LEISURE WATER USES AS URBAN COMMONS A Play Element in Metropolitan Brussels

Matteo Lunetta

Author Matteo Lunetta (matteo.lunetta.95@gmail.com) Date January 2021 Academic Supervisors Prof. Dr. Burak Pak Drs. Hulya Ertas Studio Urban Commons International Master of Science in Architecture KU Leuven, Faculty of Architecture, Campus Sint-Lucas Brussels Paleizenstraat 65-67, 1030 Brussels

LEISURE WATER USES AS URBAN COMMONS A Play Element in Metropolitan Brussels

Matteo Lunetta

Acknowledgments I would like to address my special thanks To my supervisors, Burak Pak and Hulya Ertas, for their continuous support and dedication during this exceptional time. To Paul SteinbrĂźck from Pool Is Cool and Jean-Jacques Jungers for their insights and contributions. In remembrance of Doyel Vasudeo, who graduates together with us, through the work of her fellow students.

CONTENTS Introduction Introduction Abstract

9

10

Aims, Research Questions, Methods

11

I - Theoretical Framework Right to the city

14

Urban Commons

15

Leisure in the city

16

The concept of Play

18

Water uses in Brussels

22

II - Case Study: Van Eyck’s Playground Aldo Van Eyck’s playgrounds

32

Waterplay

40

Analysis

42

III - Water Interaction Water Interaction

46

Bellamy Play-Pond

52

Tainan Spring

54

Temporary Pools

58

Jardin Portuaire

62

Conclusion

66

IV - Urban Strategy Understanding the existing

70

Urban Strategy

84

V - Pacheco Centre The Site

90

Historical Context

Future of the Site

92

Short Movie

98

102

Project Intentions

124

Connecting

128

VI - Architectural Proposal

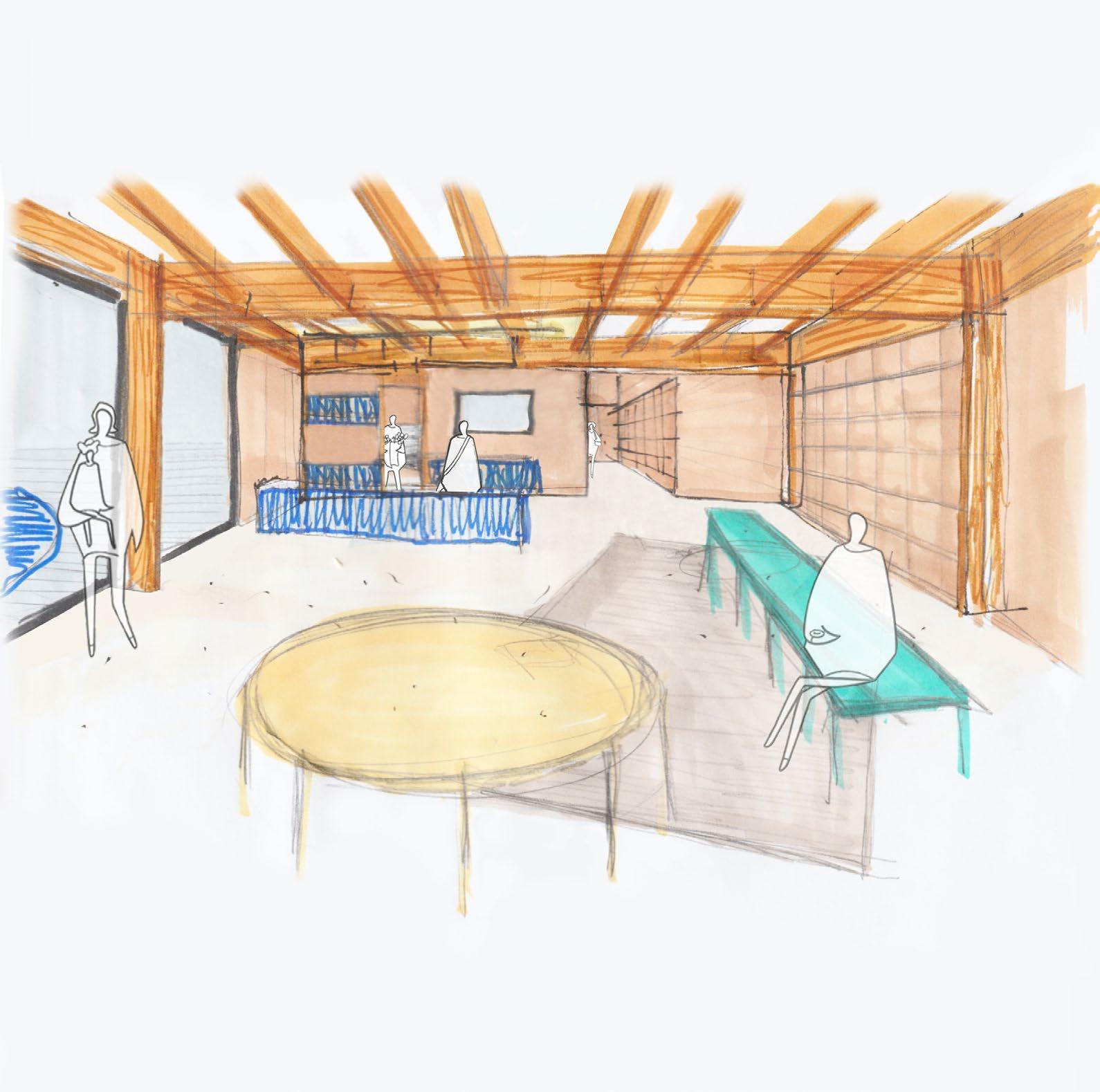

Commons as a Local Strategy

Program

130

134

Redefining a Common Square

A Space for Commoning Connection Staircase

Circular & Bio-Climatic Answer

148

154

Free Play Space

142

162 166

VII - Conclusion Conclusion

174

VIII - Appendix List of Figures Bibliography

182 184

INTRODUCTION This master dissertation was elaborated in the framework of the ‘Urban Commons’ studio directed by Prof. Dr. Burak Pak and Drs. Hulya Ertas. Their insights and our collective reflection lead me to investigate new ways to weave spaces in the city based on more collective actions. It also impelled me to reflect on the public-private dichotomy to suggest alternative ways to think the city with the prism of Urban Commons spaces. As a matter of information, the current reflexion was elaborate during the covid-19 international pandemic which did influence in positive and negative aspects the present research. This master thesis investigates the topics of Water and Play as transformative and socio-interactive tools in Brussels metropolitan area. Some additional motivations linked to the resilient and refreshing values of water, will also be tackled to improve the urban context of Brussels.

In the first part, theoretical concepts of Right to the city, Leisure, Play and Water Interactions will be put in place. Subsequently, The role those concepts might play in urban planning strategies is then analysed. In the second part, several examples of projects which shaped modern cities are explored. Those cases studies focus firstly on the Urban Play component of the theoretical framework. The second case study research addresses formal design proposals linked to human water linked-behaviours in the intention to clarfiy the notion of water interactions. In the third part, an urban strategy will be put in place. The proposal aims to suggest solutions to tackle an urban resolution to the lack of Water and Play spaces by critically mapping the metropolitan capital. In the fourth part, the site will be suggested and a contextual and historical analysis will be established. As a final and fifth part, based on the compiling of all the previous parts, an architectural proposal will be presented and will look at issues connected to potential tactics linked to Common Spaces, and the Water-Play connections.

Â| INTRODUCTION

9

ABSTRACT As a way to understand the connection Brussels’ inhabitants have toward Urban Leisure spaces, 2 themes, Play and Water are utilized as prisms to analyse the territory. Those two components of the landscape are complimentary tools which are shaping present metropolitan ‘non-work’ activities. [Leisure] Derived from Marxist theories and being directly related to work activitiy, Leisure is usually seen as recreational free-time. Used as a way to relax and empower individuals, the real role of leisure has actually been set by Taylorisation processes aiming to control factory workers’ productivity. By managing their free-time and recreational activities, it allowed factory managers to organise greater productivity rates. The most famous example might be Mussolini, dopo lavoro society. But another essential role of Leisure is linked to childhood. By allowing freetime dedicated to activites which don’t produce anything but experiences, it creates a transformative educative role enacted by the process of play. [Play] Described as futile and loss of time, Play is theoretically defined as being an essential activity for children’s development. It is indeed, the act of playing which forges us to adulthood, giving us the sensorial and social tools to fully apprehend the world. Through Play, by entering into an imaginary abstraction of reality, the player processes concepts and general rules. For this, a transitional object is needed to reassure and ritualise the act of Play. With its materiality, it performs as an interface which allows the participant to cross the threshold of reality.

