Western Journal of Emergency Medicine:

Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

Indexed in MEDLINE

Health Equity

654 Addressing Emergency Department Care for Patients Experiencing Incarceration: A Narrative Review

Rachel E. Armstrong, Kristopher A. Hendershot, Naomi P. Newton, Patricia D. Panakos

662 A Virtual National Diversity Mentoring Initiative to Promote Inclusion in Emergency Medicine

Tatiana Carrillo, Lorena Martinez Rodriguez, Adaira Landry, Al’ai Alvarez, Alyssa Ceniza, Riane Gay, Andrea Green, Jessica Faiz

668 Skin Tone and Gender of High-Fidelity Simulation Manikins in Emergency Medicine Residency Training and their Use in Cultural Humility Training

Marie Anderson Wofford, Cortlyn Brown, Bernard Walston, Heidi Whiteside, Joseph Rigdon, Phil Turk

675 Social Determinants of Health Screening at an Urban Emergency Department Urgent Care During COVID-19

Haeyeon Hong, Kalpana Narayan Shankar, Andrew Thompson, Pablo Buitron De La Vega, Rashmi Koul, Emily C. Cleveland Manchanda, Sorraya Jaiprasert, Samantha Roberts, Tyler Pina, Emily Anderson, Jessica Lin, Gabrielle A. Jacquet

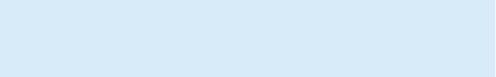

680 A National Snapshot of Social Determinants of Health Documentation in Emergency Departments

Caitlin R. Ryus, Alexander T. Janke, Rachel L. Granovsky, Michael A. Granovsky

ED Operations

685 A Real-World Experience: Retrospective Review of Point-of-Care Ultrasound Utilization and Quality in Community Emergency Departments

Courtney M. Smalley, Erin L. Simon, McKinsey R. Muir, Baruch S. Fertel

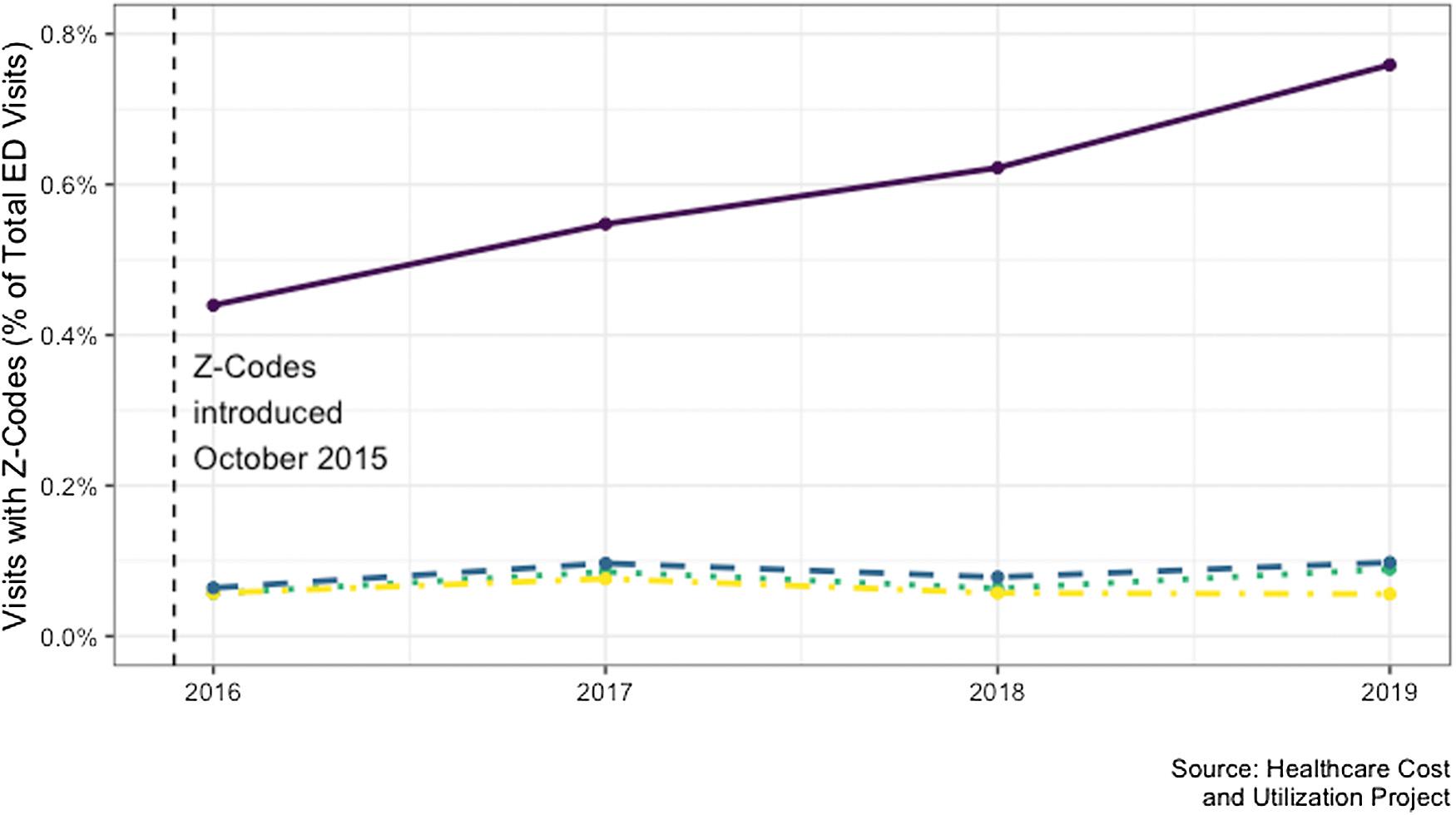

693 Applying a Smartwatch to Predict Work-related Fatigue for Emergency Healthcare Professionals: Machine Learning Method

Sot Shih-Hung Liu, Cheng-Jiun Ma, Fan-Ya Chou, Michelle Yuan-Chiao Cheng, Chih-Hung Wang, Chu-Lin Tsai, Wei-Jou Duh, Chien-Hua Huang, Feipei Lai, Tsung-Chien Lu

Contents continued on page iii

Volume 24, Number 4, July 2023 Open Access at WestJEM.com ISSN 1936-900X A Peer-Reviewed, International Professional Journal Western Journal of Emergency Medicine VOLUME 24, NUMBER 4, July 2023 PAGES 654-872

West

Andrew W. Phillips, MD, Associate Editor DHR Health-Edinburg, Texas

Edward Michelson, MD, Associate Editor Texas Tech University- El Paso, Texas

Dan Mayer, MD, Associate Editor Retired from Albany Medical College- Niskayuna, New York

Wendy Macias-Konstantopoulos, MD, MPH, Associate Editor Massachusetts General Hospital- Boston, Massachusetts

Gayle Galletta, MD, Associate Editor University of Massachusetts Medical SchoolWorcester, Massachusetts

Yanina Purim-Shem-Tov, MD, MS, Associate Editor Rush University Medical Center-Chicago, Illinois

Resident Editors

AAEM/RSA

John J. Campo, MD Harbor-University of California, Los Angeles Medical Center

Tehreem Rehman, MD

Advocate Christ Medical Center

ACOEP

Justina Truong, DO

Kingman Regional Medical Center

Section Editors

Behavioral Emergencies

Leslie Zun, MD, MBA Chicago Medical School

Marc L. Martel, MD

Hennepin County Medical Center

Cardiac Care

Fred A. Severyn, MD

University of Colorado School of Medicine

Sam S. Torbati, MD

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center

Clinical Practice

Cortlyn W. Brown, MD Carolinas Medical Center

Casey Clements, MD, PhD Mayo Clinic

Patrick Meloy, MD

Emory University

Nicholas Pettit, DO, PhD

Indiana University

David Thompson, MD University of California, San Francisco

Kenneth S. Whitlow, DO

Kaweah Delta Medical Center

Critical Care

Christopher “Kit” Tainter, MD

University of California, San Diego

Gabriel Wardi, MD

University of California, San Diego

Joseph Shiber, MD

University of Florida-College of Medicine

Matt Prekker MD, MPH

Hennepin County Medical Center

David Page, MD

University of Alabama

Erik Melnychuk, MD

Geisinger Health

Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

University of Maryland

Mark I. Langdorf, MD, MHPE, Editor-in-Chief University of California, Irvine School of MedicineIrvine, California

Shahram Lotfipour, MD, MPH, Managing Editor University of California, Irvine School of MedicineIrvine, California

Michael Gottlieb, MD, Associate Editor Rush Medical Center-Chicago, Illinois

Niels K. Rathlev, MD, Associate Editor Tufts University School of Medicine-Boston, Massachusetts

Rick A. McPheeters, DO, Associate Editor Kern Medical- Bakersfield, California

Gentry Wilkerson, MD, Associate Editor University of Maryland

Disaster Medicine

John Broach, MD, MPH, MBA, FACEP

University of Massachusetts Medical School UMass Memorial Medical Center

Christopher Kang, MD Madigan Army Medical Center

Education

Danya Khoujah, MBBS

University of Maryland School of Medicine

Jeffrey Druck, MD University of Colorado

John Burkhardt, MD, MA University of Michigan Medical School

Michael Epter, DO Maricopa Medical Center

ED Administration, Quality, Safety

David C. Lee, MD Northshore University Hospital

Gary Johnson, MD Upstate Medical University

Brian J. Yun, MD, MBA, MPH

Harvard Medical School

Laura Walker, MD Mayo Clinic

León D. Sánchez, MD, MPH Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

William Fernandez, MD, MPH

University of Texas Health-San Antonio

Robert Derlet, MD

Founding Editor, California Journal of Emergency Medicine

University of California, Davis

Emergency Medical Services

Daniel Joseph, MD

Yale University

Joshua B. Gaither, MD

University of Arizona, Tuscon

Julian Mapp

University of Texas, San Antonio

Shira A. Schlesinger, MD, MPH

Harbor-UCLA Medical Center

Geriatrics

Cameron Gettel, MD Yale School of Medicine

Stephen Meldon, MD Cleveland Clinic

Luna Ragsdale, MD, MPH

Duke University

Health Equity

Emily C. Manchanda, MD, MPH

Boston University School of Medicine

Shadi Lahham, MD, MS, Deputy Editor Kaiser Permanente- Irvine, California

Susan R. Wilcox, MD, Associate Editor Massachusetts General Hospital- Boston, Massachusetts

Elizabeth Burner, MD, MPH, Associate Editor University of Southern California- Los Angeles, California

Patrick Joseph Maher, MD, MS, Associate Editor Ichan School of Medicine at Mount Sinai- New York, New York

Donna Mendez, MD, EdD, Associate Editor University of Texas-Houston/McGovern Medical School- Houston Texas

Danya Khoujah, MBBS, Associate Editor

University of Maryland School of Medicine- Baltimore, Maryland

Faith Quenzer Temecula Valley Hospital

San Ysidro Health Center

Mandy J. Hill, DrPH, MPH

UT Health McGovern Medical School

Payal Modi, MD MScPH

University of Massachusetts Medical

Infectious Disease

Elissa Schechter-Perkins, MD, MPH

Boston University School of Medicine

Ioannis Koutroulis, MD, MBA, PhD

George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences

Kevin Lunney, MD, MHS, PhD

University of Maryland School of Medicine

Stephen Liang, MD, MPHS

Washington University School of Medicine

Victor Cisneros, MD, MPH

Eisenhower Medical Center

Injury Prevention

Mark Faul, PhD, MA

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Wirachin Hoonpongsimanont, MD, MSBATS

Eisenhower Medical Center

International Medicine

Heather A.. Brown, MD, MPH

Prisma Health Richland

Taylor Burkholder, MD, MPH

Keck School of Medicine of USC

Christopher Greene, MD, MPH

University of Alabama

Chris Mills, MD, MPH

Santa Clara Valley Medical Center

Shada Rouhani, MD

Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Legal Medicine

Melanie S. Heniff, MD, JD

Indiana University School of Medicine

Greg P. Moore, MD, JD

Madigan Army Medical Center

Statistics and Methodology

Shu B. Chan MD, MS Resurrection Medical Center

Stormy M. Morales Monks, PhD, MPH Texas Tech Health Science University

Soheil Saadat, MD, MPH, PhD University of California, Irvine

James A. Meltzer, MD, MS

Albert Einstein College of Medicine

Musculoskeletal

Juan F. Acosta DO, MS Pacific Northwest University

Rick Lucarelli, MD

Medical City Dallas Hospital

William D. Whetstone, MD

University of California, San Francisco

Neurosciences

Antonio Siniscalchi, MD

Annunziata Hospital, Cosenza, Italy

Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Paul Walsh, MD, MSc

University of California, Davis

Muhammad Waseem, MD

Lincoln Medical & Mental Health Center

Cristina M. Zeretzke-Bien, MD University of Florida

Public Health

Jacob Manteuffel, MD

Henry Ford Hospital

John Ashurst, DO

Lehigh Valley Health Network

Tony Zitek, MD

Kendall Regional Medical Center

Trevor Mills, MD, MPH

Northern California VA Health Care

Erik S. Anderson, MD

Alameda Health System-Highland Hospital

Technology in Emergency Medicine

Nikhil Goyal, MD

Henry Ford Hospital

Phillips Perera, MD

Stanford University Medical Center

Trauma

Pierre Borczuk, MD

Massachusetts General Hospital/Havard Medical School

Toxicology

Brandon Wills, DO, MS

Virginia Commonwealth University

Jeffrey R. Suchard, MD University of California, Irvine

Ultrasound

J. Matthew Fields, MD

Thomas Jefferson University

Shane Summers, MD

Brooke Army Medical Center

Robert R. Ehrman

Wayne State University

Ryan C. Gibbons, MD

Temple Health

Official Journal of the California Chapter of the American College of Emergency Physicians, the America College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians, and the California Chapter of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Volume 24, No. 4: July 2023 i Western Journal of Emergency Medicine Available in MEDLINE, PubMed, PubMed Central, CINAHL, SCOPUS, Google Scholar, eScholarship, Melvyl, DOAJ, EBSCO, EMBASE, Medscape, HINARI, and MDLinx Emergency Med. Members of OASPA. Editorial and Publishing Office: WestJEM/Depatment of Emergency Medicine, UC Irvine Health, 3800 W. Chapman Ave. Suite 3200, Orange, CA 92868, USA Office: 1-714-456-6389; Email: Editor@westjem.org

Medicine

Emergency

Population Health Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

Western Journal of Emergency

: Integrating

Care with

Western

Amin A. Kazzi, MD, MAAEM The American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon

Anwar Al-Awadhi, MD

Mubarak Al-Kabeer Hospital, Jabriya, Kuwait

Arif A. Cevik, MD United Arab Emirates University College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Al Ain, United Arab Emirates

Abhinandan A.Desai, MD University of Bombay Grant Medical College, Bombay, India

Bandr Mzahim, MD King Fahad Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Brent King, MD, MMM University of Texas, Houston

Christopher E. San Miguel, MD Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center

Daniel J. Dire, MD University of Texas Health Sciences Center San Antonio

David F.M. Brown, MD Massachusetts General Hospital/ Harvard Medical School

Douglas Ander, MD Emory University

Editorial Board

Edward Michelson, MD Texas Tech University

Edward Panacek, MD, MPH University of South Alabama

Francesco Della Corte, MD

Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria

“Maggiore della Carità,” Novara, Italy

Francis Counselman, MD Eastern Virginia Medical School

Gayle Galleta, MD

Sørlandet Sykehus HF, Akershus Universitetssykehus, Lorenskog, Norway

Hjalti Björnsson, MD Icelandic Society of Emergency Medicine

Jacob (Kobi) Peleg, PhD, MPH Tel-Aviv University, Tel-Aviv, Israel

Jaqueline Le, MD Desert Regional Medical Center

Jeffrey Love, MD The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences

Jonathan Olshaker, MD Boston University

Katsuhiro Kanemaru, MD University of Miyazaki Hospital, Miyazaki, Japan

Kenneth V. Iserson, MD, MBA University of Arizona, Tucson

Khrongwong Musikatavorn, MD King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand

Leslie Zun, MD, MBA Chicago Medical School

Linda S. Murphy, MLIS University of California, Irvine School of Medicine Librarian

Nadeem Qureshi, MD St. Louis University, USA Emirates Society of Emergency Medicine, United Arab Emirates

Niels K. Rathlev, MD Tufts University School of Medicine

Pablo Aguilera Fuenzalida, MD Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Región Metropolitana, Chile

Peter A. Bell, DO, MBA Baptist Health Sciences University

Peter Sokolove, MD University of California, San Francisco

Rachel A. Lindor, MD, JD Mayo Clinic

Robert M. Rodriguez, MD University of California, San Francisco

Robert Suter, DO, MHA UT Southwestern Medical Center

Robert W. Derlet, MD University of California, Davis

Rosidah Ibrahim, MD Hospital Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia

Samuel J. Stratton, MD, MPH Orange County, CA, EMS Agency

Scott Rudkin, MD, MBA University of California, Irvine

Scott Zeller, MD University of California, Riverside

Steven H. Lim, MD Changi General Hospital, Simei, Singapore

Terry Mulligan, DO, MPH, FIFEM

ACEP Ambassador to the Netherlands Society of Emergency Physicians

Vijay Gautam, MBBS University of London, London, England

Wirachin Hoonpongsimanont, MD, MSBATS

Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand

Editorial Staff Advisory Board

Elena Lopez-Gusman, JD California ACEP American College of Emergency Physicians

Jennifer Kanapicki Comer, MD FAAEM California Chapter Division of AAEM Stanford University School of Medicine

DeAnna McNett, CAE American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians

Kimberly Ang, MBA UC Irvine Health School of Medicine

Randall J. Young, MD, MMM, FACEP California ACEP American College of Emergency Physicians Kaiser Permanente

Mark I. Langdorf, MD, MHPE, MAAEM, FACEP UC Irvine Health School of Medicine

Robert Suter, DO, MHA American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians UT Southwestern Medical Center

Shahram Lotfipour, MD, MPH FAAEM, FACEP UC Irvine Health School of Medicine

Jorge Fernandez, MD, FACEP UC San Diego Health School of Medicine

Isabelle Nepomuceno, BS Executive Editorial Director

Visha Bajaria, BS WestJEM Editorial Director

Emily Kane, MA WestJEM Editorial Director

Stephanie Burmeister, MLIS WestJEM Staff Liaison

Cassandra Saucedo, MS Executive Publishing Director

Nicole Valenzi, BA WestJEM Publishing Director

June Casey, BA Copy Editor

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine ii Volume 24, No. 4: July 2023 Available in MEDLINE, PubMed, PubMed Central, Europe PubMed Central, PubMed Central Canada, CINAHL, SCOPUS, Google Scholar, eScholarship, Melvyl, DOAJ, EBSCO, EMBASE, Medscape, HINARI, and MDLinx Emergency Med. Members of OASPA. Editorial and Publishing Office: WestJEM/Depatment of Emergency Medicine, UC Irvine Health, 3800 W. Chapman Ave. Suite 3200, Orange, CA 92868, USA Office: 1-714-456-6389; Email: Editor@westjem.org Official Journal of the California Chapter of the American College of Emergency Physicians, the America College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians, and the California Chapter of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

Journal of Emergency Medicine:

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine:

Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

JOURNAL FOCUS

Emergency medicine is a specialty which closely reflects societal challenges and consequences of public policy decisions. The emergency department specifically deals with social injustice, health and economic disparities, violence, substance abuse, and disaster preparedness and response. This journal focuses on how emergency care affects the health of the community and population, and conversely, how these societal challenges affect the composition of the patient population who seek care in the emergency department. The development of better systems to provide emergency care, including technology solutions, is critical to enhancing population health.

