S M R

Singapore Metropolitan Region

Erik G. L’Heureux, ed.

Chua Gong Yao

Koh Ai Ting Aileen

Yap Shan Ming

with essays by: Freek Colombijn

Lai Chee Kien

Chua Beng Huat

Tim Bunnell

François Decoster

This book was published on the occasion of the completion of ‘Singapore Metropolitan Region’ studio Singapore, September 2011 – May 2012

Published by Centre for Advanced Studies in Architecture National University of Singapore

4 Architecture Drive, Singapore 117566.

T: +65.6516.3477

Email: akierik@nus.edu.sg

Website: www.smsstudio.org

© 2013 Centre for Advanced Studies in Architecture

National University of Singapore

© 2013 Individual Contributors

Advisor and Editor

Erik G. L’Heureux, AIA, LEED AP BD+C

SMR Studio

Chua Gong Yao

Koh Ai Ting Aileen Yap Shan Ming

The author and publisher gratefully acknowledge the permission granted to reproduce the copyright material in this book. Every effort has been made to trace and identify copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright materials. The author apologizes for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior written permission of the publisher.

The publisher does not warrant or assume any legal responsibility for the publication’s contents.

All opinions expressed in the book are of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National University of Singapore.

Contents

PROLOGUE

Singapore Centricity – Erik G. L’Heureux

1-12

JOHOR + SINGAPORE + BATAM

Chicks and Chicken: Singapore’s Expansion to Riau – Freek Colombijn Axis Mappings

14-150

SINGAPORE METROPOLITAN REGION

Filtered Cosmopolitanism and Southeast Asia – Lai Chee Kien

The Peripheral Corridor

152-244

THE SAME-SAME MODEL

Exporting Urban Uniformity Worldwide – Chua Beng Huat & Tim Bunnell

Exporting Urban Uniformity

246-280

DENCITY

Density in Singapore – François Decoster

Investigating Density Formula

282-330

REGIONAL PROPOSITIONS

332-384

BIBLIOGRAPHY

386-398

ISBN 978–981–07–2633–1

1st Edition

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS & CREDITS

399-402

Prologue

SINGAPORE CENTRICITY

Erik G. L’Heureux, AIA LEED AP BD+C, Ed Assistant Professor Department of Architecture National University of Singapore

In Southeast Asia, where urbanization proceeds at a quickening pace and with seeming inevitability, Singapore has become one of the most visible and successful models for the developing world. The changes that have taken place in Singapore over the last four decades represent the aspirations of other governments, policy makers, planners and architects looking to join the club of the “Developed”, “First World” and “Modern”. As outlined in From Third World to First: The Singapore Story: 1965-2000 by former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, 1 the dynamic changes that have transformed Singapore from the mythic collection of rural villages to a modern urban city, from poverty to wealth, and from kampong to modern city-state continue to inspire countless cities on their quest for development. 2 As retold continually in the popular press, academic journals and numerous policy papers, Singapore’s development story has required ambition, talent and foresight in a singular, politically controlled environment, the logic being that Singapore is too small for normative forms of multi-party governance.

Singapore is a small city by most standards, with a current population of 5.32 million people spread over 710 sq km. 3 It reaches beyond its diminutive size, however, claiming importance alongside its larger brethren: Tokyo, Shanghai, London or New York while serving as a seductive image that influences cities from Beijing to Dubai and from Moscow to Vietnam. Between the East and the West, between the democratic and the autocratic, between free market capitalism and state-controlled socialism, so Singapore’s image is crafted. In this city of samples, selected from the best practices of the world, where famous architects work with renowned multinational corporations, where international standards are imported along with branded goods and notable institutions educate the population, less developed cities hope that they, too, can “make it” through their own Singapore success story. Singapore’s small size may also be its best asset here,

never appearing too powerful or aggressive, allowing other cities to copy, appropriate and sample without the negative repercussions of following the “West”, becoming Americanized, or following old colonial powers for inspiration. To sample Singapore is politically advantageous, for Singapore causes few negative repercussions on the world stage; its own agendas are primarily business-oriented, and its military, though highly advanced, comes with little more than a “Singapore Sting”. 4

Simulations, facsimiles, clones and appropriations of the “Little Red Dot” — little Singapores — are sometimes taken as a whole package and other times as fragments and grafts. Each of those references exhibits parts of the Singapore model — a construct of state-managed capitalism, corruption-free governmental institutions, economic and capital liberty, strong social and cultural management, and highly planned and expedient urban form. In an age of the “samesame” city, where globalization merges urban centers in image, form and policy, Singapore is held up as the promise for cities in developing countries outside the normative western sphere of influence. 5 Singapore is a model without the messiness and — more importantly — without the arrogance and disruptive public of the West. It is a model found in a tiny country that shouldn’t matter but somehow does.

Imitating Singapore: The City-State’s Model has Become its Most Important Export

ship and the International Tech Park, both in India, all speak in physical terms of Singapore’s growing international influence — a nation-state now as architect, crafting cities afar in its own image. 6

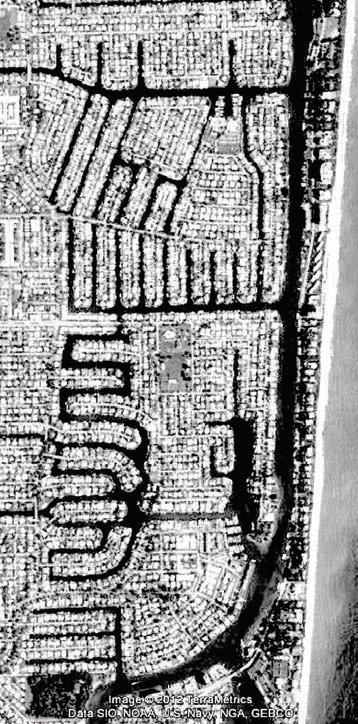

An observer noted that at a ceremony to mark the start of construction on the first phase of the Tianjin EcoCity, “investors said the 10-year plan was intended to be ‘scalable and replicable’ so it could be used across China, India, and other developing nations”.7 The scalable and replicable — two of the self-professed “Three Abilities” noted on the Tianjin Eco-City website — are key terms here. Imagine a Singapore product line not of a small electronic component or a petrochemical good exported from Singapore, but the creation of an entire urban environment able to be expanded or compacted as needed, stamped across the landscape as miniature Singapores. The plans for the Tianjin Eco-City accommodate 350,000 across 30 sq km, at a population density higher by almost 4,100 people per sq km than Singapore itself. In addition to scalability and replicability, “Practical” (a stereotypical symbol of Singaporean know-how) rounds out the “Three Abilities” guiding the development. Joined with the “Three Harmonies” — described as harmony of “people with other people, people with economic activities, and people with the environment” — the success of Tianjin is narrowed down to 22 quantitative and 4 qualitative KPIs (an acronym for key performance indicators). 8 What is most noticeable here is that the list of quantitative criteria is more than five times longer than the qualitative one, the implication being that if the city is made in the correct proportions and enough checkboxes on the list are marked, then the city will be a success.

important than quantitative measures of efficiency and traffic planning. Today, these lessons seem lost in Singapore’s current exports, suffocated in an atmosphere of quantifiable tools and checklists.

Looking west, Dubai has modeled its development on becoming a “Singapore of the Middle East”, while New York City was awarded the Singapore Lee Kuan Yew World City Prize in 2012. 11 The implication follows that Singapore has now become the veritable expert in “honouring outstanding contributions towards creating livable and sustainable urban communities around the world”.12 Singapore has become the de facto symbol for the best of urban environments, and now stands in judgment of the rest.

Cities

Singapore is not only a symbol representing a process of change, but a symbol that any city starting from the “third world” can reach a “developed” state in the space of a single generation. Singapore has even begun to quietly export itself — to duplicate its developed self — to other nations. In a quiet new form of globalized trade, export and influence, Singapores small and large are sprouting in the countryside of China, replacing paddy (rice) fields in Vietnam, and reworking entire new townships in India.

The Sino-Singapore

Tianjin Eco-City and the Sino-Singapore Suzhou Industrial park in China; the Vietnam Singapore Industrial Park in Bac Ninh, Hai Phong and Binh Duong, all in Vietnam; and the Pocharam-Singapore Town-

This recalls the words of Le Corbusier in his 1929 urban planning tome The City of To-Morrow and its Planning, in which he claims that “a city made for speed is made for success”. 9 Eliminating congestion by having expressways surrounding towers in the park was a singular quantitative logic that decimated much of Europe and American’s urban environments in the spirit of progress and modernization. Quantification, efficiency and practicality overran considerations of quality of life and social bonds. This was debunked 30 years later by Jane Jacobs’ influential work, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. 10 For Jacobs, the qualitative life on and about the street was far more

The Singapore model is its own best export, a product of best practices where water management, industrial management, traffic control, taxation policy, real estate investment and public housing policies contribute to a view that Singapore is a center for urban research and an urban solution provider where “livability”, “sustainability” and “success” can be researched, taught and exported as a knowledge product.13 Tag lines, including “City in a Garden”, “Live Work and Play”, and “Your Singapore, Clean Green and Blue” all contribute to the city as a brand, a product not only to be consumed by visitors and inhabitants, but also a product to be replicated by other cities looking to Singapore. For Singapore, if the 19th century was the century of colonization and the 20th century was the century of self-determination, then the 21st century is turning out to be the century of the city, a city for export in a rapidly urbanizing Asia.

