Statement

Mohamad AlSharif, born in Syria, raised in Saudi Arabia is a trained architect, receiving his bachelor’s degree in architecture from the University of Kent, England in 2020. Inspired by the Middle East’s deep architectural heritage to becoming a host of great contemporary architecture. Mohamad is greatly inspired by the power of architecture in its ability to transform places, buildings, even people. He believes that architecture is a great responsibility, as it is the mere fabric that shapes the destiny of a particular place. Mohamad is greatly interested in the fields of material science, and preservation of existing architecture. Mohamad is also passionate and curious about the intersection of urban mobility and architecture.

Mohamad is currently pursuing the Master of Architecture II at SCI-Arc, where he continuously experiments with the future of architectural thinking. He is constantly interested in emerging technologies in all fields of architecture and design. He currently is experimenting with how architecture and urban mobility could be better integrated and interlinked.

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Symbiotic School

William VirgilSymbiotic School is a educational project that was undertaken during the first semester of SCI-Arc. The project revolves around a speculative approach to conventional notions of architectural design. The brief required the building of a permanent elementary school to the existing Diamond Ranch Highschool, which was designed by Morphosis in 1996. The studio challenges the “regular” techniques and workflows that take part in making an architectural project. The process began by creating handheld objects that conveyed a sense of space. The Challenge was to create such objects, by using familiar objects such as shoes. The objective was to abstract the pieces of the shoes into an object that conveyed space. The narrative was then derived from the relationship between the shoes and the human. The narrative was if shoes were given agency, one would imagine that shoes would almost fight back there users in order to gain control over the host. The narrative of the shoes would then carry over into the final design of the project.

After the shapes were formed, they were 3D scanned, and imported into Zbrush. The Boolean, as well as its mesh management capabilities were key in making this project a reality. The Volume were used as objects to carve out space from rectangular extruded forms that were of the typical size, and volume of an elementary classroom’s dimensions. The school was in essence designed from the inside out. The form of the school was purely informed by the design decisions made on the exterior. As such the symbiotic design language was present in the form, which can be traced back to the original abstracted objects. The symbiotic design languages then carries through on the outside, where the form of the building makes an attempt at assimilating itself amongst the existing school around, which in itself is a symbolic play on what it means for children to find themselves in the world as they progress through life.

Final Abstracted Model 1

Final Abstracted Model 2

Mohamad AlSharif

Southern California Institute of Architecture

Mohamad AlSharif

Southern California Institute of Architecture

These small objects were bi-products of the main shoes that were dissected. The following small pieces were much like the large abstracted pieces, were made with no program in mind, they were simply explorations in form

The small objects were then used as boolean objects to further abstact the large foot pieces digitally. The process was entirely based on a few components that added up to be much greater than their basic components.

The symbiotic chair was a piece of furniture which was commissioned as part of the 2GAX at SCI-Arc during the DS1200 Studio, which revolved around creating a new elementary school, as part of an existing school. The task was simply, to create a piece of furniture which followed the same design language as the building in which it is being housed. Therefore, the design of the chair references the organic nature of the building, as well as the abstracted shapes that informed the design of the building. The chair attempts to make a symbiotic approach to design a chair

Classroom 1

Classroom 1 was designated to be an activity space, the key challenge was to carve out a space that allowed the class’s instructor to always maintain visual contact with all the pupils of the class. As a result, the viewing angles all around the class room were a key design factor

Classroom 2

Classroom 2 was designeted to be a flexible and resilient library, as well as a space of congregation for the elementary school. The form of the classroom was dictaed by the 3D scans of the shoes, which were then used as booleans objects in order to carve out the volumes of the space.

Classroom 3

Classroom 3 was designeted to be a creative space for the exploration of creative arts, therefore it was important to create segreagted spaces to allow those classes to take place.

Exterior prespective

The overall exterior form of the new addition was designed to echo the same formal design language of the exisiting school. The new addition mimics the large cantilever that is present in the exisitng school. The new addition also blends in it’s own design languge that allows it to set itself apart from the surronding context while also making an attempt at assimilation to the surronding context. The form of the new building also makes a symbiolic statement about the trials and tribulation of growing up within a world, and in the way kids must find their own way in life.

Interior prespective

The interior froms where derived from the 3D scanned abstract models. The 3D models were primarily used for boolean operations to create complex architectural volumes. The insertion of typical furniture types as well typical architectural, mechanical and electrical details grounds the space into a sesne of reality.

Mohamad AlSharif

Southern California Institute of Architecture

Mohamad AlSharif

Southern California Institute of Architecture

Fall 2022

Rachael McCall & William Virgil

Fall 2022

Rachael McCall & William Virgil

Un-Intentionally Opaque VS 4200 Visual Studies

Un-intetionally Opaque was about a modern take on a self-portrait. The modern “self-portrait” onto a physical product. The process started with 3D scanning my face, as well as my partners face. The geometry was then put into Zbrush, which allowed a great deal of flexibility, and abstraction. In Zbrush simulation were run in order to ensure fitment of the new geometry onto the existing IKEA lamp. Alpha maps were used as extraction onto the new

geometry in order to obtain a usable thickness of the material, which in turn would better control the light fall off. The key design challenges of the project was controlling the thickness of the material as well creating enough opening for the light in an even density around the entirety of the lamp. This thought process is what lead to one side being much more opaque than the other resulting in two different lamp experiences, by simply turning the lamp shade 180 degrees.

Our faces were scanned using the available 3d scanners ar SCI-Arc. It was challenging to get a clean scan, while letting keeping our bodies still enough. Eventually, we cam to the conclusion that it is best to sit down on a chair, and to have someone rotate the person along the Z axis, while the 3D scanner is on a tripod. This minimised the amount of duplicate geometry, which allowed us to get clean geometry to the manipulate in Zbrush.

Southern California Institue of Architecture

Mohamad AlSharif

Southern California Institue of Architecture

Mohamad AlSharif

The lamp shade was vreated in Zbrush. After the faces were combined into one singular mesh. Images of tentecles were used as overlayed masks, in order to abstract the shade from just being two faces. To contrast the kraken like masks on onside, a bitmap was generated using AI. The bit was a starck constrast to the kraken images.

Mohamad AlSharif

Southern California Institute of Architecture

Mohamad AlSharif

Southern California Institute of Architecture

SFMOMA ReSkin

Randy JeffersonAdvanced material tectonics revolved around breaking down and understanding the tectonics of complex façade systems. The SFMOMA was the given façade. The SFMOMA extension designed by Snohetta is ground breaking project for composite panels. The extension stands as a proof of concept for FRP as a material to be used in high rise buildings. Moreover, the SFMOMA used FRP in a curtain wall framework, which allowed the manufacturing and installations time to be brought down to

under a year. The second part revolved around transforming the façade. The transformation called for a speculation that what if the designers of the buildings had opted for a different aesthetic approach, what tectonics implications would have to take place. Inspiration was taken from Kengo Kuma’s Aspen art museum. After assigning a new aesthetic quality, the tectonics of the buildings were then reverse engineered in order to make the assigned aesthetic quality a reality.

Annotation Key

Layer 1 : Primary Structure

The primary Structure of the museum is comprised of a steel crossbraced frame with poured in concrete floor slabs

Layer 2 : Secondary Structure

The secondary layer is comprised of the double mullioned curtain wall, which also incorporate the flanges that support the catwalk and secondary structure

Layer 3 : Tertiary Structure

The secondary layer is comprised of the double mullioned curtain wall, which also incorporate the flanges that support the catwalk and secondary structure

Layer 4 : Final

The final layer is the weave component of the facade which is hung from anhor plates attached along the vertical extrusions found in the secondary structure

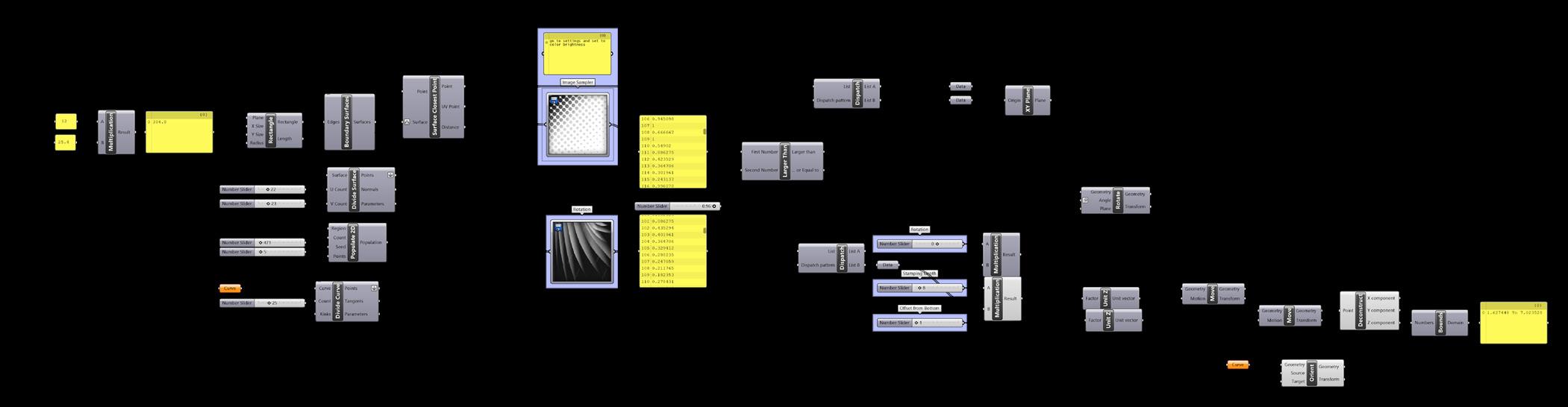

3D Graphic Statics

Fall 2022

Matthew MelnykThe 3D graphics statics assignment was about taking 2D graphics statics, and modernising the method of translating these seemingly old methods of understanding forces within the structure.

