Horacio Rodríguez Larreta Jefe de Gobierno de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires

Felipe Miguel Jefe de Gabinete de Ministros

Enrique Avogadro Ministro de Cultura

Victoria Noorthoorn Directora del Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Falco, Federico

Adentro no hay más que una morada / Federico Falco ; Alejandra Aguado ; dirigido por Victoria Noorthoorn ; editado por Martín Lojo ; Alejandro Palermo.1a edición bilingüe - Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires : Gobierno de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, 2022.

300 p. ; 23 x 16 cm.

Edición bilingüe : Español ; Inglés. Traducción de: Ian Barnett ; Kit Alexander Maude.

ISBN 978-987-673-615-2

1. Arte. 2. Arte Argentino. 3. Arte Contemporáneo. I. Aguado, Alejandra. II. Noorthoorn, Victoria, dir. IV. Lojo, Martín, ed. V. Palermo, Alejandro, ed. VI. Barnett, Ian, trad. VII. Maude, Kit Alexander, trad. VIII. Título.

CDD 700.982

Este libro fue publicado en ocasión de la exposición Adentro no hay más que una morada, que tuvo lugar en el Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires entre el 18 de septiembre de 2021 y el 16 de mayo de 2022.

Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires Av. San Juan 350 (1147) Buenos Aires, Argentina

Impreso en Argentina Printed in Argentina

Diseño: Pablo Alarcón Alberto Scotti Para estudio Cerúleo

Créditos fotográficos

Cortesía Erik Arazi pp. 94-95

Fabián Cañás p. 91

Cortesía Dana Ferrari p. 60

Cortesía Carolina Fusilier pp. 114-117

Viviana Gil pp. 42-49, 54-57, 61, 68-71, 81, 86-90, 98-101, 108-111, 118-119, 130-135, 146-149

Carolina Grillo pp. 140-141

Nina Kovensky pp. 52-53

Guido Limardo pp. 78-79, 92-93, 129, 142-143

Florencia Lista pp. 124-127

Gonzalo Maggi pp. 96-97, 150-153 Jorge Miño pp. 198-211

Santiago Orti pp. 58-59, 60 (árbol), 137

Florencia Palacios pp. 76-77

Federico Roldán Vukonich pp. 120-121

Catalina Romero pp. 64-67, 72-75 Florencia Sadir pp. 144-145

Por Victoria Noorthoorn —p. 9

Por Federico Falco —p. 15

Ser y habitar Por Alejandra Aguado —p. 25

Lucrecia Lionti —p. 42

Nina Kovensky —p. 46

Florencia Vallejos —p. 50

Lucía Reissig y Bernardo Zabalaga —p. 52

Blas Aparecido —p. 54

Dana Ferrari —p. 58

Santiago Villanueva —p. 64

Carlos Aguirre —p. 68

Gala Berger —p. 72

Florencia Palacios —p. 76 Nacha Canvas —p. 78

Juan Gugger —p. 84

Florencia Caiazza —p. 86

María Guerrieri —p. 90

Erik Arazi —p. 92

Francisco Vázquez Murillo —p. 96

Benjamín Felice —p. 98

Agustina Wetzel —p. 102

Daniela Rodi —p. 108

Eugenia Calvo —p. 110

Carolina Fusilier —p. 114

Gonzalo Beccar Varela —p. 118

Federico Roldán Vukonich —p. 120

Ana Won —p. 124

Matías Tomás —p. 128

Antonio Villa —p. 132

Jimena Croceri —p. 134

Denise Groesman —p. 136

Soledad Dahbar —p. 140

Florencia Sadir —p. 142

La Chola Poblete —p. 146

Alejandra Mizrahi —p. 150

Agustina Triquell —p. 156

Reseñas de trabajos y biografías de los artistas

Por Alejandra Aguado y Clarisa Appendino —p. 161

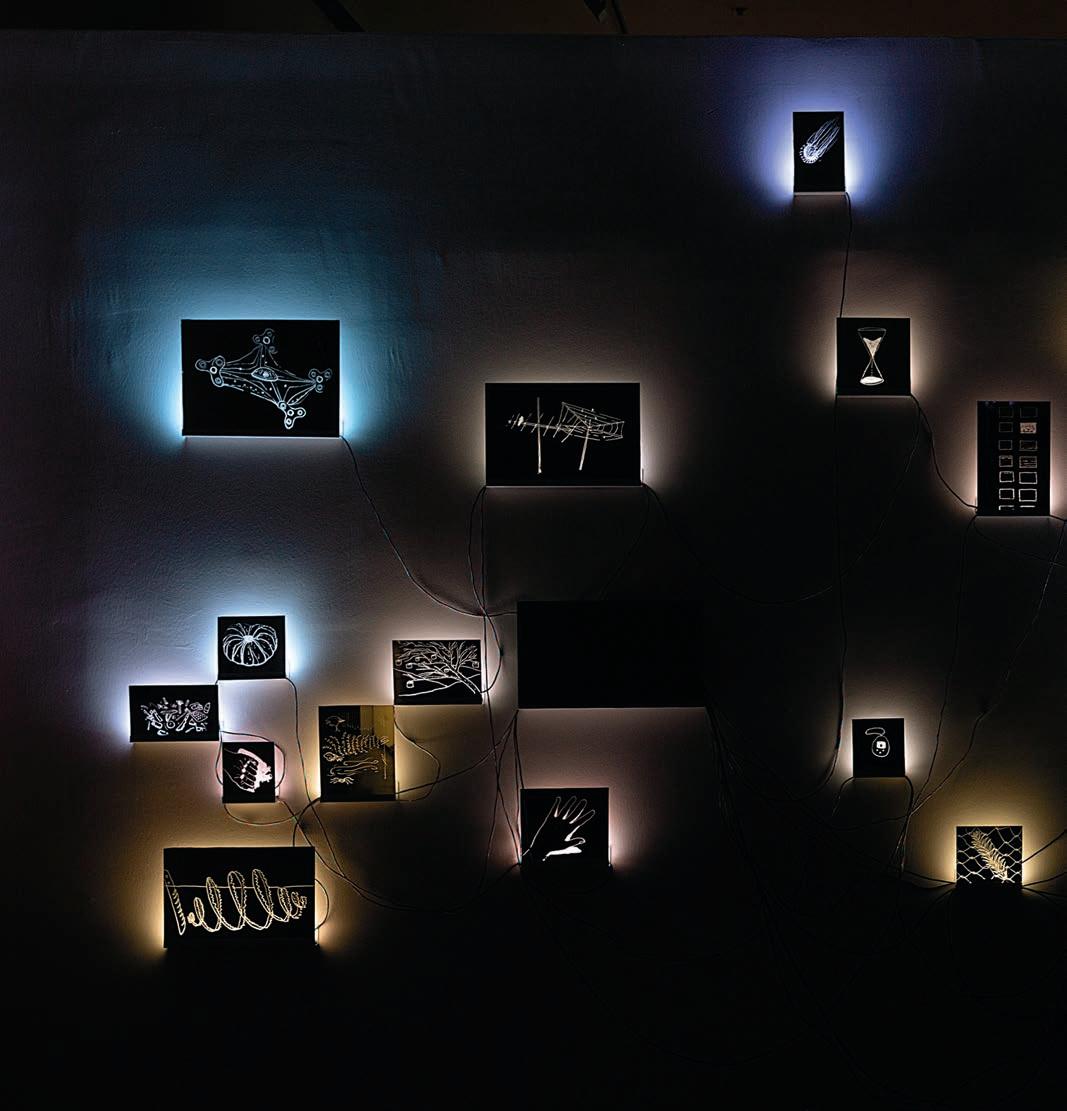

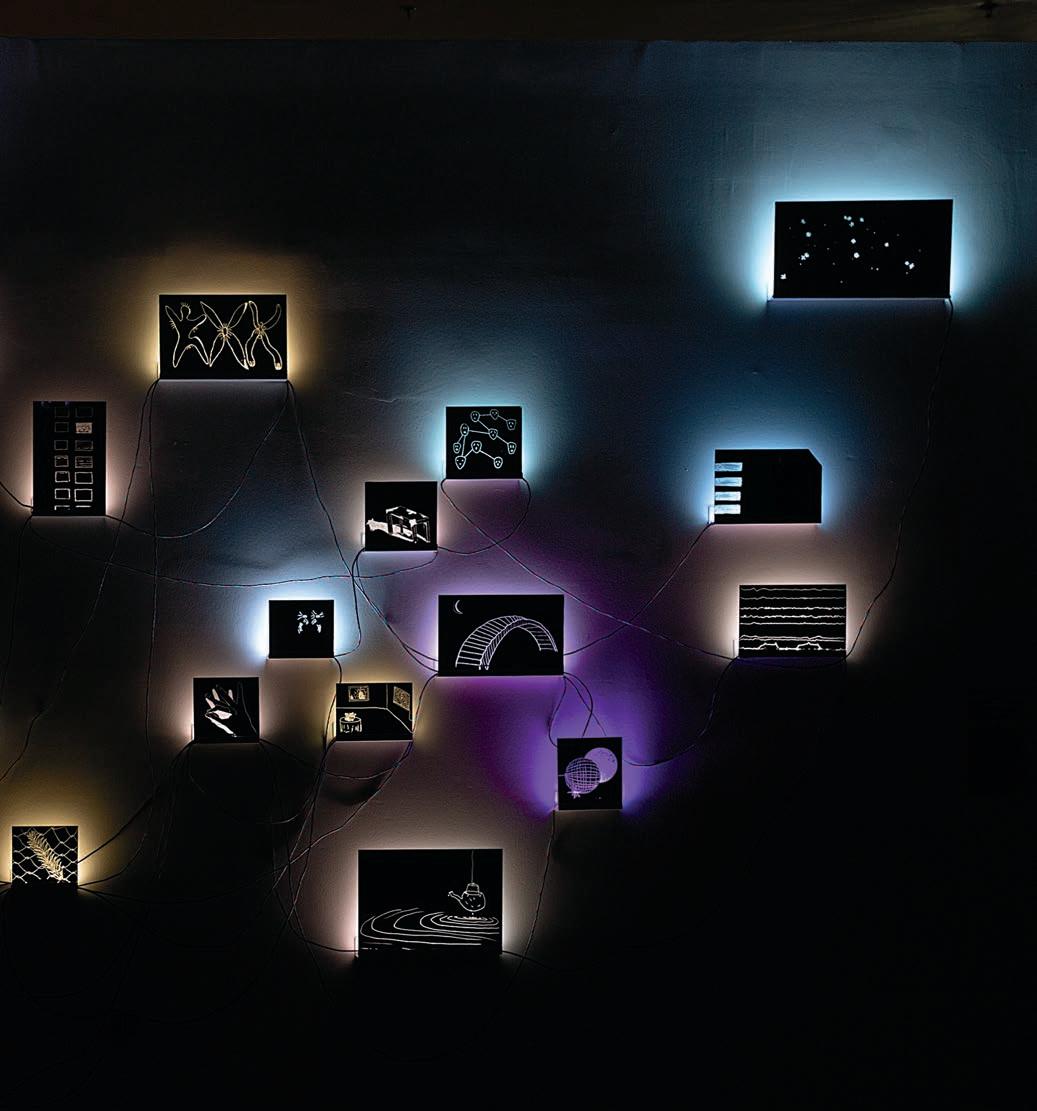

Vistas de sala [Gallery views]—p. 197

Lista de obras de la exposición [Exhibition checklist] —p. 213

English texts —p. 229

El repentino cierre de puertas del Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires el 19 de marzo del 2020, a causa de la pandemia de COVID-19, marcó el advenimiento de una nueva etapa en su historia, que se inició a partir de un veloz diagnóstico: era necesario comunicar a la sociedad que, en los últimos siete años, esta institución se había transformado en mucho más que una casa-vidriera de exposiciones. En marzo de 2020, ya era un espacio de investigación permanente, creador de contenidos de excelencia en los ámbitos de la historia del arte, la conservación, la curaduría, la producción y reconstrucción de obras de arte, la edición de libros. Era también un museo activo en la sociedad, que desplegaba una amplia red de vínculos con instituciones educativas, instituciones de salud, fundaciones y ONGs dedicadas a personas con discapacidad y a personas en el espectro autista, y con las más diversas organizaciones sociales, tanto públicas como privadas. Esta usina de investigación y creación ya estaba preparada para apoyar a las comunidades artísticas y educativas con las cuales interactúa cotidianamente con el objetivo de dar respuestas concretas desde el arte al público general y ofrecer refugio espiritual y simbólico a una sociedad en crisis. El trabajo fundacional estaba hecho, los profesionales estaban preparados y solo teníamos que articular con contundencia un abanico de ofertas concretas y accesibles. De cara al desafío, reconocimos rápidamente nuestras falencias: la institución no reflejaba toda su dimensión en sus plataformas digitales. Además, había que coordinar, motivar y proteger a un equipo de 130 profesionales sensibilizados por el aislamiento, que

trabajaban en modo remoto. También recordamos nuestras convicciones: el arte es una herramienta para sensibilizar al ser humano y transformar el mundo, y el artista es un poderoso agente de cambio capaz de concebir las transformaciones necesarias para procurar una vida económica y social mejor.

Decidimos generar una reflexión sensible en medio de la crisis y la incertidumbre, para lo cual convocamos a artistas de las más diversas disciplinas a elaborar respuestas desde el arte sobre aquello que estábamos viviendo en aquel presente inimaginable. Asimismo, buscamos activar estrategias de apoyo económico concreto para las comunidades artísticas, intelectuales y educativas a las que la crisis afectaba profundamente. El programa que lanzamos el 6 de abril de 2020, #MuseoModernoEnCasa, fue pensado como un archivo del presente, con la misión de comunicar y difundir en tiempo real contenidos, ideas y obras que las comunidades artísticas y educativas creaban respondiendo a nuestra invitación de reflexionar sobre tópicos, ideas y situaciones que pudimos identificar como urgentes. A través de este programa convocamos —y pagamos los encargos con fondos que recaudamos especialmente a tal efecto— a más de 400 artistas, escritores, actores, músicos e intelectuales, no solo para compartir sus reflexiones y concebir talleres, cursos, acciones y debates, sino también para desarrollar contenidos artísticos y crear lo que podríamos conceptualizar como un nuevo género de contenidos nativos, generadores de una comunicación más directa y una mayor participación e interacción con los diversos públicos. Buscamos responder a las vivencias y experiencias de la nueva coyuntura: el encierro, las pantallas, la alteración del tiempo, la crisis ambiental, la exacerbación de los racismos y la discriminación, la necesidad de silencio, los vínculos entre arte y salud, y entre arte y comunidad fueron algunos de los más de 25 programas de contenidos digitales que desarrollamos desde entonces.

El 2020 fue, entonces, un año signado por la confianza: confianza del Museo Moderno en los artistas argentinos y en la importancia de comunicar las ideas y propuestas de la comunidad artística ante una vivencia de crisis, y confianza de cada uno de los 400 artistas en nuestra institución, cuyos profesionales se dedicaron a sostener, producir, financiar y difundir cada idea y cada proyecto. La tarea fue titánica, el resultado inimaginable, con más de ocho millones de personas activamente involucradas en los contenidos del Museo Moderno. Fue una gran alegría notar que, gracias al universo digital, las paredes físicas de nuestro museo se volvían porosas, permeables, y que nos expandíamos cada vez más por todo el país.

Fue en este contexto de hazañas, de confianza y de agradecimiento que se gestó, entre agosto y septiembre del 2020, el germen de la exposición Adentro no hay más que una morada, que este libro retrata. Desde los equipos de Dirección y Curaduría, pensamos en una exposición que pudiese dar visibilidad a la enorme producción que sucedía puertas adentro de los talleres a lo largo y a lo ancho de nuestro país. Nos dedicamos a pensar una exposición imaginaria que pudiese decir “¡Gracias!” y otorgar a los artistas que nos habían apoyado ante el cierre del museo el espacio para poder compartir sus obras con el público en nuestras salas del barrio de San Telmo.

Con una generosidad y coraje inigualables, la curadora Alejandra Aguado tomó las riendas del proyecto y se lanzó a una investigación exhaustiva vía Zoom con cientos de artistas de todo el país. Finalmente, eligió a treinta y cuatro artistas argentinos, con quienes realizó un seguimiento de los procesos creativos y constructivos de las obras, y, más adelante, trabajó junto al equipo de Producción del museo en su producción y montaje. Adentro no hay más que una morada es una exhibición colectiva que reúne el trabajo reciente de artistas que provienen de distintas regiones de la Argentina, en cuyas obras se manifiesta la voluntad de canalizar y potenciar el vínculo personal con el entorno —sea este material, intangible o incluso espiritual. En todos los casos, se trata de artistas jóvenes y de obras mayormente producidas durante los últimos años, es decir, atravesadas por la experiencia de la pandemia y el aislamiento. Es un conjunto variado y enriquecedor que nos abre las puertas al mundo propio de cada artista, pero también nos deja entrever el contexto del que provienen, cómo ellos afectan ese entorno y cómo se dejan afectar por él. Los saberes heredados, aprendidos o intuidos y el manejo de la tecnología se entrecruzan en nuevos y personalísimos mundos plásticos; los rasgos particulares de este momento histórico dejan expuesto lo más simple y cotidiano, y el trabajo desarrollado en soledad demuestra ser parte de un enorme tejido comunitario que nos afecta a todos.

Es por esto que quiero brindar mi más especial agradecimiento, en primer lugar, a los treinta y cuatro artistas involucrados en esta exhibición. Es el deseo del Museo Moderno constituirse en una institución referente del arte argentino moderno y contemporáneo, pero sobre todo es su anhelo ser la casa de los artistas argentinos. Por eso les decimos muchísimas gracias por habitar con sus obras nuestras salas y por compartir sus miradas y sus mundos con inmensa generosidad.

Lograr llevar adelante un proyecto participativo y colectivo con artistas de tantas provincias de nuestro país siempre es una tarea difícil. Más desafiante aún fue hacerlo en el contexto de la pandemia, que durante largo tiempo impidió el traslado físico, el contacto personal y, en muchos casos, incluso el encuentro con la materialidad de las obras. Por lograr esta hazaña y liderarla con gran entusiasmo y alegría quiero agradecer especialmente a Alejandra Aguado, curadora de la exhibición. Su cálida y cuidadosa mirada sobre cada obra y su paciencia al llevar adelante innumerables visitas y conversaciones virtuales hicieron posible que el encuentro de todas estas sensibilidades formara un conjunto tan variado como coherente. También agradezco a Clarisa Appendino, asistente curatorial de la exhibición, sin cuya ayuda hubiera sido imposible reunir este inmenso caudal de obras e información, y sostener tan cuidadosa interlocución con los artistas. Mi agradecimiento especial, asimismo, al equipo de Exposiciones Temporarias del museo, que tomó a su cargo la coordinación general de esta exposición desde los más diversos puntos del país: gracias Micaela Bendersky, Paula Pellejero y Giuliana Migale Rocco.

