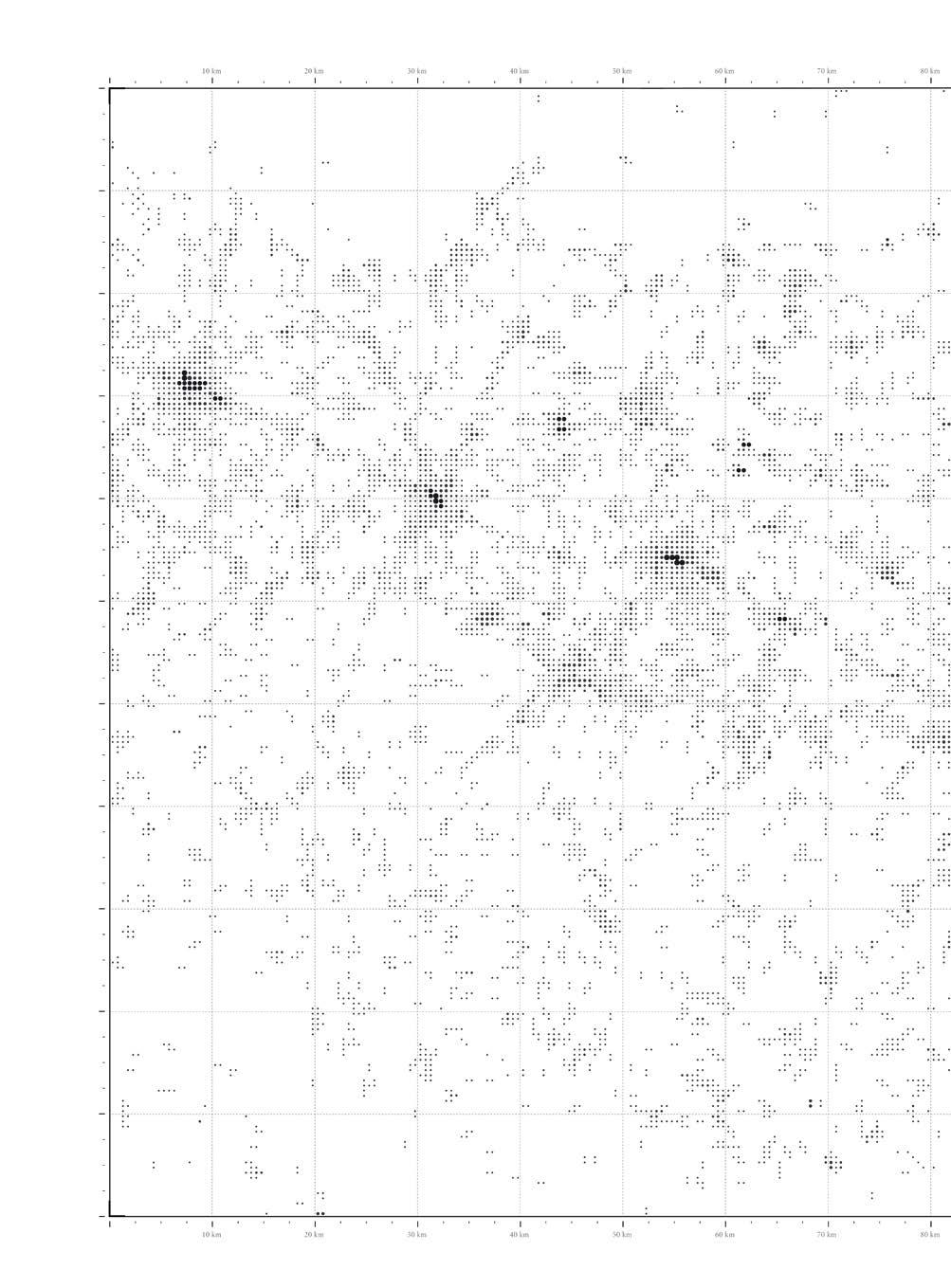

40 Fragile Mountains 0 km 50 km 100 km LEGEND - 0.0900 - 0.2920 0.2920 - 0.4180 0.4180 - 0.5700 0.5700 - 0.7360 0.7360 - 1.5000

Fig 7. Climate change adaptation capacity in Northern Italian provinces.

attracting population than in the past (Carrosio, 2021). In fact, some current situations experienced in extremely hot summer periods show that cities do not have the capacity to withstand large heat waves and that, in addition, due to their productivity and housing demand, there is an increase in atmospheric pollution and CO2 emissions. In this scenario, the population of urban centers would have to leave the cities to move to less urbanized areas but with the guarantee of living in an environment suitable for their daily lives.

On the other hand, a second vision places the city in a new and flourishing phase of modernization (Carrosio, 2021). Proposing a narrative that gives strength to the redemption of the currently well-known model of urban occupation. As Roberto Cingolani, Minister for Ecological Transition explains, “With more than half of the world’s population now living in cities, urban agglomerations are key drivers for a sustainable, peaceful, and prosperous climate future.”

It raises an important discussion in both scenarios in which it is understood that for the future of the habitability of the territory, the key is not in the cities or in the rural themselves, but in the urbanization for the fight against climate change.

However, there is a third scenario that contemplates a more global vision of the territory focusing on the potential for resilience, adaptation, and mitigation. Taking into account the relationships and coevolution between human settlements and the environment and even in that sense, between the urban and mountain areas. This vision postulates the existence of necessary interdependencies between cities and internal spaces, as a function of an ecological transition that is concretized in the recomposition of the fractures between ecological systems and social systems (Carrosio, 2021).

Mountain environments, which could also be described as Inlands on the northern side of the Italian geography, are territories endowed with a series of natural and cultural resources as the potential for the reconstruction of the identity of

questo senso i centri urbani con minori possibilità di adattamento avrebbero minori possibilità di attrarre la popolazione rispetto al passato (Carrosio, 2021). Infatti, alcune situazioni attuali, testimoni di periodi estivi estremamente caldi, mostrano come le città non abbiano la capacità di resistere a grandi ondate di calore e che, a causa della loro elevata produttività e domanda abitativa, si siano registrati aumenti dell’inquinamento atmosferico e delle emissioni di CO2. In questo primo scenario, la popolazione dei centri urbani dovrebbe lasciare le città per trasferirsi in aree meno urbanizzate, con la garanzia di vivere in un ambiente più salubre e adatto alla propria quotidianità.

Una seconda visione, invece, pone la città in una nuova e fiorente fase di modernizzazione (Carrosio, 2021). Essa propone una narrazione che da forza al riscatto del modello di occupazione urbana attualmente noto. Come spiega Roberto Cingolani, ministro per la Transizione ecologica, “con più della metà della popolazione mondiale che ora vive nelle città, gli agglomerati urbani sono fattori chiave per un futuro climatico sostenibile, pacifico e prospero”.

Entrambi gli scenari sollevano dibattiti rilevanti, si comprende che la chiave per l’abitabilità futura del territorio non risiede né nelle città né nelle campagne, ma in un’urbanizzazione capace di combatte e di adattarsi ai cambiamenti climatici.

Tuttavia, esiste un terzo scenario che contempla una visione più globale del territorio, esso è incentrata sul potenziale attivo della resilienza, dell’adattamento e della mitigazione. Si tengono conto i rapporti e le relazioni tra gli insediamenti umani e l’ambiente circostante e, in tal senso, tra le aree urbana e i territori montani. Questa visione assume l’esistenza di necessarie interdipendenze tra la città e le aree interne, in funzione di una transizione ecologica capace di concretizzarsi nella ricomposizione delle fratture tra i sistemi ecologici e i sistemi sociali (Carrosio, 2021).

