16 minute read

DESAYUNO CON PAN CALIENTE HOT BREAD FOR BREAKFAST

CAPÍTULO // CHAPTER 2

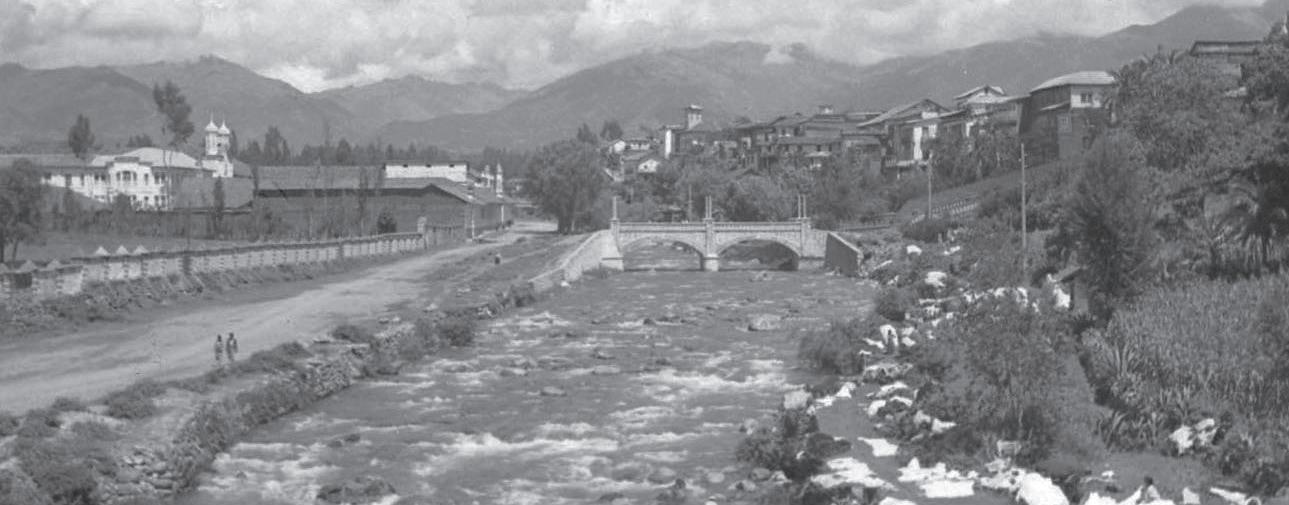

Río Tomebamba, ciudad de Cuenca // City of Cuenca, Tomebamba River

Advertisement

DESAYUNO CON PAN CALIENTE HOT BREAD FOR BREAKFAST

Foto // Photo Felipe Díaz H.

Aquella invitación de Manuel Arturo Cisneros Naranjo hacía referencia al Decreto Supremo número 51, firmado por el presidente de la República, Federico Páez, quien consideraba “que es conveniente al progreso de las industrias del país, la creación de agrupaciones representativas de las mismas, cuya finalidad sea la de impulsar su desarrollo”.

El decreto, firmado el 20 de agosto de 1936 y publicado en el Registro Oficial 271 siete días más tarde, creaba las Cámaras de Industrias “en todas las capitales de provincia y en las cabeceras de cantón, cuyas posibilidades económicas lo requieran”.

Añadía el documento que se considerarían industriales “a quienes The invitation made by Manuel Arturo Cisneros Naranjo referred to Supreme Decree number 51 signed by the President of the Republic, Federico Páez who considered that “it is in the best interest for the progress of all industries, to create associations that will represent them, and their aim must be to promote its development.”

The decree signed on August 20, 1936 and published seven days later in Official Record 271 required the creation of the Chambers of Industries “in all provincial capitals and district seats, in accordance with their economic possibilities.”

