ESFERAS

cross / currents ~ contra / corrientes

Spring 2023 | Issue No 14

The Undergraduate Journal of the NYU Department of Spanish and Portuguese New York, New York

COVER PHOTOGRAPH: Nadia Huggins

From Circa No Future

Believing there to be a link between an under-explored aspect of Caribbean adolescent masculinity and the freedom of bodies in the ocean, I set out to document boys’ interaction with the sea. Created since 2014, these photographs capture manhood, snippets ofvulnerability and moments of abstraction that often go unrecognized in the day-to-day. The ocean itself takes on a personality—that of the embracing mother providing a safe space for being—which is both archetypal and poignant. The boys climb a large rock, proving their manhood through endurance, fearlessly jump, and become submerged in a moment of innocent unawareness. They emerge having proven themselves. The relationship between the boys and me is also explored within this paradigm. They are aware of me while posturing, but lose self-awareness when they sink into the water.

ESFERAS-ISSUE FOURTEEN * SPRING 2023 wp.nyu.edu/esferas/

SUBMIT TO esferas.submissions@gmail.com

MANAGING EDITOR Lourdes Dávila

INTRODUCTION TO THE DOSSIER Lourdes Dávila with the Esferas editorial team

EDITORIAL TEAM Elizabeth Baltusnik, Zara Fatteh, Monserrat Gabisch, Alexa Melody Leon, Deborah Molina Rodriguez, Lorraine Olaya, Félix Romier, Valentina Ruiz, Spencer Harrison Tsao, Ryan Wasserman

LAYOUT AND DESIGN Sam Cordell with the Esferas Editorial team

COVER DESIGN Sam Cordell

COPYRIGHT © 2023

ESFERAS & NEW YORK UNIVERSITY’S DEPARTMENT OF SPANISH AND PORTUGUESE

ISBN 978-1-944398-18-7

RIGHTS & PERMISSIONS ALL RIGHTS REVERT TO THE ORIGINAL CONTENT CREATORS UPON PUBLICATION. THE EDITORS WILL FORWARD ANY RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS CORRESPONDENCE TO THE AUTHORS.

ESFERAS is a student and alumni initiative within New York University’s Department of Spanish and Portuguese.

We are a peer reviewed publication that publishes critical essays, visual art, creative writing, interviews, translations, and works related to Hispanic and Luso life within and beyond New York City.

ESFERAS, “sphere” in both Spanish and Portuguese, is a fusion of compelling images, distinctive voices, and multidisciplinary views. It is the ever-changing shape and infinite flow of our creative and intellectual pursuits.

The First Object Which Saluted My Eyes Was the Sea (And the Slave Ship)

Crónicas

How Content Creators Are Using Entertainment Media to Get More People Speaking Spanish

Pánico y el Rey Lagarto

Y todos bajaremos juntos

Nunca me rajé

DAHA

Senior Honors Theses

Biographies

Sophia Moore

Aldi Jaramillo

Olivia Ochoa

Manuel Barrós (selección y traducción)

Iris Fitzsimmons Christensen

Mina Chen

Iván Brea

Mahir Rahman

Brandy García

Vanessa N. Sevilla

Carina Christo

Carlo Yaguna

Trace Miller

Daniela Sandoval

Stephanie Farmer

cross / currents ~ contra / corrientes

I

n t r o d u c t i o n

Lourdes

Dávilawith the Esferas editorial team

What new knowledge and forms of agency can we gain when, as human beings shaped physically and intellectually by our “terrestrial habits of movement” we agree to perform what Melody Jue terms a conceptual displacement (Thinking through Seawater) in order to think from, within and through the water? How can we dive “offshore” to develop a “map of what it means to be human in certain parts of the world” (Nadia Huggins) and understand, imagine and theorize otherwise our particular histories and environments? How does this mapping bring to light new relational geographies that allow, as Yolanda San Miguel explains in “Colonial and Mexican Archipelagos. Reimagining Caribbean Studies,” a re-definition of the term archipelago, in order to integrate seemingly disparate island chains, thereby complicating “our conceptualization of the Caribbean in conversation with other regions that share a similar set of conditions?” This is a difficult task, since, as Jue tells us, our language originates from our experience as land animals:

If one agrees with Ludwig Wittgenstein’s observation that to imagine a language is to imagine a form of life, then it is clear that human languages have taken form within a range of terrestrial and coastal environments that, at minimum, all share the experience of gravity and horizontal (rather than volumetric) movement. (Jue 2)

It is precisely this task of seeing, experiencing, thinking and theorizing otherwise that the NYU Cross/Currents Humanities Lab explores, taking water as essence, conduit and dynamic force and working across disciplines to build new vocabularies and imagine new forms of theorization and agency:

The Cross/Currents H-Lab takes the word currents as its inspiration, as both a metaphor and a tool, enveloping not only its main definition in relation to water and its movements, but also its broader reverberations. By connecting the words cross and currents, our main goal is to bring into dialogue environmental humanities and migration studies (with an emphasis on race, diaspora, and indigeneity). In our work together we hope to rehearse ways of bringing literary and artistic analyses to bear on issues of the environment and migration, and vice-versa. We have outlined three main trajectories around the notion of Cross/Currents: mobility, transmission, and flow. Mobility considers how water has been a conduit for migration—the movement of people and non-human elements—with its historic and contemporary iterations defined by violence and trauma. Transmission engages recent scholarship in media studies, the history of science, and the history of

technology. It pushes us to think about the material aspects of technologies, and to consider newer models of communication like undersea cable systems or transoceanic internet traffic. Finally, we use the flow of water and air as points of reference from which to build new critical vocabularies and frameworks for knowledge production beyond traditional conceptualizations of human agency. Our ultimate purpose is to decenter an anthropocentric and imperialistic understanding of global interconnection and exchange (“Cross/Currents. End of Year Report”).

The editorial team of Esferas 14 is delighted to partner with the members of the Cross/Currents Humanities Lab to think about and expand on the questions and theories proposed in their study. This partnership is quite fitting as we celebrate the 10th year anniversary of our journal. Our very premise is to create a transdisciplinary space for the production of and reflection on a wide variety of topics, with the belief that the dialogues that arise offer new perspectives and modes of experiencing and acting in the world. It is essential for our team to give equal value to the work of new and seasoned artists, critics, theorists and scholars, and we believe Esferas 14 is exemplary in this regard.

We have been fortunate in the past to work on similar partnerships: Issue 12, Migration and Asylum, was done specifically in association with the H-Lab “Asylum and Im/migration” and Issue 13, Spaces/Institutions/People, celebrated the 25th anniversary of the KJCC and worked in tandem with the undergraduate class “Institutions, Archives, People.” The Cross/Currents Humanities Lab is a collaborative project spearheaded by professor Luis Francia from the Department of Social and Cultural Analysis and professors Jordana Mendelson and Laura Torres-Rodríguez from the Department of Spanish and Portuguese, with the essential participation of PhD students Dantaé Elliot, Fan Fan, Erica Feild, Linda Luu, Michael Salgarolo, Emilie Tumale, Mariko Chin Whitenack, and Lee Xie. The team brought in guest speakers from various backgrounds over the course of the spring 2022 seminar, “Cross-Currents Lab: Ocean as Myth and Method,” including Sint Maartener and Dutch artist Deborah Jack, Puerto Rican artist Sofía Gallisá Muriente and curator Arnaldo Rodríguez-Bagué, NYU Courant Professor Andrew Ross, Professor Vicente Díaz, the team from the Billion Oysters Project, chef and restaurant owner Amy Besa, and playwright and actor Claro de los Reyes, among others. The Cross/Currents Humanities Lab is generously supported by Dr. Georgette Bennett in honor of Leonard Polonsky CBE under the guidance of Molly Rogers, associate director of the NYU Center for the Humanities. With their help, Esferas is able once again to provide a platform for artists and authors to showcase their works and encourage others to engage with them.

Formally and ideologically speaking, the work of the Cross/Currents H-Lab refers back to work we have published throughout our journal in the last ten years. In her introduction to the dossier for this issue, Laura Torres-Rodríguez underscores the work Assimilate and Destroy (2018-2020) by the artist Sofía Gallisá Muriente, which explores the process of deterioration and impermanence of images on celluloid. We think back on Issue 9, Tracing the Archive, and the work of Jens Andermann “La ausencia fulgurante: archivos virales en Restos Cuatreros de Albertina Carri,” where the author considers Carri’s work within the affective materiality of images and the significance of luminous traces that face continuous processes of natural erosion. And as TorresRodríguez thinks with Jue about the way that marine squids transmit information and maintain memory, or about the “bodily practices and narrative acts that challenge the imperialistic and scientific construction of the islands as isolated territories,” we refer to the dancer and philosopher Marie Bardet, who in several issues of Esferas spoke of the implications of a human body that bears weight as it moves and weighs thought with its movement (“Extensión de un cuerpo pe(n)sando,” Issue 6, Turn to Movement); the possibility of “turning our backs into fronts” (“Making a Front with our Backs,” Issue 8, Precariousness); or the narration and re-enacting of the archive through practices of the body (“‘Hacer memoria con gestos’. Relato de una conversación colectiva y diseminada.” Issue 9, Tracing the Archive). The H-Lab course’s work with the Billion Oyster Project, and the “Letters in Conversation” in this issue written by Eleanor Macagba, Bry LeBerthon and Gray Cooper Mahaffie, respond to an invitation to “smell, taste and touch [as a] first step in the creation of a more reciprocal relationship with these [originally Lenape] lands and waters.” From the very beginning of their work, the authors of “Letters in Conversation” grappled with how to transfer their situated knowledge into written narratives, and settled on letters in dialogue as a format, following the inspiration they received from “On Water, Salt, Whales, and the Black Atlantics: A Conversation between Alexis Pauline Gumbs and Christina Sharpe.”

