10 minute read

Api e vite: un connubio che sa di antico e di futuro

IL MESTIERE DEI CAMPI E DELLA CANTINA THE ART OF CULTIVATION AND OF THE CELLARS

BEES AND VINES: A MARRIAGE WITH FLAVOURS OF THE PAST AND THE FUTURE

Advertisement

di Mario Bagnara

Già Plinio anticipò uno dei princìpi dell’ecologia moderna: “Ubi apis ibi salus” Pliny anticipated one of the principles of modern ecology: “Ubi apis ibi salus”

Agricoltura biologica, biodiversità ambientale, agroecolo- Organic farming, environmental biodiversity, agro-ecolgia e quindi viticoltura biologica… sono termini sempre ogy and hence organic viticulture… these are increaspiù ricorrenti nella comunicazione formativa e giornalisti- ingly common subjects in training for winemakers and ca, corrispondenti a concrete attività di molti produttori in in journalism, which reflects the increased activity in risposta anche alle crescenti richieste dei consumatori, in- this field on the part of many wine producers, Masi Agclusa Masi Agricola nel settore vitivinicolo. Fra le strate- ricola included, in response to growing demands from gie ecoambientali sempre più curata nei vigneti è l’api- consumers. Among the eco-environmental strategies coltura, un innovativo abbinamento agrosistemico cui, increasingly seen in vineyards is beekeeping, an innonel gennaio 2019 a Villa Bassani Brenzoni a Sant’Ambro- vative agricultural partnership which was the subject of gio di Valpolicella, Confagricoltura Verona e l’Associazio- an ad-hoc conference held by Confagricoltura Verona ne apicoltori veneti hanno dedicato un convegno ad hoc. and the Venetian Beekeepers Association at Villa BasBen chiare le motivazioni per cui le api, fattore determi- sani Brenzoni in Sant’Ambrogio di Valpolicella in January nante della salute ambientale, sempre 2019. Bees are an essential factor in più sono coltivate nei vigneti: già Plinio environmental health and the reasons il Vecchio, con la frase “Ubi apis ibi sa- L’apicoltura why hives are an increasing part of lus”, l’aveva intuito. La loro impollina- è una delle strategie the vineyard make-up are clear. Pliny zione infatti apporta alle viti gli aromi caratteristici di un vino, derivanti dal- più valorizzate the Elder knew this when he coined the phrase “Ubi apis ibi salus”. In fact, le erbe, dai frutti e dai fiori dei dintor- dell’agricoltura ‘green ’ the pollination that comes from bees ni, meglio se coltivati addirittura tra i Beekeeping gives the vines the characteristic arofilari. L’uva poi restituisce alle api il favore ricevuto, fornendo il resveratrolo, un efficace antiossidante che ne allunis one of most highly valued strategies mas of a wine, deriving from the vegetation and flowers of their surroundings, preferably grown between ga l’esistenza. Di fronte a tale connubio of ‘green’ agriculture the vineyard rows. The grapes then tra ape e vite viene spontaneo ripensa- return the favour to the bees by pro-

Pagina precedente. Miele di acacia Serego Alighieri vuol dire natura e semplicità Preceding page. Serego Alighieri acacia honey means nature and simplicity

Affascinante e meraviglioso il lavoro delle api, da cui traiamo miele e cera Fascinating and incredible, the work of bees to bring us honey and wax

Le arnie tra i vigneti sono sempre più diffuse in Valpolicella Hives are more and more common in Valpolicella vineyards

