17 minute read

Canal & River Trust – Conserving our Waterways Heritage: Anderton Boat Lift and Pontcysyllte

Canal & River Trust – Conserving our Waterways Heritage: Anderton Boat Lift and Pontcysyllte Aqueduct*

Kate Lynch Landscape Architect. Heritage Advisor Canal & River Trust

Advertisement

Abstract

Our canals and river navigations represent an internationally important historic environment that largely date back to the Industrial Revolution. Today, canals in England and Wales are cared for by a charity, the Canal & River Trust. Our inland waterways have evolved over hundreds of years forming a diverse network of narrow and broad canals as wells as ‘canalised’ sections of river. The built environment of the waterways represents a unique working heritage of industrial architecture, archaeology and engineering structures and is a valuable part of our national heritage as well as an integral part of regional cultural heritage and local distinctiveness. This lecture will explain how the Trust cares for 2000 miles of waterways in England and Wales and will give an insight into Pontcysyllte Aqueduct (1805) and Anderton Boat Lift (1875), two of the charity’s most significant heritage structures and soaring monuments to the Canal Age. Keywords: Navigation, volunteers, working heritage, tourism

Resum

Els nostres canals i rius navegables constitueixen un entorn històric d’importància internacional, que es remunta en gran part a la Revolució Industrial. Avui, els canals a Anglaterra i Gal•les són atesos per una organització benèfica, el Canal & River Trust. Les nostres vies navegables interiors han evolucionat durant centenars d’anys formant una xarxa diversa de canals estrets i amples, així com trams de riu “canalitzats”. L’entorn construït de les vies fluvials representa un patrimoni productiu únic, d’arquitectura industrial, arqueologia i estructures d’enginyeria, i és una valuosa part del nostre patrimoni nacional, així com una part integral del patrimoni cultural regional i un distintiu local. Aquesta ponència explicarà com el Trust té cura de 2000 milles de vies fluvials a Anglaterra i Gal•les, i mostrarà l’Aqüeducte Pontcysyllte (1805) i l’Elevador de Vaixells de Anderton (1875), dues de les estructures patrimonials més importants de l’organització i destacats monuments de l’Època dels Canals. Paraules clau: Navegació, voluntaris, patrimoni productiu, turisme

Resumen

Nuestros canales y ríos navegables constituyen un entorno histórico de importancia internacional, que se remonta en gran parte a la Revolución Industrial. Hoy, los canales en Inglaterra y Gales son atendidos por una organización benéfica, el Canal & River Trust. Nuestras vías navegables interiores han evolucionado durante cientos de años formando una red diversa de canales estrechos y anchos, así como tramos de río “canalizados”. El entorno construido de las vías fluviales representa un patrimonio productivo único, de arquitectura industrial, arqueología y estructuras de ingeniería, y es una valiosa parte de nuestro patrimonio nacional, así como una parte integral del patrimonio cultural regional y un distintivo local. Esta ponencia explicará cómo el Trust conserva 2000 millas de vías fluviales en Inglaterra y Gales, y mostrará el Acueducto Pontcysyllte (1805) y el Elevador de Barcos de Anderton (1875), dos de las estructuras patrimoniales más importantes de la organización y destacados monumentos de la Época de los Canales. Palabras clave: Navegación, voluntarios, patrimonio productivo, turismo

*Aquest article és una transcripció literal de la ponència del Curset

The Canal and River Trust owns and looks after two thousand miles, or three thousand two hundred kilometres, of historic canals and river navigations in the United Kingdom. This paper offers a brief introduction to waterways heritage in the UK, what makes the waterways so special, and why and how they were built. It goes on to describe two wonders of the waterways, Anderton Boat Lift, and Pontcysyllte Aqueduct in North Wales. It finally talks about how the Canal and River Trust conserves and manages its waterway heritage today.

