ALEJANDRO VARELA WRITING SAMPLE

This document discusses the Uruguayan curatorial production through the architectural Venice Biennale. To do this, it approaches the historical dimension of the Uruguayan pavilion, describes the curatorial projects between 2000 and 2016, and critically analyzes the discussion held in 2017. This essay is part of the course Themes and Problems of Architecture and the City of the Master’s Degree in Architecture with a Historical, Theoretical and Critical Approach of the School of Architecture, Design, and Urbanism of UdelaR.

SUMMARY

Student:

Alejandro Varela

Professors: Mary Mendez

Santiago medero

Lucio de Souza

Uruguay acquired the pavilion in 1960. However, different socio-political and economic situations led the country to pay attention to the architecture biennale just in the 2000s (see the chart below). During these last 20 years, different institutional entities and the academic community have tried different formats to define participation in the Architectural Biennale, such as direct commissions and, closed and open contests. At the same time, the competition terms have varied in aspects of evaluation and the selection of the juries. Often, juries range from those who have not been to Venice to those who have never had a curatorial practice but are “good architects.”

Over the years, the curatorial proposals have varied in type and shape, some approaching artistic issues, others more of a historical or archival nature, and the most recent have had the virtue of linking local production to problems of international relevance. However, in this genealogy of facts, it has yet to be possible to consolidate either continuity of the curatorial exercise or a strong curatorial production capable of having academic and social repercussions. Therefore, participation in the Venice Biennale happens as an isolated event, revisited every two years.

The analogy to Rudofsky in his 1964 MoMA exhibition allows us to associate the hegemonic disciplinary lack of the national curatorial practice. The essay seeks, without falling into a formal simplification, to investigate beyond photography through the study of exhibition catalogs and a series of interviews and analyze the panel discussion held

in 2017 to bring to light the successes, failures, and continuities between the projects. Although, even with making visible the fact that our local curatorial production is based on the instinct about what curatorial architectural practice is, like Architecture made without architects.

Note: The first graph makes it possible to visualize the relationship between Uruguay and the Venice Biennale and to identify which historical events influence this relationship. The second graph allows an agile reading of the body of each edition, its form of designation, proposal, authors, juries, and authorities. Moreover, the different projects are presented in file format to be able to be worked on and disseminated individually.

First

Opportunity to Uruguay with Argentina, Brazil, Mexico and Chile to have a shared place in the Gardens of Venice

1931

Uruguay acquires the pavilion, concession of the pavilion for 30 years. 1960

1940

1930 Music, Cinema and Theater began

The cultural institution1 that today encloses the Biennale di Venezia arose in 1895 from the first International Art Exhibition. It was in the 1930s that Music, Cinema, and Theater began to be celebrated.2 In 1931, Uruguay —with Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, and Chile— had the possibility of having a shared place in Los Jardines de Venecia, although this operation was unsuccessful.3 In 1948, the institution resumed its activity after the culmination of fascism, and it was not until 1960 that Uruguay acquired the concession of the pavilion for 30 years.4

The Uruguayan pavilion, a space built in 1958 for the service of the Biennale,5 was popularly associated with storage space for the Biennale, an aspect that appears in various descriptions

VENICE BIENNALE TIMELINE

1948

The institution restarts its activity after the culmination of fascism.

New Statute, President Directors of the sectors: Cinema, Music,

and stories,6 but questioned by Miguel Fascioli in his work on research “The national pavilion at the Venice Biennale,” based on documentation that describes the use of that space during previous years as an exhibition space, used by Turkey, Tunisia and the island of Malta. Likewise, Fascioli affirms that because it is a space built inside the hill, it seems complicated to access to fulfill storage functions. 7

In 1968, student protests hindered the inauguration of the Biennial. However, they produced institutional changes that culminated in a new Statute (1973), a structure around a board that had to elect the President and nominate the Directors of the different sectors: Visual Arts, Cinema, Music, and Theater. In 1975, under the presidency of Car-

1- “On December 23, the Italian Government approved the reform of the Biennale, presented by the Minister of Culture, which transformed the Biennale into a Foundation open to contributions from the private sector.” See more: Venice Biennale official page, History: www.biennale.org/en/history

2- See more: Official page of the Venice Biennale, History: https://www.labiennale. org/en/history

3- Miguel Fascioli, 2012, Research project: The national pavilion at the Venice Biennale, p. 9.

4- A concession that today is renewed every 19 years, with the next renewal in 2027. See more: Uruguay. Ministry of Exterior Relations (2015): http://www.mrree.gub.uy/

Economic crisis 1982

Temporary Framework (00-17)

Economic crisis 2002

Dictatorship (1973/85)

2020

1973 President and the different Visual Arts, Music, Theater

1975

First Architecture exhibition called “About Mulino Stucky”.

1980

First international architecture exhibition “La presenza del passato” P. Portoghesi

lo Ripa di Meana, the first Architecture exhibition called “A proposo del Mulino Stucky” emerged —as an extension of the Visual Arts Sector— under the direction of Vittorio Gregotti, followed by “Werkbund 1907 Alle origini del design”, “Il razionalismo e l’architettura in Italia durante il fascismo” and “Europa-America, centro storico, suburbo” in 1976; and “Utopia e crisi dell’antitinatura. Architectural Intentions in Italy” in 1978.

It was not until 1980, under the presidency of Giuseppe Galasso, that Paolo Portoghesi was given the direction of the Architecture sector and directed the first international architecture exhibition called “La presenza del passato,” 8 which, together with the “Teatro del Mondo” in Bacino San Marco carried out by Aldo Rossi in 1979, position

frontend/page?1,inicio,bienal-de-venecia,O,es,0,

5- “Erected in 1958 due to the need to serve the XXIX Biennale, the Uruguayan government requested the building the following year...” Marco Mulazzani in “Guide to the Padiglioni of the Biennale of Venice of 1887” page 120. (Milano, 1988)

6- See publication on the FADU website: http://www.fadu.edu.uy/patio/?p=40721 and http://www.fadu.edu.uy/sac/exposiciones/venecia-uy/

7- “In particular, the Uruguayan pavilion is located on a small hill, called San Antonio, on the top of which there was previously a small square surrounded by a mountain of chestnut trees and acacias, many of which are still maintained today surrounding the modest perimeter of the pavilion, framing his façade.” Miguel Fascioli, 2012,

2020 Interruption due to Pandemic

2021 Restart

Venice and the Biennale in the great discussions on postmodern architecture on the international scene. Unfortunately, during this period, Uruguay did not participate in the Venice Biennale due to its political situation until the return to democracy.

Research project: The national pavilion at the Venice Biennale, p. 13.

8- “... is the riflessione sul cosiddetto Postmodern movement. Such a movement became in discussion the Modern, with its many legati al nuovo, alla tecnologia e alla purezza delle forme geometrice. Poiché il presente sembra non offerrire ormai nulla di new rispetto al pastato, ecco che il Postmoderno suggestisce una nuova visione sincronica della Historia, che venta serbatoio infinite di immagini e suggestivi, da cui gli architetti possono recuperare liberamente forme, stilemi ed elementi decorativi.”

See more on Official website of the Venice Biennale: https://www.labiennale.org/it/ storia-della-biennale-architettura

Call, Jury and Advisors

Sponsored by the Ministry of External relationships, the Municipality of Montevideo with Mariano Arana as mayor, and the embassies of Spain, France and Italy.

