TEMPLE MOBILITY MASTER PLAN 2022

Anti-Discrimination Notice

The City of Temple is committed to providing a safe and nondiscriminatory living and working environment for all members of the public and City employees. The City provides equal opportunity to all employees, applicants for employment, and the public regardless of race, color, sex, religion, national origin, age, disability, genetic information, veteran status, sexual orientation, or gender identity. The City will promptly investigate and resolve all complaints of discrimination, harassment (including sexual harassment), and related retaliation in accordance with applicable federal and state laws.

The City’s response to allegations of discrimination, harassment, and related retaliation will be 1) prompt and equitable; 2) intended to prevent the recurrence of any harassment; and 3) intended to remedy its discriminatory effects, as appropriate. A substantiated allegation of such conduct will result in disciplinary action, up to and including separation from the City. Vendors, contractors and third parties who commit discrimination, harassment or related retaliation may have their relationship with the City terminated and their privileges of doing business with the City withdrawn. Please contact the office of the City Manager at 254.298.5600 to file a complaint.

Acknowledgements

City Council Members

Tim Davis, Mayor

Jessica Walker, District 1

Judy Morales, District 2 (Mayor Pro Tem)

Susan Long, District 3

Wendell Williams, District 4

Steering Committee

Brynn Myers, City Manager

Jason Deckman, Senior Transportation Planner, Co-Project Manager

Richard Wilson, City Engineer, Co-Project Manager

Kenny Henderson, Transportation Director

Don Bond, Director of Public Works

Emily Parks, Manager of Public Relations

Kevin Beavers, Director of Parks & Recreation

Chuck Ramm, Asst. Director of Parks & Recreation

Traci Barnard, Director of Finance

Bryan Daniel, Board of Directors, Reinvestment Zone #1

Uryan Nelson, Director, Killeen-Temple MPO

Heather Bates, Director of Marketing & Communications

Kiara Nowlin, Communications & Public Relations Manager

Sean Parker, Director, Draughon-Miller Central Texas Regional Airport

Nancy Glover, Director of Housing and Community Development

Mike Hemker, Asst. Director of Parks & Recreation

Sherry Pogor, Financial Analyst

James McGill, Planning Manager, Killeen-Temple MPO

David Holmes, Operations Manager, Draughon-Miller Central Texas Regional Airport

David Olson, Asst. City Manager

Kendra Coufal, Planning Services Manager, CTCOG

The City of Temple would like to thank the following businesses for their help with spreading the word about MMP public meeting events and information:

Twice Apon A Clothes Line

The Hub

2nd Street Emporium

Pignetti's

The Casino

Sports World

Impressions By Criswell

First Furniture & TV

Texell

EZ Pawn

Vintage & Antiques

Trenos Pizza

First Street Roasters

Mexiko Cafe

Gandys Barber Shop

Relics Antiques

Empire Seed

Alchemy Salon

Ras Kitchen

Bird Creek Burger

Johnnie's Cleaning & Tailoring

Hawkins Personnel Group

KPA

Darling Decor

Security Finance

Hair & Lash Junkie

The City of Temple would like to give a special thanks to all of the staff at the Wilson Park Recreation Center for their help and extraordinary effort in making the January MMP Public Meeting such a great success.

RESOLUTION NO. 2022-0145-R

A RESOLUTION OF THE CITY COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF TEMPLE, TEXAS, AUTHORIZING APPROVING THE MOBILITY MASTER PLAN FOR THE CITY OF TEMPLE; AND PROVIDING AN OPEN MEETINGS CLAUSE.

Whereas, the City of Temple began work on the first Mobility Master Plan (MMP) in January 2021 and due to the wide-ranging nature of transportation planning, a team was assembled to provide specific expertise in a variety of subject areas;

Whereas, the project managers on the city side were selected from the Engineering and Planning Departments - the consultant team was made up of Alliance Transportation Group, Kasberg-Patrick Engineers, Garver USA, and Machi Mobility;

Whereas, the project managers and consultants leveraged their knowledge of public engagement, data analysis, traffic modeling, and engineering designs - a steering committee met quarterly to provide guidance on the plan vision as well as feedback on the technical documents;

Whereas, the Mobility Master Plan is both a data-driven and community-centered document. Work began with an assessment of the current state of transportation in the City of Temple - existing city plans were evaluated to incorporate transportation-related initiatives from those documents, and this was followed by several discussions with professional staff, key stakeholders, and city residents;

Whereas, the feedback received in these meetings informed a statement of the vision, goals, and objectives and an interactive online map allowed people to draw features and leave comments about specific locations and challenges - the project team held two well-attended public meetings – one virtual meeting conducted online in May 2021 and a hybrid meeting held at Wilson Park Community Center in January 2022;

Whereas, specific input on transit, congestion, active transportation, safety and freight was gathered during this phase of the plan - safety analysis and traffic simulations were conducted to provide a vision of how the transportation network may perform, as growth takes place and new projects are implemented;

Whereas, the Mobility Master Plan incorporates all modes of transportation in a strategic vision to meet the needs of the community in a multi-faceted document that addresses the challenges of balancing automobile traffic, pedestrian and bicycle trips, public transit, and commercial freight movement - a data-driven plan, the MMP is based on analysis of past accidents, current level of service and computer modeling of traffic flow and intersection function;

Whereas, the Mobility Master Plan lays out recommendations for needed mobility improvements and provides action steps to be used in implementing this plan - roadway, transit, and active transportation projects will be advanced and programmed based on an iterative feedback process between elected officials, city staff, community leaders, and citizen input;

Whereas, recommended actions include assembling a consolidate list of projects that are based on ongoing needs assessment, and making strategic budget decisions about which projects will be built, and in which fiscal year they will be funded;

Whereas, the Mobility Master Plan project team has made every effort to solicit public input and stakeholder feedback into this plan - in the interest of transparency and convenience, the draft chapters of the plan have been published online at www.templetx.gov/mobility;

Whereas, Staff recommends Council approve the Mobility Master Plan for the City of Temple;

Whereas, the fiscal year 2022 – 2028 Capital Improvement Program includes $30,000,000 in planned funding dedicated to prioritizing future project recommendations resulting from the Mobility Master Plan; and

Whereas, the City Council has considered the matter and deems it in the public interest to authorize this action.

NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED BY THE CITY COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF TEMPLE, TEXAS, THAT:

Part 1: Findings. All of the above premises are hereby found to be true and correct legislative and factual findings of the City Council of the City of Temple, Texas, and they are hereby approved and incorporated into the body of this Resolution as if copied in their entirety.

Part 2: The City Council approves the Mobility Master Plan for the City of Temple.

Part 3: It is hereby officially found and determined that the meeting at which this Resolution was passed was open to the public as required and that public notice of the time, place, and purpose of said meeting was given as required by the Open Meetings Act.

PASSED AND APPROVED this the 16th day of June, 2022.

THE CITY OF TEMPLE, TEXAS

TIMOTHY A. DAVIS, Mayor

ATTEST: APPROVED AS TO FORM:

Jana Lewellen

City Secretary

Kathryn H. Davis

City Attorney

Jana Lewellen

City Secretary

Kathryn H. Davis

City Attorney

List of Figures

List of Tables

This page intentionally left blank

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

1.1 What is a Mobility Master Plan?

As the City of Temple grows and develops, so will its transportation system. The best of both the country and the city meets in Temple; friendly small-town culture, a prime Central Texas location, and the amenities that accompany urbanized areas will bring in thousands of new residents by 2045. The increase in residents and jobs will require Temple to upgrade and expand the transportation system; the overarching goal is to ensure safe and efficient travel within the city and the surrounding region.

The City of Temple is planning for such growth. The project team, in collaboration with key stakeholders and local citizens, developed this Mobility Master Plan (MMP) with a state-ofthe-practice multimodal transportation system in mind. As a blueprint for all future modes of transportation, the plan includes recommendations for the development of roadways, transit systems, aviation, freight networks, and bike and pedestrian infrastructure over the next 25 years. This MMP document will serve as a guide for implementation of the multimodal transportation system, so the system is one that best serves the Temple community as growth continues.