Asimismo, dentro del equipo del museo, agradezco a Iván Rösler, Almendra Vilela, Agustina Vizcarra, Gonzalo Silva, Rocío Englender y Manuel Maquirriain, por su enorme dedicación para lograr un diseño de montaje perfecto para el conjunto y para cada obra seleccionada, y a Leo Ocello por coordinar el montaje junto a su equipo: Fernando Súcari, Germán Sandoval y Andrés Martínez. También a Guillermo Carrasco, Soledad Manrique, Claudio Bajerski y Jorge López del equipo de técnica. Sin el trabajo incansable de cada uno de ellos para superar los múltiples desafíos impuestos por la pandemia, hubiera sido imposible materializar y llevar a buen puerto esta exhibición.

Nos parece fundamental poner a disposición del público este libro en el que hemos querido no solo documentar las obras que formaron parte de la exhibición, sino también dialogar con ellas a través de un texto literario. Agradezco enormemente, en este sentido, la poética prosa de Federico Falco, que se suma a estas páginas. También a todo el equipo editorial del Museo Moderno por el comprometido trabajo para que esta publicación encuentre su forma y vea la luz. Su trabajo sensible y atento fue también fundamental en el desarrollo de la exposición al permitirnos encontrar, como en cada ocasión, las palabras justas para comunicarla a nuestro público.

Esta y todas las exposiciones que el museo presenta al público no serían posibles sin el apoyo del Gobierno de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires.

Agradecemos profundamente a Horacio Rodríguez Larreta, Jefe de Gobierno, y a Enrique Avogadro, Ministro de Cultura, por su apoyo incondicional en una etapa tan compleja y crítica como lo fue la que debimos atravesar durante los últimos dos años. Mi sincero agradecimiento, sobre todo por sostener al gran equipo de profesionales del museo, asegurando los puestos de trabajo y honrando de esta manera el saber y la experiencia de una institución que ha logrado posicionarse en un nivel de excelencia tanto a nivel nacional como internacional.

Agradezco al gran equipo del Museo Moderno por su fundamental entrega, su infinito compromiso por la excelencia y su sorprendente generosidad, todas características que nos permiten construir, juntos y todos los días, una gran institución cultural a partir de valores y a través de acciones que contribuyen a afirmar la relevancia del museo como un agente fundamental de la comunidad, capaz de impartir salud y bienestar, y de señalar a través del arte posibles caminos para una mejor vida en sociedad.

Asimismo, extiendo las gracias a nuestra Asociación Amigos y a su Comisión Directiva, que se comprometen con los proyectos que proponemos todos los días para hacer del Moderno una institución inclusiva, federal y accesible, y por sostener su compromiso y entusiasmo durante tiempos más que desafiantes.

Deseo expresar nuestro profundo reconocimiento al Banco Supervielle, al Estudio Azcuy y a la Fundación Medifé, nuestros aliados estratégicos, que colaboran generosa e incansablemente con nuestra gestión. También agradezco el apoyo de la Fundación Banco Ciudad y del Grupo Teka, y de nuestros colaboradores estratégicos, Flow, Plavicon y Fundación Andreani.

Para este proyecto contamos también con la importante colaboración de las galerías Constitución, El Gran Vidrio, Nora Fisch, Fuga, Intemperie, Isla Flotante, Moria, Piedras, Selvanegra y Alberto Sendrós, que, en su calidad de representantes de varios de los artistas, han facilitado un sinnúmero de gestiones e información, y de una gran cantidad de coleccionistas privados; a todos ellos, muchísimas gracias.

Finalmente, agradezco muy especialmente al público que se acerca al museo de distintas maneras y desde distintos lugares, ya que son el motor de nuestra tarea diaria. Los invito a recorrer estas páginas y nuestras salas a través de todas sus plataformas. Es nuestro deseo que los proyectos del Museo Moderno lleguen a cada uno de ustedes, que se involucren con ellos y los adopten como propios.

Traslasierra: la pared de sierras como murallón y como protección y como cárcel, la gente que viene a quedarla, todos dejamos atrás algo, todos huimos de algo, todos buscamos algo, los atardeceres naranjas y la sutil diferencia con los atardeceres dorados, tener que ver ciento cincuenta y tres atardeceres para poder describir un atardecer paso a paso, la diferencia entre lo que pueden ver los que viven una vida nómade y lo que pueden ver los que viven siempre, toda la vida, en el mismo lugar, el mismo pueblo, en la misma casa. La diferencia entre una visión más general y amplia y una visión muy específica y particularizada.

Apropiarse de cada lugar al que se llega, desembalar, acomodar la ropa en los estantes, juntar algunas flores y ponerlas en un vaso, hacer de cuenta que todo tiene historia y ya ha sido usado antes. Armar una casa. Cuando vivía en Brasil, cuando vivía en Tailandia, nunca sabía dónde iba a dormir al día siguiente, a la siguiente semana, yo vivía en la playa, me cuenta una mujer alta, de sonrisa suave, que apenas está empezando a envejecer. Dice: me alcanzaba solo con un par de trapos por acá, otros trapos por allá, unas velas, poner musiquita y ya hacía mío cualquier espacio. Ahora vive en las afueras del pueblo, un largo camino de piedra, no demasiado bien mantenido, lleva a su casa. Es una casa de adobe, que mira al norte, y adentro es amplia y muy despejada, pocos muebles, unos almohadones para sentarse en el piso, una estufa rocket: durante un buen rato trata de explicarme cómo funciona y cuáles son sus ventajas pero aunque el tema me interesa, enseguida me

pierdo, me distraigo. Miro las paredes. La casa me recuerda a unas fotos que alguna vez vi de la casa de Georgia O’Keefe en el desierto de Nuevo México, palos secos y retorcidos, quietos bajo el sol y el viento que los han ido lentamente decolorando hasta llenarlos de largas grietas y ponerlos blancos, como si los hubiera llevado y traído la marea durante años y años y los hubiera decolorado el agua del mar salada. La mujer sigue hablando. Combustión eficiente, ahorro de leña, retención del calor. Sobre una de las paredes de adobe colorado de la casa hay un gran dibujo de líneas blancas. Son líneas que forman como una red desplegada, una trama. Ahora la mujer dice que ella está muy bien sola, que no volvería a estar en pareja, que ni siquiera puede pensarlo, que a ella le gusta así, le gusta vivir sola en su casa, que para qué, otro hombre en su vida, todo eso ya quedó atrás, no hace falta. Junto al zócalo, debajo de la red pintada, hay una botella de plástico cortada al medio con un pincel y llena de pintura blanca. Cuando se da cuenta de que no la escucho, la mujer se acerca a la pared y me explica: la casa tuvo un problema, se cuarteó el revoque, no estaba del todo bien hecha la mezcla de arcilla, baba de tuna y mierda de caballo, a veces pasa. Por eso en las largas noches de invierno, ella se entretiene dibujando líneas sobre la pared agrietada, para disimular las rajaduras. En algunas zonas, la pintura sigue las grietas, arma una trama cubriendo el craquelado; en otras, son solo puro trazo que imita las tensiones del adobe al quebrarse.

Lo más terrible del invierno en las sierras es llegar una noche tarde a casa y darte cuenta de que ya no quedan fósforos en la caja y que te olvidaste el encendedor en algún lado y que hay leña fina, papeles, leña gruesa, querosene, cartones, ramitas y paja para encender un fuego en la salamandra pero nada con qué empezarlo.

Una vez conocí a un chico que se separó y vivió casi cuatro años sin casa: llevó todas sus cosas a lo de sus padres, durmió un tiempo en lo de un amigo, después en lo de otro amigo, como era actor algunos días en que los ensayos terminaban tarde podía dormir en la sala de teatro, viajó, durmió en hostels, en casas de fin de semana, en invierno se quedó en vacías casas de verano y en verano se quedó en departamentos para regar plantas y darles de comer a gatos que nunca se acordaba bien cómo se llamaban. Le dije que yo no hubiera podido sostener esa vida ni siquiera un par de semanas: a mí me lleva tres o cuatro días instalarme, necesito cierta rutina, las primeras noches duermo mal, estoy alerta, necesito despertar varias mañanas en la misma habitación, frente a la misma ventana, para recién entonces empezar a sentir que esa casa se volvió refugio, lugar seguro, resguardo. ¿Cómo hacías

para no volverte loco, yendo así de un lado a otro, así tanto tiempo, así cuatro años?, le pregunté. El chico se encogió de hombros, dijo que era piscis con ascendente en piscis y luna en acuario, que se había ido dando. Cuando me preguntó de qué signo era yo tuve que responderle que del ascendente no me acordaba, pero que era virgo con luna en capri y él dijo claro vos nunca podrías hacerlo, tenés demasiada tierra en tu carta.

Durante un tiempo tuve una vida más o menos nómade, hogares provisorios, por seis meses, por un año, escritorios inventados con una puerta de placard y dos caballetes de Easy, como no había cajones tenía que guardar las medias en una caja de zapatos, lavar los platos en la bacha del baño, aprender a tener roommates, aprender que los miércoles sí o sí te toca limpiar: una semana los espacios comunes, una semana la cocina, una semana el baño, saber que nunca hay que vaciar de sobras ajenas la heladera, que de la alacena se pueden tomar fideos y arroz prestado, pero hay que avisar o devolverlo, código de honor, nunca robarlo. Cada cierto tiempo cambiaba de departamento, de país, de ciudad. Todo era “por un tiempo”, por un par de meses, por un par de años. No tenía sentido acumular nada. La vida era portátil. La vida se redujo a lo más simple e indispensable. Después conocí a alguien y juntos armamos una casa, después nos separamos, después ya no supe qué quería para mí, o dónde, o cómo pero igual no importó porque siempre hay que vivir en algún lado.

Cuando llegué al valle, empecé a fantasear con quedarme. Acá todos venimos escapando de algo, me dijo una chica una tarde, a los poquitos días de haber llegado. Para eso es que cruzamos las montañas, por eso es que estamos del otro lado. Las montañas son un muro que divide, que separa, amanecer todos los días con ese paredón de piedra, ahí, cayendo en picada, da una sensación de amparo. Después le dio una seca al porro, lo pasó de manos. Hasta que te das cuenta de que acá está lleno de huidos, y que los huidos no somos la gente más fácil del mundo para relacionarse, dijo la chica. Porque de protección a encierro, respecto al mismo muro, hay solo un ligero cambio de mirada.

Dejate llevar, me dijo un hombre que vive acá hace muchos años. Dejate llevar y fijate qué te pasa. Cada uno es cada uno y a las decisiones sos vos el que las tiene que ir tomando. Dejate llevar y prestá atención a cómo te actúa en el cuerpo el valle, cómo te asienta el aire, cómo se te acomoda la respiración, el resuello, el tranco. Y no trates de imponer nada. Permití que sea el valle el que haga. Es como tratar de frenar el agua, mejor que entre y se lleve lo que se tenga que llevar y que lo que tenga que traer lo traiga. Es al

vicio intentar frenar el agua, implica mucha fuerza, mucha energía y es batalla perdida de antemano.

Me sorprendió la comparación acuática, justo acá, donde todo es tan árido, donde los cursos de agua son apenas arroyitos que ni siquiera califican de ríos y que se pasan secos más de medio año.

¡Ah!, suspiró una chica después de bailar un buen rato sola, girando bajo el sol, entre los arbolitos raleados del monte en invierno. Estábamos en un festejo de cumpleaños, un sábado seco, frío y de perfecto cielo celeste, soleado. Apenas más allá, sobre un aguayo tirado en el pasto, había budín y galletas y una torta crudivegana. ¡Ah!, suspiró la chica y se sentó a mi lado, cerró los ojos y sonrió casi con nostalgia. Qué lindo el momento en que estás, qué lindo estar recién llegado. ¡Nada mejor que una buena cura geográfica!, dijo. ¿Vos sabías que all forms of landscape are autobiographical? No, no sabía.

La chica sonrió: es una frase de un poeta, me explicó. Ahora no me acuerdo cómo se llama.

Alquilo una cabañita mínima, pequeña pero cómoda, rodeada de monte, con una gran vista abierta hacia el valle y las montañas cuidándome las espaldas y en las noches de invierno, después de que el sol cae sobre el valle, empiezo a fantasear con el deseo de una casa para siempre, para ir y venir, para viajar, para pasar tiempo en otros lugares, otras ciudades, pero una casa mía, un lugar donde tener mis cosas, un lugar adonde volver y donde asentarse. Se lo cuento a Ana, que vive sola monte arriba, en una casa pequeña, con un gran algarrobo al frente, una higuera y dos manzanos de manzanitas pequeñas, carasucias, de una variedad antigua, adaptada al valle. Es normal, me dice Ana, a determinada edad querer tener un lugar propio donde armar, querer tener una casa. Y entonces en el quiosco me compro un cuaderno escolar en blanco y en la primera hoja escribo, centrado y con letras bien grandes: el cuaderno de la casa. Después, frente a los renglones perfectamente alineados de la hoja, cierro los ojos y repaso una por una todas las casas donde alguna vez viví, donde dormí una noche, donde pasé vacaciones, donde me instalé un par de semanas. De cada casa anoto las cosas que más me gustaron y con esos retazos armo un Frankenstein imaginario de la que quisiera que fuera mi casa. Una cocina a leña en el extremo de la mesada, para en invierno hacer guisos y sopas y taparla con un hule floreado en verano; un baño de azulejos blancos, de los comunes, quince por quince, con la junta tomada con pastina negra, como en el baño de la casa de mis abuelos en el campo; una despensa sin absolutamente ninguna ventana, con muchos estantes y oscuridad y

frescura para guardar frascos de dulces y conservas, y para colgar del techo una ristra de ajo y apilar en el suelo, contra la pared, una cosecha entera de zapallos; cemento alisado en la cocina, tablones de pinos para el dormitorio; una salamandra en el centro del living; un sillón muy cómodo para leer junto al fuego; cocina comedor y living integrado, un solo dormitorio aparte; una casa pequeña para calefaccionar bien en invierno; vidrios dobles, orientación norte, buena exposición solar, aberturas de cierre hermético, nada de chifletes, preferible pasar calor en verano que frío en invierno; una galería ancha y la distancia exacta entre columnas para colgar una hamaca paraguaya, muchos placares donde guardar un montón de cosas y olvidarse para siempre dónde estaban; una biblioteca de piso a techo y con estantes de exactamente 17 centímetros de profundidad porque casi no existen libros con tapas de más de 17 centímetros de ancho, y no quiero que sobre espacio adelante: basta de apoyar adornitos sobre los estantes, basta de alebrijes mexicanos, basta de caracoles traídos de ninguna playa, basta de lobos marinos traslúcidos recuerdo de Mar del Plata y condenados para siempre a predecir si viene lluvia tiñéndose de rosado, de violeta si va a estar inestable, de azul si toca día de sol radiante, basta de fotos apoyadas sobre el lomo de los libros, ni tarjetas, ni postales enviadas desde otro país: ya hace años, ya hace siglos que nadie manda postales. Ahora solo quiero libros, uno junto a otro, de piso a techo; y otra biblioteca, bajita y más profunda, para los libros de arte, o los de formato apaisado, o para todos aquellos cuyas tapas midan más de 17 centímetros de ancho.

De cada casa a la que entro, de cada casa a la que me invitan, de cada casa frente a la que paso, estudio la orientación con sumo cuidado. Las generales de la ley dicen que la casa tiene que estar orientada al norte para que sea fresca en verano y que en invierno sea cálida. Que lo ideal es que la cocina mire al este, para que la ilumine el primer sol de la mañana y a la hora del desayuno relumbre sobre las hornallas y en el contraluz deje ver el vapor que escapa de las tazas. Que es mejor que árboles de sombra protejan el lado oeste de los grandes soles del verano y que esos árboles sean de hoja caduca así en invierno se puede aprovechar sin problemas todo el calor de la tarde. Que el flanco sur no recibe nunca luz directa, que esas son las paredes que se enmohecen y que es el lado que más golpean los vientos helados, así que al sur mejor ubicar pocas aberturas y todos aquellos ambientes que no necesariamente tienen que estar calefaccionados: el lavadero, la despensa, el baño.

Y sin embargo, todo es al revés en la casa de Oscar. La casa de Oscar mira al este, al norte está el baño y no tiene ninguna ventana. La pared que

da al oeste tiene una ventanita mínima, apenas para asegurar la circulación. La única ventana más grande está mirando el sur. Si la diseñaste vos, si la construiste vos con tus propias manos, Oscar, ¿por qué tomaste estas decisiones tan particulares? Porque no me gusta el verano, porque hay demasiada luz, porque hace mucho calor acá en verano. A Oscar no le gusta tener toda esa luminosidad y ese sol adentro y armó su casa mirando el este: una casa al este siempre es más fresca y tiene menos luz.

A mí me gusta estar afuera, me gusta estar en el monte, para ver el sol, salgo afuera, dice Oscar, pero cuando estoy adentro necesito que la casa me calme, que me traiga hacia mí, me contenga. Por eso hice las ventanas chiquitas. Me gusta la casa a oscuras, medio en penumbras. Es ahí donde puedo encontrarme, dice Oscar y yo en mi cuaderno anoto: una casa que me calme, una casa donde pueda encontrarme.

Una casa cómoda y sombreada para recibir amigos que vengan el fin de semana y duerman en un montón de colchones tirados en el piso, en cualquier lado. Una casa sombreada en verano para pasar adentro las horas de la siesta y salir afuera a ver la puesta de sol, al final de la tarde. Reposeras y hamacas y mucho lugar donde echarse. Vajilla linda y toda diferente y toda un poco cachada. Que no haya ningún problema si un vaso se cae, ningún problema si se rompe un plato. Muchos floreros de muchas formas y tamaños: grandes, chiquitos, medianos, de vidrio transparente, de vidrio coloreado, de opalina, de cerámica, de gres, de porcelana, de bronce, de lata, de chapa, de plástico. Mucho lugar para guardarlos. Un río o un arroyo cerca. Limoneros y manzanos. Una planta de durazno, dos de ciruelas, tres higueras, cuatro nogales. Mandarinos y naranjos. Un jardín con crisantemos en otoño y dalias en verano. Un membrillero japonés que en julio florezca a rama desnuda y llene el jardín de rosado. Lirios, salvias guaraníticas, amistad, greggii y leucantas. Un par de coronas de novia, muchos rosales.

Amanece lloviznando, dejo el cuaderno a un costado, le agrego leña a la salamandra, pongo las noticias en la radio, lavo los platos, tiendo la cama, ordeno un poco las cosas sobre la mesada. Afuera por momentos se nubla por completo, cielo plomizo, de a ratos las nubes cubren la cabaña y estoy entre nubes y no se ve nada más allá de la cerca de palos, incluso puedo ver las nubes, retazos de nubes, coletazos vaporosos pasar por el patio, después vuelve a abrirse, vuelve a aparecer el valle abajo. Una gran mancha de sol, lejos en el valle, donde el sol logra colarse entre las nubes y está despejado.