A series of centres and labs have sprouted in Singapore’s academic and governmental institutions, reaffirming Singapore’s focus not only on the success of its own urban project but also on urban research as a new knowledge frontier (and market) for Singaporean know-how. The Future Cities Lab at NUS, the Centre for Liveable Cities,14 the Centre for Sustainable Asian Cities, City Form Lab, and the Lee Kuan Yew Centre for Innovative Cities all represent Singapore’s recent efforts at building up a resource base for urban solutions, problem solving, and technocratic knowledge concentration. 15 Pragmatism, data collection and scientific analysis appear to play the most important roles, with the assumption that if enough data could be mined from the urban environment then the holy grail of city making and city management would be found. The titles of recent seminars, lectures and research projects include “Seminar on Urban Traffic Knowledge Extraction”; “Detecting Pedestrian Destinations from Ubiquitous Digital Footprints”; “Revisioned Engineering for Cities of the Future”; “Benchmarks, Best Practices, and Framework for Sustainable Urban Development and Cities”; “Urban Transport Modeling in High Density Environments; Measuring Urban Expansion in East Asia”; “Walkability in Singapore”; and “Location Patterns of Street Commerce”, among many others. This is by no means an exhaustive list, as I have found only a handful of topics that prioritize the qualitative attributes of city thinking, city inhabitation and city meaning. 16

PhD holders abound in newly minted laboratories with spectacular names: “Create”, “Research”, “Innovation” and “Enterprise”, with bright signs glowing shades of red and white in the evening air, busy with the promise that cities and urban environments are no

longer historical or cultural productions alone but primarily sets of data, discernible, describable, optimizeable and, most importantly, able to be replicated and exported. The debate on the constituent elements of the cultural, social, historical or political components of the crafting of “better urban environments” is covered over by a context of pragmatic data-driven solutions and key performance indicators.

Outbursts from the recent tie-up with Yale University, the American bastion of liberal arts education, and the National University of Singapore provide only a brief respite from the emphasis on scientific exactitude and the creation of deployable knowledge. Yale’s “outsourcing” sparked a vigorous debate in the United States, but that dialogue was all but ignored in Singapore save for an article by Eric Weinberger in the local paper Today, a piece published originally in the U.S. magazine The Atlantic. 17 ETH Zurich, Duke, MIT, University of Chicago and NYU have all set up programs in Singapore with little contestation, quietly reaffirming Singapore as the research hub of Southeast Asia. 18 Clearly these institutions appreciate the research money generously granted by the Singapore government, discarding any difference of opinion on ideas of freedom, ethics, speech, human rights and culture identities that have so ensnarled the faculty at Yale.

I am struck by the lack of discussion on quality, on the humanistic inspirational and symbolic components of the city in these many city labs and centers. The debates and development of thinking on social justice, self-determination, creativity, poetry, freedom of expression and personal happiness all play a minor role, to Singapore’s detriment. A recent poll of 150,000 people around the globe found that Singapore topped the list of the most unhappy populations in the world, a shocking statistic given that all the quantitative measures of Singapore rank it as one of the most developed and prosperous countries in the world. Clearly quantity and quality are not proportional or necessarily relational. Context, cultural difference and regionalism remain small aberrations in the data sets and long checklists as cities grow under the inspiration of the Singapore success story.

Singapore Seductions

Indeed, who needs such subjective preoccupations when Singapore’s own success is so seductive? Serious crime is almost non-existent, general education is of a high standard, jobs remain relatively plentiful, and economic opportunities abound. Singapore is accessible, its infrastructure is well-maintained, and healthcare is the envy of many nations in Southeast Asia. It seems that the best practices from all over the world may be found in Singapore, practices that are manifest in every facet of its existence.

Not surprisingly, Singapore is embraced by the corporate world. The majority of multinational corporations have headquarters in the country, from Microsoft, Apple, Proctor and Gamble, Unilever, Citibank, and Standard Chartered Bank, to Sands Casino, Universal Studios, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) and Bloomberg News.

The climate also makes it easy to do business in Singapore. The weather in this tropical outpost ranges constantly between 24 to 32 degrees Celsius (75 to 90 degrees Fahrenheit), with roughly 80 percent humidity. That ensures a perfectly consistent atmosphere for continual productivity; the ideal operational base without the troublesome climatic problems of hurricanes or cyclones, tornadoes or blizzards, tsunamis or earthquakes, volcanic eruptions or wild fires. Atmospheric disruptions to the work schedule are few and far between, if any. A temporary thunderstorm or monsoon wind gust is the highlight of a city working in an atmosphere of complete consistency where days become years without temperate markers or climatic events beyond control.

While the West once looked at Singapore with trepidation in the late 1990s, with fears running the gamut from one-party rule and limitations on liberty to deliberate censure of the press, those reservations are now few and far between. Today, the West sees Singapore as the center of a new world order — a form to be studied and cautiously celebrated. 19 In essence, those changes represent the aspirations of a growing urbanized world outside of the dominant “Western” model. Singapore represents a counterpoint to the democratic liberal models of urbanization. Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas notes that “the messy slow dirty game of

representative democracy and freedom of expression is not a necessary ingredient to economic success”. As former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew claimed, “You’re talking about Rwanda or Bangladesh, or Cambodia, or the Philippines. They’ve got democracy, according to Freedom House. But have you got a civilized life to lead? People want economic development first and foremost. The leaders may talk something else. You take a poll of any people. What is it they want? The right to write an editorial as [they] like? They want homes, medicine, jobs, schools.” 20

Even Marina Bay Sands, 21 Singapore’s current symbol of economic success, combined with an image of a country relaxing its control, albeit through entertainment and gambling, has been exported to Chongqing, China, and remade larger and grander by Singapore’s own CapitaLand Limited. In China, the scheme has been expanded with six towers, the familiar sky bridge, and a massive shopping podium — Marina Bay Sands cloned and on steroids. In general, it appears amazingly blatant in its disregard for context and locality. Any attempt to conceal the exportation from Singapore seems irrelevant. In an age of expedient solutions, the architectural export is easier than invention based on context and locality. 22 Critical regionalism has long been abandoned in an age of simulation and cloning. As Koolhaas claims, Singapore is “a test bed of tabula rasa”; rarely has Singapore embraced locality for its future. 23 William Gibson alluded to such Singapore methodologies 20 years ago in far less flattering terms, asserting that Singapore was “cloning” itself in a “franchise operation” that would soon be our “techno-future”. 24 What was considered criticism in 1993 is reality today.

Taking these export ambitions to task, Singapore’s entry for the 12th Architectural Venice Biennale, in a statement of extreme exuberance — albeit with an undercurrent of internal criticism and devoid of stereotypical Asian modesty — proclaimed that Singapore is a model for the world. Debate on the distinction between “the model” and “a model” occurred between fellow curators and I; timidity won out. Only 1,000 imitation Singapores would be needed to house the world’s population. A Singapore the size of Texas would contain everyone, or a France doubled in size would do, our cheeky assertions suggest. We could all live in one giant Singapore if only we were bold

enough and had the right list of key performance indicators, so the narrative goes. The intention was to at once celebrate the highly influential and successful city-state but also to project its limits as a means to uncover critical questions of the direction and forms of urbanization.

Barring all the exuberance, after urbanization in Singapore has been so successfully implemented — where homes, medicine, jobs and schools have been provided — grumblings in the local coffee shops known as kopitiam, food stalls, and in the blogosphere pose the question: What next for Singapore proper? In the early 1990s, then Deputy Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong elaborated on Singapore’s “Next Lap”, implying that a new phase of development had begun. But today, the next lap around the same track seems redundant. Segments of the population have started to call for a recalibration, a different course, through more public vocalization. What happens to Singapore after urbanization is complete? What happens when GDP per capita is one of the highest in the world? And what happens when Singapore is now the urban model judging the globe?

In 2011, the general elections in Singapore saw the prevailing People’s Action Party (PAP) gain success yet again — they have had a continuous majority for 46 years — but with the lowest percentage of the vote in Singapore’s history at 60 percent. Termed a “watershed election” by the Opposition, the important questions of where Singapore is heading, how, and led by whom, is up for debate. Two by-elections in Hougang (May 2012) and Punggol East (January 2013) saw continued gains for the Opposition in cementing the ground sentiment that the PAP is less powerful than it once was. But more important than the symbolic Opposition gains, larger questions for Singapore on its urban program are now up for debate.

Beyond available data, quantifiable measures and performance indicators, what are the foundational values for Singapore’s continued success? Why, despite the best efforts of politicians, civil servants and planners alike, do Singaporeans suffer from dreams of their next get-away vacation or — even worse — emigration and retirement to countries near and far?