Dean

Ruben Otero

Ministry of Education and Culture

Ministry of External relationships

Minister: Antonio Mercader

Ruben Otero

Minister: Leandro Guzmán

Minister: Didier Opertti

Direct designation of the Dean. Closed call to professors (grades 3 and 4)

Dean: Salvador Scheloto According to file 031130-001416-08 The dean selects the proposal

Form: by File

Minister: Jorge Brovetto

Minister: Reinaldo Apolo

Minister: Ing. Maria Simón

Director of Culture: Luis Mardones

Minister: Dr. Gonzalo Fernández

Director of Culture: Carlos Flanagan

Not found

00

Montevideo: a city for a theater, a theater for a city.

Proposals Team

Curators: Carlos Pascula and Alvaro Fariña

Advisor curator: Ricardo Pascale

Uruguay does not make proposals for the 2002 and 2004 Architecture Biennials.

In an attempt to participate under the deanship of Ruben Otero, the School sends the Architect Gustavo Vera Ocampo to monitor the state of the pavilion. He discovered a compromised situation where homeless people had occupied that space. This intention was frustrated by the economic crisis our country was experiencing at that time and the diffuse responsibility that the Ministries of Education and Culture and Foreign Relations with the cause. The reason why in 2004, the use of the pavilion was ceded to Argentina.

Therefore, Uruguay lost the opportunity to participate in the eighth exhibition, under the theme “Next,” proposed by the writer Deyan Sudjic, and in the ninth exhibition, “Metamorph,” directed by the architectural historian Kurt W. Forster. As a result, we a result, we lost the opportunity to participate in the discussion on the scope of new technologies in the production of architecture that had been a constant in these two editions. Moreover, this interval delayed working on the logic that would allow the structure to be given to architecture submissions.

Venice Biennale

Theme: Less Aesthetics, More Ethics.

Curator: Massimiliano Fuksas

Theme: Next Curator: Deyan Sudjic

Theme: Metamorph

Curator: Kurt W. Forster

“MONTEVIDEO SEMINARS, Spaces For Collective Reflection And Proposals On Urban Themes”

Curator: Cristina Bausero

Advisor curator: - - -

THE VENICE LOOM Genealogy

Theme: Città. Architettura e società

Curator: Richard Burdett

Image of the catalogs, were obtained from fadu.edu.uy and the images of the events of labiennale.org

Curators: Marcelo Danza and Miguel Fascioli

Assistants: Federico Parra and Felipe Ridao

Advisor curator: - - -

Theme: Out There: Architecture Beyond Building

Curator: Aaron Betsky

Form: Open contest: Raised Terms by As. Ac. Louis oreggioni File 031130-000629-10

Jury: Salvador Scheloto, Gustavo Scheps, Mario Sagradini and Patricia Bentacur Does not appear in the resolution But Angela Perdomo participates.Advisors: Cristina Bausero, Miguel Fascioli and As. Ac. louis oreggioni

Minister: Emb. Luis Almagro

Director of Culture: Emb. Alberto

Open contest

Jury: Fernando Miranda, Enrique Aguerre, Juan Carlos Apolo, Conrado Pintos, Diego Capandeguy. Advisors: As. Ac. Luis Oreggioni Lucio de Souza (cur. 2010), Marcelo Danza (cur. 2008) and Ricardo Cordero

Jury: Pedro livni and Marcelo Dance. Advisors: As. Ac. louis oreggioni

Jury: Patricia Bentancor, Bernardo Martín and Emilio Nisivoccia

Advisors: As. Ac. Carina Strata

Jury: Sebastián Alonso, Martín Cobas, Marcelo Danza, Alejandro Denes, Ricardo Pascale.Advisors: As. Ac. Carina Strata

Gustavo Scheps Marcelo Danza

Minister: Ricardo Erlich

Director of Culture: Dr. Hugo Achugar

Minister: Emb. Luis Almagro

Director of Culture: Pablo Scheiner

Minister: Maria Julia Muñoz

Director of Culture:Sergio Mautone

Minister: Rodolfo Nin Novoa

Director of Culture: Omar Mesa

SP / IT / EN 233 pág 15x21 SP / EN 247 pág 22x27 SP / EN 343 pág 15.5x20 SP / IT / EN 184 pág 15.5x20 SP 112 pág 21x29.5

16

10 5 NARRATIVES, 5 BUILDINGS

Curators: Emilio Nisivocia, Lucio de Souza, Martin Craciun and Sebastian Alonso

Advisor curator: - - -

12 PANAVISIÓN:

14

ALDEA FELIZ: episodes of modernization in Uruguay.

Curators:Pedro Livni and Gonzalo Carrasco

Assistants: Federico Lapeyre

Advisor curator: Daniela Freiberg

Guests: Marcelo and Martin Gualano de g+; Horacio flora and Alejandro Baptista de 11:54 pm; Marrio Baez and Adrian Duran de MBAD; Marcelo Bednarik and Federico Mirabal de BM, Diego Perez, Fabio Ayerra, Marcos Castaings, Martin Cobas and Javier Lanza de Fábrica de paisaje; and Matias Carballal, Andres Goba and Mauricio Lopez de MAAM.

Theme: Common Ground

Curators: Emilio Nisivocia, Mary Méndez, Martin Craciun, Jorge Nudelman, Sanitago Medero and Jorge Gambin

Assistants: Laura Nozar, Martín Cajade and Oficina 206u, Súbito, LabMVD, Carolina Gilardi and Mariana Diaz

Advisor curator: Daniela Freiberg

Guest writers: Jorge F. Liernur, Patricio del Real, Lucio de Souza, Lorena Logiuratto, Jorge sierra, Leandro Villalba and Nicolas

16 REBOOT: Two Architecture Lessons

17 18

Curators: Marcelo Danza, Miguel Fascioli, Marcelo Starico, Borja Fermoselle, Diego Cataldo and José de los Santos

Assistants: Mateo Vidal, Facundo Romero and Matteo Locci

Advisor curator: Miguel Fascioli.

Curators: Sergio Aldama, Federico Colom, Diego Morera, Jimena Ríos y Mauricio Wood

Assistants: Bruna Baietto and Sebastián Lambert.

Advisor curator: Alejandro Denes

Curator: Kazuyo Sejima

Curator: David Chipperfield

Theme: Fundamentals

Curator: Rem Koolhaas

Theme: Reporting from the Front

Curator: Alejandro Aravena

Theme: Freespace

Curator: Yvonne Farrell e Shelley McNamara

Note: names underlined, participated in previous instances of the Biennale, or have some curatorial experience at the time of the contest.

Discussion panel

The first architecture commission was made just in the seventh edition of the Architecture Biennale in the year 2000, directed by Massimiliano Fuksas under the name “Less Aesthetics, More Ethics.” It sought to abandon the focus on the built object and turn attention to the contemporary city from work in three thematic axes: The social, the environmental, and the technological. It proposed to search for new “ethical” responses to the accelerated transformation of the cities of the underdeveloped world (Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Africa were the focus of this call).9

Uruguay sends —sponsored by the Ministry of External Relations, the Municipality of Montevideo with Mariano Arana as mayor, and the embassies of Spain, France, and Italy— a project called “Montevideo: a city for a theater, a theater for a city” to charge of Carlos Pascual and Alvaro Farina, and with Ricardo Pascale as adivsor curator. The project consists of an audiovisual installation of three screens that showed images of Montevideo, its historic center, and the cultural district (comprising the Solís Theater, the Sodre, the AFE station, and the Sarandí-18 de Julio pedestrian axis).10

Mercader in his column in the newspaper El País “Arana reopened the History of the Solís restoration in the Departmental Board, an epic that has already lasted six years and that has consumed 16 million dollars in a sequence of errors, marches, and counter-marches paid for by the taxpayer”. The journalist affirms that the object of the exhibition was to attract those interested

in financing the works of Solís. Unfortunately, the interested parties never showed up. 11 Also, it was also not well recognized by the academic field regarding the involvement of —at that time— the School of Architecture in submissions to the Venice Biennale.12

This edition was controversial in many ways, even more so as it was Uruguay’s first participation in the Biennial. Regardless, one aspect is noteworthy: Mariano Arana, an architect and a history professor at the School of Architecture with an extensive background in patrimonial aspects, was in a position of authority, which made possible the start using the pavilion for the Architecture Venice Biennale.

