HOMENAJE A

EL

GRECO

Sofía Gandarias

Edición a cargo de la Fundación Yehudi Menuhin España http://fundacionyehudimenuhin.org/ © De los textos: sus autores © De los cuadros: Legado Gandarias © Imagen cubierta: detalle de “La caballero Audrey Hepburn” (2015) Creación y realización: Infinito Estudio ISBN: 978-84-948810-5-3 Depósito Legal: BA-000542-2018 Imprime: Gráficas Romero - CÁCERES Infinito Estudio, S.L. - 2018 Vegas Bajas, 14 06490 Puebla de la Calzada - BADAJOZ www.infinitoestudio.com No se permite la reproducción total o parcial de este libro, ni su incorporación a un sistema informático, ni su transmisión en cualquier forma o por cualquier medio, sea éste electrónico, mecánico, por fotocopia, por grabación u otros medios, sin el permiso previo y por escrito del editor. La infracción de los derechos mencionados puede ser constitutiva de delito contra la propiedad intelectual (Art. 270 y siguientes del Código Penal).

Impreso en España

HOMENAJE A

EL

GRECO

Sofía Gandarias Yehudi Menuhin / Simone Veil / Augusto Roa Bastos José Saramago / Esther Bendahan / Carlos Fuentes / Sami Naïr Mercedes Monmany / Guillermo Solana / Gregorio Marañón Mª Jesús Iglesias / Adolfo García Ortega / Gianni Vattimo Nativel Preciado / Jordi Mercader Miró / Federico Mayor Zaragoza Víctor Ullate / Enrique Vila-Matas / Candela Álvarez Soldevilla Concha Gutiérrez / Juan Cruz / Eduardo de Santis José García Nieto / José García Abad / Anabel Domínguez

TEXTOS / TEXTS

ÍN DI CE

Presentación

11

Acerca de Sofía Yehudi Menuhin Simone Veil Augusto Roa Bastos José Saramago Esther Bendahan Carlos Fuentes Sami Naïr Mercedes Monmany Guillermo Solana Gregorio Marañón Mª Jesús Iglesias Adolfo García Ortega Gianni Vattimo Nativel Preciado Jordi Mercader Miró Federico Mayor Zaragoza Víctor Ullate Enrique Vilà-Matas Candela Álvarez Soldevilla Concha Gutiérrez Juan Cruz Eduardo de Santis José García Nieto José García Abad Anabel Domínguez Agradecimientos

13 21 23 25 37 41 45 51 55 59 63 73 79 85 93 97 101 103 107 111 117 119 125 127 129 133 139

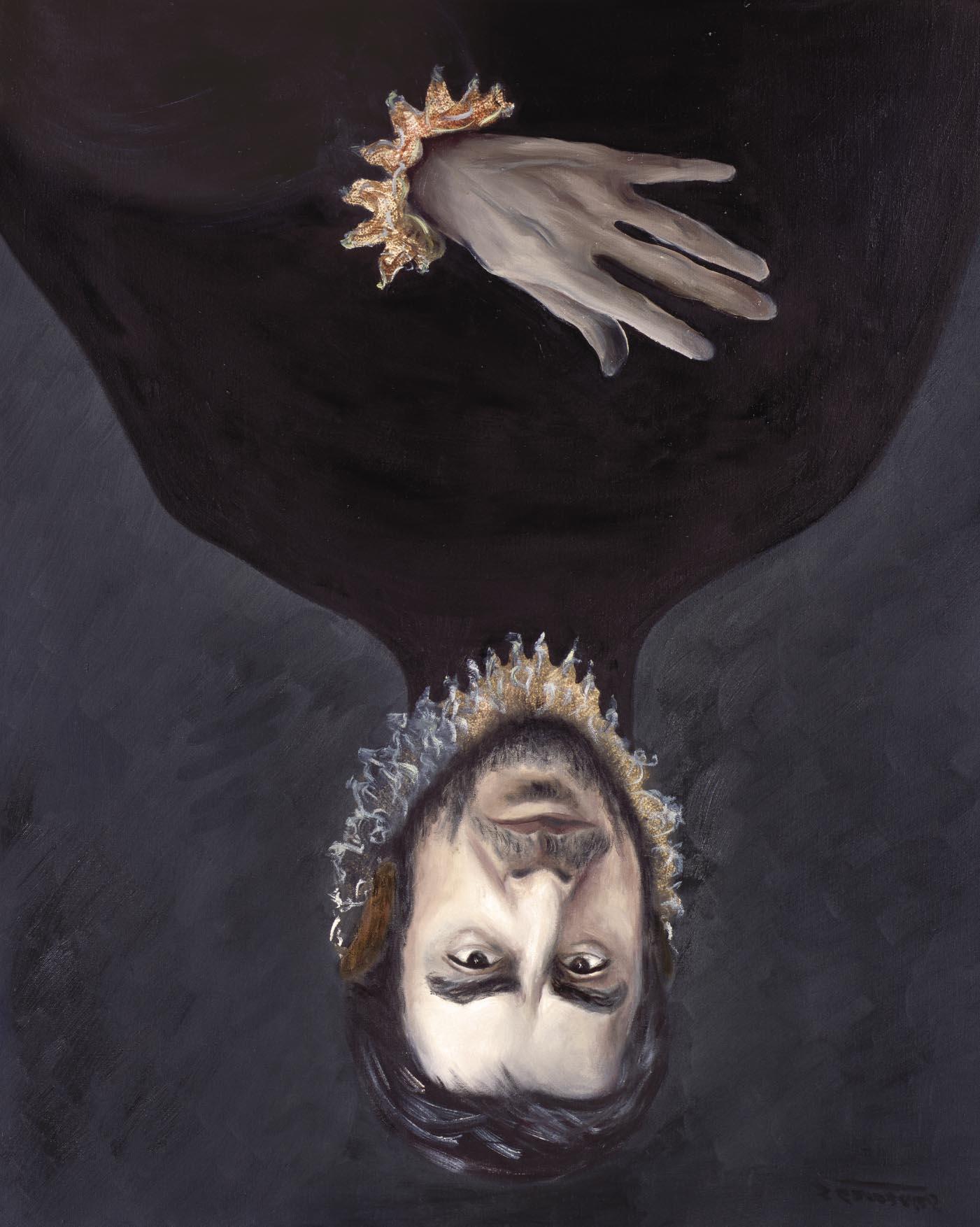

CUADROS / PAINTINGS El Caballero Rilke El Caballero Tony Servillo El Caballero Maurice Bejart El Caballero Yehudi Menuhin El Caballero Alberto Giacometti El Caballero Antonio Gades El Caballero Tzvetan Todorov El Caballero Albert Eistein El Caballero Javier Bardem El Caballero Samuel Beckett El Caballero J. M. Coetze El Caballero Gao Xinjian El Caballero Balthus El Caballero José Luis Gómez El Caballero Javier Marías El Caballero Juan Mayorga El Caballero Juan Marsé El Caballero José Álvarez Junco El Caballero Montxo Armendariz El Caballero Federico Mayor Zaragoza El Caballero Antonio Muñoz Molina El Caballero Gregorio Marañón El Caballero Antonio Banderas La Caballero Cate Blanchett La Caballero Frida Khalo La Caballero Tilda Swinton La Caballero Angelina Jolie

20 22 24 26 30 31 36 40 44 49 51 53 54 58 62 67 68 69 70 71 72 77 78 83 84 88 89

El Caballero Steven Spielberg El Caballero Martin Scorsese El Caballero Pedro Almodóvar El Caballero Paul Auster La Caballero Penélope Cruz El Caballero Plácido Domingo El Caballero Robert de Niro El Caballero Georgio Armani El Caballero Willem Dafoe La Caballero Paca Sauquillo La Caballero Maria Callas El Caballero Julian Schnabel El Caballero Nanni Moretti El Caballero Woody Allen El Caballero Clint Eastwood El Caballero Luchino Visconti La Caballero Audrey Hepburn El Caballero Gianni Vattimo La Caballero Greta Garbo El Caballero Eduardo de Santis La Caballero Salma Hayek El Caballero Eduardo Mendoza El Caballero Paco de Lucía El Caballero “Manolete” El Caballero Víctor Ullate El Caballero Al Pacino (Shylock) El Caballero Claudio Magris

92 95 96 99 100 102 104 105 106 108 110 112 114 115 116 118 120 122 123 124 126 128 132 134 136 137 138

PRE S EN TAC ION

11

A Domenico Theotocopoulos (Creta 1541-Toledo 1614)

The nobleman with the hand on the chest

El caballero de la mano en el pecho

I began in 2013 my series Homage to El Greco: “The nobleman with the hand on the chest”, a painting in grey shades, painting in pure form. This portrait will be one of the great works of El Greco. It is a trial of a single portrait, truly deriving from Titian and Tintoretto, but developed by him with a very personal style. Technically, each portrait is a world and Venice will be essential in the life of the painter.

Comencé en 2013 mi serie Homenaje a El Greco: “EL caballero de la mano en el pecho”, un cuadro de tonos grises, pintura en estado puro. Este retrato será una de las grandes obras del Greco. Es un ensayo de retrato individual, en verdad derivado de Tiziano y Tintoretto, pero que él desarrollará con un carácter muy personal.Técnicamente cada retrato es un mundo y Venezia será fundamental en la vida del pintor.

When he arrives to Venice, El Greco is a painter of icons, when he leaves Venise is an extraordinary painter with the brilliant colors of the “Scuola Veneziana”, the oil technique and the innate sense of color. Working in a venetian bottega, he will know thoroughly the thecnic of the great venetian masters. There is before and after Venice.

Cuando llega a Venezia, El Greco es un pintor de iconos, cuando deja Venezia es un pintor extraordinario con los brillantes colores de la “scuola veneziana”, la técnica del óleo y un innato sentido del color. Trabajando in una bottega di Venezia conocerá a fondo la técnica de los grandes maestros venecianos. Hay un antes y un después de Venezia.

For an artist of the Renaissance, the important was not drafting materially the painting. The important was the “Idea”, and idea and intellectual creation are fundamentals in El Greco.