In the current atmosphere of xenophobia, and with the tightening of immigration policies, I believe a more pertinent question is whether talent and workers in Singapore will continue to embrace the metropolitan and cosmopolitan aspirations that have made Singapore the success story that it is. Will Singapore chart its own course, becoming not only a collection of best practices and quantifiable measures but also a country and citizenry committed to its own qualitative vision and philosophical ideals that its population can believe in? Will Singapore, at this stage, create the foundations for “what ought to be”, not just what is materially comfortable, given that it has, by and large, reached material success?

bai’s Palm Islands. 26 This “breakthrough” simulation where the developer claims to offer a “better life” can be yours for only $7,000 USD. The better life may be bought and sold, but only when it is completed; the completion date for Coastarina is still unknown.

Contexts Closer to Home: a Neo-Regionalism

As an extension of Singapore’s global reach, Singapore exports itself to locations far away; geopolitics, market share and international reputation all seem to play important roles in these ambitions. Yet much closer to Singapore’s local geography, Johor Bahru in southern Malaysia and Indonesia’s Batam Island claim to be “Singapores” in the making; albeit not an export of Singapore proper where it directly remakes its neighbors, but rather Johor Bahru and Batam trying to copy — and import — the Singapore success story. Iskandar, also in Malaysia’s state of Johor, promotes a vision uncannily similar to Singapore, where Singapore’s own ring city concept plan has been transformed as a giant arc, a linear city for the sea fronting the Straits of Johor. It is as though Iskandar is “Singapore Unwrapped”, straightened and draped along the Straits. Iskandar’s Danga Bay hopes to be the Marina Bay for Johor Bahru, offering “dynamic services and [a] financial centre, with rows of restaurants, top-notch retail outlets and top draw events and activities offering the best in residential and commercial properties… as well as a shopping paradise”. 25

Batam, along Singapore’s southern sea periphery, hopes to remake itself into a tourist destination similar to Singapore. In a strange yet slightly outdated reference, Batam is remaking its port through land reclamation into an image of Dubai’s collection of man-made islands, The World. Named — or renamed, one might say — Coastarina, the official tagline claims a breakthrough concept inspired not by The World, but by Du-

Funtasy Island, recently claimed as the “largest eco theme park of the world” located “nearby Singapore” but that is part of the Indonesian Riau Archipelago, intends to have its own immigration portal — escaping the geopolitical necessities of nearby Batam. Designed by Singaporean architect Tan Kay Ngee, the proposals are simulations of Singapore’s own “premier” resort development at Sentosa Cove. Indeed, Funtasy Island is in Indonesia, but it is clearly targeting Singaporean money. An artistic impression of Funtasy Island at night, with the Singapore skyline in view, makes the reference entirely visible with Singapore’s iconic architecture — The Marina Bay Sands and the Singapore Flyer — both distinctly visible from 10 miles (16 km) away. Forget Indonesia, the image implies as Batam sits in the darkened sky, visible to the right side of the horizon; this is a playground for Singapore. From this Singapore-centric perspective, Batam is still in the dark: the censoring of Singapore’s less developed neighbors is obvious.

Between Myopic and Hyperopic

Singapore holds the dubious distinction of having one of the highest rates of genetic myopia (nearsightedness) in the world, with up to 80 percent of its populace rated as myopic. Studies of children in Singapore and Sydney, Australia documented an average of 3 hours of outdoor play per week for the children in Singapore and 14 hours of the same for children living in Sydney. Indeed, a mere 25 minutes per day for Singaporean children in a space of increasing interiority has inadvertently created — at least metaphorically — a crisis of vision. On a national level, Singapore’s own crisis of vision is not of myopia but of hyperopia – where images in the far distance are in clear view, but items near remain a blurry image. Singapore performs hyperopia, looking to be closer to New York or Shanghai than to its own geographic neighbors in Johor and Batam that are just a short drive or ferry ride away. Indeed, Singapore, despite is small size and emphasis on its global position, sits in the center of a much larger region of islands, peninsulas and archipelagos, and a small dose of myopia may be in order. Ten million people populate the immediate region. Linked by the sea and the three straits — the Johor Strait, the Malacca Strait, and the Singapore Strait — areas in nearby Malaysia and Indonesia share with Singapore a mutual history borne of interconnected geopolitics, spatial inhabitation and shared histories. In this immediate context, New York, Shanghai and London have little meaning.

On the 1971 issuance of the Singapore master plan (known as the 1971 Concept Plan, which was revised five times through 1991), both the state of Johor to the north and the Riau Archipelago to the south were not shown. Singapore became an island divorced from its neighbors not only politically and spatially but also, most importantly, in terms of aspiration. The implication is that Singapore has no hinterland; that its global networks are more important than its immediate neighbors north and south. Singapore’s surrounding context returned only in the 2001 version of the Concept Plan, with a reemergence of Johor’s coastline to the north, while Riau remained hidden in the vestiges of an empty sheet of paper. Indeed, set in the spirit of nation building, nationalism and the exertion of a fundamentally unique Singaporean identity, the smaller Johor State and Riau islands remain not only less relevant in these plan representations, but their presence sym-

bolizes a contamination of the construction of a newly independent state. Nationhood and nationalism depend on exclusionary practices. In this example, hyperopia serves the interests of a nation looking to establish itself by looking afar.

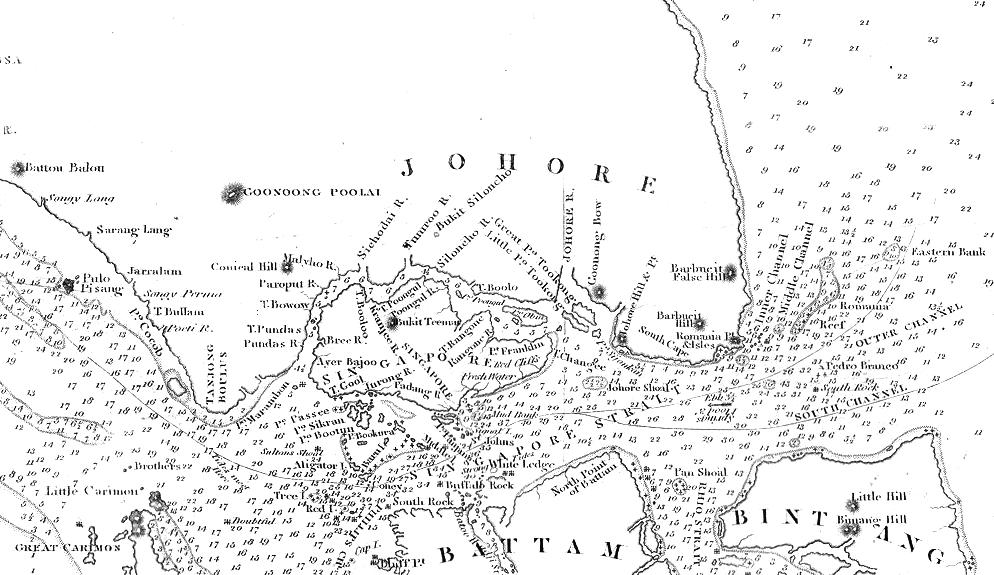

Yet, as far back as the 1800s, maps from the colonial British, Dutch, and Japanese illustrated a region in its entirety — a Singapore linked with Johor and Batam (the primary island of the Riau Archipelago) in a larger region of interconnectedness. That interconnectedness, administered by the conflicting colonial powers of the British, Dutch, Portuguese and, later, Japanese, centered the region on economic development rather than on political brinkmanship or internal reorganization. Only within the last decade, with an expanding demographic in Singapore, has there been a greater degree of political cooperation and mutually shared interests. The region is finally reconnecting itself. In the case of Singapore and Malaysia, the linkage will take physical form: the 25 January 2008 announcement of an underground mass transit subway spanning from Singapore’s central business district to Woodlands in the north and further linking to Johor Bahru’s Rapid Transit System proper will link Singapore to the larger region by modern mass transit. And in February 2013, Singapore and Malaysia announced their mutual intention to link Singapore and Kuala Lumpur with a highspeed rail network. In the words of Prime Minster Lee Hsien Loong, the proposed rail link will bond the two cities into “One virtual urban community”. 27

pore economy. Batam provides needed space for oilrig manufacturing, entertainment and downstream labor — the rough and manual labor jobs that seem less beneficial for the Singaporean population on its own shores. Batam has been labeled an “alternative pleasure periphery” where Singaporeans, predominately men, go to enjoy golfing, relaxation and sex workers, utilizing and exploiting the periphery as an alternative to Singapore’s straight-laced social norms.

On Bulan Island, located to the southwest of Batam, sits an enormous pig farm that exports pigs to Singapore. A thousand pigs sail to Singapore every night for slaughter. Aerial photography shows clusters of pig sheds linked with retention ponds dotting the island, which has become known as “Pig Island”. The irony of such a place situated in Indonesia has so far been lost in translation.

Gas and water pipelines connect the three countries, supplying Singapore with freshwater despite its best attempts at being hydrologically independent through New Water technology that supports 30% of its consumption needs. Gas lines cut cross the Straits, as do electrical, communication and water lines, all of them connecting the three nations in a hidden rhizomatic network.

of land, while Singapore’s land was limited. Industries and occupations deemed less productive to Singapore were strategically dispersed to Singapore’s periphery. What would be considered the ring corridors surrounding most metropolitan regions of the West became, in Singapore’s case, an act of traversing national boundaries. The title of “SIJORI Growth Triangle” for the region reflected the avoidance of Singapore centricity, partly by creating a label out of the first two letters of each state — Si-ngapore, Jo-hor, Ri-au.