10

| INTRODUCTION

[Water] Being essential to life, water played an important role in shaping Brussels through its interactions. People have always used water as a sociointeractive tools but water is also a perfect material involved in Play. Pools, fountains and even rain have been used for centuries as recreational ways to interact with water. Its abstract colour and shape properties induce multiple uses and therefore makes it a perfect transitional object for Play. This is why water, used as an interactive Play tools This will be the focus of the present research proposal of this project. [Project] In the intent to invoke new water-play spaces in Brussels, and after a meticulous inventory and understanding of the territory, the project proposes to situate itself on the Pacheco State Administrative Centre. Being seen as the monofunctional office and work space of Brussels per se, its localisation has the potential to reinforce an existing Water-Play network in the pentagon. By introducing those components in the area, it tends to reactivate the abandoned square into a socio-interactive tool attracting passersby on site. This is furthermore put in place with the implementation of a new pavilion hosting communing practices. The introduction of a space permitting local social gathering act as bottom-up process to reintroduce antihegemonic control of the square while connecting local users into a community of commoners. The socio-interactive components of Water-Play infrastructures have great potentialities which will be researched and materialised in the current proposal.

Aims _Understand the Leisure infrastructure of Brussels and induce a new network of transformative and non-prospective Play behaviours linked to water interaction. _Reconsider a capitalistic project intention into a more local and neighbourhood sized anti-hegemonic and inclusive proposal shaped around commoning practices of Water and Play management.

Research Questions _What define the concepts of Leisure and Play in contemporary metropolitan settings?

_Rethink the water management system to locally collect and use rainwaters and transform water as a resource of Play, Refreshment and social-gathering element.

_What can be retained from urban water interactions performances while allowing potentialities for non-prospective and transformative Play behaviours?

_Imagine a Refreshment and Leisure space (urban beach) designed to counter local heat-islands issues in Brussels.

_How to design an activating project, on a public plaza, for a local community of commoners with the intention to define an inclusive and free space?

Methods _Analyse case studies to understand the capacity of Water-Play as a tool to shape common spaces. _Question theoretical concepts Leisure, Play and Water Interactions

of

_Question urban Play and Leisure infrastructures and rethink new ways of inclusive transformative Play spaces.

_How to rethink the urban water management system of Brussels to make it enjoyable for transformative Play and Leisure behaviours while allowing refreshment and circular management of the resource ? _How to foster an Urban Commons community in the modernist and hegemonic Pacheco Administrative Centre of Brussels

_Understand Brussels’ water system and ways to enjoy water interactions in the scope of fostering Play and sociointeractive potentials.

Â| INTRODUCTION

11

1. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

RIGHT TO THE CITY The present reflexion was greatly inspired by the Right to the City movement initiated by Lefebvre in 1968. In contemporary urban context, it is noticeable that some rights are revoked and neoliberal actions are fragmenting and privatizing furthermore Western cities. Brussels, as the ‘capital’ of Europe, didn’t escaped this widespread paradigm. [Minorities] Also, it is even more perceptible if we look at minorities. There is indeed less accessibility to the neoliberal market goods and services as wells as public infrastructures if you are part of a minority groups. Neoliberal markets tend to favour certain individuals. Those minorities include women, people of colours, queers, economically weak inhabitants, homeless citizens, disabled individuals, transmigrants, ethnically discriminated persons and people of elder age. [Inclusive Strategy] For this reason, new ways of imagining a more inclusive and philanthropic city needs to be put in place. We should dream of urban spaces for inhabitant and users, and not for shareholders. [Lefebvre] All these attacks are prohibiting more and more citizens to fully enjoy the city they inhabit. It is not a novel process, Lefebvre already described those mechanisms in the 70’s. [Resisting] A revolutionary group and somehow anti-capitalistic thinkers and urbanists asked for more rights for people in the city. They were reunited around the Right to the city movement and represented by Lefebvre, Mitchell,

Harvey, Purcell, Dikec and Jacobs. They did not ask for more rights in the judicial sense, but to allow people to fulfil particular basic urban needs. A more socially driven city, less merchandised, accessible for minorities. [Right to the city] For Lefebvre, it is crucial to reinvent social interrelations to capitalism and spatial structure of the city. The concept of ownership, is for him a real problem. As he posits, the city needs to furthermore belong to its users in a global interest for society. For him, a spatial resistance to confront spatial hegemony is needed. He explains, that the city is not a spatial material but more feeling of urban space as a physical context to practice everydayness (Lefebvre, 1968). [Heterotopic space] He also posits the notion of heterotopia. It is defined as being the ‘‘delineates liminal social spaces of possibility -where ‘something different’ is possible’’ (Purcell, 2009). For him diversity of space is a crucial urban interactions. [Appropriation] He also manifests the need for appropriation. It is, he says a way to reinvent generic spaces into new usable spaces. This notion is crucial in modern urban planning. [Commons] It is possible to read in Lefebvre and Right to the city movement an ideation promoting a common good. A way to create more distributed opportunities to a wider proportions of the population. This idea of common good generated the pre-existing principles of Urban Commons.

“The right to the city is like a cry and a demand, a transformed and renewed right to urban life.”

14

| THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Lefebvre H., 1968. Le droit à la ville (Paris : Anthopos)

URBAN COMMONS It is in 1980, that the concept of Urban Commons is firstly employed, as an increasing proportion of the population set foot into urbanities. Common is defined as an intermediate space between public and private. A private space belongs to its owners only. A public realm belongs to everybody without any exceptions. The concept of common is situated halfway in between those two notions of spaces. It is a place where a group of people is sharing and managing a resource. They are as open as public but involve particular commonly fixed rules. It produces an intermediate gathering spaces, creating a boundary of action, an exchange of ideas.

[Threshold] The threshold act ‘as door, to separate but also connect to the outside’ (Stavrides, 2015). For Turner, the border and rites accompanying allow the ‘change of status’, it forms an ‘act of detachment’ to a previous position. Such initiation rituals, allow new social links between individual and therefore ‘give rights and obligations’ (Turner, 1969). Those spaces started to emerge as counter-hegemonic way to control spaces. They act as gathering spaces which resist ‘the city forces of ordering and controlling’ (Stavrides, 2015).

ol

Res

toc

sou

Pro

rce

[Properties] A common space is theorized as being a sharing a resource with a group of people, considered a community. The community regulates this resource through protocols. Particular processes prohibit the accumulation of power in such places.

[Permeability] Common spaces don’t belong to a group but belong to everybody. Some conditions such as proximity regulates the proportions of the community. The resource belongs to direct users and a broader community of ‘not-yet-users’. Willingly, this boundary is kept porous but some conditions of entrances are usually solve with the act of negotiation.

URBAN COMMONS

Commoners

| THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

15

Fig. 1 - Hofstade urban beach (Source: Edition L’Heembeckoise, Bruxelles)

16

| THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

LEISURE IN THE CITY The concept of leisure is an easy notion to understand. It is defined as the recreational and non-work activity in ones’ schedule. These activities demand individual implication, and therefore are intentional process which allocated sense of control. This free time offers a feeling of stability and encourages community integration (Caldwel 2011). Usually leisure activities act as a container of positive experiences which involve no sort of productive components. [Role of Leisure] Recreational activities inherent in leisure don’t imply only ‘frivolity but also take part in important developmental and health implications’ (Caldwel 2011). Indeed, they are part the growing-up process of children, if the experimental factor is present. This notion is exploited by the Montessori learning process and is spread worldwide while common recognition is devoted to a new way of learning without having the impression to do so. [Non-work time] If we analyse closely the notion of Leisure it is actually defined as being the contrast of working time. Etymologically, the word Leisure comes from Latin Licere meaning to be allowed or lawful to. This means there is an intrinsic component of control and manipulation associated. It has been used in industrial societies for a productive manipulation as a Taylorisation process. Mussolini doppo lavoro society features the best known example (Dawson, 2016). ‘Marxists have continually stressed the role that leisure plays in adjusting the working class to a subordinate position of capitalist society. Rojek accurately posits Leisure relations are held to create the illusion of freedom and self-determination which is the necessary counter balance to the real subordination of workers in the labour process’ ( Dawson, 1999).

