11 minute read

The Montgomery Canal - its history, its heritage and its restoration, working in Partnership

John Dodwell Chair of the Montgomery Canal Partnership and a former Trustee of Canal & River Trust of the United Kingdom

Abstract

Advertisement

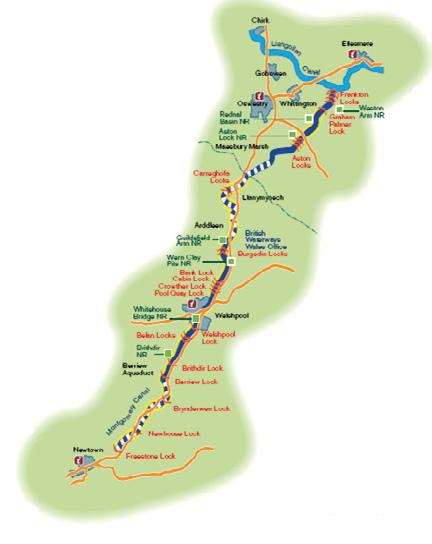

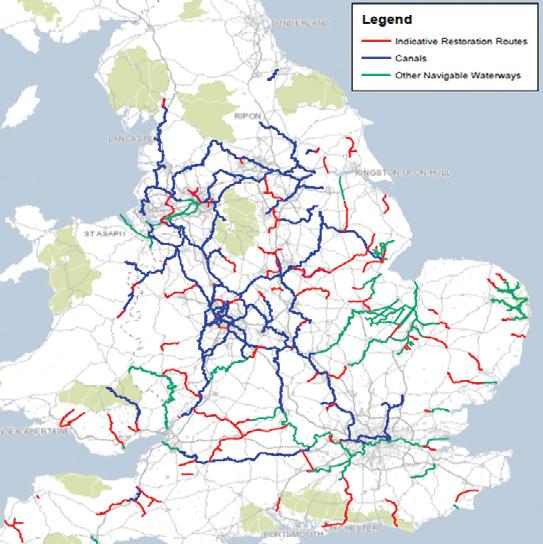

The lecturer will speak about the decline and revival of the Montgomery Canal in the United Kingdom. Built in phases mainly over 200 years ago, the Canal runs for 35 miles in a north/south direction from near Oswestry (Shropshire, England) across the border with Wales and onto Welshpool before finishing in Newtown (both in Powys, Wales). The Canal became derelict in the 1930s after the effect of road and rail competition and then some road bridges were destroyed, blocking the Canal. In 1969, restoration works started, led by voluntary groups. Work has been steady but slow. Now about 50% of the Canal has been restored, including almost all the locks. Most of the Canal is a Site of Special Scientific Interest and in Wales is also a Special Area of Conservation. Through the Montgomery Canal Partnership, a Conservation Management Strategy was developed. Now there is a 10 Years’ Strategy to complete – in phases – the restoration to Welshpool, before continuing to Newtown. Recent restoration has been helped by a grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund and by efforts by volunteers who undertake significant civil engineering works. All this helps to protect and enhance the Canal’s built and natural heritage. Keywords: Montgomery Canal, Montgomery Canal Partnership, Canal, Shropshire, Partnership

Resum

El ponent parlarà sobre el declivi i el renaixement del Canal Montgomery al Regne Unit. Construït en fases principalment fa més de 200 anys, el Canal s’estén per 35 milles (aprox. 56 Km) en direcció nord / sud des de prop de Oswestry (Shropshire, Anglaterra) a través de la frontera amb Gal•les i sobre Welshpool abans d’acabar a Newtown (tots dos a Powys, Gal·les). El Canal va quedar abandonat a la dècada de 1930 a conseqüència de l’efecte de la competència viària i ferroviària i després es van destruir alguns ponts de carretera, bloquejant el Canal. El 1969 van començar els treballs de restauració, dirigits per grups voluntaris. El treball ha estat constant però lent. Fins ara ha estat restaurat al voltant del 50% del Canal, incloent gairebé totes les rescloses. La major part del Canal està qualificat de Lloc d’Especial Interès Científic, i a Gal·les també és una Àrea Especial de Conservació. A través de l’Associació del Canal de Montgomery, es va desenvolupar una Estratègia de Gestió de la Conservació. Ara hi ha una Estratègia de 10 anys per a completar -en fases- la restauració a Welshpool, abans de continuar cap a Newtown. La restauració més recent ha estat recolzada per una subvenció del Heritage Lottery Fund i pels esforços de voluntaris que emprenen importants obres d’enginyeria civil. Tot això ajuda a protegir i millorar el patrimoni construït i natural del Canal. Paraules clau: Canal Montgomery, Associació del Canal Montgomery, Canal, Shropshire, Associació