At stake here is how we think of our bodies in relation to the spaces we inhabit; in this sense Marie Bardet, considering Gilbert Simondon’s philosophy, speaks of the skin as a relational membrane that approaches the disappearance of full interiority and exteriority and admits a certain degree of porosity and transparency while maintaining interior and exterior as sediments, accumulated and in constant movement, of past and present relationships (Bardet 142). Her workshops “des-orientarse pe(n)sando,” read by Lourdes Dávila in Tracing the Archive, saw the creation of the terms “afuerándose” and “adentrándose” (a tendency toward the outside; a tendency toward the inside) while working on the skin as a membrane at the limit between inside

and outside. Within this issue’s dossier we have the work of artist Nadia Huggins and three of her photographic series: Transformations, Circa no Future, and Disappearing People. Of her diptychs forTransformations, Nadia Huggins states:

This space [between the body of the photographer and the underwater organisms in the diptychs] represents a transient moment where I am regaining buoyancy and separating from the underwater environment to resurface. My intention with these photographs is to create a lasting breath that defies human limitation. The transformation exists within the space in between photographs. It is in this moment that the viewer makes the decision if both worlds are able to separate or merge.

If Transformations explores vividly this relationship between the “afuerándose” and “adentrándose” of the human body in water, Hannah Siegel’s work, “The First Object Which Saluted My Eyes was the Sea (And the Slave Ship),” inspired on one of Nadia Huggins’ photographs in her series Circa No Future, extends the relationship of bodies in and with water to think about colonial objects (namely the bronze statue of colonial-era slave trader Edward Colson) flung into the sea and “dominated by different qualities of pressure, light, salinity, and a world of organic creatures.” What happens to the colonial legacy, Siegel asks us, “when we soak it?” Should we make it endure as part of a project of punitive justice? Or should we allow the water to erode, with its climatic violence, the very structures that sustain colonial history?

Arnaldo Rodríguez Bagué poses this last question in “Oceanic Decolonial Ruination.’’ In their essay, Rodríguez Bagué reads Teresa Hernández performance in the Vieques’ Fortín Conde de Mirasol, a 19th century Spanish military fort on the northern coast of Vieques, Puerto Rico, in the aftermath of Hurricane María (2017). They conclude: “By specifically bringing ruin upon the Caribbean islands’ colonial-built environment, the Knife Woman’s acceleration of climate change’s oceanic futurity uses the geological monumentality of Vieques’ Fort as a sculptural medium for carving out a Puerto Rican decolonial future as part of Hurricane María’s recovery process.” Before the dossier, we walk with Eduardo Lalo’s poem “San Juan de los demonios”’ and his photographs of San Juan along with an intimate depiction of a city “from which the sea was stolen and hope was turned into waste by looters.” If Rodríguez Bagué looks at climatic and colonial violence and considers the possibility of a decolonial future and a recovery process through the performance art of Teresa Hernández, Lalo’s work dwells on the present and the love born within an island ravaged by colonial and imperial powers. Movement (as the poet walks through the city and takes photographs) is key to the resistance posed by the author of “San Juan de los demonios.” In “Ensueños a/sombra de agua // Reveries in the Shadow/Awe

of Water” Rolando André López Torres grounds his reading of Foreign in a Domestic Space in a devastating subtitle that appears on the screen to speak about the reality of life in Puerto Rico after the passing of hurricane María: “We still don’t know, at least not yet, how to move freely.” This quote, from André Lepecki’s “Choreopolice and Choreopolitics,” is a chilling comment on life in the island after María that politicizes stasis and places it as the tragic effect of colonial and climatic violence. The quote also sets the stage for a “complete aesthetic submersion into a multiplexed narrative of estrangement and belonging” that is the project Foreign in a Domestic Space.

Mario Bellatin’s “Placeres” (reworked for this issue of Esferas) is a tight grid where words containing elements from across his writing function as a skin or organic membrane enveloped by and immersed in liquids (“Agua. Petróleo. Fluidos del cuerpo. Sangre. Aceites. Ácidos. Lágrimas. Esperma.”). It is these liquids that both fix and erase the limits of bodies and their representation. Bellatin pairs the blood produced through violence and needed to “write on the walls the motives of crimes” with the chemicals necessary to fix a photographic image and to make the image emerge from a plate. In this way, the very technology of the photograph is accused of imperial fixity and violence as Bellatin continues to write, using water as the fluid that contains all histories (from the writing of the codices to the present), all forms of violence, all forms of potential ablutions and transformations. And yet, “Nada de eso existe. Salvo en lo líquido. Dentro de su estar acuoso. A través de los siglos. Tiempos que se sobreponen, unos a otros, hasta formar un cuerpo. Único. Compacto. Desecho. Diluido. Una materia sostenida, solamente, por la fruición con la que millones tratan de mantener intacta su pureza. Piel y sustancias. Ofrezco líquido. Exijo líquido.” The body (of Bellatin’s writing) offers a sense of continuity where limits are erased in a mediality of endless transformations while invoking an endpoint in a grid that fixes itself in itself. In water. “Bálsamos. Cinco poemas de Tito Leite” selected and translated by Manuel Barrós, seems to establish a dialogue with the work of Bellatin and his use of water by looking at the origins of the relationship between water and language: “Antes do homem,/ os peixes brincavam/nos grânulos da linguagem” (“Antes del hombre,/los peces jugueteaban/en los gránulos del lenguaje”). And of course, Oscar Nater’s work for this issue of Esferas includes images of Jacobo el Mutante, a performance his company ÍNTEGRO developed following Mario Bellatin’s writing.

Elsewhere in the issue, it is water as a ritual of/and for movement that is summoned. Artist Quan Zhou’s project Aquel verano (a series of acrylic paintings that originated in the photographs taken during the first summer she and her parents went together to the beach on the south of Spain) questions the monolithic narrative of migrant suffering to focus on the quotidian enjoyment of a day at the beach. Aldi Jaramillo gives us in “Water Is Healing” a visual portrayal of the curative power of water. Visual artist and choreographer Oscar Naters speaks of his work in ÍNTEGRO and about the permanent presence of water in his creative experience, reminding us how water belongs in an expansive space that is profound and mysterious. Sophia Moore, in “Diasporic Whales,” highlights the migrational history of colonialism and engages with the Cape Verdean diaspora in New England and its relationship to “seafaring histories, especially concerning whaling, shared between Portugal and the United States.” Moore concludes that “[t]he connection between Cape Verde and New England, today the home to the largest Cape Verdean community in the world, rests on [a] shared aquatic history forged through the whaling industry.” We can also trace a relationship between movement and migration with Olivia Ochoa’s story “Mira,” Michel Nieva’s science fiction story “La guerra de las especies,” and Lorraine Olaya’s poems. “Mira” is a narrative staged as a facetime conversation between a young woman who has migrated to the US and her family; the story looks into the tensions of leaving home with the promise of attaining social mobility. In “La guerra de las especies” the narrator enters into a war for profit between racoons and rats in Inwood Hill Park after the pandemic closes all borders and prevents him from returning home, although“while the restrictions may have meant [he] couldn’t go back to Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires had come back to [him]” as a nightmare. And Lorraine Olaya makes movement the very basis of her poetic interpretation of cumbia, the rhythm of the drums and the languages that oscillate between embodiment and burial, between English and Spanish.