En Sobre cosas que me han pasado, del chileno Marcelo Matthey Correa, hay una cita que me gusta mucho, aparentemente tomada de un libro de Pío Baroja. “¿Ves por la mañana, cuando la luz comienza a alumbrar, en lo alto del monte, una casa chiquita, con la fachada blanca, en medio de cuatro robles, con un perro blanco en la puerta y una fuentecilla al lado? Allí vivo yo en paz”. Mi ejemplar me lo regaló Diego Zúñiga una vez que estuve en Chile y supongo que Diego lo debe haber comprado en una librería de usados, porque el libro no tiene ningún rasguño, pero esa frase —la única en sus 138 páginas— vino subrayada con un lápiz grueso y apenas tembloroso y con una estrellita dibujada al lado. Evidentemente, con ese lector desconocido compartimos el deseo de tener el mismo perro, descansar bajo la sombra de los mismos árboles, mirar desde arriba el mismo valle, vivir los dos en la misma casa. Podríamos ser roommates, si no fuéramos los dos tan complicados para convivir, tan llenos de mañas.

Ruth es muy joven, se construyó su casa antes de cumplir treinta años. La casa de Ruth es pequeña, con cimientos de piedra, paredes de adobe, piso de tablones de pino y un techo de madera que es como un bote boca abajo. Los ladrillos de adobe son muy antiguos, eran de una tapera a la que los yuyos y las enredaderas estaban demoliendo en cámara lenta, brote a brote, primavera tras primavera, año tras año. Ruth se los compró al dueño del terreno por poquísima plata y se pasó una semana entera desmontando ladrillos con cariño y con cuidado y eligiendo y separando todos los que no estaban partidos y podían servir para su nueva casa. Después contrató un camión y una tarde fueron a cargarlos.

Al principio, me dice Ruth, esta casa eran solo cuatro estacas clavadas en la tierra. Cuatro estacas unidas con hilo que delimitaban un perímetro y yo iba de un lado para otro pensando: acá va la puerta, acá va una ventana, acá va a estar la cama, por acá se entra al baño y caminaba entre esos piolines y ensayaba los movimientos, los recorridos más usuales: de la mesa a la bacha, del escritorio a la biblioteca, de la cama al baño, me imaginaba cuáles serían mis rituales y mis rutinas, qué cosas haría a la mañana, qué cosas haría a la tarde.

Ella me cuenta cómo se imaginaba la casa y yo mientras tanto me imagino a Ruth caminando con cuidado entre las estacas y los piolines, con los brazos abiertos, como haciendo equilibrio, sus dedos apenas rozando las paredes fantaseadas, una y otra vez repitiéndose a sí misma, todavía sin terminar de creerlo: acá va a estar la puerta, acá va a estar la cama, esta va a ser mi casa, esta va a ser mi casa.

Mi poema favorito de James Schuyler se llama “30 de junio, 1974”. Es una especie de carta, o de mensaje de agradecimiento para unos amigos

que lo invitaron a pasar un fin de semana con ellos en su casa en el campo. Una mañana de domingo, a principios del verano, Schuyler se despierta temprano mientras sus amigos todavía duermen o se quedan haciendo fiaca en la cama. Todo está muy silencioso y Schuyler se prepara unos huevos para el desayuno, coffee, milk, no sugar. Describe la casa con unas pocas imágenes muy rápidas: la vista de un lago y unas dunas del otro lado de la ventana, una casa acogedora “llena de pinturas y plantas”. Al leer ese verso yo siempre me imagino que quiero una casa así: cómoda, luminosa, con pisos de madera que crujen y plantas y pinturas y amigos que se despiertan temprano y bajan a desayunar y saben en qué estante de la alacena están las cosas y solos se preparan un café, se hacen una tostada, después dejan la taza sucia en la bacha y salen a caminar un rato, bajan al arroyo, van hasta el pueblo y vuelven con facturas y un pan caliente bajo el brazo.

En una parte, el poema dice: “Home! How lucky to / have one, how arduous / to make this scene / of beauty for / your family and / friends”. La primera vez que lo leí subrayé la palabra “arduous”. La segunda vez que lo leí, con otro color subrayé: “scene of beauty”.

A la tierra arcillosa hay que ir a juntarla a la orilla del arroyo, en una barranca donde hay mucha y todos van y sacan y después hay que ir al campo, a cortar la paja brava y cosechar mazos enteros, que se van acumulando en bolsas y más tarde se trituran a golpe de pala hasta que cada brizna de paja queda de no más de cinco centímetros de largo. La paja se mezcla con la arcilla, con arena, con tierra cascotuda, y con baldes se trae agua del arroyo y se le agrega y se pisa hasta que se trenza bien todo y se hace un barro pegajoso entre las manos: a eso se le llama pastón y sirve para unir entre sí los ladrillos de adobe que se acomodan uno junto a otro sobre la piedra de los cimientos y así, de a poco, empiezan a subir las hiladas, una a una, hasta la altura de la rodilla, hasta la altura de de la cintura, hasta el pecho, los hombros, la cabeza, hasta que se termina y llega el momento de empezar a juntar la plata para comprar las chapas y poder poner el techo y terminar la casa.

Hay una diferencia entre estar trasplantado al valle y estar asimilado al valle. Un trasplantado intenta que acá las cosas funcionen igual que en la ciudad; un asimilado sabe que el valle tiene otro ritmo, otros tiempos, otras maneras de hacer las cosas.

A vos todavía te falta pasar tiempo acá, me dice Ana. Yo asiento y le pregunto si nunca se aburre, si no le da miedo estar ahí, sola, en medio del monte.

¿A vos te da miedo?, contraataca ella. Claro que me da miedo, sí, claro, ¿qué voy a hacer solo acá todo el tiempo? Me da miedo convertirme en un solitario amargado, en el ermitaño que nunca ve a nadie, en el viejo loco al que los chicos le vienen a robar limones a la hora de la siesta y le gritan cosas cuando pasa por la calle.

Ana se encoge de hombros. Yo nunca estoy sola, dice. Yo estoy conmigo, me dice. Yo soy mi mejor amiga, mi mejor compañía. A veces me tengo que tener un poco de paciencia, pero como a todos. Después salgo a caminar por el monte y le voy contando al monte mis cosas y se las voy entregando y, si uno sabe escuchar, el monte te responde: ves una ramita, una flor, algo que te llama la atención, que te distrae. El monte te devuelve, te saca adelante, dice Ana y después sonríe, me mira con un poco de lástima, como si yo no terminara de entender algo que para ella es casi una tontería, algo demasiado evidente, fácil.

Me dice: a vos todavía te falta pasar tiempo acá. Todavía te falta asimilarte.

¿Por qué te viniste al valle? ¿Vos también te estabas escapando de algo?, le pregunto a Ruth una tarde de invierno, muy fría. Tomamos té de manzanillas y lavanda que recogió ella misma, sobre la mesa quedaron las migas de una torta de coco y dulce de leche que compré en la panadería del pueblo y le llevé de regalo.

Ruth tarda un rato en contestarme. Después dice: a mí me gusta el monte, me gusta acá, me gustan las montañas. Yo elegí quedarme.

Asiento y no digo nada. Alrededor se va haciendo de noche y las brasas crujen en la salamandra. Es linda la casa de Ruth, se siente bien estar ahí, los dos sentados, calentitos, el monte afuera tan cerca que cuando las mueve el viento las ramas de los manzanillos y los falsos talas rozan el techo de chapa y suena como rasguños de uñitas de gatos.

Es lindo estar acá, digo después de un rato que pasamos los dos callados. Por ahora me gusta, por ahora siento que podría ser acá, pero vaya uno a saber. ¿Qué pasa si después deja de gustarme?

Si después deja de gustarte, después verás, dice Ruth.

Ojalá dure un poco este tiempo. Es lindo estar acá, digo otra vez en voz baja.

Ruth se larga a reír.

El tiempo cambia todo el tiempo, amigo.

Sí, digo yo, ese es el problema.

O esa es la gracia, dice Ruth. O esa es la gracia.

Lejos, de corazón en corazón, más allá de la copa de niebla que me aspira desde el fondo del vértigo, siento el redoble con que me convocan a la tierra de nadie. (¿Quién se levanta en mí? ¿Quién se alza del sitial de su agonía, de su estera de zarzas, y camina con la memoria de mi pie?)

Olga Orozco, “Desdoblamiento en máscara de todos”, 1962

Una tras otra, las obras que integraron el proyecto Adentro no hay más que una morada fueron apareciendo como señales capaces de demostrar que incluso en tiempos de profunda aceleración y exigencia, de desorientación y vértigo, somos capaces de provocar un momento de reunión sincera con aquello que nos rodea. Podemos salir al encuentro de algo que parece estar escrito “en el revés del alma” de todo y de todos, como escribe Olga Orozco algunos versos más adelante en su poema. A flor de piel, este encuentro tiene mucho de verdad: es el descubrimiento de una especie de esencia compartida, de un instinto relativo al modo en que podemos avanzar sobre las cosas del mundo, ya se trate de la Tierra, de nuestros objetos o de

quienes están próximos. Tal vez, a partir de ese encuentro podamos poner en jaque los modos automatizados en los que el orden social y económico nos impone desarrollar nuestra existencia.

En esos momentos, a veces breves, el mundo no se siente como algo ajeno. Las formas del mundo, su materialidad y su escala, no nos resultan extrañas, aun cuando nos encontramos con ellas por primera vez. El tiempo no amenaza con apresurarnos ni con demorarnos, sino que, de algún modo, su ritmo y el nuestro parecen estar acompasados. Esa sensación de continuidad entre lo que somos y lo que nos rodea –o ese modo de reunión con lo que hay alrededor– es evocada con fuerza por las obras que forman parte de Adentro no hay más que una morada, una exhibición que reunió el trabajo de treinta y cuatro artistas que habitan en distintas regiones de la Argentina. Sus obras, de producción reciente, o realizadas especialmente para la exposición, restauran la mirada sobre el vínculo que existe entre nosotros y todo aquello que está o sentimos cerca. Nos recuerdan que somos y habitamos al mismo tiempo, que nos desarrollamos a partir de ese modo de reunión y en sintonía con lo que puede haber alrededor –sea material o simbólico, esté más allá de nuestra piel o bien adentro– y que nuestra identidad es indiscernible del modo en que atravesamos los días y dejamos huella, así como del modo en que el exterior deja huella en nosotros.

Esa experiencia de conexión que comunican las obras, resulta, por un lado, de un acto de repliegue –de concentración en el mundo cercano y propio– y, por otro, de un acto de trascendencia que acontece cuando el valor puesto en el acto anterior proyecta, incluso de manera inconsciente, la experiencia individual más allá de sí. En su andar y en su hacer, a veces mecánico e intuitivo, pero siempre como resultado de una entrega incondicional a la labor, al contacto con sus materiales y a la investigación, estos artistas conectan cuerpos, territorios y tiempos. Sus obras pueden surgir del encuentro de su hacer con una geometría universal, de abrazar métodos de construcción que están al borde del olvido, de trabajar con materiales naturales para descubrir en ellos nuestras huellas y memoria, de restaurar el significado de objetos y palabras que guardan testimonio de su paso por el mundo, de labrar formas con ritmo casi ritual, de disponer un lugar donde pueda posarse lo invisible, o de mirar con atención y penetrar el territorio que habitan. Sus producciones son parte de su experiencia vital, los imaginarios que terminan por crear y que nos comparten recuperan el valor del arte como gesto de expresión simbólica y de la producción artística como posibilidad de abrirse a lo desconocido. Ellos evidencian que no hay distancia entre lo corpóreo y lo inmaterial, entre el

mundo físico y el emocional; por el contrario, en una época de cuestionamiento a la cultura de las conceptualizaciones dicotómicas, estos trabajos ponen de manifiesto que son vías de comunicación y de descubrimiento entre ambos extremos. Como imágenes que buscan acercarnos a algo que está, al mismo tiempo, muy cerca y más allá, sus obras recuperan la conciencia de que el sujeto es capaz de proyectarse fuera de sí y de que el más allá o lo exterior se proyectan en el sujeto: en lo propio cabe el mundo.

Producidos en su mayoría entre 2019 y 2021, los trabajos de la exhibición –y nuestra mirada sobre ellos– están atravesados por la experiencia de aislamiento en la que nos sumergió la pandemia causada por el virus del Covid-19 y que nos fijó de manera prolongada en un único lugar. Ante esta condición ineludible, que provocó distancia, encierro, quietud, pero también un arraigo que nos llevó a echar raíces profundas en las experiencias más cercanas de nuestra cotidianeidad, las obras que participan en Adentro no hay más que una morada funcionan como declaraciones de existencia. Son maneras de indicar que estamos vivos mediante la producción de signos, señales y acciones sobre las cosas y los espacios circundantes. El entorno material aparece en ellas como un campo de significación, como una zona en la que puede manifestarse un sujeto que hace patente su energía, su peso, su naturaleza emocional, su voluntad y su necesidad de identificar y componer su entorno, de reconocerse en él, de encontrar en relación con él un código o un orden común, o de leer en él un dilema o una preocupación. Abocados, entonces, a la producción de signos más que de significados, a comunicar existencia más que la narrativa de una existencia, los artistas manifiestan en sus obras una voluntad de evocar y convocar cierta fuerza vital.

El título de la exposición parafrasea un verso de la poeta argentina Olga Orozco que forma parte del poema citado al comienzo de este texto, que dice: “Desde adentro de todos no hay más que una morada”. A modo de diagnóstico sensible y contundente, este verso expresa la imposibilidad de distinguir la noción de existir de la de habitar, una reflexión que los trabajos de la exhibición traen a la conciencia y refuerzan con el valor que le otorgan a aquello que conforma la identidad y el sentido de pertenencia. Incluso en las obras que se nos presentan en forma de geometrías u otro tipo de abstracciones de apariencia universal, queda en evidencia que surgen de una localidad e intimidad particulares.

Portadoras de experiencias, de energía, de ejercicios, de labores y de mensajes, las obras de Adentro no hay más que una morada expresan el deseo

y el poder de contención inscrito en nuestro hacer y en el modo en que decidimos plantarnos en el mundo, un lugar al cual pertenecemos y que se nos ofrece como posibilidad para el descubrimiento. El título se refiere a la relación de reciprocidad que existe entre el adentro y el afuera; una relación en la que las obras indagan al revelar el mundo, ese espacio exterior, amplio y abierto, como una gran intimidad, e incluso como una intimidad que compartimos y que tiene la capacidad de ser abarcada por la experiencia individual del artista y de reflejarse en ella. En lugar de mostrar el mundo como imponente, las obras nos dan la oportunidad de pensar modos de habitarlo propios de esa escala íntima, que no fuercen ni apresuren la llegada al lugar habitado. Asimismo, cuando las obras proponen un encuentro con lo más hondo y particular, con los detalles, también se dirigen a un adentro abierto y expansivo, infinito, al que accedemos con la mirada atenta, el tacto, la escucha o la búsqueda de imágenes y de experiencias que nos atraviesan como un canal que vincula energías y materias. En ese puente que las obras son capaces de trazar entre interior y exterior se expande la morada. Ella puede estar siempre adentro o puede ser aquello que está ahí afuera, porque su acción es capaz de convertir todo en morada. Las obras, como mensajeras de ese poder, revelan así que es desde ese lugar íntimo que podemos manifestar nuestra capacidad de transformar la realidad e invitan a pensar el arraigo como forma de resistencia.

Desde el interior de los espacios habitados y haciendo uso de todo aquello que los compone, varios artistas dejan sobre sus obras inscripciones y señales que funcionan como testimonio de su existencia y de su intimidad. Labores domésticas y objetos que forman parte de su cotidianeidad reaparecen en sus trabajos y crean paisajes emocionales a partir de aquello que constituye su día a día. Este panorama de lo elemental –hecho de rutinas y necesidades básicas, de objetos comunes, de procedimientos aprendidos comunitariamente, de actos naturales de cuidado hacia las cosas del hogar– pone en evidencia el modo en que nuestra identidad se define como una forma de ser y de estar, una negociación entre cuerpo y espacio que es, en parte, propia y, en parte, impuesta por las condiciones materiales del entorno. Estas obras, hechas de retazos, escrituras simples y capturas sensibles de aquello a lo que

usualmente no se le presta atención porque es volátil o minúsculo, muestran que cada acción, imagen o voz contiene la posibilidad de abrir un canal para sumergirse en otro estado u otro mundo.