Para un artista del Renacimiento, lo importante no era la ejecución material del cuadro, lo importante era “la Idea”, e idea y creación intelectual son fundamentales en El Greco.

My idea was to take up again the character of the “The nobleman with the hand on the chest” and make noblemen and noblewomen of other time, ours. In this cavalcade appear Rilke, Albert Einstein, Yehudi Menuhin, Maria Callas, Luchino Visconti, Steven Spielberg, Frida Kahlo-Salma Hayek, Robert de Niro, Penélope Cruz, Javier Bardem… till 54 characters… for the moment being.

Mi idea fue retomar el personaje del “El caballero de la mano en el pecho “y hacer caballeros y caballeras de otra época, la nuestra”. En esta cabalgada surgen Rilke, Albert Einstein,Yehudi Menuhin, Maria Callas, Luchino Visconti, Steven Spielberg, Frida Kahlo-Salma Hajek, Robert de Niro, Penélope Cruz, Javier Bardem… así hasta 54 personajes… de momento.

El Greco had a great influence on modern painting, from Cezanne to Modigliani, Pollock, Matta, Giacometti…we must be thankful to Venice and its Scuola for giving us this extraordinary painter.

El Greco ha tenido una gran influencia sobre la pintura moderna, de Cèzanne a Modigliani, Pollock, Matta, Giacometti… debemos agradecer a Venezia y a su scuola por habernos dado este extraordinario pintor.

AC E R C A DE SOFÍA

15

Sofía Gandarias Guernica, 1951 - Madrid 2016

1973-79. Estudios en la Escuela Superior de Bellas Artes de San Fernando de Madrid obteniendo los Títulos de Profesora de Dibujo y, posteriormente, Licenciada en Bellas Artes por la Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Tesina sobre el Retrato. Miembro del Patronato de la Fundación Yehudi Menuhin España. Miembro del Comité cientítifico del Instituto Internazionale per l’Opera e la Poesia di Verona. (UNESCO). Directora del curso: “La Mirada, las miradas”. Universidad Complutense de Madrid 2008 2005. Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres de la République Française. 2008. Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur de la République Française.

ALGUNOS DATOS BIOGRÁFICOS Y EVENTOS ARTÍSTICOS: 1978. Pinta el retrato de:“Kokoschka-Alma-Mahler”. 1979. Pinta el retrato de:”La Pasionaria”. 1980. Realiza la serie:“La protesta del silencio“. 1981/82.Viaje a Oriente Medio y realiza el retrato de “Nur de Jordania“. 1982/86.Trabaja en la serie“Presencias“: retratos de “Augusto Roa Bastos“, “Federico García Lorca“, “Miguel Ángel Asturias“, “Jose Bergamín“, “Jorge Luis Borges“, “Alejo Carpentier“, “Eduardo Carranza“, “Rosalía de Castro“, “Julio Cortazar“, “Salvador Dalí“, “Rubén Darío“, “Rómulo Gallegos“,“ Guimaraes Rosa“, “Gabriel García Márquez“, “Gabriela Mistral“, “Pablo Neruda“, “Juan Carlos Onetti“, “José Ortega y Gasset“, “Octavio Paz“, “Juan Rulfo“, “César Vallejo“. También realiza los retratos de “Doris Lessing“ y “Graham Greene”. 1985. Viaja a México y visita la Casa Azul de Coyoacán. 1987. Contrae matrimonio con Enrique Barón Crespo en Venecia. 1988. Nace su único hijo Alejandro, deja de pintar por motivos de salud. 1990. Vuelve a la pintura realizando los retratos: “Alejandro con el caballito“,“Melina Mercuri“ y “Antoni Clavé“. 1991. Pinta: “Alejandro en el Florian”. 1992. Retrata a Nureyev, y comienza la serie:“Toreo y Ballet“. Pinta los retratos de:“Bacon”, “Diego y Frida”, “Autorretrato con Delvaux”; Realiza las series:“Amor en Venecia“, “Iris”y“Arte contra violencia“. Realiza el tríptico:“Sarajevo“. 1993. Pinta los retratos de: “Yehudi Menuhin”, “Aligi Sassu” y Helenita Olivares”,“Dirección Mujeres“ con Simone Veil y la reaparición de Frida Kahlo,

16

HOMENAJE A EL GRECO

“Choque de civilizaciones”. Series “Brel” y “El Gorila Kumba”. Comienzo de la serie:“Avarizia” y “Greed: the graves of humanity”. 1994.Pinta “Love Prayer”, con Barbara Hendriks; “La mano herida ( Sarajevo )”, con Susan Sontag y Juan Goytisolo. Pinta también los retratos de: “Carlos Fuentes”, “François Mitterrand”, “Hugo Claus” y“Emile Veranneman”. Viaja a México 1995.Realiza la serie “Pessoa”, “O ano do nascimento de Ricardo Reis“ con José Saramago, serie “El espectador“, con Albert Camus y Maria Casares,“Poderoso caballero, Don Dinero”, “The Money: Bankers’ brunch in Wall St”. 1996. Realiza los retratos de:“Edith Piaf-Yves Montand”, “René Cassin” y “Sami Nair”. Sigue las series :“Avarizia” y “Greed: the graves of humanity”. 1997. Pinta “Los sueños de Buñuel” y “Le chat mondain“, el retrato de:“Jorge Semprún” y las series: “Stop-Ahead“,“La Poesía”, continua las series: “Iris”,“Avaricia” y“Greed: the graves of humanity”. 1998. Pinta las series: “Pájaros en prèt-à-porter y alta costura“, “Kumba hotline“ y“La chatte mondaine“. 1998/99. Pinta el tríptico:“Guernica”, y continua la serie : “Iris”. 2000. Pinta la serie: “Primo Levi, la memoria“. 2001/02.Pinta la serie: “NY 11 S, NY 9/11“. 2002/03. Realiza los retratos de:“Jorge Edwards”, varios de “Maria Callas” y continua la serie:“Iris”. 2004. Pinta las series: “Messaggio““Príncipes venezianos“y el cuadro : “I bravi“ 2004/5. Pinta la serie: “El llanto de las flores”y el cuadro:“Madrid 11-M”.Entrega del retrato “Nureyev” y “El pájaro de fuego” a la Biblioteque Nationale de France, Palais Garnier Paris. 2006/09. Realiza la serie: “Kafka, el visionario” con retratos de: “Kafka”, “Milena”, “Max Brod”, “Imre Kertesz”, “Walter Benjamín”, “Germaine Tillion”, “José Saramago”, “Paul Celan”, “Philip Roth”, “Jean Amery”, “Carlos Fuentes”, “Gianfranco de Bosio”, “Marie Curie”, “Rita Levi- Montalcini”, “Kurt Weil-Bertolt Brecht”, “Rilke”, “Jaroslav Seifert”, “Primo Levi”, “Hanna Arendt”. Realiza también interpretaciones sobre textos de Kafka:“El proceso”,

“La colonia penitenciaria”, “América”, “Informe para la Academia”, “Descripción de una lucha”, “Carta al Padre I y II”, “La metamorfosis”, “El Castillo”,”Investigaciones de un perro”, 2007. Entrega del retrato: “ Lorca”. Museo Federico García Lorca.Fuentevaqueros. Granada.; Entrega del retrato: “Rita Levi Montalcini“. Fondazione Levi Montalcini. Roma. 2008. Pinta el cuadro: “Yes, we can:Obama-Luther King”, el retrato de: “Vargas Llosa”. Inicia la serie:“Gandhara Silencios”.Entrega de los retratos:“Juan Rulfo” y “Julio Cortázar“, a la Cátedra Cortázar. Universidad de Guadalajara. México. 2010. Pinta las Coloquio de los perros” y. Realiza los retratos de:“Edgar Morin”, “Gabriela Mistral”,“Amalia Rodrigues”, Los cuadros:”,“Un ballo in maschera” y “Encerrados”. 2011. Continua las series:“Gandhara(Silencios)”,“ “Greed: the graves of humanity;Entrega del retrato de: “César Vallejo“, a la Biblioteca Nacional de Lima. Lima.Perú.Entrega de: “Blaues Sofa in Gedenken an Jorge Semprún”.Bertelsmann.Berlín. 2012. Publica el libro:“Presencias Instantes”, por encargo de la Secretaria General Iberomericana (SEGIB).Series “Encerrados”; Inicia la serie “Peggy’s Tango” 2013. “Peggy’s Tango”, “Il Método Bertone”,“La camarlenga” y “Homenaje al Greco”; Entrega del cuadro: “Miserere (Julianna)“, al NY 9/11 Museum. NewYork. 2014. Serie “Retrato del Papa Francisco, Vaticano I; „Un ballo in maschera“ “ Retrato“Carlo Rubbia”. Inicia la serie “Homenaje al Greco” 2015. Pinta las series: “Serie Kim Jong-Un, Amarás al líder sobre todas las cosas”y“Homenaje al Greco”. Entrega del cuadro: “Retrato de Jorge Semprún“, al Parlamento Europeo. 2016. Entrega del retrato de: “Papa Francisco“, a la Iglesia de San Antón (Mensajeros de la Paz); “Gabriela Mistral“, a la Biblioteca Nacional de España; Entrega del cuadro: “Anna Bolena-Callas“ al Teatro Real de Madrid; Entrega del retrato de: “José Bergamín“, al Museo de la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. Madrid; Entrega de la serie:

Sofía Gandarias

“Primo Levi“, a la Universidad Hebrea. Jerusalen; Entrega del retrato de: “Germaine Tillion“ al Musée de la Resistance Française. 2017.Entrega del retrato de: “Pïo Baroja“, a la Real Academia Española de la Lengua. Madrid