This edition of Esferas explores the idea of currents and transformations through gender. In “The Flowing Gender” Mina Chen dissects Alain Badiou’s “Dance as a Metaphor for Thought” in conversation with the iconic dance Swan Lake. Chen centers her argument on the relationship between nature and human and points out the preexisting strict gender roles that exist in the world of dance while underscoring possible elements of hypocrisy in Badiou’s argument on the effaced omnipresence of the sexes. In “Una masculinidad agresiva: masculinidad destructiva en ¡Vámonos con Pancho Villa!” Iván Brea analyzes a scene from the 1936 Mexican film and argues for the director’s anti-machismo view throughout the film, allowing for a more complex and flexible

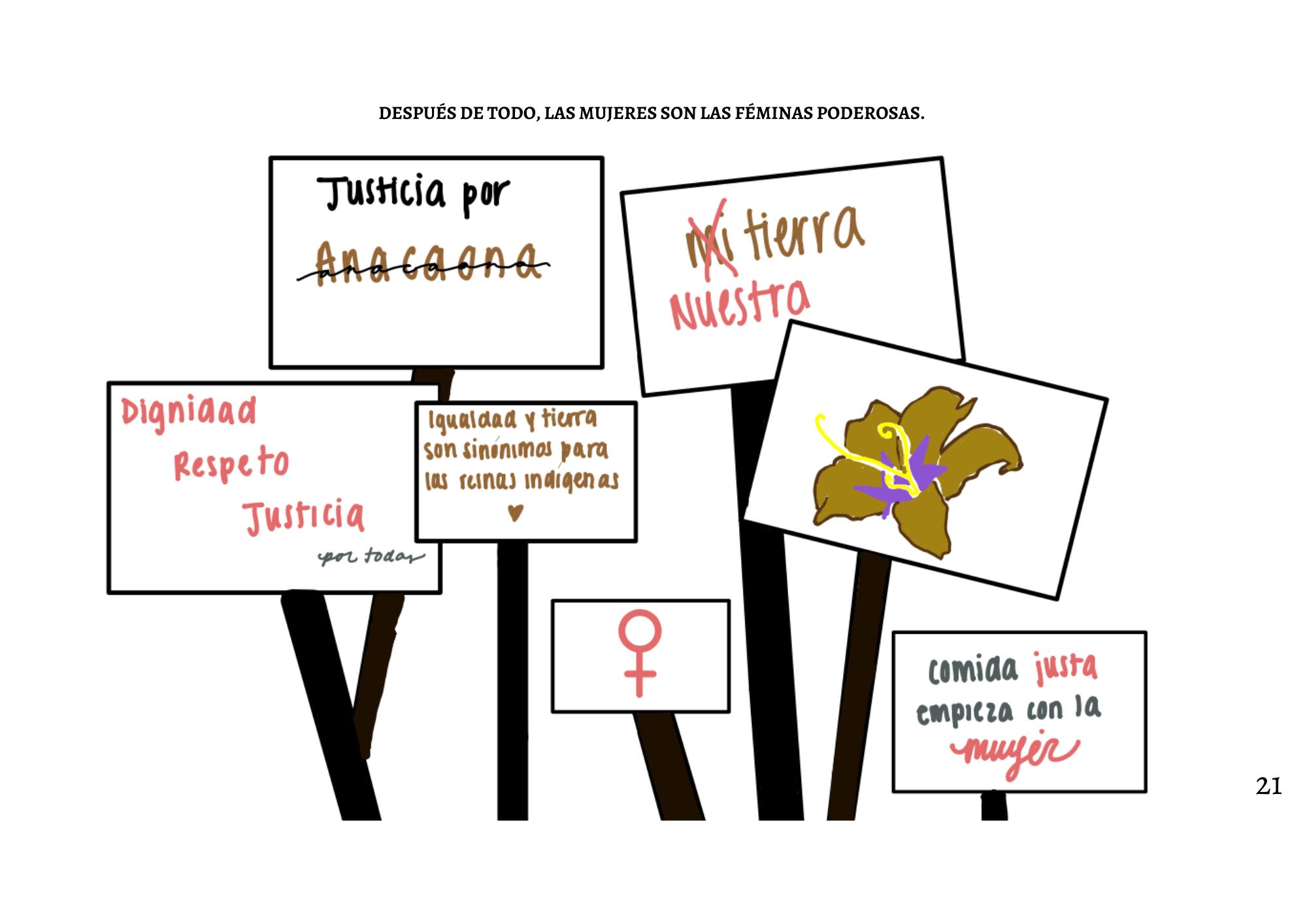

masculinity. And “La fémina poderosa” is a narrative in comic form in which Mahir Rahman traces the story of colonization and leads us to see that equality and land, as well as access to fair food practices, are synonymous with justice for all women.

There are many other wonderful texts that we invite you to read in this issue. Among them, an excerpt of the journal DAHA, developed and directed by Stephanie Farmer in NYU Buenos Aires with fellow colleagues from NYU.

As is our tradition, we are proud to share with you the abstracts of our senior honor theses; whether working with computer technology to create the prototype of a game that addresses kitchen Spanish in New York City restaurants, or tracing the movement of the painting Las Meninas to consider the political appropriation of art, or looking into the role of religious figures in Mexican film, or understanding the history of commodification of dual language/ dual immersion programs in New York City public schools, our seniors continue to push the envelope of our discipline and give vibrancy to a department that bases its scholarship on interdisciplinarity and diversity.

Please join us in celebrating our 10th year anniversary and enjoy Issue 14 of Esferas!

Works Cited

Bardet, Marie. Perder la cara. Buenos Aires: Cactus, 2021. Jue, Melody. Thinking through Seawater. Durnham: Duke University Press, 2020. San Miguel, Yolanda. “Colonial and Mexican Archipelagos. Reimagining Caribbean Studies” in Archipelagic American Studies. Durnham: Duke University Press, 2017, 155-173.

San Juan de los demonios

Eduardo LaloAmadas calles odiadas de los días inevitables de las múltiples vidas San Juan de demonios imperiales y pequeñeces autóctonas La miserable por historia e imaginación chica

Año a año la inercia y el amor me mantuvieron en ti repitiendo tu catálogo de desgracias

Así he agotado mis días en avenidas desarboladas

Por décadas opté por habitar la desolación de tus aceras y ninguna parcela del orbe ha sido más recorrida que tus avenidas

Y sin embargo tu desesperanza hizo la cruel ternura de la mía Viví entre enemigos que no te vieron más que como un botín Dolido por lo que pudiste ser: la ciudad a la que le robaron el mar y la esperanza a la que los espoliadores convirtieron en desperdicio

Pero en ti San Juan de los delirios hallé y viví las humanas condiciones y tus estragos se convirtieron en formas de querencia hasta devenir el metro del amor de todos los amores

Mi paisaje mi ruido mi polvo el mar el cielo las lluvias

No existiría el mundo sin tus calles ciudad comprada con el desprecio de tus adversarios

Madre padre hermana amiga: pasado hecho herida dolor de futuro

Pero mi nombre no existiría sin tu vida San Juan de los demonios desolación sufrida

La brisa

Isabel Fadhel CarballoLa brisa que mueve las hojas, que mueve la arena, mueve tu pelo, me mueve hacia ti. Natural, fácilmente –hacia tu piel, hacia tu ser, la brisa me lleva a conocer.

Las manos del viento me empujan con su música y me encuentro bailando. Bailando hacia ti, hacia tu piel, hacia tu ser.

Con ritmo y ternura mis brazos te acogen y la brisa pausa –por menos de un segundo, una eternidad efímera. –

Y cuando reinicia, vuelve fuerte y apasionada y ahora nos movemos juntos. nuestros cuerpos hechos uno. Y la brisa nos mueve.

Como mueve las hojas, la arena, tu pelo. Nos mueve.

Serra Pelada: La fiebre del oro

Kenzie DavidsonNo one is taken there by force, yet once they arrive, all become slaves of the dream of gold and the need to stay alive. Once inside, it becomes impossible to leave […] Anyone arriving there for the first time confirms an extraordinary and tormented view of the human animal: 50,000 men sculpted by mud and dreams.

Sebastião Salgado (“The Hell of Serra Pelada Mines through Photographs, 1980s”)

En la década de los ochentas, el fotógrafo brasileño Sebastião Salgado visitó las minas de oro de Serra Pelada en el bosque amazónico y realizó una impresionante y poderosa colección de fotografías centrada en la fiebre del oro que atrajo a miles de personas a la caza de riquezas. Muchas de las fotografías de la colección se convirtieron en imágenes icónicas del momento, entre ellas la foto de un niño medio desnudo y cubierto de barro, cargando un saco sobre sus hombros mientras su mirada se fija en un punto lejano1.

La foto, en blanco y negro, juega con la luz natural para añadir contraste y dramatismo a la escena. Lo real se ve matizado por los juegos de luz y sombra producidos con la cámara, que congelan al niño y lo convierten en una escultura de barro. La foto se enfoca en el tema principal, un niño que está trabajando en las minas, detrás del cual se observa a muchos otros trabajadores desenfocados al fondo de la foto. La foto presenta un contraste entre el movimiento difuso al fondo y la figura del niño, que se suspende incómodo e inmóvil en un exagerado primer plano. Se trata de un primer plano paradójico: el ojo de la cámara está claramente dentro de la escena, pero el primer plano parece expulsar al fotógrafo (y al observador) violentamente del espacio fotografiado. La noción de perspectiva es muy importante cuando se piensa en esta paradoja porque las formas en que el fotógrafo enmarca y ajusta la foto la transforman y cambian los discursos que surgen de ella.

Esta foto fue tomada durante un momento histórico en Brasil. El descubrimiento de oro en la Serra Pelada dio inicio a una fiebre extractivista. La mina fue cerrada más tarde debido a los peligrosos deslizamientos de tierra y ahora es un lago totalmente contaminado con mercurio que pone en peligro a la selva amazónica. “To this day, tensions persist between the garimpeiros, the Brazilian government, and multinational mineral companies over control of Serra Pelada.”