Curators: Carlos Pascual & Alvaro Fariña

MONTEVIDEO: A CITY FOR A THEATER, A THEATER FOR A CITY

9- Massimiliano Fuksas: “I will use the Biennale as a laboratory to analyze the new planetary dimension of urban behavior and transformation” See more on the Official Website of the Venice Biennale, Story, “Less aesthetic, more ethical”: https://www .labiennale.org/it/ storiadella-biennale-architettura#accordion-9-collapse

10- La Red 21 press release. See more: https://www.lr21.com.uy/cultura/13618-uruguayen-la-bienal-de-arquitectura-de-venecia

11- “(...) the aim was to attract people interested in financing the Solís works (...),” Quote from the newspaper El Pais published on October 4, 2000, in Miguel Fascioli, 2012, Initiation research project: The national pavilion at the Venice Biennale, p. 21

12- At the discussion panel on “The Venice Pavilion” moderated by Magalí Pastorino. In the said meeting, the invitation to the curators of the first shipment had not been considered, which will end controversies around the academic body’s assessment of said proposal. In any case, Carlos Pascual was present and expressed his opinion and discontent on the subject. See R15 Magazine, Article by Magalí Pastorino Rodríguez, “A look at the Uruguayan Pavilion at the Venice Biennale,” page 132.

Uruguay did not participate in the 2002 Biennial due to the economic crisis, nor the 2004 edition because the pavilion was ceded to Argentina’s use, which suppressed the possibility of beginning to exercise curatorial practice in those years.13

Just in 2006, the Ministry of External Relations invited the School of Architecture to participate in the tenth International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale. Directed by the British architect Richard Burdett and titled “Città. Architettura e società” this edition had the mission of addressing the so-called “global cities,” those with a population —of more than three or four million inhabitants— in continuous increase, problems of migration and mobility, and in search of development sustainable.”14 Uruguay faced the difficulty of a theme that exceeded its urban conditions, being that the total of the country’s population is equivalent to that suggested by the general curator in a single city.

For this instance, the council university approves the actions of Dean Salvador Schelotto. It directly selects the Academic Assistant Cristina Bausero as curator of the second shipment from Uruguay to the Venice Gardens. Called “Montevideo Seminars,

Spaces For Collective Reflection And Proposals

On Urban Themes,” the Uruguayan submission focused on showing the production generated within the framework of the Montevideo Seminars.15 The proposal needed more local production content because the Montevideo seminar was an academic activity carried out

within the university by foreign guests.16

Since 2006, Uruguay has participated without interruption in the Venice Architecture Biennale, and the Ministry of Education and Culture has delegated the responsibility of managing submissions to the School of Architecture. However, there is constant uncertainty because each edition requires prior approval by the ministries involved to make the call. Usually, this aspect leads to the contest being made later than in other countries, many times happening 3 or 4 months before the Biennial opening.

Curator: Cristina Bausero

MONTEVIDEO SEMINARS: SPACES FOR COLLECTIVE REFLECTION AND

13- See “The loom of Venice”, on the previous page.

14- “The exhibition analyzes crucial issues of contemporary society, deepening the interaction between cities, architecture, and inhabitants. In particular, it examines the role of architects and architecture in creating sustainable and democratic urban contexts and their links to policy interventions, government actions, and social cohesion. See more: Venice Biennale official page, History: https://www.labiennale. org/en/history

15- Refers to a workshop that was held once a year with an international guest. Where different urban and territorial problematics were rehearsed.

16- “…Uruguay presented itself with the Montevideo seminars that were products made by foreigners in Uruguay, it is kind of schizophrenic …” Pedro Livni, in notes from the discussion table on “The Venice Pavilion” moderated by Magalí Pastorino Rodriguez within the framework of the R15 in 2017. SMA Archive.

For the eleventh edition, a closed call for university professors (grades 3 and 4) was made —in a short period— to present proposals for Curatorship at the Biennial in 2008. The contest terms expressed the need to “draw state of the art” in local architectural theory and production to show it abroad, which is rarely shown abroad.17 Also, responding to the topic raised by Aaron Betsky, “Out there: Architecture beyond the building,” in Betsky’s words, the proposal seeks to “advance towards an architecture without buildings, to face crucial issues of society” and to collect and encourage experimentation, not through built work but through seductive images.18

The Dean in charge selected the proposal LUP + TANGO by Marcelo Danza and Miguel Fascioli as curators and Felipe Ridao and Federico Parra as collaborators. The proposal was declared — under a broad spectrum of possibilities— as: “an invitation to think about architecture from Uruguay, beyond buildings and discipline, and offer a unique opportunity to learn about our current architectural and urban culture, its ideas and proposals, their achievements, their illusions, their debates, their achievements and frustrations, their rebellion.”19

LUP approached the general curator’s proposal in two ways, the first by rethinking and reviewing local production in terms of architectural culture, and the second by addressing the problem from a local perspective, where “Out There: Architecture Beyond Buildings” in the key of —how the curators define— a “political south” can be reinterpreted as: “Right here: life beyond the building.”

Although the proposal is close to the general theme, in exhibition terms, it is defined exclusively by the placement of a catalog. Unfortunately, the “political south” curators talk about was not being materialized. The catalog as a device in the exhibition is an evident effect of the possible scope of the material according to the monetary funds available. However, on the other hand, it is worth noting the content of the catalog.

The first episode presents key photographs of Uruguayan events, interventions, and iconic works in the first half of the 20th century (The Centenario stadium and the construction of Clinicas hospital, among others). It culminates with two statements —which constantly compare the north and the south— one called “Gravity 0,” which refers to a field without cultural friction, and a second called “malleable bodies,” which refers to the bodies in that field of gravity and friction 0. The authors argue that “the malleable body and its “creative spirit” seem to have weakened, and therefore the cultural

Curators: Marcelo Danza & Miguel Fascioli

LUP:

URBAN POLITICAL LABORATORY

virulence of previous years has extinguished. The episode ended with a series of neologisms, and popular or political expressions, which are supposed to reflect a national cultural identity, such as: “We are fantastic.” Although the strategy is attractive because it makes different aspects of popular culture visible, it does not link them with the concerns of the architectural discipline.

A second episode, called Normal Pressure and Temperature Condition (CPTN), features a series of passages. The first passage defines LUP as: “a Laboratory of Political Urbanism”20. The following passage, called “Visibility,” refers to the practical aspect of this exhibition. LUP carried a meeting at the National Museum of Visual Arts (MNAV) between July 14 and 19, 2008, for which a call was made open to individuals and groups to submit proposals according to the theme. The last passage, “Exploration,” expresses the workshop’s findings as a menu of multiple ideas without a synchronic or diachronic order allowing them to interconnect.

“Weakness: architecture as displacement of energies”; “Vulnerabilities, as resistance”; “Globality, as a connection”; “inefficiency, as a limit”; “excitement, as a life drive,”; among others, are the categories used to group this information. Although being seductive and participating in topics of global discussion are not deepened from the local condition. This general position integrates many participants with various ideas and has the doubtful aspect of looking at everything without saying anything in particular. However, the construction of this thematic repertoire was significant precedent

for future proposals. For example: Reviewing local production at the beginning of the catalog serves as an antecedent to the “5 narratives, 5 buildings” proposal in 2010; and the “La Aldea Feliz” proposal in 2014. In addition to the concerns described in the CPTN chapter on the need to review the architecture of the pavilion, which serves as a background to the discussions on the subject and the 2012 “Panavisión” proposal; or, finally, the reflections on “life behind the buildings” which is undoubtedly a precedent of the “Prison to Prison” proposal in 2018.

