Geologic Investigations for Compliance with the CARB Asbestos ATCM BRADLEY G. ERSKINE* Erskine Environmental Consulting, Inc., 401 Marina Place, Benicia, CA 94510

Key Terms: ATCM, NOA, Ultramafic Rocks, CARB, Franciscan Complex ABSTRACT The California Air Resources Board Airborne Toxic Control Measure for Construction, Grading, Quarrying, and Surface Mining Operations (ATCM) provides requirements for the evaluation for naturally occurring asbestos (NOA) on a construction site. There are two compliance triggers: (1) a determination that the site is located within a geographic ultramafic rock unit, defined as a geographic area designated as an ultramafic rock on referenced maps, and (2) the presence of NOA, serpentinite, or ultramafic rock. The California Geological Survey requires that NOA evaluations be conducted by a licensed professional geologist. However, under the ATCM, a professional geologist is required only when a property owner wishes to demonstrate that a geographic ultramafic rock unit is not actually represented by ultramafic rocks. The professional geologist who must advise whether the ATCM applies at a construction site is therefore placed in a precarious position. Does a limited desktop review of geologic maps meet any standard of practice? If the ATCM is triggered by the presence of asbestos, is the geologist negligent if no evaluation is recommended or conducted? Could geologic units be pre-screened for asbestos potential? Using case studies and geologic data in the city of San Francisco and East Bay, this presentation reviews these issues and provides a context for the geologist to conduct the appropriate level of investigation for compliance with the ATCM. INTRODUCTION California geology is exceedingly complex and among the most diverse in the world. Igneous crystallization and metamorphic mineralization processes, combined with past and present tectonic activity, have produced a diverse range of rocks and minerals, many of which are or were economically significant. Gold in the Sierra Nevada foothills, rare earth elements near Mountain Pass, and tourmaline in the Pala District east of San Diego are but a few examples. *Corresponding author email: Erskine.geo@gmail.com