Table of Contents

703 Impact of Care Initiation Model on Emergency Department Orders and Operational Metrics: Cohort Study

Andy Hung-Yi Lee, Rebecca E. Cash, Alice Bukhman, Dana Im, Damarcus Baymon, Leon D Sanchez, Paul C. Chen

Behavioral Health

710 Disparities in Emergency Department Naloxone and Buprenorphine Initiation

Joan Papp, Charles Louis Emerman

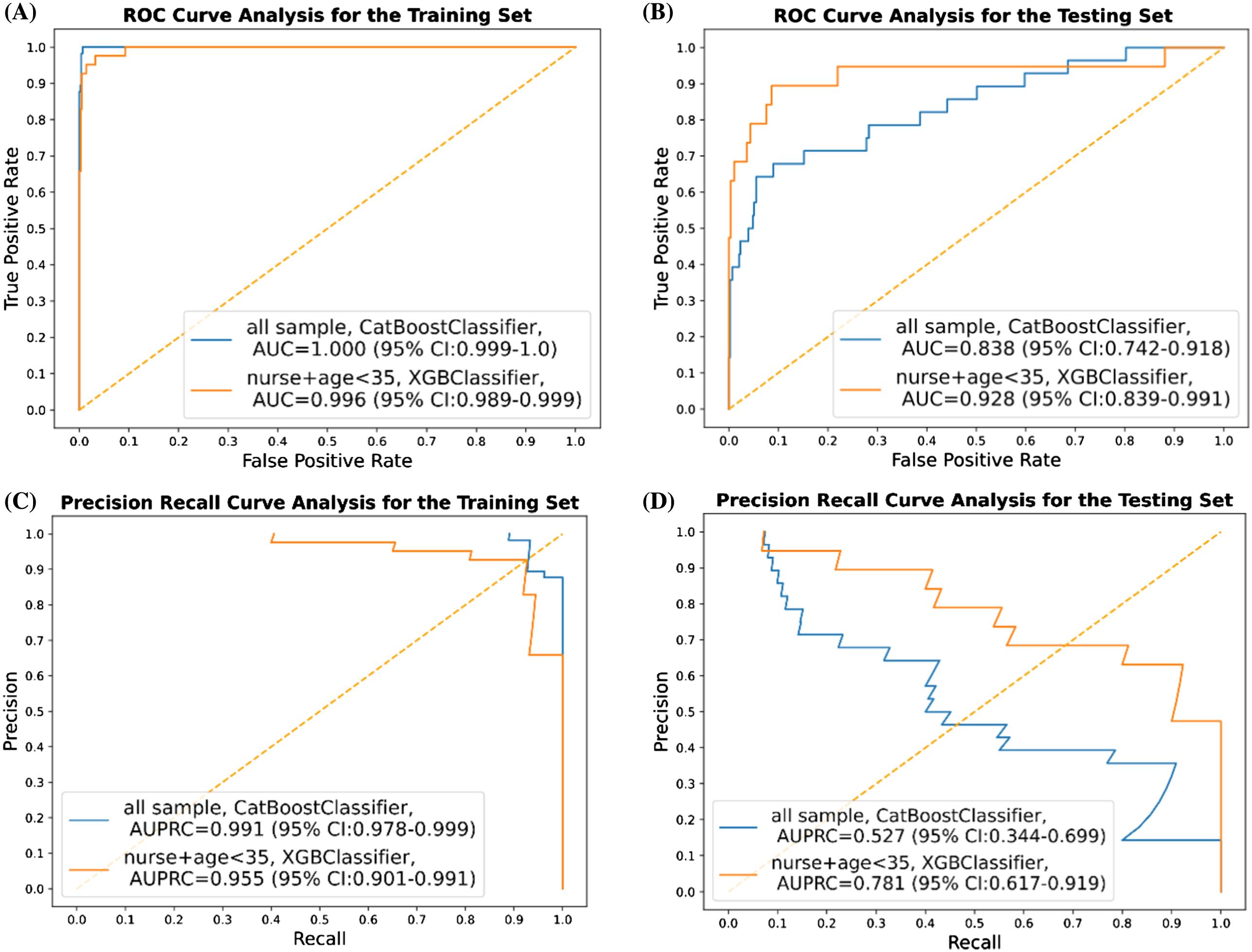

717 Flow through the Emergency Department for Patients Presenting with Substance Use Disorder in Alberta, Canada

Jonah Edmundson, Kevin Skoblenick, Rhonda J. Rosychuk

Education

728 Perception of Quiet Students in Emergency Medicine: An Exploration of Narratives in the Standardized Letter of Evaluation

John K. Quinn, Jillian Mongelluzzo, Alyssa Nip, Joe Graterol, Esther H. Chen

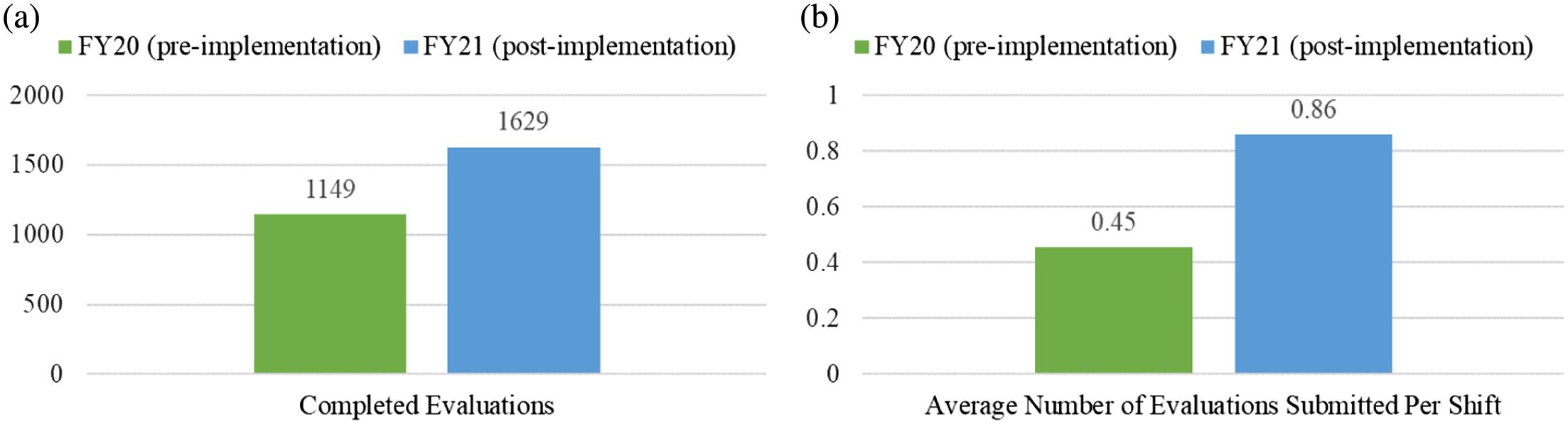

732 Impact of Faculty Incentivization on Resident Evaluations

Viral Patel, Alexandra Nordberg, Richard Church, Jennifer L. Carey

Health Outcomes

737 Single-step Optimization in Triaging Large Vessel Occlusion Strokes: Identifying Factors to Improve Door-to-groin Time for Endovascular Therapy

Joshua Rawson, Ashley Petrone, Amelia Adcock

743

Violence and Abuse: A Pandemic Within a Pandemic

Paula J. Whiteman, Wendy L. Macias-Konstantopoulos, Pryanka Relan, Anita Knopov, Megan L. Ranney, Ralph J. Riviello

Critical Care

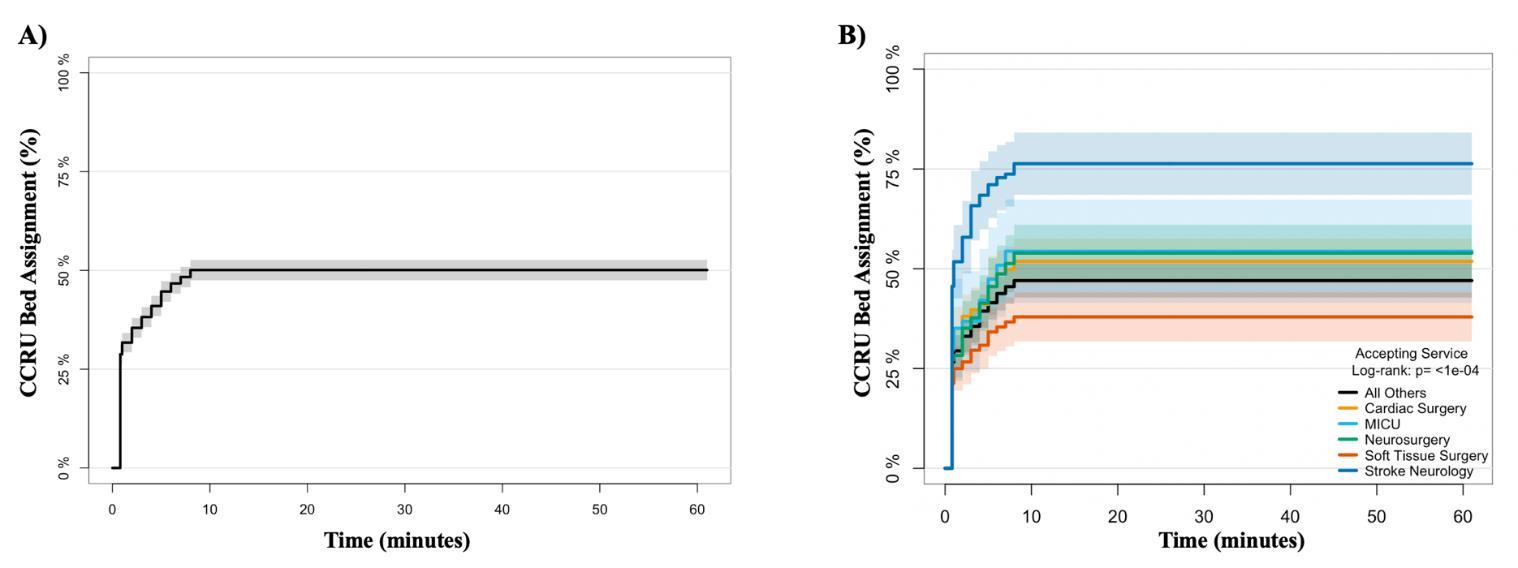

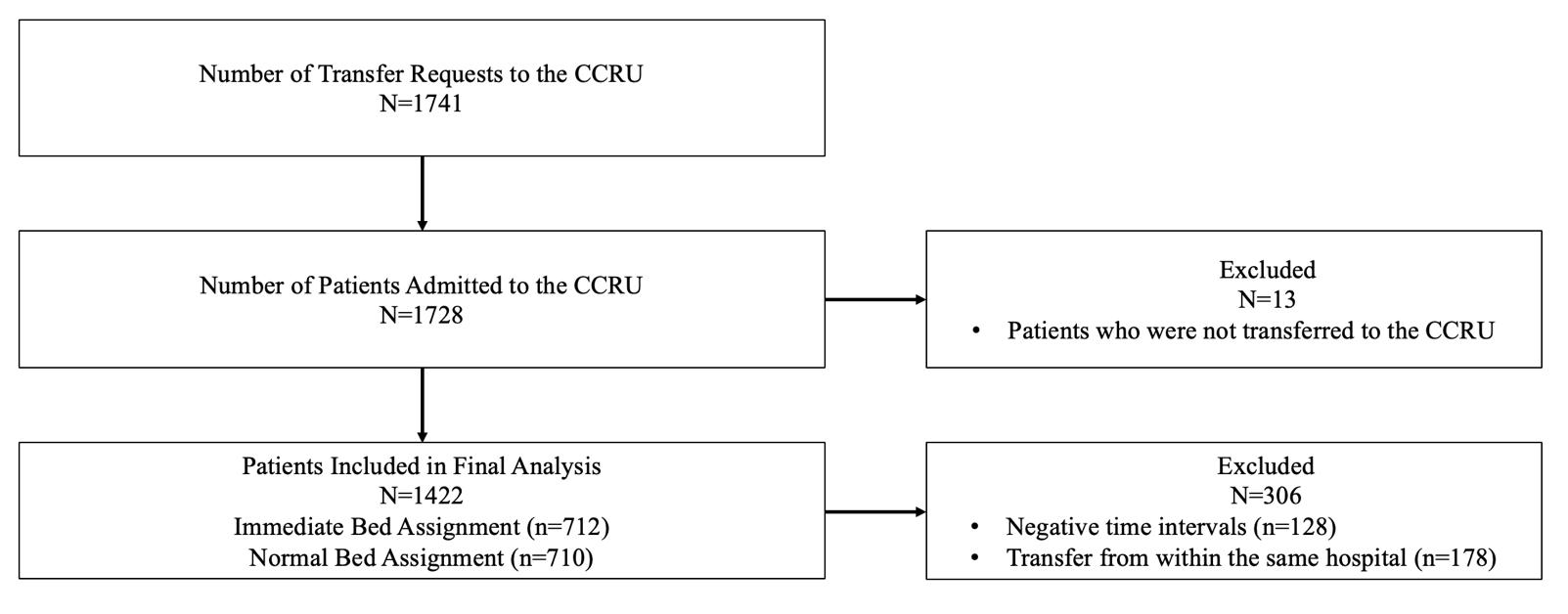

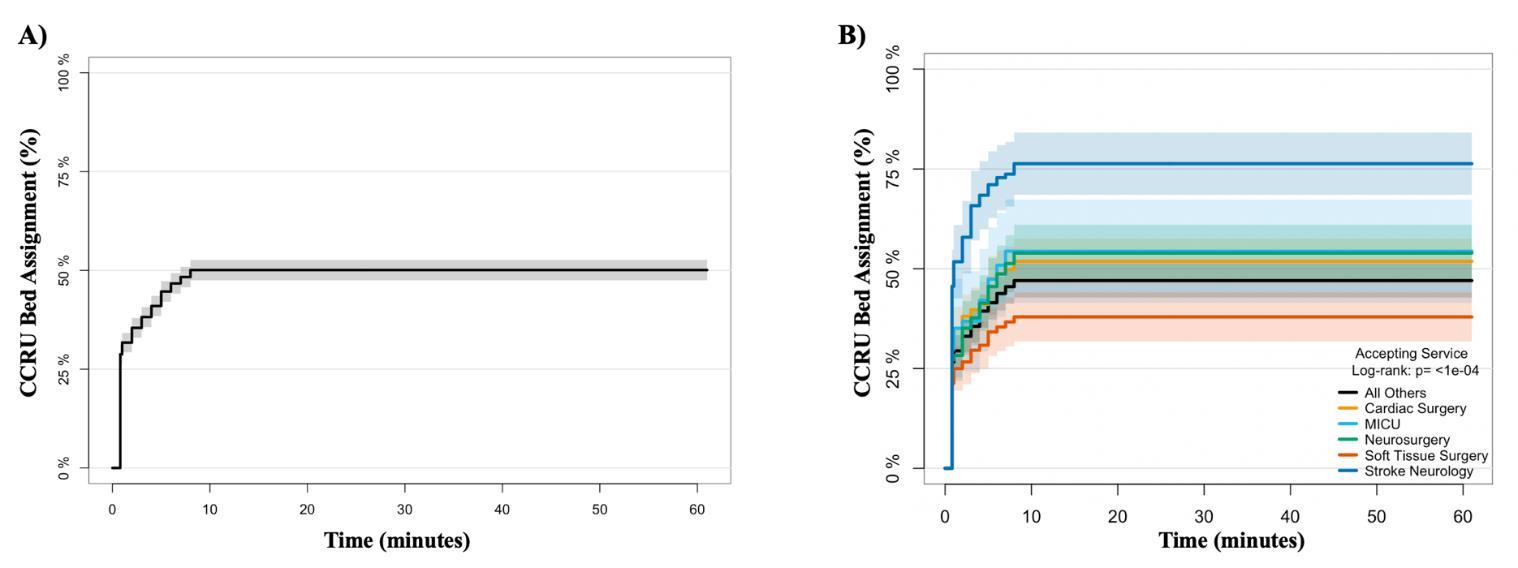

751 Examining Predictors of Early Admission and Transfer to the Critical Care Resuscitation Unit

Quincy K. Tran, Daniel Najafali, Tiffany Cao, Megan Najafali, Nelson Chen, Iana Sahadzic, Ikram Afridi, Ann Matta, William Teeter, Daniel J. Haase

763 Arterial Monitoring in Hypertensive Emergencies: Significance for the Critical Care Resuscitation Unit

Quincy K. Tran, Dominique Gelmann, Manahel Zahid, Jamie Palmer, Grace Hollis, Emily Engelbrecht-Wiggans, Zain Alam, Ann Elizabeth Matta, Emily Hart, Daniel J. Haase

