6 minute read

El síndrome de Alicia en el País de las Maravillas y la

El síndrome de Alicia en el País de las Maravillas y la imagen que tenemos de nosotros mismos

La clínica neuropsicológica describe un “síndrome de Alicia en el País de las Maravillas” (SAPM), en el que el sujeto experimenta una serie de distorsiones en la percepción visual que recuerdan las sufridas por Alicia

Las célebres aventuras de Alicia en el País de las Maravillas, del escritor inglés victoriano Lewis Carroll (seudónimo de Charles L. Dodgson), son un ejemplo clásico de “literatura del absurdo” que, bajo el pretexto de su orientación infantil y fantástica, plantean una serie de retos a la lógica y las leyes de la percepción. Como ocurre a menudo, tales desafíos cuestionan y pueden arrojar luz sobre los mecanismos que subyacen a esas leyes.

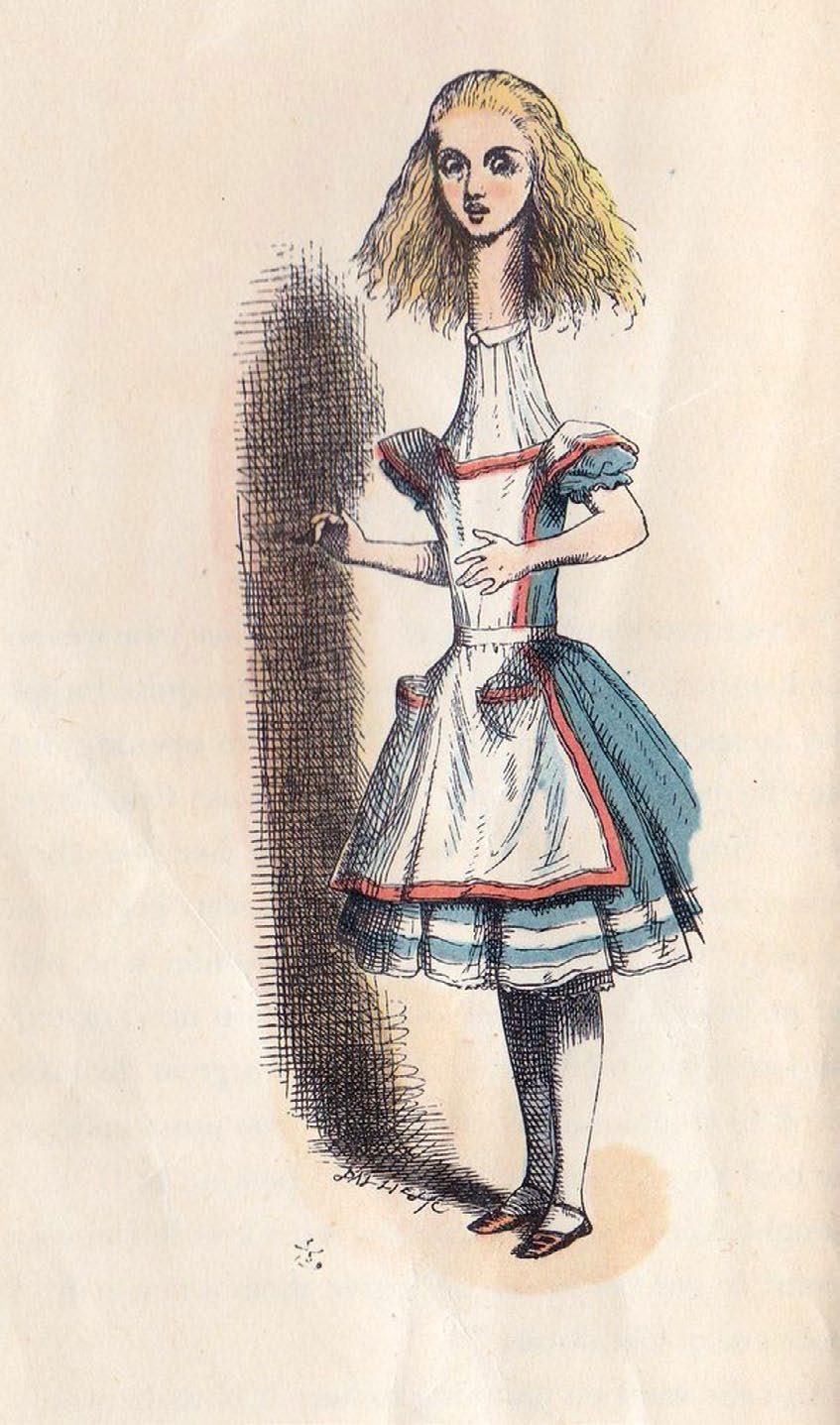

Como recordaremos, Alicia, niña de siete años aburrida en una tarde de verano, sigue a un trajeado conejo por su madriguera (el “rabbit hole”, otro término que se ha convertido en metáfora de digresiones de profundidad insospechada) y pasa por una serie de peripecias entre las que le suceden diversas transformaciones de su tamaño. Primero crece hasta no caber en la casa del conejo (Fig. 1) y luego mengua hasta casi ahogarse en el charco de sus propias lágrimas (Fig. 2).