[Social Fracture] As leisure is defined by work relations, it plays a organisation role in ‘class’ structuration. ‘Social class does not exist per se but social stratification effect do. Indeed, working class neighbourhoods with generic popular culture and leisure patterns develop quite apart from the higher status middle or upper class areas where the factory owners live’ (Dawson, 1999). Leisure is influenced by a variety of factors: age, sex, wealth. This is why the owners of greater economic resources have additional opportunities of wider leisure schedule time and variety. For Dawson, ‘leisure and class are inextricable intertwined’. [Exclusion] For this instance, as a way to impose ‘class’ distinctions and foster class solidarity. Members often engage in activities that exclude other socio-cultural groups. It is admirably represented in activities such golf or polo but also in boys clubs or fraternity groups. It is also a way to demonstrate a social status :‘spending on leisure to show their wealth act as increasing the level of prestige arising from occupational level.’ (Rose, 2016) [Leisure at stake] The democratisation of leisure and holidays helped the lower range of the socioeconomic spectrum enjoy furthermore recreational activities but leisure is still ‘tied to economic, politic and sociocultural status’ (Rose, 2016). It leads to some individuals eliminating leisure activities of their life due to the lack of time, money, space or other resources. This issue is even more preoccupying as the ‘middle class’ is constantly shrinking. We do not need to forget that access to leisure should remain a fundamental right, independent of one’s financial situation.

| THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

17

THE CONCEPT OF PLAY Everybody play and everybody have played in their childhood. It is indeed the logical path of every human and animal being. We start our lives with play behaviours which helps us forge tools to comprehend our relatives and surroundings. But what is the exact role of play ? [Role of Play] Instinctively, as we play, we feel it is an entertaining and enjoyable activity. But for Huizinga, Play is not only a foolish moment of bewilderment, ‘It is somekind of ritual process which produces a transformative performance’. It helps ordering the state in the mind and ‘acts for health development and self-expression’ (Caldwell, 2011). The process allows sense of achievement while taking risks and questions social interactions. It can also help to educate about problems and conflicts solving, ‘it is both integration and differentiation, a sage place to try out’ (Caldwell, 2011). It creates the interface which makes possible relational, cultural and physical exchanges. It helps the child to develop a sense of identity, and position him in society. But playing is also an ‘act of creation’ as well as a performance of interpretation and abstraction. It helps oneself to escape the reality, creating an utopian and fantastic world. The logic is not consistent enough as way to embrace life as whole, a bit fantasy and dream is needed.

18

| THE CONCEPT OF PLAY

For Huizinga, play retains a primary role of one’s personal and educational development. Huizinga also posits the 3 main characteristics of Play: voluntary, exceptional moment, timely spatial determination. [Voluntary] Play is a voluntary activity part of the essential process of growing-up. It creates the opportunity to transition and connect with other individuals. Play provides a safe space which is universal and instinctive. Conferred by self-determination and free-will, it is the active action to emerge into a novel status of looseness and instability. It allows an experimental sensing and questioning of one’s environment and social relations. As a result, a child develops behavioural and emotional autonomy. The fact it is voluntary and an ‘internally motivated activity tends to make it more likely to be sustained over time’ (Tyssot, 1950). It allows, as Winnicott describes it, a Space for Potentialities which can be approached and gives visitors the responsibility to emerge into this act of Play. The voluntary factor also gives meaning to the playing process. It is a way to introduce decision-making choices in the developmental process as a transformative and powerful tools for the future adult. It is in itself not an end but more a mean to an end seeking its own purpose.

Fig. 2 - Play: an imaginative abstraction of reality (Source: De Spiegel)

| THE CONCEPT OF PLAY

19

[Special moment] Play is moment of looseness, based on a conception of reality. It creates a portal, exiting from ordinary life, allowing an imaginative interlude. It also is detaching from an ‘appetitive process, seeking an onlyfor-fun aim’ (Huizinga, 1950). Play is a way to abstract oneself from reality to submerge into a new world ruled by elected constraints, a simplified and abstracted representation of the existing. It ‘brings a temporary, a limited perfection’ (Huizinga, 1950). These rules allow the interacting individual to appropriate and shape his own imaginary, making it a safe place for experimental involvements (concept of sandbox). The actor ‘lies in between the antithesis of wisdom and folly’ (Caldwell, 2011). The experiencer is therefore authorized to cross the threshold of reality and interact only with the element he wants to address. [Specific place and time] Play is usually practiced in particular places called playgrounds. It is also usually enjoyed in a precise window of time. This is mainly due to the fact Play needs to separate from ordinary life, and therefore needs a consecrated spot and schedule to initiate the ritual of transition. For Van Eyck, space and time were not consistent enough to define Play, he introduced the concept of place instead of space and occasion instead time. The duration of Play and the withdrawal from the imaginary world, is fixed by the player himself. Sometimes, an act of playing can be repeated in time. The repetition, unproductive task in the real world, is an important characteristic

20

| THE CONCEPT OF PLAY

in the operation. It authorize to revive previous feelings while trying to interpret and control them. [Play vs Game] The act of playing is mainly an individual process of oneself. The concept of game is actually resumed by social play. Board games, footballs and other collective activities are usually incorrectly described with the term play but game do suffer different properties from play. With the notion of game and social interaction the competitiveness factor adds-up. This now create the idea of an aim in the performance which perverts the act of playing. Indeed, in solitary play, winning had no inherent sense. The experimental action of confronting to yourself is also confiscated. The ‘cosmogonic nature of the questioning is also lost. What makes water run ? Where does the wind comes from? What is death?’ (Huizinga, 1950) All these questions are not asked anymore as you have another aim to achieve. The competitiveness and creation of groups also start involving other issues such as exclusion and prestige. This corrupts the naivety of the play-spirit .The rules are not fixed anymore by oneself, but imposed by the group, it creates new constraints. Winnicott also posits that play sometimes involves ‘sexual dualism, a female and male division’. Girls and boys are therefore separated to play with dolls on one side and football on the other side. It creates exclusion and sometime competition in between cis genders. An example could be the condition of women in the ancient Greek version of Olympics Games.

[Transitional Object] In Play behaviours, the interaction object (stick, fabric, plastic toy, ball ...) replace the role of the parental guidance. It is indeed the extension of the mother’s surveillance and security (Klein, 1953). It keeps the connection while the physical presence of the parents is distanced and accompany the player in the risky business of his experiences. It is the interface which allow play, made from a combination of the mind and the physicality of the object. ‘The physicality of the interface allow directness and facilitate awareness while maintaining the complexity and richness of the evolving system’ (Franovic, 2018). The object gets even more powerful if the abstraction of shape and material properties can evoke several meanings. The imaginative characteristic invoked, are then multiplied, they trigger several existing meaning and permit even more adaptative Play behaviours. [Culture] The notions of Play is older than culture. In fact, it is the foundational component of culture. Indeed, civilisation was established with the help of interactions, some of them might have been instinctive Play interactions. Also, in a community of social players, the community of players which is shaped by the game, could start sharing and shaping a subculture. Physical, intellectual, moral and spiritual values raised in play made it to the cultural level of society.’ ‘At adulthood, the transformative factor of play is usually conveyed by cultural experiences (involving art, religion, or philosophy)’(Franovic, 2018).

For example, music emerged from play practices, as a voluntary acceptance and application of strict rules to create rhythms. Contemporary art, with its playfulness and questioning of the reality was also impulsed by play characteristics. It is an emergence of some kind of child innocence to represent the world. [Architecting Play] To design a Playspace, some characteristics need to be taken into account. In order to create the intentional purpose inherent to the act of playing, an interactive system needs to trigger some interests toward its public. For this reason, the materiality of this interface should allow exchange and curiosity. The scale need to be appropriate for a comfortable interaction or it could limit the use. Once the interest is triggered, the explorative experiences need to be shapes. As Van Eyck described them, they should be non-proscriptive and imaginative, and allow a questioning and transformation of one’s personal behaviour. Van Eyck also posited that the place and moment to introduce the play tools are crucial. Lastly, the environment act as interface which question but an ever changing context could destabilize and frighten the user. In any case, the subjectivity of the interaction intrinsic of the player makes it hardly to predict nor interpret if a design would work or not.

| THE CONCEPT OF PLAY

21

WATER USES IN BRUSSELS Water has played a structural role in shaping the city of Brussels. Back in the 1900, the city was totally fragmented by its watercourses. The image we have nowadays of Bruges or Ghent, was actually similar to Brussels at that time. Few major elements did changed it to what is it right now such as the vaulting of the Zenne/Senne and the creation of the Brussels-Charleroi Canal. In this chapter, the scope will be oriented towards the understanding of water elements present in Brussels. It will also understand the shaping faculties and socio-spatial interactions they can trigger. An historical development of water uses will executed to grasp the socio-cultural impacts linked to the management of water resource components.

22

[Fountains] From the XVI century and maybe even before, fountains took the role of the Zenne/Senne and played a major part in providing neigbourhoods in local drinkable water. They were also main exchange places with markets: those gathering spaces allowed discussion while collecting the necessary water for basic needs. Some of those fountains are pretty well known nowadays but most of them disappeared with time. For example, the fountain situated on the Grand Place vanished in 1767 during the renovation of the Maison du Roi. The Mannekenpis also had a vocation to supply a neighbourhood in water, not being like today, an attraction for a myriad of tourists.

A good example to shortly understand the concept, is Berlin (see figure on the adjacent page). The wall and separation of the city, induced the construction of two separate water management systems. When the wall was teared apart, the two metastructures were connected together through huge blue and pink pipes. Those are still visible nowadays. The structural and interactive role it invoked and the role it plays in the city today, is to my concern, an interesting and thought provoking concept to reflect on. The same reflection will be intended on the global history of water interaction in Brussels.

Fig. 3 - Etching of Mannekenpis (1697) (Source: De Fonteinen van Brussel)

The first known use of water of the history of Brussels is the Senne/Zenne. The inhabitants enjoyed the watercourse for bathing and supply them in water for basic needs.