Gli ambienti montani appenninici, che si potrebbero definire come l’Entroterra della penisola italiana, sono territori dotati di numerose risorse naturali e culturali: per esempio, la grande

41 Communities supporting Landscapes

a place in abandonment, which, if activated, allow great possibilities of adaptation and response to crises, turning them into opportunities. This resilient capacity is derived from the interaction between local systems of natural, economic, and cultural capital as key facts of intentional adaptative action and potential for adaptation.

potenzialità di ricostruire l’identità dei luoghi in abbandono che, se riattivati, permetterebbero lo sviluppo di numerose opportunità verso nuove capacità di adattamento. Questa possibilità di resilienza delle popolazioni e dei territori deriva dall’interazione tra i sistemi locali: il capitale naturale, economico e culturale sono elementi fondamentali sia per sviluppare l’intenzionalità di adattamento che l’attivazione del suo potenziale.

42 Fragile Mountains

Fig 8. People waiting the chair lift, Passo del Lupo.

Mountain environments are territories full of contrasts, made up of highly complex and fragile contexts that are currently facing global challenges due to climate change, which could bring with it strong environmental impacts on many socioeconomic sectors and natural systems. But at the same time, mountain environments over the time have shown the ability to make flexible use of their resources in response to economic trends and crises (Ferrario and Marzo, 2020).

With the transformation and drastic expansion of urban regions worldwide, metro rural areas also have changed dramatically. First of all, after mechanization and industrialization, rural areas and small towns in mountain environments experienced mass out-migration of people. On the other hand, being a recreational landscape temporarily receives massive immigration of guests (Carlow, 2016) as a tourist destination in accordance with the needs of people living in more urban areas.

For a long time, mountains were isolated and inaccessible territories, representing landscapes of fascination but at the same time perceived as unpredictable and dangerous places. The mysterious image of the mountains changed when 200 years ago, poets, painters, and philosophers discovered mountain as a place for destination characterized by an exuberant natural landscape.

As well summarized and expressed by the World Tourism Organization (2018). The “Belle Epoque“ of mountain tourism came to halt during the 20th century’s two world wars and the great depression, which saw the disappearance of the wealthy leisure class. Consequently, mountain tourism fell into a deep structural crisis that lasted well into the 1950s. However, the advent of paid vacation time and individual motorization led to an unexpected renaissance of Alpine tourism in the 1960s, which brought with a series of innovations in the field of mountain leisure sports and accommodation.

Gli ambienti montani sono territori ricchi di contrasti, costituiti da contesti altamente complessi e fragili che attualmente si trovano ad affrontare le sfide globali dovute dai cambiamenti climatici, processi che potrebbero portare forti impatti ambientali su molti settori socioeconomici e sui sistemi naturali. Allo stesso tempo, storicamente, gli ambienti montani hanno dimostrato di essere in grado di attuare un uso flessibile delle proprie risorse in risposta agli andamenti e alle crisi economiche (Ferrario e Marzo, 2020).

Con la trasformazione e la drastica espansione delle regioni urbane di tutto il mondo, anche le aree rurali metropolitane sono cambiate radicalmente. Innanzitutto, dopo la meccanizzazione e l’industrializzazione, le aree rurali e le piccole città situate in ambienti montani hanno subito un’emigrazione di massa. D’altra parte, costituire un paesaggio ricreativo ha temporaneamente permesso una massiccia immigrazione di visitatori (Carlow, 2016) che hanno scelto la montagna come destinazione turistica capace di rispondere ai bisogni delle persone che vivono in aree urbane.

Per molto tempo le montagne sono state territori isolati e inaccessibili, hanno rappresentato paesaggi affascinanti, ma allo stesso tempo sono state percepite come luoghi imprevedibili e pericolosi. L’immagine misteriosa della montagna è cambiata quando 200 anni fa poeti, pittori e filosofi hanno scoperto la montagna come luogo di destinazione perché caratterizzato da un paesaggio naturale esuberante.

Il riassunto di questa secolare storia è stato espresso dall’Organizzazione Mondiale del Turismo (2018). La “Belle Époque” del turismo di montagna si è interrotta durante le due guerre mondiali del XX secolo e la grande depressione, che ha visto la scomparsa della classe più agiata. Di conseguenza, il turismo di montagna è caduto

43 Communities supporting Landscapes

It

En

Tourism winter sport decline and community impacts.

44 Fragile Mountains

Fig 9. People enjoying the beautiful winter day, Passo del Lupo.

Fig 10. Trash at the end of the ski day, Passo del Lupo.

Downhill skiing became the key to a lucrative new economy.

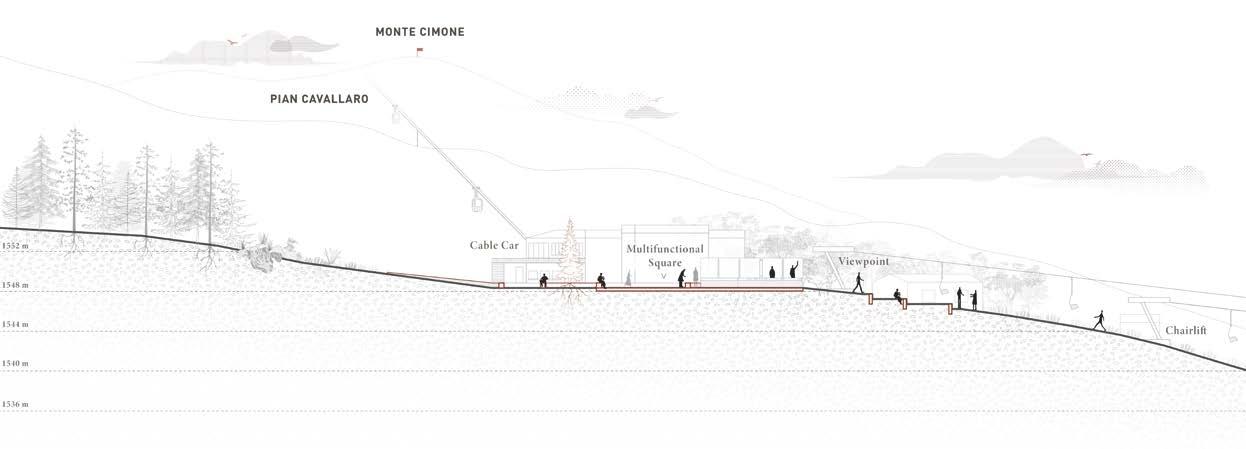

The “renaissance” implied the construction of a series of infrastructures that allowed a more direct connection with the main urban settlements, the use of the car became the main means of transportation in the mountains, as well as a series of different types of accommodation for the wealthy. Skiing areas became one of the most lucrative forms of tourism and a place to invest in new technologies such as cable cars and chairlifts.

This lucrative tourism model, specially developed in the Alps as the largest mountain chain on the European continent, began to be the object of reference for other mountains ranges in search of a lucrative model that would allow them to attract investors and save their local economy from abandonment, as in the case of Apennines becoming over the years, in more democratized and accessible spaces for the enjoyment of the surrounding communities, families and common people.

Mountain destinations are heavily affected by their ecosystems. Any changes in climate can have a profound effect on tourism demand. A lack of snow, for example, might require significant investment to fix. (World Tourism Organization, 2018). While the ski resort model was the economic mainstay of many mountains over the years, with the current problems and crises facing the world, this model is becoming increasingly obsolete, and mountains are now looking for new ways to experience their precious landscape and a new habitability that will help protect and safeguard it for future generations.

in una profonda crisi strutturale che si è protratta fino agli anni Cinquanta. Tuttavia, l’avvento delle ferie pagate e della motorizzazione individuale ha portato negli anni Sessanta ad un’inaspettata rinascita del turismo alpino, che ha portato con una serie di innovazioni nel campo degli sport e delle strutture ricettive per il tempo libero in montagna. Lo sci alpino è diventato la chiave per una nuova e redditizia economia.