“A strategic plan to improve the movement of people and goods in a community.”

A Mobility Master Plan is:

1.1.1 Elements of the Plan

An MMP is defined as “A strategic plan to improve the movement of people and goods in a community.” This MMP offers guidance on how to improve movement through Temple by increasing the overall efficiency and sustainability of the current system. To ensure the resulting transportation system is comprehensive and equitable, the recommendations in this plan include prioritized investments in infrastructure for all modes of transportation, including vehicular travel, transit, bicycling, and walking.

Examining the multimodal transportation system holistically provided a “big picture” view of the transportation system. Using this multifaceted approach to analyze the Temple study area, the city gained insight on what investments would best serve the community and how the elements of this MMP connect to other guiding plans in the Temple MMP area.

• Unifying – Similar to how it brings all the different modes together, the MMP also brings goals together, unifying all transportation plans. The MMP will work with other city plans, not against them –ensuring the hard work that has already been done isn’t overlooked or contradicted.

• Community – One of the key identifying factors of an MMP is that it is built on the community’s vision. The community voice was incorporated in all phases of the MMP, from the start to the finish.

• Strategic – Mobility master plans are strategic. They provide a vision for the future. Temple is growing fast and having a document that provides guidance for growing well can help ensure Temple is a desirable place to live for generations to come. An MMP can also help get funding for the projects Temple needs most, by identifying projects that can qualify for capital improvements funding.

• Progressive – the MMP is future-oriented and includes discussion of emerging technologies, such as autonomous and connected vehicles. By taking a proactive approach to planning as the technology is still developing, the City of Temple will be ready to implement technologies when they become more readily available to the public.

• Active Transportation Plan – the MMP will include an analysis of the existing active transportation (AT) networks— such as sidewalks, bike lanes, and other shared use paths— as well as a plan for how to best connect key destinations using AT infrastructure and resolve AT gaps along major corridors.

• Multimodal Transportation Plan – The MMP will include recommendations for all transportation modes, including walking, biking, driving, and taking transit. Any method of getting around Temple that can address the mobility needs of residents and visitors will be in the plan.

• Capital Improvement Plan and Implementation – Since the MMP projects will occur alongside other projects, all MMP recommendations will be appropriately prioritized to ensure a realistic implementation plan.

• Conceptual Transit Plan – The MMP will include high-level recommendations for the future of transit in Temple.

1.2 Planning Area

The Planning Area used for the MMP includes Temple’s City boundary and it’s Extra Territorial Jurisdiction (ETJ). However, regional connections are considered as part of the study to evaluate their impact on the transportation network.

1.3 Past Planning Initiatives

The project team conducted a thorough review of other planning documents and reports, drawing from the aspirational goals and development of a community vision for Temple in other plans together to ensure cohesion with the MMP. The summaries of each plan acted as a resource in the development of the MMP by providing guidance, background, and a variety of goals and objectives from previous plans. The insights gained from this review were the foundation for the goals of the MMP, and the plan review supported the city goal of an MMP that supports a unified community vision. The following plans and reports were included in the review:

• Safe Routes to School Master Plan – 2009

• Mobility Report – 2012

• Downtown Strategic Master Plan – 2014

• Airport Master Plan – 2017

• Quality of Life Master Plan – 2019

• Water and Wastewater Master Plans – 2019

• Ferguson Park Neighborhood Plan – 2019

• Population Analysis – 2019

• Comprehensive Plan – 2020

• Parking Action Plan – 2020

• Parks and Trails Master Plan – 2020

• Bellaire Neighborhood Plan – 2020

• Midtown Neighborhood – 2020

• 2021 Proposed Business Plan – 2020

• Mobility CIP (Section of 2021 Proposed Business Plan) – 2020

This page intentionally left blank

CHAPTER

2

VISION, GOALS & OBJECTIVES

2. VISION, GOALS, AND OBJECTIVES

The development of the Temple MMP started by identifying a Vision Statement, Goals, and Objectives that fit the community needs. These strategic elements will steer mobility planning efforts in Temple over the next 20 years. They were developed by utilizing existing priorities, national best practices, public feedback, stakeholder, and partner agency input. This process of defining a vision statement with corresponding goals, objectives and performance measures is essential to a data-driven and outcomes-based decision-making process for the MMP.

2.1 Vision Statement

The City of Temple worked with the Temple MMP Steering Committee—a team composed of community leaders and City staff—to develop a vision statement that would guide the project throughout the entire planning process. The vision needed to be broad enough to encapsulate all modes of transportation and the multifaceted nature of the project, but also specific enough to ensure the vision was focused on the Temple community.

2.2 Goals and Objectives

Goals and objectives add further detail to the definition and vision of the Temple MMP. The practical nature of the objective statements will facilitate bold and effective action. The project team developed nine goals and their corresponding objectives based on feedback from the public and collaboration with the Temple MMP Steering Committee. Each of the goals are described below. Further detail regarding performance measures and timeline for each objective can be found in Chapter 11: Implementation Plan.

GOALS:

Goals work as the guidelines for what the Temple MMP will achieve for the community and guide the rest of the planning process.

OBJECTIVES:

Objectives are specific, actionable targets that can be measured to achieve the Temple MMP goals.

“An inclusive and equitable multimodal transportation network that provides safe, well connected, mobility choices to the City of Temple.”

SAFETY FIRST - Achieve a significant reduction in traffic fatalities and serious injuries for all modes on all public roads.

• Vision Zero: Achieve zero traffic related fatalities.

• Achieve an overall reduction in serious injuries.

• Reduce crash rate on public roads.

• Reduce bike-ped fatal and serious injury crash rate.

CHOICES - Develop an integrated transportation network that provides improved mobility for all modes, including active transportation, transit, and space for emerging technologies.

• Reduce Single Occupancy Vehicle trips.

• Increase bike/ped facility usage.

• Increase transit ridership to pre-COVID levels.

• Provide mobility improvements so drivers/travelers can select their destination based on the quality of the destinations, not quality of their trip.

• Evaluate emerging technologies to consider modifications to the planning and design process to incorporate new modes, technology, and best practice.

CONNECTIONS - Develop a connected multimodal network providing accessible mobility options to serve the city across multiple modes that are integrated with the surrounding land use. Provide accessible mobility options through a connected multi-modal network that is integrated into the surrounding land use pattern.

• Increase mode choices to residence or place of employment.

• Increase accessibility to transit.

• Close gaps in the sidewalk/bicycle network.

• Expand sidewalk/bicycle facility network.

PROSPERITY - Strengthen the economic prosperity of the city by improving transportation systems that promote access to jobs for all residents regardless of their income level, age, or mobility status; reliability of the workforce for employers; and mobility hubs and shipping logistics by providing efficient and reliable movement of goods by both rail and truck.

• Improve low income and minority transit.

• Incorporate elements of the Comprehensive Plan to identify strategies to reduce housing and transportation costs (Social Vulnerability Index).

• Enhance freight reliability to promote dependable commerce/just in time delivery/mobile warehousing.

• Establish communication avenues with members of community and outreach organizations to manage and mitigate impacts.

COMMUNITY DRIVEN - Partner with all community members and elevate the underrepresented voices to provide communitybased transportation solutions.

• Increase number of contacts through the stakeholder engagement and public meeting process.

• Increase number of groups addressed through speaking engagements requested / carried out.

• Empower champions for the MMP to support strategic initiatives and action steps that lead to implementation.

• Involve P&Z and other boards/councils for input, priorities, needs vs wants.

MOBILITY – Provide a Multimodal Transportation System that safely takes people where they need/want to go, in a timely manner, with a perceived sense of comfort.

• Reduce congestion related delay.

• Implement Transportation Systems Management and Operations (TSMO) improvements/efficiencies to improve major corridor level of service (LOS).

• Improve average intersection level of service.

• Improve frequency and coverage of transit service.

• Achieve a reliable primary system.