(Brazil: Gold Rush in Serra Pelada). La mina era peligrosa y violenta, y Salgado hizo todo lo

1. La foto de la que se habla en este ensayo puede verse aquí: publicdelivery.org/swebastiao-salgado-serra-pelada-gold-mine-brazil/

posible para documentar principalmente las realidades y dificultades de Serra Pelada. Esta fotografía, como las otras fotografías de Salgado, poseen una belleza estética indiscutible. ¿Cómo abordar el análisis de la fotografía cuando existe una paradoja significativa entre la fotografía utilizada como documentación de eventos versus la belleza de su expresión artística? Podríamos considerar la diferencia entre el studium y punctum bartheano como una primera respuesta. El studium de una fotografía, que según Barthes produce una atracción o interés inicial, es informado por la sociedad y la cultura. Es una serie de códigos presentes en la foto que se refieren directamente a la política, la cultura y la historia del momento. No existe ni studium ni contrato entre el fotógrafo y el observador sin la cultura y la historia que la produce (Barthes 28). El dolor y deseo de esta foto tienen como referente el capitalismo extractivista que fuerza a las personas a someterse a trabajos inhumanos por la posibilidad de obtener riquezas. El punctum, sin embargo, es diferente. Como dice Barthes, el punctum de una fotografía es un accidente que te pincha o te mueve (27) que te atrae o te angustia (40). El punctum es algo más allá de la fotografía misma –es el efecto de la foto. El punctum pertenece al observador y gira alrededor del afecto. No hay código que pueda explicarlo y a menudo el efecto del punctum no es una experiencia compartida. Para mí, el punctum de esta foto es la forma en que los ojos y la mirada del niño me hacen sentir. El dolor, la confusión, la desesperación y la preocupación en la cara de un humano tan joven perdura dentro de mí mucho después de haber terminado de mirar la fotografía. La esencia que Salgado captura en esta foto es tan cruda, que la hace más significativa y memorable, así como más auténtica.

Un aspecto interesante de esta foto es que el punctum anula el studium y en última instancia atrae más atención. Un studium proviene del conocimiento cultural. Si es cierto que hay ciertos elementos en la foto que pueden proporcionar pistas sobre lo que está pasando en la foto, el studium es en realidad una especie de ausencia. Esa ausencia es también una demanda para los observadores, una invitación a profundizar en el contexto. Pero lo que verdaderamente tiene poder en esta foto es su punctum, la herida inmediata que provoca. Todo lo que el observador puede ver es un niño en una situación horrorosa retratada muy artísticamente. Debido a esta presentación, el dolor de la foto se enfrenta de forma perturbadora con la belleza de su presentación. Te pincha, lo que es la esencia del punctum.

La paradoja entre documentación y arte en términos de fotografía es algo muy criticado, y dos críticas a destacar provienen de Susan Sontag y Siegfried Kracauer. Sontag afirma que “Although there is a sense in which the camera does indeed capture reality, not just interpret it, photographs are as much an interpretation of the world as paintings and drawings are.” (Sontag 4). Ella no cree que las fotos sean completamente realistas y que siempre contienen algún tipo de interpretación. Estoy de acuerdo con esto hasta cierto punto, pero creo que ciertas fotos pueden

reflejar más la realidad que otras. Kracauer también da prioridad al realismo. La foto de Salgado y el resto de su colección muestran la brutal realidad de la vida en la mina. A Krakauer no le gusta construir la narración de un evento (Krakauer), pero esto es difícil de evitar porque la fotografía involucra elecciones sobre los sujetos y ángulos que inherentemente controlan la narrativa. Salgado no está manipulando la escena en el sentido de que esté añadiendo elementos, por lo que en ese sentido es real, pero al elegir a sus sujetos y los ángulos específicos de la toma las fotos todavía manipula la historia de una manera.

Si realmente no es posible capturar la realidad con una cámara, la fotografía seguirá siendo el acercamiento más vital a ella. A lo largo de su obra, Salgado utiliza su arte para realizar una auténtica representación de la vida en las minas. Si no podemos comprometernos a creer que las fotos pueden ser utilizadas como evidencia porque siempre hay algún tipo de manipulación detrás del proceso de tomar una foto, debemos reconocer a fotógrafos como Salgado por mantener tanta verdad y transparencia como sea posible. Años después, Salgado dijo: “Serra Pelada is something that I’ll never see again in my life and I’ve been all over the planet. It’s been almost (40) years since I made (those) photos and I’ve been to more than 130 countries, but I only saw that strength, that power and that emotion at Serra Pelada” (Serra Pelada: 40 Years of Gold Fever

That Devastated the Amazon Jungle). La emoción extrema que emana de los ojos del sujeto en esta foto muestra la poderosa emoción que Salgado sintió en la mina. Creo que aunque las críticas a la fotografía pueden ser ciertas, es la culminación de todas las fotografías de esta serie lo que parece demostrar su autenticidad.

Bibliografía

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida, New York: Hill and Wang, 1982, 3-60. Kracauer, Siegfried. “Photography,” 245-267.

Nickelsberg, Robert.“Brazil: Gold Rush in Serra Pelada.” Red. Publicdelivery. “Sebastião Salgado’s Impressive Photos: This Was Brazil’s Largest & Most Dangerous Gold Mine.” Public Delivery, 17 June 2022. Red. Rhp. “The Hell of Serra Pelada Mines through Photographs, 1980s.” Rare Historical Photos, 10 Nov. 2021. Red.

Serra Pelada: 40 Years of Gold Fever That Devastated the Amazon Jungle. Red. Sontag, Susan. “In Plato’s Cave.” On Photography, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2005, 1-19.

Lorraine Olaya

Cumbia de mi nombre

El nombre mío es una mujer soltera que baila sola en medio de la pista, sus vestidos rozando el piso cuando los músicos ponen una cumbia vieja

ella llega todas las noches, los que trabajan ya la esperan, pero ella aparece diferente cada vez

Una vez, ella bailó en pareja y cuando llegó sola al día siguiente, casi no la reconocieron

Una vez, trató de cambiar sus vestidos largos por una falda pero eso no duró

Una vez, bailó con dos tacones sobre la cabeza

Otra vez, se transformó en tres lenguas

Pero ella siempre llega todas las noches

para que sus pies se posen suavemente sobre el piso como la lluvia que besa la tierra

Mi tambor

Tambor redondo y rotundo repica, retumba, repiquetea, cuando tintinea.

Tambor redondo y rotundo canta tan tan tan con tanta riqueza con tanta rapidez.

Tambor redondo y rotundo ríe su ruido tantarantán raspón desde el rincón.

Rugiente tambor, rataplán ruge tu rapsodia.

Entierra

nunca vi la palabra deletreada solo sentí sus letras en mi sangre las vi caer de los labios de mi madre y me las imaginaba en la página

si me envuelve en su tierra me enteraré de cómo enterrarme entera, para entregarme a la tierra en el entierro enterarse enterrarse

cómo el oído confunde dos letras por una, una palabra por otra

y cuando la escucho

todavía me entierro cuando me entero, en la tierra, debajo de las estrellas enteras.

When hablamos

Yo hablo in my lengua y you en la tuya. Together, hablamos like esto

por que not me didn’t get used to / And you no te acostumbró hablando in Spanish / speaking en inglés con you / with mi with tigo /con me.

Suena raro and sounds rare and sounds weird y suena extraño. Strange, stranger, estranged soy me am yo am i, i am soy yo, yo soy. Todo al back words backwards revés reverse.

And if I hablo Spanish me enredo with the palabras.

Y si you speak inglés tu tangles con las words.

Es chistoso, sometimes because nunca I liked el Spanglish.

But cuando we talk, hablamos Inspañol.

cross / currents ~ contra / corrientes

Dry Pedagogies/Wet Pedagogies

Laura Torres-Rodríguez“Bearing in mind the phenomenon of coastline erosion, which things (infrastructures, institutions, etc.) would you like to see eroded or battered by the water-edge?”

This was the prompt that researcher and curator Arnaldo Rodríguez-Bagué and visual artist Sofía Gallisá Muriente proposed to our students in preparation for their visit to our class. I have to say that the question stayed with me, but also with the students, as the works published in this dossier show, since the question not only captures the aesthetic and political reflections of these Puerto Rican artists after Hurricane María (2017), but also illustrates the type of pedagogical practices and reflections that emerged from the collective course “Cross-Currents Lab: Ocean as Myth and Method.” The course was team-taught in Spring 2022 by Luis Francia, Jordana Mendelson, Lee Xie, Emilie Tumale, Mariko Whitenack and I.

The question posed by the artists invited us to think about the political and creative agency of atmospheric events, to think with and through nonhuman agencies. We had read a concrete example for class that day of this type of speculative practice. In Edouard Glissant’s “The Black Beach,” the behavior of Le Diamant beach, its “system of relation,” generates a specific way of thinking in the philosopher. The coastal ecosystem works as a platform for the production of situated knowledge about Martinique that requires a methodological and conceptual shift. Glissant reflects on the failure of “those fantastic projects” to “ save the country” based on external and colonial models and forms of imagination (123). Inspired by the way in which the beach “organizes its economy,” its impermanence, and its chaos, Glissant proposes a different form of political action based on “an intense acuteness of thought, quick to change its heading,”(127) and, “to return to the sources of our culture and the mobility of their relational content, in order to have a better appreciation of this disorder and to modulate every action according to it” (125).