The Canal and River Trust is the guardian of an internationally important historic environment of outstanding value. Heritage is the whole waterway network which is around two hundred years old. It’s still working today, so it’s very much a living, working heritage. Waterways are part of the nation’s transport heritage, and the heyday of building was really between 1760 and 1840. It was quite short-lived in terms of transport heritage. However, waterways in Britain really helped to shape Britain and make it what it is today. Within about eighty years, roughly four thousand eight hundred kilometres of canal were dug, authorised by about three hundred acts of parliament. Inland waterways had been used for centuries, but it was only with the coming of the industrial revolution in Britain that they would become serious interlinking transport routes, harnessing horsepower and human ingenuity to carry cargos to and from market. This was the real reason for their being rather than what we see in Spain where the canal routes, canals and rivers were used more for irrigation. In Britain they were principally transport routes and were built to improve a means of providing a way of getting goods to and from market. One of the objectives of the Canal and River Trust is to protect and preserve our waterway heritage. It is therefore important to understand the history behind this. In the 1760s canals were built by hand, by groups of what were known as navigators or “navvies”. They were built with spade and shovel, there was no giant machinery like we have today. The canals were lined with clay as a waterproofing agent. The work was often very hard and dangerous. As the canals took many years to complete, some of them were never completed at all due to the canal companies running out of money. It’s important to realise that the canals were actually built around the horse, and some of the special features that can be seen on some of the canals still show evidence of that. For example, they show evidence of some of the rope marks that were caused by the horses as they pulled the boats along the canal. Before the canals were built

cargoes were typically carried on horse and cart, so you could only carry a very limited amount of coal (or lime or stone) to market. But once you had a canal boat and a horse, you could carry much more and that is why the canals became so popular as a new means of transport. These horses worked all through the night, they delivered goods to market, to Birmingham, to Manchester, carrying perishable goods such as food, cheese, milk. It was very hard work both for the horses and for the people that were using them.

The legacy that we are left with is a mixture of styles and structures and assets. From very small features to much bigger soaring aqueducts, and enormous bridges. There are a variety of locks. They may be wide or narrow, and their style will vary depending on where you are in the country. They were built from local materials like local stone, locally made brick, and so this is another reason why the styles change. Carving a straight route market as possible means there are many earthworks. These can be enormous cuttings or embankments, which were also carved by hand. There were also tunnels for canals too, the canal would go underneath the ground. These tunnels varied, sometimes the horse would go up to the left-hand side and go up to the top of the tunnel. Boats would be what’s called “legged” through. The men would sit on the top of the boats and then push the boats along with their feet on the top of the tunnel and then meet the horse at the other end. Other tunnels had towpaths through them so the horse would go through the tunnel. Some of the most striking features are the aqueducts that cross streams, rivers and roads. These were to keep the canal level, and so avoiding the need for building locks. Again, they could be built from brick, stone or even made partly from cast iron. With the canals also came the associated buildings too, which also varied in size and scale. Hundreds of docks and basins and wharves were created in industrial cities like Birmingham and Manchester, but also in smaller market towns and villages. This meant that goods could be unloaded, loaded or moved onto other types of transport. Other buildings could be much smaller,

through the countryside to try and create as direct a route to so it could be houses for places where the canal workers could live, stables for the horses, dry docks for maintaining the boats, and building the boats, and then also maintenance yards, for the general operation of the canal. Also, associated industries sprung up: For example, lime and brick kilns that took advantage of where the canal was to be able to transport the goods away as quickly as possible.

Two icons of our canal age are Pontcysyllte Aqueduct and Anderton Boat Lift. Pontcysyllte Aqueduct was built in 1805 and is in North Wales and Anderton Boat Lift was built later, in 1875, and is just over the border in Cheshire, in the North-West of England. Pontcysyllte Aqueduct, at 38 metres high, is the highest and longest aqueduct in the UK. It was built at the height of Britain’s industrial revolution using cast iron, a new technology at the time. For two hundred years it remained the highest aqueduct in the world. Ground-breaking techniques were used to command the landscape and link Welsh industry to the

