Puerto Rico Coral Reef Ecosystem Valuation: Scenario Analysis of Non-Market Values of Reef Using Visitors

Background

In 2016-2017, in partnership with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Puerto Rico Sea Grant, NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries was able to estimate the non- market value of various coral reef attributes to reef using visitors. The report, Nonmarket Economic Value by Reef Using Visitors on Puerto Rico’s Coral Reef Ecosystems, An Attributes Approach: Policy/ Management Scenarios, 2018, presents the results of the marginal willingness to pay of users for four distinct management scenarios.

The Usefulness of Scenarios

The natural resources valued in this study were carefully selected based upon existing literature and research, natural science teams and focus groups. One of the primary considerations of this work was identifying realistic improvements given additional management or policy interventions in the Guánica Bay Watershed.

Since the improvements to the resources are expected to be attainable with additional management and policy intervention, the monetary benefits of targeted management actions can be evaluated. This means that if management decides to engage in restoration in the Guánica Bay watershed in southern Puerto Rico or other area’s corals and reef fish, the value to coral reef users can be estimated. This benefit can then be compared to the cost of restoration.

Management has many tools at their disposal to raise the condition of the coral reef attributes form the low to medium or high condition. Knowing the value and costs to implement a strategy or policy can help to ensure that there are net positive benefits to the public for restoration or conservation measures.

The four policy scenarios were developed and provided by the U.S. EPA, Office of Research and Development, and National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory to demonstrate the benefits of coral reef ecosystem restoration. The scenarios are not real plans but simply serve to demonstrate the utility of the models.

Non-Market Value

The environment and ecosystems provide many benefits to humans. The ways in which humans benefit from ecosystems, such as recreation, food supply, and shoreline protection from storms, have come to be known as ecosystem goods and services. The economic value of some of these goods and services, such as fish for food, can be estimated through market sales and pricing. But others, such as recreation, which depends on water quality and the abundance and diversity of colorful fish, coral and sponges, are not traded in markets. The monetary value of these ‘non-market’ goods and services must be estimated using alternative methods.

www.coris.noaa.gov/activities/projects/pr_reef_ecosystem_valuation/

Photo: Environmental Protection Agency

Map of Puerto Rico

Policy/Management Scenarios

Each of the scenarios above represents a mix of improving various attributes from the low to a medium or high level. If all of Puerto Rico were declared a no fishing zone, where all reefs were protected from the taking of fish and shellfish, then stony and soft corals would be expected to improve from low to medium conditions Consumptive fish, ornamental fish, invertebrates, large wildlife, and sport/trophy fish would be expected to improve from low to high, and water clarity and cleanliness see no change.

The reduction in sediment scenario involves reducing sediment from run-off in the watersheds that affect coral reefs. Stony corals, soft corals, consumptive fish, and invertebrates improve from low to medium condition. Large wildlife, sport/trophy fish, water clarity, and water cleanliness improve from the low to high condition, but water clarity and cleanliness would see no change. If only certain areas of Puerto Rico were designated no fishing zones, then improvements to these attributes would be proportionally less. Reducing physical damage involves the installation of mooring buoys, no anchoring regulations and education on buoyancy control for diver and vests for snorkelers on coral reefs. Soft corals and invertebrates would improve from low to medium, stony corals would improve from low to high condition, and consumptive fish, ornamental fish, large wildlife, sport/trophy fish, water clarity, and water cleanliness would see no change.

Scenario Outcomes

Three of the four scenarios analyzed in the report are shown in the table above. The present value for each attribute was determined from reef using visitors to Puerto Rico based on existing (low) conditions, and then summed. The combined values of all attributes were then estimated over time based on expected improvements from a management scenario.

The estimates of total annual benefits are then capitalized to estimate the net present value of the changes. This is done for three time periods: 1) 10 years; 2) 20 years; and 3) perpetuity or the indefinite future.

The capitalized value of net present value (NPV) is the value someone would pay today for the flow of annual returns over time. A good example is a house that delivers a flow of services over time, but, at any point in time, there is a price people are willing to pay for the house. The same concept can be applied to this research. To convert the future values to net present values, discount rates of 2.0 percent and 3.0 percent were selected.