17- In Miguel Fascioli, 2012, Research initiation project: The national pavilion at the Venice Biennale, p. 22.

18- See more: Out There: Architecture Beyond Building, Aaron Betsky, 2008 https:// biennalewiki. Org/?encyclopedia=out-there-architecture-beyond-building

19- Introduction to the LUP exhibition catalog for the XI International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, 2008, page 8. https://issuu.com/miguelfascioli / docs/celestial_body/172.

20- Catalog of the exhibition, CPTN, LUP for the XI International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, 2008, page 153. https://issuu.com/miguelfascioli/ docs/cuerpo_celeste/172

In 2009, was created the commission in charge of designing the School’s strategy for the realization of the Uruguayan submission to the Biennial, as mentioned earlier. The School deanery of Gustavo Scheps selected the Academic Assistant, Luis Oreggioni, and the teachers, Cristina Bausero and Miguel Fascioli, as commission members.

In 2010, the commission raised a report that set the standard Terms of the following contests21 The School council establishes the architect

Salvador Schelotto, Dean Gustavo Scheps, the director of the National Museum of Visual Arts

Mario Sagradini, and the Director of Exhibitions and New Media of the Cultural Center of Spain

Patricia Bentacur as jurors. Bentancur was the first member of the jury to date with curatorial experience. Also, the titular professor Angela Perdomo participated, although she does not appear in the council statement.

The twelfth international architecture exhibition of the Venice Biennale was curated by the architect Kazuyo Sejima who proposed that “people meet in architecture,” The purpose of the proposal was to generate spaces for the exchange of information between architecture and subjects based on physical and conceptual experiences. In the words of Sejima, “a series of spaces instead of a series of objects.” This edition had a greater participation of the universities and the implementation of new schedules of activities such as talks, performances, open debate spaces, and exchange spaces between all the directors of the previous editions.22

The jury selects the proposal “5 narratives, 5 buildings” by Emilio Nisivoccia, Lucio de Souza, Martin Craciun, and Sebastian Alonso. The proposal addressed global themes and problems from the narrative about five buildings in Uruguay. 23 These five buildings were the Palacio Salvo, the Rincón del Bonete, the Pan-American building, the Centenario Stadium, and the Anglo Frigorífico, all of them respond to completely different logic in terms of scale, context, program, language, and technology but with one constant: modern challenges and the relationship with discussions of international relevance.

Through written and graphic pieces, the narratives use diverse resources, such as press releases, literary passages, interviews, different written productions, oral accounts, photographic archives, and graphic collections. The exhibition consisted of an audiovisual montage on five monitors, one for each building, articulated

Curators: Emilio Nisivoccia, Lucio de Souza, Martin Craciun & Sebastian Alonso

5 BUILDINGS, 5 NARRATIVES.

on a large black and white cowhide rug in the center of the space. In addition, some texts that complemented the narrative were placed on the perimeter walls. The curators had the brightness to work in two dimensions, the first an attractive object such as the carpet with the monitors, and the second the opportunity to go deeper into reading with the narratives on the wall and the catalog. Although the proposal does not directly mention the general theme of the Biennial, “people meet in architecture,” it does so intrinsically. It achieves the exchange of information between the visitor and the architecture, in both ways opening the door to multiple dialogues within each of the narratives to capture the attention of those who want to investigate more works of these characteristics. Moreover, it builds an experience, addressing the double approach proposed by Sejima.

The catalog introduces the exhibition with a quote from Manfredo Tafuri on Modern Architecture,24 which offers the reader the complexity of the guiding thread that sews the exhibition together. Then, for each of the works, a brief description is presented, allowing the reader to understand it in its context. It also introduces each work with a battery of black and white images previous to initiating the fragments of narratives corresponding to the work. A notable aspect of this proposal was the subsequent repercussion. The exhibition toured various cultural institutions such as the MNAV, the Atchugarry Foundation, the Museum of Industrial Renovation in the Anglo industry in Fray Bentos, and the Uruguayan Architecture exhibition at the MARQ in Buenos Aires in Argentina.

21- In November 2009, facing the proximity of the twelfth edition of the Venice Architecture Biennale, the Academic Assistant of the culture and extension area, Prof. Arq. Luis Oreggioni, raised a report in which he proposed to the council the creation of a commission that work on the sending of architecture to the National pavilion See files: - Exp 031130006645-09 (Dist 1481/09) Report by Luis Oreggioni; and Exp 031130-006629-10 (Dist 11/10) Second Report by Luis Oreggioni and (Dist 74/10) Approve the Terms for the call for curatorship 2010

22- See more at: https://www.designboom.com /architecture/kazuyo-sejima-people-meetin-architecture/

23- “Exploring and learning from built architecture in the light of a multiplicity of interpretations is the central objective of the exhibition, and for this reason, five narratives

After this edition, the authorities of l ́Giardini called attention to the Uruguayan pavilion for the non-universal accessibility conditions presented. The ramp construction costs 100,000 US dollars, five times the economic value destined for each edition. The high cost is due to three aspects to built in Venice. First, mobility is by water, so moving and bringing the material to Venice Gardens is expensive. Second, because the materials are close to the seawater, the materials are conditioned to be highly resistant to oxidation, and finally, Venice’s construction taxes are incredibly high. This event led to doubt about constructing a new pavilion, which was under discussion due to the need for a significant investment to carry it out; this allows us to ask if the 2012 proposal was based more on fiction or reality.

are presented out of five pieces of architecture located in Uruguay.” Emilio Nisivoccia, Lucio de Souza, Martin Craciun, and Sebastian Alonso, Introduction of the catalog of “5 narratives, 5 buildings”, page 9, (Uruguay, 2010).

24- “modern architecture has meant, firstly, an anticipation ideological or a pure request for principles, and then a technical procedure, inserted directly into the modern processes of production and development of the capitalist world”” Emilio Nisivoccia, Lucio de Souza, Martin Craciun and Sebastian Alonso, Introduction to the catalog of “5 narratives, 5 buildings”, page 9, (Uruguay, 2010).