Likewise, the works and artistic trajectories of Sofía and Arnaldo invited us to think about water as an artistic medium—although this also implicated a painful reflection on its destructive capacities, on what we have lost to the water, and on the collective forms of mourning. For example, in her series Assimilate and Destroy (2018-2020), Sofía exposes celluloid, the very skin on which the visual memory of the 20th century has been inscribed, to elements such as salt,

humidity and mold. As the artist describes: “Assimilate & Destroy is a series that makes visible the forms in which climate conditions memory in the tropics, experimenting with biodeterioration processes on celluloid to register and accelerate the impermanence of images and the material evidence of history. The title refers to two processes that occur simultaneously during the decomposition of film due to humidity, considering their poetic and strategic implications in order to digest political processes.” Sofía asked us in class: what would need to be decomposed or destroyed in order for us to process a loss, change, or radical transformation? Or, going back to the initial question: what infrastructures and institutions do we have to let go of in order to decolonize?

Melody Jue, in her book Wild Blue Media: Thinking through Sea Water, proposes a similar reflection by asking how concepts hold up under conditions of oceanic submergence? (21)

“Underwater, any in-script-ions would be eroded, washed away, or overgrown with marine plants and animals” (28). This act of submerging concepts in water encourages us to rethink the very conditions in which we inscribe, store, or transmit information (29).

Of course, these readings made us think about our own pedagogical practices. How do we design a course that does not rely exclusively on what Jue calls “dry processes?” Can our dry classroom pedagogies really be inclusive? Here, the dialogue with different scholars and practitioners, almost all belonging to transoceanic and diasporic communities, was invaluable to help us create more immersive pedagogical practices. In the course, we had guest speakers from ocean science and physics with artists, writers, activists, actors, chefs, Indigenous studies scholars, and canoe builders. Claro de los Reyes, the founder and director of Atlantic Pacific Theatre, shared his teaching philosophy based on the creation of experiences with us. Most students retain information better through active participation. As Jue mentions about the way in which marine squids transmit information, they “make their impressions through memory rather than through marks on pages or stone” (30). In other words, they transmit information through different forms of theatricality. To put his philosophy in practice, Claro organized with us a theater workshop based on a participatory reenactment of the Filipino-American War. The participation helped us reflect and feel the ongoing effects of US imperialism in the Pacific, the Caribbean, and the city. Similarly, Vicente Díaz, another of our recurring visitors and a leading scholar in Comparative and Global Indigenous studies and the founder of The Native Canoe Project, gave other examples of immersed pedagogical and conceptual practices that occur in active interaction with the ocean’s ecosystems. For example, in “No Island is an Island,” Díaz analyzes how navigators from the Central Carolinas and Marianas use forms of ritualistic narrative

performance that, if sung properly, function as a non-paper mnemonic map of navigation, and are therefore invulnerable to damage by water. These songs sometimes announce the appearance of the destination island’s native fauna, flora, clouds, currents, smells, and waves. These traveling elements indigenous to a particular island “expand or contract” its circumference. In the navigation technique called etak, or “moving islands,” the position of a canoe traveling from one island to another can be calculated by triangulating the speed of the starting island and the destination island in relation to a third island that appears to be “on the move.” In these techniques and narrative acts, the canoe is conceptualized as “static” and the islands are mobile, expanding and contracting, and their temporal and spatial coordinates span the entire distance that their native creatures travel.

These are bodily practices and narrative acts that challenge the imperialist and scientific construction of the islands as isolated territories, available for occupation, instrumentalization or invisibilization, and doomed to extinction due to rising sea levels. Arnaldo, for example, has analyzed in his research what he calls forms of “archipelagic performance:” artistic practices that are produced, staged, and developed on the coastline, and that attempt to problematize sharp distinctions between land and sea. These performances also reactivate forms of affiliation and reciprocity with non-human or more-than-human marine life: “These responses counter-map the island’s futurity by going against the grain of Western environmental scientific discourses.” In the conversation with Sofía and Arnaldo, but also with Dantaé Elliott and Lee Xie about artist Nadia Huggins, and with Mariko’s class on Kanaka enviromental epistemologies and ontologies, a speculative reflection arose on the submerged futurities of the archipelagos, and on how to better perceive and grasp their pasts.

Díaz writes, “We need to learn how to feel and smell our cultural and political futures through a sniffing and feeling out of our pasts” (100). In “Stepping in it: How to Smell the Fullness of Indigenous Stories,” Díaz helps us reflect about the way education privileges sight and literacy, “the supposedly higher senses,” versus ways of learning that center our sense of smell, taste, and touch. One of our course objectives was to invite students to feel the city as an ecological and geographical archipelago where many migrant and island communities coexist. Even more, we tried to create pedagogical experiences, like our visit to the Billion Oyster Project, that could reflect on the indigenous and environmental histories of a city built on Lenape land and water. To be more attuned with our senses of smell, taste and touch could be a first step in the creation of a more reciprocal relationship with these lands and waters. In our visit to Governor Island, we were able to touch and smell the live oysters that the organization seeds

in the bay and visit the shell piles collected from different restaurants in the city. Oyster reefs are native to the New York Harbor and provided food and materials for the Lenape people that taught the settlers how to collect them (Liang). The Billion Oyster Project is an organization that seeks to put back one billion live oysters into New York Harbor. The project also allowed us to reflect on our city’s food chain from restaurants back into the harbor beyond the nature/culture divide.

The reflection about embodied forms of knowledge and memory was what inspired us to dedicate an entire unit to food and taste. Luis Francia and Emile Tumale invited chef and restaurant owner Amy Besa from Purple Yam, who talked about the colonial, imperial, and indigenous stories behind the transoceanic circulation of ingredients in Filipino cuisine and about her experiences researching and cooking rice heirloom varieties. Based on these discussions, students produced cookbooks, food poems and short fictions, and a video titled “Migratory Meal” documenting the process of cooking their traditional dishes together (Korean, Nigerian, Filipino, Chinese, Jewish) and the conversations they shared about imperialism while eating.

In one of our first meetings as a research group, Michael Salgarolo said that we could taste, feel, and see the material legacies of the Manila Galleons, the imperial and colonial maritime route that forcefully linked the Atlantic with the Pacific and the Caribbean and Pacific archipelagos, in the juxtaposition of different East and South Asian, Latin American, and Caribbean restaurants on Roosevelt Avenue in Queens. He also mentioned the irony in the name of the avenue—the politics of imperial naming. Above all, the Cross-Currents project allowed us to link global and historical processes to our city, but also to our personal histories and trajectories. Many of my conversations around the course with Luis Francia and Jordana Mendelson were about the long legacies of 1898 and pedagogical forms that could help interrupt the reactualization of those legacies in the present.

In January 2020, after the publication of my book, Orientaciones transpacíficas

[Transpacific Orientations], a book that talks about the Mexican cultural history of the 20th century from the Pacific, I was invited to participate in a panel titled “Puerto Rico and the Pacific.” As a Puerto Rican who writes about Mexico and the Asian Pacific, the call invited me to think for the first time about my own relationship with the research to which I had dedicated the last ten years. For that occasion, I decided to write about the Puerto Rican writer Manuel Ramos Otero’s short story collection Página en blanco y staccato (1987), which he wrote while living in NYC during the AIDS crisis. I argued that the five short stories of the book explore the deep histories of 1898 through a literary speculation on the transpacific aspect of Puerto Rican history.

As the Cross-Currents project did for me, the book’s skill lies precisely in observing (events and oneself) from the Asian-Pacific region and its history, which deploys a different field of visibility and contention. In Ramos Otero’s narrative, the Puerto Rican connection to the Pacific is not necessarily understood as an alternative spatial cartography but rather as a relation that can only be grasped temporarily. 1898 gets fictionalized as a kind of temporal seismic fault line whose reverberations destabilize all notions of progressive linearity in the events, and where different temporal and narrative modalities are exhibited. In this book, Ramos Otero proposes that it is through storytelling and different narrative acts that Puerto Rico’s history can be explored from the improper terrain of the Pacific, and seeks to produce visibility for instances of transpacific memory. For example, one of the short stories is a letter of a Puerto Rican agricultural worker in Hawaii, another is a detective story about an Afro-Chinese Puerto Rican character that murders his white criollo narrator to avenge the execution of his formerly enslaved ancestor. Hence, the writer problematizes both nationalist and imperialist productions of discrete, differentiated geographies, [The Caribbean or the Pacific], to propose a “we” that is always in dispute, and which is only located within the modifiable temporality of the narrative. It is in this sense that the Cross-Currents project was, above all, an exercise in collective storytelling.

Bibliography

Díaz, Vicente. “No Island is an Island” Native Studies Key Words. Eds Michelle H. Raheja, Andrea Smith, Stephanie N. Teves. University of Arizona, 2015. 90-108.

____. “Stepping In It: How to Smell the Fullness of Indigenous Histories.” Sources and Methods in Indigenous Studies. Ed. Chris Andersen and Jean M. O’Brien. Routledge, 2017. 88-92.

