3 minute read

Steel in space

What links conspiracy theories, cheese, James Stewart, and things that howl in the night?

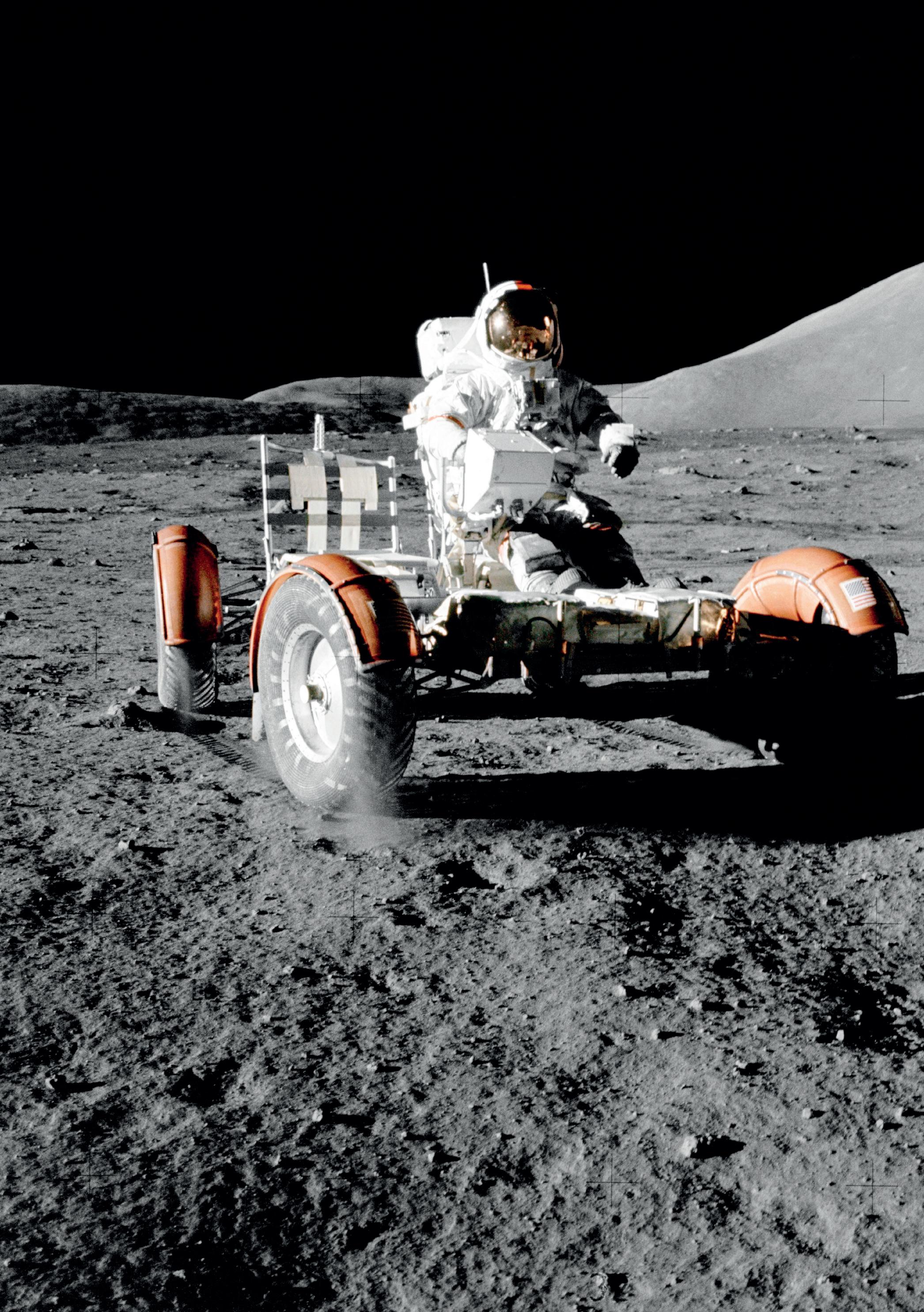

The moon is as much a fixture in our cultural life as it is suspended in space. It is also, for a growing company in Israel, a unique opportunity to decarbonize steelmaking – a readyto-go base for mining materials that have been exhausted on Earth. ‘’No-one has done this before’’, Jonathan Geifman* tells Catherine Hill**. His company, Helios, is the beginning of a lunar revolution, that despite its critics, sees life in Ferris Bullerian terms; it moves pretty fast – what was once implausible, will soon be trivial.

