8 minute read

AN AIRPLANE IN THE HEAVENS AND A BANK SECURELY ON THE GROUND

CAPÍTULO // CHAPTER 5

Autógrafo de Elia Liut a Roberto Crespo Ordóñez // Elia Liut autograph to Roberto Crespo Ordóñez

Advertisement

UN AVIÓN POR LOS AIRES Y UN BANCO CON LOS PIES EN LA TIERRA AN AIRPLANE IN THE HEAVENS AND A BANK SECURELY ON THE GROUND

Foto // Photo Felipe Díaz H.

Un año antes de prenderse la primera lámpara en Cuenca, en 1913, se funda el Banco del Azuay, la primera entidad bancaria de Cuenca.

Roberto Crespo Toral, meses antes de convertirse en el hombre que trajo la luz a la ciudad, asume como gerente de la institución junto con Octavio Vega. In 1913, one year before the first street light came on in Cuenca, the first banking entity of the city, Banco del Azuay, was founded.

Before he was known for bringing power to Cuenca, Roberto Crespo Toral was named manager of the bank along with Octavio Vega.

“La economía era bastante reducida. Ventajosamente se fundó el Banco del Azuay y fue un motor muy importante para esta economía, por pequeña que sea. De alguna manera satisfacía los requerimientos mínimos de esta población de unos 30, 40.000 habitantes”, recuerda hoy el exvicepresidente Serrano.

En sus Notas sobre la vida de un banco, rescatadas en el libro La Historia de Cuenca, el autor Jorge Dávila Vázquez señala que “la historia del Banco del Azuay está íntimamente ligada a la del desarrollo social y económico del Ecuador. La intención primera al fundarse la Entidad fue orientada al Austro, en el terreno de las inversiones de capital y en el manejo de los fondos que producían”.

“La mentalidad característica en los diferentes períodos fue casi siempre la misma: impulsar el aspecto financiero, sin descuidar el lado humano; auspiciar la empresa, ya en el plano público, ya en el privado, sin olvidar jamás que detrás estaba el hombre”, concluye Dávila Vázquez.

Banco del Azuay Foto // Photo Felipe Díaz H. “Cuenca’s economy was quite limited. Fortunately, once the Banco del Azuay was founded, it became a driving force for the economy, albeit a small one. In a way, it met the minimum requirements of the 30 or 40,000 citizens of Cuenca,” recalls former vice president Serrano.

In his “Notes on the Life of a Bank” compiled in the book The History of Cuenca, the author Jorge Dávila Vázquez points out that “the history of the Banco del Azuay is intimately linked to the social and economic development of Ecuador. When the bank was founded, its primary market was oriented to the southern region of the country. It would operate in capital investments and management of the funds produced.

“The philosophy of the bank during different periods was almost always the same: to promote the financial areas while being careful not to neglect the human factor, and to sponsor the enterprise publicly and privately without forgetting that behind all of this