Il “rinascimento” comportò la realizzazione di una serie di infrastrutture che consentissero un collegamento più diretto con i principali insediamenti urbani, l’uso dell’auto divenne il principale mezzo di trasporto in montagna, oltre ad una serie di diverse tipologie abitative come alloggio per le classi più benestanti. I comprensori sciistici sono diventati una delle forme più redditizie di turismo e luoghi in cui investire in nuove tecnologie, come funivie e seggiovie.

Questo modello turistico redditivo si è sviluppato primariamente nella catena alpina, la più grande catena montuosa del continente europeo. Le Alpi iniziarono ad essere l’oggetto di riferimento per altre catene montuose minori che ricercavano un modello redditizio che consentisse loro di attrarre investitori e salvare la loro economia locale dall’abbandono. È questo il caso dell’Appennino, divenuto negli anni un luogo democratizzato e accessibile per le famiglie e la gente comune.

Le destinazioni montane sono pesantemente influenzate dai loro ecosistemi. Eventuali cambiamenti climatici possono avere un profondo effetto sulla domanda turistica. La mancanza di neve, ad esempio, potrebbe richiedere investimenti significativi per una sua produzione artificiale (Organizzazione Mondiale del Turismo, 2018) Se il modello di comprensorio sciistico è stato negli ultimi anni il cardine economico di molte montagne, con i problemi e le crisi attuali del mondo, questo modello sta diventando sempre più obsoleto. La montagna sta oggi ricercando esperienze per il suo prezioso paesaggio e una nuova abitabilità che aiuterà a proteggere e salvaguardare questi paesaggi per le generazioni future.

45 Communities supporting Landscapes

Future perspectives for sustainable Mountains.

The need to supply the productive and economic demand in a global context, forces the exploitation of the territories in immeasurable ways in order to satisfy these demands, promoting the loss of a sense of place, and at the same time allowing the disconnection that man has had with the land he inhabits. Cities are the combination and the result of the simultaneous interaction between nature and artificial technology, and their ecological footprint expansion forces the extraction of natural resources from even further resources, with obvious environmental consequences (Tato, 2016).

The dynamics of acceleration and artificialization of the territory have contributed greatly to the ecological environmental crisis that the world is currently facing. Urban systems have become too globalized, able to respond to the needs of their cities through the activation of international value chains. These chains organize the transformation of nature into commodities on a planetary scale, disconnecting cities from neighboring territories. (Carrosio, 2021). These dynamics have contributed to the urbanization processes of the cities and to the neglect of the natural environments, leading to a disconnection between the urbanized areas and the natural resources of the mountains that have an interdependence between the two, leaving a fragile territory.

Recognizing this gap between mountain and urban areas also suggests that the relationship between them builds a geography of adaptability that only territories with these characteristics can offer. Mountain territories are in a privileged position to face climate change and embark on a path of radical ecological transition (Carrosio, 2021). Because of the capacity of urban centers as powerful investors in natural capital can cooperatively safeguard the renaissance of internal mountain areas.

Strengthening the relationship between the city and mountains opens the possibility to reflect on how to move towards a new model of circular

La necessità di soddisfare la domanda produttiva ed economica di scala globale, per soddisfare le richieste stesse l’economia costringe lo sfruttamento dei territori in modi incommensurabili, favorendo la perdita del senso del luogo, e allo stesso tempo, permettendo la disconnessione che le popolazioni hanno sviluppato con la terra che abitano. Le città sono la combinazione e il risultato dell’interazione simultanea tra natura e tecnologia, e la loro espansione costringe all’estrazione di risorse naturali che influenzano una maggiore impronta ecologica, con evidenti conseguenze ambientali e climatiche. (Tato, 2016).

Le dinamiche di accelerazione e di artificializzazione del territorio hanno notevolmente contribuito alla crisi ecologica ambientale che il mondo sta attualmente affrontando. I sistemi urbani sono diventati troppo globalizzati, in grado di rispondere ai bisogni delle loro città attraverso l’attivazione di catene economiche di scala internazionale. Queste catene organizzano la trasformazione della natura in prodotti mercificati a scala planetaria, questi processi disconnettono le città dalle identità dei territori limitrofi (Carrosio, 2021). Tali dinamiche hanno contribuito ai processi di urbanizzazione delle città e all’abbandono degli ambienti naturali, portando ad una disconnessione tra le aree urbanizzate e le risorse naturali delle montagne, ma data la profonda interdipendenza tra le due, fanno emergere la montagna come un territorio fragile.

Riconoscere il divario tra montagna e aree urbane suggerisce anche come il loro rapporto costruisca una geografia di adattabilità che solo territori con queste opposte caratteristiche possono offrire. I territori di montagna si trovano in una posizione privilegiata per affrontare i cambiamenti climatici e sono in grado di intraprendere un radicale percorso verso la transizione ecologica (Carrosio, 2021). A causa della capacità dei centri urbani di

46 Fragile Mountains

It

En

economy and above all towards new habitability perfectly attractive from a social, economic, and environmental point of view, thus generating more sustainable territories.

essere potenti investitori di capitale, essi possono al tempo stesso scegliere di salvaguardare la rinascita delle aree montane interne.

Rafforzare il rapporto tra città e montagna apre la possibilità di riflessione su come sviluppare un nuovo modello di economia circolare, verso una nuova abitabilità perfettamente appetibile dal punto di vista sociale, economico e ambientale, capace di generare territori più sostenibili.

References

Pazzagli, R. (2012). La cura del Luoghi. In Un paese di paesi (pp. 161-162). ETS.

Debarbieux B. (2016). Producing (common) Mountains. In Ferrario, V. Marzo M. (Ed.), La montagna che produce (pp. 39-52). Mimesis.

Carroiso, G. (2021). Metromontagna, cambiamento climatico e tranzisione ecologica. In Barbera F. De Rossi, A (Ed.), Metromontagna. Un progetto per riabitare l’Italia (pp. 153 - 170). Donzelli.

Carlow, V.M (Eds). (2016) The relevance of thinking the rural. In Ruralism: The future of small villas and towns in an urbanizing world. (pp. 6-9). Jovis.

WTO World Tourism Organization (2018). The long specialization process of mountain tourism. In Sustainable mountain tourism. Opportunities for local communities. (pp. 21-33). UNWTO.

Tato B. (2016). Networked urbanism. In Ruralism: The future of small villas and towns in an urbanizing world. (pp. 107-117). Jovis.