EXPOSICIONES INDIVIDUALES: 1980. Museo Municipal de Santander. 1986. “Presencias“. (Exposición itinerante).Sala de exposiciones del Banco de Bilbao.Madrid;.Sala de exposiciones de la Caja Postal. Cádiz. 1987. “Presencias“. (Exposición itinerante). Sala de exposiciones del Banco Central. Bruselas. Casa de la Cultura. Amberes. Sala de exposiciones de Caja Madrid. Barcelona. 1988. “Presencias“. (Exposición itinerante). Museo de Albacete. .Sala de exposiciones de la Casa de la Cultura de Torrelodones. Madrid. 1989. “Presencias“. (Exposición itinerante).Palacio Garcigrande. Salamanca. 1990. Exposición Retrospectiva. Palazzo Barzizza Torres. Venecia. 1995. “Pour la tolérance”. 50º Aniversario de la UNESCO.(Exposición itinerante). Palais de la Berbie. Albi.“Pela tolerancia“ Palacio das Galveias. Lisboa. 1996. .“Pour la tolérance”. Fondation. “Le toit de la Grande Arche“. Paris. 1997. Veranneman Stichting. Kruishoutem (Bélgica). 1998. “Pessoa. Camus” Fondation Gulbenkian. Paris. 1999. Presentación del Tríptico “Gernika” en el Parlamento Europeo (Bruselas). Entrega y Exposición en el Museo Museo de Guernica. Gernika. 2000/1. Serie “Primo Levi la memoria“. (Exposición itinerante). Spazio Auditorium Verdi. Milán. 2002. “Primo Levi, la memoria“. (Exposición itinerante). Palazzo Cisterna. Turín.Museo de Historia Moderna, Ljubljana. Eslovenia. 2003. “Primo Levi, la memoria“. (Exposición itinerante). Galeríade la Biblioteca Berio.Genova. 2004. “Primo Levi, la memoria“. (Exposición itinerante). Fundación de las Tres Culturas. Sevilla. Palacio de la Merced. Córdoba.

2004. Exposición de la serie: “NY 11 S“. Palazzo Caccia Canali, Sant’ Oreste. Italia. 2005. “Primo Levi, la memoria “. (Exposición itinerante)Museo del Ferrocarril. Madrid. 2005. Exposición de la serie: “NY 11 S“.RoccaAlbornoziana, Spoleto; Cartel dell’Ovo. Nápoles. 2006. Exposición de las series: “El llanto de las flores“ y“Madrid-11 M”. Centro Cultural Paco Rabal. Madrid. 2007. Exposición de la serie: “NY 11 S“. Real Academia de España en Roma. 2008. “Primo Levi, la memoria“. Zagreb. Croacia. 2009. Serie“Kafka, der Visionär“.(Exposición itinerante). Haus am Kleistpark. Berlin. 2010. “Kafka, der Visionär“. (Exposición itinerante). Ariowitsch Haus. Leipzig.; Czech Center-Instituto Cervantes. Praga. 2016. Serie“El Coloquio de los perros“.(Exposición itinerante). Espacio Santa Clara. Sevilla; Antiguo Hospital Santa Maria la Rica. Alcalá de Henares;. Instituto de Cultura Mexicano. Madrid Centro Cultural Español. Ciudad de México; Serie Kafka el visionario“. Campo de concentración Bergen Belsen /Alemania). 2017. “Sofía Gandarias: Mujeres“. Sala de exposiciones de la Facultad de Bellas Artes de Madrid. Universidad Complutense. Madrid. 2018. “Gernika”. Abadía Benedictina del Monasterio de Silos. Burgos.

EXPOSICIONES COLECTIVAS: 1979. Bienal de Oviedo. 1980. Muestra pro Derechos Humanos.Madrid. Premio Francisco de Goya Centenario Círculo de Bellas Artes. 1983. Francisco de Alcántara. 1984. Salón de Otoño Bienal de Pontevedra. 1984. Fundación Santillana. Cantabria. 1997. Fondation Delvaux. St. Idesbald. Bélgica. 1998. Veranneman Stichting. Bélgica. 1998. Casa natal de García Lorca. Fuentevaqueros. Granada. 2004. Centenario de Pablo Neruda. Museo de América. Madrid.

17

18

HOMENAJE A EL GRECO

2008. “A consistencia dos sonhos”.Retrato de Saramago.Palacio de Ajuda. Lisboa. Instituto Tomie Ohtake Sao Paulo. Brasil. 2010. Retrato de Gabriela Mistral, Museo de América (Madrid)

MUSEOS Y COLECCIONES: Museo de Albacete. Museo Municipal de Santander. Museo de la Paz Gernika. Burdeos. Ca Pessaro (Venecia). Malabo (Guinea). Museo Provincial (Ciudad Real). Garcia Lorca. Fuentevaqueros. Granada. International Yehudi Menuhin Foundation Fundación Yehuci Menuhin. España Parlamento Europeo. Bruselas Senado. Madrid. Casa Museu Fernando Pessoa. Lisboa. Museu da Cidade. Lisboa. Universidad Carlos III. Madrid. Fundación Príncipe de Asturias. Palacio Real de Jordania. British Red Cross. Sede UNESCO. Paris. Universidad de Dili. Timor. Veranneman Stichting. Bélgica. Teatro de la Fenice (Venezia). Casa Neruda Isla Negra (Chile) Musée Garnier (Ópera de Paris). Fondazione Levi Montalcini (Roma. Cátedra Cortázar(Guadalajara, México). Biblioteca Nacional (Lima, Perú). 9/11 Memorial Museum (Nueva York). Biblioteca Nacional de España. Teatro Real. Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando (Madrid). Musée de la Resistance Française. Universidad Hebrea (Jerusalen). RAE

COLECCIONES PRIVADAS: Paris, Venecia, Bruselas, Amberes, Londres, Estrasburgo, Milán, Los Ángeles, Boston, Quito, La Paz, Madrid, Barcelona, Santander, Mallorca, México, Nueva York, Lisboa, Tokio, Copenhague, San José de Costa Rica, Florencia, Roma, Atenas, Berlín, Berna, Sevilla, Chiclana (Cádiz).

BIBLIOGRAFÍA: 1980: “Kokoschka-Alma-Mahler”, edición a cargo de José García Nieto, RNE editores. 1981: Exposición en el Museo Municipal de Santander. Textos de Enrique Azcoaga, José Hierro, Manuel Conde y José Mº Iglesias. 1986: “Presencias”, exposición en la Fundación Banco de Bilbao, texto de Augusto Roa Bastos. 1990: Sofía Gandarias, “Retrospectiva”, Arsenale Editrice, SL. 1995: “Pela Tolerância”, exposición Palacio dás Galveias. Textos de José Saramago. Ediciones Pelouro de Cultura. 1996: “Pour la tolérance”, exposición en la Grande Arche de la défense (París). Textos de Federico Mayor Zaragoza, Carlos Fuentes, Juan Goytisolo, Simone Veil, Yehudi Menuhin y Sami Naïr. 1999: “Arte en el Senado”, texto de Guillermo Solana. 1999: “Guernica de Sofía Gandarias”, por Kosme de Barañano, ediciones Museo de la Paz, Guernica. 2001: Catálogo “Primo Levi, la memoria”, en Milán. Textos de Jean Samuel, Simone Veil, TF ediciones. 2002: “Primo Levi, la memoria”, en Turín. Textos de Gianni Vattimo, Gianfranco de Bosio, Jean Samuel. TF ediciones. 2003: “Primo Levi, la memoria”, Museo de Historia Moderna, Liubliana. Textos de Demetrio Volcic, Ciril Zcobec. 2004: “Primo Levi, la memoria”, en la Fundación de las Tres Culturas. Textos de Diego Carcedo, Gianni Vattimo, Reyes Mate, Jean Samuel, Gianfranco de Bosio. 2007: “New York 9/11”, Rocca Albornoziana, Spoleto (Italia). Textos de Sami Naïr, Gianfranco de Bosio y Edward Malefakis. “New York 9/11, Sofía Gandarias”, exposición en la Real Academia de España

en Roma, 2007. Ediciones de la Cooperación Cultural Española en el Exterior. 2009: “Kafka, der Visionär”“, Haus am Kleistpark, Berlín. Textos de Rita Levi Montalcini y Michael Nungesser; “ Der Club Bertelsmann” Leipziger Austellung.pdf 2010: “Kafka, el Visionario”, Czech Center, Instituto Cervantes. Texto de José Saramago. «Saramago: «Dio non ha letto Kafka»». www.corriere.it http://www.corriere.it/cultura/10_luglio_05/depetrissaramago-dio-kafka_ 2012 publicación de “Presencias Instantes” por la Secretaria General Iberoamericana (SEGIB) con textos de Augusto Roa Bastos, Francisco Jarauta, Carlos Fuentes, José Saramago, 2015 2ª edición “Presencias Instantes” SEGIB 2016 Juan Cruz «Sofía Gandarias, retratista de la literatura». Cultura.elpais.com José Garcia Abad, “ Sofía Gandarias, agitadora de conciencias”El Siglo 8–14 febrero Anaïs Sanchez “La pintora que dio color a la escritura” El Siglo 1-7 febrero Kosme de Barañano “Fieramente humana”, El Mundo Alison Moss. “A tribute to the late basque painter sofia gandarias” https://theculturetrip.com/europe/spain/articles/atribute-to-the-late-basque-painter-sofia-gandarias/ ver en noticias www.gandarias.es Prof. Julián Garcia Sanchez, “Sofía Gandarias, El llanto de las flores”, IV Simposio Humanidades, Oftalmología. Hospital La Paz. file:///C:/Users/enrique/Downloads/Gandarias%20pptx%20copia%20 2%20(1).pdf “El Coloquio de los perros “ con ilustraciones de Sofía Gandarias, Ed. Gredos

www.gandarias.es

…ven cuando debas. Todo esto llegará a través de mí hasta tu aliento. Por ti lo he contemplado yo, sin nombre, largo tiempo, lo he mirado desde la pobreza y lo he amado tanto como si tú no lo hubieses ya asumido. Toledo, Noviembre de 1912 Rainer María Rilke

Sofía Gandarias

Yehudi Menuhin

“Peace flows like a river and brings passion and serenity into balance.When a long-suffering soul brimming with compassion is joined with a temperament which bellows out its rejection of the intolerable, when the creative impulse is combined with the power and precision of a great artist, we have both genius and masterpiece, and dare I say it, a being filled with grace and mystery.”