The assignment called for the creation of a piece of gemotery that would incorporate three sided, 4 sided, as well 5 sided objects. These objects were arranged in a particular way, so that all the seams would align. After doing so the software would run, and would output a representation of the forces acting within the structure.

Intentional Architecture

Fall 2022

Marcelyn GowIn “Changing my mind: Occasional Essay’s”; Zadie Smith Informs readers of her experiences throughout her career. She describes how her opinions have shifted since the beginning of her career as she was mainly a reader, and after moving onto the present time, as now she is mainly an author. The premise for this shift in perspective comes courtesy of Roland Barthes, and Vladimir Nabokov respectively. Smith compares, and contrasts Barthes’ “Death of the Author”, versus Nabokov’s “Good readers and good writers”. In essence, Smith found herself aligning with Barthes, at the beginning of her career, and Nabokov at the current point in her career. While Smith’s text remains neutral on the subject matter, it does leave the reader questioning what is perhaps the correct argument to side with. This argument could be applied to all creative fields, architecture being one of them, where the same argument runs deep and poses the same question. What is the relationship between the designer, and the end user? On the other hand, is all architecture built and designed in the Nabokov style of thinking?

The topic of voice in architecture is incredibly relevant in today’s day and age, simply because as emerging technologies, the likes of AI, allow for the rethinking of the role of designers in the contemporary workflow. As a result, it is imperative to define the role of the “authors” of a particular piece of architecture.

It can be argued that all architecture is erected with the intentional ‘Nabokov’ style of thinking as every design decision is intentional, whether be it consciously, or unconsciously. In Smith’s text, both arguments are pitted against one another. To dive deeply, Barthes’ argument stems from an anti-intentional background meaning that a text “is not a line of words releasing a single ‘theological’ meaning”1, but rather that the meaning of the text is up to the reader to formulate. Meanwhile, Nabokov’s argument is rooted in the concept that the reader must attempt deciphering and understanding the ultimate intent of the text, surrendering himself to the world the writer depicts. However, a shift of perspective shows that the arguments fall under the same scope of thought. The shift in perspective argues that Nabokov’s argument of deciphering is the overarching argument, to which Barthes’ argument of disentangling falls under. In essence, even the disentangling act that Barthes is urging for, is granted by the deciphering act of Nabokov. Ultimately, the disentangling act is a form of deciphering that an author orchestrates, but intentionally broadens the borders of control.

The disentangling act that Barthes refers to relies on vagueness to be successful. Vagueness, as Michelle Chang describes it, is when “discrepancies arise between the precise meanings of words, vision, and images”2. In this case, specifically, the disentangling act relies upon the author, or designer to set up a vague borderline case, where the boundaries of a case lack specificity. This intentional lack of specificity is the prerequisite for the Barthes argument to fall under the Nabokov argument. Moreover, it could be an author intends to allow the reader to begin disentangling, which in itself is a deciphering act since it was the author’s intention for the reader to set on his own journey of thoughts, which is enabled by the vagueness that was intentionally placed.3 It is important to highlight that most bodies of text are usually not one or the other, but rather a weave of both alternating between each other. Architecturally speaking this happens often. Most buildings are not Euclidean in the way they are planned, meaning there are portions of a building that are meant to be deciphered very easily, and some that are meant to be explored, and disentangled within certain limits that are placed by the designer of the physical space. It is the architect’s role in this case to guide users on a journey, and it is the architect that dictates when it is permissible for the user to decipher, and when it is time for a user to set off on an untangling journey. Moreover, the very best designers, are the ones that are able to employ these strategies, allowing users to go in between both states as they experience a certain piece of architecture. The Jewish Museum in berlin is a great building to illustrate how the two arguments of Nabokov, and Barthes are building upon each other. The Jewish Museum was designed by Daniel Libeskind, plotted throughout the museum, are plenty of moments where users are required to decipher and others to disentangle. To begin with, the exterior facades of the building are very intentionally vague, and non-memorable, the height, and the proportions

are much the same (Figure 1). This design is very intentionally vague in that, playing a secondary role to the surrounding baroque architecture (Figure 2), it does not hint at what the contents of the building could be. That is precisely why an act of disentangling is required. While it may seem accidental, it is not at all. The designer invites the user to indulge themselves in an act of free thinking. Nevertheless, it is important to highlight that the designer orchestrated the entire progression. Libeskind did have the opportunity to create a façade system that is more expressive of what the building beholds, which would more “classically” follow Nabokov’s argument, yet he deliberately decides to leave room for interpretation, thereby engaging a user in a multitude of experiences. Moving towards the interior, and the end of the exhibition guests enter a narrow, dark, grey concrete room with a narrow sliver of a skylight that allows sunrays to enter the space (Figure 3). This is a clear example where Nabokov’s argument is being classically used. Libeskind intentionally creates a very detailed rich space for users to begin to decipher the meaning behind the light. Users are forced to think much like the designer himself, recreating the journey that the designer undertook to reach that particular end product.4

Highlighting intentionality is a key aspect in the discourse of architecture. Architecture is always intentional, which is an important statement amid the current developing nature of technology within architectural design. Breakthroughs in form finding, and image-making technology regularly question the role of designers in all creative fields. Nabokov’s argument proves that all decisions made by designers are intentional because it is the intentionality that cements the idea that a designer is always the genesis of a design no matter what tool is used to produce an outcome. It is that human ownership of the design, that breathes the sentient qualities into the non-sentient elements of architecture, which ultimately translates into more humanistic experiences for end users.

Berlin Jüdisches Museum Und Der Libeskind-Bau (Cropped).Jpg. n.d. https://upload. wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a5/Berlin_J%C3%BCdisches_Museum_und_der_ Libeskind-Bau_%28cropped%29.jpg.

Chang, Michelle. “Something Vague.” Essay. In Log 44, 103–13. Anyone Corporation, n.d. “The Death of the Author.” Roland Barthes, 1967, 74–88. https://doi. org/10.4324/9780203634424-13.

Foucault, Michel. What Is an Author?, 1969.

Introduction to Nabokov (as Critic). YouTube. YouTube, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=ugsgW0PTRVs.

Jewish Museum Berlin. n.d. https://libeskind.com/work/jewish-museum-berlin/. Jewish Museum. March 21, 2022. Berlin Attractions. https://www.berlin.de/en/attractionsand-sights/3560999-3104052-jewish-museum.en.html.

LaValley, Michael. “Architecture and Ego: The Architect’s Unique Struggle With ‘Good’ Design.” Architizer. Accessed October 2, 2022. https://architizer.com/blog/practice/ details/architecture-and-ego/.

Libeskind, Daniel. “She Has Brought to Architectural Photography a Mysterious Dimension”: Daniel Libeskind on Hélène Binet. December 16, 2021. https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/ article/ra-magazine-daniel-libeskind-helene-binet.

Loomans, Taz. “DEAR ARCHITECTS, PLEASE STOP TRYING TO IMPRESS OTHER ARCHITECTS AND JUST BE MORE HUMAN.” Web log. Blooming Rock (blog), November 27, 2012. DEAR ARCHITECTS, PLEASE STOP TRYING TO IMPRESS OTHER ARCHITECTS AND JUST BE MORE HUMAN.

Roland Barthes’ Death of the Author Explained | Tom Nicholas. YouTube. YouTube, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B9iMgtfp484.

Roland Barthes’s “Death of the Author,” Explained. YouTube. YouTube, 2022. https://www. youtube.com/watch?v=JcNoDMSBHP4.

Smith, Zadie. “Rereading Barthes and Nabokov.” Essay. In Changing My Mind Occasional Essays. London: Penguin, 2011.

Wimsatt, W., and Monroe Beardsley. “11. ‘The Intentional Fallacy’.” Authorship, 1954, 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781474465519-013.

Architecture & Spatial Control

HT 2201 Theories of Contemporary Architecture

Fall 2022

Erik GhenoiuIn 2003, downtown Columbus, Ohio underwent a substantial revitalization, spearheaded by the expansion and refurbishment of the Greater Columbus Convention Center. Many amenities were being reintroduced such as great restaurants and shops. However, at that time one trip across the High Street bridge into Short North neighborhood, signs of economic decline were evident. Shop fronts were boarded shut, apartments were left vacant, and the streets were riddled with homeless. In 2004 David B. Meleca Architects along with the city of Columbus, and the Ohio department of Transportation proposed a redesign of the bridge to facilitate and allow Short North to reap the economic benefits that downtown was experiencing. According to Jeff Speck author of Walkable City, this project is a resounding success, however the intent of this article is to highlight a different stance on the I-670 cap project. The success of the project will be measured through the lens of Keller Easterling’s book Extrastatecraft: The power of Infrastructure space. Easterling dives deeply into infrastructure space, and the way that it shapes urban forms. She describes how and what makes up the infrastructural matrix in which buildings are suspended from. Specifically, Easterling addresses the infrastructure that is not hidden, rather the opposite. The infrastructure that is visible, Easterling describes it as an operating system that shapes the cities, and their skylines1. The aim of this article is to highlight the attributes that an urban activation renewal project must address to be successful. What are the key factors that a project such as I-670 cap must address for it to affect the urban fabric of a given location?

