Volume 25, Number 6, November 2024

Journal of Behavioral Health

858 Recent Interventions for Acute Suicidality Delivered in the Emergency Department: A Scoping Review

Alex P. Hood, Lauren M. Tibbits, Juan I. Laporta, Jennifer Carrillo, Lacee R. Adams, Stacey Young-McCaughan, Alan L. Peterson, Robert A. De Lorenzo

869 Buprenorphine-Naloxone for Opioid Use Disorder: Reduction in Mortality and Increased Remission

Krishna K. Paul, Christian G. Frey, Stanley Troung, Laura vita Q. Paglicawan, Kathryn A. Cunningham, T. Preston Hill, Lauren G. Bothwell, Georgiy Golovko, Yeoshina Pillay, Dietrich Jehle

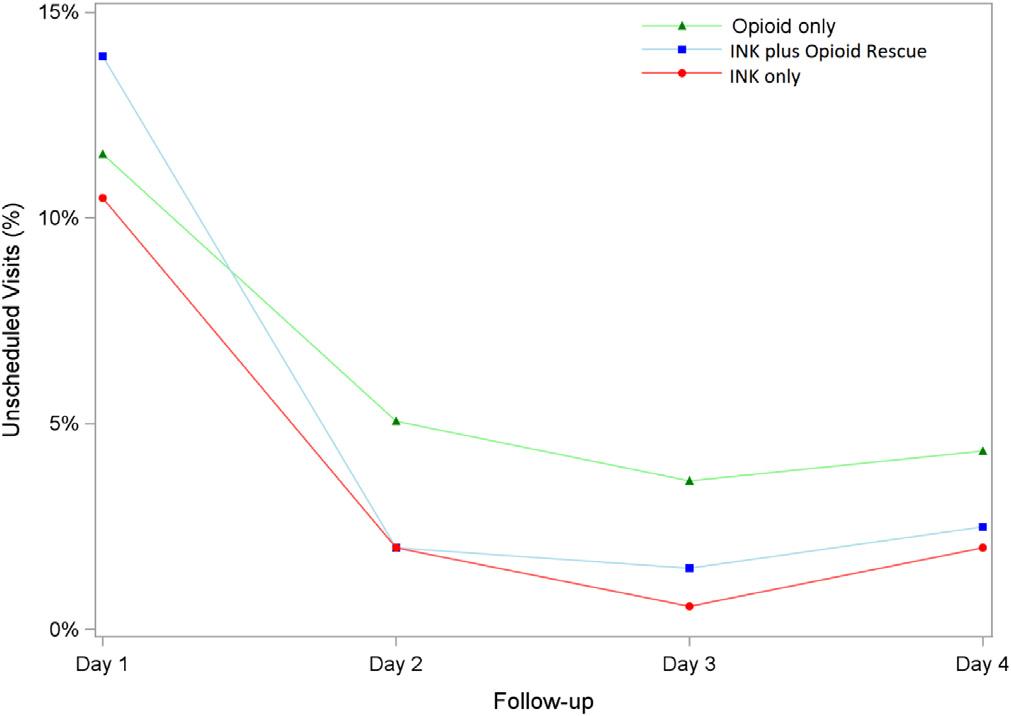

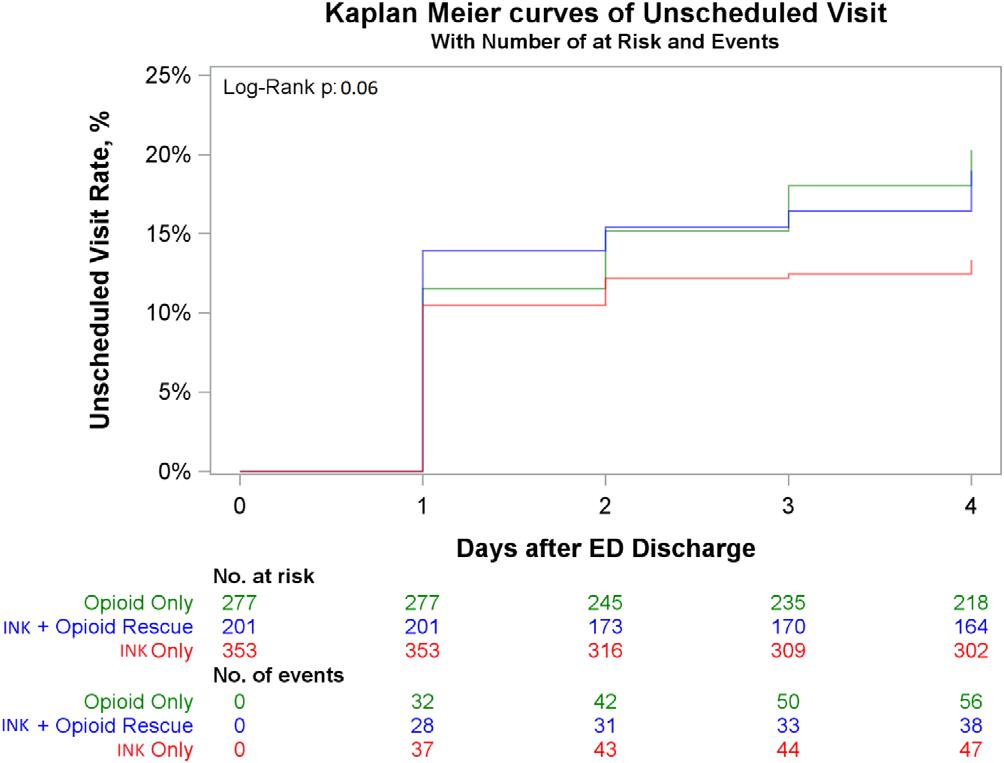

875 Opioid Treatment Is Associated with Recurrent Healthcare Visits, Increased Side Effects, and Pain

Caroline E. Freiermuth, Jenny A. Foster, Pratik Manandhar, Evangeline Arulraja, Alaattin Erkanli, Charles V. Pollack, Stephanie A. Eucker

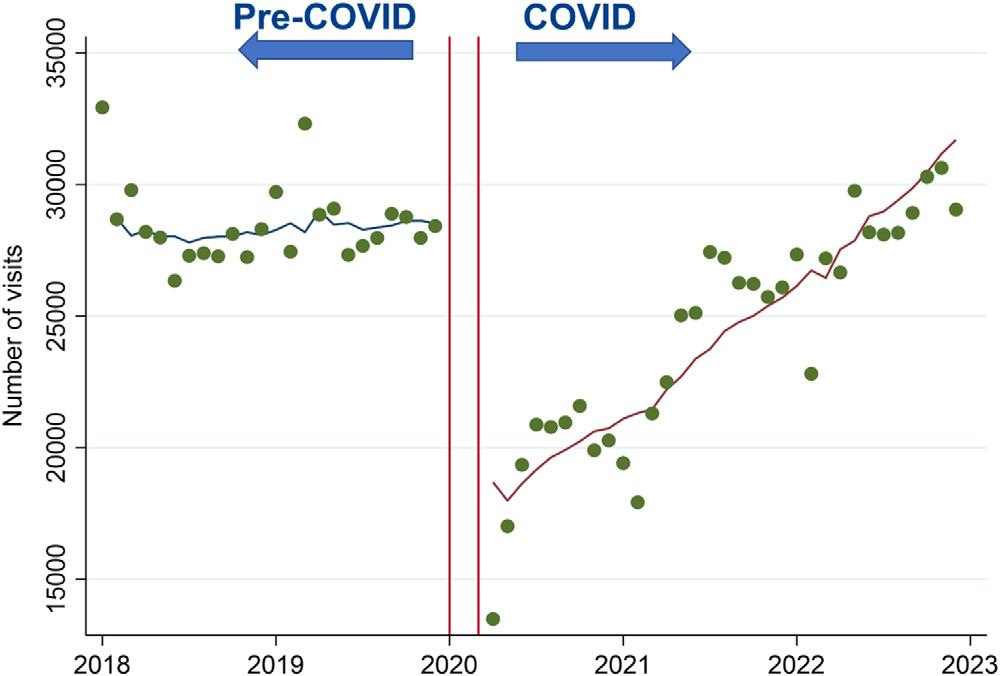

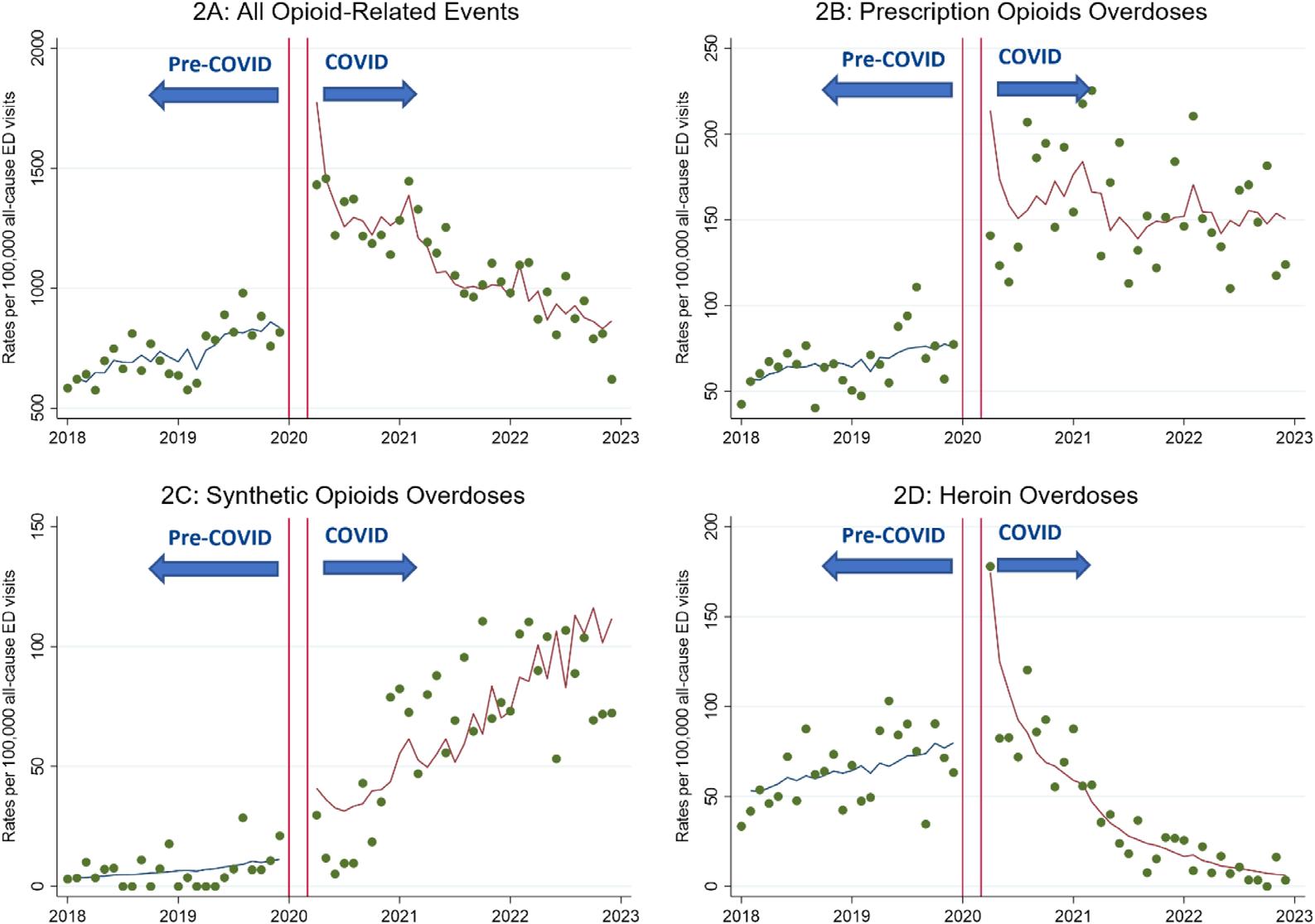

883 Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Emergency Department Visits for Opioid Use Disorder Across University of California Health Centers

Matthew Heshmatipour, Ding Quan Ng, Emily Yi-Wen Truong, Jianwei Zheng, Alexandre Chan, Yun Wang

Clinical Practice

890 An Assessment of the Presence of Clostridium tetani in the Soil and on Other Surfaces

Michael Shalaby, Alessandro Catenazzi, Melissa F. Smith, Robert A. Farrow II, David Farcy, Oren Mechanic, Tony Zitek