After the years as the water network was put in place in 1900, fountains lost their utility, only providing decorative characters to the city. Since then, they fell into a relative forgetfulness.

Â| WATER USES IN BRUSSELS

Fig. 4 - Location of the Administrative Centre (Source: www.morethangreen.com)

Â| WATER USES IN BRUSSELS

23

Paid Holidays Car Era - 1960

Use of Fountains

1771

Law against swimming in Zenne

1831 1832 1848 & 1849

Cholera Pandemic Charleroi Canal Cholera Pandemic

1864 1866

First Public Bath Vaulting of Zenne

1902

First Shower Pavillion

1930 1931

Invention of Swimwear G.Brunfaut plan

1934 1935

Evere Solarium (1978) Daring Solarium (1950)

1939

Building of Hofstade

1950

Bikini is popular

1980

Building Communal Pools

2013 2016 2021

Kanal Plan Canal Pool Is Cool ? .........

Water Management Plan (PGE) 2002

24

Â| WATER USES IN BRUSSELS

Phase I Hygienism 1860 - 1900 Water / Sanitation

(Security / Nudity)

Phase II Hygienism 1930- 1955 Water / Air / Sun

Running Water - 1900

1500

[Cholera Pandemics] In 1831 and 1848 but also in 1849, several cholera pandemics shook the city. At that time, the city is living a demographic boom due to its industry . The poor conditions of living and hygiene pushed the government and city councils to search for a way to stop and prevent those pandemics. As a response, after discovering the therapeutical role of water, thanks to the work of Pasteur, in the end of the XVIII century, water became an essential element for personal hygiene. An effort was realised by the city to supply all neighbourhood in water and a sewage system was put in place. It is also at that time in 1866, that Anspach start vaulting the watercourses of Brussels in the effort to sanitize the city. It is the first hygienism period. [Public Baths] In 1869, the Superior Council for Public Hygiene voted to endow the introduction of public cleaning facilities. This is how the concept of public baths appeared in Brussels. The idea, inspired by the Frederick Street Bath and Washhouse, was imported from London where it was invented in 1842. From this date, people start taking baths in hospitals (Saint-Jean, Saint-Pierre) at first then in the newly build public baths. The first one will be built in the popular and poor neighbourhood of Marolles, Les Bains Economiques were designed by W.Janssens in 1854. He would plan 60 baths but only 37 will be built (30 for men, 7 for women). They will suffer from a huge success, 8.000 entries in the first year. They were demolished in 1953 due to their poor condition. [Public Showers] In the meanwhile, the concept of shower is appearing in Germany in 1887. Used in the military caserns, the tepid shower is felt to be the bath of the future. On the Place du Jeu de Balles in the Marolles and linked to the cité Hellemans proposal (1905), a more economic showers proposal will take place. A waiting room leads to a

corridor deserving 9 cabins with private cloakroom. Exclusively authorised for men, the price of 15cents, it comprises soap, towel and 15min access to the shower. In 1903, a second pavilion of ‘Bains-douches populaires’ is inaugurated on the Rue de Clé, 18. Most of public shower and baths building were destroyed after the personal bathroom was invented in the 1960’s. [Second hygienism movement] In 1934, a second wave of hygienism hit the country. Promoting access to air, water and sun, the city starts building Solariums. It is at that time that the notion of leisure and relaxation start to become important. The paid holidays introduced in 1936, start to turn pools into recreational places. The solarium of Evere and Daring Solarium of Molenbeek are then designed and built. Both building won’t last long and in the 60’s, due to economic problems , bad weather and car allowing people to travel, the solarium are definitely closed.

Fig. 5 - Daring Solarium (Source: www.reflexcity.net)

[Communal Pools] It is in the same period of the construction the first bathhouse, that the first covered swimming pool was opened in 1879. The Bain Royal, in Notre-Dame-Aux-Neiges district, mainly for the bourgeoisie was demolished in 1969.

| WATER USES IN BRUSSELS

25

At the that, the only hygiene measure taken was to empty the pool once a week. During winter the pool was covered with wooden boards and used as party hall and theatre. The second pool, Bassin de L’abattoire, was constructed in 1901 and alimented by water from the Canal. From this point, pools will emerge as the educational and sportive infrastructure. A huge educational program trained pupils to swim. In 1890 swimming clubs also appear, first for the bourgeoise then it got popularised. As political argument, city administrator start to build communal pools from the 1930’s to content their electors. It will peak until the 90’s. Since then few new pools were open and renovated. To this day no open-air pool are present on the territory of brussels. [Bathroom] In 1890, basic sanitation was done in a basin or a bucket in the middle of the living room. As running water was installed in the city from 1900, a particular apart room was introduced in the housing. The primary bathroom featured a toilet, a tub, a water heater and a shower. 60 years later, in 1960, only 70 percent of the houselholds had a basic bathroom, the rest still used public showers. It is only in the 70’s and 80’s that the bathroom becomes the norm. At that time, bathhouses start to vanish as the use set off. [Bikini] In the XVIII century, people bath into the Zenne/Senne in their birthday suit. Indeed, it is mainly because of nudity problem and prudishness, that bathing is forbidden in the Brussels watercourses. In 1900, the swimming costume is invented. It is composed of a big piece of fabric covering the full body. In 1920, for practical reason and to be able to swim, arms and legs are uncovered. A major turn is made in 1932 when Louis Réart, conceive the bikini. First unpopular, it will become the norm in the 50’s.

26

| WATER USES IN BRUSSELS

[Hofstade] In 1934, as a part of the second hygienist movement, G. Brunfaut designs a urban strategy of public pools for Brussels. Numerous ideas emerged from this global proposal and new open-air swimming pool solutions were envisioned. None of his suggestions were built except the notion of openair urban beach, which made his way to Victor Bourgeois and what is today known as Hofstade. The beach around a lake had a huge moment of success in the 70’s but is nowadays too inaccessible and unattractive and barely survives. [Kanal Plan Canal ] In 2013, the city decided to develop the area around the Canal which was mostly industrial ground with low value. Since then major projects such as Beco Park and Gijs Van Vaerenbergh proposal for a new park connecting the citizen back with their canal. [Pool is Cool] Since 2012, the nonprofit organisation tends to question the inhabitants around water features. Proposing temporary water interaction elements and projects of open-air swimming pools they refreshed the landscape of water related elements of the last decades. [PGE] The Plan de Gestion des Eaux or Water Management Plan was put in place 2002 as proposal to respond to the bad water quality of the Canal and Senne /Zenne. Thanks to this plan a better management of the watercourses is planned. Several proposal such as the reopening of the Zenne/ Senne in Anderlecht were realised. [Urban Water Management] In Brussels, a complex infrastructure of distributive pipes and collecting sewages processes is constitutive of the water management system. In the lower part of the Brussels’ valley, the sewage, which collects the rainwaters and waste water

indifferently, overfloods frequently. This hydric system which doesn’t separate the rain water is particularly poorly thought. The drinkable water is majorly captured in La Meuse and in the Hoyoux sources (Huy) or in other part of the Hainaut. Other sources are forgotten about as they don’t serve any particular function nowadays. Most of their waters are directly discharged in ancient watercourses (Molenbeek, Maelbeek, Geleystbeek) which are ultimately directed in the collectors. Rainwaters, which fall on the urban permeable surfaces: roofs, courtyards, roads and sidewalk, are drained directly in the sewage system also. For those reasons, when it rains, the amount of water introduced in the sewers is overloading and overfloding, to an extent some part of the Canal area flood. In the 70’s, a storm basins were put in place to try to solve the problem. As a consequence, rainwaters are conveyed to the water treatment facilities with the grey waters. Both of them are treated and discharged into the hydrographic network leading to the North Sea. During major rainfalls, the sewers overflood and use the canal and Zenne/ Senne as a storm basin. This reflux is the major factor of pollution (faeces / grey water, laundry soap). While treating the rainwater as a waste, by throwing it in the sewage system, it actually creates more problems. The rainwater is a free and safe resource which is totally neglected. A greater awareness could help to rethink the system and provide circular and resilient solutions. (Both of those cycles, the actual linear water cycle and a revisited circular water cycle are presented on the following pages)

[Water needs] If we think of water as a resource in the global world, its access for sanitation and basic needs involvement is not dispensed to everybody. Indeed, drinking water is not accessible to a growing number of people (estimated to around 1.4 billion). On the other hand, in modernised Western countries, the resource is usually misused and spilled. Some issues connected to pollution are also huge concerns. This is why in 2001, a college of specialists lead by Riccardo Petrella publicly addressed the subject. The idea was to research and propose easy solutions to help distribute basic access to the resource in poorer countries while solving some misuses in more developed societies. Subsequently after, Riccardo Petrella published a book, The Water Manifesto, which is now a global reference. The scope of the book extended the research and theorized the notion of water as common good. He expresses some real concerns about the unconsidered topic of basic water uses and tries to alert the scientific and political actors. The lack of basic water access, is still present in nowadays Brussels. Poorer families, transmigrants and homeless individuals still suffer from it. On the hand, the water management system present in Brussels does not value the Rainwater as its real merit. Another climatic concerns is reinforcing this issue leading to droughts during summer months. This is why an understanding about the water management system will be established in the following paragraphs. [Conclusion] Water has influenced the landscape of urban Brussels in history. Some potentialities to resolve current issues with water-related systems are envisioned in a near future.