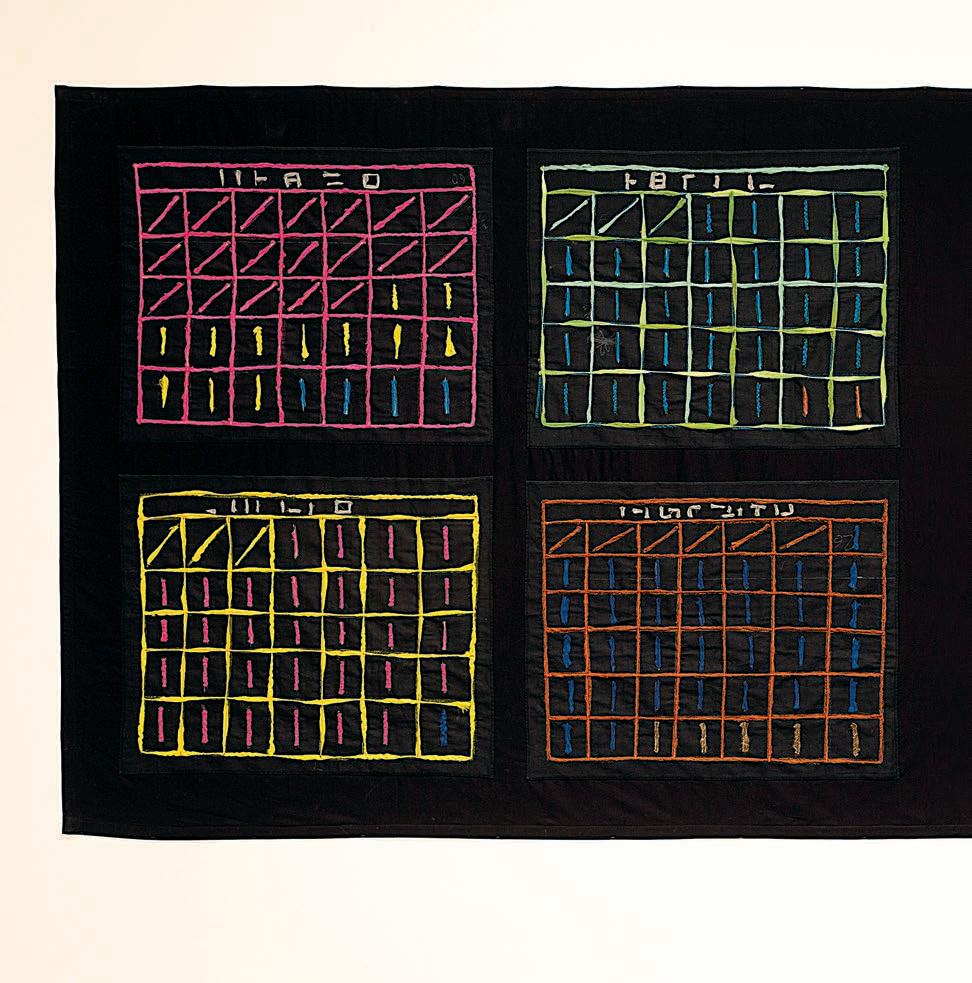

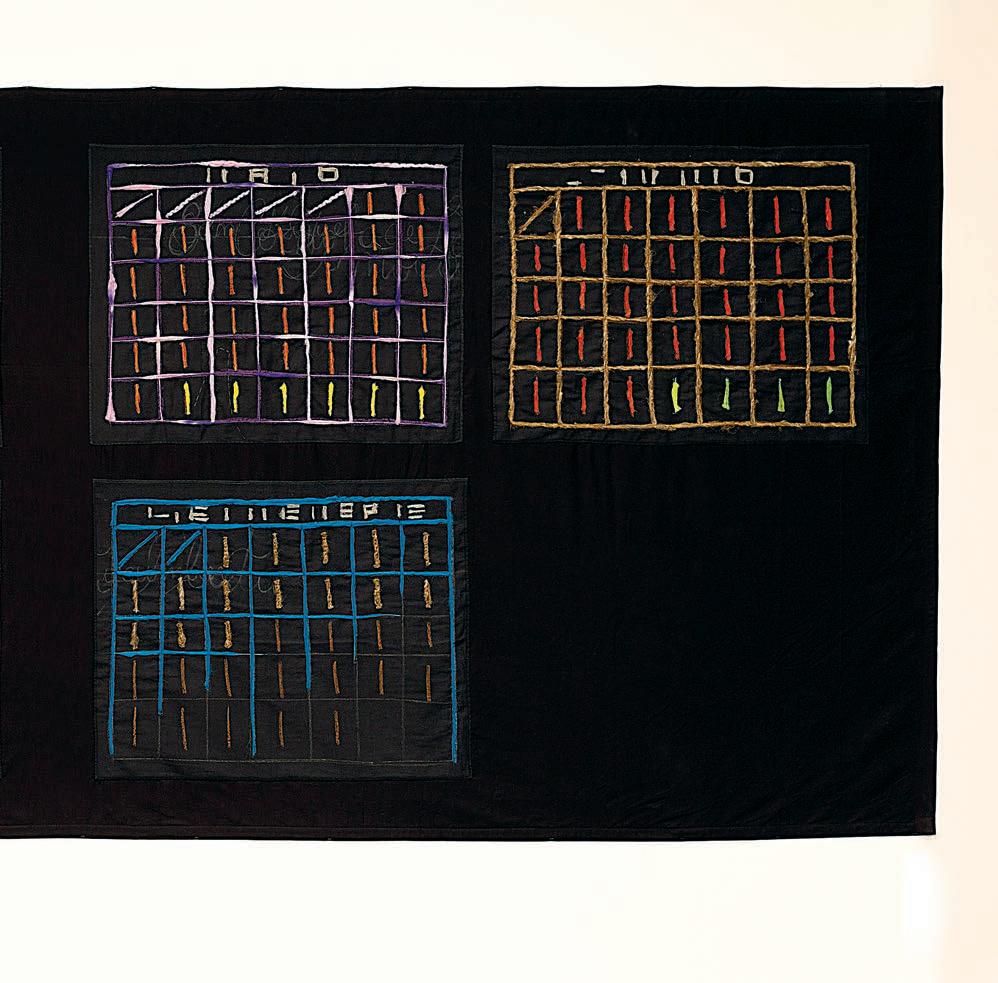

De esta particular combinación entre labor automática, entrega al tiempo y hasta búsqueda de embellecimiento de los objetos de los que nos rodeamos, creció el Calendario abstracto de Lucrecia Lionti: una tela negra de gran formato sobre la que una cantidad infinita de puntadas dibujó hasta siete grillas típicamente identificables como almanaques. Dentro de ellas, se sujetan otras líneas verticales y diagonales de lana que no tachan ningún tipo de actividad realizada. Apenas se acumulan como marcas y buscan interrumpir la monotonía del dibujo geométrico con algún hilo brillante y una variedad de colores que transforma el panorama de otro modo vacío, vistiendo de amarillos, dorados o fucsias su rigor minimalista. Las líneas rectas y los zigzags que dibujan hilos y lanas dan dimensión visual al tiempo transcurrido, lo miden, transformándose en una especie de “cronografía”, un diagrama blando, construido a partir de un ejercicio ritual en el que la costura, el medio que más claramente evidencia el tiempo, se construye como tema, es esqueleto y forma.

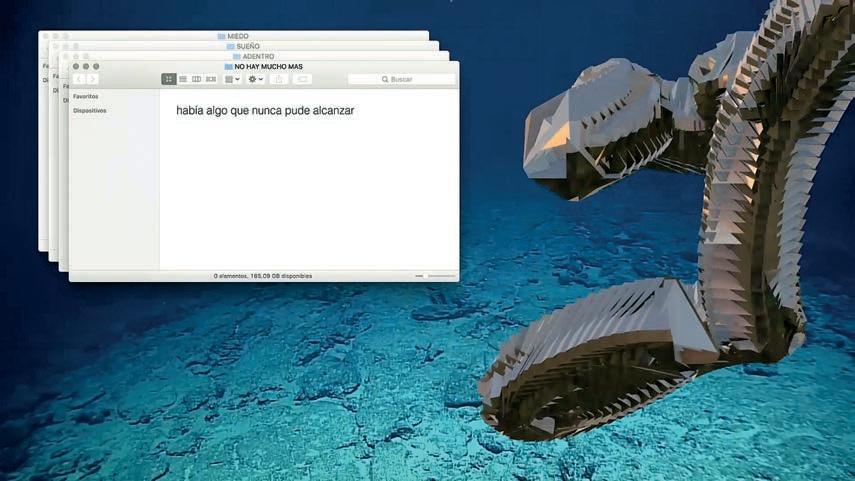

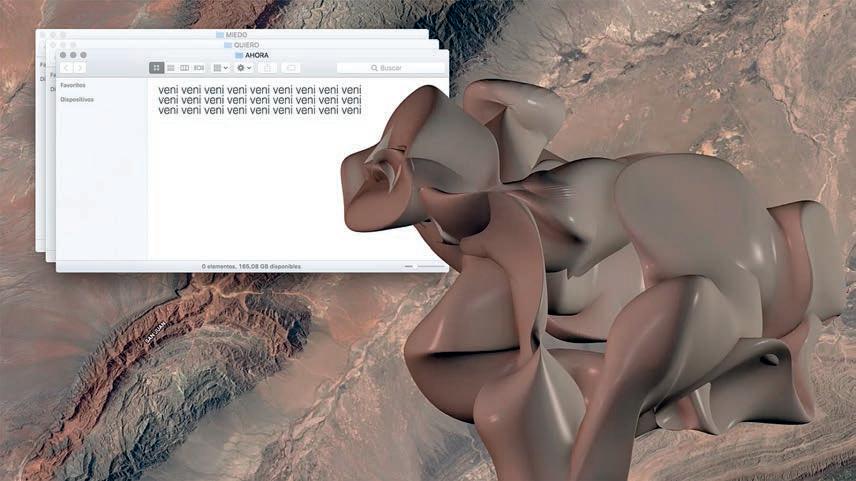

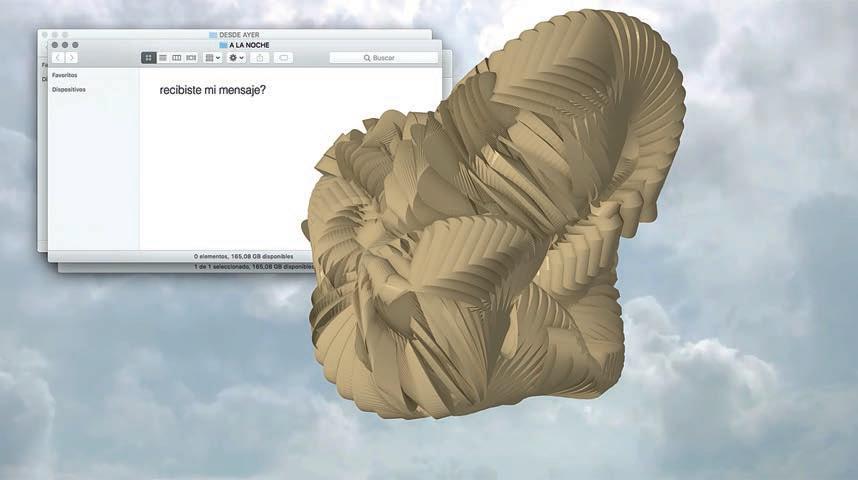

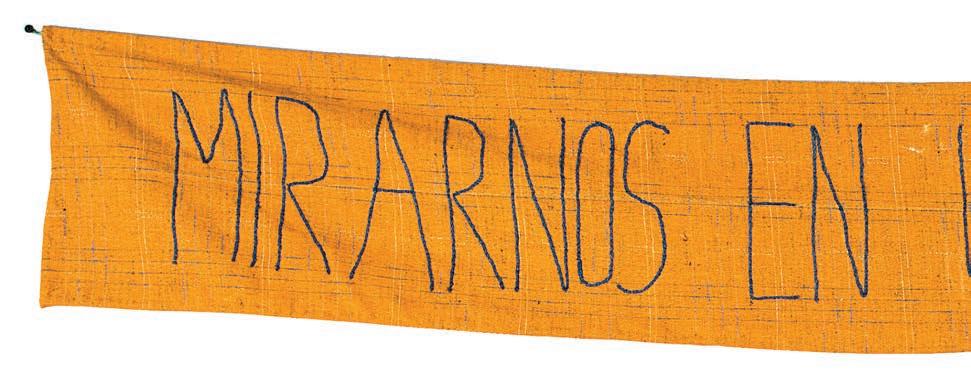

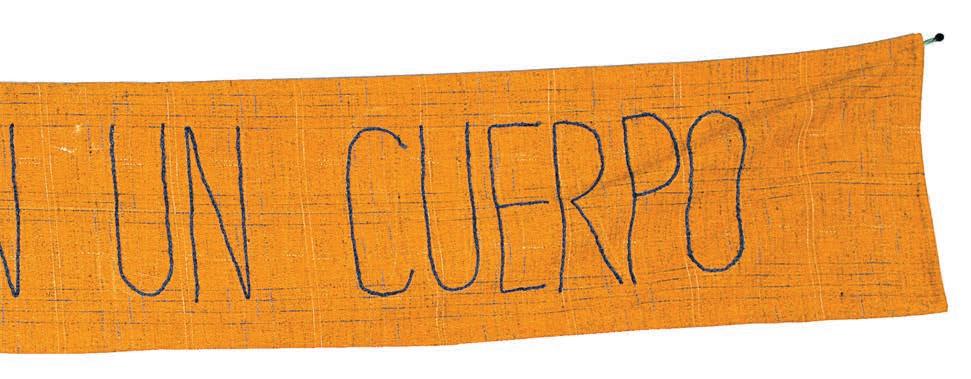

Esta desnudez que sufren procesos y lenguajes, y que lleva a los medios de expresión a un estado elemental, reaparece en los mensajes enigmáticos y sugerentes de las obras de Florencia Vallejos y Daniela Rodi que, en su despojo, son incluso emitidos por voces anónimas. Su ambigüedad y abstracción permiten a su vez llenar esas palabras con sentidos y deseos propios, y desplegar la interpretación o una conversación al infinito. En Mis documentos, de Vallejos, los mensajes se abren dentro de carpetas de archivos de computadora que podrían desplegarse de manera inagotable, mientras que los de las telas con formato de pequeño pasacalle de Rodi –una de las cuales propone hacernos una imagen mental de la frase “En la coincidencia de lo bello”– se multiplican por la apropiación que cada lector puede hacer del texto. De tono poético y afectivo, incluso hipnótico, esta proyección de voces más allá del espacio físico que habitan o del tiempo en que fueron emitidas, acorta la distancia que nos separa de otros, subrayando la capacidad de las palabras para mantenernos conectados.

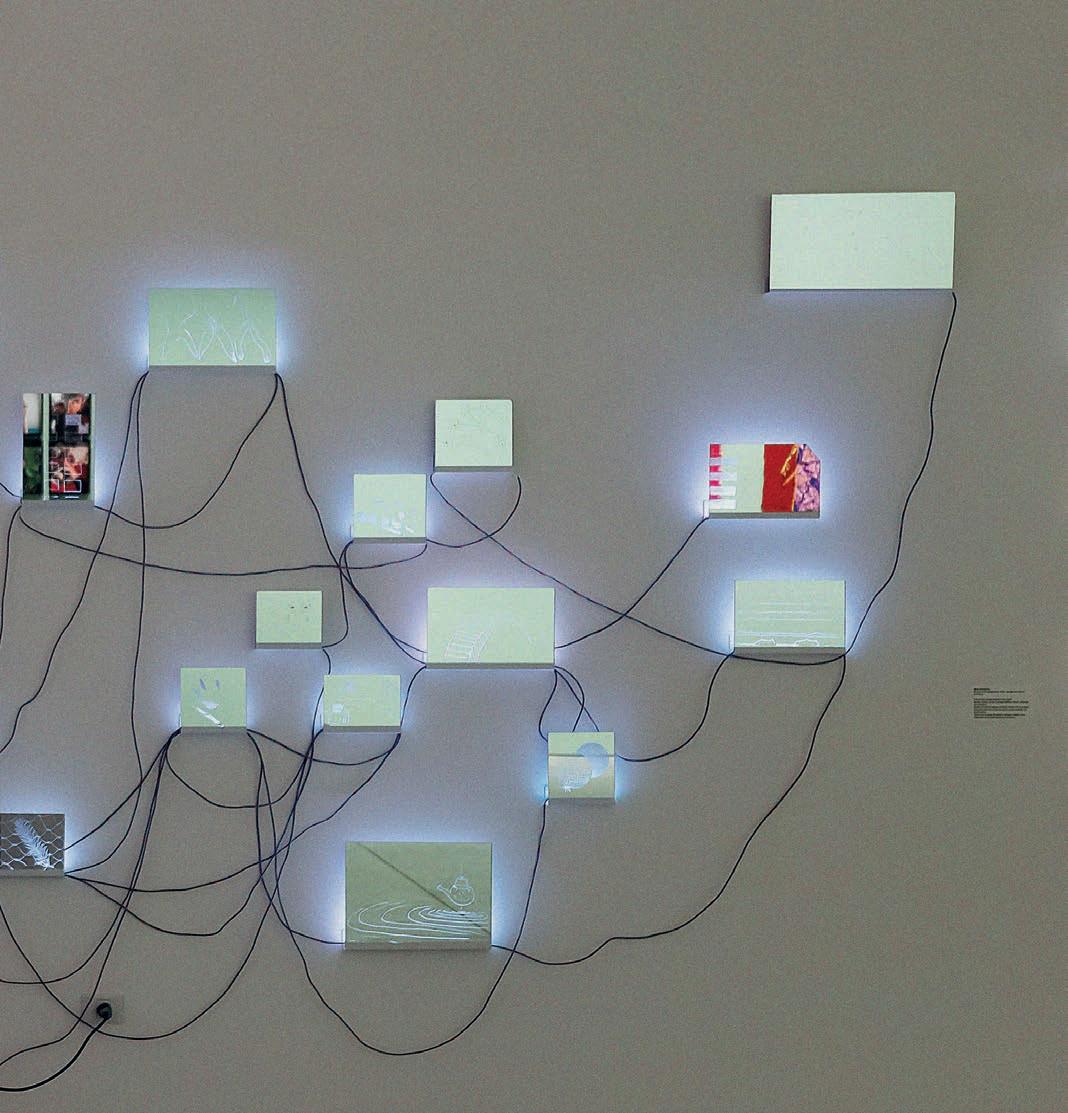

Esta inclinación al contacto es compartida por las fotografías de la serie “Selfins”, de Nina Kovensky, que continúa agrandándose en su proceso de acumular cada vez más imágenes tomadas por celulares –“selfies”– de rostros de amigos confinados en espejos diminutos, con los que ella parece comunicarse desde lejos gracias a que son proyectados tanto por los

espejos como por los teléfonos. En su Pulmón de manzana, otra multitud de espejos se despliega como pantallas interconectadas y recrea desde lejos la vista de un paisaje de ventanas en la ciudad, aperturas hacia mundos privados. Un juego de luces que se emite por detrás de ellos marca, por un lado, los tiempos de la vigilia y del sueño –la hora en que todo despierta, los momentos de actividad y el descanso, destellos de un ciclo vital– y, por otro, permite descubrir dibujos grabados sobre sus superficies que componen un imaginario de lo cotidiano, ahora brillante e iluminado.

A pesar de que en Vallejos y Kovensky el uso y la representación de la tecnología no se desprenden del todo de la visión distópica que trae aparejado su uso individual y solitario o la amenaza de la invasión de nuestros datos, ambas artistas hacen foco en su dimensión sensible. La utilizan como un medio capaz de dar cabida a formas de expresión poética; la tecnología es emisora de luz, espacio de guarda de lo íntimo y canal para hacer posible un encuentro.

Creadas en muchos casos a partir de la acumulación y la repetición de una misma forma, un mismo objeto o una misma situación, estas obras ponen en evidencia la dimensión social de las experiencias individuales. El uso de módulos formales sobre los que se despliegan leves variaciones se hace eco del ritmo y el ciclo compartido en los que cada una de esas experiencias se desarrolla. El detenimiento en el detalle y el tono de las obras también traen a primer plano la sensibilidad y delicadeza implícitas en la domesticidad, cuya necesidad de cuidado y protección queda representada de manera singular por el trabajo de Lucía Reissig y Bernardo Zabalaga, quienes trabajaron en la exhibición antes de que esta abriera al público en un encuentro celebratorio y ceremonial con los artistas. En él, y a partir de sus múltiples experiencias en la limpieza energética y de espacios, se buscó acercar a cada uno de los presentes –así como el proyecto que compartimos– a un estado de bienestar capaz de extenderse en el tiempo. El talismán presente en la sala de exhibición no solo se exhibe como memoria de esa reunión ritual, sino también con el fin de potenciar el cuidado de las obras y la exhibición.

Muchas producciones surgen de la necesidad de reconocer y proteger la identidad, y ponen el foco en aquello que, aun cuando es frágil e inestable, define el mundo propio. Estas creaciones no resultan, sin embargo, de la representación de ese mundo, sino de la utilización de lo que los artistas

acumulan –pequeños objetos, pero también palabras, historias, experiencias, ideas, imágenes– y de su reorganización en formas diferentes, lo que multiplica el valor de esos elementos y los vuelve la esencia de imaginarios nuevos. De esta manera, resignifican el universo personal y lo proyectan en el tiempo, dándose la posibilidad de dejar un “mensaje a la nada y al todo”,1 tal como describe su motivación el rosarino Carlos Aguirre.