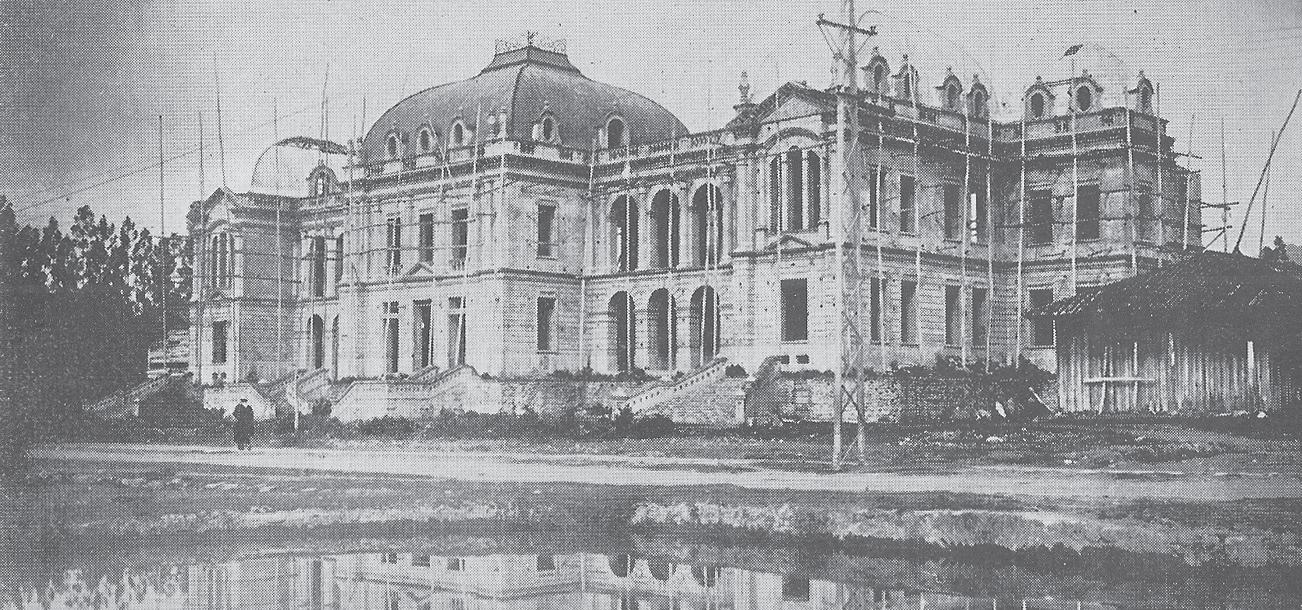

Construcción del Colegio Benigno Malo // Construction of Benigno Malo School Foto // Photo Felipe Díaz H.

Otro de los artículos de La Historia de Cuenca sobre este banco añade que “obras de infraestructura básica para hacer de Cuenca una ciudad moderna y bien servida tuvieron, tras generaciones, el apoyo del Banco del Azuay; redes telefónicas, agua potable, alcantarillado, luz eléctrica, pavimentación y asfalto, que de otra manera no habrían sido financiables”.

“La construcción de monumentales edificios como el Colegio Benigno Malo, la Casa de la Cultura, el de la propia I. Municipalidad, el hospital Neumológico, antigua L. E. A. (Liga Ecuatoriana Antituberculosis), fueron posibles gracias también a la nunca bien reconocida intervención crediticia del Banco del Azuay, para enumerar unas cuantas de las muchas empresas públicas y privadas que consagraron sus inicios a este su Banco”.

Décadas después, hablando de la época dorada de esta institución, Teodoro Jerves, el cuarto presidente de la Cámara de Industrias was a person,” concludes Dávila Vázquez.

Another article in The History of Cuenca concerning this bank states that “for generations, the Banco del Azuay, helped finance the basic infrastructure that turned Cuenca into a modern and well served city. It supported the implementation of telephone networks, water supply, sewage, electricity, paving and asphalt, whose funding, otherwise, would not have been viable” says Dávila Vázquez.

“The construction of monumental buildings like the Benigno Malo School, the Casa de la Cultura, the Municipality, the Hospital for Respiratory Diseases (formerly L.E.A.), was possible thanks to credit given by the Banco del Azuay, though at the time this fact was not well known. These are just a handful of the numerous public and private enterprises that owed their beginnings to the bank, to their bank.”

(1969 y 1970), resaltaba que esta entidad bancaria “no solamente ayudaba a los pequeños o grandes industriales y comerciantes, sino también a los pequeños y a los mínimos, e incluso daban préstamos de consumo”.

Pero en aquella segunda década del siglo, el arribo de la luz eléctrica y la fundación del primer banco de la provincia no eran los únicos cambios que deslumbraban a los pobladores de esta metrópoli, como escribe el historiador Diego Arteaga en su libro Cuenca y sus Gentes.

“Las cada vez más frecuentes obras de canalización de varias zonas de Cuenca ya no permitía el lavado de la ropa en las inmediaciones de los hogares: la población tenía que volcarse hacia los ríos; las funciones cinematográficas eran mucho más atractivas que las procesiones religiosas o los espectáculos públicos; la tranquilidad del transeúnte también se vería afectada con la llegada del primer automóvil a Cuenca en 1917, y los cielos se vieron perturbados tres años más tarde, por el Telégrafo I, el primer avión que sobrevoló Cuenca”.