47 Communities supporting Landscapes

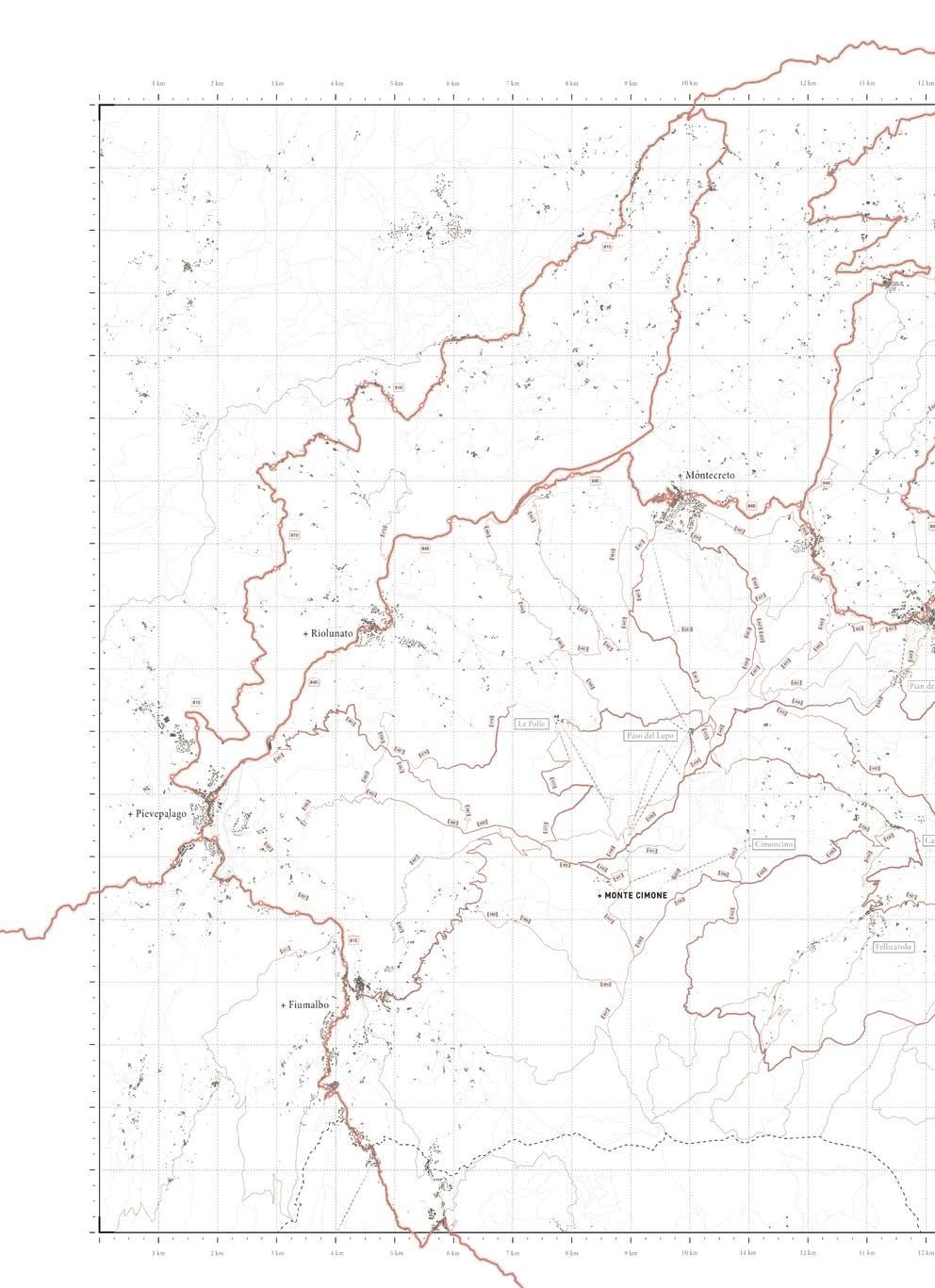

THE APENNINE LABORATORY Opportunities for contemporary society

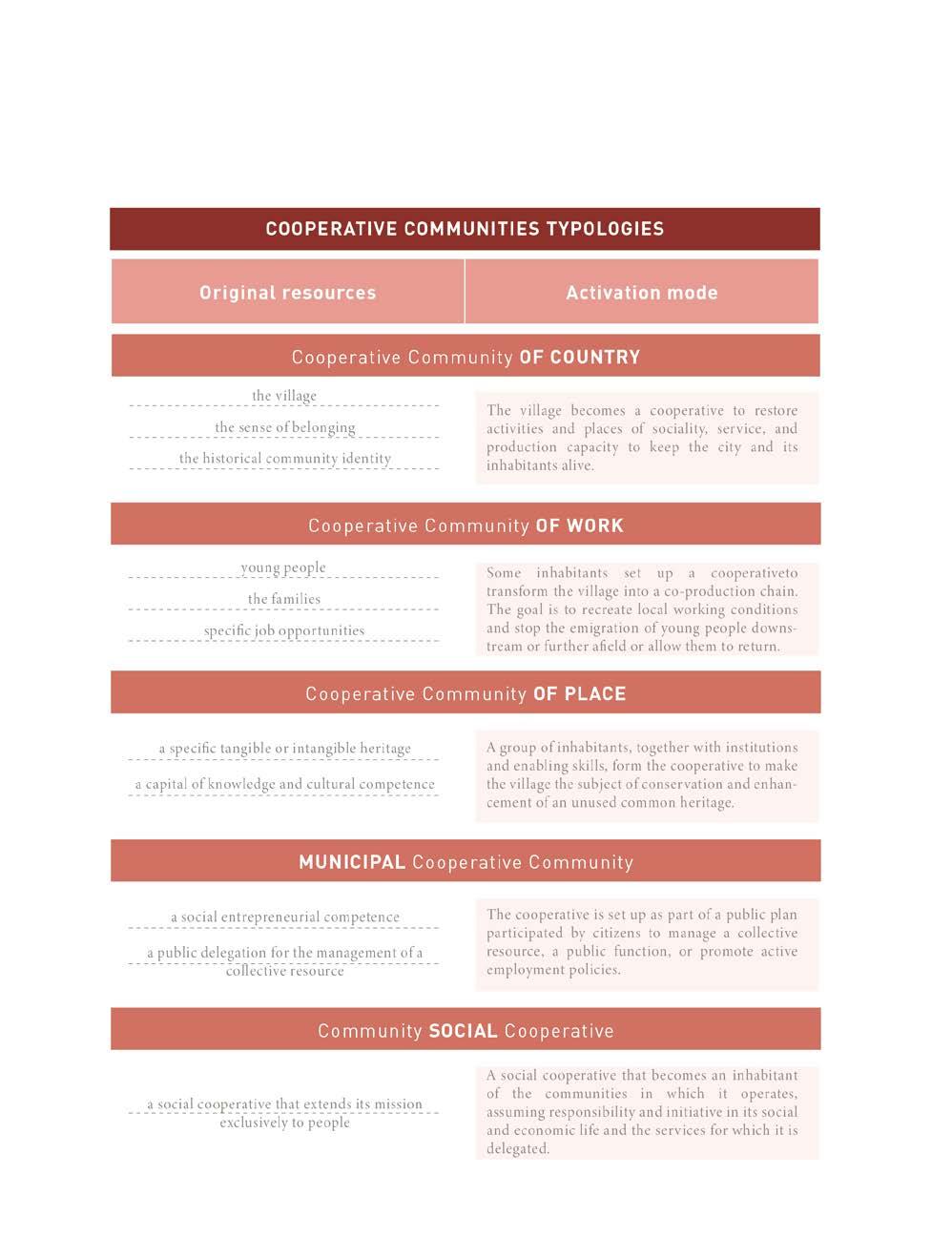

The inland areas of the Italian Apennines appear today as a set of spaces capable of offering new opportunities for growth and development to contemporary society. The centuries-old history of the Apennine territory testifies and demonstrates the multiple possibilities for the future of inland areas, places capable of assuming different and alternative roles with respect to the dominant economic model, capacity capable of assuming new forms and transforming themselves into a sort of laboratory in which new social realities can be experienced (Ciuffetti, 2019). Good practices with the power to positively influence the lifestyles of the inhabitants of these territories, experiences with a great propulsive capacity that will allow the extension of the same practices to other territories found in the same critical conditions. The good practices and new social realities that will develop will have to be based on the originality and diversity of the Apennine area, on the peculiar characteristics of each Borgo and village, leaving out the more homologating operations instead.

Le aree interne dell’Appennino italiano appaiono oggi come un insieme di spazi capaci di offrire nuove opportunità di crescita e di sviluppo alla società contemporanea. La storia plurisecolare del territorio appenninico testimonia e dimostra le molteplici possibilità per il futuro delle aree interne, luoghi capaci di assumere ruoli diversi e alternativi rispetto al modello economico dominante, capacità in grado di assumere forme nuove e di trasformarsi in una sorta di laboratorio in cui si possano sperimentare nuove realtà sociali (Ciuffetti, 2019). Buone pratiche aventi il potere di influenzare positivamente gli stili di vita delle donne e degli uomini che abitano questi territori, esperienze con una grande capacità propulsiva che permetterà l’estensione delle stesse pratiche verso altri territori ritrovatosi nelle stesse condizioni di criticità. Le buone pratiche e le nuove realtà sociali che si svilupperanno dovranno basarsi sull’originalità e sulla diversità dell’area appenninica, sulle caratteristiche peculiari di ogni borgo e villaggio, tralasciando invece le operazioni più omologanti.

