AMIDST A CLIMATE CRISIS ENERGETIC INJUSTICE URBAN AGLOMMERATION AND UNBALANCED CAPITALISTIC POWER SCHEMES...

AMIDST A CLIMATE CRISIS ENERGETIC INJUSTICE URBAN AGLOMMERATION AND UNBALANCED CAPITALISTIC POWER SCHEMES...

In 2023, according to the United Nations World Meteorological Organization, the global annual average temperature was nearly 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels

This is due to anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere

The main such gas, carbon dioxide , originates largely from the energy sector

The notion of a linear global transition to net-zero overlooks the complexities of economic development, poverty alleviation, energy security and affordability, which are crucial for the global south

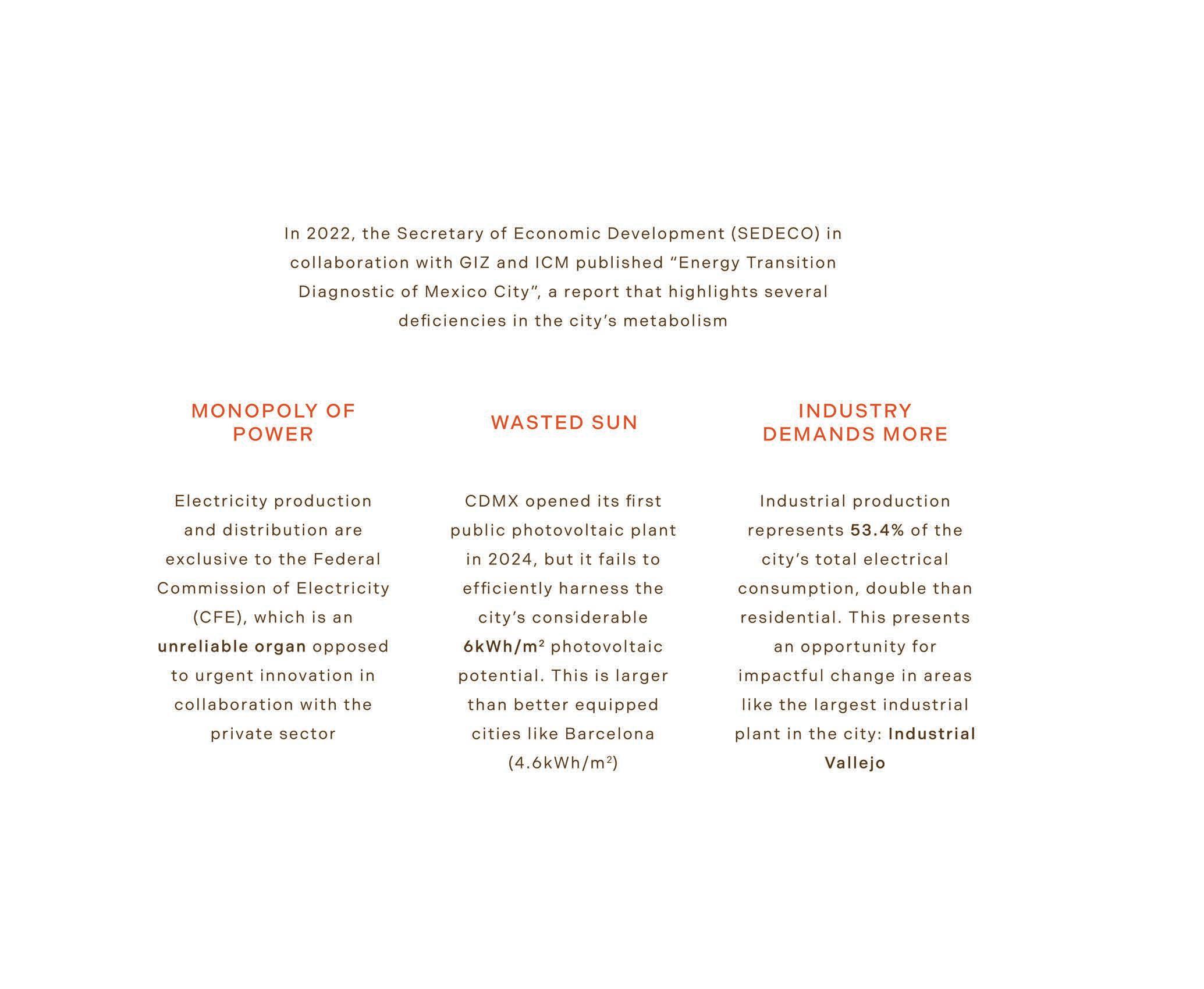

Our country has already repeatedly declared a state of emergency in the electrical system because demand has already caught up with supply and we have been on the verge of severe blackouts

The most important tool to achieve decarbonization is energy transition, which will be a multispeed, multifueled and multi-technology change with different roadmaps and endpoints for different metropolis like CDMX

The energy transition concerns the shift from fossil fuels to renewables energy sources in an effort to reduce CO 2 emissions

The cost of renewable te c hnologies decreased by 83%

Social wellbeing is abundant,

Th e sun and wind only produce around 12% o f the electricity in M ocixe

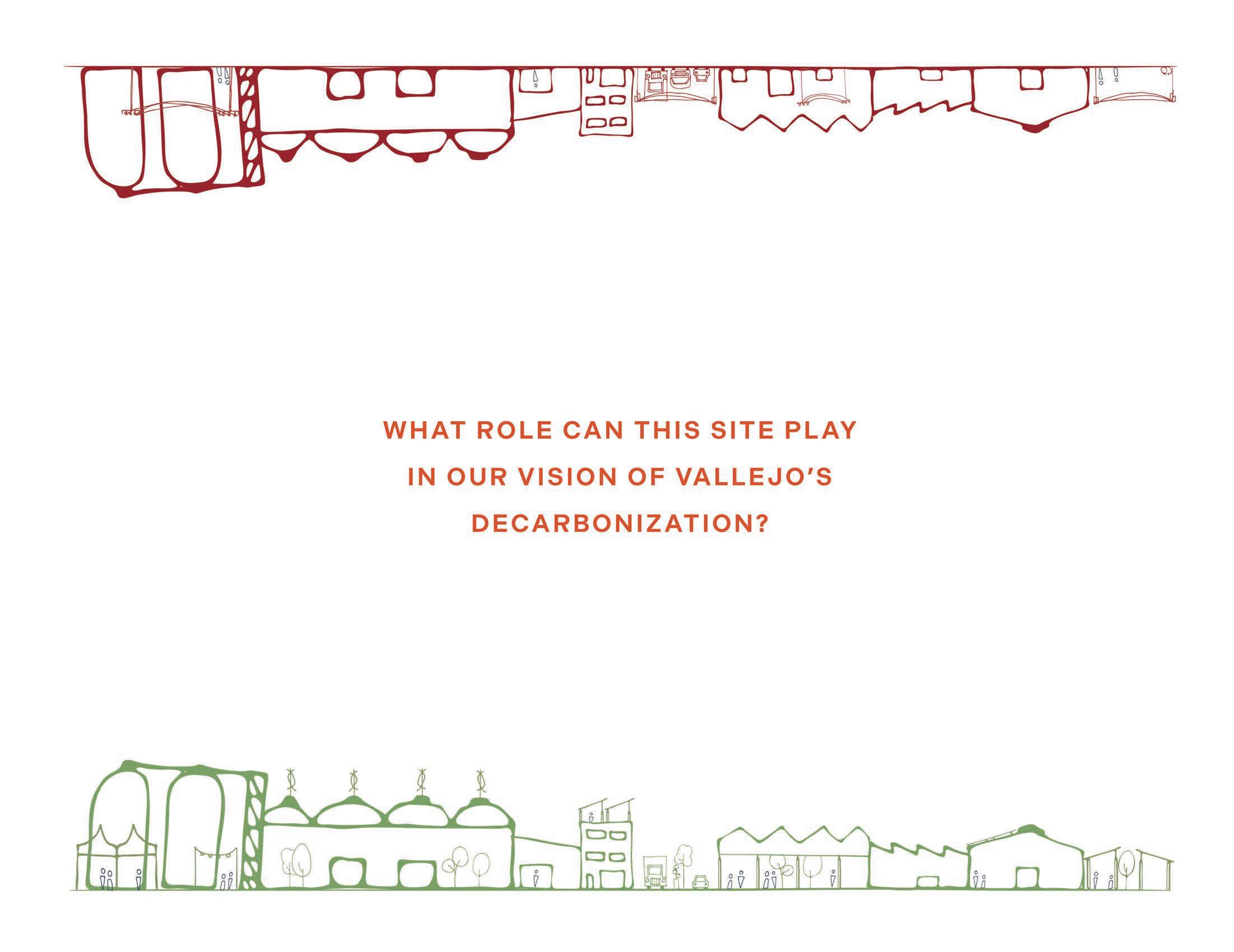

Before Mexico embraced industrialization as an economic vanguard in the mid XX century, the land where Industrial Vallejo stands today was a group of estates and farms property of Antonio Vallejo, located at the far north of Mexico City’s then slowly growing urban sprawl.

In 1934 El Águila, a subsidiary of the Royal Dutch Shell company, opened an oil plant in Azcapotzalco with only a few other neighbor factories. This, along with the massive development of the preexisting railroad paved the way for Vallejo, whose 500 hectares of land use were decreed as exclusively industrial ten years later by president Manuel Ávila Camacho.

Industrial Vallejo grew considerably before the turn of the century due to its concentration of manufacturing enterprises and then the emergence of services for the surrounding neighborhoods.

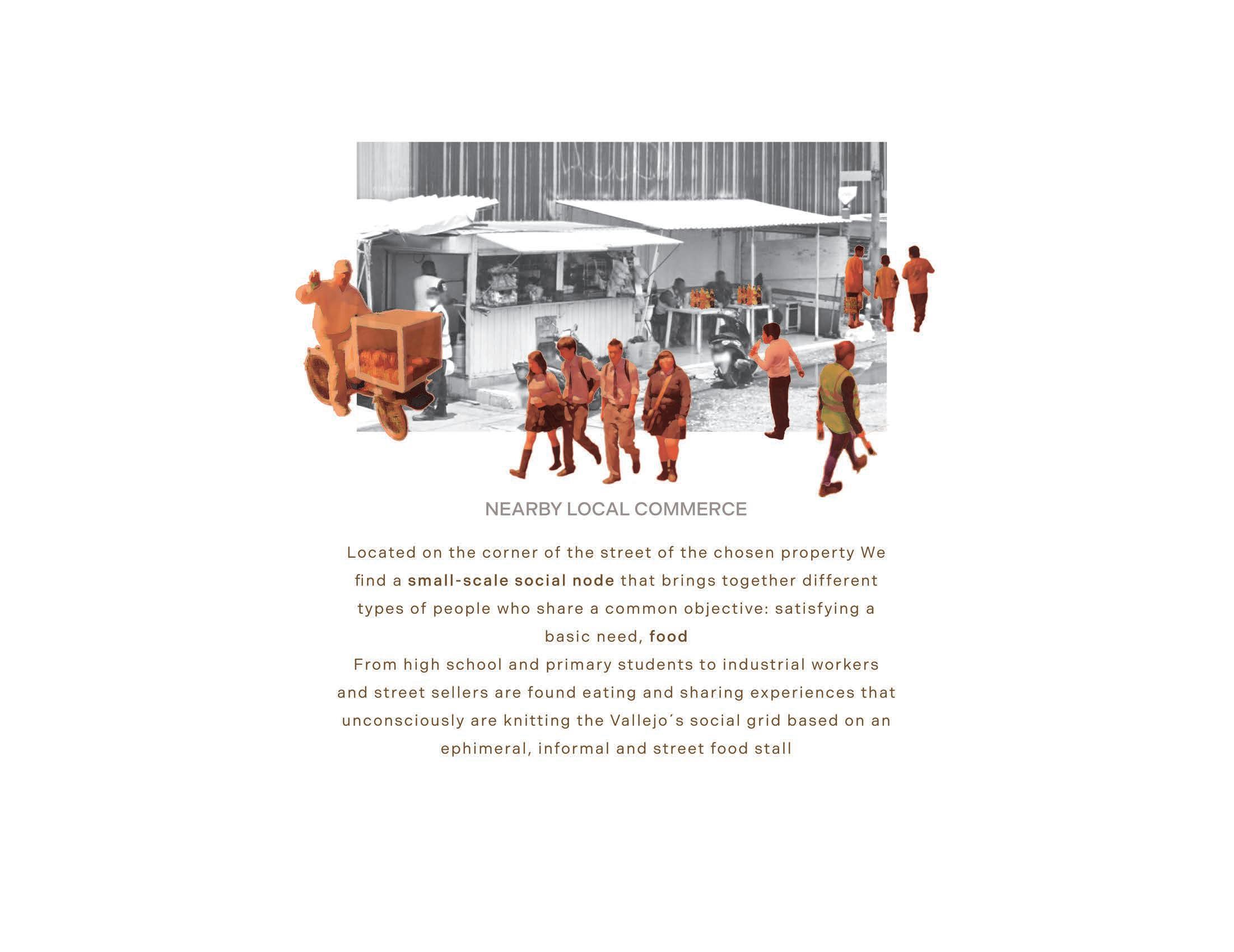

Today, this site is no longer isolated. The city’s aggressive development has caught up and now engulfs Vallejo with freeways, informal housing and other commerce.