Technology

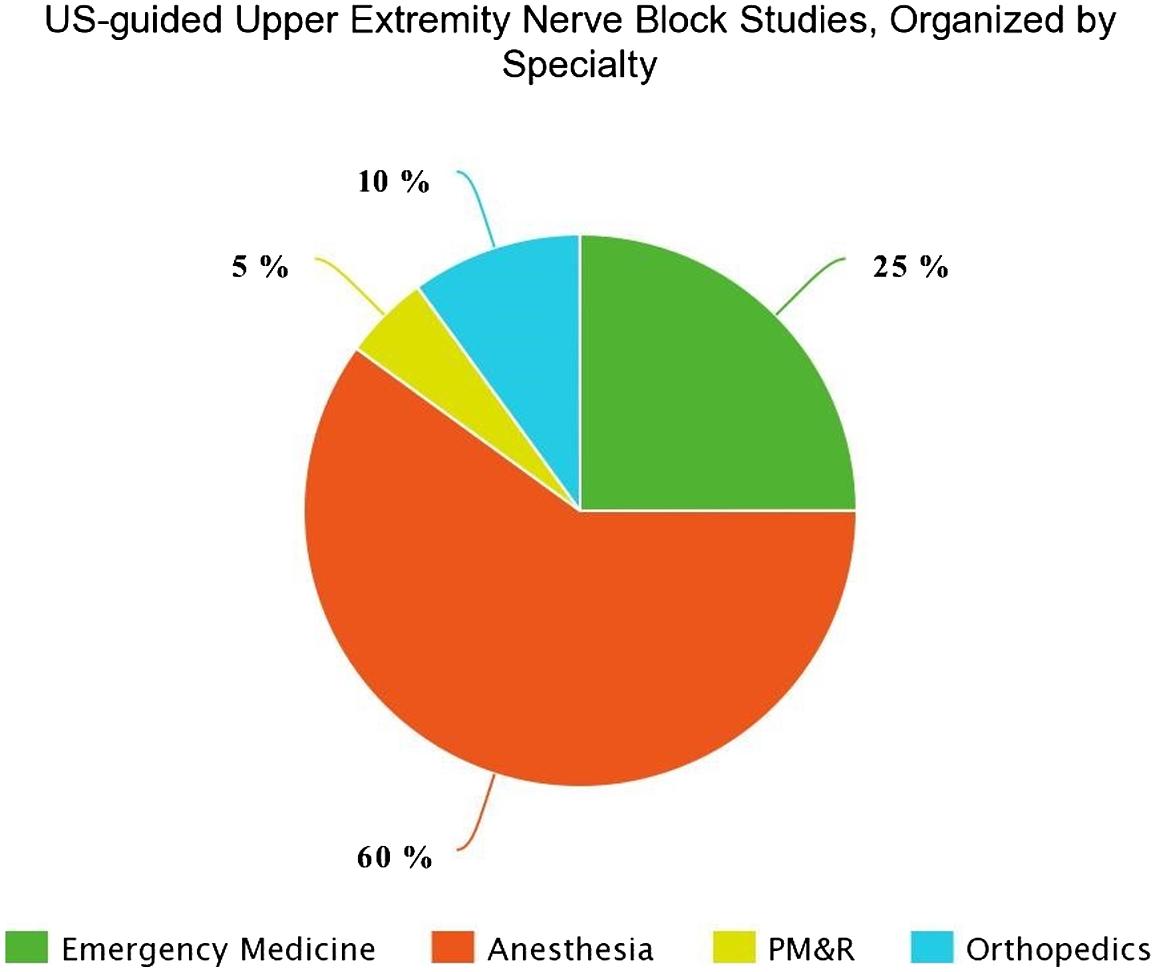

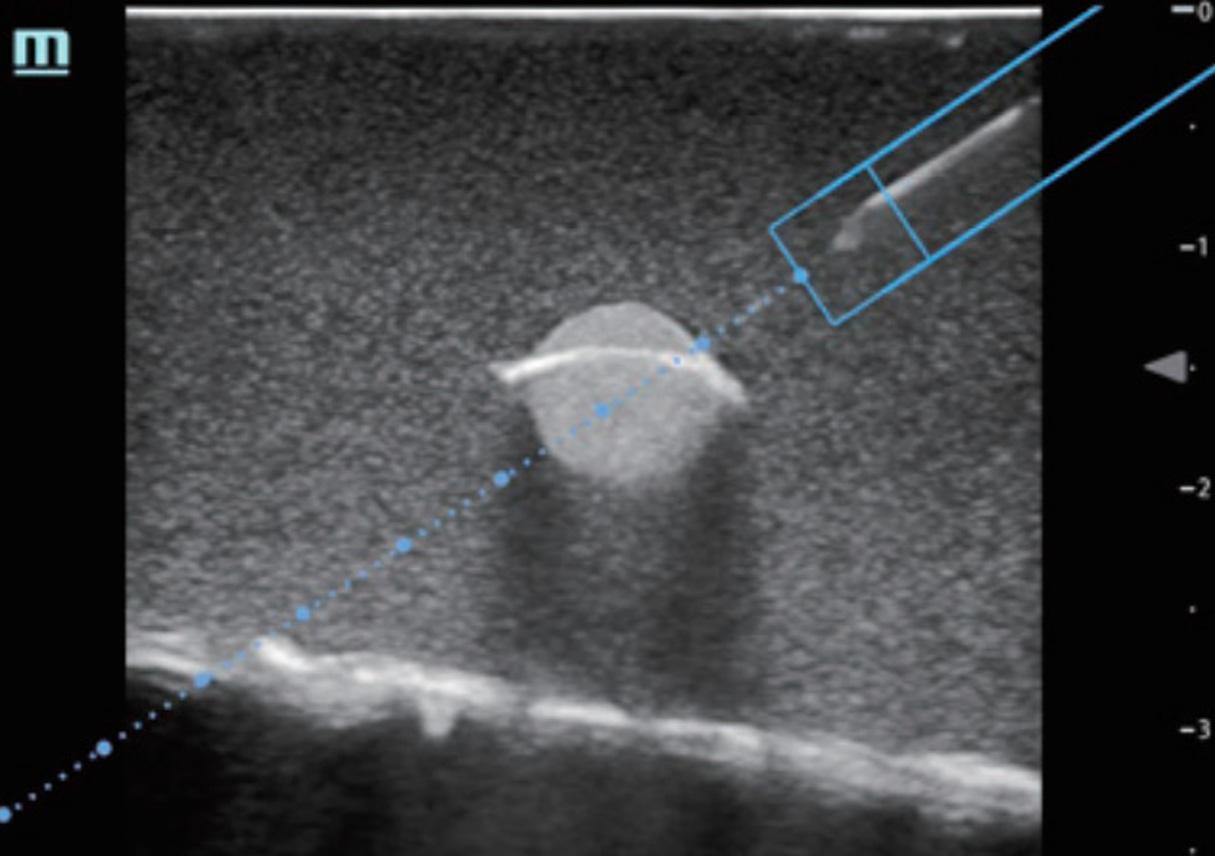

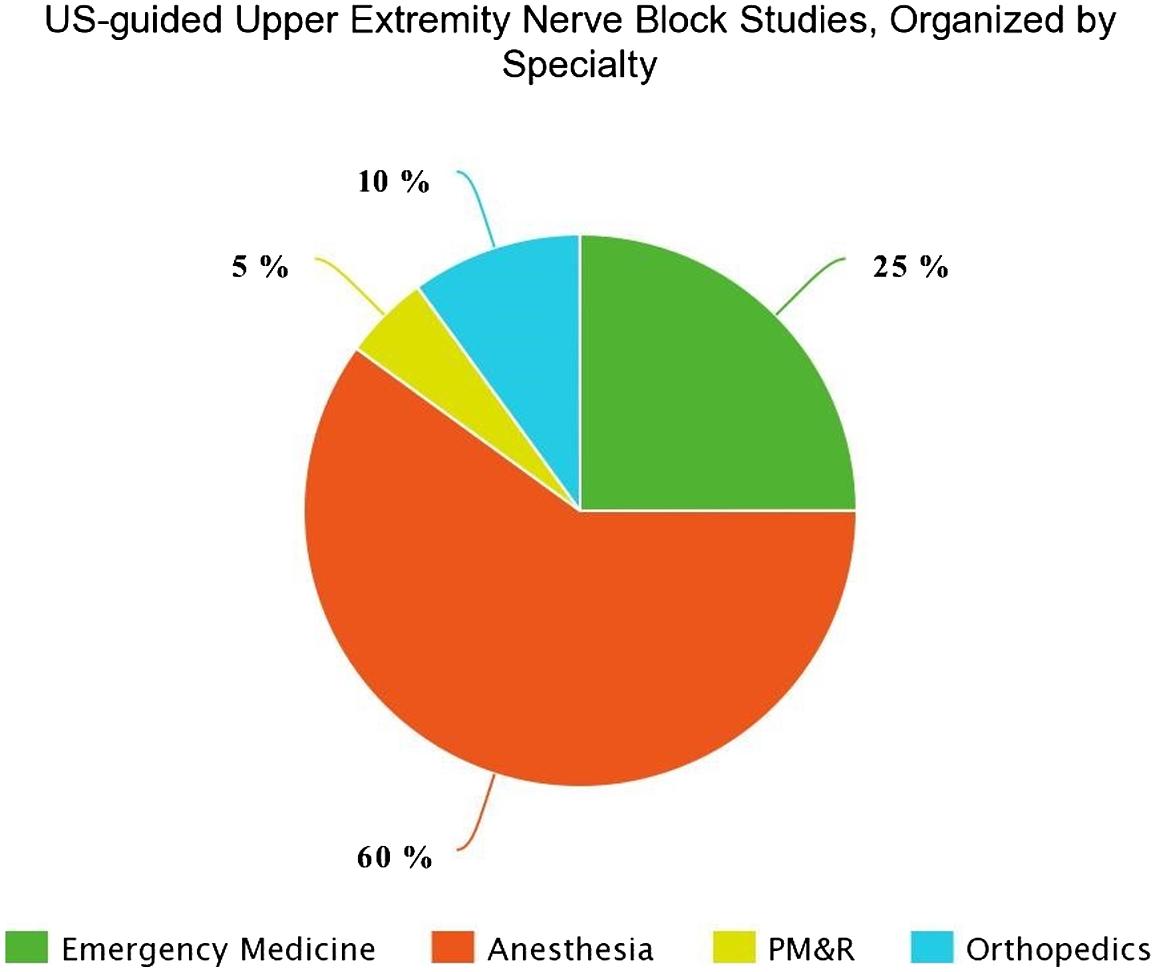

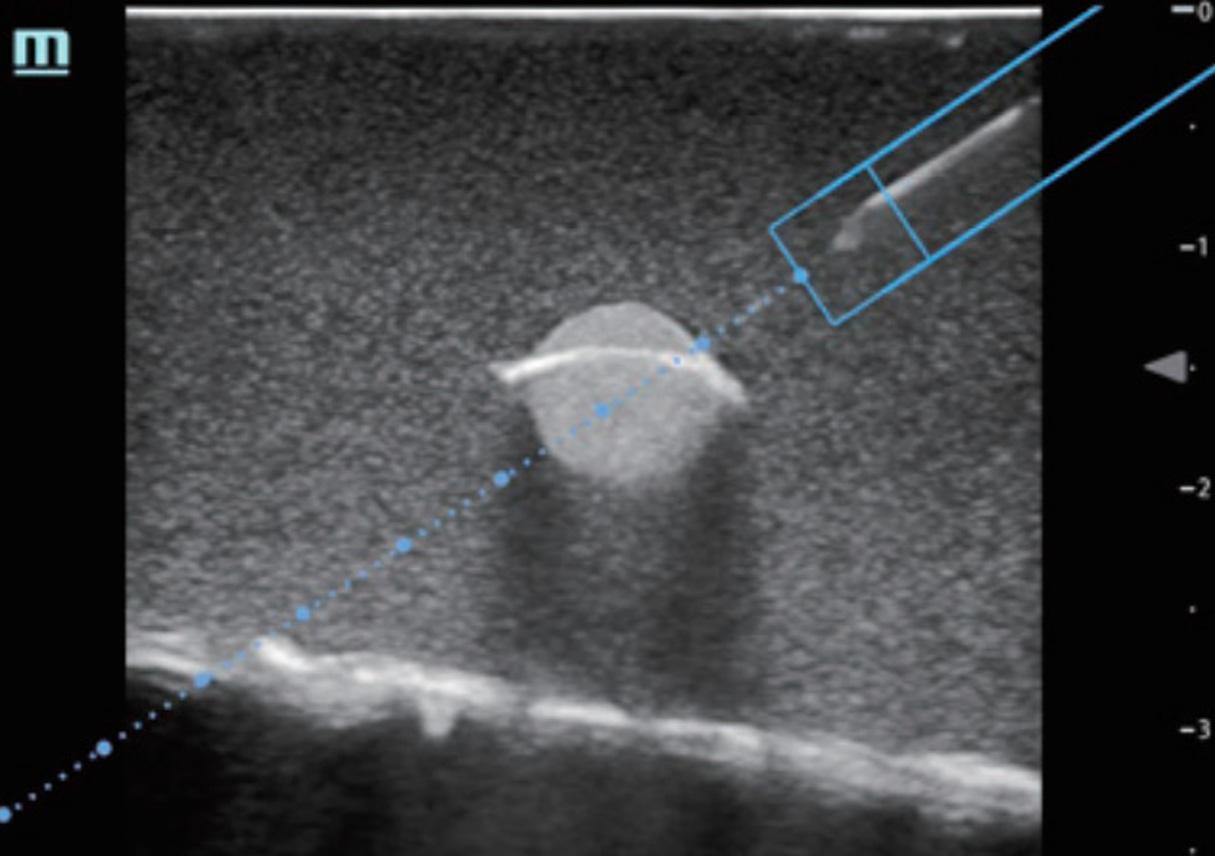

774 Block Time: A Multispecialty Systematic Review of Efficacy and Safety of Ultrasound-guided Upper Extremity Nerve Blocks

Campbell Belisle Haley, Andrew R. Beauchesne, John Christian Fox, Ariana M. Nelson

Policies for peer review, author instructions, conflicts of interest and human and animal subjects protections can be found online at www.westjem.com.

Emergency

Volume 24, No. 4: July 2023 iii Western Journal of

Medicine

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine:

Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

Table of Contents continued

Prehospital Care

786 Community Paramedicine Intervention Reduces Hospital Readmission and Emergency Department Utilization for Patients with Cardiopulmonary Conditions

Aaron Burnett, Sandi Wewerka, Paula Miller, Ann Majerus, John Clark, Landon Crippes, Tia Radant

Clinical Practice

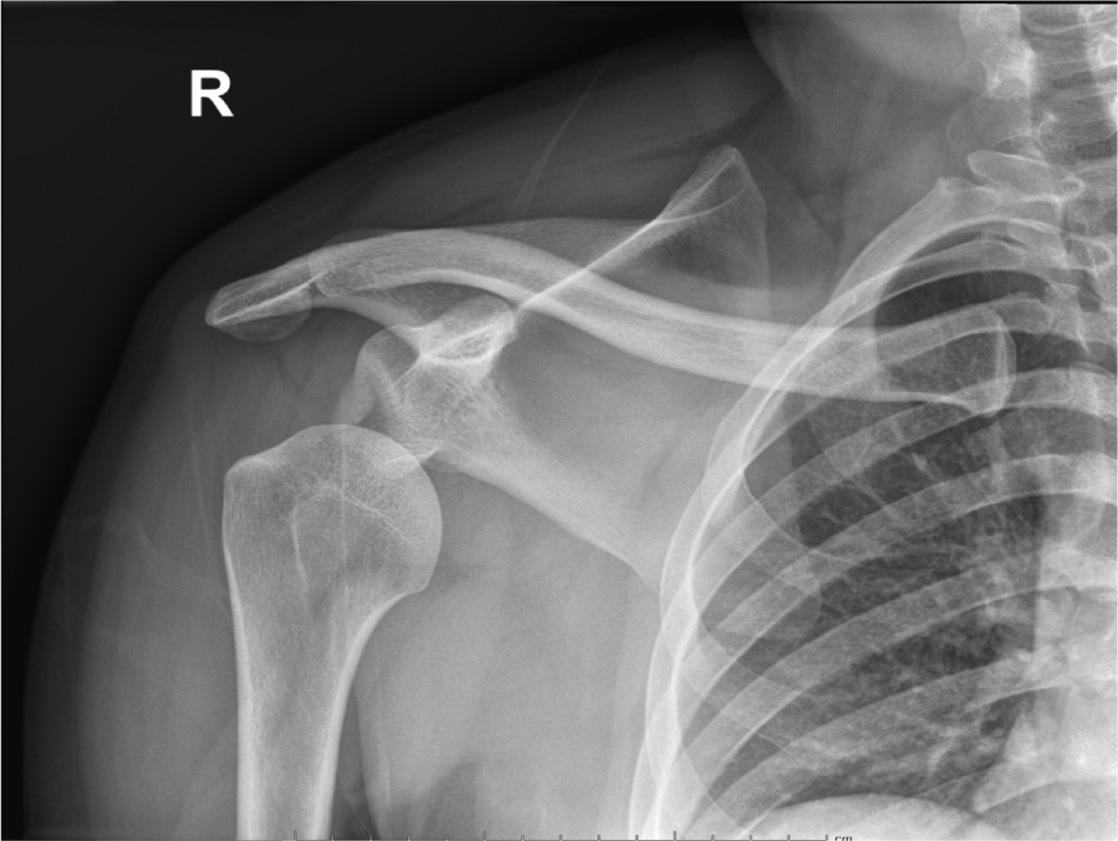

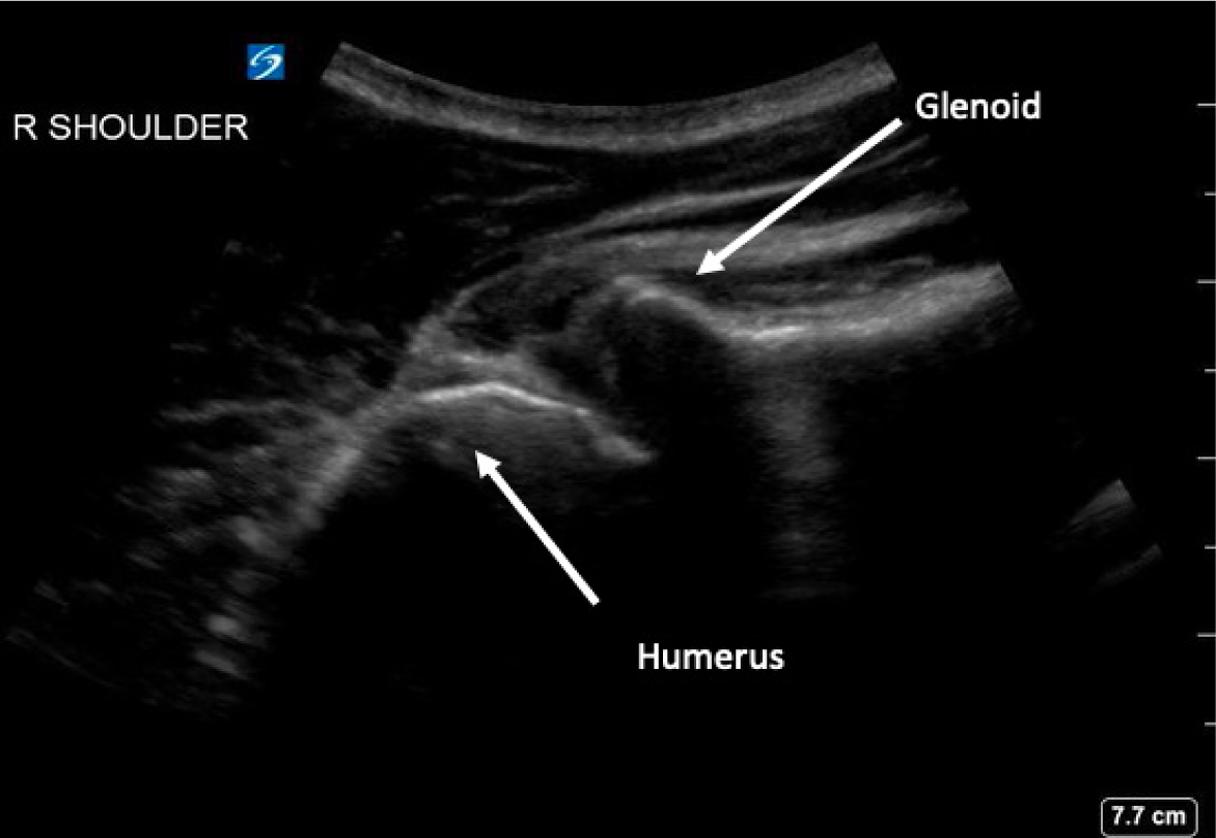

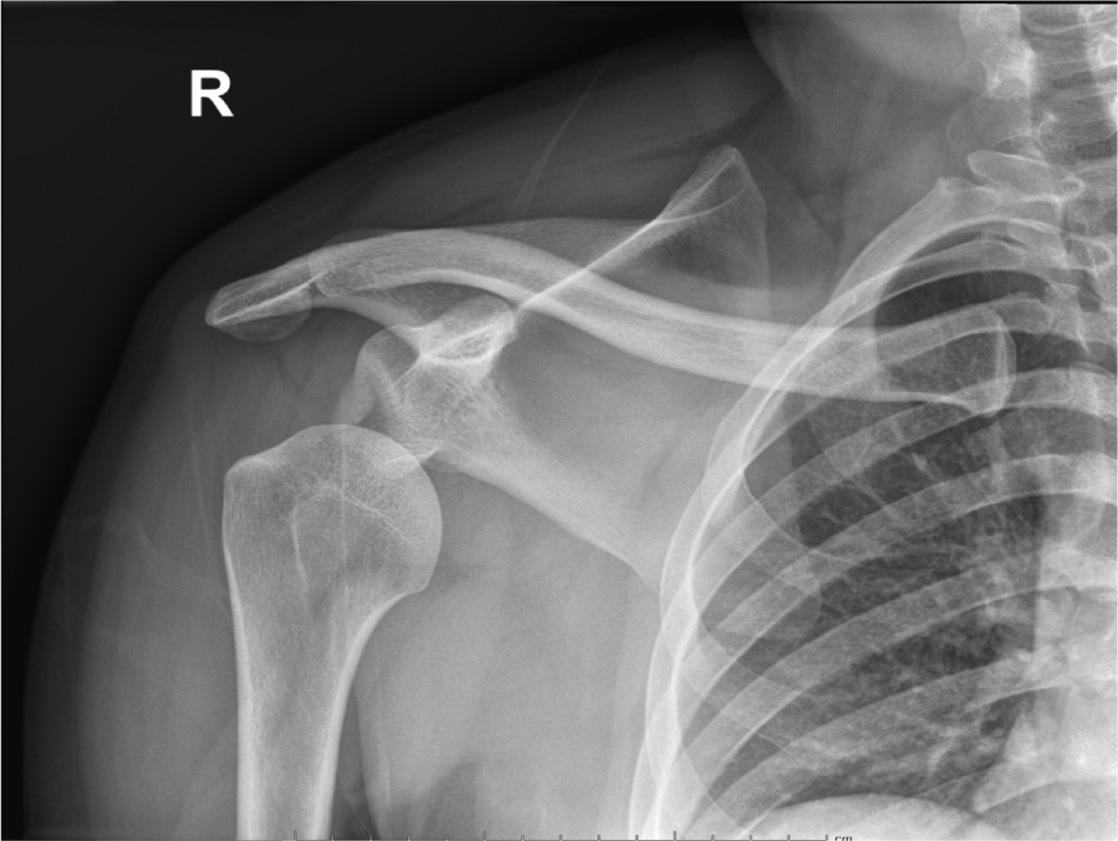

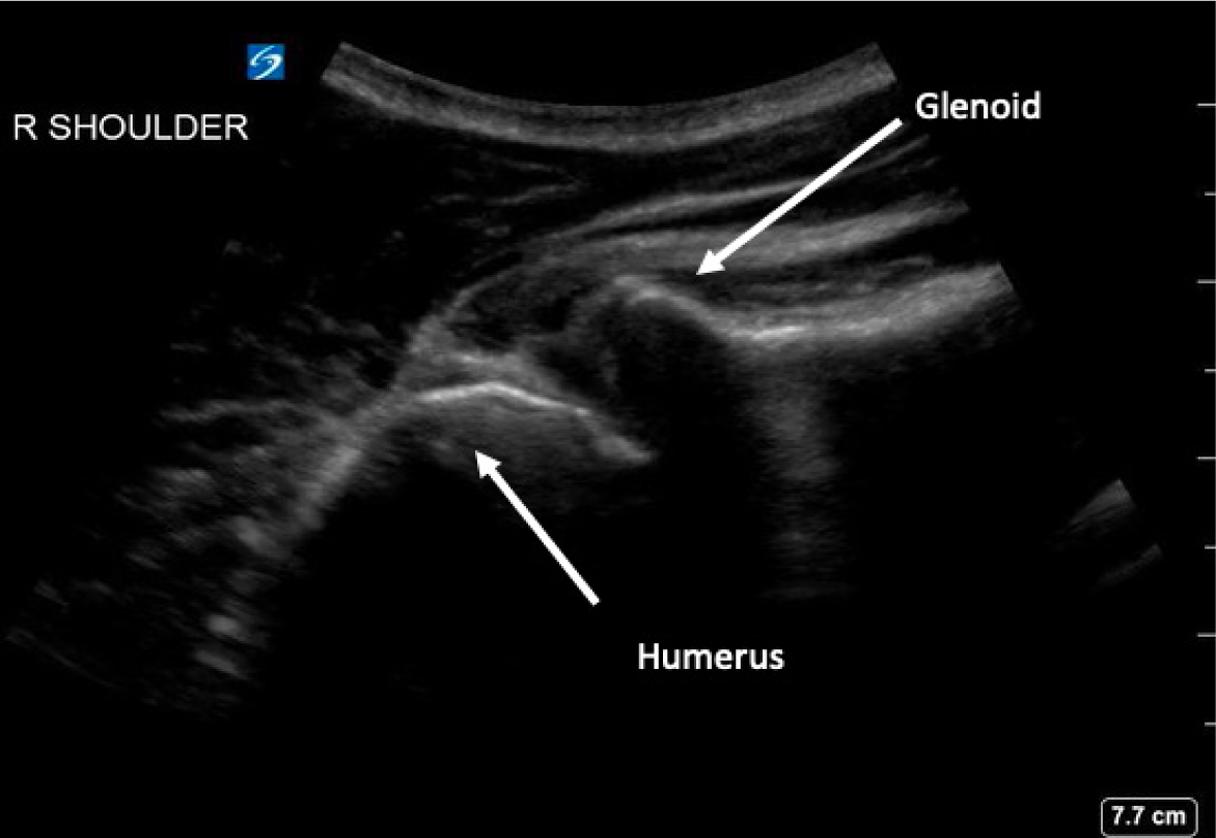

793 Utility of Supraclavicular Brachial Plexus Block for Anterior Shoulder Dislocation: Could It Be Useful?

Michael Shalaby, Melissa Smith, Lam Tran, Robert Farrow

Trauma

798 Haboob Dust Storms and Motor Vehicle Collision-related Trauma in Phoenix, Arizona

Michael B. Henry, Michael Mozer, Jerome J. Rogich, Kyle Farrell, Jonathan W. Sachs, Jordan Selzer, Vatsal Chikani, Gail Bradley, Geoff Comp