MAINTAIN AND SUSTAIN - Promote stewardship of a sustainable transportation system through strategic asset management and systems preservation.

• Improve roadway Pavement Condition Index (PCI).

• Improve bridges within the City’s jurisdiction.

• Increase resiliency.

• Increase redundancy.

QUALITY OF PLACE - Promote place making through development of context sensitive complete streets design elements.

• Design a context sensitive system that promotes neighborhood integrity and property values.

• Design a context sensitive system that protects cultural resources and historical sites.

• Protect the natural environment (air quality; water quality; wetlands and flood plain).

• Implement design elements and functionality that promote a sense of community and provide amenities such as shelters, trees, and/or shading.

FUND AND IMPLEMENT - Identify shortand long-term action steps while pursuing revenue resources to build, maintain, and operate new and existing transportation infrastructure and services.

• Develop an ongoing project selection and prioritization process that increases City competitiveness across all modes in planning-partner infrastructure funding programs.

• Develop and fund program to regularly monitor roadway.

• Maintain and update transportation related data sources, and fund design resources in order to improve the city’s capability to capture available grant funding.

• Provide development plans that support strategic initiatives that improve funding for transit and active transportation.

• Strengthen public/private partnership funding opportunities to ensure infrastructure investment is sufficient to support growth and new development.

CHAPTER 3

PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT

3. OVERVIEW OF THE PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT PROCESS

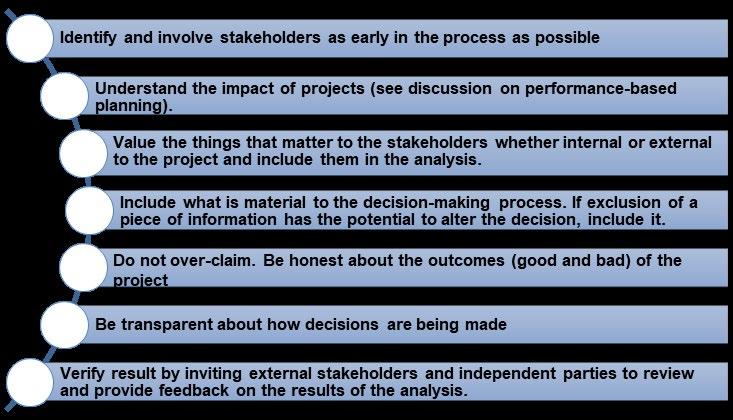

Community input is crucial to developing a plan that accurately identifies and addresses the public’s needs and desires. The City of Temple involved the public early in the planning process by providing continuous, transparent, and effective access to information about the study and the decision-making process used to determine final recommendations. By involving the public throughout the life of the study, the City employed an open decision-making process that encouraged the development of a plan supported by the public. Ultimately, feedback from the community helped define existing mobility issues in Temple, establish goals that defined success in addressing those issues, develop initial solutions proposed by the project team, and inform the final set of proposed solutions.

The City was mindful of the need to include residents that have historically been underrepresented in the planning process. Special attention was made to reach out to community members and stakeholders from these demographics to gather input for the Plan. Given the circumstances revolving around the Covid-19 pandemic and impacts to typical meeting structures, the City was able to use a mix of in-person and virtual tools to conduct meetings and gather feedback.

The public involvement period lasted throughout the life of the project from March 2021 to May 2022. During this time, various meetings were held with the public, stakeholders, and a project Steering Committee.

Round 1

Workshops and Public Information

Social Media updates, Distribution of Flyers, Utility Bill inserts and Newspaper Ads, Public Meeting #1

Social Media updates, Distribution of Flyers, Utility Bill inserts and Newspaper Ads Public Meeting #2

Social Media updates, Distribution of Flyers, Utility Bill inserts and Newspaper Ads Public Meeting #2

3.1 Meetings

Conversations with Temple community members provided crucial context for the data analysis conducted, as well as a better understanding of the community needs and wants for their future transportation system. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, meetings occurred both virtually and in-person, depending on the safety protocols required by local officials at the time of the meeting. At times, the project team used a “hybrid” approach, meaning the meeting occurred in-person with an option to join the meeting virtually if desired. If held virtually, meetings were conducted on a variety of digital platforms, including Microsoft Teams, Zoom, and Facebook Live. Online public meetings were publicized via the Temple MMP webpage and links were posted in outreach materials.

Three types of meetings were held at various points throughout the project: 1) Steering Committee, 2) Stakeholder and 3) Public meetings.

3.1.1 Steering Committee Meetings

The Steering Committee was composed of about a dozen technical advisors who helped design the internal planning process. Members included multiple staff members from the City of Temple as well as other decision-makers from the community, such as representatives from the Killeen-Temple Metropolitan Planning Organization (KTMPO) and the Reinvestment Zone (RZ). The committee provided guidance on planning process, public engagement, the analysis process, and components of the final MMP.

3.1.2 Stakeholder Meetings

Stakeholders were identified in collaboration with the project Steering Committee. The project team developed a list of stakeholders and their key issues, concerns, and interests. Stakeholders were engaged at multiple points in the planning process to offer their unique insight on the history and dayto-day aspects of life in Temple. Meetings were held with an initial stakeholder group that represented various sectors of the community, including neighborhood associations, community organizations, school districts, active transportation users, public transportation users, parks and recreation users, public safety and emergency response, resource and regulatory agencies, aviation, freight and manufacturing, and economic development. Additional meetings were held with: Temple Area Builder’s Association (TABA), Hill Country Transit (The HOP), East Temple Neighborhood Initiative (ETNI), Zoe’s Wings, the Meredith-Dunbar Early Childhood Academy, and the Chamber of Commerce.

3.1.3 Public Meetings

The team engaged with residents throughout the Temple area, gleaning broader insight about the public’s goals and priorities for transportation in Temple. Two public meetings occurred to provide opportunities for citizens to learn about the Plan and give input on their needs and concerns to be addressed in the proposed MMP. A public hearing was held to present the draft findings and recommendations to the Temple City Council and to provide an opportunity for public feedback on the plan. The first meeting was entirely virtual, and the subsequent meetings were hybrid (virtual and in-person).

Public Meeting 1 was held in May 2021. This meeting presented an overview of the study and solicited public input on what was important to the community, challenges and issues, and general concerns. There were 90 attendees via the virtual Zoom meeting or Facebook Live.

Public Meeting 2 was held in January 2022. This meeting presented the results of the existing systems analysis and solicited public input on potential recommendations. 62 people attended this meeting in person, and an additional 79 people attended virtually using either the Zoom meeting link or Facebook Live.

Public Hearing will be held in May 2022 and will present the draft MMP to the City Council and solicit public input, including potential final modifications.

Detail of the feedback received at each of these meetings can be found in Appendix A: Public Involvement Technical Memorandum.

3.2 Tools

3.2.1 Virtual / Online Public Involvement

In light of the COVID-19 pandemic and the growing culture of remote work, utilizing a project webpage as well as publicizing visualized data through social media was an effective way to engage with the community from a safe distance. The following digital methods supplemented the meetings with Steering Committee members, stakeholders, and the public.

MMP Webpage – A project webpage was published on the City of Temple website. Material on the webpage provided public access to project details, links to meetings, and contact information. The site also included all materials from meetings, such as display boards and maps. All graphics that were distributed digitally depicted data in a way that told a story, making more intricate details of the plan and outcomes from analyses easier to understand. As draft chapters of the Mobility Master Plan were developed, they were added to this webpage for public viewing, before the final Plan was adopted.

Interactive Mapping Tool – As part of the online webpage, users were able to view a map of Temple and place comments on specific locations. The tool allowed users to draw lines, shapes, or points on the map and then add detail about specific concerns or improvements they would like to see in the area.

Social Media Outreach – The City of Temple employed the City’s Facebook, Instagram, Nextdoor, and Twitter accounts to present project information and to announce public meetings.

Survey Tools – The online survey platform, Microsoft Teams Forms, was employed as an interactive tool to engage the public and stakeholders. This tool was used during meetings as well as during project milestones to solicit feedback.