The document added that industrial participants were those

se dedican a la producción fabril o manufacturada de artículos destinados al comercio”, de conformidad con muy detalladas especificaciones:

“Propietarios y representantes de fábricas establecidas en el País, de laboratorios químicos, de industrias farmacéuticas y de energía eléctrica; compañías, sociedades cooperativas, sindicatos y talleres dedicados a explotación de yacimientos minero o a la producción de artículos manufacturados, representados por sus gerentes, presidente o por los socios con derecho al uso de la firma social; propietarios o representantes de empresas de transporte terrestre, fluvial y de cabotaje, todos los demás que, según los Códigos y Leyes sobre Industrias, tuvieren el carácter de industriales o manufactureros”.

¿Pero quiénes podían cumplir en las primeras décadas del siglo XX uno o más de esos requisitos en Cuenca? ¿Qué industrias había en una ciudad que, a decir de Guillermo Aguilar, “era tan pequeña que todos desayunaban con pan caliente, recién salido del horno”?

“Aquí nosotros podemos citar desde cosas tan mínimas como la fábrica de hielo. Otra era la fábrica de tejas, si es que industria puede llamarse la fabricación de cosas de barro. También se hacían acueductos en cerámica y servían para conducir sobre todo las aguas de lluvia desde los tachos hasta el piso, no llamaré alcantarillados porque en esa época no había tales”, señala el doctor Aguilar y agrega:

“Más que industrias eran artesanías, pero que suplían lo que después se vino a completar con cosas industriales”.

El exvicepresidente del Ecuador Alejandro Serrano añade que “se fabricaban jabones, había una jabonería muy elemental de un señor Terreros recuerdo yo, había una fábrica de baldosas muy pequeñas del señor Roberto Crespo Ordóñez, en fin, ese tipo de productos para auto-consumo, entendiendo por auto-consumo no individual, ni familiar, sino citadinamente”. “who were dedicated to the production of manufactured articles destined for commerce” and they had to fulfill certain requirements:

They had to be “owners and representatives of factories within the country that were dedicated to any of the following: chemical laboratories, pharmaceutical industries and electric energy, companies, cooperative societies, unions and workshops dedicated to mining or to the production of manufactured articles, represented by their managers, presidents or legal partners.” They could also be “owners or representatives of ground, water or coastal transportation and all other transportation enterprises that according to Industrial Codes and Laws would fall into the description of industry or manufacturing.”

But who in Cuenca, during the first decades of the Twentieth century, could fulfill any of those requirements? What industry was there in a city that, as Guillermo Aguilar said “was so small, that for breakfast everyone could have hot bread out of the oven”?

“It should be mentioned that there did exist a handful of tiny factories such as the ice plant. Another was a roofing tile factory, if one can call the manufacture of things made of clay a “factory.” There was also a factory that made ceramic drains whose purpose was to conduct rainwater. I don’t believe they could be considered parts for a sewer system because sewers did not exist at that time,” says Dr. Aguilar, who adds:

“More than industries, they were workshops that manufactured handmade items that were later supplemented by industrially produced goods.”

Ex vice-president Alejandro Serrano adds that “there was also rudimentary soap manufacturing, I remember a Mr. Terreros who owned a very basic soap factory, and Mr. Roberto Crespo had a workshop for making tiny floor tiles. The production of these goods was just enough to supply local consumption.

“Cuando yo era niño –escribió cinco años atrás Frank Tosi para la publicación conmemorativa de los 70 años de la Cámara de Industrias- Cuenca no tenía industria con excepción de la pequeña fábrica de baldosas de Don Roberto Crespo Ordóñez que era presidente de la Cámara de Industrias. Había la Pasamanería de mi padre y había un tiempo la Textil Azuaya que después le compró la Pasamanería”.

El historiador Juan Cordero relata que “ocasionalmente empezaron a implantarse pequeñas industrias. Industrias por ejemplo de la cerveza, de las bebidas gaseosas, de la madera, industrias de textiles”.

En el libro La Industria Regional. Azuay, Cañar y Morona Santiago a 1981, José Cuesta Heredia y Luis Araneda Alfero indican que el período de 1924 a 1959 (que ellos llaman “primario”) se caracteriza por la casi inexistencia de establecimientos industriales en la región.