Critical Care

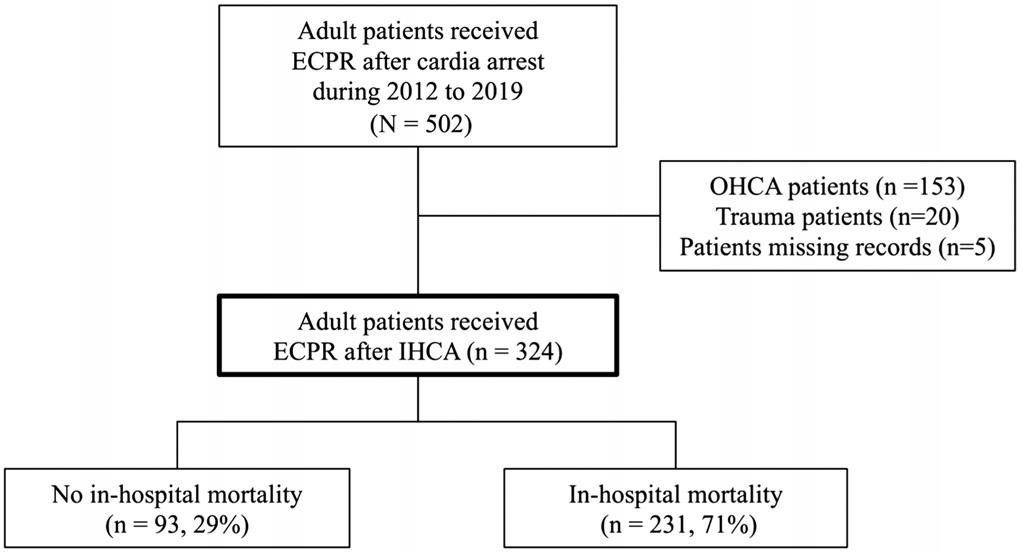

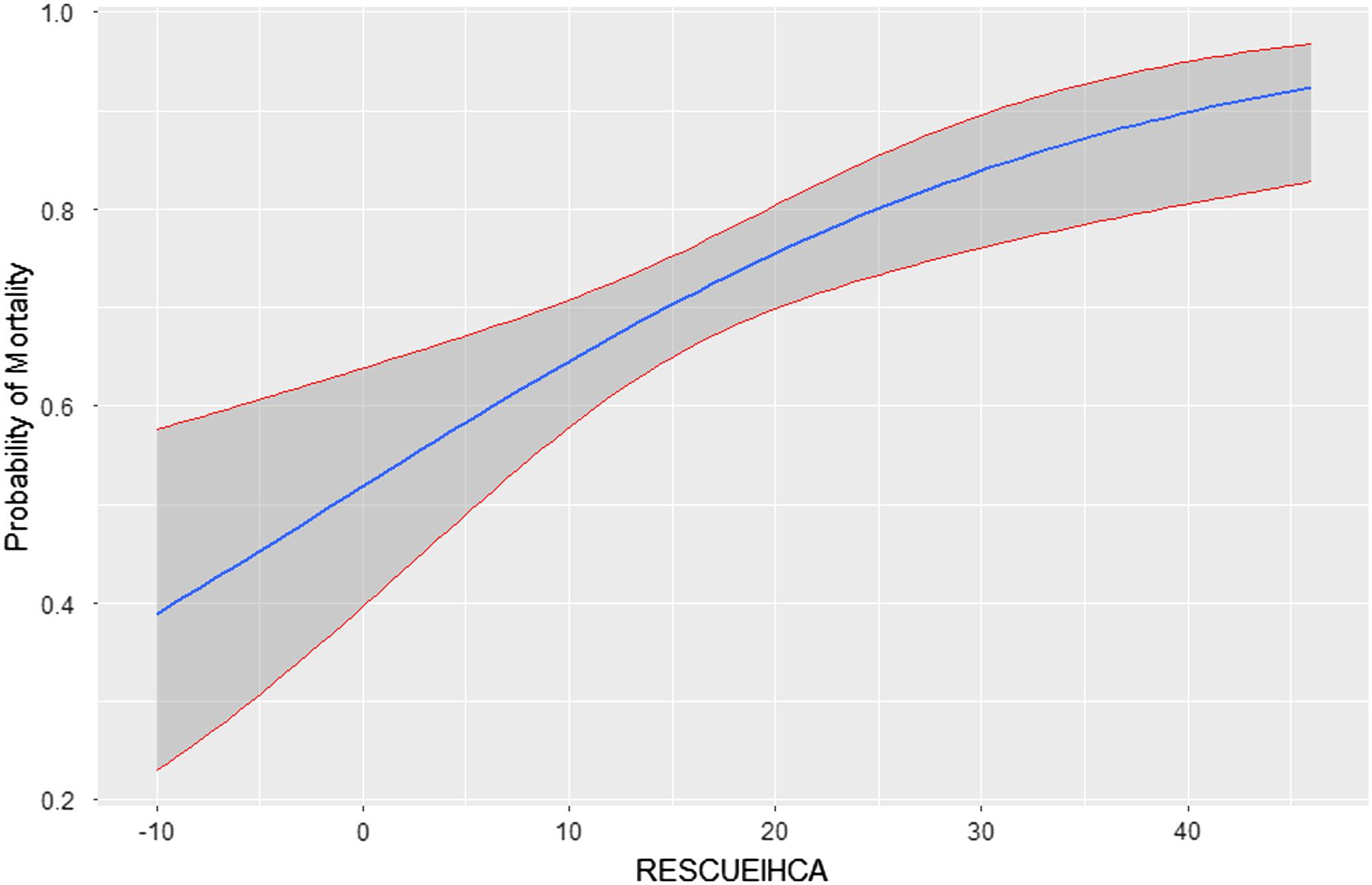

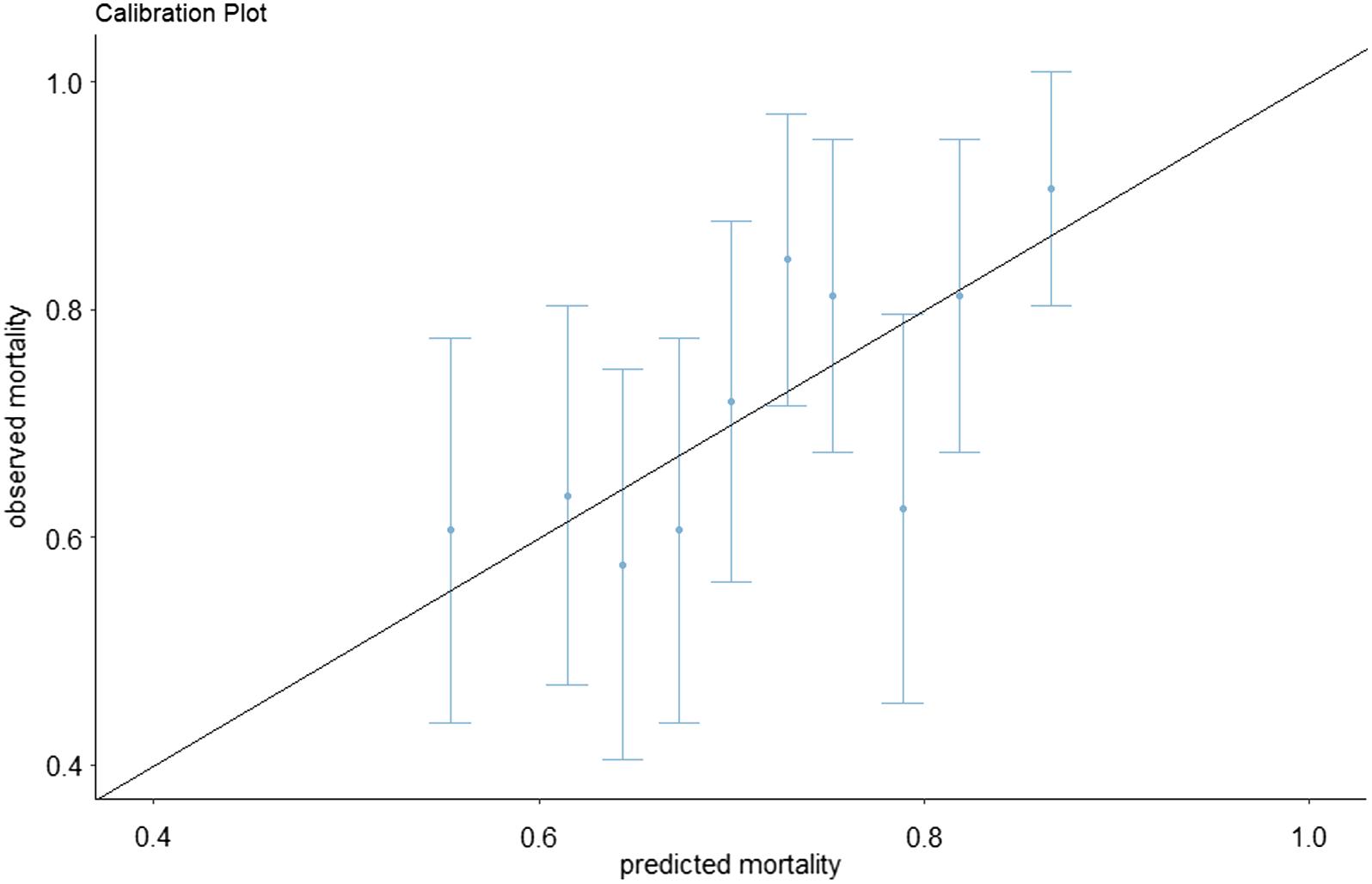

894 External Validation of the RESCUE-IHCA Score as a Predictor for In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Patients Receiving Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

Yi-Ju Ho, Pei-I Su, Chien-Yu Chi, Min-Shan Tsai, Yih-Sharng Chen, Chien-Hua Huang

Contents continued on page iii

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

Andrew W. Phillips, MD, Associate Editor DHR Health-Edinburg, Texas

Edward Michelson, MD, Associate Editor Texas Tech University- El Paso, Texas

Dan Mayer, MD, Associate Editor Retired from Albany Medical College- Niskayuna, New York

Wendy Macias-Konstantopoulos, MD, MPH, Associate Editor Massachusetts General Hospital- Boston, Massachusetts

Gayle Galletta, MD, Associate Editor University of Massachusetts Medical SchoolWorcester, Massachusetts

Yanina Purim-Shem-Tov, MD, MS, Associate Editor Rush University Medical Center-Chicago, Illinois

Section Editors

Behavioral Emergencies

Leslie Zun, MD, MBA

Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science

Marc L. Martel, MD

Hennepin County Medical Center

Cardiac Care

Fred A. Severyn, MD University of Colorado School of Medicine

Sam S. Torbati, MD

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center

Clinical Practice

Cortlyn W. Brown, MD Carolinas Medical Center

Casey Clements, MD, PhD Mayo Clinic

Patrick Meloy, MD

Emory University

Nicholas Pettit, DO, PhD Indiana University

David Thompson, MD University of California, San Francisco

Kenneth S. Whitlow, DO Kaweah Delta Medical Center

Critical Care

Christopher “Kit” Tainter, MD University of California, San Diego

Gabriel Wardi, MD University of California, San Diego

Joseph Shiber, MD University of Florida-College of Medicine

Matt Prekker MD, MPH Hennepin County Medical Center

David Page, MD University of Alabama

Erik Melnychuk, MD

Geisinger Health

Quincy Tran, MD, PhD University of Maryland

Disaster Medicine

John Broach, MD, MPH, MBA, FACEP University of Massachusetts Medical School

UMass Memorial Medical Center

Christopher Kang, MD Madigan Army Medical Center

Education

Danya Khoujah, MBBS University of Maryland School of Medicine University of Colorado

Michael Epter, DO

Mark I. Langdorf, MD, MHPE, Editor-in-Chief University of California, Irvine School of MedicineIrvine, California

University of California, Irvine School of MedicineIrvine, California

Michael Gottlieb, MD, Associate Editor Rush Medical Center-Chicago, Illinois

Niels K. Rathlev, MD, Associate Editor Tufts University School of Medicine-Boston, Massachusetts

Rick A. McPheeters, DO, Associate Editor

R. Gentry Wilkerson, MD, Associate Editor University of Maryland

Maricopa Medical Center

ED Administration, Quality, Safety

Tehreem Rehman, MD, MPH, MBA Mount Sinai Hospital

David C. Lee, MD Northshore University Hospital

Gary Johnson, MD Upstate Medical University

Brian J. Yun, MD, MBA, MPH Harvard Medical School

Laura Walker, MD Mayo Clinic

León D. Sánchez, MD, MPH

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

William Fernandez, MD, MPH University of Texas Health-San Antonio

Robert Derlet, MD

Founding Editor, California Journal of Emergency Medicine University of California, Davis

Emergency Medical Services

Daniel Joseph, MD

Yale University

Joshua B. Gaither, MD University of Arizona, Tuscon

Julian Mapp

University of Texas, San Antonio

Shira A. Schlesinger, MD, MPH Harbor-UCLA Medical Center

Geriatrics

Cameron Gettel, MD Yale School of Medicine

Stephen Meldon, MD

Cleveland Clinic

Luna Ragsdale, MD, MPH Duke University

Health Equity

Emily C. Manchanda, MD, MPH

Boston University School of Medicine

Faith Quenzer

Temecula Valley Hospital San Ysidro Health Center

Payal Modi, MD MScPH University of Massachusetts Medical

Infectious Disease

Elissa Schechter-Perkins, MD, MPH

Boston University School of Medicine

Ioannis Koutroulis, MD, MBA, PhD

George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences

Stephen Liang, MD, MPHS

Shadi Lahham, MD, MS, Deputy Editor Kaiser Permanente- Irvine, California

Susan R. Wilcox, MD, Associate Editor Massachusetts General Hospital- Boston, Massachusetts

Elizabeth Burner, MD, MPH, Associate Editor University of Southern California- Los Angeles, California

Patrick Joseph Maher, MD, MS, Associate Editor Ichan School of Medicine at Mount Sinai- New York, New York

Donna Mendez, MD, EdD, Associate Editor University of Texas-Houston/McGovern Medical School- Houston Texas

Danya Khoujah, MBBS, Associate Editor University of Maryland School of Medicine- Baltimore, Maryland

Washington University School of Medicine

Victor Cisneros, MD, MPH Eisenhower Medical Center

Injury Prevention

Mark Faul, PhD, MA Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Wirachin Hoonpongsimanont, MD, MSBATS

Eisenhower Medical Center

International Medicine

Heather A.. Brown, MD, MPH Prisma Health Richland

Taylor Burkholder, MD, MPH Keck School of Medicine of USC

Christopher Greene, MD, MPH University of Alabama

Chris Mills, MD, MPH Santa Clara Valley Medical Center

Shada Rouhani, MD

Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Legal Medicine

Indiana University School of Medicine

Statistics and Methodology

Shu B. Chan MD, MS Resurrection Medical Center

Stormy M. Morales Monks, PhD, MPH

Texas Tech Health Science University

Soheil Saadat, MD, MPH, PhD University of California, Irvine

James A. Meltzer, MD, MS Albert Einstein College of Medicine

Musculoskeletal

Juan F. Acosta DO, MS

Rick Lucarelli, MD Medical City Dallas Hospital

William D. Whetstone, MD University of California, San Francisco

Neurosciences

Antonio Siniscalchi, MD Annunziata Hospital, Cosenza, Italy

Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Paul Walsh, MD, MSc University of California, Davis

Muhammad Waseem, MD Lincoln Medical & Mental Health Center

Cristina M. Zeretzke-Bien, MD University of Florida

Public Health

Henry Ford Hospital

John Ashurst, DO Lehigh Valley Health Network

Tony Zitek, MD Kendall Regional Medical Center

Trevor Mills, MD, MPH Northern California VA Health Care

Erik S. Anderson, MD Alameda Health System-Highland Hospital

Technology in Emergency Medicine

Nikhil Goyal, MD Henry Ford Hospital

Phillips Perera, MD Stanford University Medical Center

Trauma

Pierre Borczuk, MD

Massachusetts General Hospital/Havard Medical School

Toxicology

Brandon Wills, DO, MS Virginia Commonwealth University

University of California, Irvine

Ultrasound J. Matthew Fields, MD

Shane Summers, MD Brooke Army Medical Center

Robert R. Ehrman Wayne State University

Ryan C. Gibbons, MD Temple Health

Journal of the California Chapter of the American College of Emergency Physicians, the America College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians, and the California Chapter of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Western Journal of Emergency : Integrating Emergency with Population Health

Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

Amin A. Kazzi, MD, MAAEM

Amin A. Kazzi, MD, MAAEM

Gayle Galleta, MD

Gayle Galleta, MD

The American University of Beirut, Lebanon

Beirut,

The American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon

Brent King, MD, MMM University of Texas, Houston

Brent King, MD, MMM University Texas, Houston

Christopher E. San Miguel, Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center

Christopher E. San Miguel, MD Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center

Christopher E. San Miguel, MD Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center

Daniel J. Dire, MD

Daniel J. Dire, MD University of Texas Health Sciences Center San Antonio

Daniel J. Dire, MD University Texas Health Sciences Center San Antonio

Douglas Ander, Emory University

Emory University

Douglas Ander, MD Emory University

Edward Michelson, MD Texas Tech University

Edward Michelson, Texas Tech University

Edward Michelson, MD Texas Tech University

Edward Panacek, MD, MPH South

Edward MD, MPH University South Alabama

Edward Panacek, MD, MPH University of South Alabama

Francesco

“Maggiore della Carità,” Novara, Italy

Francesco Della Corte, MD Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria “Maggiore della Novara, Italy

Francesco Della Corte, MD Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria “Maggiore della Carità,” Novara, Italy

Sørlandet Sykehus HF, Akershus Universitetssykehus, Lorenskog,

Hjalti Björnsson, MD

Editorial Board Board

Editorial Board Sørlandet Sykehus HF, Akershus Universitetssykehus, Lorenskog, Norway

Sørlandet Sykehus HF, Akershus Universitetssykehus, Lorenskog, Norway

Hjalti Björnsson, MD Icelandic Society of Emergency Medicine

Hjalti MD Icelandic Society of Emergency Medicine

Jaqueline Le, MD Desert Regional Medical Center

Jaqueline Le, MD Desert Medical Center

Regional

Jeffrey Love, MD

Jeffrey Love, MD The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences

Jeffrey Love, The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences

Katsuhiro Kanemaru, MD University of Hospital, Miyazaki, Japan

Katsuhiro Kanemaru, MD University of Miyazaki Hospital, Miyazaki, Japan

Kenneth V. Iserson, MD, MBA University of Arizona, Tucson

Kenneth V. Iserson, MD, MBA University of Arizona, Tucson

Leslie Zun, MD, MBA Chicago Medical School

Leslie Zun, MD, MBA Chicago Medical School

Linda S. Murphy, MLIS University of California, Irvine School of Medicine

The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences Arizona, Chicago Medical School Librarian

Linda S. Murphy, MLIS University of California, Irvine School of Medicine Librarian

Advisory Board Elena Lopez-Gusman, JD

Elena Lopez-Gusman, JD

California ACEP

Elena Lopez-Gusman, JD California ACEP

California ACEP

Mark I. Langdorf, MD, MHPE, MAAEM, FACEP

Langdorf, MAAEM, FACEP

Tufts University School of Medicine

Niels K. Rathlev, Tufts University School of Medicine

Niels K. Rathlev, MD Tufts University School of Medicine

Scott Zeller, MD

Scott Zeller, MD University of California, Riverside

Scott Zeller, MD University of California, Riverside

Pablo Aguilera Fuenzalida, MD Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Bell,

Pablo Aguilera Fuenzalida, MD Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Región Metropolitana, Chile

Pablo Aguilera Fuenzalida, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Región Metropolitana, Chile

Peter A. Bell, DO, MBA Baptist Health Sciences University

Peter A. Bell, DO, MBA Baptist Health University

Peter Sokolove, MD University of California, Francisco

Peter Sokolove, MD University of California, San Francisco

University of California, San Francisco

Rachel A. Lindor, MD, JD

Rachel A. Lindor, MD, JD Mayo Clinic

Rachel A. Lindor, MD, JD Mayo Clinic

Robert Suter, DO, MHA

Robert Suter, DO, UT Southwestern Medical Center

Robert Suter, DO, MHA UT Southwestern Medical Center

Robert W. Derlet, MD University of California, Davis

Robert W. Derlet, MD University of California, Davis

University of California, Davis

Rosidah Ibrahim, MD Hospital Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia

Rosidah Ibrahim, MD Hospital Serdang, Malaysia

Rosidah Ibrahim, MD Hospital Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia

Scott Rudkin, MD, MBA

Scott Rudkin, MD, University of California, Irvine

Scott Rudkin, MD, MBA University of California, Irvine

Steven H. Lim, MD Changi General Hospital, Simei, Singapore

Singapore

Steven H. Lim, Changi General Hospital, Simei, Singapore

Terry Mulligan, DO, MPH, FIFEM ACEP Ambassador to the Netherlands Society of Emergency Physicians

Terry Mulligan, DO, MPH, FIFEM ACEP Ambassador to the Netherlands

Terry Mulligan, DO, MPH, FIFEM ACEP to the Netherlands Society of Emergency Physicians