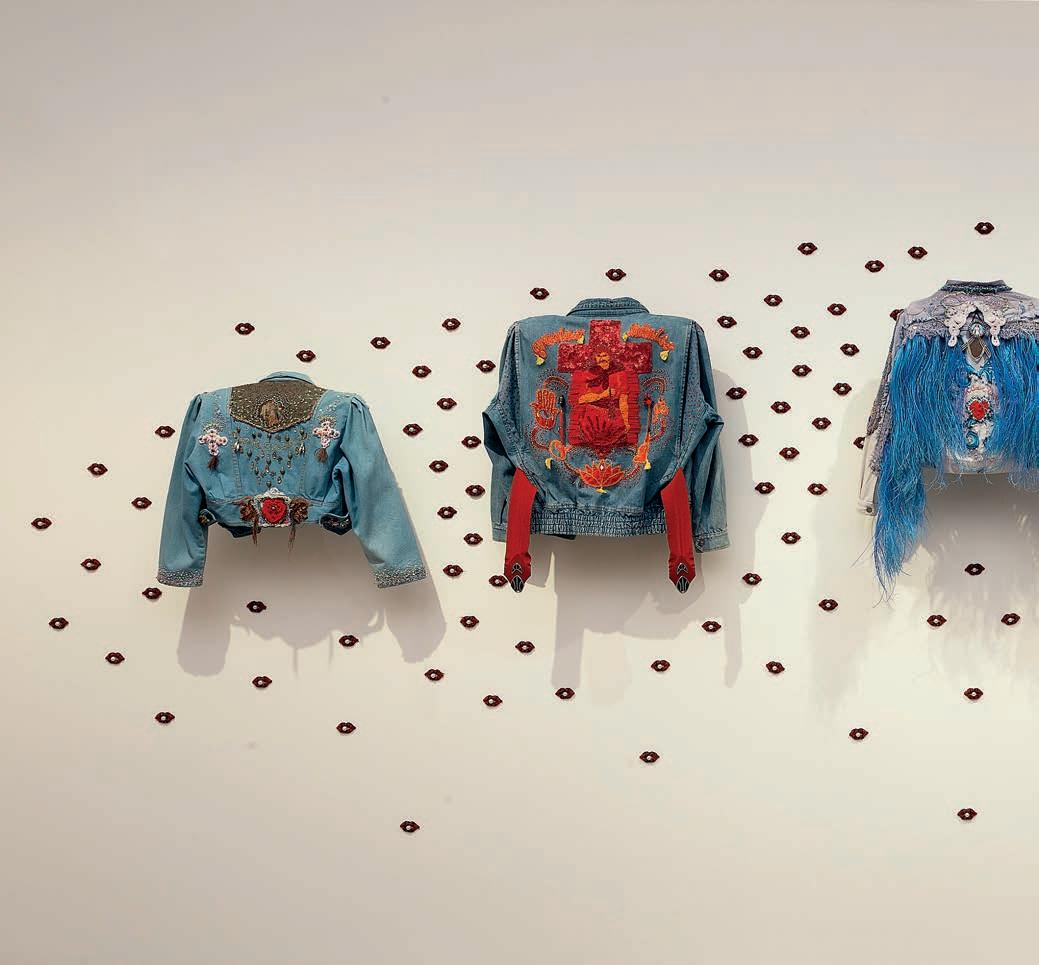

De esa acción resultan, por ejemplo, los deslumbrantes “Altares portables” con los que propone abrigarnos Blas Aparecido. En ellos traslada la territorialidad de los altares populares y la tradición del carnaval a prendas que su amoroso trabajo de bordado termina por transformar en exvotos magníficos y personalísimos. Estos reúnen fragmentos de oraciones, promesas o poemas, aplicaciones de figuras religiosas y devocionales, además de objetos personales que guardan valor afectivo.

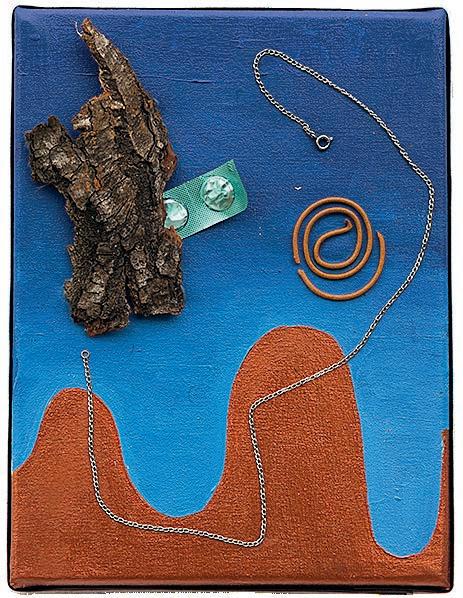

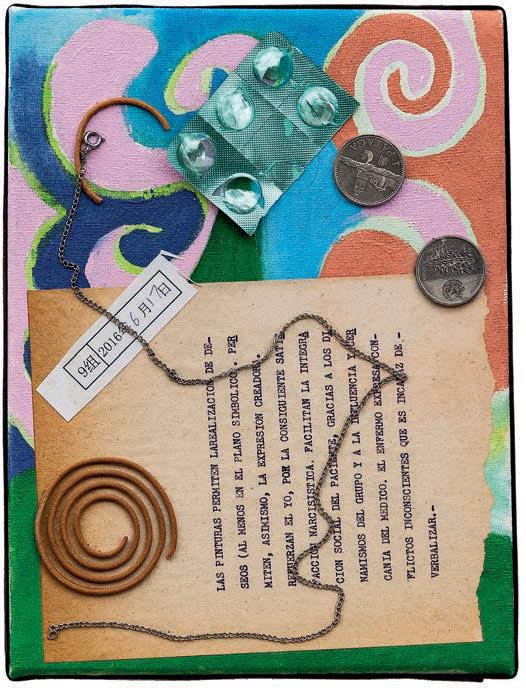

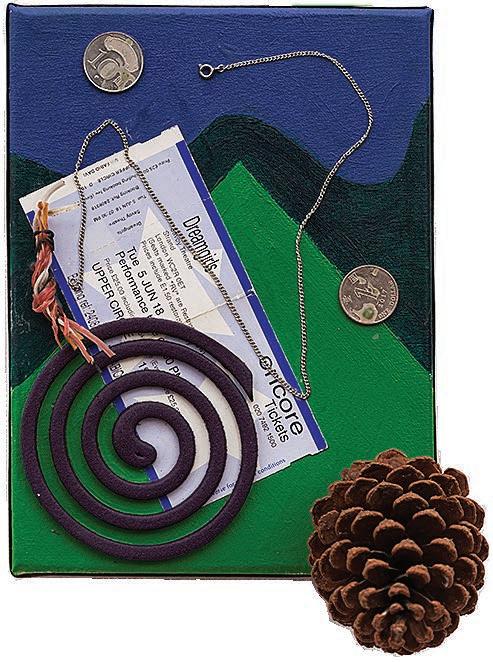

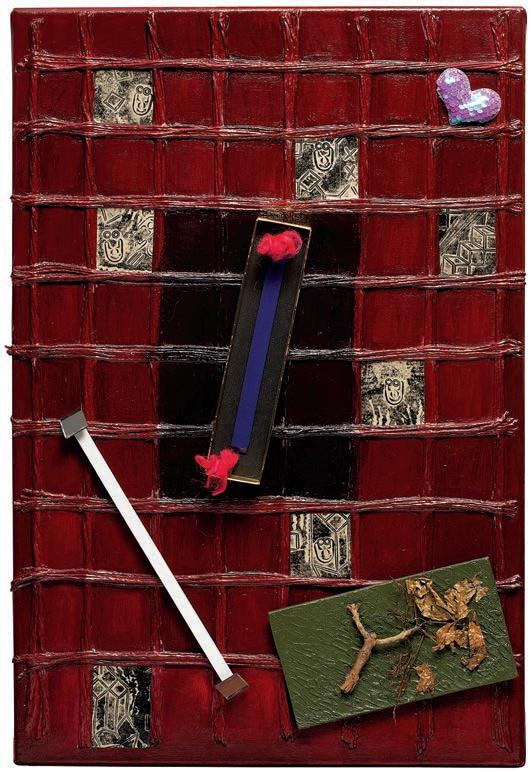

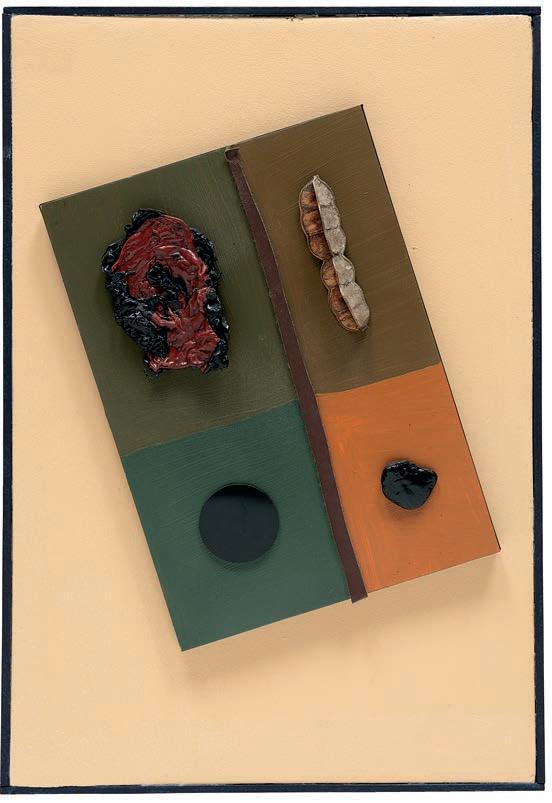

La serie de pequeñas pinturas titulada “Collages y mesas revueltas” del artista e investigador Santiago Villanueva, por su parte, combina sin preocupación inciensos, repelentes espiralados de insectos, una variedad de textos impresos acerca de la práctica artística, entradas a discotecas, mates, blísteres vacíos o pedazos de corteza sobre superficies pintadas con formas orgánicas y planas. El azar con el que los objetos parecen haber sido derramados termina por conformar paisajes fantásticos, hechos de restos que pudieron haber estado guardados en cajones o bolsillos y que combinan episodios de su vida personal con sucesos de la historia del arte local. Crean, así, un nuevo tipo de archivo visual que vincula teoría estética y afectividad.

Este rescate de aquello de lo que resulta imposible desprenderse, pero se demora en encontrar su lugar, guía también la producción de pinturas y esculturas de Carlos Aguirre. En su trabajo, los desechos abandonan su condición de resto o de “fin” para convertirse en los principios de una aventura plástica que retoma el espíritu formal de la modernidad y otorga sentido a los elementos incorporados –sean un trozo de telgopor o una hebilla de su hija–, además de fijar el valor personal que tienen. En cada una de estas prácticas, el acto creativo tiene sentido vital: hay un afán de finalidad, una voluntad de reunir los ingredientes de esos mundos personales con un destino mayor a través de las construcciones, imágenes, paisajes, naturalezas muertas o abstracciones en los que la labor artística puede alojarlos con naturalidad.

1— Correspondencia con el artista, 12 de septiembre de 2021.

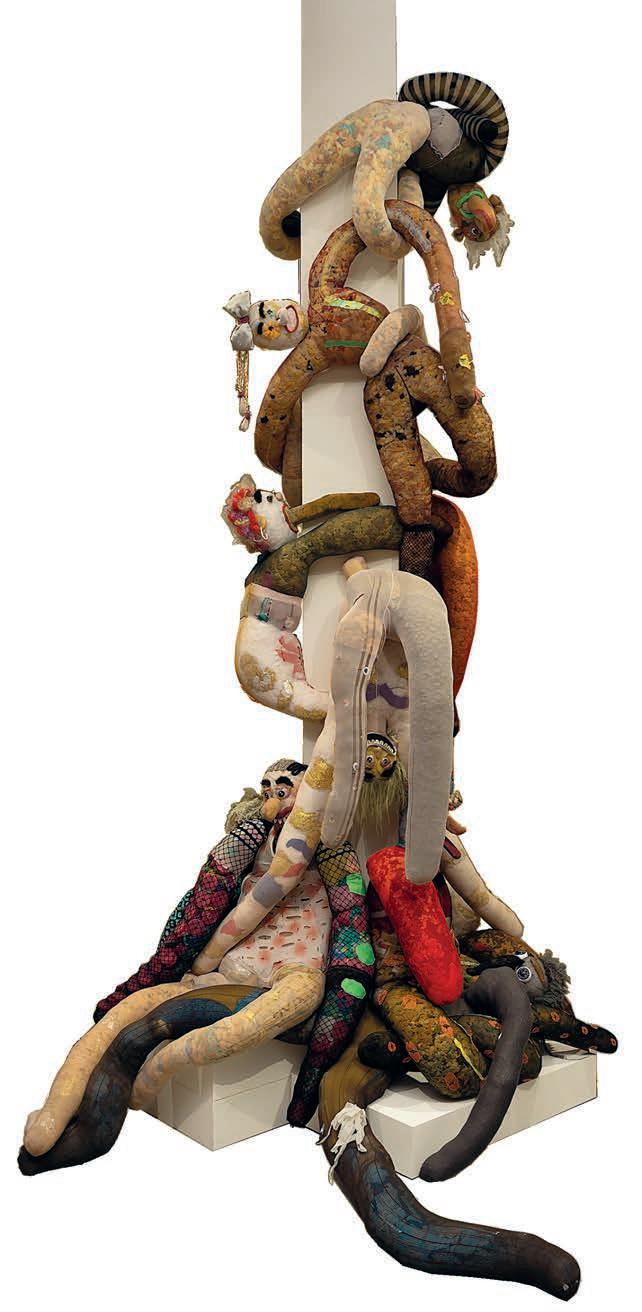

Por otro lado, el clan de figuras blandas de compañía creado por Dana Ferrari también surge de la reutilización de materiales que ella guardaba en su taller para sus trabajos como realizadora y que, en un acto de reinvención, pasan a formar los cuerpos desarticulados de “Los mareados”. Con ellos, que pasean entre su taller y la casa de amigos o “tutores” a quienes los da en adopción (un acto de generosidad y humor durante la pandemia a través del cual la artista pudo también hacerse presente en los hogares de sus afectos), Ferrari busca activar vínculos afectivos, “convocar, por imitación, al descanso de la verticalidad”2 y volver la vista sobre nuestro espacio cotidiano, un espacio que ellos observan con sus rostros payasescos, caricaturas de cierto sentimiento de horror ante el tiempo presente.

Este tipo de cuerpo híbrido, hecho de fragmentos, por momentos cálido y por otro lleno de crudeza, aparece también en la obra de Gala Berger. Mediante la combinación de telas para la confección de prendas y accesorios domésticos con otras que llevan impresas imágenes que provienen de animaciones digitales, sus textiles exploran la creación de nuevas estructuras organizativas y de un nuevo modelo humano. Este modelo, lejos de presentarse frío y maquinal, flota sobre la calidez que le otorga la técnica del quilting o collage textil usual en los hogares de Costa Rica, donde estaba viviendo cuando produjo estas piezas. De este modo, la artista carga con una nueva sensibilidad las instituciones del orden político, a las que se refiere en los títulos de cada tela.

Estos artistas promueven una modalidad afectiva del collage y del assemblage con la que recuperan formas tradicionales del arte, a veces a partir de producciones casi artesanales. Sin caer en una contradicción –muy por el contrario, reuniendo en sus obras medios de producción que durante mucho tiempo se mantuvieron ajenos–, la raíz material y técnica de sus trabajos sugiere que gran parte de la autenticidad y originalidad de la obra de arte y de su capacidad transformadora surge de la experiencia íntima y local, así como del aprovechamiento de los recursos, herramientas y métodos de producción que tienen a su alcance, en ocasiones, de gran sencillez y propios de la realidad económica de la que participan. A partir de estas nuevas asociaciones, los elementos reunidos en su tránsito por el mundo redescubren su potencial de belleza y protección, junto con su valor artístico, histórico y social.

2— Correspondencia con la artista, 19 de agosto de 2021.

El encuentro con la materia permite explorar cómo la afectan las fuerzas de los cuerpos que la rodean o de qué manera lleva inscrito el rastro del tiempo. Al trabajar con arcilla, yeso, parafina, escombros o imágenes del territorio, o al observar la calma y el movimiento en la materia circundante, algunos de los artistas ensayan formas primarias de registro y de expresión que encauzan su capacidad de comprender y construir símbolos y, al mismo tiempo, de abrirse a lo desconocido.

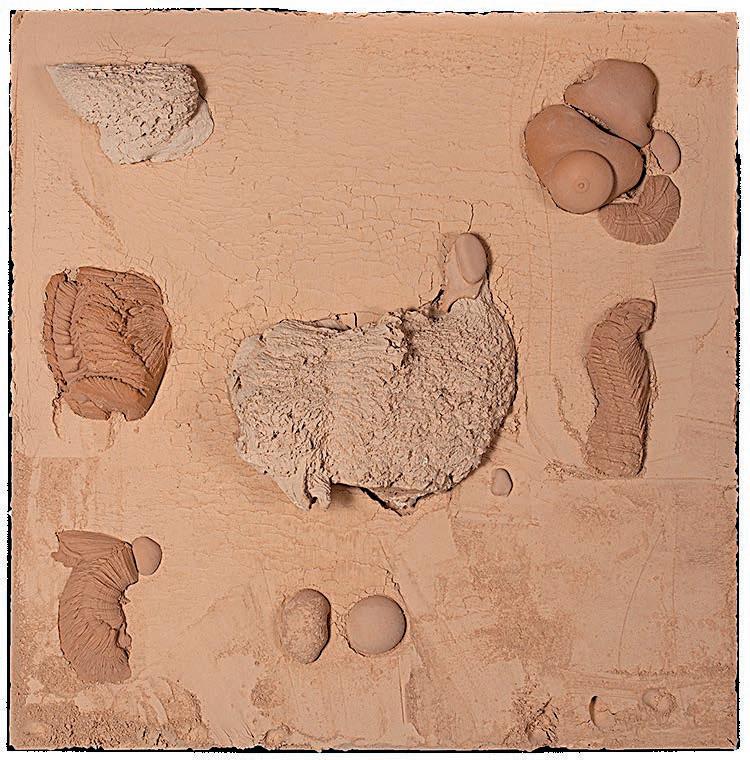

Nacha Canvas descubre rasgos de continuidad entre tiempos y organismos. En sus formas de arcilla –desplegadas sobre una superficie de polvo que las traslada a un estado primigenio de pura potencia creativa–se manifiesta la capacidad de mutación infinita de los cuerpos y, al mismo tiempo, se redescubre la sensualidad de las figuras puras y orgánicas trabajadas sin alterar lo que el material tiene de esencial. Incluso sin ser testigo del acto de producción de sus formas, el espectador reconstruye la sensación táctil que evoca la instalación, a través de la cual es posible reconectarse con modos de trabajo artesanal, que manifiestan su riqueza en la sorpresa y exquisitez formal a la que ella llega con cada una de sus pequeñas piezas. Esta inteligencia y energía latente en lo inorgánico vuelve a estar presente en muchas otras obras: la materia, activada por la mirada o por el tacto, se presenta como algo vivo, capaz de proyectar la memoria de otras entidades o de otro tiempo y volverse residual o fantasmal, así como monstruosa y totémica.