“When I was a child – wrote Frank Tosi five years ago for the commemorative publication of the 70th anniversary of the Chamber of Industries- Cuenca did not have much industry except for the floor tile factory owned by Mr. Roberto Crespo Ordóñez who was the President of the Chamber of Industries at that time. My father owned a narrow fabrics factory, and for a period of time there was Textil Azuaya, a factory that he later bought.”

Historian Juan Cordero relates, “Occasionally very small industries started forming. There were industries that produced beer, soft drinks, wood products and textiles.”

In the book Regional Industry: Azuay, Cañar and Morona Santiago in 1981, José Cuesta Heredia and Luis Araneda Alfero state that the period between 1924 to 1959 (which they call “primary”) is characterized by the relative lack of industrial establishments in the region.

Roberto Crespo Ordóñez Foto // Photo Felipe Díaz H.

Los autores describen la fisonomía económica de aquellas décadas basándose en cuatro características: bajo nivel de producción, escasa o ninguna utilización de tecnología, relativa inexistencia de un sistema financiero-bancario y ausencia de tradición empresarial.

Cuesta Heredia y Araneda Alfero hablan de 27 establecimientos industriales en este período, orientados fundamentalmente a la producción de bienes destinados al mercado interno, sin incluir en esta dinámica a la industria exportadora de sombreros de paja toquilla.

“La incomunicación vial acentuó aún más la deprimente realidad socio-económica descrita; añadiéndose el déficit energético y la secular desvinculación de la región con los centros de poder político y económico”, agregan los autores.

La economía giraba por aquellos años en torno a la producción agrícola, una producción que era de autoconsumo: la ciudad consumía todo lo que se producía en los campos.

Ni siquiera la principal actividad económica de la región, y una de las principales actividades exportadoras del país, pudo romper este aislamiento, como lo describe la historiadora María Cristina Cárdenas Reyes en su ensayo El Azuay en la sociedad nacional de los años 30, publicado en 2007 como parte de un Encuentro Nacional sobre Historia del Azuay.

“Si bien se aprecian cambios paulatinos en las relaciones económicas y sociales del agro azuayo (en los años 30), se mantiene la falta de comunicaciones, y especialmente de ferrocarriles, para integrarse más activamente con todas las otras regiones del país. En el centro-sur ecuatoriano continúa aislado y la exportación taquillera no modificará la situación”.