“La paz es un flujo que enlaza a la vez pasión y serenidad, pero en equilibrio. Cuando un alma sensible y llena de compasión se alia con un temperamento que grita el rechazo a lo intolerable, cuando el impulso creador se alía con la maestría y la precisión de un gran arte, teneís a la vez genio y obra maestra y, si puedo decirlo, un ser lleno de gracia y misterio.”

Yehudi Menuhin was an American-born humanist, violinist and conductor. He was a British Lord (Baron Menuhin OM, KBE) and European by choice. He received the Prize Príncipe de Asturias, Wolf Prize, and the Ernst von Siemens Music Prize, among many others.

Yehudi Menuhin, fue un humanista, violinista y director de orquesta nacido en los Estados Unidos. Fue Lord Británico (Baron Menuhin OM, KBE) y ciudadano europeo de opción. Recibió los premios Príncipe de Asturias, Wolf, y Ernst von Siemens, entre muchos otros.

#1

El Caballero Rilke Óleo sobre lienzo / 100 x 81 cm. / 2013

21

22

HOMENAJE A EL GRECO

#2

El Caballero Tony Servillo Óleo sobre lienzo / 100 x 81 cm. / 2013

Sofía Gandarias

23

Simone Veil For tolerance

Por la tolerancia

In its own way, the exhibition of Sofia Gandarias contributes to the battle that each one of us must wage on behalf of tolerance. Some people contribute orally, others in writing. Sofia has chosen painting. First of all, we seek to be tolerant ourselves, setting an example for others; we try meanwhile to function so that together individuals and nations become aware of the fundamental aspect of this collecrive and personal responsibility that nowadays, unfortunately, is being put to a challenging test.

A su manera, la exposición de Sofía Gandarias contribuye a la lucha que cada uno de nosotros debe llevaren favor de la tolerancia. Algunos contribuyen con la palabra, otros con sus escritos. Sofía Gandarias ha elegido la pintura. Tratemos ante todo ser nosotros mismos tolerantes. Lo cual exige un despertar hacia el otro: intentemos también actuar para que los grupos humanos y los Estados tengan conciencia del carácter primordial de este compromiso colectivo y personal que desgraciadamente está sometido a difícil prueba.

Through her portraits, thanks to the connections they forge between themselves and events, Sofia Gandarias reminds us that despite the drama of the moment, one must never despair at being human. Sarajevo, martyred city, city the new barbarians want to destroy in order to destroy with it the symbols of tolerance it represents, city which resi ts, to hope. The paintings of this artist are at once a cry of desperation and a cry of hope.

Por sus retratos, por los lazos que establece entre ello y los acontecimientos, Sofía Gandarias nos recuerda, a pesar de la dramática actualidad, que no hay que desesperar nunca del ser humano. Sarajevo, ciudad mártir, ciudad que los nuevos bárbaros quieren destruir por el símbolo de tolerancia que representa, ciudad que resiste, ciudad que mantiene su esperanza a pesar de todo. Las pinturas de la artista sobre la ciudad son a la vez un grito de desesperanza y de esperanza.

Desperation in the face of murderous madness and ethnic cleansing, desperation owing to the schism imposed on a people who would live in harmony, desperation before the tombs of small children.

Desesperanza frente a la locura asesina y la purificación étnica, desesperanza debida a la fractura impuesta a pueblos que vivían en armonía, desesperanza ante las tumbas de criaturas.

Hope that demonstrates that a dialogue, a living in harmony among minorities, and the coexistence of religions can exist, and serves that on which depends the fate of mankind, and the future of our children.I hope that this message will be heard by everyone, because each one of us is responsible for the tolerance that cries out for solidarity and offers us peace.

Esperanza para demostrar que el dialogo, la convivencia entre minorías y la coexistencia entre religiones pueden existir y que de ello depende la suerte de la humanidad, el futuro de nuestros hijos. Deseo que este mensaje sea escuchado por todos porque todos y cada uno somos responsables de la tolerancia que apela a la solidaridad y nos ofrece la paz.

Simone Veil was a french lawyer and politician, and a survivor of the Holocaust. She was a Government Minister, first President of the European Parliament directly elected, and member of the French Constitutional Council. She was receipient of the Prince of Asturias Award.

Simone Veil fue una abogada y política francesa, superviviente del Holocausto. Fue Ministra de Gobierno, primera Presidenta del Parlamento Europeo elegido por sufragio directo, y miembro del Consejo Constitucional de Francia, entre otros cargos. Recibió el Premio Príncipe de Asturias.

24

HOMENAJE A EL GRECO

#3

El Caballero Maurice Bejart Óleo sobre lienzo / 100 x 73 cm. / 2013

Sofía Gandarias

25

Augusto Roa Bastos El ojo visionario de Sofía Gandarias

El ojo visionario de Sofía Gandarias

What is the significance of the art of the portrait –and od painting itself– for Sofia Gandarias? As she herself has said in relation lo the revolution brought about in modern painting by her master, Velazquez, the secret may lie in turning all painting into portraiture. This principle suggests that the presence of the human figure at the centre of her art does nor merely represent a preference for a certain kind of subject-matter; rather, it is the focal point of her vision of the world, life and society. Her art is thus the expression of -to put it in her own terms- a vital awareness of the world and the time that she lives in, in the spirit of a commitment which is both moral and aesthetic.This attitude implies a choice based on experience, as the very essence of her vocation. Her task is of great difficulty and complexity; it could be redefined. if we invert Velazquez's principie, as turning all portraiture into painting: that is, turning portraiture into the 'central idea' of painting.

¿Qué es el retrato, y, en definitiva, qué es la pintura para Sofía Gandarias? Acaso, como ella misma lo seña-a propósito de la revolución instaurada en la pintura moderna por su maestro Velázquez, consista en hacer que la pintura toda sea retrato. Principio que nos llevaría a entender que la figura humana en cuya estética se basa principalmente no es una simple preferencia temática, sino el centro focal de una visión del mundo, la vida, de la sociedad. Su estética se convierte así en expresión de lo que la artista llama conciencia vital de la realidad y del tiempo que le toca vivir. Actitud que ella asume como un compromiso a la vez ético y estético. Tal actitud define una elección experimentada como el sentido mismo de su vocación. La más difícil y compleja, la que podría redefinirse, invirtiendo el principio de Velázquez: hacer que el retrato todo sea pintura; o sea, hacer que el retrato se constituya en la «idea central» del hecho pictórico.

If we adopt this totalizing concept, then, by a kind of pictorial metonymy, the part or particular form -the portrait- comes to embody the whole painting- in all its varied manifestations. This idea arises at a rime when -as the artist herself recognizes- figurative forms, and especially portraiture, are in decline. Nevertheless, these forms are rooted in the beginnings of human history, and lie at the base of all the world's art. From Plato's cave to the caves of Altamira and the milieux of contemporary painting, shadow and profile have been synonymous with image –with the imago– which has been endlessly created and destroyed over history and prehistory.

Esta idea globalizadora concibe que por una suerte de metonimia pictórica una parte, una forma, el retrato, encarne la totalidad de la pintura en sus múltiples manifestaciones.Y todo esto en una época en que, como la propia artista lo reconoce, se asiste a la declinación de las formas figurativas, en particular la del retrato. Formas que sin embargo ahondan sus raíces en los comienzos de la historia humana y forman los orígenes sedimentarios de la historia universal del arte. Desde las cavernas de Platón a las cuevas de Altamira y los centros de pintura con-temporánea, sombra y figura son sinónimo de imagen (de la imago) que se integra y desintegra sin cesar en historia y prehistoria.

Augusto Roa Bastos was a Paraguayan writer, journalist and script author. He holds the Cervantes Prize, the Latin American Memorial Prize for Letters, andthe British Council Prize, among many others.

Augusto Roa Bastos fue un escritor, periodista y guionista paraguayo. Recibió el Premio Cervantes, el Premio de las Letras Memorial de América Latina, y el British Council Prize, entre muchos otros.

Sofía Gandarias

In full awareness of this situation, Sofia Gandarias has made her choice, not out of a melancholy clinging to a lost cause, bur from an exemplary commitment to self-discipline. She is thus able to contribute, within her capacities and limits, with new symbols in visual language, to the enrichment and renewal of an art in constant flux. It is her task to find –in the terms of Kafka's marvellously brief parable– that ray of light which has always been here yet exists (or appears) only when discovered by the visionary eye.

Consciente de esta situación, Sofía Gandarias asume su elección no como un melancólico desafío ante una causa perdida sino como una ejemplarizadora voluntad de ascesis. Ello le permite contribuir, dentro de sus posibilidades y sus límites, con nuevos signos en el lenguaje de lo visible, al enriquecimiento y renovación de un arte en continua metamorfosis. Encontrar, según la brevísima parábola de Kafka, ese rayo de luz que siempre estuvo ahí pero que no existe (que no aparece) más que cuando el ojo visionario lo descubre.

This possibility of the unknown is to be found above all in the most familiar places. Authentically new creation arises not in the actual product, but in the way of producing that timeless thing, reborn with each new day, which is art. The unknown reveals itself in the meeting of artist, artwork and public. For change does not happen only in the creative art which embodies the private world of the creator; there is also constant change and evolution in the gaze of the person who appropriates the artwork and is possessed by it, in what may be called the art of contemplation.

Esta posibilidad de lo inédito se encuentra en los caminos más trillados y precisamente en ellos. Lo inédito se produce no en lo que se hace sino en cómo se hace esa cosa sin tiempo que es el arte pero que a cada mañana renace. Lo inédito se revela en la confluencia del espectador, el artista y la obra. Porque lo que cambia no es solamente el arte creativo en el que está presente el mundo íntimo del creador: cambia también y evoluciona constantemente la mirada del espectador que hace suya la obra y se deja poseer por ella, en lo que podría llamarse el arte de la contemplación.

From the meeting in the artwork of two subjectivities –those of the artist and the person who contemplales– there arises the revelatory power of the work itself, as a third subjectivity which expresses and links the first two, in keeping with the cultural and social density of their world.