These types of urban regeneration projects are not new but are increasingly popular due to a variety of movements across the industry that share a common theme of reclaiming buildings, infrastructure such as bridges, and highways2. As these sorts of projects gain more and more momentum, it is imperative to evaluate them critically to understand how they affect the social economic fabrics of their context. Moreover, it is crucial to decipher the project’s point of view in relation to the urban matrix, using Easterling’s material as a reference.

Back in 2003, as downtown Columbus was on its way to revitalization, city planners noticed that the economic boom that was transpiring throughout downtown was not carrying over to the outskirts of the city. Like most north American cities, many neighborhoods were torn down in the 1950s to make way for interstates that would pass through the downtowns, and Columbus was one of many3. Consequently, downtown Columbus is surrounded by interstates, which meant that this economic boom was simply unable to filter through the interstate and into the surrounding neighborhoods, and Short North was no exception. The interstate was acting as an invisible great wall dividing the city, creating islands of economic growth, without the ability of intermixing. The economic boom, which in most cases is pedestrians exiting the convention center, or city center, then shopping in downtown, was partly trapped due to the poor connections between downtown, and Short North. The only connection was made up of a lonesome bridge designed to carry vehicles, with very narrow, and uninviting walkways on either side (figure 2). The bridge at the time was a tear in the urban fabric. Users experienced a lack of comfort when walking across the bridge, because the building height to road width ratio was off. It was off due to the lack of any buildings on either side of the bridge. Downtown & Short North feature building height to road width ratios that are deemed comfortable by the human mind. These comfortable ratios did not exist on the bridge, making it feel uncomfortable and unsafe. That bridge was instantly deemed an uncomfortable experience by the mind. It remained this way until 2004, when Meleca Architects, along with the city, and the Ohio department of transportation intervened, adding two parallel bridges to which retail units were built upon to “patch up” the aforementioned tear, created by the interstate, in the urban fabric (Figure 1). Consequently, pedestrians are now invited by the architecture. to make their way across the bridge without ever knowing that they are crossing a bridge, with an interstate right beneath them. The project has been successful at moving the foot traffic from downtown, and into the Short North4

While many practitioners and leaders in the design industry consider this project a success. It can be argued that Keller Easterling does not. In Easterling’s book, it is argued that cities are “no longer made up of singularly crafted enclosures, uniquely imagined by an architect, but reproducible products set within similar urban arrangements”5. This repeatable formula of space is what Easterling claims to be Infrastructure space, which in turn is making up the current urban context of cities. This infrastructure space acts as an operating system for shaping the city6. Easterling describes the two types of forms in cities, one being the object form and other being the active form. The object form is described as what architects are most accustomed to designing, which is usually buildings. The active form, on the other hand, is what empowers the object from. The active form is the binding agent that dictates the formulaic arrangements of how the objects forms are multiplied, organized, and circulated. For example, in suburbia, the active form is the multiplication factor of all the single-family homes. Easterling argues that key people have exploited their positions of power and the active form for the sake of reaping economic gains and incentivizing investments in a variety of forms such as the free zone. Furthermore, she urges designers to regain control of the active form, as well as employ the active form in the same manner. Easterling makes it clear that it is the duty of the architect to understand and manage spatial phenomena and manipulate them to generate a shift in the way active form is deployed in the city.

Meleca architects have exploited the dark matter of the active form to their advantage, to create an object form that reconstructs the connections between neighborhoods. Meleca architects have remedied the urban tear by adding retail buildings with appropriate building height’s to better match the width of the road, which greatly improves pedestrian comfort. The presence of these buildings also creates uninterrupted store frontage between downtown and Short North neighborhoods, creating moments of normal urban life along the bridge and increasing the comfort of pedestrians even further (figure 6). Lastly, the colonnade of the project street further enhances the functionality of the project as the colonnade provides shade from various weather conditions, allowing for greater utilization throughout the year.

Easterling also points out that “Just as the car is a multiplier that determines the shape and design of highways and exurban development, the elevator is a simple example of a multiplier that has transformed urban morphology”7. In essence, while the I-670 cap project is a step in the right direction, it does not employ the active form’s strongest attribute, the multiplier effect. A city will only adapt and change “because of the multipliers that circulate within it”8. Therefore, it is logical to conclude that to create real change, a cluster of similar projects will most certainly trigger a shift in the archaic urban morphology. In Easterling’s point of view, the I-670 cap project is simply the tip of the iceberg. A possible scenario where the active form is utilized to its fullest potential, is if all of the bridges that are connecting surrounding neighborhoods to downtown were remedied in the same fashion as was the North High street bridge.

In Conclusion, it is important to be cognizant of the powers & limitations that object forms present. Moreover, it is crucial for designers to also comprehend the power that active forms present. Active forms offer designers with unprecedented amounts of control to expand the potential dispositions that an object form could hold over a city’s infrastructure space. The most successful object forms are often ones that employ the matrix’s strongest attribute mentioned above. Successful projects in this realm therefore are the ones that end up creating ripples and shifts in urban environments.

Bibliography

4 Ways to Make a City More Walkable | Jeff Speck. YouTube. YouTube, 2017. https://www. youtube.com/watch?v=6cL5Nud8d7w.

Bruntlett, Melissa, and Chris Bruntlett. Curbing Traffic: The Human Case for Fewer Cars in Our Lives. Washington, DC: Island Press, 2021.

Easterling, Keller. “Chapter 1 - 6.” Essay. In Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space. London: Verso, 2016.

Gandy, Mathew. The New Blackwell Companion to the City. Edited by Gary Bridge and Sophie Watson. Chichester: Wiley-blackwell, 2013.

Project profile: The Cap at union station. FHWA. (n.d.). Retrieved November 29, 2022, from https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/project_profiles/oh_cap_union_station.aspx

SPECK, J. E. F. F. (2022). Walkable City: How downtown can save america, one step at a time. PICADOR.

Keller Easterling, “Extrastatecraft”. YouTube. YouTube, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=SaKoIP5qH8E&t=3813s.

Keller Easterling: “Extrastatecraft”. YouTube. YouTube, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=03xqKvwcAF4.

Marohn, Charles L. Confessions of a Recovering Engineer: Transportation for a Strong Town. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2021.

Marohn, Charles L. Strong Towns: A Bottom-up Revolution to Rebuild American Prosperity. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2020.

Meleca, David B. “I-670 Cap.” David B Meleca, 2004. http://www.melecallc.com/portfolio_ page/i-670-cap.