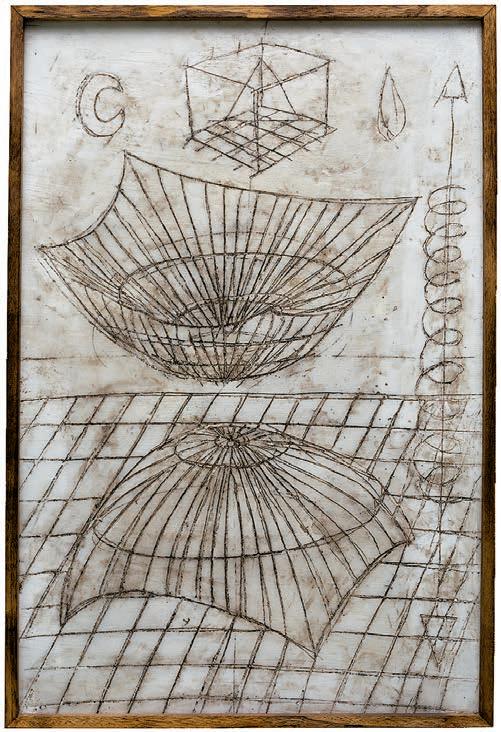

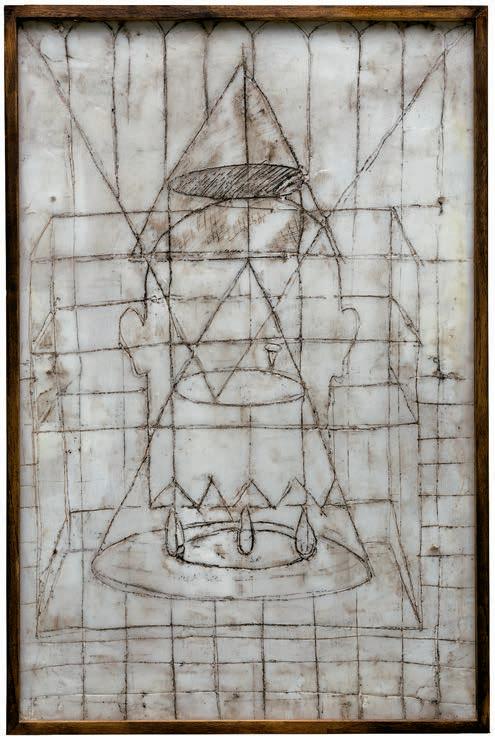

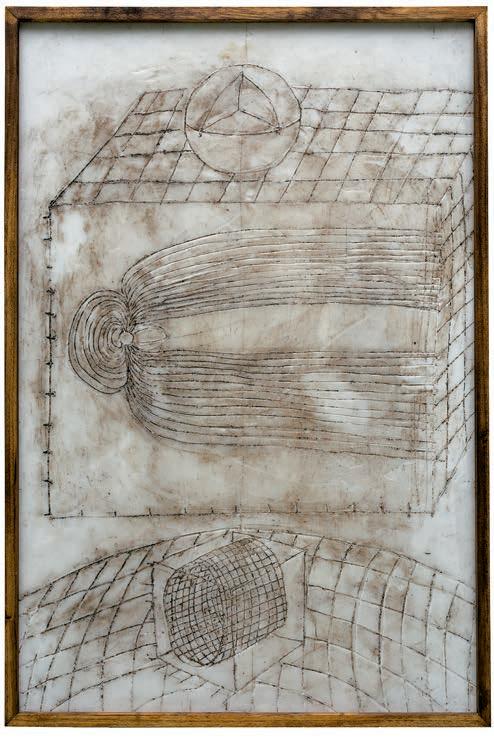

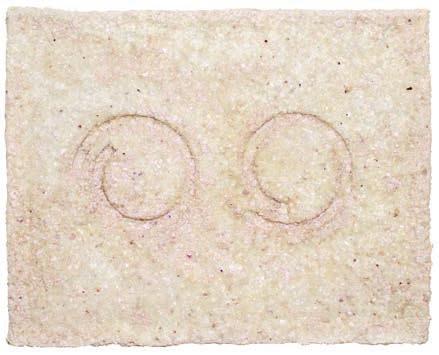

A partir de un ejercicio gestual, Benjamín Felice talla sobre una superficie de parafina dibujos que solo logra ver con claridad cuando echa sobre ellos tierra seca, que se impregna en las líneas. Produce, así, gráficos como conjuros: en ellos se combinan gesto y geometría, códigos abstractos y símbolos personalísimos que vinculan el acceso al mundo psíquico con la producción de conocimiento. Enigmáticas pero sugerentes, sus imágenes guardan episodios de la historia personal, como lo hacen las cicatrices o los tatuajes, y develan una búsqueda de conocimiento solamente posible en ese encuentro entre cuerpo y materiales.

En su serie “La lengua de las piedras”, Florencia Palacios también ensaya formas de perpetuar señales efímeras. Sobre piedras recogidas en la costa de una laguna en Santa Fe, talló pacientemente emojis que retratan estados de ánimo o historias ligadas al tiempo de la pandemia. Al hacerlo, otorga permanencia y continuidad a un modo de comunicación propio del desarrollo

de los dispositivos tecnológicos y definido por su carácter inmaterial. Con esta acción, la artista pretende eliminar el carácter pasajero de sus mensajes, volviendo a un material que, como ella misma expresa, “siempre estuvo ahí”.

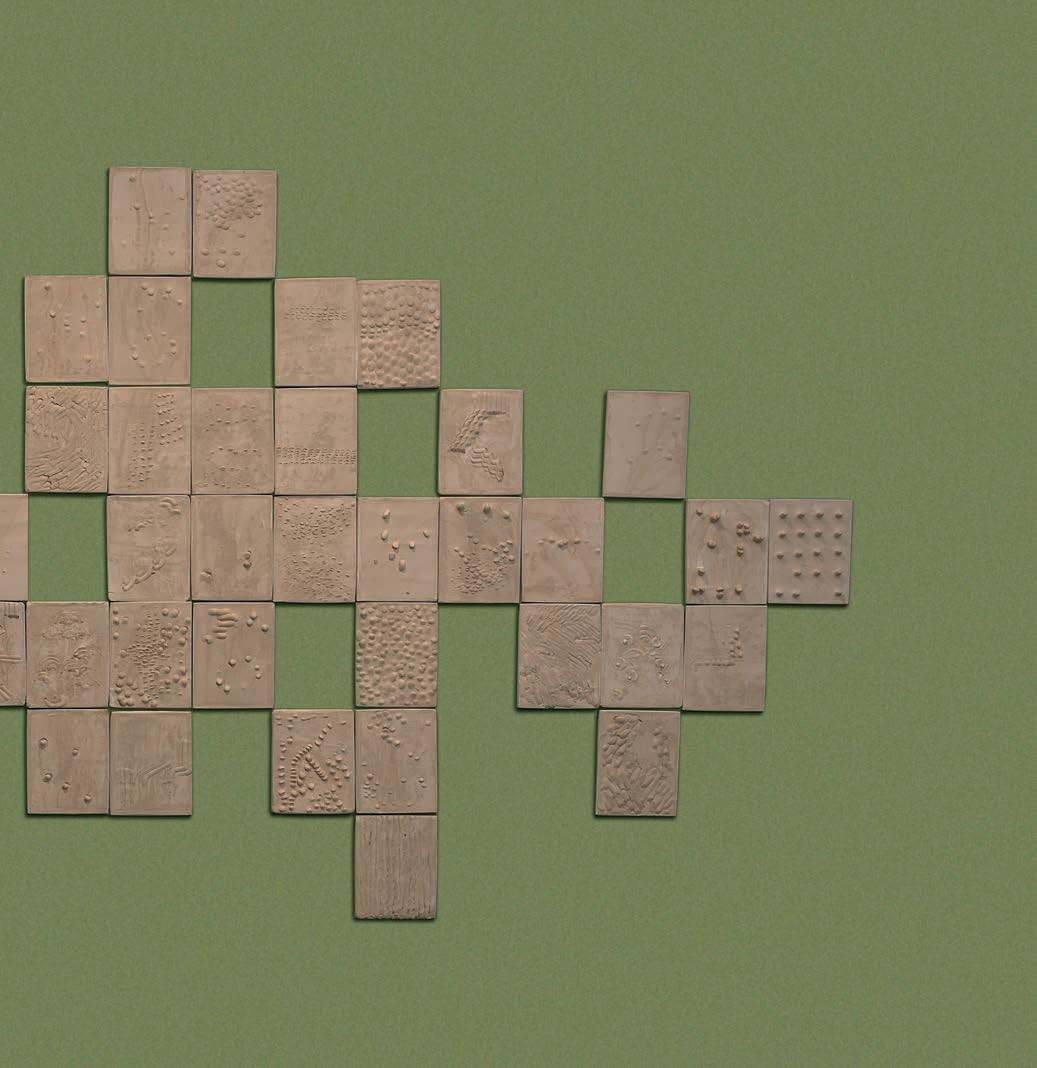

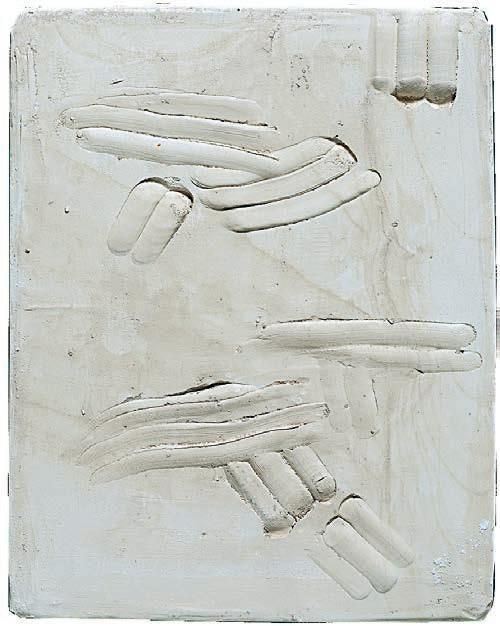

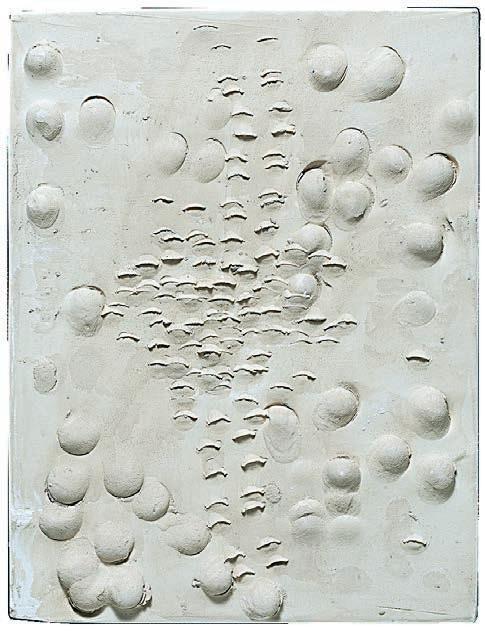

El deseo de dejar huella sobre el paisaje y la arquitectura, de hacer contacto con superficies estables y nobles, se hace también presente en el trabajo de Florencia Caiazza. En él, las marcas de sus dedos se despliegan sobre docenas de piezas de yeso que recubren la pared como cerámicos. El motivo ornamental y repetitivo característico de estos revestimientos es reemplazado aquí por gestos irrepetibles que quedan guardados en el yeso. Además, la acción exploratoria que se manifiesta en el encuentro entre dos fuerzas –la propia de la artista, a través de su mano, y la del material sobre el que presionan los dedos– evoca la función primaria del tacto como método de aprendizaje.

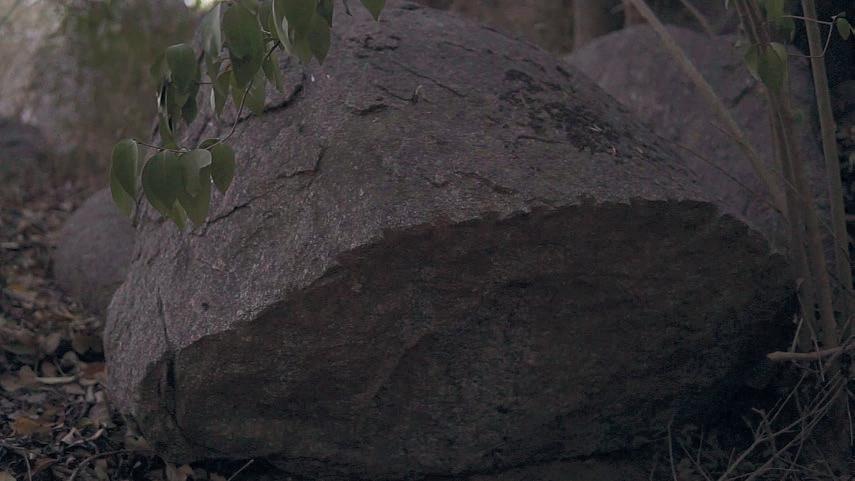

Por su parte, Francisco Vázquez Murillo concentra en sus pequeñas esculturas –realizadas mediante el encastre de varillas de hierro descartadas de sitios de construcción sobre escombros erosionados hallados en las costas de Buenos Aires– una reflexión sensible sobre nuestros modos de escritura: aquella que realizamos sobre el paisaje como resultado de nuestro acto de habitar, firme y vertical, y otra hecha de signos, de cuya producción pareciera que no podemos escapar. En este caso, es lo que resulta de un juego de encastre casi intuitivo, con voluntad de orden. Alineadas sobre un estante que funciona como horizonte, las figuras –que son pequeñas edificaciones– se despliegan como antenas que conectan cielo y tierra, pero también como un alfabeto de formas moldeadas por el ser humano, el tiempo y la naturaleza. Estas tres esferas convergen también en la obra de Juan Gugger, cuya compilación de videos 2020-2021 abre la posibilidad de explorar la quietud y un presente absoluto mediante la observación de inmensas piedras, que incluso ensayó construir con sus propias manos para lograr comprender de dónde provienen su singularidad y expresividad. Estas formas imponentes, imágenes de la inmovilidad que experimentamos durante ese par de años, permiten que el artista represente y explore maneras de habitar alejadas de la permanente necesidad de movimiento, información, producción y consumo que domina la vida actual. Si bien la imposibilidad de movimiento puede también entenderse como un obstáculo para nuestro desarrollo, la visión de estos volúmenes rocosos que se imponen con la autoridad de un tótem permite penetrar en un tiempo no humano de transformación y participar del modo en que estas formas entablan, gracias a su quietud, un diálogo pleno con el

entorno. Aire, luz, vegetación y agua se proyectan y viven sobre esas piedras hasta volverse parte indisoluble de su naturaleza.

Si bien la desnudez casi completa con que la mayoría de los artistas presenta sus materiales proporciona una sensación de universalidad y permanencia, también les confiere a las obras cierta cualidad de ruinas. Estas resurgen, amenazantes, en el video de Agustina Wetzel, mediante la compilación de múltiples escenas de demolición recogidas de internet que ella reproduce en reversa. Lo que vemos, entonces, es un espectáculo monstruoso en el que edificios que han perdido su carácter de vivienda se levantan, monumentales, desde el polvo. De este modo, Wetzel pone en crisis el afán de construcción y destrucción que resulta de nuestro apetito de perpetuidad, y lanza una señal de alerta respecto de la violencia y de los desajustes que pueden resultar de las políticas de gentrificación, en tanto emprendimientos políticos o comerciales.

La quietud impuesta por la pandemia trajo una nueva conciencia sobre el propio cuerpo y su capacidad de autopercepción. Acotado por los límites de circulación en el espacio público, el cuerpo viajó dentro de sí mismo, orientó sus sentidos hacia su interior infinito o proyectó sus funciones y cualidades fuera de sí.

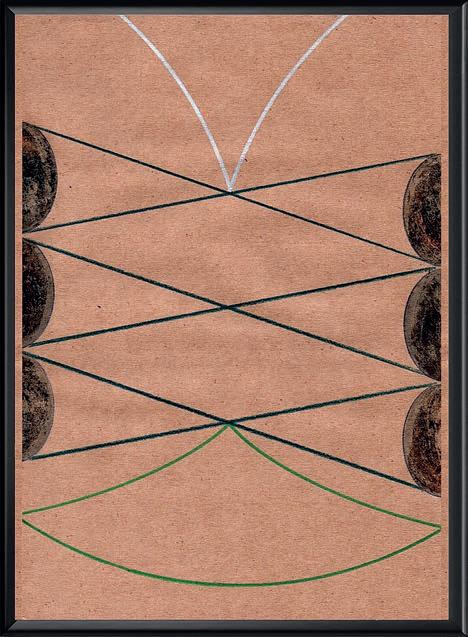

En las pinturas de Gonzalo Beccar Varela –planos casi completamente abstractos, excepto por unas referencias muy sintéticas a las formas de los ojos o los oídos–, los sentidos se duplicaron para ofrecer, tanto al artista como al espectador, la oportunidad de ser mirados, tocados o escuchados por otro. La pintura dejó de funcionar como ventana para transformarse en una superficie que nos mira, interpela y acaricia, creada a partir de un calco del cuerpo o de las proporciones del cuerpo del artista, que oficia, en sentido amplio, como creador.

Al igual que en la obra de Eugenia Calvo, estos trabajos invitan a pensar en la importancia del encuentro de otro y con otro, en el reconocimiento de uno mismo en otra figura afín, como forma de contención capaz de apaciguar la ansiedad o la sensación de soledad y desamparo. La instalación de Calvo, en la que muebles fragmentados y electrodomésticos típicos del hogar componen sobre el piso de la sala un cuerpo adulto y uno infantil en reposo, manifiesta, además, la obsesión

por descubrir rostros en todos lados, la necesidad de vernos a nosotros mismos y a nuestra experiencia multiplicados, y también de caricaturizar esa experiencia. En este sentido, Calvo comparte el humor de las figuras de Dana Ferrari, tiernas, ridículas y agudas. Sus cuerpos desganados y agotados solo dan aviso de estar activos en los rostros figurados con bananas y manzanas, griferías o accesorios infantiles que ella filmó como encuentros casuales en su casa.