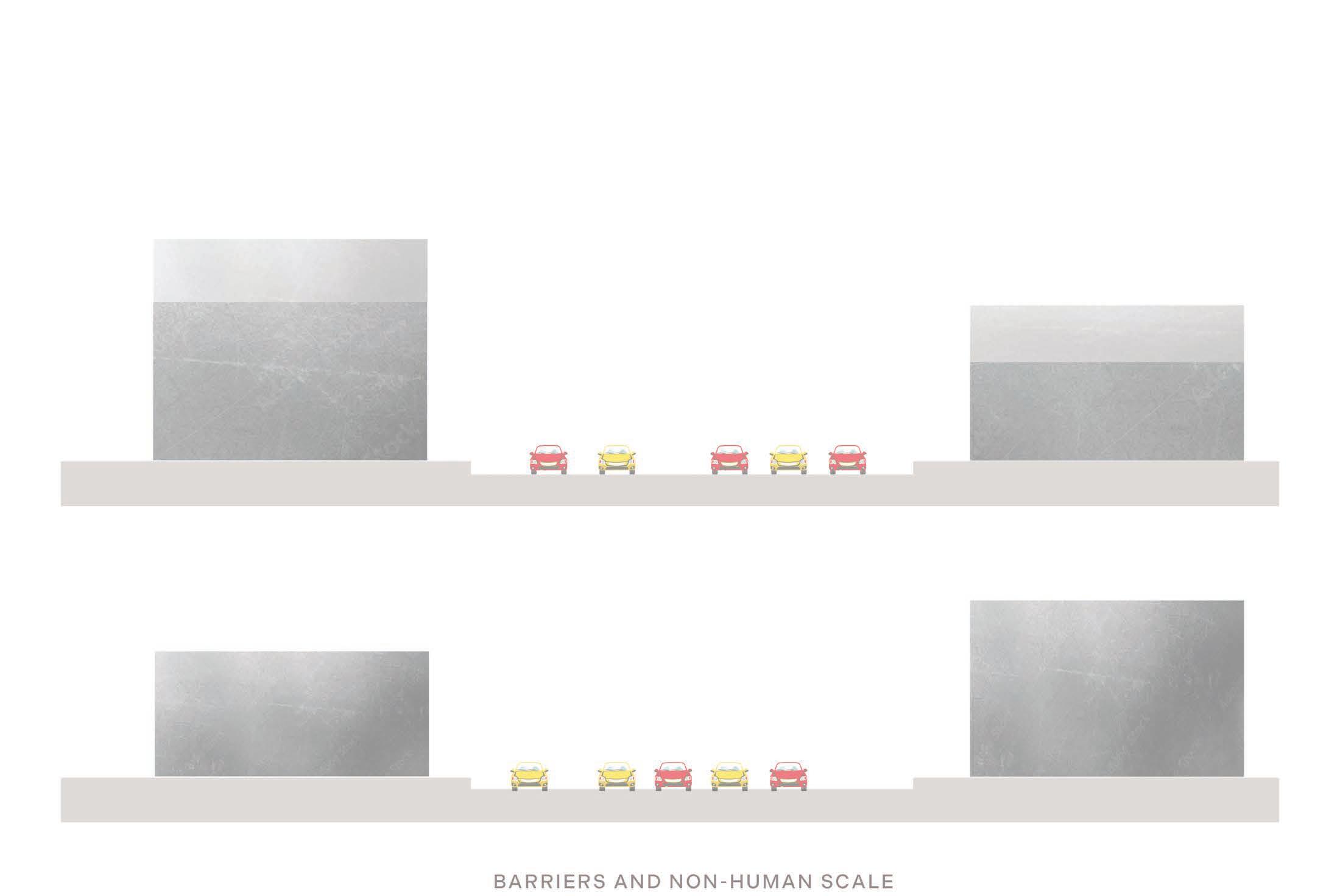

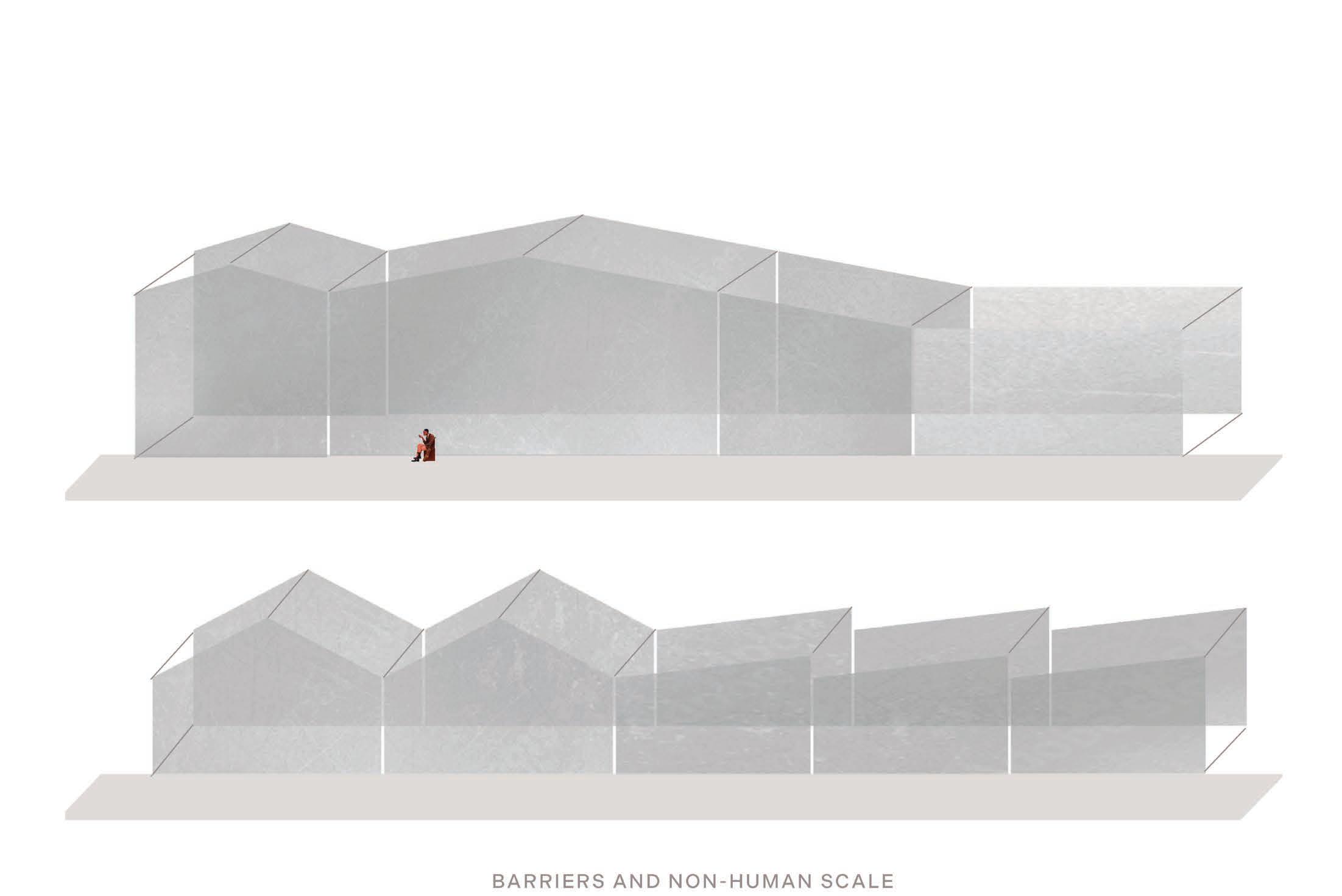

The polygon represents 4.7% of the nation’s manufacturing GDP, with a yearly input akin to 125,000 millions of pesos, harboring several prominent industries. P&G, Cemex, PepsiCo, CocaCola, and LALA among others directly employ 40,000 people but only 5% of them live on-site housing due to a lack of land use diversification. This homogeneous landscape translates into a dehumanized environment.