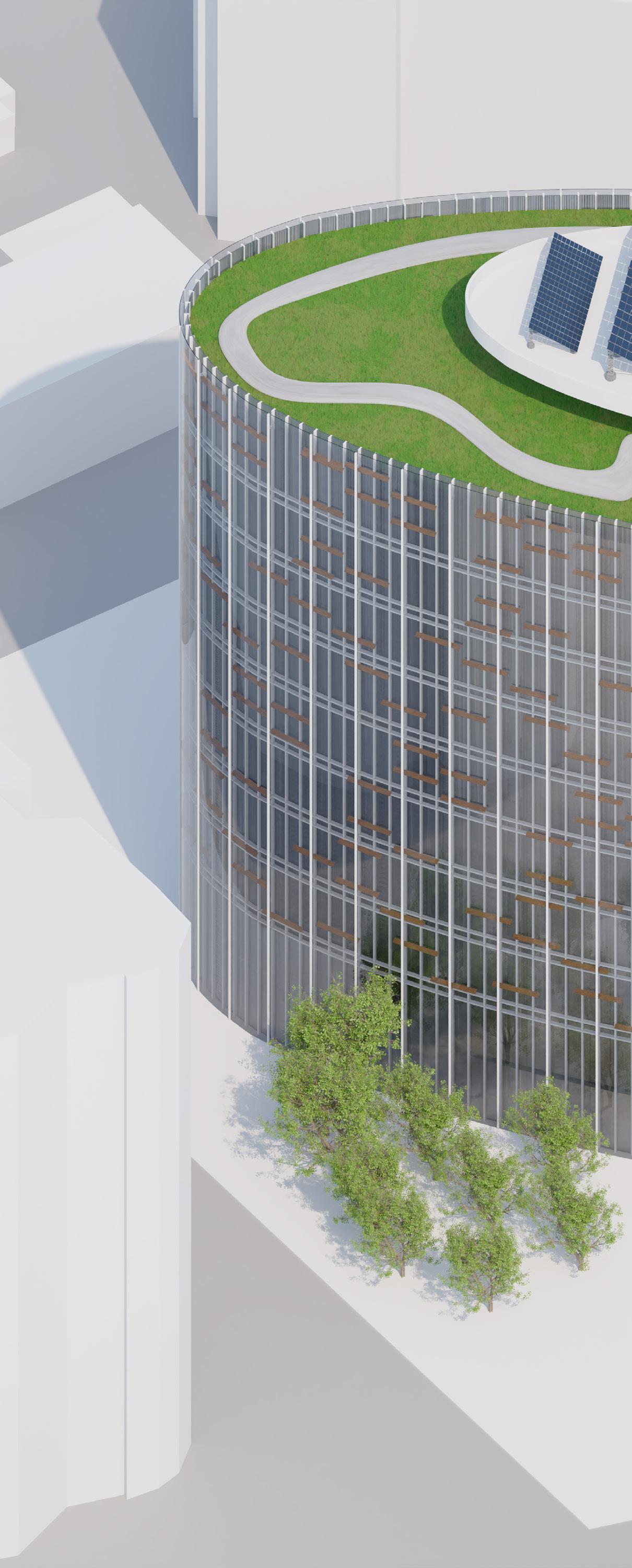

For-Ply Tower

Elena ManferdiniThe brief was to breathe new life into 15 towers situated in the bustling heart of downtown Los Angeles. Presently, these structures are beset with low occupancy rates, as well as a long-standing issue of homelessness. The directive entailed a complete reimagining of the towers in anticipation of future needs. Thus, a compelling narrative was conceived to serve as a reference point for the new tower design. We were given the US bank tower. Exhaustive studies were conducted to comprehend the practical limitations of the US Bank Tower, and based on our findings, we surmised that the tower of the future must be versatile, incorporating public transportation, and incorporating eco-friendly features to combat climate change. The program had to be multifaceted to accommodate the housing needs of the future while simultaneously addressing the issue of office vacancy. A comprehensive mixed-use program was devised, with residential, commercial, and retail spaces thoughtfully arranged throughout the building, thereby doing away with the outdated Euclidean program. The integration of public transportation into the tower was deemed necessary to support the new program, and an innovative transport

system was devised to circumvent the issues of the current transport system. The airborne bus system directly links to the building, providing users with unprecedented access to the tower and reducing pressure on the new vertical circulation system.

The vertical circulation system itself was inspired by Ferris wheel pod design, which ensures that the pod remains upright through the use of gyroscopes. The new elevator, mounted on a rail network along the building’s facade, can move up, down, and sideways, allowing for greater flexibility as the tower’s program evolves. The old elevators were removed, and the core cleared, enabling the placement of two large fans strategically positioned to create a carbon capture system. Finally, at the ground floor, the building’s massing tapers, creating a sense of lightness and transparency. The ground plane is cleared up to the seventh floor, creating a low-rise market that attracts foot traffic to the tower. The result of this transformation is the For-ply tower, aptly named for the four interventions that reshaped the US Bank Tower into the new structure with four exterior skin layers.

Process

In line with the project to create a sustainable tower of the future. We decided to keep the building, instead of tearing the building down, and starting fresh

A reduction of the overall building massing at key areas throughout the towers form

The new transport system stations are integrated into the building taking advantage of the reduction of the building mass throughout the length of the tower

The ground floor is reactivated with low rise retails structures. The low rise additions do not interfere with the new clear sight lines, keeping great transparency from all ends of the site

A ribbon structure is added playing the double role of visually connecting the new sky stops to the existing structure of the tower, also creating a track forthr circulation system to attach to

The vertical circulation system is attached to the new ribbon that allows for travel in all directions. The pods are large gyroscopes keeping the passenger compartment upright at all times

The core is reactivated via a DAC capture system. Filters are place inside the cire capturing carbon, and releasing fresh clean oxygen into the atmosphere

To aid the carbon capture, two strategically placed fans draw air into the existing core.

The introduction of the fan echoes the design language of the old crown of the building, while hinting at the sustainable technology that is present

The environs encircling the skystop are now amenable for public enjoyment, with the carbon capture systems fans now readily accessible. These fans serve a dual purpose, acting as both bustling transportation hubs for bus patrons and convivial gathering spots for the diverse cohort of occupants frequenting the buildings, including denizens, professionals, and sojourners. As a result of the highly versatile nature of the buildings program, the space and overarching concept are profoundly pliant, capable of adapting to a wide range of needs and preferences.

We recognize the importance of preserving the existing structure of the US bank tower, as it has become a symbol of LA. However, we rethought what it meant for a building to be mixed-use. We did away with the old Euclidean programming of the past and embraced the new mixed-use programming of the future, with the aim of creating a tower able to cater to all aspects of daily life and promoting a strong sense of community.

Program Distribution Chunk

Carbon Capture

The utilization of the existing core for the reactivation of the carbon capture system is a remarkable feat of engineering. Fans artfully designed to channel air from the atmosphere through a series of filters and chambers propel this process forward, culminating in a release at the tower’s base that offers heating or cooling benefits to those occupying the ground floor market area. Moreover, the DAC system is an integral component of the tower’s structure, as it is affixed and adhered to the preexisting core. The fans themselves are an exceptional architectural feature, with the topmost fan evoking a sense of the tower’s historical significance while simultaneously alluding to the cutting-edge sustainable technology employed within its walls.

A

the new

Mohamad

Mohamad

Mohamad AlSharif

Southern California Institute of Architecture

Mohamad AlSharif

Southern California Institute of Architecture

A view showcasing the various intergrated sky stops that form a flexible seamless network of public transportation in the sky.

Mohamad AlSharif

Southern California Institute of Architecture

Mohamad AlSharif

Southern California Institute of Architecture

An axonometric view showcasing the overall form of the tower. While the overall silhouette remain simple. The intricay lies in the details of the design of the core, and the facade.

Mohamad AlSharif Southern California Institute of Architecture

Mohamad AlSharif Southern California Institute of Architecture

Mohamad

Mohamad

NEOTran

Damjan JovanovicOur short film was centered on the notion of futuristic transportation, where we delved into the possibilities and implications of innovative modes of transportation. We began by conducting extensive research during our studio projects, which culminated in the creation of self-levitating systems that could transform the way we travel. Our proposed transportation devices were the result of this research, and we explored the possibilities of what the future of transportation could look like.

The transportation devices we proposed were designed to be highly interconnected with infrastructure and buildings, with the building itself serving as part of the infrastructure. These transportation systems are capable of docking or entering buildings to pick up and drop off passengers. In doing so, they provide greater flexibility in choosing routes and destinations.

Our vision for the future of transportation goes beyond just the means of getting from point A to point B. We imagined that future transportation systems would be designed to provide a unique and enjoyable journey, with various activities onboard. We took inspiration from existing cruise ships, where passengers can partake in activities and enjoy amenities onboard, making the journey just as desirable as the destination.

In summary, our short film showcased the possibilities of what the future of transportation could look like. Our vision includes self-levitating technology, highly interconnected infrastructure, and transportation devices that provide a unique and enjoyable journey for passengers.

Mohamad AlSharif

Southern California Institute of Architecture

Mohamad AlSharif

Southern California Institute of Architecture

The train arriving at the train stop

Mohamad AlSharif Southern California Institute of Architecture

The train arriving at the train stop

Mohamad AlSharif Southern California Institute of Architecture

A view showcasing the train of the future leaving the trainstop

Mohamad AlSharif Southern California Institute of Architecture

A view showcasing the train of the future leaving the trainstop

Mohamad AlSharif Southern California Institute of Architecture

A sectional drawing showing the various programtic aspects of the bus of the future,

Mohamad AlSharif

Southern California Institue of Architecture

Mohamad AlSharif

Southern California Institue of Architecture

future, showcasing how the journey can be just as important as the destination

8484 Wilshire

In collaboration with Raunak Chaudhary, and Hanyang Yan

We were prompted to contemplate the integration of advanced building systems into modern architectural projects. Rather than accepting the traditional standpoint, which may be considered a legacy of 20th-century modernist and state-supported capitalist agendas, we were encouraged to reframe what was deemed “advanced” in light of global resource scarcity, climate change, political instability, and income inequality, all of which impacted the commercial strip in Los Angeles.

Using Ed Ruscha’s iconic photographic artwork, “Every Building on the Sunset Strip,” we analyzed the greenhouse gas emissions and climate impact associated with the Sunset Strip. This served as a basis for decarbonizing the built environment in Los Angeles.

Russel Fortmeyer

Throughout the course, we delved into the key topics of building technology, such as building envelopes, acoustical environments, mechanical, electrical, lighting, plumbing, fire/life safety, controls and security, and vertical transportation. These were explored as signs of the failure of the fundamental and passive basis of architecture to find expression. To find solutions, we adopted new analytical and modeling approaches that prioritized progressive design that reinstated the core values of architecture for people and our planet’s limits.

As we progressed through the class, we learned alternative approaches to technical documentation and economic models that served as the underlying framework for the architectural project. The course included lectures, exams, and readings, as well as a group project that centered around an inclusive and expanded notion of the Sunset Strip.

Mohamad AlSharif

Southern California Institute of Architecture

Mohamad AlSharif

Southern California Institute of Architecture

Facts & Figures

Great Western Financial Bank 8484 Wilshire Blvd, Beverly Hills, CA 90211

Project size: 68580 m2 (225,000 ft2) 10 Stories

Architect: William L. Pereira & Associates

Owner: Douglas Emmett

Year Built: 1972

Program: Office Rental

Occupancy: Low density office space - 4 floors empty

Hours of Operation: 7:30am till 10pm

We conducted a comprehensive series of sun studies to establish benchmarks for our design interventions. We analyzed the sun angles during the longest day of the year, as well as the shortest day of the year, to gain a holistic understanding of the solar orientation of the building. The insights gleaned from these studies were crucial in informing our decision-making process as we designed the double skin façade.