re alle fonti storiche dell’apicoltura, conosciuta e praticata, viding resveratrol, an antioxidant that prolongs their exin base a precise testimonianze grafico-rupestri e lettera- istence. Depictions of beekeeping can be seen in rock rie, già a partire da alcuni millenni a.C. in Spagna, in Afri- paintings and documentation dating back thousands of ca (Egitto e Zimbabwe), nei paesi mesopotamici e me- years in Spain, in Africa (Egypt and Zimbabwe), in Mesdiorientali, a Creta e quindi ben documentata soprattutto opotamia and the Middle East, including Crete and the nelle letterature classiche: per quella greca, in primis da classical world. Aristotle’s comments on the subject were Aristotele, seguito poi in età ellenistica da vari scrittori la followed in the Hellenistic age by various authors whose cui produzione, benché tutta perduta, è stata fonte pre- own works have been largely lost but who inspired Latin ziosa per gli autori latini da Varrone a Virgilio, al citato Pli- authors from Varro to Virgil, and Pliny himself, who died nio, morto durante l’eruzione del Vesuvio nel 79 d.C., during the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD. Book XI of nel documentato e appassionato libro XI della sua enci- Pliny’s erudite and enthusiastic “Naturalis Historia” conclopedica Naturalis Historia, in cui manifesta tutta la sua tains the author’s admiration for “these insects created ammirazione per questi insetti creati apposta per l’uo- especially for man” (“… apibus … praecipua admiramo (“…apibus… praecipua admiratio, solis… homi- tio, solis … hominum causa genitis”; “tam beneficum num causa genitis”; “tam beneficum animal” definisce animal”). As for their relationship with viticulture, he asl’ape). Quanto al rapporto con la viticoltura, egli associa sociates the abundant production of honey in the suml’abbondante produzione del mie- mer solstice with the flowering of le nel solstizio estivo al fiorire… dell’uva, e la raccolta di quello sel- L’impollinazione delle viti vines, and the collection of wild honey at the end of the harvest. vatico alla fine della vendemmia. dona al vino aromi di erbe, Paolo Fontana, the entomologist, Una visione ampia e documentata fiori e frutta circostanti expert beekeeper and president of sull’apicoltura dalle origini ai giorni nostri la offre Paolo Fontana, entoPollination of the vines the World Biodiversity Association, wrote a wide-ranging book about mologo, esperto apicoltore e presi- imparts the aromas beekeeping from its origins to the dente della World Biodiversity As- of surrounding flowers present day, called The Pleasure of sociation, con Il piacere delle api and vegetation to the wine Bees, in 2017. Fontana has also del 2017. written about the flourishing pre-

Frontespizio, con sintesi grafica dell’apicoltura antica, da P. Fontana, Il Piacere delle Api, WBA Project Ed., Verona, 2017 Frontispiece showing beekeeping in antique times by P. Fontana, The Pleasure of Bees, WBA Project Ed., Verona, 2017

Artemide Efesia Reitia, copia romana in alabastro e bronzo con restauri del ’900, Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli Artemis Ephesia Reitia, alabaster and bronze, Roman copy with 20th century restoration, National Archaeological Museum in Naples

De agricultura vulgare, xilografia da P. de’ Crescenzi, l. IX, Venezia, 1511 De agricultura vulgare, woodcut from P. de’ Crescenzi, l. IX, Venezia, 1511

Alla fiorente apicoltura preromana e romana Fontana ha dedicato anche altre recenti pubblicazioni tra cui Il Veneto, le api e l’apicoltura del 2019, ove è riportata l’immagine di una copia romana in alabastro e bronzo della dea Artemia Efesia, denominata, in area venetica, anche Reitia (dalla popolazione dei Reti del Noricum/ Austria, contemporanei ai Paleoveneti e poi ai Romani conquistatori): una conferma del commercio di miele dalla Pianura Padana ai paesi transalpini lungo la Val d’Adige, attestato dagli storiografi latini. Durante il MeRoman and Roman world of beekeeping in works including The Veneto, Bees and Beekeeping (2019), which includes an illustration of a Roman alabaster and bronze copy of a statue to the goddess Artemis Ephesia, called Artemis Reitia in the Venetian regions (after the Reti of Noricum/Austria) whose raiment shows clear evidence for the honey trade referenced by classical-age historians running from the Po Valley to the transalpine regions along the Val d’Adige. There is little about bees in the early Middle Ages, despite the fact that beekeeping

Pagina precedente. Frontespizio, incisione in rame da Grido della ragione, e dell’interesse per la salvezza delle api, Aquila, Grossiana, 1826 Preceding page. Frontispiece, copper engraving from A cry of reason and sense for the salvation of bees, Aquila, Grossiana, 1826