Emergency Medical Services

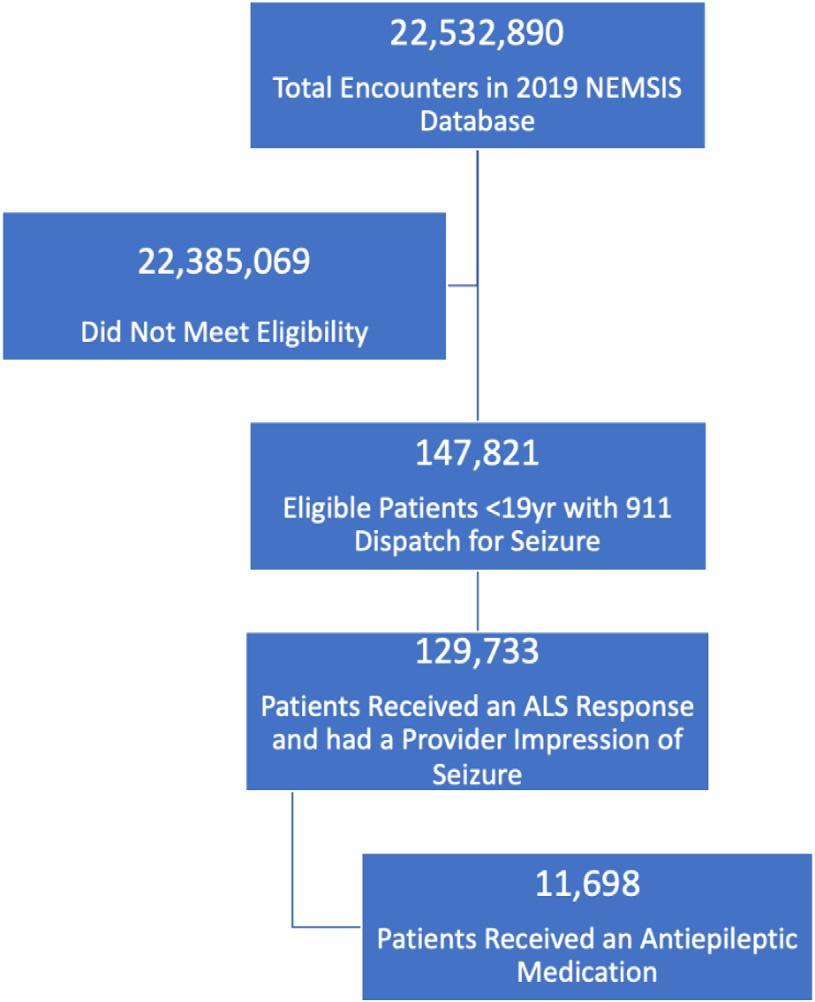

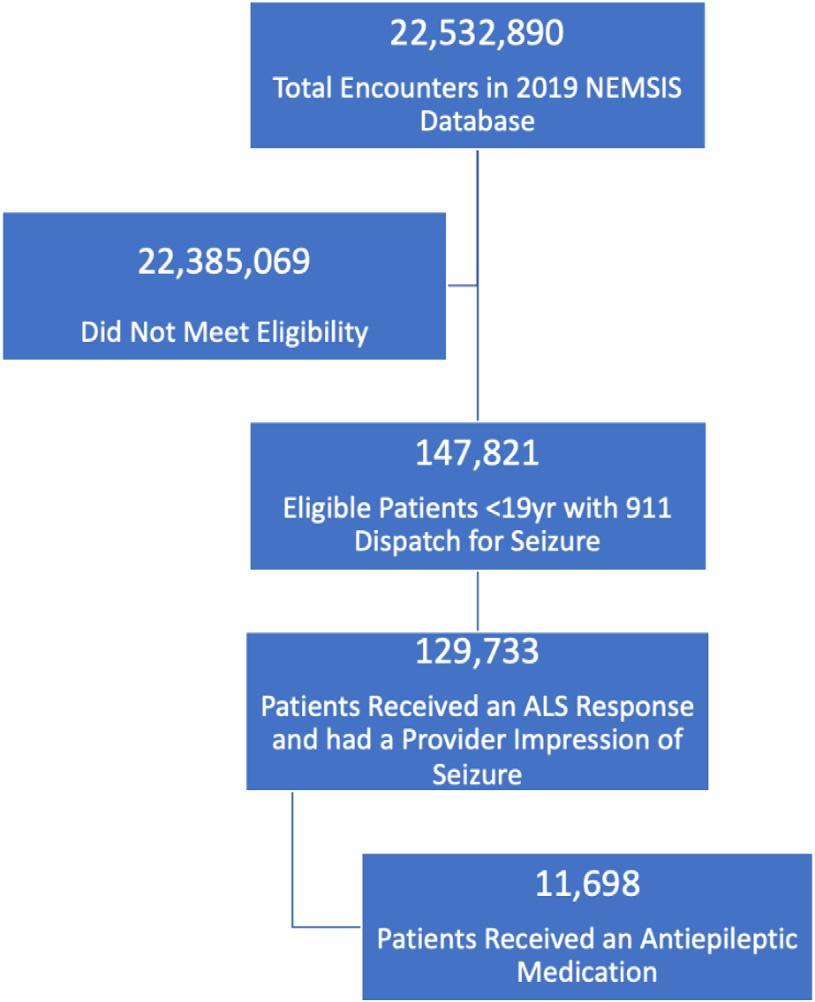

805 National Variation in EMS Response and Antiepileptic Medication Administration for Children with Seizures in the Prehospital Setting

Maytal T. Firnberg, E. Brooke Lerner, Nan Nan, Chang-Xing Ma, Manish I. Shah, N.Clay Mann, Peter S. Dayan

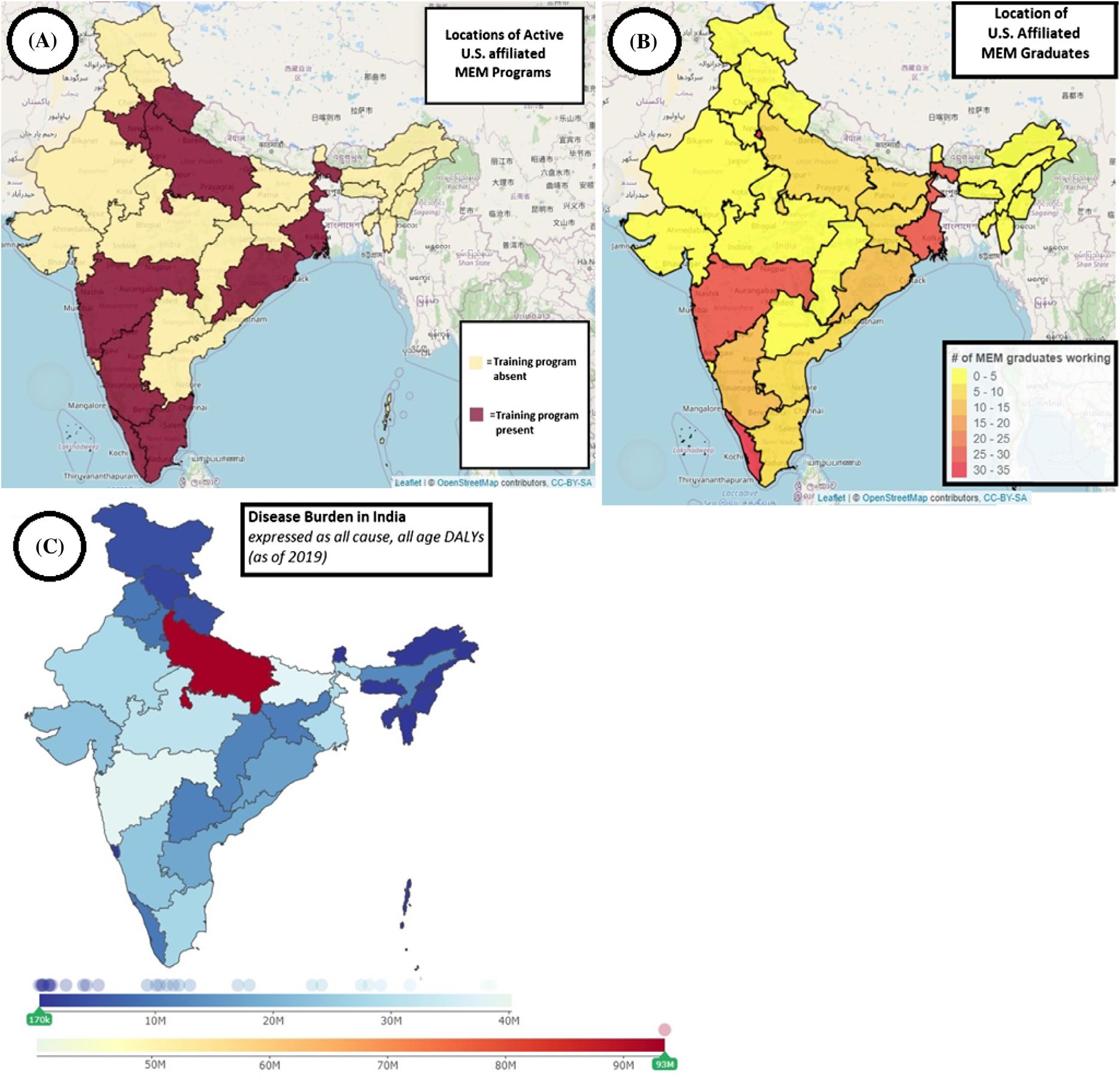

International Emergency Medicine

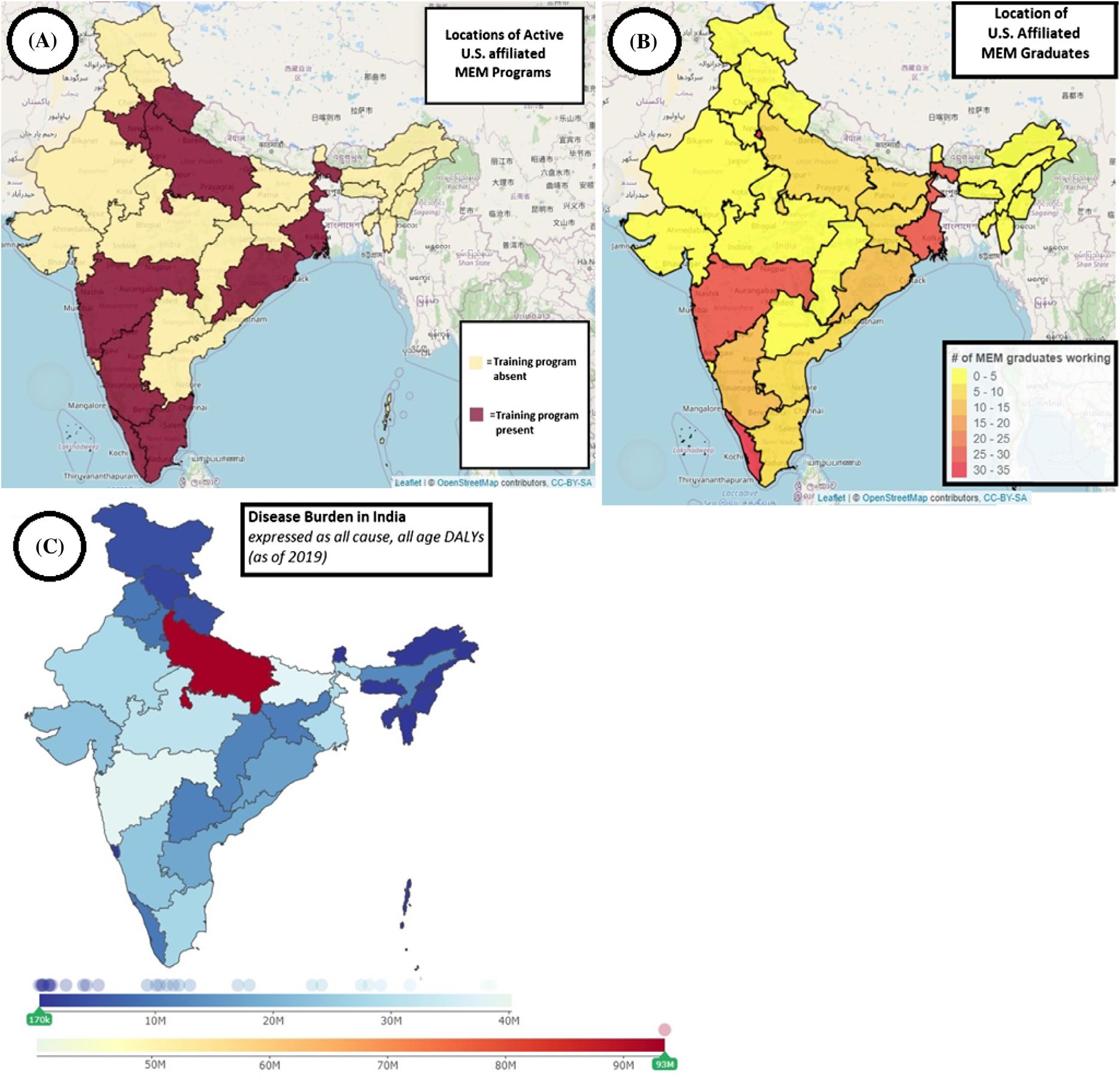

814 Contribution of 15 Years (2007–2022) of Indo-US Training Partnerships to the Emergency Physician Workforce Capacity in India

Joseph D. Ciano, Katherine Douglass, Kevin J. Davey, Shweta Gidwani, Ankur Verma, Sanjay Jaiswal, John Acerra

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine iv Volume 24, No. 4: July 2023

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine:

Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate

This open access publication would not be possible without the generous and continual financial support of our society sponsors, department and chapter subscribers.

Professional Society Sponsors

American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians

California American College of Emergency Physicians

Academic Department of Emergency Medicine Subscriber

Albany Medical College

Albany, NY

Allegheny Health Network

Pittsburgh, PA

American University of Beirut

Beirut, Lebanon

AMITA Health Resurrection Medical Center

Chicago, IL

Arrowhead Regional Medical Center

Colton, CA

Baylor College of Medicine

Houston, TX

Baystate Medical Center Springfield, MA

Bellevue Hospital Center New York, NY

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

Boston, MA

Boston Medical Center

Boston, MA

Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Boston, MA

Brown University Providence, RI

Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center Fort Hood, TX

Cleveland Clinic Cleveland, OH

Columbia University Vagelos New York, NY

State Chapter Subscriber

Arizona Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

California Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Florida Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

International Society Partners

Emergency Medicine Association of Turkey

Lebanese Academy of Emergency Medicine

Conemaugh Memorial Medical Center Johnstown, PA

Crozer-Chester Medical Center Upland, PA

Desert Regional Medical Center Palm Springs, CA

Detroit Medical Center/ Wayne State University Detroit, MI

Eastern Virginia Medical School Norfolk, VA

Einstein Healthcare Network Philadelphia, PA

Eisenhower Medical Center Rancho Mirage, CA

Emory University Atlanta, GA

Franciscan Health Carmel, IN

Geisinger Medical Center Danville, PA

Grand State Medical Center Allendale, MI

Healthpartners Institute/ Regions Hospital Minneapolis, MN

Hennepin County Medical Center Minneapolis, MN

Henry Ford Medical Center Detroit, MI

Henry Ford Wyandotte Hospital Wyandotte, MI

California Chapter Division of American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Mediterranean Academy of Emergency Medicine

INTEGRIS Health

Oklahoma City, OK

Kaiser Permenante Medical Center

San Diego, CA

Kaweah Delta Health Care District

Visalia, CA

Kennedy University Hospitals

Turnersville, NJ

Kent Hospital

Warwick, RI

Kern Medical

Bakersfield, CA

Lakeland HealthCare

St. Joseph, MI

Lehigh Valley Hospital and Health Network

Allentown, PA

Loma Linda University Medical Center

Loma Linda, CA

Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center

New Orleans, LA

Louisiana State University Shreveport

Shereveport, LA

Madigan Army Medical Center

Tacoma, WA

Maimonides Medical Center

Brooklyn, NY

Maine Medical Center

Portland, ME

Massachusetts General Hospital/Brigham and Women’s Hospital/ Harvard Medical

Boston, MA

Great Lakes Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Tennessee Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Norwegian Society for Emergency Medicine

Sociedad Argentina de Emergencias

Mayo Clinic

Jacksonville, FL

Mayo Clinic College of Medicine

Rochester, MN

Mercy Health - Hackley Campus

Muskegon, MI

Merit Health Wesley

Hattiesburg, MS

Midwestern University

Glendale, AZ

Mount Sinai School of Medicine New York, NY

New York University Langone Health

New York, NY

North Shore University Hospital

Manhasset, NY

Northwestern Medical Group

Chicago, IL

NYC Health and Hospitals/ Jacobi New York, NY

Ohio State University Medical Center

Columbus, OH

Ohio Valley Medical Center

Wheeling, WV

Oregon Health and Science University

Portland, OR

Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center

Hershey, PA

Uniformed Services Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Virginia Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Sociedad Chileno Medicina Urgencia

Thai Association for Emergency Medicine

To become a WestJEM departmental sponsor, waive article processing fee, receive electronic copies for all faculty and residents, and free CME and faculty/fellow position advertisement space, please go to http://westjem.com/subscribe or contact:

Stephanie Burmeister

WestJEM Staff Liaison

Phone: 1-800-884-2236

Email: sales@westjem.org

Volume 24, No. 4: July 2023 v Western Journal of

Medicine

Emergency

Web

Index

of Science, Science Citation

Expanded

Indexed

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine:

Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

This open access publication would not be possible without the generous and continual financial support of our society sponsors, department and chapter subscribers.

Professional Society Sponsors

American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians

California American College of Emergency Physicians

Academic Department of Emergency Medicine Subscriber

Prisma Health/ University of South Carolina SOM Greenville Greenville, SC

Regions Hospital Emergency Medicine Residency Program

St. Paul, MN

Rhode Island Hospital

Providence, RI

Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital

New Brunswick, NJ

Rush University Medical Center

Chicago, IL

St. Luke’s University Health Network

Bethlehem, PA

Spectrum Health Lakeland

St. Joseph, MI

Stanford Stanford, CA

SUNY Upstate Medical University

Syracuse, NY

Temple University

Philadelphia, PA

Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center

El Paso, TX

The MetroHealth System/ Case Western Reserve University

Cleveland, OH

UMass Chan Medical School

Worcester, MA

University at Buffalo Program Buffalo, NY

State Chapter Subscriber

Arizona Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

California Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Florida Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

International Society Partners

Emergency Medicine Association of Turkey

Lebanese Academy of Emergency Medicine

University of Alabama Medical Center Northport, AL

University of Alabama, Birmingham

Birmingham, AL

University of Arizona College of Medicine-Tucson

Tucson, AZ

University of California, Davis Medical Center

Sacramento, CA

University of California, Irvine

Orange, CA

University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA

University of California, San Diego

La Jolla, CA

University of California, San Francisco San Francisco, CA

UCSF Fresno Center

Fresno, CA

University of Chicago Chicago, IL

University of Cincinnati Medical Center/ College of Medicine Cincinnati, OH

University of Colorado Denver Denver, CO

University of Florida

Gainesville, FL

University of Florida, Jacksonville Jacksonville, FL

California Chapter Division of American Academy of Emergency Medicine

University of Illinois at Chicago

Chicago, IL

University of Iowa

Iowa City, IA

University of Louisville

Louisville, KY

University of Maryland

Baltimore, MD

University of Massachusetts

Amherst, MA

University of Michigan

Ann Arbor, MI

University of Missouri, Columbia

Columbia, MO

University of North Dakota School of Medicine and Health Sciences

Grand Forks, ND

University of Nebraska Medical Center

Omaha, NE

University of Nevada, Las Vegas

Las Vegas, NV

University of Southern Alabama

Mobile, AL

University of Southern California

Los Angeles, CA

University of Tennessee, Memphis Memphis, TN

University of Texas, Houston Houston, TX

University of Washington

Seattle, WA

Great Lakes Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Tennessee Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Norwegian Society for Emergency Medicine

Sociedad Argentina de Emergencias

University of WashingtonHarborview Medical Center

Seattle, WA

University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics

Madison, WI

UT Southwestern Dallas, TX

Valleywise Health Medical Center

Phoenix, AZ

Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center Richmond, VA

Wake Forest University

Winston-Salem, NC

Wake Technical Community College

Raleigh, NC

Wayne State

Detroit, MI

Wright State University

Dayton, OH

Yale School of Medicine

New Haven, CT

Uniformed Services Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Virginia Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Sociedad Chileno Medicina Urgencia

Thai Association for Emergency Medicine

Mediterranean Academy of Emergency Medicine

To become a WestJEM departmental sponsor, waive article processing fee, receive electronic copies for all faculty and residents, and free CME and faculty/fellow position advertisement space, please go to http://westjem.com/subscribe or contact:

Stephanie Burmeister

WestJEM Staff Liaison

Phone: 1-800-884-2236

Email: sales@westjem.org

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine vi Volume 24, No. 4: July 2023

in MEDLINE,

and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

PubMed,

AddressingEmergencyDepartmentCareforPatients ExperiencingIncarceration:ANarrativeReview

RachelE.Armstrong,MD*

KristopherA.Hendershot,MD*

NaomiP.Newton,MD*

PatriciaD.Panakos,MD†

SectionEditor:TrevorMills,MD,MPH

*UniversityofMiami,Miami,Florida

† JacksonHealthSystem,Miami,Florida

Submissionhistory:SubmittedSeptember30,2022;RevisionreceivedMarch22,2023;AcceptedMarch23,2023

ElectronicallypublishedJune28,2023

Fulltextavailablethroughopenaccessat http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

DOI: 10.5811/westjem.59057

Patientsexperiencingincarcerationfaceamultitudeofhealthcaredisparities.Thesepatientsare disproportionatelyaffectedbyavarietyofchronicmedicalconditions.Patientswhoareincarcerated oftenremainshackledthroughouttheirhospitalcourse,experiencebiasfrommembersofthehealthcare team,andhavemanybarrierstoprivacygiventheomnipresenceofcorrectionsofficers.Despitethis, manyphysiciansreportlittleformaltrainingoncaringforthisuniquepatientpopulation.Inthisnarrative review,weexaminethecurrentliteratureonpatientswhoareincarcerated,especiallyasitpertainsto theircareintheemergencydepartment(ED).Wealsoproposesolutionstoaddressthesebarrierstocare intheEDsetting.[WestJEmergMed.2023;24(4)654–661.]