In the intense political landscape of Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore, the economic success of the latter state could not be seen as independent of its neighbors. Indeed, it is Singapore’s regional development that has provided it with its many streams of sustenance, all of which have led to its impressive growth.

SIJORI Growth Triangle

Despite Singapore’s preferred linkages to larger cities in the seemingly more important global network, Singapore’s survival remains critically interdependent on the local region. Air rights over the state of Johor enable Changi Airport to operate while shipping rights through the Malacca Straits ensure Singapore port’s livelihood. Both provide the vast amount of raw resources needed for the nation to survive. Fresh water and natural gas come from and through the territories of Johor and Batam, the very arteries to the Singapore heart. A hundred thousand Malaysians working in Singapore move across the Causeway daily and pass through one of the busiest checkpoints in the world, primarily working in industries supporting the Singa-

Ethnically, a diverse composition of Chinese, Bumiputera, Javanese, Malays, Indians and others share more commonalities based on their shared trades, aspirations and histories than their political and geographical boundaries suggest. If there is one cultural commonality that binds these ethnic communities together, it is the shared love of local food. This common love of local food has created apolitical spheres in which the regional population can debate, challenge and celebrate each spoonful in the dreams of their next meal.

After a tumultuous history of separation, suspicion and antagonism in the 1960s, an early attempt at regionalism began in 1989. The SIJORI Growth Triangle was announced in a collective statement of shared aspirations that asserted that growth for all three states was interdependent. Signed by then Deputy Prime Minister Goh, who later became Singapore’s second prime minister, the triangle was expanded in 1994 to include all of Malaysia and Indonesia proper. Good intentions aside, the subtext was that Johor and Batam had plenty

Today, as in 1989, Singapore remains the center by all measures. More economically robust from a global perspective, relying on its much larger global network, Singapore has become a model to emulate. Johor and Batam gaze across the sea at Singapore’s towers of glass and concrete, hoping that they, too, can produce “success”. Mutated little Singapores are found in the local press of Johor and Batam, as they aspire to what they see as achievement. To avoid or repress this Singapore centricity is to avoid the very realities of the SIJORI Growth Triangle, for the Sijori region is, after all, SI-jori with an emphasis on Singapore.

Singapore Metropolitan Region

Singapore is networked far beyond its diminutive region, linking the city-state globally. In the minds of many in Singapore, this thinking comes at the expense of regional relationships. Connections to China, Vietnam and now Myanmar, with its increasingly open economy, often take precedence over the regional, where success stories in the local press refer to international locations afar rather than ones just over the Causeway or across the Straits. Indeed, the region is regarded with suspicion rather than promise, another way to obscure the tremendous necessity that the region provides for Singapore’s own livelihood. Singapore’s Woodlands Customs, Immigration and Quarantine (CIQ) Checkpoint, built in 1998, manifests these deep suspicions through 10 observation towers

peering over the Straits and the adjacent coastline of Singapore. The symbolism clearly refers to a garrison state mentality in which incoming workers, tourists and visitors are regarded with suspicion. In 2008, Malaysia countered with its newly revamped checkpoint across the Straits. Designed as a series of large flat and curving roofs, and set off-axis from the Johor Straits, the symbolism and design intention are entirely different. The intent of the Sultan Iskandar CIQ Complex is not to repel visitors but to attract them as a means of tapping the burgeoning Singapore economy. The architectural form is open, embracing movement and the flow of people into and out of Malaysia, rather than reaffirming previous distrust.

Indeed, Singapore is in need of its neighbors to facilitate its very survival. If one thinks of Singapore as a city rather than a state alone, where the problems of nationalism are scrubbed away in such a way that the interconnectedness and shared histories of the region are pushed forth, then indeed the Singapore Metropolitan Region more aptly describes that amazingly complex territory.

Applying metropolitan frameworks to the region puts the emphasis not only on the urban configurations of Johor Bahru, Batam and Singapore proper but also on the ‘polis’ in the etymology of ‘metropolis’. 28 The emphasis is then on the people of the region. It is their shared aspirations for livelihood, happiness and freedoms, small and large, which are often so overlooked in an expanse so marked by economic disparities, political and religious differences, and cultural divergence. And it is precisely at this time in Singapore’s history, when population growth has unsettled the citizen population and xenophobia has become evident, that a look to metropolitanism and cosmopolitanism as a vision for an interconnected region is a necessary antidote to such negative ideologies.

As illustrated in the following pages, the Singapore Metropolitan Region traverses boundaries, indicating shared territories of the sea, interconnected transportation, trade and ethnic relationships. It shows the duplication and triplication of urban and architectural models from one locale to another, the shared aspirations of the people and their governments to be modern, relevant and economically robust.

Clearly the title Singapore Metropolitan Region prioritizes Singapore, for the city-state is the center of this region, both historically and geographically. It has the largest population and gross domestic product (GDP), and the greatest military strength. Its cultural, economic and political influence cannot be underestimated. Its regional influence is tremendous. And yet, it is a product of its location, leveraging on Batam and Johor as its de facto hinterland.

Now, after almost 50 years of hyperopia, Singapore is looking north once again. It is seriously considering co-investing in Iskandar, not to create the low-cost industrial production facilities of the 1990s, but with modernized medical facilities, retirement communities, and educational and entertainment zones. Singapore’s government-linked investment corporation Temasek Holdings, in a joint venture with Khazanah Nasional of Malaysia, announced in July 2011 the commencement of two developmental projects, the first focusing on “Urban Wellness” and the second a “Resort Wellness” development including serviced apartments, a corporate training centre and commercial, retail, residential and wellness-related facilities. Though in its infancy, Singapore is beginning to embrace its neighbors, not just for exploitative industrial outsourcing, but for expanding the living options for its population. This could be viewed as an outsourcing of populations, though I see it as a step forward for a region that views itself with less suspicion and more shared aspirations. Indeed, Singapore’s success is ever more dependent on the success of its geographic neighbors not as a manufacturing center, but as a territory of shared aspirations and combined metropolitanism.

To understand the region of Johor and Batam is to understand Singapore; likewise, to understand Singapore is also to understand Johor and Batam. Each reflects the others, each a mirror sitting across the Straits. This book highlights the shared histories, cultures, geographies and aspirations through simple yet direct graphical notations. The intent is to collect and examine the spectrum of influences on the region, not as three independent states or nations, but as a collective territory of thought and action.

The intent of this body of work is not to produce a conclusive pronouncement or totalizing history but to document the plurality and complexity of the area so

that a cogent picture may be formed with a regional perspective. Short introductions are intersected with data and diagrams as intellectual counterpoints, capturing alternative narratives less easily explained through visual devices alone. The first chapter on the historical interrelationships between Singapore, Johor and Batam maps a historical axis of the shared commonalities between the three states; the second chapter elucidates the complexities of the Singapore Metropolitan Region as one territory. The chapter on “Samesame” models represents the homogenizing influences of urban and landform strategies emerging as symbols of economic success throughout the world, Singapore being only one facet of this global trend. The fourth chapter on “Dencity” depicts various density models as a series of options, opening up available possibilities as counter-narratives to Singapore’s own singular urban model. The final chapter illustrates specific design propositions that consider Johor, Batam, and Singapore yet interlinked to the many geopolitical and demographic forces that affect the larger region. Within these pages, a cultural, economic, and geographic polis comes into focus, a cosmopolitan landscape that is the Singapore Metropolitan Region.

Endnotes

1 Lee Kuan Yew, From Third World to First: The Singapore Story, 1965-2000 (Singapore: Times Editions, 2000).

2 Kampong is Malay for “hamlet” or “village”.

3 A white paper by the Singapore government projected that the population could reach 6.9 million by 2030. See Population White Paper: A Sustainable Population for a Dynamic Singapore, January 2013. Accessed January 30, 2013, http://202.157.171.46/ whitepaper/downloads/population-white-paper.pdf.

4 Jim Sleeper, “Blame the Latest Israel-Arab War on... Singapore?”, The Huffington Post, November 17, 2012. Accessed January 28, 2013, http://www. huffingtonpost.com/jim-sleeper/blame-the-latestisraelar_b_2147509.html.

5 In Singapore, word-doubling indicates determination and enthusiasm. Common instances are when taxi drivers emphatically proclaim “Can! Can!” or “Confirm confirm” in their determination to take one to one’s destination on time.

6 Vibhor Mohan, “Singapore Model for Metro Profit”, The Times of India, May 1, 2009. Accessed January 28, 2013, http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes. com/2009-05-01/chandigarh/28174508_1_singaporemodel-rites-metro-project.

7 Jonathan Watts, “China Teams Up with Singapore to Build Huge Eco City”, The Guardian, June 4, 2009. Accessed January 28, 2013, http://www.guardian. co.uk/world/2009/jun/04/china-singapore-tianjin-ecocity.