wider world. It’s internationally recognised as a masterpiece of waterways engineering. It’s a pioneering example of iron construction in a dramatic setting. It’s a scheduled monument and in 2009 it was inscribed onto the world heritage list, together with eleven miles of the stretch of the canal. It was built on the Ellesmere Canal, or the Llangollen Canal, as it is called today. It was built between 1793 and 1808 and it was built to provide and improve the network to transport resources like coal, iron, slate and limestone to market. The industrialists needed a better form of transport to help exploit the minerals in the area, and connect Denbighshire, the local county in North Wales, to the wider world. It was built during what was known as Canal Mania in the 1790s. Everybody was getting involved and interested in building canals because they could see that this was a real success for their businesses. It was an extremely ambitious plan and it had to pass through challenging terrain; there were steep slopes and two very deep river valleys that had to be crossed. The key individuals involved, two significant engineers in Britain who then went on to become internationally recognised, William Jessop, who was already a well-established and experienced, respected engineer. He had worked on other canal projects in the UK. He was a very modest man, but he was the founding partner of the Butterley Ironwork Company in Derbyshire, and he knew about cast iron. Thomas Telford was ten years younger and this was the first canal project that he had worked on. He had been an architect, he had been the country surveyor for Shropshire in England, but he had never worked on a canal before. So, this was really his first project, and from here he went on to become very well-known both in Britain and Europe, and then further afield.

There was a very cautious approach to building the structure. First, a stone aqueduct was proposed, but there was obviously an enormous problem with trying to cross the valley. There was a growing enthusiasm in the region for using cast iron in construction, so they wanted to try this, a revolutionary idea to use a type of iron tank, supported on very high stone pillars to cross the valley. Telford’s first attempt was slightly lower at only five metres high, and fifty-six metres long. But it was really challenging the ideas and testing whether the iron would work and whether it could be held in this tank arrangement. The Pontcysyllte Aqueduct was built by moving earth from tunnel cuttings that were being built further along the canal, to build up huge

embankments, and then the stone piers were built up in stages using construction platforms. As they built a level, the platform was moved up until they got to thirty-eight metres high. The iron trough at the top is then constructed of a series of iron plates that are bolted together. The mortar on the stone is lime mortar, but it also contains ox blood. There are lots of samples that have been done to find out what they used. The joints of the iron are sealed with Welsh cloth, white lead and iron particles. And the flanged plates of cast iron are joined with wrought iron bolts and the thickness of the plates is only nineteen millimetres thick and it holds the canal as it crosses the valley. Five hundred people were involved in the construction and it cost forty-seven thousand pounds at the time to build.

It connected the landscape, and it connected the two sides of the valley. It was a bold engineering project, barely tested in canal construction. The embankments were very significant too. It was one of the largest earth-moving projects of the eighteenth century. And the aqueduct connected people too, so when it was completed in 1805 it was a source of inspiration, making it more than just part of the canal. It was seen as a work of art and people would come from miles to see it. Artists, engineers and architects visited it. Walter Scott described it as the most impressive work he had ever seen, and Charles Dupin described it as a “supreme work of architecture, elegant and unadorned”. About two hundred thousand visitors come to see this part of the canal every year so it needs to be carefully maintained. The site has had world heritage status since 2009 and all the decisions must be taken very carefully. There is a steering group, a number of key groups involving conservation expertise, planning and tourism to make sure that the correct decisions are made for this area.

Firstly, every ten years engineers from the Trust carry out inspections. The plates are only twenty-five millimetres thick, so it’s quite an experience when they take the water out of the aqueduct. It is emptied by removing a plug, literally like a bath plug. Twenty-four hours later all the water has been drained and you are left with an empty bath in the air that you can then inspect. The structure underwent some quite significant restoration works in 2003/2004, before the structure’s bicentenary; stonework, iron work repairs, and a detailed inspection. The Trust has some of the original timber casting patterns so when it carries out iron work repairs and needs to have new castings made, these timber patterns can be used in order to achieve an exact match to how the structure was originally built. Any massive challenge. The structure is thirty-eight metres high, so everything tends to be done through rope access.