Video Production – The project team created a brief, engaging video to promote the second public meeting and the project as a whole. The video included commentary from the City Manager, Brynn Myers, and Assistant City Manager, David Olson, P.E.

3.2.2 Physical Materials

While much of the communication between the project team and community members occurred digitally, traditional methods of communication supplemented the virtual outreach methods and provided access to those who would not have been informed of the plan otherwise. Physical materials used to promote the MMP and solicit community feedback included meeting handouts (Spanish and English), project flyers, utility bill inserts, newspaper display ads, printable surveys, traditional media (press releases, public service announcements, etc.), and physical display boards and maps at in-person meetings.

3.3 What We Heard

3.3.1 Interactive Map Results

The interactive map was available for comment from May 2021 to February 11, 2022, and over 400 comments were received. The graphics below show the types of comments received and their percentages.

3.3.2 Public Meeting Results

Over 60 comments were received from Public Meeting 1 either through discussion during the meeting or through comment forms received through May 31, 2021. Most of the comments were related to the following topics:

• Improving availability of transit,

• Expanding bike trails and sidewalk network,

• Connecting areas of the City, such as east Temple to the Industrial Park,

• Considering micro mobility options, such as bike rentals and point-to-point transportation,

• Improving intersections to reduce delay and improve safety,

• Controlling speed on certain roadways, and

• Funding of improvements.

Figure 3.3:

- Items the Public Wants to See Added or Improved

31% - Roadway and Intersection Improvements

30% - Transit

28% - Hike and Bike Trails

5% - Sidewalks

2% - Bike Lanes

2% - More Free Parking Downtown

1% - Lighting Improvements

1% - Senior Transportation

0% - Ride Share

3.3.3 What Does the Public Input Tell Us?

• Improving safety for road users including bike and pedestrians is a high priority

• Improving connectivity and access to economic and public health facilities is supported

• Traffic and intersection improvements have a high level of support

• Transit improvements are supported especially for those with mobility challenges

40% - Road Safety

13% - Connectivity

12% - Public Transportation Accessibility

11% - Public Health and Environment

10% - Traffic Congestion

9% - Pedestrian/Bicyclist Safety and Mobility

1% - Road Maintenance

3.3.4 How Was the Public Input Used in the Decision-Making Process?

Feedback gathered at each of these critical points was used to inform the planning and analysis process. This feedback was used to focus the analysis process, modify planning scenarios, adjust and prioritize goals and objectives, and ultimately shape recommendations.

This page intentionally left blank

CHAPTER 4

SUMMARY OF EXISTING CONDITIONS

4. SUMMARY OF EXISTING CONDITIONS

The review of existing conditions for the Temple MMP ensures that the investments recommended by the plan are based on a quantitative evaluation of the needs specific to the City of Temple. As described in Chapter 3, public and stakeholder input helped draft a vision statement for the City supported by broad goals, each with specific objectives. These objectives are a framework to identify areas of transportation needs within the City. Additionally, the data analyzed in this chapter is supplemented by what was learned through the public engagement process to also capture what the data may not be providing, such as near misses.

An important step in identifying transportation needs in the Temple MMP study area is to capture, as much as possible, an understanding of the existing population and employment trends occurring in the area. Land use patterns and demographic trends directly influence which modes of travel people use. People use the system to travel to and from work, access services, leisure activities, and for many other reasons. In areas where development is spread out and land uses are separated, people are more likely to use personal automobiles and travel further distances throughout the day.

Over the past decade, Temple has seen significant growth, both within the City and in the rural areas contained in the ExtraTerritorial Jurisdiction (ETJ). According to the Decennial Census, the City of Temple grew from 66,102 people in 2010 to 82,073 in 2020. In the past five years, the population increased by nearly 10%. When the ETJ is included, the population is estimated at roughly 134,000 people. (2019 American Community Survey). Employment is strong within the study area, with nearly 60,000 jobs in 2018.

Analysis of the existing conditions provides a baseline for the transportation system performance assessment. The following sections summarize the mobility analysis completed in the Comprehensive System Assessment (CSA), which examined the existing transportation network for the study area. By examining each mode of transportation and its impact on the network, City leaders can understand which investments will help the greatest number of people. Additional details on the elements included in this chapter can be found in Appendix B: Comprehensive System Assessment Technical Memorandum.

4.1 Roadway Network Configuration and Condition

When looking at the entire transportation system, analyzing the need for new roadways and additional capacity is important to understand the functionality and existing conditions of the network. Roadway networks are examined within the context of different mode choices and factors that impact safety and efficiency (e.g., quality and availability of transit services and active transportation infrastructure, the resiliency of the transportation system in the case of a natural disaster or security threat). The transportation network may be generally categorized as a grid of major corridors, with recent development resulting in more varied roadway patterns.

Temple is situated along Interstate 35, the single most important north-south corridor in Texas, linking the city with major metropolitan areas, tourism, and international trade. The interstate and expressways in the City continue to be improved to add capacity and accommodate freight movement, local traffic, and longer trips. H. K. Dodgen Loop provides a bypass loop around the City and connects to several major corridors, such as US 190, SH 36 (Airport Road), SH 317, Adams/Central Ave, 31st Street, 3rd Street, 1st Street, and Avenue H. Typically, travelers in the City will encounter the most traffic on these facilities, especially during the peak travel periods. Preliminary analysis and public feedback highlighted areas of known traffic concerns in the City of Temple:

• Intersection of Avenue H and 31st Street

• West Temple commuters - congestion along FM 2305 and connecting corridors

• Underdeveloped roads (e.g., North Pea Ridge, South Pea Ridge, Hartrick Bluff)

• Congestion along 31st Street

• Downtown Temple one-way streets

• Potentially underutilized roadway capacity (e.g., Industrial Blvd Cut-Off, Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd)

4.1.1 Current Thoroughfare Plan

A Thoroughfare Plan is a long-range plan/map that identifies the location and type of roadway facilities needed to meet projected long-term growth. It is not a list of construction projects but rather serves as a tool to enable the City to preserve necessary rightof-way for the development of the transportation system as the needs arise. The primary consideration in planning and designing streets has historically been the roadway’s vehicle capacity, represented by roadway width and number of traffic lanes. Multiple documents guide how streets in Temple are currently classified, including the City of Temple Master Thoroughfare Plan (approved with the 2020 Comprehensive Plan on October 15th, 2020), and the KTMPO Metropolitan Transportation Plan (MTP), which categorizes roads into classifications and plans for future expansions for the region. Temple currently uses six road classifications:

• Highway – Mobility Between Cities

• Major Arterial – Mobility Within City

• Minor Arterial – Moderate Length Trips

• Community Collector – Connect to Arterials

• Neighborhood Collector – Connect to Arterials and Collectors, Property Access

• Local Roads – Connects to Collectors, Property Access

4.1.2 Traffic Delay and Level of Service (LOS)

Two modeling systems analyzed the existing traffic levels of service (LOS) in the study area, 1) a travel demand model from KTMPO, and 2) TransModeler, a mesoscopic traffic modeling tool. The models used data inputs including roadway characteristics, speed limits, roadway capacity, traffic volume counts, signal timing, and origin and destination data. The data was sourced from KTMPO, the City of Temple, and the TxDOT Statewide Traffic Analysis and Reporting System (STARS) to evaluate the existing interaction between supply and demand on the transportation system.

Level of Service Analysis

One of the pertinent outputs of both models is the Level of Service (LOS). LOS is an indicator of congestion on a scale from A to F, where A represents free flow traffic and F represents severe congestion. LOS is derived from comparing traffic volume to the traffic capacity on a given corridor or segment, also known as “volume-to-capacity” (V/C) ratios.