The values of the scenarios and the tool developed to evaluate various scenarios are useful in determining the monetary value of improvement to reefs by reef using visitors to Puerto Rico.

For more information

A complete copy of the report is available at:

https://www.coris.noaa.gov/activitie s/projects/pr_reef_ecosystem_valu ation/

Or Contact

Dr. Vernon R. (Bob) Leeworthy Chief Economist, ONMS

Bob.Leeworthy@noaa.gov

Dr. Danielle Schwarzmann Economist, ONMS

Danielle.Schwarzmann@noaa.gov

www.coris.noaa.gov/activities/projects/pr_reef_ecosystem_valuation/

Puerto Rico Coral Reef Ecosystem Valuation: Recreation Activities and Uses Among Visitors

523,700 sightseeing participants

369,500 diving/ snorkeling participants

A 2018 analysis of socioeconomic survey data provides new insight into the types of recreational activities in Puerto Rico among reef using recreational visitors The report, Visitor Profiles: Reef Users, is the result of a partnership with NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries (ONMS), the Environmental Protection Agency, and Puerto Rico University, Sea Grant. The report estimates the amount of time people spend recreating in the area and the activities they enjoy in the summer and winter seasons. The summer season was May-October of 2016 and the winter season was November 2016 to April 2017.

630,000 days of

How are reef using visitors using Puerto Rico?

Puerto Rico visitors reported engaging in over 20 different activities in Puerto Rico Some of the most common activities are beach going, hiking/biking, camping, sightseeing, and watching wildlife from the shore. Less frequently reported recreational activities include surfing, fishing, and photography. The images to the left show number of participants for activities on the reefs, shoreline, and further inshore.

1,964,600 beach going participants

Visitor trips to Puerto Rico in the summer lasted an average of 8.5 days, while in the winter they lasted an average of 8.9 days. Among all visitors to Puerto Rico there were 1.67 million person-trips in the summer and 1.74 million person-trips in the winter season.

28,500 fishing participants

When considering only reef using visitors, there were 843,651 person-trips in the summer and 327,717 person-trips in the winter season. The surveyed coral reef users spent more than 7.1 million “person-days” recreating in the summer and about 2.9 million person-days in the winter A person-day is the number of days a person spent on their trip, so one trip where a person stayed for five days would be five person-days. If there were three people on the trip, then that would be 15 person-days. On an average day in the summer there were roughly 4,600 visitors using reefs and in the winter there were roughly 1,800 visitors using the reef for recreation.

75,200 paddlesport participants

253,900 boating participants

www.coris.noaa.gov/activities/projects/pr_reef_ecosystem_valuation/

Map of Puerto Rico

Photos: Environmental Protection Agency

What are visitors doing in Puerto Rico?

Across all of the visitors to Puerto Rico (both reef and non-reef using), 1.9 million participated in beach going activities that include both water and non-water based activities. The next most popular activity among all visitors was wildlife viewing, with roughly 523,700 participants. Camping, backpacking, hiking and picnicking were also common activities with about 432,000 participants. There were 852,600 participants in cultural, historical, and other tourist attractions such as attending special events, visiting historical sites, reading roadside exhibits, and visiting museums. Less common activities included fishing and boating, outdoor sports, and bicycling. The table below shows participation rates for reef using activities only. For reef-related activities, swimming and diving had the highest participation rates across both the winter and summer seasons.

More Information:

A complete copy of the report is available at: https://www.coris.noaa.gov/ activities/projects/pr_reef_ ecosystem_valuation/

Dr. Vernon R. (Bob) Leeworthy Chief

Economist

Office of National Marine Sanctuaries

Bob.Leeworthy@noaa.gov

Dr. Danielle Schwarzmann

Economist

Table: Visitors and Participation Rates by Reef Using Activity

Office

of

National Marine Sanctuaries

Swimming Snorkeling Viewing Nature & Wildlife Paddle boarding, Wind Surfing, or Kite boarding