| WATER USES IN BRUSSELS

27

LINEAR WATER USE Rainwater

City Tap Water

0,0033 €/ L

Shower

Collected Rain Water

Washing Machine

Grey Water

Toilet

Black Water

Water = Waste

Water Distribution

Water Evaporation

Water = Waste

Kitchen Sink

Sewage Collector

Sewage Water Huge Rainfall / Storms : Collector overflows in Canal and Rivers

Storm Water

Water Treatment Facility Drinkable Water

Zenne Senne

Canal

URBAN WATER CYCLE

28

| WATER USES IN BRUSSELS

DRINKING WATER CYCLE

CIRCULAR WATER USE Rainwater

City Tap Water

0,0033 €/ L FILTRATION

Ground Percolation

Toilet

Washing Machine

Kitchen Sink

Grey Water

Sewage Collector

Water Distribution

Water Evaporation

Black Water

Shower

Sewage Water

Water Treatment Facility Drinkable Water

Zenne Senne

Canal

URBAN WATER CYCLE

DRINKING WATER CYCLE

| WATER USES IN BRUSSELS

29

2. CASE STUDY:

ALDO VAN EYCK’S PLAYGROUNDS

A. VAN EYCK’S PLAYGROUNDS To illustrate and understand the theoretical concepts of Play, Aldo Van Eyck’s playground masterwork will be critically studied in the next pages. His insights and insurgent designs were the concluding elements of the urban theory of Play. Indeed, to this date, no other notable research on the subject is as essential as what Van Eyck bestowed.

the neighbourhoods. The projects featured cheap concrete elements, a hardscape, some metal Play tools and few benches. The affordability and simplicity of the architectural concepts enabled the dissemination of the network. As it can be seen in some pictures, appropriation was also totally permitted which enacts the success of the ideation.

[Context] From 1947 to 1978, Aldo and his colleagues, imagined more than 700 playgrounds in Holland. On behalf of Amsterdam Department of Public Works, he imagined the biggest known network of built playground spaces. Set in the post-second-world-war context, where families had little access to their own outdoor grounds, the need of qualitative public spaces was exceptionally high. The demand to gather and reinforce local communties was moreover increasing. [Potentials] For Van Eyck, the opportunity was too great not to be taken. He reunited his colleagues and went searching for derelict and unused spaces in the city. Subsequently, they then started moulding those new urban spaces. After the war, a huge number of left-over space was available, mostly in familial suburban areas. With his generous act, he empowered the city and gave people access to the potential of urban leisure. This is why the proximity of the future users was essential and makes it a key component of the local strategy of Amsterdam’s playgrounds network. [Layout] The composition of the playspaces was unambiguous: minimalist and geometrical positions had in mind to offer a modest and local answer for

32

| VAN EYCK’S PLAYGROUND

Fig. 6 - Municipal Orphanage Playground (Source: www.arcam.be )

[Free] One last component which conclude the success of those playspaces was the unfenced and free access to the site. For Aldo, the unprotected boundaries allowed children to comprehend the notions of risks and borders. The vigilance of an adult was always present. This allowed interactions between parents and created a safe environment allowing Play. The freeaccess and absence of rules authorised the playground to be an integrated public space granting inclusive access to every citizen without any notion of gender, age, skin colour and other distinctions.

Fig. 7 - Zaanhof Playground (Source: Amsterdam Archives)

| VAN EYCK’S PLAYGROUND

33

34

| VAN EYCK’S PLAYGROUND - Fig. 8

35 | VAN EYCK’S PLAYGROUND - Fig. 9

35

36

| VAN EYCK’S PLAYGROUND

| VAN EYCK’S PLAYGROUND - Fig. 10

37

38

| VAN EYCK’S PLAYGROUND - Fig. 11

| VAN EYCK’S PLAYGROUND - Fig. 12

39

40

| VAN EYCK’S PLAYGROUND - Fig. 13 & 14

WATERPLAY As illustrated on the previous pictures, the work of Van Eyck was extensive and varied. From all this array an intriguing element is dawning. The emergence of water interaction elements is appearing in few isolated projects. [Play] If Play is the main theme addressed by Van Eyck, some projects try the process of research by design to invent new ways of imagining such spaces. Around Play, all possibilities which involves primary non-proscriptive liminal interactions with a transitional object are investigated as a way to remodel spatial assets of playgrounds. [Water Interaction] This is why, Aldo introduced the notion of waterplay in some of his proposals. Two layouts

are features on the adjacent page. They manifest the use of metal frames utilized as water distribution tubes creating a new object. The advantage that such a design offers is furthermore improved by the refreshment properties it addson. Water is used as a social magnet to confront children to new realities of the situation and allow adaptative behaviors. [Potentials] The power of water interaction was not substantially used to its full potential. This is why on the basis of these two recusant examples, the matter of waterplay will be developed further in the project design. It also will provide a refreshing feature which will allow to solve some heat-islands issues present in the urban context of Brussels.

Â| VAN EYCK’S PLAYGROUND

41

ANALYSIS As conclusion to the case study of Aldo Van Eyck’s playgrounds masterplan, some key notions will be summarised.

[Inclusive] All designed playgrounds were free of tariff and made no distinctions between users, creating an inclusive expression urban playspace.

[Leisure] His scope of intervention and generosity allowed the development of the Urban Leisure concept. The after-war context and potentials arisen by the numerous derelict hypothetical sites ensured the success of the urban strategy.

[Local / Common] In some sense, the envisioned public places, offered Urban Commons qualities. Those can be explained by the local integration of the playspaces and adaptative responses of the proposals. The fact the metal structures were used to dry the laundry or dust off the carpets, demonstrate appropriative behaviours relevant to common spaces. The scale of those gathering spaces and abstract formal materialisation granted several additional usages than those expected for Play. The small scale, relevant to the scale of the neighbourhood, tend to respond to a local resolution of the social interactions in the area.

[Abstract] The abstraction of the concept of Play allowed a greater freedom in the design processes. For him, a non-proscriptive liminal interactions with a transitional object was the only way to define transformative Play. Several play tools, as shown on the following page, express his intentions and acted as a vocabulary he employed to adapt to local particularities. Those playtools are concrete geometric volumes, metals climbing components, sandpits and sometime water interactive elements. Other servicing features such as bench, kerbs and vegetation supplemented the playspaces. [Water Play ]A water play interaction was initiated in some of his proposals but didn’t reach a final research completion state.

42

| VAN EYCK’S PLAYGROUND

For those reasons, Van Eyck imagined, without realising it, Urban Commons Spaces in several Amsterdam neighbourhoods.

METAL FRAMES

SANDPITS

CONCRETE VOLUMES

Fig. 15 - 20 (Source: www.merijnoudenampsen.org)

| VAN EYCK’S PLAYGROUND

43

3. CASE STUDY:

WATER INTERACTION

Fig. 21 - Two boys in a pool, Hollywood (1965) - D. Hockney

46

Â| WATER INTERACTION

WATER INTERACTION To further develop to notion of water interaction, introduced in the theoretical framework and in the realisations of Van Eyck, the following chapter will research on water interaction potentialities. [History] Since the beginning of times, humans have interacted with water elements. Water being the essential source of life, it always attracted living beings around its springs. [Art] This attraction and tension around water is extensively represented in culture and arts. The adjacent page illustrate the famous serie of paintings produced by David Hockney in the 60’s. This artist is known to represent pools as his main topics. Other numerous artists, do express with their artistic personalities the interaction between humans and water. The representation signify the importance of this topic.

[An element of Play] In Play behaviours, the transformative aspect introduced by transitional object is of real importance. For that reason, the characteristic of this object were defined to permit most of its transformative properties. An importance toward the non-prospective and imaginative abstraction of the object was called out. For this reason, water could be envisioned as a play element, as an abstract medium allowing imagination and therefore transformative educational performances. On the following pages, a more detailed deconstruction of the different ways of interacting with water is dispensed.

Â| WATER INTERACTION

47

VISUAL The first and most obvious way to interact and enjoy water is visual. The sight of moving water helps calming the soul and create a well-being feeling. Sounds produced by water (like in waterfalls for example) also induce calming properties. The colour, transparency and reflections of the liquid adds even more qualities to the visual characteristics of water.

48

Â| WATER INTERACTION

These properties are used for embellishment since ancient times. Rich romans had decorative fountains and water basins in their patios. The proximity to natural water also allows interaction with a particular fauna and flora present in it. This provide natural connexion experiences which is beneficial for the interacting user.

REFRESHMENT The cooling characteristic of water evaporation are known since ancient times. The fact romans had fountains for decoration purposes also created micro-climates in those patios spreading a refreshing breeze in their villas. In urban settings, lakes and watercourses cool the surrounding environs to a significant and perceivable amount in warmer periods.