8 KPI is an acronym often used in Singapore for “Key Performance Indicators”.

9 Le Corbusier, The City of To-Morrow and Its Planning (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1929), 179.

10 Tianjin has 11,666 people per sq km while Singapore has 7,493 people per sq km.

11 Caroline Anning, “Dubai vs Singapore – The StepUp”, Executive Magazine, October 3, 2010. Accessed January 28, 2013, http://www.executive-magazine. com/special-report/Dubai-vs-Singapore-TheStepUp/668.

12 “Lee Kuan Yew World City Prize”, Urban Redevelopment Authority. Accessed January 28, 2013, http:// www.leekuanyewworldcityprize.com.sg.

13 For example Chinese, Vietnamese and Asian students and diplomats visit Singapore to study Singapore policy and government through various venues: the independent think tank Singapore Institute of International Affairs, The Institute of Defense and Strategic Studies at Nanyang Technological University, and the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore. As Kishore Mahbubani states in the Dean’s Welcome on the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy website, “Finally, the world has come to recognize that Singapore provides one of the best public policy laboratories in the world. Many independent international surveys confirm that several of Singapore’s public policies are among the best-performing in the world.” See “Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy”, National University of Singapore. Accessed December 28, 2012, http://www.spp.nus.edu.sg/Dean_Welcome.aspx.

14 The Centre for Liveable Cities was established by the Ministry of National Development and the Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources in June 2008.

15 In full disclosure, even I have created SMS — Singapore Metropolitan Studio – to showcase urban and city research done at the Department of Architecture at the National University of Singapore.

16 “Historic Structure and Dynamics of the Building Stock of Singapore”, Future Cities Laboratory; “Urban Sociology”, Future Cities Laboratory; and “The Built Environment and Quality of Life of Older Persons” are the names of several seminars and research labs working on qualitative components of the city.

17 Eric Weinberger, “Why is Yale Outsourcing a Campus to Singapore”, TODAY. Accessed December 28, 2012, http://www.todayonline.com/World/ EDC111109-0000004/Why-is-Yale-outsourcing-acampus-to-Singapore.

18 NYU’s case is surprising given that their Tisch School of the Arts is packing up and returning to New York as quietly as it arrived, ending its on-the-ground experiment by 2014, as noted in Patrick Frater, “Tisch Asia Headed for Closure”, Film Business Asia, November 9, 2012. Accessed January 28, 2013, http:// www.filmbiz.asia/news/tisch-asia-headed-for-closure.

19 “Latin Americans Most Positive in the World, Singaporeans are the Least Positive Worldwide”, Gallup Inc., December 19, 2012. Accessed at http://www. gallup.com/poll/159254/latin-americans-positiveworld.aspx#1.

20 Han Fook Kwang, Warren Fernandez and Sumiko Tan, Lee Kuan Yew, The Man and His Ideas (Singapore: Singapore Press Holdings, 1997).

21 Marina Bay Sands is an integrated resort located at Marina Bay. It was designed by Moshe Safdie Architects.

22 “Moshe Safdie’s Chongqing Complex Looks Just Like Moshe Safdie’s Singapore Complex”, Architizer, December 8, 2011. Accessed January 31, 2013, http:// www.architizer.com/en_us/blog/dyn/35395/moshesafdies-chongqing-complex-looks-just-like-moshesafdies-singapore-complex/.

23 Rem Koolhaas, “Singapore Songlines”. In Small, Medium, Large, Extra-Large: Office for Metropolitan Architecture, Rem Koolhaas, and Bruce Mau, edited by Jennifer Sigler, 1035. New York: Monacelli Press, 1998.

24 William Gibson, “Disneyland with the Death Penalty”, Wired Magazine, Issue 1.04, Sep/Oct 1993.

25 “Development Elements”, Danga Bay. Accessed on January 4, 2012, http://www.dangabay.com/.

26 “Living in Batam – Coasterina Residence”, Batam Indonesia Free Zone Authority. Accessed January 4, 2012, http://www.bpbatam.go.id/eng/livingInBatam/ residence.jsp.

27 Rachel Chang, “Singapore-Malaysia Prime Ministers’ Annual Retreat; Rail link to make S’pore, KL ‘one virtual urban community’”, The Straits Times, 20th February 2013.

28 “Metropolis” is from the Greek “mētr”, meaning “mother”, and “polis”, meaning “Public” and “State”.

CHICKS AND CHICKEN: SINGAPORE’S EXPANSION TO RIAU

Dr. Freek Colombijn Associate Professor Department of Social and Cultural Anthropology Vrije Universiteit AmsterdamThe city-state Singapore has spilled over into its two neighbours, Malaysia and Indonesia. Singapore discovered in the Indonesian Riau Archipelago, resources that are rarely found near the centre of mega-cities — cheap land and cheap labour. To what extent Singapore’s presence offers reciprocal benefits to Riau is the question. For example, Singapore has not only moved the production of poultry for all Kentucky Fried Chicken outlets of the region to Riau, but also prostitution. This article will explore the consequences of Singapore’s expansion for Riau.

Since the British founded Singapore in 1819 the city has been a transportation hub and communication centre. After Singapore gained independence in 1965, export-led industrialization and a high-technology service industry have diversified the economy. The ever-expanding economy and growing population of the limited island territory have demanded innovative measures. Land reclamation taken up since the 1960s and the construction of high-rise housing and skyscraper offices could reduce the pressure on land for only a limited amount of time.

Mega-urban development in the city-state took a decisive turn with the concept of the Singapore-Johor-Riau (SIJORI) Growth Triangle. Then Singaporean Deputy Prime Minister, Goh Chok Tong launched this concept in 1989 at a time when the industrial development within the boundaries of the city-state reached its saturation point and when costs of land and labour were rising sharply. The basic idea was that the three regions pool their human and natural resources in order to attract new investors. Each corner of the triangle would put in its respective comparative advantage — Singapore its capital, technical skills, and management; the Malaysian state of Johor its land and semi-skilled labour; and the Indonesian province of Riau also its land and cheap labour. In reality, SIJORI does not represent a tripartite partnership but an arrangement by which

Singapore’s mega-urban growth can freely spillover into the territories of its neighbours (Macleod and McGee 1996: 425). Singapore was, and is, clearly in control — it took the initiative and provided the capital and management.

Fatal Attraction?

The encroachment of Singapore’s mega-urban region into Riau started on Batam, the island just south of Singapore. A series of bridges connects Batam to six other islands, which lie in a string to the south of Batam. Every half-hour, a speedboat leaves Singapore for the thirty-minute ride to Batam, which has evolved as an industrial centre and a tourist resort. The rise in the number of tourists in Batam is impressive — from none in 1983, via 60,000 in 1985, to 606,000 in 1991, 78 per cent of whom Singaporeans and 10 per cent Malaysians. In 1999, 1.14 million foreigners arrived at Batam airport, thus surpassing Sukarno-Hatta airport in Jakarta.

The island of Bintan is a freshwater reservoir for Singapore; an undersea pipe brings the water to the city. Bintan has also been developed as a tourist resort with 20 hotels, ten golf courses, and ten condominiums. Industrial estates can also be found on Bintan.

The other islands have more specialised functions. The island of Bulan is a centre of agricultural production. It was expected to have about 400,000 pigs by 2000, enough to provide 50 per cent of Singapore’s demand for pork. A crocodile farm of 55,000 reptiles provides leather and meat. Chicken production serves all the Kentucky Fried Chicken outlets of the region. Bulan will, surely, also become the world’s largest supplier of orchids. Karimun is used for oil storage and shipyards, two pre-eminently space-consuming activities. Singkep will be developed into a centre for ship-breaking yards. Over a hundred permits for sand quarries have been issued, spread over several islands, large and small, and more quarries operate illegally (Grundy-Warr and Perry 1996; Macleod and McGee 1996; Nur 2000).

The Indonesian government has lured foreign investors to the Batam Economic Zone with inducements such as duty-free import of capital equipment and duty free export of export-oriented production. Another attraction is that the Indonesian government has nullified environmental impact laws for the island. As such, Singapore is able to use Batam as a repository for the by-products of polluting industries, which are no longer allowed in the citystate itself, and a dump for dredged soil of dubious quality. Indonesia also accepts the kind of entertainment that Singapore prefers not to have under its own roof — 5,000 prostitutes work in Batam, of which hundreds are underage girls, smuggled to Riau against their will. The average tourist stay on Batam is 1.3 days, a typical weekend away from Singapore complete with sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll (Lindquist 2002).

The Indonesian government thrust all these changes down the local people’s throats. Batam was placed under the custodianship of the Batam Industrial Development Authority (BIDA), which remained outside the power of regular local legislative bodies, and had gained control of land through presidential decree. The Head of BIDA was the then Minister of Technology, B.J. Habibie, the most trusted favourite of former President Suharto. In most cases the Indonesian counterpart of Singaporean investors was the Salim Group, which again had very close connections with the Suharto presidency. The connection between the Salim Group and the highest Indonesian authorities helped them to acquire land — villagers were often pressed to move out from their homes with very little compensation. For instance, on Bintan six villages consisting of 2,200 families were relocated to make way for freshwater reservoirs (Anwar 1994: 27–28, 31; Macleod and McGee 1996: 429).

tion of 100 rupiah per square metre for their land, paid by the Salim Group, would after all be increased to 10,000 rupiah per square metre. In 1991 the landowners concerned had grudgingly accepted the compensation after pressure exerted by the state; it was now revealed that the Singaporean investors had offered a far higher price and there were questions about who had pocketed the price difference. After the loss of the political protection offered by the former President, the Salim Group had come into dire financial straits and was less willing than ever to pay extra money. Following a week in which tourist visits declined by 85 per cent, the demonstrators were chased away from the resort. Environmental Non-governmental Organisations (NGOs) that express their worries about the sand quarries first and foremost point to the Indonesian authorities that give out too many concessions or do not stop illegal quarries. Singapore’s influential role yet remains in the background.