Summer Winter WeightedAnnual Average Activity Number of Visitors Participation Rate (%)1 Number of Visitors Participation Rate (%)1 Number of Visitors Participation Rate (%)1 All Diving 277,925 32.94 91,559 27.94 369,484 31.54 Snorkeling 270,871 32.11 89,874 27.42 360,745 30.8 SCUBA Diving 16,224 1.92 6,449 1.97 22,673 1.94 Reef Fishing 9,876 1.17 3,428 1.17 13,304 1.14 ViewingNature & Wildlife 147,427 17.47 62,743 19.15 210,171 17.94 Surfing 10,581 1.25 19,113 5.83 29,694 2.54 Swimming 761,120 90.22 264,625 80.75 1,025,745 87.57 Paddle boarding, wind surfing, or kite boarding 55,726 6.61 19,520 5.96 75,246 6.42 76.2 23.1 14.2 5.4 0.9 0.8 0.3 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80

Danielle.Schwarzmann@noaa.gov User Participation Rate (%()

SCUBA Diving Reef Fishing Surfing

Summer Reef User Participation Rate

www.coris.noaa.gov/activities/projects/pr_reef_ecosystem_valuation/

Puerto Rico Coral Reef Ecosystem Valuation: Analysis of Non-Market Values of Reef Using Visitors

Background

In 2016-2017, in partnership with the Environmental Protection Agency and Puerto Rico Sea Grant, NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries was able to estimate the nonmarket value of various coral reef attributes to reef using visitors. The report, Technical Appendix: Non-market Economic Value by Reef Using Visitors on Puerto Rico’s Coral Reef Ecosystems, An Attribute Approach, 2018, presents the results of the marginal willingness to pay of users for nine different coral reef attributes.

NOAA’s objectives included obtaining information on people’s preferences for different corals (e.g. hard and soft corals), fish and wildlife, and water quality, and estimation of the non-market economic values, and estimation of how values for those attributes change with changes in natural resource attributes and user characteristics.

Non-Market Value

Motivation of Research

Working with coral reef scientists and focus groups, several key attributes that are significant to the health of ecosystems and consequently human use and satisfaction were identified. Coral reef scientists helped to determine realistic improvements to resource attributes that could be attained through various management strategies.

This information was then used to develop the surveys to estimate respondents (coral reef users in Puerto Rico) willingness to pay for marginal changes to the resource. Understanding how willingness to pay changes as resource attributes improve, helps resource managers to both maximize and communicate the benefits of policy or regulatory changes and to determine if benefits will exceed costs.

The results of this work provide the willingness to pay for marginal changes to 10 different coral reef resource attributes and the total willingness to pay for marginal changes across all reef using visitors to Puerto Rico.

The environment and ecosystems provide many benefits to humans. The ways in which humans benefit from ecosystems have come to be known as ecosystem goods and services. Examples include recreation and food supply. Recreation depends on water quality, abundance and diversity of fish and wildlife, and abundance and diversity of coral and sponges. Many goods and services are not traded in markets, meaning a person cannot go to the store and buy a unit of coral reef quality.

The environment and ecosystems provide many benefits to humans. The ways in which humans benefit from ecosystems, such as recreation, food supply, and shoreline protection from storms, have come to be known as ecosystem goods and services. The economic value of some of these goods and services, such as fish for food, can be estimated through market sales and pricing. But others, such as recreation, which depends on water quality and abundance and diversity of colorful fish, coral and sponges, are not traded in markets. The monetary value of these ‘non-market’ goods and services must be estimated using alternative methods.