Table 4.1 provides the ranges used to generate roadway segment LOS values and are based on TxDOT’s Transportation Planning and Programming (TPP) division resources:

Less than 0.33

0.33 to 0.55

0.55 to 0.75 D 0.75 to 0.90

E 0.90 to 1.00

F Greater than 1.00

Roadway segments in the study area were analyzed using the KTMPO Travel Demand Model. As displayed in Table 4.2, LOS measures show that out of 511 roadway miles, 464 roadway miles (91%) are categorized as having an adequate LOS (LOS A-D), and 47 roadway miles (9%) are categorized as having a deficient LOS (LOS E-F).

*2015 was used to evaluate current conditions because it is the most recent year available in the KTMPO Model.

Level of Service (LOS) is an indicator of congestion on a scale from A to F, where A represents free flow traffic and F represents severe congestion.

Figure 4.1 shows that the existing LOS was strained along highways around major urban areas. Contiguous LOS scores of E and F, suggesting heavy congestion, are seen on the following roadways of the study area:

• Highway 36 west of the City of Temple

• Highway 317

• I-35 from north of the City of Temple to the City of Belton

• Highway 363 west of the City of Temple

• US 190 south of the City of Temple

• Highway 95 south of the City of Temple

Figure 4.1: Temple Subarea Level-of-Service - 2015 Existing Conditions

Existing Operational Performance Results

Measures of effectiveness (MOEs) were output from the TransModeler simulation runs to evaluate operational performance of the AM and PM peak hours in the baseline conditions. These MOEs include intersection level of service (LOS), total network delay, total vehicle-miles traveled (VMT), segment delay, and segment volume.

81 intersections in the study area were analyzed using TransModeler. Approximately 15 percent received a deficient LOS (LOS E-F) during peak commute times (Table 4.3).

Delay is a measure of additional travel time experienced by travelers at speeds less than the free flow speed.

Total network delay sums the delay for all vehicles within the simulation and all vehicles which could not enter the network during the analysis period.

Source:

V6

Total Network Delay – Baseline Conditions

Using TransModeler, total network delay was compared for the AM and PM peak hours. The comparison showed PM peak hour experiences higher total network delay than the AM peak hour. This is consistent with the typical traffic patterns in most urban areas, as trips between home and work—as well as trips between home, work, and commercial developments—tend to occur more in the PM peak hour.

31st street experienced the highest average delay in the PM peak hour, followed closely by the couplet formed by Adams and Central Aves.

Table 4.4 highlights the top 5 intersections in the AM period with high/failing LOS based on delay. Table 4.5 highlights the top 5 intersections in the PM period with high/failing LOS based on delay.

4.1.3 Key Findings

The following summarizes key findings from the roadway needs analysis:

• As expected, major roadways such as interstates and state highways are expected to see high levels of congestion and delay in the future.

• Intersections along 31st Street, Adams Ave, and Central Ave experience high levels of delay.

• Many connections on the west side of town, near Loop 363 are forecasted as failing in 2045.

• Educational facilities within the City of Temple are expected to continue to be one of the largest activity generators in the community. Level of service around these institutions is typically congested, especially during peak hours.

• Industrial traffic will likely continue to expand in Temple, especially to the north. Evaluating impacts of current delay and the freight network on future LOS will help identify potential routing recommendations.

4.2 Multimodal Transportation System Performance Statistics

Each mode of transportation analyzed (including transit, active transportation, freight, and aviation) informed the mobility, accessibility, connectivity, and other performance factors of the comprehensive multimodal transportation system in Temple.

4.2.1 Transit

Because transit in the study area is part of an interconnected regional system, both the breadth of transit service from the regional system level as well as the individual transit stop characteristics and performance were evaluated. This included an evaluation of the ridership of each transit route of the existing fixed route bus transit system in the study area by stop and by how much of the underlying transit market it served.

System Overview

Operating under the Hill Country Transit District, “The HOP” provides all fixed route services in the study area. The HOP is a regional public transit system that started in the 1960s as a volunteer transit service and evolved to serve a nine-county area. Serving multiple cities through the largely rural service area, the HOP is a coverage-based, hub-and-spoke system.

Currently, there are two transfer stations in Killeen and Temple that serve as the major ‘hubs’ and are connected in a linear pattern by two main routes. The HOP runs nine different fixed bus routes in the communities of Temple, Belton, Harker Heights, Killeen, and Copperas Cove. Two routes serve the City of Temple.

• Route 510 – VA Hospital/Temple College/Temple Mall/ Walmart

• Route 530 – Adams Ave/Temple HS/Social Security Office

A hub and spoke model of transit refers to the design of a route network. Typically, this type of network design centers around one or two central transit locations, from which all other routes disperse as “spokes” from the hub.

Figure 4.4: The HOP Existing Fixed Routes

The HOP Existing Routes

Figure 4.5: HOP Service Categories

Operations

All of the HOP routes, apart from the 200 Express route, operate with 60-minute headways. The 200 Express operates service with trips every two hours. While service span varies by route, most routes run from approximately 6:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. Within Temple, Route 200 Express Route Connector operates as an Express Service, and Routes, 510 South and 530 East/ West Crosstown are Hybrid Routes (both loop and bi-directional service).

BOARDINGS

ALIGHTINGS

TOTAL

Ridership Analysis

COVID-19 Impacts on Transit Ridership

Transit ridership across the nation took a large hit during the initial onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Ridership declined drastically across the country. For example, Houston Metro reported its total ridership was 53.6% lower in December 2020 than compared to the same month 2019.1 Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) saw a 55% decrease2 in overall ridership from March to June in 2020 alone. The HOP faced similar hardship, with ridership declining by similar percentages. Although transit is expected to recover, the length of time it will take to reach pre-COVID ridership numbers is unknown.

Ridership Analysis Results

Using ridership counts from The HOP that reflected ridership activity across the fixed route transit system spanning one week in spring of 2019, the project team mapped the existing transit ridership by bus stop. The total ridership activity (the sum of boardings and alightings) for each stop revealed which stops along each route had the highest and lowest ridership activity. The majority of stops that experienced high ridership activity were transfer stations and other major destinations such as medical facilities, supermarkets, and higher education facilities. Specifically, stops with the highest ridership activity included:

• The Baylor Scott & White Clinic on Scott & White Drive between Harker Heights and Belton

• Avenue U at 3rd Street by the VA hospital

• Confederate/Liberty Park in Belton

• The Baylor Scott & White Medical Center

• Temple Transfer Station

• Walmart on Private Drive

1 Source: TTI, April 2021, https://comptroller.texas.gov/economy/fiscal-notes/2021/ apr/transit.php

2 Source: Community Impact, July 2020, https://communityimpact.com/dallasfort-worth/richardson/coronavirus/2020/07/08/dart-officials-report-55-hit-toridership-since-march/

the number of people getting on a bus

the number of people getting off a bus

RIDERSHIP ACTIVITY

the sum of all boardings and alightings at a given location

Transit Market Analysis

The project team identified how much of the potential transit market in the Temple area is currently served by fixed route transit. The transit market analysis included a number of factors such as total population, total employment, and Targeted Transit Riders (TTR) currently within the service area. TTR are a portion of the population with demographic3 indicators that would suggest a greater likelihood of their using transit, including:

• Population with disabilities

• Population with limited English proficiency

• Population of minorities

• Population aged 65 and older

• Population aged 17 or younger

• Population in poverty

Target Transit Riders (TTR)

With the TTR population per US Census block group in the study area established, existing bus stops and demographic/employment data were used to conduct a buffer analysis with Geographic Information Systems (GIS) mapping software. The analysis identified populations that fell within or outside of a quarter-mile buffer, which is the distance assumed most people will walk to access transit.

To estimate the number of TTR served by the existing fixed route transit system, the percentage of each block group that fell within the buffer was calculated. This same process was used to calculate the total population served and total employment served.

are a portion of the population with demographic indicators that would suggest a greater likelihood of their using transit.3 Demographic data for each block group in the study area was sourced from the US Census Bureau’s 2019 American Community Survey (ACS) and 2018 Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics program (LEHD).

Figure 4.6 compares the levels of TTR in each block group to the quarter-mile buffer generated around the existing transit stops. The map illustrates that there are block groups with high levels of TTR around Temple and westcentral Bell County south and east of Killeen/Harker Heights that fall outside of the existing system’s service area.