49 Communities supporting Landscapes

It En { * } 1. 03

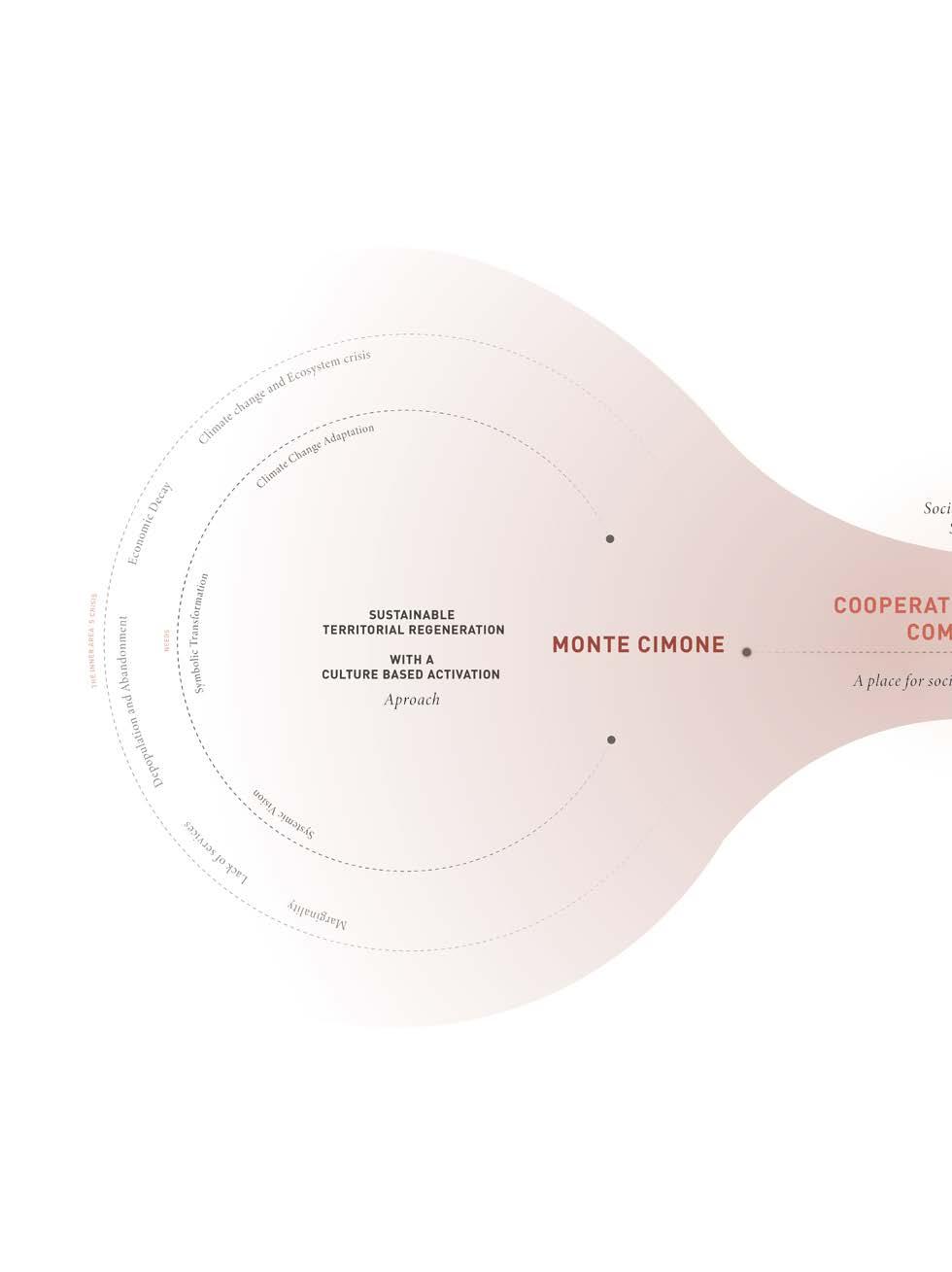

Territorial regeneration with culturebased activation approach.

It is not only history that witnesses the many possibilities of the future for the internal areas of the peninsula, but these landscapes are also spectators of numerous bottom-up projects that are being born and growing in the Italian mountains, initiatives that act as engines of physical regeneration and re-appropriation of places, starting from a matrix of cultural and social innovation. These projects contribute to affirming new ways of transforming territories, and practices that place a cultural-based regeneration at the center of their action, which is not limited to formulating a list of questions and needs, but projects that actively and responsibly become part of the solution. The entire process sees people, their sociability, and their needs as protagonists, not focusing on the mere recovery of the property.

In this context, culture represents the key, the essential factor for generating new perspectives and opportunities. Looking at the Apennine areas as an incessant laboratory of experiences for the construction of a different future allows to give new identities to the countries and transform them into symbolic places. Accessibility and attractiveness to different audiences must be guaranteed, new economies capable of providing the right range of services must be generated, and it is important to promote cohesion by triggering processes of social activation (Franceschinelli, 2018). All these entities focus on the local community and the importance of a co-creation and co-design capable of fulfilling the change necessary to give strength and liveliness to the Italian interior areas again.

As Ezio Micelli points out in “Arcipelago Italia: projects for the future of the country’s internal territories” (2018): in the strategy for the regeneration of internal areas and marginal places, culture must be the protagonist of the design significance and of the transformations that this will produce on the territory, and no longer a culture considered as subordinate to space. Culture is the foundation both for a radical redesign of places and for becoming the engine to trigger economic and urban development. This is not intended to support generic practices of association and participation, but rather to recognize energies for the lasting development of

Non è solo la storia ad essere testimone delle tante possibilità di futuro per le aree interne della penisola, siamo oggi spettatori di numerose progettualità dal basso che stanno nascendo e crescendo nelle montagne italiane, iniziative che agiscono come motori di rigenerazione fisica e di riappropriazione dei luoghi, partendo da una matrice di innovazione culturale e sociale. Questi progetti contribuiscono ad affermare nuove modalità di trasformazione dei territori, pratiche che pongono al centro della loro azione una rigenerazione a base culturale, che non si limitano a formulare un elenco di domande e necessità, ma progetti che diventano attivamente e responsabilmente parte della soluzione. L’interno processo vede come protagoniste le persone, la loro socialità e le loro necessità, non soffermandosi sul mero recupero dell’immobile.

In questo orizzonte, la cultura rappresenta la chiave, il fattore essenziale per generare nuove prospettive ed opportunità. Guardare alle aree appenniniche come ad un incessante laboratorio di esperienze per la costruzione di un diverso futuro permette di conferire nuove identità ai paesi e trasformarli in luoghi simbolici. Si deve garantire l’accessibilità e l’attrattività a pubblici diversi, bisogna generare nuove economie capaci di fornire la giusta offerta di servizi, è importante favorire la coesione innescando processi di attivazione sociale (Franceschinelli, 2018). L’insieme di queste entità mette al centro la comunità locale e l’importanza di una co-creazione e co-progettazione in grado di adempiere al cambiamento necessario per conferire nuovamente forza e vivacità alle aree interne italiane.