Wirachin Hoonpongsimanont, MD, MSBATS

Wirachin Hoonpongsimanont, MD, MSBATS

Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand

Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand

Editorial Staff Staff Advisory Board Isabelle BS Executive Editorial Director

Isabelle Nepomuceno, BS Executive Editorial Director

American of Emergency Physicians

American College of Emergency

American College of Emergency Physicians

Jennifer Kanapicki Comer, MD FAAEM

Jennifer Kanapicki Comer, MD FAAEM

California Chapter Division of AAEM Stanford University School of Medicine

California Chapter Division of AAEM Stanford University School of Medicine

DeAnna McNett, CAE

Kimberly Ang, MBA

DeAnna McNett, CAE

American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians

American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians

UC Irvine Health School of Medicine

Randall J. Young, MD, MMM, FACEP California ACEP

Kimberly Ang, MBA

UC Irvine Health School of Medicine

American College of Emergency Physicians Kaiser Permanente

J. American College of Emergency Physicians Kaiser Permanente

Randall J. Young, MD, MMM, FACEP California ACEP American College of Emergency Physicians Kaiser Permanente

in

UC Irvine Health School of Medicine

UC Irvine Health School of Medicine

Mark I. Langdorf, MD, MHPE, MAAEM, FACEP

UC Irvine Health School of Medicine

Robert Suter, DO, MHA American College of Osteopathic

Robert Suter, DO, MHA American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians UT Southwestern Medical Center

Robert Suter, DO, MHA American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians UT Southwestern Medical Center

Shahram Lotfipour, MD, MPH FAAEM, FACEP

UC Irvine Health School of Medicine

Shahram Lotfipour, MD, MPH FAAEM, FACEP UC Irvine Health School of Medicine

Jorge Fernandez, MD, FACEP

Jorge Fernandez, MD, FACEP

Jorge Fernandez, MD, FACEP

UC San Diego Health School of Medicine

UC San Diego Health School of Medicine

UC San Diego Health School of Medicine

Visha Bajaria, BS WestJEM Editorial Director

Visha Bajaria, BS WestJEM Editorial Director

Emily Kane, MA WestJEM Editorial Director

Emily Kane, MA WestJEM Editorial Director

Stephanie Burmeister, MLIS JEM Liaison

Visha Bajaria, BS WestJEM Editorial Director WestJEM

Stephanie Burmeister, MLIS WestJEM Staff Liaison

Cassandra Saucedo, MS Executive Publishing Director

Cassandra Saucedo, MS Executive Publishing Director

Nicole Valenzi, BA WestJEM Publishing Director

Cassandra Saucedo, MS WestJEM Publishing Director

Nicole Valenzi, WestJEM Publishing Director

June Casey, BA Copy Editor

June Casey, BA Copy Editor

Official Journal of the California Chapter of the American College of Emergency Physicians, the America College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians, and the California Chapter of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Available in MEDLINE, PubMed, PubMed Central, Europe PubMed Central, PubMed Central Canada, CINAHL, SCOPUS, Google Scholar, eScholarship, Melvyl, DOAJ, EBSCO, EMBASE, Medscape, HINARI, and MDLinx Emergency Med. Members of OASPA. Editorial and Publishing Office: WestJEM/Depatment of Emergency Medicine, UC Irvine Health, 3800 W. Chapman Ave. Suite 3200, Orange, CA 92868, USA Office: 1-714-456-6389; Email: Editor@westjem.org

Editorial and Publishing Office: JEM/Depatment of Emergency Medicine, UC Irvine Health, 3800 W. Chapman Ave. Suite 3200, Orange, CA 92868, USA

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

JOURNAL FOCUS Emergency medicine is a specialty which closely reflects societal challenges and consequences of public policy decisions. The emergency department specifically deals with social injustice, health and economic disparities, violence, substance abuse, and disaster preparedness and response. This journal focuses on how emergency care affects the health of the community and population, and conversely, how these societal challenges affect the composition of the patient population who seek care in the emergency department. The development of better systems to provide emergency care, including technology solutions, is critical to enhancing population health.

Table of Contents Education

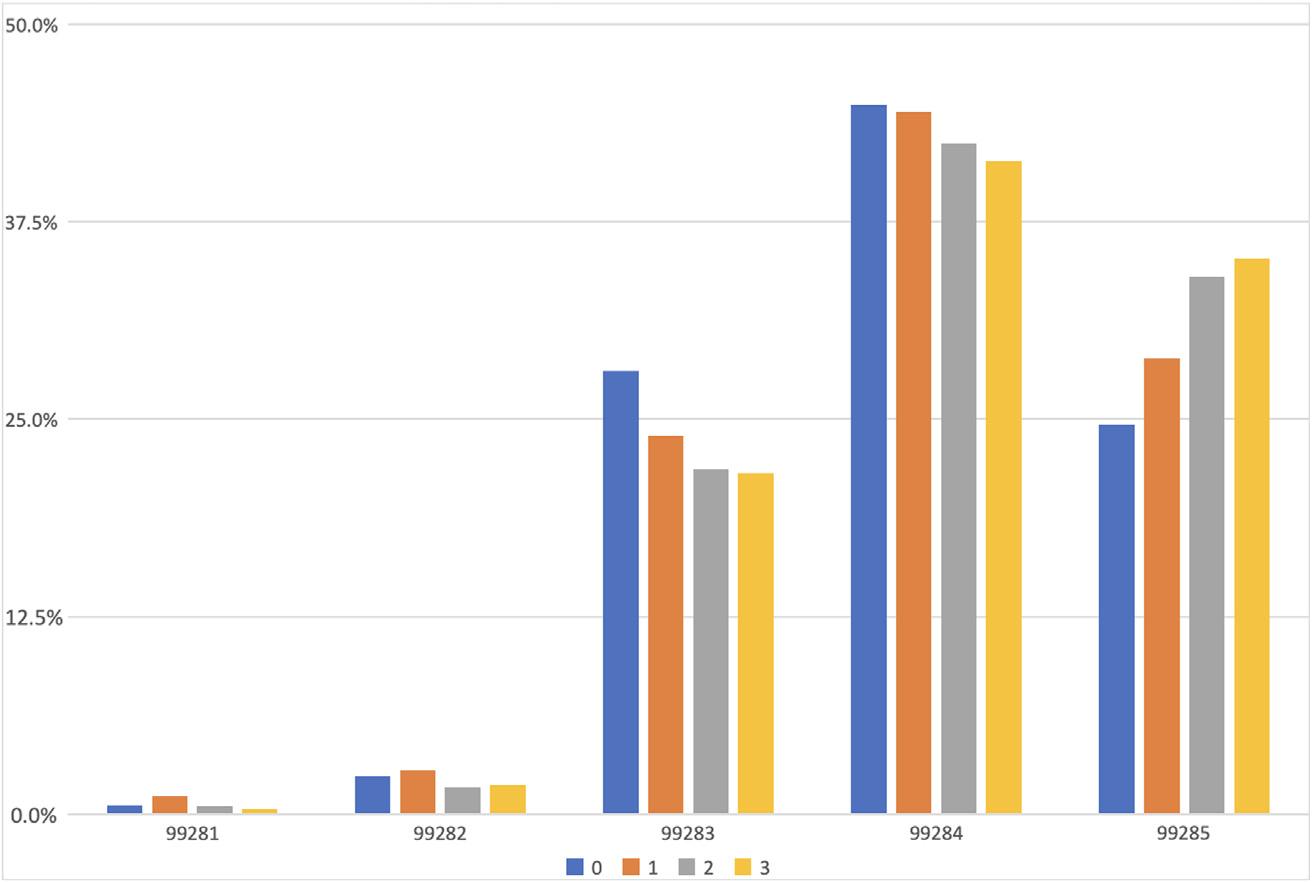

903 Teaching the New Ways: Improving Resident Documentation for the New 2023 Coding Requirements

Nathan Zapolsky, Annemarie Cardell, Riddhi Desai, Stacey Frisch, Nicholas Jobeun, Daniel Novak, Michael Silver, Arlene S. Chung

907 Telesimulation Use in Emergency Medicine Residency Programs: National Survey of Residency Simulation Leaders

Max Berger, Jack Buckanavage, Jaime Jordan, Steven Lai, Linda Regan

913 Palliative Care Boot Camp Offers Skill Building for Emergency Medicine Residents

Julie Cooper, Jenna Fredette

Emergency Department Operations

917 Improving Patient Understanding of Emergency Department Discharge Instructions

Sarah Russell, Nancy Jacobson, Ashley Pavlic

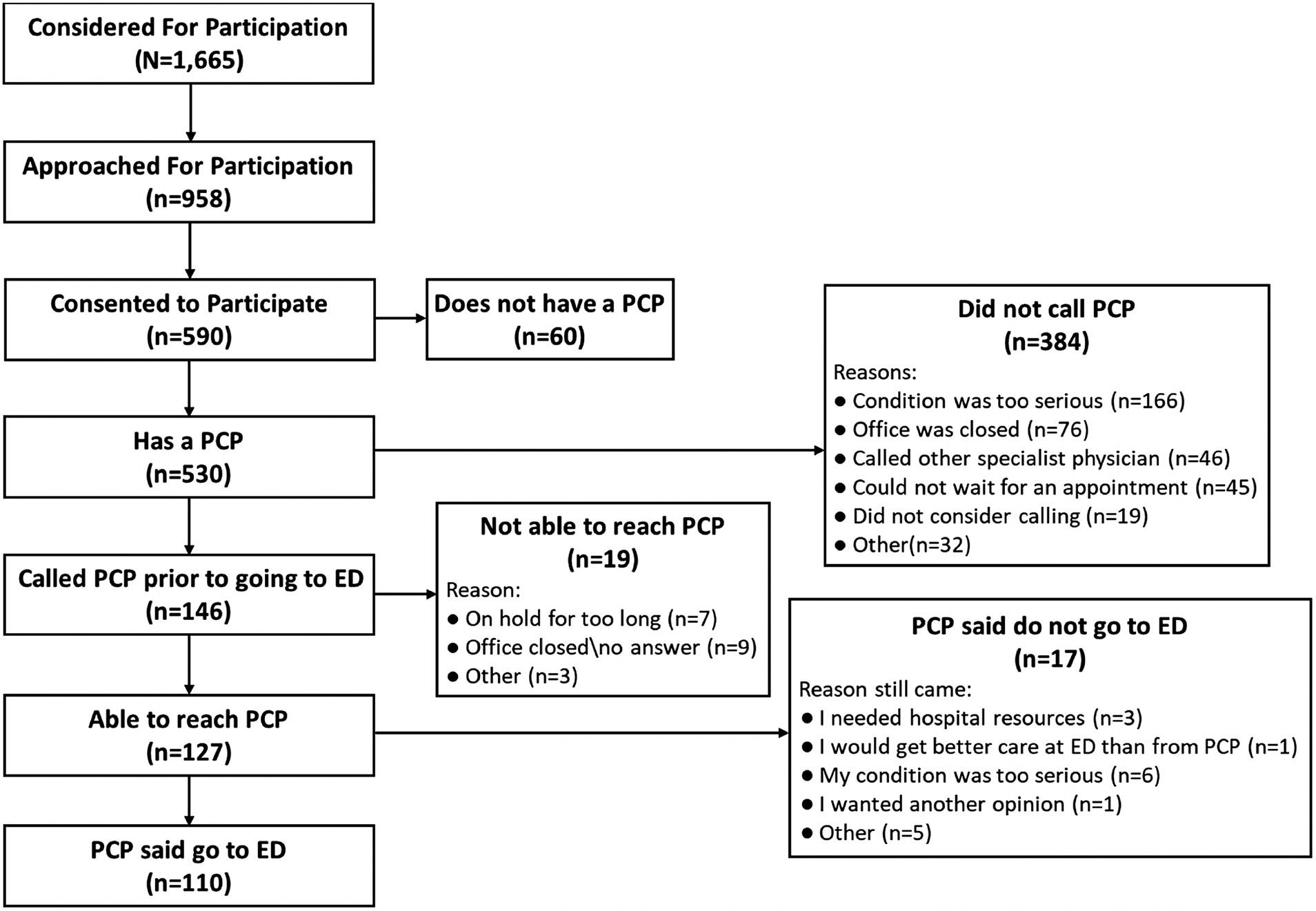

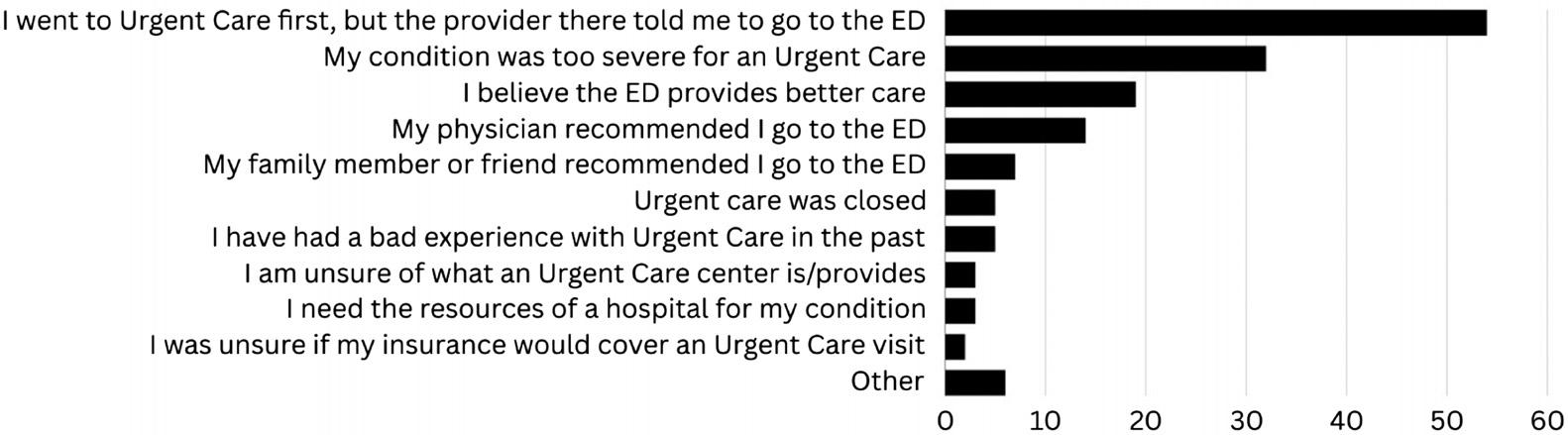

921 Why Do Patients Opt for the Emergency Department over Other Care Choices? A Multi-Hospital Analysis

Charles W. Stube, Alexander S. Ljungberg, Jason A. Borton, Kunal Chadha, Kyle J. Kelleran, E. Brooke Lerner

929 Emergency Department Patient Satisfaction Scores Are Lower for Patients Who Arrive During the Night Shift

Tony Zitek, Luke Weber, Tatiana Nuñez, Luis Puron, Adam Roitman, Claudia Corbea, Dana Sherman, Michael Shalaby, Frayda Kresch, David A. Farcy

938 Comparison of Emergency Department Disposition Times in Adult Level I and Level II Trauma Centers

Sierra Lane, Jeffry Nahmias, Michael Lekawa, John Christian Fox, Carrie Chandwani, Shahram Lotfipour, Areg Grigorian

946 Weighing In

Iyesatta M. Emeli, Patrick G. Meloy

Emergency Medical Services

949 Perceptions and Use of Automated Hospital Outcome Data by EMS Providers: A Pilot Study

Michael Kaduce, Antonio Fernandez, Scott Bourn, Dustin Calhoun, Jefferson Williams, Mallory DeLuca, Heidi Abraham, Kevin Uhl, Brian Bregenzer, Baxter Larmon, Remle P. Crowe, Alison Treichel, J. Brent Myers

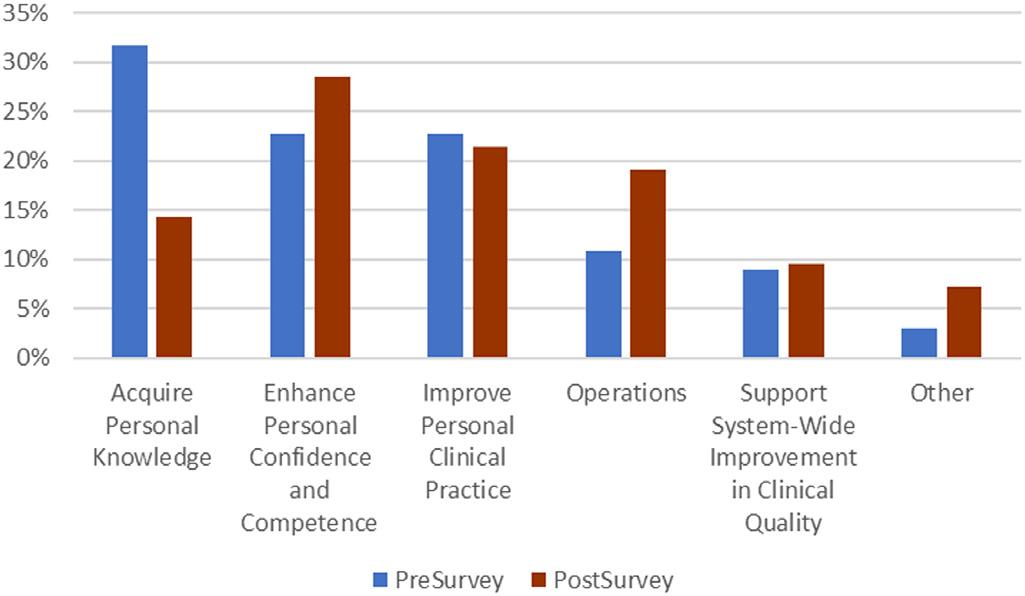

958 Validation of the Turkish Version of the Professional Fulfillment Index

Merve Eksioglu, Ayca Koca, Burcu Azapoglu Kaymak, Tuba Cimilli Ozturk, Atilla Halil Elhan

Policies for peer review, author instructions, conflicts of interest and human and animal subjects protections can be found online at www.westjem.com.