Source: The HOP

TARGETED TRANSIT RIDERS

Figure 4.7: Population and Employment Served by Transit

Figure 4.7 illustrates the levels of total population and employment in the study area in comparison to the quarter-mile buffer generated around the existing transit stops. The map shows that areas of both high population and employment are being served in Temple, Belton, Harker Heights, and south Killeen. However, there are still many block groups with medium-to-high levels of population and employment that are not currently served by the fixed route transit system.

Key Findings

Key Findings from the overview of the existing transit network and available ridership data include:

• The existing fixed route transit system in the study area is estimated to serve just over a third of the total population and just under half of all employment.

• The highest levels of ridership activity tend to occur at major destinations such as transfer stations, medical facilities, supermarkets, and higher education facilities.

• All of the HOP routes apart from the 200 Express route operate with 60-minute headways.

• There are block groups with high levels of TTR around Temple and west-central Bell County south and east of Killeen/Harker Heights that fall outside of the existing system’s service area.

• The data analysis and feedback garnered through this study indicated that there is a transit service gap between central/ east Temple and employment opportunities in the Industrial Park.

4.2.2 Active Transportation

Active transportation infrastructure is an important component of a balanced transportation system that supports mobility for non-motorized modes of travel such as walking, biking, and wheeling. Pedestrian and bicycle-supportive infrastructure help provide facilities that enable travelers to choose non-motorized travel throughout the study area and provide key accessibility connections to people with mobility challenges. Accessibility and connectivity for people who walk and bike or use other active transportation modes is a primary goal of the Temple Comprehensive Plan 2020 and the Temple MMP.

Existing Facilities Sidewalks

Within the City of Temple, there are 173 miles of existing sidewalk. This means that over 84% of roadways that should typically have sidewalks currently lack this transportation resource. An analysis of the sidewalk data from the City’s GIS database and Google Street View imagery determined the proportion of sidewalks in each of the six sidewalk condition rankings. Results are summarized below:

• 40% of existing sidewalk is in good condition or better

• 6% of sidewalk is in Fair condition

• 40% of sidewalk is in Poor or Very Poor condition

• Fair, Poor, and Very Poor sidewalks are concentrated in the gridded central portion of Temple

• 14% of existing sidewalk did not have a reported condition ranking

Multi-Use Trails and Sidepaths

Within the project study area, there are just over 31 miles of multi-use trails and sidepath paved facilities. Currently, there are minimal designated on-street bicycle facilities, such as bike lanes or protected bike lanes, within the City of Temple. Figure 4.8 provides a snapshot of existing active transportation facilities in the study area.

Bike lanes

Active Transportation, Existing Facilities 0 0.5

Thoroughfare Connector Trail Neighborhood Connector Trail Greenway Trail

miles

Figure 4.8: Existing Active Transportation FacilitiesBicycling Comfort

Using a bicycle is a healthy, efficient, and affordable way to reach daily activities. However, safe, and comfortable facilities are needed for most people to choose cycling as a way of getting to their destination. A commonly used typology4 within active transportation planning separates potential active transportation users into four categories of bicycle user types:

• Strong and Fearless ~3%: These riders are a small portion of the population and are comfortable riding on roadways with limited or no bicycle-specific facilities.

• Enthused and Confident ~13%: These riders may feel comfortable riding where there is a designated lane for bicycles and on low-volume roadways without bicycle facilities.

• Interested but Concerned ~54%: While in a park or on a hike & bike trail these riders may feel safe and comfortable, but they have significant safety concerns while riding with traffic on the roadway. They would be interested in riding to accomplish daily needs more often if they felt safe and comfortable. This is generally the largest part of the population.

• Not Interested ~30%: This portion of the population doesn’t have interest in riding to accomplish daily activities, but they may use hike & bike trails or ride for recreation on occasion.

The takeaway from the average bicycle user type classification is that a large portion of the population (Interested but Concerned) may be able to use bicycles more often should safe and comfortable facilities be present along their route.

To better understand how cycling feels within the study area, a Bicycle Level of Traffic Stress (LTS) analysis was conducted to determine how each street is likely to feel to a person while cycling. The LTS produces a score ranging from 1 to 4, with 1 being the most comfortable and 4 being the least. The LTS score also correlates to the bicycle user types that feel comfortable using a given street (Table 4.6). As seen below, LTS scores of 1 and 2 can accommodate 70-100% of the potential riding population.

Figure 4.9: Bicycle Level of Traffic Stress

Level of Stress

The LTS analysis found that a little over 40% of centerline roadway miles in the study area have LTS scores of 1 and 2, with the majority of that being LTS 1. This is fed by the system of local streets with low speeds and volumes, particularly concentrated in the neighborhoods to the north and south of downtown Temple. The remaining 55% of roadways are ranked with LTS scores of 3 and 4, meaning that only up to about 16% of the potential riding population may feel comfortable accessing them in their current form. Outside of the Temple municipal boundary, there are many rural roadways with LTS 3 scores, and although volumes may be relatively low, potential speeds are not conducive to LTS 1 or 2 scores. Low-stress streets in neighborhoods to the far south and west of the City of Temple are also fairly isolated and have limited connections to the greater street network.

Gaps Analysis

The next phase identified gaps in the network. Generally, bicycle and pedestrian facilities end at the public right-of-way, making the last hundred-foot connection to the ‘front door’ less comfortable for access.

Critical Roadway Network Gaps

As shown in the Active Transportation Demand Analysis, there are few continuous North/South and East/West connections across the grid. The railroad is a significant barrier in this area and is likely forcing additional traffic to the few through crossstreets. This reinforces the need for a balanced roadway approach to make sure active transportation modes are accommodated on the through streets. Locations of critical gaps are identified below:

• S. 24th St., from Adams Avenue to MLK Jr. Dr.

• S. MLK Jr. Dr., from E. Avenue E to King Circle of Trail Crossings

• W Avenue F, from S. MLK Jr. Dr. to S. 25th St.

• S. 25th St., from W. H. Ave. to W. Avenue E

• Stratford Dr, from Hickory Rd to Waterford Park

• S. 5th St, from Friars Creek Trail to Temple College

• W. Adams Ave (EB), from Hilliard Rd to N. Kegley Rd.

• W. Adams Ave, from Morgan’s Point Rd to 317

Key Findings

Key Findings from the overview of the existing transit network and available ridership data include:

• 84% of roadways in Temple that would typically be expected to have a sidewalk do not.

• A large portion of sidewalks (40%) are in poor condition.

• The City of Temple’s central neighborhoods have a network of connected low-stress streets that provide a good foundation for walking or cycling.

• Many of the outlying residential areas to the west and south also contain low-stress local streets well suited for active transportation.

• Major regional thoroughfares such as I-35 and Loop 363 limit crossing to only a handful of streets to access central Temple;

• For example, between the north and south interchanges of I-35 and Loop 363, there are five opportunities to cross I-35 from east to west, all of which are high-stress roadways. The same may be true for those walking, as the presence of sidewalks are spotty approaching those crossings.

• Adams Avenue and Central Avenue separate Temple from north to south and signalized crossings are primarily on higher-stress roadways.

• The railroad line running through Temple limits roadway crossings to stressful streets shared with motor vehicles.

• Comparing high areas of demand and existing walking and biking facilities, there are gaps in areas that are also identified Environmental Justice Communities (areas where more than half of the population is low to moderate income, more than half minority, or where a quarter or more of the population is of Hispanic or Latino descent).

4.2.3 Freight and Aviation Existing Freight Network

Freight transportation continues to increase throughout Temple and is essential to the economy. The location of Temple along Interstate 35, uniquely situated between five major metropolitan cities in Central Texas, makes it an important part of the truck freight movement on the National Highway Freight Network (NHFN).

The City’s central proximity allows for north-south and east-west rail corridors. Burlington Northern and Santa Fe (BNSF) and Union Pacific (UP) are the main railroad carriers in the City. Temple was originally founded based on railroad activity to provide services for railroad equipment and passengers at a major junction point.