Come sottolinea Ezio Micelli in “Arcipelago Italia: progetti per il futuro dei territori interni del Paese” (2018): nella strategia per la rigenerazione delle aree interne e dei luoghi marginali la cultura deve essere protagonista del significato progettuale e delle trasformazioni che questo produrrà sul territorio, e non più una cultura considerata come subordinata allo spazio. La cultura è il fondamento sia per una radicale risignificazione dei luoghi sia perché diventa il motore per innescare lo sviluppo economico e urbano. Con questo non si intende sostenere generiche pratiche di associazione e partecipazione, quanto di riconoscere energie

50 Fragile Mountains

communities today destined for marginalization. In these terms, regeneration must give new value to inland areas, in order to re-emerge a quality and a sense that these places seem to have lost today. The new social and economic relationships must contribute to the generation of a new identity and specificity that gives a new shape to these places.

per uno sviluppo durevole di comunità oggi destinate alla marginalità. In questi termini, la rigenerazione deve conferire nuovo valore alle aree interne, per far nuovamente emergere una qualità e un senso che questi luoghi sembrano aver oggi perduto. Le nuove relazioni sociali ed economiche devono concorrere alla generazione di una nuova identità e specificità che conferisca una nuova forma a questi luoghi.

The meaning of Metromontagna.

As previously described, over the twentieth century the Italian inland areas were the protagonists of a progressive process of marginalization, becoming a real migratory context in the years of the economic boom. The Apennine mountains were characterized by depopulation and abandonment phenomena that went parallel to the great development of the urban-centered development model, which invested its growth opportunities exclusively in the cities.

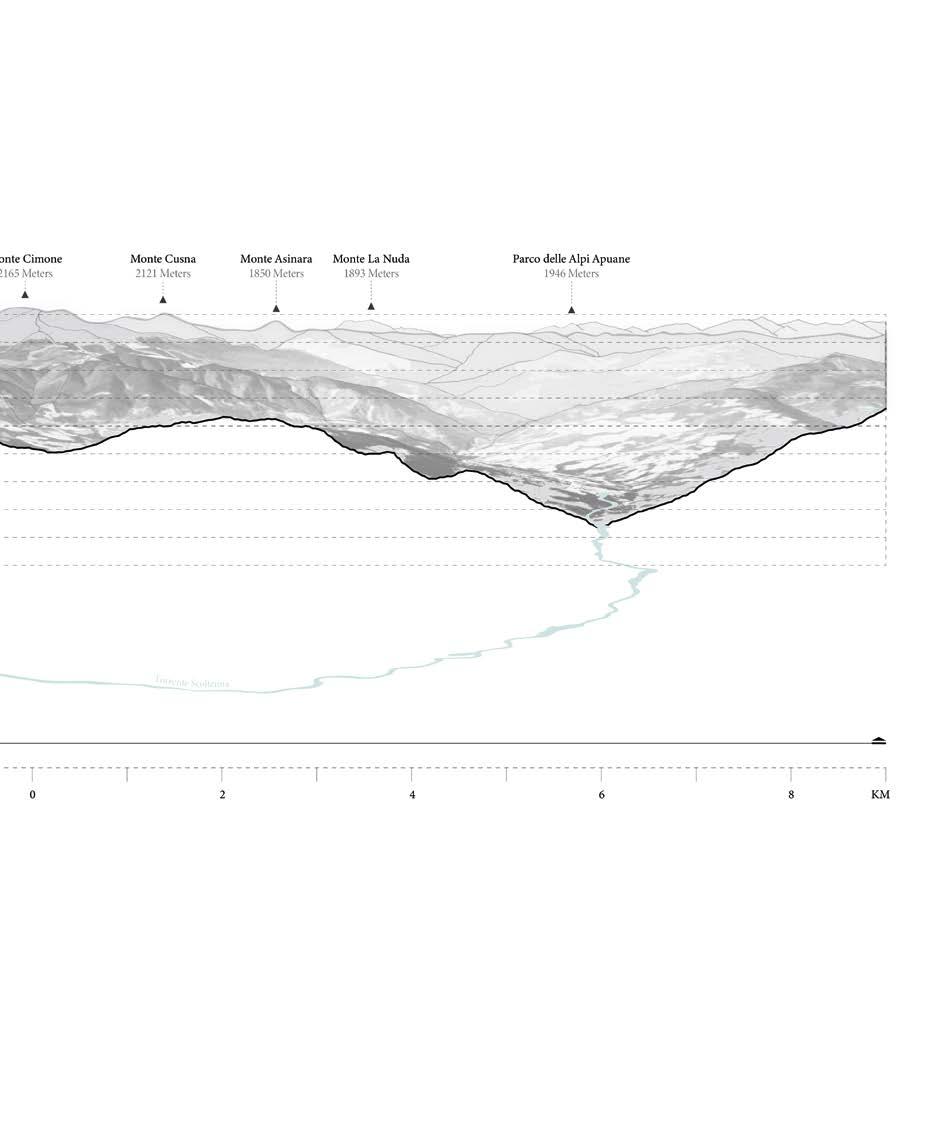

In the twentieth century, the intermediate territories, the centers of the valley floor and piedmont were perceived as the glue between the city and the mountain, the union element between those two territorial poles perceived as extreme and opposite. According to the definition coined by Giuseppe Dematteis, metromontagna is a term that relates two polarities that the contemporary age has conceived in increasingly separate and antithetical terms. (Varotto, 2021)

The value of the term metromontagna is based on the interdependence and cooperation of the different territorial systems. Its meaning allows relating the physical-material, environmental, economic, and infrastructural dimensions, allowing to observe the territorial dynamics in the section. The concept of metromontanità is the central node that can allow overcoming the

Come precedentemente descritto, nel corso del Novecento le aree interne italiane sono state protagoniste di un progressivo processo di marginalizzazione, diventando un vero e proprio contesto migratorio negli anni del boom economico. La montagna appenninica era caratterizzata da fenomeni di spopolamento e abbandono che andavano parallelamente al grande sviluppo del modello urbano centrico, il quale investiva le sue possibilità di crescita esclusivamente nelle città.

I territori intermedi, i centri di fondovalle e di pedemonte, nel XX secolo erano stati percepiti come il collante fra la città e la montagna, l’elemento di unione fra quei due poli territoriali percepiti come estremi e contrapposti. Secondo la definizione coniata da Giuseppe Dematteis, la metromontagna è un termine che mette in relazione due polarità che l’età contemporanea ha concepito in termini sempre più separati e antitetici. (Varotto, 2021)

Il valore del termine metromontagna si basa sull’interdipendenza e la cooperazione dei diversi sistemi territoriali. Il suo significato permette di mettere in relazione le dimensioni fisico-materiali, ambientali, economiche e infrastrutturali, permettendo di osservare le dinamiche territoriali in sezione. Il concetto della metromontanità è il nodo centrale che può permettere di superare lo

51 Communities supporting Landscapes

It

En

stalemate of the contrast between urban-centered and localistic visions. It is a matter of prefiguring an overall vision, based on a new settlement model, on a new way of re-inhabiting Italy (Barbera and De Rossi, 2021).