No. 6: November 2024

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

Table of Contents continued Endemic Infection

966 Use of Parenteral Antibiotics in Emergency Departments: Practice Patterns and Class Concordance

Megan Elli, Timothy Molinarolo, Aidan Mullan, Laura Walker

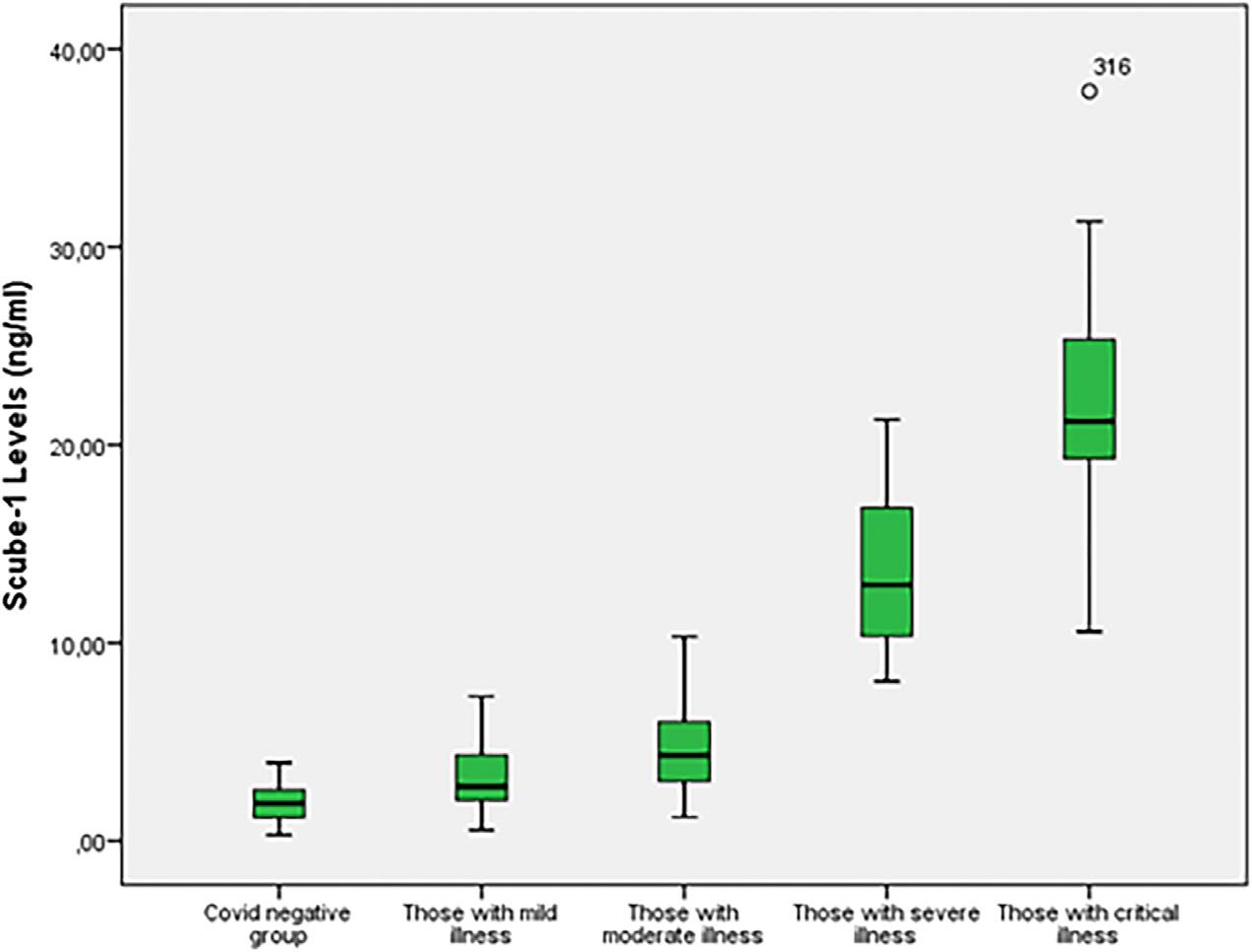

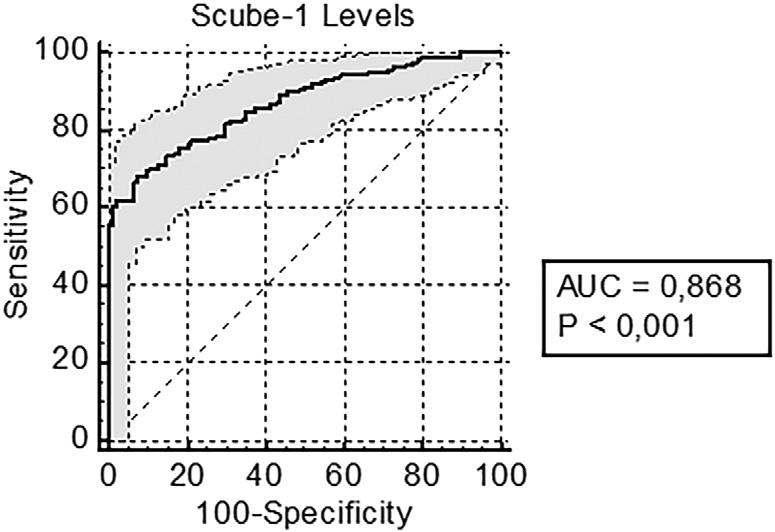

975 Diagnostic and Prognostic Value of SCUBE-1 in COVID-19 Patients

Vildan Ozer, Ozgen Gonenc Cekic, Ozlem Bulbul, Davut Aydın, Eser Bulut, Firdevs Aksoy, Mehtap Pehlivanlar Kucuk, Suleyman Caner Karahan, Ebru Emel Sozen, Esra Ozkaya, Polat Kosucu, Yunus Karaca, Suleyman Turedi

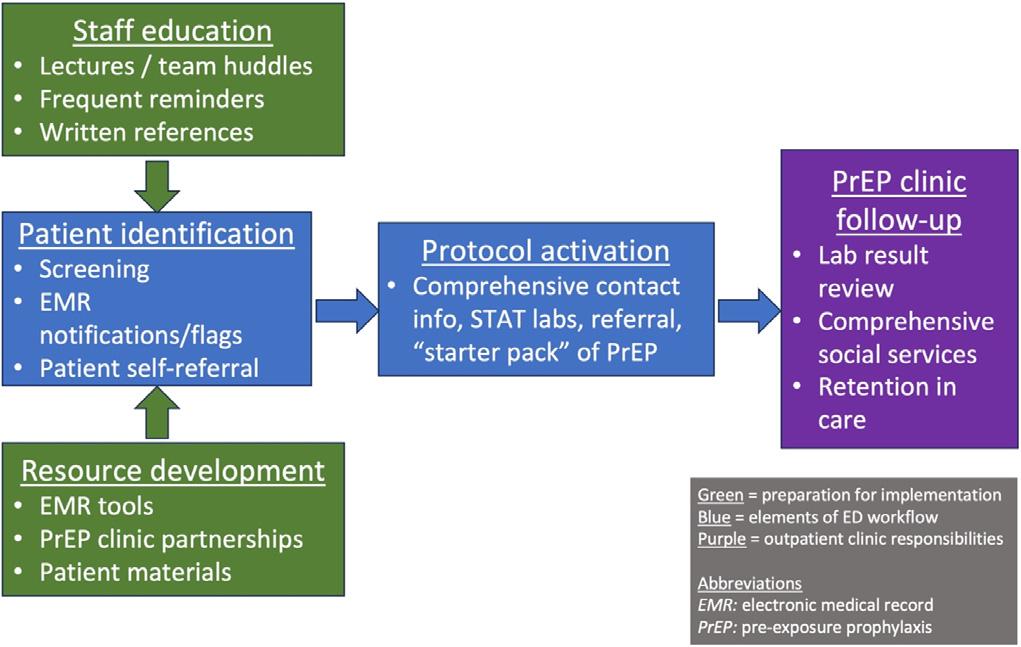

985 Feasibility of Emergency Department-Initiated HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis

Ezra Bisom-Rapp, Kishan Patel, Katrin Jaradeh, Tuna C. Hayirli, Christopher R. Peabody

Health Equity

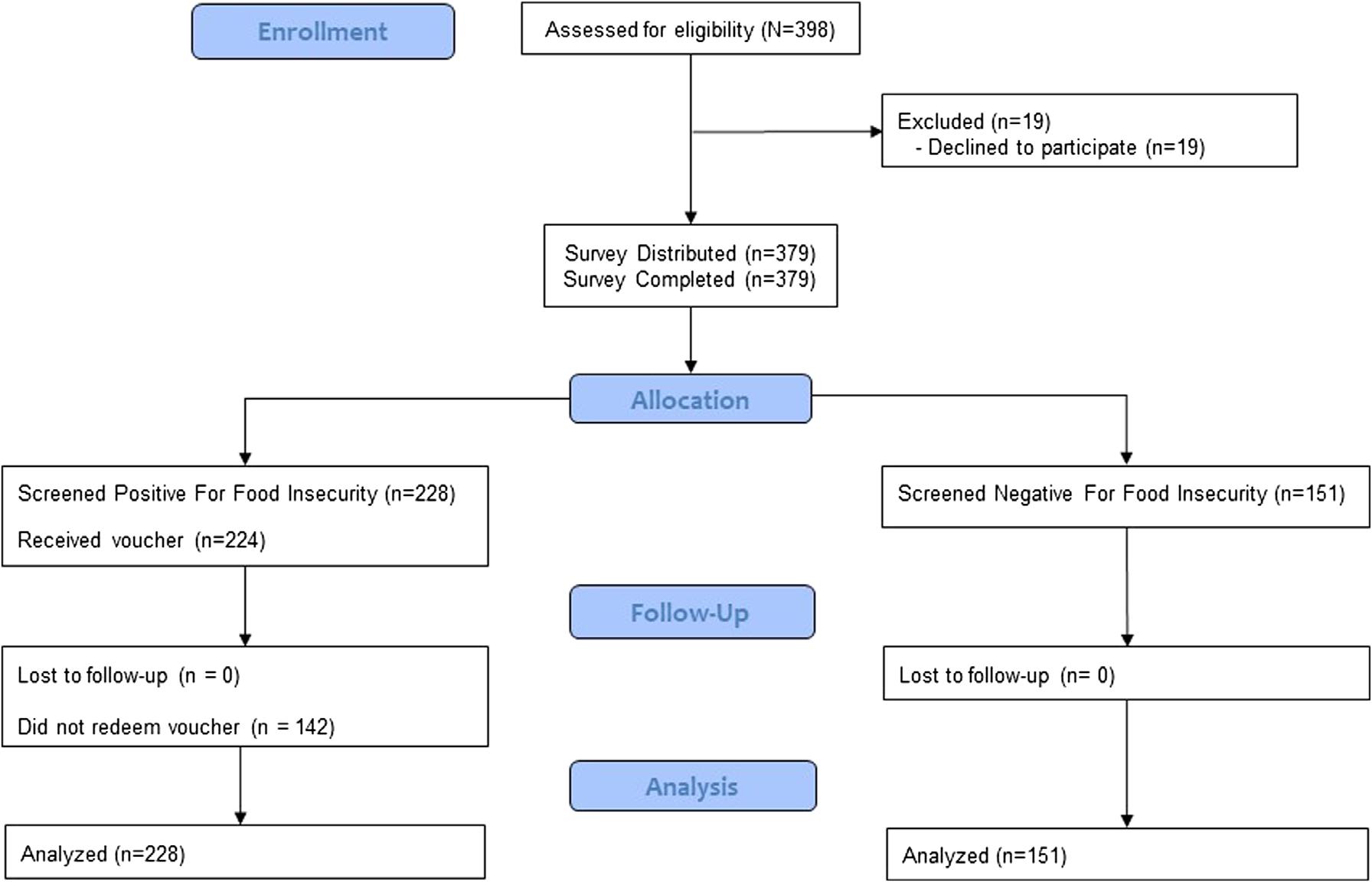

993 Emergency Department Food Insecurity Screening, Food Voucher Distribution and Utilization: A Prospective Cohort Study

Alexander J. Ulintz, Seema S. Patel, Katherine Anderson, Kevin Walters, Tyler J. Stepsis, Michael S. Lyons, Peter S. Pang

Health Policy Perspectives

1000 The California Managed Care Organization Tax and Medi-Cal Patients in the Emergency Department

Lauren Murphy, Gita Golonzka, Ellen Shank, Jorge Fernandez

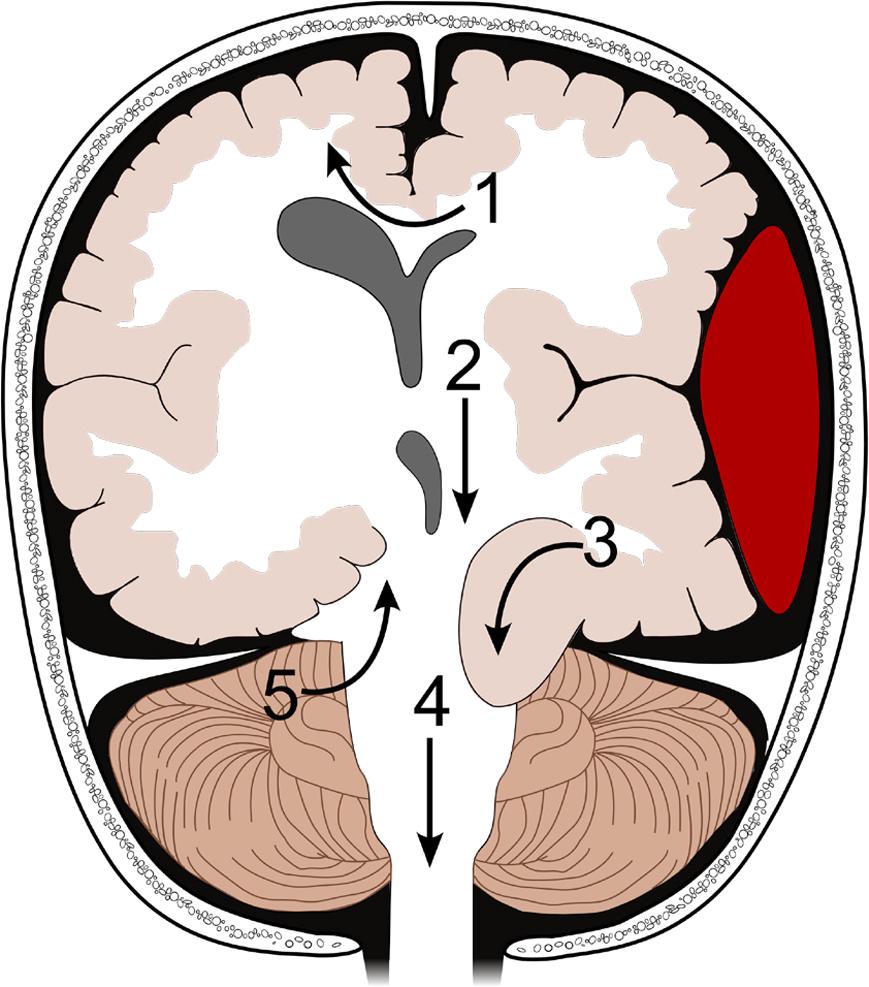

Neurology

1003 A Review of the Clinical Presentation, Causes, and Diagnostic Evaluation of Increased Intracranial Pressure in the Emergency Department

Cristiana Olaru, Sam Langberg, Nicole Streiff McCoin

Pediatrics

1011 Barriers to Adoption of a Child-Abuse Clinical Decision Support System in Emergency Departments

Alanna C. Peterson, Donald M. Yealy, Emily Heineman, Rachel P. Berger

1020 Reframing Child Protection in Emergency Medicine

Joseph P. Shapiro, Genevieve Preer, Caroline J. Kistin

Letters to the Editor

1025 Comments on “Bicarbonate and Serum Lab Markers as Predictors of Mortality in the Trauma Patient”

Patrick McGinnis, Samantha Camp, Minahil Cheema, Shriya Jaddu, Quincy Tran, Jessica Downing

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

This open access publication would not be possible without the generous and continual financial support of our society sponsors, department and chapter subscribers.