People’s Response

Since Suharto resigned, the people have felt free to rake over old coals. In January 2000, demonstrators cut off the energy supply to an industrial estate on Bintan. Police reinforcements were immediately flown in from Batam and one occupant of the powerhouse was shot dead. Soon after 40 companies contemplated leaving Bintan. Other demonstrators occupied a tourist resort on Bintan, demanding that the 1991 compensa-

References

Anwar, Dewi Fortuna, ‘Sijori: ASEAN’s southern growth triangle; problems and prospects’, Indonesian quarterly, volume 22, issue 1 (1994), pp.22–33.

Grundy-Warr, Carl, and Martin Perry, ‘Growth triangles, international economic integration and the Singapore-Indonesian border zone’, in: Dennis Rumley et al. (eds.), Global geopolitical change and the AsiaPacific; a regional perspective, Aldershot: Avebury (1996), pp.185–211.

Lindquist, Johan, The anxieties of mobility: Development, migration, and tourism in the Indonesian borderlands, Stockholm: Stockholm University, Department of Anthropology (2002).

Macleod, Scott, and T.G. McGee, ‘The SingaporeJohore-Riau growth triangle: an emerging extended metropolitan region’, in: Fu-chen, Lo, and Yue-man Yeung (eds.), Emerging world cities in Pacific Asia, Tokyo et al.: United Nations University Press (1996), pp.417–464.

Nur, Yoslan, ‘L’île de Batam à l’ombre de Singapour; Investissement singapourien et dépendeance de Batam’, Archipel 59 (2000), pp.145–170.

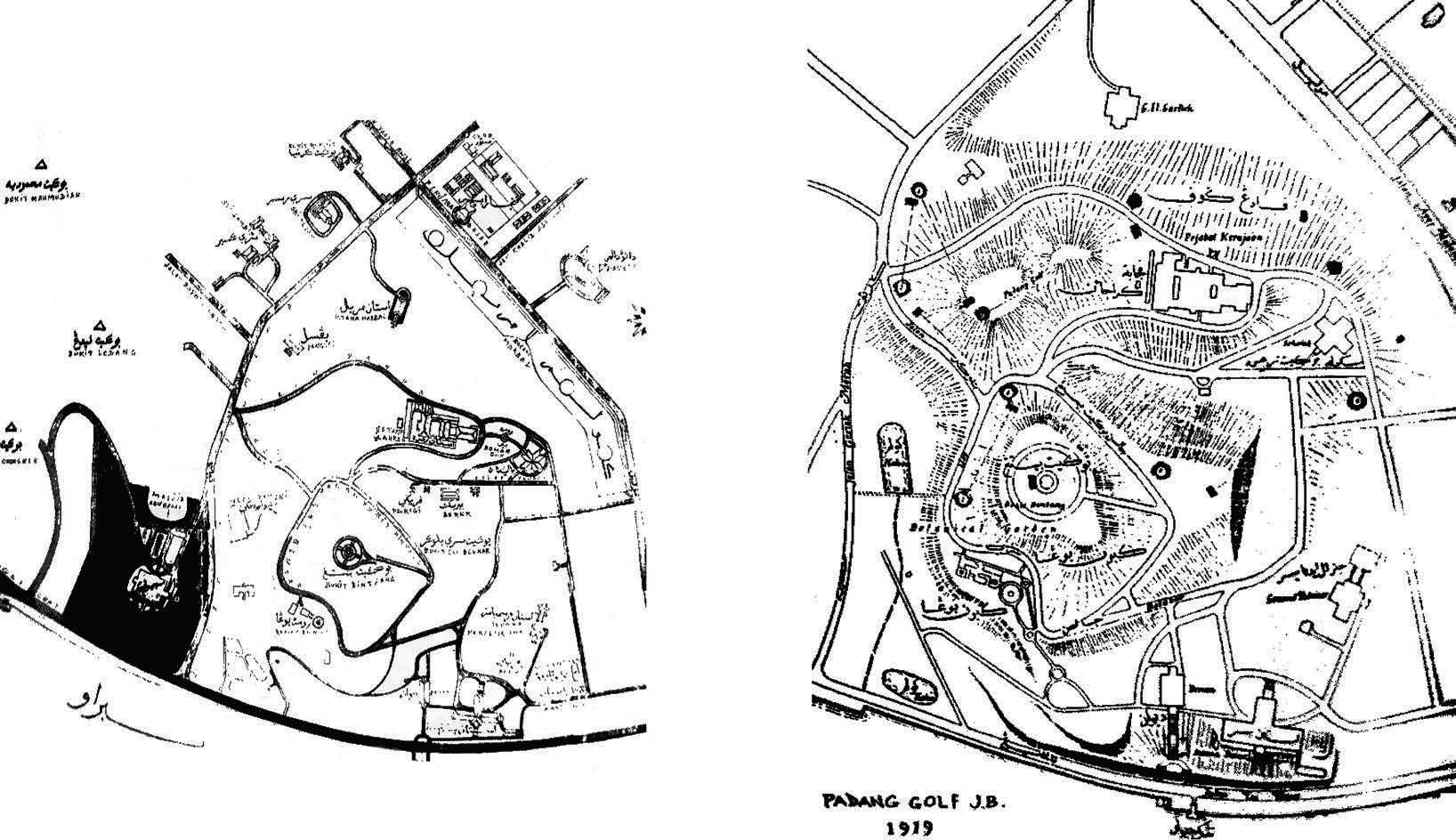

Sultan Mahmud Shah I Last Sultan for Melaka, Founder for Johore Lama

1. Melaka (1488-1511)

2. Bertam, Pulau Pinang (1511-1512)

3. Batu Hampar, Selangor (1511-1512)

4. Sungai Muar, Johor (1511-1512)

5. Ulu Jempoh, Pahang (1511-1512)

6. Pekan Tua, Kota Tinggi, Johor (1512)

7. Pulau Bentan / Bintan Island (1513-1518)

8. Pagoh, Johor (1518-1520)

7. Pulau Bentan / Bintan Island (1520-1526)

9. Kampar, Sumatra (1526-1528)

Sayong Pinang Kuala Sayong

Rantau Panjang

Kota Kara

KOTA TINGGI DISTRICT

Kampung Makam

Pasir Raja

Kota Seberang

Batu Sawar

Gonggong (Tanah Putih)

Panchor Kampung Air Putih

Bt. Seluyut Johor Lama

Tanjung Batu

Kota Batu

Batu Buruk

Kg. Kong Kong

Sungei Johore

Johore in the history

10th Century: Wurawari (‘clear water’)

15th Century: Ujung Tanah (‘land’s end’)

16th Century: Ganggayu (‘jewel’)

SINGAPORE

1511-1877 | Shifting of Ruling Places in Kota Tinggi District (Johore Lama)

1. Pulau Penyengat (1513 - 1526, 1722 - 1819)

2. Tanjong Pinang (1945 - 1957)

3. Pekanbaru (1957)

4. Balakang Padang (1965)

5. Tanjong Pinang (Till Present)

PAHANG

Johor Pahang Perak , attack Portuguese in Melaka.

Johor-Riau-Lingga Empire16th-18th Century

Portuguese + Johore against Acheh’s attack 1582

1641

Johor Dutch defeated Portuguese in Melaka.

Jambi War 1670

Minangkabau Prince, Raja Kechil, from Siak, took over the throne in Johor1699

Raja Kechil was dethroned, usurped by Bugis’ puppet, Raja Sulaiman1722 Sir Stamford Raffles arrived in Singapore, discovered a small Malay settlement at the mouth of the Singapore River which was headed by a Temenggung (governor) of Johor 1819

Johor's centre of administration was initially based on the mainland of Johor. It then shifted to Bintan Island, and then to Lingga. When the Sultanate split up on 17 March 1824 after the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 the centre of administration was in Singapore. It then shifted to Tanjung Puteri, known today as Johor Bahru. 1824

1866

50 hectare land that produced gambir and pepper

Owned by head planters

Kangchu

A socio-economic system of organization and administration by Chinese agricultural settlers in Johor. The settlers organized themselves into informal associations ‘Kongsi’. In Chinese, ‘Kangchu’ literally means ‘lord of the river’. It was the title given to the Chinese headmen of these river settlements. The ‘Kangchu’ leaders are also called ‘Kapitan’, and their different roles are illustrated:

Chinese from Singapore sought work opportunities as planters in Johor.