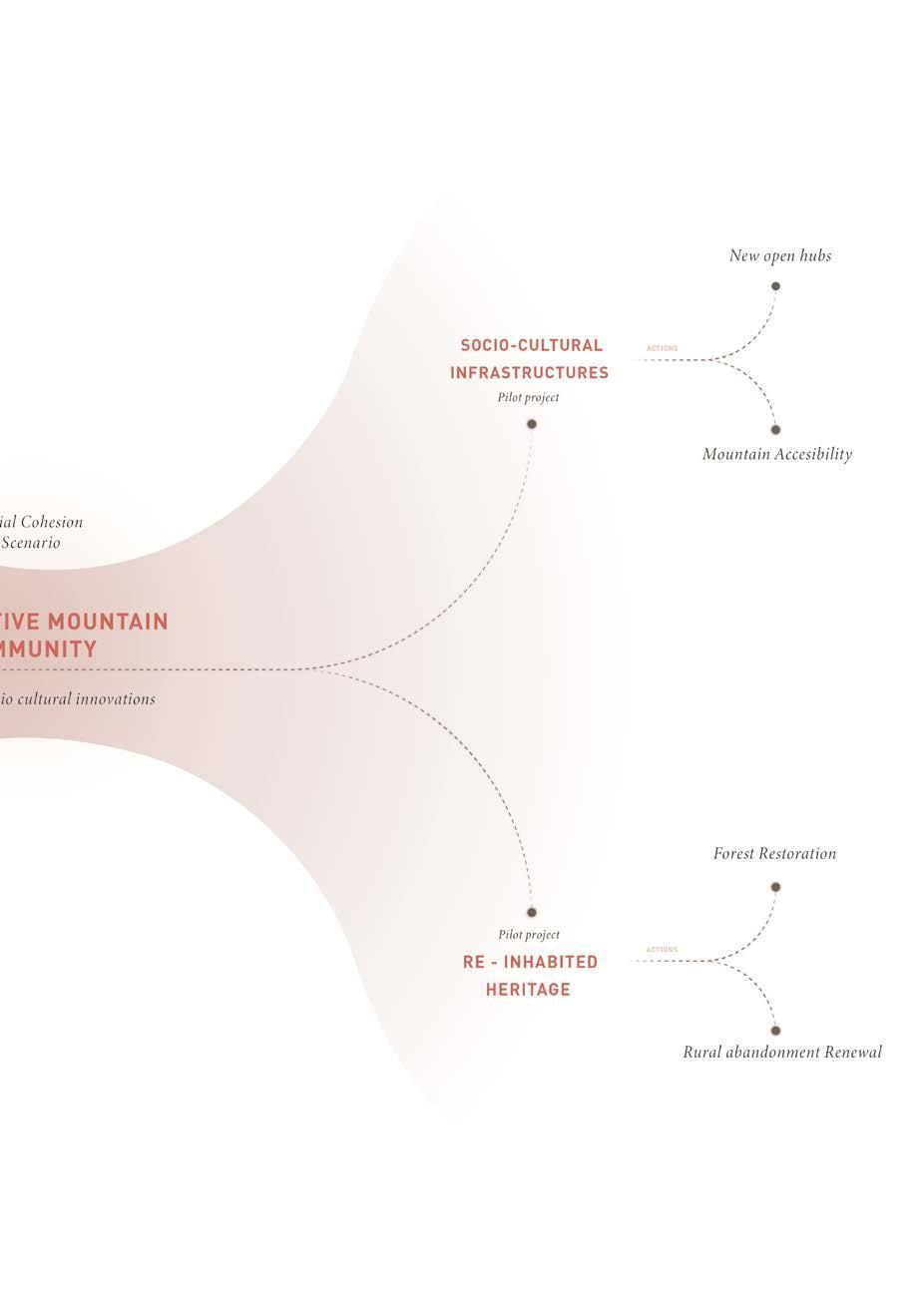

The metromontagna economy is based on production chains and infrastructures for accessing services, as well as their distribution in the territory. In this sense, the theme of infrastructures is expanded in an extensive and intensive sense, the infrastructures are no longer of a civil or logistic type but concern the material constitution of social citizenship and the environment (Barbera and De Rossi, 2012). This significance of social and green infrastructures presupposes a profound reconsideration of the issue itself, highlighting the importance of metromontagna welfare. The scale and spatial dimension of services play a decisive role, the value of welfare is in fact based on the ability to relate both on a local and a large scale. In today’s mountain and piedmont contexts, the infrastructure with priority importance is the digital one.

Territorial policies focused on the concept of the metromontagna have not yet been developed. However, there are innovations in national policies, local experiments, and intermediate institutions that can provide potential indications on the direction to go (Barbera and De Rossi, 2021). Following the literature analyzed, it is important to analyze the most relevant examples to date: firstly, the Strategia Nazionale per le Aree Interne (SNAI), then the Gruppi di azione locale (GAL), and finally the experiences of Community Cooperatives.

stallo della contrapposizione fra visioni urbano centriche e localistiche. Si tratta di prefigurare una visione complessiva, basata su un nuovo modello insediativo, su un nuovo modo di riabitare l’Italia (Barbera e De Rossi, 2021).

L’economia della metromontagna si basa sulle filiere produttive e sulle infrastrutture di accesso ai servizi, nonché alla loro distribuzione nel territorio. In questo senso il tema delle infrastrutture si amplia in senso estensivo e in senso intensivo, le infrastrutture non sono più di tipo civile o logistico, ma riguardano la costituzione materiale della cittadinanza sociale e l’ambiente (Barbera e De Rossi, 2012). Tale significazione delle infrastrutture sociali e verdi presuppone una profonda riconsiderazione del tema stesso, mettendo in luce l’importanza del welfare metromontano. La scalarità e la spazialità dei servizi gioca un ruolo decisivo, il valore del welfare si basa infatti sulla capacità di relazionarsi sia a scala locale sia a vasta area. Nei contesti odierni montani e pedemontani, l’infrastruttura con importanza prioritaria è quella digitale.

Politiche territoriali incentrate sul concetto della metromontagna ad oggi non sono ancora state sviluppate. Esistono però innovazioni di policies nazionali, esperimenti locali e istituzioni intermedie che possono fornire indicazioni potenziali sulla direzione da percorrere (Barbera e De Rossi, 2021). Seguendo la letteratura analizzata si vogliono analizzare gli esempi ad oggi più rilevanti: anzitutto la Strategia Nazionale per le Aree Interne (SNAI), poi i Gruppi di azione locale (GAL), e infine le esperienze delle Cooperative di Comunità.

52 Fragile Mountains

The experience of the Strategia Nazionale per le Aree Interne (Snai) constitutes a fundamental reference for addressing the issue of the interface between internal areas and policies. The SNAI, in the context of the policy placing itself in the 2014-020 area, represents a national economic and territorial development policy having as its objective the marginalization and the characteristic decline of the Italian inner areas.

The Strategy was born by combining a political vision with fine-grained statistical analyzes and new maps, which constitute the geography of social citizenship with reference to the distance from essential services (Barbera and De Rossi, 2021). In this way, the Strategy identifies seventy-two project areas and faces the design process by placing its own relevance through five important innovations.

First, the interventions are developed in favor of economic development and citizenship, providing for a reflection on services to the person and on how to organize their distribution and accessibility. Secondly, the chosen project areas are committed to developing an area strategy document, containing guiding ideas for directing change, towards the identification and creation of a driving cognitive chain. The third innovation consists in the choice of working exclusively with municipal associations, thus assuming in the figure of the Municipalities the public entity of reference for the implementation of the strategy. The fourth innovation lies in the attempt at territorial concentration, through the selection of a few areas the intervention is concentrated in each region. The effectiveness of the strategy depends on the ability to concentrate financial and human resources in areas where they combine high needs, and opportunities and the ability to seize them (Lucatelli and Tantillo, 2018). The fifth and last innovation materializes in the open working method, based on the involvement of different social actors in all phases of the design.

L’esperienza della Strategia Nazionale per le Aree Interne (Snai) costituisce un riferimento fondamentale per affrontare la questione dell’interfaccia fra le aree interne e le policies. La SNAI, ponendosi nell’ambito della politica economica 2014-2020, rappresenta una politica nazionale di sviluppo e coesione territoriale avente come obiettivo quello di contrastare la marginalizzazione e il declino demografico caratteristici delle aree interne italiane.

La Strategia nasce coniugando una visione politica con analisi statistiche di grana fine e nuove mappe, che costituiscono una geografia della cittadinanza sociale con riferimento alla distanza dai servizi essenziali (Barbera e De Rossi, 2021). In questo modo, la Strategia individua settantadue aree progetto e affronta il processo progettuali ponendo la propria rilevanza tramite cinque importanti novità.