El encuentro en el cuadro de las dos subjetividades –la del artista y la del observador– permite así el surgimiento de los valores de revelación de la obra como otra subjetividad que comunica y correlaciona las dos anteriores según el espesor cultural y social en que estas subjetividades se hallan inmersas.

If painting is a representation or language of the visible, the portrait form (this term is more appropriate than "genre") obviously implies an individualized object and an immediately realized background.This individualized representation of living models, which our period sees as lifedenying and anti-human, is one of the most attractive aspects

#4

El Caballero Yehudi Menuhin Óleo sobre lienzo / 100 x 81 cm. / 2013

En este espectáculo o lenguaje de lo visible que es el arte pictórico, la forma retrato –para no hablar más de género, impropiamente– comporta, como es obvio, individualización del objeto e instantaneidad de la escena. Y se me ocurre pensar que esta representación individualizada de modelos vi-

27

28

HOMENAJE A EL GRECO

vientes, en nuestra época negadora de la vida y de lo humano, es uno de los alicientes mayores en la elección temperamental y estética de nuestra artista. Tal individualización e instantaneidad supondrían sin embargo, en un primer momento, el aislamiento del objeto en sí en un espacio que sólo a él corresponde: espacio que por ello mismo quedaría abolido o en suspenso. El tiempo incluso quedaría abolido o en suspenso en esa instantaneidad que se volvería pura permanencia. Duración inmóvil de la escena en torno al objeto (el modelo) convertido en sujeto: es decir, en una presencia inmutable. Y esta presencia es la de un personaje identificable, la de un individuo representativo, que el retrato en cierto modo no puede no exaltar y celebrar. Por otra parte, esta situación de individualización e instantaneidad de la escena, metamorfoseada en visualidad pura –o si se quiere, en pura inmanencia– parecería contradecir el anhelo de unión y comunión de la artista con su sociedad. Parecería negar su deseo explícito de acogerse a la realidad, de dar forma a las realidades de su época; de hacer que su estilo y su lenguaje sean expresión de una temporalidad y de una visión abierta y en movimiento. Lo cierto es que el arte de Sofía Gandarias logra hacer real en sus cuadros el principio de que el retrato todo sea pintura y que este hecho estético constituya un símbolo de unión entre el individuo y la sociedad. Hay en su arte una óptica o una lógica de la visión que rechaza el concepto «realista» que quiere hacer del cuadro el solo reflejo de lo real. Pero también rehúsa el concepto «idealista» que sólo busca la proyección de una subjetividad aislada en sí misma.

of the temperamental and artistic choice of our painter. This individualization and immediacy, however, necessitate in the initial stage the isolation of the object in itself, in a space of its own; that space itselfs consequently abolished or suspended. Even time is abolished or suspended in this immediacy which has become pure permanence. Against an immobile background, the object (or model) has become a subject, an immutable presence - the presence of an identifiable character, a representative individuality, which the portrait, in a certain sense, cannot but affirm and celebrate. Yet this individualized and immediate scene, transformed into a pure visual phenomenon ¬–or into pure immanence– might seem to contradict the artist's yearning for union and communion with society. It might seem to negate her explicit desire to remain attached to reality, to give form to the circumstances of her day, to employ her style and language to express a time and a vision that are open and in movement. In the work of Sofía Gandarias, the principle of turning all portraiture into painting, so as to create a symbol of union between individual and society, is successfully realized. Her art embodies a perspective on vision which rejects the notion of "realism", which would reduce painting to the mere reflection of reality; at the same time, it also repudiates the "idealist" position which is concerned only with the projection of a self-absorbed subjectivity.

Sofía Gandarias

The goal has been realized in a moment prior to the reception of the work; in the artist's own words, "between the rapid conception of the artwork and its conclusion there lies its flesh and blood - the aesthetic emotion". Between those two moments, however- between the conception and execution of the portrait- comes the slow, arduous labour of investigation, the search for models in life and art: the penetration of those intimate worlds, replete with quintessentially human grandeur and suffering. This is evident even in those of her portraits which seem to be direct or "taken from nature"; her models are perceived with pilgrims' eyes, eyes which retrace and forget the road even as they travel it. Beyond the appearance or present semblance of the model, the visionary eye, looking to the past or the future, captures the multiple faces of the human personality: the sparkle of ephemeral youth, the deceptive softness and serenity which conceal secret obsessions, true generosity- but also the ravages of time, impressed inexorably on a countenance and spirit still turned, as if in aspiration, towards the light. To paint a face is also to interpret a fact of nature. To reproduce a body, exposed like all natural bodies to its own finiteness and final disappearance, is not to copy it, but to transform it into an object that will bear witness to a life, a history, a destiny. This can only be achieved at the price of an agonized struggle (in Unamuno's sense) between the artist and her own tensions and obsessions. Impelled by a thirst for knowledge through form, the artist contemplates her models with love but not indulgence, with irony but not bitterness, combining keen sensory awareness with firmness of vision. Sofia does not illustrate her models; she unearths them. She does not decorate them with

Hay un momento, previo a la mirada del espectador, en que este hecho se ha producido. «Entre la concepción rápida y la conclusión de la obra –reflexiona la propia pintora– se sitúa la carne y la sangre de la obra de arte: la emoción estética». Pero entre esos dos momentos, la concepción y la ejecución del retrato hay el arduo y lento trabajo de indagación, de prospección en la vida y la obra de sus modelos: de penetración en esos mundos íntimos poblados de grandezas y miserias como todo lo humano. Se nota esto incluso en sus retratos directos o del «natural». Sus modelos son vistos con miradas de ojos en peregrinación que invierten y olvidan el camino al par que lo recorren. Más allá del parecido o de la apariencia actual del retratado, el ojo visionario capta, hacia el pasado o hacia el futuro, los múltiples rostros de la persona humana; los destellos de una desvanecida juventud, la mansedumbre y la serenidad simuladas que encubren secretas obsesiones, la auténtica generosidad desde luego, pero también las devastaciones del tiempo, que se anuncian inexorables sobre ese rostro, sobre ese espíritu, vueltos todavía hacia la luz como si suspiraran. Pintar un rostro es también interpretar un hecho de naturaleza. Reproducir un cuerpo, expuesto como todos los cuerpos de la naturaleza a su finitud y desaparición, no es intentar su copia sino transformarlo en el objeto testimonial de una vida, de una historia, de un destino.Y ello sólo al precio de una lucha agónica, en el sentido unamuniano, por parte de la artista, enfrentada a sus propias tensiones y obsesiones. Poseída por la pasión del conocimiento a través de las formas, la artista contempla a sus modelos con amor, pero sin complacencias, con ironía pero sin acritud, con ávida sensualidad, pero también

29

30

HOMENAJE A EL GRECO

#5

El Caballero Alberto Giacometti Óleo sobre lienzo / 100 x 73 cm. / 2013

Sofía Gandarias

#6

El Caballero Antonio Gades Óleo sobre lienzo / 100 x 73 cm. / 2013

31

32

HOMENAJE A EL GRECO

con mirada implacable. Sofía no ilustra sus personajes: los excava. No los adorna con metáforas ni alegorías parásitas: los desnuda en su íntima verdad en la que trasfunde la suya propia. Es evidente que no le interesa el «color local» de los cuerpos, de los rostros. Ella trabaja con esos materiales tocados, penetrados, vividos interiormente en esa cámara oscura, taller, caverna, de las propias intuiciones, donde la visión se organiza y proyecta. Aquí ya no es el «tema» (rostro, cuerpo, gesto, la ineluctable sombra de la soledad humana envolviendo al individuo) el elemento que predomina. Lo que importa esencialmente ahora es la materia inasible pero no impasible que está allí en medio de esa luz irreal cortada de sombras, de iridiscencias, de trazos fulmíneos, de planos quebrados y superpuestos, de depresiones oscuras y fantasmales, que acaban también fantasmatizando las figuras. Sofía no pinta «efectos». Sobre el fondo, que casi nunca es neutro aunque parezca vacío o «despoblado»; sobre ese espacio también como imantado y en espera, ella prepara las condiciones para el surgimiento del efecto en la sensibilidad del espectador. Su tratamiento pictórico está hecho por momentos de rigor geométrico o de estados de abandono y de ausencia que responden a la lógica onírica del cuadro. Es entonces cuando los elementos iniciales de la figuración se abstractizan según los modos genuinos de la abstracción. Líneas reverberantes se entrecruzan en el espacio de los cuadros que parece de pronto constelado por fragmentos de espejos rotos. Hay una continua refracción de planos y dimensiones en medio de esas oquedades sombrías en las que los colores se reabsorben como teñidos de penumbra. El color no reaparece como una en-

metaphors or parasitic allegories; she exposes them in their intimate truth, modified by the artist's own truth. She is obviously not interested in the 'local colour" of bodies and faces. She works with those materials as they have been retouched, penetrated and lived from the inside in that camera obscura, workshop or cave of intuition where vision takes form and projects itself. Here, the dominant element is no longer the "subject" (the face, the body, the gesture or the inevitable shadow of human solitude around the individual). What matters now is the ungraspable but not inert matter present in the midst of that unreal light, transfixed by shadows, iridescent gleams, explosive strokes, broken or superimposed planes and dark, ghostly depressions which confer a phantasmal effect on the figures themselves. Sofia does not paint "effects". Against the background- almost never neutral, even if it appears empty or "uninhabited" - against that space which seems magnetized as if in waiting, she prepares the conditions for an effect to be created in the gazer's sensibility. Her technique leaves room for both moments of geometrical rigour and states of absence and surrender in keeping with the dreamlike quality of the painting. It is at this point that the initial elements of the figuration become abstract, in the genuine sense of the term. Reverberating lines cross in the space of the pictures, which suddenly seems constellated by fragments of broken mirrors. There is a continual refraction of planes and dimensions amid those sombre hollows into which colours are reabsorbed as if dyed in half shadow. Colour does not reappear as a mere covering thrown into prominence by the light; it comes from the depths