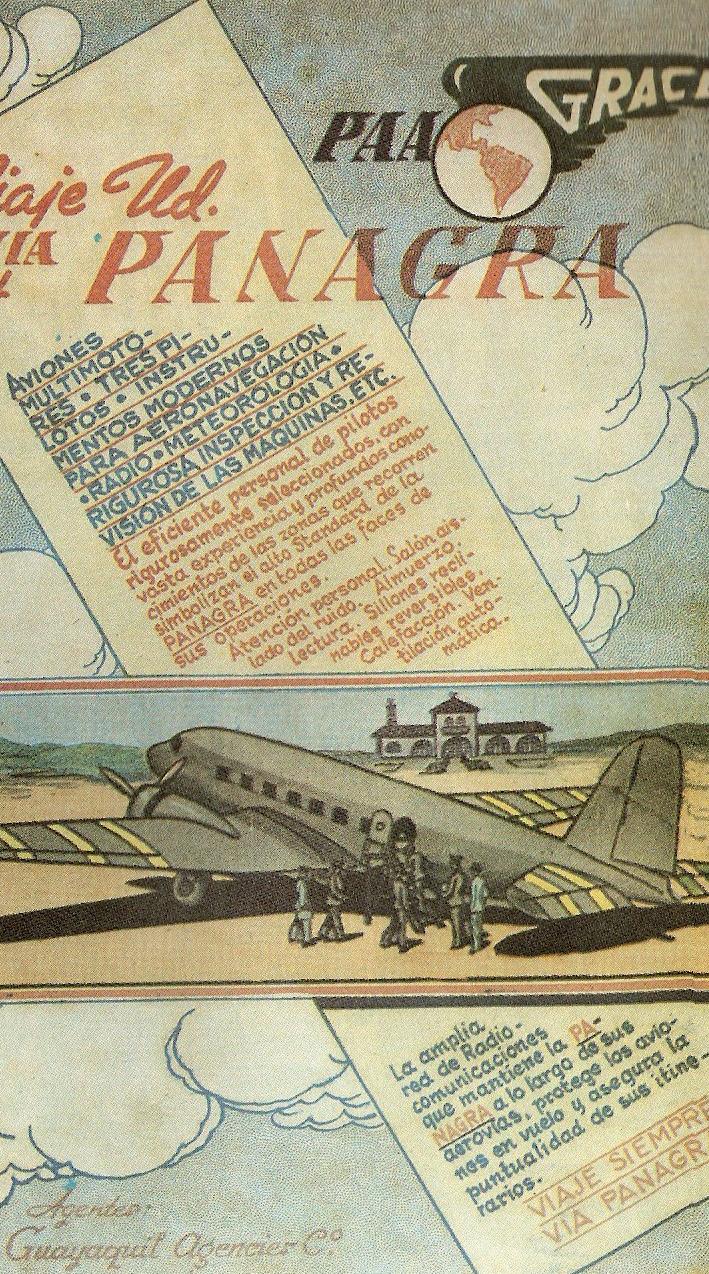

Kurt Heimbach, cuya familia llegó al Ecuador en 1938 huyendo de la Alemania nazi, recuerda que hasta que Panagra –la línea aérea que cubría mitad de página en aquella edición de El Mercurio del 8 de septiembre de 1938- no llegó a Cuenca, “era These authors describe the economic situation during those decades by referring to four characteristics: a low level of production, little or no use of technology, incipient existence of a financial-banking system and lack of entrepreneurial tradition.

Cuesta Heredia and Araneda Alfero talk about 27 industrial establishments formed during that period that were mostly oriented to the production of goods destined for local consumption, they did not include the paja toquilla hat industry.

“Poor access to the region was an added stress to the depressive socio-economic situation of the region, as well as the region’s deficient power supply and age-old isolation from the country’s political and economic centers,” add the authors.

It was a period in which the economy revolved around local agricultural production; the city consumed everything that was produced in neighboring fields.

Neither the main economic activity of the region, agriculture, nor one of the country’s principal export activities, was able to alleviate the region’s isolation. Historian Maria Cristina Cárdenas describes in her essay “Azuay, in Ecuador’s society of the 30’s” published in 2007 as part of the “National Encounter on the History of Azuay”:

“Although gradual economic and social changes were taking place in the agriculture of Azuay in the Thirties, the absence of communications and railroads remained the same, thus hindering any kind of integration with the rest of the country. The southerncentral region of Ecuador was still isolated and the export of paja toquilla did not change the situation.”

“Kurt Heimbach, whose family came to Ecuador in 1938, escaping Nazi Germany, remembers that before Panagra (the airline whose advertisement occupied half a page in El Mercurio on September 8, 1983) started operating in Cuenca “it was very hard to develop industry.”

sumamente complicado hacer industria”.

“Al principio viajar a Guayaquil, era un bus al Tambo y de ahí en tren. Más o menos ir a Guayaquil significaba dos días. A Quito no recuerdo yo cómo”, rememora quien fuera el octavo presidente de la Cámara de Industrias (1976 y 1977).

El avión como método de romper este aislamiento ya había sido anticipado por el poeta Remigio Crespo Toral el 4 de noviembre de 1920 cuando asistió a la llegada del Telégrafo 1, la primera aeronave en aterrizar en Azuay.

Como recuerda Alberto Cordero Tamariz en su artículo Una Hazaña Increíble, publicado en el tercer tomo de la Historia de Cuenca, el poeta hizo un discurso en el que auguraba que “la aeronavegación sería acaso el porvenir de la raza humana y el único modo de redención de Cuenca porque ‘A los cuencanos no nos queda otro camino que el del cielo’”.