INTRODUCTION

TheUnitedStateshasover1.6millionincarcerated people.1 Thispopulationhasbeenhistoricallymedically underservedandfacesavarietyofhealthcaredisparities. Individualswhoareincarceratedaremorelikelythanthe generalpopulationtohavemedicalconditionssuchas diabetes,hypertension,HIV,hepatitisC,andtuberculosis.2,3 Theoftensubstandardlivingconditionsinjailsandprisons alsonegativelyimpactincarceratedpatients’ health.For example,themorbidityandmortalityfromCOVID-19was significantlyhigherinprisonsthaninthegeneralpublic.4,5 Whileincarcerationsometimesconnectsindividualswho havenothadpreviousaccesstocarewithcontinuityofcare andmedicationforchronicconditions,manyindividualsare stillunabletoaccessadequatetreatmentwhile incarcerated.6,7 Forexample,cancerpatientsreport inadequateaccesstopainmedications,patientsfacebarriers toacutesurgicalcare,andpregnantpatientsreport inadequateprenatalcare.8,9,10 Evenwhenpatientsareableto accesscarewhileincarcerated,theyoftenfaceimmense barrierstohealthcareoncereleased.2,3

Inadditiontothedisparitiesnotedabove,incarcerationis associatedwithmentalillnessandearlymortality.When comparedtonon-incarceratedpeople,thosewhoare incarceratedhavehigherratesofmajordepression,bipolar

disorder,andschizophrenia.11

16 Furthermore, incarcerationitselfmaypredisposeindividualstomental illness,asexperiencingincarcerationisariskfactorfor developinga firstpsychoticepisode.17 Substanceuse disorders(SUD)aremoreprevalentintheincarcerated populationthanthegeneralpopulation.18 Manycorrectional facilitiesdonotprovideadequatetreatmentforSUD,which canleadtosituationsoflife-threateningwithdrawalin individualswithbenzodiazepineandalcoholuse disorder.19,20 Individualswithopioidusedisorderhavea markedlyincreasedriskofopioidoverdoseafterrelease, especiallyiftheyarenotstartedonmedication-assisted treatmentwhileincarcerated.21

24 Withregardtomortality, studieshaveshownthatpeoplewhohavebeenincarcerated haveanincreasedriskofdeathatayoungeragewhen comparedtothegeneralpopulation.25,26 Thisriskof prematuredeathinincarceratedpeopledisproportionately affectsBlackpopulationswhencomparedtoother demographicgroups.27,28

Itisimpossibletodiscussthedisparitiesfacedby incarceratedpatientswithoutrecognizingthatthecriminal justicesystemisonebasedonracialoppression.29 Black Americansareincarcerated,wrongfullyconvicted,and stoppedandsearchedbypoliceatdisproportionatelyhigher ratesthanWhiteAmericans.30

33 Thehistoryofpolicingis

–

–

–

WesternJournal of EmergencyMedicineVolume24,No.4:July2023 654

SOCIAL EMERGENCY

POPULATION HEALTHAND

MEDICINE

alsorootedinsystemicracism.Inthe18th and19th centuries, groupscalled “slavepatrols” wouldsearchforanddetain enslavedpeoplewhoescaped;thesegroupsareconsidered thebasisof “modern-daypolicing.”34,35 Whenformalpolice departmentswereestablishedintheearly20th century,these organizationsservedalargeroleinenforcingJimCrowlaws (lawsintheSouththatinstitutionalizedracialsegregation, suchasrequiringseparatewaterfountainsforBlackand Whitepeople).34 Inthelate20th century,thesystemic criminalizationofrecreationaldrugusefromPresident RonaldReagan’ s “WaronDrugs” andPresidentBill Clinton’sViolentCrimeControlandLawEnforcementAct disproportionatelytargetedBlackandLatino Americans.36,37 Thesearesomeexamples,butbynomeans anexhaustivelist,ofhowsystemicracismislinkedtothe criminaljusticesystemintheUS.

Whilethisreviewfocusesonpatientswhoare incarcerated,patientspresenttotheemergencydepartment (ED)invarioustypesofcustody.Oftenpatientsarebrought totheEDaftertheyarearrestedbutbeforetheyare convictedofacrimesothatemergentmedicalconcernscan beaddressedpriortobooking.Somepatientsarebroughtin whiledetainedbyUSImmigrationandCustoms

Enforcementofficers.PatientsmayalsopresenttotheED duringthepre-trialperiodorpost-convictionfromjailor prison.Patientsfrombothjailsandprisonsexperience barrierstohealthcare,buttherearegreatdiscrepanciesinthe careprovidedatjails,basedonthevariationinajail’ssize andresourcesandgiventhatpeopletypicallyspendlesstime injailsthaninprisons.6,38,39 Additionally,smallerjailsmay contractoutmostoftheirmedicalservices,andjailsare subjecttolessregulatoryhealthcareoversightthanprisons.39 Whilewewillfocusonthecareofindividualswhoare incarcerated,manyoftheprinciplesoutlinedinthisarticle areapplicabletopatientsinvarioustypesofcustody.

Physiciansemployedbyjailsandprisonsfaceanethical dilemmatermed “dualloyalty,” meaningtheconflictin interestbetweencaringfortheirpatientandcateringto thedemandsoftheprisonadministration.40 Sometimes, physiciansareaskedtoperformtasksthatgoagainsttheir roleashealers,ie,toperformdrugtestswithoutapatient’ s consent,towithholdanexpensivemedicaltreatmentdespite itbeingthestandardofcare,andtoperformmedicalexams forthepurposeof “certify[ing]thatprisonersare fitfor imprisonment.”40 Similarly,emergencyphysiciansmustbe awareoftheconflictsofinterestthatarisewhencaringfor patientswhoareincarcerated,suchascaseswhentheyare askedto “medicallyclear” apatientpriortobookingor performtestsorexamsthatarenotclinicallyindicated.

Penalharmreferstoany “plannedgovernmentalact wherebyacitizenisharmed” forpunitivereasons;theharmis considered “justifiablepreciselybecauseitisanoffenderwho issuffering.”41,42 AlthoughtheEighthAmendmentofthe USConstitutionbroadly “prohibitscruelandunusual

punishment,” itwasnotuntilthe1976SupremeCourt rulinginthecaseof EstellevGamble thatpenalharm inthecontextofmedicalcarewasexplicitlydeemed unconstitutional.43 The EstellevGamble ruling,which centeredon “thedeliberateindifferenceofthemedicalneeds ofprisoners,” setaclearprecedentfortherightsof incarceratedpatientstoaccessiblemedicalcare(including inpatientandspecialistcare).43,44 Failuretoprovide incarceratedpatientswiththesame “standardofcare” as non-incarceratedpatientshashenceforthbeenconsidereda violationoftheEighthAmendment.44 However,inpractice, upholdingthehealthcarerightsofincarceratedpatientsis morechallengingtoenforce.45

Inthisnarrativereview,wewillidentifyseveralbarriersto maintainingthestandardofcareforincarceratedpatientsin theED.Wehopetoincreaseawarenessofthesedisparities andproposesolutionstobetteraddresstheminclinical practice.34,46

BARRIERSTOCARE

Throughourreviewoftheexistingliterature,weidentified multiplebarrierstotreatingincarceratedpatientsintheED: biasedcarefromphysicians;presenceoflawenforcement; anduseofphysicalrestraints.

Bias

Membersofthehealthcareteam,includingphysiciansand nurses,oftenhavetheirownpreconceivednotionsabout incarceratedpatientsthatultimatelyaffectpatientcare.A surveystudyofformerlyincarceratedindividualsfoundthat manypatientshaveexperienceddiscriminationbasedon theircriminalrecord.47 Manypatientsalsoreported discriminationinthehealthcaresettingduetotheirraceand ethnicity.47 Thissurveystudyalsofoundthatformerly incarceratedindividualswithincreasedEDutilization reportedahigherrateofdiscriminationfromhealthcare professionals.47

However,manyphysiciansalreadyrecognizethe disparitiesinthecareofpatientswhoareincarcerated.One recentqualitativestudybyDouglasetalacknowledgesthe needtooptimizequalityofcareforincarceratedpatients.48 Inthispaper,surgicalresidentsweresurveyedabouttheir encounterswithlawenforcementwhilecaringforpatients experiencingincarceration.Thesurgicalresidentsnoted manychallengeswhencaringforthesepatients,including barrierstoadequatefollow-upcareandthedesignated holdingareasforincarceratedpatientsthatmaycontribute to “substandardcare” ordecreasedmonitoringofcritically illpatients.48

Biashasbeenreportedamongmanymembersofthe healthcareteam.Thestudy “CaringforHospitalized IncarceratedPatients:PhysicianandNurseExperience” by Brooksetalexaminedphysicianandnurseexperienceswhen caringforhospitalizedincarceratedpatientsusingopenand

Volume24,No.4:July2023WesternJournal of EmergencyMedicine 655 Armstrongetal. AddressingEDCareforPatientsExperiencingIncarceration

closed-endedsurveyquestions.49 Amajorityofphysicians believedpatientswhowereincarceratedreceivedless frequentnon-medicalinterventions(definedas “socialwork support,physicaltherapyvisits,nutritionconsults”)during hospitalizationthanotherpatients.49 Over30%ofphysicians believedthatthesepatientsreceived “fewerdiagnostictests” and “fewermedicalinterventions” thanotherpatients.49

PatientPrivacy

Therearealsomanylimitstopatientprivacywhencaring forpatientswhoareincarceratedintheED.Thepresenceof correctionsofficerswhoaccompanythesepatientstotheED oftenleadstoprotectedhealthinformation(PHI)being sharedifmembersofthehealthcareteamdonotaskofficers tostepawayduringthehistoryandphysical.43,50

InthesurveystudybyBrooksetal,ahigherpercentageof nurseswhencomparedtophysiciansreportedthattheykept lawenforcementintheexamroomswhenperformingtheir historiesandphysicals.49 Still,35%ofphysiciansreported notaskingcorrectionsofficerstoleaveduringpatient encounters,andover50%ofthephysiciansreportednot askingforshacklestoberemovedduringtheirhistoriesand physicals.49 Inthesurvey,physiciansalsoidentifiedalackof formaltrainingintheirmedicaleducationwhencaringfor thisgroupofpatients.49

ManysurgicalresidentsintheDouglasetalstudy recognizedincarceratedpatients’ barrierstoprivacy.The majorityofresidentsinthisstudyreportedwitnessing incidentswhenlawenforcementofficerswouldquestion patientsduringtraumaassessments,attimesdisruptingthe primaryandsecondarysurveyandimpingingonpatient privacy.48 Inaddition,manyresidentsreportedinstances whenan “armedguardwaspresentintheoperatingroom” duringasurgicalprocedure.48 Oneresidentreportedan instancewhenanofficerrequestedanethanollevelona patient,eventhoughthistestwasnotpertinenttothe patient’scareatthattime.48

Theliteraturealsodescribesinstanceswhenlaw enforcement,namelypoliceofficers,haverequestedinvasive bodysearchesandtestsonpatients,althoughthesetestswere notclinicallyindicated.51,52 Inasurveystudy,emergency physiciansreportedbreachesofpatientprivacyinthe presenceoflawenforcement,includinginstanceswhen officerssolicitedPHI.53 Physiciansreportedbeinguncertain oftheexactroleandlimitationsoflawenforcementintheir workplace.53

Whilephysiciansshouldalwaysstrivetomaintainpatient privacy,therearecircumstancesinwhichaspectsofpatient caremayneedtobedisclosedtolawenforcement.For example,PHImayneedtobedisclosedifapatientrequires specifictreatmentorfollow-upcareintheoutpatientsetting. Giventhedelaysthatcanoccurinthecareofincarcerated patients,instructionsmayneedtobeexplicitlywrittenor discussedwithlawenforcementtoensureappropriatecare

occursafterdischargefromtheED.54 However,physicians shouldalwaysattempttoobtainapprovalfrompatientsprior tosharingtheirPHI.Therearealsoinstanceswhere incarceratedpatientsmayexhibitviolentbehaviorthatposes asafetythreattothemselvesortoEDstaff.Inthese instances,itisappropriatetointerviewpatientsinthe presenceoflawenforcement.

PhysicalRestraints

Physiciansaretaughttousephysicalrestraintswithcaution andonlywhenabsolutelynecessary.Physicalhospital restraints,whichareoftenappliedtoprotectpatientsafety,are associatedwithnumerouscomplications.Forexample,there isastatisticallysignificantincreasedincidenceofpulmonary embolismanddeepveinthrombosisinpatientswhoare physicallyrestrained.55,56 Furthermore,restraintsare associatedwithdelirium,emotionaldistress,rhabdomyolysis, injury,andevendeathwhenimproperlyused.57–59 Indeed, boththeAmericanCollegeofEmergencyPhysicians(ACEP) andTheJointCommissionhavepublishedstandardsonthe criterianecessarytojustifyrestraintuseandminimizeharm associatedwithrestraints.59–61

Despitethecautionadvisedwhenusingphysicalrestraints, patientswhoareincarceratedoftenarrivetotheEDin shacklesandremaininshacklesthroughoutthecourseoftheir EDstay.Somesurgeryresidentshaveevenreportedcaringfor patientswhoareshackledtothebedwhileintubatedand sedated.48 Therearesomepoliciesinplacetolimittheuseof shacklesinclinicalsettings.Recognizingtherisksofphysical restraintsinpregnancy,manystateshavemandatedagainst physicalrestraintsforpatientswhoareincarceratedinthe perinatalperiod.62 Federalpolicieshavealsobeenenactedto restrictuseofphysicalrestraintsinpregnancy,exceptwhen considerednecessaryforsafetyreasons.62

Thereisadearthofprotectionsforpatientswhoarenot pregnant.Non-pregnant,incarceratedpatientsoftenremain shackledthroughouttheirhospitalstay;thisincludesthose whoareterminallyillandthosewhoareintubatedand sedated.63–65 Thereislittledatatosupportthemedical rationaleforshacklingand,indeed,itsuseismainly determinedbyfederalandlocalpolicytobearequirement duringtransport.63,64,66–68 Adiscussiononwaystoaddress shacklingintheEDisincludedbelow.

STRATEGIESTOIMPROVECARE

Inthissection,weproposeseveralstrategiestoimprove thequalityofEDcareforpatientswhoareincarcerated. Thesesuggestionsarenotexhaustive;muchmoreresearchis requiredtofurtherinvestigatethemanydisparitiesthese patientsface.

Bias

HofmeisterandSoprychdiscusstheimportanceof includingformalteachingontreatingincarceratedpatientsin

WesternJournal of EmergencyMedicineVolume24,No.4:July2023 656 AddressingEDCareforPatientsExperiencingIncarceration Armstrongetal.

medicalcurricula.69 Theauthorsdiscusshowtheuseof workshopsonimplicitbiasescanbeincorporatedinto residentmedicaleducation.Theworkshoptheyperformed allowedresidentphysicianstoself-reflectontheirbiases andbetterrecognizethedisparitiesthatspecificallyaffect incarceratedpatients.69 Thereshouldbeincreased curriculumdevelopmentinmedicaleducationthat focusesonaddressingthebiasesfacedbypatientswho areincarcerated.

Privacy

TheUSDepartmentofHealthandHumanServices outlinesPHIprotectionsforpatientswhoareincarcerated. SharingofPHIisonlypermittedinafewdistinct circumstances,suchaswhenhealthcarecliniciansare respondingtoarequestfor “PHI[that]isneededtoprovide healthcare” tothepatient,orwhenthePHIisnecessaryto protectthehealth/safetyoftheindividualorpeoplearound them.70 Asonecanimagine,informationmaybe inadvertentlydivulgedtocorrectionsofficersiftheemergency physician(EP),nursepractitioner(NP),orphysicianassistant (PA)conductsthehistoryandphysicalwithcorrections officersintheroom.43 Atoolkitforprotectingpatientprivacy createdbytheWorkingGrouponPolicingandPatientRights oftheGeorgetownUniversityHealthJusticeAlliance recommendsthatEPs,NPs,andPAsaskofficerstostepoutof “earshot” toprotectPHIand “preventaccidental disclosures.”50 EPs,NPs,andPAsshouldalsoobtainpatient consentpriortolabtestsandprocedures.50 The “Medical ProviderToolkit” andACEPalsonotethatwhilelaw enforcementpersonnelmayevenprovidewarrantsforspecific testsandexamssuchasbodycavitysearches,EPs,NPs,and PAscanrefuseiftheyarenotclinicallyindicatedorarenotin thepatient’sbestinterest.50,71

PhysicalRestraints

Justascertainfederalandstatepoliciesadvocatefor limitingshackleuseinpregnantpatients,sotooshouldthere beagreateremphasisplacedontheremovalofshackleson patientswhoarenotpregnant.Wheninterviewed,many physiciansandnursesreportednotrequestingthatshackles beremoved.49 Asmentionedabove,thereislittledatato supporttheuseofshackles,andmanyoftherulesand regulationsregardingshackleusefocusontransportation. Barrierstoshackleremovalareoftenduetoknowledge deficitsandunclearinstitutionalguidelinessurrounding shackling.EPs,NPs,andPAsshouldrecognizetheharms associatedwithshacklesandrequesttheirremovalwhenever possible,astheseareoftennotmedicallynecessary.50,64

Indeed,theInternationalAssociationforHealthcare Security&Safetystatesthatitistheresponsibilityofthe physicianandothermembersofthehealthcareteamto “assessthesafetyofcontinueduseofrestraint.”72 In addition,itisthedutyofthecorrectionsofficers,andnotthe

medicalteam,toensurethepatient’ssecurity.64 Giventhat thereareoftenunclearguidelinessurroundingshacklesand non-medicalrestraints,hospitalsshouldalsosetforththeir ownguidelinestoupholdtheprincipleofmedicalnonmaleficenceinalltreatmentareasincludingtheED.64

Tominimizeharm,physiciansshouldavoidandadvocate againsttheshacklingofpatientsintheproneposition.This typeofrestraintconfersanevengreaterriskofcomplications andhasbeenlinkedtocardiopulmonaryarrest,especiallyin agitatedpatients.73 Controversyremainsastowhetherthisis secondarytopositionalasphyxia;Steinbergprovideda reviewofthecurrentliteraturedetailinghowthecauseof suddendeathinpronerestraintis “multifactorial,” resulting from “reducedcardiacoutput,” metabolicacidosis,and impairedventilation.73 WhiletheJointCommissiondoesnot explicitlyprohibitpronerestraint,hospitalsarerequiredto reportanydeathsthatoccurwhileapatientisrestrained.74,75 Sincepronerestrainthasbeenidentifiedasacontributorto deathinsubjectswhoareagitated,manyinstitutionshave createdpoliciesagainstitsuse.76,77

Advocacy

WeencourageEPstoadvocateforchangeinthecarceral systemandintheirowninstitutionstoimprovethe healthcareofpatientswhoareincarcerated.Issuesof inadequatelivingconditionsinprisons,prisoncrowding,and discriminationoutsidethehospitalhavebeenwell documented.78–81 Giventhehealthimplicationsofthese issues,physiciansshouldrecognizeandadvocateforbetter livingsituationsforthesevulnerablepatients.82 Conditions forpatientswhoareincarceratedaresometimesinadequate inthehospital.SomehospitalEDshaveseparateholding areasforpatientswhoareincarcerated.Thequalityofcarein theseEDholdingareascouldbeimprovedbyincreasingthe staffing,resources,andattentiontothesesections.48 Physiciansshouldadvocateforbetterconditionsfor incarceratedpatients,bothwithintheEDandwithout.