We then conducted a thorough analysis of the existing building’s massing to determine the optimal approach for utilizing the sun’s exposure and shading. We found that the shape of the building was well-suited for maximizing solar gain while also providing adequate shading

Presented here is an axonometric view of the building following the completion of all the proposed interventions. The entire structure has been thoughtfully reimagined with the dual objectives of enhancing the building's sustainability quotient while simultaneously optimizing the comfort levels for its occupants.

Mohamad AlSharif Southern California Institute of Architecture

Mohamad AlSharif Southern California Institute of Architecture

Existing Condition

This report offers an in-depth analysis of the environmental operation of the building. Specifically, this section sheds light on the deficiencies of the current façade, and the associated impacts it imposes on its users. Our team was tasked with devising three distinct scenarios to serve as benchmarks or reference points, ensuring the proposed interventions align with the anticipated performance outcomes. It was postulated that the tower would be used for mixed purposes in the future, as evidenced by the diverse scenarios we developed to illustrate the array of potential lifestyles that could be accommodated within the building.

Solar heat gain may affect office workers that are working near the glazing. Non operable windows prevent users for taking climate action into their own hands

The break room is meant for employees and others to relax. Potential noise pollution from the surrounding street is possible. Regulating uniform light penetration is essential in maintaining healthy circadian rhythms

Activity intensive room, with loads of people could potentially overwhelm the exisiting comfort system of the room, which is currently of an HVAC system that was installed during the latest renvovation of the building which took place in 1985, around 15 years after the building was first built

Existing Section

Post-Intervention Condition

Mounted Solar Panels

energy, which can also support the mechanical units

AHU (Air Handling Unit)

An AHU (Air Handling Unit) is an essential component of HVAC systems in buildings, and its primary function is to circulate and condition air. It draws in outside or recirculated air, filters it, and heats or cools it to maintain a comfortable indoor temperature. AHUs also control humidity, ventilation, and air quality to ensure a healthy and comfortable indoor environment.

A Cassette Split AC is a type of air conditioning unit that is installed in the ceiling of a room. Its primary function is to cool or heat the air in the room by drawing in hot or cold air and passing it through refrigerant coils. The cooled or heated air is then blown back into the room through four sides of the cassette unit, providing even and efficient air distribution.

Double Curtain Wall System

Double Curtain Wall System walls can improve building ventilation by allowing natural airflow, controlling solar radiation, and providing precise control over the flow of air. These features can help to improve indoor air quality, reduce energy consumption, and enhance occupant comfort.

Indoor Plants

Indoor plants can help regulate temperature, improve air quality, control humidity, provide psychological benefits, and enhance the overall appearance of a building.

Cassette Split AC Floor split System

The Floor Split System is a type of air conditioning system that uses a small indoor unit and a larger outdoor unit to cool or heat a room. The indoor unit is installed in the ceiling or floor, and it blows cool or warm air into the room through vents. The outdoor unit contains a compressor and a heat exchanger, which work together to cool or heat the refrigerant and circulate it between the indoor and outdoor units.

Passive Ventialtion Strategies

Interior Courtyard

One of the key interventions that we introduced was the concept of an interior courtyard, which served a dual purpose. Firstly, it provided an inviting congregational space for the building’s occupants to congregate, interact and collaborate. Secondly, the atrium created an awe-inspiring entrance for pedestrians, providing them with a sense of grandeur as they entered the building. Significantly, the atrium also forms a crucial component of our ventilation strategy, allowing fresh air to flow in from the double skin façade and circulate throughout the building. Finally, the ventilation system culminates at the top of the atrium, where a remotely actuated skylight facilitates the exit of stale air, completing the cycle of fresh air circulation.

Open Interior Stair

The introduction of the open stairs behind the atrium serves a similar purpose to the courtyard, and it is noteworthy that these interventions have been designed without compromising the integrity of the building’s existing structural system. The openings in the floor slab have been strategically placed to avoid interfering with the beams, instead being situated in the spaces between them. Additionally, the incorporation of lush greenery around the atriums confers numerous mental health benefits to occupants while simultaneously filtering out pollutants, including harmful carbon particles emanating from the adjacent roads.

Water Managment

Water management capture system

Opportunities for reusing, recycling grey water, and harvesting rainwater

The roofs of the building present unique opportunities for harvesting rainwater, which can be pumped down to the cistern in the basement to filter and recycle the water to be used later on in the building

A wastewater system will allows the building to take wastewater, to be pumped to the basement, where a filtration take is placed in order for the water to be filtered, and then pumped back into all of the faucets etc

The rain garden is zone that can be intentionally design to be flooded which can allow certain water intake when necessary, but can also alleviate from flooding when the water management system of the city is overwhelmed

Water Managment Section

Lighting Design

We devised an innovative lighting system that is tailored to cater to individuals across multiple time zones. The system is carefully calibrated to deliver cooler, blue-enriched light during the daytime hours to promote alertness, productivity, and concentration. As evening approaches, the lighting gradually transitions to warmer, low-intensity hues, which facilitate relaxation, rest, and recovery, enhancing sleep quality. Crucially, this dynamic lighting system plays a pivotal role in regulating healthy circadian rhythms, which have been proven to be crucial for overall wellbeing. This innovative approach to lighting design emphasizes the importance of the natural rhythm of light and its effects on our bodies, promoting optimal health and productivity for all occupants of the building.

Types of lighting systems designed

1. Recessed cove fixture/ uplight

2. Ceiling adjustable cove light

3. Direct pendant work light

4. Ambient reading task reading light

5. Low level recessed LED strip skirting floor wash

As part of our lighting design strategy, we have carefully considered the placement of each light source, taking into account the light fall-off properties of each fixture. Lights with intense fall-off properties are placed below eye level, while recessed fixtures are positioned overhead to create a serene ambiance throughout the space. Furthermore, while the addition of lighting fixtures is a crucial element in any design plan, we have ensured that their usage hours are minimized through the implementation of our double skin façade system. The new façade replaces the outdated, heavily-tinted glass with modern, transparent glass that maximizes the amount of natural light entering the building, reducing the dependence on artificial lighting. As a result, the need for electric lighting will be significantly reduced, contributing to the overall energy efficiency of the building

Lighting Design Section

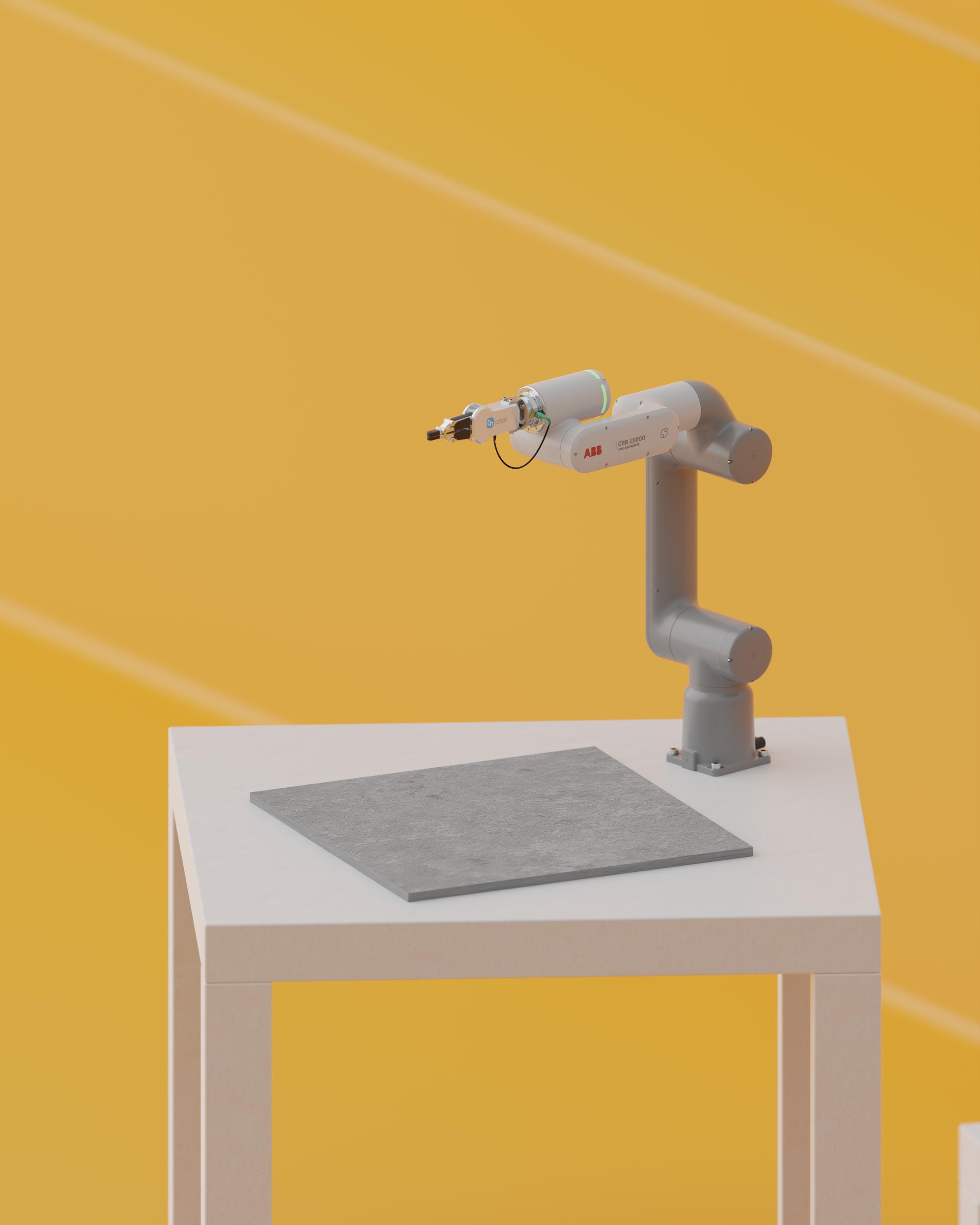

Models & Design Agency

Marcelyn GowModeling in architecture, both analog and digital is incredibly fundamental to the profession in the same way that tomatoes are fundamental to contemporary Italian cuisine. In other words, one cannot exist without the other. Modeling, a process that has been around for decades, has undergone, and continues to experience massive developments throughout the history of the profession. Nonetheless, it is due to these developments that the profession can operate in today’s world. In today’s age, the traditional workflow of using models is ever changing. The aim of this paper is to question the validity of using the model, whether it be physical or digital as a design tool in today’s age, and to explore what is the best workflow for models, in a rapidly changing technologically driven workflow?