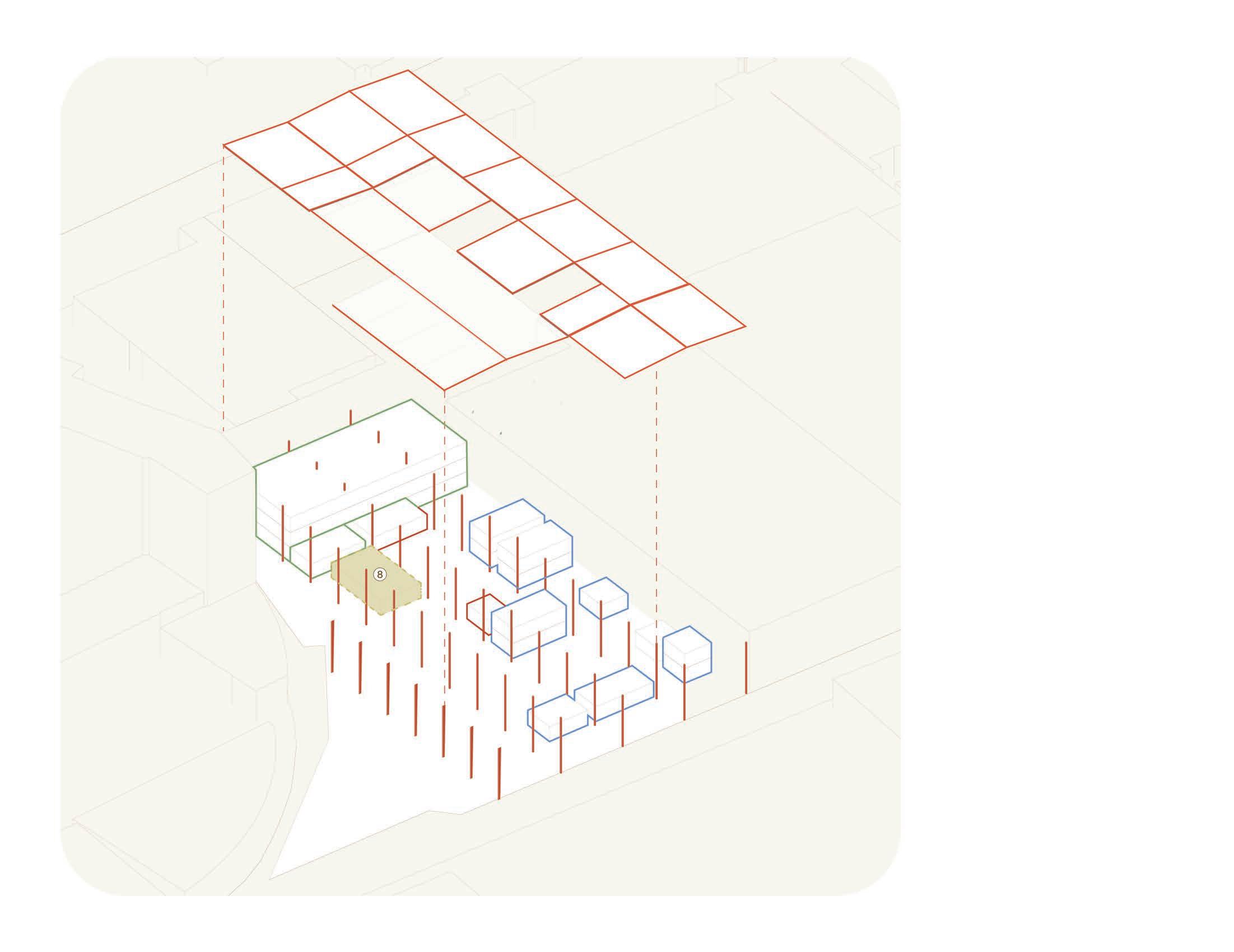

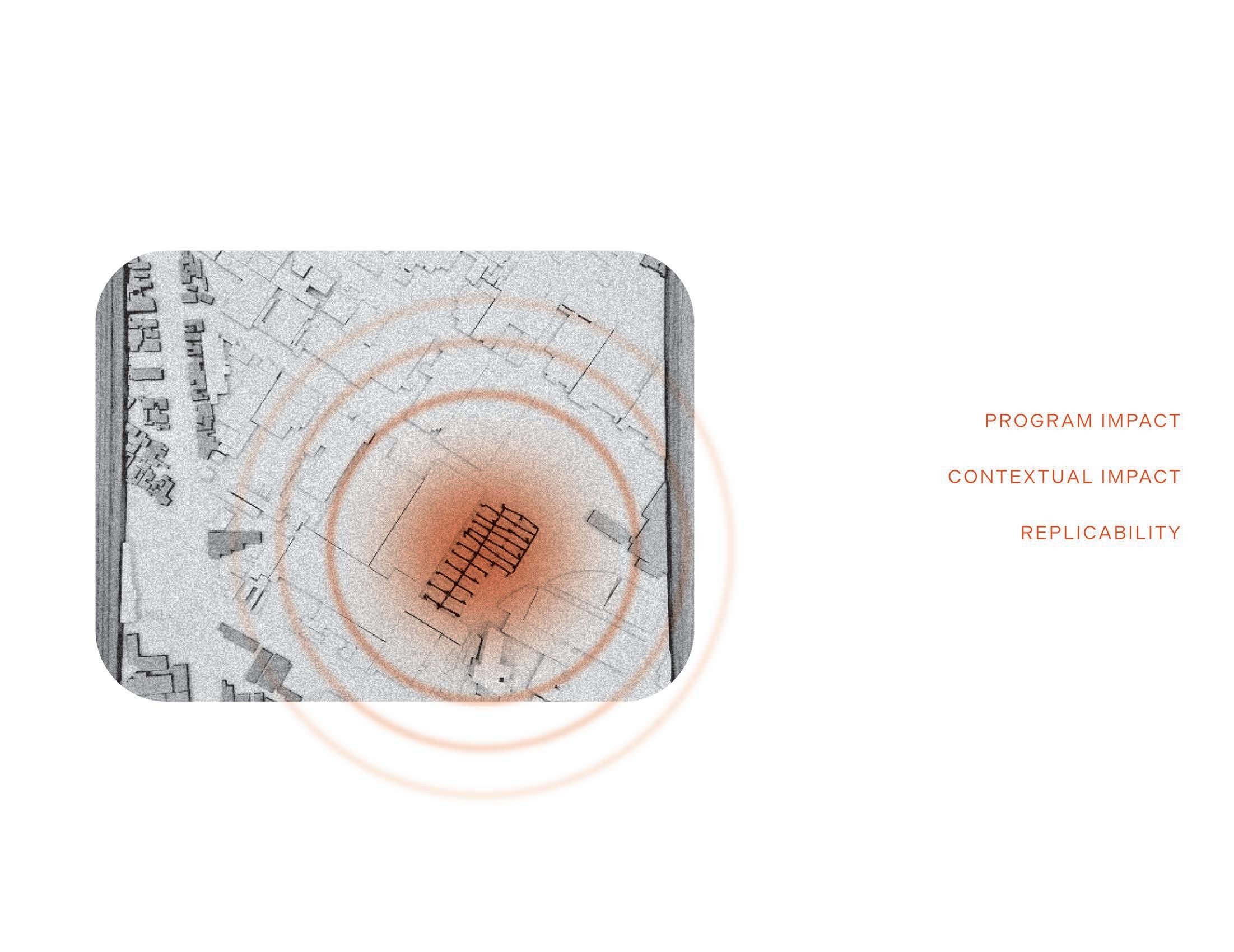

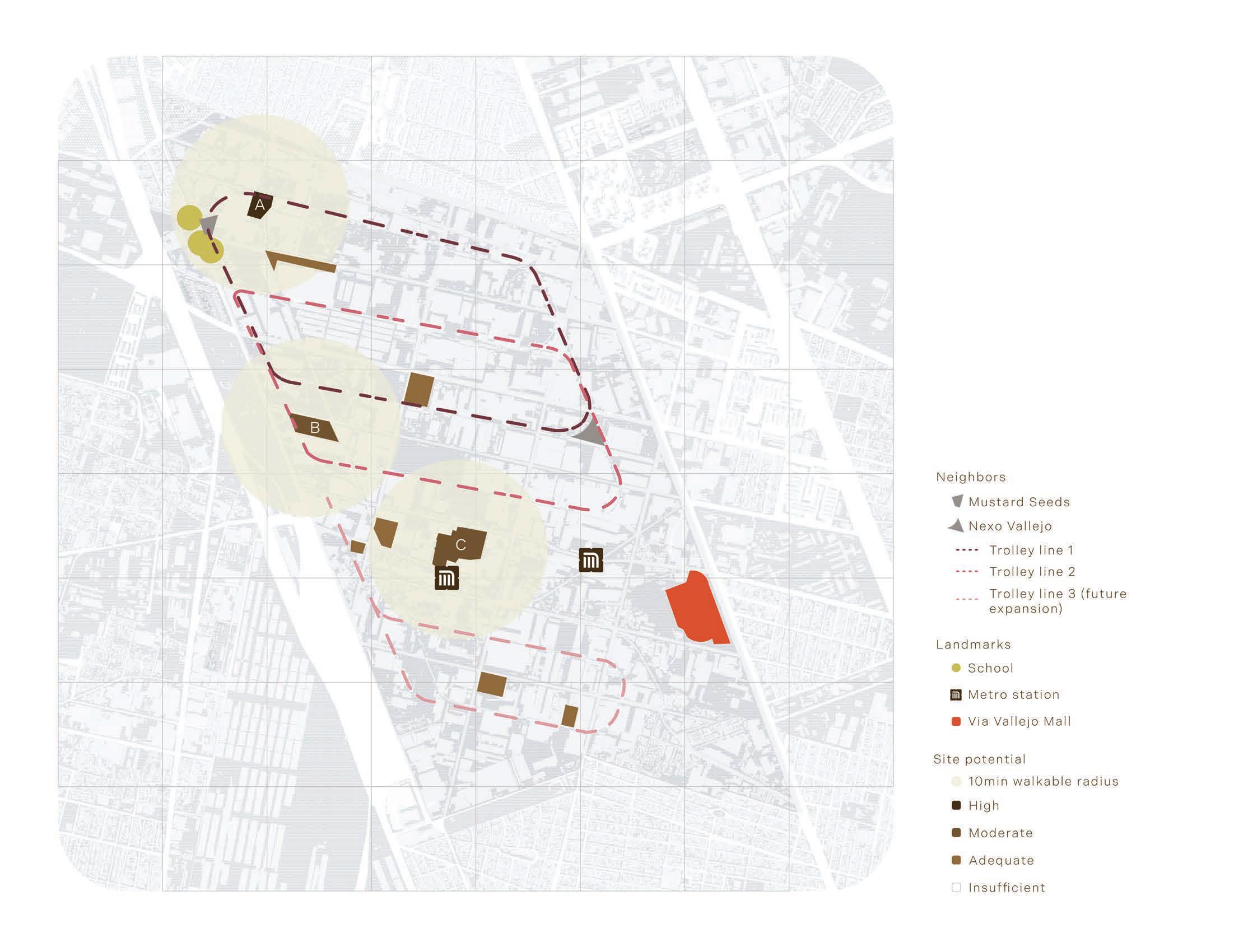

Towards the end of 2018, the city’s government launched Vallejo-I, a public program whose aim is to attract industries and consolidate the most notable innovation cluster in the Valley of Mexico. This includes an effort to renovate local electrical infrastructure but does not promote ambitious measures towards decarbonization, wasting the potential link to Ciudad Solar, the city’s photovoltaic program.

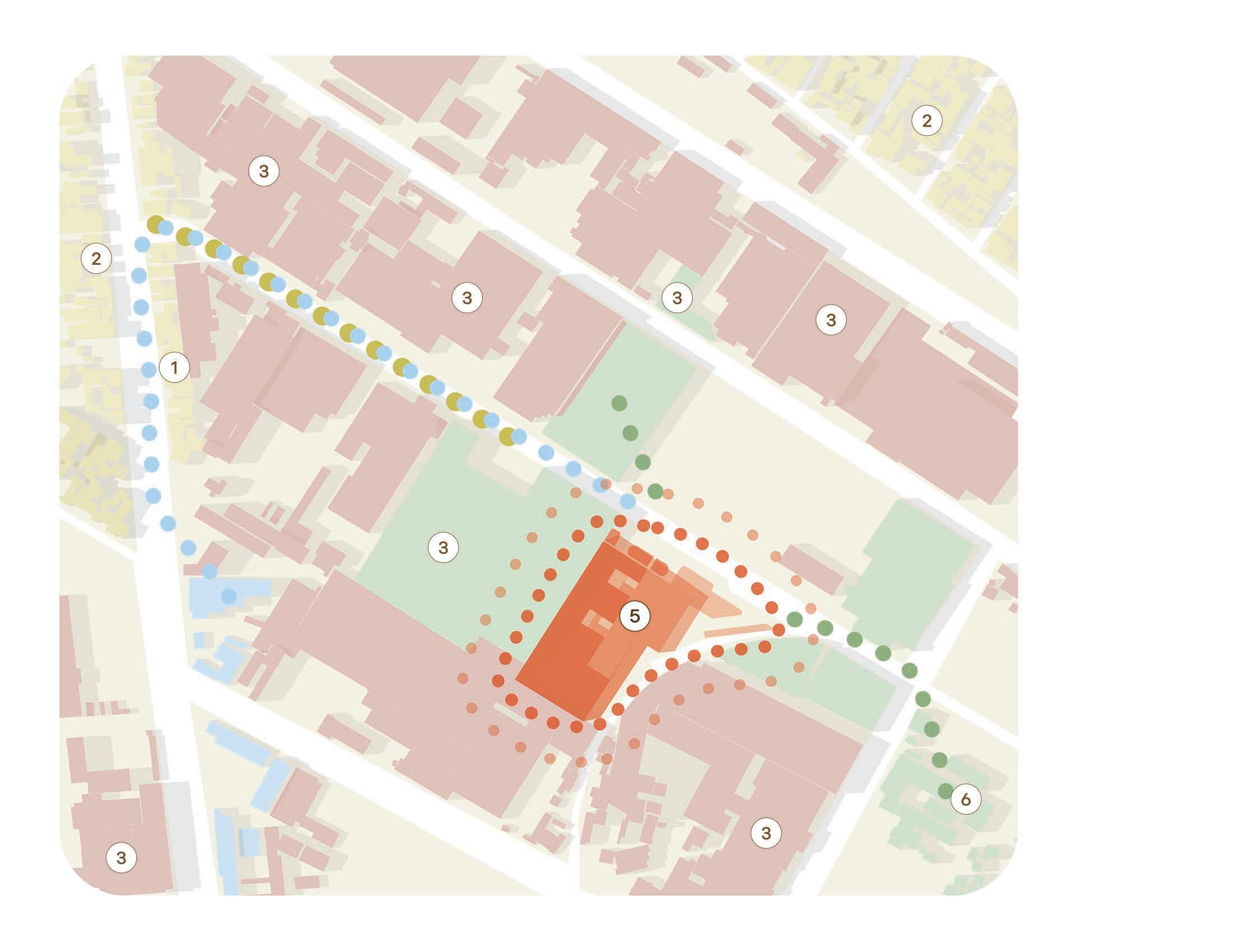

Part of what we identified as a dehumanized industrial scale relates to the lack of walkability within Vallejo. Today, their sidewalks vary in quality but remain constant in the fact that motorized transport dominates the mobility pyramid. This forces workers to traverse through the railroad tracks as a shortcut, even when these are dangerous or uncomfortable.

Even if heavy trailers are constant users of the site’s roads, there are sections such as CAPA’s street where there is no required access and thus can be transformed into a human scale mobility pathway. Safety and comfort are not privileges for pedestrians, they are the bare minimum. A decarbonized Vallejo also implies shifting the reliance on motors and living the street by foot or pedaling.