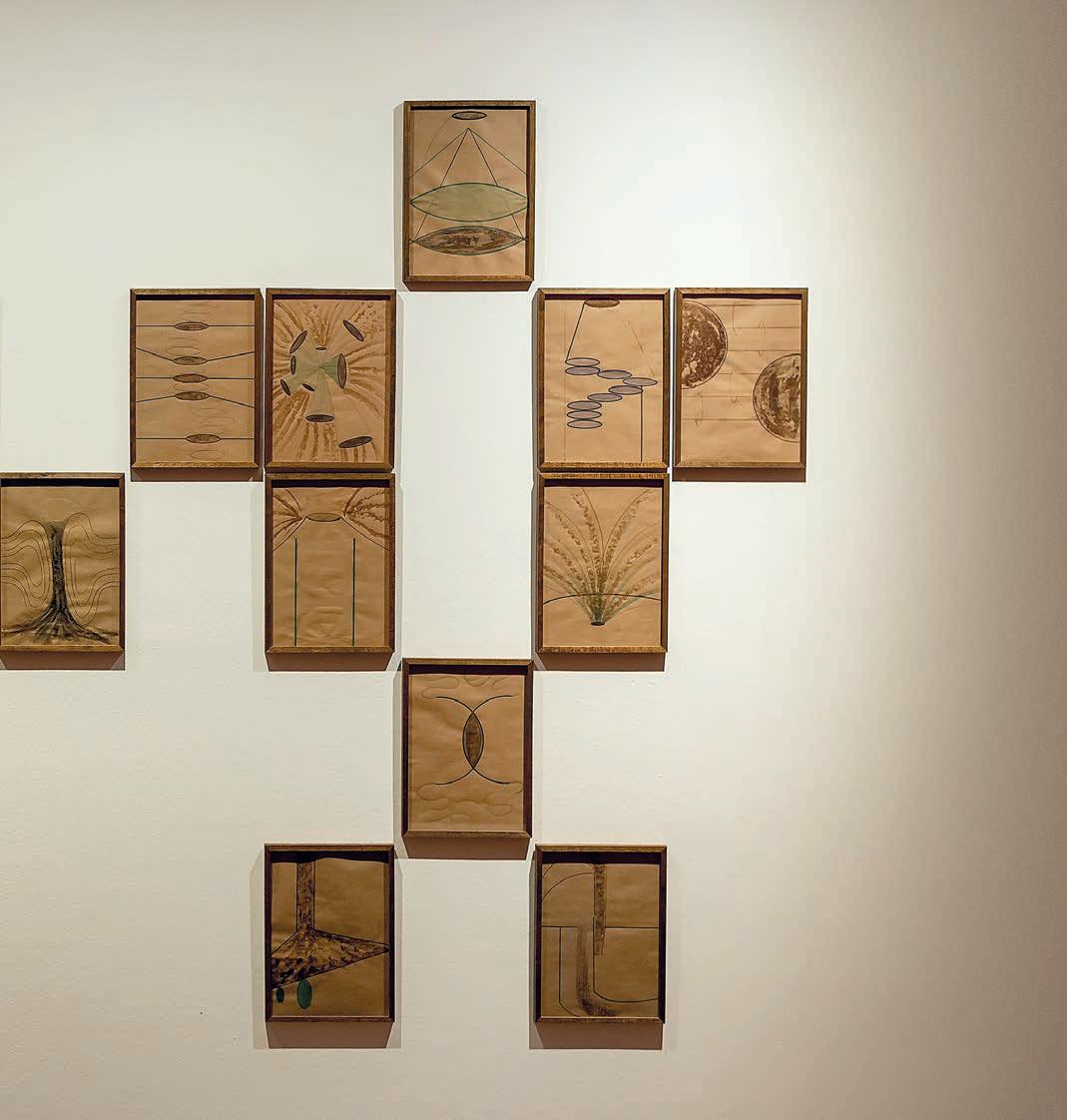

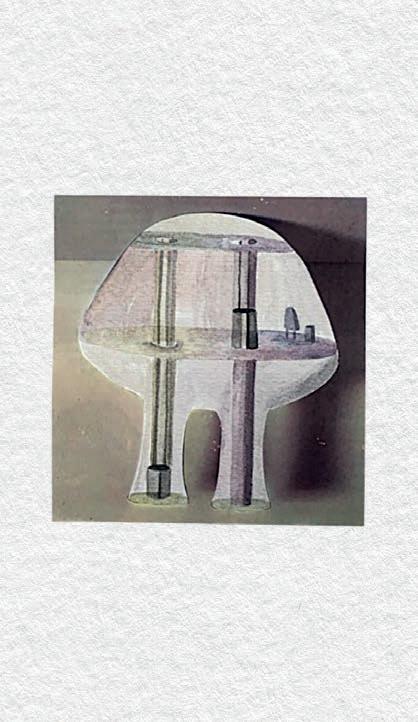

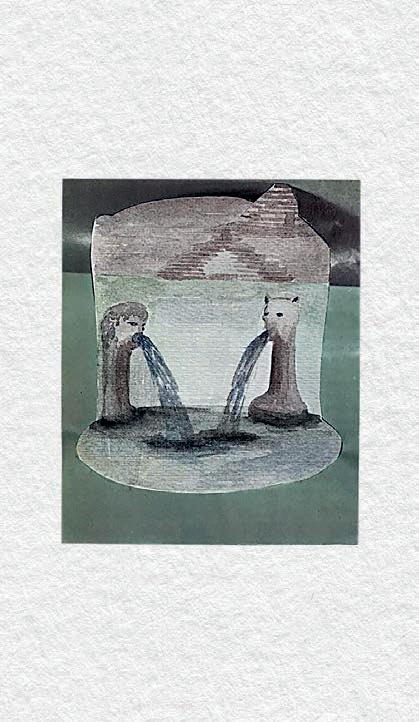

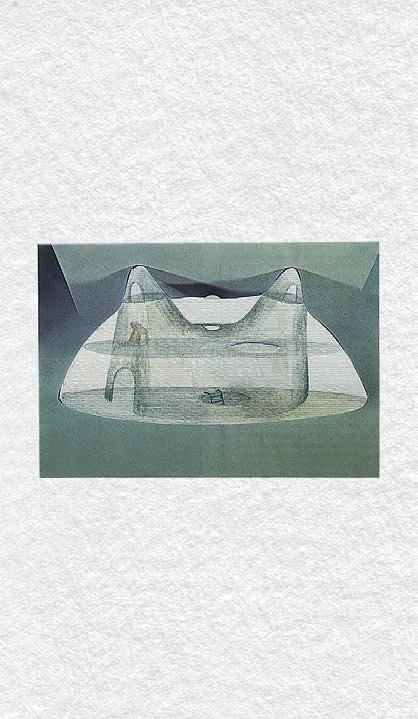

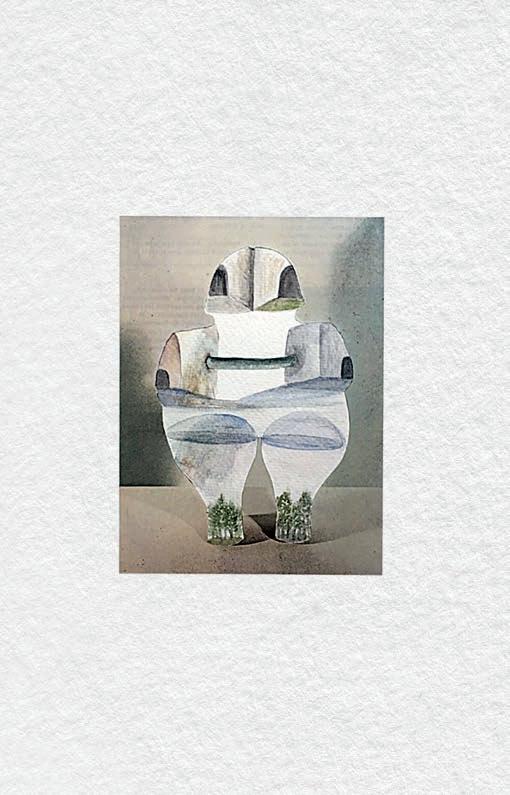

Otros trabajos se propusieron representar con imágenes lo que el cuerpo tiene de informe o inmaterial: su energía, su memoria, su vibración única, su naturaleza de organismo vivo, su capacidad vinculante. Las acuarelas de Carolina Fusilier parten de su interés por las figuras y los objetos arqueológicos para reimaginar –dentro de sus siluetas– paisajes y arquitecturas que funcionan como ventanas a otros mundos. Las piezas arqueológicas recuperan en su obra la cualidad de dispositivo: entidades capaces de disparar, desde su materialidad, usos e imaginarios impredecibles. Algo similar sucede con los pequeños ladrillos que pinta con obsesión María Guerrieri: un elemento simple que le permite dar rienda suelta a su imaginación. Con ellos construye una infinidad de formas libres, orgánicas, que humanizan el elemento fundamental de una casa, alivianan su peso y lo transforman en un módulo capaz de edificar hogares móviles, que cambian su forma con facilidad, que se adaptan a los contornos de la hoja como contexto, o que se sueltan del muro para flotar.

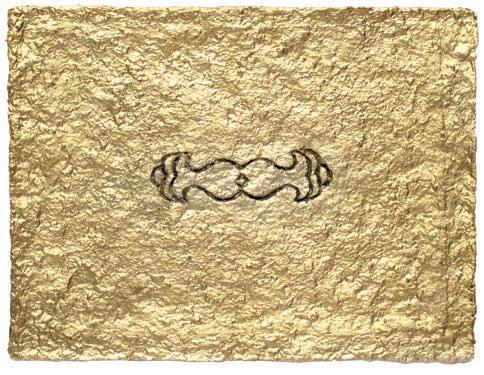

El deseo de dar lugar al devenir de los pensamientos y la emotividad atraviesa como un hilo conductor todos estos trabajos, complementado con cierto preciosismo formal, el cuidado en los detalles y el uso de materiales nobles, cálidos y, en muchos casos, brillantes, que dan a las obras una cualidad casi sagrada y dejan a la vista, una vez más, la necesidad de atesorar la experiencia personal. En el centro de las pinturas de Federico Roldán Vukonich, sólidas y tornasoladas, se ocultan símbolos en apariencia abstractos que evocan sus afectos: sus formas responden a la síntesis de un elemento o situación con que los identifica y parecen haber sido producidas en un material lo suficientemente duradero como para poder volver a ellos sin riesgos de que el tiempo o la memoria los desvanezca. El artista busca, como lo hace Palacios en sus tallas de emojis sobre roca, materiales estables que permitan que sus marcas y signos lo sobrevivan como cápsulas de tiempo.

La emisión de un mensaje que nos permita ser reconocidos y active nuevas vías de comunicación es también una característica fundamental del trabajo de Jimena Croceri. Sus Trapo sonajero son el resultado de extender

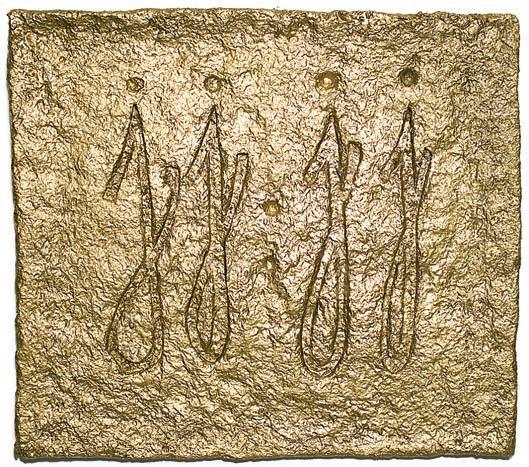

cascabeles diminutos sobre telas como las que se usan corrientemente para la limpieza. Dispuestos como notas musicales sobre líneas que recrean inmensos pentagramas, los cascabeles tiene la potencia de llamar la atención sobre una acción por lo general invisible (el trabajo doméstico), a la que Croceri adorna y otorga musicalidad. Ennoblecer los materiales para ofrecer a través de ellos la posibilidad de conexión con lo intangible es también un propósito fundamental en la obra de Denise Groesman. Su cabina de chapa dorada fue construida con latas de tomate vacías que recogió de los restaurantes de su barrio y limpió, martilló, zurció y adornó hasta lograr convertirlas en un “cohete/ árbol/ ducha sonora/ sonajero loco/ chaperío/ hornito/ sahumador”. Detrás de su superficie brillante, un interior perfumado por ramas de laurel invita a volar con la imaginación y vincularse con los sentidos.

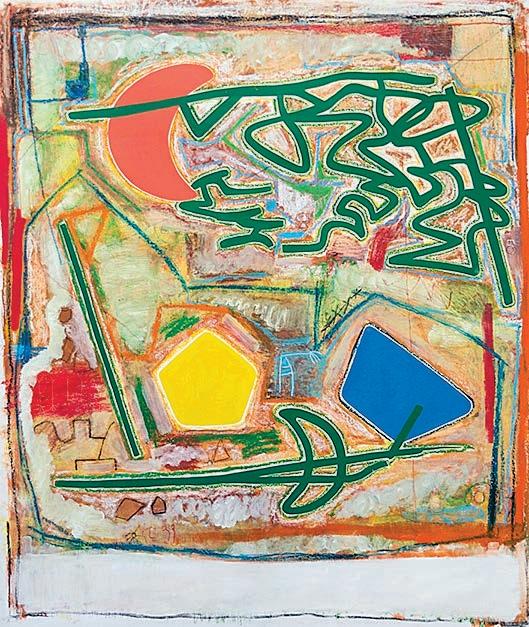

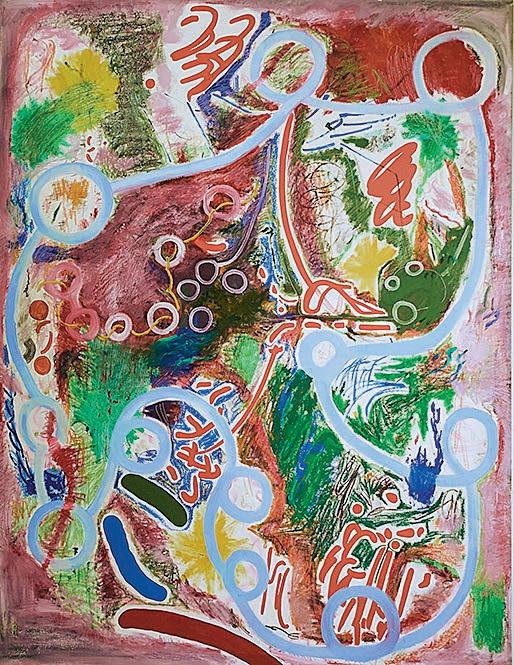

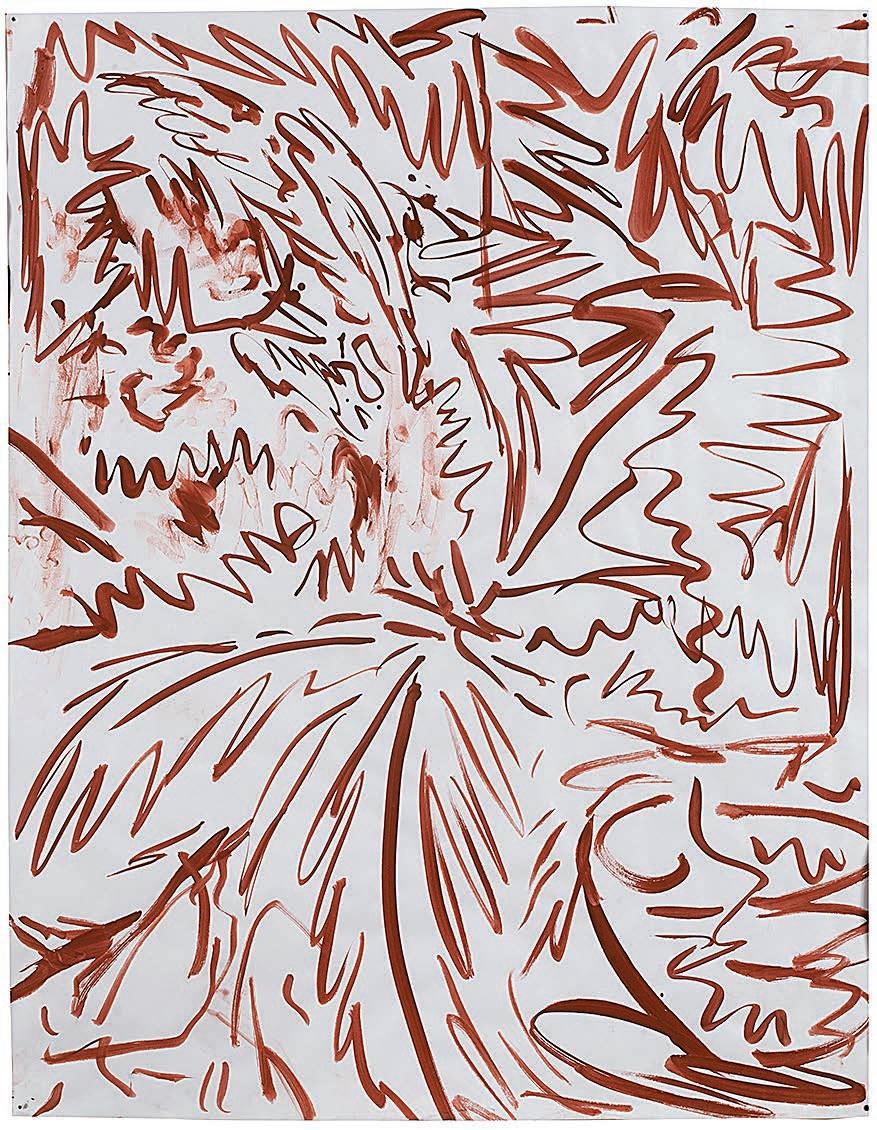

Un viaje interior similar promueve también la obra de Erik Arazi. La colección de dibujos geométricos en tamaño A4 que compone su instalación Sistema nervioso central busca representar la energía que él siente que se mueve por las partes de su cuerpo, únicamente quieto a la vista del otro. Sus dibujos, dispuestos para construir juntos las figuras esquemáticas de dos cuerpos vistos de frente, al estilo de un pictograma, se despliegan así como un gráfico de su interior. Las pinturas de Ana Won también comparten esta ejecución de tipo cartográfica. Si bien su lenguaje plástico es más gestual, abarrotado e intenso, sus formas y geometrías surgen de los trazos insistentes con que su cuerpo busca canalizar y dar imagen a su energía vital, entre otras dimensiones invisibles.