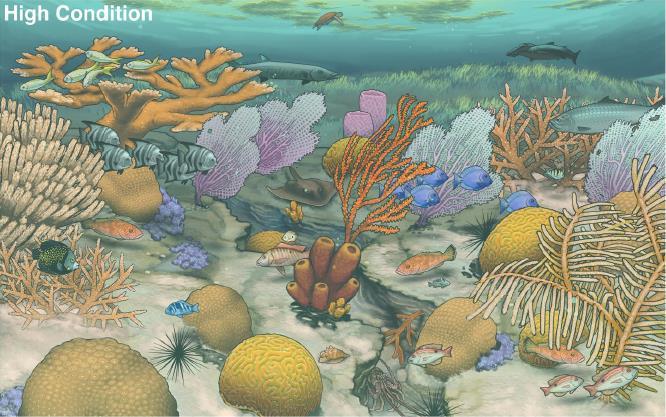

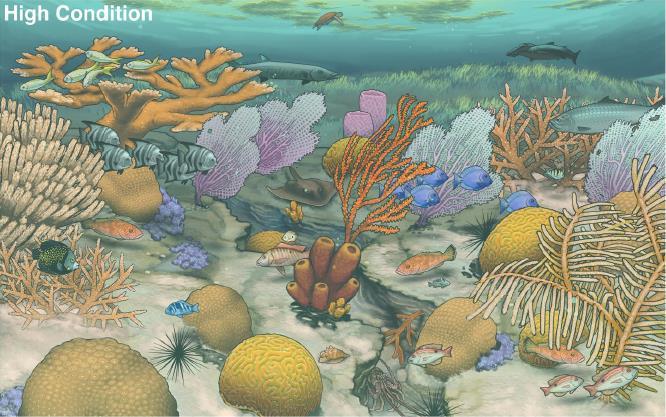

The picture to the left shows the high coral reef condition presented to respondents. This illustration was used to estimate the value that coral reef users have for improvements to reef attributes.

www.coris.noaa.gov/activities/projects/pr_reef_ecosystem_valuation/

Photo: Environmental Protection Agency

Illustration by: Daniel Irizarri Oquendo

Photo: Environmental Protection Agency

Illustration by: Daniel Irizarri Oquendo

Change in Attribute Condition

The values to the table above were estimated based on changes in resource conditions relative to the “Status Quo” or “Low” Condition. Status quo is defined as the condition the resources would be in 10-20 years if no changes in policy/management were made. Scientists then provided a range of resource conditions that were possible to achieve with changes in policy/management. A “medium” and “high” condition was defined for each of the resources in the table above. Therefore, what is estimated is the change in non-market value for direct recreation use on Puerto Rico’s coral reefs for each natural resource attribute as conditions are improved

What was measured in Puerto Rico?

The research discussed in this factsheet uses non-market valuation to estimate the monetary value of potential improvements to several different coral reef resources. Nine natural resource attributes were included in the study (see the table above and full report for details on condition levels).

Findings

Reef-using visitors to Puerto Rico, on an annual per-household basis, were willing to pay (WTP) for changes in water cleanliness, sport fish, invertebrates, and consumptive fish from low to high conditions.. This was followed by opportunities to see large wildlife, ornamental fish, and stony corals. Soft coral abundance was considered by coral scientists to be an indicator of declining coral reef water quality, so the low condition was set as a high number of soft corals and the high condition was a low number of soft corals. However, reef-using visitors valued an increase in soft corals from the low to medium condition but had a negative value for going from low to high and medium to high conditions.

More Information:

A complete copy of the report is available at: https://www.coris.noaa.gov/activities/projects/pr_ reef_ecosystem_valuation/

Dr. Vernon R. (Bob) Leeworthy Chief Economist Office of National Marine Sanctuaries Bob.Leeworthy@noaa.gov

Dr. Danielle Schwarzmann Economist Office of National Marine Sanctuaries Danielle.Schwarzmann@noaa.gov

www.coris.noaa.gov/activities/projects/pr_reef_ecosystem_valuation/

Variable Low to Medium Medium to High Low to High Stony Coral $22.30 $30.31 $52.61 Soft Coral $41.19 ($54.35) ($13.15) Consumptive Fish $29.55 $65.76 $95.31 OrnamentalFish $25.47 $29.25 $54.72 Invertebrates $93.35 $2.12 $95.46 Large Wildlife Not Estimated Not Estimated $66.82 Sport Fish Not Estimated Not Estimated $209.30 Water Cleanliness Not Estimated Not Estimated $255.78 Water Clarity $38.66 $15.15 $53.82 Crowdedness $11.87 $27.06 $38.93

Photos:

Environmental Protection Agency

Puerto Rico Coral Reef Ecosystem Valuation: Importance & Satisfaction of Natural Resources and Facilities

Background

A recent analysis of socioeconomic survey data provides new insight into the importance and satisfaction of natural resources, facilities and services among reef-using visitors in Puerto Rico The report Importance and Satisfaction Ratings by Reef Using Visitors in Puerto Rico, is the result of a partnership with NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries (ONMS), Environmental Protection Agency, and University of Puerto Rico, Sea Grant., and estimates the attitudes of recreational visitors to Puerto Rico who use the coral reefs

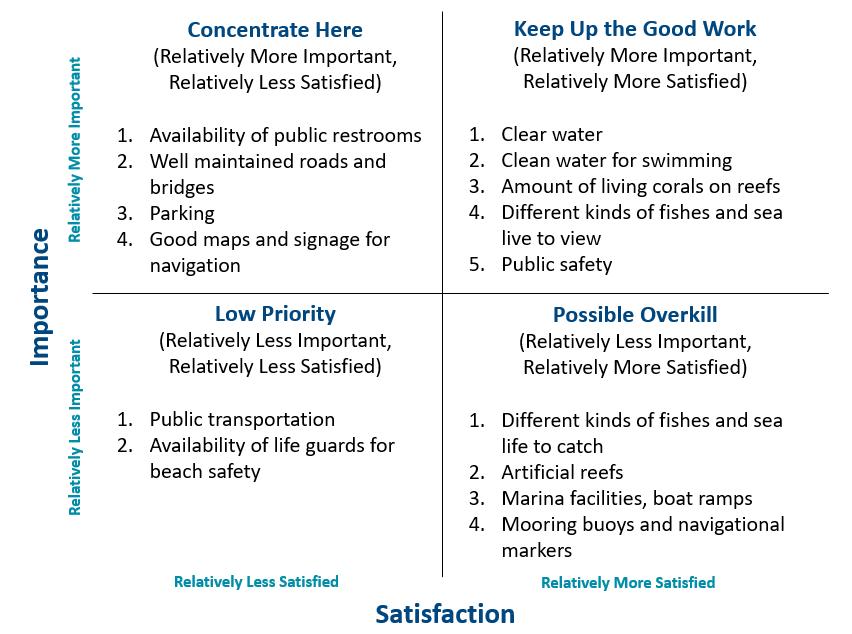

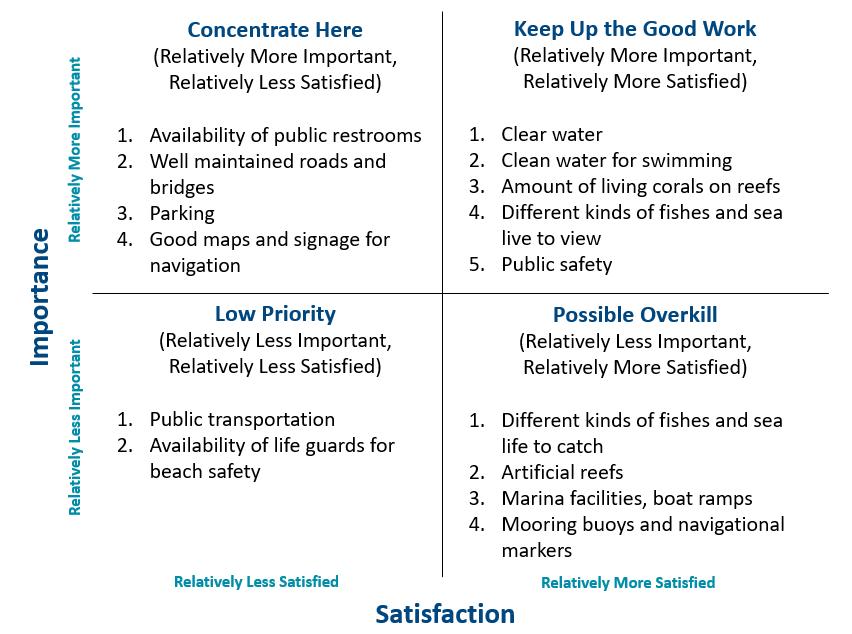

Respondents were asked to rate several environmental characteristics and access to facilities within Puerto Rico based on their level of importance and satisfaction. The level of importance was rated on a scale of 1 – “Not Important” to 5 - “Extremely Important”. Satisfaction was rated on a scale of 1 – “Terrible” to 5 - “Delighted”. In 2016 to 2017, reef using visitors could also answer “don’t know” or “not applicable” for both importance and satisfaction. These ratings can be used individually to inform decisions and better understand what users value or they can be used together to determine where management is doing a good job or where improvement is needed.

How to read the matrix?

By comparing the importance and satisfaction ratings, business and management can identify which areas need improvement, where they are doing well, and where resources could be redirected. The figure to the right shows the importance/satisfaction matrix and how priority areas are identified. For example, something with relatively high importance and relatively high satisfaction such as clean water and the amount of living corals would get a “ Keep up the good work.” Alternatively, something with relatively low satisfaction and relatively high importance as availability of public restrooms and well maintained roads and bridges would get “Concentrate here” indicating these items should receive more attention.

Puerto

www.coris.noaa.gov/activities/projects/pr_reef_ecosystem_valuation/

Importance/ Satisfaction Matrix Coral Reef Using Visitors to

Rico A guide for Management

What are the key findings?

Based on respondents who use coral reefs for recreation, another area that may require additional focus includes good maps and signs for navigation. Respondents felt like signs were relatively more important, but they were relatively less satisfied with the quality of maps and signs for navigation If satisfaction is not improved, it is possible that respondents may eventually switch to recreate in other areas that provide them with greater satisfaction or they switch activities if they still choose to visit Puerto Rico