A lato. Antiporta, litografia da The Naturalist’s Library conducted by Sir William Jardine, Entomology, vol. VI; Bees, The natural history of bees, Edinburgh, Lizars, Edinburgh, 1840 Below. Page preceding frontispiece, engraving from The Naturalist’s Library conducted by Sir William Jardine, Entomology, Vol. VI; Bees, The Natural History of Bees, Lizars, Edinburgh, 1840

dioevo la produzione letteraria trascurò le api, anche se l’apicoltura e la produzione di miele e cera continuavano ad essere curate da vari ordini monastici. Rifiorì la letteratura apicola, prima in latino e poi nelle lingue volgari, alla fine del ’400. Pioniere anche sulla descrizione di tale attività agronomica fu il bolognese Pietro de’ Crescenzi con il suo trattato in latino Opus ruralium commodorum, oggetto, dopo la prima edizione del 1471, di numerose altre traduzioni volgari, arricchite da immagini. Nei secoli sucand the production of honey and wax continued in the hands of the various monastic orders. Literature about apiculture came to the fore again, first in Latin and then in the vernacular, at the end of the 1400s. It was Pietro de’ Crescenzi, from Bologna, who pioneered studies of beekeeping, as well as other agricultural activities, in his Latin-language treatise Opus ruralium commodorum, which was the inspiration for many other works that came out, also in translation, after its illustrated first edition in 1471. In the centuries

Litografia da A. Neighbour, The apiary, London, 1878 Engraving from A. Neighbour, The Apiary, London, 1878

Un uomo nero assalito da sciame d’api, xilografia da T.B. Miner, The american bee keeper’s manual, New York, Saxtoan, 1854 A black man attacked by swarms of bees, woodcut by T.B. Miner, The American Bee Keeper’s Manual, Saxton, New York, 1854

cessivi numerosissime pubblicazioni sull’apicoltura in varie lingue straniere si susseguirono quasi a gara, a confermarne l’importanza non solo culturale, ma anche commerciale. Da segnalare per il ’600 l’opera De animalibus insectis libri septem, Bononiae, 1602 di cui il primo è dedicato proprio alle api. Alla fine del Settecento la nuova sensibilità illuministica si preoccupò anche della salvaguardia delle api, spesso sacrificate per la raccolta del miele. Fra le varie proteste, particolarmente vibrata fu, già nel titolo, l’opera Grido della ragione… per la salvezza delle api del 1826. Qualche anno dopo trionfava, anche per lo splendido apparato grafico a colori, un ricco trattato sulle api, sesto volume di una corposa Naturalist’s Library, pubblicata a Edinburgh nel 1840 nel cui testo, dopo la litografia dell’antiporta, sono incastonate altre affascinanti immagini di api. Nel 1854, a questa gara editoriale sulle api, parteciparono anche gli Stati Uniti d’America con l’opera The american beekeeper’s manual del 1854. Nel 1878 chiuse l’attività editoriale di libri antichi sulle api un’altra interessante pubblicazione inglese, The apiary.

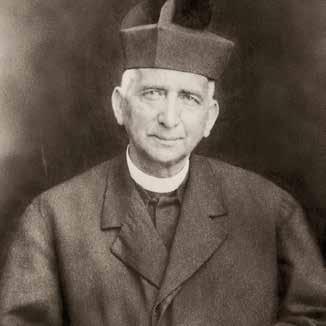

Mario Bagnara, consulente culturale della Biblioteca Internaz. ‘La Vigna’, Vicenza (già presidente 2006-18). Pubblicista e saggista, è stato docente universitario, preside, assessore alla cultura. È Accademico olimpico e socio dell’Accademia Italiana della Vite e del Vino, e presidente onorario dell’Associazione Beni Italiani Patrimonio Mondiale UNESCO. that followed, numerous publications on beekeeping in various foreign languages competed for attention, thus confirming the importance of apiculture not only culturally, but also commercially. Notable in the early seventeenth century is De animalibus insectis libri septem, (Bologna 1602), the first of which is dedicated to bees. And at the end of the eighteenth century, the new enlightenment sensitivity turned to the safeguarding of bees, which often met their end as their honey was collected. The title of the book A cry of reason and sense for the salvation of bees, published in 1826, says it all. A few years later, vol. VI of the substantial Naturalist’s Library, published in Edinburgh in 1840 as a comprehensive treatise on bees, stands out for its splendid colour illustrations, starting with the pre-frontispiece and including many other fascinating images of bees. In 1854, the United States of America entered the publishing fray with The American Beekeeper’s Manual of 1854. Finally, in 1878, the fascinating English publication, The Apiary, was the last book to be published on bees that can be considered to be ‘ancient and historic’.

Mario Bagnara, cultural consultant for ‘La Vigna’ International Library of Vicenza (former President 2006-18). Publicist and essayist, former university lecturer, head teacher and cultural commissioner. An Olympian Academician and member of the Italian Academy of the Vine and Wine; Honorary President of the Italian Association for UNESCO World Heritage Sites.