Resumen

El ponente hablará sobre el declive y el renacimiento del Canal Montgomery en el Reino Unido. Construido en fases principalmente hace más de 200 años, el Canal se extiende por 35 millas (aprox. 56 Km) en dirección norte/sur desde cerca de Oswestry (Shropshire, Inglaterra) a través de la frontera con Gales y sobre Welshpool antes de terminar en Newtown (ambos en Powys, Gales). El Canal quedó abandonado en la década de 1930 a consecuencia del efecto de la competencia vial y ferroviaria y después se destruyeron algunos puentes de carretera, bloqueando el Canal. En 1969 comenzaron los trabajos de restauración, dirigidos por grupos voluntarios. El trabajo ha sido constante pero lento. Hasta ahora ha sido restaurado alrededor del 50% del Canal, incluyendo casi todas las esclusas. La mayor parte del Canal está calificado de Sitio de Especial Interés Científico y en Gales también es un Área Especial de Conservación. A través de la Asociación del Canal de Montgomery, se desarrolló una Estrategia de Gestión de la Conservación. Ahora hay una Estrategia de 10 años para completar, en fases, la restauración a Welshpool, antes de continuar hacia Newtown. La restauración más reciente ha sido apoyada por una subvención del Heritage Lottery Fund y por los esfuerzos de voluntarios que emprenden importantes obras de ingeniería civil. Todo esto ayuda a proteger y mejorar el patrimonio construido y natural del Canal. Palabras clave: Canal Montgomery, Asociación del Canal Montgomery, Canal, Shropshire, Asociación

The Canal was built in three phases, the last ending in 1819. The Canal descends 12 locks down into the River Severn valley and then up 14 locks to reach Newtown, almost in the middle of Wales. It goes 35 miles (56km) from near Oswestry through Welshpool to Newtown.

This Canal was different. Many were built to take coal into cities. This Canal carried large amounts of limestone. When burnt, limestone produces lime. Lime was spread on the fields to improve the soil. So the canal boats took lime from limestone burning kilns all along the 35 miles of this Canal – and to other places.

The original local investors in the Canal hoped to improve the quality of their land as well as make profits from the Canal. The Canal engineers wanted to build the Canal as quickly and as cheaply as possible. Fortunately, they left behind a rich heritage of structures for us to enjoy. There are 127 structures which are listed by Heritage England as being a special importance.

For over 100 years after being built, the Canal kept going. But by the 1920’s, the Canal was owned by a railway company which saw the Canal as competition. Lorry transport was starting up. The Canal became ignored. In 1936 part of the banks in England collapsed and the water ran out. The Canal wasn’t repaired.

The road authorities began knocking down hump-backed canal bridges to make life easier for lorries. The rest of the Canal began rotting away and the future looked bad.

Towards the end of the 1960s, a new road was proposed along the line of the Canal in the town of Welshpool. The people of Welshpool did not like the idea. The Canal lovers did not like the idea. This meant there were lots of objections. But other people said the Canal was “a stinking ditch” so, over one weekend 300 canal volunteers from all over the country came to clear the Canal of mud and rubbish.

That started the restoration of the Canal. Prince Charles – the Prince of Wales – got interested and more restoration followed. First, a few miles were re-opened around Welshpool. Then bridges on each side of Welshpool were rebuilt and some of the locks were restored. By the year 2000, 12 miles either side of Welshpool had been re-opened.

Work had been going on in the English part. The Canal had nevin the Canal which need protecting. In some parts, there great

er been repaired after the banks collapsed in 1936 and slowly store the Canal argued with those who wanted to keep it as that whilst excessive boat movement was bad, some boat

the water drained away in other parts.

In the 1980s, volunteers began rebuilding the locks at Frankton. By the year 1996, the Canal was reopened to Queens Head. It was not just the Canal which was being restored but also some of the warehouses. Volunteers then worked on the next three locks at Aston and so by 2003 a total of 5 miles had been reopened.