Gallisá Muriente, Sofía. “Asimilar y destruir”, https://sofiagallisa.com/Asimilar-y-Destruir-1. Glissant, Édouard. Poetics of Relation. Trans. Betsy Wing. University of Michigan P, 1997.

Jue, Melody. Wild Blue Media. Thinking Through Sea Water. Duke UP, 2020.

Liang, Wenjun “The Oysters of New York Past,” May 21, 2021.

Ramos Otero, Manuel. Página en blanco y staccato. Editorial Plaza Mayor, 2002.

Rodríguez Bagué, Arnaldo. “Archipelagic Performance #1 (v.1)” Matorral.

Nadia Huggins Offshore Imaginations

Offshore Imaginations, a selection of photographs by artist Nadia Huggins for Esferas, invites the viewer to imagine forms of vision, experience and corporeal thought through three different series: Transformations, Circa no Future, and Disappearing People. Nadia Huggins documents her personal experience by “developing a map of what it means to be human in certain parts of the world.” What possibilities of being, and being in space become available when we situate our bodies in the water? What challenges become visible? What forms of understanding of ourselves and others appear?

Circa No Future

Believing there to be a link between an under-explored aspect of Caribbean adolescent masculinity and the freedom of bodies in the ocean, I set out to document boys’ interaction with the sea. Created since 2014, these photographs capture manhood, snippets of vulnerability and moments of abstraction that often go unrecognized in the day-to-day. The ocean itself takes on a personality—that of the embracing mother providing a safe space for being—which is both archetypal and poignant. The boys climb a large rock, proving their manhood through endurance, fearlessly jump, and become submerged in a moment of innocent unawareness. They emerge having proven themselves. The relationship between the boys and me is also explored within this paradigm. They are aware of me while posturing, but lose self-awareness when they sink into the water.

Transformations is a series of diptychs that explores the relationship between my identity and the marine ecosystem.

During my daily swim, I became preoccupied with the changes I saw happening before me with the deterioration of coral reefs that were once alive. At the same time, I was finding solace through the amorphous quality and weightlessness of my body in the water. I decided to take my camera into the water to document the interplay between the seascape and my body.

I created these transfigured portraits by using collage techniques to bring together selfportraiture and my documentation of marine organisms. Each portrait brings together two separate entities: the body and various marine animals. By juxtaposing these images with a space in between them, each portrait is on the cusp of becoming a single image. This space represents a transient moment where I am regaining buoyancy and separating from the underwater environment to resurface. My intention with these photographs is to create a lasting breath that defies human limitation. The transformation exists within the space in between photographs. It is in this moment that the viewer makes the decision if both worlds are able to separate or merge.

Dissappearing People

Transformations

Transformations

Transformations

Transformations

The First Object Which Saluted My Eyes Was

the Sea (And the Slave Ship)

Hannah SiegelThe first object which saluted my eyes was the sea

. They are dining in front of me, every evening with those queer industrial lights and iron chairs

a raucous circus of delights

PART I: THE FALL

and a slave ship

I have never understood these new people.

And their obsession with light even over water.

(lights over the water)

But they tell me I am bronze, now.

It is a warm summer day the kind my Sarah loves

My brow seethes radiating

iron-hot rays

I’d burn these new revelers to the touch.

Perhaps the growing crowd is here to feast as well but on what I am not sure they look unlike revelers unlike a summer stroll much more like the waves to my right.

There are so many of them. I am being grabbed.

one of them held me fast by the hands and laid me across I think the windlass, and tied my feet

I am being bound.

I had never experienced anything of this kind before; and although, not being used to the water, I naturally feared that element the first time

I am being struck from my plinth.

I was now persuaded that I had gotten into a world of bad spirits, and that they were going to kill me.

The sea glistens below me and I— I am falling into the open mouth of it.

The first object which saluted my eyes was the sea (and the slave ship).

PART II: THE DROWNING

somehow made through the nettings and jumped into the sea such noise and confusion

. I am far from Bristol now. I do not know how long I have been here I have been drifting a long while now.

light is eating through my forehead

I’m turning blue

I things have embedded themselves inside me upon me in my clothes and hair

last week a shell crawled out of my nose spindly legs and phosphorescence the salt is bleeding me of my eyes it’s eating me

somehow I can feel it I can

but my mass is still solid. my body is unbroken here.

It is very cold, here and I can feel the currents mixing nitrogen rich

oxygen from the east warm and calcifying spirals from the west I feel I— feel as if I’m at the center of the world

There has not been light for a very long time.

I saw the bronze man when he arrived in our waters // It was summertime then / we were swarming // as we always do / some into the mouths of the great beasts /// below us / as some of us /// always are /

I rested with my brothers and sisters / for a time / in the tragus of his ear // blue antlers feeling, feeling /// for what may rest inside / we found nothing terribly interesting /// not there nor on his left knee / nor his iris ///

so terribly different from ours / we found nothing interesting there either1

PART III: THE SURFACING

1.. I saw the bronze man when he arrived in our waters // It was summertime then / we were swarming // as we always do / some into the mouths of the great beasts /// below us / as some of us /// always are /

I rested with my brothers and sisters / for a time / in the tragus of his ear // blue antlers feeling, feeling /// for what may rest inside / we found nothing terribly interesting /// not there nor on his left knee / nor his iris ///

so terribly different from ours / we found nothing interesting there either.

“HELLO!” chimes a voice, slightly garbled by the water, bubbles emerging from nowhere.

“Hello?” I scream, mouth half full of refuse and mercury.

“Where am I?” I beg.

“GOWANUS,” pierces the waves, in that same voice: booming and sickly-sweet.

“What?”

“GOWANUS CANAL. IN BROOKLYN. NEW YORK?” she prods, lifting an eyebrow.

“New York? I’ve—I’ve crossed the sea?”

“YES.”

“The colonies?”

“NO. THERE ARE NO COLONIES ANYMORE.” There is nothing anymore, I think. I’m still drowning. I’m hardly a part of this world.

“I’m standing up,” I cry, disbelieving. It’s bizarre, a strange orientation that’s been making me dizzy for days. I don’t remember it. This isn’t like the deep. Not like before, when the pressure sank into my bones and popped the rings on my fingers like carnations, flesh turned inside out.

“YES,” she answers. “THERE IS ONLY 6.37 FEET OF SEDIMENT BELOW YOU.”

“The ground?” I ask.

“NOT QUITE. YOU ARE STILL IN THE SEA.”

“Why—why are you here? What are you?” She appears to me, then, standing on a concrete ledge. What’s left of my right eye can see acres and acres of cardboard, stacked like children’s toys. Red. Yellow. Blue. I had forgotten those.

“I THOUGHT WE MIGHT SPEAK HERE.” The boxes’ squareness frightens me. “I AM A BARRISTER.” She is dressed in that strange new fashion. The one I remember from the plinth. She is tall, brown-skinned, wearing, yes I see it now—wearing a barrister’s wig. Tucked beneath it are curtains of long, brown braids. They seem to fall everywhere.

“YOU’VE BEEN SERVED,” she voices. Her arm is outstretched. Papers, I remember. Papers

“I can’t read them,” I gasp, the tide spilling into my nose again. Everything dissolves here.

“I KNOW,” she responds, my world becoming dishwater gray. “THAT’S WHY I’M HERE.”

“What’s—“ the tide washes into my mouth again. “What’s the case?” Her eyebrows knit together.

“THE LARGEST LONG-DISTANCE FORCED MOVEMENT OF PEOPLE IN RECORDED HISTORY.” Hope scrabbles up my neck.

“Am I—” I ask desperately, the crown of my head emerging from the water, “—part of it?”

“YES.”

“Am I—” the tide oscillates, “—to be saved?”

“NO.” Gravity beats on me. “YOU ARE BEING CHARGED.”

“What, what movement then?”

“THE FIFTEEN MILLION.” I cannot even conceive of a number so high. Are there so many people on this Earth? In New London, perhaps?

“Who moved them?”

“YOU DID.”

“Wha—“ I am cut off by the barrister’s echoing voice, vibrating each drop of brackish water with its sound. She does not wait for me to answer.

“EDWARD COLSTON, BORN SECOND NOVEMBER 1636, SEA MERCHANT TRADING IN TEXTILES. SENIOR EXECUTIVE OF THE ROYAL AFRICAN COMPANY, MONOPOLY OF ENGLISH SLAVES.”

None of it is a question.

“CHARGE: ESTIMATED 187,133 ENSLAVED PEOPLE.”

Yes but of course I did what e—“ my mouth is full of water again. I believe the barrister is smiling. It is a long time before the sediment reshuffles, and I can breathe again. A ship is coming in.

“YOU HAVE AN OPPORTUNITY. A DEFENSE.”

“Yes!” I scream. “Whatever it is, I—I plead, I assent!” The barrister stands tall, her velvet robes unmoving in the shadows.

“A PERSON, she begins, “IS TO BE TREATED AS HAVING A LAWFUL EXCUSE IF THEY HONESTLY BELIEVED, AT THE TIME OF THE ACTS, THAT THOSE WHO THE PERSON HONESTLY BELIEVED WERE ENTITLED TO CONSENT TO THE DAMAGE, WOULD HAVE CONSENTED TO IT.