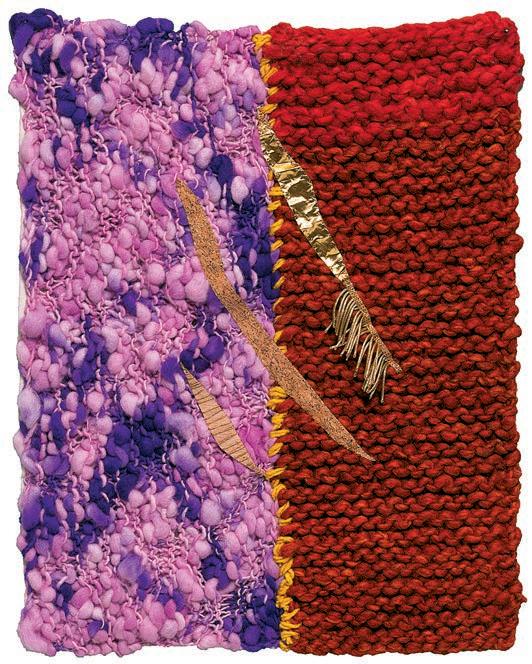

El universo individual multiplica sus formas de expresarse en la relación que establece con el territorio, las comunidades que viven en él y los saberes que ellas desarrollan y han heredado: patrimonios culturales y naturales con cualidades únicas utilizados por los artistas para generar medios de expresión personales y poéticos que dan cuenta de la medida en que ese entorno material y simbólico los ha configurado. Estos saberes –los modos de trabajar la tierra, como sucede en la obra de Florencia Sadir, por ejemplo, o de bordar, en la de Alejandra Mizrahi– son plenamente adoptados como vías para hallar nuevas formas, materialidades e imágenes. Y, si bien puede considerarse que sus prácticas rescatan tradiciones o

cosmovisiones que han sido relegadas por los sistemas industriales de producción y sus modos de vida, estas no son presentadas exclusivamente para alentar su estudio o activar una alerta respecto de la posibilidad de que desaparezcan, sino que, en las obras de estas artistas, están vivas.

Recurrir a esas tradiciones supone un retorno a modos de hacer que promueven la conexión directa con la tierra, sus ciclos y las comunidades que la habitan. Su incorporación como técnica acompaña las necesidades cotidianas de estos artistas, su desarrollo humano y el cuidado del ambiente. Como sugiere la artista salteña Soledad Dahbar al decir que entiende “la obra de arte como el efecto residual de una experiencia”,3 la práctica artística y la vida personal se vuelven cada vez más difíciles de disociar. Estas herramientas operan como parte de un ecosistema que liga entre sí las prácticas de aprender, construir, abastecerse, consumir, compartir y relacionarse, para acceder desde ahí a formas que den cauce a su capacidad expresiva y vinculen ese mundo funcional y doméstico con visiones más universales y abstractas. Por otro lado, la adopción de técnicas de elaboración artesanales, que dan como resultado piezas únicas cargadas de personalidad, recuerda el valor que tiene para la preservación del mundo propio rescatar la actividad diaria de la automatización y de la producción en serie.

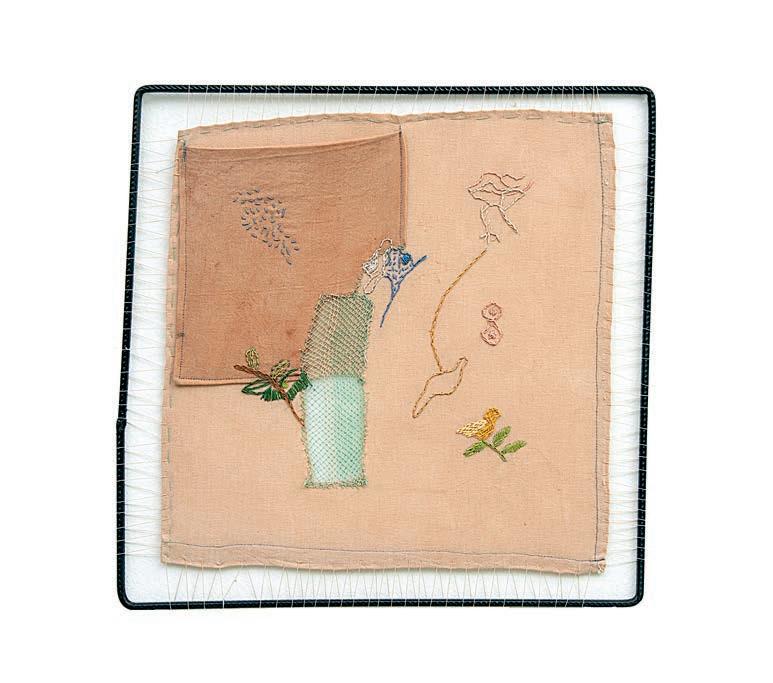

En el caso de Lucrecia Lionti, cuyo trabajo ya hemos mencionado, recurrir al tejido y la costura pone en valor procedimientos distintos de aquellos que promueve la academia del arte para hacer aparecer imágenes. Sus obras le permiten traer nueva sensibilidad a la práctica de la pintura, deshacer sus principios y dar sentido a un saber incorporado tempranamente en el ámbito familiar. Alejandra Mizrahi, en una senda similar, incorpora en su producción los aprendizajes adquiridos a partir de su contacto con las randeras y, alejándolos de su funcionalidad, los aprovecha para convertir su labor en un tipo de escritura que abre ventanas en sus telas. Esta práctica le permite experimentar el acto de creación que provee un espacio y un soporte, y dejar pequeñas marcas que son testimonio de sus días y de su localidad. Ella tiñe sus telas con las frutas y verduras que consume, producidas localmente. Por su parte, las tintas, los alimentos y los objetos que Florencia Sadir dispone sobre el plano de tierra que recrea el de su propio terreno en San Carlos, Salta, son registro del

3— Correspondencia con la artista, 19 de agosto de 2021.

trabajo en su propia huerta, de cuyos cultivos se nutre. Los objetos parecen disponerse como una ofrenda y como un gesto de agradecimiento a lo que la tierra da y también a quienes enseñan a labrarla (la gran olla de cerámica fue producida por su maestra).

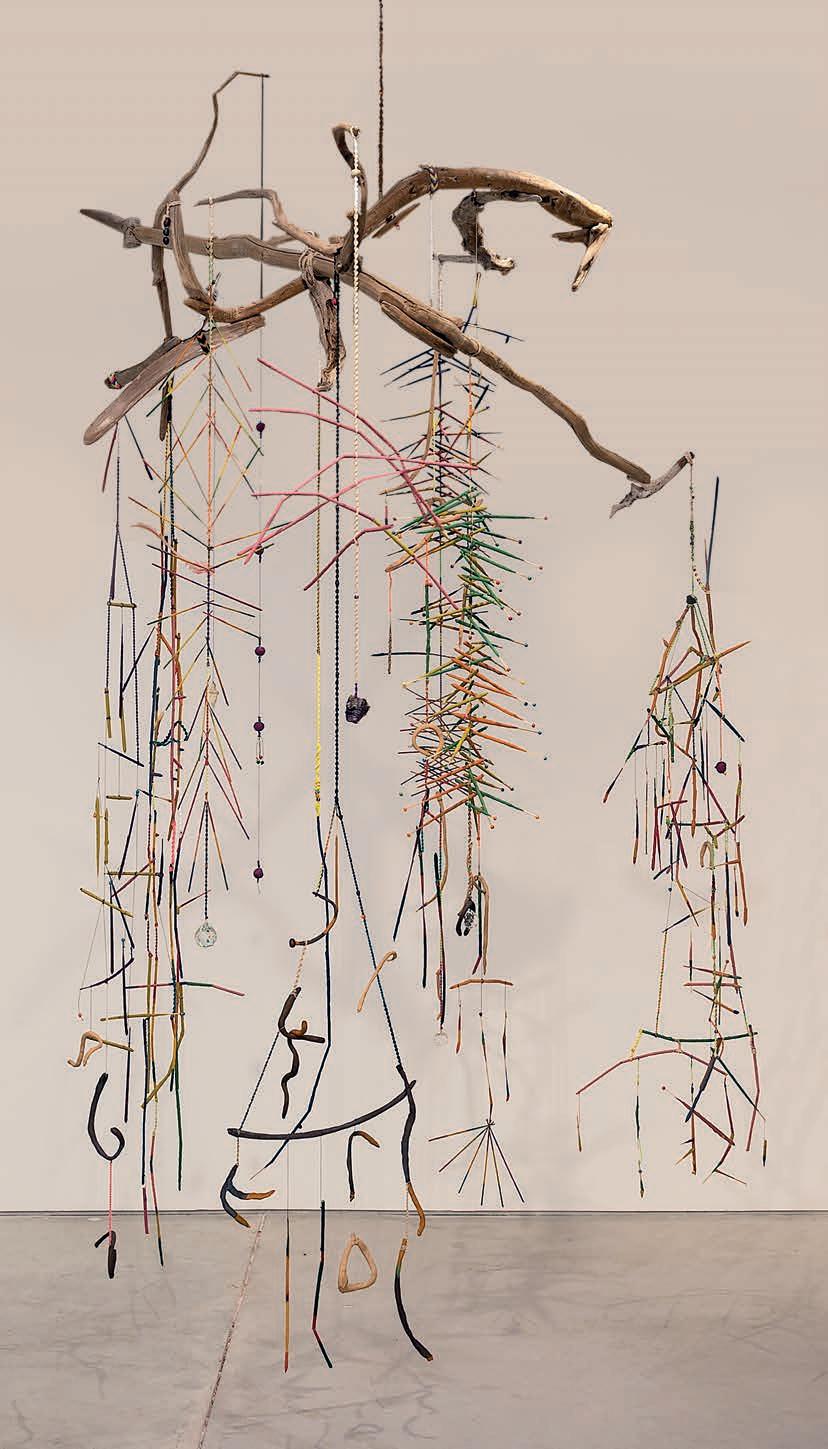

La gran escultura móvil de Antonio Villa, hecha fundamentalmente de sahumerios pero que combina otros saberes aprendidos en su comunidad de artesanos, tiene el potencial de limpiar y cuidar el espacio habitado e incorporar ese acto como rutina cotidiana a través de la quema. También trae a la sala del museo información sobre el paisaje en el que creció con el acto de recuperación de las ramas secas encontradas en paisajes de Esquel, lo que aporta un rasgo dramático asociado a un paisaje natural vasto y vigoroso, al que los sahumerios interrumpen con sus colores festivos, casi psicodélicos.

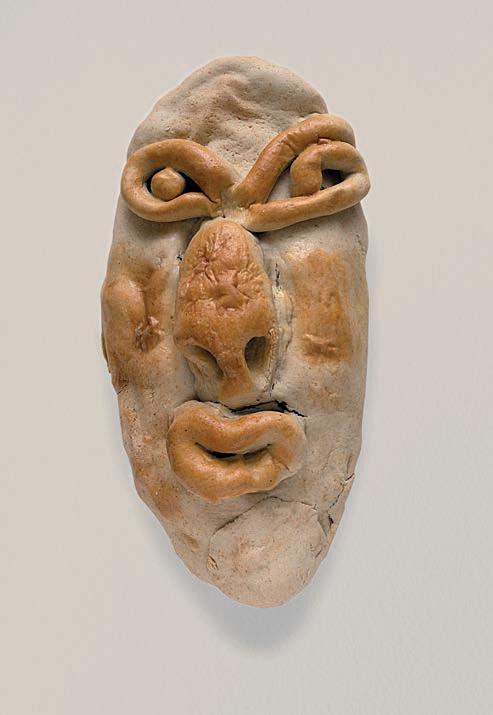

El mundo íntimo, doméstico y personal reaparece también con fuerza en el trabajo de La Chola Poblete, para quien el proceso de aprender a hacer pan –que implica descubrir cómo se transforma la materia para producir alimento– funciona como una vía de autoconocimiento, de renovación y de reconexión con la producción simbólica de los pueblos originarios, con la que, por su ascendencia, la artista se siente vinculada. En sus máscaras y accesorios de pan, dispuestos como piezas arqueológicas, Poblete desdobla una y otra vez su identidad, ensaya el tránsito entre géneros y crea signos con los que busca vincular el pasado y el presente.

El trabajo de Soledad Dahbar también constituye un señalamiento del territorio habitado o de procedencia. Sus pancartas de formas geométricas con los colores del cobre, la plata y el oro –que, superpuestas, dibujan un paisaje montañoso sobre el muro de la sala– buscan llamar la atención sobre aquello que constituye materialmente el territorio y que es objeto de prácticas productivas y mercantiles irresueltas. En su caso, un análisis de la situación del noroeste argentino, que oscila con gran desequilibrio entre la extracción y el abandono, la producción y el desabastecimiento. La síntesis geométrica que despliegan las pancartas –triángulos equiláteros, círculos y cuadrados– propone una mirada sobre lo esencial y sobre nuestra capacidad de reconocimiento de esas proporciones básicas, a las que alude como un verdadero cable a tierra.

El paisaje está presente de manera más explícita en las obras de Agustina Triquell y de Matías Tomás, que registran la experiencia de introducirse en él. El trabajo de Triquell se sumerge de modo directo en las implicancias que trae el proceso de habitar en su estado más primordial:

recorrer el espacio, identificarlo, alambrar, construir, trazar caminos, estar. Su combinatoria de imágenes, de textos, de elementos de la naturaleza y de fotografías estenopeicas que impulsan la reflexión sobre actos fundantes de aparición y transformación, surge como una trama sobre la problemática tejida a lo largo de la historia entre la necesidad tan elemental de habitar y la restricción del acceso a la tierra, un derecho atravesado por complejidades, obstáculos y una distribución desigual de poder. Las imágenes de Triquell proponen una reflexión sobre la experiencia de alojar y desalojar y, en ese arco, se evoca tanto la utopía del idealismo comunitario como la distopía que surge de los límites que imponen el capital y la ley.

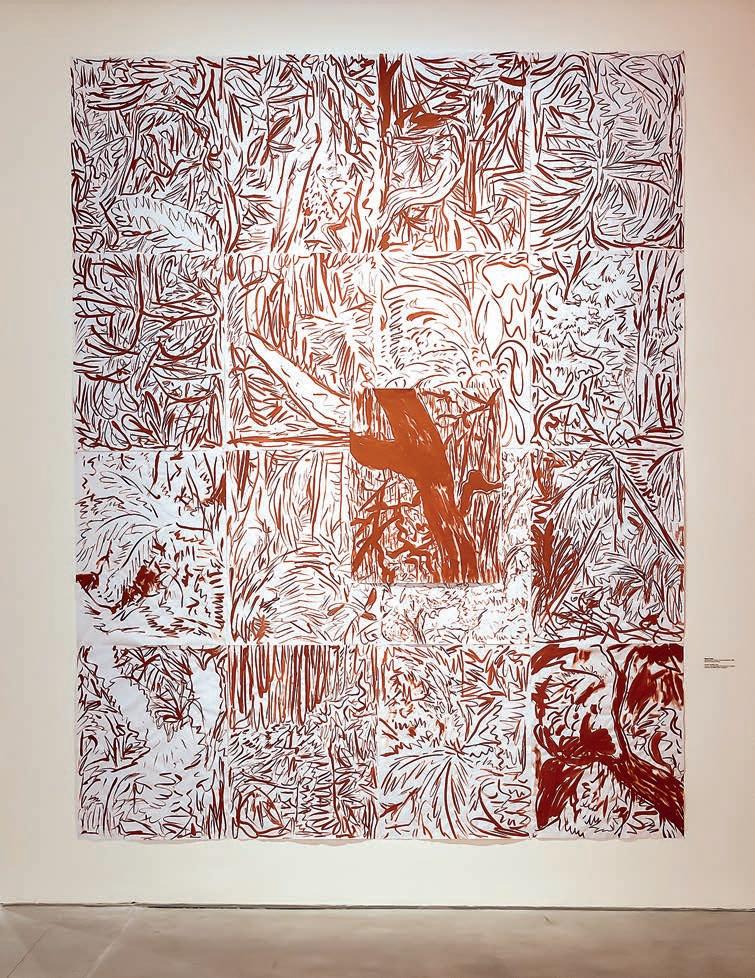

Por su parte, el mural de Matías Tomás deja registro de su paso por el paisaje: una selva en la que se sumerge por horas y que su dibujo, desaforado y gestual, logra representar como un espacio que lo envuelve, más que como un territorio que mira, como una trama que lo sensibiliza y a través de la cual se amplía y se ramifica su propia vitalidad. Su obra resulta, tal vez, una de las expresiones más claras de la comunión con el territorio a la que muchos artistas proponen entregarse. **

La necesidad de encontrar sentido en lo propio y cercano, de redescubrir con imaginación lo conocido, de recurrir a la producción gestual y artesanal para experimentar el acto creativo o de hacer participar lo tecnológico en las escalas y poéticas del universo personal son preocupaciones que atraviesan las prácticas de cada uno de los artistas que participan en Adentro no hay más que una morada. El hecho de que sean capaces de lograrlo y de que, a partir de sus procesos, construyan universos de sentido que nos sorprendan por su empatía y cercanía, o respondan a preguntas que incluso no habíamos llegado a articular abre una puerta amplia y generosa para imaginar cuántos caminos puede trazar una creación –o una manera de transcurrir y de habitar– atenta a las particularidades, a lo local e individual, pero que a la vez, justamente por mirar hacia adentro de manera profunda, logra reconocer algo compartido y universal. Un mundo de posibilidades para descubrirse y desarrollarse, cuyas medidas estén dictadas por el tiempo y el espacio del que somos

parte y que nuestra acción pueda transformar sin deformar. En esto reside gran parte de la fuerza de estos trabajos: en recordarnos que, aun frente a grandes desafíos, tenemos cerca una respuesta para romper con lo impuesto, la automatización y la inmovilidad.

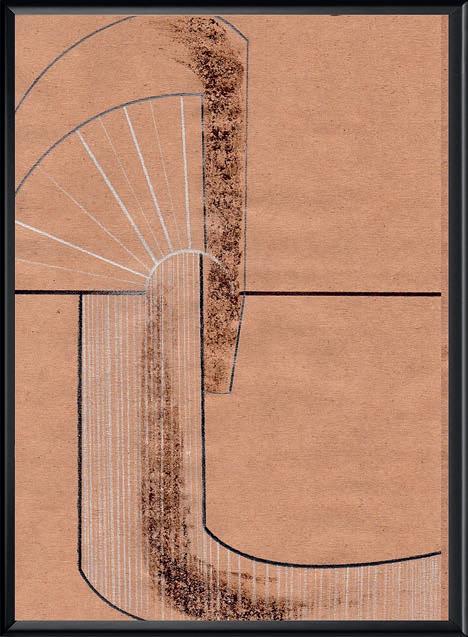

Fucsia, dorado y marrón [Fuchsia, Gold and Brown], 2021

Taglis por adición [Tagli by Addition], 2021

Otra vista de la obra [Another view of the artwork]

Chilkeadas las lenguas que vuelven del humo [Chilked the Tongues that Return from the Smoke], 2021

“pancóatl

Gilda, 2016

Budagaucho [Buddhagaucho], 2019

Pido un amor verdadero [I Ask For True Love], 2016

Baile del 16 de julio [16th of July Dance], 2019

Siempre conmigo [Always with Me], 2016

De la serie “Altares portables” [from the ‘Portable Altars’ series]

Baile del 16 de julio [16th of July Dance], 2019

Serie “Los mareados” [‘The Dizzy’ series], 2020-2021 p. 60: Fotografías de “Los mareados” con sus tutores temporarios durante 2020 [Photographs of “The Dizzy” with their temporary guardians during 2020]