Professional Society Sponsors

American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians

California American College of Emergency Physicians

Academic Department of Emergency Medicine Subscriber Albany Medical College Albany, NY

Allegheny Health Network Pittsburgh, PA

American University of Beirut Beirut, Lebanon

AMITA Health Resurrection Medical Center Chicago, IL

Arrowhead Regional Medical Center Colton, CA

Baylor College of Medicine Houston, TX

Baystate Medical Center Springfield, MA

Bellevue Hospital Center New York, NY

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Boston, MA

Boston Medical Center Boston, MA

Brigham and Women’s Hospital Boston, MA

Brown University Providence, RI

Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center Fort Hood, TX

Cleveland Clinic Cleveland, OH

Columbia University Vagelos New York, NY

State Chapter Subscriber

Arizona Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

California Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Florida Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

International Society Partners

Conemaugh Memorial Medical Center Johnstown, PA

Crozer-Chester Medical Center Upland, PA

Desert Regional Medical Center Palm Springs, CA

Detroit Medical Center/ Wayne State University Detroit, MI

Eastern Virginia Medical School Norfolk, VA

Einstein Healthcare Network Philadelphia, PA

Eisenhower Medical Center Rancho Mirage, CA

Emory University Atlanta, GA

Franciscan Health Carmel, IN

Geisinger Medical Center Danville, PA

Grand State Medical Center Allendale, MI

Healthpartners Institute/ Regions Hospital Minneapolis, MN

Hennepin County Medical Center Minneapolis, MN

Henry Ford Medical Center Detroit, MI

Henry Ford Wyandotte Hospital Wyandotte, MI

Emergency Medicine Association of Turkey Lebanese Academy of Emergency Medicine Mediterranean Academy of Emergency Medicine

California Chapter Division of American Academy of Emergency Medicine

INTEGRIS Health Oklahoma City, OK

Kaiser Permenante Medical Center San Diego, CA

Kaweah Delta Health Care District Visalia, CA

Kennedy University Hospitals Turnersville, NJ

Kent Hospital Warwick, RI

Kern Medical Bakersfield, CA

Lakeland HealthCare St. Joseph, MI

Lehigh Valley Hospital and Health Network Allentown, PA

Loma Linda University Medical Center Loma Linda, CA

Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center New Orleans, LA

Louisiana State University Shreveport Shereveport, LA

Madigan Army Medical Center Tacoma, WA

Maimonides Medical Center Brooklyn, NY

Maine Medical Center Portland, ME

Massachusetts General Hospital/Brigham and Women’s Hospital/ Harvard Medical Boston, MA

Great Lakes Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Tennessee Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Norwegian Society for Emergency Medicine Sociedad Argentina de Emergencias

Mayo Clinic Jacksonville, FL

Mayo Clinic College of Medicine Rochester, MN

Mercy Health - Hackley Campus Muskegon, MI

Merit Health Wesley Hattiesburg, MS

Midwestern University Glendale, AZ

Mount Sinai School of Medicine New York, NY

New York University Langone Health New York, NY

North Shore University Hospital Manhasset, NY

Northwestern Medical Group Chicago, IL

NYC Health and Hospitals/ Jacobi New York, NY

Ohio State University Medical Center Columbus, OH

Ohio Valley Medical Center Wheeling, WV

Oregon Health and Science University Portland, OR

Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center Hershey, PA

Uniformed Services Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Virginia Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

for Emergency Medicine

To become a WestJEM departmental sponsor, waive article processing fee, receive electronic copies for all faculty and residents, and free CME and faculty/fellow position advertisement space, please go to http://westjem.com/subscribe or contact:

Stephanie Burmeister

WestJEM Staff Liaison

Phone: 1-800-884-2236

Email: sales@westjem.org

25, No. 6: November 2024

Sociedad Chileno Medicina Urgencia Thai Association

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

This open access publication would not be possible without the generous and continual financial support of our society sponsors, department and chapter subscribers.

Professional Society Sponsors

American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians

California American College of Emergency Physicians

Academic Department of Emergency Medicine Subscriber Prisma Health/ University of South Carolina SOM Greenville Greenville, SC

Regions Hospital Emergency Medicine Residency Program St. Paul, MN

Rhode Island Hospital Providence, RI

Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital New Brunswick, NJ

Rush University Medical Center Chicago, IL

St. Luke’s University Health Network Bethlehem, PA

Spectrum Health Lakeland St. Joseph, MI

Stanford Stanford, CA

SUNY Upstate Medical University Syracuse, NY

Temple University Philadelphia, PA

Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center El Paso, TX

The MetroHealth System/ Case Western Reserve University Cleveland, OH

UMass Chan Medical School Worcester, MA

University at Buffalo Program Buffalo, NY

State Chapter Subscriber

Arizona Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

California Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Florida Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

International Society Partners

University of Alabama Medical Center Northport, AL

University of Alabama, Birmingham Birmingham, AL

University of Arizona College of Medicine-Tucson Tucson, AZ

University of California, Davis Medical Center Sacramento, CA

University of California, Irvine Orange, CA

University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA

University of California, San Diego La Jolla, CA

University of California, San Francisco San Francisco, CA

UCSF Fresno Center Fresno, CA

University of Chicago Chicago, IL

University of Cincinnati Medical Center/ College of Medicine Cincinnati, OH

University of Colorado Denver Denver, CO

University of Florida Gainesville, FL

University of Florida, Jacksonville Jacksonville, FL

Emergency Medicine Association of Turkey Lebanese Academy of Emergency Medicine Mediterranean Academy of Emergency Medicine

California Chapter Division of American Academy of Emergency Medicine

University of Illinois at Chicago Chicago, IL

University of Iowa Iowa City, IA

University of Louisville Louisville, KY

University of Maryland Baltimore, MD

University of Massachusetts Amherst, MA

University of Michigan Ann Arbor, MI

University of Missouri, Columbia Columbia, MO

University of North Dakota School of Medicine and Health Sciences Grand Forks, ND

University of Nebraska Medical Center Omaha, NE

University of Nevada, Las Vegas Las Vegas, NV

University of Southern Alabama Mobile, AL

University of Southern California Los Angeles, CA

University of Tennessee, Memphis Memphis, TN

University of Texas, Houston Houston, TX

University of Washington Seattle, WA

Great Lakes Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Tennessee Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Norwegian Society for Emergency Medicine Sociedad Argentina de Emergencias

University of WashingtonHarborview Medical Center Seattle, WA

University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics Madison, WI

UT Southwestern Dallas, TX

Valleywise Health Medical Center Phoenix, AZ

Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center Richmond, VA

Wake Forest University Winston-Salem, NC

Wake Technical Community College Raleigh, NC

Wayne State Detroit, MI

Wright State University Dayton, OH

Yale School of Medicine New Haven, CT

Uniformed Services Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Virginia Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

for Emergency Medicine

To become a WestJEM departmental sponsor, waive article processing fee, receive electronic copies for all faculty and residents, and free CME and faculty/fellow position advertisement space, please go to http://westjem.com/subscribe or contact:

Stephanie Burmeister

WestJEM Staff Liaison

Phone: 1-800-884-2236

Email: sales@westjem.org

Sociedad Chileno Medicina Urgencia Thai Association

REVIEW RecentInterventionsforAcuteSuicidalityDeliveredinthe EmergencyDepartment:AScopingReview AlexP.Hood,BA*†

LaurenM.Tibbits,MD*

JuanI.Laporta,BS*

JenniferCarrillo,BS*

LaceeR.Adams,BS*

StaceyYoung-McCaughan,RN,PhD‡

AlanL.Peterson,PhD,ABPP‡§

RobertA.DeLorenzo,MD,MSM,MSCI*

SectionEditor:BradBobrin,MD

*UniversityofTexasHealthScienceCenteratSanAntonio, DepartmentofEmergencyMedicine,SanAntonio,Texas

† BaylorUniversity,DepartmentofPsychologyandNeuroscience, Waco,Texas

‡ UniversityofTexasHealthScienceCenteratSanAntonio,Department ofPsychiatryandBehavioralSciences,SanAntonio,Texas

§ UniversityofTexasatSanAntonio,DepartmentofPsychology, SanAntonio,Texas

Submissionhistory:SubmittedDecember21,2023;RevisionreceivedAugust12,2024;AcceptedAugust16,2024

ElectronicallypublishedOctober9,2024

Fulltextavailablethroughopenaccessat http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem DOI: 10.5811/westjem.18640

Introduction: SuicidalityisagrowingproblemintheUS,andtheemergencydepartment(ED)isoften thefrontlineforthemanagementandeffectivetreatmentofacutelysuicidalpatients.Thereisadearthof interventionsthatemergencyphysiciansmayusetomanageandeffectivelytreatacutelysuicidal patients.TotheextentthatrecentlydescribedinterventionsareavailableforEDpersonnel,noreview hasbeenconductedtoidentifythem.Thisscopingreviewisintendedto fillthisgapbysystematically reviewingtheliteraturetoidentifyrecentlydescribedinterventionsthatcanbeadministeredintheEDto reducesymptomsandstabilizepatients.

Methods: WeconductedasearchofPubMed,SCOPUS,andCINAHLinJanuary2024toidentify paperspublishedbetween2013–2023fororiginalresearchtrialingrecentinterventionsfortheeffective treatmentofsuicidalityintheED.Weassessed16full-textarticlesforeligibility,andninemetinclusion criteria.Includedstudieswereevaluatedforfeaturesandcharacteristics,the fitoftheinterventiontothe EDenvironment,andinterventionalefficacy.

Results: Fourstudiesassessedtheefficacyofasingledoseoftheanesthetic/analgesicagentketamine. Threestudiesassessedtheef ficacyofabriefpsychosocialinterventiondeliveredintheED,twoofwhich pairedthisinterventionwiththeprovisionoffollow-upcare(postcardcontactandreferralassistance/ casemanagement,respectively).Theremainingtwostudiestrialedabrief,motivationalinterviewingbasedintervention.Includedstudieshadstrongexperimentaldesigns(randomizedcontrolledtrials)but smallsamplesizes(average57).Amongtheinterventionsrepresentedacrosstheseninestudies,a singledoseofketamineandthebriefpsychosocialinterventionCrisisResponsePlanning(CRP)show promiseasED-appropriateinterventionsforsuicidality.KetamineandCRPdemonstratedthestrongest fittotheEDenvironmentandmostrobustefficacy findings.

Conclusion: Thisreviewidentifiedonedrug(ketamine)andfouruniquepsychological/behavioral interventionsthathavebeenusedtotreatacutesuicidalityintheED.Thereiscurrentlyinsufficient evidencetosuggestthattheseinterventionswillproveefficaciousandwell-suitedtobedeliveredinthe EDenvironment.FuturestudiesshouldcontinuetotesttheseinterventionsintheEDsettingtodetermine theirfeasibilityandefficacy.[WestJEmergMed.2024;25(6)858–868.]

INTRODUCTION Overthepasttwodecades,thesuiciderateintheUS generalpopulationincreasedbyover33%.1 Uptohalfof suicidedecedentsvisitanemergencydepartment(ED)during theyearbeforetheirdeath,andapproximately25%visitin themonthimmediatelyprior.2,3 Theriskfordeathbysuicide amongEDpatientspresentingwithsuicidalthoughtsand behaviorsremainshighforatleastoneyearafter discharge.4,5 TheEDisoftenthe firstmedicalaccesspointfor thosewithanacutedeteriorationintheirmentalhealth; approximately10%ofallEDvisitsareformentalhealth concerns. 5–7 Newandinnovativeapproachesareneededto stemthetideofsuicidesandtohelpmitigatethecrisisof psychiatricboardinginEDs.8,9

Emergencydepartmentpersonnelhaveincreasingly voicedconcernsoverabrokensystemofmentalhealthcare thathasexacerbatedconditionsforEDpatientswith psychiatricemergencies.10 Suchserioussystemdeficiencies maycontributetotheperceptionofsuicidalEDpatientswho describeEDpersonnelaslackingempathy,andbeing brusque,irritable,andevenhostile.11 Exacerbatingthe problemisthatthenumberofstate-fundedinpatient psychiatricbedshasdroppedsubstantially,from340beds per100,000peoplein1995tounder12bedsper100,000by 2016.8,9 Conversely,thenumberofEDvisitsforpsychiatric complaintshasrisenby50%.8 Thishasledtoasituation wheremanypatientswhorequireinpatientmentalhealth caremustwaitintheEDuntilapsychiatricbedbecomes available.Thisdelayintransferringpatientstoaninpatient unitleadsto “psychiatricEDboarding.”12

Thestate-of-the-artinterventionsavailabletoemergency physiciansareorientedtowardsafelydischargingpatients homeandconnectingthemtodefinitivementalhealth services.13,14 Briefinterventionsorreferralfollowedby dischargehomearecommonforpatientspresentingwith non-life-threateningsuicidalthoughtsandbehaviors, whereaspatientspresentingwithmoderatetosevererisk behaviorsforsuicideareusuallykeptintheEDuntiltransfer toaninpatientpsychiatricfacilityispossible.15 Thissplitting ofpatientsintocategoriesofriskseverity16 meansthatthe higherapatient’sriskforsuicide,thefewerinterventionsare availabletoaddressthepatient’sparticularneeds.Notably, nopharmacologicagenthasbeenapprovedbytheUS FoodandDrugAdministrationtotreatsuicidalityinthe ED;mostmedicationsadministeredtosuicidalED patientstypicallytargetonlyagitation,notthesuicidal symptomsthemselves.16,17

Fromapsychiatricperspective,mostavailable interventionstargetsuicidalthoughtsandbehaviorsoverthe longtermasopposedtotheshort-ormediumterm17 andare thereforeill-suitedtotheacutecareenvironment. Psychopharmacologicagentssuchasantidepressants, lithium,andantipsychoticsgenerallyrequireacourseof weeksormonthstotakeeffect,14 andbeginningacourseof

antidepressanttreatmentcanparadoxicallyincrease suicidalityinsomepopulations.18 Similartimescalesare requiredforempiricallysupportedpsychotherapiessuchas cognitivebehavioraltherapyandothers,17,19 andeventhe mostabbreviatedstandardinterventionscantakeupto sixweeks.20

Whiletheimportanceofscreeningforsuicidalityiswell understood,21 thereisgrowingneedforevidence-based, rapidlyacting,effectivetreatmentoptions.15 Manyexisting toolssuitedtotheEDenvironmentthattargetsuicidality lacksupportingevidenceor,worse,are counterproductive.22,23 Onesuchinterventionisthesafety contractorno-suicideagreement.Whileatonetimethegold standardforEDanti-suicidalinterventions,thesafety contracthasbeenshowntoproduceworseoutcomesthanno interventionatall.21,24 Totheextentthatmorerecent interventionsfortheeffectivetreatmentofacutesuicidality haveemerged,therehasbeennoreviewcreatedspecificallyto identifyanddescribepotentialinterventions.

AnanalysisbyInagakiandcolleagues25 identifiedbroad classesofinterventionstopreventrepeatsuicideattemptsin patientsadmittedtoanEDbutdidnotinvestigatewhich interventionswouldbebestsuitedtotheEDenvironment. Changandcolleaguesprovidedareviewofmajordepressive disorderandsuicidalityintheEDbutdidnotofferan analysisofrecentlydescribedinterventions.21 Ina2021 review,Mannandcolleagues26 surveyedthelandscapefor evidence-basedtherapiesforsuicidalityingeneral,butthey didnotfocusspecificallyontheED.Whileotherrecent reviewshaveassessedtheavailabilityofclinician-oriented educationalinterventions,23 orinterventionsformental decompensationingeneral,27 nonehavethoroughlyassessed theliteratureforrecentlydescribedtoolsthatcliniciansmay usetotreatacutesuicidalityinthecontextoftheED. Lengvenyteandcolleagues28 publishedasystematicreview ontheimmediateandshort-termefficacyofsuicide-targeting interventionsbutdidnotfocusonrecentinterventionsused intheED.Weundertookthisreviewto fillthegapand exploretheliteraturetoidentifyanddescriberecent,patientcenteredinterventionsfortheeffectivetreatmentofacute suicidalityintheED.

Inthisreviewwefocusedonrecentlydescribed interventionsthatcanbeadministeredinthecontextofa patient’sstayintheED,namely,brieftherapiesand pharmacologicagentsthat fitwiththestandardmedical modeloftreatment.State-of-the-artpractice(ie,generally acceptedcare),definedasinterventionsforacutesuicidality, aredescribedin Rosen ’ sEmergencyMedicine:Concepts andClinicalPractice 29 or KaplanandSadock ’ s ComprehensiveTextbookofPsychiatry . 30 Theseinclude screening,jointsafetyplanning,patienteducation,lethal meanscounseling,follow-upcontacts,andtheinvolvement offriendsandfamily.29,30 Interventionslistedinor moderatelymodifiedfromthosedescribedinthesetextbooks

wereconsideredstate-of-the-artandexcludedfromthe search.Theprimaryquestionofthisreviewwasasfollows: Whatrecentlydescribedinterventionsareavailableforusein reducingsuicidalityandstabilizingpatientsduringa psychiatriccrisisintheED?