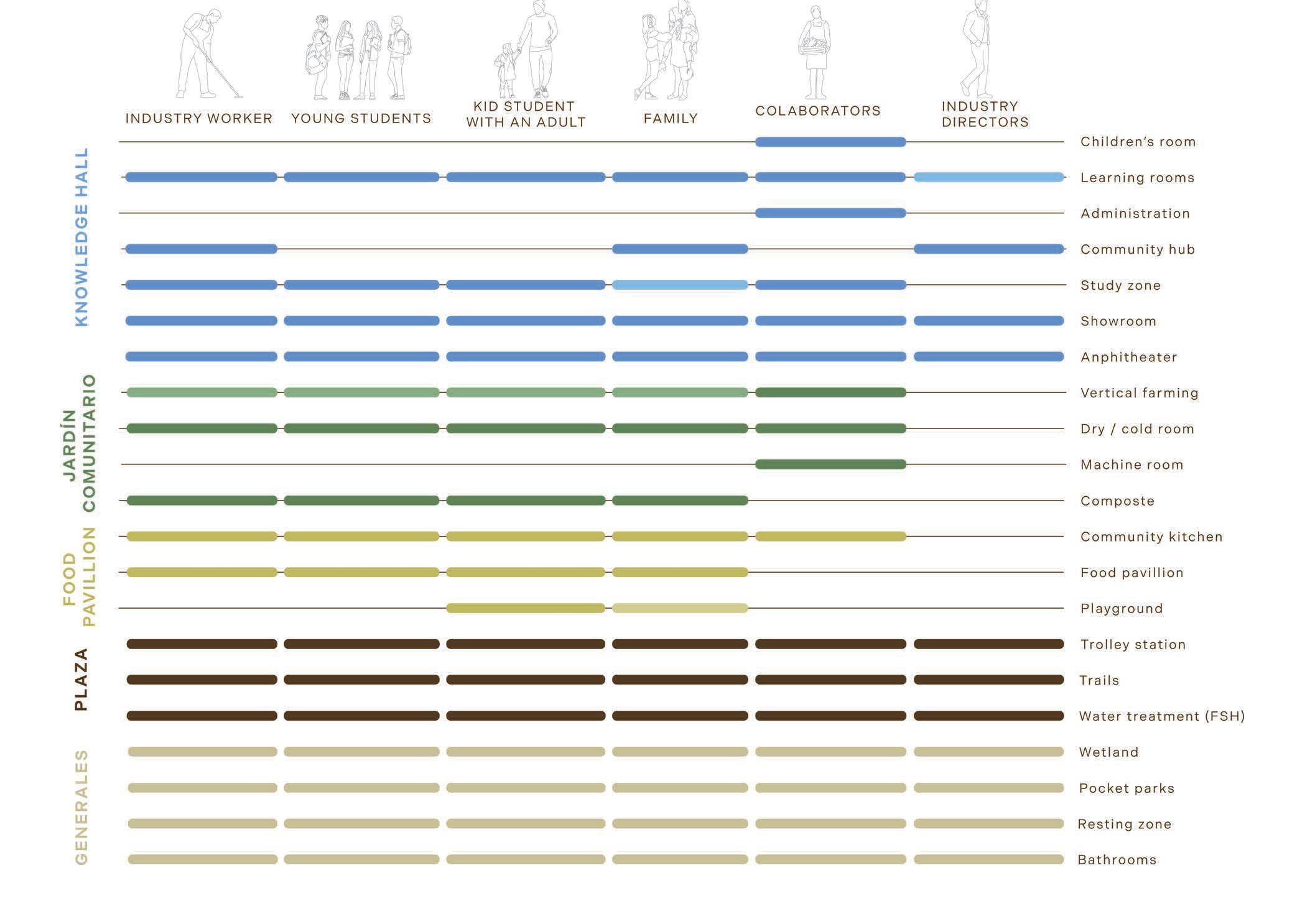

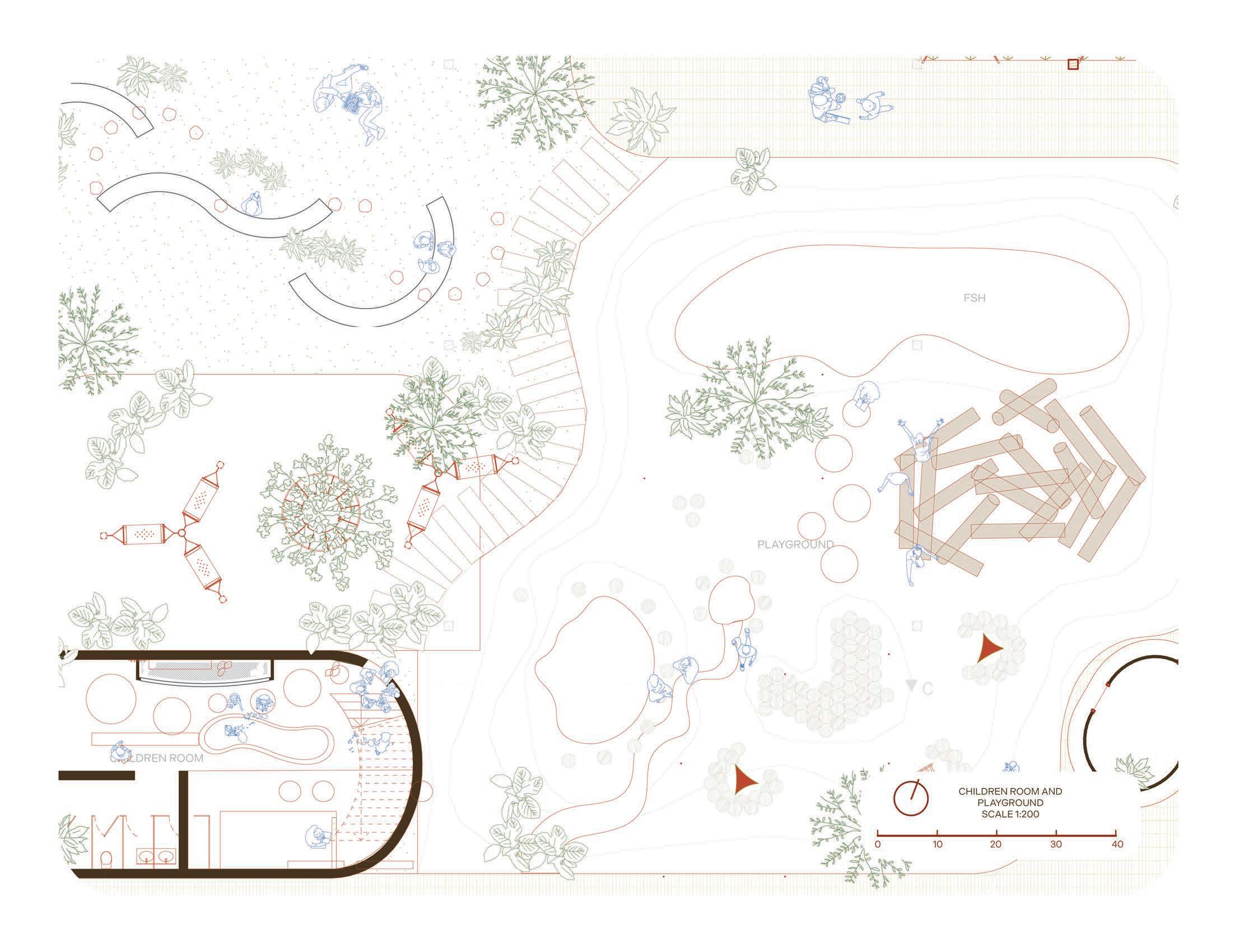

Cecilia is a 9 year old student at Obrero Mexicano Primary. She frequents the childrens’ room and playground as an extracurricular a couple times a week, when her father Héctor picks her up and they both walk to CAPA.

As they arrive, Cecilia checks in with Gracia, the caregiver and waves goodbye to her father as he walks on by towards his afternoon shift at CAPA hydroponics.

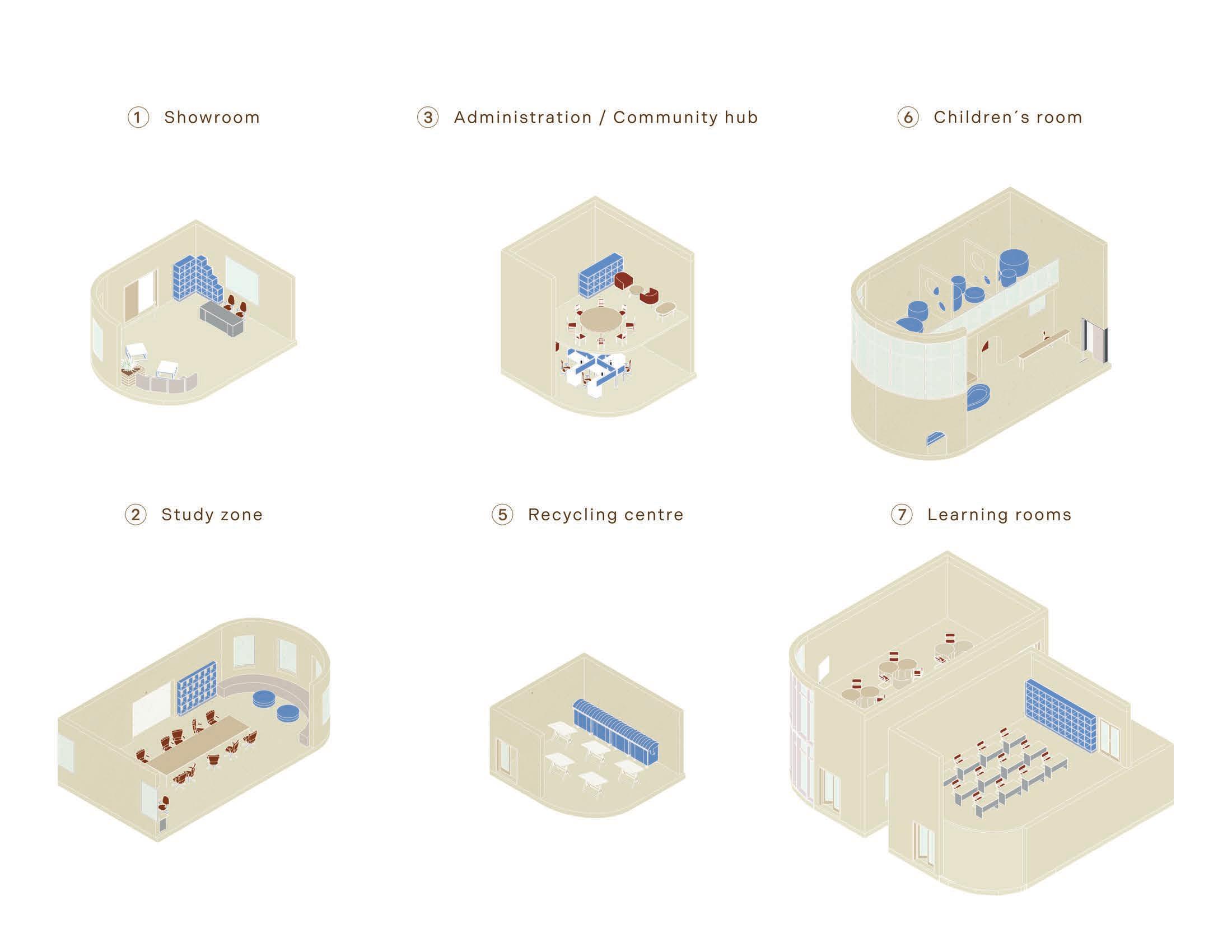

This space is designed to ensure meaningful learning and didactic experiences for children ranging from preschool to secondary ages as complementary education.

Placed at the front of the site near the open study areas and plaza, it is a visible location for those responsible of child users, who can sit to read or enjoy a snack while their young play and learn.