Sofía Gandarias

of the object, from the inside of the painting, from its intimate nature poised between opacity and transparence. It is thus not the "reality" of the represented object that is fissured and rendered highly abstract. At least, what dominates the painting is not that referential reality of "likenesses", but, rather, the new and changing figuration established between the observer and the depicted "presences", which no longer correspond lo the conventional rules of portrayal of the individuals represented. Suddenly, cracks appear in those noble masks, sanctified by death or the weight of mundane prestige, yielding unexpected revelations of the spirit, the deep psychology of the persons portrayed. In this sudden breach we discover the true character of that maker of characters, the author of imaginary worlds. According to Bernard Show, no author is, in potential, inferior to any of his characters - neither to the most noble and heroic, nor to the most wicked and perverse. This is obvious; were it otherwise, the author could not have imagined them. He would have been overwhelmed by them before succeeding in giving them life. The same may be said of painters- perhaps with greater reason than for writers, given the freer nature of painting in comparison with the limitations of writing. If writers are scribes, painters are inscribers. The ancient sages were already astonished that speech, the living essence of oral language, could have been solidified into writingthat written signs could record and fix the spoken word, thus contradicting and negating the natural flow and rhythm of life.Written language organizes the spoken chain into links and relationships. Painting, like music, returns signs to the freeflowing

voltura que la luz pone de manifiesto; viene del fondo del objeto, de la interioridad del cuadro, de su constitución íntima que oscila entre la opacidad y la transparencia. De este modo, no es la «realidad» de lo representado la que se resquebraja y adquiere un alto grado de abstracción. Al menos, no es esta realidad referencial de los «parecidos» la que domina en el cuadro, sino la nueva y cambiante figuración que se establece entre el observador y las «presencias» retratadas. Ellas no corresponden más a la iconografía convencional de esos individuos representativos. De pronto, ciertas grietas aparecen en las nobles máscaras sacralizadas por la muerte o por el peso del prestigio todavía mundano y producen revelaciones imprevistas sobre el espíritu y la psicología profunda de los retratados. Por esa brecha súbita surge el personaje real de ese hacedor de personajes que es el autor de mundos imaginarios. Bernard Shaw señalaba que ningún autor es potencialmente inferior a ninguno de sus personajes tanto los del más alto grado de heroísmo y de nobleza como los más perversos y malvados. Claro. De otro modo no hubiese podido concebirlos. Hubiera sido anonadado por ellos antes aún de haber logrado darles vida. Lo mismo se puede decir de los pintores.Y tal vez con mayor razón que de los escritores por la naturaleza más libre de la pintura en comparación con las limitaciones de la escritura. Los escritores escriben. Los pintores inscriben. Los sabios de la antigüedad ya se asombraban de que el habla, la naturaleza viviente del lenguaje oral, hubiesen podido precipitarse en la escritura y que los signos de ésta las hubieran podido recoger y fijar en un

33

34

HOMENAJE A EL GRECO

proceso inverso y negador de la naturaleza y la palpitación vital. La lengua escrita organiza con nexos y eslabones la cadena de lo hablado. La pintura –como la música– devuelve los signos al magma ibérrimo de la visión, a su esfera de resonancias y de armónicos. Acaso la mirada zahorí y como sonámbula con la que Sofía Gandarias contempla a sus modelos vivientes y desaparecidos para plasmarlos en sus cuadros desde «adentro» y para oír hablar a cada uno de ellos en sus figuras aparente o definitivamente mudas, no sea uno de los méritos menores de esta visionaria exploradora de sombras. De este modo, los retratos de Sofía Gandarias no se limitan a ser homenajes celebratorios a los personajes elegidos. Son un acto, sí, de reconocimiento de esos personajes representativos en lo que tienen de humano. Pero también, y principalmente, un acto de conocimiento de sí misma a través de esas figuras pintadas a pequeños golpes de soledades y encuentros. Como es la vida. En este sentido, sus retratos son presencias en el sentido más rico y sugerente del término. Presencias como imantadas por el aura, por el halo de misterio de la re-presentación: esa ausencia del retratado dos veces presente en la doble imagen superpuesta del modelo y de la artista que se ve y se representa a sí misma en la apariencia del modelo. No estamos aquí, desde luego, ante los ventanucos que abría el Durero para ser contemplado por él mismo desde un autorretrato. O ante el autorretrato del propio Velázquez que pone su presencia detrás de las Meninas: el Velázquez que se contempla y nos contempla instalado en la otra escena dentro de la escena. Hemos dicho ya que el arte

lava of vision, to its sphere of resonances and harmonics. Sofia Gandarias contemplales her models, living or dead, with a gaze like that of a seer or a somnambulist, in order to give them form "from within" in her paintings, and to release the voice, apparently and perhaps forever silent, of each one. This may be not the least merit of this visionary explorer of shadows. Her portraits are thus not merely tributes celebrating their chosen subjects. They are an act of recognition of those persons in their human representativeness- but also, and above all, an act of self-understanding through these figures painted stroke by stroke out of solitude and relationships, just as happens in life itself. In this sense, her portraits are presences in the richest and most resonant sense of the term. They are presences which seem magnetized by an aura, by the mysterious halo of re-presentation: the subject is absent, yet doubly present, in the superimposed images of the model and of the artist who sees and represents herself in the appearance of the model. This is a different case, of course, from the story of the openings made by Dürer so that he could be looked at by his own self-portrait, or from the self portrait of Velázquez behind the Meninas, contemplating himself and us from the other scene within the painting. As we have already said, the art of Sofia Gandarias is an art rooted in selfdiscipline and in profound dramatic impulses; it is introspective, yet also carries out an at times heart rending ontological and existential probing into the models whom she chooses and identifies with without losing herself in them. One may here aptly cite Ortega y Gasser's comments on the charac-

Sofía Gandarias

teristics of the "authentically Spanish portrait" and the essential dramatic power that it embodies quite independently of the person portrayed. To quote Ortega, that most lucid of observers: "The drama lies in transposing something of the subject's absence into his presence; this is the almost mystical drama of 'apparition'. The figures are perpetually present on the canvas, creating their own apparition, and so they seem like spirits". It is only with the "non-sentient likeness" that the Human realm begins. At that moment- to quote Waiter Benjamin- "the likeness appears with the rapidity oflightning"; in a sudden flash, we see that ray of light which has always been there, hidden in the darkness. In this "apparition" which is not "appearance", we may venture to locate the key to our painter's art. Her quest is to give a new and different life to those presences; to give movement to the arrested immediacy of those figures; to stir and shake their apparent fixity of representation through the rhythm of all their possible transformations. She achieves this goal in the continuing process of dialogue, first between her own world and that of her subjects, then between the paintings and the pultic. It is at this moment that the absences are perfectly filled with the presences which "appear with the rapidity of lightning", and which all those who contemplate the paintings lake away inside them; for they are the same, yet different.

de Sofía Gandarias es un arte de ascesis, de pulsiones dramáticas profundas, de introspección pero también de indagación ontológica y existencial por momentos desgarrada, en los modelos que elige y con los cuales se identifica sin confundirse con ellos. Y aquí viene bien la reflexión de Ortega sobre las características del «buen retrato español», del poder dramático que contiene, cualquiera sea la persona representada, y que es el más elemental. «El drama consiste –observa el espectador lucidísimo que es Ortega– en pasar algo de su ausencia (de la persona representada) a su presencia, el dramatismo casi místico del ˝aparecerse˝. Perennemente están en el lienzo las figuras, ejecutando su propia aparición y por eso son como aparecidos». El orden humano sólo se inicia con el «parecido no sensible». Y entonces -lo dice también Walter Benjamin «con la rapidez del relámpago el parecido aparece». El rayo de luz que siempre estuvo ahí, oscuro, de pronto fulgura. Este «aparecerse» y no el «parecerse» es quizás la clave del arte de esta pintora. Lo que busca es dar una nueva vida, una vida otra a esas presencias; es movilizar la instantaneidad detenida de esas figuras; es mover y conmover la aparente fijeza de las representaciones en los ritmos de todas sus transformaciones posibles.Y esto lo logra en los movimientos del diálogo que comenzó entre su mundo y el de los retratados y que prosigue entre los cuadros y los espectadores. Es ahora cuando las ausencias se colman plenamente con las presencias que «con la rapidez del relámpago aparecen» y que cada uno de los espectadores se lleva. Las mismas pero diferentes

35

Sofía Gandarias

37

José Saramago The face and the mirror or painting as memory

El rostro y el espejo. o la pintura como memoria

The painter stands before the mirror, neither in profile nor three-quarter view, in the position she normally selects when using herself as a model. The canvas is the mirror, and it is on the mirror the colors will be laid.With the precision of a cartographer, the painter sketches in the outlines of her image. As if dealing with a perimeter, a limit, she becomes the prisoner of herself.The hand that paints moves continually back and forth between the two faces, the real one and the reflection, but it has no place in the painting. The hand that does the painting cannot paint itself in the act of painting. It makes no difference whether the painter, in the mirror, begins with the mouth or the nose, the cheeks or forehead, bur she must absolutely avoid starting with the eyes, because they would cease to see. The mirror in this case must be moved. The painter will depict with precision that which she sees on that which she is seeing, bur with a precision that forces her to ask a thousand times during the work if that which she is seeing is already painted, or whether it is in fact her face reflected in the mirror. But she risks having to paint herself forever, unless, no longer being able to stand the bewilderment, the anguish, she decides to accept the challenge of endlessly painting the eyes on the eyes, thus, who knows, losing the awareness of her own face, transformed on a surface without color or form, requiring it to be painted yet again. From memory. Sofia Gandarias's works are these painted mirrors, from which her reconstructed, or perhaps even hidden, image has

El pintor está delante del espejo, no de soslayo o en tres cuartos, según se quiera designar la posición en que suele colocarse cuando decide elegirse a sí mismo como modelo. La tela es el espejo, sobre el espejo es donde van a ser extendidas las pinturas. El pintor diseña con rigor de cartógrafo el contorno de su imagen. Como si él fuera una frontera, un límite, se convierte en su propio prisionero. La mano que pinta se moverá continuamente entre dos rostros, el real y el reflejado, pero no tendrá lugar en la pintura. La mano que pinta no puede pintarse a sí misma en el acto de pintar. Es indiferente que el pintor comience a pintarse en el espejo por la boca o por la nariz, por la frente o por la barbilla, pero debe tener el cuidado supremo de no comenzar por los ojos porque entonces dejaría de ver. El espejo, en ese caso, mudaría de lugar. El pintor pintará con precisión lo que ve sobre aquello que ve, con tanta precisión que tendrá que preguntarse mil veces, durante el trabajo, si lo que está viendo es ya la pintura, o será nada más, y todavía, su imagen en el espejo. Correrá por tanto el riesgo de tener que seguir pintándose infinitamente, salvo si, por no poder soportar más la perplejidad, la angustia, decide correr el riesgo mayor de pintar por fin los ojos sobre los ojos, perdiendo así, quién sabe, el conocimiento de su propio rostro, transformado en un plano sin color ni forma que será necesario pintar otra vez. De memoria. Las telas de Sofía Candarías son estos espejos pintados, de donde se ha retirado, recompuesta, su imagen, o donde oculta aún se mantiene, tal vez

José Saramago was a Portuguese writer, widely recognized as one of the most important literary figures of our time. He received the Nobel Prize in Literature, and the Camões Prize and America Award, among many others.