METHODS WesearchedPubMed,SCOPUS,andCINAHLon January15,2024.Thisreviewwasconductedinaccordance withbest-practicerecommendationsofthePreferred ReportingItemsforSystematicReviewsandMeta-Analysis (PRISMA)extensionforscopingreviews.31 Inclusioncriteria includedthefollowing:1)studyparticipantpatientswere presentingtotheEDwithsuicidalideation;2)thestudy assessedtheefficacyofoneormorepatient-centered intervention(s)aimedatreducingsuicidalthoughtsand behaviors;3)theinterventionbeingtestedwasadministered topatientsintheED;4)theinterventionwasadministeredby emergencyphysiciansorpersonnel;5)thestudywas availableinEnglish;and6)thestudyhadbeenpublishedin thelast10years.

DefinitionofSuicidalityandRecentInterventions Weadoptedthesuicidalitynomenclatureproposedby Silvermanandcolleagues.32 Studiesimplementingthebroad termsuicide-relatedthoughtsandbehaviors(SRTB),orany sub-categorythereof,wereconsideredeligibleforinclusion. Foraresourceonresearch-validatedscalesforthe measurementofsuicidalitywereliedonthelistcompiledby Ghasemi,Shaghaghi,andAllahverdipour.33 Wesoughtto identifyrecentlydescribed,effectivetreatmentsforthe preventionofsuicidalbehaviorthatareoutsidethestate-ofthe-art(currentstandards).Tothisend,wedefinedrecent interventionsasbeingpatient-centered,deliveredintheED, describedwithinthepast10years,andnotalreadypartof recognizedstate-of-the-artpractice.

FeaturesofEligibleStudies Weassessedstudiesforcharacteristicfeaturesoncethey wereincludedintheanalysis,andweevaluatedthe comparativestrengthsandweaknessesofstudydesign, samplesize,etc.Studiesconsideredidentifiedaspecific, recentinterventionforacutesuicidalityincontextoftheED intheprevious10years,sinceearlierinterventions wereconsideredmorelikelytobeconsistentwith state-of-the-artpractice.

Searchstrategy Weusedathree-stepsearchstrategyinconsultationwitha libraryscientist.Inthe firstphase,weconducteda preliminarysearchofPubMedtoensurerelevantresultswere retrievedfromoursearchterms.Inthesecondphase,the searchtermswereappliedtoPubMed,SCOPUS,and CINAHL.See AppendixA forthesearchtermsused.Inthe

thirdphase,wescannedtheresultsfromthesearchconducted inphasetwoforreferencesincludedinstudybibliographies thatcouldhaveprovidedadditionalarticles.Thedatabase searchstrategyissummarizedin AppendixA.Weconducted additionalsearchesofGoogletoidentifygrayliterature orpublicationsnotdiscoveredviatheabove-described searchprocess.

Studyselection Oncesearchtermsandkeywordswerenarroweddown,we removedduplicatesfromthelistofarticles.Four independentreviewersscreenedthetitlesandabstractsfor relevanceofallremainingstudies.Articlesdeterminedtobe relevantatthisstagewereretrievedinfull-textformand screenedforrelevancebytwoindependentreviewers.Apreselectedarbitersettledinconsistenciesbetweenreviewers.We recordedanddocumentedreasonsforexclusionforany article.Avisualizationofthisprocessisincludedina PRISMA flowdiagram34 in Figure1,whichalsoprovidesaa summaryofresultsinstandardPRISMAformat.

Dataextraction Data fieldscollectedfromincludedstudiesare summarizedinthedataextractiontoolgivenin AppendixB. TheprimaryauthorA.P.H.extracteddatausingthetool, andthedatawascheckedforaccuracyandcompletenessby anindependentreviewer.

RESULTS Afterduplicateswereremoved,weanalyzed1,197studies. Thereareafewreasonsforthislargenumberofresults.In keepingwithbest-practiceguidelines,andtoavoidthe

iden fied through database search (N = 1213)

iden fied in gray literature (n = 0)

a er duplicates removed (n = 1197)

iden fied via References sec ons (n = 0)

Titles/abstractsscreened (n = 1197) Records excluded (n = 1181)

Full-text ar cles assessed for eligibility (n = 16) Full-text ar cles excluded, with reasons (n = 7)

Studies included (n = 9)

Figure. PRISMA flowdiagramofstudyselection.

improperexclusionofanyrelevantarticles,weusedbroad searchtermstoreturnthemaximumnumberofpotentially relevantarticles.Additionally,noMeSHtermsspecifically aimedatexcludingscreeningandriskassessmentwereused. Thetitle/abstractreviewphasewas,therefore,acriticalstage fortheisolationofrelevantarticles,andweremoved1,181 fromfurtheranalysis.

Inthenextphaseofeligibilityscreening,twoindependent reviewersretrievedandevaluatedthefulltextsof16articles, ofwhichsevenwereexcluded.Disagreementsweresettledby anemergencyphysicianwithrelevantexpertiseinacutecare interventionsforsuicidalityR.A.D.Oftheexcludedarticles, twostudiesinvolvedinterventionsthatweretailoredtothe uniqueculturalpracticesofspecificindigenousgroupsand werethereforedeemednotgeneralizabletoallsuicidal patientspresentingtoEDs.35,36 Twoadditionalarticleswere excludedastheyusedasafetyplanningintervention operationallydefinedaspartofstate-of-the-artpractice.One articlewasexcludedbecausethestudyinterventiondidnot occurintheEDsetting.37 Finally,weexcludedtwo secondaryanalysesofarticlesthathadalreadybeen included.38,39 Oftheninearticlesincludedintheanalysis,we extracteddatausingthetoolgivenin AppendixA.Anoverviewofrelevantdatafromeachstudy ispresentedinthe Table

Fourincludedarticlesassessedtheuseofasingledoseof thepharmacologicinterventionketamine,aN-methyl-Daspartateantagonistcommonlyusedasasedative,analgesic, andanesthetic.40–43 Threestudiesassessedtheuseofan intravenous(IV)infusion,40,42,43 andoneassessedthe efficacyandtolerabilityofanintranasaladministration.41 Twooftheselectedarticlesassessedtheefficacyof interventionscenteredonmotivationalinterviewing(MI) embeddedinaninterventionalframeworkwithprovisions forfollow-upcareorreferralassistance.44,45 BothTeen OptionsforChange(TOC)45 andSuicidalTeensAccessing TreatmentAfteranEmergencyDepartmentVisit(STATED)44 targetedadolescentsamples.

Thethreeremainingincludedarticlesstudiedvarious interventionscenteredonacutepsychotherapyand/or behavioralmanagementinthepost-acuteperiod.Byfarthe largestsampleamongincludedarticleswasastudyof assertivecasemanagementforthosepresentingtotheED afterasuicideattempt.46 Whilethelengthy(18+ months) interventionunderstudyinthisarticlelargelytookplace followingdischargefromtheED,theintervention proceduresbeganwhilepatientswereintheEDandwere deliveredbypsychiatristsorothermedicalpersonnel.46

Anotherstudythatmetourcriteriainvestigatedtheefficacy ofthenovel,manualizedProblemSolvingand ComprehensiveContactIntervention(PS-CCI),whichusesa collaborativelycompletedworksheetaimedatenhancing self-efficacyandcognitive flexibilityinsuicidalEDpatients pairedwithfollow-upcare.47 Finally,astudyoftheCrisis

ResponsePlan(CRP)interventionconductedbyBryanand colleaguesinamilitaryEDmetinclusioncriteria.22 TheCRP pairsabriefhistoricalinterviewwithacollaborative identificationanddocumentationofcopingstrategiesand resourcesavailabletopatients.22

StudyFeaturesandCharacteristics Severalmeasuresofstudyfeaturesandcharacteristics weregatheredintheprocessofdataextraction.Weused PRISMAguidelinestohelpdefineelementsofquality31 includingsamplesize,studydesign,follow-uptimeframe, andmeasuresused.

Sample Thesamplesizesofthemajorityofstudiesmeeting inclusioncriteriaweresmall.Excludingtheoutlierof Kawanishietal46 withtheirrobustsampleof914,theaverage samplesizeforincludedstudieswas57,withthesmallest sample(10)collectedbyBurgerandcolleagues.40

Design Sevenofninestudiesconductedarandomizedcontrolled trial(RCT),onewasaquasi-experimentaltwo-arm prospectivelongitudinalstudy,47 andonewasanonexperimentalpilotstudydesignedtoevaluatethefeasibility andefficacyofasinglelowdoseofketaminedeliveredviaIV bolus.43 Double-blindingandrandomassignmentwere consistentlypracticedamongtheRCTsassessingtheefficacy ofketamine,andparticipantsinthecontrolconditions receivedaninactiveplaceboinjection/atomizationofnormal saline.40–42 Kawanishiandcolleagues,46 Kingetal,45 and Grupp-Phelanetal44 usedsingleblindingandacomparator conditionofenhancedusualcare(EUC).Intheirthree-arm RCT,Bryanandcolleagues22 comparedtwoversionsofCRP (standardandenhanced)tothecontrolconditionofa contractforsafety,andparticipantswereblindedtogroup assignment.Althoughthecontractforsafetywaspreviously astandardintervention,ithasmanynoteworthy shortcomings22 makingitaless-than-idealcomparison conditiontoCRP.24

Follow-upmeasuresandtimeframe Sevenoftheninestudiesincludedinthisreviewused standard,well-subscribed,psychometricallyvalidated measuresofsuicidalitytoassessoutcomevariablesof interest,aswellasevaluationsofrepeatedhospitalizations andhealthcareutilization.Themostcommonscalesused weretheColumbiaSuicideSeverityRatingScale,theBeck ScaleforSuicidalIdeation,andtheMontgomery-Asberg DepressionRatingScale.However,twostudiesevaluated onlypost-dischargesuicideattempts,suicidedeaths,and psychiatrichospitalizationrecidivismwithoutmakinguseof psychometricmeasures.46,47 Thefollow-uptimeframes

Table. Summaryofindividualstudies.

PS-CCIisfeasibleas aninterventionfor suicideintheED

3mosDidnothavethe sampleforstatistical signi fi cance,butthey appearedto fi ndthat thisinterventionwas feasibleasmeasured byacceptability, engagement, fi delity, subjectretention,and lackofAEs.

Structured worksheet manualized

AuthorsYearCountryObjective(s)InterventionMethodsN

Intervention somewhateffective shorttermandamong women,butoverall assertivecase managementdidnot outperformcontrol condition

Lowerrecurrent suicidalbehaviorat1, 3,and6mos;butat 18mostherewasno signi fi cantdifference inratesofattempted orcompletedsuicides

BriefMIwasnot usefulinthiscontext

443mos “ Clinician ” not otherwise de fi ned

Longitudinal design

2014USATodeterminethe feasibilityand acceptabilityofa novel,manualized problem-solvingand comprehensive contactintervention (PS –CCI)aimedat improvingtreatment engagementof suicidalindividuals. Manualized problem-solving and comprehensive contact intervention

Dana Alonzo

91418mos to 5years Psychiatrist, nurses,clinical psychologists, etc Case management manual, phone 18 mos-5 yrs

Two-armed RCT

Assertivecase management

2014JapanTodetermineif assertivecase managementcan reducerepeated suicideattemptsin peoplewithmental healthproblemswho hadattempted suicideandwere admittedtoEDs

Kawashini etal

None6mosMIwasnotbetter thanenhancedusual care

1592mos total Licensed socialworker

Two-armed RCT

2019USAToexaminewhether motivational interviewing(MI) increaseslinkageof adolescentsto outpatientmental healthservicesfor depressionand suiciderisk MIpluslinking tofollowup services

Grupp- Phelan etal

CRPishighly effectiveforuseinthe acutecaresettingfor acutelysuicidal patients

Indexcard6mosStandardCRPand reasonsforliving CRPwerebothmore effectivethana contractforsafetyin reducingsuicide attemptsandinpatient hospitalization.No differencebetween twoversionsofCRP

971hrCliniciannot de fi ned

CRPThree-armed RCT

Bryanetal2017USAToevaluatethe effectivenessofcrisis responseplanning (CRP)forthe preventionofsuicide attempts

IVketamineappears tobefeasibleand effectiveintheshort term (

Signi fi cantdifferences insuicidalityscores 90 –180minsafterIV ketamineinfusion. Safetyandtolerability wereexcellent.

Two weeks

IVbag,drug, 10mlsyringe, vitalsign monitoring equipment

185minsBoard-certi fi ed

EDphysician

KetamineIVPlacebo- controlled doubleblind RCT

2020USAToassessthesafety, feasibility,tolerability, andef fi cacyofa singlelow-dose intravenous(IV) ketamineinreducing suicidalideation

Domany and McCullums Smith

Table. Continued.

Ketamineshows promiseasanacute caretreatment modality,butfurther researchisneededto validatetheeffectsof thisverysmalltrial.

Groupsvaried signi fi cantlyinthe short-termduring hospitalization; however, discrepanciesin scoresontherating scalesdiminishedat thetwo-weekfollow- uppoint.

Two weeks

AuthorsYearCountryObjective(s)InterventionMethodsN

Thisintervention appearstobe promisingbutwill needtobetestedina largersample

2mosLargeeffectforthe lowingofdepression scores,moderate effectfor hopelessness,and insigni fi canteffects forsuicidalideation andalcoholuse (thoughthestudy wasn ’ tquitelarge enoughtostatistically verifythelatter fi ndings

Theauthorsnotethat ketaminedidnot showitselfasa promisingtoolto mitigateacute suicidalityintheED context,asthe reductionsin suicidalityscores werenotclinically meaningful.However, theydonotethat moreresearchis neededandthatthis resultisfarfrom de fi nitive(giventhe samplesizeandlack ofcontrolgroup).

Theketamineinfusion wasassociatedwitha bringingdownthe MADRSandSSI scoresbya statisticallysigni fi cant margin,butthe authorsnotethat,for theirpurposes,the reductioninscores wasnotclinically meaningful(e.g., belowthethreshold setforthepurposes ofthestudyofa MADRSscoreof ≤ 4). Thelargestreduction inself-reported suicidalityoccurred within40minsof ketamine administration.

( Continuedonnextpage )

105minsTrainednurseIVbag,vital sign monitoring equipment

KetamineIVDouble-blind RCT

Burgeretal2016USATocompareIV ketaminetoplacebo amongacutely suicidalpatientsina militarysetting

Handwritten followup note

Trained mentalhealth professional withminimum of40hrsof specialized training

4945mins ofMI,5 daysof follow up

RCTwith enhanced TAUas control condition

TeenOptions forChange (TOC)

Kingetal2015USAThisrandomizedtrial examinedthe effectivenessofTeen OptionsforChange (TOC),an interventionfor adolescentsseeking medicalemergency serviceswhoscreen positiveforsuicide

IVbag,vital sign- monitoring equipment 10 days

495minsNurseor attending doctor

Uncontrolled pre-test/post- test

KetamineIV bolus

2014IranThisstudywas conductedto examinetheeffects ofasingle intravenousbolusof ketamineonpatients withsuicidalideation intheED.

Kashani etal

Table. Continued.

Whilethesampleis comparativelysmall andtheoverallresults arefarfrom conclusive,thisstudy importantlyechoes previous fi ndings demonstratingthata lowdoseofketamine doesappearto transientlyreduce suicidalideationin thoseathighacute riskforsuicide.In addition,itprovides promisingevidence thatasingle, fi xed doseofketaminemay havethepotentialto reducehospital lengthsofstay,and thatintranasalisa feasiblerouteof administrationforthe acutecaresetting.

Participantswhowere administered ketaminehadnotonly amuchhigherrateof remission(roughly 80%ofthesample), butalsotypically shorterlengthsof hospitalization. Ketaminewas generallysafe;minor sideeffectswere transientandresolved within1 –2hourspost- administration. However,thelinear mixedstatistical modeldidnotshow signi fi canceon randomgroupbytime interaction.

4 weeks

PsychiatristIntranasal atomizer

AuthorsYearCountryObjective(s)InterventionMethodsN

3040mins to1hr

Double-blind RCT

Ketamine intranasal

2022USAEvaluationofsingle, fi xed-dosed intranasalketamine foracutesuicidal ideationintheED

AEs ,adverseevents; ED ,emergencydepartment; IV ,intravenous; MADRS ,MontgomeryAsbergdepressionratingscale; RCT ,randomized,controlledtrial; SSI ,BeckScalefor SuicidalIdeation; TAU ,treatmentasusual.

Domany and McCullum Smith

variedsignificantlydependingontheinterventionunder studyandaddedtotheheterogeneityofthesample.