Kangkar that existed till 1887

Kangkar that existed till 1893

Other Kangkar that existed till 1904

Kangkar with no proofing source

Kangkar that is used in the modern maps

Johor Government

Letter of River Capitalist Planters

Kongsi (‘Company’)

Letter of River

Planters

Johor Steam Ferry Boat Company began operation in 1875

Causeway opened in 1924

Taukeh

Gambir Pepper

Infastructure Plan of Johor Bahru-Plentong-Pasir Gudang draft structure planning, redrawn from Mukim Plentong and Pasir Gudang Structure Plan, (1983)

Future highway Highway Railway New public transit system Major road

Sub-centre

Goverment reserve

Minor sub-centre

Water catchment area

Neighbourhood centre

Hospital

Bus terminal

Port

Agriculture

Recreation Green belt/forest reserve

Committed housing area Village

Commercial Industry Area suitable for development if services and utilities are provided

Special reserve

Johor Bahru city centre

Nusajaya city centre

District centre

Existing urban footprint

Immediate potential development areas

Future urban footprint

Catalyst employment area

Catalyst neighborhood area

Managed SME industrial park

Green area

Local centre

Multimodel Terminal

Village neighborhood

Aquaculture zone

Agriculture

Special management area

Core conversation area

Airport & seaport

Urban growth boundary

Overall Development Plan Map of Iskandar Malaysia for 2025, redrawn from Regional Land Use Framework, (2007-2025)

Singapore

Historical Maps & Concept Plans

High-density

Commercial areas

Medium-density

Industrial areas

Low-density

Wholesale & Business

Civic centre

Main shopping areas

Residential areas

Rural centres & Settlements

Shopping & Business centres

Industry

Agricultural areas

Green belt & public open areas

Universities & major educational institutions

Dock area

Airfield

Other uses

City centre

Housing

Industry & Business

Concept Plan of Singapore - The Otto Koenigsberger Plan (Ring City) redrawn from UNDP (1963)

Water catchments

Transportation by rail

Transportation by sea

Catchment areas

Airfield Expressway

Proposed rapid mass transit system

Proposed new city centres

Proposed high-density urbanised area, New cities

Proposed industrial area, New cities

Singapore city area, (T.M.A)

Regional parkland & green belt agriculture

Low-density residential

High-density residential

Industry, Harbours

Commercial centres

Catchment areas

Open spaces

Coastal recreational areas

Rural areas

Institutional uses

Expressways

Airports

Mass Rapid Transit

New city centres

High-density urbanised area

Industrial area

Green belt, Agriculture

Military land

Airfield

Singapore city area

Rural centres & settlements

Major roads

Rail

Residential

Rural centres & Settlements

Shopping & Business Centres

Industry

Agricultural areas

Universities & major educational institutes

Dock areas

Airfields

Comprehensive development areas

Other areas

Green belt & Open spaces

Water catchment areas

Boundary of town map area

Boundaries of new towns & additional town map areas

Commercial

Residential

Utilities or telecommunications

Open spaces

Institutional

Cemeteries

Warehousing

Industry

Quarrying or Mining

Transportation

Reservoirs or water catchments

Agriculture

Vacant land or under construction

Special uses

Residential

Rural centres & Settlements

Shopping & Business centres

Industry

Agricultural Green belt & Open spaces

Water catchment

Tertiary & major educational

Dock or port

Airports or Airfields

Comprehensive development

Other areas

Boundary of town map

Boundaries of new towns & additional town map

Urban centres

Urban District

High-density residential area

Industries

Main public transportation routes

Expressways

High-intensity development

Green open spaces

Central area

Regional centre

Sub-regional centre

Expressways

Mass Rapid Transit

Residential

Commercial Industry

Business park

Institution

Central area

Open space/ Recreation

Special use

Port/ Airport

Infrastructure

Expressways

Mass Rapid Transit

Residential

Institution

Commercial Industry/ Business Agriculture

Open space/ Recreation

Infrastructure

Special use

Reserve site

Possible future reclamation

Road

Rail

Batam

Historical Maps & Concept Plans

SINGAPORE METROPOLITAN REGION

The Peripheral Corridor

FILTERED COSMOPOLITANISM AND SOUTHEAST ASIA

Dr. Lai Chee Kien Assistant Professor Department of Architecture National University of SingaporeHuman movement across the land and liquid areas known as Southeast Asia had been occurring for several millennia since the last Ice Age. They took into account the terrain and landscape features suitable for human habitation and made use of land bridges that have since been submerged by sea water. Austronesian cosmopolitanism was effected via development of sailing craft, chiefly outrigger canoes, that witnessed southward migration towards the Philippines and Borneo from the Asian continent and subsequently eastwards towards Polynesia. The age of classical empires and commerce strengthened religious and political affiliations alongside the establishment of resource networks and trade patterns prior to the advent of the western imperial age. The galactic polities that were created and the strong rulers within them created centres with concentric realms of governance, but not borders that restricted travel between such polities. The rise and fall, and sometimes continuity or obliteration of these centripetal polities and their operational proto-urban centres, are the historical narratives mapped over the regional landscape. This short essay attempts to map the changing nature of cosmopolitanism peculiar to the region, over a long durée.

From 1511 and with the capture of Malacca by Portugal, the region witnessed the realignment of importance played by coastal conurbations and their development to support colonial rule and economics. For example, Singapore’s role was raised in place of Johor Lama in the erstwhile Johor-Riau Empire and attracted migration from elsewhere, chiefly from China and India. The plural society that J.S. Furnivall propounded segregated ethnic groups into respective enclaves as well as smaller sub-enclaves to form the artificial landscape in support of the intense form of capitalism where local folks only met in the markets and production areas, but not socially or culturally. Outside the towns, the jungles were tamed to yield plantations and mining landscapes.

Spatially, the different colonies began their gradual demarcations of their domains with borders. For example, the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 delineated the border which eventually became the international boundary between Singapore and Indonesia. After the post-World War II period and decolonization, states with marked borders developed along prior colonial histories. The colonial era in Southeast Asia thus created primate cities (c.f. Terry McGee) that assumed importance and size over other neighbouring cities, be they capital cities or important economic sites. Alongside such primacy to particular cities was a graduation of areas around them into smaller towns and villages, of lesser or secondary importance, and connected by colonial infrastructure of roads, rail and water channels. This is the constellational spatial network that Southeast Asia had “inherited.”

The intense post-war national period experienced by different countries that ended around the 1970s, was followed by post-national pursuits to reconnect them economically with global financial flows. This next developmental phase further structured internal landscapes within respective countries, but which precipitated mega-urban regions around primate cities while local infrastructure was further recalibrated them. By 2002, McGee “upgraded” the primate city model to that of nodes of global cities and secondary cities with apron conurbations of mega-urban regions, and to capture the changing operational dynamics of regions in the world.

The national border that hindered and limited the myriad forms of cosmopolitanism from ancient times was also exposed in many ways since they were created post-1945. In the 1990s, the formation of the Growth Triangles by respective governments of Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia was meant to enhance economic co-operation between Singapore, Johore and Riau, with more of such triangles developed in the next two decades and between different governments. Prior to this, the relaxing of restrictions to multi-national companies to set up branches, bases and factories in Southeast Asian countries overlapped earlier social and trade links despite of the very borders. Come

2015, the ASEAN Economic Community will pave the way for the free flow of professional labour across the countries including architects and doctors, and will encourage further permeability at the customs. By that time, the filtered form of cosmopolitanism will have replaced the rigid control over movement within the region and internationally, during the national period. The position of Singapore as the global node for the larger mega-urban region will not only be reinforced, but also tested.

Barelang

Galang| 80sq km

SEGAMAT

MERSING

JOHOR BAHRU DISTRICT IN 2009

= Johor Bahru District + Kulai District

JOHOR BAHRU DISTRICT IN 2010

ISKANDAR MASTERPLAN

= Johor Bahru District +

Kulaijaya District +

Part of Pontian District

PENANG

Agong: Mizan Zainal Abidin

Prime Minister: Najib Tun Razak

Johor Sultan: Sultan Ibrahim Ibni Almarhum Sultan Iskandar

Menteri Besar: Y.A.B. Dato’ Haji Abdul Ghani bin Othman

Johor Executive Council

Johor State Government Secretary Office

Johor State Departments And Agencies

Johor Bahru City Council (MBJB)

Datuk Bandar (Mayor): Tuan Haji Burhan bin Amin

Land Office of Johor

Department of Town and Country Planning State Johor (Johor JPBD)

Johor & Malaysia’s administrative structure

Yang Di-Pertuan Agong

Executive Legislature

Parliament SenateAuditor-general House of Representative

Sultan Yang Dipertuan Negeri (Rulers of State)

Menteri Besar (State Chief Minister)

Prime Minister Cabinet Ministries

Min. of Housing and Local Government

Conference of Rulers

Judiciary

Supreme Court

High Court in Peninsular Malaysia

High Court in Sabah and Sarawak

Executive Council (Exco)

Exco Committees

State action council

State security committee

State Secretary’s Office

Branches of Federal Agencies State Agencies

Local Authorities Land and District Office

Branches of State Agencies

Branches of Federal Agencies

Penghulu’s Office

Town & Country Planning Department

State development committee

Commissions

Election commission

Judicial and Legal Services Commission

Police Force commission

Public Service Commission

Education Service Commision

Local Government Division

Other Departments

Local Government Division (state level)