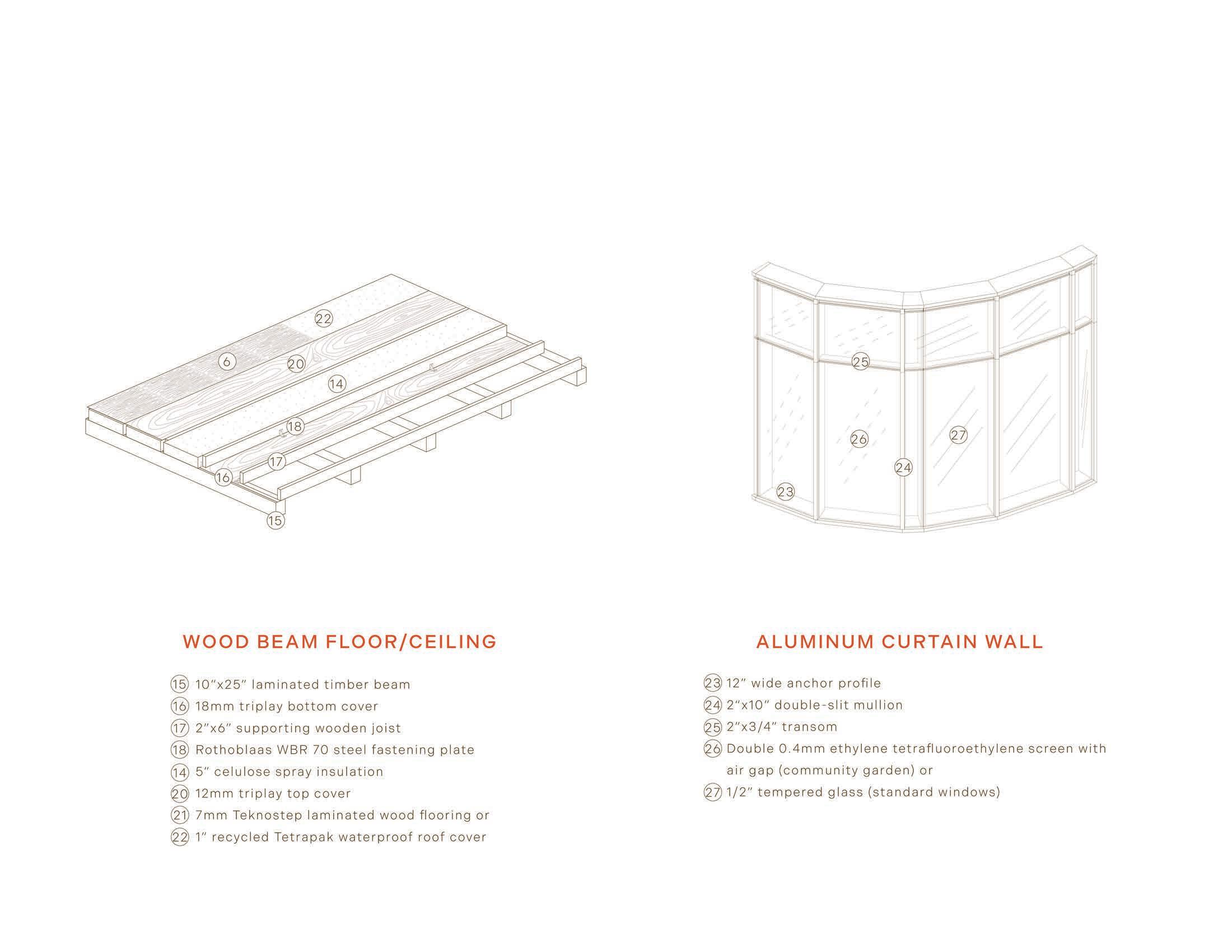

The double-height childrens’ room is furnished with entertaining features such as a small stage, playing islands and a cozy library, as well as a restroom at ground floor. Upstairs, there are three more introspective cubicules where reading or private lessons can be held. The main lighting feature is the enveloping first floor curtain wall that places visual external distractions out of reach.

Outside, the playground awaits with three zones of play aimed towards the skills and challenges of the three stages of childhood.

After leaving his daughter at the childrens’ room and playground, Héctor makes his way towards the community garden for his afternoon shift. Along the way, he passes the recycling center and clasrooms. The path is winding and playful, a comfortable pavement with pockets of tezontle and chipped wood for planting and water infiltration. Just before entering the vertical farm, he takes a moment to take in the view at the wild garden.