José Saramago fue un escritor portugués, ampliamente reconocido como una de las grandes figuras literarias de nuestro tiempo. Recibió el Premio Nobel de Literatura, así como el Premio Camões y el America Award, entre otros muchos.

#7

El Caballero Tzvetan Todorov Óleo sobre lienzo / 100 x 81 cm. / 2013

38

HOMENAJE A EL GRECO

bajo una capa de luz dorada o de sombra nocturna, para entregar al uso de la memoria el espacio y la profundidad que le conviene. No importa que sean retratos o naturalezas muertas: estas pinturas son siempre lugares de memoria. De una manera visual, obviamente, como se espera de cualquier pintor, aunque también de una memoria cultural compleja y riquísima, lo que ya es mucho menos común en un tiempo como este nuestro, en que las miradas, ya sea la de lo cotidiano, ya sea la del arte, parecen satisfacerse con pasar simplemente por la superficie de las cosas, sin darse cuenta de la contradicción en que incurren, al confrontarse con la mirada científica moderna que ha transferido su campo principal de trabajo hacia lo no visible, tanto si es lo astronómico o lo subatómico.

been withdrawn. Possibly she hides from herself under a patina of golden light or nocturnal shadow, restoring to the uses of memory the space and depth that belong to them. It matters little that these portraits or still-lifes are inert: these paintings are above all located in memory. It is a visible, perceptible memory as one might expect from any painter, but it springs from a complex and very rich cultural memory, already extremely unusual in an epoch like ours. An epoch in which the gaze, whether in daily life or in art, seems content to barely graze the surface of things, without registering the contradictions it contains, contrary to a modern scientific vision that has transferred its main concern to the non visible, whether in the far reaches of space or on a subatomic level.

Para Sofía Gandarías, un retrato nunca es sólo un retrato. Algunas veces parecerá que se propone contarnos una historia, relatarnos una vida, cuando, por ejemplo, rodea su retrato de elementos figurativos cuya función, o intención, se ha de suponer alegórica, como un jeroglífico cuya interpretación más o menos rápida dependerá del grado de conocimiento de las respectivas llaves que tenga el observador. Es transparente, por ejemplo, el significado de la pirámide maya en el retrato de Octavio Paz, o de una Melina Mercuri atada al Partenón, lo es mucho menos el de Graham Greene mirando por una ventana con los cristales partidos, o de un Juan Rulfo amarrado a las tumbas de Comala. Contemplada desde este punto de vista, la pintura de Sofía Candadas, con independencia de su altísimo mérito artístico y de su evidente calidad técnica, podría ser entendida como un ejercicio literario para iniciados, capaces de organizar los símbolos mostrados, y por tanto completar, en el propio nivel, la enigmática propuesta del cuadro. Se trataría de una consideración flagrantemente

For Sofia Gandarias a portrait is never merely a portrait. Sometimes one has the sensation that she intends to tell us a story, to recount a life, as when for example around the principle subject are placed narrative elements that function allegorically, like hieroglyphics, whose quick reading depends more or less on the level of acuiry the observer brings to it. For example, the meaning of the Mayan pyramid in the portrait of Octavio Paz, or of Melina Mercouri next to the Parthenon, is clear. Less clear is the portrait of Graham Greene, who gazes out a broken window, or that of]uan Rolfo next to the tomb of Comala. Viewed this way, the art of Sofia Gandarias, apart from its superior artistic value and its obvious technical qualiry, could be taken as a literary essay for the initiated, organizing the symbography and piecing together on their own level the enigmas proposed by the paintings. We're speaking of a Aagrantly reductive consideration, in any case absolved from the immediacy of the reading, as if the painting of a portrait by Sofia Gandarias weren't something that is in a way su-

Sofía Gandarias

perior: the singulariry of a memory of relationships. A double relation ship, I might add. That of the subject to his or her circumstances, expressed through the placement of the secondary elements of the painting, all of which, though while we can appreciate the realistic rendering,the pertinence, the plasticiry, and so on, in my opinion is no less important than the cultural relationship that Sofia Gandarias, the painter, but especially the person who carries this name, maintains with the existential and intellectual circumstances of her subjects.We're dealing overtly here with painting, but also with a very intense expression of a particular cultural memory. More than merely painting portraits of so-called public figures, what Sofia Gandarias does is to call up one after another the inhabitants of her memory and her culture, what she herself calls "presences," and transfer them onto a canvas where they will have the privilege of being much more than portraits, insofar as they are the marks, the: imprints, the flaws, the light and the shadow of her inner world. There is a melancholy in this art. The melancholy of knowing we arc small, fleeting, transitory shooting stars which burn out as soon as they begin to shine. The background of Sofia Gandarias's paintings, almost always dark, is night. The faces and symbols which, like sa tellites, sweep by us, are nothing more than our pale, human remains. The world is what we are, and these paintings are one of its senses.

reductora, en todo caso ab-suelta por la propia inmediatez de la lectura, si la pintura del retrato de Sofía Candarías no fuese lo que, de modo superior, es: la singularidad de una memoria de relación. De doble relación, añadiré. La del retratado y la de su circunstancia, expuesta en la distribución de los elementos pictóricos secundarios del cuadro, y en que naturalmente se apreciarán cuestiones como la semejanza, la pertenencia, la concatenación plástica; y otra, a mi ver no menos importante, que es la relación cultural que Sofía Candarías, la pintora, pero sobre todo la persona de ese nombre, mantiene con la circunstancia vivencial e intelectual de sus retratados. Aquí se trata claramente de pintura, pero se trata también de la expresión intensísima de una memoria cultural particular. Más de lo que simplemente pintar retratos de figuras de las llamadas públicas, lo que Sofía Gandarias hace es convocar, uno por uno, a los habitantes de su memoria y de su cultura, aquellos a quienes ella misma llama «la presencias», transportándolas a una tela donde tendrán el privilegio de ser mucho más que retratos, porque serán las señales, las marcas, las cicatrices, las luces y las sombras de su mundo interior. Hay melancolía en esta pintura. Hay melancolía en sabernos fugaces, transitorios, pequeños cuerpos cayentes que se apagan cuando apenas comenzaban a brillar. El fondo casi siempre oscuro de Sofía Candarías es una noche, los rostros y los símbolos que como satélites los rodean son apenas nuestros pálidos y humanos fulgores. El mundo es lo que somos, y esta pintura uno de sus sentidos.

Lanzarote, 1995 Lanzarote 1995

39

Sofía Gandarias

41

Esther Bendahan A pale hand on the chest of man and woman

Una mano pálida en el pecho de hombre y de mujer

I think I am one being after another, because I am what the rumor of springs has left in my ear... To the awaited one, Rainer Maria Rilke

Pienso que soy un ser tras otro, pues soy lo que el rumor de los manantiales ha dejado en mi oído.... La esperada, Rainer Maria Rilke

The gentlemen and gentlewoman knights of the hand on the chest of Sofia Gandarias express not only their admiration for the painting of El Greco: "a painting of gray tones, painting in its purest state" according to the author, who starts her particular conversation in 2013, and approaches its mysterious secret without revealing it.

Los caballeros y caballeras de la mano en el pecho de Sofia Gandarias expresan no sólo su admiración por el cuadro del Greco: “un cuadro de tonos grises, pintura en estado puro” según la autora quien inicia su particular conversación en el año 2013, sino que se aproxima sin desvelarlo a su misterioso secreto.

The choice is not casual. "Paradoxically, in the painting of El Greco, it is his very absence that proclaims the knight's resignation to the vanities, his moral worth (...) He does not relax nor show off (...). Instead this man is impassive and distant. He does not dialogue. His gestures are rituals, (...) El Greco while painting this portrait has not only followed the formulas of chivalric decorum, but has also revealed the essence of his ritual through his handling of painting"(David Davies). Davies finally points out that: "El Greco has given eloquent form to the quintessence of the Spanish hidalgo."

La elección no es casual. “En el Greco Paradójicamente, es su misma ausencia lo que proclama la renuncia del caballero a las vanidades, su valía moral (...) Ni se relaja ni se pavonea (...) En lugar de eso, este hombre está impasible y distante. No dialoga. Sus gestos son rituales, (...) Al pintar este retrato, El Greco no solo ha seguido las fórmulas del decoro caballeresco, sino que también ha revelado la esencia de su ritual a través de su manejo de la pintura.” (David Davies) Finalmente Davies señala que: “El Greco ha dado forma elocuente a la quintaesencia del hidalgo español.”