To begin with, it is important to understand how the physical model has come to be such a systematic step in the architectural workflow. Since, the architectural physical model has played a role in shaping architectural thinking. In traditional terms the physical model is used as a design tool to better help designers visually understand the implications of the architecture in the built environment, as well as the overall massing of the building. It gave an almost God like power dynamic to the architects, due to the scale implications of a scale model. It gave power to the architects in the form of an illusion, since it narrowed the perception of the sheer mass of buildings, downplaying its effects in urban settings. During the renaissance period designers used physical models to resolve some of the complicated structures at the time, such as the likes of Antonio Gaudi, and Brunelleschi, during the construction of the Sagrada Familia, and the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore respectively (Figure 1). However, the contemporary use of the physical model has transcended structure and is now primarily used as design development tool.

The rise of the physical model in the contemporary American architecture scene can be credited in part to William Alciphron Boring1 . Boring, who served as the dean of Columbia’s school of architecture in 1930’s argued that physical model making was to become the main vessel of exploration of architectural concepts at Columbia. Furthermore, he pushed for the notion “from the point of view of the constructed building” rather than “the point of view of the picture”2 . Boring here is referring to the image like representations that drawings possessed at the time. Boring also alludes

to the composite realities that images can sometimes portray. Boring believed that drawings were simulated environments that were being conjured by architects, as they were a simple glimpse of a building often not highlighting the full story of the project3 He argued that models would allow architects to bypass the composite realities, which occurred when creating a drawing or image. Ever since then the physical model has been cemented as a key part in the architectural process.

The introduction of digital model making in the early 1980’s allowed for many of the great architectural masterpieces of contemporary architecture to exist. It allowed for the rationalization of extreme complex forms, tectonics, and geometry that physical model making could never replicate, much was the same with drawings (Figure 2). 3D digital models were able to condense large amounts of data into one model, which made it much easier for designers to better understand complex geometry, and then translate that same information to builders for the building to be built. Moreover in some cases drawings could explain the complex geometry, however it simply took too long. Drawings could only convey so much, however at some point 2D drawings were not a sufficient medium for translating extremely complex geometries.

Physical Models are a great and efficient way of quickly visualizing, and testing ideas. They also are great due to their low skill barrier of entry since there is almost no learning curve to conquer. Moreover, Physical models convey ideas clearly to designers, and non-designers alike. However, the current issue with the use of the physical model is that they create false senses of composite realities4 . Physical models due to their scale implications are almost always dwarfed in the hands of an architect. Therefore, architects are almost dropped into this God-like power dynamic, which allow architects to design in a headspace that is far from reality. It is much like Jesus Vallos’ “Seamless: Digital Collage and Dirty Realism in Architecture”, where he explores the history of the intertwined nature of photography and architecture. Vallos argues that while initially photography in architecture was used as a documentational tool to keep track of highly complex, and important details, that did not remain the case5. As architecture slowly began to become an industry that had to “engage in the business of making images”6 a false reality in the architecture began to present itself through photography. This effect was in part due to the nature of the photograph, which is simple terms is a snapshot of a moment in time, forever frozen. Vallos argues that designers began to employ photography in ways to dictate a certain narrative that wasn’t necessarily true. The same flaw is present in the process of creating physical models, the scale of physical models is the origin of the situation. Physical models suffer from the same issue since models provide a singular view onto a project, a view that is often unrealistic and farfetched from reality. A view that often causes designers to neglect one of the core principles of architecture, which is to consider the human to building interaction, and vice versa.

The introduction of the digital model seemingly solves the issue of the scale, that is present in the physical model. The 3D digital model solves the issue of scale by having the ability to scale in accordance with the desire of the architect. The digital model provides an inherent flexibility that the physical model could never replicate. However, the issue of the digital model is that it a model that is not rooted in reality7. There is an element of disconnectedness when viewing a 3D digital model,

since buildings are ultimately a physical object with a real fixed scale, with material properties that are appropriate to that building scale. While pointing out the flaws in both physical, and digital models may seem like an act of questioning their validity in the architectural process, that is not the intended goal, but rather the goal is to reframe and reconsider what the future roles of models are in the architectural process.

This is the focus of David Eskenazi’s work. Eskenazi explores the relationships of both the physical and digital models to each of their own inherent scalar qualities in his piece “Tired and Behaving Poorly”. He argues that an amalgamation of both physical and digital models is the key to moving forward (Figure 3). In essence, he merges the positive qualities of both models in order to create an ideal model, that is both rooted in the physics of reality, and scalable. The result is a model that is rather honest regarding its form, and material use, and hands a great deal of design agency to its material properties. This agency of the material allows an architectural project that has a novel piece of humanity, since the building is almost able to ‘feel’ the forces at play and is responding to those forces. Eskenazi, then reframes the role of the model in the architectural workflow. The model becomes less of a transitionary piece of design, but rather the product8. Therefore, the model is the final building. The physical model is then not just a design tool, but more so a product that is representative of the structural, material, and tectonic nature of the building to be built.

Eskenazi’s workflow bypasses all the inherent issues of the physical and digital models. The amalgamated model workflow does not allow architects to fall into the God-like power dynamic, since there is a system of balance, due to the model’s innate design agency. Moreover, the amalgamated model does not suffer from the digital model’s scale disconnect, due to the embedded physical parameters imposed onto the digital model. Michelle Jaja Chang’s work is much the same, which was visible in her exhibition “Scoring, Buildings”, where much like Eskenazi, Chang challenges the use of the model as the final outcome, rather than as a design development tool. She does this by challenging convention of modeling, and the following representation that led to a final building outcome. Usually, builders are given highly specific construction documents that are used to execute the designer’s clear vision allowing for little to no design agency. However, Chang challenges this by providing builders with a set of instructions, and notations which are not entirely precise, and are based off music notation, the score of a song. In a sense, Chang provides advice, not a guide to builders. The outcome, not unlike Eskenazi’s, is an incredibly honest architectural project since the designer is not the sole contributor to the design. In the case of Chang, it is the score of music, and the builder having some design agency.

Essentially a new architectural workflow is being developed around an amalgamated model which hands over some design agency to someone, or something other than the designer. The result is a project that doesn’t suffer from either the drawbacks of physical or digital models. Therefore, cementing the idea of collaboration in architectural pedagogy and practice. This amalgamated model then moves the model in architectural workflow from transitionary design tool to the end product. The model is then the building to be built.

Bilbiography

“Anna Neimark: Rude Forms among Us - Sci-Arc.” SCI, https://www.sciarc.edu/events/exhibitions/anna-neimark-rude-forms-among-us.

“Anna Neimark: Rude Forms Among Us.” YouTube, YouTube, 18 June 2020, https://www. youtube.com/watch?v=QCN2BS75prY. Accessed 16 Feb. 2023.

Astbury, Jon. “Architects Do It with Models: The History of Architecture in 16 Models.” Architectural Review, 21 July 2020, https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/architects-do-it-with-models-the-history-of-architecture-in-16-models.

AuthorAvneeth Premarajan Avneeth Premarajan is a practicing Architect and an ardent “student” of Architecture. He is intrigued by concepts, et al. “Is Architectural Model Making a Dying Art? Is Architectural Model Making a Dying Art?” RTF | Rethinking The Future, 19 Aug. 2021, https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/architectural-community/ a4925-is-architectural-model-making-a-dying-art/.

Ben Dreith |16 November 2022 Leave a comment. “How Ai Software Will Change Architecture and Design.” Dezeen, 5 Dec. 2022, https://www.dezeen.com/2022/11/16/ai-design-architecture-product/.

“Duel + Duet: David Eskenazi & Alexey Marfin (July 22, 2022).” YouTube, YouTube, 23 Aug. 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SeXmtfHBDJY. Accessed 16 Feb. 2023.

Frampton, Kenneth, et al. Modeling History. Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2017.

Fraser, Andrea. “Procedural Matters: The Art of Michael Asher.” The Online Edition of Artforum International Magazine, 1 June 2008, https://www.artforum.com/print/200806/ procedural-matters-the-art-of-michael-asher-20388.