En ese famoso día de noviembre de 1920, también estuvo involucrado un futuro presidente de la Cámara de Industrias de Cuenca e hijo de Roberto Crespo Toral, como lo recuerda Alberto Cordero Tamariz en su artículo Una Hazaña Increíble.

“En medio del entusiasmo que reinaba en la colectividad por el Tres de Noviembre, en la mente de dos cuencanos surgió la idea de rodear de mayor pompa la celebración, con un número acaso imposible, que lo mantenían en reserva, cual era el vuelo de un avión que realizaba mil proezas en la ciudad de Guayaquil por primera vez”.

“Sus promotores, Luis Cordero Dávila y Roberto Crespo Ordóñez querían que fuera una sorpresa; pero guardaban el temor de su fracaso, pues, no podían concebir que un ser humano, en una pequeña nave, pudiera venir por los aires remontándose sobre la cordillera de los Andes, emulando la grandiosidad de los cóndores nacidos ya para el vuelo”. Some decades later, and in reference to the “Golden Era” of this institution, Teodoro Jerves, the fourth President of the Chamber of Industries (1969 and 1970), highlighted that this bank “not only helped large industry and commerce, but also small and tiny businesses. They even gave loans for personal use.”

In that second decade of the century, the arrival of electricity and the establishment of the first bank were not the only changes that dazzled the citizens of this city, writes historian Diego Arteaga in his book Cuenca and Its People.

“The new underground drainage system in various parts of the city did not allow for washing clothes in the vicinity of the homes as was done traditionally; people had to use the rivers, and cinemas were much more attractive than religious processions or public shows. A quiet stroll through the city would be disturbed by the arrival of the first automobile in 1917, and the sky would be darkened three years later by Telegraph I, the first airplane to fly into Cuenca.”

On that famous day, in September 1920, one of the future presidents of the Chamber of Industries and son of Roberto Crespo Toral was also present, recalls Alberto Cordero Tamariz in his article “An Amazing Feat.”

“In midst of the enthusiasm that reigned in the community for the November 3rd commemorations, an idea formed in the minds of two citizens that would heighten the grandiosity of the celebration—something that, until then, had remained a secret. This act would be seemingly impossible. For the first time, they would bring an airplane to Cuenca that had performed a thousand feats in the city of Guayaquil.”

“Their promoters, Luis Cordero Dávila and Roberto Crespo Ordóñez, had wanted it to be a surprise. They kept their fear of failure secret, for they could not conceive that a human being, in such a small plane, could ascend above the Andes Mountains as if emulating the great condors who naturally were born to fly.”

Primeros vehículos de la ciudad // First vehicles of the city Foto // Photo Felipe Díaz H.

Roberto Crespo Ordóñez, segundo presidente de la Cámara de Industrias de Cuenca, había conocido al piloto italiano Elia Liut en Guayaquil y junto a Cordero Dávila lo convenció de atravesar Los Andes. Vuelo que no se concretó por cuestiones climatológicas el 3 sino el 4 de noviembre.

No existe tanta información sobre el primer automóvil que paseó por la ciudad, pero veinte años después de su llegada, el parque automotor no se había incrementado demasiado en Cuenca, como lo refleja esta anécdota contada por Kurt Heimbach:

“El transporte era un capítulo aparte. Imagínese que mi padre fue el primero que tuvo licencia profesional. La licencia número uno”.

“Había unos seis o siete vehículos en Cuenca. Nosotros le compramos el vehículo a otro industrial que tenía una fábrica aquí. Había licencias, pero no sabían distinguir entre amateur y profesional, así es que a mi padre le dieron profesional”. Roberto Crespo Ordóñez, second President of the Chamber of Industries of Cuenca, had met the Italian pilot Elia Liut in Guayaquil and, together with Cordero Dávila, convinced him to cross the Andes. That flight did not take place on November 3rd, but on the 4th, due to unfavorable weather conditions. Twenty years after the arrival of the first car to Cuenca, the number of cars had not increased much as reflected in this anecdote told by Kurt Heimbach:

“Transportation was another thing altogether. Just imagine that my father was the first person to have a professional license! License number one!”

There were six or seven automobiles in Cuenca. We bought our car from another businessman who had his factory here. They issued licenses, but they did not know how to distinguish between an amateur and a professional. So my father was issued a professional one.”