FitofInterventiontoEmergencyDepartmentEnvironment Sinceweintendedtoanalyzerecentlydescribedtools availabletoemergencyphysiciansforuseintheacutecare setting,attentionwaspaidtotheusabilityofeach interventionintheEDsetting.Wedefinedusabilityaseaseof useand fittotheEDenvironment,andthesewereevaluated alongthedimensionsoftotaltimerequiredtoadminister,the requiredtrainingorcredentialsoftheadministering practitioner,andthetoolsandmaterialsrequiredtodeliver theintervention.

Timetoadminister Byfarthebriefestinterventionalmodalityamongthe articlesreviewedwasasingledoseofketaminedeliveredIV, which,atthemodestdosesused,averaged5–10 minutes.40,42,43 Whenadministeredintranasally,theinterval requiredtocompletetheintervention,althoughbrief(40–60 minutes),wassomewhatlonger.41 Notincludedinthe interventiondurationwasthemonitoringtimerequiredfor ketamineadministration,whichdependingonlocalprotocol canexceedseveralhours.EquivalentlybriefisCRP,which requires30–60minutestoadminister,makingitwell-suited tothedemandsofthefast-pacedEDenvironment.22 The studiesassessingMI-basedinterventionsforadolescentshad briefED-deliveredcomponents,requiringapproximately45 minutestodeliver.44,45 Thetimerequiredtoadministerthe ED-basedproblem-solvingcomponentoftheProblemSolvingandComprehensiveContactIntervention(PS-CCI) interventionwasnotspecified.47 Finally,Kawanishiand colleaguesdidnotspecifythetimecourseoftheED-based portionofassertivecasemanagement,buttheydidnotethe interventioninvolvedregularfollow-upappointments outsidetheEDoverthecourseof18months.46

Trainingrequiredtoadminister

Dueinparttovariabilityinhospitalpracticesindifferent regionsandcountries,thecredentialsofthehealthcare professionalsadministeringketaminevariedslightlyacross thefourstudiesthatinvestigateditsuse.40–43 Intravenous administrationwasconductedbyeitheranurseora physician,40,42,43 whereasthestudyusingintranasal ketaminerequiredsignificantinputfromapharmacist.41 BoththePS-CCI47 andCRP22 statedonlythatthe interventionwasdeliveredbya “clinician,” nototherwise specified.TheSTAT-EDdescribedbyGrupp-Phelanetal44 andTOCstudiedbyKingetal45 wereadministeredbya socialworkerandtrainedmentalhealthprofessional, respectively,withthelatterspecifyingthatinterventionalists wererequiredtohaveaminimumof40hoursof specializedtraining.Finally,theassertivecasemanagement interventiondescribedbyKawanishiandcolleagues46 was

conductedbycasemanagersatvariouslevelsoftraining, includingnurses,emergencyphysicians,psychiatrists,and clinicalpsychologists.

Toolsandmaterials Formostpsychosocialinterventionsunderstudyinthe presentreview,fewspecializedmaterialswererequiredfor administration.Specifically,theSTAT-EDintervention,44 CRP,22 andTOC45 requirebasicofficeequipmentsuchas copypaperandnotecards.ThePS-CCIinterventionrequires theavailabilityofastructuredworksheet,47 andtheassertive casemanagementinterventionrequiresastandardized manual,46 makingtheirresourcedemandsminimal.Aswith allnovelpharmacologicinterventions,thestudiesassessinga singledoseofketaminerequiredtheavailabilityof equipmenttomonitorvitalsigns.40–43 ThoseassessingIV ketaminerequiredIVbags,pumps,lines,andhanging apparatuses,whichareusuallyavailableinED environments,40,42,43 whilethestudyofintranasal ketaminerequiredaspecializedatomizerpreparedbya pharmacyteam.41

EfficacyFindings Theinterpretationof findingsforarticlesdescribedinthe presentreviewshouldbemoderatedbylimitationsregarding samplesize,methodologicaldiscrepancies,andevidentiary quality.Twopromisinginterventionsweidentifiedarethe variousadministrationroutesofasingle,lowdoseof ketamine,40–43 andasinglemeetingtodevelopaCRP.22 For asingledoseofketamine,threearticlesreportedpositive findingsontheshort-termreductionofself-reported suicidalityanddepression,40–42 andonereported inconclusiveresults.43 Bryanandcolleagues22 foundthat participantsrandomizedtoeitherCRPcondition(standard orenhanced)showedsignificantreductionsinacutesuicidal ideation,fewersuicideattempts,andlowerratesofinpatient hospitalizationpost-dischargethanthoseinthe comparatorgroup.

Twootherinterventionsthatwereevaluated,PS-CCIand MI,showpromise,butthereisinsufficientevidenceto supporttheirefficacy.ThePS-CCItrial47 wasnotstatistically poweredtodetermineefficacy,buttheauthorsnotethatthe interventionisfeasibletoadministerintheEDsettinggiven itshightolerability.TheTOCstudy45 andtheSTAT-ED study44 trialedsimilarMI-basedtreatmentsincomparable adolescentsamplesbutreturnedconflictingresults.The studyofassertivecasemanagementbyKawanishiand colleagues46 hadalargesamplesizebutdemonstratedno significantdifferencebetweengroupsoverthecourseof thestudy.

DISCUSSION Thepreliminaryresultsfromthefourketaminestudies includedinthisreviewecho findingsoftheuseofketamine

forsuicidalideationinoutpatientsettings.48 Therearea numberofadvantagestothisinterventionalmodality.43 First,ketamine,whenadministeredIVover5–10minutes,is byfarthebriefestinterventionnotconsideringthepostinfusionmonitoringtime.Intravenousketamineiswell suitedtothefast-pacedenvironmentoftheED.The intranasaladministrationrouteisalmostasbrief.

Intramuscular(IM)ketamineisanotheroptionbutrelatively unstudied;however,itmaybefamiliartoemergency clinicians.IfconfirmedinfullypoweredRCTs,sucharapidactinginterventionmaygiveemergencyphysicians additionaloptionsfortheplacementorevendischargeof patientswhopresentwithacutelyelevatedsuicideriskand couldserveasabridgetodefinitivementalhealthcarethat circumventstheneedforalengthydetentionintheED. Furthermore,adoseofgenericketamineisrelatively inexpensive49 andregularlystockedinmostEDs.The intranasalformofketamine,esketamine,incontrast,is moreexpensiveandlesswidelystocked.Additional researchontheefficacyofketamineforacutelysuicidalED patientsiswarranted.

ThisreviewfoundevidencethatCRPshowspromiseasan interventionwellsuitedtocombatacutesuicidalityintheED environment.Whilethereislimitedevidenceinsupportofthe efficacyofCRPintheED,thisinterventionhasseveral featuresthatmakeitwellsuitedtothespecificdemandson emergencymedicalpersonnel.First,similartoasingledose ofketamine,CRPisaninterventionalmodalitythatisbrief inadministrationandappearstorapidlydiminishacute suicidalityandimprovepatientmood.38 Additionally,CRP ismaximallyportabletoavarietyofenvironments,requires comparativelylittlespecializedtraining,toolsormaterialsto administer,and,asapsychosocialintervention,isnot contraindicatedforusewithanyconcomitantmedications. Despiteitsadvantages,theliteraturetodateontheuseof CRPintheEDcontextislimitedtoonestudy.22 Whilethe evidenceforinterventionssuchasthePS-CCI47 andTOC45 is mixed,ED-deliveredinterventionstargetingconstructsof cognitive flexibilityandadaptiveproblem-solvingappearto bearecipewithsomepromise(similartoCRP).

FutureDirections LIMITATIONS Althoughthepresentstudyhasmanynotablestrengths, someshortcomingsshouldbedelineated.First,wefocused oninterventionswithevidencesupportingtheabilitytobe performedinthechallengingEDenvironment.Itispossible thatrecentinterventionsunderstudyinotherclinical environmentsmayholdpromiseforadaptationtotheED setting.Second,asisthecasewithanyreview,itispossible thatcertaininterventionsextantintheliteraturewere erroneouslyexcludedfromouranalysisgiventhelimitations ofourMeSHsearchterms.Finally,tolimitouranalysisto onlythemostrecentinterventionswithanevidentiarybasis inthecurrentliterature,weassessedonlyarticlespublishedin theprevious10years.Itispossiblethattherearepromising, ED-basedinterventionsdescribedmorethan10yearsago thathavereceivednofurtherstudyintheinterveningtimeor havebeenstudiedexclusivelyoutsidetheEDcontextsince theirinitialdescription.

CONCLUSION Therecentlydescribedinterventionsidentifiedfor emergencyphysicianstotreatacutesuicidalityarelimitedto onedrug(ketamine)andfouruniquepsychological/ behavioralinterventions.Twoofthe fiveinterventional modalitieshavepreliminaryevidenceandmayholdpromise inmitigatingacutesuicideriskintheED:asingle,lowdose ofketamineandcrisisresponseplanning.However,thereis insufficientevidencetosupporttheirwidespreadadoption. Futureresearchshouldextendthepreliminary findings summarizedinthisreview.

AddressforCorrespondence:AlexP.Hood,BA,UniversityofTexas HealthScienceCenteratSanAntonio,DepartmentofEmergency Medicine,703FloydCurlDrive,MC7736,SanAntonio,TX78229. Email: alex_hood1@baylor.edu

ConflictsofInterest:Bythe WestJEMarticlesubmissionagreement, allauthorsarerequiredtodiscloseallaffiliations,fundingsources and financialormanagementrelationshipsthatcouldbeperceived aspotentialsourcesofbias.Noauthorhasprofessionalor financial

Thisstudyidentifiedtwopromisinginterventionssuitedto theEDenvironment:CRPandketamine.Theevidentiary basisfortheseinterventions,particularlyinbroad-based populationsofemergentlysuicidalEDpatients,isnotfully developed.Furtherstudyisrequiredtoascertaintheextentto whichtheseinterventionsserveaseffectivetreatmentsacross presentingpsychiatricsymptoms,especiallygiventhehigh incidenceofSRTBamongpatientswithseriousmental illnessoracuteintoxicationwithasubstance,whichmay complicateeffectivetreatment.50 Giventhecrisisofboarding inEDs,additionalfundingandstudyingeneralshouldbea nationalpriority.Futurestudiesshouldalsoinvestigate ketaminedeliveredviaalternativeroutesofadministration suchasorallyandIM.WhileCRPhasdemonstrated preliminaryefficacy, 24 futureresearchshouldcompareCRP tovalidatedcurrentstandardpracticeinterventionsto properlyevaluateitseffectivenessagainsttreatmentasusual orEUC.Futurestudiesshouldalsovalidateuseofthe interventionoutsidethemilitarycontextwithparticipantsof variousbackgrounds,abilitylevels,andages.Giventhat briefMI-andCBT-basedinterventionsshowpromise,future studiesmayconsidercontinuingtohoneinterventionsthat approximatelyadheretothismodel.

relationshipswithanycompaniesthatarerelevanttothisstudy. Therearenoconflictsofinterestorsourcesoffundingtodeclare.

Copyright:©2024Hoodetal.Thisisanopenaccessarticle distributedinaccordancewiththetermsoftheCreativeCommons Attribution(CCBY4.0)License.See: http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/

REFERENCES 1.StoneDM,SimonTR,FowlerKA,etal.Vitalsigns:trendsinstate suiciderates-UnitedStates,1999–2016andcircumstances contributingtosuicide-27states,2015. MorbMortalWklyRep. 2018;67(22):617–24.

2.AhmedaniBK,SimonGE,StewartC,etal.Healthcarecontactsinthe yearbeforesuicidedeath. JGenInternMed. 2014;29(6):870–7.

3.GairinI,HouseA,OwensD.Attendanceattheaccidentandemergency departmentintheyearbeforesuicide:retrospectivestudy. BrJPsychiatry. 2003;183:28–33.

4.CrandallC,Fullerton-GleasonL,AgueroR,etal.Subsequentsuicide mortalityamongemergencydepartmentpatientsseenforsuicidal behavior. AcadEmergMed. 2006;13(4):435–42.

5.WeissAJ,BarrettML,HeslinKC,etal.(2006).Trendsinemergency departmentvisitsinvolvingmentalandsubstanceusedisorders, 2006–2013.In HealthcareCostandUtilizationProjectstatisticalbriefs Rockville,MD:AgencyforHealthcareResearchandQuality(US). Availableat: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK52651/ AccessedAugust6,2024.

6.HakenewerthAM.Emergencydepartmentvisitsbypatientswithmental healthdisorders–NorthCarolina,2008–2010. MorbMortalWklyRep. 2013;62(23):469–72.

7.OwensC,HansfordL,SharkeyS,etal.Needsandfearsofyoung peoplepresentingataccidentandemergencydepartmentfollowingan actofself-harm:secondaryanalysisofqualitativedata. BrJPsychiatry. 2016;208(3):286–91.

8.TreatmentAdvocacyCenter.Going,going,gone:trendsand consequencesofeliminatingstatepsychiatricbeds.2016.Availableat: https://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/reports_publications/ going-going-gone-trends-and-consequences-of-eliminatingstate-psychiatric-beds/.AccessedSeptember4,2023.

9.GoldJ.Adearthofhospitalbedsforpatientsinpsychiatriccrisis.2016. Availableat: https://kffhealthnews.org/news/a-dearth-of-hospitalbeds-for-patients-in-psychiatric-crisis/.AccessedAugust6,2024.

10.ZunL.Careofpsychiatricpatients:thechallengetoemergency physicians. WestJEmergMed. 2016;17(2):173–6.

11.FitzpatrickSJandRiverJ.Beyondthemedicalmodel:futuredirections forsuicideinterventionservices. IntJHealthServ. 2018;48(1):189–203.

12.NicksBAandMantheyDM.Theimpactofpsychiatricpatientboardingin emergencydepartments. EmergMedInt. 2012;2012:360308.

13.RihmerZPandMaurizioP.Mooddisorders:suicidalbehavior.In: SadockBJ(Ed.), KaplanandSadock’sComprehensiveTextbookof Psychiatry (3825),10thed.Philadelphia,PA:WoltersKluwer Health,2017:3825–51.

14.WassermanD.Suicide:overviewandepidemiology.In:SadockBJ(Ed.), KaplanandSadock’sComprehensiveTextbookofPsychiatry (5954). 10thed.Philadelphia,PA:WoltersKluwerHealth,2017:5954–72.

15.CapocciaLM.Caringforadultpatientswithsuiciderisk:aconsensusbasedguideforemergencydepartments.2015.Availableat: https://sprc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/EDGuide_full.pdf AccessedAugust6,2024.

16.BetzJ.M.Suicide.In: Rosen’sEmergencyMedicine:Conceptsand ClinicalPractice (pagerange).9thed.Philidelphia,PA:Elsevier, Inc,2018:1366–73.

17.SudakH. Suicidetreatment.In:SadockB.J.(Ed.), KaplanandSadock’s ComprehensiveTextbookofPsychiatry (5973).10thed.Philadelphia, PA:WoltersKluwer,2017:5973–85.

18.ReevesRRandLadnerME.Antidepressant-inducedsuicidality: anupdate. CNSNeurosciTher. 2010;16(4):227–34.

19.RuddMD,BryanCJ,WertenbergerEG,etal.Briefcognitive-behavioral therapyeffectsonpost-treatmentsuicideattemptsinamilitary sample:resultsofarandomizedclinicaltrialwith2-yearfollow-up. AmJPsychiatry. 2015;172(5):441–9.

20.DavidsonKM,BrownTM,JamesV,etal.Manual-assistedcognitive therapyforself-harminpersonalitydisorderandsubstancemisuse: afeasibilitytrial. PsychiatrBull(2014). 2014;38(3):108–11.

21.ChangBP,TezanosK,GratchI,etal.Depressedandsuicidalpatientsin theemergencydepartment:anevidence-basedapproach. EmergMed Pract. 2019;21(5):1–24.

22.BryanCJ,MintzJ,ClemansTA,etal.Effectofcrisisresponseplanning vs.contractsforsafetyonsuicideriskinU.S.Armysoldiers: arandomizedclinicaltrial. JAffectDisord. 2017;212:64–72.

23.ShinHD,CassidyC,WeeksLE,etal.Interventionstochangeclinicians’ behaviorinrelationtosuicidepreventioncareintheemergencydepartment: ascopingreviewprotocol. JBIEvidSynth. 2021;19(8):2014–23.

24.RuddMD,MandrusiakM,JoinerTE.Thecaseagainstno-suicide contracts:thecommitmenttotreatmentstatementasapractice alternative. JClinPsychol. 2006;62(2):243–51.

25.InagakiM,KawashimaY,KawanishiC,etal.Interventionstoprevent repeatsuicidalbehaviorinpatientsadmittedtoanemergency departmentforasuicideattempt:ameta-analysis. JAffectDisord. 2015;175:66–78.

26.MannJJ,MichelCA,AuerbachRP.Improvingsuicideprevention throughevidence-basedstrategies:asystematicreview. AmJPsychiatry. 2021;178(7):611–24.