The contact of water with skin also creates a refreshing feeling. Indeed, for water to change state from liquid to water vapor, it absorbs the heat of the skin. This process is commonly used during summer in hot climate; showers, baths and pools are taken daily to refresh. Ice, as a solid and a cold state of water, is an additional property known to refresh our drinks in summer.

Â| WATER INTERACTION

49

PLAY

50

One primordial interaction element which will interest the current research will be the Play potentials permitted by water. The abstract shape allowed by fluidity properties of the liquid makes it a wonderful transitional object for Play.

Finally, the movement and dynamism conveyed by the fluid, forces the interacting children to adapt and modify his state of mind toward its transitional object and therefore generate educational adaptative behaviours.

The transparency and therefore, absence of material presence reinforces this notion even more.

For all of these reasons, water is a perfect Play tool component.

Â| WATER INTERACTION

SWIM Another apparent way of interacting with water is to completely submerge in the fluid. The contact with skin, the temperature but also the water resistance questions oneself position to its context. During free-time, the recreational but also sportive action of swimming confer to the practitioner an experimental sense of enjoyment. The fact of moving and floating with a deliberate will into the liquid, is majorly accepted as the notion of swim.

This swimming interaction needed to be taught at an early age or it could lead to some inadvertent accidents. In Europe, swimming classes got introduced in 1900’s and until nowadays is part of primary education program. In the following pages, a concrete visualisation of how interactions are architectured in real life is produced. Those examples are ways to set foot in the designer’s eye towards imagining water interactions in urban settings.

| WATER INTERACTION

51

BELLAMY PLAY-POND/ J. MULDER Following the paths of Van Eyck’s legacy, Jakoba Mulder, designed this Play-Pond in the 50’s. Also belonging to the Ministry of Public Works of Amsterdam in the same era of Van Eyck, she was one part of this emerging social movement which allowed the rich Playscape spaces of Amsterdam. This example on the Bellamy square, shows how she imagined a square as a social waterplay tools for the neighbourhood. This open-air playpond, as she describes, allowed families to gather during hot summer freetimes and refresh. Not only it provided refreshment but also, as Van Eyck

stated, a leisure space, a non-work space, in the city. The proximity and affordance of this non-fenced and local proposal, made this project extremely successful. As it can be noticed, the design of such space is pretty minimal. The hardscape of the square is supplemented by a water feature – a pond, a fountain - but also some vegetation and benches. Those provide, as featured in Van Eyck’s work, the Existenzminimum for a successful surveillance but also for a social gathering of those families. The scale of the project also fits to the Lefebrevian vision of appropriation of the space and Right to the City mentality.

Fig. 22 - Plan of the Play-Pond (Source : Amsterdam City Archives)

52

| BELLAMY PLAY-POND

Â| Fig. 23 & 24

53

TAINAN SPRING / MVRDV This project unveiled in late 2020 is of major interest. Realised by MVRDV, it was first set up by the Urban Development Bureau of Tainan City Government. Several factors make this new urban spaces a major reference. Firstly, the urban context of the realisation is pretty similar to what most Western European city could face nowadays. The previous function of this mall building structure was not used anymore and therefore needed a reassignment. The decision was made to disassemble the building and make a romantic ruin with a more publicoriented function, a park. The mall equipments and structures were recycled and reintroduced back into the economy via exemplar circular processes. The idea to keep the structure was not only cheaper and more environmentally friendly but a good way to maintain the history of the ancient mall. This also gives a particular industrial and urban vibe in this new way of building urban parks.

54

| TAINAN SPRING

The new function, a public park accompanied with a really innovative water feature was imagined to reconnect the citizens with nature and waterscape of their city. Not only greeneries were brought back in this derelict space of the city centre but also social interactions. This was made possible by creating this urban beach where the capitalist leisure function of the mall was transformed into a more common, public, noncommercial park function. The landscaping of the water basin and the ‘beach’ around make it is easy for people to appropriate. The fact that it is situated one level under the city street, makes it a protected pocket while still allowing people to overlook it.

Â| Fig. 25

55

56

Â| TAINAN SPRING - Fig. 26

Â| Fig. 27 & 28

57

THYLO FOLKERTS TEMPORARY POOLS - JARDIN / POOL PORTUAIRE IS COOL Founded in 2014 by Paul Steinbrück, the non-profit organisation Pool is Cool is of real interest for Brussels. Questioning waterscapes and how they are used, Pool is Cool is helping the city forging a debate around its water features. The main aim was to reflect and propose solutions for open-air swimming pools but their insight went way further. It didn’t only tackled the pool system and creation of new open-air structures, it went searching for potentialities in the existing city network. Most of the performances had a limited budget and a temporary time schedule. The participative management and construction of the temporary structures creates bonds in between the volunteers and their interaction helped develop an Urban Common resource management.

58

| POOL IS COOL

Some of those examples are: swimming in La Cambre ponds, installing a temporary pool in a container in front of Bozar Museum, settling a sprinkler system to refresh or closing a roundabout to enjoy its fountain for a weekend. All of those ideas are full of potentials. They act as a social magnet and question the different unexploited usages that water component could reinvent. Pool is Cool members also pushed the city to start testing water quality in natural water spaces, propelling a better water quality and rethinking nonrecreative water management. This increasingly growing nonprofit organisation also proposed lately some consistent proposal for open-air swimming pools and its corresponding socio-economic protocols.

Â| Fig. 29

59

60

Â| POOL IS COOL - Fig. 30 & 31

Â| Fig. 32

61

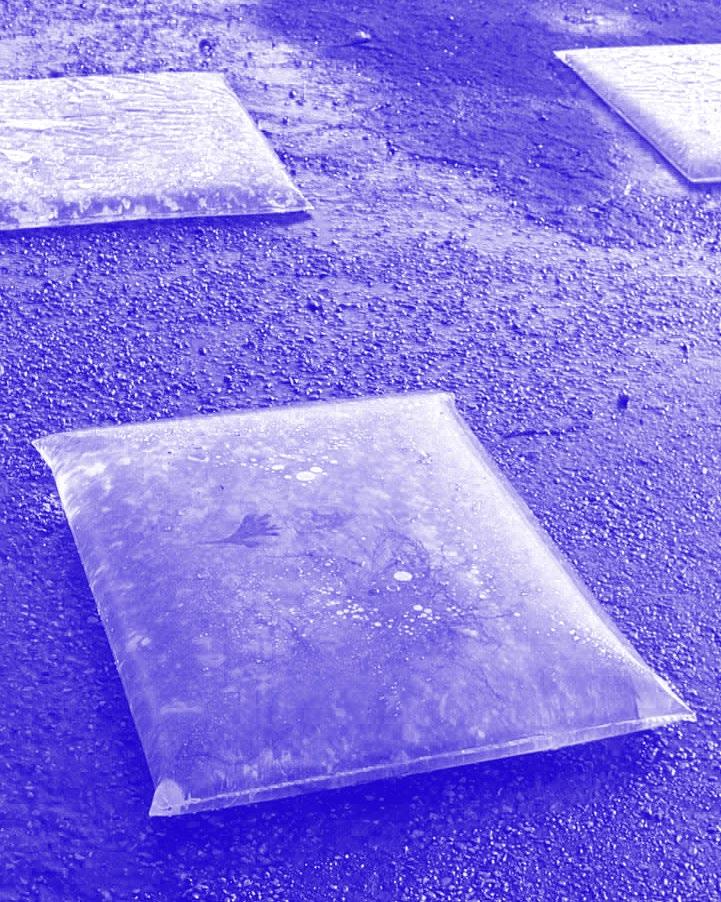

THYLO FOLKERTS JARDIN PORTUAIRE - JARDIN / T. FOLKERTS PORTUAIRE In 2000, in the harbour of Le Havre, T. Folkerts, landscape architect, was commissioned by the city to help it sensitize to water issues. His idea, was to collect water for the harbour and make it accessible to the passer-by. With this action, people could finally connect and play with the surrounding water. 80 plastic bags of 100L were filled and let on the quay for people to play with during 4 days. As a consequence of this performance, a new way to interact with water was produced. Children were jumping on the fluid contained in solid bags imagining new play tool made from locally sourced resource. The designer learned how to collect and make use of an existing resource which was never reachable beforehand.

62

| JARDIN PORTUAIRE

‘‘Once filled with water, the soft, shiny, wobbly and warm pillows virtually asked visitors to touch, sit and jump on them.’’ T. Folkerts (Diedrich, 2006)

Â| Fig. 33

63

64

Â| JARDIN PORTUAIRE - Fig. 34

Â| Fig. 35 & 36

65

CONCLUSION As it is presented in the previous pages, the water interaction element is a crucial urban social-gathering tools. The different properties and interactions inherent to water in the multiplicity of its physical state is wide palette of components to be used for water related urban spaces. [Sanitation] 4 types of relations to water exist: Visual, Refreshment, Play, Swim could be complemented with many others. The Sanitation and hygiene related use of water are not illustrated in the precedent analysis but do play a common role in the topical contemporary society. Knowing this, those notions will be pretty much left out from the project intentions. [Research] Some interaction compounds such as Play and Refreshment and to a certain extent Visual will be more investigated by the project. The Swim and Sanitation aspects are too complex to grasp in the current design situation. The installation of a pool or water management system are indeed a real challenge made of a plethora technicalities which overcomes the scope and expertise available in this research.