ContinuityofCare

Inadditiontothereportedsubstandardcarethat incarceratedpatientsreceivewhileinthehospitalsetting, therearemanybarrierstoappropriatemedicalcarein correctionalfacilities.Thearticle “EmergencyMedicalCare ofIncarceratedPatients:OpportunitiesforImprovement andCostSavings” byMartinetalisachartreviewof incarceratedpatients’ EDvisitsatasingleinstitution.54 Patientsreportedbarrierstocare,suchasdifficultyaccessing prescriptionmedicationsforchronicconditions.54 Inlightof this,EPs,NPs,andPAsshouldaskpatientswhoare incarceratedabouttheiraccesstomedicationsforchronic conditionsandrefillappropriateprescriptionspriorto discharge.Inaddition,therearemanydocumentedcasesof patientseventuallypresentingtothemedicalsystemwith late-stageillnessesthatcouldhavebeentreatedearlierifthey

Volume24,No.4:July2023WesternJournal of EmergencyMedicine 657 Armstrongetal. AddressingEDCareforPatientsExperiencingIncarceration

hadbeenpreviouslyidentified.79 WeencourageEPs,NPs, andPAstoreferpatientstospecialistsandrecommendclinic visitswhenappropriate.79

Education

Thereisalackofformaleducationsurroundingcarefor incarceratedpatients.Inadditiontobiasworkshops, theimplementationoflectures,case-baseddiscussions,and simulationcasescanprovideresidents,attendingphysicians, NPs,andPAswiththetoolsnecessarytocareforthisunique patientpopulation.Wedevelopedandsuccessfully implementedasimulationcaseforresidentlearnersinvolving thepresentationofapatientexperiencingincarceration. Thissimulationaimedtoexposelearnerstotheissuesunique toincarceratedpatientsaswellaspromotediscussiononthe removalofshacklesduringEDcare,implicitbiases,and protectingPHI.Weareintheprocessofanalyzingsurveydata fromthissimulationsession,andresultsareforthcoming.

CONCLUSION

Incarceratedpatientsarepartofavulnerablepopulation thatcurrentlyreceivessubstandardcareinmanyhealthcare settings,includingEDs.Thebiasesheldbymembersofthe healthcareteam,thepresenceofcorrectionsofficers,and pervasiveuseofrestraintscontributetothenumerous healthcareinequities.Wehaveproposedstrategiesto improvethequalityofcareforthisgroupofpatients, recognizingthatchangesmustbemadeonthephysician level,throughoutmedicaleducation,andinstitutionally.

“ Medicineshouldbeviewedassocialjusticeworkinaworld thatissosickandsorivenbyinequities. ” 83 – Dr.PaulFarmer.

AddressforCorrespondence:RachelE.Armstrong,MD,University ofMiami,DepartmentofEmergencyMedicine,1611NW12thAve# ECC1135Miami,FL33136.Email: rxa1022@miami.edu

ConflictsofInterest:Bythe WestJEMarticlesubmissionagreement, allauthorsarerequiredtodiscloseallaffiliations,fundingsources and financialormanagementrelationshipsthatcouldbeperceived aspotentialsourcesofbias.Noauthorhasprofessionalor financial relationshipswithanycompaniesthatarerelevanttothisstudy. Therearenoconflictsofinterestorsourcesoffundingtodeclare.

Copyright:©2023Armstrongetal.Thisisanopenaccessarticle distributedinaccordancewiththetermsoftheCreativeCommons Attribution(CCBY4.0)License.See: http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/

REFERENCES

1.Highesttolowest-prisonpopulationtotal[Internet].HighesttoLowestPrisonPopulationTotal|WorldPrisonBrief.Availableat: https://www. prisonstudies.org/highest-to-lowest/prison-population-total AccessedMarch22,2023.

2.DumontDM,BrockmannB,DickmanS,etal.Publichealthand theepidemicofincarceration. AnnuRevPublicHealth 2012;33:325–39.

3.RichJD,BeckwithCG,MacmaduA,etal.Clinicalcareofincarcerated peoplewithHIV,viralhepatitis,ortuberculosis. Lancet 2016;388(10049):1103–14.

4.MarquezN,WardJA,ParishK,etal.COVID-19incidenceandmortality infederalandstateprisonscomparedwiththeUSpopulation,April5, 2020,toApril3,2021. JAMA. 2021;326(18):1865–7.

5.SalonerB,ParishK,WardJA,etal.COVID-19casesanddeathsin federalandstateprisons. JAMA.2020;324(6):602–603.

6.PuglisiLB,WangEA.Healthcareforpeoplewhoareincarcerated. Nat RevDisPrimers.2021;7(1):1–2.

7.CommitteeonCausesandConsequencesofHighRatesof Incarceration;CommitteeonLawandJustice;DivisionofBehavioral andSocialSciencesandEducation;NationalResearchCouncil;Board ontheHealthofSelectPopulations;InstituteofMedicine. Healthand Incarceration:AWorkshopSummary.Washington(DC):National AcademiesPress(US);2013Aug8.1,ImpactofIncarcerationon Health.Availableat: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK201966/

8.LinJT,MathewP.Cancerpainmanagementinprisons:asurveyof primarycarepractitionersandinmates. JPainSymptomManag 2005;29(5):466–73.

9.BuskoA,Soe-LinH,BarberC,etal.Postmortemincidenceofacute surgical-andtrauma-associatedpathologicconditionsinprisoninmates inMiamiDadeCounty,Florida. JAMASurg.2019;154(1):87

8.

10.WangL.ChronicPunishment:Theunmethealthneedsofpeopleinstate prisons.PrisonPolicyInitiative.PublishedJune2022.Availableat: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/chronicpunishment.html AccessedSeptember30,2022.

11.HirschtrittME,BinderRL.Interruptingthementalillness–incarcerationrecidivismcycle. JAMA.2017;317(7):695–696.

12.BaillargeonJ,BinswangerIA,PennJV,etal.Psychiatricdisordersand repeatincarcerations:therevolvingprisondoor. AmJPsychiatry 2009;166(1):103–9.

13.FovetT,GeoffroyPA,VaivaG,etal.Individualswithbipolardisorder andtheirrelationshipwiththecriminaljusticesystem:acriticalreview. PsychiatrServ.2015;66(4):348–53.

14.MulveyEP,SchubertCA.Mentallyillindividualsinjailsandprisons. CrimeandJustice.2017;46(1):231–77.

15.BronsonJ,BerzofskyM.Indicatorsofmentalhealthproblemsreported byprisonersandjailinmates,2011–12. BurJusticeStatSpecRep. 2017(SpecialIssue):1–6.

16.Mentalillness,humanrights,andUSprisons.HumanRights Watch.Published2020.Availableat: https://www.hrw.org/news/ 2009/09/22/mental-illness-human-rights-and-us-prisons AccessedMarch24,2023.

17.RamsayCE,GouldingSM,BroussardB,etal.Prevalenceand psychosocialcorrelatesofpriorincarcerationsinanurban, predominantlyAfrican-Americansampleofhospitalizedpatientswith first-episodepsychosis. JAmAcadPsychiatryLaw.2011;39(1):57–64.

–

WesternJournal of EmergencyMedicineVolume24,No.4:July2023 658 AddressingEDCareforPatientsExperiencingIncarceration Armstrongetal.

18.FazelS,YoonIA,HayesAJ.Substanceusedisordersinprisoners:an updatedsystematicreviewandmeta-regressionanalysis inrecentlyincarceratedmenandwomen. Addiction 2017;112(10):1725–39.

19.FiscellaK,PlessN,MeldrumS,etal.Alcoholandopiatewithdrawalin USjails. AmJPublicHealth.2004;94(9):1522–4.

20.FiscellaK,NoonanM,LeonardSH,etal.Drug-andalcohol-associated deathsinUSJails. JCorrectHealthCare.2020;26(2):183–93.

21.MerrallEL,KariminiaA,BinswangerIA,etal.Meta-analysisof drug-relateddeathssoonafterreleasefromprison. Addiction 2010;105(9):1545

54.

22.MaltaM,VaratharajanT,RussellC,etal.Opioid-relatedtreatment, interventions,andoutcomesamongincarceratedpersons:asystematic review. PLoSmedicine.2019;16(12):e1003002.

23.Overdosedeathsandjailincarceration-nationaltrendsandracial VeraInstituteofJustice.Availableat: https://www.vera.org/publications/ overdose-deaths-and-jail-incarceration/national-trends-and-racialdisparities.AccessedMarch17,2023.

24.Howisopioidusedisordertreatedinthecriminaljusticesystem? NationalInstituteonDrugAbusewebsite.2021.Availableat: https:// nida.nih.gov/publications/research-reports/medications-to-treat-opioidaddiction/how-opioid-use-disorder-treated-in-criminal-justice-system AccessedMarch21,2023.

25.WitteveenD.Prematuredeathriskfromyoungadulthoodincarceration. SociolQ.2021:1–28.

26.RuchDA,SteelesmithDL,BrockG,etal.Mortalityandcauseofdeath amongyouthspreviouslyincarceratedinthejuvenilelegalsystem. JAMANetwOpen.2021;4(12):e2140352.

27.SykesBL,ChavezE,StrongJ.Massincarcerationandinmatemortality intheUnitedStates deathbydesign? JAMANetwOpen. 2021;4(12):e2140349.

28.Bovell-AmmonBJ,XuanZ,Paasche-OrlowMK,etal.Associationof incarcerationwithmortalitybyracefromanationallongitudinalcohort study. JAMANetwOpen.2021;4(12):e2133083.

29.BrewerRM,HeitzegNA.Theracializationofcrimeandpunishment: criminaljustice,color-blindracism,andthepoliticaleconomyofthe prisonindustrialcomplex. AmBehavSci.2008;51(5):625–44.

30.GelbartC.Studyshowsraceissubstantialfactorin wrongfulconvictions.EqualJusticeInitiative.2022.Availableat: https:// eji.org/news/study-shows-race-is-substantial-factor-in-wrongfulconvictions/.AccessedMarch17,2023.

31.Racialandethnicdisparitiesinthecriminaljusticesystem.National ConferenceofStateLegislatures.UpdatedMay2022.Availableat: https://www.ncsl.org/civil-and-criminal-justice/racial-and-ethnicdisparities-in-the-criminal-justice-system.AccessedMarch17,2023.

32.PiersonE,SimoiuC,OvergoorJ,etal.Alarge-scaleanalysisofracial disparitiesinpolicestopsacrosstheUnitedStates. NatHumBehav 2020;4(7):736–45.

33.LofstromM,HayesJ,MartinB,etal.Racialdisparitiesinlaw enforcementstops.PublicPolicyInstituteofCalifornia.2021.

Availableat: https://www.ppic.org/publication/racial-disparitiesin-law-enforcement-stops/.AccessedMarch21,2023.

34.Theoriginsofmoderndaypolicing.NAACP.Availableat: https://naacp. org/find-resources/history-explained/origins-modern-day-policing AccessedMarch17,2023.

35.BrucatoB.Policingraceandracingpolice:theoriginofUSPolicein slavepatrols. SocialJustice. 2020;47(3/4(161/162)), 115–136.

36.CummingsAD,RamirezSA.Theracistrootsofthewarondrugs andthemythofequalprotectionforpeopleofcolor. UALRLRev 2021;44:453.

37.LevinsH.TheWaronDrugsasstructuralracism.Universityof PennsylvaniaLeonardDavisInstituteofHealthEconomics.2021. Availableat: https://ldi.upenn.edu/our-work/research-updates/the-waron-drugs-as-structural-racism/.AccessedMarch21,2023.

38.GatesA,ArtigaS,RudowitzR.Healthcoverageandcarefortheadult criminaljustice-involvedpopulation.KFF.2014.Availableat: https:// www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/health-coverage-and-care-for-theadult-criminal-justice-involved-population/.AccessedMarch19,2023.

39.DumontDM,GjelsvikA,RedmondN,etal.Jailsaspublichealth partners:incarcerationanddisparitiesamongmedicallyunderserved men. IntJMensHealth.2013;12(3):213–227.

40.PontJ,StöverH,WolffH.Dualloyaltyinprisonhealthcare. AmJPublic Health.2012;102(3):475–80.

41.ClearTR. HarminAmericanPenology.StateUniversityofNewYork Press;1994:3–4.

42.CullenFT.Assessingthepenalharmmovement. JRCD 1995;32(3):338–358.

43.HaberLA,EricksonHP,RanjiSR,etal.Acutecareforpatients whoareincarcerated:areview. JAMAInternMed 2019;179(11):1561–1567.

44.RoldWJ.ThirtyyearsafterEstellev.Gamble:alegalretrospective. JCorrectHealthCare.2008;14(1):11–20.

45.SonntagH.Medicinebehindbars:Regulatingandlitigatingprison healthcareunderstatelawfortyyearsafterEstellev.Gamble. CaseW ResLRev.2017;68:603.

46.RecognizingtheNeedsofincarceratedpatientsintheemergency department.ACEP.2006.Availableat: https://www.acep.org/ administration/resources/recognizing-the-needs-of-incarceratedpatients-in-the-emergency-department/ AccessedSeptember29,2022.

47.FrankJW,WangEA,Nunez-SmithM,etal.Discriminationbasedon criminalrecordandhealthcareutilizationamongmenrecently releasedfromprison:adescriptivestudy. HealthJustice 2014;2:6.

48.DouglasAD,ZaidiMY,MaatmanTK,etal.Caringforincarcerated patients:Caniteverbeequal? JSurgEduc.2021;78(6):e154–60.

49.BrooksKC,MakamAN,HaberLA.Caringforhospitalizedincarcerated patients:physicianandnurseexperience[publishedonlineaheadof print,2021Jan6]. JGenInternMed.2021;1–3.

–

Volume24,No.4:July2023WesternJournal of EmergencyMedicine 659 Armstrongetal. AddressingEDCareforPatientsExperiencingIncarceration

50.WorkingGrouponPolicingandPatientRightsoftheGeorgetown UniversityHealthJusticeAlliance.PoliceintheEmergencyDepartment: AMedicalProviderToolkitforProtectingPatienPrivacy. EMRA.2021. Availableat: https://www.law.georgetown.edu/health-justicealliance/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/2021/05/Police-in-the-EDMedical-Provider-Toolkit.pdf.AccessedMarch21,2023.

51.SongJS.Policingtheemergencyroom. HarvLRev 2020;134:2647–2720.

52.TessierW,KeeganW.Mandatorybloodtesting:Whencanpolice compelahealthprovidertodrawapatient’sbloodtodetermine bloodlevelsofalcoholorotherintoxicants? MoMed. 2019;116(4):274–277.

53.HaradaMY,Lara-MillánA,ChalwellLE.Policedpatients:Howthe presenceoflawenforcementintheemergencydepartmentimpacts medicalcare. AnnEmergMed.2021;78(6):738–48.

54.MartinRA,CoutureR,TaskerN,etal.Emergencymedicalcareof incarceratedpatients:opportunitiesforimprovementandcostsavings. PloSOne.2020;15(4):e023224

55.HiroseN,MoritaK,NakamuraM,etal.Associationbetweentheduration ofphysicalrestraintandpulmonaryembolisminpsychiatricpatients: Anestedcase–controlstudyusingaJapanesenationwidedatabase. ArchPsychiatrNurs.2021;35(5):534–40.

56.IshidaT,KatagiriT,UchidaH,etal.Incidenceofdeepveinthrombosis inrestrainedpsychiatricpatients. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(1):69–75.

57.PanY,JiangZ,YuanC,etal.Influenceofphysicalrestraintondelirium ofadultpatientsinICU:anestedcase-controlstudy. JClinNurs 2018;27(9–10):1950–1957.

58.VanRompaeyB,ElseviersMM,SchuurmansMJ,etal.Riskfactorsfor deliriuminintensivecarepatients:aprospectivecohortstudy. CritCare 2009;13(3):R77.Epub2009May20.

59.GuerreroP,MycykMB.Physicalandchemicalrestraints(anupdate). EmergMedClinNorthAm.2020;38(2):437–451.

60.Useofpatientrestraints[Internet]. ACEP.UpdatedApril2014.Available at: https://www.acep.org/patient-care/policy-statements/use-ofpatient-restraints/.AccessedSeptember29,2022.

61.JointCommissionStandardsonRestraintandSeclusion/Nonviolent CrisisInterventionTrainingProgram.CrisisPrevention.Updated2010. Availableat: https://www.crisisprevention.com/CPI/media/Media/ Resources/alignments/Joint-Commission-RestraintSeclusion-Alignment-2011.pdf.AccessedSeptember29,2022.

62.DignamB,AdashiEY.Healthrightsinthebalance:thecaseagainst perinatalshacklingofwomenbehindbars. HealthHumRights 2014;16:13.

63.DiTomasM,BickJ,WilliamsB.Shackledattheendoflife:Wecando better. AmJBioeth.2019;19(7):61–3.

64.HaberLA,PrattLA,EricksonHP,WilliamsBA.Shacklinginthehospital. JGenInternMed.2022;37(5):1258–60.

65.ScarletS,DreesenE.Surgeryinshackles:Whataresurgeons’ obligationstoincarceratedpatientsintheoperatingroom? AMAJ Ethics.2017;19(9):939

46.

66.UnitedStatesCode,2006Edition,Supplement3,Title42-thePublic HealthandWelfare.Title42-ThePublicHealthandWelfareChapter 136-ViolentCrimeControlandLawEnforcement.SubchapterI –PrisonsPartB-MiscellaneousProvisions.Sec.13726b-Federal regulationofprisonertransportcompanies.Published2009.Lawin effectasofFebruary1,2010.Availableat: https://www.govinfo.gov/app/ details/USCODE-2009-title42/USCODE-2009-title42-chap136subchapI-partB-sec13726b.AccessedSeptember29,2020.

67.Useofforceandapplicationofrestraints.USDepartmentofJustice: FederalBureauofPrisons.Updated2014.Availableat: https://www. bop.gov/policy/progstat/5566_006.pdf.AccessedSeptember29,2022.

68.UseofRestraints.DeschutesCountySherriff’sOffice.Published 2020.Availableat: https://sheriff.deschutes.org/CD-8-5%20Use %20of%20Restraints%20030220_Redacted.pdf

AccessedSeptember29,2022.

69.HofmeisterS,SoprychA.Teachingresidentphysiciansthepowerof implicitbiasandhowitimpactspatientcareutilizingpatientswhohave experiencedincarcerationasamodel. IntJPsychiatryMed 2017;52(4–6):345–54.

70.Whendoestheprivacyruleallowcoveredentitiestodiscloseprotected healthinformationtolawenforcementofficials?USDepartmentof Health&HumanServices.Updated2022.Availableat: https://www.hhs. gov/hipaa/for-professionals/faq/505/what-does-the-privacy-rule-allowcovered-entities-to-disclose-to-law-enforcement-officials/index.html AccessedSeptember26,2022.

71.LawEnforcementInformationGatheringintheEmergency Department.ACEP.Updated2017.Availableat: https://www. acep.org/patient-care/policy-statements/law-enforcementinformation-gathering-in-the-emergency-department/ AccessedSeptember26,2022.

72.HenkelS.ViolenceinHealthcareandtheUseofHandcuffs.IAHSS Foundation.2018Oct2;IAHSS-FRS-18-03.Availableat: https://iahssf. org/assets/IAHSS-Foundation-Violence-in-Healthcare-and-the-Useof-Handcuffs.pdf.AccessedSeptember26,2022.

73.SteinbergA.Pronerestraintcardiacarrest:Acomprehensivereviewof thescientificliteratureandanexplanationofthephysiology. MedSci Law.2021;61(3):215–226.

74.JointCommissionStandardsonRestraintandSeclusion/Nonviolent CrisisInterventionTrainingProgram.CrisisPrevention.Updated2010. Availableat: https://www.crisisprevention.com/CPI/media/Media/ Resources/alignments/Joint-Commission-Restraint-SeclusionAlignment-2011.pdf.AccessedSeptember29,2022.

75.LevinsonDR,GeneralI.Hospitalreportingofdeathsrelatedtorestraint andseclusion.DepartmentofHealthandHumanServices.Published 2006.Availableat: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-09-04-00350.pdf AccessedMarch19,2023.

76.GuarinoC.HolyCrossHealth:RestraintandPhysicalHold.Date Approved:October1,2018.Availableat: https://www.trinity-health.org/ assets/documents/credentialing/hcmdss-restraintand-physical-hold-policy.pdf.AccessedMarch21,2023.

–

WesternJournal of EmergencyMedicineVolume24,No.4:July2023 660 AddressingEDCareforPatientsExperiencingIncarceration Armstrongetal.

77.RestraintandSeclusion.TheUniversityofToledo.EffectiveDate: August1,2019.Availableat: https://www.utoledo.edu/policies/utmc/ nursing/unit/senior-behavioral-health/pdfs/3364-120-98.pdf AccessedMarch21,2023.

78.JonesA.Cruelandunusualpunishment:whenstatesdon’tprovideair conditioninginprison.PrisonPolicyInitiative.Published2019.Available at: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2019/06/18/air-conditioning/ AccessedSeptember29,2022.

79.ScarletS,DreesenEB.Surgicalcareofincarceratedpatients:doing therightthing,explicitbias,andethics. Surgery.2021;170(3):983–5.

80.MillerA.OvercrowdinginNebraska’sprisonsiscausingamedicaland mentalhealthcarecrisis.Published2017.Availableat: https://www. aclu.org/news/prisoners-rights/overcrowding-nebraskasprisons-causing.AccessedSeptember29,2022.