27.JohnstonAN,SpencerM,WallisM,etal.Reviewarticle:Interventions forpeoplepresentingtoemergencydepartmentswithamental healthproblem:asystematicscopingreview. EmergMedAustralas. 2019;31(5):715–29.

28.LengvenyteA,OliéE,StrumilaR,etal.Immediateandshort-term efficacyofsuicide-targetedinterventionsinsuicidalindividuals:a systematicreview. WorldJBiolPsychiatry. 2021;22(9):670–85.

29.MarxJA,HockbergerRS,WallsRM,etal.In: Rosen’sEmergency Medicine:ConceptsandClinicalPractice.9thed.Philadelphia,PA: Mosby/Elsevier,2018.

30.SadockBJS,AlcottV,RuizP. KaplanandSadock’sComprehensive TextbookofPsychiatry.10thed.Philadephia,PA:WoltersKluwer,2017.

31.TriccoAC,LillieE,ZarinW,etal.PRISMAextensionforscoping reviews(PRISMA-ScR):checklistandexplanation. AnnInternMed. 2018;169(7):467–73.

32.SilvermanMM,BermanAL,SanddalND,etal.RebuildingtheTowerof Babel:arevisednomenclatureforthestudyofsuicideandsuicidal behaviors.Part2:suicide-relatedideations,communications,and behaviors. SuicideLifeThreatBehav. 2007;37(3):264–77.

33.GhasemiP,ShaghaghiA,AllahverdipourH.Measurementscalesof suicidalideationandattitudes:asystematicreviewarticle. HealthPromotPerspect. 2015;5(3):156–68.

34.MoherD,LiberatiA,TetzlaffJ,etal.Preferredreportingitemsfor systematicreviewsandmeta-analyses:thePRISMAstatement. PLoSMed. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

35.CwikMF,TingeyL,LeeA,etal.Developmentandpilotingofabrief interventionforsuicidalAmericanIndianadolescents. AmIndianAlsk NativeMentHealthRes. 2016;23(1):105–24.

36.HatcherS,CoupeN,WikiriwhiK,etal.TeIraTangata:aZelen randomisedcontrolledtrialofaculturallyinformedtreatmentcompared totreatmentasusualinMaoriwhopresenttohospitalafterself-harm. SocPsychiatryPsychiatrEpidemiol. 2016;51(6):885–94.

37.MillerIW,CamargoCAJr.,AriasSA,etal.Suicidepreventioninan emergencydepartmentpopulation:theED-SAFEstudy. JAMAPsychiatry. 2017;74(6):563–70.

38.BryanCJ,MintzJ,ClemansTA,etal.Effectofcrisisresponseplanning onpatientmoodandcliniciandecisionmaking:aclinicaltrialwith suicidalU.S.soldiers. PsychiatrServ. 2018;69(1):108–11.

39.FurunoT,NakagawaM,HinoK,etal.Effectivenessofassertivecase managementonrepeatself-harminpatientsadmittedforsuicide attempt: findingsfromACTION-Jstudy. JAffectDisord. 2018;225:460–5.

40.BurgerJ,CapobiancoM,LovernR,etal.Adouble-blinded,randomized, placebo-controlledsub-dissociativedoseketaminepilotstudyinthe treatmentofacutedepressionandsuicidalityinamilitaryemergency departmentsetting. MilMed. 2016;181(10):1195–9.

41.DomanyYandMcCullumsmithCB.Single, fixed-doseintranasal ketamineforalleviationofacutesuicidalideation.Anemergency department,trans-diagnosticapproach:arandomized,double-blind,

placebo-controlled,proof-of-concepttrial. ArchSuicideRes. 2022;26(3):1250–65.

42.DomanyY,SheltonRC,McCullumSmithCB.Ketamineforacute suicidalideation.Anemergencydepartmentintervention:A randomized,double-blind,placebo-controlled,proof-of-concepttrial. DepressAnxiety. 2020;37(3):224–33.

43.KashaniP,YousefianS,AminiA,etal.Theeffectofintravenous ketamineinsuicidalideationofemergencydepartmentpatients. Emerg(Tehran). 2014;2(1):36–9.

44.Grupp-PhelanJ,StevensJ,BoydS,etal.Effectofamotivational interviewing-basedinterventiononinitiationofmentalhealthtreatment andmentalhealthafteranemergencydepartmentvisitamong suicidaladolescents:arandomizedclinicaltrial. JAMANetwOpen. 2019;2(12):e1917941.

45.KingCA,GipsonPY,HorwitzAG,etal.Teenoptionsforchange:an interventionforyoungemergencypatientswhoscreenpositivefor suiciderisk. PsychiatrServ. 2015;66(1):97–100.

46.KawanishiC,ArugaT,IshizukaN,etal.Assertivecasemanagement versusenhancedusualcareforpeoplewithmentalhealthproblemswho hadattemptedsuicideandwereadmittedtohospitalemergency departmentsinJapan(ACTION-J):amulticentre,randomisedcontrolled trial. LancetPsychiatry. 2014;1(3):193–201.

47.AlonzoD.Suicidalindividualsandmentalhealthtreatment: anovelapproachtoengagement. CommunityMentHealthJ. 2016;52(5):527–33.

48.XiongJ,LipsitzO,Chen-LiD,etal.Theacuteantisuicidaleffectsof single-doseintravenousketamineandintranasalesketaminein individualswithmajordepressionandbipolardisorders:asystematic reviewandmeta-analysis. JPsychiatrRes. 2021;134:57–68.

49.BrendleM,RobisonR,MaloneDC.Cost-effectivenessofesketamine nasalspraycomparedtointravenousketamineforpatientswith treatment-resistantdepressionintheUSutilizingclinicaltrialefficacy andreal-worldeffectivenessestimates. JAffectDisord. 2022;319:388–96.

50.RabascoA,AriasS,BenzMB,etal.Longitudinalriskofsuicide outcomesinpeoplewithseverementalillnessfollowinganemergency departmentvisitandtheeffectsofsuicidepreventiontreatment. JAffectDisord. 2024;347:477–85.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH Buprenorphine-NaloxoneforOpioidUseDisorder: ReductioninMortalityandIncreasedRemission KrishnaK.Paul,BS*

ChristianG.Frey,BS*

StanleyTroung,BA*

LauravitaQ.Paglicawan,BS*

KathrynA.Cunningham,PhD†

T.PrestonHill,MD*

LaurenG.Bothwell*

GeorgiyGolovko,PhD†

YeoshinaPillay,MD‡

DietrichJehle,MD*

SectionEditor:BradBobrin,MD

*DepartmentofEmergencyMedicine,UniversityofTexasMedicalBranch, Galveston,Texas

† DepartmentofPharmacologyandToxicology,UniversityofTexasMedical Branch,Galveston,Texas

‡ DepartmentofEmergencyMedicine,MichiganStateUniversity, EastLansing,Michigan

Submissionhistory:SubmittedDecember15,2023;RevisionreceivedJuly5,2024;AcceptedJuly11,2024

ElectronicallypublishedSeptember6,2024

Fulltextavailablethroughopenaccessat http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem DOI: 10.5811/westjem.18569

Introduction: Asfentanylhasbecomemorereadilyavailable,opioid-relatedmorbidityandmortalityin theUnitedStateshasincreaseddramatically.Preliminarystudiessuggestthathigh-affinity,partialmuopioidreceptoragonistssuchasthecombinationproductbuprenorphine-naloxonemayreducemortality fromoverdoseandpromoteremission.Withtheescalatingprevalenceofopioidusedisorder(OUD),itis essentialtoevaluatetheeffectivenessofopioidagonistslikebuprenorphine-naloxone.Thisstudy examinesmortalityandremissionratesforOUDpatientsprescribedbuprenorphine-naloxoneto determinetheef ficacyofthistreatmenttowardtheseoutcomes.

Methods: WecarriedoutaretrospectiveanalysisusingtheUSCollaborativeNetworkdatabasein TriNetX,examiningde-identifiedmedicalrecordsfromnearly92millionpatientsacross56healthcare organizations.ThestudyspannedtheyearsfromJanuary1,2017–May13,2022.Cohort1included OUDpatientswhobeganbuprenorphine-naloxonetreatmentwithinone-yearpost-diagnosis,while Cohort2,thecontrolgroup,consistedofOUDpatientswhowerenotadministeredbuprenorphine.The studymeasuredmortalityandremissionrateswithinayearoftheindexevent,incorporatingpropensity scorematchingforage,gender,andrace/ethnicity.

Results: Priortopropensitymatching,weidentifiedatotalof221,967patientswithOUD.Following exclusions,61,656patientstreatedwithbuprenorphine-naloxoneshowed34%fewerdeathswithinone yearofdiagnosiscomparedto159,061patientswhodidnotreceivebuprenorphine(2.6%vs4.0%; relativerisk[RR]0.661;95%confidenceinterval[CI]0.627–0.698; P < 0.001).Theremissionratewas approximately1.9timeshigherinthebuprenorphine-naloxonegroupcomparedtothecontrolgroup (18.8%vs10.1%;RR1.862;95%CI1.812–1.914; P < 0.001).Afterpropensitymatching,theeffecton mortalitydecreasedbutremainedstatisticallysignificant(2.6%vs3.0%;RR0.868;95%CI0.813–0.927; P < 0.001)andtheremissionrateremainedconsistent(18.8%vs10.4%;RR1.812;95%CI 1.750–1.876; P < 0.001).Numberneededtotreatforbenefitwas249fordeathand12forremission.

Conclusion: Buprenorphine-naloxonewasassociatedwithsignificantlyreducedmortalityand increasedremissionratesforpatientswithopioidusedisorderandshouldbeusedasaprimary treatment.Therecognitionandimplementationoftreatmentoptionslikebuprenorphine-naloxoneisvital inalleviatingtheimpactofOUD.[WestJEmergMed.2024;25(6)869–874.]

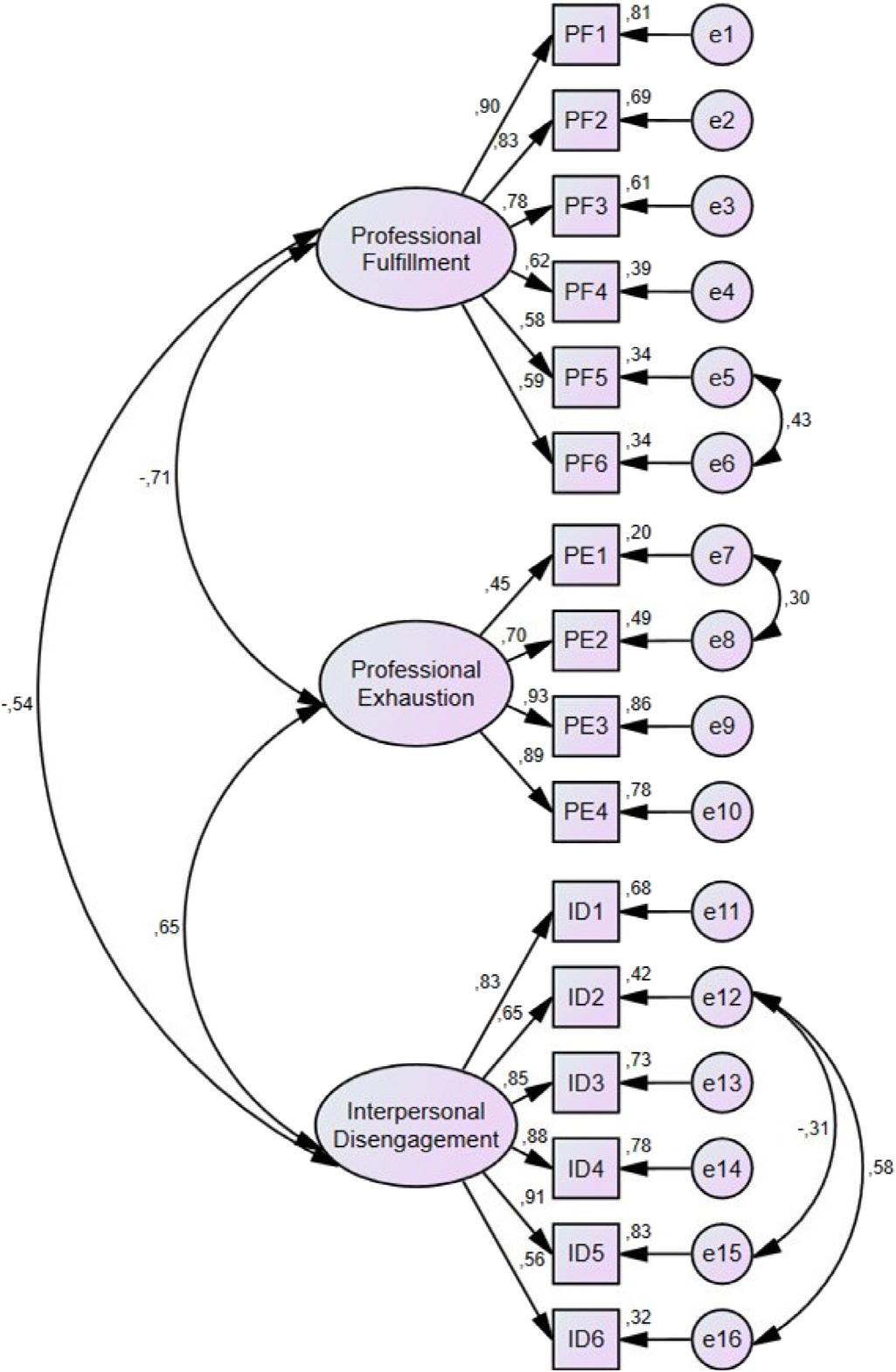

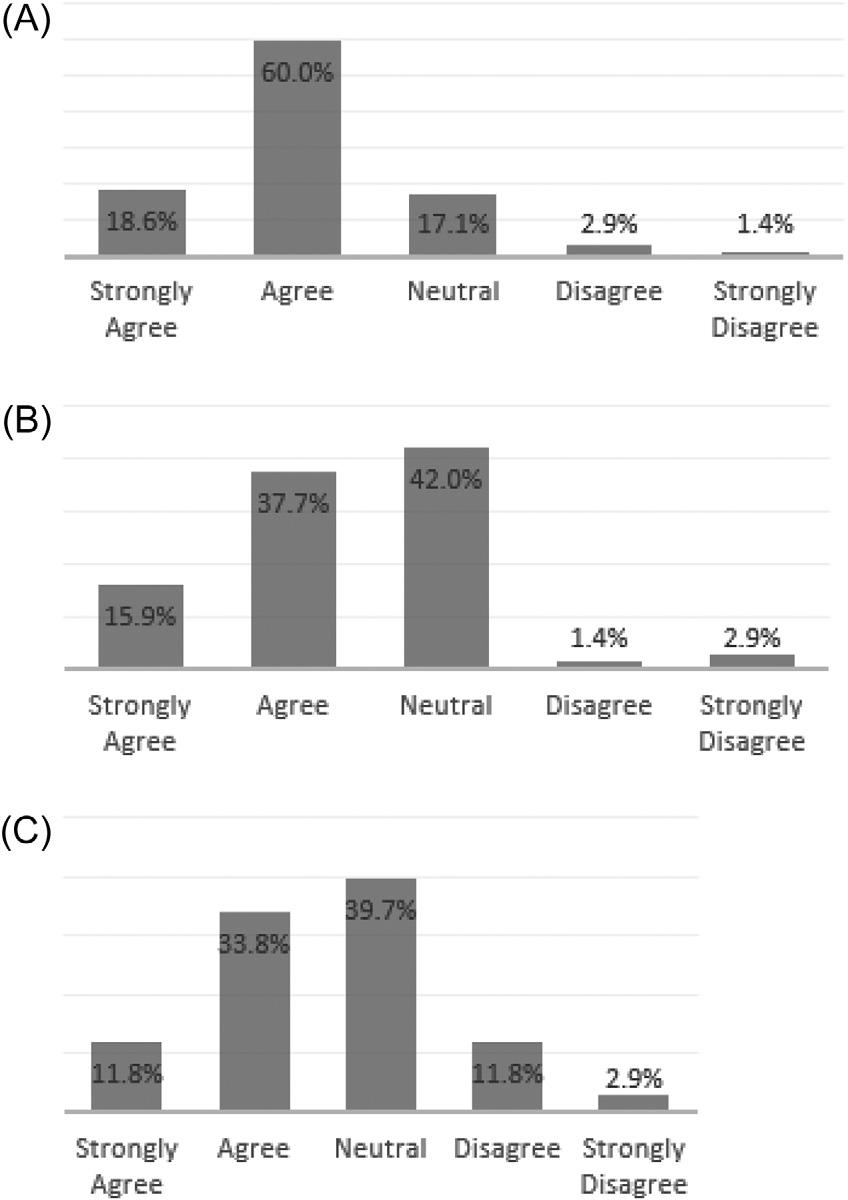

INTRODUCTION Background