Panagra tampoco fue el fin de los problemas para movilizarse, como podemos deducir de este fragmento de la entrevista que le hizo Andrea Heimbach a Adela Payró, esposa de Alfredo Peña, recordando su primera llegada a la ciudad (ella había nacido en Estados Unidos, de padres mexicanos, y se casó a mediados de la década del 50 con el creador de Vanderbilt, Tugalt, Graiman -entre otras- en Nueva York)

“Llegamos a Guayaquil, después de un largo viaje, y por si fuera poco tuvimos que esperar 4 días más para viajar a Cuenca, ya que la única compañía que había, Panagra, una compañía gringa, en ese tiempo no tenía radar y el clima no era óptimo para volar, pero en realidad preferí esperar porque si hubiera viajado por carretera creo que me hubiera decepcionado mucho”.

Esta clase de “decepciones viales” sería uno de los obstáculos más difíciles de enfrentar para los industriales de la ciudad en las primeras décadas del siglo XX y en más de una ocasión le costarían a la ciudad muy buenas oportunidades de negocios. “Early on, traveling to Guayaquil meant taking a bus to El Tambo and a train from there to the Coast. It took about two days to travel to Guayaquil. I can’t even remember how we ever got to Quito,” recalls the eighth President of the Chamber of Industries (1976 and 1977).

The poet Remigio Crespo Toral had already anticipated air travel as a means to alleviate the region’s isolation on November 4, 1920 while present at the arrival of Telegraph 1, the first airplane to land in Azuay.

Alberto Cordero Tamariz remembers in his article “An Amazing Feat” published in the third volume of Historia de Cuenca, that the poet made a speech in which he envisaged that “aeronavigation would be the future of the human race, and the only way for Cuenca’s redemption, since “the only road out of Cuenca leads to heaven.””

The presence of Panagra, however, did not solve mobility problems, as seen in a fragment from the interview that Andrea Heimbach had with Adela Payró, wife of Alfredo Peña. In it she recounts the first time she traveled to Cuenca (she was born in the United States from Mexican parents, and married the founder of Vanderbilt, Tugalt and Graiman –among other companies- in the mid 50’s in New York).

“We arrived in Guayaquil after a very long trip, and then we had to wait four more days to travel to Cuenca since the only company, Panagra, which was a gringo company, did not have radar capability and the weather was not optimal for flying. I’m glad I waited though, since the other option was going by land and I’m afraid I would have been extremely disappointed.”

These “transportation inconveniences” were the hardest obstacles for the industrial leaders of Cuenca to face during the first decades of the Twentieth Century. Sadly, on more than one occasion they were the reason business opportunities knocked elsewhere.

“At one point there were efforts to start a very interesting

“Aquí se trató de poner una industria interesantísima que era la del vidrio y botellas. Porque acá muy cerca, en el Oriente, hay la mina de la materia prima. Pero en aquella época, los inversionistas –que eran extranjeros- vieron que la vajilla sí se podía transportar, con riesgos de las malas carreteras, pero ya los productos de vidrio no”, ejemplifica el doctor Serrano, quien fue presidente ejecutivo de la Cámara de Industrias.

“Las limitaciones están bien claras –dice el economista Carlos Crespo- faltaban comunicaciones, insumos, electricidad, bueno, de todos nos faltaba para hacer industria. En Quito está la política, está el mercado; en Guayaquil, el puerto; y aquí en Cuenca estábamos aislados”.

“Pero precisamente esto que es un factor limitante, ha sido un factor de esfuerzo que ha dado lugar a una mejor actitud. A una actitud de sacrificio y de saber valorar el trabajo que se realiza en la zona y que ha sido lo que ha hecho de Cuenca”.