In primis, gli interventi si sviluppano in favore dello sviluppo economico e della cittadinanza, prevedendo una riflessione sui servizi alla persona e su come organizzare la loro distribuzione e accessibilità. In secondo luogo, le aree progetto scelte sono impegnate ad elaborare un documento di strategia d’area, contenente idee-guida per indirizzare il cambiamento, verso l’individuazione e la creazione di una filiera cognitiva trainante. La terza innovazione consiste nella scelta di lavorare esclusivamente con associazioni di Comune, assumendo quindi nella figura dei Comuni il soggetto pubblico di riferimento per l’attuazione della strategia. La quarta innovazione risiede nel tentativo di concentrazione territoriale, tramite la selezione di poche aree viene concentrato l’intervento in ciascuna regione. L’efficacia della strategia dipende dalla capacità di concentrare risorse finanziarie e umane nelle aree dove i combinano elevati bisogni, opportunità e capacità di coglierle (Lucatelli e Tantillo, 2018). La quinta e ultima innovazione si materializza nel metodo di lavoro aperto, basato

53 Communities supporting Landscapes

It

En

SNAI and GAL, territorial development strategies.

The Strategy has opened a new phase of structural reflection of the marginal territories of internal Italy, it underlines the institutional and political, as well as cultural need for new governance systems and models that counteract the fragmentation and dispersion of metromontano welfare.

A second institutional architecture aimed at supporting and integrating growth strategies for inland areas consists of the Gruppi di Azione Locale (Gal), activated within the framework of the European Community led-local development (Clld) tool.

Through the Gal tool, it is possible to develop innovative political agendas for local development from a metromontana perspective. These Local Action Groups potentially represent the instrument that is most inspired by the tradition of local development with place-based procedures, structured on the needs of territories not established a priori, but the result of concertation between public and local actors, both entrepreneurial and expression of the third sector (Servillo and Fontana, 2021).

Unfortunately, despite their potential, these Groups remain disconnected from an integrated and innovative territorial vision, preferring more traditional development strategies. Up to now, in fact, most of the Gal have remained tied to a rural type of monothematic. Despite this, it is hoped that these Groups will soon be able to make the most of their peculiarity: that of being halfway between a public and a private institutional entity, that is projects capable of combining financial investments for the territory and communities capable of strengthening their strengths. entrepreneurial and social cohesion (Servillo and Fontana, 2021).

sul coinvolgimento di attori sociali diversi in tutte le fasi della progettazione.

La Strategia ha aperto una nuova fase di riflessione strutturale dei territori marginali dell’Italia interna, essa sottolinea la necessità istituzionale e politica, nonché culturale, di nuovi sistemi e modelli di governance che contrastino la frammentazione e la dispersione del welfare metromontano.

Una seconda architettura istituzionale volta a supportare ed integrare le strategie di crescita per le aree interne è costituita dai Gruppi di azione locale (Gal), attivati nell’ambito dello strumento europeo Community led-local development (Clld).

Tramite lo strumento dei Gal è possibile sviluppare delle agende politiche innovative per lo sviluppo locale in ottica metromontana. Questi Gruppi di azione locale rappresentano potenzialmente lo strumento che più si ispira alla tradizione dello sviluppo locale con procedure place-based, strutturate su esigenze di territori non costituiti a priori, ma frutto di una concertazione tra attori pubblici e locali, sia imprenditoriali sia espressione del terzo settore (Servillo e Fontana, 2021).

Purtroppo, nonostante il loro potenziali, questi Gruppi rimangono slegati da una visione territoriale integrata e innovativa, preferendo delle strategie di sviluppo più tradizionali. Fino ad oggi, infatti, la maggior parte dei Gal sono rimasti legati ad un monotematismo di tipo rurale. Nonostante questo, si spera che questi Gruppi possano prossimamente sfruttare al meglio la loro peculiarità: quella di porsi a metà fra un soggetto istituzionale pubblico e uno privato, cioè progetti in grado di coniugare investimenti finanziari per il territorio e comunità in grado di rafforzare le forze imprenditoriali e di coesione sociale (Servillo e Fontana, 2021).

54 Fragile Mountains

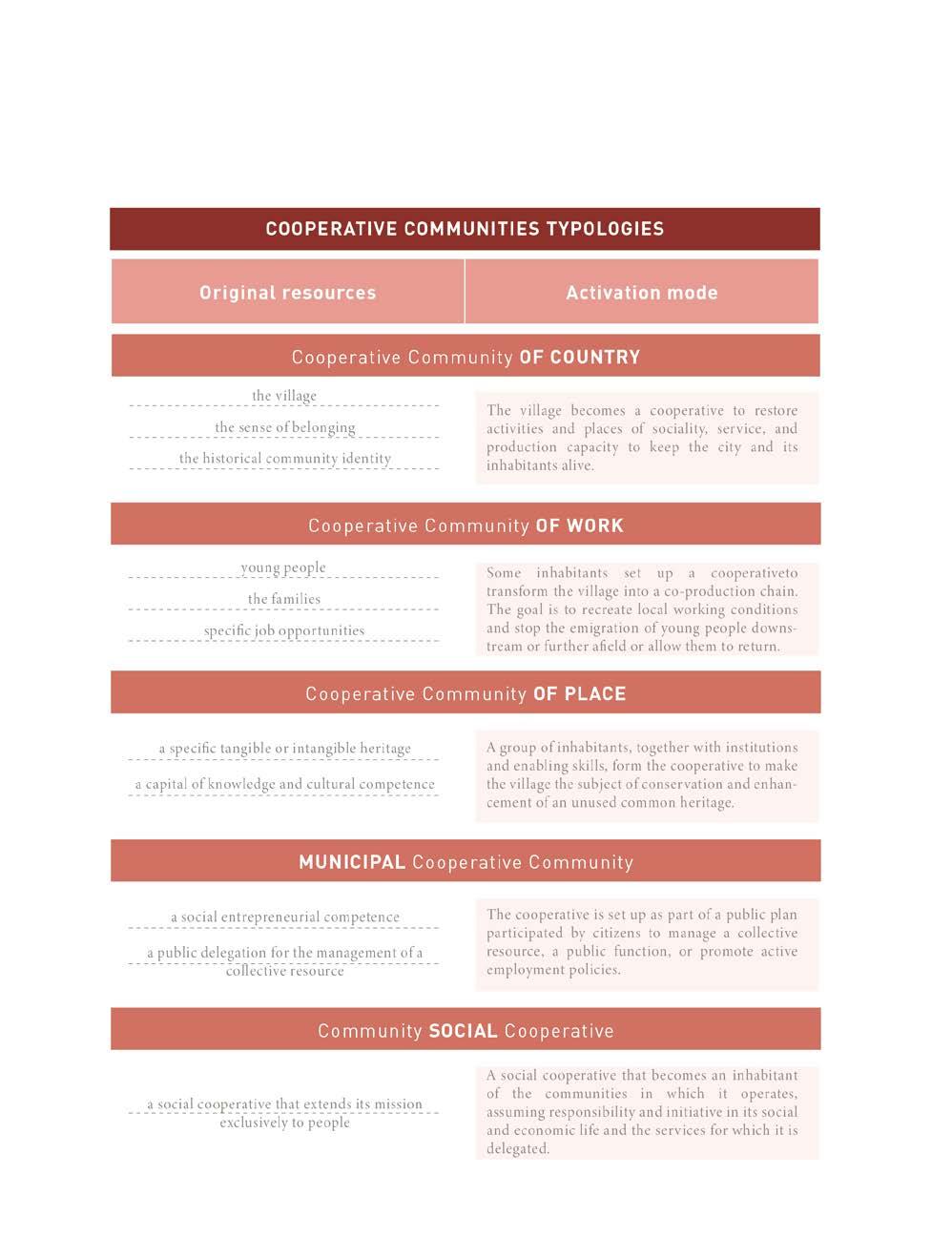

The Cooperative di Comunità represent a large research and experimentation laboratory from which to learn tools and methods for building economies and policies aimed at the development of inhabitants and communities in inland areas.