66

Â| WATER INTERACTION

[Interconnectivity] The differentiate elements of water interactions can also work together. In the exposed references, it is clearly noticeable that water interactivity compounds could also build on each others. It is as well, in the same way difficult to design a water feature for one interaction component only. It is a mix of different ways of interactive water which could enhanced certain properties due to the spatial and contextual circumstances. An abstracted visualisation of those concepts is presented on the next page.

VISUAL CONNECTION REFRESHMENT

Water

SWIM PLAY

Â| WATER INTERACTION

67

4. BRUSSELS:

URBAN STRATEGY

70

Â| MAPPING THE EXISTING

UNDERSTANDING THE EXISTING To critically comprehend the particularities present in the landscape of Brussels and therefore spot potentialities, an inventory of key infrastructures connected to the Leisure concept was established in the present chapter. As the focus of this research is oriented toward the notions of Leisure, Play and Water, some of those key infrastructures and networks were analysed. [Leisure] When we talk about Brussels’ leisure spaces, parks and waterscapes are the first popping in mind. It is nowadays hard to say if those green and blue spaces where the product of nature or man-made endeavours. Nevertheless the status of those spaces, both are practiced daily by Brussels’ inhabitants. Luckily enough, the metropolis does feature a generous amount of parks and forests. On the plan of Water components, several key elements are emerging such as the Brussels-Charleroi Canal or the Senne/Zenne. These elements played an important role in shaping the city. The vaulting of the Senne/Zenne was one of the most prominent and reknowned works. [Play] Linked to parks and forests territories, playgrounds and outdoor sport facilities are most the second most used recreative components. Those are usually placed around open-landscape situations, mostly around or inside parks. It is hard to map all of them as their small size and communal management keep them from being localised on the extensive territory. The concomitant spatial distribution of playground and sport facility is interesting to notice, as if playground for kids demand facilities for grown-up

nearby. The size of both elements can vary a lot, but even the slightest Play / Sport infrastructure has an impact on how leisure is practiced in urban areas. Some playgrounds are in poor states due to their age and lack of maintenance but the general distribution is pretty correct. [Water] As about the water infrastructure -if we exclude the major water sources like ponds, rivers and canals - smaller elements such as sources, fountains and swimming pools do play an important role for the city. They don’t always connect directly to leisure spaces but do provide interactions with other components which play a major role. Sources for example, are irrigating bigger water infrastructures. They are the most neglected water feature nowadays. Their position and streams were forgotten with time and few of them are still buried. To supplement sources, the modern fountains were placed to embellish mostly urban historical centres. Some of them do play a role in leisure activities during summer like the St. Catherine/St. Katelijn Basin. Swimming pools on their part are known and used for leisure activities. Even if the primary role was to teach how to swim and develop sportive swimming the direction taken by modern pools tend to orientate furthermore into leisure practices of water. [Heat]To finalise our understanding about Leisure in the city, the way climate induce certain activities needs to be taken into account. For this reason, the heat distribution during summer months will be examined to try to propose a complimentary response to temper the impact of such heatwaves and the activity they prevent.

| MAPPING THE EXISTING

71

NATURAL SPACES Brussels features a magnitude of different leisure and natural spaces. Those are usually immense in size but smaller version of natural spaces do exist. It is a hard task to determine what is considered as natural or man-made element of a landscape. For this reason the term natural will be defined as a permanent and landscaping component of the territory. A place which allow connection to natural elements such as trees, grass, water, wind. It is indeed the recreational aspect of those natural spaces which arise our interest.

72

[Rivers and Canals] Few rivers flow in the region, the Zenne/ Senne is reminiscent is some areas of the city, most of its trail was vault due to hygiene problems, Maelbeek, Molenbeek and other small watercourses are also present but mostly hidden on the territory. The Canal is the major element and its surrounding waterscape is currently being transformed due to the city impulse. The Chemetoff Kanal Plan Canal, started in 2012 and is leading to major beautification and gentrification projects.

[Parks]A wide networks of parks, some inherited by colonial past, is present in Brussels. Those green space usually nicely connected, do provide fresh air and calmness the busy city.

[Lakes and Ponds] Other water elements sometime connected to sources like lakes and ponds are shaping the city. The most reknowned are the Ixelles/Elsene ponds, Josaphat ponds, La Cambre ponds and Mellaert ponds

[Private Parks]The biggest parc of Brussels is a private park, the Royal Domain of Laeken. It is the place surrounding the Royal family palace and is therefore inaccessible.

[Hofstade]An important element of the landscape, imagined in the 70’s is the Hofstade lake and beach. The location , tariffs, and accessibility problems lead it to fall into disuse.

[Forests]The Sonian forest and the connected La Cambre forest is a primordial element in the regional landscape. Having a forest in the regional boundaries of a metropolitan city is indeed a lot of luck. This forest, is complemented by other smaller forest also situated in the periphery.

In the pentagon fewer of all these elements are featured. Most of the quoted natural components are present in the periphery.

Â| MAPPING THE EXISTING

Â| MAPPING THE EXISTING

73

SOURCES Since ancient times, sources have been precious resources, providing free drinkable water. Since the last century, and the establishment of the water irrigation and sanitation system, the primordial interest for sources was lost. This lead to a common forgetfulness of their historical presence and social gathering connections they allowed. This water interaction was crucial in the ancient time as it permit social exchanges as we could nowadays envision on social media. If we look closely at the distribution of sources most of them are situated in

74

the urban periphery of the metropolis. The current count is set to 62 sources in the regional border of Brussels. This number could vary in a near future as we are rediscovering some new ones lately. The actual absence of those natural sources in the pentagon arises a real concern. Is it the concretisation of the city centre which doesn’t allow to spot them anymore ? The modest streams and location won’t allow any real use of these sources nowadays but their historical presence should be remembered

Fig. 37 - Ganzenweidenbeek (5)

Fig. 38 - Royal Domain (10)

Fig. 39 - Marly Source (8)

Fig. 40 - St. Helène (28)

Fig. 41 - St.-Josse Church (23)

Fig. 42 - De Fré Av. S. (58)

| MAPPING THE EXISTING

Sources 1.Source of Saint-Landry 2. S. of Keelbeek

19.S. of Paruckbeek #1

3. S. of Tweebeek #1

20.S. of Paruckbeek #2

4.S. of Tweenbeek #2

21.S. of Paruckbeek #3

5.S. of Ganzenweidenbeek

22.S. of Hof Ter Musschen

6.S. of Hembeek

23.S. of St.-Josse Church

7.S. of Meudon street

24.S. of Stuybeck

8.S. of Marly

25.S. of Malou Park

9.S. of Meudon Park

26.S. of Woluwe

10.S. of Royal Domain (private)

27.S. of Parc des Sources

36.S. of Peters’ College (private)

45.S. Rood Klooster

54.S. of Linkebeek

11.S. of Laerbeek

28.S. of Felix Hops

37.S. of Maelbeek

46.S. du Sylvain / Bosgees

55.S. of Peters’ College (private)

12.S. of Keelbeek

29.S. of Paulus Park

38.S. of Koevijver

47.S. l’Empereur / Keizerbron

56.S. of Peters’ College (private)

13.S. of Puits Léon XIII

30.S of Neerpede street #1

39.S. of Langewei

48.S. of 3 Fountains

57.Russian Embassy (private)

14.S. of Kerkebeek

31.S. of Scheldermaal street

40.S. of Calvaire /Golgotha

49.S. of Roodkloosterbeek

58.S. of De Fré Avenue

15.S. of Poelbeek

32.S. of Mellaerts Ponds

41.S. of Ter Coigne Park

50.S of AXA Domain

59.S. of Roosendael

16.S. of Doolegt Park

33.S. of Rietveld van Neerpede

42.S. of Jean Mussart Garden

51.S of Royal Domain

60.S. of Fond’ Roy

17.S. of Mulder Park

34.S. of Neerpede street #2

43.S. of Basse-court / Neerhof

52.S. des Enfants Noyés

61.S. of PappenKasteel (private)

18.S. Amour /Minneborre

35.S. Saint-Helène

44.S. des Pierres /Steenborre

53.S. of Vuylbeek

62.S. of Groelsbeek

75

FOUNTAINS Build for embellishment purposes, fountains have a significant presence in urban settings as well as in our collective psyche. Every inhabitant could describe or define the nearest fountain they know. They exist in different colours, size and shapes. A common distinction is accepted to separate the notion of fountain to the notion of basin. Both of them are manmade water interaction constructions but the word basin describes more precisely a bigger horizontal fountain while the word fountain generally depicts a more vertical and narrow construction.