Sofia, inspired by El Greco, close to her elegant intensity and ethical sobriety and committed to symbol and detail, analyzes The Knight with his Hand on his Chest through her own characters of undeniable topicality: Yehudi Menuhin, Maria

Sofia, inspirándose por el Greco, próxima a su elegante intensidad y ética sobriedad, empeñada en el símbolo y en el detalle, analiza el Caballero de la mano en el pecho a través de sus propios personajes de indiscutible actualidad: Yehudi Menuhin,

Esther Bendahan is a Spanish-Moroccan writer of Sephardic ascent. She received the Torrente Ballester and Fnac prizes, among others. She is Chief of Cultural Programming at the Sefarad-Israel Center (Madrid).

Esther Bendahan es una escritora hispano-marroquí de origen sefardita. Ha recibido los premios Torrente Ballester y Fnac, entre otros. Es Jefa de Programación Cultural en el Centro Sefarad-Israel en Madrid.

#8

El Caballero Albert Einstein Óleo sobre lienzo / 100 x 81 cm. / 2013

42

HOMENAJE A EL GRECO

Maria Callas, Luchino Visconti, Steven Spielberg, Frida Kahlo, Salma Hajek, Robert de Niro, Penélope Cruz, Javier Bardem, Rilke, Albert Einstein, entre otros. Hay que señalar que el primero, el principio es Rilke, a partir del poema "La Esperada" de su trilogía española. El último es Al Pacino como Shylock del Mercader de Venecia. Pero es una colección incompleta ya que la autora tenía el propósito de continuar.

Callas, Luchino Visconti, Steven Spielberg, Frida Kahlo, Salma Hajek, Robert de Niro, Penelope Cruz, Javier Bardem, Rilke, Albert Einstein, among others. It should be noted that the first portrait, the principle, is Rilke, from the poem "To the Awaited One" of his Spanish trilogy. The last one is Al Pacino as Shylock, the Merchant of Venice. But it is an unachieved series since the author intended to continue.

Uno delante de su obra queda en riguroso silencio. Cada personaje nos convoca a una idea diferente, una acción contemporánea traída voluntariamente a la hidalguía española. Conocidos por la mayoría son escritores, científicos, autores, músicos, actores que generan en lo contemporáneo estremecimiento, cambio, compromiso. Todos ellos se enfrentan al retrato del Greco, anónimo, eterno. Lo conocido, los rostros de nuestro tiempo, frente a un símbolo silencioso y misterioso que les empuja hacia el lado oculto de nuestra época. ¿Qué nos revelan los nombres que forman parte de nuestro tiempo además de lo que sabemos? ¿Que sabrán de nosotros quienes vengan después?

You remain, in front of her work, in strict silence. Each character calls us to a different idea, a contemporary action voluntarily brought to the Spanish “hidalguía” ( gentlemanliness) . Writers, scientists, authors, musicians and actors, known by most, generate shuddering, change, commitment. All of them confront the portrait of El Greco in an anonymous and eternal way. The known, the faces of our time facing a silent and mysterious symbol that pushes them towards the hidden side of our time. What are revealing the names that are part of our time moreover what we already know? What will know about us those that will come afterwards?

Sofia lanza así hacia el futuro una pregunta, un interrogante, aúna tiempos y da sentido a la cuestión eterna: ¿somos uno o deberíamos ser uno? Un caballero o caballera con la mano en el pecho, con el arma a un lado y semi oculta en el Greco, defendiendo el atrevimiento de ofrecer la mano pálida, mano de músico, de artista (quizá la otra mano es la del granjero, la del minero aplacando el arma), ofreciendo eternamente el lado donde se sitúa metafóricamente la acción de un sentimiento. Mano como símbolo del poderoso palpando el origen de todo poder: el sentimiento, el pecho, el corazón: la emoción. El corazón protegido por una mano que a la vez lo ofrece. Así nos

Sofia is launching to the future a question, joins times and gives meaning to the eternal doubt: are we one or should we be one? A gentlemen or gentlewoman knight with his or her hand on his or her chest, with the weapon on one side and half hidden, defending the audacity of offering the pale hand, the hand of a musician, the hand of an artist (perhaps the other hand is the hand of the farmer or the miner placating the weapon), eternally offering the side where the action of a feeling is metaphorically situated. Hand as a symbol of the mighty feeling the origin of all power, the feeling, the chest and the heart, the emotion. A heart protected by a hand that simultaneously offers it. Sofia

Sofía Gandarias

introduces to us powerful characters, in contrast to the hidalgo of El Greco, with a serious gesture, the seriousness of the one who watches while the other one speaks, the seriousness of the one who becomes aware, few faces have a smile like the case of Yehudi Menuhin, characters like Al Pacino, her last painting, who in turn are another character, where we can contemplate the culmination of the artistic effect, the power of evocation, of social criticism and analysis. And the red appears with a breaking and claiming effect. This legacy, in addition to its artistic value, hides the mystery of the character, art and creation. She questions the face and frames it in a sacred space, she dares to judge and play. A brave bet of an artist who left us young. We discovered Sofia through portraits of her choice and her passionate game of identities, where she hid her stake, desire, search for greatness and elegance, appealing to the ethics to be invoked over and over again so that we do not forget. Sofia showed the portraits in her studio to visitors who discovered the intimate world of a great artist also in its purest form, as she pointed out about the colors of El Greco, and, above all, committed to the memory that must be invoked to protect the sense, culture, what we understand when we say: the greatness of the human being. A dark background: eternity, a pale hand, the future.

presenta a personajes poderosos, en contraste con el del Greco, con un gesto serio, la seriedad del que mira cuando el otro habla, la del que se da cuenta, rostros en los que solo en algunos como en Yehudi Menuhin se contiene una sonrisa, personajes que a su vez son otro como Al Pacino, su último cuadro, donde contemplamos la culminación del efecto artístico, el poder de la evocación, de la crítica social, el análisis. Y aparece el rojo que rompe y reclama. Este legado además de su valor artístico, esconde el misterio del personaje, del arte, de la creación. Cuestiona el rostro, lo enmarca en un espacio sagrado, se atreve a juzgar y jugar. Valiente apuesta la de una artista que nos dejó joven, y a la que descubrimos a través de los retratos, de su elección, de su apasionado juego de identidades, donde se oculta su apuesta, su deseo, su búsqueda de la grandeza y elegancia apelando a la ética que hay que invocar una y otra vez para que no olvidemos. Sofia nos enseñaba los retratos en su estudio a los visitantes que participábamos así del descubrimiento del mundo íntimo de una gran artista también en estado puro como ella señalaba del color del Greco, y, sobre todo, comprometida con la memoria que hay que invocar para proteger el sentido, la cultura, lo que entendemos cuando decimos: la grandeza de lo humano. Un fondo oscuro: la eternidad, una mano pálida: el futuro.

43

Sofía Gandarias

45

Carlos Fuentes To Sofía Gandarias: art against violence

A Sofía Gandarias: arte contra violencia

Cntemporary "s treet art" and the art of antiquity share two things: they're unsigned and they don't make any pretense of being original. Fruit of the humanistic superiority of the Renaissance, to pur one's name on a painting or sculpture was an innovation of the collective and anonymous spirit of the Middle Ages. Name and surname, says Montaigne: the cult of me-ism is a feature of western modernity, and despite Pacalconsider it "detestable."

El arte popular y el arte antiguo se asemejan en dos cosas: son anónimos y no pretenden ser originales. Resultado de la soberbia humanista del Renacimiento, tener un nombre y ponerlo al pie de un cuadro o de un monumento es una novedad para la tradición colectiva y anónima de la Edad Media. Nombre y sobrenombre, dice Montaigne: las aventuras del Yo son las de la modernidad occidental, por más que Pascal lo juzgue «detestable».

Regardless, nobody signed the cathedrals of Chartres and Aachen, nor the unassuming "retablos" of the Mexican baroque churches. Entire schools and workshops of the late Middle Ages declare themselves to be Masters of the Legend of Saint Ursula, Masters of the Magdelene. Names, surnames, and images quickly vanish in this spirit of modesty. Avoiding the obstacles of this solipsism, the great European portraitists give to art a social function, occasionally even democratic: we gaze at faces that otherwise leave neither proof nor witness to their passage on earth. A times they acquire a dimension so intimate it projects a kind of melancholy, as with the self-portraits of Rembrandt. Spanish artist Sofia Gandarias, working in the great tradition ofVelazquez for whom the portrait was a mark of identity, proof of existence and ironic balancing act between infamous notoriety and visible invisibility, between monarchy and anarchy, Philip IV and the masked functionaries of God, between Carlo IV and the lovers of the Festival of

Carlos Fuentes was a Mexican novelist and essayist. Fuentes received the Rómulo Gallegos, Cervantes, Prince of Asturias, and Four Freedoms Award, among many other.

#9

El Caballero Javier Bardem Óleo sobre lienzo / 100 x 81 cm. / 2014

En cambio, nadie firma ni las catedrales de Chartres y Aquisgrán, ni los modestos retablos de las iglesias barroas de México. Escuelas –¿talleres?– enteros del otoño de la Edad Media se presentan como «Maestros de la Leyenda de Santa Úrsula», «Maestros de la Magdalena». Nombre y sobrenombre, hubris, facies, despiden pronto esa modestia. Evitando los escollos del solipsismo, los grandes retratistas de Europa le dan a su arte una función social, a veces hasta democrática: aquí está el rostro que, de otra manera, no tendría evidencia, no dejaría rastro de su paso por el mundo. Le dan, a veces, una dimensión tan íntima que se proyecta con melancolía: los autorretratos de Rembrandt. Sofía Gandarias, en la gran tradición velazqueña, española, del retrato que es seña de identidad, prueba de existencia y ejercicio irónico entre la fama infame y la invisibilidad visible, entre el monarca y los anarcas, entre Felipe IV y los obreros disfrazados de dioses, entre Carlos IV y los enamorados de las fiestas de San Isidro, nos ofrece retratos de nuestro tiempo en los que la figura y su

Carlos Fuentes fue un novelista y ensayista mexicano. Fuentes recibió los premios Rómulo Gallegos, Premio Cervantes, Príncipe de Asturias y el Four Freedoms Award, entre muchos otros.

46

HOMENAJE A EL GRECO