Why is this important?

The results of this research will inform management about areas they can improve or where there may be some public misperceptions. For example, if respondents are reporting something is relatively unimportant to them, but from a scientific perspective, it is imperative for a healthy ecosystem outreach efforts to generate a better appreciation for healthy reefs might become a management priority

What should I know?

A healthy environment provides us with various recreational opportunities. Knowing what respondents find important, such as clean water, different kinds of fishes and sea life to view, control of invasive species, amount of living corals on reefs, and easy, abundant and quality beach and shorelines, reveals those aspects they find most valuable and how they might use the resources For example, some of the most common activities in Puerto Rico were snorkeling and swimming, which reflects the importance of coral reef organisms and quality beaches.

What about facilities?

Respondents also answered questions about facilities that are on Puerto Rico Respondents indicated that resorts with a focus on ecotourism and the cleanliness of streets and sidewalks was relatively more important and that they were relatively more satisfied with them. However, parking and well maintained roads and bridges were ranked as relatively more important, but reef using visitors were relatively less satisfied with these items. This indicates that business and management should focus on these items to increase user satisfaction.

More Information:

A complete copy of the report is available at: https://www.coris.noaa.gov/activities/projects/pr_r eef_ecosystem_valuation/

Dr. Vernon R. (Bob) Leeworthy Chief Economist Office of National Marine Sanctuaries Bob.Leeworthy@noaa.gov

Dr. Danielle Schwarzmann Economist Office of National Marine Sanctuaries Danielle.Schwarzmann@noaa.gov

www.coris.noaa.gov/activities/projects/pr_reef_ecosystem_valuation/

Map of Puerto Rico

Photos: Environmental Protection Agency

Puerto Rico Coral Reef Ecosystem Valuation: Economic Contributions from Coral Reef Based Recreational Users

What is the economic contribution/impact of recreation?

Marine based recreation generates significant economic revenues to coastal economies. When people enjoy healthy marine ecosystems, their activities and spending are contributing to the creation of local jobs and economic output.

How can you measure the economic contribution/impact of recreational use?