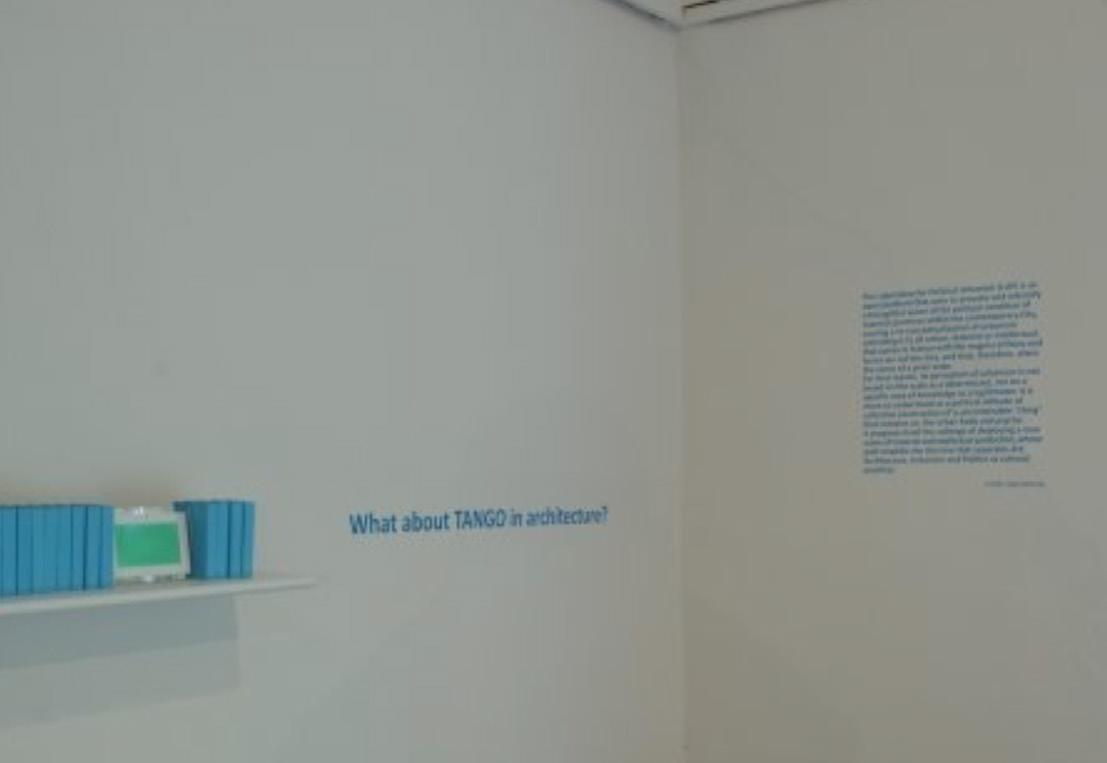

The proposal by Pedro Livni and Gonzalo Carrasco, Panavisión,25 intends to re-position a type of national architecture, meet the need for a pavilion project, transcend the light exhibition box that Uruguay has and cover national commissions with a “quality” architectural space.26 This exhibition fits in precisely with the general theme “Common Ground” raised by David Chipperfield, who sought to “stimulate colleagues to react to professional and cultural trends prevailing in our time” that sought to highlight the importance of influence and the continuity of the architectural and cultural commitment.27 The proposal could be seen as an architectural loop of possible future architecture scenarios within architecture.28

The curatorial team calls six national studios29 to develop a pavilion project for the Venice Biennale. The teams were: Marcelo and Martin Gualano from g+; Horacio Flora and Alejandro Baptista from 11:54 pm; Mario Baez and Adrian Duran from MBAD; Marcelo Bednarik and Federico Mirabal from BM, Diego Perez, Fabio Ayerra, Marcos Castaings, Martin Cobas and Javier Lanza from Fábrica de paisaje; and Matias Carballal, Andres Goba and Mauricio Lopez from MAAM.

These architectural offices, or this “expanded youth” as Diego Capandeguy defined in the preface of the catalog, maintain certain constants such as age, academic activity, commitment to multi-employment (teaching or jobs in the state), the studies (from vertical workshops, of beaux arts origin and the need to “take party”), and the participation in the Montevideo seminar (which

promotes collective and linked works at the regional level). However, the primary resource used is the project, and the sample showed the six possible projects with their corresponding strategies and discussions about the project process. The curators say, “Panavisión must be understood as a place where diverse approaches, tools, concerns, and strategies are currently building the architectural agenda of contemporary production in Uruguay.”

The teams had one month and ten days to complete the project and models. The development of the projects had to yield the spatial condition of working within a volume equivalent to a cube with a 15 m edge, with universal accessibility and respecting a 2-degree slope of the land. Regarding the program, it had to have at least one exhibition room that could be darkened and a storage area equivalent to 4 m2. Also, the model had to respect the scale of 1:25 and a weight of 30 kg, and the expression could be free.

Curators: Pedro Livni & Gonzalo Carrasco

PANAVISION: DIVERSE PRACTICES, COMMON LOOKS

The exhibition consisted of 6 models on the pavilion with an audiovisual montage that showed the processes of the six projects. In addition, the catalog presents each a series of interviews in which the logic and strategies of each office are discussed. Finally, the proposed projects are presented based on diagrams and sketches that show the process and graphics and images that show the final proposal. The curatorial proposal was exhibited at the School of Architecture and the MNAV the following year.

Even though the curatorial proposal reacts to a certain extent to the idea of architecture in a loop, as the curator of the Biennial proposes. It does not do it from a common position but rather from the individual production of each of these architecture offices. How can this specific production show the architectural commitment to society?

On the other hand, the curatorial proposal takes a solid position regarding the architectural project. However, it lacks contemplating on what requirements are essential for the pavilion to operate, without going any further than the need for a restroom so that the people who work in it space do not have to move long distances and could stay in the pavilion and this is essential to make possible the use of original objects, something that could not happen in the 2014 exhibition.

25- “(Panavision) is said to be the lens or mechanism by which panoramic-type format images are obtained.” Pedro Livni and Gonzalo Carrasco in the Catalog of “Panavisión: diverse practices, common views”, page 18, (Uruguay, 2012).

26- “...new pavilion, which from its conception as architecture, not only fulfills its function as a place for the presentation and discussion of the production of the contemporary scene. However, it also manages to transcend the light exhibition box, proposing new ways, forms, and approaches to present the art and architecture created in the south.” Pedro Livni and Gonzalo Carrasco in the Panavisión Catalog: diverse practices, common views, page 18, (Uruguay, 2012).

27- 13 International Architecture Exhibition, Direction: David Chipperfield, Common Ground

https://www.labiennale.org/it/storia-della-biennale-architettura#accordion-9-collapse 28- “What is the common ground of the architecture?”, Gustavo Scheps in the presentation of the Catalog of “Panavisión: diverse practices, common views”, page 15, (Uruguay, 2012).

29- “It is proposed as a mechanism and a platform to present six offices representing a young generation formed in the ‘90s, and that has shown to have a consistent disciplinary practice. The invitation is not to show works but to exhibit their practices. Show personal intuitions, approaches, strategies, ways, and approaches to the architecture project”. Pedro Livni and Gonzalo Carrasco in the Catalog of “Panavisión: diverse practices, common views”, page 18, (Uruguay, 2012).

Rem Koolhaas proposed a straightforward theme, “Absorbing Modernity 1914-2014.” Emilio Nisivoccia, Martin Craciun, Santiago Medero, Mary Mendez, Jorge Gambini, and Jorge Nudelman respond with a proposal that seeks to disseminate modernization in Uruguay in this period, based on 16 different episodes but with a common background, as the introduction to the catalog describes, “(...) the desire to build a world of equals”30 and as Hugo Achugar expresses in his presentation, these episodes or experiences of modernization “(...) do not escape the peculiarity of their dialogue crossed by multiple experiences and temporalities.” 31

La Aldea Feliz,32 presents a set of projects and ideas displayed based on reproductions of images, graphics, and models, on a series of shelves and tables. A catalog in book format complements the exhibition, based on a heterogeneous story; it seeks to analyze the projects in depth and connect them with similar themes to these modernization episodes. 33 The “archive selection” exhibition format is similar to the “Latin America in Construction 195580” exhibition that would be exhibited at MoMA the following year. However, the “La Aldea Feliz” exhibition could not count on the original materials due to the pavilion’s security conditions; instead, reproductions were built. 34

The prologue, “Los Modernos del gran Río” was written by Francisco Liernur, and the epilogue, “Intersections in New York,” was written by Patricio del Real. Both of them were part of the MoMA exhibition, as mentioned earlier (Liernur as a curator and del Real as an assistant). Their participation

shows the communication strategy —in which this team was a pioneer, which would later be a trend— of inviting an international guest to complement the exhibition or, as in this case, the publication.

In addition, the empathic aspect of the reading, which from the introduction marks the strong association with Italy by beginning with a photo of the Italian army brought by an immigrant from 1914 — the year Absorbing Modernity begins—contrasted with an image with a vital spatial component, of children dressed in tunics and bows of the same year. In other words, while Italy was joining the war, Uruguay was trying to build a modernization project. As Francisco Liernur writes in the prologue of the catalog, “A cauldron of fusion from which unexpected answers of different characteristics have emerged but sharing a singular intensity (...)”,35 with the advantage that at this time, the architects had access to positions of authority in the political sphere and public administration.