81.WidraE.Sinceyouasked:Justhowovercrowdedwereprisonsbefore thepandemic,andatthistimeofsocialdistancing,howovercrowdedare theynow?PrisonPolicyInitiative.Published2020.Availableat: https:// www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2020/12/21/overcrowding/ AccessedSeptember29,2022.

82.AllenSA,WakemanSE,CohenRL,etal.PhysiciansinUSprisons intheeraofmassincarceration. IntJPrisonHealth 2010;6(3):100–106.

83.PaulFarmerMarquardB.Dr.,whotirelesslybroughthealthcare totheworld’sneediest,diesat62-TheBostonGlobe[Internet]. BostonGlobe.com TheBostonGlobe;2022.Availableat: https://www. bostonglobe.com/2022/02/21/metro/dr-paul-farmer-whotirelessly-brought-health-care-worlds-neediest-dies-62/ AccessedSeptember29,2022.

Volume24,No.4:July2023WesternJournal of EmergencyMedicine 661 Armstrongetal. AddressingEDCareforPatientsExperiencingIncarceration

BRIEF EDUCATIONAL ADVANCES

AVirtualNationalDiversityMentoringInitiativetoPromote InclusioninEmergencyMedicine

TatianaCarrillo,DO*

LorenaMartinezRodriguez,DO†

AdairaLandry,MD,MEd‡

Al’aiAlvarez,MD§

AlyssaCeniza,BSW∥

RianeGay,MPA∥

AndreaGreen,MD¶

JessicaFaiz,MD,MSHPM#

SectionEditor:TehreemRehman,MD

*UniversityofPennsylvania,DepartmentofEmergencyMedicine,Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

† UniversityofSouthFlorida,DepartmentofEmergencyMedicine,Tampa,Florida

‡ HarvardMedicalSchool,DepartmentofEmergencyMedicine,Boston, Massachusetts

§ StanfordUniversity,DepartmentofEmergencyMedicine,Stanford,California

∥ AmericanCollegeofEmergencyPhysicians,Dallas,Texas

¶ TexasTechUniversityHealthSciencesCenter/UniversityMedicalCenterof ElPaso,ElPaso,Texas

# NationalClinicianScholarsProgram,VAGreaterLosAngelesHealthcare SystemandUCLA,LosAngeles,California

Submissionhistory:SubmittedDecember21,2022;RevisionreceivedMarch30,2023;AcceptedMarch27,2023

ElectronicallypublishedJuly12,2023

Fulltextavailablethroughopenaccessat http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

DOI: 10.5811/westjem.59666

Introduction: Traineesunderrepresentedinmedicine(URiM)faceadditionalchallengesseeking communityinpredominantlywhiteacademicspaces,astheyjuggletheeffectsofinstitutional,interpersonal, andinternalizedracismwhileundergoingmedicaltraining.Tooffersupportandaspacetosharethese uniqueexperiences,mentorshipforURiMtraineesisessential.However,URiMtraineeshavelimitedaccess tomentorshipfromURiMfaculty.Toaddressthisgap,wedevelopedanationalvirtualmentoringprogram thatpairedURiMtraineesinterestedinemergencymedicine(EM)withexperiencedmentors.

Methods: WedescribetheimplementationofavirtualDiversityMentoringInitiative(DMI)gearedtoward supportingURiMtraineesinterestedinEM.Theprogramdevelopmentinvolved1)partneringofnational EMorganizationstoobtainfunding;(2)identifyingacomprehensiveplatformtofacilitateparticipant communication,artificialintelligence-enabledmatching,andongoingdatacollection;3)focusingon targetedrecruitmentofURiMtrainees;and(4)fosteringregularleadershipmeetingcadenceto customizetheplatformandoptimizethementorshipexperience.

Conclusion: Wefoundthatbyusingavirtualplatform,theDMIenhancedtheef ficiencyofmentormenteepairing,tailoredmatchesbasedonparticipants’ interestsandthebandwidthofmentors,and successfullyestablishedcross-institutionalconnectionstosupportthementorshipneedsofURiM trainees.[WestJEmergMed.2023;24(4)662–667.]

BACKGROUND

Traineesunderrepresentedinmedicine(URiM)* face challengesseekingcommunityinpredominantlyWhite

academicspaces,astheyjuggletheeffectsofinstitutional, interpersonal,andinternalizedracismthroughoutmedical training.1–12 Theseeffectscancontributetoincreased

*TheAssociationofAmericanMedicalColleges(AAMC)definedthetermunderrepresentedminority(URM)toreflecttheracialgroupsofBlack,MexicanAmerican,mainlandPuertoRican,andNativeAmerican(AmericanIndianandnativesofAlaskaandHawaii).In2003,toencompasstheracialandethnic populationswithinmedicinewhoareunderrepresentedwhencomparedtotheirrespectivenumbersinthecontextofthegreaterpopulation,thiswasfurther clarifiedto “underrepresentedinmedicine” (URiMorUIM).AlthoughwerecognizetheuseofURiMorUIMinterchangeably,forconsistency,wehaveused thetermURiMthroughoutthispaper.

WesternJournal of EmergencyMedicineVolume24,No.4:July2023 662

experiencesoftheimposterphenomenonamongURiM trainees,whichcannegativelyaffectperformance.13–20 Lack ofsocialnetworkswithinmedicineandinformalknowledge duetodifferencesinparentaleducationandresources contributetobarrierstoinclusionandcareersuccess.21–25 To offersupportandaspacetosharetheseuniqueexperiences, mentorshipforURiMtraineesisessentialinacademic medicine,inadditiontoitsbenefitsofpromotinggreater careersatisfaction,productivity,andphysicianwellness.26–36

However,thereisascarcityofmentorshipforURiM trainees,whoespeciallybenefitfromfacultyofdiversegender identitiesandracialandethnicbackgrounds.37,38 URiM facultyareinstrumentalinpromotinginclusivetraining environmentsandhavebeenshowntoincreaseresidency programs ’ abilitytorecruitBlack,Latinx,andNative Americanresidentsandincreasegraduationratesamong URiMstudents.39–43 Unfortunately,thismentorshipis limitedbythesmallnumberofURiMfaculty,whoalready takeonadisproportionateburdenofmentorship.44–47 This minoritytaxcontributestoincreasedburnout,decreased productivity,anddecreasedcareerpromotion.48–51

Toaddressthisgap,wedevelopedanationalvirtual mentoringprogramthatstrategicallypairsURiMtrainees interestedinEMwithmentorsfamiliarwithmedical educationandcareerdevelopment.Wedescribehowto implementamodeltoexpandmentorshipaccessforURiM traineesandadvancerepresentation,inclusion,and belonginginEM.

OBJECTIVES

ThevirtualDiversityMentoringInitiative(DMI)aimed to(1)provideanaccessibleandsafeenvironmentforURiM participantstoshareexperiences;(2)connectwithother URiMtraineesandmentorsinEM;and(3)providepractical strategiestothrivepersonallyandprofessionallyasfuture emergencyphysicians.WemeasuredtheseobjectivesbyselfreportedsurveysregardingsatisfactionwiththeDMIand mentees’ abilitytoachievementorshipgoals.Thisstudywas deemedexemptfrominstitutionalreviewboard(IRB)review bytheStanfordIRB.

INNOVATIONDESIGN

TheAmericanCollegeofEmergencyPhysicians(ACEP) andtheEmergencyMedicineResidents’ Association(EMRA) partneredtoformtheDMIinSeptember2019.Facultyand traineesbeta-testedseveralvirtualmentoringplatforms.The primaryneedforavirtualformatwastheabilitytoscalethe DMIforlargecohortsbyenhancingtheefficiencyofmatching mentor-menteepairs,asopposedtomanualpairing.Other importantfeaturesincludedauser-friendlyinterface,asinglesign-onfeatureusingexistingACEPlogins,andtheabilityto collectdataonparticipantinteractionsandmentor-mentee pairsforreportableoutcomes.

WechosetheChronussoftware(ChronusLLC,Bellevue, WA)foritscomprehensiveplatformwiththeabilityto performartificialintelligence-enabledmatchingofmentormenteepairs,enrollparticipants,facilitateparticipant communication,andcollectlongitudinaldata.52 Chronus includedanaccountmanagerthatgeneratedreports, orientedusers,andtroubleshootedissues,beyondthe informationtechnologysupportthatmostotherplatforms offered.

Uponprograminitiation,mentorsandmenteescompleted aquestionnaireintheChronusplatformindicatingtheir goals,areasofexpertiseand,formentorstheirnumberof desiredmentees.Chronusthensuggestedpairingsbasedon responses.Menteeshadthe finalchoicetoselecttheirmentor fromashortlist.

Threementorshipcycleswerecompleted:August 2020–February2021,March2021–September2021,and October2021–June2022.WeadvertisedthroughTwitter, EMmedicaleducationnetworks(e.g.,CouncilofResidency DirectorsinEM),theEMRADiversityandInclusion committee,andtargetedoutreachtoHistoricallyBlack CollegesandUniversities’ EMinterestgroupstorecruit participants.

Tosupplementindividualmentor-menteerelationships, nine60-minuteeducationalandnetworkingeventsfor programparticipants,called “#MixMatchMingle,” were heldthroughoutthethreecyclestocreateacommunalspace toshareexperiences.Theformatofthe#MixMatchMingle eventsrangedfrominvitedguestspeakerstofacilitator-led discussionsonatopic.Eventthemesarelistedin Table1 and werechosenbytheleadershipteam,whohadvariouslevels oftrainingandfacultyexperience,diverseracialandethnic backgrounds,memberswhowere first-generationin medicine,andfacultyspecializinginmedicaleducation.By strategicallypairingmentorsandURiMmenteesbasedon theirgoalsandinterestsandfosteringawidercommunity withthe#MixMatchMinglecurriculum,DMIuses mentorshipasapedagogicalapproachtoEMcareer guidance.Italsoleveragesstrategiesgroundedinsocial capitalandsocialnetworktheorytoaddresspotential disparitiesininformalnetworksandknowledgein academia.53,54

Monthlyquantitativeandqualitativedatawerecollected viaChronusthroughouteachcycletomeasureprogram efficacyandinformsubsequentiterations(fullsurveyin SupplementalMaterial).Incrementaliterationsofworkflow andcustomizationoftheplatformwerenecessaryas unexpectedchallengesarose.Forexample,whenthenumber ofenrolleesdidnotmatchthenumberofparticipantspaired, wefoundthatitwaslargelyduetolackofparticipantprofile completion.Thus,weadjustedautomatede-mailreminders andmoreexplicitlycommunicatedtheimportanceofprofile completiontoparticipants.

Volume24,No.4:July2023WesternJournal of EmergencyMedicine 663 Carrilloetal. AVirtualNationalDiversityMentoringInitiativetoPromoteInclusioninEM

“

CohortIntroduction(orientationtoChronus,TheWhy’sand How’sofEffectiveMentorship)

AddressingImpostorPhenomenon

ResidencyApplicationPreparationandTips

COVID-19PandemicReflectionsandPracticing

Self-Compassion

ThrivingProfessionallyandFinancially:BuildingyourWealthin theStockMarket

LifeHacks” andTimeManagement

TransitionsinMedicineandtheRoleofMentorship

Mentor/Mentee-shipatDifferentCareerLevels

PathwaystoLeadershipinEM

COVID-19,coronavirusdisease2019; EM,emergencymedicine.

IMPACT/EFFECTIVENESS

Atotalof87mentorsand270menteesparticipatedinthe DMI.Theaveragementortomenteeratiowas1to1.6. Anonymoussurveysweredistributedtoparticipants.Ofthe 270mentees,215(79.6%)respondedtotheend-of-cohort survey.SuccessfulimplementationoftheDMIrequired fundingandstaffsupport,platformtroubleshooting,and earlyschedulingofeventsforparticipants.Weleveragedan existingpartnershipbetweenACEPandanacutecare staffingcompanyVituity(CEPAmerica,Inc,Emeryville, CA)tofundChronus.Administrativeandphysician programleadersmetbiweeklytodiscussdatageneratedby theplatform,troubleshootissueswithmentor-mentee pairing,anddesignthe#MixMatchMinglecurriculum. Thevirtualmentoringformatsuccessfullyprovidedaccess tomentorsdedicatedtoincreasingrepresentationin

RaceorEthnicity

MiddleEastern14(3.9)4(4.6)10(3.7)

*Participantswholisted “other” forleveloftrainingcitedrolessuchasMD-PhD,MBBS,osteopathicmedicalstudent,andchiefresident. MS,medicalstudent; PGY,postgraduateyear.

Table1. Topicsof#MixMatchMingleevents.

TotalN(%)MentorsMentees N(%)35787(24.4)270(75.6) Gender Men96(26.9)41(47.1)55(20.4) Women251(70.3)42(48.3)209(77.4) Non-Binary6(1.7)1(1.2)5(1.9) Transgender3(0.8)2(2.3)1(0.4) Undisclosed1(0.3)1(1.2)0 LevelofTraining MSYear1or292(25.8)092(34.1) MSYear3or4135(37.8)0135(50.0) PGY136(10.1)15(17.2)21(7.8) PGY210(2.8)3(3.4)7(2.6) PGY315(4.2)7(8.0)8(3.0) PGY46(1.7)5(5.7)1(0.4) Fellow19(5.3)18(20.7)1(0.4) Attending(1–5yearspost-residency)14(3.9)13(14.9)1(0.4)

yearspost-residency)6(1.7)6(6.9)0

Table2. CharacteristicsofuniqueparticipantsofthevirtualDiversityMentoringInitiativeacrossthreecohorts(August2020–June2022).

Attending(5+

Other*24(6.7)20(23.0)4(1.5)

Asian63(17.6)11(12.6)52(19.3) Black121(33.9)24(27.6)97(35.9) Latino/a74(20.7)13(14.9)61(22.6)