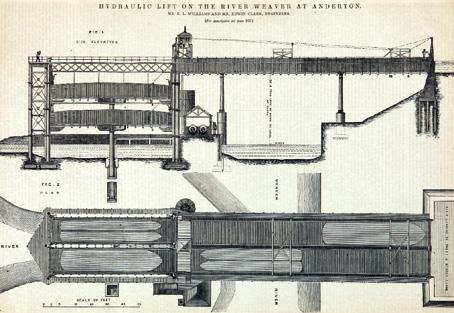

The Anderton Boat Lift is very different. This is a structure with moving parts so it’s living heritage, but it’s living and moving and still working today. The Anderton Boat Lift is another wonder of the waterways and the Canal and River Trust has worked hard to look after it. It was constructed in 1875, as a hydraulically operated boat lift, linking the Trent and Mersey Canal to the river Weaver, fifteen metres below. It was built in response to the growing salt industry in Cheshire, and for transporting china clay to the Midlands for the pottery industry. It’s a complicated arrangement of different phases of construction, showing innovation and expertise. It was the world’s first commercially successful boat lift and in 1976 it was designated a scheduled monument.

It was built initially as a hydraulically operated boat lift to move salt on boats up onto the canal above, and it operated with two tanks, or caissons, that moved the boats up and down hydraulically. There were all kinds of issues with its construction and with its operation which then went on to influence how it changed in appearance. The three key people involved were Leader Williams and Edwin Clark, who were involved with the idea and the construction of the hydraulically operated lift, and AJ Saner, who in 1908, was involved with transforming it to electric operation. When it was built, there were two tanks of water with the boats in, which sat side by side and moved up and down hydraulically. The water is sourced from the canal for the new castings are date stamped. Vegetation management is a

hydraulics and that was partly the reason for its failure. There were some quite catastrophic failures with its construction, which led to significant deterioration and subsequently ceased to operate. It was then changed, and an A-frame superstructure was developed around it, and this remained in operation for about seventy-five years. From the 1950s boat traffic declined and it was eventually closed in 1983. However, there was a huge amount of support for its restoration, and in 2002, after seven million pounds worth of funding, it was reopened. Today there are visits, tours, events, you can get married on the lift if you want to, people are taken up on the top so they can have a look, there is a fireworks night there, so it’s very much a living, working heritage that is looked after carefully.

The Canal and River Trust is moving up in heritage management. It doesn’t only have these two structures. It has 2700 listed buildings that it looks after in England and Wales, and it has a specialist team to look after the structures. It works very carefully on compliance, to make sure that it is carrying out works according to the law. There are significant challenges. The British weather is a challenge and most of the work is done in the wintertime, so it is very cold, very icy. This difficult work must be done quite quickly so people can get their boats back on the canal. Furthermore, over a million pounds each year is spent on

trying to repair the damage to bridges from agricultural vehicles or people who have gone too fast. The Trust doesn’t own the roads, so it doesn’t have much control of that, but it does own the bridges, which it has to pay for, which is quite a challenge.

The Trust sometimes has to bring in specialist stone masons or other people to help, and a growing number of volunteers that help. So, as a charity the Trust frequently works with volunteers that help on some smaller tasks of restoring the waterways. It is important to make sure that everybody has the right skills and training in place so that the structures are being repaired in the right way.

The Trust has had to move in new directions. Some of the work is incredibly repetitive. The lock gates, for instance, are replaced on a twenty-year cycle. And if you can imagine doing that with 2700 listed structures, huge numbers of locks, this can become very repetitive, so it needs to find a way of doing this and managing this effectively.

The Trust has been doing this by using Heritage Partnership Agreements, which reduces the paperwork, saves time and money, and is a partnership between local government and the Canal and River Trust, to give advance consent for some repairs that need to be done instead of applying for permission every single time. The Trust also works with the government. It is out

to consultation at present for developing a national list of building consent orders for the whole of England. So, the Canal and River Trust will be very much a test bed for that.

The Trust has open days where people can come down into the locks and actually see the work at hand, see the engineers and the craftsmen working. There are blacksmiths that also open up their forges so people can come and see them working. It’s very much about keeping a waterways heritage alive.

Our inland waterways are working heritage and they require a great deal of understanding and careful management. Pontcysyllte Aqueduct and Anderton Boat Lift are recognised nationally and internationally as masterpieces of waterways engineering.

The Canal and River Trust aims to look after our waterways so that others can use them now and into the future.