Curators: Emilio Nisivoccia, Martin Criaciun, Santiago Medero, Mary Mendez, Jorge Gambini & Jorge Nudelman

LA ALDEA FELIZ: EPISODES OF MODERNIZATION IN URUGUAY

In this way, the book presents the 16 episodes as chapters, with a brief description, an analytical text, and a series of photographs and graphics in black and white. The episodes are: 01 “Living Pedagogy”, the relationship between intellectuals and the state, and the renovation of the educational system; 02 “Clinics”, the Surraco project and ideas about the health polis; 03 “Torres García”, art applied to “living machines”; 04 “The Happy Village”, a project by M. Cravotto that articulates the rejection of the metropolis, the claim of the garden city, hygiene and scientific urbanism; 05 “Ranchism” the search for rural housing and the connection with the thought of Cravotto, Gavazzo, Vilamjaó and Torres Garcia; 06 “San Marcos” the connection of Uruguayan architects with Venice; 07 “Punta del Este” experimental laboratory in Latin America; 08 “Rambla Horizontal” the waterfront, its language and the example of the Pan American; 09 “Curtain Wall” and the technological problems of the underdeveloped world; 10 “Planning”, instruments and mechanisms for the transformation of the

Uruguay”, page 23, (Uruguay, 2014).

33-” (...)follow the tracks of some projects thrown into the center of the chaos to try to build a coherent thought that could become a reality. Of these projects, it is worth analyzing their consistencies, measuring the insufficiencies and ingenuousness and following their most intricate ramifications”, Martín Craciun, Jorge Gambini, Santiago Medero, Mary Mendez, Emilio Nisivoccia, Jorge Nudelman, in Introduction of “The Happy Village: episodes of the modernization in Uruguay,” page 9, (Uruguay, 2014).

34- Interview with Emilio Nisivoccia.

35- “Francisco Liernur, “Modernos del gran Río” prologue of “La Aldea Feliz: episodes of modernization in Uruguay,” page 9, (Uruguay, 2014). http://www.fadu.edu.uy/iha/

territory, the example of “the physical equation for development” by G. Gavazzo; 11 “Catholics” the tremendous Catholic production in one of the most secular countries in Latin America; 12 “Cheap houses” the housing crisis, mutual aid cooperatives and the new urban forms of poverty; 13 “Unitor” The influence of Le Corbusier in Serralta; 14 “Caves and Psychedelia” The artificial cavern of Flores Flores; 14 “Heraldos”, the influence of Rossi’s visit and his message on Architecture; 16 “Laguna Garzón”, recent episodes of market intervention on the territory.

The end was crossed by the bibliography of each of the mentioned architects, and the book became an input for future research. After the event, the production was exposed at the MNAV with an 8 m long shelf that included more material and some audio guides that guided the tour based on the stories.36 What would happen if the shelf were permanent?

files/2016/07/ Medero-M%C3%A9ndez-Nisivoccia-Nudelman.-La-Aldea-Feliz.-Episodesde-la-modernizaci% C3%B3n-en-Uruguay.pdf

Reboot,37 means restart and refers to restarting a story, not necessarily following the original story but keeping the essential elements. The proposal intends to restart the dialogue between architecture and the city regarding two stories related to the memory of Uruguay society that —at first reading— do not present a direct relationship with architecture, but —read through Aravena’s slogan— “reported from the front” it presents multiple readings correlated to architecture. It takes two episodes, the Tupamaro National Liberal Movement and the tragedy of the Andes.38

The exhibition consisted of an extension of the field of architecture, an abstract and metaphorical montage of these two episodes, which, as Roberto Fernandez expresses in his essay, reminds us of Joseph Beuys, and his powerful dramatic creations.39 The exhibition space was divided into two areas by a translucent curtain. In the larger space, there was a 60 x 60-centimeter hole on the floor with remains of ground and debris forming a slight slope, and in the smaller space behind the curtain was a print on the walls with sketches of both events and legends such as “We will understand what architecture is when our lives depend on it.”

The exhibition catalog begins with ten manifesto statements of what the exhibition is “not,” such as: “We do not present objects, but instead intangibles.” Ironically, the curatorial team indicates that the exhibition was not designed and executed by editors, translators did not translate it, and academics did not investigate it.40 The catalog was developed in three parts. The first is an Anti-

Architecture Essay,41 written by psychologist and professor Gabriel Galli, that addresses the two events from his media perspective and invites us to think about architecture from spontaneous practices. The second essay was written by Dr. Arq. Roberto Fernandez, entitled “Topography and catastrophe.” Fernandez took both lessons to rethink project action. One called inner-city, linked to the city deep, and the city as a natural topography and inhospitable environment of the political practices of the sixties.42 Another “outer-city,” outside the city, is the place of the catastrophe, in which “shift” predominates and eliminates the spatial transitions of the inner-city (public space and place of different fragments like the ghettos).43

In Marcelo Danza’s text “REBOOT: 2 architecture lessons,” Lesson 1 presents how “being inhabited what makes an object architecture,” analyzes the tragedy of the Andes and the mountain scenery linked to the change of scale, the loss of the urban,

Curators: Marcelo Danza, Miguel Fascioli, Marcelo Starico, Borja Fermoselle, Diego Cataldo y José de los Santos

REBOOT TWO ARCHITECTURE LESSONS

37- Definition of “Restart (fiction)” See more: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reinicio_ (ficci% C3%B3n)#:~:text=Un%20reinicio%20

38- The two events of Those of us who spoke used the invention and construction of real and symbolic space as a fundamental tool as a way of making life viable where it was not possible. These “forced implants” generated unusual restart or reboot conditions for architecture and the city(...)” Marcelo Danza in “Reboot, 2 lessons in architecture, Strangeness” page 125, (Uruguay, 2016).

39- Roberto Fernandez in “Topography and catastrophe” in “Reboot, 2 architecture lessons” page 96, (Uruguay, 2016).

40- “(...) but everything was prepared by a group of friends in a little over a month” Marcelo Danza and Miguel Fascioli in Reboot, page 32, (Uruguay, 2016).

41- “The term Anti-architecture, as I intend to use it here, is inspired by David Cooper’s

the social (although they created community) and the architectural, where the construction of interiority in the frost occurs with the construction of a wall, but not as we know it. However, a wall made with suitcases, with what they had within their reach, they make efficient use of energy, which they saved from the frost. It is what Danza defines as a lesson in architecture.44 Another example, the sleeping bag to resist nights outdoors during the expedition, was another light, portable and efficient architectural device.

Lesson 2 is presented as “the city is infinite and unknown, the Tupamaros and the construction of exteriority in the urban.” The rural guerrilla could not be carried out due to the inability to hide in its nature from the national landscape, so it is carried out as an urban guerrilla. The city is now the nature in which they had to build their place of protection. 45 Montevideo was a place of combat, confrontation, and concealment; they built a new cartography — which was not surveyed for the sample— with new

notion of anti-psychiatry, Nicanor Parra’s anti-poems, the representative anti-folk musical style, for example by Moldy Peach (... ) Paradoxically, it must demarcate any relationship regarding the use that Nikos Salingaros and his collaborators make of the term -anti-architecture- and his crusade against deconstructivism (...)” Gabriel Galli, “Anti-Architecture Essay” in Reboot, pages 40 and 41 , (Uruguay, 2016).

42- Roberto Fernandez in “Topography and catastrophe” in “Reboot, 2 architecture lessons” page 100, (Uruguay, 2016).