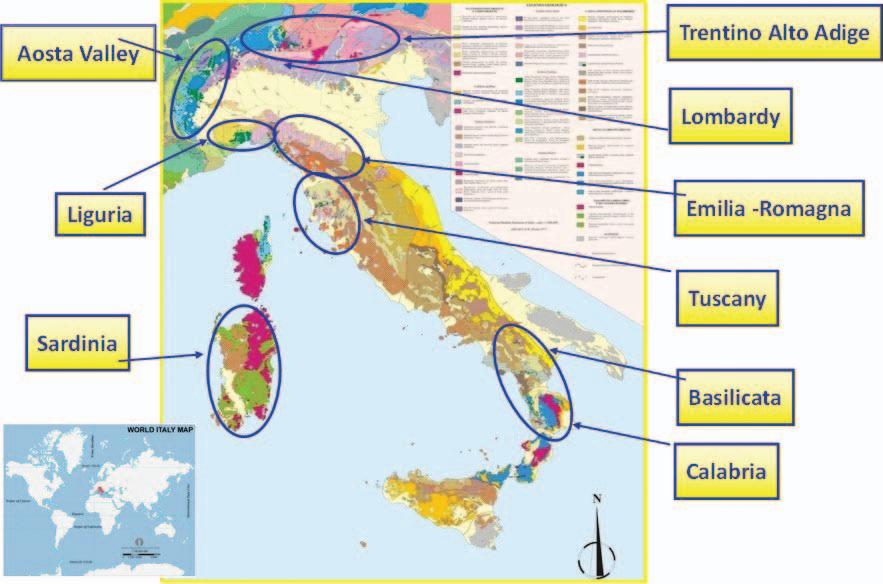

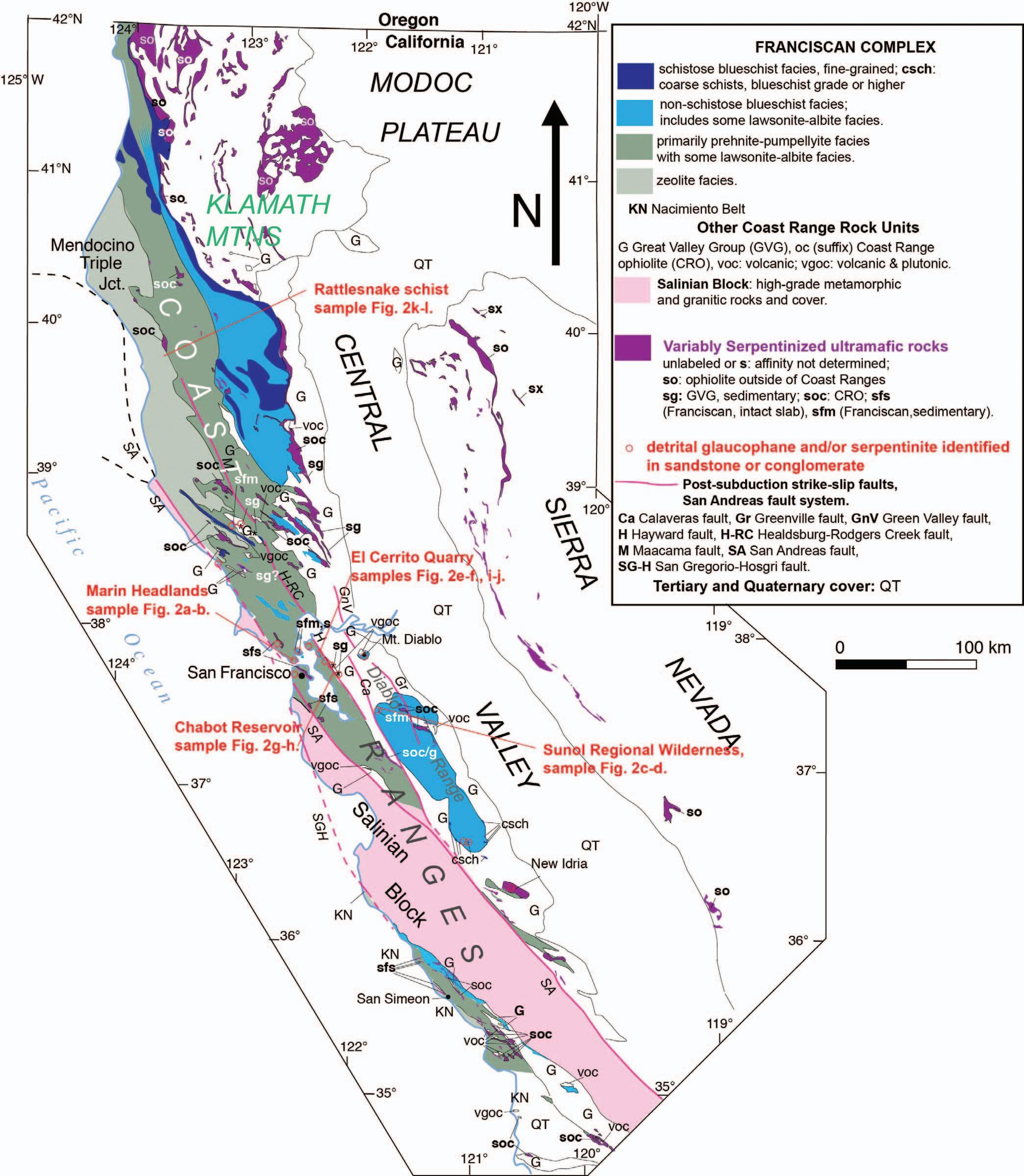

Asbestos, primarily chrysotile, was one economically important mineral that was mined for its use in building materials. The KCAC mine in the Coalinga District was once the largest asbestos mine in the world and was the last asbestos mining operation in the United States when it closed in 2002. To illustrate how common asbestos is in California, consider that chrysotile is a ubiquitous component of serpentinite, the California state rock. Serpentinite is exposed in the Sierra Nevada foothills and in a western belt that extends from the Klamath Mountains to as far south as Santa Barbara. Based on several studies by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the U.S. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), notably the Clear Creek Management Area near Coalinga (U.S. EPA, 2008) and the El Dorado Hills exposure studies (U.S. ATSDR, 2011), California implemented the nation’s most developed regulations and guidance documents to mitigate the potential exposure to asbestos on construction sites. An example (and the subject of this article) is the California Air Resources Board (CARB) asbestos Airborne Toxic Control Measure for Construction, Grading, Quarrying, and Surface Mining Operations (ATCM), which provides requirements for the evaluation of naturally occurring asbestos (NOA) on earth-disturbing construction sites (CARB, 2002). When the ATCM is triggered via criterion listed in Section (b)—Applicability, mandatory asbestos-specific dust control measures are required by CARB, and perimeter air monitoring may be required at the discretion of the regional Air Pollution Control District. The two relevant compliance criteria specified in the Applicability section are the following: Subsection (b)(1): “Any portion of the area to be disturbed is located in a Geographic Ultramafic Rock Unit”; or Subsection (b)(2): “Any portion of the area to be disturbed has naturally-occurring asbestos, serpentine, or ultramafic rock.”

The criterion in subsection (b)(1) refers to a “Geographic Ultramafic Rock Unit,” defined in the ATCM as follows:

Environmental & Engineering Geoscience, Vol. XXVI, No. 1, February 2020, pp. 99–106

99