Más allá de la fantasía, la clínica neuropsicológica describe un “síndrome de Alicia en el País de las Maravillas” (SAPM), en el que el sujeto experimen

1

Prof. Rafael I. Barraquer Oftalmólogo Ophthalmologist

Alice in Wonderland Syndrome and the image we have of ourselves

Under the excuse of fantasy for children or the chliché of being “literature of the absurd”, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland repeated challenges to logic and to the laws of perception in fact question —and at the same time may shed light on— the mechanisms that underlie the way we create the image of ourselves.

As you may recall, one summer afternoon Alice, a bored 7-year-old child, follows a clothed White Rabbit down his rabbit hole (another term that has become a metaphor for digressions of unsuspected depth) and goes through a series of adventures including some in which she undergoes different transformations in size. First, she grows until she’s too big to fit inside the White Rabbit’s house (Fig. 1) and then shrinks so much she nearly drowns in a pool of her own tears (Fig. 2).

Beyond the fantasy, clinical neuropsychology describes “Alice in Wonderland Syndrome” (AIWS) in which the patient experiences episodes of distorted visual perception recalling those suffered by Alice. This includes seeing objects smaller (micropsia) or larger (macropsia) than what they actually are, or they may appear closer (pelopsia) or further away (teleopsia) than they are. Other possible, rarer symptoms involve changes in the perception of all or part of their own body (macro- or micro-somatognosia), colours, the passage of time, movements or other visual hallucinations, including the feeling of a loss of identity (depersonalisation), of being two people at the same time (somatopsychic duality) even seeing oneself “from the outside”.

Figura 1. Alicia creciendo (izquierda) hasta que su cabeza topa con el techo (derecha), en las ilustraciones originales de John Tenniel (1865). Figure 1. Alice growing (left) until her head hits the roof (right), in the original illustrations by John Tenniel (1865).

Figura 2. Izda.: Alicia ha menguado y nada con el ratón en su propio charco de lágrimas (J. Tenniel). Dcha.: Alicia con el tamaño de una taza de té (imagen promocional de la película de Tim Burton, 2016).

Figure 2. Left: Alice has shrunk and is swimming with the Dormouse in a pool of her own tears (J. Tenniel). Right: A teacup-sized Alice (promotional image for the 2016 movie by Tim Burton).

ta una serie de distorsiones en la percepción visual que recuerdan las sufridas por Alicia. Esto incluye ver los objetos más pequeños (micropsia) o más grandes de lo que son (macropsia), o estos aparecen más cerca (pelopsia) o más lejos de lo que están (teleopsia). También pueden darse alteraciones en la percepción de todo o partes del propio cuerpo (macro- o micro-somatognosia), de los colores, del paso del tiempo, de los movimientos u otras alucinaciones visuales, incluso sensación de pérdida de identidad (despersonalización) o de sentirse dos personas a la vez (dualidad somatopsíquica) y verse a sí mismo “desde el exterior”.

El SAPM se asocia ante todo con las migrañas y algunas formas de epilepsia del lóbulo temporal (algo que quizá padeció Lewis Carroll), particularmente en niños. También se ha relacionado con tumores cerebrales, psicosis, ciertos fármacos y alucinógenos, deprivación de sueño, así como procesos víricos que incluyen el inicio de una mononucleosis infecciosa. Todas estas causas producirían una alteración en el flujo sanguíneo de las áreas cerebrales que procesan estos aspectos de la visión. Aunque el SAPM suele ser transitorio y autolimitado, algunas lesiones cerebrales causan cambios permanentes en la percepción, como la prosopagnosia, en la que el paciente es incapaz de reconocer su cara o la de sus conocidos. Por otra parte, esta sintomatología revela que la propia percepción del yo dentro de nuestro cuerpo y la manera cómo juzgamos nuestro aspecto o el tamaño de nuestros rasgos o partes, nada tiene de simple ni directa como podríamos superficialmente pensar. ■

AIWS is mostly associated with migraines and some forms of epilepsy of the temporal lobe (something that Lewis Carroll himself perhaps experienced), particularly among children. It has also been associated with brain tumours, psychosis, certain drugs and psychoactive substances, sleep deprivation as well as some viral processes It may be the first symptom of a beginning infectious mononucleosis. According to the main hypothesis, all these causes would lead to changes in the blood flow of the brain areas that process these aspects of the eyesight. Although AIWS is usually temporary and self-limited, some brain lesions may cause permanent changes in perception, like prosopagnosia, where the patients are unable to recognise their own face or that of their acquaintances. In any case, these symptoms reveal that the way we perceive our self within our body and the way we judge our appearance and the size of our features or other body parts is neither as simple nor straightforward as it might appear on the surface. ■