43- Roberto Fernandez in “Topography and catastrophe” in “Reboot, 2 architecture lessons” page 96, (Uruguay, 2016).

44- “The success of architecture is guaranteed not by the capacity of spaces to adapt to human activities but by the infinite capacity of the human being to adapt to environmental conditions” Marcelo Danza in “Reboot, 2 lessons in architecture”, page

programs and new paradigms. In these spaces, there was no discussion about the public or the private. The style and its value did not matter, but rather its ability to hide and go unnoticed. They camouflaged themselves not in trees but in the urban masses and divided into autonomous cells so that the fall of one shackle would not generate the fall of the rest.46

This proposal is perhaps with “5 narratives, 5 buildings,” which seeks to generate an exhibition in two dimensions. First, we could say a “near” with an attractive and seductive object, and then we could say a “deep” with a critical thematic depth. Also, the theme presented is undoubtedly proper due to the particularity of looking from a particular outside, as was the plot of the hidden city in the guerrilla or the landscape in the Andes. Although the proposal has a seductive spatiality, it could be confused with the contemporary work of the artist Maurizio Catelán, which puts its authorship on trial.

135, (Uruguay, 2016).

45- “The protection for the guerrillas was the “outside” that the Cubans had in Sierra Maestra and the Colombians in the jungle”, page 142, (Uruguay, 2016).

46- “The success of architecture is guaranteed not by the capacity of spaces to adapt to human activities but by the infinite capacity of the human being to adapt to environmental conditions” Marcelo Danza in “Reboot, 2 lessons in architecture”, page 149, (Uruguay, 2016). https://issuu.com/miguelfascioli/docs/catalogo_issuu_reboot

In 2017, within the framework of the School of Architecture, Design, and Urbanism Magazine in its 15th edition, the School made an open invitation to a discussion panel under the theme “Venice Pavilion, conversations around the Venice Pavilion.” The event took place in the Council Room on August 22 of the same year by the editorial committee of the Magazine and was moderated by Mg. Lic. Magalí Pastorino Rodríguez47 who wrote the article “A look at the Uruguayan pavilion in Venice” for the Magazine.

The dissemination of the event expressed the objective as: “(...) to discuss what has been done in the pavilion and general material for the next call terms.” The guests were: Martín Craciun, Marcelo Danza, Alejandro Denes, Pedro Livini, Emilio Nisivoccia, and Gustavo Vera Ocampo. The architect Carlos Pascual, curator of the shipment of the year 2000, who was also present at the activity, does not appear in this publication. Also, the architect and professor Cristina Bausero, who had acted as a curator in 2006 and was part of the advisory commission in 2009 and 2010 with Luis Oreggioni and Miguel Fascioli, were not invited to the table either.48

Magalí Pastorino’s article approaches the discussion from a psychoanalytic perspective; she identifies the different types of actors that participate without mentioning names and classifies the discussions into “agreements” and “divergences.” The activity itself was carried out in these logics, as defined by Pastorino as “friction together” different fields of force. Although it generates some contributions

DISCUSSION PANEL:

regarding the problem, it does not intend to generate testimony of what happened.

However, the most significant contribution of this article seems to be the conceptual construction of a “cartography” as a kind of map holding all the agents involved and the problems surrounding “the curatorship of Architecture at the Venice Biennale.”

The table was guided by the two key questions that framed the meeting: First, what is the reason, locally and internationally, for having a national pavilion in Venice (taking into account the symbolic, cultural, professional, and academic effects)?; Second, what are the tasks and implications of the curatorial submission of Architecture?

The article includes a series of tension points, with diverse answers and discussions regarding these questions. These points range from the value of the pavilion for the construction of national cultural richness, the “not coincidental” fact that the country has a pavilion, the absence of curatorial discipline

47-Degree in Psychology and Plastic and Visual Arts (Udelar). Master in Psychology and Education (Faculty of Psychology, Udelar). Adjunct professor of the Department of Aesthetics of the IENBA and the Sociocultural Area of the Bachelor’s Degree in Visual Communication Design (Udelar). Research line: aesthetic practices and subjective formations. Author of books and articles.

48- Publication in Patio: http://www.fadu.edu.uy/patio/?p=75077

49-”(...)we do not intend to generate a testimony of what happened, but rather, with courage, we try to open some path in the woods even if you lose (Heidegger) afterward. For this reason, we will not identify the “authors” of what was said for our analysis since we attend to the signifiers and their drifts: misunderstandings, alliances, jokes, and refrains; the party of knowledge, taking the words of Denise Najmanovich.” Magalí Pastorino in the article “A look at the Uruguayan national

“Venice Pavilion, conversations around the Uruguayan pavilion in theVenice Biennale”

Magalí Pastornio and editorial committee of the R15Image of the event taken from R15 Magazine, page 130.

and the simplification of Curatorship to a formal act,51 the dependency economics of otherness (institutions),52 the scope of the exhibition as a deep bibliography, the need to experiment and generate a culture of exhibitions, the exclusivity of its participation53 and the mediatic nature of the commission. The article approaches the panel discussion with a neutral vision of the event, while some positions were essential to review. For example, the conversation around the disciplinary aspect of the Curatorship was the root at which most discussions were developed. The quotes below are taken from the discussion panel in an audiovisual record of the event archived in the School’s audiovisual media service. 54

Martin Craciun, who works as a curator, expressed that in Uruguay, Curatorship is not trained, and submitting an exhibition has the expertise to achieve “(…) a deficiency that exceeds the architectural discipline because it is different, it is another language (...)”. While Carina Strata, Cultural Academic Assistant, opposed expressing the idea that communicating architecture is part of the discipline and deep on it by asking, “(…) How is it communicated in the Biennial, and what is wanted to be communicated? (…)”.

This discussion breaks down into two structural debates, the “what” and the “how” it is shown. The “what” is shown was criticized by Emilio Nisivocioa, who understands that the Biennial is a space for Curatorship and defined it as “Curatorship is not a show like Ford’s, where you will see the latest Fordist production models (...),” to relate it to the need to

incorporate discourses and critical thinking, also by explaining the message regarding the different users who visit the Biennial, that is, “to whom” it is shown. Define who the public is; it would be one of the parameters to define the “what” and the “how.” Nisivoccia identifies different users, first the “biennials” who visit the exhibition quickly and second, the one who searches for a bibliography and sources of information.

Gustavo Vera Ocampo criticizes the lack of local participation “(...) we have not achieved any type of participation instance in the local environment (...) it has remained as something that goes outside and has not finished consolidating a repercussion inside.” So far, activities have been carried out before the Biennale event, like LUP at the MNAV, and after the event, like shows in other museums of most submissions, excluding Reboot. This aspect has been a vital feature of future submissions, such as Prison to Prison (2018 proposal), which was a pioneer in carrying out activities in parallel to the development of the Biennale. Furthermore, this aspect could be reconnected with the “curatorial training” problem that, as Nisivoccia describes well, “(...) we must begin to dialogue and having the possibility of testing, professionalizing and having more experience within us, not like in a workshop, while trying other kinds of practices...” This expression of the desire for “curatorial training” or test space for curatorial practices appears earlier in the statement of the jury of the 2016 edition made up of Emilio Nisivoccia, Patricia Bentancur, and Bernardo Martin those who express: “(...) it would be interesting for the School try to build and

pavilion in Venice” in Revista R15, FADU (Montevideo, 2017) p. 131.

50- Magalí Pastorino in the article “A look at the Uruguayan national pavilion in Venice” in Revista R15, FADU (Montevideo, 2017) p. 131.

51-” (...) as expertise: circulating the voice in English, the foreignness of assembly knowledge stood out more, and this is found in another place that is not the discipline of architecture” Magalí Pastorino in the article “A look at the Uruguayan national pavilion in Venice” in Revista R15, FADU (Montevideo, 2017) p. 132.