A large portion of recreational activities includes non-consumptive uses, which are activities that do not involve extraction of natural or marine resources. Some examples include sightseeing, going to the beach, kayaking, diving, and surfing

In partnership with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Puerto Rico Sea Grant, NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries was able to estimate the economic contribution of reef using visitors to Puerto Rico. The report, Economic Contributions of Reef Using Visitors to the Puerto Rican Economy, 2018, presents the results of economic models that estimated total annual expenditures of visitors to Puerto Rico who use coral reefs in the region and the associated economic impacts of recreational activity (based on surveys collected from October 2016 to May 2017). This information allows us to explore connections between the money spent by Puerto Rican visitors to enjoy these coral reefs, and the benefits this brings to the local communities in the form of jobs, products, income, and services.

www.coris.noaa.gov/activities/projects/pr_reef_ecosystem_valuation/

Photos: Environmental Protection Agency

Photos: Environmental Protection Agency

How much are Puerto Rican reef using visitors spending?

Expenditures were collected for both the visitors’ total trip and the portion of expenditures within Puerto Rico. The largest spending categories were Lodging and Food & Beverage. Lodging includes hotels, campgrounds, and rental properties. Food and beverage includes items bought at a grocery store and at dining establishments or bars.

In total, visitors spent about $534 million on lodging, of which nearly 84 percent or roughly, $446 million was spent within Puerto Rico. Nearly 100 percent of total food and beverages purchases were made within Puerto Rico. Additionally, reef-using visitors spent about $17 million on dive and snorkeling and 75 percent or nearly $13 million was spent within Puerto Rico. Unlike food, which is mostly perishable, dive and snorkeling equipment could be purchased in advance of visiting the island. In total, visitors spent $1.8 billion on trip-related expenditures and $1.4 billion of their total expenditures were made while on the island.

How many jobs?

Through the spending of reef using visitors, nearly 30,000 jobs in Puerto Rico were sustained. Further, nearly one billion dollars in labor income was generated and nearly two billion in output or gross domestic product was supported by reef using recreational visitors. These numbers do not include visitors who spent time on the island for other reasons and recreation that did not utilize the coral reefs, nor recreation by residents of Puerto Rico or commercial fishing.

More Information:

A complete copy of the report is available at: https://www.coris.noaa.gov/activities/projects /pr_reef_ecosystem_valuation/

Dr. Vernon R. (Bob) Leeworthy Chief Economist Office of National Marine Sanctuaries Bob.Leeworthy@noaa.gov

Dr. Danielle Schwarzmann Economist Office of National Marine Sanctuaries Danielle.Schwarzmann@noaa.gov

Definition of Key Terms (Adapted from Day, 2011)

Employment – Employment is the total annual average jobs. This includes self-employed in addition to wage and salary employees, and all full-time, part-time, and seasonal jobs, based on a count of full-time and part-time job averages over 12 months.

Labor Income – Labor income is equivalent to employee compensation plus proprietor (business owner) income.

Intermediate Inputs – Intermediate inputs are goods and service required to create a product.

Output – Output is the total value of an industry’s production, comprised of the value of intermediate inputs and value added.

Value Added – Value added demonstrates an industry’s value of production over the cost of the goods and services required to make its products.

Value added is often referred to as Gross Regional Product.

Non-Consumptive – Non-consumptive are activities that do not involve taking or harming the resource being used. Examples include sightseeing or photography

www.coris.noaa.gov/activities/projects/pr_reef_ecosystem_valuation/

Estimated Economic Impacts/Contributions (2017 dollars) Employment Labor Income Value-Added Output Total Effect 29,467 $935,952,079 $1,345,483,394 $1,964,633,445

Lodging Food& Beverage SCUBA Diving/ Snorkeling TotalTripRelated TotalExpenditures $534,083,084 $375,685,737 $16,795,162 $1,795,543,250 TotalExpenditures inPuertoRico $446,249,919 $374,447,085 $12,747,747 $1,411,387,940 Percentof Total Expenditures in PuertoRico 83.6% 99.7% 75.9% 78.6%

Annual

Expenditures byCategoryofSpending (2017 Dollars)

Photo: Environmental Protection Agency

Illustration by: Daniel Irizarri Oquendo

Photo: Environmental Protection Agency

Illustration by: Daniel Irizarri Oquendo

Photos: Environmental Protection Agency

Photos: Environmental Protection Agency