‘MAN is by nature a social animal’, said Aristotle. Another interpretation: we’re hardly more adapted to our environments rather than short-circuited by what appears to be important. Living is, for an overwhelming part of the global population, an earthly concern; birth, death, relationships, and work all taking place under the clingy weight of gravity. However, for a select few, office smalltalk isn’t about diets, weather and missed weekends – for Jonathan Geifman, founder and CEO of Helios, water cooler chat has been about NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS), an American super heavy-lift expendable launch vehicle, which at the time of interview, had yet to make its first attempt to enter space.

When I ask him if he thinks the launch suggests that we are living in a second space race, he quickly interjects as I struggle to remember the date the launch was scheduled to take place. ‘‘Two and a half weeks.’’ Later, I ask him if his work ever feels as extraordinary to him, as it appears to outsiders – with a business focus on researching human life and industry on Mars and the moon. ‘‘When you’re in this’’, he tells me, ‘‘and especially when you work with the space industry….it’s trivial. I mean, you just talked about SLS. Most [people] don’t know about SLS. In the space sector, it’s all that we’re talking about. We know the companies who are building it, designing it. We know the contract for sending the astronauts to the moon, et cetera. When you’re invested in this, when you’re part of this community, it all seems very trivial’’.

This ‘trivial’ work culminated in the form of Helios, an Israel-headquartered company focused on developing a reactor that can process lunar soil and Martian soil in to oxygen and metals. Through engineering the required technology, however, the company stumbled upon a ‘novel method to produce iron from iron ore, requiring only thermal energy, and emitting only oxygen.’ The aforementioned technology is contained in a special module which is directly integrated into DRI (Direct Reduced Iron) furnaces, which, it is claimed, reduce cost and facilitate faster adoption. In short, Helios claims it has developed a way to use space technology to decarbonize the steel industry.

The steel industry was not the first area of focus for the company, however, as its initial aim was to establish infrastructure in space; processing oxides on the planetary surfaces into oxygen and metals in order to create a liveable, breathable environment. The metals would be used to build storage and accommodation, resource transportation, and surface tiles and roads, allowing ‘future colonization’ of the moon and Mars, with the development and application of Helios’ planet-proof processes.

Developing Helios’ processes started, says Geifman, by returning to the first principles; ‘literally opening the periodic table and trying to figure out what we can do differently that will meet the harsh requirements of the lunar environment.’

It was ‘out of necessity’, he continues, that Helios came up with a method to extract resources from the surface soil of Mars and the moon, which includes four processes of extraction, separation of oxides, processing of the material, and storage, throughout which metal biproducts – including iron, aluminium and titanium – are reaped from the soil. Through researching these processes, the company realized that ‘one of the methods might be a great fit for the steel industry’ as when iron was extracted via their modules, there were ‘no direct emissions, as carbon isn’t used, and indirect emissions are also reduced as 50% less energy is used compared with how steel is produced today.’ With the modules’ use of thermal energy rather than traditional high-emitting fuels, Helios claims it has created a cleaner way to make steel. ‘‘If you run the numbers’’ Geifman says, ‘‘you see that it will reduce the production cost of iron in the process by up to 20%.’’ Helios’ green steel technology is based on sodium as the reducing agent, a two-step process in which sodium is used to reduce first row transition metals (like iron), and in the second step, the by-product sodium oxides are dissociated to reclaim the sodium in metal form and keep it in a closed loop within the system.

Geifman feels the topic of so-called ‘green premiums’– the high costs associated with converting to sustainable production methods – is often ignored, particularly in the context of reaching the goal of net-zero by 2050. ‘‘All the green