76

If we look at their distribution on the territory, the pattern indicates a greater presence in the centre of the city. Indeed, those human endeavours were used to decorate public spaces which are mostly situated in the historical centre of Brussels. From the 15th century some fountains did also play a role, a bit like sources, to provide water to its inhabitants. The new typology of water mirrors creates new way of interacting of urban water play. Those novel elements need to inspire new projects especially those coping with summer heat waves.

Fig. 43 - St. Catherine Fountain (20)

Fig. 44 - De Meux Sq. F. (35)

Fig. 45 - Flagey Fountain (43)

Fig. 46 - Calder Fountain (28)

Fig. 47 - Park of Brussels F. (24)

Fig. 48 - Stephania Basin (55)

Â| MAPPING THE EXISTING

Fountains

19. Botanic F. and B.

1 . Centenaire Basin

20. St Kathelijn F.

2. Osseghem Park Fountain

21. De Brouckère F.

3. J. Palfyn F.

22. St Kath. B.

4. Centenaire Boulevard F.

23. Pacheco F.

5. E. Bockstael F.

24. Park of Brussels F.

6. Laeken Park F.

25. Beurs Water Mirror

7. Sq. Prince Leopold F.

26. St Gery B.

8. King Boudewijn Park B.

27. Park of Brussels B.

9. E. Bockstael B.

28. Calder F.

10. Poelbos B.

29. ING B.

38. 2 Tomberg B.

47. Valduchesse F. (private)

11. Miroir Sq F.

30. Conservatory F.

39. Clos du Cinq B.

48. Pêcherie F.

12. Laerbeek Forest F.

31. Little Sablon Garden F.

40. Cinquentenaire Park F.

49. Héronnière Park F.

13. Elia B.

32. Merode St. F.

41. Montgomery F.

50. Tournay Solvay Park F. #1

14. M. Thiry F.

33. Ambiorix Sq. B.

42. Leopoldville Sq. F.

51. Tournay Solvay Park F. #2

15. Patria Sq. F.

34. ERM F.

43. Flagey F.

52. Van Der Elst Sq. B.

16. Dailly Sq. F.

35. J De Meux Sq. F.

44. Albert II Park F.

53. Forest Abbaye B.

17. A. Steurs Sq. F.

36. G. Henri Park F.

45. VUB F.

54. South Water treatment Facility

18. Botanical Garden F.

37. G. Henri Park B.

46. Valduchesse B. (private)

55. Stephania B.

77

SWIMMING POOLS Focusing on swimming pools, this firstly educational and sportive tool, is maybe the most common weekend activity. Indeed the networks of pools is wide and pretty well distributed. If we take the regional borders of Brussels, 18 public indoor pools are present. As a reflexion, the maps also show the pools from surrounding communes. In red, the private owned pools compliment this networks of communal public pools. Those are sometime accessible to public even if not directly subsidized. Some major problems arise from those water infrastructures. The maintaining costs and sometime old age of pools creates lots of financial problems for

78

their owners. All of them are financed and managed by their communes and usually a huge burden for their expenses. Communal pools appeared in the 60’s as a political argument. This is why the distribution is not well-thought as the only objective was to place it within the communal borders. Tariffs are usually cheap but sometimes prohibiting access for poorer population. A variation in price is conducted privileging inhabitants of the commune. Pool rules also prohibit to enjoy freely play and leisure as it is prohibits to play with a ball or eat or wear burkinis.

Fig. 49 - Bain de St-Josse (7)

Fig. 50 - Neptunium (5)

Fig. 51 - Stadium Kinetix (24)

Fig. 52 - Bains de Bruxelles (13)

Fig. 53 - Nereus (3)

Fig. 54 - Villa Empain (30)

Â| MAPPING THE EXISTING

In Brussels

Out of Brussels

1.Neder-Over-Hembeek

19.Pierebad (Strombeek)

2.Omnisport La(e)ken

20.Dilkom (Dilbeek)

3.Nereus

21.Wauterbos (Rhode st Gen)

4.Louis Namèche 5.(Neptunium) - CLOSED 6.Tritton

Private Pools

7.Bain de St-Josse

22.Athénée Royal

8.ERM / KMS

23.Stadium

9.Poseidon

24. Stadium Kinetix

10.Espadon

25.Résidence Palace

11.VUB

26.Aspria La Rasante

12.(Ixelles) - CLOSED

27.Aspria Art-Loi

13.Bains de Bruxelles

28.Aspria Louisa

14.Victoir Boin

29.Castle Club

15.Ceria / Coovi

30.Villa Empain

16.Longchamp

31.Jam Hotel

17.Callipso 2000 18.Sportcity

Sphere of Influence

79

PLAYGROUNDS / OUTDOOR SPORTS Known by most of the youngest inhabitants, playgrounds are essential transitional and leisure urban spaces. Their size and formal conception features extremely wide variations. The implementation of outdoor sport facilities is more recent and less recognised. Those slightly new infrastructures are still pretty much intensively used. The beauty canons and the well-being benefits sport induces do play a role in these behaviours. The combination of those two recreative elements is also pretty new on the territory and allows a more diverse reach of public usages.

80

All these recreative components are featured evenly in the region except for the more dense historical centre which doesn’t allow play as much. The notion of play induced by those playgrounds and sport utensils, does not correspond generally to the definition of Van Eyck’s play spaces. Too much accent is given to the plastic representative shapes, not allowing children imaginative processes. The fact those utensils and play tools only allow one-only way of playing also reinforce this lack of transformative play influenced by the modern playground designs. Luckily not all playground and outdoor sport facility fall into this deviant contemporaneity.

Fig. 55 - Rouge-Cloître (Playground)

Fig. 56 - G. Henri (Playground)

Fig. 57 - Pirsoul Park (Playground)

Fig. 58 - Mudler Park (Play + Sport)

Fig. 59 - St. Pierre Street (Sport)

Fig. 60 - Maximiliaan Park (Sport)

| MAPPING THE EXISTING

Â| MAPPING THE EXISTING

81

HEAT ISLANDS The last element to understand fully the territory of the metropolis is linked to climate. During summer days, some urban locations are experiencing vivid overheating. Those spaces can face a difference of around 3 to 4 degrees higher than the average temperature of the city. This phenomenon is caused by multiple factors such as the albedo effect or concretization of spaces. Human activity and material inertia creates even more heat and adds-on to those effects. On the contrary parks and water infrastructures are enjoying a milder climate. Perspiration of vegetation and water evaporation help cooling. The two present maps realised by

VITO and UrbClim help us comprehend the distribution of those heat islands. In general, the inner dense city areas are conveying more heat (in red) while suburbs and parks (in blue ) are usually colder. The potential and inertia of water elements used to cool is of real interest, this process is known since roman times. On the figure below, a zoom of the heat map was overlayed with the other infrastructures previously studied. We can clearly see there is a potential to address in the pentagon (chosen site).

Fig. 61 - Heat Islands Map of the pentagon (From a base map of VITO & UrbClim)

82

Â| MAPPING THE EXISTING

Fig. 62 - Heat Islands Map of the Region (Source: VITO & UrbClim)

Â| MAPPING THE EXISTING

83

84

Â| URBAN STRATEGY

URBAN STRATEGY : WATERPLAY NETWORK As a conclusion, an overlay of all key infrastructures on the same maps helps create connections between them. The absence of certain elements also questions potentialities of projects.

[Heat Response] The pentagon is also, as shown on the heat islands maps, the most concerning. For this reason also, the pentagon will be framing the potential sites.

[Pentagon]As first stand point, the resolution area, will be mainly focusing on the historical centre of Brussels, bordered by the pentagon. This area is of greater interest due it’s density and reduced amount of public and common spaces.

[A network of WaterPlay] It is envisioned that to solve the problems linked to lack of qualitative public spaces, lack of Playspaces and lack of Waterspaces in the pentagon, a network of new Play and Water spaces should be introduced. This network could profit from some already existing infrastructures. It is a selection of prospective and existing WaterPlay elements. Some of those are illustrated on the next page.

[Lack of Playspace] The evident lack of Playspace within the hypercentre’s borders is arising a potential of projection. The only 4 playgrounds are definitely not enough for the density of population welcomed by the city centre. [Lack of Waterspace] The only water presence in the centre is featured by fountain elements and the underground and hidden river Senne / Zenne.

[Site election]As a starting point of the network, and compared to the already existing infrastructure locations, the Administrative Centre was chosen as the elected site. Other factors such as dimension, complexity and monofunctionality influnced the choice.

Site

| URBAN STRATEGY

85

Fig. 63 - Beco Park Fountain (Source: www.jacquesteller.files.wordpress.com)

Fig. 64 - St Katelijne / St. Catherine Basins (Source: www.bx1.be)

86

Â| URBAN STRATEGY

Fig. 65 - Flagey Fountain (Source: www.photocory.files.wordpress.com)