Lavin, Sylvia. “Vanishing Point: The Contemporary Pavilion.” The Online Edition of Artforum International Magazine, 1 Oct. 2012, https://www.artforum.com/print/201208/vanishing-point-the-contemporary-pavilion-34519.

“McNeel Wiki.” The History of Rhino [McNeel Wiki], https://wiki.mcneel.com/rhino/rhinohistory#:~:text=Oct%201998%20%2D%20Rhino%20version%201.0,Dec%201998%20 %2D%20First%205%2C000%20shipped.&text=Jan%201999%20%2D%20 First%20public%20beta%20of%201.1%20released.

“SoA 50th Anniversary Lecture Series: Michelle Chang.” YouTube, YouTube, 15 Nov. 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z8Nt6cY3W44. Accessed 16 Feb. 2023.

TheB1MLtd, director. Building the World's Last Megatall Skyscraper. YouTube, YouTube, 24 Feb. 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pnRscqkN3vw. Accessed 16 Feb. 2023.

“Tony Smith: Smoke.” LACMA, https://www.lacma.org/art/exhibition/tony-smith-smoke.

“The Weitzman School of Design Presents: Ellie Abrons.” YouTube, YouTube, 14 Jan. 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GYXenh9i0D0. Accessed 16 Feb. 2023.

Wetzler, Rachel. “Making Space: Katarzyna Kobro.” ARTnews.com, ARTnews.com, 12 Sept. 2022, https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/features/katarzyna-kobro-spatial-sculpture-1234639122/.

“Who Invented the Skyscraper?” Skydeck Chicago, 1 Feb. 2021, https://theskydeck.com/ who-invented-the-skyscraper/#:~:text=Local%20architect%2C%20William%20LeBaron%20Jenney,the%20first%20skyscraper%20in%201884.

An Abundant Life

John CooperAaron Bastani’s “Fully Automated Luxury Communism” (FALC), is a socioeconomic and political concept that envisions a future where technology and automation have eliminated the need for human labor, therefore creating a postscarcity society where everyone can enjoy a life of abundance and leisure. Under FALC, the means of production would be publicly owned, and goods and services would be distributed fairly among all members of society. FALC also aims to address environmental challenges and promote sustainable living by advocating for renewable energy, green technology, and a circular economy. This concept has gained attention in recent years as a potential solution to address the increasing wealth gap, social inequality, and the potential displacement of jobs caused by automation. This article will focus on the subject matter of abundance, and the role it plays in society, and what effects it could have on architectural thinking and design.

The topic of abundance is incredibly relevant, as architectural practice today operates in response to climate change, in the opposite way. Architectural practice today is all about limiting the consumption of a building in all forms, whether it be carbon footprint, or solar heat gain. According to Bastani, FALC is not if, but rather a when kind of situation, meaning at some point humanity will reach a point in which it is considered abundant in resources, in which point architecture will need to navigate itself in a new kind of world.

“Fully Automated Luxury Communism” is a thought-provoking book, since it challenges our archaic notions of how the future is impacted by technology. The future is often depicted as a dystopian mess, that is somehow a byproduct of some technological conglomerate that has monopolized the world. However, in FALC Bastani makes a bold prediction regarding the future where technological advancements have eliminated the need for human labor, resulting in a post-scarcity society where everyone can enjoy a life of abundance and leisure. It envisions a world where robots and automation have taken over most jobs, freeing up time for individuals to pursue creative and intellectual pursuits. Under FALC, the means of production would be publicly owned, and goods and services would be distributed fairly among all members of society. Moreover, FALC predicts that this future would be achieved through green technology and renewable energy sources, leading to a sustainable, zero-carbon

economy. The book argues that technological progress has the potential to address social inequality, wealth gap, and environmental challenges, and that a socialist approach to production and distribution would enable society to benefit from these advancements. Bastani mainly argues that the future is dependent on FALC, due to 3 main crises’ which are going to be instrumental in moving the world towards a future of post-scarcity. The first of the 3 crisis’s is the “breakdown and collapse of the current economic model”1 , which is currently a financialized international form of capitalism, which has been in decline since 2008 post the global financial crisis. The second crisis which Bastani addresses is the ecological crisis. Next, is the ongoing health care crisis, and more specifically Bastani argues that the current situation is up in the air, and that at this very moment is an unprecedented moment in human history. It is then due to these crises that a disruption is needed to usher in a new way of life for humanity. In recent history according to Bastani, mankind has had two breakthroughs that brought about the modern way of life. “The first disruption took place around twelve thousand years ago as our ancestors transitioned from nomadic hunting and gathering to a life of settled agriculture”2 . The domestication of animals and land allowed for humans to become less transient, soon enough cities began to spring up, and from those, countries of unique culture, and economies rose to exist. The first disruption laid out the foundations, as it concentrated human growth and ingenuity into a consolidated effort.

The second disruption that changed the way humans lived was much more recent, the industrial revolution, which made leaps and bounds in the way energy was created and harvested. The industrial revolution therefore allowed for mass production of many things, which then logically, further intensified population, and urban growth exponentially. Finally, he predicts that the third disruption is when humanity is able to create an abundance of resources, which will come in the same way it did during the second disruption. In essence the third disruption is coming, however what happens to architectural thinking and design when it does arrive?

Assuming that in the future, humanity has solved the issue of energy meaning there is a surplus of energy, to the point where all of humanities yearly needs are being satisfied by 90 mins of solar radiation being captured3 . Assuming that, sustainable farming practices have created a massive surplus of food, allowing every person on earth to consume over 4000 calories a day. Assuming that automation has absolved humans from working hard laborious jobs. Assuming that advances in technology will allow humans to live longer healthier lives. How, and in what way does architecture respond in such a world?

While FALC does not exist in the current world, it is perhaps best to look at current, and past societies that have come close or have ventured through large sums of time, in which a surplus of resources, and abundance did in fact exist. The ancient Egyptian civilization was in fact one form of society that at a time was in abundance of a multitude of things, including but not limited to labor, power, agriculture, and resources. The existence of the magnificent architectural wonders of ancient Egypt owe their existence to this level of abundance, and prosperous time. The ancient Egyptians were able to create architectural marvels that are still a mystery to this day. Not only were they architecturally interesting and complex, but it is still a mystery how

they managed to build such structures so accurately. The aforementioned structures are the pyramids and sphinx, which stand to this day unexplained, bewildering tourists every day.

Perhaps a more contemporary project to consider, that owes its existence to a society that is prosperous enough to be called abundant in resources, is NEOM’s the Line. The Line is, as the name suggests, a linear city, that is 170 kilometers long, 200 meters wide and 500 meters tall. The Line is marketed as a leap in the way humans live and work. A disruption that claims to consolidate a city’s footprint in just 34 km2. The aim of the project is to create a project that is wildly sustainable, and convenient as breakthroughs in AI will allow users of the project to get from one end of the project to another in just 20 minutes of travel. The line is one of many projects that full under the umbrella of NEOM, which is a mega project being funded by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, a nation that has been and is currently being fueled by massive oil reserves. The kingdom is as close an abundance nation one could get in modern times, meaning that the Line is product of an abundance of wealth, and resources. It can then be argued that the line is a precedent for what the future of architectural thinking and design could look like, when societies transition into fully automated luxury communisms.

The line is a current representation of FALC. The line features an ambiguous almost program free interior, as in programs are very loosely defined, and are easily swapped with one another. Therefore, it is not difficult to imagine the kind of lifestyle that the architecture is hinting at. The architecture of the line hints at a lifestyle that is of abundance, and pure leisure. This idea is further reinforced by the fact that almost all services within the Line are automated, by advances in AI, further freeing individuals from the burdens of working labor-intensive jobs, much like Bastani described in his book. Furthermore, the line is ultimately a large sustainable project, its form is derived in order to take up the least amount of space, so is its façade and roof treatment. The roof is used as a large solar farm, as well as a green roof that is capable of growing crops, which then creates a closed system loop that is self-sufficient from any outside source of food, or power. Further aligning itself with Basatni’s vision of a FALC society is the line’s ability to naturally ventilate and control its ambient temperature within the building. Since the building is a 170 km long skyscraper, it has the unique ability to use stack ventilation along it entire span, creating a very sustainable project. Interestingly the line is often seen as a dystopian project in the eyes of many designers and architects. An architectural mess amidst the Arabian desert, on the other hand, Bastani’s book FALC is often regarded as a utopian representation of the future. However, the line is simply a current representation of what a post scarcity society would build in the future. The line is almost exactly what Bastani describes in his book. There is no doubt that the line may not be an exact match, since at the end of the day, the kingdom is not yet a fully FALC society, which causes some discrepancies to arise. Nevertheless, the line present as close a representation could get in the current time.