Figure 4.10 displays the Texas rail and freight network and how it relates to the City. As shown, there is a high level of connectivity between the Texas Highway Freight Network in orange and the railroads in purple. One outcome of the strength and diversity of the region’s freight-dependent industries is a substantial flow of commodities moving into and out of Temple and the surrounding area. Commodities moving into and out of Temple and the surrounding area are composed of a broad range of commodity types including items consumed within the region and industrial products and agricultural goods produced in the area for consumption elsewhere.

Current Commodity Flows

Based on the commodity flow information obtained from the Texas Statewide Analysis Model (SAM-V4), the City of Temple and its surrounding area were estimated to have transported over 12.7 million tons of cargo to trading partners throughout North America in 2015. Top outbound commodities include non-metallic minerals (8.67 million tons); secondary and miscellaneous cargo (1.2 million tons); clay, concrete, and glass (0.7 million tons); petroleum products (0.41 million tons); and durable manufacturing (0.33 million tons).

During that same period, the area received over 9 million tons of cargo. Top inbound commodities include non-metallic minerals (3.93 million tons); petroleum products (1.75 million tons); clay, concrete, and glass (0.85 million tons); agriculture products (0.64 million tons); and food (0.57 million tons).

Truck Movements

Existing freight movements were explored to provide a depiction of truck travel on roadways for the Temple region. The analysis found that I-35 is the dominant corridor for truck travel, though other roadways — FM 93, SH 36, SH 53, SH 317, SL363, US 190, and Sparta Rd show notable truck flows.

Figure 4.10: Texas Rail and Freight Network

Texas Rail and Freight

Texas Railroad

Texas Highway Freight Network

Truck Parking

The demand for truck parking in Temple has increased as the movement of goods continue to flow into the city and through to areas such as Dallas, Austin, and Houston. Where there is a need for truck parking is based on factors such as convenience, comfort, and shipper/receiver demand. According to the Texas Statewide Truck Parking Study completed in 2020 by TxDOT and the KTMPO 2021 Parking Study, I-35 experiences high demand for truck parking that operates over capacity near the Temple area as shown in Figure 4.11.

Figure

Source: TxDOT

The lack of parking options can lead to unauthorized truck parking. Unauthorized truck parking will cause additional congestion, safety and reliability concerns if not addressed. Several existing locations serve as the main parking options for trucks along these routes including Loves Truck Stop, Southwest Travel Center, and Texstar Travel Center.

Airport

The Draughon-Miller Central Texas Regional Airport (TPL) is located in the northwest corner of the City, near the interchange of TX 36 and TX 317. Access to the airport is solely from Airport Rd/ TX 36. Historically a US Army Air Forces Airfield, TPL now services general aviation and corporate aircraft operators. Its role is to connect Temple to regional and national markets to support the local economy. “The total operations breakdown includes 79.0 percent itinerant general aviation (GA); 14.1 percent military; and 6.9 percent local GA.”5 In addition to the runway and multiple hangers, landside facilities at the airport include the terminal building and paved parking lots.

Movement to and from the airport becomes increasingly important as the City continues to grow. Nearby development has resulted in additional regional and local trips. These trips are generally served by single occupancy vehicle pick up and drop off. However, the airport has begun to experience additional trips using ride share options such as Uber and Lyft.

Key Findings

Key findings from the overview of the existing freight network and airport include:

• Interstate 35 provides the city with the opportunity to connect between five major metropolitan cities in Central Texas.

• Notable truck flows include I-35, SH 36, SH 53, US 190, SH 317, SL 336, Sparta Rd, and FM 93.

• Demand for truck parking is increasing in Temple, and along I-35.

• Trips to and from the Draughon-Miller Central Texas Regional Airport (TPL) will continue to increase as the area grows. Accessibility to and from the airport will be key to the success of its growth.

5 Source: Author, “Airport Master Plan”, 2020, Page 17, https://issuu.com/playbyplay/docs/airportmasterplan

4.3 Safety Performance

Transportation safety data analysis provides planners, policymakers, and the public with a better understanding of where critical safety issues exist in the transportation system and what factors may be contributing to study area crashes and crash rates. As such, safety data analysis is a critical component of regional transportation planning.

4.3.1 Vision Zero

The 2017 update to the Texas Strategic Highway Safety Plan (SHSP) acknowledged a steady increase in roadway fatalities, particularly in urban areas, since 2012, despite efforts to improve roadway user behavior and upgrade roadway conditions. The SHSP maintains a vision of moving toward zero deaths on roadways, commonly called “Vision Zero.” The vision represents a multidisciplinary collaboration aspiring to make Texas travel safer by reducing crashes, fatalities, and injuries by focusing on seven key emphasis areas, including distracted driving, impaired driving, intersection safety, older road users, pedestrian safety, roadway and lane departures, and speeding.

Temple is using the tools and metrics outlined in the Highway Safety Improvement Plan (HSIP) and included Vision Zero as a goal in the MMP. That goal makes it a priority to significantly reduce and eventually eliminate vehicle related fatalities in the study area, supporting the Texas SHSP goals.

4.3.2 Analysis of Crashes in Temple

Mapping the historical crash data from the Texas Crash Record Information System (CRIS) within the City of Temple and surrounding ETJ over a five-year period (2016-2020) for both motorized and non-motorized users provides an understanding of where crashes were occurring and their level of severity.

The overall number of crashes and total severe crashes has stayed consistent over the last five years, with a slight decrease in 2020.

Figure 4.12 shows a summary of the crash counts and their severity in Temple over the last five years.

Total crash counts, especially where interstates are present, can yield somewhat misleading results as traffic volumes and the statistical likelihood of crashes are interlinked. For example, 100 crashes a year, while undesirable on an interstate with an average daily traffic count of around 19,000 vehicles, is proportionally less alarming than a local road with 100 crashes and a smaller volume of traffic. Normalizing the crash counts by volume of traffic helps refine the crash analysis to a point where locations experiencing disproportionate crash rates and severe outcomes are highlighted. To perform this analysis, vehicle miles traveled by segment were used to generate crash rates, rate of fatalities, and rate of injuries. The rates used in this analysis are expressed in terms of million vehicle miles (MVM) traveled.

High Crash Rates

Figure 4.13 shows the crash rates by segment and highlights a few key locations with the highest rate of crashes. A few locations, due to segment length and low volume of traffic, are shown to have a disproportionate rate of crashes. A small segment of Old Cedar Creek Road near the intersection with 317 has two crashes over the 5-year period and a low volume of approximately 100 average daily traffic (ADT) count, which in turn yields a high crash rate. Similar results are seen with a small segment of Woodland Trail just south of FM 2305, and High Crest Drive to the west off of FM 439. Two segments between W. Adams Avenue and W. Central Avenue in central Temple are shown as well. In these cases, N. 29th St. had 42 crashes and 27th St had 16 crashes.

Figure 4.13: 5-Year Crash Rates by Segment

Five-Year Crash Rate (2016-2020)

Highest Rates of Severe Crashes

Segments with high rates of fatalities combined with high rates of serious injury rates provide a better understanding of where localized rates of severe outcomes were occurring. The personlevel data, rather than the crash level data, informed both fatal and serious injury rates.

The following are identified as “fatal segments” of the roadway:

• Nolan Loop, which connects FM 439 to FM 93

• S. Cedar Road, off of FM 2305

• Reads Lake Road

• S. 57th Street, just north of I-35

• S. 49th Street to the south of I-35

• N. 25th Street, between W. Adams Avenue and W. Central Avenue

Additionally, nine are identified as “serious injury” segments of the roadway:

• West of I-35, Executive Drive, just north of W. Adams Avenue

• Draper Drive, just off of Airport Road

• Hart Road

• N. 21st Street

• S. 7th Street

• N. 7th Street

• E. Jackson Street, just south of Jackson Park

Contributing Factors

Understanding factors that contribute to crashes, especially those resulting in serious injuries or fatalities, adds depth to a comprehensive crash analysis and informs the development of strategic solutions. Of the top ten contributing factors identified, the top factors (in terms of total crashes) were speeding, failing to yield the right-of-way, and erratic driving. A portion of data entries was noted as having “No Data” or “Other” in the contributing factors fields, though the crash data did note other factors including distracted or inattentive, swerving or veering, or improper changing of lanes. This data highlights the propensity of certain types of crashes on the system and provides for a more systemic approach to developing solutions that address risk and severity reduction.