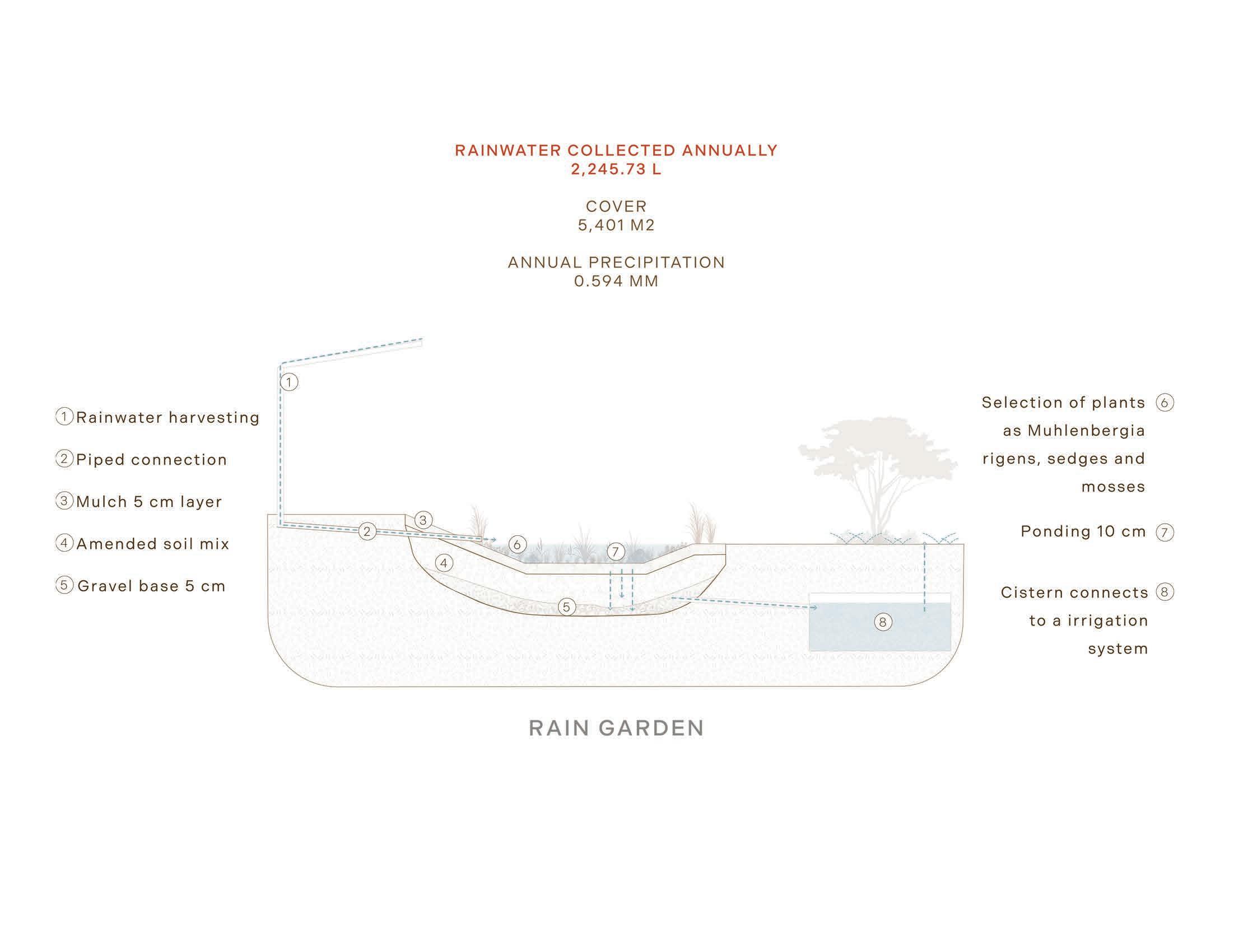

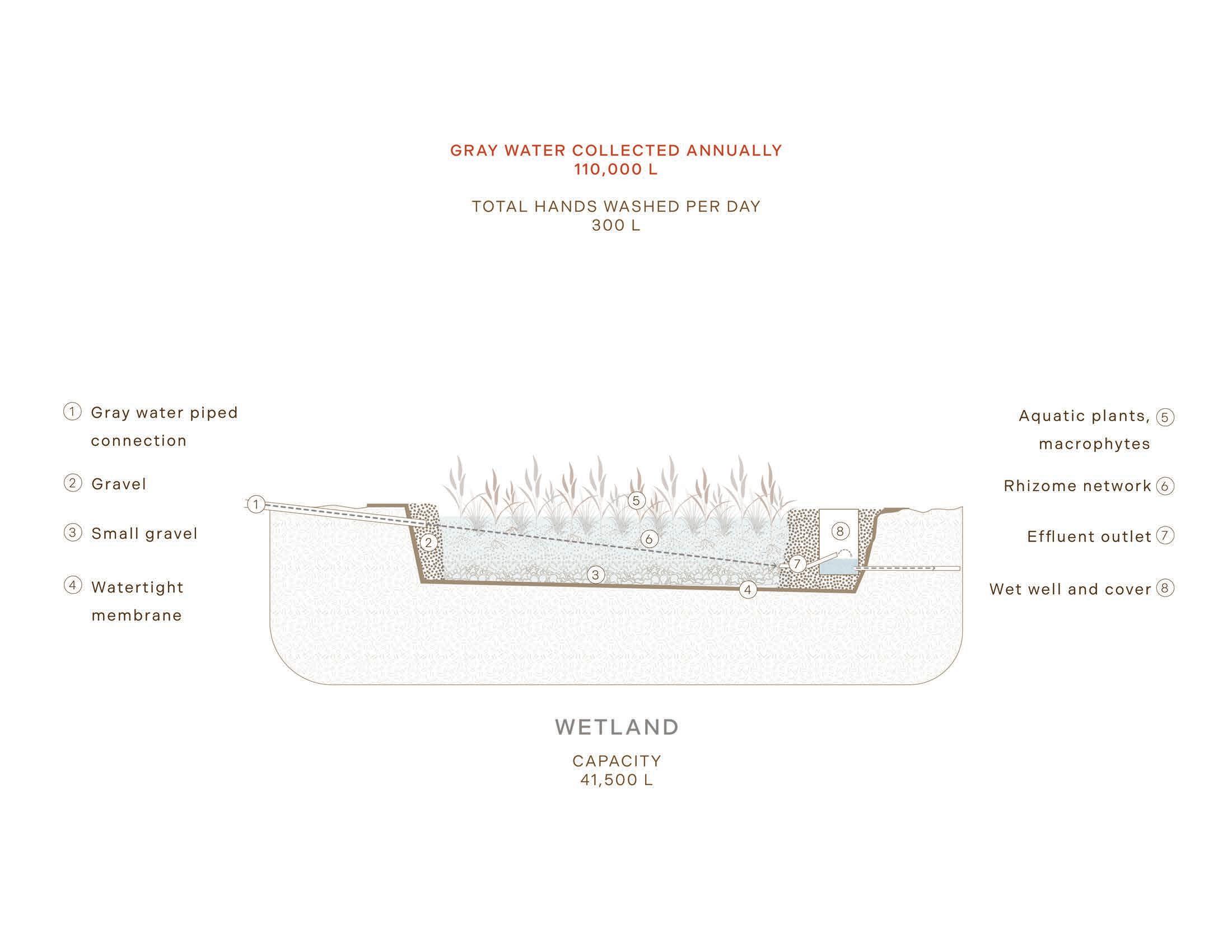

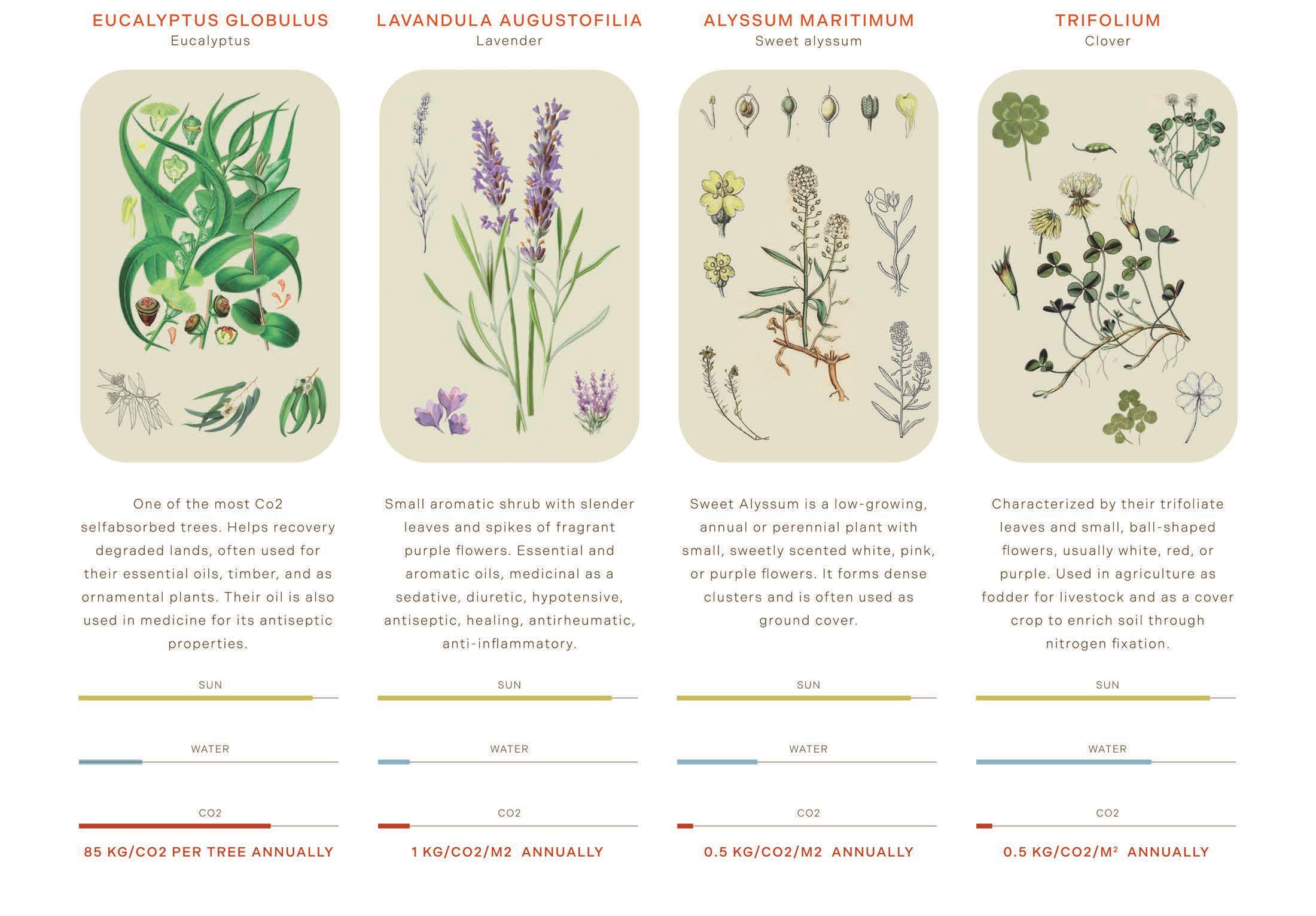

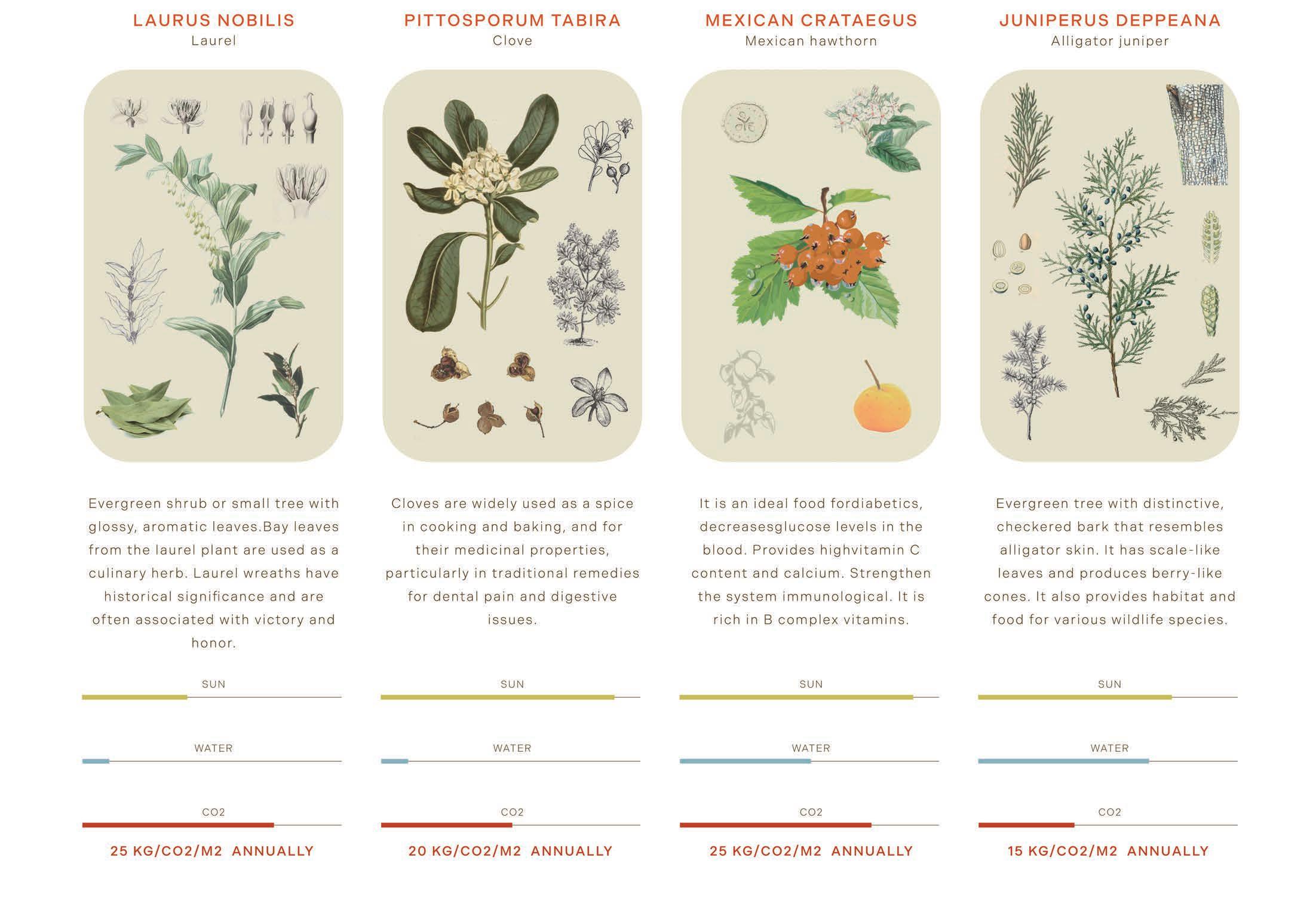

This lush uncovered island represents CAPA’s compromise in aiding nature’s reclaim of the city’s harsh urban context. Today, Vallejo lacks 65.8 hectares of green space according to the WHO’s recommendation of 16m 2 of green space per person. Access to nature is crucial for people’s wellbeing and can become part of a larger landscaping strategy involving CO 2 absorption, air filtration, water infiltration and temperature reduction.

Here, a large blue eucalyptus with formidable carbon sequestration capacity, towers over the community kitchen and provides a space for gathering and resting. Héctor has laid to read in the lawn more than once in between shifts, and is happy to find himself immersed in nature even in the middle of the city.

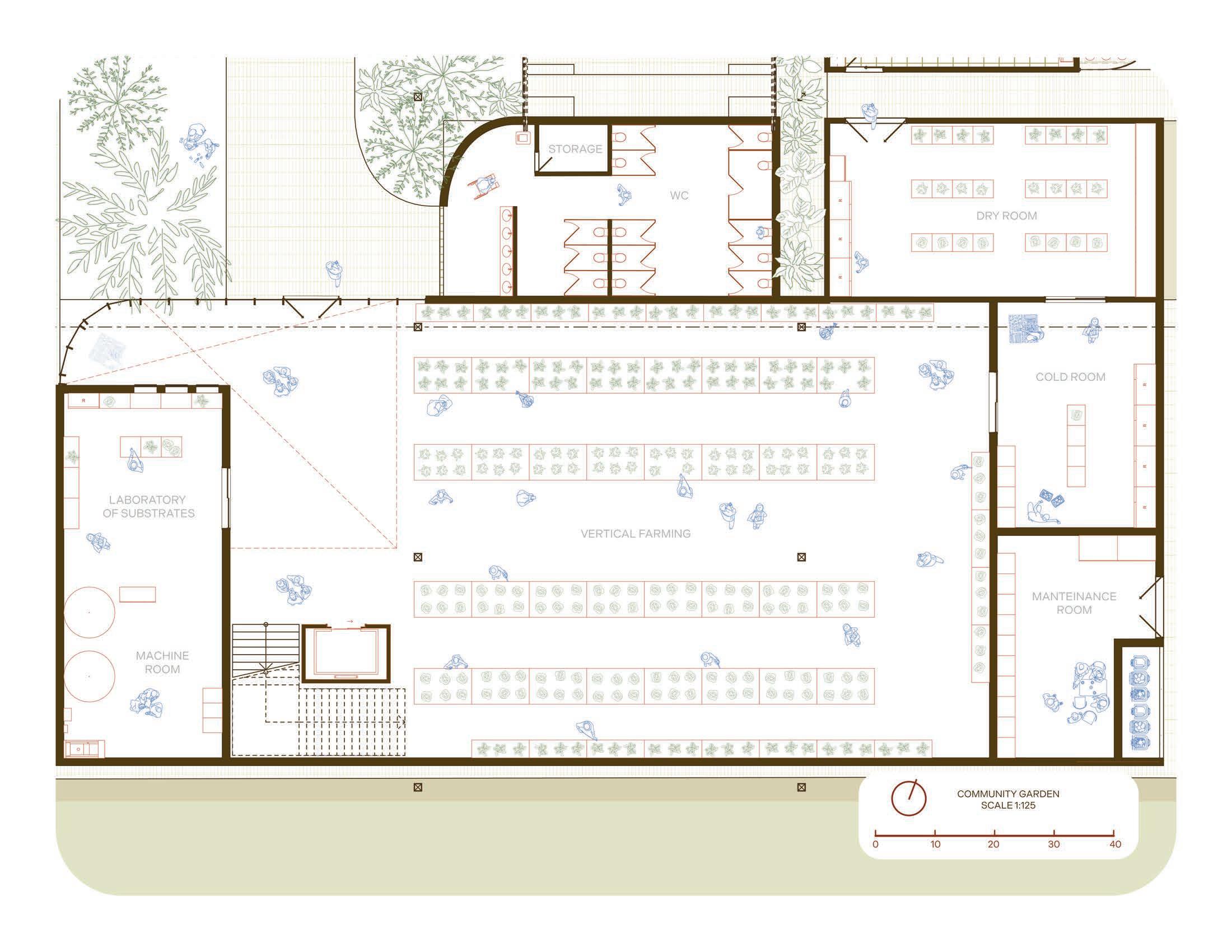

Héctor is an agricultural engineer working as a general manager at CAPA hydroponics. He is in charge of monitoring the nutrient solution’s concentration, the OLED wavelength, irrigation system, crop wellbeing and quality control for all crops: lettuce, spinach, tomatoes and strawberries.

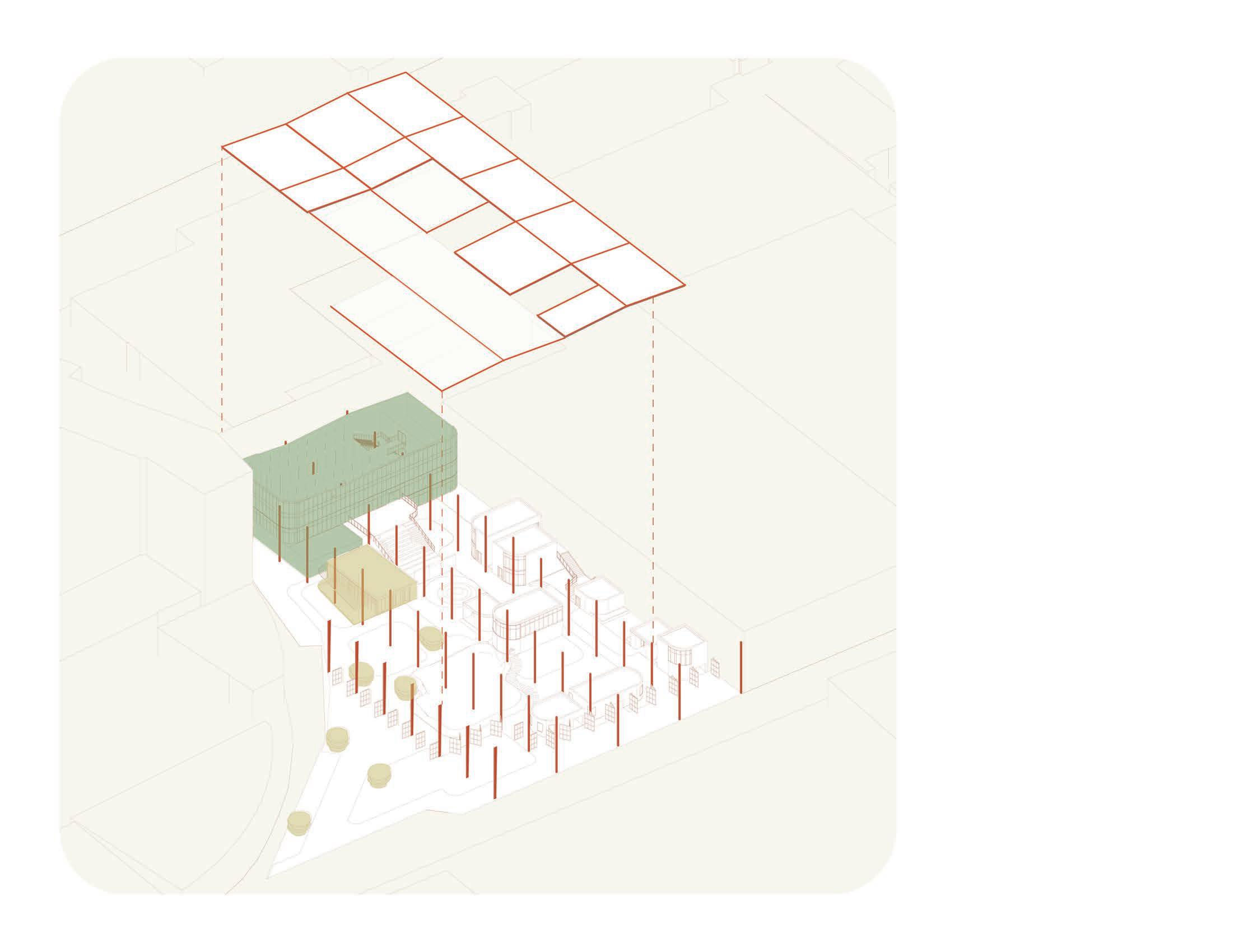

Since most crops go directly towards the community kitchen and restaurant, CAPA hydroponics achieve economic circularity as well as environmental sustainability.