52-“(...) Thus, this question generated an emergence of faces, which took the value of the FADU, the Society of Architects of Uruguay, the Municipality of Montevideo, the Ministry of Education and Culture (MEC), from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MRE), from the Friends of the Art Biennial Foundation.” Magalí Pastorino in the article “A look at the Uruguayan national pavilion in Venice” in Revista R15, FADU (Montevideo,

2017) p. 135.

53-” (...) at a work table where the exhibitors were males-adults-whites-people with good manners-etc.” Magalí Pastorino in the article “a look at the national pavilion of Uruguay in Venice” in R15 Magazine, FADU (Montevideo, 2017) p. 135.

54- Venice Pavilion Table, SMA FADU Archive (Montevideo, 2017) 55- Catalog of the LUP exhibition for the XI International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, 2008, page 13. https://issuu.com /miguelfascioli/docs/celestial_body/172

preserve its own exhibition space equipped with adequate infrastructure and supports. In this way, many projects that have not been awarded could be developed in the local environment. In addition, it would allow gaining experience in Curatorship, assembly, presentation, and communication of ideas.” This proposal would undoubtedly help the architecture show become independent of the exhibition design “inherited from the plastic arts,” as Craciun demands at the beginning of the panel. Moreover, Craciun doubts the necessity for “a pavilion,” proposed by Pedro Livni in the 2012 edition, by saying that it could be more appropriate in the local context than in the Venice Gardens. Since this Biennial is not the only one or the most significant, there are other biennials in other places and with other formats, like Chicago, Sao Paulo, or Quito experience.

Another argument that emerged was the foreignness of the jury around curatorial practices; despite the School used to nominate as jury the people who participated in previous editions, they are enough, so others are chosen for their academic or professional expertise, such as Diego Capandeguy, Gustavo Scheps, Bernardo Martin, and Conrado Pintos. In addition, however, they need to gain experience in curatorial practice. Martin Delgado intercedes from outside the panel with two pertinent comments. First, he proposes building a path to achieve automation and building a structure that will last over time, like the architecture trip, allowing us to repeat a model that adapts over time and provides expertise. Secondly, proposes to abandon self-definition and change the question “What is Uruguay’s contribution to the global discussion through the pavilion?” an essential aspect of what would be the Prison to Prison proposal the following year.

proposal “Freespace” by Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara. Also, “proximamente,” in English, means “soon,” selected for the 17th edition, follow the same path. Is it due to a generational shift? Or because both curatorial teams have members who worked with curatorial practices somehow? Are there similarities between the Prison to Prison proposal and the main features discussed on the panel? All these questions require a more historical perspective to approximate an answer, but undoubtedly, there is an evident influence of the discussion panel on the future development of these practices. For this reason, those last two proposals are not included in the period studied.

The Prison to Prison proposes with a solid critical component the expansion of contemporary architectural problems from a specific phenomenon, the prison. It is articulated within the general

These issues are possible to discuss, work on and change. Nevertheless, there is a crucial factor that Pastorino defines as “otherness,” which is the economic and legal dependence on the participation of the School as the managing body of the shipment to the pavilion. According to Strata, “in the Ministry, there is the commission of visual arts, which according to what is designated by law, is for the shipment of arts Biennales. Although the law predates the architecture biennial, it is not updated, and art supplies are doubled compearing to architecture”. This diffused responsibility for the pavilion causes, for example, that it needs a representative Architect in charge of the repairs and a permanent curator who makes possible the continuity of international relationships with the media world of the Biennale. To conclude, considering the curatorial practice is an assemblage of parts and agents articulated in different dimensions. As this essay shows, the lack of legal and institutional frames, economic strategies, and non-practice continuity that allow us to exercise a technical prelude leaves our production in a curatorship without curators. Anyhow, it generates structural instability, which forces those interested in the sociopolitical role of Architecture to ask ourselves: What are the tools and means we can use to build an authentic role of Architecture Curatorship?

- Marcelo Danza and Miguel Fascioli, Catalog of the LUP exhibition for the XI International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, (Uruguay, 2008), https://issuu.com/ miguelfascioli/docs/cuerpo_celeste/172

- Emilio Nisivoccia, Lucio de Souza, Martin Craciun, and Sebastian Alonso, Catalog of the exhibition “5 narratives, 5 buildings”, page 9, (Uruguay, 2010), see more: https://issuu. com/martincraciun/docs /5_buildings_5_narratives

-Miguel Fascioli, Research initiation project: The national pavilion at the Venice Biennale. (Uruguay, 2012)

- Pedro Livni and Gonzalo Carrasco in the Catalog of “Panavisión: diverse practices, common views”, page 18, (Uruguay, 2012).

- Martín Craciun, Jorge Gambini, Santiago Medero, Mary Mendez, Emilio Nisivoccia, Jorge Nudelman, Catalog “The Happy Village: episodes of modernization in Uruguay”, page 19, (Uruguay, 2014).

- Marcelo Danza and Miguel Fascioli, Catalog of the exhibition “Reboot, 2 lessons of architecture” (Uruguay, 2016). https:// issuu.com/miguelfascioli/docs/catalogo_issuu_reboot

- Magalí Pastorino Rodriguez, Article “A look at the Uruguayan Pavilion at the Venice Biennale” in R15 Magazine, (Uruguay, 2017)

- Sergio Aldama, Federico Colom, Diego Morera, Jimena Ríos, and Mauricio Wood in Catalog for the Prison to Priston exhibition, (Uruguay 2018)

- SMA, the archive of the Discussion Panel: “The Venice Pavilion” moderated by Magalí Pastorino Rodriguez within the framework of the R15 in 2017.

- Interview with Emilio Nisivoccia

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND RESOURCES

- Council Resolutions:

- Exp 011150-061431-05 (Dist N 18/06) Selection of Cristina Bausero as curator and (Dist 324/06) It is a report raised by Bausero.

- Exp 031130-001416-08 (Dist 249/08) Internal call to professors for curating, and (Dist 342/08) selection of the proposal by Marcelo Danza.

- File 031130-006645-09 (Dist 1481/09) Report by Luis Oreggioni

- Exp 031130-006629-10 (Dist 11/10) Second Report of Luis Oreggioni and (Dist 74/10) Approve the Terms for the call for curatorship 2010

- Exp 031900-000069-10 Approve the tribunal ruling to “5 narratives, 5 buildings.”

- Exp 031760-004627-11 Dean’s report on the possibility of expanding the pavilion, and (Dist 348/12) Approve the Terms for the call for curatorship 2012

- Exp 031900-000155-12 (Dist. 610/12) Approve the tribunal’s ruling to “Panavisión: diverse practices, common views.”

- Exp 030013-000253-13 (Dist 1213/13) Approve the Term for the call for curatorship 2014.

- Exp 031900-000707 (Dist 37/14) Approve the tribunal ruling to “La Aldea Feliz”

- Exp 031900-000799 (Dist 275/18) Approve the tribunal ruling to “Prison to Prison”

- Official page of the Venice Biennale, History: https://www. labiennale.org/en/history

- Official website of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2015): http://www.mrree.gub.uy/frontend/page?1,inicio,bienal-devenecia,O,es,0,

- PATIO page, FADU: http://www.fadu.edu.uy/patio/?p=40721 and http://www.fadu.edu.uy/sac/exposiciones/venecia-uy/

- La Red 21 press release: https://www.lr21.com.uy/ cultura/13618-uruguay-en-la-bienal-de-arquitectura-devenecia

-biennalewiki.org

-designboom.com/architecture/kazuyo-sejima-people-meetin-architecture/

- wikipedia.org (Definitions and data)