“IF,” she warns, “THEY HAD KNOWN OF THE DAMAGE. AND ITS CIRCUMSTANCES.”

“What people?” I beg.

The barrister’s papers burst from her hands, falling on the water’s surface like a dusting of snow. No, I think cruelly. Like ash. Like flakes of led from a train platform, dissolving on impact.

“THE DEFENSE,” she speaks plainly, “DOES NOT APPLY.” She repeats it, as if she has repeated it many times.

“No!” I can feel the tide shifting again.

“Wait! Wait, I beg of you!” I cannot now tell what is refuse and what is my tears.

“Why am I still here? Why—why am I alive?” She pauses, head tilted slightly. I can see her large tortoiseshell glasses glisten in the dying afternoon sun. Her lips purse. The voice that spills from them is entirely different.

“BRONZE, UNLIKE BRASS, CONTAINS LITTLE OR NO ZINC AND IS THEREFORE IDEALLY SUITED TO SEAWATER APPLICATIONS.”

She is gone before I can breathe again, and I can hear a horn blow in the distance, tickling the strands of rope still tied around me.

PART IV: SUBMERSION

coral glistening

network of reeds a mangrove tree’s minnow

a dead man’s float

brackish

all my eyelashes fell out big storm

bigger

pink now

lightning rods

oak and maple

alive in the water

so many strings

puppeteering

sugarcane

stalks of rhubarb

no more feet

torso. substrate

several oysters

bad water again

this time

leaking this time rotting

the water isn’t safe anymore

half of me in the Antilles

new breeding ground

small insects swarming smaller than me

all spelling death

they taste like fishing rods

head

bobbing against

porous rock

last bit of my noble head scratch in it.

I now wished for the last friend, death, to relieve me hardships which are inseparable from this accursed trade.

Notes:

1. Each of the italicized lines in Part I, II, and IV are edited excerpts from the autobiography of Olaudah Equiano, an enslaved African person and survivor of the TransAtlantic slave trade. I selected these lines from the passage provided—interestingly—by the UK website PortCITIES, dedicated to the history of Bristol and other ports in Britain. All of the text I selected pertains to Equiano’s capture into slavery and his experiences during the Middle Passage (“Personal Account”).

2. The ‘queer’ dining establishment that Colston sees in Bristol is Pitcher & the Piano, a real restaurant in Bristol which can be seen in the viral videos of protestors toppling the Colston statue and throwing it into the water (“Pitcher & Piano”).

3. Information about Colston’s life is drawn from the African American Registry’s Biography (“Edward Colston”).

4. The place where Colston drowns in Part II, where he “feel[s] as if I’m at the center of the world” is meant to be Beringia, as termed by Bathseba Demuth in Floating Coast (9, 14, and 25).

5. The “flakes of led” Colston imagines in Part III are in fact, the real “refuse” entering his mouth. They are flakes of led which continue to fall from the MTA 7 train in Brooklyn (O’Hara).

6. Gowanus Canal is infamously polluted. It contains, at best estimate, between one and twenty feet of contaminated sediment at any given time, with an average of 10 feet (United States Environmental Protection Agency, 15). My estimate of “6.77” feet comes from these figures.

7. The phrase “The largest long-distance forced movement of people in recorded history” is appropriated from the Lowcountry Digital History Initiative’s summary article on the TransAtlantic slave trade (“The Trans-Atlantic”).

8. Colston’s “charge” of the transportation of “187, 333” enslaved people is derived from the Slave Voyages historical database. This is the total “captives embarked” with “Royal African

Company” populated as the owner of the ship (“Summary Statistics”). It represents a strong estimate of how many enslaved persons were kidnapped by the Royal African Company during its tenure.

9. The ‘defense’ the Barrister offers Colston is appropriated, with small edits, from the legal directions given to the jury by the Recorder of Bristol, HHJ Peter Blair QC in the legal case R v Milo Ponsford, Sage Willoughby, Rhian Graham, and Jake Skuse. These four, also dubbed “The Colston Four” are the protestors charged with and found not guilty of property damage when they removed, defaced, and overthrew Bristol’s statue of Edward Colston (Matthew).

10. The Barrister’s explanation for why Colston is still “alive” is appropriated from Steve D’Antonio’s Marine Consulting Inc.’s article on underwater alloys (D’Antonio).

11. The references to Colston turning “blue” and “pink” as well as being eaten away are all allusions to bronze disease (“Archaeologies of Greek Past”).

12. The second, third, and fourth stanzas of Part IV depict Colston in a post-hurricane Puerto Rico and a post-climate apocalypse ocean.

13. The final resting place which Edward Colston stumbles upon in Part IV is in fact the interior chamber of the Runit Dome. The “small insects” are radioactive particles.

Bibliography

“Archaeologies of the Greek Past: Bronze Disease.” Joukowsy Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World. Web.

“British Protesters Topple Edward Colston.” YouTube, uploaded by Washington Post, 7 June 2020. Web.

Demuth, Bathsheba. Floating Coast: An Environmental History of the Bering Strait. W.W. Norton, 2019.

“Edward Colston, Slave Trader Born.” African American Registry. Web.

Matthew. “Colston Summing Up: Those Legal Directions in Full.” BarristerBlogger, 9 January 2022. Web.

O’Hara, Andres. “MTA Plans to Clear Dangerous Lead Paint From 7 Line After Years of Neglect.” Gothamist, 20 June 2018. Web.

“Personal Account of an Enslaved African.” PORTCITIES Bristol. Web.

“Pitcher & Piano.” Web.

Steve D’Antonio. “Brass v. Bronze; Know Your Underwater Alloys—Editorial: Boat Show Season is Upon Us Once More.” Steve D’Antonio Marine Consulting, Inc., 7 October 2015. Web.

“Summary Statistics.” Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade: Database, Slave Voyages. Web.

“The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade.” Lowcountry Digital History Initiative, African Passages, Lowcountry Adaptations. Web.

United States Environmental Protection Agency Region II, New York, New York. “Record of Decision: Gowanus Canal Superfund Site Brooklyn Kings County, New York.”

September 2013. Web.

A Critical Foreword and Author’s Notes:

This piece was originally published as a final project submission for SCA-UA 380: Cross/ Currents Lab: Ocean as Myth and Method. It is a mini-collection of poetry and flash fiction, separated into four acts. It was inspired by Nadia Huggins’ Circa no Future series, particularly one shot, in which the subject appears like a bronze statue—arms flung wide, glistening against the sun. This image struck me as a counterpoint to the effigy of Edward Colston, a bronze statue of a colonial-era slave trader which was flung into the Bristol Harbor by activists in June of 2020 (McGreevy). In Huggins’ series, a young Black boy is enshrined, statuesque, against the salt and sea of Saint Vincent & the Grenadines. In 2020 Bristol, a white slave trader’s image is toppled into the waves with rage. My series explores Colston’s fate if his statue was never fished out of the harbor. The title, as well as the closing words of the collection, come from the autobiography of Olaudah Equiano, an enslaved African who survived the Middle Passage and subsequently published his memoirs. The piece is designed to place colonial victors in direct confrontation with their victims: the enslaved.

My series condemns Colston to a Prometheus-like fate, drowning continually in various sections of the deep. His metal body becomes fodder for clusters of oysters, shrimp, and algae; he settles at the bottom of the straits of Beringia; his head bumps against the interior of the infamous Runit Dome. Colston is buffeted by the cross-currents of colonialism, environmental ruin, biodiversity, and capitalism, each melding and mixing in the ocean’s waters. Like the figures in Huggins photography, my work explores the liminal—the blurring that occurs when salt, sea, and light dominate perspective. Critically, I borrow from Melody Jue’s notion of water-asmilieu. As she advocates in “Thinking Through Seawater,” the sea is one of the many milieus in which the scholar (and, indeed, consciousness) operates (2). Dominated by different qualities of pressure, light, salinity, and a world of organic creatures, a submerged orientation is entirely different from a terrestrial one (10). What happens to the colonial legacy when we soak it? What might shrimp—with their many-color-seeing eyes—think of Colston’s bronze head (Jue 10)? In Part II, I incorporate this perspective in an intentionally illegible dingbat font. It is translated in a footnote. Further, given that Hi’ilei Julia Hobart advocates that “[art] ask us to bear witness to sinking, shifting, and melting worlds,” I seek to thrust the agents of the colonial project, and their enshrined simulcra into the waters which their violence have fed. Why shouldn’t Colston— a colonial slave trader—be fated to drown in the storm surge swallowing up the Lower East

Side, the Marshall Islands, or Jamaica? After all, Grayson Chong reminds us that “[w]aste is a remainder, a remnant of history, a ruin, and might be understood as an unintended archive” (9). What happens if, or when, the vestiges of the colonial project are cast off this society as refuse? What will that refuse see or hear, and what will the ocean—perhaps the ultimate archive—make of it?