4.3.3 Active Transportation Crashes

Walking and bicycling are the two most basic forms of transportation, referred to as active transportation. While people traveling in a vehicle that has been engineered with crumple zones, seat belts, and airbags are inherently buffered from more severe outcomes in the event of a crash, persons traveling by various means outside a motorized vehicle are inherently more susceptible or vulnerable to severe outcomes. Evaluating the safety of active transportation users on the network follows a process similar to that used to analyze vehicular crashes. Over the five years, there were 197 active transportation users affected by 186 crashes. Of those, there were 12 fatalities, 30 serious injuries, and 62 minor injuries. Figure 4.14 shows the locations of active transportation crashes and their severity.

Several segments in the study area are identified as having high active transportation severe crash rates, including:

• S. 31st Street, two fatalities just north of US 190

• 31st Street, several severe injuries south of Canyon Creek Drive and near the intersection of W. Avenue J

• S. 31st Street, two serious injuries occurred on W. Avenue R and W. Avenue T

• US 190 near and at I-35 had several severe crashes, including 3 fatalities

• S. 1st Street between W. Avenue J and W. Avenue F had a few crashes with one fatality and two serious injuries

• SH 53, 3 fatalities and 1 serious injury

Active Transportation Contributing Factors

Active transportation crashes were reviewed for contributing factors. Other than crashes with no data or “other” noted for contributing factors, the top four contributing factors noted were distracted driving, failure to yield, erratic driving, and speeding.

4.3.4 Key Findings

Key findings from this analysis include:

• Speeding is the top contributing factor for all crashes and for those that result in a fatality or serious injury.

• Distracted Driving is the highest contributing factor for crashes involving active transportation.

• Vulnerable users, i.e., pedestrians and bicyclists are at a higher risk of fatality or serious injury in a crash.

• Single vehicle or same direction collisions were the top collision type for speed-related contributing factors.

Figure 4.14: Active Transportation Crashes by Severity

Active Transportation Crash

Severity

Fatal Injury

Suspected Serious Injury

Suspected Minor Injury

Possible Injury

Not Injured

Unknown

Source: CRIS

4.4 Travel Demand Management

A review of current and past efforts to pursue Transportation Demand Management (TDM) strategies in Temple provided an understanding of the current knowledge of and support for Transportation Demand Management by the City’s elected officials, staff, and the leaders of other partner agencies. The review produced examples of interest in TDM on the part of the City and KTMPO, but there was no evidence of past efforts to establish formal TDM programs or current efforts underway. However, interest in TDM was expressed in several local and regional plans such as the City of Temple’s Comprehensive Plan and KTMPO’s 2045 MTP.

4.4.1 Existing Mode Share

The current level of mode use for commuting assembled in Table 4.7 shows the shares for 2018 and 2015. The results indicate that commuting in Temple is highly car-oriented with 82.9% driving alone and 10.9% carpooling. A comparison with the 2015 results suggests a small shift from driving alone to carpooling has occurred but the overall share using a car has remained about the same. Bicycling and walking to work have decreased, and working at home has increased.

4.4.2 Key Findings

Key findings from this analysis include:

• No current City or regional TDM program in place.

• Interest expressed in previous plans.

• The majority of the residents drive alone (82%).

This page intentionally left blank

CHAPTER 5

EVALUATION OF FUTURE CONDITIONS

5. EVALUATION OF FUTURE CONDITIONS

5.1 Anticipated Growth Patterns

The City of Temple is projected to grow as more residents and businesses move to the area. Areas where the density of population and employment are expected to grow rapidly were thoroughly analyzed for the potential impact on the future transportation system. Mobility needs and service gaps, along with solutions and recommendations, emerge through comparison of future travel demand with the planned transportation system. Having a plan for improvements in place will help the City respond to funding opportunities as they arise. Additional details on each element discussed in this chapter can be found in Appendix B: Comprehensive System Assessment Technical Memorandum.

5.1.1 Population and Employment Growth

Over the past decade, the City of Temple and its ETJ have seen a significant amount of population growth—particularly in the past five years. Forecasted population shows nearly 180,000 residents projected in 2045. Areas where growth has developed more rapidly in recent years are expected to continue this trend well into the future.

Figure 5.1 shows the growth of the City of Temple and ETJ total population and forecasted population.

Based on an analysis of population and employment projections, the following trends were identified:

• Growth will expand into the ETJ.

• Population and employment will grow in parts of Temple adjacent to communities (e.g., Belton, Troy).

• Population will increase north of downtown.

• Population and employment within Loop 363 will increase.

• Employment will increase to the northwest of downtown, specifically around Loop 363.

• Employment will continue to grow along I-35.

• Population will increase at a high percentage along Loop 363 and south of SH 190.

• Employment will increase in the northwest portion of the study area, surrounding Pendleton.

• Population will increase at a low to moderate growth rate near existing residential development.

• Population and employment will experience a low change around Belton Lake on all sides except to the west near Fort Hood.

Source: ACS 5-Year Data historical data; KTMPO travel demand model population forecast.

(2019-2045)

Source: American Community Survey (ACS) 5 YR (2019) Projected populations use TexPACK V 2.4 KT model

Figure 5.2: Percent Change in Population and Employment from 2019 to 2045 by TAZ

Figure 5.2: Percent Change in Population and Employment from 2019 to 2045 by TAZ

5.1.2 Household Income and Cost of Living

Based on the development patterns of growth into the ETJ— and even longer commute distances—affordability in Temple may become more challenging. The MMP uses the Center for Neighborhood Technology’s (CNT) Housing and Transportation’s Affordability Index metric on housing and transportation cost to assess the overall affordability of the study area. CNT has determined that places where housing and transportation costs are greater than 45 percent of the area’s median income should be considered unaffordable.

Some areas of Temple were already considered unaffordable based on their combined housing and transportation costs, specifically areas south of Temple and near Morgan’s Point Resort. Housing costs in Temple are relatively low (ranging from 20 to 35 percent of the area’s median income), but transportation costs become gradually higher as people live farther away from downtown. The increases in transportation costs in areas without employment density are expected due to longer commute times and distance. This trend highlights the need to plan for mobility options that provide manageable commute times.

5.1.3 Key Findings

• Study area population is expected to grow by roughly 34% (45,861) and employment is expected to grow by 66% (39,020) over the next 25 years (2019-2045).

• Population and employment are expected to increase throughout the study area, with a higher percentage increase occurring around Loop 363 and to the north of Temple.

• Employment is expected to increase along I-35 and generally throughout the study area.

• Temple has a small but growing population of 55 and older, a declining population between 40 – 54, and a growing population of 25 – 39 years old.

• There is anticipated growth in goods and freight movement in the region.

• Future land use for Temple allocates 42% to industrial and 26% to rural/estate uses. Planning for freight movement and infrastructure that supports truck traffic will be critical to support this growth.

5.2 Transportation Demand Modeling

5.2.1 Roadways

The KTMPO Model 2045 forecast year conditions were used to evaluate emerging and future trend scenarios. The future conditions roadway deficiencies analysis provides policymakers and the public with a better understanding of how the roadway network is currently performing.

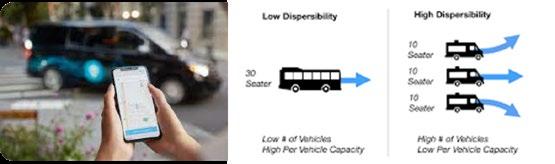

Future Capacity Deficiencies