By this time, 23 of the 26 locks had been restored. 17 miles of

This been achieved by an enormous amount of effort! By canal volunteers – and not just digging out the mud. Volunteers help to design engineering solutions. They help to raise money. There was a lot of effort by staff working for the Canal’s owners. There was enthusiasm from local people and money from the local councils and the Lottery Fund. And with money from the local councils and from the European Union, everyone worked together.

Part of the Canal in England is a Site of Special Scientific Interest. All of the Canal in Wales is also a Site of Special Scientific Interest – and it is a Special Area of Conservation. These designations are there to protect the natural life heritage of the Canal. For, during the years of closure, nature took over. There is a rare water plant floating water plantain and other rare plants crested newts.

As restoration work progressed, those who wanted to reit was in a closed state. In the year 2005 a compromise was reached. It was accepted that leaving the Canal as it was would not produce a solution. The Canal would continue to rot and eventually the water would disappear – and with it, the rare plants and newts. Tests were carried out about the effect of boats moving on the restored Canal – which showed the 35 miles – 50% - were back in use.

movement was good.

The compromise resulted in a Conservation Management Strategy being agreed in 2005. This looked to protect both the built

heritage and the natural heritage. Specifically, it provided for the building of new nature reserves along the restored Canal into which the rare plants could be moved.

By the time plans had been developed for the next stage of the restoration, the world economic crisis from the years 2007 to 2010 was upon us. Local authority money was no longer available. However, the Heritage Lottery Fund granted £2.5m towards £4m of works. Work started in 2018 and is scheduled to be finished by the end of 2020.

The £4m spending will help with the need to build new nature reserves. It includes relining the dry Canal bed so it will hold water again. When it is all finished, another two miles will be fully re-opened.

In the meantime, we’ve developed a Ten Years’ Strategy to link up to the 12 miles isolated section in Welshpool. And then onto the end in Newtown.

Phase 1 is what we are doing at the moment – to get to a place called Crickheath.

Phase 2 is to complete the next two miles to get to the Welsh border – where the Canal is in water again. Relining the dry Canal bed and rebuilding one road bridge.

Phase 3 is to deal with the challenges in Wales to get to Welshpool. These include building new nature reserves, rebuilding four road bridges and doing a lot of dredging. We aim to plan

that in the next 5 years and raise the money and then spend years 5 to 10 doing the actual works.

Phase 4 is to continue past Welshpool and get to Newtown – where the Canal used to end.

We will do this by working in partnership with others. Restoring the Canal is not just getting the water back in the Canal and getting boats moving along. It is far, far more than that. There are economic benefits from tourism. This will create jobs. There are advantages to the buildings and natural life around the Canal. There are opportunities for training in the construction industry. There are opportunities for the community – both young and old – and living both near and distant – to work together and volunteer to restore the Canal. Unlike many projects, this is not a single purpose mission.

This is why the Montgomery Canal Partnership was set up in 1999 - to bring together all the various groups interested in seeing the Canal restored. Its membership consists of the owners, the two local county councils, the statutory environmental and heritage organisations, the wildlife trusts and the Canal restoration societies. It was the Partnership which produced the 2005 Conservation Management Strategy. And it is the Partnership which is now taking a lead in driving the restoration project forward.

We have the keen support from the Leaders of both County Councils. That doesn’t mean money as British local councils are still cutting costs. But it does mean, for example, that when we

met the Welsh Government Minister for Tourism last month, he knew we had strong local support for the restoration.

The role of volunteers has been actually been. With the help of I hope I have been able to show you the value of working in

volunteers, all but three locks at the Newtown end have been restored. The volunteers have kept going in the lean years when it seemed not much was happening. From 2008 to 2014 they relined about half a mile of the Canal.

Volunteers help to reduce the costs. One part of the restoration had been estimated to cost £15m – using contracting companies. A retired civil engineer made a new calculation - assuming the use of volunteers – and came to about £5m. That was for the cost of materials and equipment hire.

age and history of the Montgomery Canal – a wonderful survivor of Britain’s Industrial Revolution – and how it is being revived. I hope I have been able to show you something about the herit-

Partnership.