Further, I hope my piece raises questions of how punitive justice, as opposed to restorative justice, forces a remnant of violence to persist. One frustration I confronted while writing this piece was the need to keep Colston’s body and mind in tactic, if only for the purposes of further torture. This approach elided an abolitionist one that could have gotten rid of him altogether. It did not allow for a focus on the rejuvenation and joy of once-colonized peoples. In order for revenge against colonial figures to persist, the colonial figure must remain also. I do not mistrust or seek to disparage a rightful rage; however, I would like to put pressure on the narrative mode I chose—that of eternal punishment. Finally, I extend my deepest thanks to Professor Laura Torres-Rodriguez, who encouraged me to submit to Esferas and served as a wonderful mentor. I would also like to thank each of my Cross/Currents instructors, who were endlessly encouraging and top-tier educators. Without their critical foundation, this miniature work would never have sprung into being. Thank you to Professors Luis Francia and Jordana Mendelson, as well as Lee Xie.

Bibliography

Chong, Grayson. “Hurricanes and Headpieces: Storytelling from the Ruins and Remains in Caribbean History and Culture.” Comparative Media Arts Journal, 2021. Web.

Hobart, Julia Hi’lei. “Atomic Histories and Elemental Futures Across Indigenous Waters.” Media + Environment, vol. 3, no. 1, 2021. Web.

Huggins, Nadia. Circa no Future. 2011. Web.

Jue, Melody. Wild Blue Media: Thinking Through Seawater, Duke University Press, 2020. ProQuest Ebook Central. Web.

McGreevy, Nora. “Toppled Statue of British Slave Trader Goes on View at Bristol Museum.”

7 June 2021, Smithsonian Magazine. Web.

Oceanic Decolonial Ruination

Arnaldo Rodríguez-Bagué

The passing of Hurricane María in September 2017 across the Puerto Rican archipelago has re-centered natural disasters across Puerto Rican political thought’s decolonial discursive fields. Although natural disasters are a fundamental part of Caribbean long anti-colonial histories, Caribbean political thought’s recentering of Hurricane María across its discursive fields have left natural disasters’ geophysical forces out of decolonial critique. One example of this is the book edited by Puerto Rican scholars Yarimar Bonilla and Marisol Lebrón titled Aftershocks of Disaster: Puerto Rico Before and After the Storm (2019). In the book’s introduction, titled Introduction: Aftershocks of Disaster, Bonilla and Lebrón “examine both Hurricane María’s aftershocks and its foreshocks” to propose a “coloniality of disaster” that seeks to articulate “the way the structures and enduring legacies of colonialism set the stage for Hurricane María’s impact and its aftermath” (Bonilla and Lebrón 3, 11). In the book’s afterward, titled Critique and Decoloniality in the Face of Crisis, Disaster, and Catastrophe, Puerto Rican philosopher Nelson Maldonado-Torres probes Hurricane María’s colonial staging by engaging with terms such as “crisis, disaster, and catastrophe” as a way to “obtain a more precise sense of the extent and depth of various forms of devastation and destruction, as well as of different ways of responding to them” (Maldonado-Torres 332). As he argues, “one of the ways of responding to events such as Hurricane María is critique” (Maldonado-Torres 332). For MaldonadoTorres, responding to natural disaster from “critique is important because it indicates a shift from considering a crisis, disaster, and catastrophe as a natural event to approaching it instead as connected to human intervention or sociohistorical forces” (Maldonado-Torres 332). That is, “understanding and explaining colonialism’s sociohistorical forces requires the consideration of ideologies, attitudes, and social, economic, and political systems, among other factors” (Maldonado-Torres 333).

The Caribbean decolonial thought that emerged in response to Hurricane María’s devastating impact on Puerto Rico’s colonial territory clearly privileges the social, economic, and political forces animating the hurricane’s deadly aftermath. Natural events’ geophysical forces don’t seem to make a meaningful critical impact in analyzing such a natural-colonial catastrophe. Maldonado-Torres’ sociohistorical articulation of ‘critique’ as a critique that shifts away from considering “a crisis, disaster, and catastrophe as a natural event” leaves out any possibility of

politicizing the geophysical forces that animate not only any natural disaster but the Caribbean’s colonial natural history within Caribbean political thought’s discursive fields (Maldonado-Torres 332). Concealing a natural disaster’s geophysical dimension as something incommensurable to the analysis of a natural disaster’s sociopolitical aftermath wouldn’t necessarily allow neither for a “more precise sense of the extent and depth of various forms of devastation and destruction” nor for the elucubration of various forms of decolonial critiques (Maldonado-Torres 332). The ideologies surrounding contemporary Caribbean decolonial thought’s critical engagement with Hurricane María separate Puerto Rico’s colonized tropical nature from the social, the political, the economic, and, surprisingly, from Caribbean decolonial thought itself. What can be argued about natural disasters such as Hurricane María is that they put contemporary Caribbean decolonial thought into crisis. Having said this, how can we approach Hurricane María’s aftershocks of disasters without separating the Caribbean’s tropical nature from Puerto Rico’s colonial culture?

As a way of rehearsing an engagement with a natural disaster’s aftermath without denaturalizing Caribbean decolonial thought, this essay will approach Bonilla and Lebrón’s notion of “aftershocks of disaster” from an oceanic perspective. While Bonilla and Lebrón articulate a “coloniality of disaster” by making use of geological metaphors such as aftershocks and foreshocks as analytical categories to critically engage with the multiple temporalities of Hurricane María’s sociopolitical aftermath, I will be reading two of Hurricane María’s oceanic aftershocks enacted across the colonial coastlines of the Puerto Rican archipelago. These two oceanic aftershocks, a storm surge and a feminist performance, function as an oceanic form of critique to Puerto Rican and the Caribbean’s deep colonialism. They allow us the possibility of not only reconsidering the political effects of natural events’ geophysical forces as morethan-human interventions to the Caribbean’s colonial built environment, but they also allow us to speculate on Caribbean decolonial futures’ multiple temporalities. For this, I’ll approach Hurricane María’s oceanic aftershocks from what Maldonado-Torres refers to as “countercatastrophic thought and creative work” (Maldonado Torres 340). I’ll also add speculative imaginary that enables Puerto Ricans islanders to “explorations of time and the formations of space, within, against, and outside the modern/colonial world” while also revealing the various layers of catastrophe (Maldonado Torres 340).

In the context of this essay, engaging with Hurricane María’s oceanic aftershocks—as a counter-catastrophic thought, practice, and speculative imaginary in a geohistorical moment inflected by climate change means—extends Caribbean’s tidalectic geopoetics towards Caribbean

islanders’ forced intimacy with the geo-material effects of coastal erosion on the coastlines of Caribbean islands. Speculating on Caribbean decolonial futurities from Caribbean islanders’ forced intimacy with the effects of these oceanic forces means more than responding, repairing, and/or reconstructing what was lost in the wake of Hurricane María. It means being critical of what was left intact on the archipelago’s colonial geography, infrastructure, and colonial built environment and that is left to be eroded, ruined, destroyed, and submerged below the Atlantic Oceanic as part of Puerto Rico recovery efforts.

Oceanic Aftershock #1

On March 5, 2018, six months after Hurricane María, a storm surge came about Puerto Rico’s north coast causing certain havoc. Of all the destruction caused on the archipelago’s northern coast, the Puerto Rican media focused on the storm surge’s partial destruction of one of Old San Juan Isle National Historic Site’s most iconic promenades: El Paseo de La Princesa. Located in the isle’s southeastern coast, El Paseo de La Princesa was built in 1853 by Puerto Rico’s Spanish military colonial governor Fernando Norzagaray y Escudero to commemorate the 19th century Spanish monarchy in Old San Juan’s colonially and militarily built environment. Before the promenade was built, La Princesa was a prison built in 1837 and remained open until 1965. In this prison, the leader of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party, Don Pedro Albizu Campos, was jailed and tortured. Ironically, in 1989 La Princesa Prison became, up until today, Puerto Rico’s Tourism Company’s headquarters.

The partial destruction of the promenade’s handrails, lighting infrastructure, and colonial moldings were not caused by a massive natural disaster like Hurricane María but rather by one of its oceanic aftershocks—an ordinary storm surge. Thinking with this storm surge’s erosive effects on El Paseo de La Princesa as an oceanic critique to Puerto Rico’s deep colonialism implies understanding the storm surge’s ruinous oceanic gesture to Old San Juan Isle’s colonial built environment to what I’ll refer to as oceanic decolonial ruination. Based on the American anthropologist Ann Laura Stoler’s articulation of “ruination” in her essay titled Imperial Debris: On Ruins and Ruination (2013), an oceanic decolonial ruination is a series of ongoing, corrosive, violent, but vibrantly subtle acts, gestures, events, and processes of bringing ruin upon European and American imperial formations on the Puerto Rican archipelago and the Caribbean Americas. The Atlantic Ocean’s ruination of El Paseo de la Princesa inflicts slow and partial but sudden and irretrievable disaster upon the future of the political life of Western colonially and militarilybuilt environment across the Caribbean Americas. I don’t choose to analyze this storm surge

as an oceanic aftershock out of a critical whim. Natural events such as this storm surge are remembered and become politicized by artists after Hurricane María’s aftermath. Such is the case for the second oceanic aftershock: Teresa Hernández’s ongoing performance research project titled Bravata y otras prácticas erosivas (Bravata and other erosive practices, 2019-ongoing).