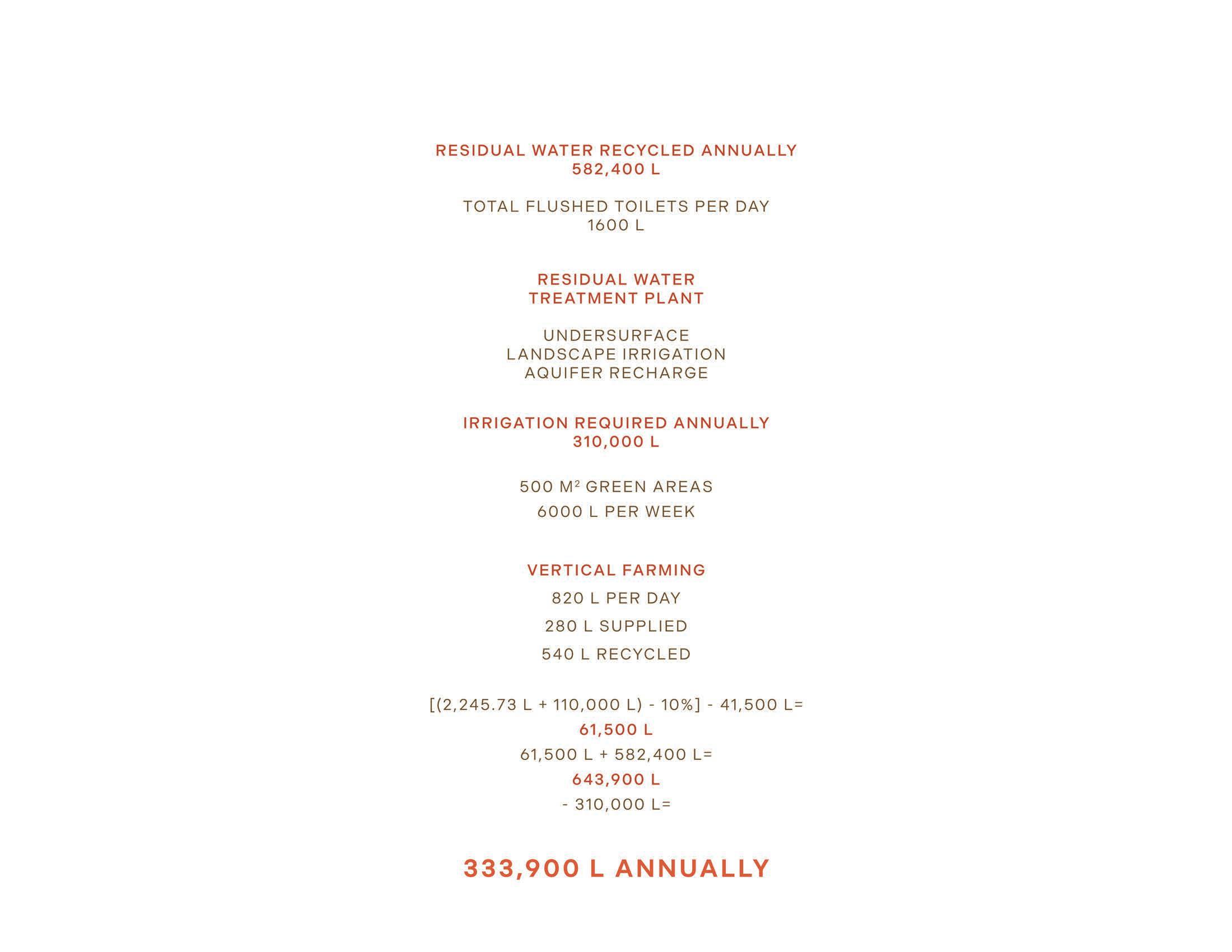

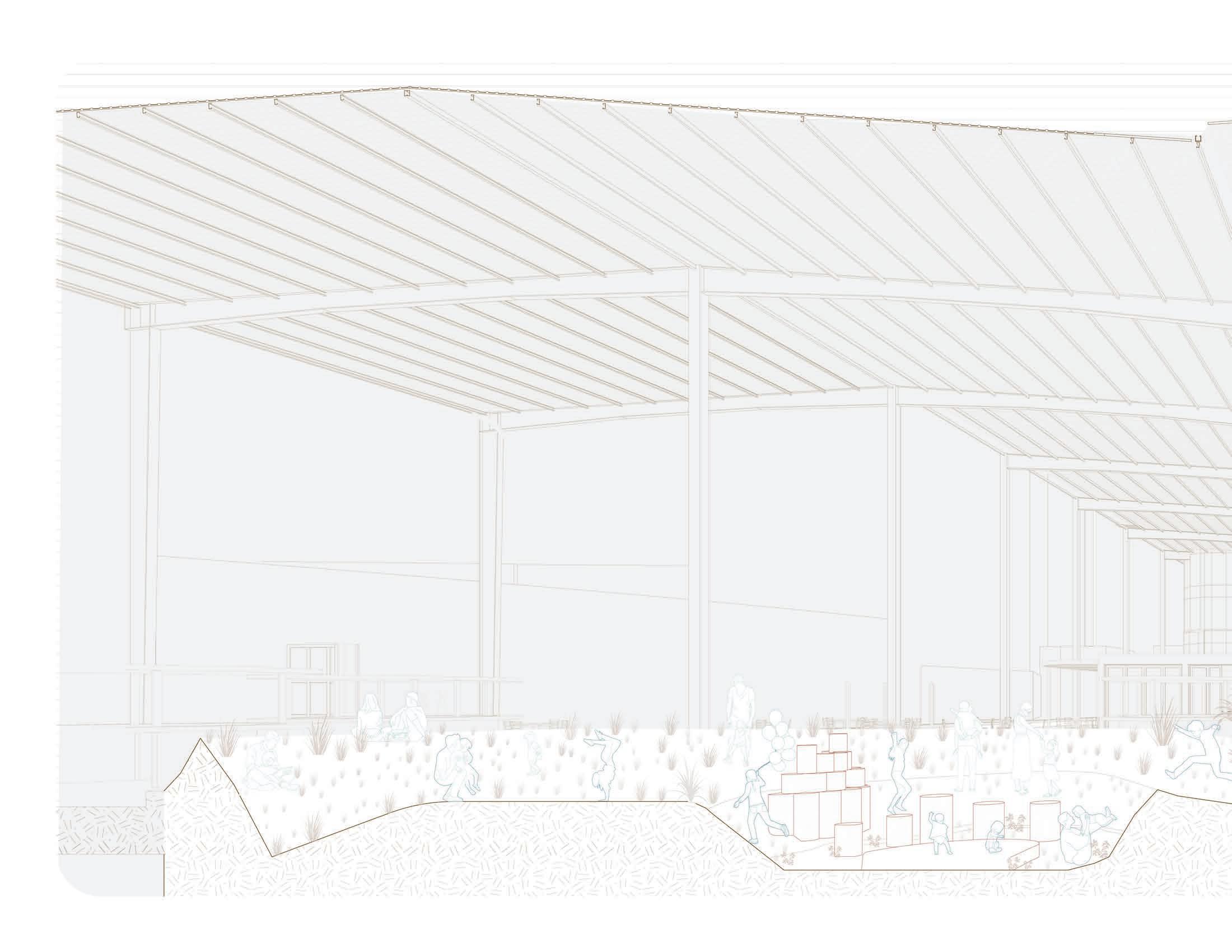

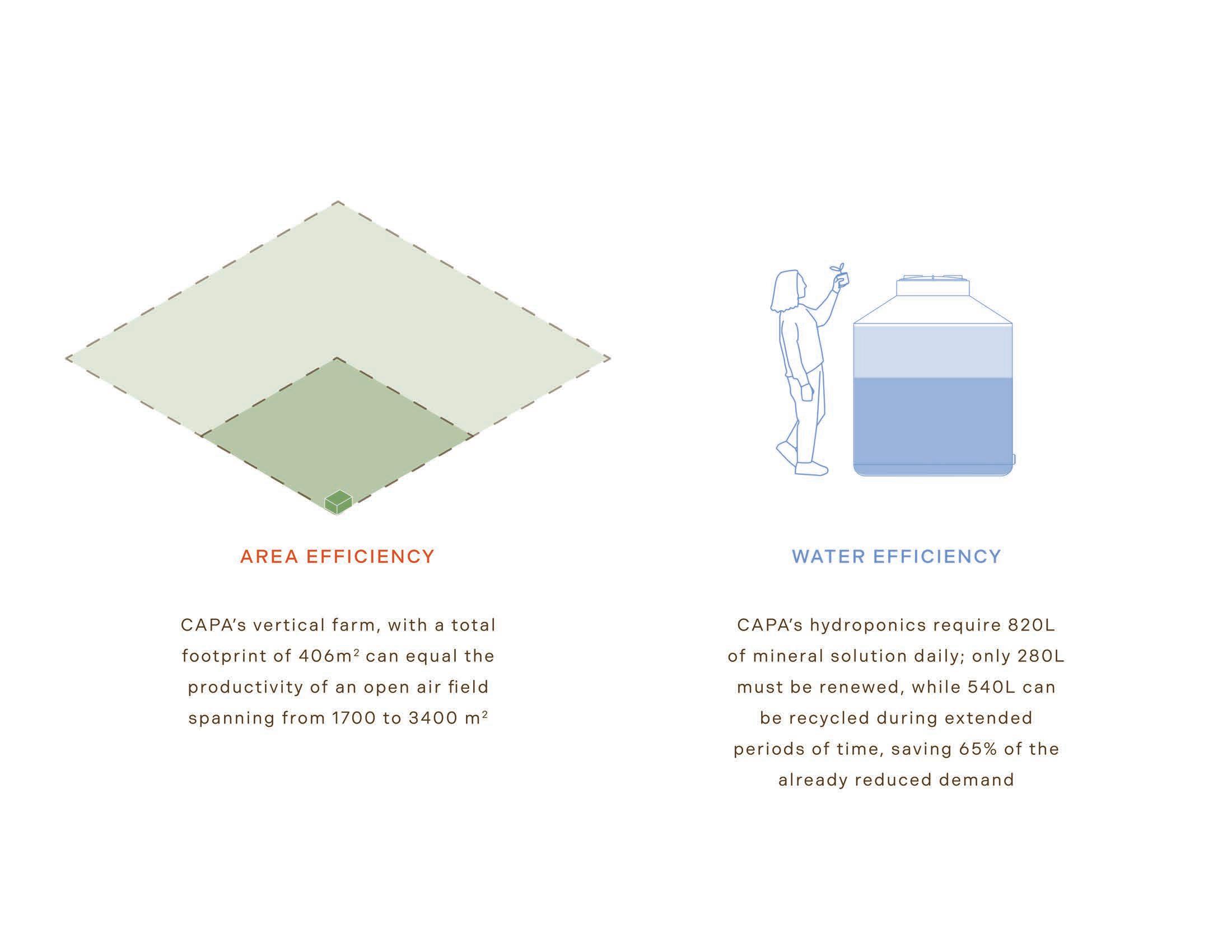

The space, a triple height enclosure with a north-facing curtain wall, procures natural lighting while controlling the crop’s growing conditions artificially. Its water efficiency permits recycling more than half of daily inputs. Nutrient solutions are crafted at the laboratory, irrigation systems powered by a machine room, and crops end up in dry or cold storage before consumption. Excess biomass is composted, and plant transpiration is condensed and used for air conditioning. Tomorrow’s farming wastes nothing.