When analyzing the line, it is important to recognize that it is a product of economic abundance, not design abundance. While the Line is incredibly innovative in its thinking and pushes the boundaries of what an urban space could, and should

look like, it is not an abundance of thinking or analysis. Ultimately, a FALC society’s advantage is that since universal basis services are free for all to sue, individuals are more likely to participate in creative fields, such as graphic design, art, and most importantly architecture. As a result, innovation in architecture will be prevalent, and much sooner due to the large shifts of individuals taking architecture as hobby, or career. FALC is a wave that will fundamentally change the way architecture is conceived in the future. A fundamental shift in the way individuals are going to interact with space, and what even constitutes space in the future. An architectural future in which space is no longer defined by the program, the client, the budget, but rather the self-expression of the community behind it. FALC grants architecture the opportunity to move away from the banal aspects of the field today. Architecture will still need to exist to serve a fundamental purpose, however in a communistic post scarce society, the architecture will no longer be bound by the amount of heat gain is allowed to penetrate through a window on a Sunday afternoon at some time of the year for example. Architecture in FLAC will be critiqued and built in order to self-express the feelings of designers in which the idea of the project was born. Therefore, the architecture of the future marks a point in history where architecture will become an anti-formalistic endeavor lacking any foreseeable boundaries. One could imagine that in a post-scarce society the normality of the building will no longer be a formal one but rather, an urban fabric made up of unique forms, all creating artful expressions.

Moreover, the emergence of FALC heralds a significant shift in the way architects and designers approach their work. Traditionally, architectural thinking takes place at the top of a hierarchical pyramid, with ideas trickling down the chain of command and dwindling in intensity with each subsequent layer. This creates a monarchy of design, in which the lead architect reigns supreme and imposes their vision on the landscape like a god-like figure.

FALC upends this archaic model by empowering collaborative and participatory design processes, breaking down the hierarchical barriers that have long constrained the architectural field. By enabling positive design by committee, FALC facilitates a fundamental rethinking of architectural thinking, allowing for a more democratic and equitable approach to the built environment. This transformative shift represents a remarkable opportunity to create more inclusive and sustainable spaces that reflect the needs and aspirations of all members of society. This reapproach to the architectural workflow allows for better design to take place, and ultimately allows for the creation of better, more viable, and productive spaces for individuals of the future to inhabit.

In essence, the theory of abundance is incredibly powerful and moving in an architectural sense. However, no society or civilization in human history has reached a level to explore it. Many have come close, as mentioned above, and have shown the benefits of how a post scarce society can further enhance the quality of innovation brought forward, architecturally. Abundance, and a post scarce society, are the next disruption that is needed to usher in a new wave of architectural thinking and design, as it did for various other industries. More specifically it is the combination of abundance of wealth and thinking that will push architecture into new realms of thinking and design.

Bilbiography

BASTANI, AARON. Fully Automated Luxury: A Manifesto. VERSO, 2020. Bookchin, Murray. Post-Scarcity Anarchism. AK Press, 2018.

The institute of Art & Ideas, director. Aaron Bastani | On Fully Automated Luxury Communism, Climate Change, and More. YouTube, YouTube, 22 Dec. 2019, https://www. youtube.com/watch?v=YT6xiMUSPm8. Accessed 22 Apr. 2023.

The Institute of Art & Ideas, director. Fully Automated Luxury Communism | Aaron Bastani. YouTube, YouTube, 6 Mar. 2020, https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=u2MSstaWgH0. Accessed 22 Apr. 2023.

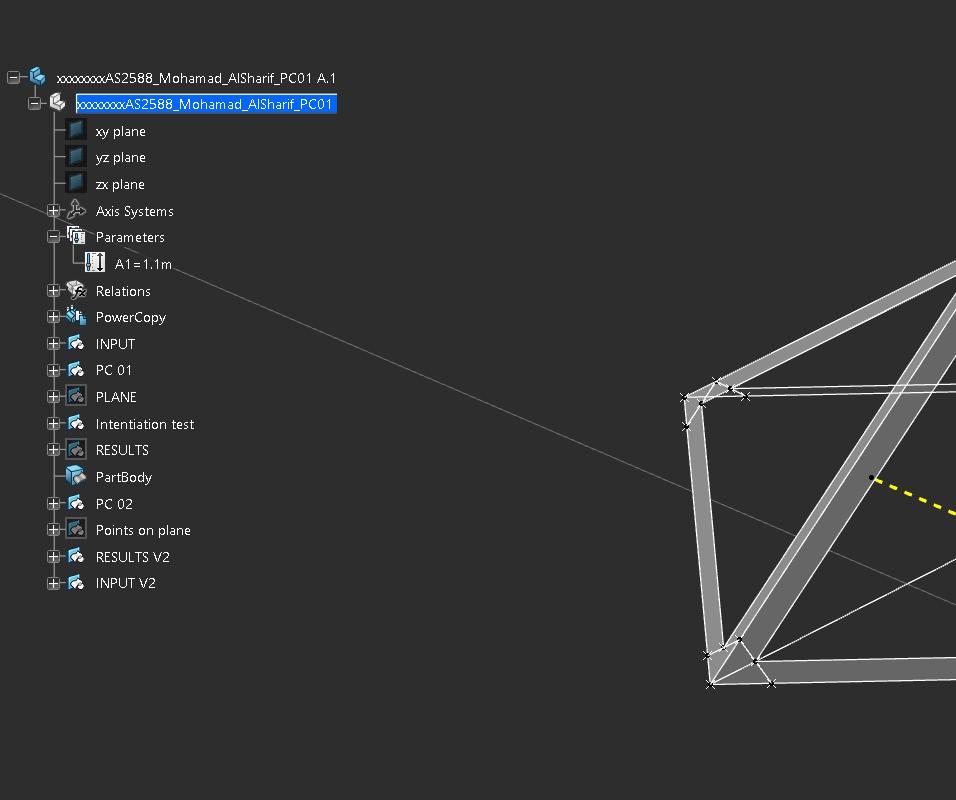

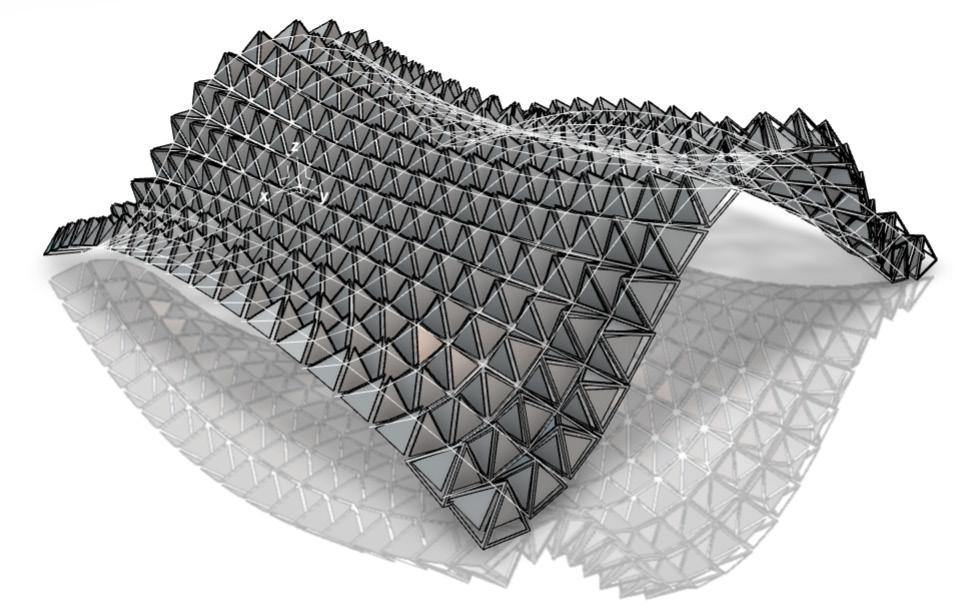

Fractal S, M, L, XL

Kerenza HarrisThe core concept that drove our work in CATIA revolved around the intricate beauty of fractals. We were fascinated by the idea of starting with a small fractal and scaling it up to integrate it into a larger system while still maintaining its individual functionality. To achieve this, we used the power copy feature to create a squarebased pyramid with triangular windows on four sides, which was parametrically controlled to ensure flexibility in scaling. We then repeated this fractal onto the surface using XGEN to create infill panels for each instance. The end result was a stunning and

adaptable free-standing structure that could function as a standalone pavilion or as part of a larger system such as an airport terminal roof. Our approach allowed for a high level of programmatic flexibility and ensured the structure’s relevance in an ever-changing world, making it a true embodiment of the beauty and practicality of fractals.

Power Copy Building

The parameter A1 is linked to the translated MidPoint, meaning whenever the parameter is adjsuted the entire Powercopy height is affected

Mohamad

Mohamad

Attractor Point

After Instantiating, an attractor point was added to the power copy to control the height parameter of the powercopy. The further the powercopy is from the attractor point, the greater the height

Mohamad AlSharif Southern California Institute of Architecture

Mohamad AlSharif Southern California Institute of Architecture

Drawings

Elevation

The final panelization attempt started by creating a new double curved surface that was vaulted in form. The surface was then UV mapped and divided into planes. A line was extened upwards in the normal direction. lines linked the base of the plane to the the new normal line, which then created pyramids, which were then offsetted inwards to create seperate islands of triangles, which were then used in the final shelter assignment

Mohamad

Mohamad

Mohamad AlSharif

Southern California Institue of Architecture

Mohamad AlSharif

Southern California Institue of Architecture

Space Army

Rachael MccallThe Aim of IDD was to bring all students to a baselevel of understanding to softwares that would be used later after the semester has begun. The softwares used during IDD were mainly cinema 4D, and Zbrush. Cinema 4D was used as a design tool, as well as visualisation tool. The first step was to create a character in C4D by using the volume builder to create a character. Zbrush was then used to scuplt particular details on the character