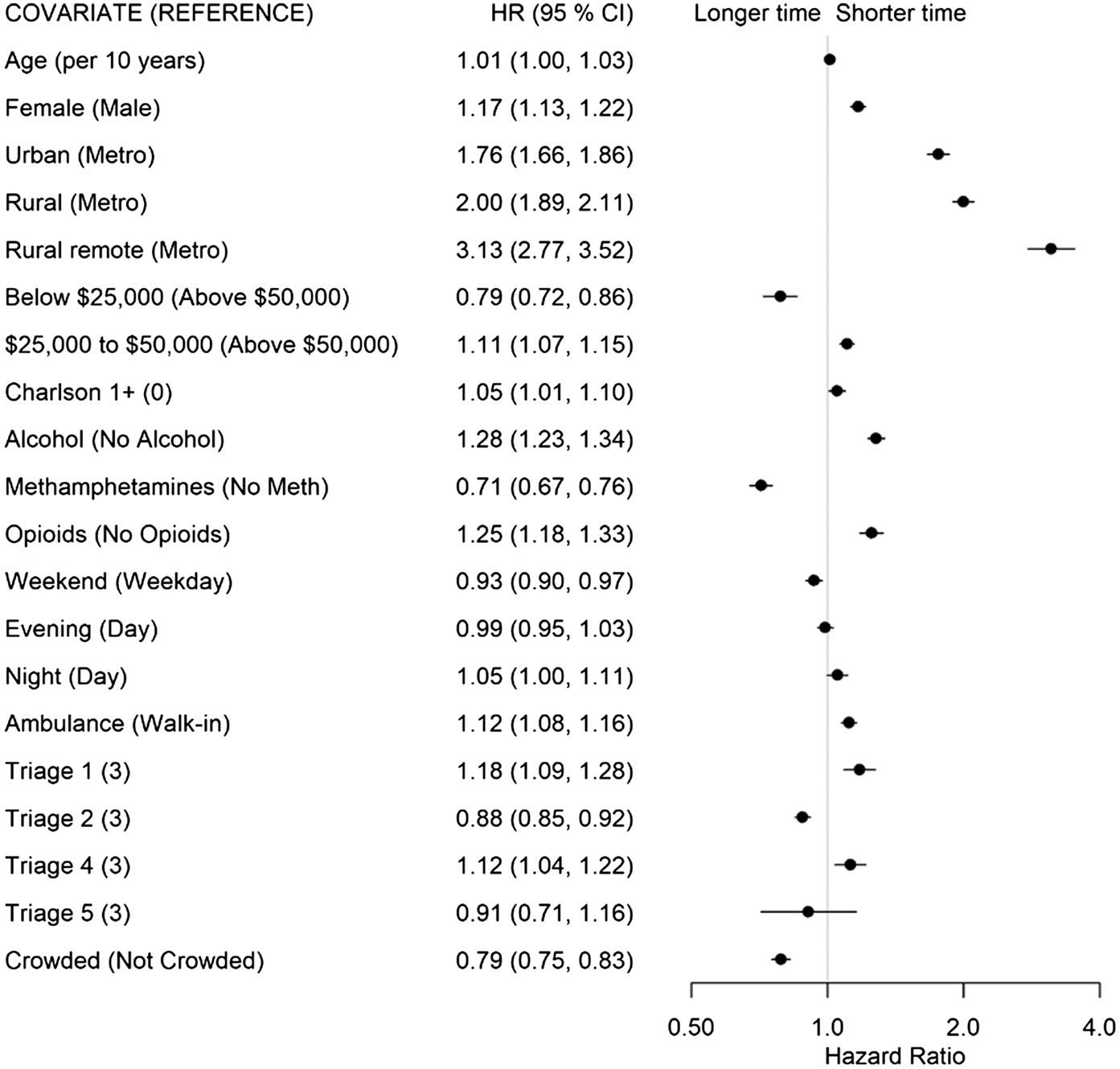

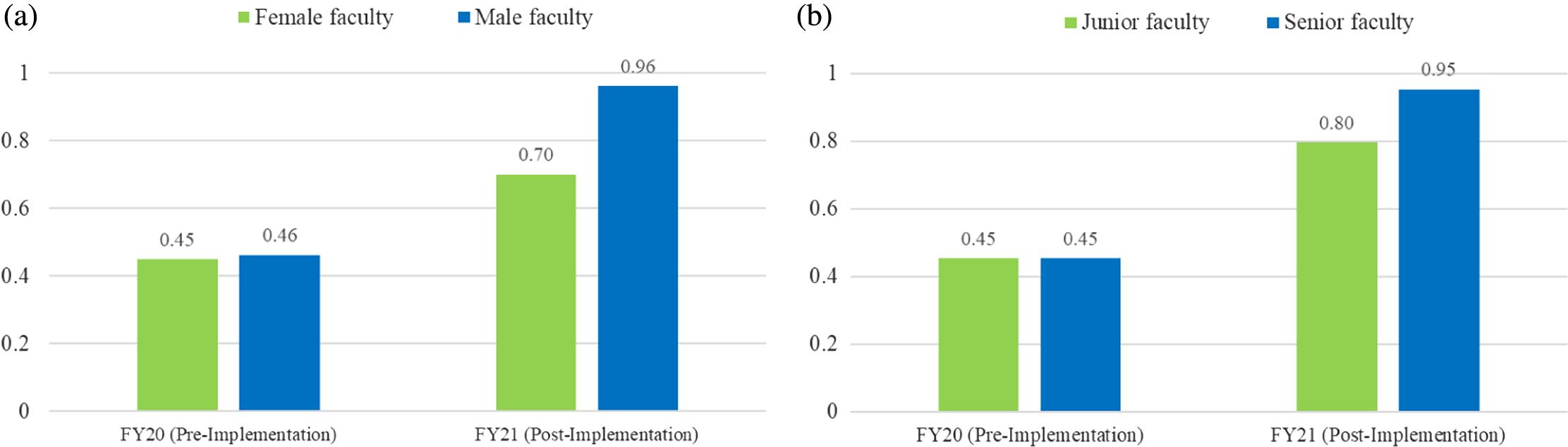

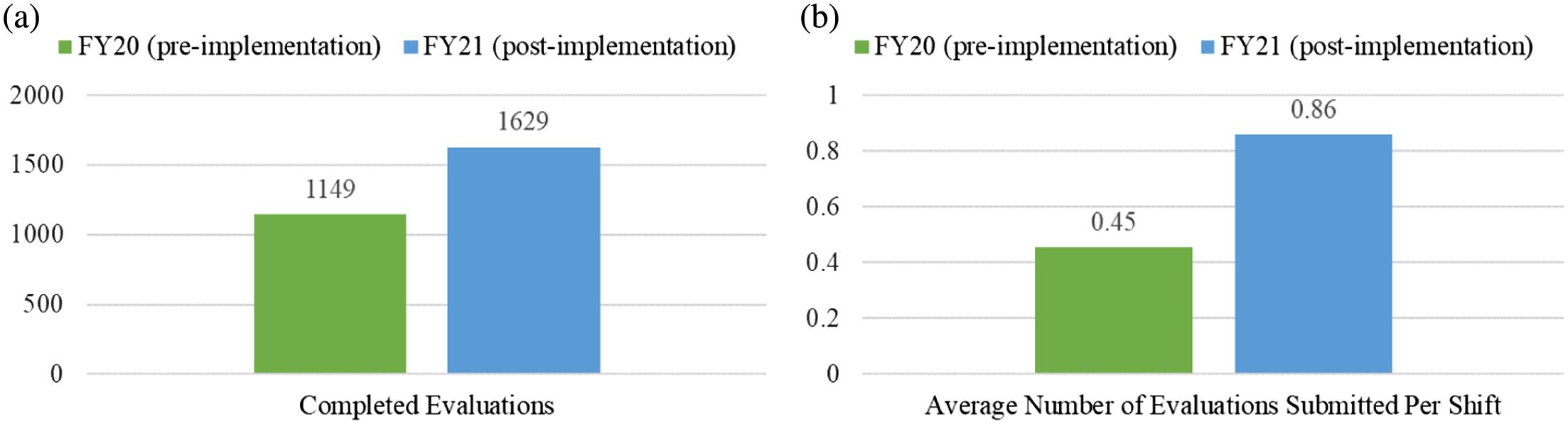

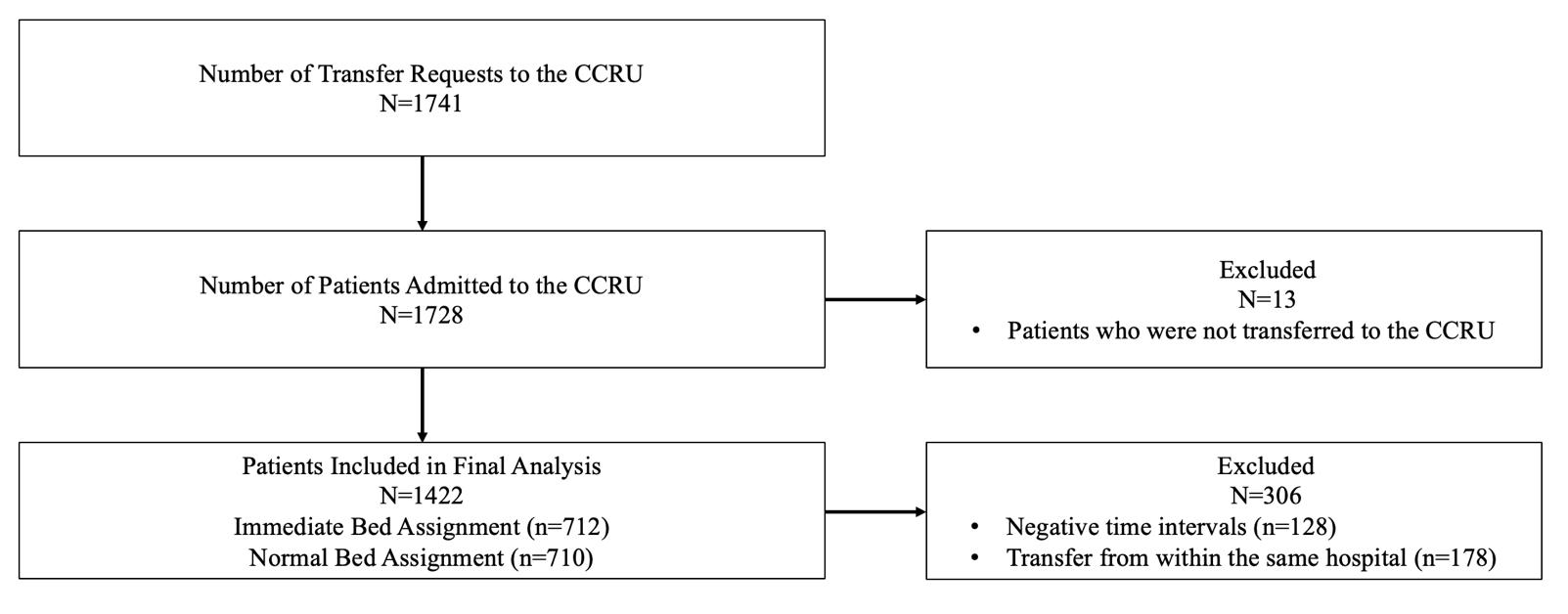

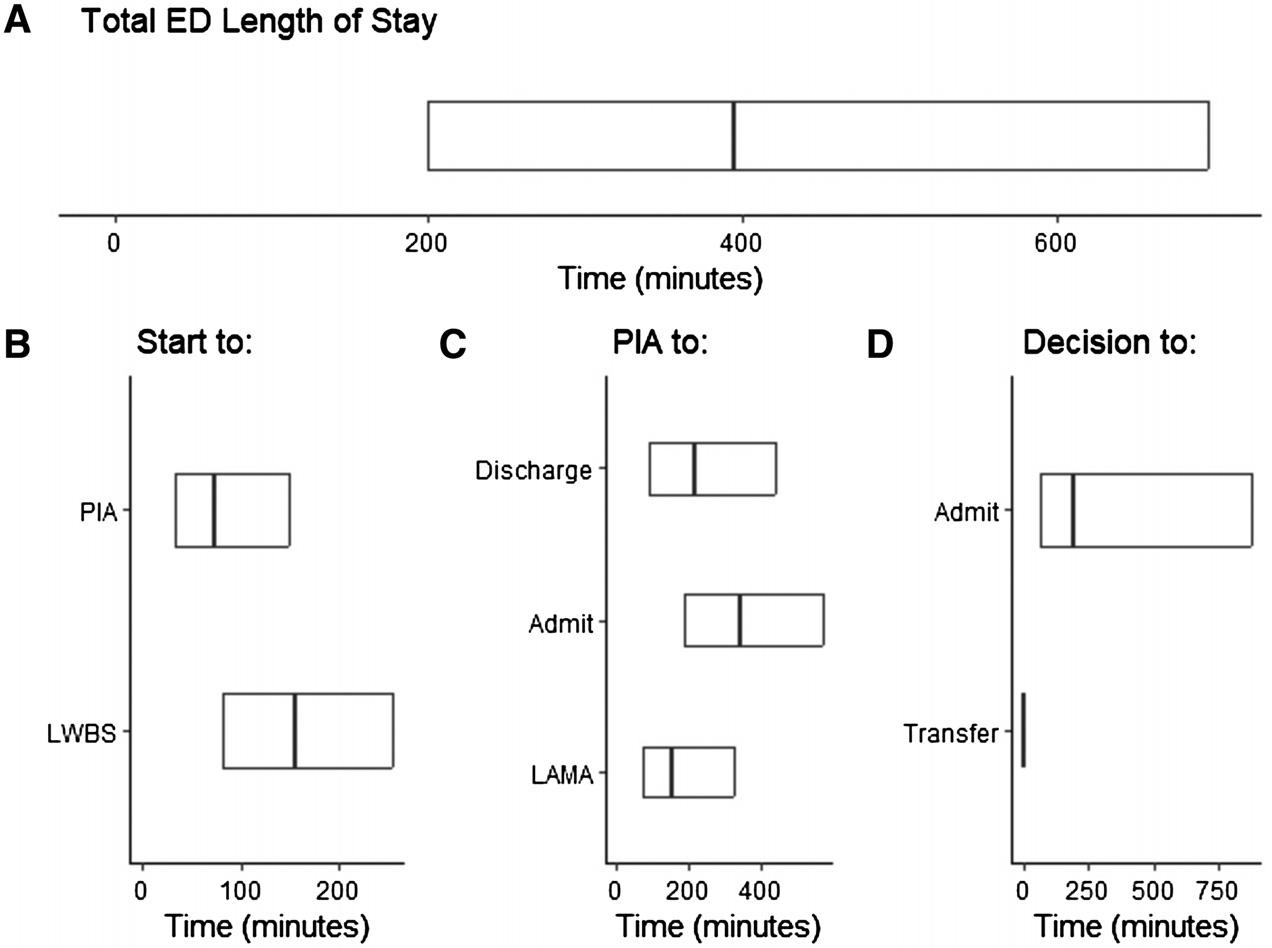

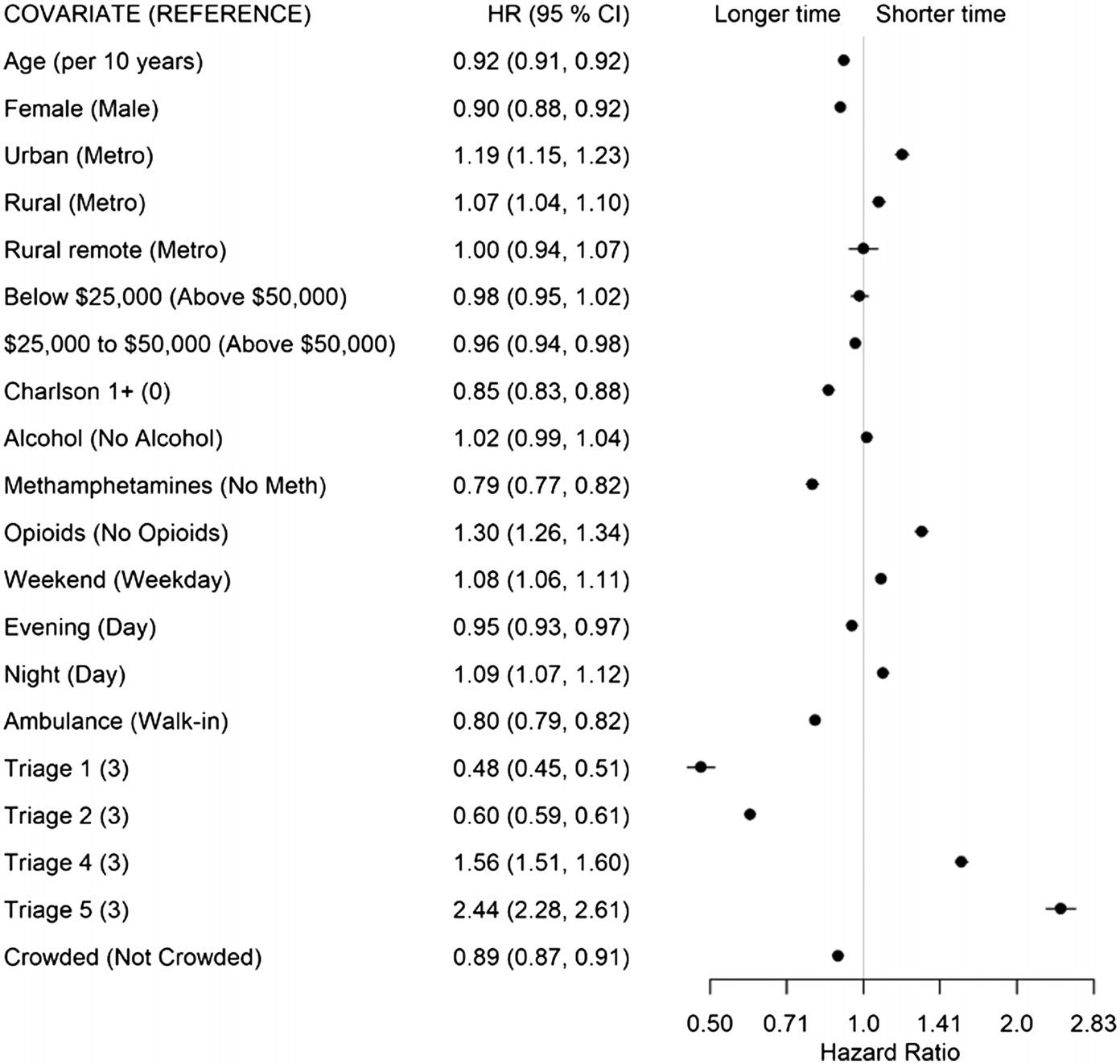

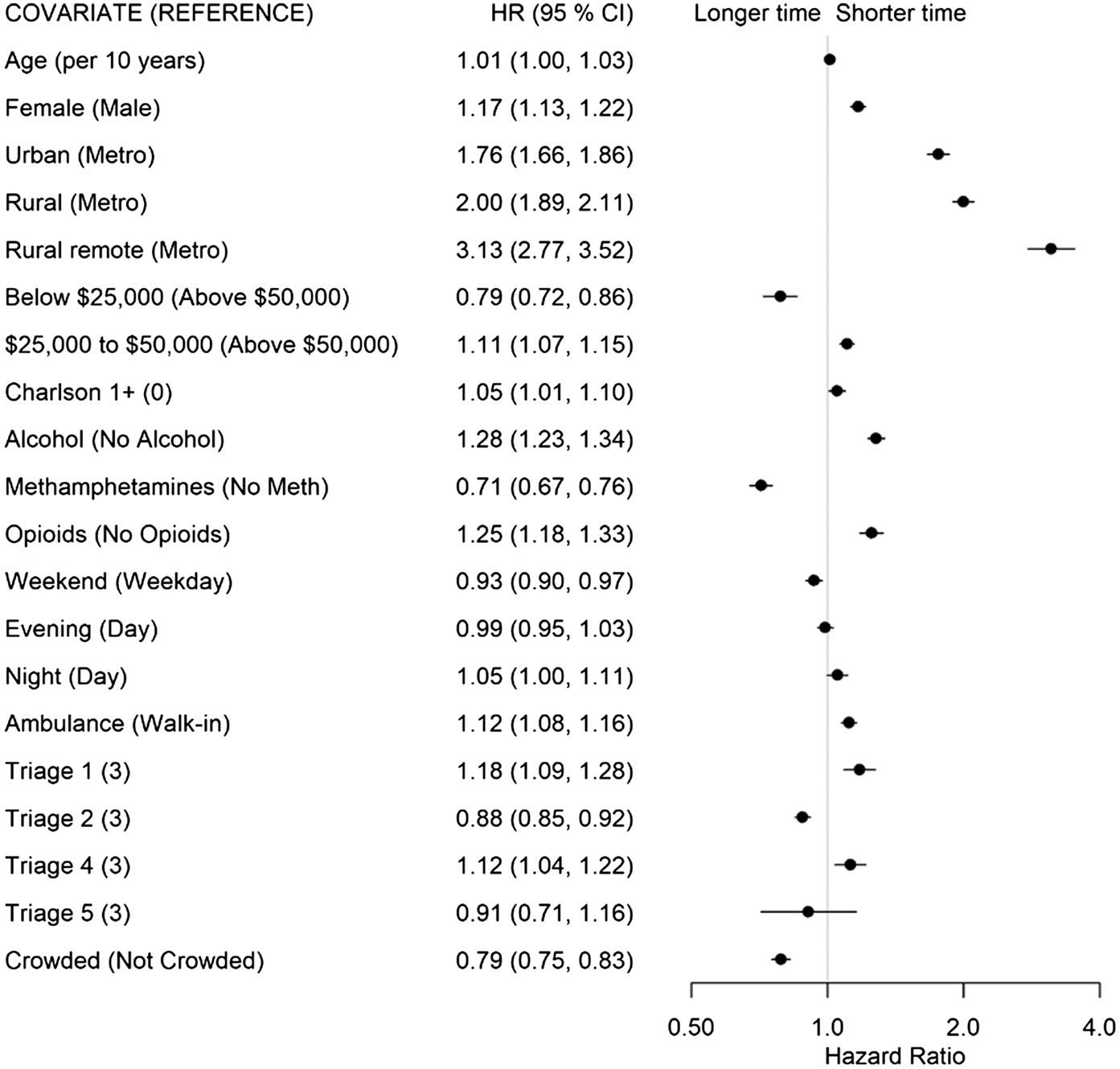

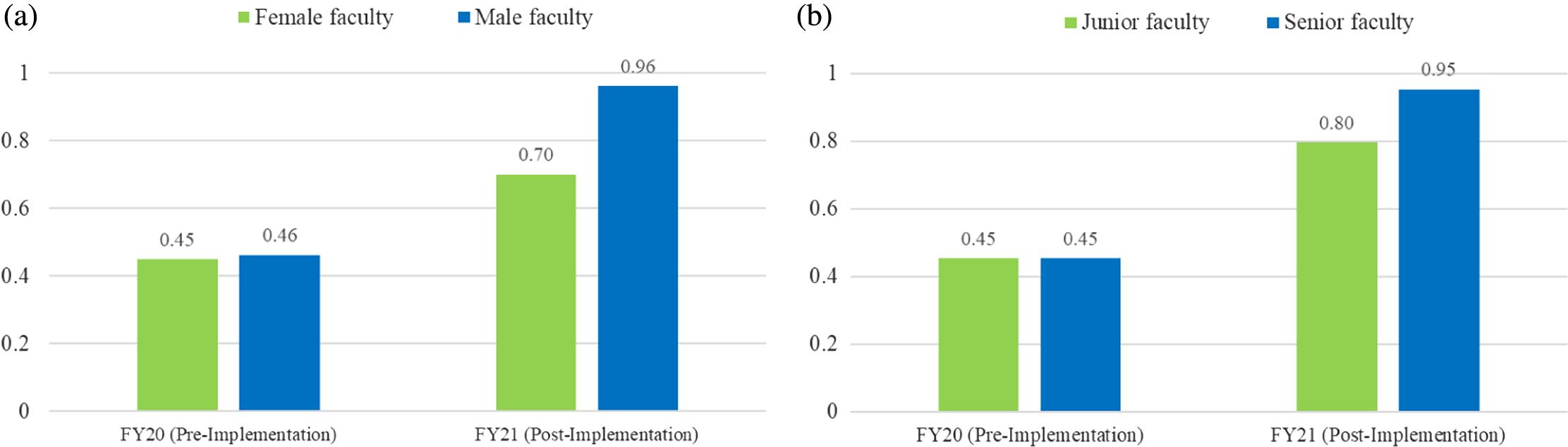

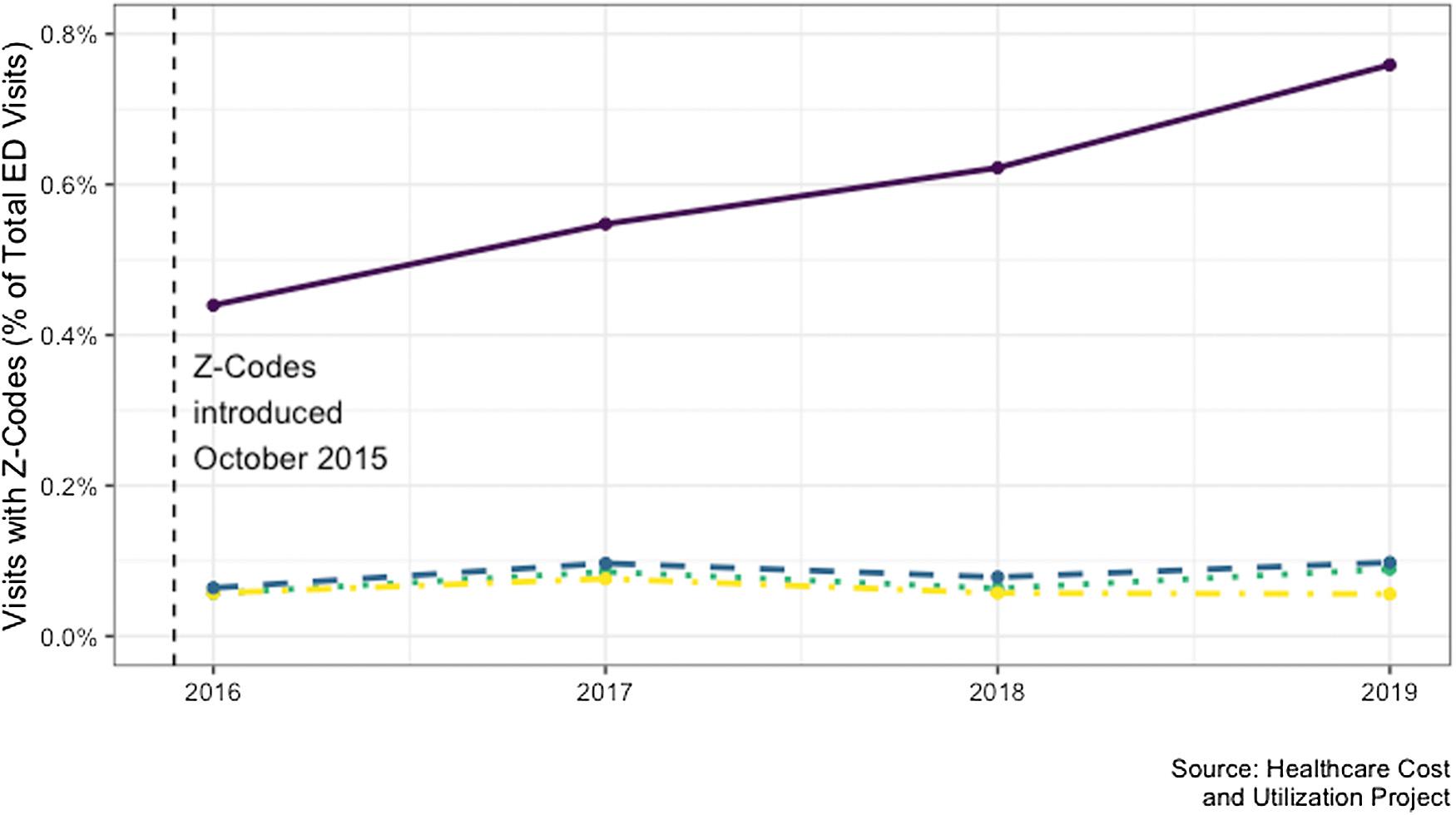

NativeAmerican5(1.4)05(1.9) NativeHawaiianorPacificIslander2(0.6)1(1.2)1(0.4) White60(16.8)33(37.9)27(10) Other18(5.0)1(1.2)17(6.3)