Publicidad de Panagra // Panagra Advertisement Foto // Photo Felipe Díaz H. enterprise that consisted of manufacturing glass and bottles; the raw material would have been brought from a mine in the Oriente not far from the city. At that time, the investors, who were all foreigners, realized that, although most ceramic products could be transported, albeit with a certain amount of risk, glass products were much too delicate to survive the terrible road conditions,” says Dr. Serrano, past Executive President of the Chamber of Industries.”

“The limitations were very clear,” mentions Economist Carlos Crespo, for Cuenca had a dismal lack of communications, raw material and electricity. Indeed there were many factors absent in order to develop any kind of industry. Quito had politics (government) and the market, Guayaquil had its port; in Cuenca we were isolated.”

“It just so happens, however, that this limitation has been the reason the people have always been ready to make an extra effort, which in turn has developed a better attitude. It’s an attitude of

“Cuando se hace una industria en Cuenca, se hace bien. No es una industria cualquiera, es una industria bien pensada, es una industria bien desarrollada, Porque no nos queda otra alternativa. Con muchas limitaciones, pero Cuenca tiene su gente”, agrega quien fue el noveno presidente de la Cámara y el segundo en ocupar el cargo en dos ocasiones (1978-1979 y 1982-1983).

En eso coincide Roberto Maldonado, fundador de Colineal y vicepresidente del Directorio de la Cámara de Industrias: “Yo creo que esas dificultades que han tenido los cuencanos han hecho que su trabajo tenga que ser más duro para quitar esas dificultades del camino, e igualarnos a las empresas que hay en Quito y Guayaquil”.

Para Augusto Tosi, presidente actual de la Cámara de Industrias, el aislamiento “ha sido una gran ventaja competitiva porque nos obligó a ser creativos, a ser mejores empresarios, a sobrevivir en un entorno difícil”.

Pietro Tosi, padre de Augusto y e hijo de uno de aquellos hombres reunidos en el tercer piso del Banco del Azuay en 1936, destaca por sobre todas las cosas el espíritu de trabajo.

“Cuenca no tuvo carreteros sino hasta 1949, que se abrió hacia el norte. Y hacia la costa fue todavía después. En cambio, la gente es capaz, es dedicada y se podía trabajar, y trabajar bien”.

Otro de los hijos de aquellos padres fundadores, Eduardo Ugalde, remarca la actitud de su padre Nestorio y sus colegas.

“En primer lugar tenían que ser muy valientes, porque empezaban prácticamente sin ningún tipo de apoyo. Eran verdaderos ejecutores, gente que se dedicaba a hacer su trabajo e iban contra todas las vicisitudes del caso, peleando por lo que ellos estaban tratando de forjar”. sacrifice and of appreciation for the work done in the region, this attitude is what has turned Cuenca into what it is today.”

“An industry in Cuenca is an industry well created. It’s not just randomly thrown together; it is well thought out and developed because there is no other option. Cuenca may have many limitations, but it has its people,” added the ninth President of the Chamber of Industries and the second one to be reelected for two periods (1978-1979 and 1982-1983).

Roberto Maldonado, founder of Colineal and current vicepresident of the Board of Directors of the Chamber of Industries, coincides with him: “I believe that the difficulties Cuenca’s citizens have had to face have made them work even harder, making their enterprises as good as those in Quito and Guayaquil.”

For Augusto Tosi, current President of the Chamber of Industries, the isolation “has been a great competitive advantage because it has forced us to be creative, to be better entrepreneurs and to survive in a difficult environment.”

Pietro Tosi, father of Augusto and son of one of the men gathered on the third floor of the Bank of Azuay in 1936, highlights the spirit of work above all else.

“Cuenca did not have highways until 1949, and the first to be built led north. Roads to the coastal region were opened later, but the people of Cuenca are capable and dedicated, so it was possible to work, and to work well.”

Another of the sons of those founding fathers, Eduardo Ugalde, highlights the attitude of his father Nestorio and his colleagues.

“First of all they were brave; it was not easy to venture into new territory without any type of support. They were true doers. They were people dedicated to their work, committed to overcoming any and all obstacles, and they fought for their convictions.”