If traditional agriculture were the only option, the world would need new arable land the size of Brazil to satisfy food needs by 2050. Thankfully, it isn’t.

In line with Dr. Dickson Despommier’s reasoning, we must innovate using common sense. Crops must be grown inside of cities for urban populations to procure a nearby sustainable and reliable food source, grown in more efficient, reliable and environmentally regenerative surroundings.

Hydroponics, for example, were created by NASA for growing food in space and it is now a widespread technique in vertical farms globally.

Even if initial investments are costly due to unaccustomed technologies, the return of investment includes food security, a positive carbon footprint, energy and water savings, and new jobs for skilled workers in HVAC, agronomy and biochemical sectors.

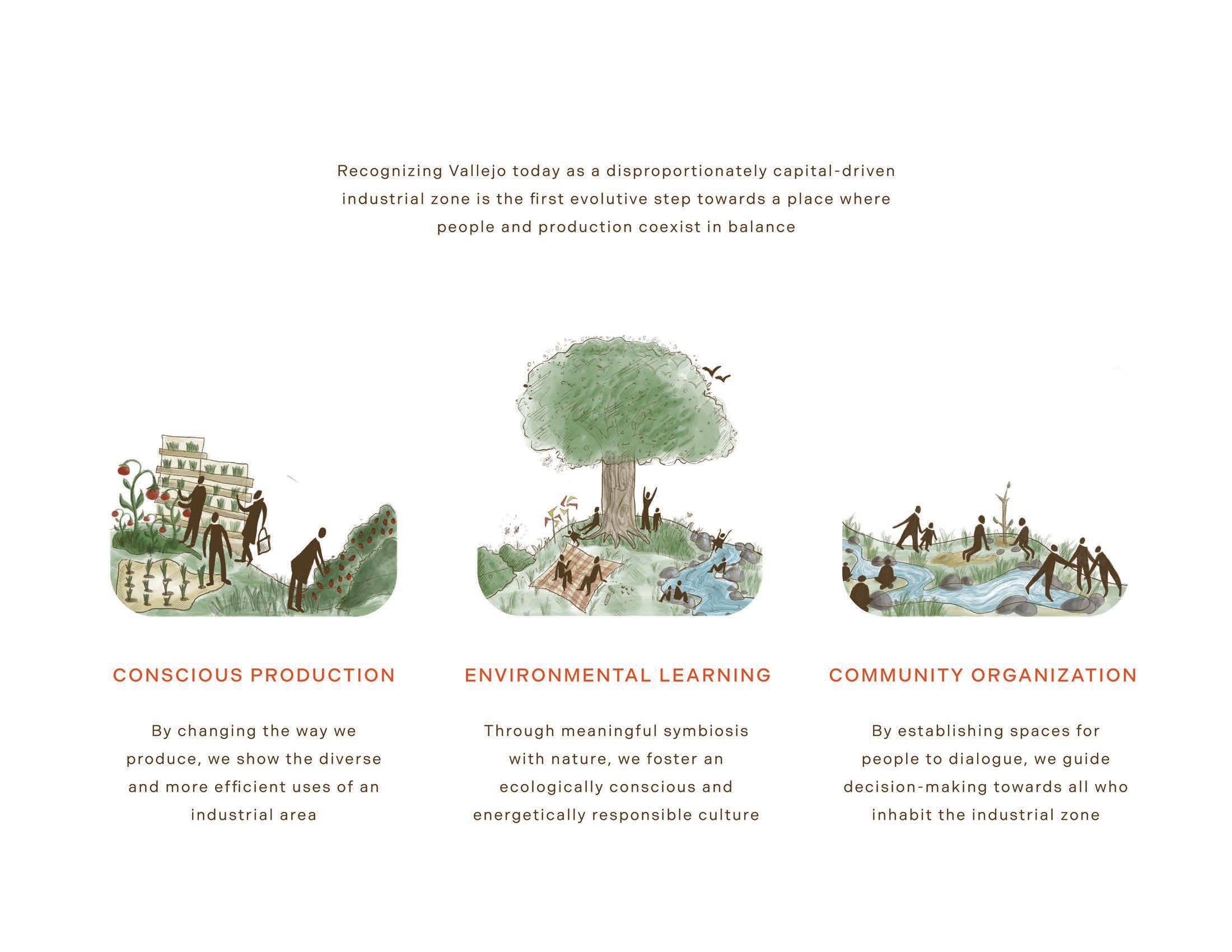

For this site, vertical farming represents a paradigm shift regarding large scale production towards conscious and sustainable practices. In a sense, this modern take on farming is an update to the original Vallejo hacienda where agriculture and livestock were the main activity. What if the new industry is the one that started it all along?

Towards the end of their day, Cecilia and Héctor attend a cooking class at the community kitchen, where an instructor leads the class into making a tasty dessert using CAPA hydroponic strawberries and tejocote fruit from the plaza. These classes occur thrice a week with varying menus, all including at least one locally sourced ingredient. During days without lessons, father and daugther can enjoy salads, wraps, bowls, smoothies and other healthy foods at the café. To go or for eating at a table in the terrace, there are always great options that cater to many tastes.

The open kitchen offers nine complete stations for cooking lessons, with a storage and refrigeration area at the side, and an opposing curtain wall with views to the terrace and plaza. This space is larger than the café’s kitchen without sacrificing quality equipment. This service kitchen has a convenient connection to the community garden’s dry storage room for access towards bulked goods, fresh vegetables or other needed items.

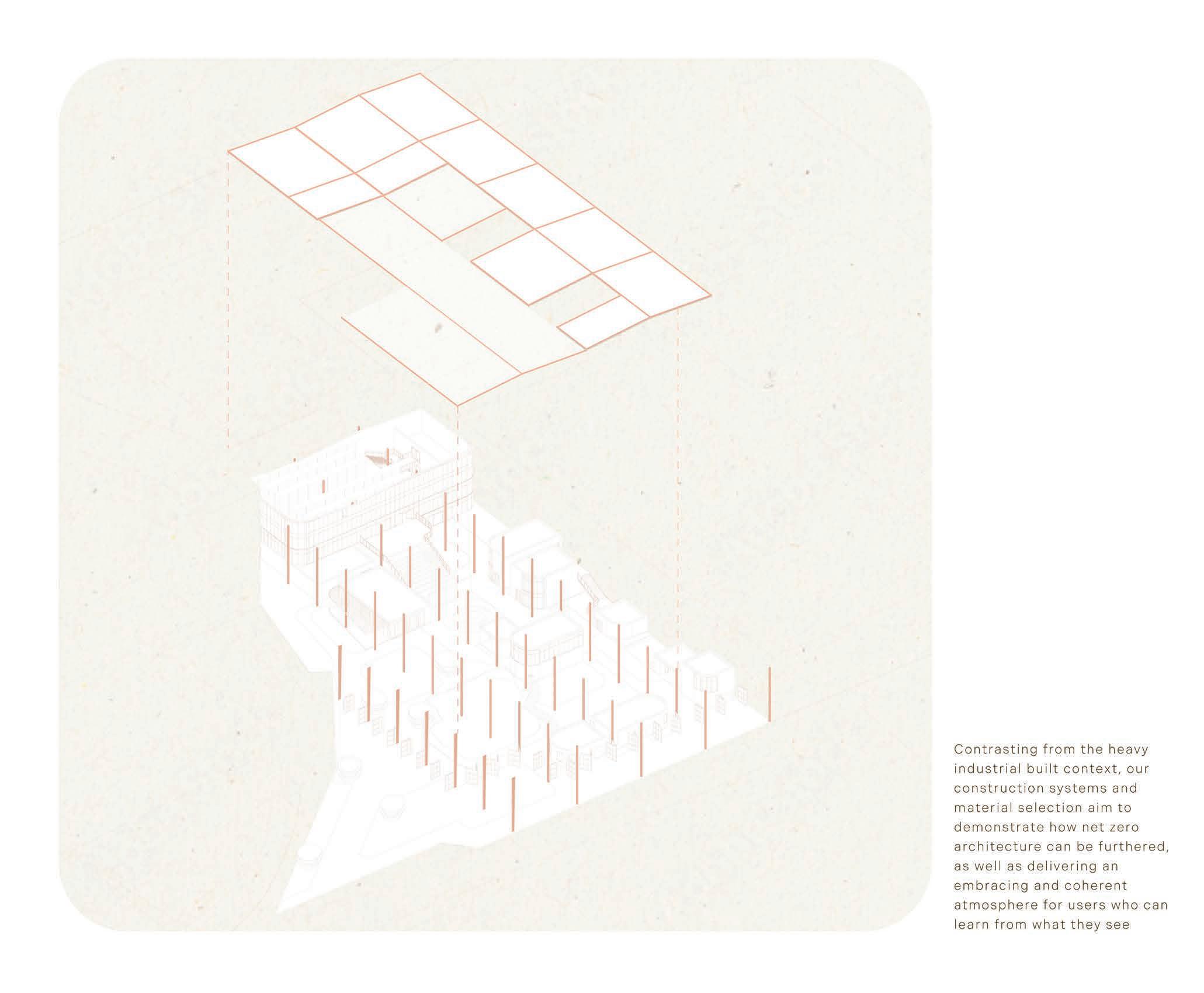

PRODUCTIVE REGENERATIVE NET-ZERO

1. A gritecture & WayBeyond (2021) CEA Census Report 2021. https://engage.farmroad.io/hubfs/2021%20Global%20CEA%20 Census%20Report.pdf

2. A vellaneda, J; Cuchí, A; Wadel, G. (2010) Sustainability in industrialized architecture: closing the materials cycle https:// www.researchgate.net/publication/41804886_La_sostenibilidad_en_la_arquitectura_industrializada_cerrando_el_ciclo_de_ los_materiales

3. C andelario, T. C. (2019) Industrial Vallejo: una historia económica, urbana y política de la industrialización en la Ciudad de México,1940-1982. El Colegio de México. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11986/COLMEX/10001900

4. C arvajal, M; et al (2010) Investigación sobre la Absorción de CO2 por los Cultivos Más Representativos. http://www.lessco2. es/pdfs/noticias/ponencia_cisc_espanol.pdf

5. C omisión Nacional de Vivienda (2024) Sierras Templadas: Paleta de Especies en Recomendaciones para Elección de Especies Arbóreas, Arbustos y Cubresuelos (pp. 100-111) https://siesco.conavi.gob.mx/doc/tecnicos/paleta/Paleta%20 Vegetal.pdf

6. D ay, J; Midbjer, A. (2007) Environment and Children. Architectural Press

7. D espommier, D. (2020) The Vertical Farm: Feeding the World in the 21st Century. Picador, New York.

8. D udek, M. (2005) Children’s Spaces. Architectural Press https://architecturalnetworks.research.mcgill.ca/assets/childrens-space-min.pdf

9. F orest Stewardship Council España (2023) En Madera, otra forma de construir. El material constructivo sostenible del siglo XXI. https://www.miteco.gob.es/content/dam/miteco/es/biodiversidad/temas/politica-forestal/En%20madera,%20otra%20 forma%20de%20construir.%20El%20material%20constructivo%20sostenible%20del%20siglo%20XXI.pdf

10. H uerta, D; Suárez, A. G. (2023) Cities of Care https://issuu.com/projectsforthefuturecity/docs/cities_of_care

11. L akatos, E. S; et al (2021) Conceptualizing Core Aspects on Circular Economies in Cities. Sustainability. 13(14) https://doi. org/10.3390/su13147549

12. M ontiel, R. (2022) PILARES https://rozanamontiel.com/pilares/

13. N omad Garden (2024) Especies. https://gardenatlas.net/garden/doramas/species/

14. S ASAKI (2016) Sungqiao Urban Agricultural District https://www.sasaki.com/projects/sunqiao-urban-agricultural-district/

15. S ecretaría de Desarrollo Económico (2022) Diagnóstico de Transición Energética de la Ciudad de México. https:// ciudadsolar.cdmx.gob.mx/storage/app/media/Documentos%20en%20%20colaboraciones%20o%20importantes/diagnosticode-transicion-energetica-cdmx.pdf

16. S olarvolt (2024) Solar Test™ https://www.vitrosolartest.com/

17. T hink Wood (2019) Evaluating the Carbon Footprint of Wooden Buildings https://www.thinkwood.com/wp-content/ uploads/2019/08/Think-Wood-CEU-Evaluating-the-Carbon-Footprint-of-Wood-Buildings.pdf

18. U niversidad Nacional de Córdoba, Facultad de Arquitectura, Urbanismo y Diseño (2019) Tablas para el predimensionado. Estructuras. La versatilidad de la madera. 2(3-4) (pp. 17-21) https://revistas.unc.edu.ar/index.php/estructuras/issue/ view/2020/438