Town & Country Planning Department (state level)

District Action Committee

Mukim Development and Security Committee

Kampung Development and Village Headman

Security Committee

District Security Committee

District Development Committee

Kulaijaya

Johor Bahru

West Malaysia The State of Johor Divistion of Districts in 2009

Johor Bahru District 2009

District into Mukim-mukim (Subdistricts)

Kulaijaya becomes an independent district in 2010

Johor Bahru District 2010

2-hour drive*

83 km ring road from Singapore to JB boundary traverses Nusajaya 15-minute drive*

*

Johor - Singapore Causeway | 1920m

Malaysia - Singapore Second Link | 1056m

Batam - Tonton Island | 642m

Tonton Island - Nipah Island | 420m

Nipah Island - Setoko Island | 270m

Seteko Island - Rempang Island | 365m

Rempand Island - Galang Island | 385m

Galang Island - Galang Bahru Island | 180m

Kukup

Stulang Laut

Tanjung Belungkor

Desaru

Harbourfront Centre

Marina South Pier

Changi

Tanah Merah

Sebana Cove

Tanjung Pengelih Pengerang

Sungai Rengit

Nongsa Pura

Sekupang

Batu Ampar

Batam Centre

Bandar Bentan Telani Waterfront City

Telaga Punggur

Tanjung Uban Tanjung Pinang

Current figure - 3.28 million

Current figure - 3.31 million

Postulated figure - 5.5 million

Current figure - 1.03 million

Current figure - 0.17 million

Current figure - 5.18 million

Postulated figure - 6.5 million

Total current figure for SMR ≈ 14 million

Current figure - 1.04 million

Postulated figure - 1.7 million

Figures of current population & postulated population in 20 years

7.3% growth

14.1% growth

7% growth

US$

49,780 US$

Total Imports in 2010 = 330,189 million USD

12345678910

Total Exports in 2010 = 373,659 million USD 12345678910

Total Imports in 2010 = 7,688 million USD

12345678910

Total Exports in 2010 = 373,659 million USD

12345678910

Smuggled goods include: Logging Products Sand Mining Agricultural products eg: banned products, foreign rice Duty free goods

Wildlife Prostitutes Traditional trade between bonded and non-bonded islands

intervillagetraditionaltrading(legal)

TAP 2 IMPORTED SOURCE (million gallon per day)

Linggiu Scheme 1990 water agreement

Johor River

Tebrau River Skudai River

Johor River Scheme 1962 water agreement 250 mgd (1,140,000 m3)

Tebrau and Skudai River Scheme 1961 water agreement (expired) 4 mgd (18,184m3)

Gunung Pulai Scheme 1927 water agreement (expired) 12 mgd (5,455m3)

Consumption:

Import treated water from Linggiu Dam Imported Water from Johor 150 mgd (681,914 million m3)

TAP 3: NEWATER (Capacity: 122 mg)

NEWater Plant A 17 mg (77,283 m3)

NEWater Plant B 5 mg (22,730 m3)

NEWater Plant C 32 mg (145,474 m3)

NEWater Plant D 18 mg (81,829 m3)

NEWater Plant E 50 mg (227,304 m3)

TAP 4: DESALINATED WATER (Capacity: 30 mgd)

Tuas SingSpring Desalination Plant 30

(136,382 m3)

mg = imperial million gallons

mgd = imperial million gallons per day

Main Water Source in Batam

RESERVOIRS

total capacity: 22,993mg (101,290,000m3)

A. Sei Harapan 792mg (3,600,000m3)

B. Sei Ladi 2,088mg (9,490,000m3)

C. Sei Baloi 59mg (270,000m3)

D. Muka Kuning 2,699mg (12,270,000m3)

E. Duriankang 17,197mg (78,180,000m3)

F. Sei Nongsa 158mg (720,000m3)

mg = imperial million gallons mgd = imperial million gallons per day

Main Water Source in Johor Bahru

TAP 1: RIVERS

1. Sungai Pulai

2. Sungai Skudai

3. Sungai Tebrau

4. Sungair Johore

5. Sungai Layang-layang

TAP 2: RESERVOIRS

6. Takungan Air Sultan Iskandar

7. Gunung Pulai Besar

TAP 3: Singapore Treated Water

Segamat Jackfruit, Starfruit, Mango, Orange, Durian, Palm Oil

Muar Fruits, Palm Oil, Poultry Farm, Pig Farm

Parit Jawa Oyster, Fish, Dragon Fruit, Pineapple, Paddy

Batu Pahat Pineapple, Banana, Palm Oil, Durian, Poultry Farm, Pig Farm

Simpang Renggam Pineapple

Pekan Nenas Pineapple, Durian, Poultry Farm, Egg

Pulai Vegetable

Pontian Pineapple, Coconut, Padi, Palm Oil, Kuini Fruit, Mushroom, Banana, Tapioca and Sugar Cane Cattle Farm, Poultry Farm

Pulau Kukup Fish Products

Tanjung Piai Coffee, Mixed Fruits, Palm Oil, Honey, Fish

Serkat Coffee, Corn, Palm Oil, Banana

Watermelon, orange, roselle tea, starfruit Rompin

Fruits, Vegetables, Palm Oil Endau

Watermelon, orange, roselle tea, starfruit Mersing

Dragon Fruit, Organic Vegetable, Organic Rice, Pineapple, Tea, Spinach, Cabbage, Long Beans, Sweet Potato, Cassava and Maize Kluang Cattle Farm

Cattle, Duck Farm Layang-layang

Watermelon, Orange, Roselle Tea, Starfruit, Mushroom, Fish Kota Tinggi

Starfruit, Jackfruit, Soursop, Honey, Orange, Durian Desaru

Egg, Pig Farm, Poultry Farm Skudai

Bird Nest, Fish, Palm Oil, Buah Jarak, Fruit (Durian, Rambutan, Mango) Pengerang

United States Beef

Chicken Duck

Fish Fruit

Pork Rice

Vegetable

Brazil

Beef

Chicken

Fruit Sugar

France

Chicken Duck Fish Fruit Pork

Vegetable Milk

Netherlands

Chicken Pork

Vegetable

Fruit

India Fish Fruit Rice

Sugar

Vegetable

China

Cooking Oil

Fish

Fruits

Pork Rice Sugar

Vegetable

Vietnam Fish Fruit Rice

Sugar

Vegetable

Australia

Beef

Fish

Fruit

Mutton

Pork

Rice

Sugar

Vegetable

Milk

New Zealand

Beef

Egg

Fish

Fruits

Mutton

Vegetable

Thailand

Fish Fruit

Rice Sugar

Vegetable

Pulau Bulan

Pork

Crocodile

Malaysia

Chicken

Cooking Oil

Duck Egg Fish

Fruit Sugar

Vegetable

Thailand Sugar Rice (illegal trading)

Vietnam Rice (illegal trading)

Sumatra Flour, Cooking Oil, Egg, Vegetable, Chilli, Potato, Onion

Riau Islands Fish, Prawn, Crab and other marine products

Jakarta Rice

Java Cooking Oil, Flour, Egg, Vegetable

≈ 0.22 tons / 200 kg per

- Live Pigs | ≈ 365,000 pigs

Pulau Bulan, Indonesia

- Frozen pork | ≈ 127,273 pigs / 28,000 tons

Australia, Belgium, Canada, China, Denmark, Germany, Hungary, Sweden & USA

- Chilled pork | ≈ 109,091 pigs / 24,000 tons

Major Exporter Australia & Others

1000 pigs daily

Power supply

Power supply

Distri park

Telecommunication nodes

Transmitting/ relay station

Telecommunication

integrated towers

Telecommunication nodes

Type of Material Location

A. Gold Jementah

B. Kaolin Ayer Hitam

C. Bauxite (aluminium) Medan

D. Gold Mersing

E. Tin Kota Tinggi

F. Iron Ore Kota Tinggi

G. Illegal Sand Mining Sungai Johor

H. Silica Sand Pengerang

I. Bauxite Teluk Ramunia (world’s largest bauxite mine)

J. Sand Mining Singapore Strait, Malacca Strait

K. Granite Pulau Babi, Pulau Kundur, Pulau Karimunbesar, Pulau Bintan

L. Tin Pulau Karimunbesar, Pulau Kundur

M. Sand Pulau Bintan, Pulau Batam

Get pass to other cities: 4.3 million/ 15.5 million

Day-tripper: 9.6 million/ 15.5 million

Singapore Tourist: 14.1million /15.5 million

X 2.7 times/ year

Total: 15.5 million (include Singaporean visitors via Causeway and Tuas Link)

Gross Total: 1.4 million

Day-tripper: 2.6 million / 11.64 million

Indonesian Tourist: 2.3 million / 11.64 million

Malaysian Tourist: 1.04 million / 11.64 million (via airport)

Gross Total: 11.64 million (exclude Malaysian visitors via Causeway and Tuas Link) 9.51 million

Johor drug users detected: 2243 annually 0.68%

60.7 % use heroin/morphine (most commonly abused intravenous drug) 1,362 drugs users annually using IV drug usage

EXPORTING URBAN UNIFORMITY WORLDWIDE